Abstract

Expression of nitrogen metabolism genes is regulated by the quality of the nitrogen supply. Here, we describe a mechanism for the transcriptional regulation of the general amino acid permease gene per1 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. We show that when ammonia is used as the nitrogen source, low levels of per1 are transcribed and histones in the coding and surrounding regions of per1 are acetylated. In the presence of proline, per1 transcription is upregulated and initiates from a more upstream site, generating 5′-extended mRNAs. Concomitantly, histones at per1 are deacetylated in a Clr6-dependent manner, suggesting a positive role for Clr6 in transcriptional regulation of per1. Upstream initiation and histone deactylation of per1 are constitutive in cells lacking the serine/threonine kinase oca2, indicating that Oca2 is a repressor of per1. Oca2 interacts with a protein homologous to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcriptional activator Cha4 and with Ago1. Loss of Cha4 or Ago1 causes aberrant induction of per1 under noninducing conditions, suggesting that these proteins are also involved in per1 regulation and hence in nitrogen utilization.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are able to use a wide variety of nitrogen sources, although not all support growth equally well. Ammonia is a good nitrogen source, whereas proline is less preferred because it first needs to be metabolized into ammonia. In order to adapt to the quality of the nitrogen supply, yeast initiates new programs of gene expression. Thus, the genes encoding transporters and catabolic enzymes required for proline are repressed when ammonia is available but become derepressed in the presence of proline (46).

In S. cerevisiae, proline is taken up by the general amino acid permease Gap1 and by the proline-specific permease Put4. The stability and endocytotic sorting of Gap1 are regulated by Npr1, a protein kinase that acts in the TOR pathway (9). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the two genes SPAP7G5.06 and SPAC869.10 (now called per1 and put4) encode plasma membrane transporters that are related to S. cerevisiae Gap1 and Put4, respectively. In the presence of ammonia, low levels of per1 and put4 are transcribed, but their transcription increases when cells are grown in proline (50).

One mechanism by which gene expression can be regulated is through the reversible acetylation of histones. The presence of acetyl groups on histone amino-terminal tails alters chromatin structure, which can affect the recruitment of the transcription machinery to initiation sites, as well as the passage of the elongating polymerase. Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deactylases (HDACs) function antagonistically in the dynamic acetylation of histones and thus act as regulatory switches of gene activity. Historically, histone acetylation by HATs has been correlated with gene activation, whereas histone deacetylation by HDACs has been associated with gene repression.

Type A HATs modify nucleosomal histones and often act as cofactors for DNA sequence-specific transcription factors, whereas type B HATs acetylate newly synthesized free histones, which is thought to be important for chromatin assembly onto replicating DNA (34). HDACs are usually part of multiprotein complexes and exist as three types, with representatives in both S. pombe and S. cerevisiae. In S. pombe, HDACs are classified as either Clr6- and Hos2-like enzymes (S. cerevisiae Rpd3 and Hos2), Clr3-like enzymes (S. cerevisiae Hda1), or Sir2-like enzymes (S. cerevisiae Sir2). HDACs can act in a targeted way through their recruitment by DNA-binding proteins to promoters, where they locally deacetylate specific histones. They can also act in a nontargeted, global way through deacetylation of larger domains, including coding and surrounding regions (25).

Clr6 exists in two physically and functionally separate complexes. Complex I deacetylates mainly gene promoters, particularly those of highly expressed genes, and represses transcription of the reverse strand of centromeric repeats, which is also driven by bona fide promoter elements (33). In contrast, complex II preferentially targets coding regions to repress spurious sense and antisense transcription of genes, as well as forward-strand transcription of centromeric repeats (33). The S. cerevisiae complexes Rpd3L and Rpd3S are structurally and functionally related to complexes I and II, respectively. Rpd3L has been implicated in deacetylation of promoter regions, whereas Rpd3S localizes to coding regions and prevents aberrant transcription from cryptic initiation sites (8, 24).

Although HDACs are generally described as transcriptional repressors, several reports have provided evidence that they can also act as activators of gene expression. S. cerevisiae Rpd3 has been shown to preferentially associate with the promoters of highly transcribed genes (26). Furthermore, Rpd3 is required for the activation of osmoresponsive, DNA damage-inducible, and anaerobic genes, where upon induction of the gene, Rpd3 is recruited to and deacetylates the promoter (10, 43, 44). Hos2 is required for the transcriptional activation of the S. cerevisiae GAL genes, but in this case, it has been shown to deacetylate their coding regions (49). Likewise, S. pombe Hos2 promotes high expression of growth-related genes by deacetylating their open reading frames (ORFs) (52).

Here, we describe a mechanism for the transcriptional regulation of the S. pombe gene per1. We show that upon proline-induced activation, per1 transcripts with a longer 5′ untranslated region (UTR) are synthesized compared to transcripts produced in the presence of ammonia. Concomitantly, a region spanning the coding and upstream sequences of per1 is deacetylated in a Clr6-dependent way, suggesting a positive role for Clr6 in transcriptional regulation of the gene. Both 5′-extended transcripts and histone deacetylation are constitutive in cells lacking the serine-threonine kinase Oca2, indicating that Oca2 represses per1 activation. In the absence of Clr6, Oca2-dependent repression is no longer observed, implying a functional interaction between these two regulators. Oca2 also binds to a protein with homology to the S. cerevisiae transcriptional activator Cha4 and to Ago1, a key component of the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway (12). Loss of either protein leads to aberrant regulation of per1, suggesting that these proteins are also involved in regulating per1 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

The S. pombe strains used are described in Table 1 (see the supplemental material). All growth conditions, maintenance, and genetic procedures used in this work have been described previously (31). Strains were grown at 30°C in yeast extract (YE) or Edinburgh minimal medium (EMM) with appropriate supplements, 2% glucose, and either 0.5% ammonia or 10 mM proline as a nitrogen source. Rapamycin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)/methanol and added at 0.3 μM.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| A2 | h+ ade6-M216 his3-D1 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | Laboratory stock |

| 972 | h− | Laboratory stock |

| oca2Δ | h+ ade6-M216 his3-D1 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | Laboratory stock |

| oca2Δ::kanMX6 | ||

| oca2-HA | h+ ade6-M216 his3-D1 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | Laboratory stock |

| oca2-HA::kanMX6 | ||

| oca2Δ-20 | h−oca2Δ::kanMX6 | This study |

| cha4Δ | h+ ade6-M216 his3-D1 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| cha4Δ::kanMX6 | ||

| ago1Δ | h+ ade6-M216 his3-D1 leu11-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| ago1Δ::kanMX6 | ||

| hat1Δ | h+ ade6-M216 his3-D1 leu11-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| hat1Δ::kanMX6 | ||

| clr6-1 | h−clr6-1 | 52 |

| clr4Δ | h+ clr4::hph+ otr1R(SphI)::ade6-M210 | Robin Allshire |

| oca2Δ clr6-1 | h? ade6-M216 leu1-32 oca2 Δ::kanMX6 clr6-1 | This study |

| Wt | h+ leu1-32 ade6-M216 ura4-D18 | Marc Buehler |

| imr1R(NcoI)::ura4+ oriI | ||

| rrp6Δ | h+ leu1-32 ade6-M216 ura4-D18 | Marc Buehler |

| imr1R(NcoI)::ura4+ oriI rrp6Δ::Natr | ||

| Flag-ago1 | h+ otr1R(SphI)::ura4+ ura4-DS/E leu1-32 | 6 |

| ade6-M210 Natr-nmt1-3×FLAG::ago1 |

Genetic manipulations.

The cha4Δ, ago1Δ, and hat1Δ genes (Table 2 ) were disrupted in strain A2 via homologous recombination using a PCR fragment amplified from the plasmid pFa6a-KanMX6 (3) and the primers listed in Table 3 (see the supplemental material). Gene replacement was confirmed by PCR using primers specific for KanMX6 and gene-specific sequences. For generation of the double mutants oca2Δ clr6-1 and oca2Δ hat1Δ, the haploid strains oca2Δ and clr6-1, and oca2Δ-20 and hat1Δ, respectively, were crossed on Sporulation plates and incubated at 25°C for 3 days. Tetrads were dissected using a Singer Instruments MSM system, and spores were tested by colony PCR for the presence of the disrupted oca2Δ::KanMX6 and hat1Δ::KanMX6 alleles and by DNA sequencing for the clr6-1 mutation.

TABLE 2.

Genes used in this study

| Name | Systematic name |

|---|---|

| oca2 | SPCC1020.10 |

| ppk8 | SPAC22G7.08 |

| cha4 | SPBC1683.13c |

| hat1 | SPAC139.06 |

| prw1 | SPAC29A4.18 |

| per1 | SPAP7G5.06 |

| put4 | SPAC869.10 |

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Sequence or reference | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1F | TGTGTCTCGGCTTACCCTTC | ChIP per1 |

| 1R | GCGGAAAGAGACGGATAACA | ChIP per1; 5′ RACE |

| 1BR | GTGCAATCTACTAGCAACCAAG | 5′ RACE |

| 2F | GCTCTCCAAGTGCCAGTTTC | ChIP per1 |

| 2R | GCCGCACAATATGGATAAGG | ChIP per1 |

| 3F | CGCATCTTGCATTATTTCACC | ChIP per1 |

| 3R | AAACGATTGGGAAACACTCG | ChIP per1; 5′ RACE |

| 4F | GTCGCCAGATCGCTCTATTG | ChIP per1 |

| 4R | TGGGATGAATGTCGAAAACA | ChIP per1; 5′ RACE |

| 5F | GCGGTGGTGTTCCTACTGAT | ChIP; qRT-PCR |

| 5R | GCACGAGGGAGAGACTTTTG | ChIP; qRT-PCR |

| 6F | TGATTTAGACACGGGACTTCG | ChIP per1 |

| 6R | CAAAGAGATTGCCAAATCCA | ChIP per1 |

| 7F | CGTTGTAAGTTTATATGTTGAAGCA | ChIP per1 |

| 7R | TGCGAATGCAAGGCATAATA | ChIP per1 |

| 8F | ATATAATGTTGAGCTCCTTGGTTAGC | ChIP per1 |

| 8R | TGAGCTTGATAAGGCGGTCT | ChIP per1 |

| Put4BF | AAAAAGGCGTTGCAGTATGA | ChIP put4 |

| Put4BR | TTTCTCCGTACTTCTTTTCAACG | ChIP put4 |

| Adh1PF | CTTCCGCGTCTCATTGGT | ChIP adh1 |

| Adh1PR | TTGCTTAAAGAAAAGCGAAGG | ChIP adh1 |

| dhF | 21 | ChIP dh |

| dhR | 21 | ChIP dh |

| Put4F | ACATGATCGCTTGGGTTTTC | qRT-PCR put4 |

| Put4R | TTAGGGATGTTACGCCTTGG | qRT-PCR put4 |

| Adh1F | CGTATTGACTCTATCGAGGCTCTT | qRT-PCR adh1 |

| Adh1R | CTTGGAAAGGTCCAAGACGA | qRT-PCR adh1 |

| RT-PCR1 | 51 | RT-PCR dh |

| RT-PCR2 | 51 | RT-PCR dh |

| ACTF | 51 | RT-PCR act1 |

| ACTR | 51 | RT-PCR act1 |

| ORFT7 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCGGTGGTGTTCCTACTGAT | Northern per1 |

| ORFT3 | AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGACCAACACGAAGGGAGAGGTA | Northern per1 |

| US2T7 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCCCATTCCCATTCAATTTT | Northern per1 |

| US2T3 | AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGAATGTTTGAGCGCGTGTATGT | Northern per1 |

| US1T7 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACTGCTGCAAAACTTTGGTTG | Northern per1 |

| US1T3 | AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGATTAGTTACCCTATTTGGAAG | Northern per1 |

| RplAT7 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCTCGTATCTGTGCCAACAA | Northern rpl1002 |

| RplAT3 | AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGAGTAGCAACCGTCGGGAATAA | Northern rpl1002 |

| RplBT7 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGATGGTGTTGGATGAATCGGTA | Northern rpl1002 |

| RplBT3 | AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGACGTGGAAGTAGATGCGGAGT | Northern rpl1002 |

| Adh1T7 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGATTCAAGGTGACTGGCCTCTT | Northern rpl1002 |

| Adh1T3 | AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGACAAGGCACGATAGCAAGTGA | Northern adh1 |

| Prw1FT7 | GTGATAACTACTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAATGGC TGTATCAGCTGTTC | Northern adh1 |

| Prw1R | TTAACTTAAATATGCCGTAG | In vitro translation |

| Cha4FT7 | GTGATAACTACTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAATGCAAATGAAACCCCGAC | In vitro translation |

| Cha4R | TTAATATTTTACATTGGGAG | In vitro translation |

| In vitro translation | ||

| Hat1F | ATGAGTGCTG TTGATGAATG | pBS-hat1 |

| Hat1R | TTAGGAAGAAGATTGAGCAAG | pBS-hat1 |

| Mis16F | ATGTCAGAGGAAGTAGTCC | pBS-mis16 |

| Mis16R | TTACTCCAGATCCCTAGGAG | pBS-mis16 |

| Ago1F | GATGTCGTATAAACCAAGCTCAG | pBS-ago1 |

| Ago1R | TTACATATACCACATCTTTGTTTTC | pBS-ago1 |

| P14 | ACCCCCGGGCATGTCTGTCACCCT | pGEX4T1-oca2 |

| P15 | GGACCCGGGATGCTTTGCAGGTGG | pGEX4T1-oca2 |

| Hat1KanF | GAGCTAGAAATCTATATAATAGTAAATATTTTTTAATAATAACAGGTGTAGCACGTGAAAGCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA | hat1Δ |

| Hat1KanR | TAAATTTTGGAAAAAGCAGTTCATTATGAGGAATTGTTTGAATTTTTATAAGGTGCCTTTGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC | hat1Δ |

RNA analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from exponentially growing S. pombe cells (∼1 × 107 cells/ml) using the hot-phenol method as previously described (27). For whole-genome expression profile analysis, 10 to 20 μg of total RNA was labeled by direct incorporation of either fluorescent Cy3- or Cy5-dCTP (GE Healthcare), and the fluorescently labeled products were hybridized to S. pombe cDNA microarrays as previously described (27). The microarrays were scanned using a GenePix 4000B laser scanner (Axon Instruments), and fluorescence intensity ratios were calculated with GenePix Pro (Axon Instruments). The data were normalized using Perl script as previously described (27). For quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR, 200 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed with Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Stratagene), followed by qPCR with a QuantiTect SYBR green kit (Qiagen) on a Corbett Rotor-Gene 3000 machine using the primers listed in Table 3. Values were normalized to actin and expressed as percentages of wild-type (wt) values. For Northern blot analysis, 15 μg of total RNA was separated on 1% formaldehyde agarose gels. Templates for single-stranded RNA probes were amplified from S. pombe genomic DNA using the primers listed in Table 3. The probes were in vitro transcribed using T3 or T7 RNA polymerase (T7/T3 MAXI kit; Ambion) for detection of sense or antisense transcripts, respectively, and hybridized at 62°C (7).

S. pombe whole-cell protein extracts.

Cells were grown to ∼1 × 107 cells/ml, harvested, washed in water, and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]). The cells were disrupted with glass beads by vortexing them 12 times for 30 s each time at 4°C, followed by centrifugation. The protein concentration was determined by measuring absorbance at 280 nm. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis were performed according to standard procedures using antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) (F-7; Santa Cruz) and antitubulin (kindly provided by K. Gull) antibodies.

Recombinant and in vitro-translated proteins.

For expression of GST-Oca2 in Escherichia coli, the whole oca2 ORF was PCR amplified from S. pombe genomic DNA using primers P14 and P15 (Table 3) and cloned into pGEX4T1 (Pharmacia), giving rise to pGEX4T1-Oca2. For in vitro translation of ago1, the ago1 ORF was subcloned from clone pDONR210 (kindly provided by R. Allshire) into pBS using oligonucleotides Ago1F/Ago1R. For in vitro translation of cha4 and prw1, the respective ORFs were PCR amplified from S. pombe cDNA using oligonucleotides Cha4FT7/Cha4R or Prw1FT7/Prw1R. For in vitro translation of hat1 and mis16, the respective ORFs were PCR amplified from S. pombe cDNA using oligonucleotides Hat1F/Hat1R and Mis16F/Mis16R and cloned into pBS. In vitro translation was performed using a TNT-coupled transcription and translation rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) and [35S]methionine. GST-Oca2 was expressed in BL21-CodonPlus-RP cells (Stratagene) and purified according to standard procedures with GSH-Sepharoase (Pharmacia). Proteins were concentrated in Centricon MWCO-10 (Millipore) and dialyzed against buffer D (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.02% NP-40, 0.1 mM DTT) for 4 h at 4°C.

In vitro protein binding assays.

Purified glutathione S-transferase (GST) protein (1 μg) was incubated with 5 to 6 μl of in vitro-translated protein for 1 h at 25°C in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 75 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.01% NP-40, 0.05 mg/ml bovine serum albumin [BSA]). Protein complexes were bound to GSH-Sepharose that was preblocked with BSA, washed four times with IPP150 (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 150 mM KCl, 0.1% NP-40), eluted with SDS loading buffer, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

ChIP analysis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was performed using exponentially growing cells (∼1 × 107 cells/ml) as described previously (35), except that the cells were broken using a MagNA Lyser (Roche). Chromatin was shared by sonication for 30 s on/30 s off at medium setting for 10 min. Cross-linked proteins were immunoprecipitated using antibody H8 (ab5408; Abcam) or anti-H4K12ac (ab1761; Abcam). Immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified using real-time PCR with a QuantiTect SYBR green kit (Qiagen) on a Corbett Rotor-Gene 3000 machine. The primer efficiency was normalized using genomic DNA. ChIP signal values were expressed as percentages of input DNA corrected for the no-antibody background. The sequences of primers used for amplification of precipitated DNA are listed in Table 3.

RESULTS

Oca2 is involved in the utilization of different nitrogen sources.

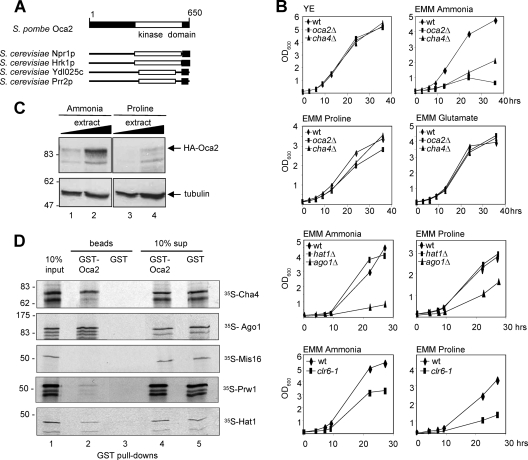

A previous genetic screen aimed at identifying multicopy suppressors of a transcription termination mutant in S. pombe led to the isolation of oca2, a predicted serine/threonine kinase (2; A. Azad and N. J. Proudfoot, unpublished data). oca2 was independently identified in a screen for S. pombe genes causing overexpression-mediated cell cycle arrest and cell elongation (45). Oca2-His6 expressed in Sf9 insect cells phosphorylates myelin basic protein (MBP) in vitro, confirming that Oca2 has kinase activity (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Moreover, we found that Oca2 preferentially phosphorylates serines and threonines surrounded by basic residues (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Proteomic analysis revealed that Oca2 belongs to a family of fungus-specific protein kinases that regulate plasma membrane transporters (20). In S. cerevisiae, the closest homologs of Oca2 are Npr1, Hrk1, Ydl025c, and Prr2, with the homology mainly in the C-terminal kinase domain (Fig. 1 A). In S. pombe, a second Oca2-like protein kinase (SPAC22G7.08) with unknown function exists (5).

FIG. 1.

(A) Oca2 is related to S. cerevisiae Npr1. Shown is a schematic representation of Oca2 protein and Oca2-related proteins based on amino acid sequence homology. The C-terminal kinase domain is denoted by a white box. Regions with sequence similarity are indicated. (B) oca2Δ cells grow slowly in EMM containing ammonia. The wt and mutant cells indicated were grown to mid-exponential phase in YE and diluted in EMM containing ammonia, proline, or glutamate, and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured at the indicated time points. (C) Oca2 protein decreases when cells are grown in proline. Total protein extract from an HA-oca2-tagged strain grown in ammonia or proline and 150 and 300 μg of total protein extract were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against HA (top) and tubulin (bottom). (D) Oca2 interacts with Cha4, Ago1, Prw1, and Hat1. GST pulldown experiments employed recombinant GST-Oca2 or GST and in vitro-translated Cha4, Ago1, Mis16, Prw1, and Hat1. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Lane 1, 10% of the total input of each in vitro-translated protein; lanes 2 and 3, bound proteins; lanes 4 and 5, 10% of the supernatant of each binding reaction after removal of the GSH beads. The calculated molecular masses were as follows: Cha4, 72 kDa; Ago1, 94 kDa; Mis16, 48 kDa; Prw1, 48 kDa; Hat1, 44 kDa. The lower-molecular-mass bands correspond to degradation or premature termination products of the in vitro translation reaction.

S. cerevisiae Npr1 regulates nitrogen utilization by controlling the stability and sorting of the general amino acid permease Gap1 in response to nitrogen (9). Interestingly, we found that the loss of oca2 leads to a slow-growth phenotype when cells are grown in minimal medium (EMM) with ammonia as the nitrogen source, but cells grow normally in proline or glutamate (Fig. 1B), suggesting that Oca2 has a role in the response to nitrogen availability similar to that of Npr1. In addition, oca2Δ cells are resistant to rapamycin in minimal medium with ammonia (even though growth is already slow), another similarity to S. cerevisiae Npr1 (40) (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Using an HA-oca2-tagged strain and Western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts, we also observed that the levels of Oca2 protein were higher in cells grown in ammonia than in cells grown in proline (Fig. 1C), suggesting that Oca2 is required for growth in ammonia but is dispensable when proline is used. The observed molecular mass of HA-Oca2 was slightly larger than predicted (74.5 kDa). This difference could be due to phosphorylation, as phosphatase treatment of HA-Oca2 leads to a decrease in molecular mass (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material).

To further characterize Oca2, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen to identify Oca2-interacting proteins. Using Oca2 fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain as bait, we isolated two positive clones, SPBC1683.13c and ago1 (A. Azad, data not shown). SPBC1683.13c contains a Zn2-C6 zinc finger domain and is related to the S. cerevisiae transcriptional activators Cha4 and Tea1, which regulate serine-regulated and Ty1 enhancer-regulated genes, respectively (10a, 17). Because of its greater homology to S. cerevisiae Cha4, we renamed SPBC1683.13c Cha4. Ago1 is a subunit of the RNA-induced transcriptional silencing (RITS) complex involved in RNAi-induced heterochromatin formation (12).

To confirm the interactions obtained by the two-hybrid screen, we performed GST pulldown experiments using recombinant GST-tagged Oca2 and in vitro-translated Cha4 and Ago1, respectively. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 1D, about 10% of the total input Cha4 and Ago1 were bound by GST-Oca2, but not by GST, confirming that Oca2 interacts with the proteins.

S. cerevisiae Npr1 has been shown to bind to Cac3 (Msi1), a subunit of the chromatin assembly factor CAF1 and the negative regulator of the RAS/cyclic AMP (cAMP) pathway (22). The S. pombe genome encodes three proteins with sequence homology to Cac3: Mis16, a kinetochore protein (15); Prw1, a subunit of the Clr6 HDAC complex (33); and Hat1, a type B HAT (4). To test whether the interaction between Npr1 and Cac3 was conserved in S. pombe, we performed GST pulldown experiments using in vitro-translated Mis16, Prw1, or Hat1. As shown in Fig. 1D, Oca2 bound to Hat1 and weakly to Prw1, but not to Mis16. These associations appear weaker than those of Oca2 with Cha4 and Ago1. It is possible that the interactions between Oca2 and Prw1 or Hat1 are relatively transient and thus unstable, as was found for S. cerevisiae Nrp1 and Cac3 (22).

Because of the observed interaction of Oca2 with Cha4, Ago1, Prw1, and Hat1, we also measured the growth phenotypes of strains carrying mutations in these genes (Fig. 1B). cha4Δ cells had a phenotype similar to that of oca2Δ cells, with slow growth in EMM containing ammonia as the nitrogen source but normal growth in proline. Likewise, cells lacking Ago1 showed a moderately slow growth phenotype in proline but a severe growth defect in ammonia. Prw1 is a subunit of the Clr6-containing HDAC; we therefore looked at the growth phenotype of a strain carrying the clr6-1 mutant allele (11). clr6-1 mutant cells grew slightly more slowly in ammonia, but their growth was severely impaired in proline, thus showing growth characteristics opposite to those of oca2Δ, cha4Δ, and ago1Δ. Finally, hat1Δ cells grew normally in both ammonia and proline. As with oca2Δ, cha4Δ and ago1Δ are resistant to rapamycin (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material).

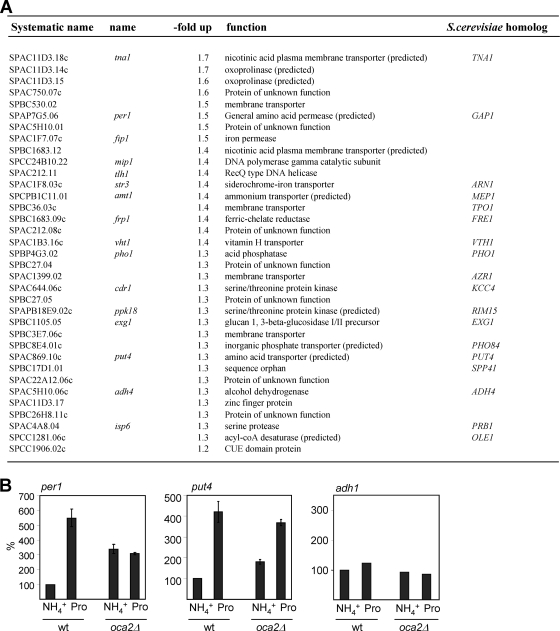

Membrane transporter genes are upregulated in the absence of Oca2.

To assess the role of Oca2 in gene expression, we carried out a whole-genome expression analysis of oca2Δ cells grown in minimal medium with ammonia as the nitrogen source. Compared to a wt strain, cells lacking oca2 showed downregulated (≥1.5-fold) expression of 36 genes, many of which code for proteins of unknown function (data not shown). The expression of six genes was increased ≥1.5-fold (Fig. 2 A), among them per1. Thirty-four genes, many of which code for membrane transporter proteins, including put4, showed more modest (≥1.25-fold) upregulation in oca2Δ cells. We also noticed that a large number of the upregulated genes were clustered near either subtelomeric regions or the centromere. Thus, of the 21 genes that were upregulated ≥1.25-fold on chromosome 1, for example, 11 were located within 150 kb of the telomeric ends, including the first (SPAC212.11; tlh1) and the last (SPAC750.07c) ORFs at the left and right telomeric ends, respectively, and one (per1) was the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcribed gene closest to the left outermost region of the centromere (see Fig. 6A).

FIG. 2.

Loss of oca2 leads to upregulation of genes coding for membrane transporters. (A) Whole-genome expression analysis of oca2Δ cells grown in EMM with ammonia. Genes that were upregulated ≥1.25-fold are listed. (B) oca2Δ cells show increased mRNA levels of per1 and put4. mRNA levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR, normalized to actin, and expressed as percentages of wt cells grown in ammonia. The data shown represent the average and standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least three independent experiments. Controls without reverse transcriptase gave background signals (not shown).

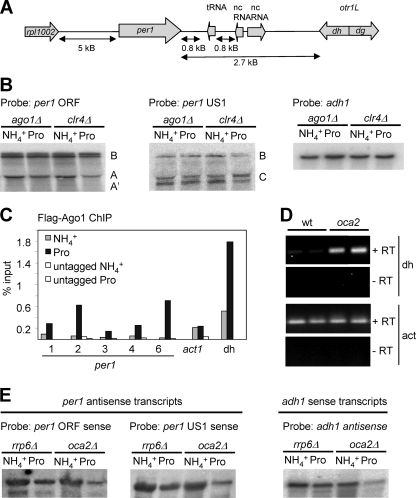

FIG. 6.

Ago1 is involved in regulation of per1. (A) Schematic representation of the per1 genomic region. nc, noncoding. (B) Northern blot analysis of per1 mRNA from ago1Δ and clr4Δ cells using probes ORF (left), US1 (middle), and adh1 (right). (C) ChIP analysis of Ago1 using a Flag-ago1 strain and anti-Flag antibody. Primer probes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 were specific for per1, as indicated. Probes act1 and dh were specific for act1 and the dh centromeric repeat, respectively. An untagged strain was used as a negative control. (D) RT-PCR of centromeric (dh) and actin transcripts using RNA isolated from wt and oca2Δ cells grown in ammonia. RNA was reverse transcribed using random hexamers and PCR amplified using primers specific for the dh centromeric repeat or actin. (E) Northern blot analysis of per1 antisense transcripts from rrp6Δ and oca2Δ cells using single-stranded RNA probes mapping to the ORF (left) and US1 (middle) of per1. (Right) Loading control using a single-stranded RNA probe specific for sense adh1 transcripts.

To validate the data from the above expression-profiling analysis, we determined the mRNA expression levels of selected genes using qRT-PCR. We analyzed the genes per1 and put4, whose transcription is regulated by proline (50) and whose aberrant expression in oca2Δ cells could thus be linked to the growth phenotype we observed in that strain. We found that in an oca2Δ strain grown in EMM with ammonia, the levels of per1 and put4 transcripts were upregulated between 2- and 3-fold compared to a wt strain, confirming the expression-profiling analysis (Fig. 2B). Note that these transcript level increases are greater than those observed in the genome-wide expression analysis, reflecting the greater dynamic range of qRT-PCR analysis. A similar or slightly greater increase of per1 and put4 expression was detected in wt cells grown in proline, consistent with earlier reports (50). In contrast, levels of adh1 mRNA remained constant in oca2Δ cells or in wt cells grown in either nitrogen source. Overall, we showed that the absence of Oca2 leads to increased levels of per1 and put4 transcripts, similar to wt cells that are grown in proline. This suggests that in the presence of ammonia, Oca2 acts as a repressor of these genes.

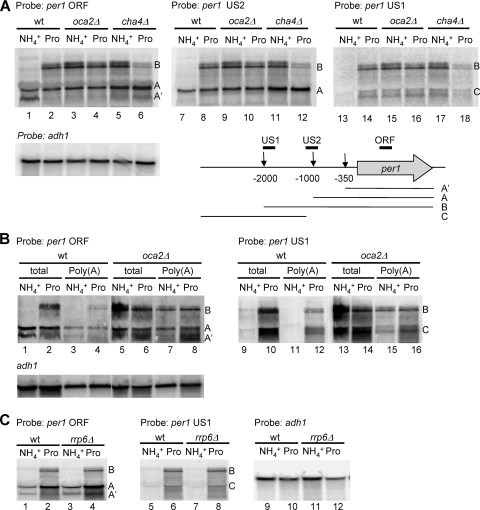

5′-extended transcripts accumulate upon activation of per1.

To characterize the expression profile of per1 in more detail, we performed a Northern blot analysis with total RNA isolated from wt and oca2Δ strains and strand-specific probes for per1. Using a probe for the ORF of per1 (probe ORF), we detected one major transcript in RNA from wt cells grown in ammonia (transcript A) (Fig. 3 A, lane 1). Compared to the known size of the actin mRNA, the size of transcript A was estimated to be around 2,800 bp, which is about 1,000 bp larger than the ORF of per1. A slightly shorter transcript was also observed (transcript A′). When wt cells were grown in proline, an additional major transcript of about 3,800 bp was detected (transcript B) (Fig. 3A, lane 2), whereas transcript A′ was no longer observed. Both, transcripts A and B were constitutively expressed in oca2Δ cells irrespective of the nitrogen source (lanes 3 and 4). Using a probe mapping to a region 600 bp downstream of the per1 stop codon, transcripts A and B were no longer detectable (data not shown), whereas a probe specific for a region 1,000 bp upstream of the start codon (probe US2) (Fig. 3A, middle) detected both mRNAs. Using a probe that hybridized even further upstream (probe US1) (Fig. 3A, right), we detected transcript B, but not transcript A, indicating that transcript B is a 5′-extended form of transcript A. Probe US1 also detected several additional, shorter transcripts (transcript C) (lanes 14 to 18). To rule out the possibility that transcript B was due to transcriptional read-through from the upstream ribosomal protein gene rpl1002 into per1 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), we also tested probes mapping to the ORF (probe A) or immediately downstream of rpl1002 (probe B). Probe A detected a transcript of about 700 bp, corresponding to the size of rpl1002, while probe B detected low levels of short 3′-extended transcripts, particularly for wt cells grown in ammonia. No longer read-through transcripts the same size as transcript B were detected. Overall, these data suggest that in wt cells, proline-dependent stimulation leads to the production of a longer per1 mRNA derived from an upstream initiation site. Furthermore, in oca2Δ cells, this profile of per1 expression is constitutive.

FIG. 3.

5′-extended per1 transcripts. (A) Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from wild-type, oca2Δ, and cha4Δ cells grown in either ammonia or proline. The Northern blot was consecutively probed with single-stranded RNA probes mapping to the ORF (left), a region 1 kb upstream of the AUG (US2; middle), or a region 1.7 kb upstream of the AUG (US1; right) to detect per1 sense transcripts. A probe specific for the ORF of adh1 was used as a loading control. A summary of the transcripts detected by Northern blotting with their average transcription initiation site as determined by 5′ RACE is shown schematically. (B) 5′-Extended transcripts of per1 are polyadenylated. Total RNA and poly(A)-selected RNA were analyzed by Northern blotting as indicated. The blot was subsequently probed for adh1 as a loading control. (C) Northern blot of total RNA isolated from wt and rrp6Δ cells using probes ORF (left), US1 (middle), and adh1 (right).

We also examined the expression pattern of per1 in cha4Δ cells. In RNA from cha4Δ cells grown in ammonia, we detected transcripts A, B, and C, similar to oca2Δ (Fig. 3A, lanes 5, 11, and 17). However, cha4Δ cells grown in proline produced transcript A but only small amounts of transcripts B and C, a profile more similar to that of wt cells grown in ammonia. Therefore, cha4 cells showed aberrant expression of per1 in both nitrogen sources, whereas oca2Δ cells showed a defect only in ammonia.

Rapamycin has been shown to reduce the expression of per1 and put4 (50). Adding rapamycin to oca2Δ or cha4Δ cells that were grown with ammonia led to a reduction of transcripts B and C and to an increase of transcript A, a profile closer to the one displayed by wt cells grown with this nitrogen source (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). This observation could thus explain the improved growth phenotype of oca2Δ and cha4Δ in the presence of the drug.

To further characterize the different per1 transcripts, we performed a rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) analysis to map their transcription initiation sites. Using RNA isolated from wt and oca2Δ cells grown with either ammonia or proline, three main populations of 5′-RACE products were obtained, corresponding to transcription initiation sites around bp −350, −1000, and −2000, respectively (Fig. 3A; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The product relating to a 5′ end at bp −2000 was obtained only with RNA from wt cells grown in proline or oca2Δ cells grown with ammonia or proline, confirming the results from Northern blot analysis.

To investigate whether the per1 transcripts were polyadenylated, we performed Northern blot analysis on poly(A)-selected RNA using probes US1 and ORF (Fig. 3B). Transcripts A, A′, B, and C were all polyadenylated, a hallmark of protein-encoding transcripts, but also of unstable regulatory transcripts degraded by the exosome (39). To test whether transcripts B and C were cryptic transcripts that were degraded in the nucleus, we analyzed RNA isolated from an rrp6Δ mutant strain that is defective in the nuclear exosome function. As shown in Fig. 3C, lack of rrp6 did not lead to the stabilization and accumulation of transcripts B and C, indicating that they are not cryptic unstable transcripts.

Pol II occupancy and histone acetylation of per1 increases upon transcriptional stimulation.

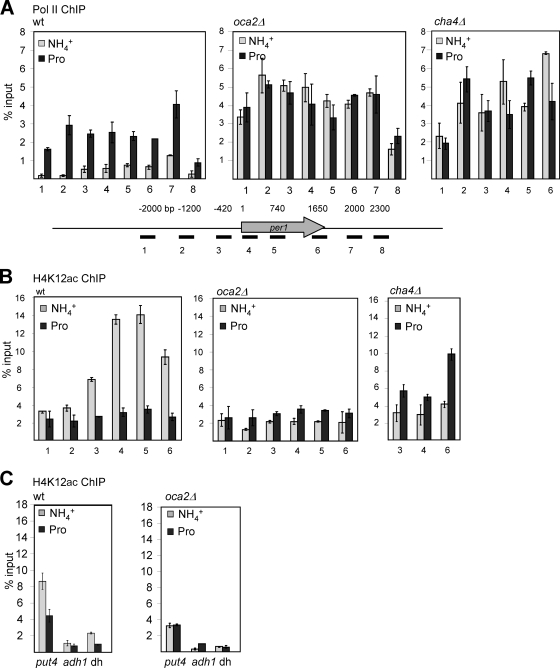

The Pol II distribution at per1 was assessed using ChIP analysis. Wt cells grown in ammonia showed a low level of Pol II-associated chromatin starting between 1 and 0.5 kb upstream of the translation start codon and decreasing at about 500 bp beyond the stop codon (Fig. 4 A, left). In contrast, Pol II levels at chromatin isolated from wt cells grown in proline were increased 3- to 5-fold. Significantly, Pol II was also detectable 2 kb upstream of the AUG (probes 1 and 2).

FIG. 4.

The binding of Pol II increases and H4K12 acetylation decreases upon transcriptional activation of per1. (A) Pol II ChIP of wt, oca2Δ, and cha4Δ cells grown in EMM containing either ammonia or proline (Pro). Pol II was precipitated using an antibody against the CTD of Pol II (H8). The positions of the PCR primers across per1 are indicated. ChIP signal values are expressed as percentages of input DNA corrected for the no-antibody control. The data shown represent the average and SEM of at least three independent experiments. (B) H4K12ac ChIP of wt, oca2Δ, and cha4Δ cells using anti-H4K12ac antibody. Primer pairs and quantification are the same as in panel A. (C) H4K12ac ChIP of wt and oca2Δ cells using primer pairs specific for the ORFs of put4 and adh1 and the centromeric-repeat dh.

The Pol II profile for chromatin from oca2Δ cells grown in ammonia was similar to that of wt cells grown in proline, with high levels of binding over the per1 coding and upstream regions (Fig. 4A, middle). oca2Δ cells grown in proline showed similar high levels of Pol II binding, particularly in the region 2 kb upstream of the AUG (probe 1). These results are consistent with the Northern blot data (Fig. 3A). In particular, the per1 5′-extended transcript B appears to correlate with the higher Pol II ChIP signals. Chromatin from cha4Δ cells grown in either ammonia or proline gave a Pol II profile similar to that of oca2Δ cells, except that Pol II levels over probe 1 were lower (Fig. 4A, right). Overall, the results from these ChIP analyses suggest that the changes in the per1 mRNA profile reflect altered Pol II distribution and transcription.

A likely explanation for how Pol II transcription of per1 is regulated is through changes of the chromatin structure. Oca2 interacts with Prw1, a subunit of the Clr6 HDAC, and with the histone acetyltranferase Hat1 (see Fig. 1D). Clr6 deacetylates several lysines in histones 3 and 4, including H4K12, and this residue is also a main substrate for Hat1 (34, 38). Using ChIP analysis, we found that the level of H4K12 acetylation was increased when wt cells were grown in ammonia compared to growth in proline (Fig. 4B, left). A region starting 2 kb upstream of the translation start site and spanning the ORF showed 1.5- to 4-fold-higher levels of H4K12 acetylation in the presence of ammonia than in the presence of proline, with the difference being most pronounced over the ORF. In contrast, H4K12 acetylation was low in the oca2Δ strain for both nitrogen sources (Fig. 4B, middle). The levels of histone H3 at per1 did not change significantly between the two growth conditions and strains, indicating that the difference in H4K12 acetylation was not caused by a change in overall histone levels (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Thus, at per1, increased acetylation of H4K12 correlates with transcriptional repression of the upstream transcript.

We also looked at the profile of H4K12 acetylation in cha4Δ cells (Fig. 4B, right). In the presence of ammonia, levels of H4K12 acetylation over the per1 ORF were lower than the in wt strain, similar to the oca2Δ strain. However, when cha4Δ cells were grown in proline, they exhibited an increase of H4K12 acetylation compared to wt and oca2Δ cells. Overall, these results demonstrate that in wt cells, transcriptional activation of per1 in response to proline correlates with deacetylation of H4K12 and with the appearance of longer, 5′-extended transcripts. In the oca2Δ strain, these effects were constitutive irrespective of the nitrogen source. cha4Δ cells showed deacetylation and activation of per1 under repressing conditions, similar to oca2Δ cells, but failed to do so under derepressing conditions.

H4K12 acetylation was also analyzed at the put4 gene (Fig. 4C). H4K12 acetylation at put4 was increased in wt cells using ammonia compared to proline (Fig. 4C, left). Again, oca2Δ cells gave similar lower levels of H4K12 acetylation at this locus in both nitrogen sources (Fig. 4C, right). In both strains, H4K12 acetylation at the adh1 locus did not change significantly, indicating that the effects seen at per1 and put4 are gene specific. Furthermore, H4K12 acetylation at the centromeric repeat was slightly higher in wt cells grown in ammonia than in those grown in proline, whereas they were the same in oca2Δ cells for both nitrogen sources (Fig. 4C, probe dh).

Clr6 is required for per1 chromatin acetylation.

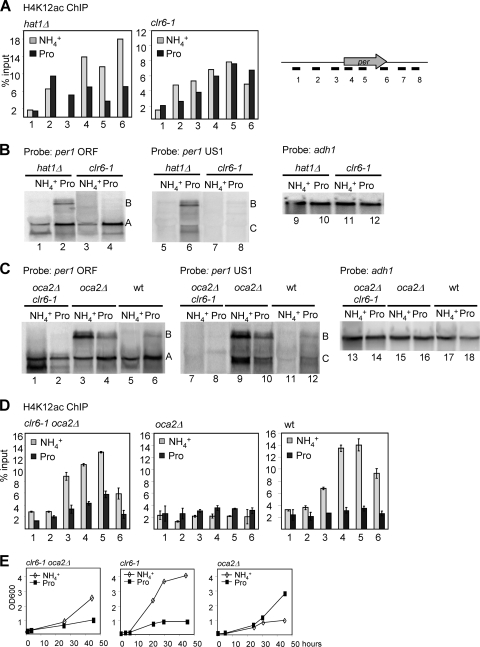

The different levels of acetylated H4K12 for per1 could be due to a change in deacetylation or acetylation, or both. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined the H4K12 acetylation profile of per1 in strains lacking hat1 or carrying the clr6-1 mutant allele. As shown in Fig. 5 A, ChIP analysis of chromatin from hat1Δ cells showed a H4K12ac profile similar to that of wt cells, with higher levels of acetylation in ammonia than in proline (Fig. 5A, left). In contrast, clr6-1 cells showed little difference in H4K12 acetylation between ammonia and proline (Fig. 5A, right). Especially over probes 5 and 6, which cover the middle and the 3′ end of the per1 ORF, H4K12 acetylation was as high or even higher in clr6-1 cells grown in proline than in those grown in ammonia. Note that the absolute levels of ChIP signal were lower in clr6-1 than in the wt, as shown in Fig. 4B, likely due to differences in the genetic background. Furthermore, when grown in proline, the clr6-1 mutant did not produce transcripts B and C (Fig. 5B, left and middle). In RNA isolated from a hat1Δ strain, however, transcripts B and C were detectable, as in wt cells (Fig. 5B, left and middle). These results suggest that Clr6, but not Hat1, is involved in deacetylation of H4K12 at the per1 locus and in expression of transcript B. Consistently, clr6-1 mutant cells displayed a growth defect with proline as the nitrogen source, whereas hat1Δ cells grew normally (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 5.

Clr6 is required for the deacetylation of per1 and for the accumulation of 5′-extended transcripts. (A) H4K12ac ChIP of hat1Δ and clr6-1 cells grown in EMM containing either ammonia or proline. The positions of the PCR primers across the per1 locus are indicated. (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from hat1Δ and clr6-1 cells grown in ammonia or proline, respectively. The probes were specific for the ORF of per1 (left), the upstream region of per1 (middle), and the ORF of adh1 (right). (C) As for panel B, but using RNA isolated from oca2Δ clr6-1, oca2Δ, and wt cells. (D) H4K12ac ChIP analysis. oca2Δ clr6-1, oca2Δ, and wt cells were grown in either ammonia or proline, and H4K12ac distribution was analyzed using anti-H4K12ac antibody and per1-specific primer pairs as indicated. The error bars indicate SEM. (E) Growth phenotypes of oca2Δ clr6-1, clr6-1, and oca2Δ cells.

The constitutive expression of transcript B and the reduced levels of H4K12 acetylation that we observed in oca2Δ cells may therefore be due to increased Clr6 activity in the strain. To test this assumption, we examined per1 expression and H4K12 acetylation in an oca2Δ strain also carrying the clr6-1 allele. In contrast to oca2Δ, the oca2Δ clr6-1 double mutant did not produce transcripts B and C when grown in ammonia, suggesting that Clr6 activity is responsible for their aberrant expression in oca2Δ (Fig. 5C, compare lanes 1 and 7 with lanes 3 and 9). Furthermore, H4K12 acetylation at per1 was higher in oca2Δ clr6-1 than in oca2Δ cells, indicating that reduced H4K12 acetylation in oca2Δ cells grown in ammonia is due to increased Clr6 activity (Fig. 5D, compare left and middle). This result indicates that Oca2 and Clr6 have opposing effects on per1 expression, with Oca2 acting as a repressor and Clr6 as an activator. Furthermore, because clr6-1 is epistatic to oca2Δ, this suggests that Oca2 controls Clr6 activity in ammonia. Consistent with this hypothesis, the oca2Δ clr6-1 strain had a growth phenotype similar to that of clr6-1, with better growth in ammonia than in proline (Fig. 5E).

RNAi-mediated silencing factors are involved in per1 repression.

Oca2 also interacts with the RITS component Ago1 (Fig. 1D), which promotes silencing in heterochromatic regions, including centromeres (12). Moreover, per1 is located adjacent to the left outermost centromeric repeat on chromosome 1 (Fig. 6 A), and ago1Δ cells grow more slowly in ammonia than in proline, similar to oca2Δ cells (Fig. 1B). All of these observations suggest that Ago1 and the heterochromatic silencing machinery may be involved in regulation of per1 expression. Furthermore, Northern blot analysis revealed that in cells lacking ago1, transcripts B and C are expressed under noninducing conditions, as in oca2Δ cells (Fig. 6B). Ago1 functions together with Dcr1, an RNase III enzyme, and with Clr4, a histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferase, both involved in heterochromatic silencing (12). clr4Δ cells were therefore tested and shown by Northern blot analysis to exhibit an aberrant per1 expression profile similar to that of ago1Δ and oca2Δ cells (Fig. 6B). Growth of dcr1Δ cells was too poor in these nitrogen sources to examine per1 expression. Using a Flag-tagged ago1 strain, we found that in the presence of ammonia, low levels of Ago1 localized to per1 chromatin and that this association increased when the cells were grown in proline (Fig. 6C). Under these same conditions, more Ago1 also localized to the centromeric repeats (Fig. 6C, probe dh). Mutants in the heterochromatic silencing machinery lead to an accumulation of centromeric transcripts (14, 48). Using RT-PCR with primers specific for the centromeric dh repeats, we observed an increase of centromeric transcripts in oca2Δ cells (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that Ago1 and the heterochromatic silencing machinery are involved in the regulation of per1 and that the repression of per1 and the centromeric repeats may be connected. However, using an antibody against dimethylated H3K9dime, a histone mark associated with silenced centromeric chromatin, we did not detect any significant changes in the levels or in the distribution of H3K9dime at per1 in oca2Δ cells (data not shown), indicating that this histone modification is not involved in per1 regulation. Given the involvement of RNAi factors in per1 regulation, we also tested whether antisense transcription might play a role in per1 regulation. Using sense RNA probes to the ORF and the upstream region of per1, we detected antisense per1 transcripts in wt cells (not shown) and in rrp6Δ and oca2Δ cells (Fig. 6E). Absence of the exosome subunit Rrp6 did not lead to an accumulation of antisense transcripts (not shown). However, changing the nitrogen source from ammonia to proline or the absence of oca2 did not correlate with a significant alteration in the levels or pattern of antisense transcripts, suggesting that regulation of per1 does not employ an antisense or small interfering RNA (siRNA)-based mechanism.

DISCUSSION

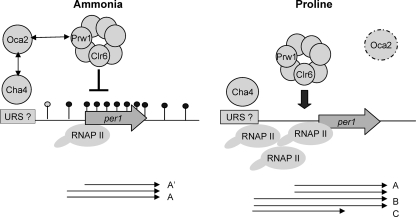

We provide evidence for the transcriptional regulation of per1 in response to the quality of the nitrogen source. We show that in the presence of ammonia, when per1 expression is low, a transcript of about 2.8 kb is synthesized, and a region encompassing the coding and upstream regions of per1 is acetylated. Transcriptional activation of per1 by proline leads to transcription initiation from an additional upstream start site and correlates with deacetylation of the per1 locus. Transcriptional activation and histone deacetylation of per1 are constitutive in cells lacking the serine/threonine kinase gene oca2 but are reduced in clr6-1 cells under inducing conditions, suggesting that Oca2 and Clr6 act in opposite directions as a repressor and activator, respectively, of per1 expression. In an oca2Δ clr6-1 double mutant, stimulation of per1 and H4K12 deacetylation under noninducing conditions are no longer observed, suggesting that Clr6 acts downstream of Oca2 and that the phenotype of oca2Δ cells may be due to aberrant Clr6 activity. Oca2 interacts with the predicted transcriptional activator Cha4, as well as with Ago1, a factor involved in heterochromatin silencing. Cha4 appears to be required for both repression and activation of per1. As with oca2, loss of ago1 leads to activation of per1 under repressing conditions, suggesting that Ago1 acts as a repressor of the per1 gene.

These observations can be tied together by the following model (Fig. 7) . If ammonia is available, Oca2 represses Clr6 activity, possibly through interaction with Prw1. As a result, H4K12 actylation at per1 is high, allowing only expression of transcript A. This may be sufficient to produce limited amounts of permease protein required for the import of amino acids for anabolic purposes. When cells are grown in proline, levels of Oca2 protein are reduced, analogous to the oca2Δ strain. As a result, Clr6 activity is no longer repressed, which leads to H4K12 deacetylation at per1, recruitment of Pol II to the upstream initiation site, and synthesis of 5′-extended transcripts. It may be that the longer per1 mRNA 5′ UTR contains cis-acting signals that allow improved binding of the translation machinery and hence more efficient protein synthesis. Transcriptional induction by proline would therefore involve not only increased levels of per1 transcription, but also the production of translationally more competent transcripts, ensuring that the cell produces enough permease protein for the efficient import of proline for catabolic use as a nitrogen source. In this model, Clr6 deacetylates per1 and surrounding regions in a nontargeted way when cells use proline. Only when ammonia becomes available does the activity of Clr6 become locally restricted at per1 through targeted recruitment of the repressor Oca2. Deacetylation and activation would thus be the default pathway for per1 expression. This model is attractive, as in the natural habitat of S. pombe, proline is the most abundant nitrogen source (18).

FIG. 7.

Model for transcriptional regulation of per1 by Oca2, Clr6, and Cha4. See the text for details. RNAP II, Pol II.

Oca2 may be recruited to per1 in ammonia via interaction with Cha4, which in turn binds to upstream regulatory sequences through its Zn finger domain. In the presence of proline, Cha4 may recruit a different, per1-activating protein. Cha4 would thus act as a corepressor of per1 expression in ammonia but as a coactivator in proline, explaining the opposite phenotypes of the cha4Δ strain in the two nitrogen sources. A possible candidate for this per1-activating protein could be the SWI/SNF remodeling complex, as in S. cerevisiae, Cha4 recruits SWI/SNF as a coactivator of SRG1 transcription (28). Preliminary evidence indicates that Snf22, a component of the SWI/SNF complex in S. pombe, may indeed be involved in activation of per1, as a snf22Δ mutant strain showed a reduction in upstream start site selection in proline (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Ago1 may act as a repressor of per1 expression under noninducing conditions (see below).

Role of histone deacetylation in gene activation.

We found that clr6-1 negatively affects per1 expression, suggesting that Clr6 acts as an activator of per1 transcription. This is in agreement with a previous report that investigated the global effects of clr6-1 on gene expression (14). However, another genome-wide study found per1 to be upregulated in clr6-1 (52). A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that in the latter studies rich medium was employed for cell growth, which may trigger a different transcriptional response than minimal medium, used by Hansen et al. (14) and in this study.

Histone deacetylation has traditionally been associated with transcription repression. On a global level, this is true, as shown by genome-wide analysis of enzymatic activities and gene expression profiling (36, 52). However, several reports investigating specific genes have provided evidence that histone deacetylation can also activate transcription. In S. cerevisiae, Rpd3 has been shown to be directly required for transcriptional activation of osmoresponsive, DNA damage-inducible, and anaerobic genes (10, 43, 44). In response to the corresponding stimuli, Rpd3 is recruited to and deacetylates the promoters of these genes. Rpd3, together with the related HDAC Hos2, also plays a positive role in transcription of the GAL genes, but here, the coding regions are affected (49).

In this study, we found that histone deacetylation at per1 correlated with transcriptional activation of per1, indicating an activating role of Clr6. Because clr6-1 showed a defect in both deacetylation and transcriptional activation, deacetylation of per1 seems to be a cause for, and not an effect of, increased transcription. Importantly, deacetylation of per1 leads not only to increased transcription, but also to the use of an upstream initiation site. Possibly, histone deacetylation of per1 induces chromatin remodeling over upstream and coding regions, for instance, by SWI/SNF. This could make alternative initiation sites accessible, as well as promote more efficient Pol II elongation over coding regions.

Oca2 also interacts with the type B histone acetyltransferase Hat1; however, in a hat1Δ strain, we did not detect changes in H4K12 acetylation or a defect in per1 expression. Perhaps Hat1 may be required for genes other than per1, for instance, genes that are located in the subtelomeric regions. Similarly, in S. cerevisiae, Hat1 has been implicated in telomeric silencing (23).

Gene regulation through upstream initiation.

Gene regulation through the use of upstream transcription initiation sites has recently been reported for two other S. pombe genes, tco1 and fbp1 (16, 42). In the case of fbp1, glucose starvation-induced activation leads first to the synthesis of 5′-extended noncoding transcripts and only later to accumulation of the main, shorter fbp1 transcript. This study showed that passage of Pol II through the fbp1 upstream region is required for progressive conversion of the fbp1 chromatin into an open configuration, allowing Pol II to initiate from the genuine downstream initiation site (16). In the case of tco1, low oxygen shifts transcription initiation to an upstream site, which leads to downregulation of tco1. The resulting longer transcript is translationally silent, as it fails to associate with polysomes, possibly due to formation of inhibitory secondary structures in its 5′ UTR (42). We do not know whether transcript B is translated differently from the shorter transcript A. However, as more Per1 protein is required when proline is used as a nitrogen source (46), it seems plausible that the longer mRNA is translationally more competent. The possibility that transcript B encodes a different protein is excluded, as its extended 5′ UTR does not possess a continuous reading frame (data not shown).

Connection between transcription initiation and termination.

Oca2 was originally isolated as a multicopy suppressor of a transcription termination mutant (2; Azad and Proudfoot, unpublished). However, the role of Oca2 in transcription termination has remained elusive. It may be that Oca2 is involved in both transcription initiation and termination. A similar role in different stages of transcription was shown for the S. cerevisiae chromatin-remodeling proteins Chd1, Isw1, and Isw2. Depending on which gene they act on, these proteins can modulate the association of initiation factors with the promoter, the release of Pol II into productive elongation, or the pausing and release of the polymerase at the terminator (1, 32). However, it is also possible that complementation of the transcription termination mutant by overexpressing oca2 was indirect. The screen that led to the isolation of oca2 employed a modified ura4 gene containing an intronic terminator and selected for clones that revert from uracil prototrophy to auxotrophy. Thus, it may be that complementation by overexpressed oca2 was due to reduced expression of a transporter gene involved in uracil metabolism rather than restored ura4 transcription termination.

Genome-wide function of Oca2.

Expression of Oca2 is upregulated as part of the core environmental-stress response (8a), which suggests that Oca2 functions in a variety of stress response pathways, one of them possibly being changes in nutrient availability. Our whole-genome expression analysis found that loss of oca2 leads to upregulation of genes encoding membrane transporter proteins that localize near telomeric regions. A previous report showed that nitrogen starvation-responsive genes are clustered in the subtelomeric regions (29). Thus, it appears that proline or loss of oca2 triggers a transcriptional response related to nitrogen starvation. Importantly, the upregulated genes in oca2Δ cells overlap with genes downregulated in clr6-1 mutants, notably, per1 (14). This study also demonstrated that the upregulated genes in oca2Δ cells showed significant overlap with the genes induced in clr1 and clr3 mutants, silencing proteins that act redundantly with the RNAi pathway (14).

Interconnection of Oca2 with Cha4 and Ago1.

We have demonstrated that Oca2 interacts with Cha4, a zinc finger protein, and with Ago1, a factor involved in RNAi-induced transcriptional silencing. Cha4 is related to the S. cerevisiae DNA-binding proteins Cha4 and Tea1; it is thus likely that in S. pombe Cha4 binds to regulatory DNA sequences as well. In S. cerevisiae, Cha4 has been shown to act as an activator of the serine-responsive gene CHA1, encoding a serine deaminase (17), and of the regulatory RNA SRG1, which in turn represses expression of the serine-biosynthetic gene SER3 (28). This raises the possibility that S. pombe Cha4 may also act as a regulator of genes involved in amino acid metabolism. Interestingly, the CHA1 promoter is located 2 kb downstream of the silent-mating-type locus HML, reminiscent of the proximity of per1 to the centromeric region, and repression of CHA1 under noninducing conditions requires Sir4, a factor involved in chromatin silencing in S. cerevisiae (30). In this study, we observed that Oca2 interacts with Ago1 and that ago1Δ and clr4Δ cells derepress per1 under noninducing conditions. Also, Ago1 localizes to per1, suggesting that Ago1 and heterochromatic silencing may be involved in per1 regulation. Since per1 is located close to the left outermost centromeric repeat on chromosome 1 and oca2Δ cells display an accumulation of centromeric transcripts, it is possible that per1 regulation may be controlled by a position effect due to its proximity to the centromere. Likewise, the other upregulated genes in oca2Δ may be controlled through their positions in the subtelomeric regions. Mutants in the S. pombe RNAi and the chromatin-silencing machineries have all been shown to affect expression of a large number of endogenous genes, including the mat2-P and mat3-M silent loci in the mating-type region and many genes that are clustered in the subtelomeric regions (14, 47). Likewise, heterologous genes placed within or adjacent to heterochromatic locations are subject to transcriptional repression (13, 48). However, neither H3K9me, the histone modification typically found in heterochromatic regions, nor antisense transcription appears to correlate with per1 regulation. Therefore, per1 regulation seems not to employ an siRNA-based silencing mechanism; instead, Ago1 and Clr4 may play alternative roles.

General connections of Oca2 with Tor and nutrient-dependent growth.

Rapamycin binds to TOR, a universally conserved kinase that couples nutrient availability to cell growth. In budding yeast and higher eukaryotes, inhibition of TOR by rapamycin triggers a variety of transcriptional and translational responses, similar to nutrient starvation. In fission yeast, inhibition of Tor by rapamycin leads to the reduced expression of amino acid permease genes, including per1 and put4 (50). It is possible that the positive effect of rapamycin on the growth of oca2Δ is due to downregulation of these genes in the presence of the drug. In S. cerevisiae, rapamycin affects transcription of target genes through changes in the recruitment of Rpd3 (19, 37). Moreover, in S. pombe, tor1Δ mutants show an overlapping gene expression pattern like clr6-1 mutants (41), suggesting that Tor and Clr6 may act in the same pathway. It remains to be shown whether rapamycin affects recruitment of Clr6 and histone deactylation at per1.

Overall, our studies of per1 indicate that S. pombe has evolved a sophisticated network of gene regulation through chromatin modification to control the expression of membrane transporter proteins and the consequent utilization of nitrogen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Karl Ekwall, Robin Allshire, Marc Bühler, Danesh Moazed, Chris Norbury, Keith Gull, Fred Winston, and Stefania Castagnetti for strains and reagents. We also thank Jurgi Camblong for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by Programme Grants from the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust to N.J.P., and a Cancer Research United Kingdom grant to J.B. S.M. was supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation Advanced Researchers fellowship.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 April 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alén, C., N. A. Kent, H. S. Jones, J. O'Sullivan, A. Aranda, and N. J. Proudfoot. 2002. A role for chromatin remodeling in transcriptional termination by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell 10:1441-1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranda, A., and N. Proudfoot. 2001. Transcriptional termination factors for RNA polymerase II in yeast. Mol. Cell 7:1003-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bähler, J., J. Q. Wu, M. S. Longtine, N. G. Shah, A. McKenzie III, A. B. Steever, A. Wach, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14:943-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson, L. J., J. A. Phillips, Y. Gu, M. R. Parthun, C. S. Hoffman, and A. T. Annunziato. 2007. Properties of the type B histone acetyltransferase Hat1:H4 tail interaction, site preference, and involvement in DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 282:836-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bimbó, A., Y. Jia, S. L. Poh, R. K. Karuturi, N. den Elzen, X. Peng, L. Zheng, M. O'Connell, E. T. Liu, M. K. Balasubramanian, and J. Liu. 2005. Systematic deletion analysis of fission yeast protein kinases. Eukaryot. Cell 4:799-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buker, S. M., T. Iida, M. Bühler, J. Villén, S. P. Gygi, J.-I. Nakayama, and D. Moazed. 2007. Two different Argonaute complexes are required for siRNA generation and heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:200-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camblong, J., N. Iglesias, C. Fickentscher, G. Dieppois, and F. Stutz. 2007. Antisense RNA stabilization induces transcriptional gene silencing via histone deacetylation in S. cerevisiae. Cell 131:706-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrozza, M. J., B. Li, L. Florens, T. Suganuma, S. K. Swanson, K. K. Lee, W. J. Shia, S. Anderson, J. Yates, M. P. Washburn, and J. L. Workman. 2005. Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell 123:581-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Chen, D., W. M. Toone, J. Mata, R. Lyne, G. Burns, K. Kivinen, A. Brazma, N. Jones, and J. Bahlar. 2003. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:214-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Craene, J. O., O. Soetens, and B. Andre. 2001. The Npr1 kinase controls biosynthetic and endocytic sorting of the yeast Gap1 permease. J. Biol. Chem. 276:43939-43948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Nadal, E., M. Zapater, P. M. Alepuz, L. Sumoy, G. Mas, and F. Posas. 2004. The MAPK Hog1 recruits Rpd3 histone deacetylase to activate osmoresponsive genes. Nature 427:370-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Gray, W. M., and J. S. Fassler. 1996. Isolation and analysis of the yeast TEA1 gene, which encodes a zinc cluster Ty enhancer-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Bol. 16:347-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grewal, S. I., M. J. Bonaduce, and A. J. Klar. 1998. Histone deacetylase homologs regulate epigenetic inheritance of transcriptional silencing and chromosome segregation in fission yeast. Genetics 150:563-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grewal, S. I., and S. Jia. 2007. Heterochromatin revisited. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8:35-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall, I. M., G. D. Shankaranarayana, K. Noma, N. Ayoub, A. Cohen, and S. I. Grewal. 2002. Establishment and maintenance of a heterochromatin domain. Science 297:2232-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen, K. R., G. Burns, J. Mata, T. A. Volpe, R. A. Martienssen, J. Bahler, and G. Thon. 2005. Global effects on gene expression in fission yeast by silencing and RNA interference machineries. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:590-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi, T., Y. Fujita, O. Iwasaki, Y. Adachi, K. Takahashi, and M. Yanagida. 2004. Mis16 and Mis18 are required for CENP-A loading and histone deacetylation at centromeres. Cell 118:715-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirota, K., T. Miyoshi, K. Kugou, C. S. Hoffman, T. Shibata, and K. Ohta. 2008. Stepwise chromatin remodelling by a cascade of transcription initiation of non-coding RNAs. Nature 456:130-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmberg, S., and P. Schjerling. 1996. Cha4p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae activates transcription via serine/threonine response elements. Genetics 144:467-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang, H. L., and M. C. Brandriss. 2000. The regulator of the yeast proline utilization pathway is differentially phosphorylated in response to the quality of the nitrogen source. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:892-899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey, E. L., A. F. Shamji, B. E. Bernstein, and S. L. Schreiber. 2004. Rpd3p relocation mediates a transcriptional response to rapamycin in yeast. Chem. Biol. 11:295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter, T., and G. D. Plowman. 1997. The protein kinases of budding yeast: six score and more. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irvine, D. V., M. Zaratiegui, N. H. Tolia, D. B. Goto, D. H. Chitwood, M. W. Vaughn, L. Joshua-Tor, and R. A. Martienssen. 2006. Argonaute slicing is required for heterochromatic silencing and spreading. Science 313:1134-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston, S. D., S. Enomoto, L. Schneper, M. C. McClellan, F. Twu, N. D. Montgomery, S. A. Haney, J. R. Broach, and J. Berman. 2001. CAC3(MSI1) suppression of RAS2(G19V) is independent of chromatin assembly factor I and mediated by NPR1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1784-1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly, T. J., S. Qin, D. E. Gottschling, and M. R. Parthun. 2000. Type B histone acetyltransferase Hat1p participates in telomeric silencing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7051-7058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keogh, M. C., S. K. Kurdistani, S. A. Morris, S. H. Ahn, V. Podolny, S. R. Collins, M. Schuldiner, K. Chin, T. Punna, N. J. Thompson, C. Boone, A. Emili, J. S. Weissman, T. R. Hughes, B. D. Strahl, M. Grunstein, J. F. Greenblatt, S. Buratowski, and N. J. Krogan. 2005. Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell 123:593-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurdistani, S. K., and M. Grunstein. 2003. Histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:276-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurdistani, S. K., D. Robyr, S. Tavazoie, and M. Grunstein. 2002. Genome-wide binding map of the histone deacetylase Rpd3 in yeast. Nat. Genet. 31:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyne, R., G. Burns, J. Mata, C. J. Penkett, G. Rustici, D. Chen, C. Langford, D. Vetrie, and J. Bahler. 2003. Whole-genome microarrays of fission yeast: characteristics, accuracy, reproducibility, and processing of array data. BMC Genomics 4:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martens, J. A., P. Y. Wu, and F. Winston. 2005. Regulation of an intergenic transcript controls adjacent gene transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 19:2695-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mata, J., R. Lyne, G. Burns, and J. Bahler. 2002. The transcriptional program of meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. Nat. Genet. 32:143-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreira, J. M., and S. Holmberg. 1998. Nucleosome structure of the yeast CHA1 promoter: analysis of activation-dependent chromatin remodeling of an RNA-polymerase-II-transcribed gene in TBP and RNA pol II mutants defective in vivo in response to acidic activators. EMBO J. 17:6028-6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno, S., A. Klar, and P. Nurse. 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194:795-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morillon, A., N. Karabetsou, J. O'Sullivan, N. Kent, N. Proudfoot, and J. Mellor. 2003. Isw1 chromatin remodeling ATPase coordinates transcription elongation and termination by RNA polymerase II. Cell 115:425-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicolas, E., T. Yamada, H. P. Cam, P. C. Fitzgerald, R. Kobayashi, and S. I. Grewal. 2007. Distinct roles of HDAC complexes in promoter silencing, antisense suppression and DNA damage protection. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:372-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parthun, M. R. 2007. Hat1: the emerging cellular roles of a type B histone acetyltransferase. Oncogene 26:5319-5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pidoux, A., B. Mellone, and R. Allshire. 2004. Analysis of chromatin in fission yeast. Methods 33:252-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robyr, D., Y. Suka, I. Xenarios, S. K. Kurdistani, A. Wang, N. Suka, and M. Grunstein. 2002. Microarray deacetylation maps determine genome-wide functions for yeast histone deacetylases. Cell 109:437-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohde, J. R., and M. E. Cardenas. 2003. The TOR pathway regulates gene expression by linking nutrient sensing to histone acetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:629-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rundlett, S. E., A. A. Carmen, R. Kobayashi, S. Bavykin, B. M. Turner, and M. Grunstein. 1996. HDA1 and RPD3 are members of distinct yeast histone deacetylase complexes that regulate silencing and transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:14503-14508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmid, M., and T. H. Jensen. 2008. The exosome: a multipurpose RNA-decay machine. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33:501-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt, A., T. Beck, A. Koller, J. Kunz, and M. N. Hall. 1998. The TOR nutrient signalling pathway phosphorylates NPR1 and inhibits turnover of the tryptophan permease. EMBO J. 17:6924-6931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schonbrun, M., D. Laor, L. Lopez-Maury, J. Bahler, M. Kupiec, and R. Weisman. 2009. TOR complex 2 controls gene silencing, telomere length maintenance, and survival under DNA-damaging conditions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:4584-4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sehgal, A., B. T. Hughes, and P. J. Espenshade. 2008. Oxygen-dependent, alternative promoter controls translation of tco1+ in fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:2024-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sertil, O., A. Vemula, S. L. Salmon, R. H. Morse, and C. V. Lowry. 2007. Direct role for the Rpd3 complex in transcriptional induction of the anaerobic DAN/TIR genes in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:2037-2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma, V. M., R. S. Tomar, A. E. Dempsey, and J. C. Reese. 2007. Histone deacetylases RPD3 and HOS2 regulate the transcriptional activation of DNA damage-inducible genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:3199-3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tallada, V. A., R. R. Daga, C. Palomeque, A. Garzon, and J. Jimenez. 2002. Genome-wide search of Schizosaccharomyces pombe genes causing overexpression-mediated cell cycle defects. Yeast 19:1139-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ter Schure, E. G., N. A. van Riel, and C. T. Verrips. 2000. The role of ammonia metabolism in nitrogen catabolite repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:67-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thon, G., and A. J. Klar. 1992. The clr1 locus regulates the expression of the cryptic mating-type loci of fission yeast. Genetics 131:287-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volpe, T. A., C. Kidner, I. M. Hall, G. Teng, S. I. Grewal, and R. A. Martienssen. 2002. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science 297:1833-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, A., S. K. Kurdistani, and M. Grunstein. 2002. Requirement of Hos2 histone deacetylase for gene activity in yeast. Science 298:1412-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weisman, R., I. Roitburg, T. Nahari, and M. Kupiec. 2005. Regulation of leucine uptake by tor1+ in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is sensitive to rapamycin. Genetics 169:539-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Win, T. Z., A. L. Stevenson, and S. W. Wang. 2006. Fission yeast Cid12 has dual functions in chromosome segregation and checkpoint control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:4435-4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wirén, M., R. A. Silverstein, I. Sinha, J. Walfridsson, H. M. Lee, P. Laurenson, L. Pillus, D. Robyr, M. Grunstein, and K. Ekwall. 2005. Genomewide analysis of nucleosome density histone acetylation and HDAC function in fission yeast. EMBO J. 24:2906-2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.