Abstract

Purpose of Review

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are mediators of post-transcriptional gene expression that likely regulate most biological pathways and networks. The study of miRNAs is a rapidly emerging field; recent findings have revealed a significant role for miRNAs in atherosclerosis and lipoprotein metabolism, which will be described in this review.

Recent Findings

The discovery of miRNA gene regulatory mechanisms contributing to endothelial integrity, macrophage inflammatory response to atherogenic lipids, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, and cholesterol synthesis are described. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that miRNAs may play a role in mediating the beneficial pleiotropic effects observed with statin-based lipid lowering therapies. New modifications to miRNA mimetics and inhibitors, increasing targeting efficacy and cellular uptake, will likely enable future therapies to exploit miRNA gene regulatory networks.

Summary

At this time, the applicability and full potential of miRNAs in clinical practice is unknown. Nonetheless, recent advances in miRNA delivery and inhibition hold great promise of a tremendous clinical impact in atherosclerosis and cholesterol regulation.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Lipoprotein, Atherosclerosis, Metabolism

Introduction

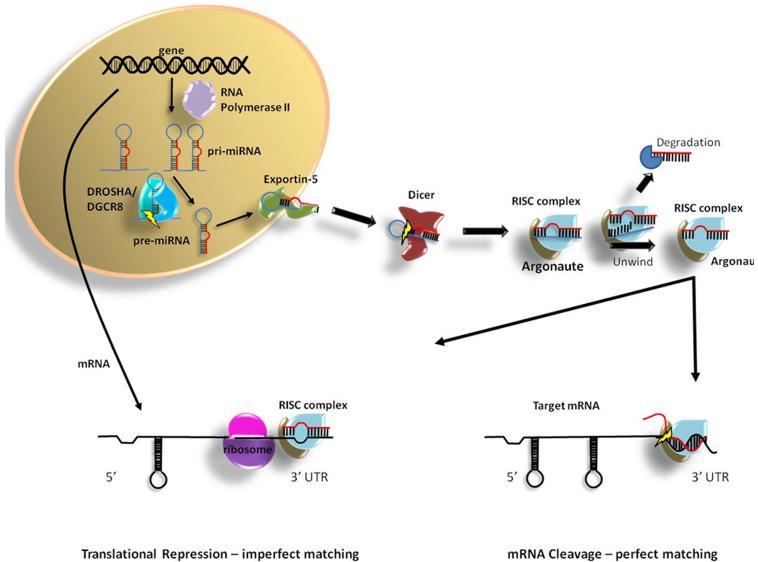

Since their discovery in 1993, the importance of microRNAs (miRNA) in gene regulaton has steadily gained appreciation and now miRNA biology has exploded into a massive swell of interests with enormous range and potential in almost every biological discipline (1-2). miRNAs are short (19-23nt) non-coding RNAs, transcribed from both intergenic and genic regions of the genome (3-4). miRNAs can be co-transcribed with host-gene promoters or posses their own specific promoter (5). The biogenesis of these small regulatory RNA molecules start out as primary transcripts termed pri-miRNA (6) (Fig.1). Intergenic miRNA promoters, specifically transcriptional start sites (TSS), have been mapped at distances from 1kb to as much as 100kb away from mature miRNA loci (7). A key aspect of initial pri-miRNA processing is the folding of specific regions into hairpin structures, as these long transcripts likely have extensive secondary structures. Multiple examples of polycistronic miRNA clustering, or multiple miRNAs on a single pri-miRNA, have been described (8). The essential hairpin structural domains of pri-miRNA are first processed in the nucleus by the RNAse III enzyme DROSHA and DGCR8 to produce pre-miRNAs, which are approximatel~65-75nts as a single dsRNA hairpin (9). Pre-miRNAs are then exported from the nucleus by the RanGTP-dependent exportin 5 enzyme (10). Once in the cytoplasm, pre-miRNAs are further processed by a second RNase III enzyme, DICER1, which recognizes dsRNA complexes and cleave ~22nt (two-full helical turns) from the non-stem-loop end of the pre-miRNA (11). The cleavage of the pre-miRNA hairpin by DICER1 is an essential step in the maturation of viable mature miRNA, and DICER1-dependency is a necessary requirement of novel miRNA discovery (12-13). To characterize the role of miRNAs in different cell types, differentation phenotypes, or pre- /post-natal conditions, DICER1 loss of functions studies are often utilized (14).

Figure 1. Biogenesis and targeting of mature miRNA.

The dsRNA miRNA complex, which is composed of the mature miRNA (miR) and its passenger strand (miR*), is unwound by helicase activities of the Argonaute (Ago) multi-protein complex, globally known as the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (15-17). Determination of the active (guide) strand is based upon simple energetics between strands at the 5′ ends of the dsRNA complex (18). The preferred guide strand is subsequently incorporated into the RISC complex by directly binding to the key protein component Ago (19). miRNA target sites generally occur within the mRNA’s 3′UTR; however, we now recognize that target sites can also occur in coding regions (open reading frame) and in 5′-UTR (20). Targeting can be achieved by both perfect and imperfect complementarity between the mature miRNA and the mRNA target. Unlike siRNAs, which binds to mRNAs with perfect complementarity, miRNAs usually only require consensus matching along the miRNA seed sequence (5′-bases 2-8) (21-22). Perfect (full) complementarity, extending out from the seed site along the first helical turn (11nt) of the miRNA:mRNA complex, results in direct cleavage of the mRNA; however, this is a rare phenomenon for miRNAs (23). Many types of seed matching have been described with different patterns of seed complementarity; including 7mer-m8, 7mer-A1, 6mer, offset 6mer and 3′compensatory (24). These seed sequence-based matches result in translational repression and can eventually result in mRNA degradation due to destabilization (25-26). Additionally, many other factors regulate miRNA targeting, including the flanking sequence of the target site, the location within the 3′UTR, and accessibility of the mRNA target site due to secondary structure and protein interference (27). Because we are now just beginning to fully understand and appreciate the intricate details of miRNAs, more is likely to be revealed in the future about how miRNAs recognize their targets.

Recently, mRNA target prediction programs (in silico) have undergone great improvements and multiple options are currently available (28-31). Mainly relying on sequence data, each algorithm provides lists and/or scores of potential mRNA targets by incorporating conservation and other alternative targeting factors. The most widely used target prediction program is TargetScan (targetscan.org) (28); however, many other programs are widely-used; including miRanda (microrna.org) (29), StarMir (sfold.wadsworth.org) (30), and PicTar (pictar.mdc-berlin.de) (31) among others. A current survey and summary of the multiple strategies of miRNA target prediction was recently released (32). Although prediction programs have made great strides recently, they are still not completely reliable; and functional and experimental testing is always advised.

Currently, 721 human and 579 mouse miRNAs (v14.0) are listed in the comprehensive miRNA database miRBase (miRBase.org) (33). As the list of miRNAs grows, there is a growing awareness of their potential and importance in the regulation of gene expression. Each individual miRNA can potentially target and repress many, possibly hundreds of different mRNAs. Furthermore, one gene (mRNA) can be under the repressive mechanism of multiple miRNAs, thus the regulation of genes by miRNAs can be viewed as a complex and interconnected network. Because complex metabolic pathways, such as lipid metabolism, are often coordinately regulated, by a variety of homeostatic mechanisms, recent studies have focused on the role of miRNAs in these processes.

In this review, we will discuss the recent advances of miRNA research associated with atherosclerosis and lipoprotein metabolism, as well as the current state of miRNA therapeutics and their potential in modulating cardiovascular disease.

miRNAs and Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a multi-factorial disease driven, in part, by chronic inflammation in response to cholesterol accumulation in the arterial wall (34). The first major event in the progression of the early atheroma is the loss of endothelial integrity. Endothelium dysfunction facilitates the sub-endothelial accumulation of cholesterol-bearing lipoproteins, compromises vasodilation, and is both pro-inflammatory and prothrombotic (35,36). A majority of what we understand about the role of miRNAs in endothelial cells comes from studies of angiogenesis. Endothelial migration studies, utilizing wound healing assays, revealed a significant role for let-7, miR-221, and miR-222 in endothelial function (13,14,37,38). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that miR-92a prohibits angiogenesis, while miR-126 sustains vascular integrity and promotes angiogenic signaling (39,40). Of note, key endothelial angiogenic determinants also participate in endothelial maintenance and integrity (41,42). To what degree these specific miRNAs confer between the two endothelial states has yet to be resolved. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells have been demonstrated to play an integral role in endothelial integrity due to their ability to reinforce the endothelium with new healthy endothelial cells to replace damaged or apoptotic cells (43,44). In a recent study, subjects with atherosclerosis, as defined by coronary artery disease (CAD), showed significantly higher expression of miR-221 and miR-222 in endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) compared to non-CAD subjects (45). Furthermore, miR-221/222 levels were observed to be inversely related to EPC levels, as CAD subjects had significantly less EPC numbers. Statins, inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, have previously been shown to increase circulating EPC numbers in subjects with CAD (46,47). Consistent with these observations, atorvastatin was shown to decrease miR-221 and miR-222 expression in EPCs (45). The implications of this study are of significant merit as they illuminate miRNAs as possible mediators of statins’ observed pleiotropic beneficial effects. Collectively, these studies suggest that miRNAs may have numerous roles in angiogenesis and endothelium integrity, both of which significantly contribute to the development and maturation of the atherosclerotic plaque.

Vascular hyperplasia and neointimal lesion formation results from rapid proliferation and growth of vascular cells, generally occurring after non-specific vascular injury. Neointimal lesions occur at sites of subclinical atherosclerosis but are also classical hallmarks of restenosis after stenting, angioplasty, endarterectomy, and arterial transplantation (48,49). Recent observations of miRNA profile changes in balloon-injury and carotid-ligation models have revealed dynamic flux of specific miRNAs in the arterial wall, as part of the larger proliferative response (50,51). Specifically, miR-125a, miR-125b, miR-133, miR-143, miR-145, miR-365 appear to be down-regulated, and miR-21, miR-146, miR-214, and miR-352 were observed to be up-regulated in neointimal formation models (50). Accordingly, these observations have led to loss of function knockdown experiments, demonstrating that miR-21 promotes proliferation and neointimal growth due to injury (50,52).

A significant contributor to vascular hyperplasia and neointimal formation is the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC). VSMC phenotypic switching from a contractile state to a proliferative state has arterial-wide ramifications to neointimal lesions and atherosclerotic plaques. The role of miRNAs in VSMC proliferation has been extensively but not exhaustively investigated (53-57). Recently, miR-145 has been demonstrated to be a key determinant in VSMC differentiation and phenotype (54,57), and to be down-regulated in both atherosclerosis and arterial-injury models (50,51). Together with miR-145, miR-143 has recently been shown to regulate the VSMC proliferative response to balloon-injury through alterations in cytoskeleton organization (58). miR-143 and miR-145, which are part of a polycistronic cluster, appear to promote the VSMC contractile (differentiated) phenotype and repress the proliferative (undifferentiated) response to injury (59). Not surprisingly, the role of miRNAs in regulating VSMC cell fate determination, plasticity, and neointimal formation has recently garnered great interest.

Atherosclerosis-induced sub-intimal thickening results from both cellular infiltration and acellular accumulation of basement membrane proteins. In early atheromotous plaques, inflammatory macrophages strive to alleviate the sub-endothelial accumulation of modified lipoproteins carrying cholesterol esters. As a consequence, the further recruitment and migration of cells induces chronic inflammation. Macrophages loaded with engulfed cholesterol have reduced mobility and ultimately the burden results in a complete gene profile and phenotypic conversion to foam cells (60). Changes to the miRNA profile during the macrophage to foam cell transition have not yet been characterized; however, significant differential expression of miRNAs were observed in human peripheral blood monocytes treated with oxidized LDL (61). Specifically, miR-125a-5p, miR-146a, miR-146b-5p, miR-155 and miR-9 were all significantly up-regulated in response to oxidized LDL. Interestingly, inhibition of endogenous miR-125a-5p levels in THP-1 cells significantly increased the secretion of inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β, TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-6) and increased the expression of macrophage scavenger receptors (LOX-1 and CD68), which resulted in increased lipid uptake (61). These data suggest that miR-125a-5p is anti-atherogenic in the macrophage. In addition to vascular cellular proliferation and inflammation, miRNAs likely play a significant role in other atherosclerotic processes, such as calcification, plaque vulnerability, and thrombosis; but have not yet been fully investigated.

miRNAs and Lipoprotein Metabolism

The primary functions of lipoproteins are the delivery of neutral lipids, such as triglycerides, and to a lesser degree cholesterol to peripheral cells and the removal of excess cellular cholesterol by the reverse cholesterol transport pathway (62). The epicenter of lipoprotein metabolism resides in the liver, which has been the focus of many miRNA studies (63-65). Hepatic miRNA profiles show that miR-122 is disproportionately more abundant than any other hepatic miRNA (66). In our studies in normal mouse livers, miR-122 was observed to be 3-fold more abundant than the second most (miR-790) and 12-fold more than the third most abundant miRNA (let-7) (unpublished data). Other studies have shown even greater differences between miR-122 expression and the next abundant hepatic miRNAs (67). For this reason, miR-122 was one of the first miRNAs to be characterized in hepatic function.

All cells synthesize cholesterol; however, the hepatic cholesterol biosynthetic pathway is unique in its role in overall homeostasis of systemic cholesterol. This is achieved by a hepatic network, which includes the regulation of cholesterol uptake and efflux, cholesterol storage via esterification, de novo cholesterol synthesis, and excretion of cholesterol as bile to the intestine (68). miRNAs are likely modulators of the hepatic cholesterol network by directly regulating cholesterol synthesis genes (mRNA) or indirectly through one of the other coordinated pathways. Multiple studies have shown that miR-122 is intricately involved in lipid metabolism (69,70); however, it does not appear that miR-122 directly targets the biosynthetic pathway (71). Overexpression of miR-122, with adenovirus, has been shown to increase the abundance of cholesterol synthesis genes (Hmgrcs1, Sqle, Dhcr7) in the liver, and in turn drive cholesterol synthesis (71). Multiple studies have investigated the loss of function or knockdown of miR-122 in the hepatocyte and/or liver; however, the direct targets of miR-122 that confers the assumed negative repression upon the cholesterol pathway are unknown. Consequences of miR-122 loss include a significant drop in cholesterol synthesis gene expression (mRNA), the reduction of plasma and hepatic cholesterol content, as well as an observed decrease in fatty acid synthesis (69). Results from a separate study, which used antagomirs of miR-122 to knockdown endogenous levels in mice, showed that many targets of miR-122 were up-regulated in response to miR-122 loss (71). Cholesterol synthesis genes, which are not predicted targets of miR-122, were down-regulated along with reduced serum cholesterol levels in antagomiR-122 mice (71). Further evidence will be needed to resolve the exact mechanism whereby miR-122 regulates the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway. Future studies will likely characterize the role of other miRNAs in directly repressing cholesterol synthesis, as well as functional targeting of other hepatic cholesterol network components; such as lipoprotein receptors, scavenger receptors, and genes in the bile acid pathway.

Future of miRNA Research and Therapeutics

Access to large-scale cost effective miRNA profiling is allowing researchers to quickly survey expression profiles and experimental miRNA fluxes. When coupled with miRNA-target prediction programs and gene expression profiles (mRNA), miRNA profiling is a unique strategy to rapidly develop novel and contemporary hypotheses. Most of the novel miRNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms associated with atherosclerosis and lipoprotein metabolism to date have first been determined by miRNA profiling, followed by functional testing (50,61). It should be noted, however, that simple steady-state expression profiles of miRNAs and mRNAs harbor several limitations; including the inability to observe active Ago-complexed miRNAs or repressed mRNAs. A seminal study by Chi et al., used high throughput sequencing to identify active miRNAs cross-linked to mRNA targets through Ago pull down enrichments (72). Sequenced mRNA footprints were mapped back to genomic sequence, along with identified (sequenced) miRNAs, to create ternary maps (72). This is a particularly insightful strategy, as global gene expression profiling alone often overestimates mRNA potential by scoring translationally-repressed mRNAs. This technique elucidates the in vivo diversity and specificity of miRNA and their targets, and will likely become a fundamental strategy in future profiling studies.

The use of miRNAs or inhibitors as therapeutic agents is showing great promise. miRNA mimetics and inhibitors are relatively stable in plasma and can simply be injected intravenously to reach their cellular gene targets, particularly in the liver, without apparent toxicity (71). Altering intracellular levels of hepatic miRNAs directly through such mimetics or inhibitors, or indirectly through small molecules that control miRNA expression at the transcriptional levels have an enormous therapeutic potential. Currently, there are multiple strategies to inhibit endogenous miRNA expression, including antagomirs (73), 2′-O-methyl modified antisense oligos (74), hairpin-inhibitors (75), and protein-nucleic acid inhibitors (PNA) (76). In addition, new modifications and delivery vehicles for enhanced cellular uptake of mimetics or inhibitors have been described (77,78). Directly conjugating cholesterol to miRNA mimetics has been shown to potentiate cellular uptake (71); however, some gene expression changes may be attributed to cholesterol itself. In summary, miRNA profiling and functional testing will certainly play a significant role in future cardiovascular science discovery expedited by the rapid development of novel strategies and tools for working with miRNAs. The extensive impact of miRNA-mediated gene regulation and the relative ease of in vivo applicable modifications highlight the enormous potential of miRNA-based therapeutics in cardiovascular diseases.

Conclusions

Results from recent studies demonstrated a role for miRNAs in endothelial integrity, macrophage inflammatory response to oxLDL, VSMC proliferation, and cholesterol synthesis. These mechanisms are all vital to the initiation and proliferation of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. The importance of miRNAs has recently been recognized in cardiovascular sciences and miRNAs will likely become an integral part of our fundamental comprehension of atherosclerosis and lipoprotein metabolism.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Anne M. Deschamps for composing Figure 1. KCV and ATR are supported by N.I.H. / N.H.L.B.I. Intramural Funds.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du T, Zamore PD. Beginning to understand microRNA function. Cell Res. 2007;17:661–663. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez A, Griffiths-Jones S, Ashurst JL, Bradley A. Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res. 2004;14:1902–1910. doi: 10.1101/gr.2722704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mourelatos Z. Small RNAs: The seeds of silence. Nature. 2008;455:44–45. doi: 10.1038/455044a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saini HK, Griffiths-Jones S, Enright AJ. Genomic analysis of human microRNA transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17719–17724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703890104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozsolak F, Poling LL, Wang Z, et al. Chromatin structure analyses identify miRNA promoters. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3172–3183. doi: 10.1101/gad.1706508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanzer A, Stadler PF. Molecular evolution of a microRNA cluster. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, et al. Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Cell. 2006;125:887–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3011–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutvágner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, et al. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim VN. MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:6156–6162. doi: 10.1038/nrm1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suárez Y, Fernández-Hernando C, Pober JS, Sessa WC. Dicer dependent microRNAs regulate gene expression and functions in human endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2007;100:1164–1173. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265065.26744.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suárez Y, Fernández-Hernando C, Yu J, et al. Dicer-dependent endothelial microRNAs are necessary for postnatal angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14082–14087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804597105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregory RI, Chendrimada TP, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2005;123:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond SM, Boettcher S, Caudy AA, et al. Argonaute2, a link between genetic and biochemical analyses of RNAi. Science. 2001;293:1146–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1064023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preall JB, Sontheimer EJ. RNAi: RISC gets loaded. Cell. 2005;123:543–545. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwarz DS, Hutvágner G, Du T, et al. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell. 2003;115:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lingel A, Simon B, Izaurralde E, Sattler M. Structure and nucleic-acid binding of the Drosophila Argonaute 2 PAZ domain. Nature. 2003;426:465–469. doi: 10.1038/nature02123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forman JJ, Legesse-Miller A, Coller HA. A search for conserved sequences in coding regions reveals that the let-7 microRNA targets Dicer within its coding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14879–14884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803230105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. • Solid review of the current state of miRNA biology.

- 22.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, et al. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du T, Zamore PD. microPrimer: the biogenesis and function of microRNA. Development. 2005;132:4645–4652. doi: 10.1242/dev.02070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most Mammalian mRNAs Are Conserved Targets of MicroRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. ** Improved background model now identifies offset 6mer target sites.

- 25.Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Parker R. Control of translation and mRNA degradation by miRNAs and siRNAs. Genes Dev. 2006;20:515–524. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, et al. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimson A, Farh KKH, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, et al. MicroRNA Targeting Specificity in Mammals: Determinants beyond Seed Pairing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved Seed Pairing, Often Flanked by Adenosines, Indicates that Thousands of Human Genes are MicroRNA Targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, et al. miRanda algorithm: Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammell M, Long D, Zhang L, et al. mirWIP: microRNA target prediction based on microRNA-containing ribonucleoprotein-enriched transcripts. Nat Methods. 2008;5:813–819. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krek A, Grün D, Poy MN, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendes ND, Freitas AT, Sagot MF. Current tools for the identification of miRNA genes and their targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2419–2433. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp145. **This review outlines current methods for computational miRNA gene finding and miRNA target prediction.

- 33.Ambros V, Bartel B, Bartel DP, et al. A uniform system for microRNA annotation. RNA. 2003;9:277–279. doi: 10.1261/rna.2183803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross R. Atherosclerosis: an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Widlansky ME, Gokce N, Keaney JF, Jr, Vita JA. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1149–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Endemann DH, Schiffrin EL. Endothelial dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1983–1992. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000132474.50966.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Role of Dicer and Drosha for endothelial microRNA expression and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101:59–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poliseno L, Tuccoli A, Mariani L, et al. MicroRNAs modulate the angiogenic properties of HUVECs. Blood. 2006;108:3068–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-012369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonauer A, Carmona G, Iwasaki M, et al. MicroRNA-92a controls angiogenesis and functional recovery of ischemic tissues in mice. Science. 2009;324:1710–1713. doi: 10.1126/science.1174381. **Major observation of the potential therapeutic impact with miRNAs (miR-92a) in ischemia.

- 40.Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, et al. The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008;15:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holm PW, Slart RH, Zeebregts CJ, et al. Atherosclerotic plaque development and instability: a dual role for VEGF. Ann Med. 2009;41:257–64. doi: 10.1080/07853890802516507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urbich C, Kuehbacher A, Dimmeler S. Role of microRNAs in vascular diseases, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:581–588. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zampetaki A, Kirton JP, Xu Q. Vascular repair by endothelial progenitor cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:413–421. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minami Y, Satoh M, Maesawa C, et al. Effect of atorvastatin on microRNA 221 / 222 expression in endothelial progenitor cells obtained from patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02110.x. ** Significant finding that miRNAs likely mediate the beneficial pleiotropic effects of statins.

- 46.Dimmeler S, Aicher A, Vasa M, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) increase endothelial progenitor cells via the PI 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:391–397. doi: 10.1172/JCI13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Adler K, et al. Increase in circulating endothelial progenitor cells by statin therapy in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;103:2885–2890. doi: 10.1161/hc2401.092816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rivard A, Andrés V. Vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Histol Histopathol. 2000;15:557–571. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muto A, Fitzgerald TN, Pimiento JM, et al. Smooth muscle cell signal transduction: implications of vascular biology for vascular surgeons. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:A15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji R, Cheng Y, Yue J, et al. MicroRNA expression signature and antisense-mediated depletion reveal an essential role of microRNA in vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ Res. 2007;100:1579–1588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.141986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, et al. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460:705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. ** Major finding that miRNAs control smooth muscle cell fate and phenotypic plasticity.

- 52.Lin Y, Liu X, Cheng Y, et al. Involvement of MicroRNAs in hydrogen peroxide-mediated gene regulation and cellular injury response in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7903–7913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806920200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang C. MicroRNA-145 in vascular smooth muscle cell biology: a new therapeutic target for vascular disease. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3469–3473. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng Y, Liu X, Yang J, et al. MicroRNA-145, a novel smooth muscle cell phenotypic marker and modulator, controls vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ Res. 2009;105:158–166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197517. *Important observation that miR-145 controls neointimal lesion formation.

- 55.Liu X, Cheng Y, Zhang S, et al. A necessary role of miR-221 and miR-222 in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal hyperplasia. Circ Res. 2009;104:476–487. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.185363. *Significant observation that two miRNAs (miR-221/222), previously shown to regulate endothelial function, also control vascular smooth muscle proliferation.

- 56.Zhang C. MicroRNA and vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype: new therapy for atherosclerosis? Genome Med. 2009;1:85. doi: 10.1186/gm85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boettger T, Beetz N, Kostin S, et al. Acquisition of the contractile phenotype by murine arterial smooth muscle cells depends on the Mir143/145 gene cluster. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2634–2647. doi: 10.1172/JCI38864. ** Major observation that miR-143/miR-145 cluster regulates vascular smooth muscle contractile (differentiated) phenotype.

- 58.Xin M, Small EM, Sutherland LB, et al. MicroRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and responsiveness of smooth muscle cells to injury. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2166–2178. doi: 10.1101/gad.1842409. *Interesting finding that miR-143/miR-145 regulate smooth muscle cell response to injury through cytoskeleton dynamics.

- 59.Elia L, Quintavalle M, Zhang J, et al. The knockout of miR-143 and -145 alters smooth muscle cell maintenance and vascular homeostasis in mice: correlates with human disease. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1590–1598. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rader DJ, Puré E. Lipoproteins, macrophage function, and atherosclerosis: beyond the foam cell? Cell Metab. 2005;1:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen T, Huang Z, Wang L, et al. MicroRNA-125a-5p partly regulates the inflammatory response, lipid uptake, and ORP9 expression in oxLDL-stimulated monocyte/macrophages. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:131–139. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp121. **Major observation that miR-125a-5p regulates lipid uptake and cytokine production in monocyte/macrophages.

- 62.Dietschy JM, Turley SD. Control of cholesterol turnover in the mouse. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3801–3804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100057200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Girard M, Jacquemin E, Munnich A, et al. miR-122, a paradigm for the role of microRNAs in the liver. J Hepatol. 2008;48:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lynn FC. Meta-regulation: microRNA regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen XM. MicroRNA signatures in liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1665–1672. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, et al. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002;12:735–739. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liscum L, Munn NJ. Intracellular cholesterol transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1438:19–37. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Esau C, Davis S, Murray SF, et al. miR-122 regulation of lipid metabolism revealed by in vivo antisense targeting. Cell Metab. 2006;3:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elmén J, Lindow M, Schütz S, et al. LNA-mediated microRNA silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2008;452:896–899. doi: 10.1038/nature06783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krützfeldt J, Rajewsky N, Braich R, et al. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature. 2005;438:685–689. doi: 10.1038/nature04303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. **High impact study demonstrating HITS-CLIP method.

- 73.van Solingen C, Seghers L, Bijkerk R, et al. Antagomir-mediated silencing of endothelial cell specific microRNA-126 impairs ischemia-induced angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1577–1585. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fabani MM, Gait MJ. miR-122 targeting with LNA/2′-O-methyl oligonucleotide mixmers, peptide nucleic acids (PNA), and PNA-peptide conjugates. RNA. 2008;14:336–346. doi: 10.1261/rna.844108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vermeulen A, Robertson B, Dalby AB, et al. Double-stranded regions are essential design components of potent inhibitors of RISC function. RNA. 2007;13:723–730. doi: 10.1261/rna.448107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shakeel S, Karim S, Ali A. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA)- a review. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2006;81:892–899. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Horwich MD, Zamore PD. Design and delivery of antisense oligonucleotides to block microRNA function in cultured Drosophila and human cells. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1537–1549. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mäe M, Andaloussi SE, Lehto T, Langel U. Chemically modified cell-penetrating peptides for the delivery of nucleic acids. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:1195–1205. doi: 10.1517/17425240903213688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]