Abstract

As a whole, integral membrane proteins represent about one third of sequenced genomes, and more than 50% of currently available drugs target membrane proteins, often cell surface receptors. Some membrane protein classes, with a defined number of transmembrane (TM) helices, are receiving much attention because of their great functional and pharmacological importance, such as G protein-coupled receptors possessing 7 TM segments. Although they represent roughly half of all membrane proteins, bitopic proteins (with only 1 TM helix) have so far been less well characterized. Though they include many essential families of receptors, such as adhesion molecules and receptor tyrosine kinases, many of which are excellent targets for biopharmaceuticals (peptides, antibodies, et al.). A growing body of evidence suggests a major role for interactions between TM domains of these receptors in signaling, through homo and heteromeric associations, conformational changes, assembly of signaling platforms, etc. Significantly, mutations within single domains are frequent in human disease, such as cancer or developmental disorders. This review attempts to give an overview of current knowledge about these interactions, from structural data to therapeutic perspectives, focusing on bitopic proteins involved in cell signaling.

Key words: bitopic membrane proteins, transmembrane domains, transmembrane signaling, helix-helix interactions, receptors

Introduction: Transmembrane (TM) Domains Structure and Interactions

The importance of membrane proteins cannot be underestimated as they account for 25–30% of all proteins (ORFs) identified in sequenced genomes in eukaryotes and prokaryotes.1,2 They can be classified as transmembrane or peripheral, the membrane-spanning domains being structured as beta-sheets in bacteria and mitochondria or in majority as alpha helices. They represent more than 50% of all currently available drug targets.3 Membrane proteins are critical in a diverse array of cellular functions, such as cell-cell communication, detection of environmental changes, transport of substances inside and outside of cells, energy transduction, enzymatic activities. They also have a structural role in maintaining cell shape, size and polarity. In multi-cellular eukaryotes, membrane proteins are also more specialized as receptors for many extracellular signals (hormones, growth factors, neurotransmitters), recognition molecules in the immune system and adhesion molecules. Other important classes of membrane interacting peptides such as amphipathic helices, antimicrobial peptides and cell-penetrating peptides will not be discussed here.4–7

The long-standing structural view of biological membranes known as the fluid-mosaic model was proposed by Singer and Nicolson almost 40 y ago.8 This model gave an initial vision where low concentrations of proteins were embedded in a fluid “sea” of lipids. This view has now become more complex to take into account the importance of protein-protein and protein-lipid interactions, the crowding of proteins at the cell surface and the existence of complex specialized “domains” associating specific proteins and lipids and assuming discrete functions.9 Indeed, it was recognized long ago that TM and membrane-associated proteins occupy environments in the cell membrane where the protein concentration in two dimensions is quite large and can exert a large influence on clustering and thus functions.10 This evolution of the model reflects also the highly dynamic nature of intramembrane interactions.7,11,12 The contribution of lipids to the complexity of membrane organization and the regulation of membrane bioactivities is now well recognized and described by the lipid raft concept.13,14

Concerning the major problem of protein insertion in the membrane lipid bilayer, the two-stage model was proposed 20 y ago.15 Its main tenets, the insertion of independently stable helices across the membrane, followed by helix-helix interactions to form higher order structures still hold true. The model has been more recently extended to a third stage which considers events such as folding of extracellular loops, insertion of peripheral domains and quaternary structure formation.16

In this model, the lateral association of TM helices within the lipid bilayer is the second stage in the folding of membrane proteins. Dimerization of TM helices is the simplest example of such lateral association, and has been much studied in the context of polytopic membrane protein assembly. But, it may also play a role in signaling across cell membranes by associating two similar or different proteins in an active (or inactive) dimer or by creating larger oligomeric structures.17 Many examples of such membrane complexes are known, e.g., the photosynthetic apparatus,18 ATPases,19 virus assembly machinery,20 immune signalling,21–23 G protein-coupled receptors,24,25 etc.

It is becoming increasingly clear that protein interactions, both transient and stable, are far more extensive than originally appreciated. These protein complexes can present a very wide range of stabilities and form highly coordinated networks that govern biological processes. This is true for soluble proteins, but also for membrane proteins. Thus, in this context, the role attributed to membrane-spanning helices has changed dramatically over the past 10 years. Once mostly regarded as mere membrane anchors, TM domains are now recognized as full-time actors of protein-protein interactions. These interactions may be of exquisite specificity in mediating assembly of stable membrane protein complexes from cognate subunits. Further, they can be reversible and regulatable by external factors to allow for dynamic changes of protein conformation in biological function. Finally, these helices are increasingly regarded as dynamic domains. Many aspects of this topic have recently been reviewed in excellent papers.7,11,12,26–41 A brief summary of current knowledge, obtained through biophysical, biochemical, cell biological and genetic studies can be put forward:

TM helices are usually 20–23 amino-acids long, with a large over-representation of hydrophobic residues. Polar residues are rare, especially negatively charged ones, whereas single-spanning segments are more hydrophobic than multi-spanning helices.30,42

-

Analysis of polytopic membrane structures and studies on model or natural single TM peptides has provided many insights on packing “rules” for TM helices. Sequence and geometric motifs have been found to drive these interactions, in a similar way as small modular domains (such as leucine zippers) that mediate soluble proteins interactions. The majority of these motifs can be classified in a rather limited number.31,38 The geometry of these packing motifs is quite variable with right-hand or left-hand crossing motifs, and crossing angles as large as 40°. Surprisingly, Walters and DeGrado found out that about two thirds of these motifs pack small chain amino-acids (Gly, Ala and Ser).38 In these motifs, the small amino-acids are separated by three other residues, thus been usually called GxxxG or GX3G motif or GAS motif. This motif was first recognized and much studied in the case of glycophorin A (see below) and has been characterized now in many other examples of interacting TM helices. Other characteristic motifs contain polar residues which contribute hydrogen bonds or charged residues which make static interactions.43,44

A word of caution: the existence of one such short interaction short motifs in a TM sequence does not necessarily imply a significant interaction. For instance, about one third of GxxxG motifs in a non-redundant database of membrane protein structures are not interacting with another helix (Duneau JP, unpublished results). And, it has to be stressed that residues adjacent to a sequence motif also contribute to the interactions.45–48

Associations between helical TM domains are dynamic by nature. Different types of motion of TM α helices have been described: lateral translation, piston, rotation parallel to the membrane (pivot or tilt) and rotation perpendicular to the membrane.11,12 The dynamic character of these interactions is of prime importance for cell signaling, which absolutely requires the capacity to be regulated and reversibility.17

Single-Spanning Membrane Proteins: A Very Large “Family” with Very Diverse Functions

In 1992, Bormann and Engelman concluded their review entitled, “Intramembrane helix-helix association in oligomerization and transmembrane signaling” 49 with this prediction: “An oligomerization/conformational change model would predict that new sites of close contact would occur between the domains of the receptor molecule, some of which may be between the transmembrane helices. Therefore, experimenters should be able to generate peptides or small molecules that can specifically interfere with either the oligomerization or generation of new close-contact sites involved in the conformational change of the receptor that leads to signaling. In this way, specific receptors might be targeted for inhibition or possibly activation using binding events inside the bilayer.”

This somewhat prophetic view has been slow to materialize, but recent years have seen much progress in our knowledge of structural as well as functional aspects of helix-helix interactions in membranes. As several excellent reviews have recently been published on many facets of these interactions (see above), this review will focus on a sub-class of membrane proteins, the single-spanning or bitopic proteins. Strikingly, this is the most abundant membrane protein class, representing more than half of all membrane protein in analyzed genomes.2,50,51 Comparative genomics have allowed for structural/functional classifications of membrane proteomes. Unsurprisingly, it was verified that eukaryotes have a higher proportion of proteins for communication since multicellular organisms require a strict control of cell-interactions.52 Figure 1 shows the comparative distribution of bitopic proteins from human and E. coli genomes.

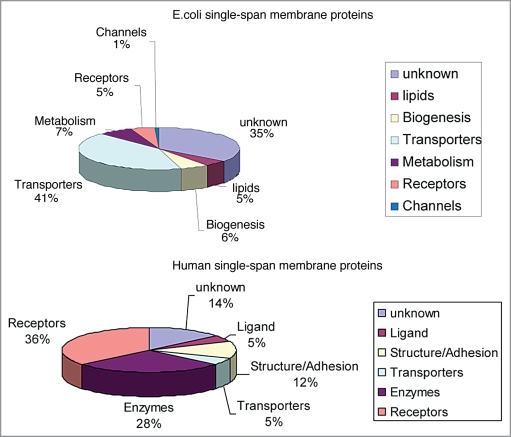

Figure 1.

A pie chart representation of the distribution of single-spanning TM proteins in E. coli and humans according to their function. Data were replotted from Daley et al. and Almen et al.176,177

Remarkably, proteins associated with signaling (receptors and ligands), cell structure and adhesion, represent about 50% of the total in the human genome. It should be stressed that such estimations have to be considered with care because of the difficulty of predicting precisely TM segments vs. hydrophobic signal sequences. Nevertheless, it can be noted that many of these bitopic proteins do participate in the regulation of cell adhesion, cell migration and cell proliferation and differentiation. A short list includes receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), many of their ligand precursors (e.g., EGF family), immunoglobulin superfamily receptors, integrins, plexins, syndecans, neuropilins, cadherins and so on.

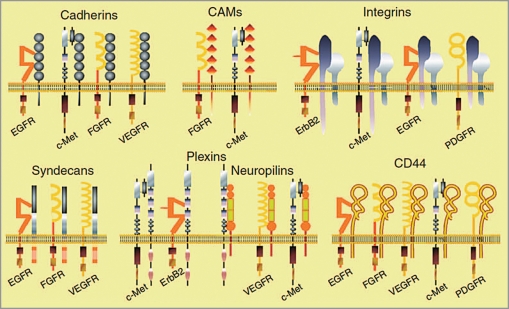

The presence in that list of adhesion proteins and receptors is quite intriguing since they have very tight functional connections and they are now thought as being partners in signaling (Fig. 2).53 Interestingly, it has been shown that the TM segments of bitopic proteins are usually more conserved than the remainder of the protein, and more significantly, one particular side of the helix is conserved, pointing to conservation of potential interaction motifs.34

Figure 2.

Examples of complexes between cell adhesion molecules and receptors tyrosine kinases. Reprinted from Orian-Rousseau V, Ponta H. Adhesion proteins meet receptors: a common theme? Adv Cancer Res. 2008; 101:63–92.53 Copyright 2008. Printed with permission from Elsevier.

Experimental Evidence for TM Domain Importance

Early evidence for the importance of helix-helix interactions in integral membrane proteins assembly and oligomerization came in the late 80s from the first crystal structures (bacteriorhodopsin and photosynthetic reaction centers) and mutational analysis of polytopic and bitopic proteins.54 Highly specific interactions between TM helices had already been demonstrated, the most prominent examples being glycophorin A and M13 phage coat protein, both forming SDS resistant dimers, as well as phospholamban which forms pentamers. Glycophorin A was the first protein for which a specific role of TM helices interactions was evidenced, and became the paradigm for these intramembrane interactions.40,55 Many more examples of such interactions have since been described, although a comprehensive understanding of structure-function relationships has yet to be achieved.

To date more than 300 publications dealing with helical TM domain interactions of membrane proteins can be found, not counting studies of de novo designed sequences.26,56,57 Some extensive lists can be found in recent reviews.26,28 In Table 1, we present a selective list of such TM peptides associations limited to those bitopic proteins playing a role in cell adhesion and migration, and more loosely in cell signaling. In this table we give some indications on the techniques used, with reporter assay representing the Toxcat method and its derivatives, and cell assay meaning all biochemical and functional techniques used in intact cells. Molecular dynamics simulations and the numerous physico-chemical methods used in many cases are not mentioned, as much more detail can be found in the review by Bordag and Keller.26 TM sequence data with motifs are to be found in Rath et al.28

Table 1.

List of selected bitopic proteins with experimentally determined TM peptide association(s)

| Protein (UniProtKB ID) | Function | Method(s) | Reference(s) |

| I. Receptors | |||

| All RTKs (n = 58) | RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase | Reporter assay | 108 |

| EGFR family (erbB 1–4)(P00533, P04626, P21860, Q15303) | RTK | Reporter assay FRET Cell assay | 74, 75, 109,79, 110,101, 111–113 |

| FGFR 1–4, fibroblast growth factor receptors (P11362, P21802, P22607, P22455) | RTK | Cell and reporter assays, FRET | 114–121 |

| VEGFR-2 (P35968) | RTK | Cell assay | 122 |

| PDGFR (P16234, P09619) | RTK | Cell assay | 59–62, 123 |

| RET (P07949) | RTK | Cell assay | 124 |

| Erythropoietin receptor (P19235) | Cytokine receptor | Cell assay | 125–129 |

| PRL-R, prolactin receptor (P16471) | Cytokine receptor | Cell assay | 130 |

| EphA1, Ephrin type-A receptor 1 (P21709) | RTK | FRET | 131 |

| Insulin & IGF-1 receptors (P06213, P08069) | RTK | Cell assay, FRET | 132–134 |

| Receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatases | phosphatases | Reporter assay | 135 |

| Neuropilin 1 (P97333) | Co-receptor for semaphorins and VEGF | Cell and reporter assays, FRET | 103, 136 |

| T-cell receptor subunits | Immune response | Cell and reporter assays, FRET, Flow cytometry | 137–139 |

| major histocompatibility complex class II (alpha and beta chains) | Immune response | Cell assay | 140 |

| II. Adhesion molecules | |||

| Integrins (alpha and beta families) | Cell-Adhesion receptors | Cell and reporter assays | 93, 141–146 |

| Syndecans (P18827, P34741, O75056, P31431) | Cell surface adhesion co-receptors | Reporter assay | 147, 148 |

| Myelin protein P0 (P25189) | Myelin adhesion | Reporter assay Cell assay | 149 |

| Cadherins (P12830, O15943) | Calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecules | Cell and reporter assays | 150, 151 |

| Synaptobrevin-2 (P63027) | Targeting and fusion of transport vesicles | Cell and reporter assays | 152, 153 |

| III. Others | |||

| Glycophorin-A (P02724) | Unknown | Cell and reporter assays, FRET, etc., | 40, 67, 154–157 |

| Bnip3 (Q12983) | Apoptosis inducer | Reporter assay | 72, 158 |

| APP, amyloid precursor protein (P05067) | Synapse formation regulator | Cell assay | 159–162 |

From left to right, columns give the name of protein with its ID in the UniProt Protein knowledgebase (www.uniprot.org/), function of the protein, methods used and references.

Some features of this summary table can be underlined. First, many examples come from the RTK family. This is not surprising in view of the great importance of this family of receptors in the control of cell proliferation and differentiation and its roles in pathologies such as cancer or skeletal disorders. Also, one of the first characterized disease-causing mutations in a TM segment was found in Neu/erbB2, which was initially identified as an oncogene by NIH/3T3 transfection analysis of cDNA from ethylnitrosourea-induced rat neuroblastomas. This also led to the delineation of an interaction motif resembling that of glycophorin A, fueling research on the role of the TM domains in many other RTKs. It is also remarkable that most interactions in Table 1 concern homodimers. Again technical difficulties are certainly a major factor in the paucity of studies concerning hetero-associations which can certainly be very important for assembly of complexes.

As many of the most important examples of TM-TM helices interactions in cell signaling are discussed in detail in other contributions of this focus issue, we will only address very briefly one other example.

Viral proteins are known to interfere with human TM receptors to gain access into a cell or interfere with cellular signal cascades. Sometimes they use TM domains to alter membrane receptor functions, and thus disturb cellular processes and cause disease.58 A very interesting example of such interactions is the activation of the PDGFbeta receptor, a RTK, by the bovine papillomavirus oncoprotein E5.59 The E5 protein binds directly and specifically to the transmembrane domain of the PDGFbeta receptor, inducing receptor dimerization, autophosphorylation and mitogenic signaling. Wild-type E5 protein and various mutants have also been shown to form trimers, tetramers, and even higher order oligomers.60 The TM domain of PDGFbeta receptor itself displays a strong oligomerization behavior, forming dimers and trimers in natural membranes and detergents. These interactions are mediated by a leucine-zipper-like motif and regulated by the juxtamembrane regions.61 Insight about these interactions has led to a very elegant genetic approach to isolate small, artificial TM proteins with biological activity, using the E5 protein as a template. Several small proteins that specifically activated the human EPO receptor, but not anymore the PDGF receptor, were obtained. This finding represents a novel strategy to isolate small artificial proteins that can affect diverse membrane proteins.62

Table 2 presents disease-associated mutations in the TM domains of bitopic proteins. Again RTKs are over-repre-sented.31,63,64 The most salient feature is that most mutations represent the replacement of an hydrophobic residue by a polar one. It has been shown that in TM domains, mutations involving polar residues, and ionizable residues in particular (notably arginine), are more often associated with protein malfunction than in soluble proteins.65

Table 2.

Selected examples of disease-associated mutations in the TM domains of bitopic proteins

| Protein (OMIM ID) | Function | Disease(s) | Mutation(s) | Reference(s) |

| I. Receptors | ||||

| erbB 2 (*164870) | RTK | Neuroblastoma (rat) Breast cancer polymorphism | V664E I655V | 111, 163,164 |

| FGFR family | Dysplasias : | |||

| FGFR1 (*136350) | Osteoglophonic dysplasia | C379R, etc., | 165 | |

| FGFR2 (*176943) | RTK | Beare-Stevenson Cutis gyrata syndrome | Y375C | 166 |

| FGFR3 (*134934) | Achondroplasia, Crouzon syndrome with Acanthosis nigricans | G380R, A391E, etc., | 167–169 | |

| FGFR4 (*134935) | Cancers | G 388R | 170 | |

| IL-2 receptor beta chain (*146710) | Receptor for interleukin-2 | Visceral leishmaniasis | G245R | 171 |

| II. Adhesion molecules | ||||

| Myelin Protein P0 (*159440) | Major structural protein of peripheral myelin | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Dejerine-Sottas syndrome | I162M, G163R, G167R | 172–174 |

| TACI (*604907) | Tumor necrosis factor receptor | immunodeficiency | A181E | 175 |

From left to right, columns give the name of protein with its ID in the OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/), function of the protein, nature of the associated disease(s), mutation(s) and references.

To summarize this brief overview, a large body of recent and less recent experimental evidences concur to demonstrate that intramembrane interhelical interactions are definitely more widespread than previously considered for bitopic proteins. The functional effects of mutations in the TM domains of these proteins in disease confirm a pivotal role for these interactions. The next section will survey the current structural understanding of interhelix interactions in bitopic proteins.

Structural Data: NMR and Modelling

Despite their obvious importance, the effectiveness of tools to study the structure of integral membrane proteins lags far behind that of water-soluble proteins. This is due to several interlinked reasons: the difficulties to solubilize and purify these hydrophobic proteins, the disordered nature of their lipid environment and the complex nature of many membrane proteins which are oligomers of one or several polypeptides.30,66 One major consequence of these technical hurdles is the under-representation of membrane protein structures in the PDB database. At the end of 2008 and 2009, only 180 and 217 respectively, unique structures of membrane proteins were available (http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/Membrane_Proteins_xtal.html).27 Although progress is rapid, this to be compared with about 20,000 known structures for soluble proteins. Also for many membrane proteins, only the structure of soluble sub-domains is known, which leads to incomplete understanding of structure-function relationships in these usually complex proteins. The situation is somewhat worse for bitopic membrane proteins, for which less than ten structures are available, be they monomeric or dimeric. This neglect is certainly due to several factors. The usual difficulties to express, purify and obtain suitable environment for crystallization or NMR are possibly worsened for bitopic proteins which can be less stable. Also, the prevalent belief until recently that these single helices are mere membrane anchors made them unworthy targets for structural studies.

Structural data.

For bitopic proteins, the very few available structures were obtained by NMR. Some are monomeric structures, such as M13 major coat protein or sarcolipin (www.drorlist.com/nmr/MPNMR.html).30 Only seven structures of dimers of TM helices, to date, have been deposited in the PDB. The first one was Glycophorin A,67 followed later by a few TM homodimers from RTKs (erbB2, EphA1 and EphA2),68–70 subunit ξ of the TCR,71 Bcl2 (an apoptotis regulator acting on mitochondrial membranes)72 and only one heterodimer of integrin subunits.73 These structures are depicted in Figures 3 and 4, and a summary of the experimental conditions is given in Table 3.

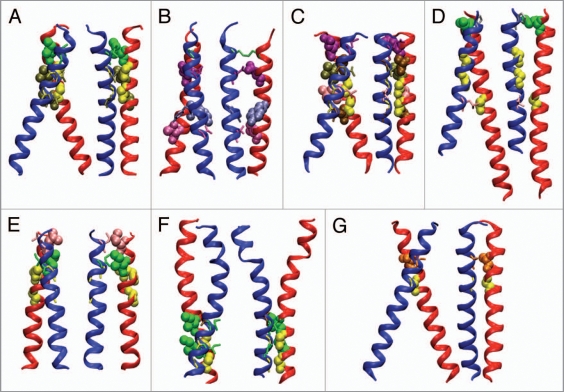

Figure 3.

Views of TM helix dimer structures from NMR. For each dimer, two views are presented, one showing the crossing angle and the second, rotated by 90 degrees around the (pseudo)-symmetry axis, showing the structure of the interface. Structures are: (A) Glycophorin A (1afo);67 (B) ξ-ξ dimer of T cell receptor (2 hac);71 (C) Receptor tyrosine kinase EphA1 (2k1k);69 (D) Integrin alphaIIb-beta3 TM complex (2k9j);73 (E) Receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 (2k9y);70 (F) BNip3 TM domain dimer (in mitochondrial outer membrane) (2ka1);72 (G) TM domain of growth factor receptor ErbB2 (2jwa).68 Properties fo the structures are summarized in Table 1. Residues belonging to dimerization motifs or participating in dimer contacts are outlined in space-filling or stick representation and colored by amino acid type: Gly (yellow), Ala (brown), Val (tan), Leu (pink), Ile (green), Glu/Asp (purple), Ser (orange), Thr (mauve), Pro (gray), Tyr (blue-gray), Cys (lime). Molecular graphics rendered with VMD.178

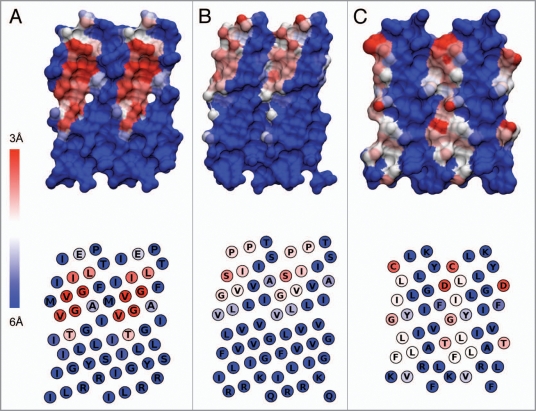

Figure 4.

Another view of TM helix dimer structures. Projection of helical surfaces of each helix in a dimer were made with Ptuba78 and colored according to an inter-helix distance scheme, with deep red being the closest (3 Å) and deep blue the farthest (6 Å). A single helix projection is shown for homodimers (upper row), with the corresponding sequence in the lower row. Structures are: (A) Glycophorin A (1afo);67 (B) TM domain of growth factor receptor ErbB2 (2jwa);68 (C) ξ-ξ dimer of T-cell receptor (2 hac).71 Molecular graphics rendered with VMD.178

Table 3.

Summary of experimental conditions and geometry of TM helix dimer structures represented in Figure 3

| Structure | Experimental conditions | pH | Dimer motif | Contact pairs (bold for polar contacts) | Angle |

| GpA (1afo) | 5% DPC micelles | 6.0 | G79X3G | I76, G79-V80, G83-V84 | R-40° |

| ξ-ξ (2hac) | DPC/SDS 5:1 micelles | 7.0 | none | C2 (disulfide), D6, L9, Y12-T17 | L |

| EphA1 (2k1k, 2k1l) | DMPC/DHPC 1:4 | 4.3 6.3 | A550X3GX3G, A560X3G? | E547, A550-V551, G554-L555, G558-A559 | R −44° |

| integrin (2k9j) | DHPC/POPC/POPS or DHPC/DMPC | 7.4 | G972X3G (αIIb) | P965-I693, L980-G708 | R −25° |

| EphA2 (2k9y) | DMPC/DHPC 1:4 | 5.0 | G540X3G (outward-facing) | L535, I538-G539 | L 20° |

| BNip3 (2j5d) | DMPC/DHPC 1:4 | 5.0 | A176X3GX3G | S172-H173, G180, G180-I181 | R −45° |

| BNip3 (2ka1, 2ka2) | DPC/DPPC | 5.1 | A176X3GX3G | S172-H173, G180, G180-I181 | R −34° |

| ErbB2 (2jwa) | DMPC/DHPC bicelles | 5.0 | T652X3SX3G | S656, G660 | R −42° |

A few facts are striking about the structures depicted in Figure 3, besides their very small number and the fact that all but one were determined in the past four years. The dimers are generally right-handed, with the exception of the TCR ξ-ξ (zeta-zeta) dimer and the EphA2 receptor. Both of these structures, however, are atypical as far as can be told based on such a limited sample. The ξξ™ dimer is disulfide-bridged at its N-terminal end, and its other dimer interactions are mostly polar, with the exception of a Leu9-Leu9’ self-contact (which is not obvious based on the published models). The EphA2 receptor structure is unique within this limited set, as it features the classic GX3G dimerization motifs facing away from the dimer interface. Instead, dimerization is mediated by a heptad repeat motif, and the authors suggest that switching between dimerization modes involving either motif could have functional significance, as has been proposed for other families of RTKs.74–76

Common features do emerge among the right-handed dimer structures. All are mediated by GpA-like small-residue-containing dimerization motifs spanning two or three helical turns. Two significant sources of variation remain: the location of the dimer motif in the TM sequence, which results in the helices being pinned together at various heights in the membrane, and the deviation of the TM secondary structure from ideal α-helices. When extracting the latter information from NMR-based models, the possible presence of arbitrary restraints on secondary structure should be kept in mind. In recent structures, such restraints would include terms in the empirical potential used for simulation-based refinement; predicted secondary structures have been shown to vary depending on the choice of potential.77 The fewer the NMR restraints, the more model refinement must rely on molecular interaction potentials. Taking this trend to its limit, purely physics-based approaches for ab initio prediction of TM dimer structures seem increasingly usable.

Another informative representation of the structure of helix dimers is provided by the projection of the helix surface in a dimer, as made with Ptuba (Fig. 4).78 Ptuba was developed to simplify the visualization of the surfaces of 3D helices as pseudo 2D projections that can be color coded to represent various aspects of their properties. Briefly, this software “unfolds” the 3D structure of an helix and draws it as a duplicated surface. In Figure 4, the unfolded surfaces are colored according to the distance between atoms of the two helixes in NMR structure. In the lower part of the figure, residues are indicated in one letter code and colored according to averaged distances between helices for Ca and all atoms of each residue in the dimer. Panel A depicts the surface of the glycophorin A helix where the interacting residues involve a relatively wide strip of surface with numerous closed contacts distributed along the interacting patch. The central panel (Fig. 4B) shows the surface of one ErbB2 helix, which in spite of a very similar geometry, shows a smaller interacting surface and less marked proximities than glycophorin A. This can be related to experimental data (FRET) showing that this homodimerization is weaker.79,80 Finally, in the TCR ξ-ξ TM domains the interface extends all along one helix face but involves only a handful of very local, short-distance contacts (Fig. 4C).

From sequences to structures.

Molecular modeling and computer simulations are increasingly used for simulations of lateral association and oligomerization of TM helices. Predictions of TM interaction can rely on two distinct approaches (reviewed in Punta et al. 2007):81 homology modeling and ab initio or de novo design. The first approach mainly concerns cases where 3D templates are available, and obviously this is not the case for the association of single-spanning TM proteins. However, the glycophorin A TM NMR structure has been used as a modeling template each time a GAS motif was thought to be involved in interactions. However all GAS motifs do not necessarily lead to unique packing geometry.31,38

The other method used to predict structural organization of membrane proteins relies on de novo (knowledge based) or ab initio (thermodynamics) approaches. The principle may be formulated very simply: one has just to find pairwise interactions between TM domains. The early success of the primary algorithms are nowadays always present in strategies that concern all membrane proteins. They comprise three main tasks: first, the prediction of TM domain stretches from sequence; second, the prediction of the orientation of the TM segment relatively to the membrane and the remainder of the protein and third, the prediction of contact maps between the distinct helices. Early approaches for the prediction of TM stretches relied on propensity scales to describe the partition of the protein sequence in membrane.82 They quickly attained relatively good precision results. Today, best “modern” algorithms are able to reach 80% in accuracy at the topology level for membrane proteins. This high precision was thought to be definitively attained only by Hidden Markov Models (TMHMM)83 or Neural Networks approach (PHDhtm).84 More recently a first principle method based on the partition energetics of the translocon machinery was developed (TopPredΔG),85 which performs equally as the previous algorithms. An additional improvement of the predictor using HMM (SCAMPI) rises further the performances for correct topology prediction.85

This kind of de novo algorithm is of prime interest for single spanning TM domains which are more conserved than for polytopic proteins,34 and for which the usefulness of statistics coming from polytopic membrane proteins remains to be assessed. Also, importantly for bitopic proteins, efforts have been made to discriminate signal peptides which can be mistaken from authentic TM segments and thus lead to errors in topology.2,86 Prediction of membrane protein structure needs also a correct estimation of the orientation of helix faces relative to the membrane protein interior and exterior. Early developments involved the calculation of hydrophobic moment with physically based approaches. However the hydrophobicity difference is by far less pronounced in membrane proteins than in soluble ones. Such an approach was not proved as very useful even for multiple spanning membrane proteins.87

In recent years progress was made towards the prediction of contact maps between TM segments by including residue conservation (LIPS)88 and co-evolutionm.89 The accuracy for lipid exposed surface prediction reached 88% with LIPS. Contact map predictors were implemented using Neural Networks89 and Support Vector Machine (Tmhit).90 Their accuracy was argued to be between 31–57%. To our knowledge, those recently developed methods have not been applied to the prediction of associations of single spanning TM proteins. Probably, algorithms could be adapted to that situation; however, applying those methods to single-spanning TM domains is not obvious since divergence in sequences could not be sufficient to detect such correlated mutations. The fact that TM domains of bitopic membrane proteins are more conserved than others precludes the practical use of such methods. In fact, for a long time, prediction of interactions between single tansmembrane domain have been based on de novo approach using sophisticated molecular mechanics methods.91 The ability of such modeling to achieve good predictions has been demonstrated92 and verified experimentally (CHAMP).93 The complexity of such protocols currently precludes genome wide analysis of potential single TM associations.

In conclusion, biases in structural databases toward polytopic membrane proteins and difficulties of interpretation of evolutionary data for bitopic proteins limits the usefulness of ab initio approaches. In addition, the de novo strategy suffers from inherent complexity and, overall, a deficit of available experimental validation, particularly at the structural level. So more work needs to be done to measure structural and environmental constraints that specifically apply on single TM assemblies. NMR and other experimental data, including biological assays, mutational scanning and biophysical measurements should feed strategies to develop new kinds of prediction algorithms optimized towards this class of proteins.

Perspectives and Questions

Together with other reviews in this focus issue, this overview of TM-TM interactions in bitopic proteins signaling demonstrates their functional importance. Nevertheless, it is clear that many questions remain to be answered, and much technical progress is needed before we get a comprehensive knowledge of all the structural and dynamic aspects of interactions (homologous and heterologous) between intramembrane helices. This understanding is necessary to describe protein-mediated information transfer across the membrane during cell signaling.

It must be stressed that the common view that bitopic membrane receptors activation or inactivation is due to ligand-activated homodimerization (or heterodimerization) is certainly oversimplistic. Very briefly, the case of the EGFR/ErbB family receptor illustrates the limits of the “divide and conquer” strategy for multi-domains membrane proteins. Structures of nearly all the parts of ErbB receptors have now been solved through crystallography or NMR, namely extracellular, transmembrane, juxta-membrane and kinase domains. Nevertheless, it has become clear that the sum of these parts does not fully account for receptor properties, including their allosteric regulation.94,95 Moreover, the existence of large oligomers or aggregates of erbB receptors at the cell surface has been widely documented.96–98 Elucidation of the role of TM domains interactions in the assembly of such large erbB structures, and in the transfer of conformational changes through the lipid bilayer, certainly represent major challenges.

An interesting point about the interaction TM motifs evoked in the introduction is that they usually lie on a well defined “face” of the helix. Other motifs can exist on other sides, opening the possibility for higher order interactions with other TM domains. In this way, interactions between TM helices could serve as “adapter domains” participating in the assembly of dynamic and evolving multimeric complexes with new functions.

Short hydrophobic peptide mimics of TM segments have already proven useful as tools to decipher the role of interactions between TM helices, notably in cultured cell models (see Table 1). But could such peptides be considered as drug templates? In general, contrary to early disdain towards the use of peptides or short proteins, much emphasis is now put on the interest of biologicals, in general, and peptides in particular. Furthermore, inhibition of protein-protein interactions is beginning to hold its promises.99 A spectacular example is the 36-amino-acid peptide enfuvirtide (Fuzeon™, Roche), which targets the HIV-1 envelope protein and inhibits CD4 receptor binding thereby preventing HIV-1 entry into the host T cell.

Finally, very few examples of TM peptide activity in animal models are found in the literature.100–103 One very recent example is the demonstration by some of us that a synthetic peptide mimicking the transmembrane domain of Neuropilin-1 (NRP1) blocks the biological functions of this Plexin and VEGFR coreceptor.136 The sequence of this TM domain contains two adjacent GxxxG motifs, and various biochemical and functional assays have revealed the remarkable specificity of the strategy. In particular, FRET analysis showed the lack of hetero-interactions between wild type and mutant version of the peptide (3 glycines of the motif replaced by 3 valines). At the cellular level, this peptide blocked Semaphorin-3A induced differentiation of PC12 cells while not affecting NGF-induced PC12 differentiation, thereby demonstrating a selective inhibition of NRP1-dependent pathways. These interesting properties pushed us to examine how this peptide could be used as a novel therapeutic agent in a pathological context. To this end, we have explored the migratory and proliferative capacity of brain tumor cells in its presence. This choice was motivated by the major role of NRP1 in brain tumor progression and tumor associated angiogenesis, a key step for cancer progression. Strikingly, we found that the peptide blocked VEGF-induced endothelial and tumor cell migration and proliferation in vitro. Moreover, our data demonstrate in orthotopic and heterotopic graft models of brain tumors that the growth of rat and human glioma is strongly reduced (up to 80%) in the presence of the peptide.103 Thus, this preclinical study suggests that targeting TM domain interactions possibly represents a clear alternative to current protein inhibitors.

Indeed, much progress has recently been made in developing techniques that will help designing molecules targeting protein TM domains. These include truncating native TM regions such as the core peptide,102 directed evolution with the E5 protein62 and computational design (CHAMP) with integrins.93 It is also interesting to note that some derivatives of TM peptides, containing D-amino acids or modified with hydrophobic moieties, are also active.104–107 These examples all demonstrate that it is possible to design small peptides or peptidomimetics that specifically modulate much larger target membrane proteins by acting within cell membranes. While several questions related to the stability, biodistribution or toxicity of such TM peptides have yet to be addressed, these developments represent the first steps towards a new generation of peptide drugs.

In conclusion, we certainly have only seen the tip of the iceberg. More studies using a wide variety of methods, from single TM helices to integrated views in biochemical (e.g., lipid vesicles) and cellular contexts are required to describe TM-TM interactions, together with contribution of the increasing power and pertinence of computational methods. A better understanding of structure-function relationships of these interactions is necessary to apprehend such fundamental biological processes as membrane biogenesis, membrane protein folding and assembly in the plane of the membrane, as well as their contribution to the “vertical” information transfer across the membrane.

Acknowlegements

Financial support from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- NRP1

neuropilin-1

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- TM

transmembrane

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/12430

References

- 1.Stevens TJ, Arkin IT. Do more complex organisms have a greater proportion of membrane proteins in their genomes? Proteins. 2000;39:417–420. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(20000601)39:4<417::aid-prot140>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fagerberg L, Jonasson K, von Heijne G, Uhlen M, Berglund L. Prediction of the human membrane proteome. Proteomics. 2010;10:1–9. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arinaminpathy Y, Khurana E, Engelman DM, Gerstein MB. Computational analysis of membrane proteins: the largest class of drug targets. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:1130–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reshetnyak YK, Segala M, Andreev OA, Engelman DM. A monomeric membrane peptide that lives in three worlds: in solution, attached to and inserted across lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 2007;93:2363–2372. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.109967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glukhov E, Burrows LL, Deber CM. Membrane interactions of designed cationic antimicrobial peptides: The two thresholds. Biopolymers. 2008;89:360–371. doi: 10.1002/bip.20917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahalka AK, Kinnunen PK. Binding of amphipathic alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides to lipid membranes: lessons from temporins B and L. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1600–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bechinger B. A dynamic view of peptides and proteins in membranes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3028–3039. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer SJ, Nicolson GL. The fluid mosaic model of the structure of cell membranes. Science. 1972;175:720–731. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4023.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelman DM. Membranes are more mosaic than fluid. Nature. 2005;438:578–580. doi: 10.1038/nature04394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grasberger B, Minton AP, DeLisi C, Metzger H. Interaction between proteins localized in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6258–6262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews EE, Zoonens M, Engelman DM. Dynamic helix interactions in transmembrane signaling. Cell. 2006;127:447–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langosch D, Arkin IT. Interaction and conformational dynamics of membrane-spanning protein helices. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1343–1358. doi: 10.1002/pro.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindner R, Naim HY. Domains in biological membranes. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:2871–2878. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 2010;327:46–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popot JL, Engelman DM. Membrane protein folding and oligomerization: the two-stage model. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4031–4037. doi: 10.1021/bi00469a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelman DM, Chen Y, Chin CN, Curran AR, Dixon AM, Dupuy AD, et al. Membrane protein folding: beyond the two stage model. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:122–125. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cebecauer M, Spitaler M, Serge A, Magee AI. Signalling complexes and clusters: functional advantages and methodological hurdles. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:309–320. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson N, Yocum CF. Structure and function of photosystems I and II. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:521–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devenish RJ, Prescott M, Rodgers AJ. The structure and function of mitochondrial F1F0-ATP synthases. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;267:1–58. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)00601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moradpour D, Penin F, Rice CM. Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:453–463. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudolph MG, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. How TCRs bind MHCs, peptides and coreceptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:419–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigalov AB. SCHOOL model and new targeting strategies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;640:268–311. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09789-3_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vamosi G, Bodnar A, Damjanovich S, Nagy P, Varga Z, Damjanovich L. The role of supramolecular protein complexes and membrane potential in transmembrane signaling processes of lymphocytes. Immunol Lett. 2006;104:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milligan G. G protein-coupled receptor hetero-dimerization: contribution to pharmacology and function. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozenfeld R, Devi LA. Receptor heteromerization and drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bordag N, Keller S. Alpha-helical transmembrane peptides: a “divide and conquer” approach to membrane proteins. Chem Phys Lipids. 2010;163:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White SH. Biophysical dissection of membrane proteins. Nature. 2009;459:344–346. doi: 10.1038/nature08142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rath A, Tulumello DV, Deber CM. Peptide models of membrane protein folding. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3036–3045. doi: 10.1021/bi900184j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrington SE, Ben-Tal N. Structural determinants of transmembrane helical proteins. Structure. 2009;17:1092–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arce J, Sturgis JN, Duneau JP. Dissecting membrane protein architecture: An annotation of structural complexity. Biopolymers. 2009;91:815–829. doi: 10.1002/bip.21255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore DT, Berger BW, DeGrado WF. Protein-Protein Interactions in the Membrane: Sequence, Structural and Biological Motifs. Structure. 2008;16:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsh D. Protein modulation of lipids and vice-versa, in membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1545–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackenzie KR, Fleming KG. Association energetics of membrane spanning alpha-helices. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zviling M, Kochva U, Arkin IT. How important are transmembrane helices of bitopic membrane proteins? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Heijne G. The membrane protein universe: what’s out there and why bother? J Intern Med. 2007;261:543–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider D, Finger C, Prodohl A, Volkmer T. From interactions of single transmembrane helices to folding of alpha-helical membrane proteins: analyzing transmembrane helix-helix interactions in bacteria. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2007;8:45–61. doi: 10.2174/138920307779941578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rath A, Johnson RM, Deber CM. Peptides as transmembrane segments: decrypting the determinants for helix-helix interactions in membrane proteins. Biopolymers. 2007;88:217–232. doi: 10.1002/bip.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walters RF, DeGrado WF. Helix-packing motifs in membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13658–13663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605878103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sachs JN, Engelman DM. Introduction to the membrane protein reviews: the interplay of structure, dynamics and environment in membrane protein function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:707–712. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.110105.142336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mackenzie KR. Folding and stability of alpha-helical integral membrane proteins. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1931–1977. doi: 10.1021/cr0404388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White SH. Membrane protein insertion: the biology-physics nexus. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:363–369. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. A mutation data matrix for transmembrane proteins. FEBS Lett. 1994;339:269–275. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herrmann JR, Panitz JC, Unterreitmeier S, Fuchs A, Frishman D, Langosch D. Complex patterns of histidine, hydroxylated amino acids and the GxxxG motif mediate high-affinity transmembrane domain interactions. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:912–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senes A, Engel DE, DeGrado WF. Folding of helical membrane proteins: the role of polar, GxxxG-like and proline motifs. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:465–479. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dawson JP, Melnyk RA, Deber CM, Engelman DM. Sequence context strongly modulates association of polar residues in transmembrane helices. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00714-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrmann JR, Fuchs A, Panitz JC, Eckert T, Unterreitmeier S, Frishman D, et al. Ionic Interactions Promote Transmembrane Helix-Helix Association Depending on Sequence Context. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melnyk RA, Kim S, Curran AR, Engelman DM, Bowie JU, Deber CM. The affinity of GXXXG motifs in transmembrane helix-helix interactions is modulated by long-range communication. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16591–16597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J, Lazaridis T. Transmembrane helix association affinity can be modulated by flanking and noninterfacial residues. Biophys J. 2009;96:4418–4427. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bormann BJ, Engelman DM. Intramembrane helix-helix association in oligomerization and transmembrane signaling. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:223–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones DT. Do transmembrane protein superfolds exist? FEBS Lett. 1998;423:281–285. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J, Rost B. Comparing function and structure between entire proteomes. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1970–1979. doi: 10.1110/ps.10101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ben-Shlomo I, Yu Hsu S, Rauch R, Kowalski HW, Hsueh AJ. Signaling receptome: a genomic and evolutionary perspective of plasma membrane receptors involved in signal transduction. Sci STKE. 2003;RE9 doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.187.re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orian-Rousseau V, Ponta H. Adhesion proteins meet receptors: a common theme? Adv Cancer Res. 2008;101:63–92. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)00404-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemmon MA, Engelman DM. Specificity and promiscuity in membrane helix interactions. FEBS Lett. 1994;346:17–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacKenzie KR, Engelman DM. Structure-based prediction of the stability of transmembrane helixìhelix interactions: The sequence dependence of glycophorin A dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3583–3590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holt A, Killian JA. Orientation and dynamics of transmembrane peptides: the power of simple models. Eur Biophys J. 2010;39:609–621. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0567-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Killian JA, Nyholm TK. Peptides in lipid bilayers: the power of simple models. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cymer F, Schneider D. Lessons from viruses: controlling the function of transmembrane proteins by interfering transmembrane helices. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:779–785. doi: 10.2174/092986708783955545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Talbert-Slagle K, DiMaio D. The bovine papillomavirus E5 protein and the PDGF beta receptor: it takes two to tango. Virology. 2009;384:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oates J, Hicks M, Dafforn TR, DiMaio D, Dixon AM. In vitro dimerization of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein transmembrane domain. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8985–8992. doi: 10.1021/bi8006252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oates J, King G, Dixon AM. Strong oligomerization behavior of PDGFbeta receptor transmembrane domain and its regulation by the juxtamembrane regions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cammett TJ, Jun SJ, Cohen EB, Barrera FN, Engelman DM, Dimaio D. Construction and genetic selection of small transmembrane proteins that activate the human erythropoietin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3447–3452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915057107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robertson SC, Tynan JA, Donoghue DJ. RTK mutations and human syndromeswhen good receptors turn bad. Trends Genet. 2000;16:265–271. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li E, Hristova K. Role of receptor tyrosine kinase transmembrane domains in cell signaling and human pathologies. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6241–6251. doi: 10.1021/bi060609y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Partridge AW, Therien AG, Deber CM. Missense mutations in transmembrane domains of proteins: phenotypic propensity of polar residues for human disease. Proteins. 2004;54:648–656. doi: 10.1002/prot.10611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mascle-Allemand C, Duquesne K, Lebrun R, Scheuring S, Sturgis JN. Antenna mixing in photosynthetic membranes from Phaeospirillum molischianum. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:5357–5362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914854107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MacKenzie KR, Prestegard JH, Engelman DM. A transmembrane helix dimer: structure and implications. Science. 1997;276:131–133. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bocharov EV, Mineev KS, Volynsky PE, Ermolyuk YS, Tkach EN, Sobol AG, et al. Spatial structure of the dimeric transmembrane domain of the growth factor receptor ErbB2 presumably corresponding to the receptor active state. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6950–6956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bocharov EV, Mayzel ML, Volynsky PE, Goncharuk MV, Ermolyuk YS, Schulga AA, et al. Spatial structure and pH-dependent conformational diversity of dimeric transmembrane domain of the receptor tyrosine kinase EphA1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29385–29395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803089200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bocharov EV, Mayzel ML, Volynsky PE, Mineev KS, Tkach EN, Ermolyuk YS, et al. Left-Handed Dimer of EphA2 Transmembrane Domain: Helix Packing Diversity among Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. Biophys J. 2010;98:881–889. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Call ME, Schnell JR, Xu C, Lutz RA, Chou JJ, Wucherpfennig KW. The structure of the zetazeta transmembrane dimer reveals features essential for its assembly with the T cell receptor. Cell. 2006;127:355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sulistijo ES, Mackenzie KR. Structural basis for dimerization of the BNIP3 transmembrane domain. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5106–5120. doi: 10.1021/bi802245u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lau TL, Kim C, Ginsberg MH, Ulmer TS. The structure of the integrin alphaIIbbeta3 transmembrane complex explains integrin transmembrane signalling. EMBO J. 2009;28:1351–1361. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Beevers AJ, Damianoglou A, Oates JE, Rodger A, Dixon AM. Sequence dependent oligomerization of the Neu transmembrane domain suggests inhibition of conformational switching by oncogenic mutant. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2811–2820. doi: 10.1021/bi902087v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Escher C, Cymer F, Schneider D. Two GxxxG-like motifs facilitate promiscuous interactions of the human ErbB transmembrane domains. J Mol Biol. 2009;389:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gerber D, Sal-Man N, Shai Y. Two motifs within a transmembrane domain, one for homodimerization and the other for heterodimerization. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21177–21182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yoda T, Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Comparisons of force fields for proteins by generalized-ensemble simulations. Chem Phys Lett. 2004;386:460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lopera JA, Sturgis JN, Duneau JP. Ptuba: a tool for the visualization of helix surfaces in proteins. J Mol Graph Model. 2005;23:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duneau JP, Vegh AP, Sturgis JN. A dimerization hierarchy in the transmembrane domains of the HER receptor family. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2010–2019. doi: 10.1021/bi061436f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stanley AM, Fleming KG. The transmembrane domains of ErbB receptors do not dimerize strongly in micelles. J Mol Biol. 2005;347:759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Punta M, Forrest LR, Bigelow H, Kernytsky A, Liu J, Rost B. Membrane protein prediction methods. Methods. 2007;41:460–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nam HJ, Jeon J, Kim S. Bioinformatic approaches for the structure and function of membrane proteins. BMB Rep. 2009;42:697–704. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2009.42.11.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rost B, Fariselli P, Casadio R. Topology prediction for helical transmembrane proteins at 86% accuracy. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1704–1718. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bernsel A, Viklund H, Falk J, Lindahl E, von Heijne G, Elofsson A. Prediction of membrane-protein topology from first principles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7177–7181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711151105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction-the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:429–432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stevens TJ, Arkin IT. Are membrane proteins “inside-out” proteins? Proteins. 1999;36:135–143. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990701)36:1<135::aid-prot11>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Adamian L, Liang J. Prediction of transmembrane helix orientation in polytopic membrane proteins. BMC Struct Biol. 2006;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fuchs A, Martin-Galiano AJ, Kalman M, Fleishman S, Ben-Tal N, Frishman D. Co-evolving residues in membrane proteins. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3312–3319. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lo A, Chiu YY, Rodland EA, Lyu PC, Sung TY, Hsu WL. Predicting helix-helix interactions from residue contacts in membrane proteins. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:996–1003. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Psachoulia E, Marshall DP, Sansom MS. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Dimerization of Transmembrane alpha-Helices. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:388–396. doi: 10.1021/ar900211k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Samna Soumana O, Garnier N, Genest M. Molecular dynamics simulation approach for the prediction of transmembrane helix-helix heterodimers assembly. Eur Biophys J. 2007;36:1071–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yin H, Slusky JS, Berger BW, Walters RS, Vilaire G, Litvinov RI, et al. Computational design of peptides that target transmembrane helices. Science. 2007;315:1817–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.1136782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jura N, Endres NF, Engel K, Deindl S, Das R, Lamers MH, et al. Mechanism for activation of the EGF receptor catalytic domain by the juxtamembrane segment. Cell. 2009;137:1293–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lemmon MA. Ligand-induced ErbB receptor dimerization. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:638–648. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moriki T, Maruyama H, Maruyama IN. Activation of preformed EGF receptor dimers by ligand-induced rotation of the transmembrane domain. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:1011–1026. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tao RH, Maruyama IN. All EGF(ErbB) receptors have preformed homo-and heterodimeric structures in living cells. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3207–3217. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Szabo A, Horvath G, Szollosi J, Nagy P. Quantitative characterization of the large-scale association of ErbB1 and ErbB2 by flow cytometric homo-FRET measurements. Biophys J. 2008;95:2086–2096. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Arkin MR, Wells JA. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing towards the dream. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:301–317. doi: 10.1038/nrd1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.George SR, Ng GY, Lee SP, Fan T, Varghese G, Wang C, et al. Blockade of G protein-coupled receptors and the dopamine transporter by a transmembrane domain peptide: novel strategy for functional inhibition of membrane proteins in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:481–489. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lofts FJ, Hurst HC, Sternberg MJ, Gullick WJ. Specific short transmembrane sequences can inhibit transformation by the mutant neu growth factor receptor in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1993;8:2813–2820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Manolios N, Collier S, Taylor J, Pollard J, Harrison LC, Bender V. T-cell antigen receptor transmembrane peptides modulate T-cell function and T cell-mediated disease. Nat Med. 1997;3:84–88. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nasarre C, Roth M, Jacob L, Roth L, Koncina E, Thien A, et al. Peptide-based interference of the transmembrane domain of neuropilin-1 inhibits glioma growth in vivo. Oncogene. 2010;29:2381–2392. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Quintana FJ, Gerber D, Bloch I, Cohen IR, Shai Y. A structurally altered D,L-amino acid TCRalpha transmembrane peptide interacts with the TCRalpha and inhibits T-cell activation in vitro and in an animal model. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2317–2325. doi: 10.1021/bi061849g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sal-Man N, Gerber D, Shai Y. Hetero-assembly between all-L-and all-D-amino acid transmembrane domains: forces involved and implication for inactivation of membrane proteins. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:855–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gerber D, Shai Y. Chirality-independent protein-protein recognition between transmembrane domains in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:491–495. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Amon MA, Ali M, Bender V, Chan YN, Toth I, Manolios N. Lipidation and glycosylation of a T cell antigen receptor (TCR) transmembrane hydrophobic peptide dramatically enhances in vitro and in vivo function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Finger C, Escher C, Schneider D. The Single Transmembrane Domains of Human Receptor Tyrosine Kinases Encode Self-Interactions. Sci Signal. 2009;2:56. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mendrola JM, Berger MB, King MC, Lemmon MA. The single transmembrane domains of ErbB receptors self-associate in cell membranes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4704–4712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.He L, Hristova K. Pathogenic activation of receptor tyrosine kinases in mammalian membranes. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:1130–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bargmann CI, Hung MC, Weinberg RA. Multiple independent activations of the neu oncogene by a point mutation altering the transmembrane domain of p185. Cell. 1986;45:649–657. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Burke CL, Lemmon MA, Coren BA, Engelman DM, Stern DF. Dimerization of the p185neu transmembrane domain is necessary but not sufficient for transformation. Oncogene. 1997;14:687–696. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bennasroune A, Fickova M, Gardin A, Dirrig-Grosch S, Aunis D, Cremel G, et al. Transmembrane peptides as inhibitors of ErbB receptor signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3464–3474. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Webster MK, Donoghue DJ. Constitutive activation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 by the transmembrane domain point mutation found in achondroplasia. EMBO J. 1996;15:520–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Li Y, Mangasarian K, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Activation of FGF receptors by mutations in the transmembrane domain. Oncogene. 1997;14:1397–1406. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ronchetti D, Greco A, Compasso S, Colombo G, Dell’Era P, Otsuki T, et al. Deregulated FGFR3 mutants in multiple myeloma cell lines with t(4;14): comparative analysis of Y373C, K650E and the novel G384D mutations. Oncogene. 2001;20:3553–3562. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Iwamoto T, You M, Li E, Spangler J, Tomich JM, Hristova K. Synthesis and initial characterization of FGFR3 transmembrane domain: consequences of sequence modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1668:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Li E, You M, Hristova K. FGFR3 dimer stabilization due to a single amino acid pathogenic mutation. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:600–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Merzlyakov M, Chen L, Hristova K. Studies of receptor tyrosine kinase transmembrane domain interactions: the EmEx-FRET method. J Membr Biol. 2007;215:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9009-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.You M, Spangler J, Li E, Han X, Ghosh P, Hristova K. Effect of pathogenic cysteine mutations on FGFR3 transmembrane domain dimerization in detergents and lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11039–11046. doi: 10.1021/bi700986n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Peng WC, Lin X, Torres J. The strong dimerization of the transmembrane domain of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) is modulated by C-terminal juxtamembrane residues. Protein Sci. 2009;18:450–459. doi: 10.1002/pro.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dosch DD, Ballmer-Hofer K. Transmembrane domain-mediated orientation of receptor monomers in active VEGFR-2 dimers. Faseb J. 2010;24:32–38. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-132670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Talbert-Slagle K, Marlatt S, Barrera FN, Khurana E, Oates J, Gerstein M, et al. Artificial transmembrane oncoproteins smaller than the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein redefine sequence requirements for activation of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor. J Virol. 2009;83:9773–9785. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00946-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kjaer S, Kurokawa K, Perrinjaquet M, Abrescia C, Ibanez CF. Self-association of the transmembrane domain of RET underlies oncogenic activation by MEN2A mutations. Oncogene. 2006;25:7086–7095. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Constantinescu SN, Liu X, Beyer W, Fallon A, Shekar S, Henis YI, et al. Activation of the erythropoietin receptor by the gp55-P viral envelope protein is determined by a single amino acid in its transmembrane domain. EMBO J. 1999;18:3334–3347. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kubatzky KF, Ruan W, Gurezka R, Cohen J, Ketteler R, Watowich SS, et al. Self assembly of the transmembrane domain promotes signal transduction through the erythropoietin receptor. Curr Biol. 2001;11:110–115. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Seubert N, Royer Y, Staerk J, Kubatzky KF, Moucadel V, Krishnakumar S, et al. Active and inactive orientations of the transmembrane and cytosolic domains of the erythropoietin receptor dimer. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1239–1250. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ebie AZ, Fleming KG. Dimerization of the erythropoietin receptor transmembrane domain in micelles. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Becker V, Sengupta D, Ketteler R, Ullmann GM, Smith JC, Klingmuller U. Packing density of the erythropoietin receptor transmembrane domain correlates with amplification of biological responses. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11771–11782. doi: 10.1021/bi801425e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gadd SL, Clevenger CV. Ligand-Independent Dimerization of the Human Prolactin Receptor Isoforms: Functional Implications. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2734–2746. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Artemenko EO, Egorova NS, Arseniev AS, Feofanov AV. Transmembrane domain of EphA1 receptor forms dimers in membrane-like environment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:2361–2367. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cheatham B, Shoelson SE, Yamada K, Goncalves E, Kahn CR. Substitution of the erbB-2 oncoprotein transmembrane domain activates the insulin receptor and modulates the action of insulin and insulin-receptor substrate 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7336–7340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chan JLK, Lai M, Wang LH. Effect of dimerization on signal transduction and biological function of oncogenic Ros, insulin and insulin-like growth factor I receptors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:146–153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gardin A, Auzan C, Clauser E, Malherbe T, Aunis D, Cremel G, et al. Substitution of the insulin receptor transmembrane domain with that of glycophorin A inhibits insulin action. Faseb J. 1999;13:1347–1357. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.11.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Chin CN, Sachs JN, Engelman DM. Transmembrane homodimerization of receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatases. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3855–3858. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Roth L, Nasarre C, Dirrig-Grosch S, Aunis D, Cremel G, Hubert P, et al. Transmembrane domain interactions control biological functions of neuropilin-1. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:646–654. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Blumberg RS, Alarcon B, Sancho J, McDermott FV, Lopez P, Breitmeyer J, et al. Assembly and function of the T cell antigen receptor. Requirement of either the lysine or arginine residues in the transmembrane region of the alpha chain. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14036–14043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rutledge T, Cosson P, Manolios N, Bonifacino JS, Klausner RD. Transmembrane helical interactions: zeta chain dimerization and functional association with the T cell antigen receptor. EMBO J. 1992;11:3245–3254. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Fuller-Espie S, Hoffman Towler P, Wiest DL, Tietjen I, Spain LM. Transmembrane polar residues of TCRbeta chain are required for signal transduction. Int Immunol. 1998;10:923–933. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.7.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Cosson P, Bonifacino JS. Role of transmembrane domain interactions in the assembly of class II MHC molecules. Science. 1992;258:659–662. doi: 10.1126/science.1329208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Li R, Babu CR, Lear JD, Wand AJ, Bennett JS, DeGrado WF. Oligomerization of the integrin alphaIIbbeta3: roles of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12462–12467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221463098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Schneider D, Engelman DM. Involvement of transmembrane domain interactions in signal transduction by alpha/beta integrins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9840–9846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Arnaout MA, Mahalingam B, Xiong JP. Integrin structure, allostery, and bidirectional signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:381–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lin X, Tan SM, Law SK, Torres J. Two types of transmembrane homomeric interactions in the integrin receptor family are evolutionarily conserved. Proteins. 2006;63:16–23. doi: 10.1002/prot.20882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Litvinov RI, Vilaire G, Li W, DeGrado WF, Weisel JW, Bennett JS. Activation of individual alphaIIbbeta3 integrin molecules by disruption of transmembrane domain interactions in the absence of clustering. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4957–4964. doi: 10.1021/bi0526581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Yin H, Litvinov RI, Vilaire G, Zhu H, Li W, Caputo GA, et al. Activation of platelet alphaIIbbeta3 by an exogenous peptide corresponding to the transmembrane domain of alphaIIb. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36732–36741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Dews IC, Mackenzie KR. Transmembrane domains of the syndecan family of growth factor coreceptors display a hierarchy of homotypic and heterotypic interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20782–20787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708909105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Choi S, Lee E, Kwon S, Park H, Yi JY, Kim S, et al. Transmembrane domain-induced oligomerization is crucial for the functions of syndecan-2 and syndecan-4. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42573–42579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Plotkowski ML, Kim S, Phillips ML, Partridge AW, Deber CM, Bowie JU. Transmembrane domain of myelin protein zero can form dimers: possible implications for myelin construction. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12164–12173. doi: 10.1021/bi701066h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Huber O, Kemler R, Langosch D. Mutations affecting transmembrane segment interactions impair adhesiveness of E-cadherin. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:4415–4423. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Yonekura S, Ting CY, Neves G, Hung K, Hsu SN, Chiba A, et al. The variable transmembrane domain of Drosophila N-cadherin regulates adhesive activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6598–6608. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00241-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Bowen ME, Engelman DM, Brunger AT. Mutational analysis of synaptobrevin transmembrane domain oligomerization. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15861–15866. doi: 10.1021/bi0269411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Laage R, Langosch D. Dimerization of the synaptic vesicle protein synaptobrevin (vesicle-associated membrane protein) II depends on specific residues within the transmembrane segment. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:540–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Lemmon MA, Flanagan JM, Hunt JF, Adair BD, Bormann BJ, Dempsey CE, et al. Glycophorin A dimerization is driven by specific interactions between transmembrane alpha-helices. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7683–7689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.MacKenzie KR, Engelman DM. Structure-based prediction of the stability of transmembrane helix-helix interactions: the sequence dependence of glycophorin A dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3583–3590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Fisher LE, Engelman DM, Sturgis JN. Detergents modulate dimerization, but not helicity, of the glycophorin A transmembrane domain. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:639–651. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Russ WP, Engelman DM. TOXCAT: a measure of transmembrane helix association in a biological membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:863–868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Sulistijo ES, MacKenzie KR. Sequence dependence of BNIP3 transmembrane domain dimerization implicates side-chain hydrogen bonding and a tandem GxxxG motif in specific helix-helix interactions. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:974–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Marchesi VT. An alternative interpretation of the amyloid Abeta hypothesis with regard to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9093–9098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503181102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]