Abstract

By rapid hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, acetylcholinesterase terminates neurotransmission at cholinergic synapses. Acetylcholinesterase is a very fast enzyme, functioning at a rate approaching that of a diffusion-controlled reaction. The powerful toxicity of organophosphate poisons is attributed primarily to their potent inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are utilized in the treatment of various neurological disorders, and are the principal drugs approved thus far by the FDA for management of Alzheimer’s disease. Many organophosphates and carbamates serve as potent insecticides, by selectively inhibiting insect acetylcholinesterase. The determination of the crystal structure of Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase permitted visualization, for the first time, at atomic resolution, of a binding pocket for acetylcholine. It also allowed identification of the active site of acetylcholinesterase, which, unexpectedly, is located at the bottom of a deep gorge lined largely by aromatic residues. The crystal structure of recombinant human acetylcholinesterase in its apo-state is similar in its overall features to that of the Torpedo enzyme; however, the unique crystal packing reveals a novel peptide sequence which blocks access to the active-site gorge.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase, nerve agent, X-ray crystallography

1. Introduction

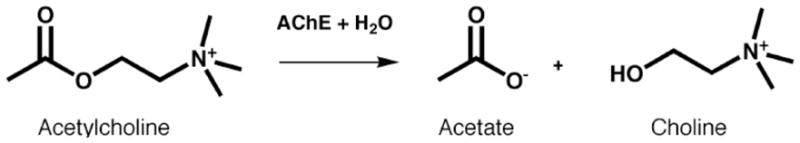

The principal biological role of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is termination of impulse transmission at cholinergic synapses by rapid hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter, acetylcholine (ACh) [1] (Fig. 1). In keeping with this requirement, AChE possesses a remarkably high specific activity, functioning at a rate approaching that of a diffusion-controlled reaction [2]. The powerful acute toxicity of organophosphorus (OP) poisons is due primarily to the fact that they are potent irreversible inhibitors of AChE, forming a covalent bond with a serine residue at the active site [2]. AChE inhibitors are used in treatment of various neuromuscular disorders [3], and have provided the first generation of drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease [4]. Knowledge of the 3D structure of AChE is, therefore, essential for understanding its remarkable catalytic efficacy, for rational drug design, and for developing therapeutic approaches to OP intoxication. Furthermore, structural information about the ACh-binding site of AChE can help us understand the molecular basis for the recognition of ACh by other ACh-binding proteins such as the muscarinic and nicotinic ACh receptors [5].

Figure 1.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of ACh by AChE.

The various oligomeric forms of AChE in the electric organs of the electric fish, Electrophorus and Torpedo, are structurally similar to those in vertebrate nerve and muscle [6]. Highly purified preparations obtained from these abundant sources of AChE [7] have taught us much about the number and arrangement of subunits and modes of anchoring to the surface membrane of these molecular forms [8]. They have also yielded considerable information concerning the surface topography of AChE [9] and its mechanism of action [2].

Early kinetic studies indicated that the active site of AChE contains two subsites, the ‘esteratic’ and ‘anionic’ subsites [10], corresponding, respectively, to the catalytic machinery and the choline-binding pocket. The ‘esteratic’ subsite was believed to resemble the catalytic subsites of other serine hydrolases [11, 12]. The active-site serine, with which OPs react, was unequivocally established to be S200 in Torpedo californica AChE (TcAChE) [13]. Both kinetic [14] and chemical studies implicated a histidine residue in the active site. The ‘anionic’ subsite interacts with the charged quaternary group of the choline moiety of ACh, and was believed to be the binding site both for quaternary ligands, such as edrophonium [15] and N-methylacridinium [16], which act as competitive inhibitors, and for quaternary oximes, which serve as effective reactivators of organophosphate-inhibited AChE [12]. Both chemical modification and spectroscopic studies supported the presence of aromatic residues in the active site of AChE [17–20].

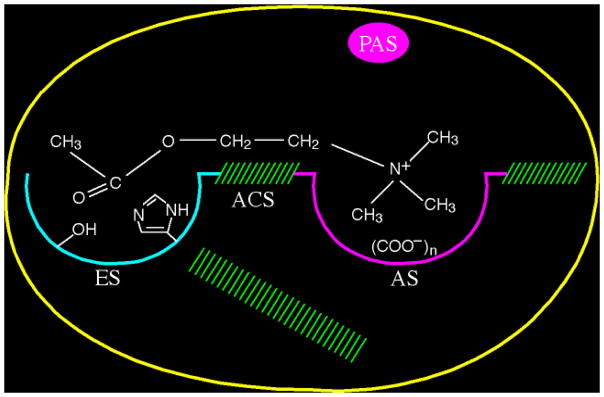

In addition to the two subsites of the catalytic center, AChE was shown to possess one or more additional binding sites for ACh and for other quaternary ligands (Fig. 2). Such ‘peripheral’ anionic site(s), clearly distinct from the choline-binding pocket of the active site, had been proposed [16, 21, 22], and were firmly established by Taylor and Lappi [23], by use of the fluorescent probe, propidium, which binds at a peripheral anionic site (PAS) distinct from that occupied by the monoquaternary competitive inhibitors mentioned above. Reiner and coworkers [24] suggested that this is the site involved in the substrate inhibition characteristic of AChE. Rosenberry and coworkers [25] showed that acetylthiocholine (ATCh) bound transiently to this PAS as the first step in the catalytic pathway and that such binding, at higher ATCh concentrations, gave rise to substrate inhibition. However, at lower substrate concentrations, substrate binding to the PAS could actually accelerate the acylation step in the catalytic pathway [26].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the binding sites of AChE based upon biochemical studies performed prior to determination of the 3D structure. ES, esteratic site; AS, anionic substrate binding site; ACS, aromatic cation binding site; PAS, peripheral anionic binding site. The hatched areas represent putative hydrophobic binding regions. ACh is shown spanning the esteratic and anionic sites of the catalytic center. Imidazole and hydroxyl side chains of His and Ser are shown within the esteratic site. Within the anionic site, (COO−)n represents 6–9 putative negative charges.

The first AChE crystals obtained were of a tetrameric form purified from electric organ tissue of Electrophorus electricus [27]. Although their preliminary characterization was reported [28] [29], no structural data were obtained. The first crystal structure, that of TcAChE, was determined in 1991 [30]. This was followed by a series of 3D structures of TcAChE complexed with a broad repertoire of inhibitors, including anti-Alzheimer drugs [4], as well as the structures of mouse [31] and Drosophila [32] AChE, and those of human [33], Torpedo [34] and mouse [35] AChE complexed with the snake venom toxin, fasciculin.

Here we present the key findings that emerged from the structural studies on AChE, and discuss how they have forwarded our understanding of its mode of action. We also report, for the first time, the 3D structure of recombinant human AChE (rhAChE) in its apo state.

2. Material and Methods

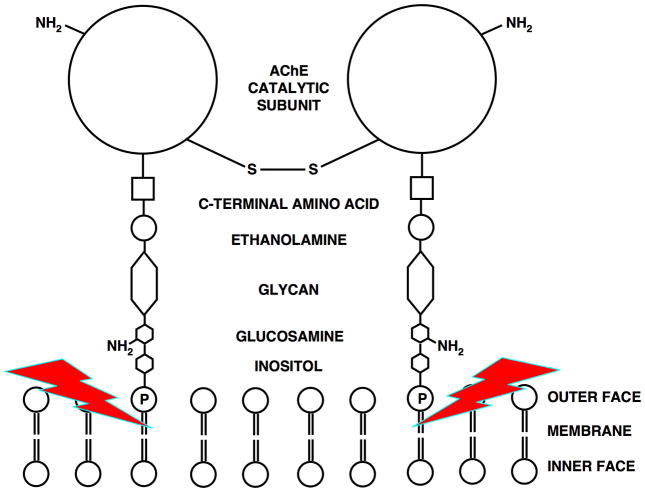

In Torpedo, a major form of AChE is a homodimer attached to the plasma membrane via a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor [8]. The GPI is covalently attached to the C-terminus of each monomer, with the phosphatidylinositol (PI) moiety serving as the hydrophobic anchor [8]. The dimer can be selectively solubilized by a bacterial PI-specific phospholipase C [36] (Fig. 3). This mild procedure yields significant purification prior to the affinity chromatography step [37]. We were thus able to obtain large amounts of pure, un-nicked enzyme for crystallization trials, which indeed resulted in diffracting crystals of TcAChE [37].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the GPI-anchored TcAChE dimer. The red lightning bolts indicate the site of hydrolysis by a bacterial PI-specific phospholipase C [36].

rhAChE was produced as described previously [38]. Briefly, the catalytic subunit, consisting of 556 residues, with an apparent molecular weight of ~70 kDa, was expressed in Drosophila S2 cells. Purification was performed by affinity chromatography on an acridinium resin from which the enzyme was eluted with decamethonium. SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions revealed a prominent 130 kDa band that corresponded to a disulfide-linked dimer [38].

Crystals of rhAChE were grown using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method, at 4°C, by mixing the protein solution with an equal volume of the reservoir solution (1.3–1.5M LiSO4/0.1M N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid [HEPES], pH 6.8–7.0). Specifically, 2μl reservoir were mixed with 2 μl of protein (at ~7 mg/ml). Prior to X-ray data collection, at 100 K, crystals were cryo-protected with 20% glycerol in the mother liquor. A complete data set was collected to 3.2 Å resolution on beamline ID14–4 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble. Indexing and integration with DENZO, and scaling with SCALEPACK [39], indicated a hexagonal space group P61 (see Table 1). The structure was solved by molecular replacement with MOLREP [40], using, as a search model, the coordinates (1B41) of the monomer rhAChE structure solved in complex with fasciculin-II [33]. The top two peaks of the cross rotation function (31.1–3.5 Å resolution) were clearly distinct from the rest. Translation search showed that these two peaks correspond to two crystallographically independent monomers in the asymmetric unit (ASU), yielding an R-factor of 41.7% and a correlation coefficient of 60.9%. Rigid body refinement in CNS [41], using data to 4 Å resolution, yielded an R-factor of 31.9%. Protein atoms were initially refined in CNS by simulated annealing, imposing strict non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS), followed by a few cycles of conjugate gradient minimization, together with manual adjustment and addition of water molecules using the program O [42]. Releasing the NCS constrains after several such cycles significantly lowered the free R-factor. The structure was further refined with REFMAC [43] and fitted with COOT [44], yielding an overall R-factor of 20.0%, and an Rfree of 24.6%. X-ray data and processing statistics are displayed in Table 1, and refinement and model statistics in Table 2. The refined coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the PDB with the ID 3LII.

Table 1.

X-ray Data Collection and Processing Statistics for rhAChE crystal

| Space group | P61 |

| Molecules in asymmetric unit | 2 |

| Cell axes (Å) and angles (°) | 210.9 210.9 115.3, 90 90 120 |

| X-ray source, beamline, wavelength (Å) | ESRF, ID-14-4, 0.93 |

| Temperature | 100°K |

| Diffraction limits (Å) | 31.1–3.2 |

| Number of measured reflections | 482,340 |

| Number of unique reflections | 47,979 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.25 |

| Multiplicity | 5.5 |

| Completeness: all data (highest shell*) | 99.9 % (100 %) |

| Rsym: all data (highest shell) | 8.3% (47.5 %) |

| I/sigma: all data (highest shell) | 15.1 (3.5) |

Highest resolution shell is 3.31–3.2 Å.

Table 2.

Refinement and Model Statistics on rhAChE crystal structure

| Number of reflections used (free) | 45,612 (2,365) |

| Number of protein residues | 2×543 |

| Number of solvent atoms | 106 |

| Rfact (Rfree) F>0s | 20.9%, 24.6% |

| B-factor (Å2) | 31.5 |

| Rms bond length (Å) | 0.008 |

| Rms bond angle (°) | 1.5 |

| ESD from Luzzati plot (Å) | 0.34 |

| Ramachandran analysisa (%) | |

| Core | 81.3 |

| Allowed | 17.8 |

| Generously allowed | 0.9 |

| Disallowed | 0.0 |

Calculated using PROCHECK [45]

3.1 General Structure of TcAChE

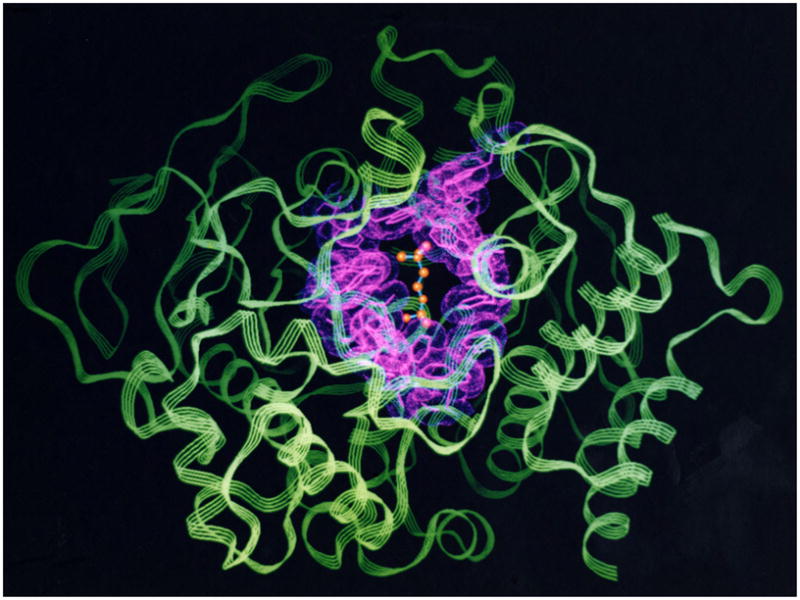

TcAChE was seen to be an ellipsoid with dimensions ~45 × 60 × 65 Å. It belongs to the class of α/β proteins [46], and consists of a 12-stranded central mixed β-sheet surrounded by 14 α-helices. What is most striking in the structure is a deep and narrow gorge leading to the active site, which is lined by the rings of 14 conserved aromatic residues (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

3D structure of TcAChE displayed as a ribbon diagram. The 14 conserved aromatic residues are shown as pink sticks and a dot surface. A model of the substrate, ACh, bound in the active site, is shown at the bottom of the active-site gorge, in ball-and-stick format.

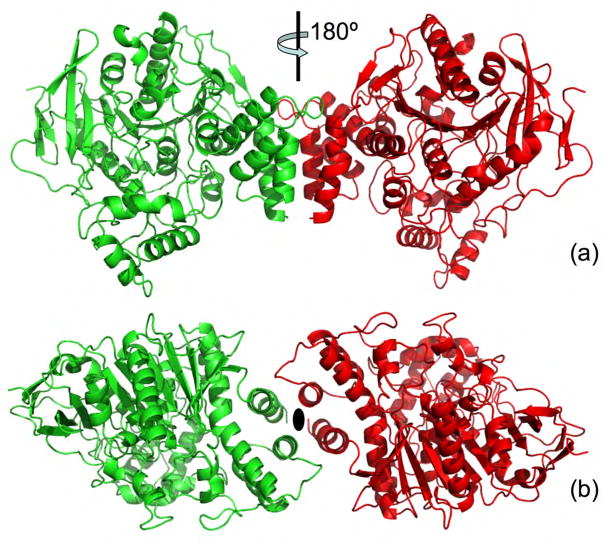

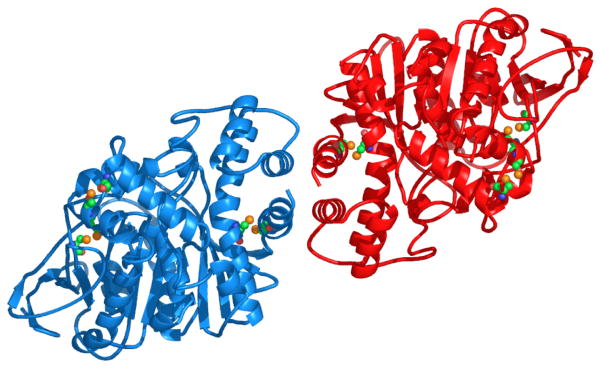

The AChE homodimer (Fig. 5), whose subunits are related by a crystallographic 2-fold axis, is held together by a four-helix bundle composed of helices αF′3 and αH from each subunit (nomenclature defined in ref [47]). The only inter-chain disulfide involves C-terminal C536 [48].

Figure 5.

Cartoon representation of the TcAChE dimer, with one monomer colored green and the other red. (a) View along the 2-fold axis; (b) View down the 2-fold axis. This type of dimer, held together by a 4-helix bundle as observed in the TcAChE structure [30], is virtually identical to that seen in the mouse [31] and Drosophila [32] AChE structures, as well as in the structures of human [33] and mouse [35] AChE complexed with the snake venom toxin, fasciculin.

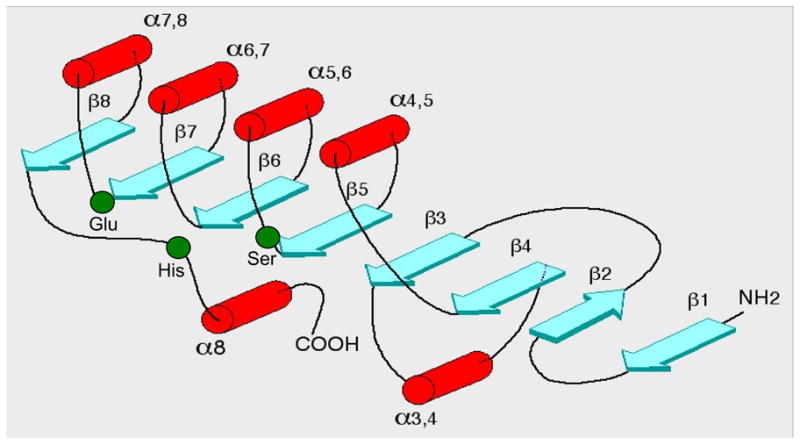

When the TcAChE structure was determined, it initially appeared to be an entirely new fold. However, its fold soon turned out to be strikingly similar to those of four other proteins whose structures had also been solved at about the same time: dienelactone hydrolase (DLH) [49], wheat serine carboxypeptidase-II (CPDW-II) [50], Geotrichum candidum lipase (GLIP) [51] and haloalkane dehalogenase [52]. A thorough discussion of the fascinating similarity of these five enzymes, that are the prototype members of the α/β hydrolase fold family (Fig. 6), is presented by Ollis et al. [47], and a comprehensive compendium of all members of this family can be seen at the “Esther Database” (http://bioweb.ensam.inra.fr/ESTHER/general?what=index) [53].

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the topological secondary structure of the α/β hydrolase fold. The α-helices are shown as red cylinders, the β-strands as turquoise arrows, and the three residues making up the active site are shown as green circles (the labels of Ser, Glu and His correspond to the catalytic-triad residues found in the AChE active-site).

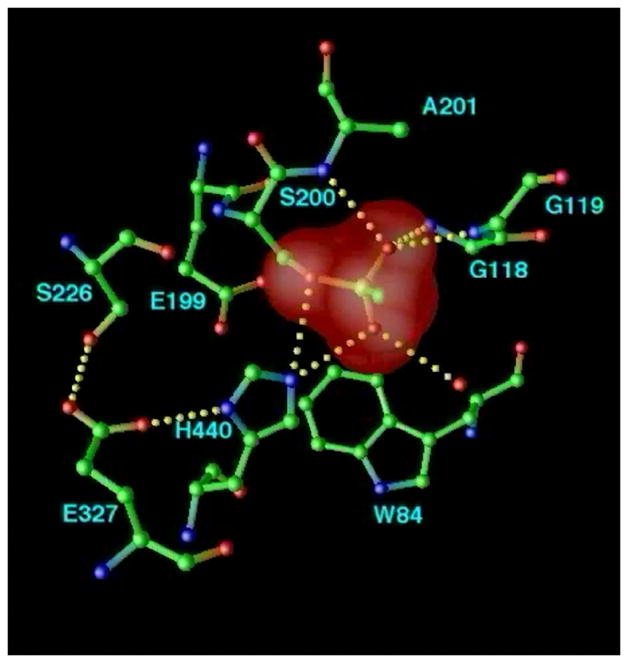

3.2 Active Site

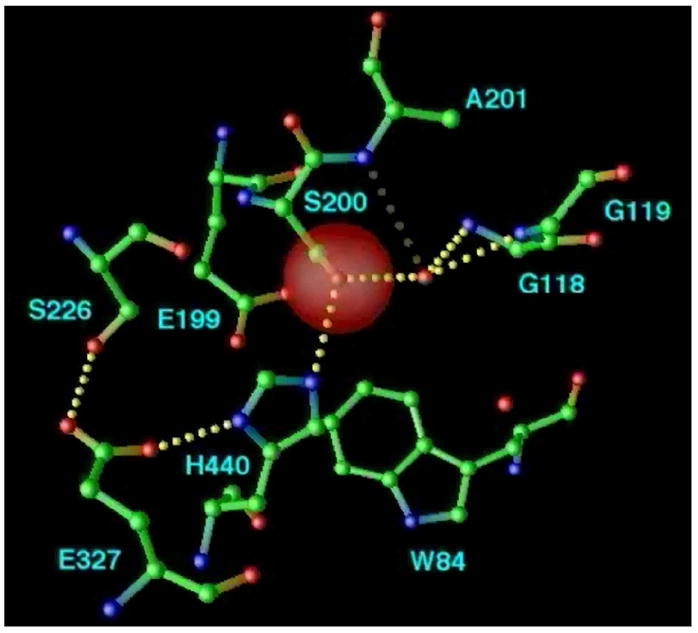

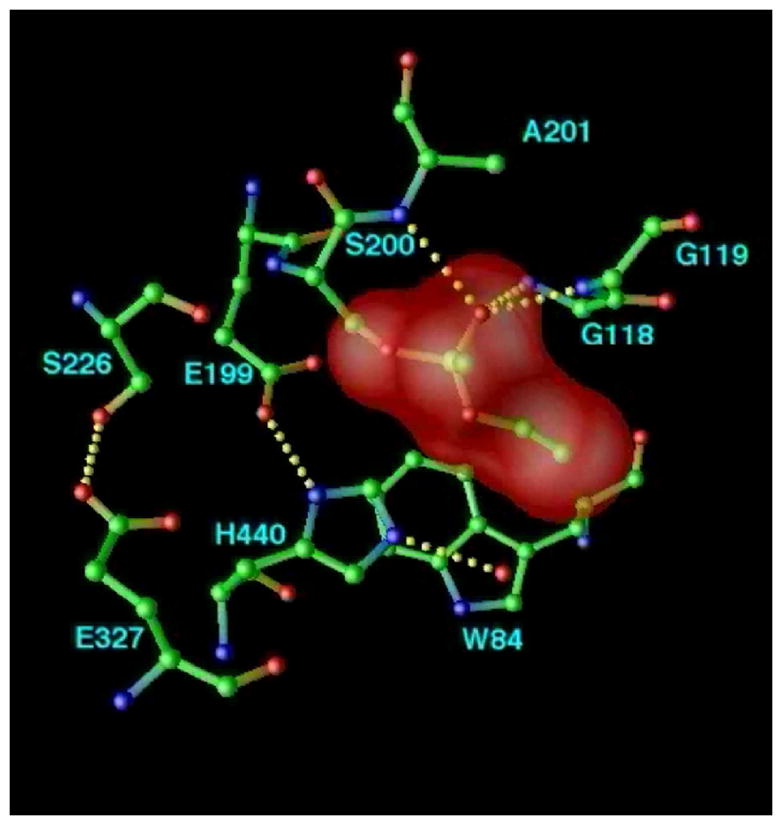

The existence of a catalytic triad in AChE had previously been the subject of controversy [2]. The 3D structure of TcAChE showed clearly that the active site consists of S200, E327 and H440 (Fig. 6). The three residues form a planar array, which closely resembles the catalytic triad of chymotrypsin (Cht) and of other serine proteases [54], although it is of the opposite ‘handedness’ to that of Cht [55] (see Fig. 6a in ref [30]). This suggested that the oxyanion hole, which is formed by the amide NH of the active-site serine in the serine proteases, would be formed by the amide NH of the following C-terminal residue, A201 in AChE, as appears to be the case for human pancreatic lipase [56] and for the other structurally related hydrolases [47]. All three triad residues occur within highly conserved regions of the sequence and, as is typical of active sites in α/β-proteins [57], are in loops following the C-termini of β-strands.

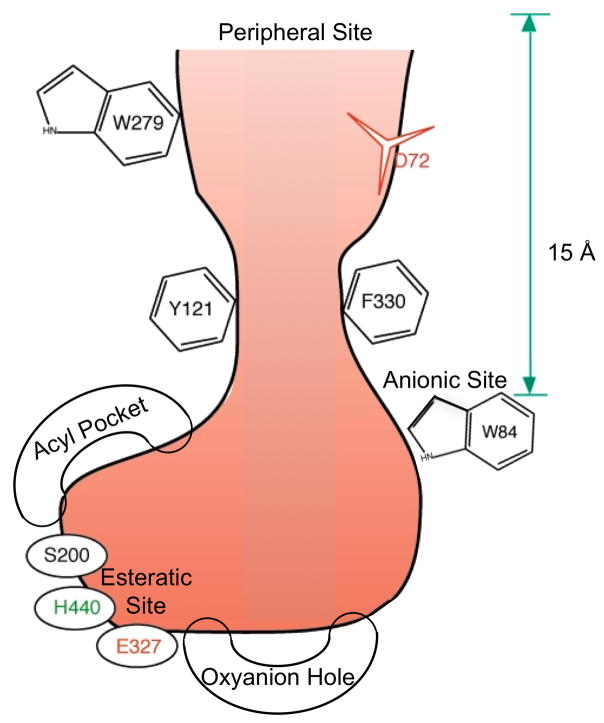

3.3 The Active-Site Gorge

The most remarkable feature of the structure of TcAChE, and of other AChEs, is a deep and narrow gorge, about 20 Å long, which penetrates more than halfway into the enzyme, and widens out close to its base (Fig. 7). We named this cavity the ‘active-site gorge’ because it contains the AChE catalytic triad near its bottom. S200-Oγ, which can be seen looking down the gorge from the surface of the enzyme, is about 4 Å above the base of the gorge. The rings of 14 aromatic residues contribute a substantial portion (~40%) of the surface of the gorge (Fig. 4). These residues, and their flanking sequences, which are highly conserved in AChEs from different species, come from residues as far apart as N66 and I444, and are synthesized on the first exon, which codes for residues 1–480 [58]. It should be noted that the gorge contains only a few acidic residues, which include D285 and E273 at the very top, D72, hydrogen-bonded to Y334, about half way down, and E199, near the base.

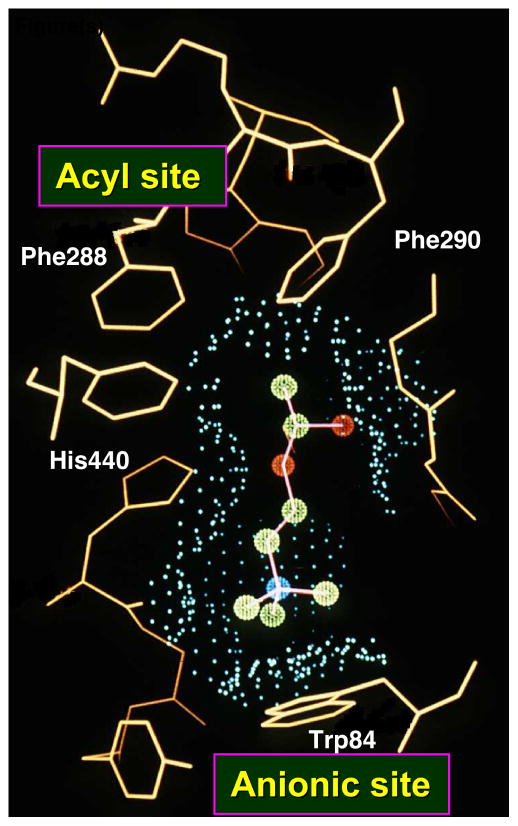

Figure 7.

Schematic view of the active-site gorge of TcAChE. The bottom of the gorge is characterized by several sub-sites: the anionic site, with which the choline moiety of ACh interacts; the esteratic site, which contains the three residues of the catalytic triad; the oxyanion hole, and the acyl pocket, which confers substrate specificity. The PAS is located ~15 Å above the active site, close to the mouth of the gorge.

The presence of tryptophan in the active site of AChE was predicted by spectroscopic and chemical modification studies [20, 59]. The subsequent affinity labeling study of Weise et al. [60] indeed identified W84 as part of the putative ‘anionic’ (choline) binding site. The observation of tyrosine residues within the active-site gorge, adjacent to the catalytic site, is in agreement with the chemical modification studies referred to above [17–19]. The hydroxyl groups of Y121 (half-way up) and Y130 (at the bottom) both point into the gorge.

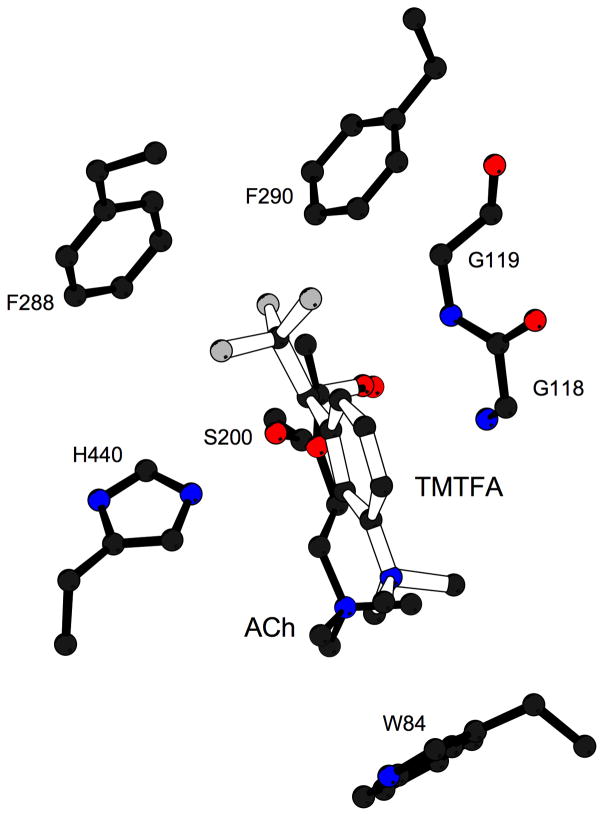

Despite the structural complexity of the gorge, and the flexibility of the natural substrate, ACh [61], it was possible to obtain an extremely good fit of the extended, all-trans conformation of ACh via manual docking [30], using the molecular modeling program O [42]. Specifically, the acyl group was positioned to make a tetrahedral bond with S200-Oγ, while the quaternary group of the choline moiety was placed within van der Waals distance (~3.5Å) of W84 (Fig. 8a). The model suggests that the ‘oxyanion hole’ [54] would be formed by the main chain nitrogens of G118, G119 and A201, interacting with the ACh carbonyl oxygen, and that its ester oxygen could interact with the imidazole of H440. The fact that the amide nitrogen of A201, and not that of S200, contributes to the ‘oxyanion hole’, is consistent with the reversed topology, noted above, of the catalytic triad relative to the serine proteases. G118 and G119 are part of a 10-residue conserved sequence that contains three glycines in a row; this may make the chain flexible enough to allow amide nitrogens from both G118 and G119 to be part of the oxyanion hole. The proposed model was confirmed by the determination of the 3D structure of TcAChE complexed with a transition state analog, m-(N,N,N-trimethylammonio)-2,2,2-trifluoroacetophenone (TMTFA) [62] (Fig. 8b).

Figure 8.

The active site of AChE. (a) Model of ACh bound in the active site of TcAChE; (b) Close-up of the active site of the TMTFA-TcAChE complex [62], showing the experimentally determined TMTFA moiety (open-face lines) together with a superimposed model of ACh docked in the active site (solid lines). Several key residues in the binding pocket are indicated.

The high aromatic content of the walls and base of the active-site gorge (Fig. 4), together with its dimensions, may help explain why biochemical studies revealed a variety of hydrophobic and ‘anionic’ binding sites distinct from, or overlapping with, the active site. For instance, chemical modification by various reagents [17, 63] greatly reduces enzymic activity towards ACh either without affecting, or sometimes actually enhancing, activity towards various neutral esters. This supports the existence of hydrophobic areas distinct from the binding site for ACh.

Two studies utilized photolabeling [64] and affinity labeling [60] to identify peptide sequences, residues 251–264 and 270–278, respectively, as part of the PAS(s) for ACh and other quaternary ligands. These two neighboring peptide sequences on the surface of the protein are both close to the rim of the gorge. The 3D structure of the complex of TcAChE with thioflavin T shows that the ligand is bound at the PAS, sandwiched between the side chains of W279 and F330, midway along and directly occluding the active-site gorge [65]. Thus, the binding of any ligand at this location would block the entry of substrates and the exit of products from the base of the active site. This blockade can have functional significance. In particular, during ACh hydrolysis, an incoming ACh molecule bound at the PAS blocks the exit of a choline molecule generated in the active site, giving rise to substrate inhibition. The complex and varied inhibitory effects of various PAS ligands [2, 11, 22, 26] may be better understood taking into account the reaction kinetics of the substrate [66] and the complex geometry of the gorge. Some ligands may be too bulky to penetrate it, but may still partially block its entrance. Certain elongated bisquaternary compounds, many of which serve as potent inhibitors, may attach at one extremity to the PAS(s), and at the other end to any one of the various aromatic residues lining the walls of the gorge, in certain cases spanning the gorge completely [67]. However, due to the depth of the gorge, shorter bisquaternary inhibitors and homologous oxime reactivators may bind wholly within the gorge.

3.4 Aromatic Guidance

Prior to the determination of the 3D structure of TcAChE, there was much controversy concerning the chemical characteristics of the anionic binding site of AChE [2], as well as of ACh-binding proteins in general [5]. The positive charge of ACh, as well as of numerous inhibitors, led to the designation of the site as ‘anionic’. This was supported by the study of Nolte and coworkers [68], which indicated that the binding site for ACh in Electrophorus AChE contains 6–9 negative charges. The authors suggested that the exceptionally high on-rate observed for quaternary ligands stems from the electrostatic potential produced by the array of negative charges. This is somewhat similar to the ‘electrostatic guidance’ mechanism postulated for superoxide dismutase, in which an array of positive charges guides the negatively charged superoxide radical into the active-site cavity of this rapid enzyme [69].

The above suggestion, however, did not necessarily intend a tight localization of the negative charges in AChE. As Nolte and coworkers [68] noted, the apparent active-site charge may well include a substantial contribution from the net charge on the overall enzyme, a point to which we return in the next section. The 3D structure of TcAChE, in fact, revealed only a small number of negative charges close to the catalytic site, but many aromatic residues are present, both adjacent to the catalytic triad and on the walls of the narrow gorge leading down to its bottom. The prototypic crystallographic study of a binding site for a quaternary ligand, that of the McPC603 myeloma protein, which binds phosphorylcholine selectively, showed that the quaternary moiety of the bound ligand was associated with three aromatic rings [70]. Chemical modification studies of the nicotinic ACh receptor also pointed to involvement of aromatic residues in its ACh-binding site [71], as has since been confirmed [72]. Dougherty & Stauffer [5] presented theoretical considerations, as well as experimental data obtained with model host sites, to support a preferential interaction of quaternary nitrogens with the π electrons of aromatic rings. Indeed, they suggested that aromatic groups interact more strongly with quaternary ammonium ligands than with isosteric uncharged ligands, presumably due to the polarizability of the ion.

It is, however, pertinent to ask how the overall aromatic character of the gorge might contribute to the high rate of ligand binding and, thereby, to the high catalytic activity. First of all, it should be noted that the hydrophobicity of the gorge should result in a low local dieletric constant, which should produce a higher effective local charge than might be predicted from the small number of acidic groups [68]. More important, the aromatic lining may permit utilization of a mechanism involving initial absorption of ACh to low-affinity sites, followed by two-dimensional diffusion to the active site [73]. Rosenberry and Neumann [74] earlier proposed that such a mechanism, involving multiple negatively charged sites, might explain the high on-rates for ligand-binding displayed by AChE. The aromatic lining could function analogously by providing a similar array of low-affinity binding-sites, an ‘aromatic guidance’ mechanism. The ACh, once trapped at the mouth of the gorge, could diffuse rapidly down to the active site. This same mechanism might also provide an efficient means of achieving rapid clearance of the quaternary reaction product, choline.

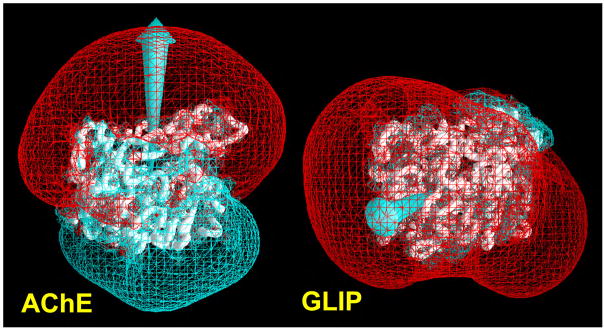

3.5 Electrostatic characteristics of AChE

We now turn to consideration of the electrostatic characteristics of AChE. Fig. 9 places TcAChE alongside GLIP, which hydrolyzes neutral triglycerides [51]. It can be seen that, even though their overall folds are very similar, TcAChE has a very large dipole moment, whereas GLIP has a very small one. Furthermore, the axis of the dipole moment of TcAChE is oriented approximately along the axis of the active-site gorge, whereas that of the lipase bears no obvious correlation with function. Accordingly, we proposed that the dipole moment might serve to attract the positively charged substrate, ACh, into and down the active-site gorge [75]. Shafferman and colleagues, noticing that a motif of seven acidic amino acid residues around the entrance to the gorge made a major contribution to the dipole moment, used site-directed mutagenesis to remove all of them, thus dramatically reducing the asymmetric charge distribution [76]. They found that the mutant enzyme had very similar kinetic parameters for the neutral substrate, 3,3-dimethyl butylacetate, and that the apparent bimolecular rate constant, kapp, for hydrolysis of ATCh was reduced by only ~2–3-fold. They thus questioned the contribution of the dipole moment, or of the negative motif, to catalytic activity. However, in vivo, in the functioning synapse, even the 2–3-fold increase in activity produced by the dimension-breaking role of the electrostatic motif may be crucial in drawing ACh towards the mouth of the gorge, especially at low substrate concentrations. Furthermore, in a subsequent theoretical study, we demonstrated that there is a potential gradient along the whole length of the active-site gorge, which may serve to pull the substrate down the gorge once it has entered its mouth [77], and that this intra-gorge gradient is not very different for the hepta-mutant. The potential within the gorge appears to be affected primarily by D72, midway down, and by E199 and E443 near its base. For example, kapp is decreased 15- to 20-fold with the D72G mutants of both human and TcAChE [78].

Figure 9.

Backbone drawings of TcAChE (left) and GLIP (right) with electrostatic potentials superimposed. Backbones of the proteins are displayed as white “worms”. The isopotential surfaces were generated using the program GRASP [79]. The red surface corresponds to the isopotential contour, −1kT/e, and the blue one to the isopotential contour, +1kT/e, where k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, and e is the electronic charge. Arrows indicate the direction of the dipole in each protein (taken from Ref. [75]).

Another issue that we addressed was the extent to which the potential along the gorge would affect the escape of the positively charged choline against the potential gradient. This study took advantage of an earlier study of Lifson and Jackson [80], who had been investigating an essentially analogous problem–self-diffusion of ions in a polyelectrolyte solution. It was possible to calculate that, assuming that choline can diffuse freely within the gorge, its escape from the gorge should not be rate-limiting [81]. If the electrostatic characteristics of AChE attract ACh into and down the active-site gorge, why is there not a similar effect on metal ions that are present at high concentrations within the synaptic cleft? To date, there are no reports of visualization of metals ions within the gorge in any of the published crystal structures of AChE. When crystals of TcAChE were soaked in a concentrated solution of CsCl, which is very electron dense due to its high atomic number, no traces of cesium ions could be detected within the gorge (G. Koellner, unpublished results). A recent study by Hulme and coworkers [82] made the point that the weak hydration of ACh in aqueous solution favors its interaction with the ACh-binding site of the muscarinic receptor. Likewise, weak hydration of ACh should favor its π-cation interaction with the aromatic residues, principally W279 and Y70, at the top of the gorge, as well as subsequent interactions along the gorge towards the active site, including with the two residues at the bottleneck, Y121 and F330. By the same token, the strong hydration of alkali metal cations should preclude their entering the gorge due to their large diameters in their hydrated forms, 7.2 and 6.6 Å, for Na+ and K+, respectively [83]. Thus the aromatic walls of the gorge provide a surface that may actually facilitate movement of ACh in a non-hydrated form, while excluding metal ions that might otherwise jam the gorge, and crowd into the active site.

3.7 Does AChE show conformational flexibility?

For a protein of over 500 amino acids, it is surprising how remarkably inflexible AChE appears to be. This is evident from detailed comparison of the 3D structures of the various native AChEs [84], as well of complexes of TcAChE, and of other AChEs with a broad repertoire of inhibitors [4]. There are, however, several striking examples of subtle, but significant changes in the structure of AChE, in particular in the active-site pocket. Examples include:

Significant movement of the active-site H440 during the process of aging of the VX/TcAChE conjugate [85] (Fig. 10)

Movement of the acyl pocket in the conjugate of the anti-Alzheimer drug, rivastigmine, with TcAChE [86]

Rearrangement of the active site of TcAChE upon binding of both (+)- and (−)-huperzine A and of (−)-huperzine B [87]

Careful examination of the PAS reveals that W279 can assume several alternative conformations [88, 89].

Figure 10.

Structural kinetics of covalent modification of TcAChE by the nerve agent, VX, as monitored by X-ray crystallography. The active site of TcAChE is depicted with possible H-bonds involving the catalytic triad and the OP moiety (broken lines). (a) Native structure, showing the active site, including the catalytic triad (S200-H440-E327) and the oxyanion hole (-NH of G118, G119, and A201); (b) Pro-aged structure. Phosphonylation triggers a conformational change of H440 that disrupts the H-bond to G327; this may be caused either by steric crowding in the pentavalent phosphorus transition state, or by re-distribution of charge on the H440 imidazole during phosphonylation. It should be noted that E199 and a water molecule apparently stabilize the alternate conformation of H440. Subsequently, the H440 imidazole catalyzes either dealkylation (aging), or spontaneous reactivation; (c) Aged structure. For reaction of AChE with VX and with most phosphonates, aging predominates, and dealkylation results in movement of H440 into the negatively charged pocket formed by E327-Oε, S200-Oγ, and one anionic oxygen of the dealkylated OP.

3.8 Quaternary structure of AChE

AChE is expressed as a repertoire of molecular forms differing in quaternary structure and mode of anchoring, whose pattern varies from tissue to tissue, and may reflect the spatial and temporal demands of individual synapses [8, 90]. This structural polymorphism arises from alternative splicing at the C-terminus, which facilitates association with structural proteins [91]. The T-spliced (AChET) variant is the only form expressed in the brain and muscles of normal adult mammals [92], generating monomers, dimers and tetramers, as well as collagen-tailed [93, 94] and hydrophobic-tailed [95, 96] hetero-oligomers. The functional AChE species at vertebrate cholinergic synapses are formed by four AChET subunits associated with either the collagenous protein ColQ, or with a transmembrane proline-rich membrane anchor (PRiMA) protein. These hetero-oligomeric forms of AChET, and homologous butyrylcholinesterase species [97, 98], are unique structures. In the collagen-tailed species, one, two or three AChET tetramers are attached to the three collagen strands. Each such hetero-tetramer is asymmetric, i.e. two AChE subunits are disulfide-linked via their C-terminal Cys residues, while the corresponding Cys residue of the other two subunits make disulfide bonds with the collagen strand [99, 100]. Nevertheless, the quaternary structure is maintained even when all inter-chain disulfides are reduced [101, 102], and catalytic and structural subunits still associate when the appropriate Cys residues in AChE or ColQ are mutated [103–105]; thus, these disulfides are not required to maintain the quaternary structure.

When ColQ was cloned, first from Torpedo [106], and then from rat [107] and human [108], a proline-rich sequence, close to its N-terminus, was shown to be responsible for attachment of the AChET subunits, and two adjacent conserved cysteines were identified as appropriate candidates for formation of disulfide bridges with the cysteine near the C-terminus of AChET [103]. This sequence was thus named the proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD). Subsequently, the 20 kDa hydrophobic polypeptide from brain was cloned [109], and named PRiMA, since it, too, contains a functional PRAD which organizes AChET subunits into tetramers, and anchors them to the membrane via its transmembrane domain.

AChET monomers assemble into stable tetramers in the presence of either synthetic polyproline [103] or PRAD [104, 110], with no requirement for disulfide bond formation. This interaction requires the highly conserved C-terminal T-sequence of AChET, which forms an amphipathic helix [105], and was named the WAT (tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization) domain, due to the presence of three highly conserved and equally spaced Trp residues. WAT, whether alone, or fused to the C-terminus of heterologous proteins, is sufficient to form tetramers with QN, an N-terminal fragment of ColQ containing PRAD [111]. Thus, assembly of four AChET subunits with one ColQ chain relies on the interactions between the WAT and PRAD sequences. Mutation of the cysteines involved in inter-chain disulfide bond formation provided evidence that the WAT chains are oriented antiparallel to the PRAD [112].

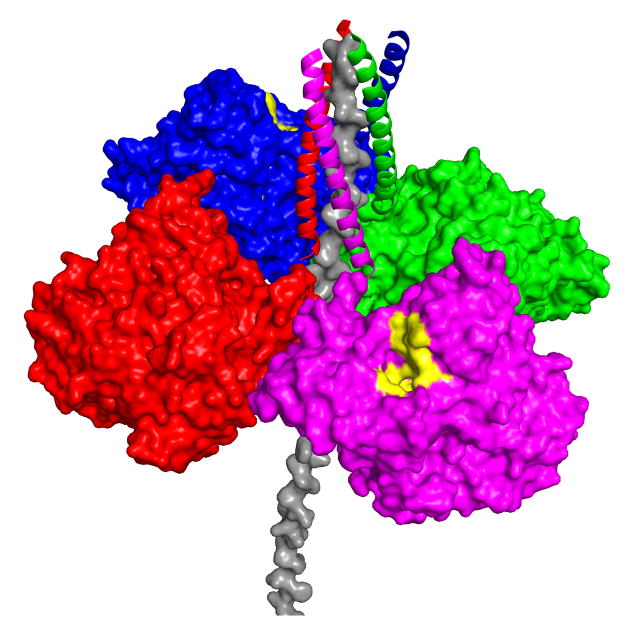

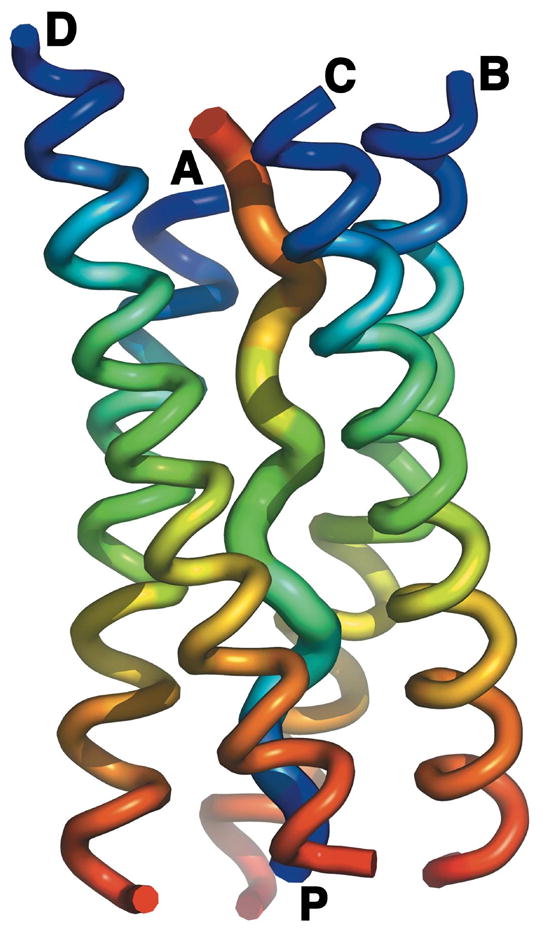

In 2004, we showed that the synthetic WAT and PRAD peptides, without cysteines, form a [WAT]4PRAD complex, which can be crystallized. The crystal structure revealed a novel super-coil fold, in which four WAT peptides are wound antiparallel around the PRAD, in a pseudo 41 symmetry (Fig. 11) [113]. As a result, each WAT chain interacts differently with the PRAD, thus elegantly explaining the asymmetric disulfide bonds observed biochemically for AChET (see Fig 10 [113]). The striking agreement of the structure with the hitherto unexplained biochemical data, permitted us to propose a plausible model for the overall AChET structure (Fig. 12).

Figure 11.

Ribbon diagram of the overall [WAT]4PRAD crystal structure. The structure reveals four WAT helices wrapped around a single PRAD helix. Color coding is from blue at the N-terminus to red at the C-terminus for each chain, showing that the four WATs run parallel to each other, while PRAD runs anti-parallel to all WAT chains. Note that each WAT helix has a different height; as a consequence, each of the four interacts with a different region of the PRAD.

Figure 12.

Model of the physiological ColQ-linked AChET tetramer. The four catalytic subunits surround the ColQ polypeptide, with the WAT sequences displayed as ribbons, and the PRAD as a grey surface model. In this model, access to the active-site gorge (yellow patches) is from the top in two opposing catalytic subunits, while the other two open downwards, in the direction of the basal lamina, as described in [113].

3.9 Structure of apo rhAChE

The crystal structure of rhAChE contains two crystallographically-independent copies (subunits) of AChE (named A and B), which are nearly identical (RMSD of 0.3 Å as calculated by TOP) [114], and are also very similar to the starting model (PDB ID: 1B41), viz., the complex of rhAChE with fasciculin-II (RMSD of 0.5 Å) [33]. The two subunits assemble into the canonical dimer via the four-helix-bundle dimerization module of AChE [30], and are thus related by 2-fold non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) (compare Figs. 5 and 13). Structural alignment of molecule A and the TcAChE structure (PDB ID: 2ACE), which are 59.8 % identical in sequence, yields an RMSD of 0.8 Å.

Figure 13.

Ribbon model of the dimeric structure of apo rhAChE. The view displayed is down the 2-fold NCS axis of the dimer in the ASU. The cysteine residues involved in disulfide bond formation are shown as balls (with green balls representing carbon atoms, blue balls nitrogen atoms, red balls oxygen atoms, and orange balls sulfur atoms).

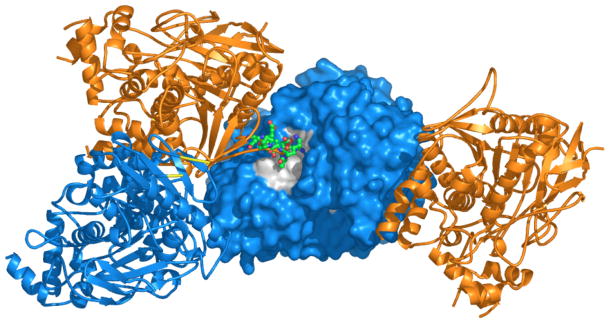

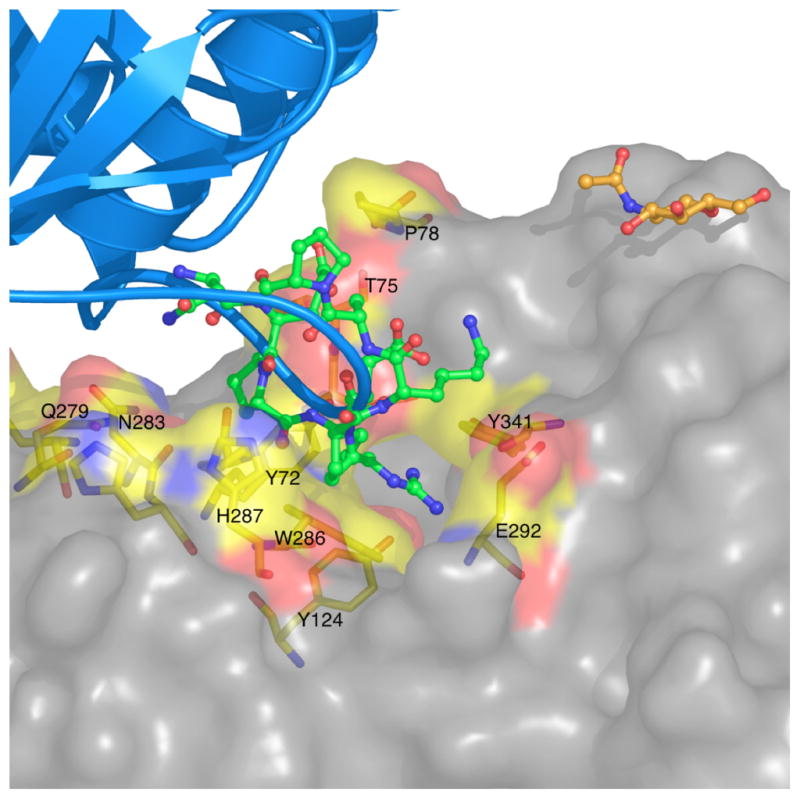

3.10 Packing Interactions in the structure of apo rhAChE

Each rhAChE molecule in the asymmetric unit makes unique interactions with symmetry-related dimers (Fig. 14). In general, this leads to systematic variations in surface regions that are involved in intrinsically different packing contacts. For instance, the loop formed by residues 483–491, which is highly flexible in virtually all AChE structures, i.e., not being seen in the electron density maps, is well defined in one subunit, but disordered in the other subunit of the dimer in the ASU. Interestingly, this loop interacts with the PAS of an NCS-related subunit from a symmetry-related dimer, such that active-site access is blocked in half of the AChE molecules in the crystal (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

Packing of two rhAChE dimers. Each dimer consists of two AChE catalytic subunits (A in orange and B in blue), which are related by the 2-fold NCS axis shown in Fig. 13. A surface loop (residues 489–499, green balls-and-sticks) of subunit A interacts with the PAS of subunit B from a symmetry-related dimer. Since the blue subunits have no adjacent PAS to interact with, their corresponding loops are disordered, as is the case in many other AChE structures.

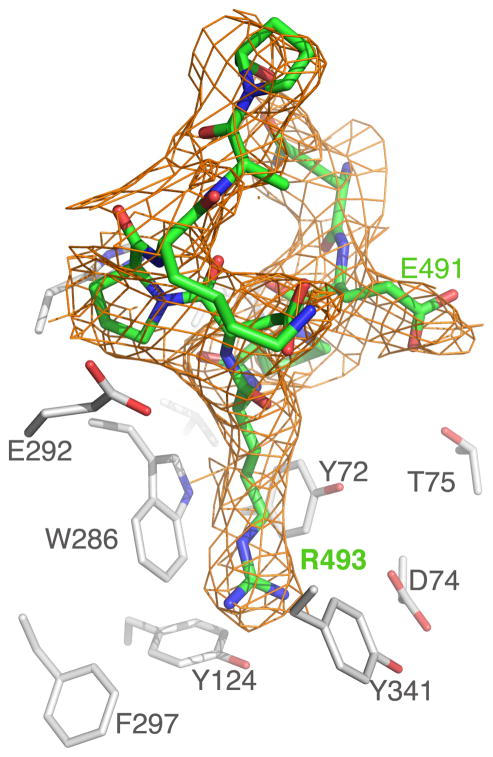

The interactions are rather specific; in particular, R493 penetrates into the active-site gorge, and stacks against the PAS residue, W286 (Figs. 15 & 16). A similar interaction with W286, but by a Met residue, is made by the three-fingered snake toxin, fasciculin, which is a potent AChE inhibitor, with a Ki in the picomolar range [33, 34]. Fig. 15 shows other residues within the PAS that may participate in the interaction with this loop. In particular, Y124, Y72, Y341 and D74 are all near R493. Ironically, this apo-structure of rhAChE reveals, for the first time, specific interactions that the PAS makes with a single linear peptide sequence, since the interactions seen are made primarily with the 489–499 loop, in contrast to those made with the three-fingered structure of snake venom toxins, where there are interactions between several non-contiguous sequences in the toxin and AChE. It would thus be of interest to test peptides with sequences similar to that of the 489–499 loop for their capacity to inhibit hAChE, and, thus, for their potential pharmacological value.

Figure 15.

The PAS of rhAChE interacts with the positively charged loop on the adjacent monomer. The adjacent monomer is rendered in grey surface format. Residues in the vicinity (<4.5 Å) of the binding site for the basic loop are highlighted on the surface in stick representation (with carbon atoms color-coded in yellow, oxygen atoms in red, and nitrogens atoms in blue). The refined N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) in the proximity of the interface is also shown.

Figure 16.

Electron density around the active-site ‘blocking’ loop in the structure of apo rhAChE. The loop region (residues 490–498) is shown as green sticks with the refined 2Fo-Fc electron density around it contoured at 1.5 σ. Side-chains in the ‘blocked’ subunit within 5.5 Å of the loop are displayed as grey sticks. Key residues are marked for orientation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Nalvyco Foundation, the Bruce Rosen Foundation, the Jean and Jula Goldwurm Memorial Foundation, the Divadol Foundation, the Neuman Foundation, the Benoziyo Center for Neuroscience, the NIH CounterACT Program (Grant 1U54NS058183 to JLS), the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (Grant HDTRA 1-07-C-0024 to JLS), the National Institutes of Health (Grant NS-16577 to TLR), and the Muscular Dystrophy Association of America (to TLR). JLS is the Morton and Gladys Pickman Professor of Structural Biology.

Abbreviations

- rhAChE

recombinant human AChE

- TcAChE

Torpedo californica AChE

- ES

esteratic site

- AS

anionic substrate binding site

- ACS

aromatic cation binding site

- PAS

peripheral anionic binding site

- GLIP

Geotrichum candidum lipase

- WAT domain

tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization domain

- AChET

AChE spliced variant with a C-terminal T sequence

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- GPI

glycophosphatidylinositol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barnard EA. Neuromuscular transmission - enzymatic destruction of acetylcholine. In: Hubbard JI, editor. The Peripheral Nervous System. Plenum; New York: 1974. pp. 201–224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn DM. Acetylcholinesterase: enzyme structure, reaction dynamics, and virtual transition states. Chem Rev. 1987;87:955–975. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor P. Anticholinesterase agents. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, Ruddon RW, Gilman AG, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 9. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1996. pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenblatt HM, Dvir H, Silman I, Sussman JL. Acetylcholinesterase: a multifaceted target for structure-based drug design of anticholinesterase agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;20:369–384. doi: 10.1385/JMN:20:3:369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dougherty DA, Stauffer DA. Acetylcholine binding by a synthetic receptor: implications for biological recognition. Science. 1990;250:1558–1560. doi: 10.1126/science.2274786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bon S, Vigny M, Massoulié J. Asymmetric and globular forms of acetylcholinesterase in mammals and birds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:2546–2550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.6.2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nachmansohn D, Neumann E. Chemical and Molecular Basis of Nerve Activity. 2. Academic Press; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silman I, Futerman AH. Modes of attachment of acetylcholinesterase to the surface membrane. Eur J Biochem. 1987;170:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman HA, Leonard K. Ligand exclusion on acetylcholinesterase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10640–10649. doi: 10.1021/bi00499a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nachmansohn D, Wilson IB. The enzymic hydrolysis and synthesis of acetylcholine. Adv Enzymol. 1951;12:259–339. doi: 10.1002/9780470122570.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberry TL. Acetylcholinesterase. Adv Enzymol. 1975;43:103–218. doi: 10.1002/9780470122884.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froede HC, Wilson IB. Acetylcholinesterase. In: Boyer PD, editor. The Enzymes. 3. Academic Press; New York: 1971. pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacPhee-Quigley K, Taylor P, Taylor S. Primary structure of the catalytic subunits from two molecular forms of acetylcholinesterase. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:12185–12189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson IB, Bergmann F. Acetylcholinesterase VIII. Dissociation constants of the active groups. J Biol Chem. 1950;186:683–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson IB, Quan C. Acetylcholinesterase: Studies on molecular complementariness. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1958;73:131–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(58)90248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mooser G, Sigman DS. Ligand binding properties of acetylcholinesterase determined with fluorescent probes. Biochemistry. 1974;13:2299–2307. doi: 10.1021/bi00708a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs S, Gurari D, Silman I. Chemical modification of Electric Eel acetylcholinesterase by tetranitromethane. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974;165:90–97. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blumberg S, Silman I. Inactivation of electric eel acetylcholinesterase by acylation with N-hydroxysuccinimide esters of amino acid derivatives. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1125–1130. doi: 10.1021/bi00599a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page JD, Wilson IB. Acetylcholinesterase: Inhibition by tetranitromethane and arsenite. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:1475–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goeldner MP, Hirth CG. Specific photoaffinity labeling induced by energy transfer: Application to irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:6439–6442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Changeux JP. Responses of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo marmorata to salts and curarizing drugs. Mol Pharmacol. 1966;2:369–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergmann F, Wilson IB, Nachmansohn D. The inhibitory effect of stilbamidine, curare and related compounds and its relationship to the active groups of acetylcholine esterase. Action of stilbamidine upon nerve impulse conduction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1950;6:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(50)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor P, Lappi S. Interaction of fluorescence probes with acetylcholinesterase. The site and specificity of propidium binding. Biochemistry. 1975;14:1989–1997. doi: 10.1021/bi00680a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiner E, Aldridge N, Simeon V, Radic Z, Taylor P. Mechanism of substrate inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. In: Massoulié J, Bacou F, Barnard E, Chatonnet A, Doctor BP, Quinn DM, editors. Cholinesterases: Structure, Function, Mechanism, Genetics and Cell Biology. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1991. pp. 227–228. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szegletes T, Mallender WD, Thomas PJ, Rosenberry TL. Substrate binding to the peripheral site of acetylcholinesterase initiates enzymatic catalysis. Substrate inhibition arises as a secondary effect. Biochemistry. 1999;38:122–133. doi: 10.1021/bi9813577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson JL, Cusack B, Davies MP, Fauq A, Rosenberry TL. Unmasking tandem site interaction in human acetylcholinesterase. Substrate activation with a cationic acetanilide substrate. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5438–5452. doi: 10.1021/bi027065u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leuzinger W, Baker AL. Acetylcholinesterase, I. Large-scale purification, homogeneity and amino acid analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;57:446–451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.2.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chothia C, Leuzinger W. Acetylcholinesterase: the structure of crystals of a globular form from the electric eel. J Mol Biol. 1975;97:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schrag J, Schmid MF, Morgan DG, Phillips GN, Jr, Chiu W, Tang L. Crystallization and preliminary X-Ray diffraction analysis of 11 S acetylcholinesterase. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:9795–9800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sussman JL, Harel M, Frolow F, Oefner C, Goldman A, Toker L, Silman I. Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: a prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science. 1991;253:872–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1678899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourne Y, Taylor P, Radic Z, Marchot P. Structural insights into ligand interactions at the acetylcholinesterase peripheral anionic site. EMBO J. 2003;22:1–12. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harel M, Kryger G, Rosenberry TL, Mallender WD, Lewis T, Fletcher RJ, Guss JM, Silman I, Sussman JL. Three-dimensional structures of Drosophila melanogaster acetylcholinesterase and of its complexes with two potent inhibitors. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1063–1072. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.6.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kryger G, Harel M, Giles K, Toker L, Velan B, Lazar A, Kronman C, Barak D, Ariel N, Shafferman A, Silman I, Sussman JL. Structures of recombinant native and E202Q mutant human acetylcholinesterase complexed with the snake-venom toxin fasciculin-II. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:1385–1394. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900010659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harel M, Kleywegt GJ, Ravelli RBG, Silman I, Sussman JL. Crystal structure of an acetylcholinesterase-fasciculin complex: interaction of a three-fingered toxin from snake venom with its target. Structure. 1995;3:1355–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourne Y, Taylor P, Marchot P. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition by fasciculin: crystal structure of the complex. Cell. 1995;83:503–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Futerman AH, Low MG, Silman I. A Hydrophobic dimer of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica is solubilized by phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. Neurosci Lett. 1983;40:85–89. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sussman JL, Harel M, Frolow F, Varon L, Toker L, Futerman AH, Silman I. Purification and crystallization of a dimeric form of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica subsequent to solubilization with phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:821–823. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallender WD, Szegletes T, Rosenberry TL. Organophosphorylation of acetylcholinesterase in the presence of peripheral site ligands. distinct effects of propidium and fasciculin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8491–8499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for the building of protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. In: Moras D, Podjarny AD, Thierry JC, editors. Crystallographic Computing. Oxford Univ. Press; Oxford: 1991. pp. 413–432. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murshudov G, Vagin A, Dodson E. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss D, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levitt M, Chothia C. Structural patterns in globular proteins. Nature. 1976;261:552–558. doi: 10.1038/261552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ollis DL, Cheah E, Cygler M, Dijkstra B, Frolow F, Franken SM, Harel M, Remington SJ, Silman I, Schrag J, Sussman JL, Verschueren KHG, Goldman A. The α/β hydrolase fold. Protein Eng. 1992;5:197–211. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacPhee-Quigley K, Vedvick TS, Taylor P, Taylor SS. Profile of the disulfide bonds in acetylcholinesterase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13565–13570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pathak D, Ngai KL, Ollis D. X-ray crystallographic structure of dienelactone hydrolase at 2.8Å. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:435–445. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90587-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liao D, Remington SJ. Structure of wheat serine carboxypeptidase II at 3.5-Å resolution. a new class of serine proteinase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6528–6531. doi: 10.2210/pdb2sc2/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schrag JD, Li Y, Wu S, Cygler M. Ser-His-Glu triad forms the catalytic site of the lipase from Geotrichum candidum. Nature. 1991;351:761–764. doi: 10.1038/351761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Franken SM, Rozeboom HJ, Kalk KH, Dijkstra BW. Crystal structure of haloalkane dehalogenase: an enzyme to detoxify halogenated alkanes. EMBO J. 1991;10:1297–1302. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cousin X, Hotelier T, Giles K, Lievin P, Toutant JP, Chatonnet A. The alpha/beta fold family of proteins database and the cholinesterase gene server ESTHER. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:143–146. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steitz TA, Shulman RG. Crystallographic and NMR studies of the serine proteases. Ann Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1982;11:419–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.11.060182.002223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sussman JL, Harel M, Frolow F, Oefner C, Toker L, Silman I. Structural studies on acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica. In: Massoulié J, Bacou F, Barnard E, Chatonnet A, Doctor BP, Quinn DM, editors. Cholinesterases: Structure, Function, Mechanism, Genetics and Cell Biology. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1991. pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winkler FK, D’Arcy A, Hunziker W. Structure of human pancreatic lipase. Nature. 1990;343:771–774. doi: 10.1038/343771a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richardson JS. The anatomy and taxonomy of protein structure. Adv Protein Chem. 1981;34:167–339. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maulet Y, Camp S, Gibney G, Rachinsky TL, Ekström TJ, Taylor P. Single gene encodes glycophospholipid-anchored and asymmetric acetylcholinesterase forms: alternative coding exons contain inverted repeat sequences. Neuron. 1990;4:289–301. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90103-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shinitzky M, Dudai Y, Silman I. Spectral evidence for the presence of tryptophan in the binding site of acetylcholinesterase. FEBS Lett. 1973;30:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80633-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weise C, Kreienkamp HJ, Raba R, Pedak A, Aaviksaar A, Hucho F. Anionic subsites of the acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: affinity labelling with the cationic reagent N,N-dimethyl-2-phenyl-aziridinium. EMBO J. 1990;9:3885–3888. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chothia C, Pauling P. Conformations of acetylcholine. Nature. 1968;219:1156–1157. doi: 10.1038/2191156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harel M, Quinn DM, Nair HK, Silman I, Sussman JL. The X-ray structure of a transition state analog complex reveals the molecular origins of the catalytic power and substrate specificity of acetylcholinesterase. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2340–2346. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Purdie JE, McIvor RA. Modification of the esteratic activity of acetylcholinesterase by alkylation with 1,1-dimethyl-2-phenylaziridinium ion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;128:590–593. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amitai G, Taylor P. Characterization of peripheral anionic site peptides of AChE by photoaffinity labeling with monoazidopropidium (MAP) In: Massoulié J, Bacou F, Barnard E, Chatonnet A, Doctor BP, Quinn DM, editors. Cholinesterases: Structure, Function, Mechanism, Genetics and Cell Biology. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1991. p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harel M, Sonoda LK, Silman I, Sussman JL, Rosenberry TL. Crystal structure of thioflavin T bound to the peripheral site of Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase reveals how thioflavin T acts as a sensitive fluorescent reporter of ligand binding to the acylation site. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7856–7861. doi: 10.1021/ja7109822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosenberry TL, Cusack B, Sonoda LK, Dekat SE, Johnson JL. Molecular basis of inhibition of substrate hydrolysis by a ligand bound to the peripheral site of acetylcholinesterase. Chem Biol Interactions. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.05.009. (this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harel M, Schalk I, Ehret-Sabatier L, Bouet F, Goeldner M, Hirth C, Axelsen P, Silman I, Sussman JL. Quaternary ligand binding to aromatic residues in the active-site gorge of acetylcholinesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9031–9035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nolte HJ, Rosenberry TL, Neumann E. Effective charge on acetylcholinesterase active sites determined from the ionic strength dependence of association rate constants with cationic ligands. Biochemistry. 1980;19:3705–3711. doi: 10.1021/bi00557a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tainer JA, Getzoff ED, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Structure and mechanism of copper, zinc superoxide dismutase. Nature. 1983;306:284–287. doi: 10.1038/306284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davies DR, Metzger H. Structural basis of antibody function. Ann Rev Immunol. 1983;1:87–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dennis M, Giraudat J, Kotzyba-Hibert F, Goeldner M, Hirth C, Chang JY, Lazure C, Chrétien M, Changeux JP. Amino acids of the Torpedo marmorata acetylcholine receptor α subunit labeled by a photoaffinity ligand for the acetylcholine binding site. Biochemistry. 1988;27:2346–2357. doi: 10.1021/bi00407a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Klaassen RV, Schuurmans M, van der Oost J, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411:269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adam G, Delbruck M. In: Structural Chemistry and Molecular Biology. Rich A, Davidson N, editors. Freeman; San Francisco: 1968. pp. 198–215. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosenberry TL, Neumann E. Interaction of ligands with acetylcholinesterase. use of temperature-jump relaxation kinetics in the binding of specific fluorescent ligands. Biochemistry. 1977;16:3870–3877. doi: 10.1021/bi00636a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ripoll DR, Faerman CH, Axelsen PH, Silman I, Sussman JL. An electrostatic mechanism for substrate guidance down the aromatic gorge of acetylcholinesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5128–5132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shafferman A, Ordentlich A, Barak D, Kronman C, Ber R, Bino T, Ariel N, Osman R, Velan B. Electrostatic attraction by surface charge does not contribute to the catalytic efficiency of acetylcholinesterase. EMBO J. 1994;13:3448–3455. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Felder CE, Botti SA, Lifson S, Silman I, Sussman JL. External and internal electrostatic potentials of cholinesterase models. J Molec Graphics & Modelling. 1997;15:318–327. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(98)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mallender WD, Szegletes T, Rosenberry TL. Acetylthiocholine binds to Asp74 at the peripheral site of human acetylcholinesterase as the first step in the catalytic pathway. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7753–7763. doi: 10.1021/bi000210o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nicholls A, Sharp K, Honig B. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins. 1991;11:281–296. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lifson S, Jackson JL. On the self-diffusion of ions in a polyelectrolyte solution. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1962;36:2410–2414. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Botti SA, Felder C, Lifson S, Sussman JL, Silman I. A modular treatment of molecular traffic through the active site of cholinesterases. Biophys J. 1999;77:2430–2450. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hulme EC, Soper AK, McLain SE, Finney JL. The hydration of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in aqueous solution. Biophys J. 2006;91:2371–2380. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.089185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chai L, Goldberg R, Kampf N, Klein J. Selective adsorption of poly(ethylene oxide) onto a charged surface mediated by alkali metal ions. Langmuir. 2008;24:1570–1576. doi: 10.1021/la702514j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zeev-Ben-Mordehai T, Silman I, Sussman JL. Acetylcholinesterase in motion: Visualizing conformational changes in crystal structures by a morphing procedure. Biopolymers. 2003;68:395–406. doi: 10.1002/bip.10287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Millard CB, Koellner G, Ordentlich A, Shafferman A, Silman I, Sussman JL. Reaction products of acetylcholinesterase and VX reveal a mobile histidine in the catalytic triad. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9883–9884. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bar-On P, Millard CB, Harel M, Dvir H, Enz A, Sussman JL, Silman I. Kinetic and structural studies on the interaction of cholinesterases with the anti-Alzheimer drug rivastigmine. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3555–3564. doi: 10.1021/bi020016x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dvir H, Jiang HL, Wong DM, Harel M, Chetrit M, He XC, Tang XC, Silman I, Bai DL, Sussman JL. X-ray structures of Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase complexed with (+)-Huperzine A and (−)-Huperzine B: Structural evidence for an active site rearrangement. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10810–10818. doi: 10.1021/bi020151+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xu Y, Colletier JP, Weik M, Jiang H, Moult J, Silman I, Sussman JL. Flexibility of aromatic residues in the active-site gorge of acetylcholinesterase: X-ray versus molecular dynamics. Biophys J. 2008;95:2500–2511. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu Y, Colletier JP, Jiang H, Silman I, Sussman JL, Weik M. Induced-fit or pre-existing equilibrium dynamics? Lessons from protein crystallography and MD simulations on acetylcholinesterase. Protein Sci. 2008;17:601–605. doi: 10.1110/ps.083453808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Massoulié J, Pezzementi L, Bon S, Krejci E, Vallette FM. Molecular and cellular biology of cholinesterases. Prog Neurobiol. 1993;14:31–91. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Massoulié J. The origin of the molecular diversity and functional anchoring of cholinesterases. Neurosignals. 2002;11:130–143. doi: 10.1159/000065054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Legay C, Huchet M, Massoulié J, Changeux JP. Developmental regulation of acetylcholinesterase transcripts in the mouse diaphragm: alternative splicing and focalization. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:1803–1809. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dudai Y, Herzberg M, Silman I. Molecular structures of acetylcholinesterase from electric organ tissue of the electric eel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:2473–2476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.9.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rieger F, Bon S, Massoulié J. Observation par microscopie électronique des formes allongées et globulaires de l’acétylcholinestérase de gymnote (Electrophorus electricus) Eur J Biochem. 1973;34:539–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gennari K, Brunner J, Brodbeck U. Tetrameric detergent-soluble acetylcholinesterase from human caudate nucleus: subunit composition and number of active sites. J Neurochem. 1987;49:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Inestrosa NC, Roberts WL, Marshall TL, Rosenberry TL. Acetylcholinesterase from bovine caudate nucleus is attached to membranes by a novel subunit distinct from those of acetylcholinesterases in other tissues. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4441–4444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vigny M, Gisiger V, Massoulié J. “Nonspecific” cholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase in rat tissues: molecular forms, structural and catalytic properties, and significance of the two enzyme systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2588–2592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Silman I, di Giamberardino L, Lyles L, Couraud JY, Barnard EA. Parallel regulation of acetylcholinesterase and pseudocholinesterase in normal, denervated and dystrophic chicken skeletal muscle. Nature. 1979;280:160–162. doi: 10.1038/280160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McCann WF, Rosenberry TL. Identification of discrete disulfide-linked oligomers which distinguish 18 S from 14 S acetylcholinesterase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;183:347–352. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Anglister L, Silman I. Molecular structure of elongated forms of electric eel acetylcholinesterase. J Mol Biol. 1978;125:293–311. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bon S, Massoulié J. Molecular forms of Electrophorus acetylcholinesterase catalytic subunits: fragmentation, intra- and inter-subunit disulfide bonds. FEBS Lett. 1976;71:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Anglister L, Roth E, Silman I. Quaternary structure of electric eel acetylcholinesterase. In: Brzin M, Sket D, Bachelard H, editors. Synaptic Constituents in Health and Disease. Pergamon; New York: 1980. pp. 533–540. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bon S, Coussen F, Massoulié J. Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. II. The polyproline attachment domain of the collagen tail. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3016–3021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kronman C, Chitlaru T, Elhanany E, Velan B, Shafferman A. Hierarchy of post-translational modifications involved in the circulatory longevity of glycoproteins. Demonstration of concerted contributions of glycan sialylation and subunit assembly to the pharmacokinetic behavior of bovine acetylcholinesterase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29488–29502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bon S, Ayon A, Leroy J, Massoulié J. Trimerization domain of the collagen tail of acetylcholinesterase. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:523–535. doi: 10.1023/a:1022821306722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Krejci E, Coussen F, Duval N, Chatel JM, Legay C, Puype M, Vandekerckhove J, Cartaud J, Bon S, Massoulié J. Primary structure of a collagenic tail peptide of Torpedo acetylcholinesterase: co-expression with catalytic subunit induces the production of collagen-tailed forms in transfected cells. EMBO J. 1991;10:1285–1293. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Krejci E, Thomine S, Boschetti N, Legay C, Sketelj J, Massoulié J. The mammalian gene of acetylcholinesterase-associated collagen. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22840–22847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ohno K, Brengman J, Tsujino A, Engel AG. Human endplate acetylcholinesterase deficiency caused by mutations in the collagen-like tail subunit (ColQ) of the asymmetric enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9654–9659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Perrier AL, Massoulié J, Krejci E. PRiMA: the membrane anchor of acetylcholinesterase in the brain. Neuron. 2002;33:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Giles K, Ben-Yohanan R, Velan B, Shafferman A, Sussman JL, Silman I. Assembly of acetylcholinesterase subunits in vitro. In: Doctor BP, Quinn DM, Rotundo RL, Taylor P, editors. Structure and Function of Cholinesterases and Related Proteins. Plenum; New York: 1998. pp. 442–443. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Simon S, Krejci E, Massoulié J. A four-to-one association between peptide motifs: four C-terminal domains from cholinesterase assemble with one proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD) in the secretory pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:6178–6187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bon S, Dufourcq J, Leroy J, Cornut I, Massoulié J. The C-terminal t peptide of acetylcholinesterase forms an alpha helix that supports homomeric and heteromeric interactions. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:33–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dvir H, Harel M, Bon S, Liu WQ, Vidal M, Garbay C, Sussman JL, Massoulié J, Silman I. The synaptic acetylcholinesterase tetramer assembles around a polyproline-II helix. EMBO J. 2004;23:4394–4405. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lu G. TOP: A new method for protein structure comparisons and similarity searches. J Appl Cryst. 2000;33:176–183. [Google Scholar]