Abstract

The metal-dependent histone deacetylases (HDACs) adopt an α/β protein fold first identified in rat liver arginase. Despite insignificant overall amino acid sequence identity, these enzymes share a strictly conserved metal-binding site with divergent metal specificity and stoichiometry. HDAC8, originally thought to be a Zn2+-metallohydrolase, exhibits increased activity with Co2+ and Fe2+ cofactors based on kcat/KM (Gantt, S. L., Gattis, S. G. & Fierke, C. A. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 6170–6178). Here, we report the first X-ray crystal structures of metallo-substituted HDAC8: Co2+-HDAC8, D101L Co2+-HDAC8, D101L Mn2+-HDAC8, and D101L Fe2+-HDAC8, each complexed with the inhibitor M344. Metal content of protein samples in solution is confirmed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. For the crystalline enzymes, peaks in Bijvoet difference Fourier maps calculated from X-ray diffraction data collected near the respective elemental absorption edges confirm metal substitution. Additional solution studies confirm incorporation of Cu2+; Fe3+ and Ni2+ do not bind under conditions tested. The metal dependence of the substrate KM values and the Ki values of hydroxamate inhibitors that chelate the active site metal are consistent with substrate-metal coordination in the precatalytic Michaelis complex that enhances catalysis. Additionally, although HDAC8 binds Zn2+ nearly 106-fold more tightly than Fe2+, the affinities for both metal ions are comparable to the readily exchangeable metal concentrations estimated in living cells, suggesting that HDAC8 could bind either or both Fe2+ or Zn2+ in vivo.

Posttranslational acetylation of the lysine side chain is documented in many proteins and has diverse effects on protein activity (1). For example, acetylation of lysine residues at the N-termini of histone proteins in the nucleosome is critical for regulating the accessibility of the genetic code during replication, transcription, and repair (2–6). Among the array of covalent modifications described to date in defining the “histone code”, those involving histone lysine residues are particularly intriguing. Acetylation and deacetylation reactions are catalyzed by the enzymes histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase (HDAC), respectively. The acetylation of histone lysine residues alters interactions with the DNA backbone, e.g., as observed in the X-ray crystal structure of the nucleosome (7). Additionally, proteins containing the bromodomain have increased binding affinity for other proteins containing acetyl-L-lysine residues, implicating acetylation in the regulation of protein-protein interactions (8–12).

There are 18 known HDAC enzymes divided phylogenetically into four classes: class I (HDAC1-3 and HDAC8), class II (HDAC4-7 and HDAC9,10), class III (sirtuins 1–7), and class IV (HDAC11) (13). Class I, II, and IV HDACs are metalloenzymes that require a divalent metal ion for substrate binding and catalysis. The class III enzymes, termed sirtuins due to their homology with yeast Sir2, have a protein fold and catalytic mechanism that differ from those of class I, II, and IV enzymes. Although the class I, II, and IV enzymes are referred to as histone deacetylases based on genomic sequence mining using the first identified HDAC (HDAC1; see (14)), HDAC enzymes can function to deacetylate many acetylated protein substrates in addition to histones and in various cellular locations beyond the nucleus (15). For example, while the class I enzyme HDAC8 is localized within the nucleus (14, 16), HDAC8 is also found in the cytosol of smooth muscle cells where it associates with the α-actin cytoskeleton (17, 18). In another example, class II HDAC enzymes are shuttled back and forth between the nucleus and cytosol depending on their interaction with the 14-3-3 transporter protein, which is mediated by phosphorylation (19).

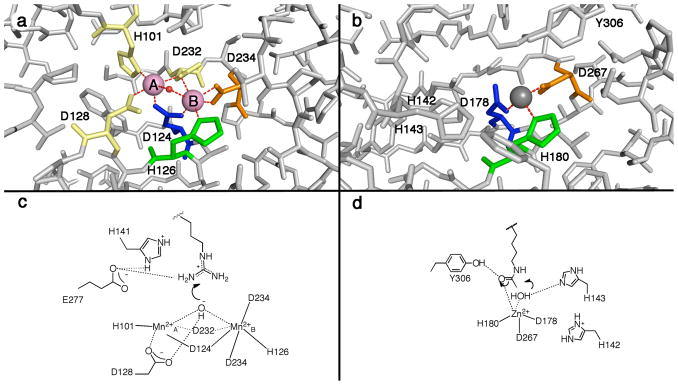

Class I, II, and IV HDAC enzymes adopt the α/β fold first observed for the binuclear manganese metalloenzyme arginase, despite sharing extremely low amino acid sequence identity (less than 13%) (20, 21). Arginase catalyzes the hydrolysis of L-arginine to form L-ornithine and urea. The first structure of a histone deacetylase-like protein from A. aeolicus revealed a conserved metal binding site in the active site, corresponding to the MnB2+ site of arginase, in which a single catalytic Zn2+ ion is coordinated by two aspartate residues and a histidine residue (Figure 1) (21). Subsequently determined crystal structures of human HDAC8, HDAC4, HDAC7, and bacterial histone deacetylase-like amidohydrolase reveal strict conservation of this metal binding site (22–26). In contrast, the Mn2+A site of arginase is not conserved in HDAC enzymes.

Figure 1.

(a) Binuclear manganese cluster in rat arginase I (1RLA) (20); Mn2+ ions appear as pink spheres, and the metal-bridging hydroxide ion is shown as a red sphere. (b) Zinc binding site in HDAC8 (1T64) (23); the Zn2+ ion appears as a gray sphere, and the zinc-bound inhibitor trichostatin A is not shown for clarity. Metal ligands topologically identical to those in rat arginase I are color-coded accordingly. (c) First step in the proposed arginase mechanism (67, 68). (d) First step in the proposed HDAC8 mechanism (21, 36, 47).

While it is clear that a single transition metal ion is required for catalysis by HDAC enzymes, the precise identity of the physiologically relevant metal ion is somewhat ambiguous. Intriguingly, the active site metal ligands of HDAC and HDAC-like enzymes (Asp2His) are unusual for a zinc-dependent hydrolase (Figure 1). Considering the presence of two negatively-charged aspartate residues, which are considered “hard” ligands, the binding of a “hard” metal ion is expected, e.g., the Mn2+ ions found in the active site of arginase (20). Moreover, activity measurements reveal that the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) of HDAC8 is enhanced in the presence of Co2+ and Fe2+ compared with Zn2+ (27). Notably, many metallohydrolases are activated by a single Fe2+ ion for catalysis, including peptide deformylase, methionyl aminopeptidase, LuxS, γ-carbonic anhydrase, cytosine deaminase, atrazine chlorohydrolase and UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase (LpxC) (28–35). Some of these metalloenzymes were initially mischaracterized as Zn2+-metallohydrolases due to the facile oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, which then dissociated and thereby allowed the binding of adventitious Zn2+ (28, 30). It is possible that HDAC enzymes have been similarly mischaracterized.

Here, we report the X-ray crystal structures of HDAC8 containing the high-activity metal ions Co2+ or Fe2+ as well as the low-activity metal ion Mn2+ with a bound hydroxamate inhibitor. Metal ion content is confirmed in solution by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, and in the crystal by Bijvoet difference Fourier analysis. These results, along with affinity data of HDAC8 for the physiologically relevant metal ions Zn2+ and Fe2+, highlight the evolution of metal ion selectivity and stoichiometry in arginase and arginase-related metalloenzymes such as HDAC.

Materials and Methods

Protein preparation

Recombinant HDAC8-His was prepared and purified as previously described (36) and concentrated to 2–12 mg/mL for metal exchange dialysis. To prevent trace metal contamination, all plasticware was presoaked with 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and triple rinsed with Millipure H2O; glassware was not used in these experiments. Plastic disposables, including pipet tips and micro-centrifuge tubes, were certified trace metal-free. Sodium hydroxide (Sigma, 99.999%) was used to titrate 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (Ambion). Dialysis cassettes (Pierce) and syringes with needles were presoaked with 1 mM EDTA and extensively washed with Millipure H2O. When necessary, anaerobic conditions were achieved using either the captair® pyramid glove bag filled with argon or nitrogen, or an anaerobic chamber (Coy, Grass Lake, MI).

Metal-free HDAC8 was generated by dialyzing purified HDAC8 twice into 500 mL of 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 10 μM dipicolinic acid, followed by buffer exchange into 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.5) and 0.1 mM EDTA, and finally 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.5) and 1 μM EDTA. Crystallization buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP; added to maintain reduced cysteines and/or Fe2+)) was pre-treated with Chelex resin (Sigma) and used for the final dialysis. To prepare each metal-substituted enzyme, the metal-free enzyme was dialyzed into crystallization buffer supplemented with 100 μM of either CoCl2, FeCl2, MnCl2, CuCl2 (Sigma, 99.999%), NiCl2, or FeCl3 (Hampton Research, >98%), followed by a final dialysis into crystallization buffer pre-treated with Chelex resin to remove any excess unbound divalent metal ions. Metal content was quantified by inductively coupled plasma emission mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) using a facility in the Geology Department at the University of Michigan. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford analysis (37) to determine metal:protein ratios.

Inhibitor affinity measurements

The concentration of metal-free HDAC8 was determined using Ellman’s Reagent, as previously described (27). Apo-HDAC8 was incubated with equimolar CoCl2, FeCl2, or ZnCl2 on ice for 1 h, and metallosubstituted HDAC8 (0.5 μM) was assayed with 50 μM Fluor de Lys HDAC8 substrate (BIOMOL) at 25 °C in 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 140 mM NaCl, and 2.7 mM KCl pretreated with Chelex resin. Fe2+-HDAC8 activity was measured in the presence of 5 mM sodium dithionite; these conditions have no effect on enzyme activity when tested with Zn2+-HDAC8. Assays were stopped with Developer II solution (BIOMOL) and 10 μM trichostatin A. Inhibition constants (Ki) were calculated for a minimum of 12 inhibitor concentrations using the Cheng-Prusoff equation (38).

Protein crystallization

Considering that HDAC8 does not readily crystallize without a bound ligand, complexes with the inhibitor 4-(dimethylamino)-N-[7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl]-benzamide (designated “M344” (23, 39)) were prepared to obtain diffraction quality crystals. The inhibitor M344 was purchased from Sigma and used without further purification for cocrystallization experiments (2 mM). Since D101L HDAC8 generally yielded better quality crystals that diffracted to higher resolution, both wild-type and mutant enzymes were used for crystallographic studies. For crystallization of Co2+- or Mn2+-substituted enzymes, a 4 μL sitting drop of 5 mg/mL Co2+- or Mn2+-HDAC8-M344 complex was mixed with a 4 μL drop of precipitant buffer (0.1 M 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid (MES) (pH 5.3), 0–5% polyethylene glycol (PEG) monomethylether (MME) 550, 2 mM TCEP, and 0.03 mM Gly-Gly-Gly, pretreated with Chelex resin) and equilibrated against a 600 μL reservoir of precipitant buffer at room temperature. Crystals formed after 3 – 4 weeks for the D101L and wild-type Co2+-HDAC8-M344 complexes, and 1–2 days for the D101L and wild-type Mn2+-HDAC8-M344 complexes. Suitable crystals of the Co2+-HDAC8-M344 complexes were harvested and cryoprotected in 25 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM MES (pH 5.8), 75 mM KCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 50 μM M344, 10% PEG MME 550, and 30% glycerol and flash cooled in liquid nitrogen. The wild-type Mn2+-HDAC8-M344 complex yielded thin clusters of plate-like crystals; however, the D101L Mn2+-HDAC8-M344 complex formed higher-quality crystals that were harvested and cryoprotected in 30% Jeffamine ED-2001 and 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.0) and flash cooled in liquid nitrogen.

For crystallization of the Fe2+-substituted enzyme, a 4 μL sitting drop of 5 mg/mL Fe2+-HDAC8-M344 complex was mixed with a 4 μL drop of precipitant buffer (0.1 M MES (pH 6.8), 10–18% PEG 35K, 2 mM TCEP, and 0.03 M Gly-Gly-Gly, pretreated with Chelex resin) and equilibrated against a 600 μL reservoir of precipitant buffer at room temperature. Sodium dithionite was added to the reservoir before sealing with crystallization tape, and trays were stored under a nitrogen atmosphere using either the captair® pyramid glove bag or a dessicator equipped with a vacuum and gas port. Wild-type Fe2+-HDAC8 complexed with M344 formed plate-like crystals within 1–2 days that were unsuitable for X-ray data collection. However, crystals of the D101L Fe2+-HDAC8-M344 complex were larger and more suitable for X-ray data collection. Crystals were harvested and cryoprotected in 25 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM MES (pH 6.8), 75 mM KCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 50 μM M344, 20% PEG 2,000, and 20% glycerol under a nitrogen atmosphere and flash cooled in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection and structure determination

Diffraction data for Co2+- and Fe2+-HDAC8 samples were measured on beamline 24-ID-C at the Advanced Photon Source, Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (APS, NECAT, Argonne, IL). Data for the D101L Co2+- and Fe2+-HDAC8-M344 structures were collected at 11.566 keV/1.0720 Å; for the measurement of Bijvoet differences, data were collected at 7.725 keV/1.6050 Å or 7.120 keV/1.7143 Å for Co2+ or Fe2+ derivatives, respectively. Data for the D101L Mn2+-HDAC8-M344 structure were collected on our home source (Rigaku IV++ image plate area detector mounted on a Rigaku RU200HB rotating anode X-ray generator; 8.048 keV/1.5406 Å) and on beamline X25 at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS, Brookhaven National Laboratory, NY). Crystallographic and data collection statistics are recorded in Tables 1 and 2. Data were indexed and merged using HKL2000 (40). Molecular replacement calculations were performed with PHASER (41) using the structure of either wild-type or D101L HDAC8 (PDB accession codes 1W22 or 3EW8, respectively) minus ligands and solvent atoms as a search probe. Iterative cycles of refinement were performed using CNS (42) or REFMAC (43) for wild-type or D101L HDAC8, respectively, and models were fit into electron density maps using COOT (44). Bijvoet difference Fourier maps were generated using CNS (42). At the conclusion of refinement, residues M1-S13 at the N-terminus and 7–9 residues between E85–E95 appeared to be disordered in all monomers and were excluded from each final model. Data collection and refinement statistics are recorded in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Structure | Wild-type Co2+-HDAC8-M334 complex | D101L Co2+-HDAC8-M334 complex | D101L Fe2+-HDAC8-M334 complex | D101L Mn2+-HDAC8-M334 complex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution limits, Å | 50 – 3.2 | 50 – 1.9 | 50 – 2.0 | 50 – 1.85 |

| Energy/wavelength (eV/Å) | 7725/1.6050 | 11,566/1.0720 | 11,566/1.0720 | 12,660/0.9793 |

| Space group | P21 | P21212 | P21212 | P212121 |

| Total/unique reflections | 28,240/14,687 | 63,065/33,586 | 53,795/28,881 | 137,178/72,518 |

| Completeness (%) (overall/outer shell) | 98.3/90.9 | 97.5/85.4 | 98.7/90.5 | 99.0/98.0 |

| Rmergea (overall/outer shell) | 0.132/0.441 | 0.049/0.492 | 0.064/0.254 | 0.099/0.406 |

| I/σ(I) (overall/outer shell) | 9.9/2.3 | 38/2.4 | 28.1/5.2 | 19.2/4.1 |

| No. of reflections (work set/test set) | 12,996/684 | 28,790/1,576 | 25,924/1,457 | 54,828/6,936 |

| R/Rfreeb | 0.204/0.256 | 0.220/0.256 | 0.202/0.247 | 0.201/0.249 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.012 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

Rmerge = Σ|I−〈I〉|/Σ|I|, where I is the observed intensity and 〈I〉 is the average intensity calculated for replicate data.

Crystallographic R factor, R = Σ||Fo|−|Fc||/Σ|Fo|, for reflections contained in the working set. Free R factor, Rfree = Σ||Fo|−|Fc||/Σ|Fo|, for reflections contained in the test set excluded from refinement. |Fo| and |Fc| are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Table 2.

Anomalous scattering data collection statistics

| Structure | D101L Co2+-HDAC8-M334 complex | D101L Fe2+-HDAC8-M334 complex | D101L Mn2+-HDAC8-M334 complex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution limits, Å | 50 – 2.7 | 50 – 3.0 | 35 – 2.7 |

| Energy/wavelength (eV/Å) | 7725/1.6050 | 7120/1.7143 | 8048/1.5406 |

| Space Group | P21212 | P21212 | P212121 |

| Total/unique reflections | 21,310/11,556 | 19,561/10,633 | 42,388/22,990 |

| Completeness (%) (overall/outer shell) | 99.9/100.0 | 98.5/89.1 | 95.7/97.8 |

| Redundancy (overall/outer shell) | 8.4/8.3 | 8.2/4.8 | 6.5/6.4 |

| Rmergea (overall/outer shell) | 0.162/0.567 | 0.129/0.230 | 0.126/0.461 |

| I/σ(I) (overall/outer shell) | 13.0/5.2 | 15.7/4.8 | 11.2/4.4 |

Rmerge = Σ|I−〈I〉|/Σ|I|, where I is the observed intensity and 〈I〉 is the average intensity calculated for replicate data.

Crystallographic R factor, R = Σ||Fo|−|Fc||/Σ|Fo|, for reflections contained in the working set. Free R factor, Rfree = Σ||Fo|−|Fc||/Σ|Fo|, for reflections contained in the test set excluded from refinement. |Fo| and |Fc| are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Metal affinity measurements

The affinity of HDAC8 for Zn2+ and Fe2+ was measured from an increase in activity in the presence of increasing concentrations of free Zn2+ or Fe2+ maintained using a metal buffer in an anaerobic glove box. The standard assay buffer was replaced with 1 mM nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA), 147 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 5 mM MOPS (pH 7) (45, 46) with [Fe]total = 0–950 μM ([Fe2+]free 0–2.6 μM) or [Zn2+]total = 0–200 μM ([Zn2+]free 0–532 pM) and 0.4 μM HDAC8. The concentration of bound versus free metal ion was calculated using the program MINEQL+ (Environmental Research Software). The assay mixtures, containing all components except substrate, were incubated for 4 hours on ice in the anaerobic glove box. Assays were incubated at 30°C for 30 min, initiated by the addition of substrate (50 μM final), and the products analyzed as described above. The activity is dependent on the concentration of [Me2+]free and not the total concentration of the metal ion and buffer. The metal dissociation constant (KMe) was determined from fitting a binding isotherm (Eq. 1) to the activity versus [Me2+]free data using the program KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software) where A is the activity at saturating metal ion.

| Eq. 1 |

Results

Metal Affinity Studies

Essentially complete metal ion substitution of HDAC8 with Co2+, Fe2+, Mn2+, or Cu2+ is confirmed by the ICP mass spectrometry data recorded in Table 3. HDAC8 shows no significant incorporation of Fe3+ or Ni2+ under the conditions tested. As initially prepared aerobically, the recombinant enzyme expressed in the presence of 100 μM ZnCl2 contains predominantly Zn2+, confirming that Zn2+ is bound in the active sites of HDAC8 structures published to date (23, 24, 36, 47).

Table 3.

Metal Ion Content of Metallosubstituted HDAC8

| Molar ratio of metal:proteina,b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Mn | |

| Native HDAC8c | 0.06 | —d | — | 0.13 | 0.87 | NDe |

| Co2+-HDAC8 | 0.02 | 1.1 | — | 0.01 | 0.02 | ND |

| Fe2+-HDAC8 | 0.79 | 0.08 | — | 0.08 | 0.05 | ND |

| Fe2+-D101L HDAC8 | 1.4 | — | — | 0.07 | 0.05 | ND |

| Fe3+-HDAC8 | 0.12 | — | — | 0.02 | 0.05 | — |

| Fe3+-D101L HDAC8 | — | — | — | 0.06 | 0.08 | — |

| Mn2+-HDAC8 | 0.02 | — | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 1.1 |

| Mn2+-D101L HDAC8 | — | 0.05 | — | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.98 |

| Cu2+-HDAC8 | 0.01 | — | — | 1.09 | 0.14 | ND |

| Ni2+-HDAC8 | ND | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.13 | — |

Metallosubstituted HDAC8 was generated as described in the Materials and Methods. Metal-free enzyme was generated by dialyzing with EDTA. Each metal ion was subsequently introduced at a concentration of 100 μM chloride salt and dialyzed to a final concentration of 100 nM. Metal ion content of final protein samples was determined by ICP mass spectrometry.

The ratios of metal ion to protein was determined by dividing the metal ion concentration, as determined by ICP mass spectrometry, by the protein concentration, as determined by Bradford assay.

Native HDAC8 refers to recombinant protein expressed in E. coli with 100 μM ZnCl2.

“—” signifies a value of less than 0.01.

ND signifies not determined.

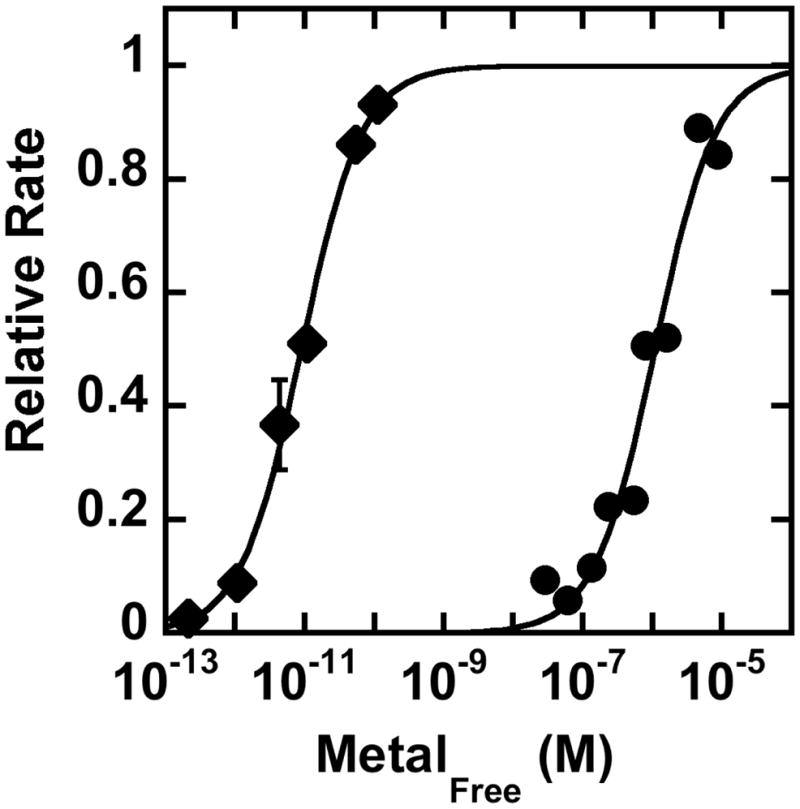

Of the transition metals that activate HDAC8, Fe2+ and Zn2+ exist in high amounts in the cell, with total concentrations around 0.1 – 0.2 mM in eukaryotes and E. coli (48–50). Thus, these metal ions are the most likely native cofactors. The affinity of HDAC8 for Zn2+ and Fe2+ was measured from the metal-dependent activation of catalytic activity with the free metal concentration maintained using a metal buffer (Figure 2). HDAC8 has significantly higher affinity for Zn2+ (KD = 9 ± 1 pM) than Fe2+ (KD = 1.1 ± 0.3 μM), consistent with the higher Lewis acidity of Zn2+ (51, 52). At first glance, this disparity suggests that HDAC8 should be a Zn2+-dependent enzyme. However, previous measurements in living cells indicate that the readily exchangeable concentration of Zn2+ ([Zn2+]free ~ 10 – 400 pM (53, 54)) is also orders of magnitude lower than the readily exchangeable concentration of Fe2+ ([Fe2+free] ~ 0.2 – 6 μM) (55–57). The similarities between the metal affinities of HDAC8 and the readily exchangeable metal concentrations in cells suggest that HDAC8 is thermodynamically poised to be activated by either or both Zn2+ and Fe2+ in vivo. The metal content of HDAC8 affects both the catalytic activity and the inhibitor affinity in vitro (27). Therefore, altering the metal cofactor in vivo will affect the catalytic efficiency and, possibly, the affinity and selectivity toward acetylated substrates.

Figure 2.

Metal affinity of HDAC8. The activity of HDAC8 was assayed in the presence of increasing concentrations of free Zn2+ (diamonds) or Fe2+ (circles) using a metal buffer, as described in Materials and Methods. The relative initial velocity (vobs/vmax) is plotted to simplify the graph. Under these conditions the activity of Fe2+-HDAC8 is 2.8-fold higher than that of Zn2+-HDAC8 (27). The metal dissociation constant was determined from fitting a single binding isotherm (Eq. 1) to these data.

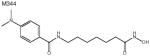

Finally, inhibition of HDAC8 by M344 was tested. The inhibition constant (Ki) is metal ion-dependent, and inhibition data are reported in Table 4. The inhibitory potency of M344 against metal-substituted HDAC8 enzymes is greatest with Co2+-HDAC8 as compared to Fe2+-HDAC8 and Zn2+-HDAC8. A comparable metal-dependent affinity trend was previously reported for the inhibitor SAHA (27). This is consistent with the same functional group used by SAHA for metal coordination, a hydroxamate that forms a 5-membered ring chelate complex.

Table 4.

Metal Ion Dependence of HDAC8 Inhibition

| Inhibitor |

Ki (nM) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Co2+ | Fe2+ | Zn2+ | |

|

14.8 ± 0.8 | 63 ± 2 | 68 ± 6 |

| 44 ± 15 | 130 ± 40 | 250 ± 25 | |

Reference (27).

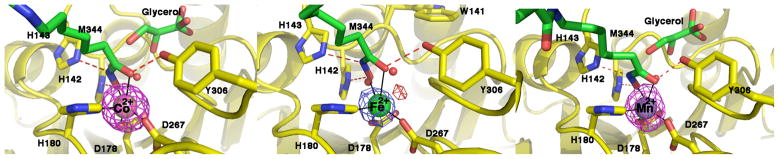

Crystal Structures

To confirm metal binding in the crystal structures, X-ray diffraction data for wild-type and D101L HDAC8 enzymes were collected at incident wavelengths near the absorption edges of cobalt or iron. A strong peak in the Bijvoet difference Fourier map of the active site in each structure corresponds to a metal ion coordinated by D178, H180, and D267 (Figures 3 and 4). Considering that the absorption edges of cobalt or iron (7.7089 keV or 7.1120 keV, respectively) and the copper Kα (8.048 keV) are significantly lower than the absorption edge of zinc (9.6586 keV), the Bijvoet difference Fourier peaks confirm the binding of Co2+, Fe2+, or Mn2+ (Figure 4). These crystallographic results are consistent with the metal ion content of these protein samples determined in solution (Table 3). Refined metal ion coordination geometries and distances in the Co2+, Fe2+, and Mn2+-substituted enzymes are comparable to those observed in Zn2+-HDAC8 (Table 5).

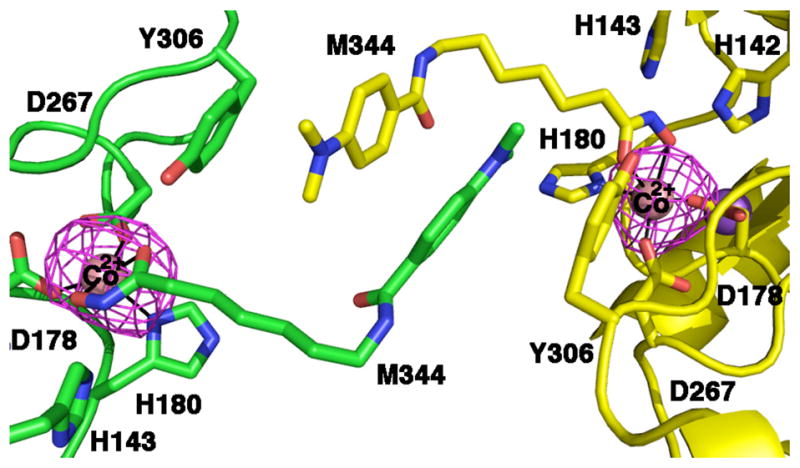

Figure 3.

Bijvoet difference Fourier map of the wild-type human Co2+-HDAC8-M344 complex calculated with X-ray diffraction data collected near the cobalt edge (7.725 keV) demonstrating the binding of Co2+ (contoured at 3σ). The enzyme packs as a crystallographic dimer with two molecules in the asymmetric unit; selected active site residues are indicated.

Figure 4.

Bijvoet difference Fourier maps of the D101L Co2+-, Fe2+-, and Mn2+-HDAC8-M344 complexes (left to right, respectively), calculated with X-ray diffraction data collected at the cobalt edge (7.725 keV), iron edge (7.120 keV), and the copper Kα (8.048 keV) demonstrating the binding of Co2+, Fe2+, and Mn2+, respectively (contoured at 9σ, 4σ, and 4σ, respectively). Anomalous data collected using copper Kα radiation can include signal from Co2+, Fe2+, or Mn2+, but excludes Zn2+. In the Fe2+-substituted enzyme, uninterpretable difference density is evident (red peak, contoured at 3σ) and may reflect incomplete changes in the metal coordination polyhedron. Protein atoms are color coded as follows: carbon (protein, yellow; ligands, green), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue). Water molecules are represented as red spheres.

Table 5.

Average Metal Ion Coordination Distances (Å) in D101L HDAC8

| Catalytic Metal Ion | D178 | D267 | H180 | W1b | W2b | Hydroxamate (N–O, C=O) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co2+ | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 1.8, 2.4 |

| Fe2+ | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.9, 2.6 |

| Mn2+ | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.2, 2.4 |

| Zn2+ a | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.5, 2.3 |

Reference (36).

W1 is the water molecule that is closest to the binding site of the hydroxamate OH group, and W2 is the water molecule that is closest to the binding site of the hydroxamate C=O group.

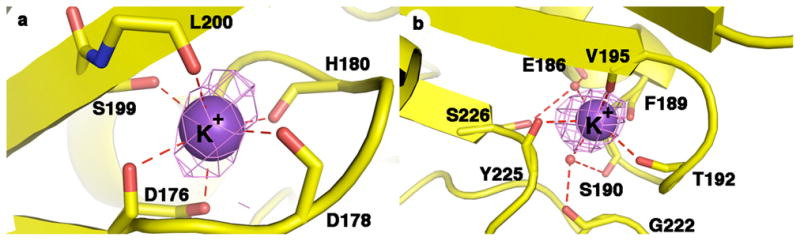

Strong peaks in the Bijvoet difference Fourier maps are also observed at the sites corresponding to two previously reported monovalent cation binding sites (Figure 5) (21, 23, 24). Metal coordination distances average ~2.8–2.9 Å and are consistent with the binding of K+ ions (absorption edge = 3.6074 eV), as previously reported (24).

Figure 5.

Bijvoet difference Fourier maps (contoured at 3σ) of K+ ions bound in the two monovalent cation binding sites in the D101L Fe2+-HDAC8-M344 complex. (a) Monovalent cation binding site adjacent to the active site. Metal ligands are color-coded as follows: carbon (yellow), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue). (b). Distal monovalent cation binding site. Atoms are color-coded as in (a), and water molecules are represented as red spheres.

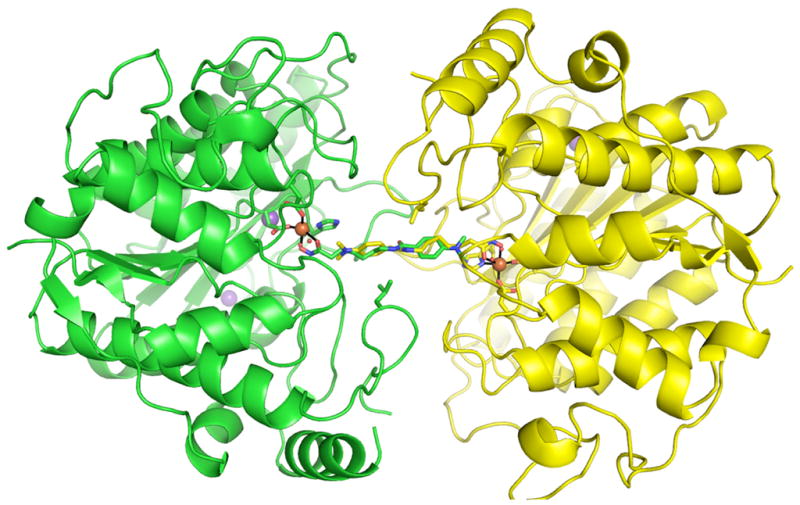

In the structure of D101L Zn2+-HDAC8 (36), a crystallographic dimer forms such that inhibitor binding in one monomer precludes inhibitor binding in the symmetry related molecule (Figure 6), resulting in 50% inhibitor occupancy in each active site. Accordingly, there is also electron density consistent with 50% occupancy of two zinc-bound solvent molecules. Similar inhibitor binding and metal coordination interactions are observed in the structures of D101L Co2+- or Fe2+-HDAC8 (Figure 7), indicating that Zn2+, Co2+, and Fe2+ are each pentacoordinate with square pyramidal geometry in the unliganded form of the enzyme. Smeared electron density is observed for the catalytic water molecule (W1) in the D101L Co2+-HDAC8 complex (data not shown), which is satisfactorily fit with a single solvent molecule that refines to a position 2.8 Å away from the Co2+ ion with 25% occupancy. In the Fe2+-substituted enzyme, a small 3.5σ electron density peak is seen ~1.5 Å from the Fe2+ center and is located close (~ 1.9 Å) to the metal-bound solvent molecules (Figure 4). This peak does not refine satisfactorily as a water molecule with full or partial occupancy, so we have not built anything into this density in the final model. Interestingly, D101L Mn2+-HDAC8 crystallizes in space group P212121 with two molecules in the asymmetric unit. The crystallographic symmetry formerly observed in the D101L Zn2+-, Co2+-, and Fe2+-HDAC8 structures is broken due to unequal inhibitor occupancy in the two D101L Mn2+-HDAC8 monomers in the asymmetric unit (30% in monomer A and 70% in monomer B). Electron density for two metal-bound solvent molecules is clearly visible only in monomer A with occupancy = 0.7. Both D101L Co2+- and Mn2+-HDAC8 reveal electron density adjacent to the active site which is best fit with a disordered glycerol molecule, as previously observed in D101L Zn2+-HDAC8 (36). D101L Fe2+-HDAC8 reveals electron density for two alternate conformations of W141.

Figure 6.

The crystallographic dimer of the D101L Fe2+-HDAC8-M344 complex. Monomer A and monomer B are shown in green and yellow, respectively. Fe2+-coordinating residues and L101 are shown as sticks. Protein atoms are color coded as follows: carbon (green or yellow), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue). Ions are colored as follows: Fe2+ (orange), K+ (purple). Inhibitor M344 atoms are colored as follows: carbon (green or yellow), nitrogen (blue), oxygen (red).

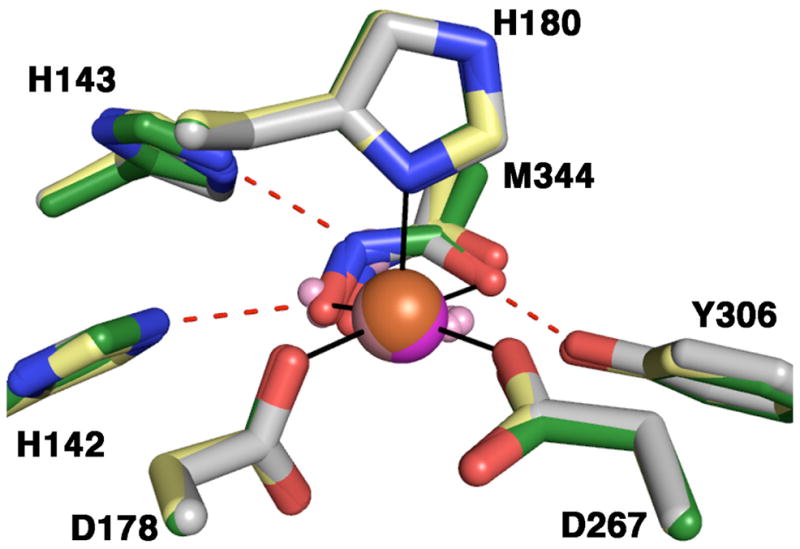

Figure 7.

Square-pyramidal Co2+, Fe2+, and Mn2+ coordination polyhedra in the liganded and unliganded forms of D101L HDAC8 complexed with M344. Atoms are color coded as follows: carbon = yellow for Fe2+ structure, grey for Co2+ structure, and green for Mn2+ structure, nitrogen = blue, oxygen = red, Fe2+ = orange sphere, Co2+ = pink sphere, Mn2+ = magenta sphere, H2O = pink spheres. Metal coordination and hydrogen bond interactions involving the inhibitor hydroxamate group are shown in solid black and dotted red lines, respectively.

Discussion

Hydrolytic metalloenzymes can exhibit a wide range of catalytic activities when substituted with different transition metal ions. Here, it is instructive to compare metal ion-activity relationships in three enzymes that share the α/β arginase fold: arginase, HDAC8, and acetylpolyamine amidohydrolase (APAH). Carvajal and colleagues demonstrate that maximal human arginase I activity results from the binding of two Mn2+ ions, and the enzyme exhibits minimal activity levels with Ni2+ and Co2+; the KM value does not significantly change with different metal ions (58) (in contrast, Stone and colleagues report that Co2+-substituted human arginase I exhibits significantly higher catalytic activity (59)). The APAH from M. ramosa exhibits a similar preference for Mn2+, with the general metal ion-activity trend Mn2+ > Co2+ > Zn2+ > Mg2+ > Cu2+ > Ca2+, but individual kinetic constants are not reported (60). In contrast, the HDAC enzymes were initially thought to be zinc metallohydrolases based on studies of the histone deacetylase-like protein from A. aeolicus (21), but HDAC8 exhibits the metal ion-activity dependence Co2+ > Fe2+ > Zn2+ > Ni2+ > Mn2+ based on kcat/KM values (27). While the kcat value measured for HDAC8 is less sensitive to the identity of the divalent metal ion, the KM values for Co2+-HDAC8 and Fe2+-HDAC8 are 160 μM and 210 μM, respectively, in comparison with that of 1100 μM measured for Zn2+-HDAC8 (27); the low values of kcat/KM combined with the high value of KM for the coumarin-labeled peptide substrates suggest that KM likely reflects the substrate dissociation constant. Consistent with this, the enhanced activity of HDAC8 with fluorinated acetyl-L-lysine substrates suggests that deacetylation is the rate-limiting step for kcat (61, 62). Additionally, the Ki values measured for the hydroxamate inhibitors SAHA (Vorinostat) and M344 indicate the preference Co2+ > Fe2+ ≈ Zn2+ (Table 4) (27). These data implicate a substrate-metal ion coordination interaction in the precatalytic Michaelis complex; moreover, as first noted by Fierke and colleagues, these data suggest that HDAC8 may be a Fe2+-metalloenzyme in vivo, given the greater biological abundance of this metal ion (27).

However, the affinity of HDAC8 for Zn2+ is ~106-fold higher than Fe2+ affinity (Figure 2), which combined with the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ explains the purification of HDAC8 with bound zinc. A preference for Zn2+ binding is predicted by the increased Lewis acidity of Zn2+ compared to Fe2+ and is also in accord with the Irving-Williams series of stability constants (51, 52). Nonetheless, it remains a possibility that HDAC8 binds either Fe2+ or Zn2+ in vivo since the current data indicate that intracellular concentrations of readily exchangeable Zn2+ are several orders of magnitude lower than readily exchangeable Fe2+ (5–400 pM vs. 0.2–6 μM) (53–57). Assuming that metal selectivity is determined mainly based on thermodynamics, a competitive binding equation (Equation 2) can be used to predict the fractional bound Zn2+ and Fe2+ at a given concentration of free Zn2+ and Fe2+. These calculations demonstrate that in the expected physiological range of metal ion concentrations (10 – 400 pM [Zn]free, 0.2 – 0.6 μM [Fe]free), HDAC8 could either bind mainly Zn2+ (97% Zn/0.4% Fe) or Fe2+ (8% Zn/77% Fe), depending on the ratio of exchangeable Fe2+/Zn2+ in the cell. Therefore, HDAC8 could be activated by either or both metal ions in vivo and, possibly, metal ion composition could vary depending on cellular conditions. However, the determinants of Fe2+/Zn2+ metal selectivity in eukaryotic cells is currently unclear, and could be facilitated by metallochaperones, or kinetic control, rather than thermodynamics (63). To date, no zinc-specific metallochaperones have been identified, although several potential iron-specific metallochaperones are being investigated for roles in iron homeostasis, particularly in the assembly of Fe-S clusters (63–65). Therefore, direct measurement of metal-bound HDAC8 in vivo will be required to definitively identify the native cofactor and to determine whether the metal content is variable.

| Eq. 2 |

Intracellular metal ion homeostasis can be important for regulating metal binding to metalloenzymes. The eukaryotic Mn-dependent superoxide dismutase (SOD2) specifically acquires Mn in S. cerevisiae but is inactive when Fe is bound. Deletion of a specific transporter, Mtm1p, results in elevated mitochondrial iron concentrations and an inactive Fe-SOD2 in vivo (66). It is also likely that metal ion binding to other metalloenzymes, such as HDAC8, is sensitive to intracellular homeostasis (reviewed in (63)).

Metal ions in metalloenzymes can affect enzyme function by maintaining the structure of the active site and providing coordination interactions for substrate, transition state(s), and intermediate(s) that facilitate catalysis. In the active site of arginase, MnA2+ is bound with square pyramidal geometry by four protein ligands (Asp3His) and MnB2+ is bound with octahedral geometry by four protein ligands (Asp3His); one aspartate, D234, serves as a bidentate ligand (20). Two aspartates and one hydroxide ion serve as bridging ligands. The MnB2+ site of arginase corresponds to the single metal binding site of HDAC enzymes (67, 68). In HDAC8 substituted with Zn2+, Co2+, and Fe2+, the divalent metal ion is coordinated by three protein ligands (Asp2His) and two water molecules with square pyramidal geometry. Inspection of the HDAC8 active site suggests that D267, which corresponds to D234 of arginase, cannot achieve a bidentate coordination geometry to yield an octahedral coordination polyhedron. Interestingly, one of the monovalent cation binding sites in HDAC8 includes the backbone C=O groups of two of the three divalent metal ion coordination residues (H180 and D178) (Figure 5), and potassium binding to this site inhibits catalytic activity (69). It appears that HDAC8 has evolved to favor square planar metal coordination where the substrate C=O group displaces one of the metal-bound water molecules and coordinates to an equatorial site in the precatalytic Michaelis complex. No significant changes are observed between the crystal structures of wild type Zn2+- and Co2+-HDAC8 (r.m.s. deviation = 0.40 for 331 Cα atoms) or D101L Co2+, Fe2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+-HDAC8 bound with M344 (approximate r.m.s. deviations = 0.15 Å for 335 Cα atoms). The visible absorption spectra of Co2+-HDAC8 with and without inhibitor trichostatin A reveal no significant differences, consistent with similar Co2+ coordination geometries between the unliganded and liganded states (70). It is notable that square planar metal coordination geometry is also shared by the bacterial deacetylase UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase (LpxC), which has an AspHis2 ligand set for Zn2+ coordination and an α+β fold unrelated to the α/β fold of HDAC8 (71, 72).

In contrast to substrate binding in HDAC8, the guanidinium group of L-arginine does not coordinate to the metal ions in the precatalytic enzyme-substrate complex with Mn2+2-arginase, as indicated by the lack of metal dependence of KM values (which reflect substrate binding affinity) (58, 73). The KM value is similarly invariant upon mutation of Mn2+ ligands, which alters metal ion occupancy and stoichiometry in the binuclear manganese cluster (74). Stability constants for metal ion chelation by ethylenediamine ligands are ranked Mn2+ < Fe2+ < Co2+, Zn2+ < Ni2+, consistent with less favorable guanidino-Mn2+ interactions (75). It would seem that in a system where a precatalytic substrate-metal coordination interaction is not important, the metal ion with the smaller stability constant is favored. In contrast, in the HDAC enzymes where a precatalytic C=O···metal coordination interaction is important, metal ions with larger stability constants are favored (for reference, acetylacetone binding constants rank in the order Mn2+ < Zn2+ < Co2+; Fe2+ data not currently available (75)). Moreover, the substitution of one metal ion for another could alter the mechanism of catalysis with regard to precatalytic substrate-metal interactions. For example, a decrease in KM has recently been observed for Co2+2-human arginase I, suggesting that metals with greater stability constants could favor guanidino-metal coordination in the precatalytic enzyme-substrate complex (59). In the bacterial deacetylase LpxC, metal substitution affects the value of kcat rather than KM with a metal reactivity trend that is similar to HDAC8 (Mn2+ < Zn2+ < Fe2+ < Co2+) (35, 76). In this case, it is possible that the C=O···metal coordination interaction occurs in the transition state rather than the ground state. Given that LpxC and HDAC8 adopt unrelated protein folds, it is reasonable to expect structure-function differences between these two metalloamidases.

In conclusion, the ability of divalent metal ions to adopt specific geometries generally is vital for proper enzyme function, and enzymes utilize specific ligand sets to select for desired metal cofactors. The ligand set of HDAC8 (Asp2His) is unusual for Zn2+ binding within the greater family of zinc enzymes (77, 78). While HDAC enzymes are thought to be Zn2+-hydrolases, it is intriguing that greater catalytic efficiencies result with Co2+ or Fe2+ substitution in HDAC8 (27). Here, metal reconstitution experiments in solution and in the crystal confirm stoichiometric binding of these divalent metal ions and reveal conservation of square pyramidal metal coordination geometry regardless of the specific metal ion bound. Metal affinity measurements show that HDAC8 binds Zn2+ approximately 106-fold more tightly than Fe2+; however, since concentrations of readily exchangeable Zn2+ are considerably lower than Fe2+ (5 – 400 pM vs. 0.2 – 6 μM) (53–57), HDAC8 may be activated in vivo by either or both of these metals depending on cellular concentrations. Because metallochaperones may influence metal trafficking in vivo, further analysis of endogenous HDAC8 is warranted to confirm metal ion preference in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work is based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines of the Advanced Photon Source, which is supported by award RR-15301 from the National Center for Research Resources at the National Institutes of Health, and beamline X25 of the National Synchrotron Light Source, which is supported principally from the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy, and from the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- APAH

acetylpolyamine amidohydrolase

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HDLP

histone deacetylase-like protein

- ICP

inductively coupled plasma

- M344

4-(dimethylamino)-N-[7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl]-benzamide

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- NTA

nitrilotriacetic acid

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants GM49758 (D.W.C.) and GM40602 (C.A.F.).

The atomic coordinates of the wild-type Co2+-HDAC8-M344 complex, the D101L Co2+-HDAC8-M344 complex, the D101L Fe2+-HDAC8-M344 complex, and the D101L Mn2+-HDAC8-M344 complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) with accession codes 3MZ3, 3MZ7, 3MZ6, and 3MZ4, respectively.

References

- 1.Walsh CT. Posttranslational modification of proteins: expanding nature’s inventory. Roberts and Company Publishers; Englewood, CO: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seo J, Lee KJ. Post-translational modifications and their biological functions: proteomic analysis and systematic approaches. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;37:35–44. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2004.37.1.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos-Rosa H, Caldas C. Chromatin modifier enzymes, the histone code and cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2381–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lennartsson A, Ekwall K. Histone modification patterns and epigenetic codes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:863–868. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi JK, Howe LJ. Histone acetylation: truth of consequences? Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:139–150. doi: 10.1139/O08-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mujtaba S, Zeng L, Zhou MM. Structure and acetyl-lysine recognition of the bromodomain. Oncogene. 2007;26:5521–5527. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhalluin C, Carlson JE, Zeng L, He C, Aggarwal AK, Zhou MM. Structure and ligand of a histone acetyltransferase bromodomain. Nature. 1999;399:491–496. doi: 10.1038/20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez R, Zhou MM. The role of human bromodomains in chromatin biology and gene transcription. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:659–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan DW, Wang Y, Wu M, Wong J, Qin J, Zhao Y. Unbiased proteomic screen for binding proteins to modified lysines on histone H3. Proteomics. 2009;9:2343–2354. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Shogren-Knaak MA. The Gcn5 bromodomain of the SAGA complex facilitates cooperative and cross-tail acetylation of nucleosomes. J Biol Chem. 2008;284:9411–9417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregoretti IV, Lee YM, Goodson HV. Molecular evolution of the histone deacetylase family: functional implications of phylogenetic analysis. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taunton J, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. A mammalian histone deacetylase related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Rpd3p. Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin HY, Chen CS, Lin SP, Weng JR, Chen CS. Targeting histone deacetylase in cancer therapy. Med Res Rev. 2006;26:397–413. doi: 10.1002/med.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang WM, Tsai SC, Wen YD, Fejér G, Seto E. Functional domains of histone deacetylase-3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9447–9454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu E, Chen Z, Fredrickson T, Zhu Y, Kirkpatrick R, Zhang GF, Johanson K, Sung CM, Liu R, Winkler J. Cloning and characterization of a novel human class I histone deacetylase that functions as a transcription repressor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15254–15264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908988199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waltregny D, de Leval L, Glénisson W, Ly Tran S, North BJ, Bellahcène A, Weidle U, Verdin E, Castronovo V. Expression of histone deacetylase 8, a class I histone deacetylase, is restricted to cells showing smooth muscle differentiation in normal human tissues. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:553–564. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin M, Kettmann R, Dequiedt F. Class IIa histone deacetylases: regulating the regulators. Oncogene. 2007;26:5450–5467. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanyo ZF, Scolnick LR, Ash DE, Christianson DW. Structure of a unique binuclear manganese cluster in arginase. Nature. 1996;383:554–557. doi: 10.1038/383554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finnin MS, Donigian JR, Cohen A, Richon VM, Rifkind RA, Marks PA, Breslow R, Pavletich NP. Structures of a histone deacetylase homologue bound to the TSA and SAHA inhibitors. Nature. 1999;401:188–193. doi: 10.1038/43710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen TK, Hildmann C, Dickmanns A, Schwienhorst A, Ficner R. Crystal structure of a bacterial class 2 histone deacetylase homologue. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somoza JR, Skene RJ, Katz BA, Mol C, Ho JD, Jennings AJ, Luong C, Arvai A, Buggy JJ, Chi E, Tang J, Sang BC, Verner E, Wynands R, Leahy EM, Dougan DR, Snell G, Navre M, Knuth MW, Swanson RV, McRee DE, Tari LW. Structural snapshots of human HDAC8 provide insights into the class I histone deacetylases. Structure. 2004;12:1325–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vannini A, Volpari C, Filocamo G, Casavola EC, Brunetti M, Renzoni D, Chakravarty P, Paolini C, De Francesco R, Gallinari P, Steinkühler C, Di Marco S. Crystal structure of a eukaryotic zinc-dependent histone deacetylase, human HDAC8, complexed with a hydroxamic acid inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15064–15069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404603101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bottomley MJ, Lo Surdo P, Di Giovine P, Cirillo A, Scarpelli R, Ferrigno F, Jones P, Neddermann P, De Francesco R, Steinkühler C, Gallinari P, Carfi A. Structural and functional analysis of the human HDAC4 catalytic domain reveals a regulatory structural zinc-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26694–26704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803514200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuetz A, Min J, Allali-Hassani A, Schapira M, Shuen M, Loppnau P, Mazitschek R, Kwiatkowski NP, Lewis TA, Maglathin RL, McLean TH, Bochkarev A, Plotnikov AN, Vedadi M, Arrowsmith CH. Human HDAC7 harbors a class IIa histone deacetylase-specific zinc binding motif and cryptic deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11355–11363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707362200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gantt SL, Gattis SG, Fierke CA. Catalytic activity and inhibition of human histone deacetylase 8 is dependent on the identity of the active site metal ion. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6170–6178. doi: 10.1021/bi060212u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tripp BC, Bell CB, III, Cruz F, Krebs C, Ferry JG. A role for iron in an ancient carbonic anhydrase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6683–6687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seffernick JL, McTavish H, Osborne JP, de Souza ML, Sadowsky MJ, Wackett LP. Atrazine chlorohydrolase from Pseudomonas Sp. strain ADP is a metalloenzyme. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14430–14437. doi: 10.1021/bi020415s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu J, Dizin E, Hu X, Wavreille AS, Park J, Pei D. S-Ribosylhomocysteinase (LuxS) is a mononuclear iron protein. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4717–4726. doi: 10.1021/bi034289j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’souza VM, Holz RC. The methionyl aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli can function as an iron(II) enzyme. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11079–11085. doi: 10.1021/bi990872h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajagopalan PTR, Grimme S, Pei D. Characterization of cobalt(II)-substituted peptide deformylase: function of the metal ion and the catalytic residue glu-133. Biochemistry. 2000;39:779–790. doi: 10.1021/bi9919899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Copik AJ, Waterson S, Swierczek SI, Bennett B, Holz RC. Both nucleophile and substrate bind to the catalytic Fe(II)-center in the type-II methionyl aminopeptidase from Pyrococcus furiousus. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:1160–1162. doi: 10.1021/ic0487934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porter DJT, Austin EA. Cytosine deaminase. The roles of divalent metal ions in catalysis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24005–24011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernick M, Gattis SG, Penner-Hahn JE, Fierke CA. Activation of Escherichia coli UDP-3-O-[(R)-3-hydroxymyristoyl]-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase by Fe2+ yields a more efficient enzyme with altered ligand affinity. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2246–2255. doi: 10.1021/bi902066t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dowling DP, Gantt SL, Gattis SG, Fierke CA, Christianson DW. Structural studies of human histone deacetylase 8 and its site-specific variants complexed with substrate and inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13554–13563. doi: 10.1021/bi801610c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jung M, Brosch G, Kölle D, Scherf H, Gerhäuser C, Loidl P. Amide analogues of trichostatin A as inhibitors of histone deacetylase and inducers of terminal cell differentiation. J Med Chem. 1999;42:4669–4679. doi: 10.1021/jm991091h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, Delano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCall KA, Fierke CA. Probing determinants of the metal ion selectivity in carbonic anhydrase using mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3979–3986. doi: 10.1021/bi0498914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCall KA, Fierke CA. Colorimetric and fluorimetric assays to quantitate micromolar concentrations of transition metals. Anal Biochem. 2000;284:307–315. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vannini A, Volpari C, Gallinari P, Jones P, Mattu M, Carfi A, De Francesco R, Steinkühler C, Di Marco S. Substrate binding to histone deacetylases as shown by the crystal structure of the HDAC8-substrate complex. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:879–884. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Espósito BP, Epsztejn S, Breuer W, Cabantchik ZI. A review of fluorescence methods for assessing labile iron in cells and biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 2002;304:1–18. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Outten CE, O’Halloran TV. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science. 2001;292:2488–2492. doi: 10.1126/science.1060331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vallee BL, Falchuk KH. The biochemical basis of zinc physiology. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:79–118. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lippard SJ, Berg JM. Principles of bioinorganic chemistry. XVII. Univ. Science Books; Mill Valley, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Irving JT, Williams JP. Order of stability of metal complexes. Nature. 1948;162:746–747. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bozym RA, Thompson RB, Stoddard AK, Fierke CA. Measuring picomolar intracellular exchangeable zinc in PC-12 cells using a ratiometric fluorescence biosensor. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:103–111. doi: 10.1021/cb500043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vinkenborg JL, Nicolson TJ, Bellomo EA, Koay MS, Rutter GA, Merkx M. Genetically encoded FRET sensors to monitor intracellular Zn2+ homeostasis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:737–740. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Epsztejn S, Kakhlon O, Glickstein H, Breuer W, Cabantchik ZI. Fluorescence analysis of the labile iron pool of mammalian cells. Anal Biochem. 1997;248:31–40. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacKenzie EL, Iwasaki K, Tsuji Y. Intracellular iron transport and storage: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:997–1030. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petrat F, de Groot H, Rauen U. Subcellular distribution of chelatable iron: a laser scanning microscopic study in isolated hepatocytes and liver endothelial cells. Biochem J. 2001;356:61–69. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carvajal N, Torres C, Uribe E, Salas M. Interaction of arginase with metal ions: studies of the enzyme from human liver and comparison with other arginases. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;112:153–159. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(95)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stone EM, Glazer ES, Chantranupong L, Cherukuri P, Breece RM, Tierney DL, Curley SA, Iverson BL, Georgiou G. Replacing Mn2+ with Co2+ in human arginase I enhances cytotoxicity toward L-arginine auxotrophic cancer cell lines. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:333–342. doi: 10.1021/cb900267j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sakurada K, Ohta T, Fujishiro K, Hasegawa M, Aisaka K. Acetylpolyamine amidohydrolase from Mycoplana ramosa: gene cloning and characterization of the metal-substituted enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5781–5786. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5781-5786.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riester D, Wegener D, Hildmann C, Schwienhorst A. Members of the histone deacetylase superfamily differ in substrate specificity towards small synthetic substrates. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:1116–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith BC, Denu JM. Acetyl-lysine analog peptides as mechanistic probes of protein deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37256–37265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waldron KJ, Rutherford JC, Ford D, Robinson NJ. Metalloproteins and metal sensing. Nature. 2009;460:823–830. doi: 10.1038/nature08300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mansy SS, Cowan JA. Iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis: toward an understanding of cellular machinery and molecular mechanism. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:719–725. doi: 10.1021/ar0301781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tottey S, Harvie DR, Robinson NJ. Understanding how cells allocate metals using metal sensors and metallochaperones. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:775–783. doi: 10.1021/ar0300118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang M, Cobine PA, Molik S, Naranuntarat A, Lill R, Winge DR, Culotta VC. The effects of mitochondrial iron homeostasis on cofactor specificity of superoxide dismutase 2. EMBO J. 2006;25:1775–1783. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Christianson DW. Arginase: structure, mechanism, and physiological role in male and female sexual arousal. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:191–201. doi: 10.1021/ar040183k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dowling DP, Di Costanzo L, Gennadios HA, Christianson DW. Evolution of the arginase fold and functional diversity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2039–2055. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7554-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gantt SL, Joseph CG, Fierke CA. Activation and inhibition of histone deacetylase 8 by monovalent cations. J Biol Chem. 2009;285:6036–6043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gantt SL. PhD Dissertation. University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mochalkin I, Knafels JD, Lightle S. Crystal structure of LpxC from Pseudomonas aeruginosa complexed with the potent BB-78485 inhibitor. Protein Sci. 2008;17:450–457. doi: 10.1110/ps.073324108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whittington DA, Rusche KM, Shin H, Fierke CA, Christianson DW. Crystal structure of LpxC, a zinc-dependent deacetylase essential for endotoxin biosynthsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8146–8150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432990100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carvajal N, Uribe E, Torres C. Subcellular localization, metal ion requirement and kinetic properties of arginase from the gill tissue of the bivalve Semele solida. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1994;109B:683–689. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cama E, Emig FA, Ash DE, Christianson DW. Structural and functional importance of first-shell metal ligands in the binuclear manganese cluster of arginase I. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7748–7758. doi: 10.1021/bi030074y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martell AE, Smith RM. Critical Stability Constants. 1–6. New York, NY: 1974–1989. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jackman JE, Raetz CRH, Fierke CA. UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase of Escherichia coli is a zinc metalloenzyme. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1902–1911. doi: 10.1021/bi982339s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lipscomb WN, Sträter N. Recent advances in zinc enzymology. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2375–2434. doi: 10.1021/cr950042j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hernick M, Fierke CA. Zinc hydrolases: the mechanisms of zinc-dependent deacetylases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]