Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) entry is mediated by the interaction between a variably glycosylated envelope glycoprotein (gp120) and host-cell receptors. Approximately half of the molecular mass of gp120 is contributed by N-glycans, which serve as potential epitopes and may shield gp120 from immune recognition. The role of gp120 glycans in the host immune response to HIV-1 has not been comprehensively studied at the molecular level. We developed a new approach to characterize cell-specific gp120 glycosylation, the regulation of glycosylation, and the effect of variable glycosylation on antibody reactivity. A model oligomeric gp120 was expressed in different cell types, including cell lines that represent host-infected cells or cells used to produce gp120 for vaccination purposes. N-Glycosylation of gp120 varied, depending on the cell type used for its expression and the metabolic manipulation during expression. The resultant glycosylation included changes in the ratio of high-mannose to complex N-glycans, terminal decoration, and branching. Differential glycosylation of gp120 affected envelope recognition by polyclonal antibodies from the sera of HIV-1-infected subjects. These results indicate that gp120 glycans contribute to antibody reactivity and should be considered in HIV-1 vaccine design.

Keywords: Glycosylation, HIV, Immunology, Post-translational Modification, Viral Immunology, Antibody Binding, HIV-1 Glycoprotein gp120

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)4 entry is dependent on envelope glycoprotein (Env), which consists of two noncovalently bound subunits, the external gp120 and the transmembrane gp41. Present on virion surfaces as trimers of gp120-gp41 complexes, Env is involved in the binding of virus to the host receptor and co-receptor(s), the initial step in cell entry. Env is also the target for the binding of neutralizing antibodies (1–4).

Considerable effort has been devoted to generating an Env-based vaccine, but with limited success (5–8). The main obstacles in such efforts include poor immunogenicity of vaccine constructs and enormous variability and genetic plasticity of the env gene of various HIV-1 strains. Approximately half the total molecular mass of gp120 is contributed by N-linked glycans with a small and variable contribution of O-linked glycans (9–11). N-Linked glycans can be attached to the protein backbone at positions predetermined by short amino acid motifs (N-X-S/T) designated as potential N-glycosylation sites. Thus, the viral genome encoding these motifs ultimately determines the sites of glycosylation. However, the biosynthetic machinery of host cells profoundly affects composition of the attached glycans. Recently, some of the sites with the N-glycan-determining sequence motif were shown to be unoccupied (10), suggesting that glycosylation of Env, including gp120, is co-determined by the viral genome and the host cells in which the virus is produced (9, 12–17).

Oligosaccharide constituents of gp120 were described soon after the discovery of HIV-1, but their contribution to the virus life cycle, immune evasion, and recognition were not fully recognized until later (18). Host cell attachment and HIV-1 entry involves interactions between gp120 and two major cell-surface molecules: CD4 receptor and the chemokine co-receptor CCR5 or CXCR4. The differential usage of co-receptors distinguishes HIV-1 phenotypes; CCR5-tropic viruses constitute the vast majority of initially transmitted strains and predominate during primary infection, particularly in gut mucosa (19–24). Analyses of HIV-1 DNA sequences have suggested a close association between the potential N-glycosylation sites of V1/V2, V3, and V4 loops and CCR5 or CXCR4 usage (25–30). These studies characterized env DNA sequences but did not assess whether the potential N-glycosylation sites were occupied or whether a specific glycan composition can affect the gp120-coreceptor interactions. Attachment of glycans not only modifies the Env surface but also contributes to correct folding and charge distribution on Env, all of which may be influenced by the cell type in which the virus is propagated. Furthermore, gp120 glycans serve as a shield against neutralizing antibodies (31) with HIV-1 escape variants characterized by diverse env sequences present in the chronic stages of infection (4, 23, 25–26, 32–39). These escape variants emerge as a consequence of the pressure created by the humoral immune responses and, thus, are resistant to neutralizing antibodies. However, several monoclonal antibodies specific for N- or O-glycans, or peptide epitopes whose conformation are substantially affected by surrounding glycans, block viral infection and/or syncytium formation (40–49), and may display broadly neutralizing activities, i.e. neutralize many different strains of HIV-1. One of the best described antibodies, 2G12, recognizes terminal α1,2-linked mannose on high-mannose N-linked glycan residues attached to gp120 backbone at positions 332, 392, and to a lesser degree, 339 (47, 50–52). Unfortunately, such antibodies are difficult to generate by immunization. In contrast, incorporating extra potential N-glycosylation sites in the experimental gp120 vaccines has been used as a strategy to prevent induction of antibody response against gp120 regions with low neutralization capacity and redirect it to regions recognized by highly neutralizing antibodies, such as b12 (3).

For all glycoproteins, including Env, the structure, composition, and heterogeneity of attached glycans depend on the cellular system used for their expression (12). This fact is not always reflected in the production of recombinant HIV-1 gp120 antigens for immunization and/or antibody detection; cell lines with high protein synthetic rate, including Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO), human embryonic kidney cells (293T), and insect cells (Sf9), are commonly used rather than T cells and monocytes, the natural host cells for HIV-1 (35, 53–57). Similarly, DNA vaccination into the muscle, skin, or mucosal tissue is used according to the desired type of elicited immune response, without considering that the site of antigen expression may impact the generation of relevant vaccine-induced epitopes (58, 59). Consequently, differences in the glycan composition of Env produced by the DNA-vaccinated animals compared with human volunteers may contribute to the failure of certain vaccine candidates (8, 60, 61).

Here we show that gp120 glycosylation is profoundly influenced by the tissue origin and metabolic activity of the producing cells, resulting in distinct gp120 N-glycan content and heterogeneity. Using high-resolution mass spectrometry, we have unambiguously identified the glycan composition of N-glycans on the recombinant gp120 produced in different cell types. Furthermore, we show that differential glycosylation of the same amino acid backbone significantly affects Env binding by polyclonal antibodies from sera of HIV-1-infected subjects.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma and tissue culture media and reagents from Invitrogen.

Human Sera

Sera from HIV-1-positive patients and seronegative healthy controls were obtained from volunteers recruited through the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) AIDS 1917 Clinic. The samples were obtained according to an IRB-approved protocol after written informed consent.

Plasmid Construction

Plasmid encoding codon-optimized consensus B gp120 DNA (GenBankTM DQ667594 fragment 88–1485) fused at the 5′ end with cDNA coding for the first 62 amino acids of human mannan-binding lectin (GenBank EU596574 fragment 66–252) was prepared by cloning the construct into pcNDA3.1D/V5-HIS (Invitrogen) (62). The gp120 DNA was a generous gift from Dr. Beatrice Hahn, UAB, and the mannan-binding lectin cDNA fragment was isolated from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by reverse transcription-PCR. Recombinant gp120 was expressed in the N-terminal fusion with a 62-amino acid non-glycosylated fragment of mannan-binding lectin to drive gp120 oligomerization and secretion of the fusion protein; two more tags, C-terminal located His tag and V5 tag, were added for purification and detection purposes, respectively (62).

Generation of Stable Cell Lines Expressing gp120

The following cell lines were obtained from ATCC: human embryonic kidney cell line (293T), CHO cells, human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2), human T cell leukemia cells (Jurkat), human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (Molt4), human EBV-immortalized B-cell line (Dakiki), human rhabdomyosarcoma cells (RD), and human fibrosarcoma cells (HT1080). Cells were cultured before transfection in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mm l-glutamine and antibiotics. Transfection of adherent cell lines was performed with FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Suspension cell lines were transfected using nucleofector (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's manual. Cells were cultured for 24 h, followed by selection of the transfected cells with G418 (Invitrogen) for 21 days, and then subcloned and tested for secretion of recombinant gp120 protein by dot blot and Western blot with anti-V5-tag antibody (Invitrogen). Selected clones from each cell line were used for large scale expression of gp120.

Antigen Expression and Purification

Each cell clone was used to isolate at least 100 μg of the glycoprotein. Before harvesting, the culture was transferred into serum-free medium without G418 for 48 h. gp120 was purified by affinity nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA)-agarose under native conditions, according to the manufacturer's suggestions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The elution buffer was exchanged for phosphate-buffered saline using Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter Unite (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Concentration of recombinant glycoproteins was determined by a BCA protein assay (Pierce) and verified by quantitative SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad) with densitometric analysis of Coomassie Blue-stained protein bands. Proteins were stored at −80 °C before use.

Treatment of gp120 with Glycosidases

Three different glycosidases (Prozyme, St. Louis, MO) were used for digestion: recombinant peptide N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) (removes all N-glycans from gp120) from Flavobacterium meningosepticum, endo N-glycosidase H (Endo H) (removes high-mannose glycans) from Streptomyces plicatus, and neuraminidase (removes sialic acid) from Arthrobacter ureafaciens were used in separate reactions. PNGase F from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA) was used in some experiments, as specifically mentioned; this preparation was isolated from F. meningosepticum and contained trace amounts of several other endo- and exoglycosidases that remove reducing N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues from high-mannose glycans. gp120 protein (1 μg) was denatured prior the enzymatic reaction (5 min boiling in 25 μl of 1× denaturing buffer provided for PNGase F and Endo H or in 2% SDS plus 1% 2-mercaptoethanol for neuraminidase treatment). After denaturation, samples were chilled on ice for 5 min, and 5 μl of 10× incubation buffer (supplied for each enzyme) was added (for PNGase F-treated samples, additional 5 μl of 10% Nonidet P-40 was added). Each reaction volume was adjusted to 46 μl and finally the diluted enzyme (4 μl) was added and content of each tube was gently but thoroughly mixed, incubated at 37 °C for 30 h, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE or mass spectrometry. Glycans for mass spectrometric analysis were purified by column chromatography (63).

SDS-PAGE/Western Blots

Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and blotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using Semi-Dry blotter (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked overnight using Super block (Pierce). Subsequently, the membranes were developed with the indicated lectins or antibodies: horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated PHA-L (Phaseolus vulgaris, EY Laboratories) diluted 1:500 in Superblock plus 0.05% Tween 20 (SB-T) and HRP-conjugated GNL (Galanthus nivalis; EY Laboratories) diluted 1:20,000 in SB-T were incubated overnight at 4 °C; biotinylated AAL (Aleuria aurantia; Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:10,000 in SB-T was incubated overnight at 4 °C, washed, and subsequently incubated with HRP-neutravidin for 1 h at room temperature; and the HRP-conjugated anti-V5-tag (Invitrogen) diluted 1:7,000 in SB-T was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Binding of antibodies or lectins was detected by the SuperSignal West Pico reagents (Pierce) and visualized by exposition on x-ray film (Kodak) or scanning of the membranes by a cooled CCD camera (Roche Applied Science). Specificity of the lectins is shown in Fig. 3.

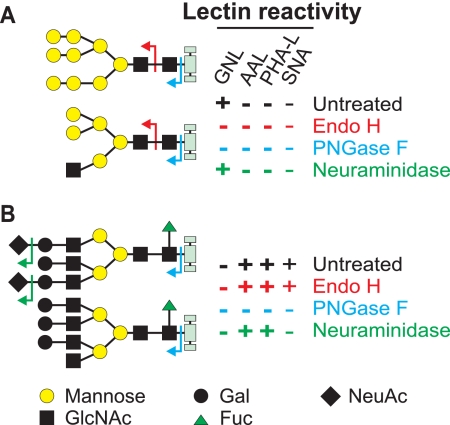

FIGURE 3.

Reactivity of selected lectins with N-linked oligosaccharides. Scheme of reactivity of gp120 after digestion with PNGase F (to remove all N-linked oligosaccharides), Endo H (to cleave only high-mannose and hybrid oligosaccharides), or neuraminidase (to remove sialic acid). Reactivities of lectins GNL, AAL, PHA-L, and Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) with high-mannose or hybrid (A) and complex (B) oligosaccharides are based on recognition of specific oligosaccharide structures remaining on gp120 after treatment with specified glycosidase. For simplicity, the reactivity is expressed as plus (+) or minus (−).

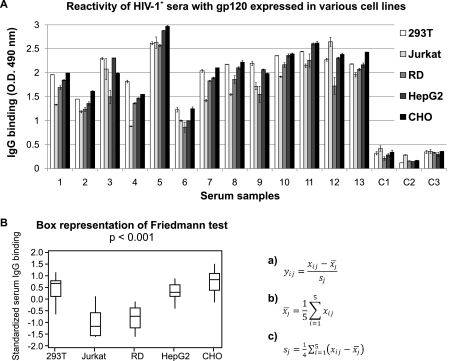

ELISA

To determine the reactivity of IgG from sera of patients infected with HIV-1 subtype B, ELISA plates were coated with the same amounts of gp120 preparations produced in different cells. gp120 concentrations were determined by the BCA method and 100-μl aliquots of gp120 proteins normalized to final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml were coated on ELISA Nunc-Immuno plates MaxiSorp (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark). All assays were performed in duplicates with sera diluted 1:10,000. IgG antibodies bound to gp120 preparations were detected with HRP-labeled goat antibody against human IgG (Sigma) and developed with o-phenylenediamine-H2O2 substrate. The reaction was stopped with 1 m sulfuric acid, and the absorbance measured at 490 nm. The mean standardized values were analyzed using the Friedmann non-parametric test and the Tukey method of multiple comparisons performed with SAS/STAT software.

Analysis of Monosaccharide Composition

The monosaccharides from purified gp120 were determined as trifluoroacetates of methylglycosides by gas-liquid chromatography. The analyses were performed with a gas chromatograph (model 5890, Hewlett-Packard, Sacramento, CA) equipped with a 25-m fused silica (0.22-mm inner diameter) OV-1701 WCOT column (Chrompack, Bridgewater, NJ) and electron capture detector. About 5 μg of each purified gp120 protein was used for analysis with sorbitol as the internal standard (64, 65). The results were expressed relative to the internal standard and specific sugar standard, using the area under the peak in chromatograms.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis of N-Glycan Profiles

PNGase F-removed glycans were analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometry using column-purified N-glycans (63, 66). The desalted samples of neutral oligosaccharides were analyzed in positive ion mode using 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid/5-methoxysalicylic matrix with 10 mmol/liter of sodium chloride as described (63). Oligosaccharide standards (Oxford GlycoSciences, Bedford, MA) were used for the external calibration for mass assignment of ions. In some experiments, the released glycans were treated with neuraminidase to allow examination of total glycan profiles in positive spectra.

High-resolution Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Purified Glycans

Analysis of purified glycans was performed with a monolithic silicon microchip-based electrospray source, the TriVersaTM Nanomate (Advion, Ithaca, NY) coupled to a hybrid linear quadrupole ion trap FT-ICR mass spectrometer (LTQ FT, ThermoFisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Fifty μg of purified glycans from each cell line were electrosprayed sequentially to obtain a series of FT-ICR mass spectrometry scans (500 < m/z < 2000), as previously described (67). Further characterization of individual N-glycan ion species was performed using collision-induced dissociation LTQ tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) as previously described (66, 67) or infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD) FT-ICR MS/MS. For IRMPD MS/MS analysis, the isolation width was m/z 7 with an automatic gain control target value of 5 × 104, maximum fill 250 ms. Following transfer to the ICR cell, precursor ion populations were photon-irradiated for 100 ms at 30% (6 W) laser power. Each IRMPD scan was acquired as an FT-ICR MS/MS spectrum (150 < m/z < 2000) at a mass resolving power of 100,000 at m/z 400. Each displayed spectrum represents the sum of 30 to 50 scans.

Metabolic Manipulations of Cell Cultures

Jurkat and HepG2 cell lines expressing gp120 were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum until a density of 5 × 105 (Jurkat) or 80% confluence (HepG2) in 50-ml or 25-ml culture flasks and the culture medium was replaced with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum, antibiotics, and G418 plus metabolites in the following final concentration: GlcNAc 80 mm, uridine 5 mm, GlcNAc 80 mm plus, uridine 5 mm, succinate 20 mm, pyruvate 4.5 mm, galactose (Gal) 50 mm, mannose (Man) 50 mm, deoxymannojirimycin (DMJM) 800 μm, and cultured for 10 h. Subsequently, media were replaced by fetal calf serum-depleted medium supplemented with the respective metabolites, and the cells were cultured for another 64 h. Supernatants were used for isolation of gp120 using Ni-NTA-agarose.

RESULTS

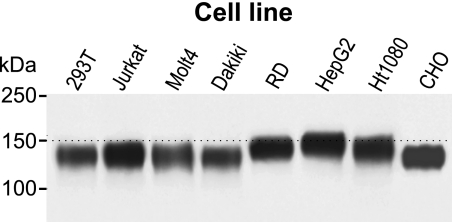

Molecular Mass of gp120 Produced in Different Cell Types Varies Due to Differential Glycosylation

To obtain glycoprotein in quantities sufficient for the analyses, recombinant gp120 was produced by the following cell lines: human embryonic kidney cells (293T), T cells (Jurkat and Molt 4), B cells (Dakiki), RD cells, hepatocytes (HepG2), fibrosarcoma cells (HT 1080), and CHO cells. These cell lines represent types of cells infected by HIV-1 (T cells), used for expression of recombinant gp120 vaccine antigen (293T, CHO), potentially targeted by DNA vaccine (RD, HepG2, HT1080), and control B cells (Dakiki). The gp120 produced by the cell lines was secreted as an oligomer (62) and then purified by affinity chromatography and the preparations were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Western blotting and detected with anti-V5-tag antibody. The apparent molecular masses of gp120 ranged from ∼125 (CHO and Dakiki cells) to ∼145 kDa (HepG2 cells) (Fig. 1). The difference in molecular mass was attributable to differential glycosylation of the common protein backbone (molecular mass 64.5 kDa). Software prediction analysis of N-glycosylation motifs by NetNGlyc 1.0 (Technical University of Denmark) revealed 25 potential glycosylation sites within the gp120 amino acid sequence (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). Analysis of O-glycosylation sites revealed only one potential glycosylation site with a high threshold value (supplemental Fig. S1C) (68). These results are in agreement with previous observations that gp120 is heavily glycosylated by predominantly N-linked oligosaccharides (11, 12).

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of the molecular mass of gp120 expressed in different cell types. gp120 was expressed in the indicated cell lines transfected with a DNA construct encoding the gp120 protein fused with mannan-binding lectin and His tag and V5 tag. The glycoproteins were purified using Ni-NTA-agarose, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, blotted, and detected with anti-V5-tag antibody. Positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left. Representative results from two experiments are shown.

Ratio of High-mannose to Complex N-Glycans on gp120 Is Dependent on the Cell Line Used for Expression

To assess the relative content of high-mannose glycans versus complex glycans, we analyzed gp120 expressed in different cell lines before and after treatment with PNGase F (removes all N-glycans) or Endo H (removes high-mannose and hybrid N-glycans but not complex N-glycans). To assess the extent of sialylation, we used neuraminidase treatment to remove sialic acid present in complex glycans. All preparations were analyzed by lectin and antibody Western blotting (Fig. 2). The expected reactivities of the glycan-specific lectins after differential glycosidase treatment are detailed in Fig. 3 and serve as the key for recognizing differences in gp120 glycosylation produced by the tested cell lines.

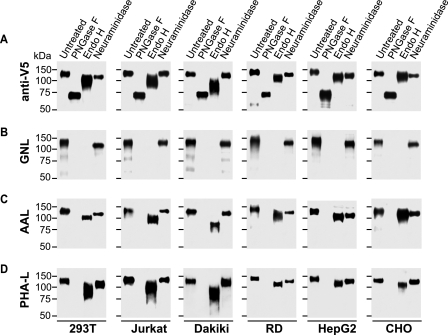

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of gp120 glycans by mobility shift after endoglycosidase treatment. gp120 expressed in 293T, Jurkat, Dakiki, RD, HepG2, and CHO cell lines were treated with PNGase F, Endo H, or neuraminidase or remained untreated after which the preparations were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, blotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and developed with anti-V5-tag antibody (A), lectins G. nivalis, GNL (high-mannose glycan-specific) (B), A. aurantia, AAL (fucose-specific) (C), or P. vulgaris, PHA-L (specific for complex glycans with ≥3 antennas) (D). Representative data from at least two different experiments are shown.

The gp120 produced by the indicated cell lines displayed marked differences in the content of high-mannose glycans relative to complex glycans as well as variable N-glycan heterogeneity. Lectin Western blotting confirmed the quantitative removal of high-mannose glycans by Endo H and all N-glycans by PNGase F treatment, respectively (Figs. 2 and 3). Consequently, SDS-PAGE migration of Endo H-treated gp120 compared with that of PNGase F-treated gp120 was proportional to the content of complex glycans. As shown in Fig. 2, gp120 produced by T cells contained most high-mannose glycans, whereas gp120 derived from HepG2 cells displayed a higher proportion of complex glycans. In addition, the relative broadness of the Endo H-treated gp120 band (Fig. 2, panel A) reflected the heterogeneity of complex glycans due to variable numbers of glycans or differences in glycan composition or both. gp120 produced by T cells (Jurkat), B cells, and 293T cells exhibited an extensive heterogeneity of complex glycans (Fig. 2, Endo H lanes) compared with gp120 produced by RD cells, hepatocytes, and CHO cells; the latter cell types produced gp120 with the lowest proportion of high-mannose glycans. Furthermore, treatment with neuraminidase revealed differential sialylation of the gp120 glycoproteins with gp120 from T cells exhibiting the smallest shift after enzyme treatment, consistent with a reduced sialic acid content (Fig. 2). These results indicate that different cell types differentially glycosylate the same gp120 protein backbone.

Differences in the Glycosylation of gp120 Are Cell Type- specific

Monosaccharide compositional analysis (Table 1) confirmed that the differences in gp120 glycosylation are cell type-dependent. Recombinant gp120 preparations with a high content of high-mannose glycans (e.g. gp120 produced by the Jurkat T-cell line) displayed less Gal and sialic acid compared with gp120 proteins from HepG2, which had less high-mannose glycans. The gp120 expressed by HepG2 cells contained more fucose compared with gp120 produced by other cell lines, suggesting unique complex glycans generated by HepG2.

TABLE 1.

Monosaccharide composition of gp120 produced by different cell lines determined by gas-liquid chromatography

Data are expressed as average from two experiments relative to standard sugars and normalized to internal standard, based on the area under the peak in the chromatograms.

| Sugar | 293T | Jurkat | RD | HT1080 | HepG2 | CHO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucose | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.17 |

| Mannose | 3.21 | 2.19 | 1.39 | 2.77 | 2.16 | 2.32 |

| Galactose | 0.78 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 1.09 | 1.02 | 0.63 |

| Glucose | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Internal standard | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| GlcNAc | 2.08 | 1.37 | 0.59 | 1.70 | 1.74 | 1.27 |

| GalNAc | 0.12 | NDa | ND | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Sialic acid | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.63 | 0.89 | 0.66 |

a ND, not detected.

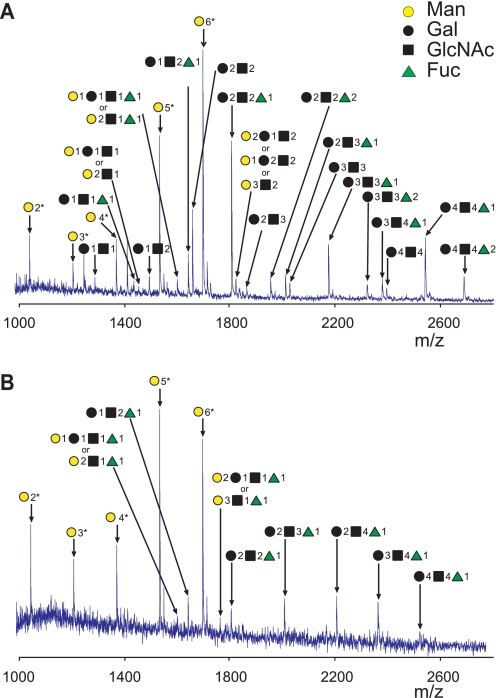

These findings prompted mass spectrometric analysis of N-glycans to define the population of glycan structures present on gp120 from a single cell-type source. For this analysis, we used MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and high-resolution FT-ICR mass spectrometry (11, 69, 70). Mass spectra of N-glycans isolated from the gp120 produced by hepatocytes (HepG2) and T cells (Jurkat) showed that high-mannose oligosaccharides ranging in size from (GlcNAc)2(Man)5 to (GlcNAc)2(Man)9 were the most abundant (Fig. 4, Table 2, supplemental Figs. S2 and S3, and supplemental Table S1). In total, 33 different complex and hybrid-type N-linked glycans were detected by mass spectrometry. Twenty-seven, 22, 17, 11, and 16 complex/hybrid N-glycans were identified in gp120 produced by 293T, HepG2, RD, Jurkat, and CHO cell lines, respectively (Table 2). Bifucosylated complex glycans were identified only in gp120 produced by HepG2 cells. All N-glycans identified by FT-ICR mass spectrometry were observed with mass accuracies ≤5 ppm (Table 2). Individual high-mannose and complex/hybrid N-glycans including bifucosylated glycans were confirmed by tandem mass spectrometry (Table 2 and supplemental Fig. S2, A-G). The findings by mass spectrometry (Table 2, Fig. 4, supplemental Fig. S3, and supplemental Table S1) were consistent with results of monosaccharide compositional analysis (Table 1) and lectin Western blotting (Fig. 2). Together, these detailed analyses delineated cell-dependent molecular differences in gp120 glycosylation, including variable content of high-mannose versus complex glycans, and complex glycan decoration.

FIGURE 4.

Examples of N-glycan profiles from MALDI-TOF mass spectra. N-Linked oligosaccharides were isolated after digestion of gp120 expressed by HepG2 (A) or Jurkat cell lines (B) with PNGase F. Symbols with numbers indicate the number of saccharides added to the common core (GlcNAc)2(Man)3. Samples were prepared with PNGase F enzyme isolated from Flavobacterium that contained trace amounts of endo- and exoglycosidases that resulted in removing the reducing-end GlcNAc from high-mannose glycans (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Identities of these glycans were confirmed by tandem mass spectrometry with LTQ mass spectrometry. *, denotes high-mannose glycans with (GlcNAc)1(Man)3 core. Representative results from two experiments are shown. Supplemental Fig. S3 shows MALDI-TOF mass spectra of glycans of the five gp120 preparations with molecular masses and compositions of detected glycans indicated.

TABLE 2.

Summary of MALDI-TOF and LTQ-FT ICR mass spectrometric analyses of N-glycans of gp120 expressed by different cell lines

| Number added to N-glycan corea | 293T |

Jurkat |

RD |

HepG2 |

CHO |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALDI | FT-ICR | MALDI | FT-ICR | MALDI | FT-ICR | MALDI | FT-ICR | MALDIb | FT-ICR | |||

| Hex | GlcNAc | Fuc | Errorc | Error | Error | Error | Error | Error | Error | Error | Error | Error |

| High-mannose glycans | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.675 | 0.004 | 0.498 | −0.007 | 0.582 | 0.008 | 0.690 | −0.002 | 0.089 | 0.002 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.750 | −0.005 | 0.540 | −0.006 | 0.660 | −0.003 | 0.773 | −0.001 | 0.109 | 0.000 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.634 | 0.000 | 0.569d | −0.003 | 0.628 | 0.003 | 0.761 | 0.001 | 0.121 | 0.003 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.787 | 0.004 | 0.601 | −0.004 | 0.685 | 0.003 | 0.817 | 0.000 | 0.128 | −0.001 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0.840d | 0.002 | 0.649 | −0.003 | 0.742 | −0.001 | 0.880 | 0.003 | 0.137d | 0.000 |

| Complex/hybrid glycans | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.958 | 0.000 | 0.101 | 0.001 | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.751 | 0.657 | 0.771 | 0.110 | 0.000 | |||||

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.752 | 0.657 | 1.043 | 0.106 | ||||||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.802 | 0.002 | 0.616 | 0.001 | 0.737 | 0.833 | ||||

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 0.798 | −0.002 | ||||||||

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.838 | −0.005 | 0.780 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.749 | 0.667 | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.727 | 0.674 | 0.818 | 0.107 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.807 | 0.001 | 0.687 | 0.698 | 0.000 | 0.844 | 0.005 | 0.126 | −0.002 | |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.821 | −0.001 | 0.703 | −0.002 | 0.839 | 0.003 | 0.124 | −0.002 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.876 | −0.005 | 0.694 | 0.001 | 0.739d | 0.003 | 0.895 | −0.004 | 0.138 | −0.002 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.930d | −0.003 | ||||||||

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 0.883 | −0.002 | 0.752 | 0.008 | 0.920 | 0.000 | 0.115 | |||

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.912 | 0.139 | −0.006 | |||||||

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 0.009 | |||||||||

| 0 | 3 | 1 | −0.001 | 0.093 | ||||||||

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.867d | −0.006 | 0.768 | 0.003 | −0.002 | 0.134 | ||||

| 2 | 3 | 0 | 0.870 | 0.735 | 0.005 | |||||||

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 0.919 | −0.001 | 0.716 | 0.768 | 0.009 | 0.948 | −0.004 | |||

| 2 | 3 | 2 | −0.001 | |||||||||

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.895 | −0.008 | 0.000 | 0.792 | 0.942 | −0.005 | 0.127 | −0.002 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 0.974 | −0.009 | −0.006 | 0.873 | 0.005 | 1.000d | −0.006 | 0.142 | −0.004 | |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 1.099 | −0.006 | ||||||||

| 0 | 4 | 1 | 0.861 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 0.954 | −0.009 | ||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 0.968 | −0.005 | 0.785 | −0.001 | 0.918 | −0.009 | 0.102 | |||

| 3 | 4 | 0 | 1.042 | |||||||||

| 3 | 4 | 1 | 1.011 | 0.775 | −0.001 | 1.093 | 0.001 | |||||

| 4 | 4 | 0 | 0.931 | −0.006 | 0.992 | 0.010 | ||||||

| 4 | 4 | 1 | 1.111 | 0.801 | −0.002 | 0.968 | 1.095 | −0.003 | 0.141 | |||

| 4 | 4 | 2 | 1.144 | |||||||||

| 3 | 5 | 1 | 1.112 | 0.268 | ||||||||

| 4 | 5 | 1 | 1.133 | |||||||||

a N-glycan core is (GlcNAc)2(Man)3.

b Analyzed by MALDI-TOF/TOF.

c For each glycan detected, error in daltons is shown. The empty lanes means that the glycan was not detected in the particular gp120 preparation.

d Denotes glycans with tandem mass spectra shown in supplemental Fig. S2. Glycans from each gp120 sample were analyzed twice. Relative abundance data from FT-ICR MS spectra are shown in supplemental Table S1.

gp120 Cell Type-specific Glycosylation Is Co-determined by Cellular Metabolic State

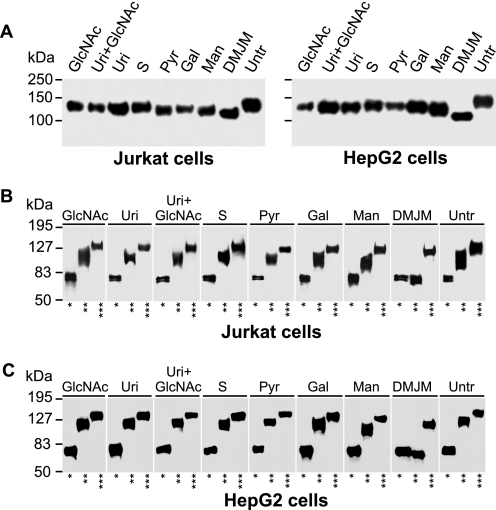

To test whether changes in host cell metabolic activity alters gp120 glycosylation, we cultured two cell lines (Jurkat and HepG2), which produce distinct gp120 glycosylations, in the presence of hexosamine pathway metabolites or glycosidase inhibitors. Jurkat cells produced gp120 with a large proportion of high-mannose oligosaccharides, whereas HepG2 cells produced gp120 with a high proportion of complex oligosaccharides. To assess the relative contribution of high-mannose glycans versus complex glycans to the detected changes in mobility of gp120 in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5A), we used untreated or endoglycosidase-treated samples and developed Western blots with anti-V5-tag antibody (Fig. 5). The mannosidase I inhibitor (DMJM) induced production of gp120 with only high-mannose N-glycans in both Jurkat and HepG2 cells, reflected in the same shifts in mobility after Endo H and PNGase F digests (Fig. 5, B and C). Moreover, the apparent molecular mass of gp120 produced by DMJM-treated cells was ∼20 kDa lower than that of gp120 produced by the untreated cells, indicating a lower contribution of high-mannose glycans to the apparent molecular mass of gp120 produced by HepG2 cells (Fig. 5A). Addition of mannose (50 mm) to the cell cultures increased the content of high-mannose glycans, especially in gp120 from HepG2 cells (Fig. 5, A and C). Conversely, the addition of hexosamine pathway metabolites to the cell cultures, particularly GlcNAc (80 mm) and Gal (50 mm), decreased the content of high-mannose glycans in favor of complex glycans (Fig. 5A). Finally, uridine-, pyruvate-, and succinate-treated Jurkat cells reduced the heterogeneity of complex glycans, as evidenced by a narrow band of gp120 after Endo H digestion (Fig. 5A). The effect of these three metabolites on glycosylation of HepG2-produced gp120 was less pronounced because HepG2 cells already produce less high-mannose glycans.

FIGURE 5.

gp120 glycosylation is influenced by metabolic manipulations. Jurkat and HepG2 cells stably transfected with gp120-encoding DNA plasmid were cultured in the presence of N-acetylglucosamine, 80 mm (GlcNAc); uridine, 5 mm (Uri); N-acetylglucosamine 80 mm plus uridine 5 mm (Uri+GlcNAc); succinate, 20 mm (S), pyruvate, 4.5 mm (Pyr); Gal, 50 mm; Man, 50 mm; DMJM, 800 μm; or mock-treated (Untr, negative control). gp120 was purified using Ni-NTA-agarose, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, blotted, and developed with anti-V5-tag antibody (A). Purified gp120 glycoproteins were treated with PNGase F (*), Endo H (**), or mock treated (***), and the resultant preparations were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-V5-tag antibody. gp120 was from Jurkat (B) and HepG2 cells (C). Representative results from two experiments are shown.

Cell-dependent gp120 Glycosylation Affects Binding of HIV-1-specific Antibodies from the Sera of HIV-1-infected Individuals

To determine whether antibodies in sera from HIV-1-infected persons can distinguish native gp120 produced in different cell types, we used ELISA to evaluate the reactivity of serum IgG from 13 HIV-1-positive patients (infected with subtype B) and three healthy-control subjects. Native gp120 preparations produced in 293T, HepG2, RD, CHO, and Jurkat cells served as antigens. The results revealed significant differences in the reactivities of antibodies in sera from different HIV-1-infected subjects (due to variable titers of HIV-1-specific antibodies). Furthermore, serum IgG antibodies from these subjects exhibited differential recognition of gp120 produced in different cell types (Fig. 6). When the reactivity of serum IgG from all HIV-1-positive patients for individual gp120 proteins was compared, statistically significant differences were confirmed for gp120 pairs (293T, Jurkat), (293T, RD), (CHO, Jurkat), (CHO, RD), (HepG2, RD), and (HepG2, Jurkat), as determined by the Tukey method of multiple comparisons (p < 0.05). Specifically, gp120 produced in RD and Jurkat cells exhibited less binding by the serum anti-gp120 antibodies compared with the other three preparations.

FIGURE 6.

Binding of IgG from HIV-1-positive patients (1–13) and HIV-1 negative control subjects (C1–C3) to purified native recombinant gp120 glycoproteins produced in 293T, HepG2, RD, CHO, and Jurkat cells was tested by ELISA. IgG in serum diluted 1:10,000 was allowed to bind to 96-well plates coated with an equal amount of our recombinant gp120 glycoproteins (0.5 μg/ml) and bound IgG antibodies were detected with anti-human IgG HRP-conjugated antibody. Mean values of absorbance and standard deviations are shown (A). Statistical analysis of differences in binding of serum IgG from HIV-1-positive subjects to individual gp120 preparations was performed by the Friedmann test, with results expressed as a box graph (p < 0.001). For this analysis, ELISA data (serum IgG binding intensity measured by OD) were standardized to eliminate inter-individual differences in absolute gp120-specific IgG concentration. Standardization was performed for values xij, i = 1, …,5, j = 1, …,16 according to the mathematical formula a, where x¯j (with macron) represents mean value for each serum reactivity (with individual gp120 preparations b), and sj is a sample standard deviation of all values measured for each serum c (B).

Based on these results, we further interrogated high resolution mass spectra of these gp120 preparations for relative quantitative differences. High-mannose glycan ions dominated the spectra for all five preparations. gp120 forms produced in 293T, HepG2, and CHO cells contained at least one form of complex glycan ions that was within 1 order of magnitude of the abundance of the high-mannose glycans. In contrast, gp120 produced in Jurkat and RD cells contained complex glycan ions that were all 2 orders of magnitude less than the high-mannose ions. Thus, the least antibody-reactive gp120 preparation from Jurkat and RD cells contain fewer total complex glycans and more high-mannose glycans compared with the high-reactive gp120 preparations. The high-resolution mass spectrometry data were corroborated by quantitative monosaccharide compositional analysis (Table 1 and supplemental Table S1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified differences in the N-linked oligosaccharide composition of recombinant gp120 expressed in different types of cells represented by eight mammalian cell lines. Differences in glycosylation were identified by changes in mobility on SDS-PAGE and confirmed by lectin Western blotting of the recombinant gp120 before and after digestion with PNGase F or Endo H. Human T cells produced gp120 with a large proportion of high-mannose glycans, in contrast to human hepatocytes (HepG2 cells) and human fibrosarcoma (HT1080) cell lines that secreted gp120 with a high content of complex glycans. The complex glycans were fucosylated and contained multiple antennas, as demonstrated by reactivities with AAL and PHA-L lectins, respectively. Furthermore, the complex glycans contained a variable amount of sialic acid, as evidenced by the mobility shifts in SDS-PAGE/Western blotting after neuraminidase treatment. The observed differences were confirmed and extended by monosaccharide compositional and mass spectrometric analysis. Importantly, the findings by mass spectrometry were consistent with results of monosaccharide compositional analysis and lectin Western blotting.

Comparisons of lectin Western blotting profiles, monosaccharide compositional analysis, and mass spectrometry data provided new insight into cell-specific differential glycosylation of gp120. All cell lines produced gp120 with high-mannose oligosaccharides that ranged in size from (GlcNAc)2(Man)5 to (GlcNAc)2(Man)9 and dominated the oligosaccharide spectra in relative abundance. gp120 from RD, Jurkat, and CHO cells contained less complex/hybrid glycans compared with high-mannose glycans. Although independent analysis of equimolar concentrations of high-mannose and complex/hybrid N-glycan standards indicated that high-mannose glycans have a higher ionization efficiency than complex/hybrid glycans, the results of mass spectrometric analyses were consistent with the lectin Western blotting data and monosaccharide composition (Fig. 2, A, lanes Endo H, and D, and Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). The observed differences in the abundance of high-mannose glycans may be related to differences in the expression of host-cell enzymes involved in the intracellular processing of high-mannose glycans and the first steps of synthesis of hybrid and complex glycans. For gp120 produced by 293T and HepG2 cells, complex glycans (Gal)2(GlcNAc)2(Fuc)1, (Gal)2(GlcNAc)2, (Gal)4(GlcNAc)4(Fuc)1, and high-mannose glycans with 6 and 5 Man residues were the most abundant modifications on the core glycan (GlcNAc)2(Man)3. Moreover, gp120 produced by 293T and HepG2 cells tended to have N-glycans with more antennas than gp120 produced by other cell lines. The greatest variability in glycosylation of gp120 by different cell lines was the number and content of complex and hybrid-type N-glycans.

The differences in N-glycan composition between T cell lines and 293T cells described here indicate a limitation in the commonly used 293T expression system for the production of gp120 antigen for vaccine purposes and crystallographic analyses of gp120 structures especially when N-glycan contribution to gp120 folding will be taken in account (2, 23, 35, 55, 57, 71–73). However, the similarity in gp120 expressed by RD cells, used for intramuscular DNA vaccine studies, and T cells, the in vivo target of HIV-1, supports the suitability of RD cells for the production of antigen to induce a humoral immune response (8, 54, 58, 74).

We also tested whether the N-glycan composition of gp120 is affected by modulating metabolic pathways, including the hexosamine pathway, which are crucial for generating complex N-glycans from high-mannose precursors (76). Our results showed that cells, such as HepG2, preferentially producing complex N-linked oligosaccharides on gp120 could modify their typical N-glycan profile to high-mannose glycans. This approach may be useful to establish appropriate conditions for the production of recombinant gp120 antigen in cell lines that do not produce the N-glycans present on gp120 produced by natural HIV-1 host cells, including T cells and monocytes (75, 77). Nevertheless, as was demonstrated for HepG2 cells (Fig. 5), the effect of a particular metabolite is still limited by the cell type producing the antigen or virus.

Most importantly, our studies confirmed that gp120-associated glycans also play a crucial role in the recognition of gp120 by polyclonal antibodies from sera of HIV-1-infected patients. Specifically, ELISA revealed that gp120 produced by RD and Jurkat cells bound less IgG antibodies that gp120 produced by 293T, HepG2, and CHO cells (p < 0.05). The observed differences in IgG binding were caused exclusively by the differential glycosylation of gp120, as all gp120 preparations had the same amino acid sequence. Specifically, gp120 produced in RD and Jurkat cells, i.e. glycoproteins that contained elevated amounts of high-mannose glycans and less complex glycans, exhibited less binding by the serum anti-gp120 antibodies compared with the other gp120 preparations. Future studies will be needed to determine whether the differential glycosylation of gp120 affects the efficacy of neutralizing antibodies and/or whether differently glycosylated gp120 could induce neutralizing antibodies of different specificities.

Using high-resolution mass spectrometry allowed unambiguous identification of the glycan composition of N-glycans on the recombinant gp120 produced in different cell types. Qualitatively, gp120 produced by Jurkat cells had fewer total identified complex/hybrid glycans. That the total amount of complex glycans on this gp120 preparation was 2 orders of magnitude less than that for the high-mannose glycans could also reflect a detection limit issue. Thus, the differences that we observed are likely the results of quantitative differences in the total amount of complex/hybrid versus high-mannose glycans (Table 1). Although it is not clear whether any site-specific differences play a role and whether epitope formation or epitope blocking or both are involved, the differences in glycosylation patterns of gp120 produced in various cell lines must be considered in the design of vaccines that stimulate protective humoral immune responses.

In summary, our results demonstrate that gp120 is differentially glycosylated, depending on the type of producer cell and its metabolic activity. Importantly, the differences in glycosylation patterns of gp120 produced by different cell types can affect recognition of Env by antibodies from HIV-1-infected patients. These results suggest that functions of HIV-1 glycans, which can act as an epitope(s) and a shield that blocks antibody recognition of polypeptide backbone, are co-determined by cell-specific glycosylation of gp120. Thus, glycan content and heterogeneity are important considerations in the design of gp120-based HIV-1 vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Beatrice Hahn for providing HIV-1 consensus B gp120 DNA and Dr. James A. Mobley and the University of Alabama Bioanalytical and Mass Spectrometry Shared Facility for access to the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK047322, AI028147, AI083027, RR-20136, T35 HL007473, AI078477, DK054495, AI067854, and AI071739, the Research Services of the Veterans Administration, Grants KONTAKT ME875, MSM 6198959223, and MSM 0021620812 from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport, Czech Republic, and a Pilot Project University of Alabama Mucosal HIV and Immunobiology Center Grant DK064400.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S3.

- HIV-1

- human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- Env

- envelope

- AAL

- Aleuria aurantia lectin

- DMJM

- deoxymannojirimycin

- Endo H

- endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H

- FT-ICR

- Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance

- GlcNAc

- N-acetylglucosamine

- GNL

- Galanthus nivalis lectin

- IRMPD

- infra-red multiphoton dissociation

- LTQ

- linear quadrupole ion trap

- MS/MS

- tandem mass spectrometry

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- PHA-L

- phytohemagglutinin L from Phaseolus vulgaris

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- PNGase F

- peptide N-glycosidase F

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- RD

- rhabdomyosarcoma.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kwong P. D., Wyatt R., Robinson J., Sweet R. W., Sodroski J., Hendrickson W. A. (1998) Nature 393, 648–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt R., Kwong P. D., Desjardins E., Sweet R. W., Robinson J., Hendrickson W. A., Sodroski J. G. (1998) Nature 393, 705–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pantophlet R., Burton D. R. (2006) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24, 739–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei X., Decker J. M., Wang S., Hui H., Kappes J. C., Wu X., Salazar-Gonzalez J. F., Salazar M. G., Kilby J. M., Saag M. S., Komarova N. L., Nowak M. A., Hahn B. H., Kwong P. D., Shaw G. M. (2003) Nature 422, 307–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauci A. S. (2008) Nature 453, 289–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balzarini J. (2005) Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 726–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Letvin N. L., Rao S. S., Dang V., Buzby A. P., Korioth-Schmitz B., Dombagoda D., Parvani J. G., Clarke R. H., Bar L., Carlson K. R., Kozlowski P. A., Hirsch V. M., Mascola J. R., Nabel G. J. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 12368–12374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson H. L. (2007) Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 82, 686–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu X., Borchers C., Bienstock R. J., Tomer K. B. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 11194–11204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go E. P., Irungu J., Zhang Y., Dalpathado D. S., Liao H. X., Sutherland L. L., Alam S. M., Haynes B. F., Desaire H. (2008) J. Proteome Res. 7, 1660–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irungu J., Go E. P., Zhang Y., Dalpathado D. S., Liao H. X., Haynes B. F., Desaire H. (2008) J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 19, 1209–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuochi T., Matthews T. J., Kato M., Hamako J., Titani K., Solomon J., Feizi T. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 8519–8524 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuochi T., Spellman M. W., Larkin M., Solomon J., Basa L. J., Feizi T. (1988) Biomed. Chromatogr. 2, 260–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuochi T., Spellman M. W., Larkin M., Solomon J., Basa L. J., Feizi T. (1988) Biochem. J. 254, 599–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reitter J. N., Means R. E., Desrosiers R. C. (1998) Nat. Med. 4, 679–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reitter J. N., Desrosiers R. C. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 5399–5407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho Y. S., Abecasis A. B., Theys K., Deforche K., Dwyer D. E., Charleston M., Vandamme A. M., Saksena N. K. (2008) Virol. J. 5, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montefiori D. C., Robinson W. E., Jr., Mitchell W. M. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 9248–9252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polzer S., Dittmar M. T., Schmitz H., Schreiber M. (2002) Virology 304, 70–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng G., Wei X., Wu X., Sellers M. T., Decker J. M., Moldoveanu Z., Orenstein J. M., Graham M. F., Kappes J. C., Mestecky J., Shaw G. M., Smith P. D. (2002) Nat. Med. 8, 150–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith O. (1997) Nat. Med. 3, 372–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith P. D., Meng G., Salazar-Gonzalez J. F., Shaw G. M. (2003) J. Leukocyte Biol. 74, 642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keele B. F., Giorgi E. E., Salazar-Gonzalez J. F., Decker J. M., Pham K. T., Salazar M. G., Sun C., Grayson T., Wang S., Li H., Wei X., Jiang C., Kirchherr J. L., Gao F., Anderson J. A., Ping L. H., Swanstrom R., Tomaras G. D., Blattner W. A., Goepfert P. A., Kilby J. M., Saag M. S., Delwart E. L., Busch M. P., Cohen M. S., Montefiori D. C., Haynes B. F., Gaschen B., Athreya G. S., Lee H. Y., Wood N., Seoighe C., Perelson A. S., Bhattacharya T., Korber B. T., Hahn B. H., Shaw G. M. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7552–7557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salazar-Gonzalez J. F., Salazar M. G., Keele B. F., Learn G. H., Giorgi E. E., Li H., Decker J. M., Wang S., Baalwa J., Kraus M. H., Parrish N. F., Shaw K. S., Guffey M. B., Bar K. J., Davis K. L., Ochsenbauer-Jambor C., Kappes J. C., Saag M. S., Cohen M. S., Mulenga J., Derdeyn C. A., Allen S., Hunter E., Markowitz M., Hraber P., Perelson A. S., Bhattacharya T., Haynes B. F., Korber B. T., Hahn B. H., Shaw G. M. (2009) J. Exp. Med. 206, 1273–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decker J. M., Bibollet-Ruche F., Wei X., Wang S., Levy D. N., Wang W., Delaporte E., Peeters M., Derdeyn C. A., Allen S., Hunter E., Saag M. S., Hoxie J. A., Hahn B. H., Kwong P. D., Robinson J. E., Shaw G. M. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201, 1407–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salazar-Gonzalez J. F., Bailes E., Pham K. T., Salazar M. G., Guffey M. B., Keele B. F., Derdeyn C. A., Farmer P., Hunter E., Allen S., Manigart O., Mulenga J., Anderson J. A., Swanstrom R., Haynes B. F., Athreya G. S., Korber B. T., Sharp P. M., Shaw G. M., Hahn B. H. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 3952–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollakis G., Kang S., Kliphuis A., Chalaby M. I., Goudsmit J., Paxton W. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13433–13441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCaffrey R. A., Saunders C., Hensel M., Stamatatos L. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 3279–3295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clevestig P., Pramanik L., Leitner T., Ehrnst A. (2006) J. Gen. Virol. 87, 607–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolk T., Schreiber M. (2006) Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 195, 165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pantophlet R., Wang M., Aguilar-Sino R. O., Burton D. R. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 1649–1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derdeyn C. A., Decker J. M., Bibollet-Ruche F., Mokili J. L., Muldoon M., Denham S. A., Heil M. L., Kasolo F., Musonda R., Hahn B. H., Shaw G. M., Korber B. T., Allen S., Hunter E. (2004) Science 303, 2019–2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H., Chien P. C., Jr., Tuen M., Visciano M. L., Cohen S., Blais S., Xu C. F., Zhang H. T., Hioe C. E. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 4011–4021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y., Luo L., Rasool N., Kang C. Y. (1993) J. Virol. 67, 584–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kothe D. L., Decker J. M., Li Y., Weng Z., Bibollet-Ruche F., Zammit K. P., Salazar M. G., Chen Y., Salazar-Gonzalez J. F., Moldoveanu Z., Mestecky J., Gao F., Haynes B. F., Shaw G. M., Muldoon M., Korber B. T., Hahn B. H. (2007) Virology 360, 218–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang X., Barchi J. J., Jr., Lung F. D., Roller P. P., Nara P. L., Muschik J., Garrity R. R. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 10846–10856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wain L. V., Bailes E., Bibollet-Ruche F., Decker J. M., Keele B. F., Van Heuverswyn F., Li Y., Takehisa J., Ngole E. M., Shaw G. M., Peeters M., Hahn B. H., Sharp P. M. (2007) Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1853–1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reitz M. S., Jr., Hall L., Robert-Guroff M., Lautenberger J., Hahn B. M., Shaw G. M., Kong L. I., Weiss S. H., Waters D., Gallo R. C., Blattner W. A. (1994) AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 10, 1143–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rong R., Gnanakaran S., Decker J. M., Bibollet-Ruche F., Taylor J., Sfakianos J. N., Mokili J. L., Muldoon M., Mulenga J., Allen S., Hahn B. H., Shaw G. M., Blackwell J. L., Korber B. T., Hunter E., Derdeyn C. A. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 5658–5668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen J. E., Jansson B., Gram G. J., Clausen H., Nielsen J. O., Olofsson S. (1996) Arch. Virol. 141, 291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen J. E., Nielsen C., Arendrup M., Olofsson S., Mathiesen L., Nielsen J. O., Clausen H. (1991) J. Virol. 65, 6461–6467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansen J. E., Clausen H., Nielsen C., Teglbjaerg L. S., Hansen L. L., Nielsen C. M., Dabelsteen E., Mathiesen L., Hakomori S. I., Nielsen J. O. (1990) J. Virol. 64, 2833–2840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders R. W., Venturi M., Schiffner L., Kalyanaraman R., Katinger H., Lloyd K. O., Kwong P. D., Moore J. P. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 7293–7305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gray E. S., Moore P. L., Pantophlet R. A., Morris L. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 10769–10776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Astronomo R. D., Lee H. K., Scanlan C. N., Pantophlet R., Huang C. Y., Wilson I. A., Blixt O., Dwek R. A., Wong C. H., Burton D. R. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 6359–6368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen J. E. (1992) APMIS Suppl. 27, 96–108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trkola A., Purtscher M., Muster T., Ballaun C., Buchacher A., Sullivan N., Srinivasan K., Sodroski J., Moore J. P., Katinger H. (1996) J. Virol. 70, 1100–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trkola A., Kuster H., Rusert P., Joos B., Fischer M., Leemann C., Manrique A., Huber M., Rehr M., Oxenius A., Weber R., Stiegler G., Vcelar B., Katinger H., Aceto L., Günthard H. F. (2005) Nat. Med. 11, 615–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinter A., Honnen W. J., D'Agostino P., Gorny M. K., Zolla-Pazner S., Kayman S. C. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 6909–6917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scanlan C. N., Pantophlet R., Wormald M. R., Saphire E. O., Calarese D., Stanfield R., Wilson I. A., Katinger H., Dwek R. A., Burton D. R., Rudd P. M. (2003) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 535, 205–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scanlan C. N., Pantophlet R., Wormald M. R., Ollmann Saphire E., Stanfield R., Wilson I. A., Katinger H., Dwek R. A., Rudd P. M., Burton D. R. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 7306–7321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poon A. F., Lewis F. I., Pond S. L., Frost S. D. (2007) PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu S. (2006) Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 28, 255–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu S. (2008) Hum. Vaccin. 4, 449–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang S., Kennedy J. S., West K., Montefiori D. C., Coley S., Lawrence J., Shen S., Green S., Rothman A. L., Ennis F. A., Arthos J., Pal R., Markham P., Lu S. (2008) Vaccine 26, 1098–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sailaja G., Skountzou I., Quan F. S., Compans R. W., Kang S. M. (2007) Virology 362, 331–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li M., Gao F., Mascola J. R., Stamatatos L., Polonis V. R., Koutsoukos M., Voss G., Goepfert P., Gilbert P., Greene K. M., Bilska M., Kothe D. L., Salazar-Gonzalez J. F., Wei X., Decker J. M., Hahn B. H., Montefiori D. C. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 10108–10125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanke T., Goonetilleke N., McMichael A. J., Dorrell L. (2007) J. Gen. Virol. 88, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hinkula J. (2007) Exp. Rev. Vaccines 6, 203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barouch D. H. (2008) Nature 455, 613–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin G., Nara P. L. (2007) Curr. HIV Res. 5, 514–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raska M., Moldoveanu Z., Novak J., Hel Z., Novak L., Bozja J., Compans R. W., Yang C., Mestecky J. (2008) Vaccine 26, 1541–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moore J. S., Wu X., Kulhavy R., Tomana M., Novak J., Moldoveanu Z., Brown R., Goepfert P. A., Mestecky J. (2005) AIDS 19, 381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Renfrow M. B., Cooper H. J., Tomana M., Kulhavy R., Hiki Y., Toma K., Emmett M. R., Mestecky J., Marshall A. G., Novak J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19136–19145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomana M., Novak J., Julian B. A., Matousovic K., Konecny K., Mestecky J. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 104, 73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gomes M. M., Wall S. B., Takahashi K., Novak J., Renfrow M. B., Herr A. B. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 11285–11299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Renfrow M. B., Mackay C. L., Chalmers M. J., Julian B. A., Mestecky J., Kilian M., Poulsen K., Emmett M. R., Marshall A. G., Novak J. (2007) Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 389, 1397–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Julenius K., Mølgaard A., Gupta R., Brunak S. (2005) Glycobiology 15, 153–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klein A. (2008) Adv. Clin. Chem. 46, 51–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wada Y., Azadi P., Costello C. E., Dell A., Dwek R. A., Geyer H., Geyer R., Kakehi K., Karlsson N. G., Kato K., Kawasaki N., Khoo K. H., Kim S., Kondo A., Lattova E., Mechref Y., Miyoshi E., Nakamura K., Narimatsu H., Novotny M. V., Packer N. H., Perreault H., Peter-Katalinic J., Pohlentz G., Reinhold V. N., Rudd P. M., Suzuki A., Taniguchi N. (2007) Glycobiology 17, 411–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gao F., Li Y., Decker J. M., Peyerl F. W., Bibollet-Ruche F., Rodenburg C. M., Chen Y., Shaw D. R., Allen S., Musonda R., Shaw G. M., Zajac A. J., Letvin N., Hahn B. H. (2003) AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 19, 817–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou T., Xu L., Dey B., Hessell A. J., Van Ryk D., Xiang S. H., Yang X., Zhang M. Y., Zwick M. B., Arthos J., Burton D. R., Dimitrov D. S., Sodroski J., Wyatt R., Nabel G. J., Kwong P. D. (2007) Nature 445, 732–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grundner C., Mirzabekov T., Sodroski J., Wyatt R. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 3511–3521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu J., Hellerstein M., McDonnel M., Amara R. R., Wyatt L. S., Moss B., Robinson H. L. (2007) Vaccine 25, 2951–2958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Balzarini J. (2007) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 583–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grigorian A., Lee S. U., Tian W., Chen I. J., Gao G., Mendelsohn R., Dennis J. W., Demetriou M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20027–20035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wainberg M. A., Kendall O., Gilmore N. (1988) CMAJ 138, 797–807 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.