Abstract

In this review, we describe recent advances in the field of RNA regulatory biology and relate these advances to aging science. We introduce a new term, RNA surveillance, an RNA regulatory process that is conserved in metazoans, and describe how RNA surveillance represents molecular cross-talk between two emerging RNA regulatory systems – RNA interference and RNA editing. We discuss how RNA surveillance mechanisms influence mRNA and microRNA expression and activity during lifespan. Additionally, we summarize recent data from our own laboratory linking the RNA editor, ADAR, with exceptional longevity in humans and lifespan in C. elegans. We present data showing that transcriptional knockdown of RNA interference restores lifespan losses in the context of RNA editing defects, further suggesting that interaction between these two systems influences lifespan. Finally, we discuss the implications of RNA surveillance for sarcopenia and muscle maintenance, as frailty is a universal feature of aging. We end with a discussion of RNA surveillance as a robust regulatory system that can change in response to environmental stressors and represents a novel axis in aging science.

1. Introduction

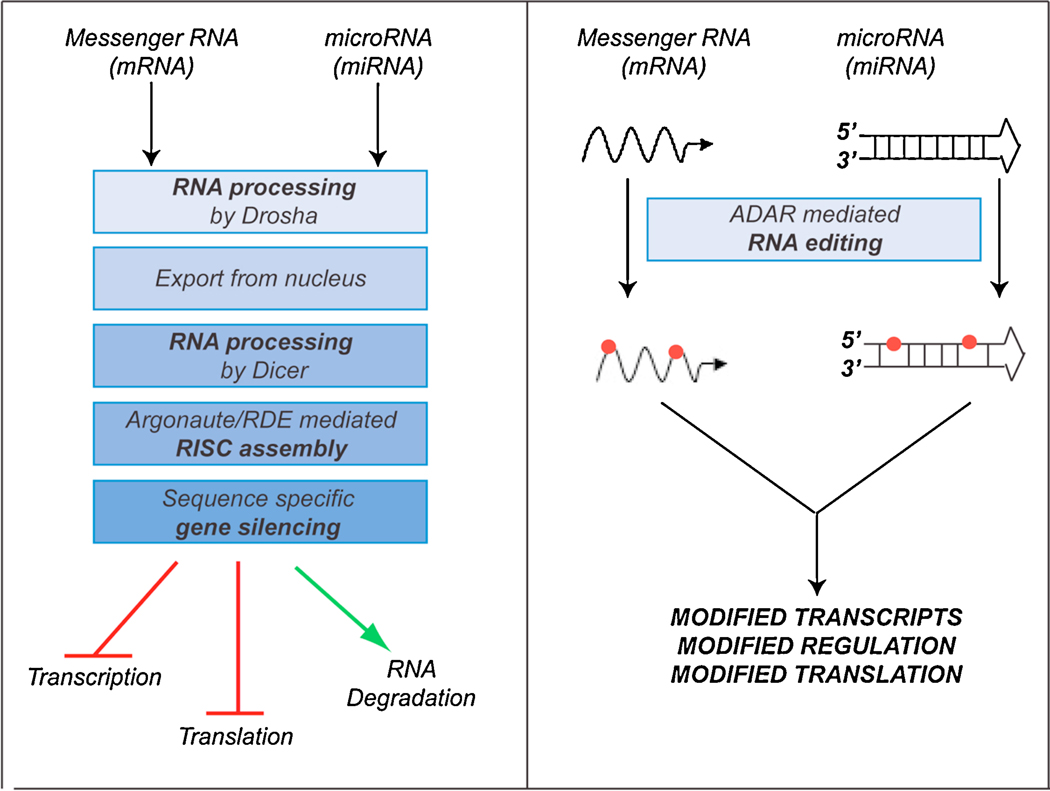

An emerging theme in the biology of aging over the last decade is the prominent role gene regulatory pathways that are conserved among metazoans ((Partridge and Gems, 2002; Tissenbaum and Guarente, 2002). For example, caloric restriction, insulin-signaling pathways, and stress response pathways use common homologous genes to modulate longevity in nematodes, flies, and mammals. Age-associated declines in muscle mass and muscle strength (Sarcopenia) (Fisher, 2004; Karakelides and Nair, 2005) are also a common feature in metazoan lifespan (Herndon et al., 2002). While post-translational protein-based mechanisms are broadly utilized in gene regulation and recognized to play a role in aging, notably Sirtuin deacetylases (Guarente 2007), transcription factors (e.g., FOXO/DAF16, Lee 2003 Science) and apolipoproteins (e.g., apoE, Louhija 1994; Seripa D, 2006), there is a growing interest in the role of RNA regulatory mechanisms that potentially influence aging. The role of the “RNA World” as encompassing more than a messenger of the DNA genetic code was first championed by Walter Gilbert in 1986 and has since been well established, with multiple RNA based regulatory and enzymatic activities now recognized. In this review we discuss, based on both published and our own preliminary data, how environmental perturbations (e.g., stress ligands, microenvironmental cues) can induce a regulatory system of RNA surveillance, which we define as the interaction between a class of RNA editing (RNAe) and RNA interference (RNAi) genes (Figure 1), and how this RNA regulatory system may represent a novel axis with influence on aging.

Figure 1. RNA surveillance genes.

Composition of the RNA interference and RNA editing machinery with orthologues in vertebrates, nematodes and plants.

MicroRNAs are a component of the RNAi pathway and have been identified in organisms across the evolutionary spectrum, including plants, mammals, invertebrates, and viruses (Bushati and Cohen, 2007). Many previous studies evaluating microRNA expression have observed age-associated expression patterns in distinct organisms and tissue (Lund et al., 2002; Murphy et al., 2003; Weindruch et al., 2002), suggesting that changes in gene expression are driven by evolutionarily conserved mechanisms of aging (see Figure 1). Although age-associated changes are apparent, there is very little information on the potential role for microRNAs in age-related declines in function, despite the growing literature on the role for microRNA in specific gene regulation programs. In addition to RNA interference (RNAi) mediated gene-silencing by microRNA, a second RNA regulatory system is RNA editing. RNA editing enzymatic activity has the capacity to generate functional diversity in proteins (e.g., altered translated product) and in microRNA (e.g., via edited miR sequence). This activity has been described to influence multiple biological processes that include synaptic transmission (Schmauss and Howe, 2002), innate immune response (Yang et al., 2003) and muscle function (Keegan et al., 2005). The biochemical mechanism for enzymatic modification of multiple RNA targets has been well described (reviewed in (Bass, 2002; Valente and Nishikura, 2005), including editing of miRNA (Yang et al., 2006). Interestingly, both loss-of-function and gain-of-function in levels of RNA editing activity are deleterious, suggesting that cell-type or organ specific set points in RNAe activity levels are highly regulated (Keegan et al., 2005). The predominant form of RNA editing is adenosine-to inosine (A-to-I) post-transcriptional modification and is mediated by the RNA editor Adenosine Deaminase Acting on RNA (ADAR), first identified in Xenopus (Bass and Weintraub, 1988). RNA editors are environmental sensors that function in chemo-sensing and stress response. This capacity to detect microenvironmental flux and stress provides an adaptive advantage because mutations that extend longevity typically lead to improved stress resistance. In human studies, change in RNA editing activity is associated with age-related cognitive dysfunction that include, but are not limited to, schizophrenia, dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Maas et al., 2006). The process of RNA editing appears to be conserved in evolution, with evidence for homologues with similar enzymatic function in humans (Kim et al., 1994), Drosophila (Palladino et al., 2000), Zebrafish (Slavov et al., 2000), Xenopus (Hough and Bass, 1997) and in C. elegans (Morse et al., 2002).

2. RNA surveillance processing mechanisms: RNA interference and RNA editing

Recent advances in the understanding of RNA processing, particularly RNA interference (RNAi) and RNA editing (RNAe), have substantial implications for the molecular biology of aging. Much of our knowledge concerning RNAi, also known as RNA silencing or post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTSG), is based on early studies in plants and nematodes (Fire et al., 1998; Wightman et al., 1993). RNAi refers to a process wherein double-stranded RNA triggers a multistep process of RNA silencing that is sequence-dependent. The discovery of RNA silencing led to a Nobel prize in 2006 awarded to Andy Fire and Craig Mello. Our understanding of RNAi has now expanded to include small interfering RNA (siRNA) and microRNA (miRNA). The former, siRNA, is processed from short double-stranded RNA transcripts via RNA cleavage (i.e., through RNAse III, Drosha and Dicer) in a process that tends to be induced by exogenous stimuli (e.g., RNA virus infection, stress ligands). RNAi therefore acts as a stress sensor in host response to exogenous RNA viral infection. The latter, microRNAs (miRNA) are small (~22 nucleotides) endogenously transcribed RNAs that are now recognized to be critical for post-translational gene expression and play important roles in numerous processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, cell fate determination, and immune regulation (Sonkoly et al., 2008).

Primary miRNAs are processed into short stem-loop pre-miRNA hairpin structures. These are then further cleaved to yield mature miRNA. MiRNAs regulate protein expression by binding to the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of a target mRNA, resulting in either mRNA destabilization, degradation, or inhibition of protein translation (Valencia-Sanchez et al., 2006). Target specificity is primarily determined by the "seed sequence" of the miRNA, nucleotides 2–8 in the 5' end of the miRNA (Lewis et al., 2005; Valencia-Sanchez et al., 2006). Processing of dsRNA (both siRNA and miRNA) is guided by multiple protein classes (see Figure 1) that include: dsRNA binding. Proteins that bind dsRNA and recruit Dicer activity to facilitate the transfer of cleaved RNAs to the RISC complex. Rnase III. Dicer (cytoplasmic) and Drosha (nuclear) endoribonucleases cleave dsRNA and catalyze the first steps in the RNA interference pathway to initiate the formation of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), thereby allowing argonaute proteins to degrade RNA targets. Exportin (Xpo). Exportins facilitate nuclear transport of RNAs into the cytoplasm facilitating access to Dicer as part of the RNA silencing pathway. Argonaute (Ago). Small RNAs such as siRNAs, miRNAs or Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are bound by Argonaute proteins (e.g., Ago in humans, RDE in nematodes). On binding to a target mRNA, the Ago-siRNA or Ago-miRNA complex induces RNA degradation or translational inhibition. RNA editing. RNA editors modify RNA transcripts through A-to-I or C-to-U deamination. This can lead to altered protein sequence in RNAs that code for proteins, but RNA editing can also result in altered regulatory transcripts (e.g., microRNA) which can influence their target specificity. Notably, both siRNA and miRNA are further processed in an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), consisting of Argonaute and other proteins that mediate their mRNA targeted gene silencing, see Figure 1. In addition to the RNAi system, a second RNA processing regulatory system is RNA editing. RNA editing is mediated by conserved RNA editing enzymes (e.g., ADAR, APOBEC) whereby bases within RNA transcripts, both mRNA and miRNA, are deaminated (adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) or cytosine-to-uracil (C-to-U), respectively. Edited sequences, if translated, can result in protein diversification, or, in the case of miRNA, alter transcriptional silencing targets or susceptibility. Pre-miRNAs undergo A→I RNA editing (Luciano et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2006) and therefore may regulate the processing and expression of mature miRNAs (Luciano et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2006). Edited miRNA has profound implications for gene regulation.

Adding to the complexity of RNAi and RNAe interactions, evidence suggests that these two pathways compete for common dsRNA substrates (Bass, 2006). Furthermore, there is at least one mammalian ADAR that can sequester siRNAs from the RNAi pathway (Yang et al., 2006). Indeed, studies of ADAR-null strains of C. elegans indicate that RNA editing may counteract RNAi silencing of endogenous genes and transgenes (Nishikura, 2006). Therefore, complementary and interactive roles of RNAi and RNAe represent a powerful RNA regulatory system whose influence on lifespan and longevity remains to be fully investigated. All metazoa experience cellular stress. Cellular stressors, including dsRNA (e.g. viral infection), inflammatory cytokines, and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Interestingly, stress induced apoptosis has also been associated with loss of ADAR, suggesting that ADAR may act to buffer cellular stressors (Hartner et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2004).

3. The relevance of RNA surveillance to aging, inflammation and muscle biology

3.1. RNA surveillance changes with normal aging

Published studies (e.g., (Lund et al., 2002)) and data from our laboratory (Montano et al., 2009) show that genes involved in RNA surveillance change with aging in nematodes, mice and human centenarians, suggesting that this regulatory axis is a common mechanism among evolutionarily distinct taxa. Whether this observation implies evolutionary selection to invasive RNA viruses or is an emergent phenotype of post-transcriptional gene regulation is unknown. Data in our laboratory are an example of how miRNA expression levels vary substantially with age, in this case based on a comparison of ~400 miRNA expression levels in whole brain tissue obtained from 3 month-, 1 year- and 2 year-old mice (Figure 3). Whether there is a common set of mRNA targets that are regulated by miRNA during the aging process is unknown. Identifying and validating miRNA expression dynamics and targets within and between species will be highly informative towards clarifying the possibility of common regulatory signatures in the aging process. In addition to miRNA expression change with aging, our laboratory recently published compelling new data implicating RNA surveillance genes in human centenarians, and that implicate both RNA editing and RNA interference pathways in lifespan (Montano et al., 2009). In that study, we demonstrated that mutations discovered in human association studies dramatically influence lifespan in C. elegans and that expression levels for these RNA regulators decline in normal lifespan of these nematodes. RNAe also appears to be regulated with aging. In C. elegans, since adr expression levels rise early in adulthood then precipitously decline with advanced age (data not shown).

Figure 3. Age trend in microRNA expression during normal aging in mice.

Brain tissue from young (3 months), adult (one year) and old (2 year) mice (C57BL6), left to right, was harvested and total RNA used to evaluate expression of 380 microRNAs using an Illumina chip platform. Hierarchical clustering was conducted yielding 8 clusters (see left of dendrogram), with clusters 1 and 2 displaying high expression in young, declining with age; and clusters 5 and 6 displaying low expression in young, increasing with age.

3.2. Cross-regulatory role for RNA interference and RNA editing in lifespan

Because RNA editing modifies ribonucleotides in target RNAs, this creates the opportunity for altered recognition by miRNAs and modified susceptibility to the RNA interference (RNAi) machinery. This possibility has been elegantly addressed in a study by Brenda Bass and colleagues, evaluating the role of ADAR activity influence on chemotaxis in the C. elegans nematode (Tonkin and Bass, 2003; Tonkin et al., 2002). Several other studies have demonstrated that processing of microRNA from precursors (i.e., pri-miRAs and pre-miRNAs) can produce substrates for ADAR-mediated editing (Habig et al., 2007; Kawahara et al., 2008). For example, editing of human pri-miR-142 blocks processing by the RNase Drosha (Yang et al., 2006) and leads to rapid degradation (Yang et al., 2006). A recent study identified 47 pri-miRNAs that were edited and subsequently blocked from reaching maturation, presumably through rapid degradation (Kawahara et al., 2008). ADAR mediated editing of both the mouse and human microRNA miR-151 prevents Dicer processing activity (Kawahara et al., 2007). ADAR editing also appears to change the specificity of target miRs. For example, both ADAR1 and ADAR2 edit miR-376, thereby creating a capacity to repress the PRPS1 gene (Kawahara et al., 2007). In muscle, a novel G to A transition in the 3’ UTR of the myostatin gene in sheep generated a target site for miR-1 and miR-206 - both miRs that are highly expressed in muscle (Clop et al., 2006 fix ref). This mutation resulted in translational inhibition of myostatin RNA transcripts and phenotypically resembled myostatin knockouts with characteristic muscle hypertrophy. The ramifications of these ADAR mediated editing activities on microRNA and mRNA is now an active area of research and is likely to yield significant insights into post-transcriptional modification of gene expression. Whether ADAR mediated modification of microRNA processing and target specificity influences transcriptome patterns during aging is unknown. Although there are data on the temporal expression of miRNAs in C. elegans (Lund et al., 2002), the potential for miRNAs to functionally influence aging has yet to be systematically addressed either within or between species. A notable recent study elegantly demonstrated that the developmental timing regulator miRNA lin-4 affects C. elegans lifespan (Boehm and Slack, 2005). Also, Ibanez-Ventoso and colleagues demonstrated that genome-wide expression of miRNAs change during adulthood and aging of normal C. elegans nematode worms (Ibanez-Ventoso et al., 2006). In that study they observed that roughly half of the nematode miRNAs exhibit changes in expression level during adult life. Included among those were lin-4 and let-7 miRNAs and miR-1, homologues of these genes are broadly expressed in Drosophila, Zebrafish, chick and mammalian muscle (Lee and Ambros, 2001; Mansfield et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2005) to influence muscle development. These data implicate miRNA in aging and lifespan, with ramifications for critical age-dependent processes, such as sarcopenia. Since many age-regulated miRNAs discovered in lower organisms are conserved, human homologues might be similarly regulated during aging. A noteworthy comparative study demonstrated that non-coding RNA in humans and C. elegans are targets of ADAR activity (Morse et al., 2002), suggesting that both RNAi and RNAe interact, thereby increasing the complexity of RNA regulatory mechanisms engaged during aging.

3.3. Variants in RNA editing genes are associated with exceptional longevity in multiple species

In a recent study of human centenarians by our group, the RNA-editing genes ADARB1 (21q22.3), and ADARB2 (10p15.3) emerged as candidate genes associated with exceptional longevity in a screening based on a new DNA pooling approach (Sebastiani et al., 2008). These preliminary data were then validated using individually genotyped data from four different centenarian cohorts for a larger number of SNPs and a total sample size (2105 subjects, 3044 controls. The consistent association of SNPs tagging regions of the genes ADARB1 and ADARB2 in multiple centenarian cohorts suggests a potential role for RNA editing genes in the survival to extreme old age (Montano et al., 2009).

To expand upon the statistical association of ADAR genes with longevity observed in humans, we evaluated a possible functional role for orthologues of these genes on influencing lifespan in C. elegans, a robust organism that is widely used for evaluation of lifespan and candidate gene discovery. To determine whether ADAR homologues in C. elegans (adr-1, adr-2) influence lifespan, we utilized ADAR mutant loss-of-function strains to conduct standard lifespan assays using synchronized L4 worms. There was a substantial (p << 0.05) decline in lifespan in adr mutants (see Figure 4a). Knockdown of daf-2, the worm homolog for the mammalian insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor, increased lifespan, but was also affected by loss of ADAR function (Figure 4a), possibly indicating that RNA editing is required for daf-2 mediated gains in lifespan. To further determine whether RNAe and RNAi interact in this model of lifespan, we evaluated the RNAi defective Argonaute gene, rde-1, in the context of adr mutant strains. Provocatively, we observed that rde-1 rescued the loss in lifespan due to adr (Figure 4b), in effect producing a phenocopy of normal lifespan. These data indicate genetic and possibly dynamic interactions between the RNAi and RNAe pathways to modulate lifespan (see model in Figure 4c).

Figure 4. Effects of ADAR on lifespan in C.elegans.

a) Lifespan using mutant strains for adr-1;adr-2 in the context of dsRNA mediated gene inactivation of daf-2. Note decline in lifespan due to adr-1; adr-2 compared with N2 wildtype. Also note increases in lifespan of both N2 and adr-1; adr-2 in the presence of dsRNA for daf-2. days) b) Lifespan using mutant strains for adr-1;adr-2 and adr-1; adr-2; rde-1 (grey solid) demonstrate declines in lifespan using mutant strains and full rescue of lifespan in an RNAi defective (rde-1) background. To synchronize worms for lifespan, eggs were isolated (N2, adr-1, adr-2, adr-1;adr-2, rde-1, rde-4, adr-1;adr-2;rde-1) and synchronized by hatching overnight in the absence of food at 20C. Synchronized L1 larvae were counted and plated (10 worms/plate, n=60) on Escherichia coli bacterial lawns (OP50) on NGM media and allowed to develop to L4-stage larvae at 20C. 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FudR) solution was added to a final concentration of 0.1mg/ml to prevent reproduction. Worms were kept at 20C and lifespan monitored by counting on alternate days. The daf-2 dsRNA -expressing bacteria were grown overnight in LB with 50 ug/ml ampicillin and then seeded onto RNAi NGM plates containing 5 mM isopropylthiogalactoside (IPTG). The RNAi bacteria were induced overnight at room temperature for dsRNA expression. About 30 synchronized L4-stage animals were added to each well and allowed to develop to adults, followed by the addition of FudR. Worms were kept at 20C, and their lifespan was monitored. c) Model interpretation of the lifespan data; wherein RNAe protects from RNAi mediated target RNA degradation.

4. RNA surveillance in aging: skeletal muscle

4.1. Sarcopenia and aging in humans

Skeletal muscle accounts for 40–50% of total body mass, and is critical for both mobility and bioenergetic metabolism, for example see (Cerletti et al., 2008). Muscle homeostasis represents a dynamic balance between anabolism and catabolism of muscle, mediated by the actions of growth factors and cytokines, as well as their respective regulators (Yarasheski, 2003), with a potential role for vasculature in providing growth maintenance cues (e.g., insulin) (Fujita et al., 2007). The loss of muscle mass and strength is a universal feature of aging. In many cases, this impairs functional capacity leading to disability. The term sarcopenia is used to describe the wasting effects of age on skeletal muscle, characterized by a loss of muscle mass and function, metabolic dysregulation (Ryall et al., 2008), and an overall increase in vulnerability to stressors and in the capacity to maintain muscle homeostasis, particularly in the context of co-morbidities (Desquilbet et al., 2007; Desquilbet et al., 2009).

Regulatory RNAs such as miRNAs have been implicated in aging-associated loss of muscle mass. For example, Drummund, et al observed dysregulated miRNA expression in skeletal muscle of elderly men following anabolic stimuli compared with younger men, suggesting that miRNA dysregulation (and potential targets) is correlated with a loss of muscle mass during aging (Drummond et al., 2008). However, further studies will be needed to establish a potential causal relationship. Circulating levels of inflammatory mediators (e.g., C-reactive protein, TNF-alpha, IL-1b and IL-6) also tend to increase with age (Finch and Morgan, 2007; Roubenoff et al., 2003). Indeed, elevated levels of IL-6 have been used to predict the development of sarcopenia in elderly men (Payette et al., 2003). Together these data suggest that alterations in miRNA expression and/or regulation of target mRNAs contribute to the age-associated inflammation observed in sarcopenia.

4.2. Myogenesis and the Muscle program

Skeletal muscle is composed of postmitotic, multinucleated, contractile myofibers formed through the process of myogenesis (Figure 5). Myogenesis is an ordered process whereby mononuclear muscle precursor cells exit the cell cycle, differentiate, and fuse with either existing myofibers or with each other to form new myofibers (Wagers and Conboy, 2005). Muscle precursor cells are derived from satellite cells, a myogenically committed population of cells which resides between the myofiber and the surrounding basal lamina (Bischoff, 1975; Mauro, 1961). Satellite cells are normally quiescent, but, upon exposure to appropriate growth stimuli, re-enter the cell cycle and give rise to muscle precursor cells (Charge and Rudnicki, 2004). It is these satellite cells that are primarily responsible for the regenerative capacity of skeletal muscle. Critical to their role as muscle stem cells, satellite cells are capable of undergoing self-renewal, thereby ensuring sufficient numbers of satellite cells for future regenerative needs (Cerletti et al., 2008).

Figure 5. Schematic of Myogenic program.

Satellite cell activation occurs following muscle damage, although the nature of the events leading to re-entry of the cell cycle have not been fully elucidated. HGF, which is present in the basal lamina surrouding myofibers, has been shown to definitively activate satellite cells in vitro and in vivo (Bischoff, 1986; Jennische et al., 1993). Additionally, modulation of nitric oxide levels affects the activation state of satellite cells (Wozniak and Anderson, 2007). Following activation, satellite cells proliferate, and their progeny are referred to as myoblasts. These cells rapidly downregulate satellite cell markers (Pax7) and upregulate expression of the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) Myf5, which is required for myoblast proliferation, and MyoD, necessary for cell cycle arrest and differentiation. Two additional MRFs, myogenin and MRF4, are required during differentiation for expression of contractile proteins (Berkes and Tapscott, 2005; Pownall et al., 2002). Following differentiation, myoblasts undergo cell-cell fusion to form multinucleated myotubes. There are two separate phases of fusion. Initially, during embryogenesis and regeneration, mononucleated myoblasts fuse with each other to form a multinucleated cell. During the second phase, myoblasts fuse with existing myofibers to increase myofiber size and nuclear number. In addition to occuring during embryonic development and regeneration, this process of fusion is active during muscle growth following atrophy and muscle maintenance (Jansen and Pavlath, 2008).

Satellite cells and mature muscle fiber cells produce chemoattractants (e.g., MCP-1, Fraktalkine, MDC, uPAR) that promote macrophage-mediated clearance of dead/apoptotic cells and myoblast proliferation through the release of local mediators (Goetsch et al., 2003; Massimino et al., 1997; Tidball, 2005). There is increasing data that inflammatory conditions in muscle are associated with infiltration of macrophages (for review, see (Tidball, 2005)) and evidence for muscle repair through cytokine-mediated signaling and cross-talk with muscle cells to promote myogenesis (Cantini and Carraro, 1995; Cantini et al., 1995; Massimino et al., 1997; Merly et al., 1999). In animal models the prevention of macrophage infiltration can blunt the repair process (Bondesen et al., 2004; Chazaud et al., 2003; Jejurikar and Kuzon, 2003; Lescaudron et al., 1999; Robertson et al., 1993; Summan et al., 2003).

4.3. RNA silencing, Myogenesis and Aging

RNA silencing by miRNAs plays an important role in skeletal muscle cell growth and differentiation. Three mRNAs, miR-1, miR-133, and miR-206 have emerged as key regulators of the myogenic program. While miR-1 and miR-206 promote differentiation of myogenic cells, miR-133 enhances proliferation while inhibiting differentiation (Chen et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2006). Additional evidence for the role of these miRNAs comes from the observations that expression of miR-206 is dysregulated in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy, while miR-1 and miR-133 expression is decreased during muscle hypertrophy (McCarthy, 2008; McCarthy and Esser, 2007). Conditional loss of microRNA biogenesis, wherein Dicer gene expression is selectively lost in skeletal muscle, results in perinatal lethality due to muscle hypoplasia, further supporting the importance of miRNAs in muscle development and function (O'Rourke et al., 2007). Since miRNA expression appears to change with age, it will be interesting to see how this activity influences muscle maintenance. The age-dependent decline in the ability of muscle to regenerate is primarily due to a decline in satellite cell function (Brack et al., 2007).

Satellite cell activation and proliferation are both impaired during regeneration of aged muscle relative to young muscle. Data from human studies suggest that satellite cell division declines with age (Renault et al., 2000), see Figure 6, and that the percentage of satellite cells in muscle decreases by as much as 50% between young (20s) to older (70s) (Kadi et al., 2004; Renault et al., 2002). Conboy and colleagues have attributed this decline to altered activity of the Notch/Delta/TGFb/Smad axis) (Carlson et al., 2008a; Conboy et al., 2003). While the extent to which these changes are due to accumulation of genetic damage in aged satellite cells or age-related changes in the surrounding microenvironment has not been entirely resolved, evidence suggests that changes in the microenvironment play the more significant role (Bockhold et al., 1998; Brack and Rando, 2007; Schultz and Lipton, 1982). For example, heterochronic parabiosis experiments, a technique wherein there is surgical fusion of young mice with the vasculature of old mice dramatically demonstrate the importance of the microenvironment on satellite cell function. In these studies, either the young or old mouse sharing a circulatory system were exposed to hindlimb muscle injury compared with parabiotic fusion of young-young or old-old. By measuring the regenerative response it was determined that the effectiveness of satellite cell activation and muscle regeneration was dependent on the surrounding environment; regeneration in the old mouse was improved by exposure to a young environment, while regeneration in the young mouse was impaired by exposure to an aged environment (Conboy et al., 2003). Recent studies support a role for the Notch-Delta signaling and Smad transcriptional regulators in this process (Carlson et al., 2008a; Carlson et al., 2008b). These experiments underscore a critical role for the microenvironment in influencing the capacity for regeneration. Furthermore, satellite cells from old mice exhibit fibrogenic tendencies. Both these characteristics of old satellite cells are reversed when exposed to a young environment (Brack and Rando, 2007; Charge and Rudnicki, 2004). These data indicate not only the existence of factors that positively influence satellite cell function, but those that negatively impact their function, as well. Identification of these positive factors may result in valuable therapeutic treatments for sarcopenia.

Figure 6.

Decline in human muscle satellite cell division with age (adapted from (Renault et al., 2000)).

5. Concluding remarks

In this review, we present evidence that RNA surveillance, including RNA interference (RNAi, e.g., miRNA, siRNA) and RNA editing (RNAe, e.g., ADARs) are determinants of longevity and lifespan. We describe multiple studies that show microRNA expression patterns and RNA editing patterns change with age in nematodes, mice and humans. We describe recent data demonstrating that variants in stress response ADAR genes are linked to exceptional longevity in humans. We also show that loss of function in homologues of ADAR reduce lifespan in C. elegans. In those studies, we have found that further knockdown of RNA interference argonaute genes, i.e., RDE-1 or RDE-4 restore lifespan, suggesting that RNAe and RNAi interact to modulate the RNA transcriptome, with effects on lifespan. Collectively, these results suggest that ADARs and microRNAs play an important role in longevity, potentially by buffering the response of cells to stressors. All metazoa experience cellular stress, and cellular stressors, including dsRNA (e.g. viral infection), inflammatory cytokines, and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Interestingly, stress induced apoptosis has also been associated with loss of ADAR, suggesting that ADAR may act to buffer cellular stressors (Hartner et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2004). Because dsRNA-binding proteins can form heteromers, direct interaction between ADAR and PKR is possible, providing a mechanistic basis for the modulation of PKR activity and buffering of stress responses by ADAR. The notion that disease severity can be viewed as a form of stress management seems intuitively sensible and is consistent with our observations that centenarians appear to compress disease to their later years.

The majority of miRNAs are predicted to bind numerous targets and in many cases regulate a group of genes with similar functions. These aspects of miRNAs therefore provide of the capacity for complex transcriptional control. The functions of only a few miRNAs have been discerned, revealing that these small regulatory molecules control fundamental biological activities such as cell proliferation, cell differentiation, cell death, cell signaling, stress response and metabolism. The well recognized effects of aging on skeletal muscle, and the experimental tools available for this tissue render it highly relevant in the evaluation and identification of RNA surveillance factors involved in aging and the development of age-related frailty (Carlson and Conboy, 2007; Carlson et al., 2008b).

RNA surveillance may be an example of a robust dynamic system. The notion of robustness in biological systems has been described as the capacity to adapt to environmental cues and to maintain homeostatic stability in response to perturbation and stress (Kitano, 2007). A decline in robustness resembles the frailty phenotype, since frailty also represents a reduced capacity to manage environmental stressors to maintain tissue homeostasis (Desquilbet et al., 2007). The evolution of robust systems is not without comprise and trade-offs (Kitano, 2007). There is abundant evidence for trade-offs in lifespan studies. For example, increased expression of SIRT1, a deacetylase is associated with increased lifespan by mimicking caloric restriction. However, animals with increased SIRT1 are also hypersensitive to LPS and influenza infection (Imai, 2009).

The RNA surveillance system also is likely to represent a dynamic balance of trade-offs. Early studies demonstrated that RNAi provides clear innate immune protective effects; however, over expression of RNAi/microRNA is clearly deleterious (Grimm et al., 2006). Loss of RNA editors (e.g., ADAR) results in premature mortality (Montano et al., 2009), but over-expression of ADAR is assocated with lethality (Keegan et al., 2005). These data reinforce the concept of “antagonistic pleiotropy” first proposed by GC Williams in 1957, to describe the duality of biologic features with selective advantage early in life that also have undesired features that are deleterious later in life (Williams, 1957). Such trade-offs may represent a robustness-frailty axis that underlies complex systems (Kitano, 2007) and innate regulatory pathways (Libert et al., 2006), with likely many more pathways to be discovered. Given the complexity and interconnectedness of the RNA surveillance system, any perturbation in this dynamic system to promote longevity, for example through therapeutic intervention, will undoubtedly have unexpected trade-offs that will need to be carefully evaluated to achieve longevity and a healthspan balance.

Figure 2. Schematic of RNA regulatory pathways.

a) RNA interference (RNAi) pathway and, b) RNA editing (RNAe) pathway.

REFERENCES

- Bass BL. RNA editing by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:817–846. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass BL. How does RNA editing affect dsRNA-mediated gene silencing?. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol; 2006. pp. 285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass BL, Weintraub H. An unwinding activity that covalently modifies its double-stranded RNA substrate. Cell. 1988;55:1089–1098. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90253-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes CA, Tapscott SJ. MyoD and the transcriptional control of myogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff R. Regeneration of single skeletal muscle fibers in vitro. Anat Rec. 1975;182:215–235. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091820207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff R. Proliferation of muscle satellite cells on intact myofibers in culture. Dev Biol. 1986;115:129–139. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockhold KJ, Rosenblatt JD, Partridge TA. Aging normal and dystrophic mouse muscle: analysis of myogenicity in cultures of living single fibers. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21:173–183. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199802)21:2<173::aid-mus4>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm M, Slack F. A developmental timing microRNA and its target regulate life span in C. elegans. Science. 2005;310:1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1115596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondesen BA, Mills ST, Kegley KM, Pavlath GK. The COX-2 pathway is essential during early stages of skeletal muscle regeneration. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2004;287:C475–C483. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00088.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack AS, Conboy MJ, Roy S, Lee M, Kuo CJ, Keller C, Rando TA. Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science. 2007;317:807–810. doi: 10.1126/science.1144090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack AS, Rando TA. Intrinsic changes and extrinsic influences of myogenic stem cell function during aging. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:226–237. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-9000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNA functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantini M, Carraro U. Macrophage-released factor stimulates selectively myogenic cells in primary muscle culture. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 1995;54:121–128. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199501000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantini M, Massimino ML, Rapizzi E, Rossini K, Catani C, Dalla Libera L, Carraro U. Human satellite cell proliferation in vitro is regulated by autocrine secretion of IL-6 stimulated by a soluble factor(s) released by activated monocytes. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;216:49–53. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ME, Conboy IM. Loss of stem cell regenerative capacity within aged niches. Aging Cell. 2007;6:371–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ME, Hsu M, Conboy IM. Imbalance between pSmad3 and Notch induces CDK inhibitors in old muscle stem cells. Nature. 2008a;454:528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature07034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ME, Silva HS, Conboy IM. Aging of signal transduction pathways, and pathology. Exp Cell Res. 2008b;314:1951–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerletti M, Shadrach JL, Jurga S, Sherwood R, Wagers AJ. Regulation and function of skeletal muscle stem cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol; 2008. pp. 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charge SB, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:209–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazaud B, Sonnet C, Lafuste P, Bassez G, Rimaniol AC, Poron F, Authier FJ, Dreyfus PA, Gherardi RK. Satellite cells attract monocytes and use macrophages as a support to escape apoptosis and enhance muscle growth. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1133–1143. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2006;38:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clop A, Marcq F, Takeda H, Pirottin D, Tordoir X, Bibe B, Bouix J, Caiment F, Elsen JM, Eychenne F, et al. A mutation creating a potential illegitimate microRNA target site in the myostatin gene affects muscularity in sheep. Nat Genet. 2006;38:813–818. doi: 10.1038/ng1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Smythe GM, Rando TA. Notch-mediated restoration of regenerative potential to aged muscle. Science. 2003;302:1575–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1087573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, Phair JP, Jamieson BD, Holloway M, Margolick JB. HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1279–1286. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.11.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desquilbet L, Margolick JB, Fried LP, Phair JP, Jamieson BD, Holloway M, Jacobson LP. Relationship between a frailty-related phenotype and progressive deterioration of the immune system in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:299–306. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181945eb0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond MJ, McCarthy JJ, Fry CS, Esser KA, Rasmussen BB. Aging differentially affects human skeletal muscle microRNA expression at rest and after an anabolic stimulus of resistance exercise and essential amino acids. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1333–E1340. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90562.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch CE, Morgan TE. Systemic inflammation, infection, ApoE alleles, and Alzheimer disease: a position paper. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4:185–189. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AL. Of worms and women: sarcopenia and its role in disability and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1185–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S, Rasmussen BB, Cadenas JG, Drummond MJ, Glynn EL, Sattler FR, Volpi E. Aerobic exercise overcomes the age-related insulin resistance of muscle protein metabolism by improving endothelial function and Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. Diabetes. 2007;56:1615–1622. doi: 10.2337/db06-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetsch SC, Hawke TJ, Gallardo TD, Richardson JA, Garry DJ. Transcriptional profiling and regulation of the extracellular matrix during muscle regeneration. Physiological Genomics. 2003;14:261–271. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00056.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, Storm TA, Pandey K, Davis CR, Marion P, Salazar F, Kay MA. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habig JW, Dale T, Bass BL. miRNA editing--we should have inosine this coming. Mol Cell. 2007;25:792–793. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner JC, Walkley CR, Lu J, Orkin SH. ADAR1 is essential for the maintenance of hematopoiesis and suppression of interferon signaling. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:109–115. doi: 10.1038/ni.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon LA, Schmeissner PJ, Dudaronek JM, Brown PA, Listner KM, Sakano Y, Paupard MC, Hall DH, Driscoll M. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature. 2002;419:808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough RF, Bass BL. Analysis of Xenopus dsRNA adenosine deaminase cDNAs reveals similarities to DNA methyltransferases. Rna. 1997;3:356–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez-Ventoso C, Yang M, Guo S, Robins H, Padgett RW, Driscoll M. Modulated microRNA expression during adult lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2006;5:235–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S. SIRT1 and caloric restriction: an insight into possible trade-offs between robustness and frailty. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12:350–356. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32832c932d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen KM, Pavlath GK. Molecular control of mammalian myoblast fusion. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;475:115–133. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-250-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jejurikar SS, Kuzon WM., Jr Satellite cell depletion in degenerative skeletal muscle. Apoptosis. 2003;8:573–578. doi: 10.1023/A:1026127307457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennische E, Ekberg S, Matejka GL. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor in growing and regenerating rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C122–C128. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.1.C122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadi F, Charifi N, Denis C, Lexell J. Satellite cells and myonuclei in young and elderly women and men. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29:120–127. doi: 10.1002/mus.10510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakelides H, Nair KS. Sarcopenia of aging and its metabolic impact. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;68:123–148. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)68005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y, Megraw M, Kreider E, Iizasa H, Valente L, Hatzigeorgiou AG, Nishikura K. Frequency and fate of microRNA editing in human brain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5270–5280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y, Zinshteyn B, Chendrimada TP, Shiekhattar R, Nishikura K. RNA editing of the microRNA-151 precursor blocks cleavage by the Dicer-TRBP complex. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:763–769. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan LP, Brindle J, Gallo A, Leroy A, Reenan RA, O'Connell MA. Tuning of RNA editing by ADAR is required in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2005;24:2183–2193. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Lee YS, Sivaprasad U, Malhotra A, Dutta A. Muscle-specific microRNA miR-206 promotes muscle differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:677–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U, Wang Y, Sanford T, Zeng Y, Nishikura K. Molecular cloning of cDNA for double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase, a candidate enzyme for nuclear RNA editing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11457–11461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H. Towards a theory of biological robustness. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:137. doi: 10.1038/msb4100179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescaudron L, Peltekian E, Fontaine-Perus J, Paulin D, Zampieri M, Garcia L, Parrish E. Blood borne macrophages are essential for the triggering of muscle regeneration following muscle transplant. Neuromuscular Disorders. 1999;9:72–80. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(98)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libert S, Chao Y, Chu X, Pletcher SD. Trade-offs between longevity and pathogen resistance in Drosophila melanogaster are mediated by NFkappaB signaling. Aging Cell. 2006;5:533–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano DJ, Mirsky H, Vendetti NJ, Maas S. RNA editing of a miRNA precursor. RNA. 2004;10:1174–1177. doi: 10.1261/rna.7350304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund J, Tedesco P, Duke K, Wang J, Kim SK, Johnson TE. Transcriptional profile of aging in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1566–1573. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas S, Kawahara Y, Tamburro KM, Nishikura K. A-to-I RNA editing and human disease. RNA Biol. 2006;3:1–9. doi: 10.4161/rna.3.1.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield JH, Harfe BD, Nissen R, Obenauer J, Srineel J, Chaudhuri A, Farzan-Kashani R, Zuker M, Pasquinelli AE, Ruvkun G, et al. MicroRNA-responsive 'sensor' transgenes uncover Hox-like and other developmentally regulated patterns of vertebrate microRNA expression. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1079–1083. doi: 10.1038/ng1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimino ML, Rapizzi E, Cantini M, Libera LD, Mazzoleni F, Arslan P, Carraro U. ED2+ macrophages increase selectively myoblast proliferation in muscle cultures. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:754–759. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;9:493–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JJ. MicroRNA-206: the skeletal muscle-specific myomiR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:682–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JJ, Esser KA. MicroRNA-1 and microRNA-133a expression are decreased during skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:306–313. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00932.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merly F, Lescaudron L, Rouaud T, Crossin F, Gardahaut MF. Macrophages enhance muscle satellite cell proliferation and delay their differentiation. Muscle & Nerve. 1999;22:724–732. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199906)22:6<724::aid-mus9>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano M, Sebastiani P, Puca A, Timofeev N, Kojima T, Wang M, Melista E, Meltzer M, Fischer S, Anderson S, et al. RNA Editing Genes Associated With Extreme Old Age in Humans and With Lifespan in C. elegans. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(12):e8210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse DP, Aruscavage PJ, Bass BL. RNA hairpins in noncoding regions of human brain and Caenorhabditis elegans mRNA are edited by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7906–7911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112704299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, Fraser A, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Li H, Kenyon C. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424:277–283. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikura K. Editor meets silencer: crosstalk between RNA editing and RNA interference. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:919–931. doi: 10.1038/nrm2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke JR, Georges SA, Seay HR, Tapscott SJ, McManus MT, Goldhamer DJ, Swanson MS, Harfe BD. Essential role for Dicer during skeletal muscle development. Dev Biol. 2007;311:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino MJ, Keegan LP, O'Connell MA, Reenan RA. dADAR, a Drosophila double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase is highly developmentally regulated and is itself a target for RNA editing. Rna. 2000;6:1004–1018. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge L, Gems D. The evolution of longevity. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R544–R546. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payette H, Roubenoff R, Jacques PF, Dinarello CA, Wilson PW, Abad LW, Harris T. Insulin-like growth factor-1 and interleukin 6 predict sarcopenia in very old community-living men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1237–1243. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pownall ME, Gustafsson MK, Emerson CP., Jr Myogenic regulatory factors and the specification of muscle progenitors in vertebrate embryos. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:747–783. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renault V, Piron-Hamelin G, Forestier C, DiDonna S, Decary S, Hentati F, Saillant G, Butler-Browne GS, Mouly V. Skeletal muscle regeneration and the mitotic clock. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:711–719. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renault V, Thornell LE, Butler-Browne G, Mouly V. Human skeletal muscle satellite cells: aging, oxidative stress and the mitotic clock. Experimental Gerontology. 2002;37:1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson TA, Maley MA, Grounds MD, Papadimitriou JM. The role of macrophages in skeletal muscle regeneration with particular reference to chemotaxis. Experimental Cell Research. 1993;207:321–331. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubenoff R, Parise H, Payette HA, Abad LW, D'Agostino R, Jacques PF, Wilson PW, Dinarello CA, Harris TB. Cytokines, insulin-like growth factor 1, sarcopenia, and mortality in very old community-dwelling men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Med. 2003;115:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryall JG, Schertzer JD, Lynch GS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness. Biogerontology. 2008;9:213–228. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmauss C, Howe JR. RNA editing of neurotransmitter receptors in the mammalian brain. Sci STKE. 2002;2002 doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.133.pe26. PE26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz E, Lipton BH. Skeletal muscle satellite cells: changes in proliferation potential as a function of age. Mech Ageing Dev. 1982;20:377–383. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(82)90105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani P, Zhao JQ, Abad-Grau M, Riva A, Hartley S, Sedgewick A, Doria A, Montano M, Perls T, Steinberg M, et al. A Hierarchical and Modular Approach to the Discovery of Robust Associations in Genome-Wide Association Studies from Pooled DNA Samples. BMC Genetics. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-6. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavov D, Clark M, Gardiner K. Comparative analysis of the RED1 and RED2 A-to-I RNA editing genes from mammals, pufferfish and zebrafish. Gene. 2000;250:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkoly E, Stahle M, Pivarcsi A. MicroRNAs and immunity: novel players in the regulation of normal immune function and inflammation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summan M, McKinstry M, Warren GL, Hulderman T, Mishra D, Brumbaugh K, Luster MI, Simeonova PP. Inflammatory mediators and skeletal muscle injury: a DNA microarray analysis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:237–245. doi: 10.1089/107999003321829953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00454.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Model organisms as a guide to mammalian aging. Dev Cell. 2002;2:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin LA, Bass BL. Mutations in RNAi rescue aberrant chemotaxis of ADAR mutants. Science. 2003;302:1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1091340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin LA, Saccomanno L, Morse DP, Brodigan T, Krause M, Bass BL. RNA editing by ADARs is important for normal behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2002;21:6025–6035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Parker R. Control of translation and mRNA degradation by miRNAs and siRNAs. Genes Dev. 2006;20:515–524. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente L, Nishikura K. ADAR gene family and A-to-I RNA editing: diverse roles in posttranscriptional gene regulation. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2005;79:299–338. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)79006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers AJ, Conboy IM. Cellular and molecular signatures of muscle regeneration: current concepts and controversies in adult myogenesis. Cell. 2005;122:659–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Miyakoda M, Yang W, Khillan J, Stachura DL, Weiss MJ, Nishikura K. Stress-induced apoptosis associated with null mutation of ADAR1 RNA editing deaminase gene. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4952–4961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R, Kayo T, Lee CK, Prolla TA. Gene expression profiling of aging using DNA microarrays. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:177–193. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC. Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution. 1957;11:398–411. [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak AC, Anderson JE. Nitric oxide-dependence of satellite stem cell activation and quiescence on normal skeletal muscle fibers. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:240–250. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JH, Luo X, Nie Y, Su Y, Zhao Q, Kabir K, Zhang D, Rabinovici R. Widespread inosine-containing mRNA in lymphocytes regulated by ADAR1 in response to inflammation. Immunology. 2003;109:15–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Chendrimada TP, Wang Q, Higuchi M, Seeburg PH, Shiekhattar R, Nishikura K. Modulation of microRNA processing and expression through RNA editing by ADAR deaminases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:13–21. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarasheski KE. Exercise, aging, and muscle protein metabolism. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:M918–M922. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.10.m918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]