Abstract

DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs) are among the most cytotoxic types of DNA damage, and thus ICL-inducing agents such as cyclophosphamide, melphalan, cisplatin, psoralen and mitomycin C have been used clinically as anti-cancer drugs for decades. ICLs can also be formed endogenously as a consequence of cellular metabolic processes. ICL-inducing agents continue to be among the most effective chemotherapeutic treatments for many cancers; however, treatment with these agents can lead to secondary malignancies, in part due to mutagenic processing of the DNA lesions. The mechanisms of ICL repair have been characterized more thoroughly in bacteria and yeast than in mammalian cells. Thus, a better understanding the molecular mechanisms of ICL processing offers the potential to improve the efficacy of these drugs in cancer therapy. In mammalian cells it is thought that ICLs are repaired by the coordination of proteins from several pathways, including nucleotide excision repair (NER), base excision repair (BER), mismatch repair (MMR), homologous recombination (HR), translesion synthesis (TLS), and proteins involved in Fanconi anemia (FA). In this review, we focus on the potential functions of NER, MMR, and HR proteins in the repair of and response to ICLs in human cells and in mice. We will also discuss a unique approach, using psoralen covalently linked to triplex-forming oligonucleotides to direct ICLs to specific sites in the mammalian genome.

Keywords: Psoralen, DNA interstrand crosslink, triplex, DNA repair

INTRODUCTION

DNA ICLs, such as those formed by many anticancer drugs, present formidable blocks to DNA metabolic processes and must be repaired for cell survival. For this reason, many ICL-inducing agents are clinically effective as chemotherapeutic agents. It has been estimated that as few as 40 ICLs in a mammalian genome can kill a repair-deficient cell (Lawley and Phillips 1996). However, resistance to ICL-inducing agents, due in part to efficient DNA repair, can result in recurrent malignancies, which are refractory to treatment (Boulikas and Vougiouka 2003; Sampath and Plunkett 2007). Moreover, treatment with ICL-inducing agents can increase the risk of secondary malignancies [e.g. psoralen plus UVA irradiation (PUVA) therapy (Wang et al. 2001), likely due to mutagenic processing of the lesions in normal cells. ICL-inducing agents are also found naturally in the environment (e.g. furocoumarins found in plants, which contain psoralens and angelicins. Angelicins do not form ICLs). For example, malondialdehyde generated from lipid peroxidation can generate ICLs, and nitric oxide gas, which forms nitric acid when hydrated, can result in the formation of ICLs. While much has been learned about the repair of psoralen ICLs in bacteria and yeast (Cole 1973a; Dronkert and Kanaar 2001; Magana-Schwencke et al. 1982; Van Houten et al. 1986), which generally process ICLs by using a combination of NER, HR, and TLS, their repair is poorly understood in mammalian cells. Therefore, efforts to better define the cellular responses to and repair of ICL-inducing lesions in mammalian cells are warranted and are currently ongoing in many laboratories.

In this review we will focus on psoralen ICLs; psoralen is a photoactivatable DNA crosslinking agent that is used clinically for the treatment of hyperproliferative skin disorders, including psoriasis and skin cancer (Momtaz and Fitzpatrick 1998). Psoralens are planar triheterocyclic compounds containing furan and pyrone rings. Psoralen can intercalate in DNA, and following exposure to ultraviolet (UVA) irradiation can form a monoadduct with an appropriately positioned pyrimidine base on either the furan side or the pyrone side. Upon absorption of a second photon (at 365 nm), a furan-sided monoadduct can be converted into an ICL by covalent linkage of the pyrone ring with a pyrimidine base in the complementary strand (Cimino et al. 1985).

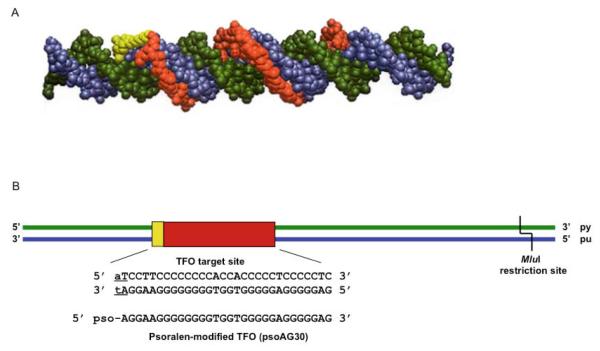

Psoralen forms covalent ICLs with thymines preferentially at 5′-TpA sequences. While TA sequences are the preferred crosslinking sites of psoralen, it binds DNA in a non-specific fashion. To overcome this limitation in targeting specificity, triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) have been used to direct psoralen ICLs to specific sites. TFOs are single-stranded DNA molecules that bind sequence-specifically in the major groove of duplex DNA via Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding [reviewed in (Vasquez and Glazer 2002)]. Using triplex technology, chromosomal genes have been targeted for modification in mammalian cells and in animals (Majumdar et al. 1998; Oh and Hanawalt 1999; Vasquez et al. 2000; Vasquez et al. 1999). Psoralen-conjugated TFOs can bind their target duplex sequences and induce site-specific photoadducts when exposed to UVA (Perkins et al. 1999; Vasquez et al. 1996).

PUVA treatment is a widely used and effective therapy for disorders of epidermal hyperproliferation, but its potential is limited without the ability to target ICLs to specific genes or cell types. As mentioned above, PUVA therapy is beneficial, yet it is often accompanied by an increased risk of developing skin cancer [reviewed in (Momtaz and Fitzpatrick 1998; Reddy and Vasquez 2005; Wang et al. 2001)]. This may be due in part, to the random mutations induced in the DNA during error-generating repair of the ICLs; however, it is possible to direct psoralen ICLs to specific sites via TFO targeting, which should reduce the off-target effects of PUVA therapy. It has been demonstrated that psoralen-modified TFOs can direct spatially localized ICLs by two-photon excitation using 765 nm light rather than 365 nm (Oh et al. 2001). This approach may provide clinical benefit because longer wavelengths of light penetrate deeper into tissue and are less cytotoxic. Thus, triplex technology has potential as a targeted therapeutic strategy to treat disorders of epidermal hyperproliferation (e.g. psoriasis and cancer). Further characterization of ICL processing in mammalian cells may eventually lead to improved therapies for these patients.

MECHANISMS OF DNA REPAIR

In humans, DNA damage is generally repaired by one or more of five mechanism; direct repair, BER, NER, MMR, and HR [reviewed in (Berti and McCann 2006; Gillet and Scharer 2006; Ishino et al. 2006; Iyer et al. 2006; Mishina et al. 2006)]. However, it is clear that there are interactions among various components of these diverse pathways, and that efficient recognition and removal of DNA damage often involves interactions of components from multiple pathways. The interaction among proteins from various defined repair pathways may be particularly important in processing certain types of complex DNA damage, which cannot be efficiently or directly processed via any single mechanism. A fundamental aspect of most DNA repair mechanisms is the redundancy of the genetic information. Thus, when a single strand of the duplex is damaged, the other strand may be available as a template for repair synthesis. However, when an ICL or a DNA double-strand break (DSB) occurs in the DNA, the complementary strand is no longer available to serve as a template for repair. Under these conditions, HR can provide an alternate repair pathway that uses the sister chromatid or the homologue as the donor sequence. DSBs can also be repaired by non-homologous end-joining or single-strand annealing, which can result in deletions between homologous sequences. Repair of ICLs in particular is thought to be accomplished by proteins from several repair mechanisms; NER, MMR, BER, HR, and TLS. The Fanconi anemia (FA) proteins are also implicated in the response to and/or repair of ICLs, and the pathway choice for ICL repair is cellcycle dependent (see Figure 1 for a working model of ICL processing in mammalian cells). The potential roles of BER, FA proteins, and TLS polymerases can be found in other articles in this special issue and will not be discussed here. The focus of this review is on the functions of NER, MMR, and HR proteins in the cellular signaling and processing of targeted ICL-induced DNA damage.

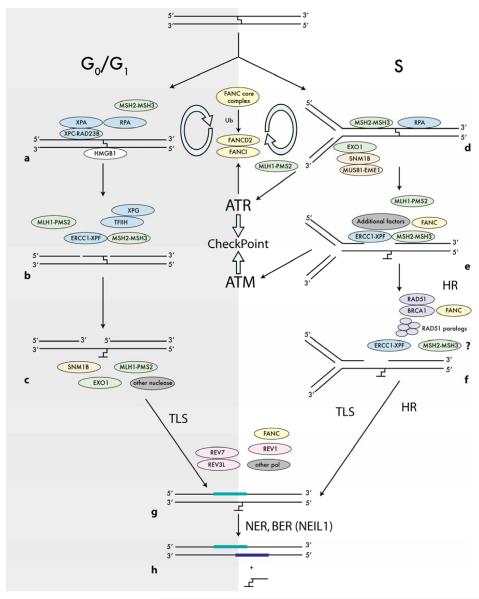

Figure 1. Model of ICL repair in mammalian cells.

The schematic depicts two modes of ICL processing in mammalian cells. On the left (“G0/G1”) is a potential pathway of ICL repair in nonreplicating cells; and on the right (“S”) is a potential pathway of ICL repair in replicating cells

Nucleotide excision repair

NER is perhaps the most versatile of all repair systems and is highly conserved. Defects in NER can lead to devastating consequences as demonstrated by several clinical disorders (de Boer and Hoeijmakers 2000; Kleijer et al. 2008; Kraemer et al. 2007; Lehmann 2003; Leibeling et al. 2006). A major consequence of defects in NER is an enhanced predisposition to UV-induced skin cancer. The human NER machinery consists of >25 proteins, and in vitro reconstitution of NER has implicated six core factors that are required for processing DNA lesions (Aboussekhra et al. 1995; Araki et al. 2000; Guzder et al. 1996; He and Ingles 1997; Mu et al. 1995). These essential proteins include xeroderma pigmentosum A (XPA), replication protein A (RPA), XPC-RAD23B, transcription factor IIH (TFIIH), which contains the XPB and XPD helicases, XPG, and XPF in a complex with the excision repair cross-complementing (ERCC1) protein. The damaged base is removed by incision of the phosphodiester bonds on either side of the lesion by structure-specific endonucleases resulting in the release of an oligonucleotide containing the damage followed by repair synthesis and ligation. In eukaryotes the typical repair patch size is 24-32 nucleotides, formed by incisions of 2-8 bases on the 3′ side of the lesion by XPG, and 15-24 bases on the 5′ side by ERCC1-XPF. See the review by R.D. Wood in this issue for a model of the process.

Mismatch repair

Cells deficient in MMR are hypermutable and predisposed to tumorigenesis as evidenced by hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer in humans (Fishel et al. 1993; Pavlovic-Calic et al. 2007). MMR is responsible for removal of base-pairing errors such as mismatches and insertion-deletion loops caused by spontaneous and induced base deamination, oxidation, methylation, reactive oxygen species, recombination intermediates, and replication errors. In this capacity, MMR proteins interact with components of other repair pathways including NER to prevent spontaneous mutation and microsatellite instability [reviewed in (Fedier and Fink 2004)]. The damage recognition complexes, MSH2-MSH6 (MutSα) or MSH2-MSH3 (MutSβ), initiate MMR in eukaryotes. Following the recognition step, a heterodimer of MLH1 with PMS2 (MutLα) binds to the MSH complex and to a single-strand nick in the DNA. The region from the mismatch to the nick is excised by exonuclease I and other activities, creating a large gap that is repaired by the activities of DNA polymerases (δ and ε), the replication factors (RPA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and replication factor C) and a ligase [reviewed in (Iyer et al. 2006)]. Interestingly, MMR and NER appear to have some overlapping recognition of certain types of DNA lesions. For example, complexes of MSH2 can bind to DNA adducts that are repaired by NER (Bertrand et al. 1998; Duckett et al. 1996; Li et al. 1996; Mello et al. 1996; Sancar 1999; Yamada et al. 1997; Yang 2006).. Recently, it has been demonstrated that NER and MMR proteins can interact in the recognition and binding of psoralen ICLs in vitro (Zhao et al. 2009).

Recombinational repair

HR involves the exchange of genetic information between DNA molecules that share sequence homology. Several models of HR have been proposed, based largely on data obtained from studies of bacteria and yeast (Delacote and Lopez 2008; Paques and Haber 1999; Shrivastav et al. 2008; Szostak et al. 1983; Wilson and Thompson 2007). Different models evoke either single-strand annealing (SSA) or double-strand break repair mechanisms, but a common theme is that single- or double-strand DNA breaks can provoke the recombination machinery. In yeast ICLs can enhance the frequency of HR up to 1,000-fold, presumably via the formation of a DSB intermediate during repair (Averbeck 1985; Averbeck et al. 1987; Greenberg et al. 2001; Saffran et al. 1992). In mammalian cells, up to a 10,000-fold stimulation of HR at sites of DSBs has been observed (Brenneman et al. 1996; Choulika et al. 1995; Rouet et al. 1994; Sargent et al. 1997; Smih et al. 1995). The yeast endonuclease, I-SceI, has been introduced into mammalian cells containing an I-SceI recognition sequence, as a means to induce a site-specific DSB (Brenneman et al. 1996; Choulika et al. 1995; Godwin et al. 1994; Rouet et al. 1994; Sargent et al. 1997; Smih et al. 1995). However, in this case the chromosomal locus must first be modified to carry the I-SceI recognition sequence and therefore, this technique cannot be used as a general tool to stimulate HR. Triplex technology (discussed below) can be used to circumvent the requirement for prior genome modification by targeting site-specific DNA damage to the chromosome at native sites. In the case of a DSB,the sister chromatid can serve as the donor fragment and the DSB can be repaired via a crossover or gene conversion event. In bacteria and yeast, similar to the mechanisms for DSBs, ICLs require both HR and NER factors for their repair (Cole 1973a; Jachymczyk et al. 1981; Magana-Schwencke et al. 1982), perhaps due to the formation of DSB intermediates (Dardalhon and Averbeck 1995; Jachymczyk et al. 1981; Magana-Schwencke et al. 1982; Malkova et al. 1996).

REPAIR OF PSORALEN ICLS

ICLs must be repaired for cell survival, because the adduct covalently links both strands of the DNA preventing required DNA metabolic functions such as replication and transcription. Psoralen is a planar, bifunctional intercalating agent containing a reactive furan ring joined at its 3′,2′ bond to a coumarin (benzpyrone) at the 6,7 position, that preferentially reacts at 5′ TpA sites (Hearst et al. 1984). The first proposed mechanism for the photoreaction of psoralen with DNA was reported in 1965 (Musajo et al. 1965). First, psoralen intercalates into the DNA, then upon exposure to UVA irradiation, cyclobutane monoadducts are formed with psoralen and the 5,6-double bond of pyrimidine, through either the 3,4-double bond on the pyrone ring or the 4′,5′-double bond on the furan ring. The furan-sided monoadduct can again absorb UVA, forming a crosslink between pyrimidine bases adjacent to one another in opposite strands. A model for an error-free repair pathway of ICLs in prokaryotes, involving both incision (via NER) and HR, has been proposed (Cheng et al. 1991; Cole 1973a; Van Houten et al. 1986). In this model, the UvrABC endonuclease generates incisions on either side of the ICL in the strand covalently linked to the furan ring. Next, Pol I generates a gap 3′ to the ICL, which provides a substrate for RecA-mediated recombination where a homologous DNA strand displaces the crosslinked strand. Finally, the DNA strand covalently linked to the pyrone ring is incised by UvrABC endonuclease, excising the lesion, and the reaction is completed by repair synthesis and ligation. The repair of ICLs in mammalian cells may follow a similar mechanism but is not yet fully understood. We have shown that UvrABC can efficiently incise TFO-directed psoralen ICLs in the presence or absence of the TFO (Christensen et al. 2008).

Model for ICL repair in mammalian cells

Proteins from both the NER and MMR mechanisms have been implicated in the repair of and response to ICLs in mammalian cells (Barre et al. 1999a; Datta et al. 2001; Faruqi et al. 2000; McHugh et al. 2001; Mustra et al.2007; Sarkar et al. 2006; Vasquez et al. 2002; Wu et al. 2005; Wu and Vasquez 2008; Zhang et al. 2002). It has been proposed that there is an S-phase and recombination-dependent error-free pathway and a recombination-independent error-generating pathway of ICL repair in human cells predominantly in G0 or G1-phase cells (McHugh and Sarkar 2006; Noll et al. 2006). HR clearly plays a role in the removal of ICLs in bacteria and yeast (Cole 1973a; Jachymczyk et al. 1981; Malkova et al. 1996), and has also been implicated in the repair of ICLs in mammals (De Silva et al. 2000; Dronkert and Kanaar 2001; Liu et al. 2008). It is increasingly evident that proteins from several DNA repair pathways cooperate in processing ICLs. For example, there is evidence to suggest that ERCC1-XPF can interact with MSH2 on ICLs (Lan et al. 2004). Like the budding yeast ortholog Rad1-Rad10, the ERCC1-XPF nuclease is involved in both NER and in certain types of HR involving recombination between repeated sequences, sometimes in a complex with MutSα (Bergstralh and Sekelsky 2008; Davies et al. 1995; Fishman-Lobell and Haber 1992; Niedernhofer et al. 2001; Paques and Haber 1999; Sargent et al. 1997). Another example of interplay between repair pathway components is the FANCJ interaction with MutLα in ICL processing (Peng et al. 2007). Cells deficient in ERCC1 or XPF function display extreme sensitivity to ICLs (Busch et al. 1997; Damia et al. 1998; Hoy et al. 1985). Similarly, cells from FA patients show extreme sensitivity to ICLs (Grompe and D’Andrea 2001; Papadopoulo et al. ; Poll et al. 1984), and some FA pathway proteins also play roles in HR (Nakanishi et al. 2005; Niedzwiedz et al. 2004; Thompson et al. 2005); see other reviews in this issue for potential roles of FA proteins in ICL repair. Figure 1 represents a model for ICL processing in both G0/G1 and S-phase cells.

MMR proteins in DNA damage responses

MMR proteins have been shown to play a role in cell death in response to N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine, 6-thioguanine, cisplatin, carboplatin, and B[a]P (Aebi et al. 1997; Fink et al. 1996; Hickman and Samson 1999; Wu et al. 1999). Studies also show that MMR proteins are required for S-phase checkpoint activation induced by ionizing irradiation (Brown et al. 2003), and G2-checkpoint activation induced by cisplatin, SN1 DNA methylators, and 6-thioguanine (Adamson et al. 2005; Aquilina et al. 1999; Cejka et al. 2003; Hawn et al. 1995; Stojic et al. 2004; Yamane et al. 2004; Yoshioka et al. 2006). Exposure to SN1 DNA methylators has been reported to activate MSH2- and MLH1- dependent phosphorylation of CHK1 through ATR (Stojic et al. 2004; Yoshioka et al. 2006). Psoralen ICLs can arrest human cells at S phase (Akkari et al. 2000) by active checkpoint signaling (Joerges et al. 2003). New evidence is developing to suggest that both ATM and ATR function as sensors in response to psoralen ICL exposure. The ICL-activated S-phase checkpoint depends on ATR-CHK1 and ATR-NBS1-FANCD2 pathways (Pichierri and Rosselli 2004). It has been demonstrated that MSH2 plays a role in the error-free repair of psoralen ICLs (Wu et al. 2005). Interestingly, we found that MLH1-deficient human cells are more resistant to ICLs, which differs from the effect of the MSH2-deficiency, which results in sensitivity to ICLs. As described in more detail below, we discovered that MLH1 (but not MSH2) is required for CHK2 phosphorylation and is involved in signaling apoptosis in response to ICLs, suggesting that MLH1 is involved in signaling psoralen ICL-induced checkpoint activation (Wu and Vasquez 2008). It is known that MSH2 can bind to CHK2, and that MLH1 can associate with ATM (Brown et al. 2003). Thus, the ATM activation and the lack of CHK2 phosphorylation found in MLH1- deficient cells following ICL exposure suggest that ATM requires MLH1, perhaps to interact with MSH2 and CHK2.

TARGETING ICLS TO MAMMALIAN GENES

The ability to target and manipulate specific mammalian genes is possible through the use of HR-based gene targeting strategies. However, the rate of HR in mammalian cells is orders of magnitude lower than random integration, which limits this strategy (Vasquez et al. 2001b). Triplex technology offers an alternative approach to genome modification that could potentially alleviate this problem. TFOs conjugated to DNA damaging agents, designed to bind unique sites in duplex DNA, can stimulate HR at specific genomic sites. For example, psoralen-conjugated TFOs have been shown to stimulate HR both on plasmids and on chromosomes in mammalian cells (Barre et al. 1999b; Faruqi et al. 2000; Faruqi et al. 1998; Liu et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009; Luo et al. 2000; Takasugi et al. 1991; Vasquez et al. 2001b). In addition, TFO-directed DNA damage can induce mutagenesis site-specifically, thereby directly inactivating the targeted gene [reviewed in (Jain et al. 2008)]. Majumdar et al. (2003) reported up to a 30% targeting efficiency of TFO-directed psoralen ICLs to the HPRT gene in Chinese hamster ovary cells (Majumdar et al. 2003). Because triplex technology is an efficient tool to direct site-specific ICLs in mammalian genomes, it may become possible to develop targeted therapies to mutate or correct any gene of interest in cultured cells and animals via triplex technology. Below we discuss the role of repair proteins from several repair mechanisms (e.g. NER, MMR, and HR) in the processing of TFO-directed psoralen ICLs in mammalian systems.

Triplex technology

TFOs bind duplex DNA with sequence specificity, forming triple-helical DNA structures. The binding specificity occurs via Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding in the major groove with the purine-rich strand of the underlying target duplex (Beal and Dervan 1991; Cooney et al. 1988). TFOs covalently linked to DNA damaging agents (e.g. psoralen; Figure 2) have been used to direct site-specific DNA damage (Barre et al. 2000; Christensen et al. 2004; Majumdar et al. 1998; Vasquez et al. 2001a; Vasquez et al. 1999), thereby enhancing the frequencies of mutation (Richards et al. 2005; Vasquez et al. 2001a; Vasquez et al. 1999; Wang and Glazer 1995) and recombination (Datta et al. 2001; Faruqi et al. 2000; Faruqi et al. 1996; Liu et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009; Luo et al. 2000; Rogers et al. 2002; Sandor and Bredberg 1995; Vasquez et al. 2001b) in an NER-dependent fashion (Barre et al. 1999a; Datta et al. 2001; Faruqi et al. 2000; Vasquez et al. 2002; Ziemba et al. 2001). Thus, triplex technology can be used to modify gene structure and function [for recent reviews see (Chin and Glazer 2009; Duca et al. 2008; Jain et al. 2008)]. Triplex-directed DNA damage is recognized by both NER and MMR DNA damage recognition proteins, and MMR proteins contribute to their error-free repair (Christensen et al. 2004; Lange et al. 2009; Reddy et al. 2005; Thoma et al. 2005; Vasquez et al. 2002; Wu et al. 2005; Wu and Vasquez 2008; Zhao et al. 2009). The repair processing of triplexes is of interest because of the expanding use of TFOs to modify mammalian genomes in vivo. TFOs can also be used to direct ICLs to specific sites and then removed by using a disulfide bridge between the psoralen derivative and the TFO, which can then be reduced in vitro, leaving only the ICL crosslinked to the DNA (Christensen et al. 2008).

Figure 2. Target duplex and psoralen-modified TFO.

(A) Space-filling model of a psoralen-modified TFO bound to its target duplex. The psoralen moiety is shown in yellow and the TFO is shown in red bound to the purine-rich strand of the target duplex (blue) in the major groove. The pyrimidine-rich strand is shown in green. (B) The TFO binding site is shown in red, the psoralen crosslinking site is shown in yellow, and the pyrimidine-rich (py) and purine-rich (pu) strands are depicted in green and blue, respectively. The sequence of the TFO binding site is shown in bold capital letters, the psoralen crosslinking site is underlined (Christensen et al. 2008)

REPAIR OF TFO-DIRECTED PSORALEN ICLS

It is important to understand how TFO-directed ICLs are processed to better develop targeted ICL-based therapies, and it is important to understand ICL processing (in the absence of a TFO) for improved use of current ICL-based chemotherapeutics. While TFO-directed psoralen ICLs are different DNA adducts than psoralen ICLs alone, they do share some similarities in their recognition and processing. For example, both lesions are recognized by NER and MMR damage recognition proteins, although the TFO enhances the affinity of these proteins for the lesion (Reddy et al. 2005; Thoma et al. 2005; Vasquez et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2009). Further, the two lesions share similarities in biochemical processing by the UvrABC system (Christensen et al. 2008). In cells, mutagenic processing of triplex structures, TFO-directed ICLs, and ICLs alone, requires NER (Sarkar et al. 2006; Vasquez et al. 2002; Wang et al. 1996). In addition to NER proteins, proteins from MMR and HR mechanisms have been implicated in the processing and/or responses to psoralen ICLs in the presence or absence of the third strand TFO. Some of these studies are summarized below.

NER processing of TFO-directed ICLs

It is clear that TFO conjugates are substrates for NER in mammalian cells and extracts, and that repair of such psoralen ICLs (alone or TFO-directed) can occur via NER, in an error-generating process conducive to mutagenesis in mammalian cells (Datta et al. 2001; Faruqi et al. 2000; Mustra et al. 2007; Sarkar et al. 2006; Vasquez et al. 2002; Wang et al. 1996). The first step in any repair mechanism is the recognition of damaged DNA. The NER DNA damage recognition complexes (XPA-RPA and XPC-RAD23B) can recognize and bind psoralen ICLs independently or together (Thoma et al. 2005; Vasquez et al. 2002). Interestingly, recognition of psoralen ICLs by XPC-RAD23B did not appear to be affected by XPA, but in contrast, RPA and XPC-RAD23B influenced each other when both proteins were present in the reaction, with a biphasic dependence on RPA concentrations (Thoma et al. 2005). At low concentrations of RPA and XPC-RAD23B, they each formed simple complexes with the damaged DNA, and competed with one another for binding to the lesion. At higher RPA concentrations, higher order complexes were formed containing XPC-RAD23B and RPA. Similar results were observed with these proteins on ICLs only (in the absence of the TFO), except that their binding affinities were reduced ~10-fold in the absence of the TFO (Thoma et al. 2005).

The high mobility group B1 (HMGB1) protein is the most abundant non-histone chromosomal protein in mammalian cells and is involved in several DNA metabolic activities, including regulation of transcription and of chromatin structure [reviewed in (Lange and Vasquez 2009)]. Recently, HMGB1 has been identified as a co-factor in NER, facilitating error-free repair of DNA lesions including psoralen ICLs, and by modifying chromatin in response to ICL-induced DNA damage (Lange et al. 2008). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking HMGB1 are hypersensitive to DNA damage induced by PUVA, demonstrating reduced survival and increased mutagenesis. Removal of DNA lesions (that are substrates for NER) from genomic DNA is reduced in the absence of HMGB1, indicating that HMGB1 is important for efficient NER. Moreover, Cells lacking HMGB1 show no increase in histone acetylation upon DNA damage, suggesting that HMGB1 is involved in relaxing the chromatin after DNA damage to allow repair proteins access to the lesion (Lange et al. 2008). HMGB1 has also been shown to bind psoralen ICLs with high affinity and specificity (Reddy et al. 2005), and interacts with the NER damage recognition complexes, XPA-RPA and XPC-RAD23B in a cooperative fashion on these lesions (Lange et al. 2009). Collectively, these results reveal a new role for HMGB1 in the error-free repair of psoralen ICLs.

Another NER protein, XPF (which contains endonuclease activity when in a complex with ERCC1) was also found to be necessary for the repair of TFO-directed ICLs (Degols et al. 1994). Richards et al, (2005) found that mammalian cells deficient in XPF (or ERCC1) processed TFO-directed ICLs in a more error-prone fashion with a bias toward deletion mutants, at the expense of point mutations (Richards et al. 2005). The authors concluded that ERCC1- XPF is involved in a process culminating in translesion DNA synthesis that leads to base substitutions. Psoralen ICLs are structurally asymmetric, and their repair in E.coli is also asymmetric, with the preferred incision site being on the furan side of the ICL (Van Houten et al. 1986); this is also the case with TFO-directed psoralen ICLs, incised by the UvrABC nuclease [the bacterial equivalent of mammalian NER; (Barre et al. 1999a; Christensen et al. 2008)]. NER has also been shown to suppress intra-molecular HR (via single-strand annealing) stimulated by TFO-directed psoralen ICLs. This was observed in cells deficient in XPA or in XPF, suggesting that functional NER was involved in this process (Zheng et al. 2006), perhaps in making the initial incisions to unhook the crosslink. Further evidence to support a role for NER proteins in ICL repair is discussed in a review by Richard Wood in this issue.

MMR processing of TFO-directed ICLs

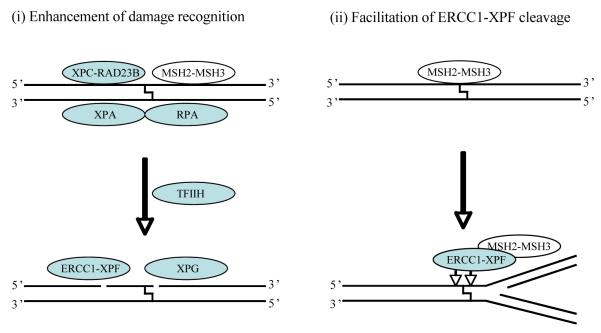

Studies by Zhang et al (2002) provided the first evidence that MMR proteins were involved in ICL repair (Zhang et al. 2002). In this study, it was demonstrated that MutSβ was involved in the recognition and uncoupling of ICLs in mammalian cell extracts (Zhang et al. 2002). Because it is known that NER and MMR damage/mismatch recognition proteins bind ICLs, we were interested in determining if these proteins interact together on ICLs. We found that MutSβ bound to TFO-directed ICLs with high affinity and specificity in vitro and in vivo, and that MutSβ interacted with XPA-RPA or XPC-RAD23B in recognizing these lesions. RPA forms a discrete complex on the ICLs in the presence or absence of MutSβ, but can also effectively form a ternary complex with MutSβ on these lesions, and XPA may facilitate this interaction (Zhao et al. 2009). In contrast, MutSβ and XPC-RAD23B formed discrete complexes with TFO-directed psoralen ICLs, suggesting that MutSβ and XPC-RAD23B bound psoralen ICLs independently (Zhao et al. 2009). Because either XPC-RAD23B or MutSβ can interact with XPA-RPA on psoralen ICLs (Thoma et al. 2005; Zhao et al. 2009), we propose that the binding of MutSβ to psoralen ICLs might facilitate repair of the lesion by NER proteins. These results indicate that proteins from more than one defined repair pathway can interact in the recognition of ICLs, and provide a possible mechanistic link by which the various repair proteins contribute to ICL processing. A model of potential interactions between NER and MMR proteins in processing ICLs in mammalian cells is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Potential interactions between NER and MMR proteins in processing ICLs.

Two general models by which MutSβ (MSH2-3) may participate in ICL processing. In (i), participates in damage recognition of an ICL and acts as an accessory factor to NER proteins for ICL unhooking. This is experimentally supported by the known binding of MutSβ to an ICL and the enhancement of incision and repair synthesis at an ICL. In (ii), MutSβ acts to help recruit and anchor ERCC1-XPF to an ICL. When the ICL is present at a structure such as a blocked replication fork, ERCC1-XPF can cleave near the crosslink. Alternatively, rather than unhooking, a cleavage reaction by ERCC1-XPF could occur during recombinational processing of a broken replication fork. A catalytic role for MLH1-PMS2 is also possible, for example utilizing its nuclease activity in an end-processing reaction

In addition to ICL recognition, we found that MSH2 was involved in the efficient processing of TFO-directed psoralen ICLs in both mammalian cells and extracts; however, it was not required for the psoralen-induced mutagenesis (Wu et al. 2005). This suggested that MSH2 may be involved in an error-free pathway of ICL repair. Deficiency of MSH2 rendered cells hypersensitive to ICLs, without diminishing their mutagenic potential, suggesting that MSH2 may be involved in a previously unrecognized mechanism for the error-free repair of ICLs (Wu et al. 2005). We speculated that MSH2 might channel the ICL into an error-free pathway involving HR. In support of this notion, MutSβ deficiency can lead to reduced levels of HR (Zhang et al. 2007). MMR can also inhibit non-homologous recombination (Calmann and Marinus 2004; Fabisiewicz and Worth 2001; Rayssiguier et al. 1989; Worth et al. 1994), such that the ICL-induced recombination events may be shifted toward gene conversion events (Liu et al. 2009).

Because MSH2 plays a role in the error-free repair of psoralen ICLs, we hypothesized that MLH1 might also be involved in the processing of psoralen ICLs, in a pathway with MSH2. Surprisingly, we instead found that MLH1-deficient human cells were more resistant to psoralen ICLs than isogenic wild-type cells, in contrast to the sensitivity to these lesions displayed by MSH2-deficient cells. Thus, MLH1 plays a unique role in cellular responses to ICLs, independent of its function in DNA repair. MLH1 deficiency conferred resistance to psoralen ICLs, and apoptosis was not as efficiently induced by psoralen ICLs in MLH1-deficient cells (Wu and Vasquez 2008). Strikingly, CHK2 phosphorylation was undetectable by immunoblotting in MLH1-deficient human cells following exposure to PUVA, and phosphorylation of CHK1 was reduced relative to wild-type cells after PUVA treatment, indicating that MLH1 is involved in signaling psoralen ICL-induced checkpoint activation. Importantly, MLH1 function was not required for the mutagenic repair of ICLs, similar to our findings with MSH2, and so its signaling function appears to have a role in maintaining genomic stability following exposure to ICL-induced DNA damage (Wu and Vasquez 2008). Thus, it appears that MSH2 and MLH1 have distinct and unique functions in the repair of and response to ICLs, outside their defined roles in MMR. These results reveal that human cells handle ICLs in a way that is strikingly different from that employed by bacteria and yeast (which appear to use only NER, HR, and TLS mechanisms), and opens a new field of inquiry into the role of MMR proteins in ICL repair and the interplay, competition, and cooperation among DNA repair pathway components in processing complex DNA lesions. For more details on the role of MMR proteins in ICL repair, see the review article, “Repair of DNA Interstrand Cross-links During S Phase of the Mammalian Cell Cycle”, authored by Randy Legerski in this issue.

HR processing of TFO-directed ICLs

TFO-directed ICLs can stimulate intra-molecular recombination between direct repeats, which is largely carried out by SSA, a sub-pathway of HR (Faruqi et al. 2000; Faruqi et al. 1996; Liu et al. 2008; Luo et al. 2000). TFO-directed ICLs have also been used to stimulate inter-molecular recombination for targeted gene correction (Chan et al. 1999; Liu et al. 2009), implicating HR pathways in the processing of TFO-directed ICLs. HR may play a role in the processing of DSB intermediates resulting from ICL processing (or replication fork stalling). Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that DSBs are generated in the processing of ICLs, particularly in yeast (Dardalhon and Averbeck 1995; De Silva et al. 2000; McHugh et al. 1999). However, two-sided DSBs are more recombinogenic than ICLs (Zheng et al. 2006), suggesting that DSBs are not an obligate intermediate in the processing of ICLs.

An alternative intermediate substrate in ICL repair may be a single-stranded gap and an oligonucleotide flap containing the psoralen ICL (Cole 1973b; Dronkert and Kanaar 2001; Faruqi et al. 1996; McHugh et al. 2001; Sladek et al. 1989). For example, in G0/G1 phase cells, psoralen ICLs may be repaired by dual incisions around the ICL on the purine-rich strand, which would displace the strand containing the psoralen adduct, producing a single-strand gap that could be bypassed by translesion synthesis polymerases (Faruqi et al. 2000; Faruqi et al. 1996; Kuraoka et al. 2000; Svoboda et al. 1993; Zheng et al. 2006). However, single-stranded gaps produced may also be repaired via an HR pathway during S-phase, resulting in gene conversion products (Liu et al. 2008). If a homologous sequence is available, then the 3′-OH end of the single-stranded gap may be able to initiate HR via a synthesis-dependent strand annealing mechanism (Ferguson and Holloman 1996; Nassif et al. 1994; Strathern et al. 1982). A more comprehensive review of the role of HR in ICL repair (authored by John Hinz) can be found in this issue.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

It is now clear that NER, MMR, and HR proteins are involved in the repair of and/or the response to TFO-directed ICLs (and ICLs in the absence of the TFO) in mammalian systems. Information obtained from ongoing studies will continue to provide insight into the mechanisms involved in ICL processing and removal in mammalian cells, and the interplay between repair proteins from several defined pathways in these processes. This knowledge will allow the development of pharmacological strategies to enhance repair of ICLs, with the aim of reducing the levels of genomic instability and cancer incidence. A better understanding of the processing of TFO-directed ICLs will facilitate the development of these molecules as targeted therapeutic agents. Additionally, these studies will allow the development of improved strategies for the use of ICL-inducing agents that are used clinically in the treatment of human disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms. Sarah Henninger for manuscript preparation. We also thank Dr. Richard Wood for useful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH - National Cancer Institute (CA097175 and CA093729) to KMV.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BER

base excision repair

- DSB

DNA double-strand break

- FA

Fanconi anemia

- HMGB1

high mobility group B1 protein

- HR

homologous recombination

- ICL

DNA interstrand crosslink

- MMR

mismatch repair

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- PUVA

psoralen plus UVA

- SSA

single-strand annealing

- TLS

translesion synthesis

- UV

ultraviolet radiation

Literature Cited

- Aboussekhra A, Biggerstaff M, Shivji MK, Vilpo JA, Moncollin V, Podust VN, Protic M, Hubscher U, Egly JM, Wood RD. Mammalian DNA nucleotide excision repair reconstituted with purified protein components. Cell. 1995;80(6):859–68. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson AW, Beardsley DI, Kim WJ, Gao Y, Baskaran R, Brown KD. Methylator-induced, mismatch repair-dependent G2 arrest is activated through Chk1 and Chk2. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(3):1513–26. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi S, Fink D, Gordon R, Kim HK, Zheng H, Fink JL, Howell SB. Resistance to cytotoxic drugs in DNA mismatch repair-deficient cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3(10):1763–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkari YM, Bateman RL, Reifsteck CA, Olson SB, Grompe M. DNA replication is required To elicit cellular responses to psoralen- induced DNA interstrand cross-links. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(21):8283–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8283-8289.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilina G, Crescenzi M, Bignami M. Mismatch repair, G(2)/M cell cycle arrest and lethality after DNA damage. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20(12):2317–26. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.12.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki M, Masutani C, Maekawa T, Watanabe Y, Yamada A, Kusumoto R, Sakai D, Sugasawa K, Ohkuma Y, Hanaoka F. Reconstitution of damage DNA excision reaction from SV40 minichromosomes with purified nucleotide excision repair proteins. Mutat Res. 2000;459(2):147–60. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(99)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck D. Relationship between lesions photoinduced by mono- and bi-functional furocoumarins in DNA and genotoxic effects in diploid yeast. Mutat Res. 1985;151(2):217–33. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(85)90074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck D, Averbeck S, Cundari E. Mutagenic and recombinogenic action of DNA monoadducts photoinduced by the bifunctional furocoumarin 8-methoxypsoralen in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Photochemistry & Photobiology. 1987;45(3):371–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb05389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barre F-X, Asseline U, Harel-Bellan A. Assymetric recognition of psoralen interstrand crosslinks by the nucleotide excision repair and the error-prone pathways. J Mol Biol. 1999a;286:1379–1387. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barre FX, Ait-Si-Ali S, Giovannangeli C, Luis R, Robin P, Pritchard LL, Helene C, Harel-Bellan A. Unambiguous demonstration of triple-helix-directed gene modification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(7):3084–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050368997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barre FX, Giovannangeli C, Helene C, Harel-Bellan A. Covalent crosslinks introduced via a triple helix-forming oligonucleotide coupled to psoralen are inefficiently repaired. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999b;27(3):743–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal PA, Dervan PB. Second structural motif for recognition of DNA by oligonucleotide-directed triple-helix formation. Science. 1991;251(4999):1360–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2003222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstralh DT, Sekelsky J. Interstrand crosslink repair: can XPF-ERCC1 be let off the hook? Trends Genet. 2008;24(2):70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti PJ, McCann JA. Toward a detailed understanding of base excision repair enzymes: transition state and mechanistic analyses of N-glycoside hydrolysis and N-glycoside transfer. Chem Rev. 2006;106(2):506–55. doi: 10.1021/cr040461t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand P, Tishkoff DX, Filosi N, Dasgupta R, Kolodner RD. Physical interaction between components of DNA mismatch repair and nucleotide excision repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(24):14278–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulikas T, Vougiouka M. Cisplatin and platinum drugs at the molecular level (Review) Oncol Rep. 2003;10(6):1663–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenneman M, Gimble FS, Wilson JH. Stimulation of intrachromosomal homologous recombination in human cells by electroporation with site-specific endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(8):3608–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KD, Rathi A, Kamath R, Beardsley DI, Zhan Q, Mannino JL, Baskaran R. The mismatch repair system is required for S-phase checkpoint activation. Nat Genet. 2003;33(1):80–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch DB, van Vuuren H, de Wit J, Collins A, Zdzienicka MZ, Mitchell DL, Brookman KW, Stefanini M, Riboni R, Thompson LH. Phenotypic heterogeneity in nucleotide excision repair mutants of rodent complementation groups 1 and 4. Mutat Res. 1997;383(2):91–106. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(96)00048-1. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmann MA, Marinus MG. MutS inhibits RecA-mediated strand exchange with platinated DNA substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(39):14174–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406104101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cejka P, Stojic L, Mojas N, Russell AM, Heinimann K, Cannavo E, di Pietro M, Marra G, Jiricny J. Methylation-induced G(2)/M arrest requires a full complement of the mismatch repair protein hMLH1. Embo J. 2003;22(9):2245–54. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PP, Lin M, Faruqi AF, Powell J, Seidman MM, Glazer PM. Targeted correction of an episomal gene in mammalian cells by a short DNA fragment tethered to a triplex-forming oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(17):11541–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Sancar A, Hearst JE. RecA-dependent incision of psoralen-crosslinked DNA by (A)BC excinuclease. Nucleic Acids Research. 1991;19(3):657–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.3.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin JY, Glazer PM. Repair of DNA lesions associated with triplex-forming oligonucleotides. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48(4):389–99. doi: 10.1002/mc.20501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choulika A, Perrin A, Dujon B, Nicolas JF. Induction of Homologous Recombination in Mammalian Chromosomes by Using the I-SceI System of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15(4):1968–1973. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LA, Conti CJ, Fischer SM, Vasquez KM. Mutation frequencies in murine keratinocytes as a function of carcinogenic status. Mol Carcinog. 2004;40(2):122–33. doi: 10.1002/mc.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LA, Wang H, Van Houten B, Vasquez KM. Efficient processing of TFO-directed psoralen DNA interstrand crosslinks by the UvrABC nuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(22):7136–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimino GD, Gamper HB, Isaacs ST, Hearst JE. Psoralens as photoactive probes of nucleic acid structure and function: organic chemistry, photochemistry, and biochemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:1154–1193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RS. Repair of DNA containing interstrand crosslinks in Escherichia coli: sequential excision and recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973a;70(4):1064–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.4.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RS. Repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA induced by psoralen plus light. Yale J Biol Med. 1973b;46(5):492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney M, Czernuszewicz G, Postel EH, Flint SJ, Hogan ME. Site-specific oligonucleotide binding represses transcription of the human c-myc gene in vitro. Science. 1988;241(4864):456–9. doi: 10.1126/science.3293213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damia G, Guidi G, D’Incalci M. Expression of genes involved in nucleotide excision repair and sensitivity to cisplatin and melphalan in human cancer cell lines. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(11):1783–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardalhon M, Averbeck D. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of the repair of psoralen plus UVA induced DNA photoadducts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutation Res. 1995;336:49–60. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(94)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta HJ, Chan PP, Vasquez KM, Gupta RC, Glazer PM. Triplex-induced recombination in human cell-free extracts. Dependence on XPA and HsRad51. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(21):18018–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AA, Friedberg EC, Tomkinson AE, Wood RD, West SC. Role of the Rad1 and Rad10 proteins in nucleotide excision repair and recombination. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(42):24638–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J, Hoeijmakers JH. Nucleotide excision repair and human syndromes. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(3):453–60. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva IU, McHugh PJ, Clingen PH, Hartley JA. Defining the roles of nucleotide excision repair and recombination in the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(21):7980–90. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7980-7990.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degols G, Clarenc JP, Lebleu B, Leonetti JP. Reversible inhibition of gene expression by a psoralen functionalized triple helix forming oligonucleotide in intact cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(24):16933–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delacote F, Lopez BS. Importance of the cell cycle phase for the choice of the appropriate DSB repair pathway, for genome stability maintenance: the trans-S double-strand break repair model. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(1):33–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.1.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronkert ML, Kanaar R. Repair of DNA interstrand cross-links. Mutat Res. 2001;486(4):217–47. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duca M, Vekhoff P, Oussedik K, Halby L, Arimondo PB. The triple helix: 50 years later, the outcome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(16):5123–38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckett DR, Drummond JT, Murchie AI, Reardon JT, Sancar A, Lilley DM, Modrich P. Human MutSalpha recognizes damaged DNA base pairs containing O6-methylguanine, O4-methylthymine, or the cisplatin-d(GpG) adduct. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(13):6443–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabisiewicz A, Worth L., Jr. Escherichia coli MutS,L modulate RuvAB-dependent branch migration between diverged DNA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(12):9413–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruqi AF, Datta HJ, Carroll D, Seidman MM, Glazer PM. Triple-helix formation induces recombination in mammalian cells via a nucleotide excision repair-dependent pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20(3):990–1000. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.990-1000.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruqi AF, Egholm M, Glazer PM. Peptide nucleic acid-targeted mutagenesis of a chromosomal gene in mouse cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1398–1403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruqi AF, Seidman MM, Segal DJ, Carroll D, Glazer PM. Recombination induced by triple helix-targeted DNA damage in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6820–6828. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedier A, Fink D. Mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes: implications for DNA damage signaling and drug sensitivity (review) Int. J. Oncol. 2004;24(4):1039–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DO, Holloman WK. Recombinational repair of gaps in DNA is asymmetric in Ustilago maydis and can be explained by a migrating D-loop model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(11):5419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink D, Nebel S, Aebi S, Zheng H, Cenni B, Nehme A, Christen RD, Howell SB. The role of DNA mismatch repair in platinum drug resistance. Cancer Res. 1996;56(21):4881–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishel R, Lescoe MK, Rao MR, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Garber J, Kane M, Kolodner R. The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cell. 1993;75(5):1027–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90546-3. [published erratum appears in Cell 1994 Apr 8;77(1):167] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman-Lobell J, Haber JE. Removal of nonhomologous DNA ends in double-strand break recombination: the role of the yeast ultraviolet repair gene RAD1. Science. 1992;258(5081):480–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1411547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet LC, Scharer OD. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian global genome nucleotide excision repair. Chem Rev. 2006;106(2):253–76. doi: 10.1021/cr040483f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin AR, Bollag RJ, Christie DM, Liskay RM. Spontaneous and restriction enzyme-induced chromosomal recombination in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(26):12554–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg RB, Alberti M, Hearst JE, Chua MA, Saffran WA. Recombinational and mutagenic repair of psoralen interstrand cross- links in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(34):31551–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grompe M, D’Andrea A. Fanconi anemia and DNA repair. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(20):2253–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.20.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzder SN, Habraken Y, Sung P, Prakash L, Prakash S. RAD26, the yeast homolog of human Cockayne’s syndrome group B gene, encodes a DNA-dependent ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(31):18314–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawn MT, Umar A, Carethers JM, Marra G, Kunkel TA, Boland CR, Koi M. Evidence for a connection between the mismatch repair system and the G2 cell cycle checkpoint. Cancer Res. 1995;55(17):3721–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Ingles CJ. Isolation of human complexes proficient in nucleotide excision repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(6):1136–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearst JE, Isaacs ST, Kanne D, Rapoport H, Straub K. The reaction of the psoralens with deoxyribonucleic acid. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 1984;17(1):1–44. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman MJ, Samson LD. Role of DNA mismatch repair and p53 in signaling induction of apoptosis by alkylating agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(19):10764–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy CA, Thompson LH, Mooney CL, Salazar EP. Defective DNA cross-link removal in Chinese hamster cell mutants hypersensitive to bifunctional alkylating agents. Cancer Res. 1985;45(4):1737–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishino Y, Nishino T, Morikawa K. Mechanisms of maintaining genetic stability by homologous recombination. Chem Rev. 2006;106(2):324–39. doi: 10.1021/cr0404803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Modrich PL. DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106(2):302–23. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jachymczyk WJ, von Borstel RC, Mowat MR, Hastings PJ. Repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires two systems for DNA repair: the RAD3 system and the RAD51 system. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1981;182(2):196–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00269658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Wang G, Vasquez KM. DNA triple helices: biological consequences and therapeutic potential. Biochimie. 2008;90(8):1117–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joerges C, Kuntze I, Herzinger T. Induction of a caffeine-sensitive S-phase cell cycle checkpoint by psoralen plus ultraviolet A radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22(40):6119–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleijer WJ, Laugel V, Berneburg M, Nardo T, Fawcett H, Gratchev A, Jaspers NG, Sarasin A, Stefanini M, Lehmann AR. Incidence of DNA repair deficiency disorders in western Europe: Xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7(5):744–50. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer KH, Patronas NJ, Schiffmann R, Brooks BP, Tamura D, DiGiovanna JJ. Xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome: a complex genotype-phenotype relationship. Neuroscience. 2007;145(4):1388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraoka I, Kobertz WR, Ariza RR, Biggerstaff M, Essigmann JM, Wood RD. Repair of an interstrand DNA cross-link initiated by ERCC1-XPF repair/recombination nuclease. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(34):26632–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan L, Hayashi T, Rabeya RM, Nakajima S, Kanno S, Takao M, Matsunaga T, Yoshino M, Ichikawa M, Riele H. Functional and physical interactions between ERCC1 and MSH2 complexes for resistance to cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) in mammalian cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3(2):135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.10.005. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange SS, Mitchell DL, Vasquez KM. High mobility group protein B1 enhances DNA repair and chromatin modification after DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(30):10320–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803181105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange SS, Reddy MC, Vasquez KM. Human HMGB1 directly facilitates interactions between nucleotide excision repair proteins on triplex-directed psoralen interstrand crosslinks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8(7):865–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange SS, Vasquez KM. HMGB1: The jack-of-all-trades protein is a master DNA repair mechanic. Mol Carcinog. 2009 doi: 10.1002/mc.20544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley PD, Phillips DH. DNA adducts from chemotherapeutic agents. Mutat Res. 1996;355(1- 2):13–40. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann AR. DNA repair-deficient diseases, xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy. Biochimie. 2003;85(11):1101–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibeling D, Laspe P, Emmert S. Nucleotide excision repair and cancer. J Mol Histol. 2006;37(5-7):225–38. doi: 10.1007/s10735-006-9041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GM, Wang H, Romano LJ. Human MutSalpha specifically binds to DNA containing aminofluorene and acetylaminofluorene adducts. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(39):24084–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Nairn RS, Vasquez KM. Processing of triplex-directed psoralen DNA interstrand crosslinks by recombination mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(14):4680–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Nairn RS, Vasquez KM. Targeted gene conversion induced by triplex-directed psoralen interstrand crosslinks in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(19):6378–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z, Macris MA, Faruqi AF, Glazer PM. High-frequency intrachromosomal gene conversion induced by triplex- forming oligonucleotides microinjected into mouse cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(16):9003–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160004997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magana-Schwencke N, Henriques JA, Chanet R, Moustacchi E. The fate of 8- methoxypsoralen photoinduced crosslinks in nuclear and mitochondrial yeast DNA: comparison of wild-type and repair-deficient strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(6):1722–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar A, Khorlin A, Dyatkina N, Lin FL, Powell J, Liu J, Fei Z, Khripine Y, Watanabe KA, George J. Targeted gene knockout mediated by triple helix forming oligonucleotides. Nat Genet. 1998;20(2):212–4. doi: 10.1038/2530. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar A, Puri N, Cuenoud B, Natt F, Martin P, Khorlin A, Dyatkina N, George AJ, Miller PS, Seidman MM. Cell cycle modulation of gene targeting by a triple helix-forming oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(13):11072–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkova A, Ivanov EL, Haber JE. Double-strand break repair in the absence of RAD51 in yeast: a possible role for break-induced DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(14):7131–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh PJ, Gill RD, Waters R, Hartley JA. Excision repair of nitrogen mustard-DNA adducts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(16):3259–66. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh PJ, Sarkar S. DNA interstrand cross-link repair in the cell cycle: a critical role for polymerase zeta in G1 phase. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(10):1044–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.10.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh PJ, Spanswick VJ, Hartley JA. Repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks: molecular mechanisms and clinical relevance. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(8):483–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello JA, Acharya S, Fishel R, Essigmann JM. The mismatch-repair protein hMSH2 binds selectively to DNA adducts of the anticancer drug cisplatin. Chem Biol. 1996;3(7):579–89. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishina Y, Duguid EM, He C. Direct reversal of DNA alkylation damage. Chem Rev. 2006;106(2):215–32. doi: 10.1021/cr0404702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momtaz K, Fitzpatrick TB. The benefits and risks of long-term PUVA photochemotherapy. Dermatol Clin. 1998;16(2):227–34. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu D, Park CH, Matsunaga T, Hsu DS, Reardon JT, Sancar A. Reconstitution of humanDNA repair excision nuclease in a highly defined system. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(6):2415–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musajo L, Rodighiero G, Dall’Acqua F. Evidences of a photoreaction of the photosensitizing furocoumarins with DNA and with pyrimidien nucleosides and nucleotides. Experimentia. 1965;21:24–26. doi: 10.1007/BF02136363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustra DJ, Warren AJ, Wilcox DE, Hamilton JW. Preferential binding of human XPA to the mitomycin C-DNA interstrand crosslink and modulation by arsenic and cadmium. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;168(2):159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Yang YG, Pierce AJ, Taniguchi T, Digweed M, D’Andrea AD, Wang ZQ, Jasin M. Human Fanconi anemia monoubiquitination pathway promotes homologous DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(4):1110–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407796102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassif N, Penney J, Pal S, Engels WR, Gloor GB. Efficient copying of nonhomologous sequences from ectopic sites via P-element-induced gap repair. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(3):1613–25. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedernhofer LJ, Essers J, Weeda G, Beverloo B, de Wit J, Muijtjens M, Odijk H, Hoeijmakers JH, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1-Xpf is required for targeted gene replacement in embryonic stem cells. Embo J. 2001;20(22):6540–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedz W, Mosedale G, Johnson M, Ong CY, Pace P, Patel KJ. The Fanconi anaemia gene FANCC promotes homologous recombination and error-prone DNA repair. Mol Cell. 2004;15(4):607–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll DM, Mason TM, Miller PS. Formation and repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA. Chem Rev. 2006;106(2):277–301. doi: 10.1021/cr040478b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh DH, Hanawalt PC. Triple helix-forming oligonucleotides target psoralen adducts to specific chromosomal sequences in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4734–4742. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.24.4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh DH, King BA, Boxer SG, Hanawalt PC. Spatially localized generation of nucleotide sequence-specific DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(20):11271–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201409698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulo D, Averbeck D, Moustacchi E. The fate of 8-methoxypsoralen-photoinducedDNA interstrand crosslinks in Fanconi’s anemia cells of defined genetic complementation groups. Mutation Research. 1987;184(3):271–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(87)90026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paques F, Haber JE. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63(2):349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic-Calic N, Muminhodzic K, Zildzic M, Smajic M, Gegic A, Alibegovic E, Salkic N, Jovanovic P, Basic M, Iljazovic S. Genetics, clinical manifestations and management of FAP and HNPCC. Med Arh. 2007;61(4):256–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M, Litman R, Xie J, Sharma S, Brosh RM, Jr., Cantor SB. The FANCJ/MutLalpha interaction is required for correction of the cross-link response in FA-J cells. Embo J. 2007;26(13):3238–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins BD, Wensel TG, Vasquez KM, Wilson JH. Psoralen photo-cross-linking by triplex-forming oligonucleotides at multiple sites in the human rhodopsin gene. Biochemistry. 1999;38(39):12850–9. doi: 10.1021/bi9902743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichierri P, Rosselli F. The DNA crosslink-induced S-phase checkpoint depends on ATR-CHK1 and ATR-NBS1-FANCD2 pathways. Embo J. 2004;23(5):1178–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poll EH, Arwert F, Kortbeek HT, Eriksson AW. Fanconi anaemia cells are not uniformly deficient in unhooking of DNA interstrand crosslinks, induced by mitomycin C or 8- methoxypsoralen plus UVA. Hum Genet. 1984;68(3):228–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00418393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayssiguier C, Thaler DS, Radman M. The barrier to recombination between Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium is disrupted in mismatch-repair mutants. Nature. 1989;342(6248):396–401. doi: 10.1038/342396a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MC, Christensen J, Vasquez KM. Interplay between Human High Mobility Group Protein 1 and Replication Protein A on Psoralen-Cross-linked DNA. Biochemistry. 2005;44(11):4188–4195. doi: 10.1021/bi047902n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MC, Vasquez KM. Repair of genome destabilizing lesions. Radiat Res. 2005;164(4 Pt 1):345–56. doi: 10.1667/rr3419.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Liu ST, Majumdar A, Liu JL, Nairn RS, Bernier M, Maher V, Seidman MM. Triplex targeted genomic crosslinks enter separable deletion and base substitution pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(17):5382–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FA, Vasquez KM, Egholm M, Glazer PM. Site-directed recombination via bifunctional PNA-DNA conjugates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):16695–700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262556899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M. Introduction of double-strand breaks into the genome of mouse cells by expression of a rare-cutting endonuclease. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 1994;14(12):8096–106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffran WA, Cantor CR, Smith ED, Magdi M. Psoralen damage-induced plasmid recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: dependence on RAD1 and RAD52. Mutation Research. 1992;274(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(92)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath D, Plunkett W. The role of DNA repair in chronic lymphocytic leukemia pathogenesis and chemotherapy resistance. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9(5):361–7. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A. Excision repair invades the territory of mismatch repair. Nat Genet. 1999;21(3):247–9. doi: 10.1038/6753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandor Z, Bredberg A. Triple helix directed psoralen adducts induce a low frequency of recombination in an SV-40 shuttle vector. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1263:235–240. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00109-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent RG, Rolig RL, Kilburn AE, Adair GM, Wilson JH, Nairn RS. Recombination-dependent deletion formation in mammalian cells deficient in the nucleotide excision repair gene ERCC1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(24):13122–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Davies AA, Ulrich HD, McHugh PJ. DNA interstrand crosslink repair during G1 involves nucleotide excision repair and DNA polymerase zeta. Embo J. 2006;25(6):1285–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastav M, De Haro LP, Nickoloff JA. Regulation of DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Cell Res. 2008;18(1):134–47. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek FM, Munn MM, Rupp WD, Howard-Flanders P. In vitro repair of psoralen-DNA cross-links by RecA, UvrABC, and the 5′-exonuclease of DNA polymerase I. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264(12):6755–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smih F, Rouet P, Romanienko PJ, Jasin M. Double-strand breaks at the target locus stimulate gene targeting in embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(24):5012–5019. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojic L, Mojas N, Cejka P, Di Pietro M, Ferrari S, Marra G, Jiricny J. Mismatch repair-dependent G2 checkpoint induced by low doses of SN1 type methylating agents requires the ATR kinase. Genes Dev. 2004;18(11):1331–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.294404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathern JN, Klar AJ, Hicks JB, Abraham JA, Ivy JM, Nasmyth KA, McGill C. Homothallic switching of yeast mating type cassettes is initiated by a double-stranded cut in the MAT locus. Cell. 1982;31(1):183–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda DL, Taylor JS, Hearst JE, Sancar A. DNA repair by eukaryotic nucleotide excision nuclease. Removal of thymine dimer and psoralen monoadduct by HeLa cell-free extract and of thymine dimer by Xenopus laevis oocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(3):1931–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak JW, Orr-Weaver TL, Rothstein RJ, Stahl FW. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell. 1983;33(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasugi M, Guendouz A, Chassignol M, Decout JL, Lhomme J, Thuong NT, Helene C. Sequence-specific photo-induced cross-linking of the two strands of double-helical DNA by a psoralen covalently linked to a triple helix-forming oligonucleotide. Pro. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88(13):5602–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma BS, Wakasugi M, Christensen J, Reddy MC, Vasquez KM. Human XPC-hHR23B interacts with XPA-RPA in the recognition of triplex-directed psoralen DNA interstrand crosslinks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(9):2993–3001. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LH, Hinz JM, Yamada NA, Jones NJ. How Fanconi anemia proteins promote the four Rs: replication, recombination, repair, and recovery. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2005;45(2- 3):128–42. doi: 10.1002/em.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten B, Gamper H, Holbrook SR, Hearst JE, Sancar A. Action mechanism of ABC excision nuclease on a DNA substrate containing a psoralen crosslink at a defined position. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(21):8077–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez KM, Christensen J, Li L, Finch RA, Glazer PM. Human XPA and RPA DNA repair proteins participate in specific recognition of triplex-induced helical distortions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(9):5848–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082193799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez KM, Dagle JM, Weeks DL, Glazer PM. Chromosome targeting at short polypurine sites by cationic triplex- forming oligonucleotides. J Biol Chem. 2001a;14:14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez KM, Glazer PM. Triplex-forming oligonucleotides: principles and applications. Q Rev Biophys. 2002;35(1):89–107. doi: 10.1017/s0033583502003773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez KM, Marburger K, Intody Z, Wilson JH. Manipulating the mammalian genome by homologous recombination. PNAS. 2001b;98(15):8403–8410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111009698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez KM, Narayanan L, Glazer PM. Specific mutations induced by triplex-forming oligonucleotides in mice. Science. 2000;290(5491):530–533. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez KM, Wang G, Havre PA, Glazer PM. Chromosomal mutations induced by triplex-forming oligonucleotides in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(4):1176–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez KM, Wensel TG, Hogan ME, Wilson JH. High-efficiency triple-helix-mediated photo-cross-linking at a targeted site within a selectable mammalian gene. Biochemistry. 1996;35(33):10712–9. doi: 10.1021/bi960881f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Glazer PM. Altered repair of targeted psoralen photoadducts in the context of an oligonucleotide-mediated triple helix. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270(39):22595–22601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Seidman MM, Glazer PM. Mutagenesis in mammalian cells induced by triple helix formation and transcription-coupled repair. Science. 1996;271:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SQ, Setlow R, Berwick M, Polsky D, Marghoob AA, Kopf AW, Bart RS. Ultraviolet A and melanoma: a review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001;44(5):837–46. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DM, 3rd, Thompson LH. Molecular mechanisms of sister-chromatid exchange. Mutat Res. 2007;616(1-2):11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worth L, Jr., Clark S, Radman M, Modrich P. Mismatch repair proteins MutS and MutL inhibit RecA-catalyzed strand transfer between diverged DNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(8):3238–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JX, Gu LY, Wang HX, Geacintov NE, Li GM. Mismatch repair processing of carcinogen-DNA adducts triggers apoptosis. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 1999;19(12):8292–8301. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Christensen LA, Legerski RJ, Vasquez KM. Mismatch repair participates in error-free processing of DNA interstrand crosslinks in human cells. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:551–557. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Vasquez KM. Human MLH1 protein participates in genomic damage checkpoint signaling in response to DNA interstrand crosslinks, while MSH2 functions in DNA repair. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(9):e1000189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Oregan E, Brown R, Karran P. Selective Recognition Of a Cisplatin-Dna Adduct By Human Mismatch Repair Proteins. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(3):491–495. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.3.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane K, Taylor K, Kinsella TJ. Mismatch repair-mediated G2/M arrest by 6-thioguanine involves the ATR-Chk1 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318(1):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. Poor base stacking at DNA lesions may initiate recognition by many repair proteins. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5(6):654–66. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka K, Yoshioka Y, Hsieh P. ATR kinase activation mediated by MutSalpha an MutLalpha in response to cytotoxic O6-methylguanine adducts. Mol Cell. 2006;22(4):501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Liu X, Li L, Legerski R. Double-strand breaks induce homologous recombinational repair of interstrand cross-links via cooperation of MSH2, ERCC1-XPF, REV3, and the Fanconi anemia pathway. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6(11):1670–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Lu X, Zhang X, Peterson CA, Legerski RJ. hMutSbeta is required for the recognition and uncoupling of psoralen interstrand cross-links in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(7):2388–97. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2388-2397.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Jain A, Iyer RR, Modrich PL, Vasquez KM. Mismatch repair and nucleotide excision repair proteins cooperate in the recognition of DNA interstrand crosslinks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(13):4420–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Wang X, Legerski RJ, Glazer PM, Li L. Repair of DNA interstrand cross-links: interactions between homology-dependent and homology-independent pathways. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5(5):566–74. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemba A, Derosier LC, Methvin R, Song CY, Clary E, Kahn W, Milesi D, Gorn V, Reed M, Ebbinghaus S. Repair of triplex-directed DNA alkylation by nucleotide excision repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(21):4257–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.21.4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]