Abstract

People of the Qatar peninsula represent a relatively recent founding by a small number of families from three tribes of the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, and Oman, with indications of African admixture. To assess the roles of both this founding effect and the customary first-cousin marriages among the ancestral Islamic populations in Qatar's population genetic structure, we obtained and genotyped with Affymetrix 500k SNP arrays DNA samples from 168 self-reported Qatari nationals sampled from Doha, Qatar. Principal components analysis was performed along with samples from the Human Genetic Diversity Project data set, revealing three clear clusters of genotypes whose proximity to other human population samples is consistent with Arabian origin, a more eastern or Persian origin, and individuals with African admixture. The extent of linkage disequilibrium (LD) is greater than that of African populations, and runs of homozygosity in some individuals reflect substantial consanguinity. However, the variance in runs of homozygosity is exceptionally high, and the degree of identity-by-descent sharing generally appears to be lower than expected for a population in which nearly half of marriages are between first cousins. Despite the fact that the SNPs of the Affymetrix 500k chip were ascertained with a bias toward SNPs common in Europeans, the data strongly support the notion that the Qatari population could provide a valuable resource for the mapping of genes associated with complex disorders and that tests of pairwise interactions are particularly empowered by populations with elevated LD like the Qatari.

Introduction

The population of the State of Qatar is, like many modern societies, facing a growing threat from diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Recent progress via genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has identified many additional genetic factors that appear to inflate the risk of disorders in some individuals.1–4 A drawback of the GWAS approach has been its limitation primarily to individuals of European ancestry. Validation of risk factors identified in European GWAS can be conducted in different population samples and may often produce negative results. For example, although PPARγ is associated with diabetes in some individuals of European descent, the gene was found not to be not a risk factor in a Qatari population sample.5 These results only further support the need to uncover non-European risk factors. A study of the population structure of the people of Qatar, as inferred by genetic testing, is necessary in order to determine how best to perform GWAS and other genetically assisted analyses of risk in the Qatari population.

Based on surnames and oral history, it is thought that the bulk of the Qatari population originates from the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, and Oman, with a minority descending from individuals of Africa and Southeast Asia. The people described as Arab are descendants of tribes from the Arabian Peninsula, including coastal tribes of pearl divers and the Hadar as well as Bedouin nomads. The Ajam, or Iranian Qatari, are descendants of merchants and craftsmen who migrated from Persia, and the majority of the Ajam speak Farsi. Another group, the Abd, is descended from African slaves brought from Zanzibar to Qatar via Oman.6 Qatar's complex history makes the region especially interesting in determining whether population genetic methods of analysis reveal patterns of genetic polymorphism that are consistent with the country's history.

In keeping with the customs of Islam, first-cousin marriages have been widely accepted in Qatar and may have represented about half of all marriages in the region. More recent studies indicate that the rate of first-cousin marriages has fallen to about 22% but that attitudes toward consanguinity have remained accepting.7 A high level of recurrent consanguinity would have a profound impact on the genetic structure of a population, as well as a distinct influence on the measures of population substructure. Here, we perform an analysis of high-density SNP genotyping chips on a sample of 168 individuals from the Qatar peninsula, and we attempt to reconcile the genetic information with the historical understanding of this region.

Subjects and Methods

Sample Collection and SNP Data Collection

Human subjects were recruited under ongoing protocols approved by the institutional review boards of Hamad Medical Corporation (#392/2006, #9093/09, #373/2006) and Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City (#0605008516, #0904010340, #0604008489, #0806009874). All subjects received a general medical examination, and basic demographic information and blood were collected. DNA was extracted from blood with a QIAGEN blood kit and the DNA was quality controlled, requiring an A260/A280 ratio of 1.8–2.1, quantified with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Frozen DNA, diluted to 50 ng/ml, was processed as recommended by Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 5.0. Processing involved restriction digestion, PCR amplification, purification, and labeling. Aliquots were removed during processing to ensure that the size profile and yield were within acceptable limits. After hybridization and washing, the chips were scanned and quality control was performed with select heterozygous control SNPs. The Bayesian robust linear model with Mahalanobis (BRLMM-P) algorithm was used to generate SNP calls, and additional quality control was performed for call rates, consistency with self-reported ethnicity, relatedness to other samples, and gender. Of the 168 initial subjects, we identified 156 unrelated subjects, defined as sharing less than 20% of their genome identical by descent (IBD) with any other individual as calculated via PLINK v1.06.8 Only the 156 unrelated subjects were used in the following analysis.

SNP Trimming for Population Structure Inference

PLINK was used to prune the 440,794 SNPs down to 67,735 SNPs with a minor allele frequency greater than 5%, a missingness rate less than 1%, and a Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) deviation p value of no less than 0.001. SNPs were pruned for pairwise linkage disequilibrium (r2) maximum threshold of 0.5 with PLINK's --indep-pairwise command. We used the resulting subset of SNPs for the STRUCTURE analysis.

Inference of Population Clustering by STRUCTURE

The 67,735 SNPs were used in the program STRUCTURE to infer the clustering of individuals into affinity groups that behave like panmictic populations.9 We applied this program assuming two, three, four, and five subpopulations on separate runs with 10,000 burn-in iterations and 10,000 iterations after burn-in. To determine the most likely number of subpopulations, we used the likelihood score calculated within the STRUCTURE program and the recommendations listed in the software documentation.

Selection of a Reference Sample and SNP Filtering for Remaining Analysis

In order to assess existing population structure and standard population genetic parameters, we performed several forms of analysis on the Qatari sample with the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) sample data as a reference.10 We chose the HGDP sample because the data provide genotypes from populations around the globe, allowing us to construct an informed picture of how the Qatari population sample relates to other human population samples from several geographic regions. Each data set was filtered to remove SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 5% and an overall missingness greater than 1%, because these results often indicate genotyping errors. We then filtered each Qatari group and HGDP population sample separately for HWE deviations with p value less than 0.001 in order to remove additional genotyping errors. By filtering each sample separately, we avoided eliminating SNPs deviating from HWE as a result of the Wahlund effect, thereby retaining SNPs that deviate from HWE because of existing population structure and not simply genotyping errors.11 Nonbiallelic SNPs and unmapped SNPs were also removed. Because the two samples were analyzed on different genotyping platforms, we limited analysis to the intersection of SNPs between the two platforms. However, this complication did not cause significant concern, because the intersection contained 56,972 SNPs, a figure sufficient to produce reliable results for most analyses.

Principal Components Analysis for Inference of Population Affinities

Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed with the program EIGENSTRAT.12,13 We ran PCA on the Qatari sample combined with all HGDP samples and plotted all of the samples onto the resulting principal components. To investigate the possibility of admixture, we also constructed principal components on a subset of HGDP population samples and subsequently plotted the Qatari groups onto these principal components. Although there are alternative interpretations for these PCA plots, one interpretation is that there was recent admixture within the focal population between the two ancestral populations whose points appear in clusters that flank the focal population when projected on the principal components.14 Other interpretations include genetic drift between subpopulations, but this interpretation is only considered to be likely when the ancestral populations contribute the same proportions of ancestry to each subgroup.15

Inference of Pairwise IBD Blocks

As a first-pass inference of regions of the genome within each individual that are IBD, we applied PLINK to find these regions of homozygosity. This approach identifies spans of homozygosity within single individuals that may be consistent with considerable levels of autozygosity and quantifies the range of interindividual variation in this feature.

Correlations between Genetic Ancestry and Surname Lineage

Surnames of the individuals were sorted with knowledge of the local provenance of many of the family names into bins labeled “Arab,” “African,” “Asian,” and “Persian” as well as some pairwise ambiguities. Qatar has a small population with few, and usually common, surnames, but when a name's origin was in doubt, we relied on the expertise of Qatar historians or, at last resort, marked the surname as unclassified. These coded bins were then tallied by frequency in the three Qatari subgroups that had been identified by the STRUCTURE analysis. To assess the significance of the correlation between surnames and genetic ancestry, we created two binary distance matrices, one for surname origins and another for genetic subgroups, and submitted these matrices to the R package Mantel.16

Patterns of Decay of Linkage Disequilibrium

After using the intersection of filtered SNP sets for all population samples, we measured linkage disequilibrium (LD) by using the PLINK --r2 command to estimate the correlations between each marker pair genome-wide within each sample group. The correlation between SNPs as calculated by PLINK is a measure of the correlation between genotypes, as represented by minor allele counts, rather than haplotypes, as r2 is usually portrayed. This change is purely for computational efficiency, because calculations for haplotype correlations are significantly slower than for genotype correlations and would become unwieldy genome-wide. However, these two values of r2 do not differ significantly.8 To further increase efficiency, we limited the comparisons to SNPs less than 500 Mb apart. After binning these estimates by kilobase and averaging the estimates in each bin, we compared the calculated correlations between SNP pairs and the respective distance between the SNP pairs for all population samples.

Results

Analysis of the Qatari sample reveals three distinct subpopulations that differ in proportions of ancestral populations, degree of consanguinity, runs of homozygosity, and rate of LD decay. The ancestry of the three groups corresponds well with an Arabic group, an Asian group, and an admixed African group with other population genetic features resembling their respective ancestral populations. Furthermore, the origin of each subgroup correlates well with origin of the surnames of the individuals in each group.

Inference of Population Substructure within Qatar

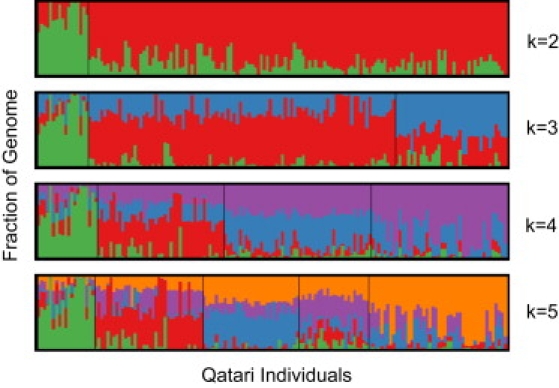

Runs of the program STRUCTURE have been widely applied to provide an unsupervised clustering of individuals into affinity groups, each of which approximates a multilocus panmictic collection of genotypes.9 In a population that is suspected of having a high level of consanguinity, we need to proceed with caution. At first we attempted to use an extension of STRUCTURE that is designed specifically for an inbred population, but this turned out to be suitable only for highly inbred, partially selfing organisms, and results were not satisfactory.17 When we used STRUCTURE, the results were quite reasonable. As is often done, we ran the program with different prior guesses at the number of subgroups, including 2, 3, 4, and 5. The results are plotted as in previous STRUCTURE analyses and appear in Figure 1.18,19 The k = 3 and k = 4 models fit best to the data with similar likelihood scores. Following parsimony and recommendations in the STRUCTURE software documentation, we took the k = 3 run and separated individuals into three groups according to the STRUCTURE clustering.

Figure 1.

STRUCTURE Results

Analysis of admixture with the program STRUCTURE assuming two, three, four, and five subpopulations. The plot represents each individual as a thin vertical column. The proportion of each color in each column indicates the proportion of an individual's genome originating from one particular (but arbitrarily colored) subpopulation. For k = 3, we arbitrarily labeled these subpopulations Qatar1 (red), Qatar2 (blue), and Qatar3 (green) and assigned each individual to a subpopulation based on plurality.

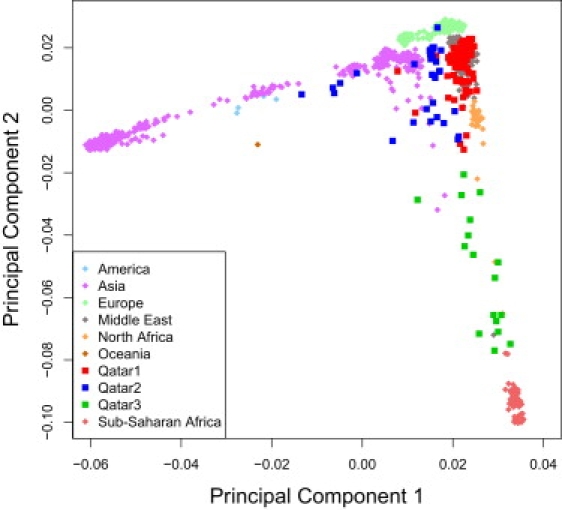

We next turned to PCA as a means of identifying not only the affinities among these three groups of Qatari individuals but their relations to other human population groups. For the latter, we used the data from the HGDP, a collection of over 1000 individuals from 52 population groups spaced across the globe.10 We first displayed the three Qatari subgroups in relation to the major human population groups (Figure 2). The three primary clusters of the Qatari are visually confirmed in the PCA plots. There is a very clear coclustering of the Qatar1 group with the Middle East group. Qatar2 tends to show a greater affinity with Asian samples, although it is much more dispersed and partially overlaps with a few of the Qatar1 individuals. Qatar3 is the most strongly African and also has the greatest dispersion, much like PCA plots of African Americans.20

Figure 2.

Principal Components Analysis of HGDP and Qatari samples

Principal components analysis plot of Qatar1, Qatar2, and Qatar3 (as defined by the STRUCTURE analysis in Figure 1) and population samples from the Human Genomic Diversity Project (HGDP). Qatar1 clusters well with other Middle Eastern samples. Qatar2 spreads away from the Middle Eastern cluster toward the Asian samples. Qatar3 spreads away from the Middle Eastern cluster toward the African samples. The interdigitation of the Qatar2 and Qatar3 samples could indicate recent admixture.

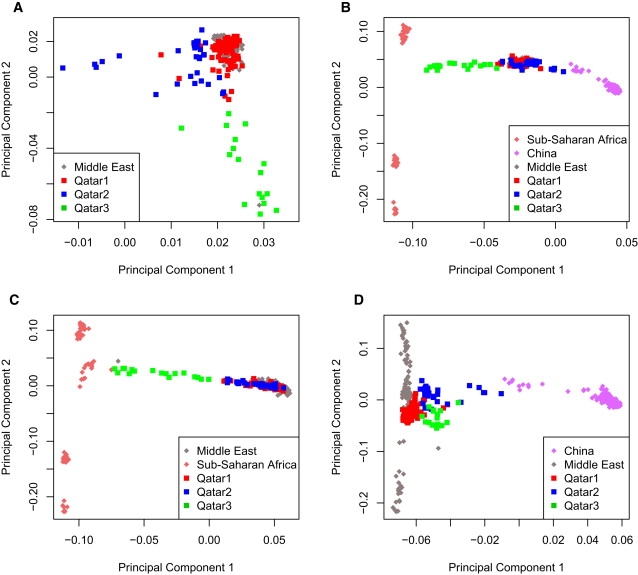

We further explored the relationships between the population samples by plotting smaller groupings of the HGDP populations and then displaying the Qatari samples with respect to the PCA loadings inferred from only the selected HGDP populations. This approach allowed us to investigate the unknown provenance of the Qatari samples with respect to the known HGDP samples as well as to observe the extent of admixture, if any, in the Qatari samples. This analysis showed again the tight clustering of the Middle East samples with the Qatar1 subgroup and the spreading of both Qatar2 and Qatar3 from this primary cluster (Figure 3A). The Qatar2 group stretches out slightly from the Middle Eastern populations to the Asian populations, whereas Qatar3 extends substantially toward African populations (Figure 3B). Figure 3C includes only the Qatari samples with Middle Eastern and African samples of HGDP and robustly shows the same result. Finally, Qatar2 has clear affinity with Asian populations, both when all of the HGDP Asian samples are included (Figure 2) and when only Chinese samples are included (Figure 3D), with the closest Asian group being the Uyghur. In sum, the impact of trade along the axis from the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean is evident in the genetic makeup of present-day Qatar.

Figure 3.

Principal Components Analysis Plots Revealing Relations to the HGDP Samples and the Extent of Qatari Subgroup Admixture

(A) Principal components were calculated based on all HGDP populations and the Qatari data. Only Qatari data and HGDP Middle Eastern samples are graphed on this plot. Qatar1 clusters well with the other Middle Eastern populations, whereas Qatar2 creates a small cluster slightly removed from Qatar1 and the other Middle Eastern samples. Qatar3 does not form a definite cluster and is far removed from the main Middle Eastern cluster.

(B) Principal components were calculated only on Chinese and sub-Saharan African population samples. Qatari groups were then graphed on the plot by using the principal components but were not used in the calculation of the principal components. The Qatar1 and Qatar2 groups cluster directly on top of the other Middle Eastern samples, which spread between the African and Asian groups. Qatar3 spreads between the Middle Eastern samples and the African samples.

(C) Principal components were calculated only on sub-Saharan African and Middle Eastern populations. Qatari groups were then plotted onto these principal components. The Qatar3 group shows possible signs of admixture between the Middle Eastern cluster and the African population, whereas the Qatar1 and Qatar2 groups cluster well with the other Middle Eastern populations.

(D) Principal components were calculated only on Chinese and Middle Eastern populations. Qatari groups were then plotted onto these principal components. The Qatar2 group shows a few individuals who demonstrate signs of admixture between the Middle Eastern samples and the Chinese samples but mostly cluster with the other Middle Easterners.

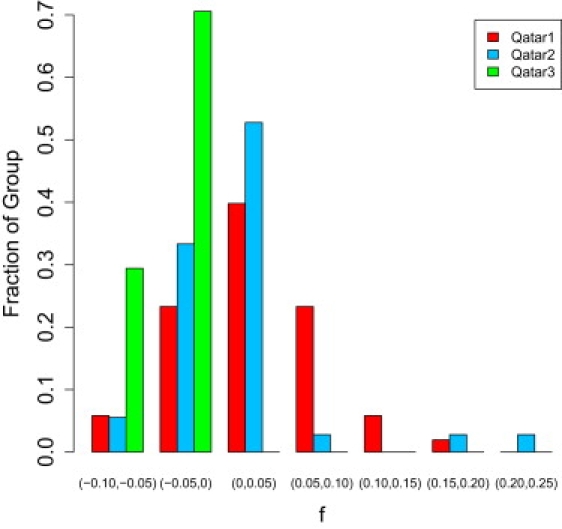

Consanguinity and Runs of Homozygosity

For each individual in the sample, we calculated Wright's inbreeding coefficient (f) from the allele frequencies in each population group and the homozygosity of the individual in question. The f coefficient calculated by PLINK is based on the number of observed and expected homozygous sites across the genome of each individual given the allele frequencies of each locus in the genome. Details on the calculation are given in the original PLINK paper.8 Calculating f permitted us to assess the distributions of the degree of inbreeding for each Qatari population subgroup (Figure 4). Qatar1 shows a distribution akin to that seen in other Arab populations, with more than 10% of the sample having an inbreeding coefficient higher than that of offspring of first cousins (f = 0.125). But even though some individuals display significant consanguinity, there are nevertheless many individuals that appear to have no signature of inbreeding at all. Qatar2 shows a much lower level of consanguinity. Surprisingly, Qatar3 has a marked tendency toward negative f values, consistent with a pattern of marriage following the trends of negative assortative mating.11 The magnitude of the negative f coefficients is surprising and exceeds that seen in African Americans.21 Applying the Wilcoxon signed-rank test as implemented in the R statistical package, the f values for the Qatar3 group are significantly skewed toward values less than 0 (p = 7.64 × 10−6).

Figure 4.

Distribution of the Degree of Consanguinity in Each Qatari Subgroup

The distributions of consanguinity are significantly different across the three Qatari subgroups. Qatar1 shows the highest degree of consanguinity, whereas every individual in Qatar3 has an unusually low level of consanguinity. Two tests of the statistical significance of differences in consanguinity among these groups were performed: Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.001; analysis of variance, p < 0.001.

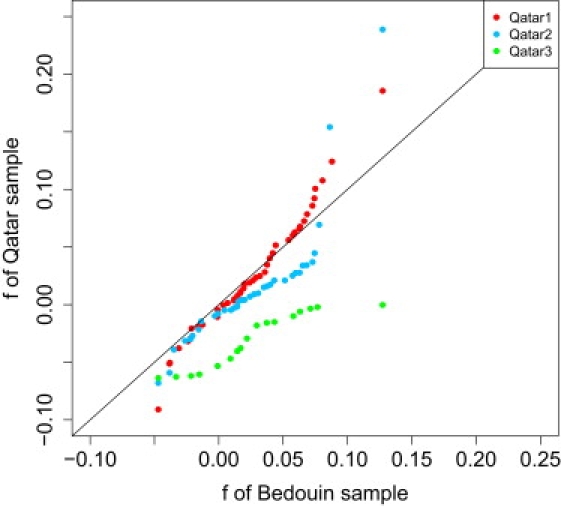

A quantile-quantile plot indicates how the degree of consanguinity compares to the HGDP sample for Bedouins, a group known to practice frequent first-cousin marriages (Figure 5).22 There exists a good correspondence, apart from two individuals who appear more strongly consanguineous than any of the Bedouin samples, between Qatar1 and the Bedouins. Sample size is taken into account when creating quantile-quantile plots in that quantiles for smaller samples are interpolated to match those of larger data sets, so the outliers are probably not due to differences in sample size.23 When examining runs of homozygosity, these two individuals have higher fractions of their genome contained in the runs when compared to the mean Qatari f, further supporting the idea that these individuals are highly consanguineous. However, there appears to be some trend toward less consanguinity for most Qatar2 individuals, even though this group also contains a few highly inbred individuals. Similar to what was seen in the previous histograms, the Qatar3 subgroup is remarkably nonconsanguineous relative to the Bedouin sample.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the Degree of Consanguinity across the Qatari Subgroups as Compared to the HGDP Bedouin Sample

Quantile-quantile plot comparing the Wright's inbreeding coefficient (f) as calculated with PLINK for each individual in each Qatari subgroup with the coefficients of each individual in the HGDP Bedouin sample. The plot indicates that the Qatar1 subgroup contains individuals with higher levels of consanguinity than individuals in the Bedouin sample. The Qatar2 subgroup contains individuals with a lesser degree of consanguinity (the trend of points below the diagonal) compared to individuals in the Bedouin sample, although there are two outlying individuals with unusually high consanguinity. Finally, the Qatar3 subgroup appears to be far less consanguineous than the Bedouin sample.

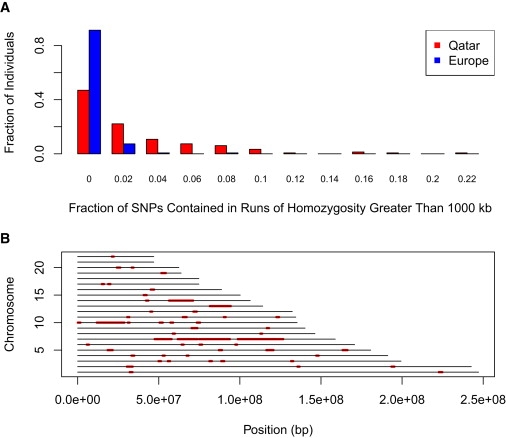

PLINK is able to identify runs of homozygosity, and, with a few assumptions, these runs of “identity by state” can be equated to runs of “identity by descent.” The implication is that the level of consanguinity may drive large portions of the genome to have descended from a single common ancestor several generations in the past. The contrast between the pattern of IBD sharing in the Qatari and the European American samples (Figure 6A) is striking, especially in the variance between samples of each data set. The European American samples are much more even in the regions of IBD, lacking both tails of the distribution borne by the Qatari, which contain some samples with a relative surplus and others with a remarkable paucity of IBD regions. Plots of the spans of homozygosity show that the Qatari sample has a wide range of homozygous blocks (Figure 6B), consistent with the variance in the degree of consanguinity (Figure 4).

Figure 6.

Spans of Genomes that Are Homozygous

(A) The fraction of each individual's genome that is contained within runs of homozygosity is plotted as a histogram for a sample of approximately 150 Qataris and 150 European Americans. The minimum length of each is 1000 kb or 100 SNPs. The Qataris exhibit greater variance in homozygosity relative to the European Americans.

(B) Runs of homozygosity for a single Qatari individual. The x axis is the position along a chromosome (0−250 Mbp), and the y axis is the chromosome number. Each red segment represents a block of sequence in which SNP marker genotypes are homozygous.

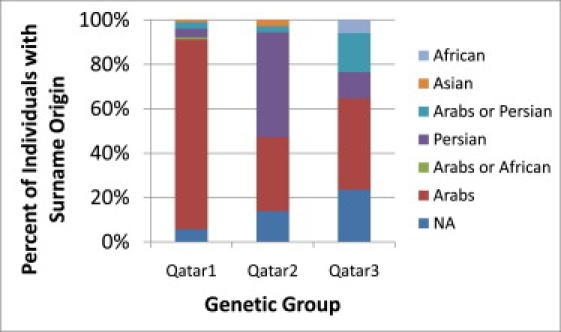

Correlations between Genetic Ancestry and Surname Lineage

A Mantel test comparing Qatari subgroups and surname origins indicates highly significant (p = 0.0001) correlations across the three population groups in the frequency of these name classifications, with the Qatar1 population having mostly Arab surnames, the Qatar2 population having a large Persian component, and the Qatar3 population appearing to be the most diverse and having the largest African component (Figure 7). In general, the genetics and this broad surname analysis appeared to be concordant.

Figure 7.

Surnames and Genetic Classifications

Composition of surnames within each of the three Qatari groups is indicated by color coding according to surname frequency within those groups. The genetic classification of Qatar1, Qatar2, and Qatar3 is significantly correlated with surname origins (Mantel test, p < 0.0001).

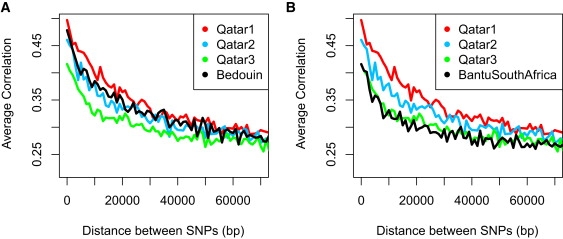

Decay of Linkage Disequilibrium

Pairwise linkage disequilibrium among pairs of SNPs is a fairly sensitive indicator of the past history of recombination and genetic drift. When we tallied the pairwise r2 for SNP pairs, binned them by distance in base pairs separating the SNPs along the genome (out to a maximum of 70 kb), and plotted the bin averages for each of the three Qatari subgroups, we see a strong difference among each group. In particular, the Qatar1 group shows the slowest decay of LD, in keeping with its identity as largely Arab and consistent with its history of consanguinity. In fact, Qatar1 has a rate of LD decay even slower than the HGDP Bedouin sample (Figure 8A). Care was taken to perform these comparisons with subsamples of the same sample size, because it is known that larger samples identify more recombinants and skew the LD downward.24 In the Qatar3 subgroup, the pattern of LD decay is similar to that seen in African samples of the HGDP (Figure 8B). LD is known to decay faster in Africans, most likely as a result of the larger and more long-term effective population size in Africa, and the fact that this population did not pass through an out-of-Africa bottleneck.25 In sum, there is little surprise that Qatar3, whose genetic affinity with the African populations had been identified by PCA, also shows a pattern of LD decay similar to that of Africans.

Figure 8.

Linkage Disequilibrium Decay across the Genomes of the Qatari Subgroups and Two HGDP Population Samples

(A) Linkage disequilibrium (LD) for pairs of SNPs less than 70 kb apart was calculated as the squared correlation coefficient (r2). Calculations were performed on a standard sample size (n = 5) of randomly selected individuals in each Qatari group. SNP pairs were partitioned into bins in 1 kb intervals, and for each bin the mean r2 was plotted. The Qatar1 group has the highest LD, consistent with their higher degree of consanguinity. Qatar2 is intermediate, and the Qatar3 group has the lowest LD between SNPs, consistent with a large African component in their genome. The Bedouin HGDP population sample appears to fall between that of the Qatar1 and Qatar2 groups.

(B) The decay of LD of the three Qatari samples is replotted here along with the Bantu South African sample of the HGDP set. The LD decay of the Bantu South African population sample overlaps with that of Qatar3, consistent with the Qatar3 sample being of largely African origin.

Discussion

The primary finding of the present report is that genetic variation among the current Qatari population is remarkably structured, and that this deep structure has been driven by historical migration and settlement in the area. We find that the Qatari can be largely divided into three primary affinity groups: one that is of Arab origin and may be descendants of the Bedouin tribes, another that has strong affinity with Iranian (“Persian”) and other more eastern populations, including those of Central Asia (such as the Uyghur), and a third that has strong affinity with Bantu-speaking Africans. The latter two groups show strong patterns of admixture, with individuals showing a continuous spread of genetic affinity from the Middle Eastern toward the Asian and African populations, respectively. The three groups demonstrate a strong correlation with family name that supports the local narrative on population history.

There is not a great wealth of literature on the genetic structure of the Qatari against which we can compare the present findings. A few studies have established some features of other Middle Eastern population samples, and the studies of the population of Saudi Arabia have advanced well. Previous studies examined the pattern of mtDNA variation in a Saudi sample, with a focus on testing whether the Arabian Peninsula is peopled by remnants of the expansion out of Africa some 150,000 years ago.26 The mtDNA lineages, because of their lack of recombination, retain clear information about maternal lineages, but because they do not recombine, they represent only one sampling of the myriad genealogical processes that occurred. The Saudi samples possessed both African lineages (20%) and eastern lineages (e.g., matching India and Central Asia) (18%), but the bulk was from a more northern origin (62%). This result suggests that, like the Qatari population, the Saudi population harbors a diverse array of genetic contributions following centuries of active trade and is not simply a relic of the ancient out-of-Africa migration. Patterns of Y chromosome variation are largely consistent with the mtDNA.27

The pattern of historical influx and admixture in Qatar is strongly different from patterns seen in Europe, where there is a remarkably clear pattern of isolation by distance.28–30 Even India, which also has had much population movement and a strong impact of caste structure, retains a strong geographical component to its genetic structuring.31 Historical patterns of migration and trade seem to dominate the pattern of influx of genetic variation into the Qatar peninsula, and the drive to the trading centers and large expanses of desert result in an abolition of patterns of isolation by distance. In this context, our primary finding of three distinct groups appears to match well with Qatar's migratory history.

The pattern of consanguinity, particularly the accepted practice of first-cousin marriages, has resulted in a high level of consanguinity and, as importantly, a huge interindividual range of variation in IBD sharing among the people of Qatar. The pattern of consanguinity is radically different among the three subgroups that we identified. These population-level findings have immediate and profound consequences for the practice of medical genetics in Qatar, and for the design and implementation of association testing in the future. The population is remarkably heterogeneous and structured. Ignoring this structure will lead to errors, both in individual diagnosis and in population-wide inference of SNPs that inflate risk of disease. It is also likely that these observations will be important in determining the genetic components involved in efficacy and adverse effects of pharmaceuticals in the different Qatari subpopulations. Such studies need to be conducted in the context of the knowledge of which subgroup each individual has the strongest genetic affinity with in order to draw accurate conclusions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the volunteers from Qatar who donated DNA. These studies were supported in part by the Qatar Foundation and Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar. H.H.-Z. and S.M. were supported by the Tri-Institutional Training Program in Computational Biology and Medicine at Cornell University. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health research grants HG003229, MH084685, and HL084706.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

References

- 1.Zeggini E., Scott L.J., Saxena R., Voight B.F., Marchini J.L., Hu T., de Bakker P.I., Abecasis G.R., Almgren P., Andersen G., Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyre D., Delplanque J., Chèvre J.C., Lecoeur C., Lobbens S., Gallina S., Durand E., Vatin V., Degraeve F., Proença C. Genome-wide association study for early-onset and morbid adult obesity identifies three new risk loci in European populations. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:157–159. doi: 10.1038/ng.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson M.G., Atwood L.D., Benjamin E.J., Cupples L.A., D'Agostino R.B., Sr., Fox C.S., Govindaraju D.R., Guo C.Y., Heard-Costa N.L., Hwang S.J. Framingham Heart Study 100K project: Genome-wide associations for cardiovascular disease outcomes. BMC Med. Genet. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manolio T.A., Collins F.S., Cox N.J., Goldstein D.B., Hindorff L.A., Hunter D.J., McCarthy M.I., Ramos E.M., Cardon L.R., Chakravarti A. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badii R., Bener A., Zirie M., Al-Rikabi A., Simsek M., Al-Hamaq A.O., Ghoussaini M., Froguel P., Wareham N.J. Lack of association between the Pro12Ala polymorphism of the PPAR-gamma 2 gene and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Qatari consanguineous population. Acta Diabetol. 2008;45:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s00592-007-0013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagy S. Making room for migrants, making sense of difference: Spatial and ideological expressions of social diversity in urban Qatar. Urban Stud. 2006;43:119–137. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandridge A.L., Takeddin J., Al-Kaabi E., Frances Y. Consanguinity in Qatar: Knowledge, attitude and practice in a population born between 1946 and 1991. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2010;42:59–82. doi: 10.1017/S002193200999023X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M.A., Bender D., Maller J., Sklar P., de Bakker P.I., Daly M.J., Sham P.C. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pritchard J.K., Stephens M., Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J.Z., Absher D.M., Tang H., Southwick A.M., Casto A.M., Ramachandran S., Cann H.M., Barsh G.S., Feldman M., Cavalli-Sforza L.L., Myers R.M. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science. 2008;319:1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1153717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartl D., Clark A.G. Fourth Edition. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2007. Principles of Population Genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson N., Price A.L., Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reich D., Price A.L., Patterson N. Principal component analysis of genetic data. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:491–492. doi: 10.1038/ng0508-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McVean G. A genealogical interpretation of principal components analysis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price A.L., Helgason A., Palsson S., Stefansson H., St Clair D., Andreassen O.A., Reich D., Kong A., Stefansson K. The impact of divergence time on the nature of population structure: An example from Iceland. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dray S., Dufour A.B. The ade4 package: Implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007;22:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao H., Williamson S., Bustamante C.D. A Markov chain Monte Carlo approach for joint inference of population structure and inbreeding rates from multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2007;176:1635–1651. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.072371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg N.A., Pritchard J.K., Weber J.L., Cann H.M., Kidd K.K., Zhivotovsky L.A., Feldman M.W. Genetic structure of human populations. Science. 2002;298:2381–2385. doi: 10.1126/science.1078311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg N.A., Mahajan S., Ramachandran S., Zhao C., Pritchard J.K., Feldman M.W. Clines, clusters, and the effect of study design on the inference of human population structure. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e70. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tishkoff S.A., Reed F.A., Friedlaender F.R., Ehret C., Ranciaro A., Froment A., Hirbo J.B., Awomoyi A.A., Bodo J.M., Doumbo O. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009;324:1035–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.1172257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reiner A.P., Ziv E., Lind D.L., Nievergelt C.M., Schork N.J., Cummings S.R., Phong A., Burchard E.G., Harris T.B., Psaty B.M., Kwok P.Y. Population structure, admixture, and aging-related phenotypes in African American adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;76:463–477. doi: 10.1086/428654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheffield V.C., Stone E.M., Carmi R. Use of isolated inbred human populations for identification of disease genes. Trends Genet. 1998;14:391–396. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01556-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rice J.A. Second Edition. Wadsworth, Inc.; Belmont, CA: 1995. Mathematical Statistics and Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss K.M., Clark A.G. Linkage disequilibrium and the mapping of complex human traits. Trends Genet. 2002;18:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reich D.E., Cargill M., Bolk S., Ireland J., Sabeti P.C., Richter D.J., Lavery T., Kouyoumjian R., Farhadian S.F., Ward R., Lander E.S. Linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nature. 2001;411:199–204. doi: 10.1038/35075590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abu-Amero K.K., Larruga J.M., Cabrera V.M., González A.M. Mitochondrial DNA structure in the Arabian Peninsula. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:45–59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abu-Amero K.K., Hellani A., González A.M., Larruga J.M., Cabrera V.M., Underhill P.A. Saudi Arabian Y-Chromosome diversity and its relationship with nearby regions. BMC Genet. 2009;10:59–67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson M.R., Bryc K., King K.S., Indap A., Boyko A.R., Novembre J., Briley L.P., Maruyama Y., Waterworth D.M., Waeber G. The Population Reference Sample, POPRES: A resource for population, disease, and pharmacological genetics research. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novembre J., Johnson T., Bryc K., Kutalik Z., Boyko A.R., Auton A., Indap A., King K.S., Bergmann S., Nelson M.R. Genes mirror geography within Europe. Nature. 2008;456:98–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auton A., Bryc K., Boyko A.R., Lohmueller K.E., Novembre J., Reynolds A., Indap A., Wright M.H., Degenhardt J.D., Gutenkunst R.N. Global distribution of genomic diversity underscores rich complex history of continental human populations. Genome Res. 2009;19:795–803. doi: 10.1101/gr.088898.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reich D., Thangaraj K., Patterson N., Price A.L., Singh L. Reconstructing Indian population history. Nature. 2009;461:489–494. doi: 10.1038/nature08365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.