Abstract

Ongoing anthropogenic eutrophication of Jiaozhou Bay offers an opportunity to study the influence of human activity on bacterial communities that drive biogeochemical cycling. Nitrification in coastal waters appears to be a sensitive indicator of environmental change, suggesting that function and structure of the microbial nitrifying community may be associated closely with environmental conditions. In the current study, the amoA gene was used to unravel the relationship between sediment aerobic obligate ammonia-oxidizing Betaproteobacteria (Beta-AOB) and their environment in Jiaozhou Bay. Protein sequences deduced from amoA gene sequences grouped within four distinct clusters in the Nitrosomonas lineage, including a putative new cluster. In addition, AmoA sequences belonging to three newly defined clusters in the Nitrosospira lineage were also identified. Multivariate statistical analyses indicated that the studied Beta-AOB community structures correlated with environmental parameters, of which nitrite-N and sediment sand content had significant impact on the composition, structure, and distribution of the Beta-AOB community. Both amoA clone library and quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses indicated that continental input from the nearby wastewater treatment plants and polluted rivers may have significant impact on the composition and abundance of the sediment Beta-AOB assemblages in Jiaozhou Bay. Our work is the first report of a direct link between a sedimentological parameter and the composition and distribution of the sediment Beta-AOB and indicates the potential for using the Beta-AOB community composition in general and individual isolates or environmental clones in the Nitrosomonas oligotropha lineage in particular as bioindicators and biotracers of pollution or freshwater or wastewater input in coastal environments.

Nitrification, the oxidation of ammonia to nitrate via nitrite, plays a critical role in the biogeochemical cycling of nitrogen and the formation of the large deep-sea nitrate reservoir (37, 46, 51). Because the N cycle may affect the global C cycle, shifts in N transformation processes may also affect the climate (30, 40). Nitrification is an important bioremediation process in human-perturbed estuarine and coastal ecosystems, where it may serve as a detoxification process for excess ammonia (14). If coupled to classical denitrification or anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox), these processes may remove most of the anthropogenic N pollution (51, 81). Bacterial nitrifiers may also cooxidize a variety of xenobiotic compounds (3, 49). On the other hand, nitrification may lead to enhanced production of the potent greenhouse gases nitric oxide (NO) and nitrous oxide (N2O) (15). Because the input of excess ammonia stimulates the growth of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms, research in coastal environments and ecosystems increasingly includes the study of microbial communities involved in nitrification.

Marine nitrification is performed by chemolithoautotrophic proteobacteria and the newly discovered ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) (47); nevertheless, reliable information on the individual contributions of each cohort to the process is still lacking (72) and the contributions likely vary in different environments (33, 51, 93). Beta- and gammaproteobacterial aerobic obligate ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) are known to catalyze the oxidization of ammonia to nitrite, the first and rate-limiting step of nitrification (3). Because of their monophyletic nature, diversity, and important environmental functionality, the betaproteobacterial AOB (Beta-AOB) have served as a model system in the study of fundamental questions in microbial ecology, including microbial community structure, distribution, activity, and environmental response (9, 49, 92).

The growth of AOB is slow, and present isolates represent only a fraction of their natural diversity. Culture-independent molecular methods provide a more convenient and accurate approach for community analyses (76, 92). All AOB genomes contain at least one cluster of amoCAB genes encoding functional ammonia monooxygenase (AMO), which catalyzes the oxidation of ammonia to hydroxylamine (4). Because AmoA- and 16S rRNA-based phylogenies are congruent (73), the amoA gene has been extensively used as a molecular marker to explore and characterize the structure and diversity of AOB communities in a variety of estuarine and coastal environments (9, 10, 11, 13, 27, 32, 36, 43, 68, 88). Some of these studies indicated that local environmental factors such as salinity, pH, ammonium, and O2 concentrations might be drivers for the formation of distinct AOB assemblages, in which individual lineages may have evolved differential ecophysiological adaptivity (4, 73, 85). Furthermore, differences in AmoA sequences may correlate with differences in isotopic discrimination during ammonia oxidation, implicating function-specific ammonia monooxygenases (15). Therefore, the AmoA sequences may provide information about the structure and composition of the AOB communities and their ecological function and response to environmental complexity and variability. Despite long-standing efforts, a complete understanding of these relationships is still lacking (9), especially in complex environments such as anthropogenic activity-impacted coastal areas.

China consumes more than 20 million tons of N fertilizer each year, leading to a significant increase of coastal N pollution (38). Thus, the China coast is an important location for intense N biogeochemical cycling. Jiaozhou Bay is a large semienclosed water body of the temperate Yellow Sea in China. Eutrophication has become its most serious environmental problem, along with red tides, species loss, and contamination with toxic chemicals and harmful microbes (21, 23, 24, 28, 82, 91). In similar environments with a high input of nitrogenous compounds, surface sediment is a major site for nitrification due to a relatively high AOB abundance and activity (79).

Although the China coast is important in N cycling and in related environmental and climatic issues, surprisingly very little is known, especially about the microbial processes and functions involved. On a global scale, it is currently not well understood how the AOB community structure, abundance, and distribution respond to coastal eutrophication, though partial knowledge is emerging (36, 49, 89). Recent studies indicated that spatial distribution and structure of the sediment AOA community could be influenced by a variety of environmental factors, of which continental input may play important roles in estuary and continental margin systems (22, 26). The sediment AOA community may serve as useful biotracers and bioindicators of specific environmental disturbance. Likewise, the sediment AOB community may also serve as biotracers or bioindicators of continental influence, such as eutrophication in coastal environments. In this study, the bacterial functional marker gene amoA was employed to test this hypothesis in the eutrophied Jiaozhou Bay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site description, sample collection, and environmental factor analyses.

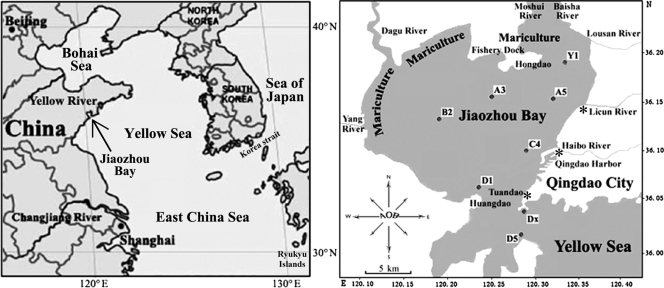

The Jiaozhou Bay environmental conditions have been described previously (21, 23). Limited water exchange and numerous sources of nutrient input from surrounding wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), rivers, and intertidal and neritic mariculture fields have made Jiaozhou Bay hypernutrified (Fig. 1). Three WWTPs, Tuandao, Haibo, and Licun, are located on the eastern shore of Jiaozhou Bay. The Haibo, Licun, and Lousan rivers on the east shore serve as the conduits for industrial and domestic wastewater from the city of Qingdao; the Baisha and Moshui rivers carry mariculture wastewater from the north; and the Dagu and Yang rivers discharge agricultural fertilizer-rich freshwater from the west (94). A state strategic crude oil reserve base with the capability of stockpiling more than 3 million tons of crude oil and a large oil refining project with a designed processing capacity of 10 million tons per year are located in the Huangdao area of the western shore of Jiaozhou Bay (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Maps show the Yellow Sea (left) and the sampling stations of Jiaozhou Bay (right). The locations of wastewater treatment plants are indicated by asterisks. (Maps adapted from references 21, 23, 24, and 91 with kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media.)

Jiaozhou Bay seawater reaches its maximum N2O saturation and atmospheric emission in summer (94), indicating that intense nitrification activity might occur during this time. Therefore, surface sediment samples down to a 5-cm depth were collected from 8 stations (Fig. 1) in the summer of 2006 as described in a previous publication (21), which also detailed the environmental analysis procedures (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Measurements of in situ environmental parameters of the 8 sampling stations in Jiaozhou Bay of 18 July 2006a

| Environmental factor | Station |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3 | A5 | B2 | C4 | D1 | D5 | Dx | Y1 | |

| Longitude (°E) | 120.250 | 120.330 | 120.188 | 120.292 | 120.230 | 120.278 | 120.286 | 120.337 |

| Latitude (°N) | 36.158 | 36.155 | 36.133 | 36.100 | 36.067 | 36.016 | 36.043 | 36.189 |

| Water depth (m) | 6.4 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 7.0 | 16.0 | 38.0 | 9.0 | 5.5 |

| Surface seawater temp (°C) | 21.6 | 21.5 | 22.4 | 21.2 | 21.8 | 20.8 | 21.1 | 21.8 |

| Sediment | ||||||||

| Temp (°C) | 17.6 | 14.6 | 17.7 | 14.4 | 18.5 | 16.4 | 17.5 | 16.9 |

| OrgC (%) | 0.45 | 1.03 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 1.08 |

| OrgN (%) | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| OrgC/OrgN ratio | 11.25 | 12.88 | 9.67 | 11.50 | 14.50 | 12.00 | 11.75 | 10.80 |

| Sand content (%) | 17.15 | 3.00 | 39.04 | 28.50 | 20.68 | 29.22 | 24.45 | 14.34 |

| Silt content (%) | 65.36 | 63.91 | 47.08 | 55.20 | 67.65 | 58.73 | 61.22 | 63.91 |

| Clay content (%) | 17.49 | 33.09 | 13.88 | 16.30 | 11.68 | 12.04 | 14.34 | 21.75 |

| Median grain size (φ)b | 5.27 | 6.81 | 4.52 | 5.00 | 4.80 | 4.65 | 4.82 | 6.04 |

| Sorting coefficient | 1.94 | 1.86 | 2.20 | 2.11 | 1.78 | 1.90 | 1.95 | 1.97 |

| Kurtosis | 2.45 | 2.19 | 2.78 | 2.64 | 2.43 | 2.55 | 2.53 | 2.40 |

| Skewness | 1.77 | 0.81 | 1.96 | 1.82 | 1.85 | 1.91 | 1.88 | 1.45 |

| Sediment pore water | ||||||||

| Salinity (‰) | 26.0 | 27.0 | 26.0 | 30.0 | 27.0 | 26.0 | 28.0 | 26.0 |

| pH | 7.83 | 7.87 | 7.80 | 7.87 | 7.72 | 7.43 | 7.67 | 7.89 |

| DO (μM) | 117.50 | 171.88 | 146.56 | 122.50 | 166.56 | 168.13 | 136.88 | 105.00 |

| NO3−-N (μM) | 12.40 | 32.20 | 11.97 | 12.40 | 3.57 | 3.57 | 8.69 | 1.86 |

| NO2−-N (μM) | 11.70 | 11.85 | 10.67 | 12.90 | 9.46 | 10.86 | 9.55 | 11.97 |

| NH4+-N (μM) | 577.36 | 698.63 | 434.09 | 743.47 | 507.16 | 514.69 | 684.14 | 750.07 |

| DIN (μM)c | 601.46 | 742.68 | 456.73 | 768.77 | 520.19 | 529.12 | 702.38 | 763.90 |

| PO43+-P (μM) | 11.09 | 9.37 | 4.24 | 6.15 | 4.49 | 1.91 | 10.28 | 16.26 |

| N/P (DIN/PO4-P) | 54.23 | 79.26 | 107.72 | 125.00 | 115.86 | 277.03 | 68.32 | 46.98 |

Org, organic; DO, dissolved oxygen; DIN, dissolved inorganic nitrogen.

Median grain size is expressed in φ units, which are the base 2 logarithmic values calculated for given average grain diameters in millimeters.

The total inorganic N concentration (DIN) was calculated as the sum of NH4+-N, NO2−-N, and NO3−-N.

DNA extraction and Beta-AOB amoA gene clone library analyses.

DNA was extracted from sediment samples as reported previously (21, 26). Replicate DNA extractions from three separate subcore samples were pooled for each sampling station. The amoA gene fragments (491 bp) were amplified using published PCR protocols with the Beta-AOB-specific primers amoA-1F* and amoA-2R (87). To test the reproducibility of our experimental procedure and to identify any potential small-scale (∼20-cm) spatial variability of the sediment Beta-AOB community, two separate amoA libraries were constructed for station B2, each for a distinct subcore DNA sample. PCR products from 5 reactions were pooled to minimize PCR bias (36), gel purified, and ligated into pMD19-T Simple vectors (Takara, Tokyo, Japan), which were used to transform competent Escherichia coli TOP10 cells (25, 26). Plasmid insert-positive recombinants were selected using X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside)-IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) LB indicator plates amended with 100 μg/ml ampicillin. A minipreparation method was used to isolate insert-positive plasmids (20), and the vector primers RV-M and M13-D were used to reamplify the cloned DNA fragments (25, 26). Resulting PCR products were screened for correct size and purity by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Amplicons of correct size were digested with MspI and HhaI endonucleases (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD), and restriction fragments were resolved by electrophoresis on 4% agarose gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer. Band patterns digitally photographed with an ImageMaster VDS imaging system (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) were compared for restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) to identify redundant clones.

Primers RV-M and M13-D were used for sequencing the plasmid inserts by using an ABI 3770 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The BLAST program and deduced protein sequences as queries were used for retrieval of the most similar protein sequences from GenBank (2). AmoA sequences were grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) based on uniqueness using the DOTUR program (80). Phylogenetic analyses followed previously established procedures (21, 26).

Quantification of the sediment 16S rRNA and amoA genes.

Plasmids constructed previously (25) or in this study carrying a 16S rRNA or Beta-AOB amoA gene fragment were extracted from E. coli hosts using a miniplasmid kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Concentrations of environmental genomic DNA and plasmid DNA were measured using PicoGreen (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and a Modulus single-tube multimode reader fluorometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA). DNA concentrations were adjusted to 20 ng/μl for real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays.

All qPCR assays targeting 16S rRNA or amoA genes were carried out in triplicate with an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the SYBR green qPCR method (71). The 25-μl qPCR mixture contained the following: 12.5 μl of 2× SYBR green Premix II (TaKaRa), 0.5 μM final concentration of each primer, 0.8 μg/μl bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 μl ROX Reference Dye II, and 1.0 μl template DNA (corresponding to 20 ng of environmental genomic DNA). All reactions were performed in 8-strip thin-well PCR tubes with ultraclear cap strips (ABgene, Epsom, United Kingdom). Agarose gel electrophoresis and melting curve analysis were routinely employed to confirm specificity of the qPCRs. Standard curves were obtained with serial dilution of the quantified standard plasmids carrying the target 16S rRNA or amoA gene. In all experiments, negative controls containing no template DNA were subjected to the same qPCR procedure to detect and exclude any possible contamination or carryover.

Sediment total bacterial 16S rRNA genes were quantified using primers 341F and 518R (83). To increase specificity, 50 mM KCl (final concentration) was added to the qPCR mixture. The qPCR thermocycling parameters were as follows: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 5 s, primer annealing at 60°C for 20 s, and elongation at 72°C for 45 s. Melting curves were obtained at 60°C to 95°C with a read every 1°C held for 1 s between reads. The copy number of the standard plasmids carrying 16S rRNA genes ranged from 1.02 × 106 to 1.02 × 1012.

Sediment total Beta-AOB amoA genes were quantified using primers amoA-1F* and amoA-2R (87, 90). The qPCR thermocycling parameters were the same as those for qPCR of the 16S rRNA genes. The copy number of the standard plasmids carrying Beta-AOB amoA genes ranged from 9.03 × 103 to 9.03 × 109. Sediment amoA genes of Nitrosomonas were quantified using primers P128r (5′-GGTGGTGGWTTCTGGGG-3′) and P365r (5′-CCACCATACRCARAACATCA-3′) designed with the amoA sequences obtained in this study. The qPCR parameters were modified slightly from the above conditions of the total Beta-AOB amoA gene quantification: primer annealing was at 58°C for 20 s. The copy numbers of the standard plasmids carrying the amoA gene of Nitrosomonas ranged from 9.03 × 103 to 9.03 × 109.

Data were analyzed with the second-derivative maximum method using the ABI PRISM 7500 SDS software (version 1.4; Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analyses.

Environmental classification was performed via hierarchical clustering with the Minitab statistical software (release 13.32; Minitab Inc.) using normalized environmental data (i.e., adjusted to 0 mean and 1 standard deviation [SD] via Z transformation) (60). The library coverage was calculated as C = [1 − (n1/N)] × 100, where n1 is the number of unique OTUs and N is the total number of clones in a library (64). Indices of diversity (Shannon-Weiner H and Simpson D) and evenness (J) were calculated for each library. Rarefaction analysis and two nonparametric richness estimators, the abundance-based coverage estimator (SACE) and the bias-corrected Chao1 (SChao1), were calculated using DOTUR (80). These diversity indices and richness estimators were then used to compare the relative complexities of communities and to estimate the completeness of sampling.

Community classification of the Beta-AOB assemblages was analyzed using the Jackknife environment clustering and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) methods of the UniFrac program (56). Correlations of the Beta-AOB assemblages with environmental factors were explored with canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) using the software Canoco (version 4.5; Microcomputer Power) as reported recently (21, 22, 26).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Determined partial amoA gene sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers EU244490 to EU244561.

RESULTS

Jiaozhou Bay environmental conditions.

Hypernutrification is one of the most notorious environmental problems of Jiaozhou Bay. This situation is aggravated by limited water exchange with the adjacent Yellow Sea, especially at the most distant stations, A3, A5, and Y1 (Fig. 1). High concentrations of dissolved inorganic nitrogen, especially NH4+-N, were evident at all the stations (Table 1). The N/P ratios (from 47:1 to 277:1) significantly exceeded the Redfield stoichiometry (16:1), indicating that unbalanced nutrient overloading might have disturbed the normal marine ecosystem structure and function.

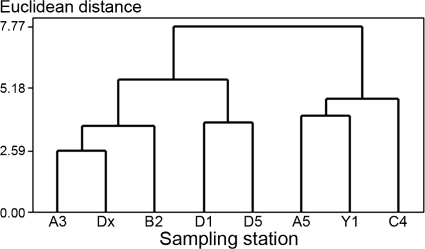

Multivariate clustering of Jiaozhou Bay physicochemical factors (Table 1) identified two types of environmental conditions: stations A5, C4, and Y1 of the eastern area established type 1, and the remaining stations belonged to type 2 (Fig. 2). This classification was consistent with previous studies (21, 23, 24, 28, 53) that identified the eastern part of the bay as the most hypernutrified and polluted area, which correlates with river runoffs and WWTP discharges from the nearby city of Qingdao (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

The environment hierarchical clustering dendrogram constructed using Euclidean distance and Ward linkage of the Jiaozhou Bay sediment physicochemical factors, including NO3−-N, NO2−-N, NH4+-N, dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN), PO43−-P, N/P, organic carbon (OrgC), OrgN, OrgC OrgN, water depth, and pore water salinity. Due to the shallow depths of most of the stations and the possible diel variation of seawater temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and pH during our sampling period, the above 3 parameters were not included in the analysis.

Diversity of the Beta-AOB amoA gene assemblages.

The two amoA clone libraries constructed from separate sediment samples obtained at station B2 had similar RFLP sequence types and relative abundances (data not shown), demonstrating the reproducibility of our DNA extraction, PCR, and cloning procedures and the negligible within-site variability of the sediment Beta-AOB community in Jiaozhou Bay. This is consistent with results obtained from the Ythan estuary, which indicated that within-site replicate sediment samples had almost identical Beta-AOB compositions and community structures (36). The observed local homogeneity of sediment microbial communities is likely caused by ongoing sieving and sorting of the sediments by the overlying seawater through tides, currents, and other hydrological actions. Because of the consistency of our results and prior results (36), the two libraries were pooled as a single B2 amoA library for simplicity. A total of 730 clones were screened from the eight constructed amoA clone libraries (one per station), and 71 unique RFLP sequence types were identified. The calculated coverage values indicated that more than 90% of the AmoA diversity was captured in all the libraries (Table 2). This was further confirmed by rarefaction analysis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We had probably captured the majority of AmoA sequences from the resident sediment Beta-AOB. While similar AmoA sequence diversity was found for most of the sampling stations, AmoA sequences from stations A3 and Dx stood out as being least diverse as indicated by the majority of the measured indices (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Biodiversity and predicted richness of the sedimentary bacterial AmoA sequences recovered from the sampling stations in Jiaozhou Bay

| Station | No. of clones | No. of unique amoA sequencesa | No. of OTUsb | C (%) | H | 1/D | J | SACE | SChao1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3 | 93 | 18 | 13 | 95.70 | 2.791 | 4.575 | 0.754 | 15.97 | 16.00 |

| A5 | 88 | 27 | 20 | 89.77 | 3.532 | 9.007 | 0.817 | 32.85 | 29.00 |

| B2 | 121 | 21 | 19 | 94.21 | 3.467 | 9.041 | 0.816 | 31.80 | 24.25 |

| C4 | 86 | 23 | 19 | 90.70 | 3.496 | 8.936 | 0.823 | 27.16 | 28.33 |

| D1 | 84 | 27 | 21 | 90.48 | 3.636 | 9.792 | 0.828 | 32.50 | 24.50 |

| D5 | 88 | 18 | 16 | 95.45 | 3.603 | 11.495 | 0.901 | 18.24 | 19.00 |

| Dx | 80 | 12 | 11 | 97.50 | 2.744 | 5.777 | 0.793 | 12.27 | 11.2 |

| Y1 | 90 | 21 | 15 | 94.44 | 3.167 | 6.544 | 0.811 | 18.90 | 25.00 |

Unique amoA sequences were determined via RFLP analysis.

Unique OTUs of the AmoA sequences were determined using the DOTUR program. The coverage (C), Shannon-Weiner (H), Simpson (D), and evenness (J) indices and SACE and SChao1 richness estimators were calculated with the OTU data.

Molecular diversity of the Beta-AOB AmoA sequences.

The 71 distinct amoA phylotypes identified via RFLP analysis shared 72.3 to 99.8% sequence identity among each other and were 81.3 to 100.0% identical to the corresponding top hit amoA sequences deposited in GenBank (as of May 2009). The deduced AmoA protein sequences were 82.2 to 100.0% identical among each other and 90.2 to 100.0% identical to the top hit protein sequences in GenBank deduced from amoA genes that originated from samples in a variety of environments, including lake, riverine, estuarine, coastal, coral reef, and deep-sea sediments; marine aquaculture biofilms; soils; activated sludges; and biofilm reactors (10, 31, 41, 45, 74, 95). The Jiaozhou Bay AmoA sequences were grouped into 43 unique OTUs, most of which did not match closely with sequences from any known AOB isolate. Nearly half of the OTUs as well as 61.0% of the clones had their closest matches with sequences originally retrieved from sedimentary environments of the American Plum Island Sound estuarine system (10). The high similarity of the Beta-AOB AmoA sequences of these two coastal sites suggested that the two sites were likely also similar regarding certain environmental characteristics.

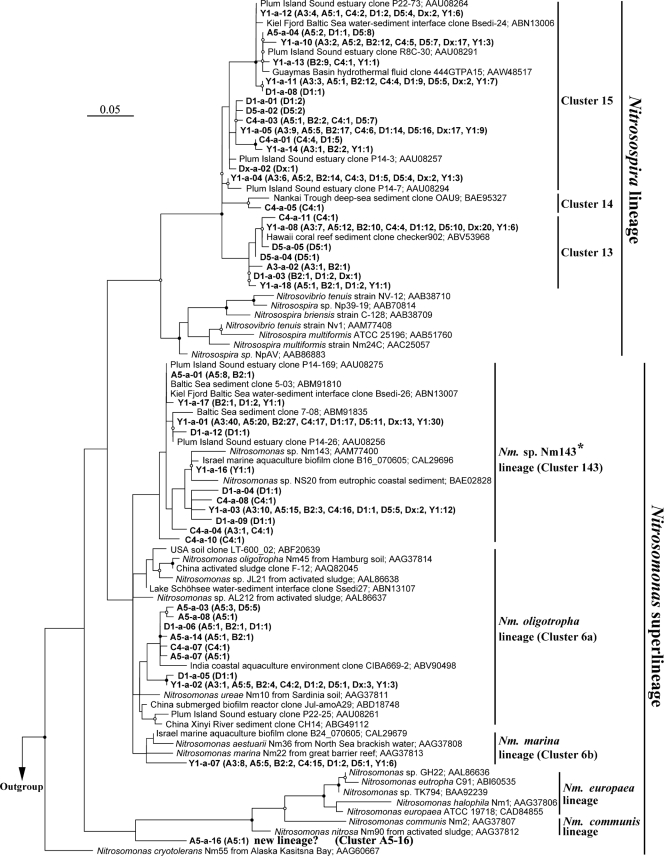

Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the AmoA sequences grouped with known sequences from AOB in the Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira genera (Fig. 3 ). Except for OTU A5-a-16, all the Jiaozhou Bay Nitrosomonas-related sequences grouped with sequences in the lineages of Nitrosomonas sp. Nm143 (cluster 143; 11 OTUs and 260 clones), Nitrosomonas oligotropha (cluster 6a; 8 OTUs and 38 clones), and Nitrosomonas marina (cluster 6b; 1 OTU and 39 clones) (73). Sequence A5-a-16 (tentatively named cluster A5-16; 1 OTU and 1 clone) grouped at the base and thus outside the clade including the N. europaea and N. communis lineages at an evolutionary distance similar to the also sparsely populated N. cryotolerans lineage.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree constructed with distance and neighbor-joining method from an alignment of the 43 Jiaozhou Bay AmoA sequences, along with their closest matches retrieved from GenBank. Tree branch lengths represent amino acid substitution rates, and the scale bar indicates the expected number of substitutions per homologous position. Several AmoA sequences from gammaproteobacterial AOB and PmoA (particulate methane monooxygenase subunit A) sequences from alphaproteobacteria and gammaproteobacteria were used as outgroup (not shown for clarity of the Beta-AOB AmoA sequences). Bootstrap values higher than 70% of 100 resamplings in support of the presented tree are shown with solid circles on the corresponding nodes, and those less than 70% but greater or equal to 50% are shown with open circles on the corresponding nodes. Nm, Nitrosomonas.

The Jiaozhou Bay Nitrosospira-related OTUs were not affiliated within any AmoA sequence cluster defined by cultured AOB (5). However, similar sequences have been retrieved before from diverse estuarine, coastal, and deep-sea environments, especially from sediments (10, 41, 45). Phylogenetic analyses indicated that these OTUs could be grouped into three new clusters based on the nomenclature of Avrahami and Conrad (5), and they were tentatively named clusters 13, 14, and 15 (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Clusters 13 and 14 comprised environmental AmoA sequences from coastal and deep-sea marine sediment environments (41), whereas cluster 15 comprised AmoA sequences mainly from estuarine and coastal sediment environments (10, 45). Based on the nomenclature of Francis et al. (32), cluster 15 was also named “Nitrosospira-like cluster B” in a recent study (45).

Ten of the 43 Jiaozhou Bay AmoA OTUs were very common, including 7 OTUs occurring at all the sampling stations and three at 7 stations. Of these 10 omnipresent OTUs, two were affiliated within the Nitrosomonas sp. Nm143 lineage, one within the Nitrosomonas oligotropha lineage, one within the Nitrosomonas marina lineage, one within the Nitrosospira cluster 13 lineage, and five within the Nitrosospira cluster 15 lineage (Fig. 3). Although these OTUs represented only 23.3% of all the OTUs identified, they accounted for 85.5% of all the clones recovered. These OTUs likely represent the most common and dominant sediment Beta-AOB in Jiaozhou Bay.

Community analyses of the Beta-AOB assemblages.

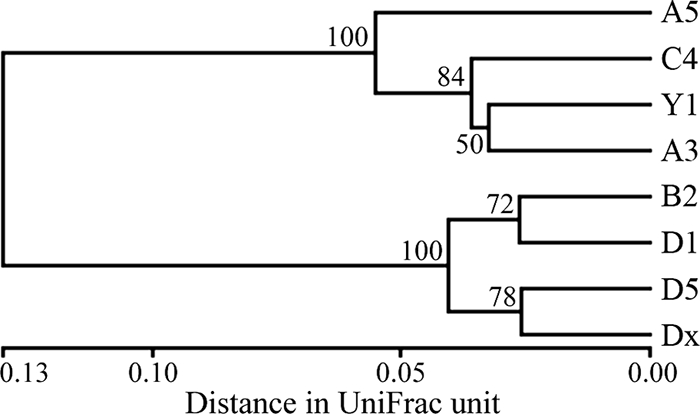

UniFrac environment clustering of the AmoA sequences clearly distinguished two groups of the sediment Beta-AOB assemblages in Jiaozhou Bay (Fig. 4). The assemblages of stations A3, A5, C4, and Y1 in the eastern and northern areas constituted class 1, whereas those of stations B2, D1, D5, and Dx in the western and bay mouth areas constituted class 2. UniFrac PCoA analysis revealed a similar result. The first principal coordinate (P1), which explained 90.16% of the total community variability, unambiguously distinguished the AmoA assemblages of class 1 from those of class 2 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The classification of the Beta-AOB assemblages correlated with the classification of the Jiaozhou Bay environments (Fig. 2), with the only exception being station A3. An all-environment UniFrac significance test indicated a significant difference (P = 0.002) among the Jiaozhou Bay AmoA assemblages. A pairwise UniFrac significance test indicated that the AmoA assemblage of station A5 was marginally significantly different (P ≤ 0.028) from those of stations B2, D5, and Dx and suggested (P = 0.056) a different community composition trend than that for station D1. This heterogeneous distribution of the sediment Beta-AOB assemblages in Jiaozhou Bay may reflect specific microbe-environment interactions.

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram of the hierarchical clustering analysis of the Jiaozhou Bay sedimentary AmoA genotype assemblages using the UniFrac normalized and weighted jackknife environment cluster statistical method. The percentage supports of the classification tested with sequence jackknifing resamplings are shown near the corresponding nodes.

Spatial distribution of the Beta-AOB assemblages.

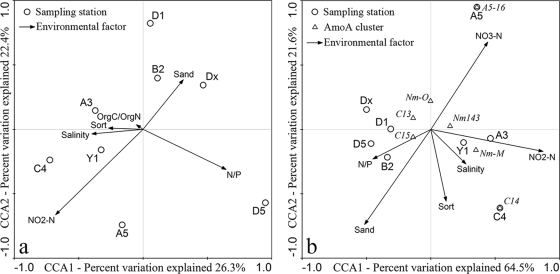

Correlations of the AmoA assemblages with environmental parameters were analyzed via CCA (Fig. 5a). The environmental variables in the first two CCA dimensions (CCA1 and CCA2) explained 46.9% of the total variance in the AmoA composition and 48.7% of the cumulative variance of the AmoA-environment relationship. CCA1 clearly distinguished the AmoA assemblages of class 1 from those of class 2, consistent with the UniFrac community classification results (Fig. 4; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Only the environmental parameter NO2−-N contributed significantly (P = 0.028, 1,000 Monte Carlo permutations) to the AmoA sequence-environment relationship, and this factor alone provided 22.5% of the total CCA explanatory power. Although the contribution of all other environmental factors was not statistically significant (P > 0.150), the combination of these variables provided additionally 73.0% of the total CCA explanatory power.

FIG. 5.

CCA ordination plots for the first two principal dimensions of the relationship between the distribution of AmoA OTUs (a) or clusters (b) and the sediment and pore water environmental parameters in Jiaozhou Bay. Correlations between environmental variables and CCA axes are represented by the length and angle of arrows (environmental factor vectors). Due to the possible diel variation of seawater temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and pH during our sampling period, these parameters were not included in the analyses. Covarying variables, such as NH4+ and dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) (r = 0.9969) and organic carbon (OrgC) and OrgN (r = 0.9826), were checked to minimize collinearity in the CCA analyses. Abbreviations: Nm143, cluster 143; Nm-O, cluster 6a; Nm-M, cluster 6b; C13, cluster 13; C14, cluster 14; C15, cluster 15.

Correlation of the major AmoA clusters with environmental variables was also analyzed (Fig. 5b). The first two CCA axes (CCA1 and CCA2) explained 84.7% of the total variance in AmoA cluster composition and 86.1% of the cumulative variance of the AmoA cluster-environment relationship. CCA1 also clearly distinguished the AmoA assemblages of class 1 from those of class 2. Both NO2−-N (P = 0.001) and sediment sand content (P = 0.028) contributed significantly to the AmoA cluster-environment relationship, and they provided 69.6% of the total CCA explanatory power.

Quantification analyses of the Beta-AOB assemblages.

The fluorescence reading for Beta-AOB amoA qPCR was carried out at 83°C (above the melting point of possible primer dimers) to avoid detection of nonspecific PCR products (12). Melting curve analyses confirmed that the fluorescent signals were obtained from specific qPCR products for the 16S rRNA and amoA gene quantifications.

Standard curves generated using plasmids containing cloned 16S rRNA or amoA gene fragments to relate threshold cycle (CT) to gene copy number revealed linearity (R2 ≥ 0.98) over 7 orders of magnitude of the plasmid DNA concentration. The obtained high correlation coefficients and similar slopes of the linear regression of experimental and standard curves indicated high primer hybridization and extension efficiencies (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), making comparison of the different genes reasonable (55). Absence or undetectable influence of sediment PCR-inhibitory substances was confirmed by obtaining similar amplification efficiencies with 10-fold-diluted environmental genomic DNAs extracted from the sediments of station A5 (data not shown).

The qPCR results showed a heterogeneous distribution of the sediment bacterial 16S rRNA gene abundance among the sampling sites of Jiaozhou Bay, where station Y1 had the highest gene copy number (2.76 × 1011 copies g sediment−1) and station D1 had the lowest gene copy number (1.43 × 1010 copies g sediment−1) (Table 3). The copy numbers of the sediment Beta-AOB amoA genes also showed a distributional heterogeneity in Jiaozhou Bay, in that the eastern and northern areas (stations A3, A5, C4, and Y1) had a higher amoA gene abundance than did the western and bay mouth areas (stations B2, D1, D5, and Dx) (Table 3). A similar distribution pattern was also found for the sediment Nitrosomonas amoA gene abundance (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Copy numbers of the total bacterial 16S rRNA, Beta-AOB amoA, and Nitrosomonas amoA genes in sediment samples of the eight stations in Jiaozhou Bay determined by real-time fluorescent PCR

| Sampling station | Target gene copy no. g sediment−1 (SE) |

Ratio (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | Beta-AOB amoA | Nitrosomonas amoA | Beta-AOB amoA/16S rRNA | Nitrosomonas amoA/Beta-AOB amoA | |

| A3 | 1.36 × 1011 (2.50 × 1010) | 3.04 × 107 (2.94 × 106) | 3.66 × 106 (4.39 × 105) | 0.022 | 12.04 |

| A5 | 1.02 × 1011 (1.30 × 1010) | 7.77 × 107 (8.13 × 106) | 3.72 × 107 (1.08 × 106) | 0.076 | 47.88 |

| B2 | 4.19 × 1010 (1.69 × 109) | 6.70 × 106 (2.39 × 105) | 2.70 × 105 (4.62 × 104) | 0.016 | 4.03 |

| C4 | 1.01 × 1011 (1.34 × 1010) | 6.51 × 107 (1.06 × 106) | 2.39 × 107 (5.44 × 106) | 0.064 | 36.71 |

| D1 | 1.43 × 1010 (2.04 × 109) | 3.09 × 106 (1.58 × 105) | 1.92 × 105 (7.43 × 104) | 0.022 | 6.21 |

| D5 | 5.84 × 1010 (1.52 × 109) | 4.35 × 106 (5.92 × 105) | 1.47 × 105 (3.92 × 104) | 0.007 | 3.38 |

| Dx | 2.00 × 1011 (5.35 × 1010) | 6.16 × 106 (8.96 × 105) | 1.27 × 105 (1.89 × 104) | 0.003 | 2.06 |

| Y1 | 2.76 × 1011 (2.55 × 1010) | 8.01 × 107 (4.70 × 106) | 2.87 × 107 (1.11 × 106) | 0.029 | 35.83 |

The relative abundance of the sediment Beta-AOB amoA gene copies compared to that of the sediment total bacterial 16S rRNA gene copies also showed a heterogeneous distribution among the eight sites of Jiaozhou Bay, where station Dx had the lowest ratio (0.003%) and station A5 had the highest ratio (0.076%) (Table 3). The ratio of sediment amoA gene copies between Nitrosomonas and total Beta-AOB showed that Nitrosomonas contributed considerably more to the total abundance of sediment Beta-AOB in the eastern areas (stations A5, C4, and Y1; 40% ± 7%) than in the western and bay mouth areas (stations B2, D1, D5, and Dx; 4% ± 2%), with station A3 (12%) in the northern area of Jiaozhou Bay being intermediate (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Beta-AOB genotypic diversity in coastal environment.

The oxic sediment layers in all Jiaozhou Bay sampling stations were located only in the top few millimeters to centimeters of the sediments, indicating a sedimentary status of high organic matter input and strong microbial respiration in the bulk sediments. This thin oxic surface layer at or immediately above the oxic-suboxic transition zone was shown previously to harbor the maximum nitrification activity in coastal sediments (8). Our study identified the presence of a set of diverse but defined Jiaozhou Bay-specific betaproteobacterial amoA genes whose sequences grouped in 7 clusters and potentially reflect distinct ecophysiologies of the respective resident Beta-AOB.

The Jiaozhou Bay-specific OTU A5-a-16 was identified as being most closely related to the Nitrosomonas europaea and N. communis lineages (Fig. 3) containing AOB that apparently thrive in heavy metal-polluted and high-NH4+-N environments (reference 85 and references therein), a finding which correlates with the location of its isolation (station A5), characterized by high efflux from the Licun River and the Licun WWTP (Fig. 1). High concentrations of sediment heavy metals (28) and pore water NH4+-N (Table 2) have been identified in this area. The phylogram suggests that OTU A5-a-16 and the clade containing the N. europaea and N. communis lineages are “sister clades,” and A5-a-16 did not group with N. cryotolerans. Thus, OTU A5-a-16 may represent a novel lineage. The finding of A5-a-16 and other unevenly distributed Jiaozhou Bay-specific OTUs allows the conclusion that intrinsically dynamic environmental conditions and processes, complicated further with anthropogenic perturbations, may have created unique niches in Jiaozhou Bay, promoting the emergence or selection of novel bacterial lineages not found in other environments of the world.

All three newly defined Nitrosospira lineage-related AmoA clusters contained only environmental sequences (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and these sequences and clusters may represent novel AOB species and lineages, respectively. Our CCA analysis might provide a clue for understanding or probing their ecophysiology. The cluster 14 sequences were related to a niche of high salinity. Their distribution was also positively correlated with the sediment sorting coefficient and NO2−-N (Fig. 5b). The AOB represented by cluster 13 and 15 sequences might share similar niches, but significant correlation with any of the measured environmental factors was not observed (Fig. 5b). The AOB in both clusters might have wide distribution in coastal environments, as was shown for the Nitrosomonas sp. Nm143 lineage (36). Of all the environmental factors presented in the CCA model, the distribution of OTU A5-a-16 was positively correlated only with NO3−-N and NO2−-N (Fig. 5b), suggesting that Beta-AOB in this lineage might participate in the in situ sediment nitrification.

Beta-AOB as potential bioindicators and biotracers of pollution.

Changes in AOB composition and community structure might be used as a potential bioindicator of environmental disturbance (49). With the increase in salinity, Beta-AOB diversity was found to change (usually to decrease) in selected estuaries of the world (9, 10, 16, 27, 32, 88, 93), indicating that freshwater might harbor AOB assemblages distinct from those of marine systems (11, 19, 39). Estuaries may represent a transition zone with a mixture of autochthonous and allochthonous microbes from both end components of the aquatic ecosystem. Our CCA analyses indicated that the Jiaozhou Bay sedimentary environments spanned a variety of eutrophication statuses, potentially selecting distinct Beta-AOB assemblages along the various combinations of environmental gradients (Fig. 5).

The relative abundances of Nitrosomonas- and Nitrosospira-related amoA gene clones were different between the class 1 and class 2 Beta-AOB assemblages in Jiaozhou Bay. The percentage of the Nitrosomonas-related clones in the four libraries of the class 1 stations (64% ± 4%) was significantly higher than that of the four class 2 stations (29% ± 6%) (Student's t test, P < 0.001, df = 6), whereas the percentage of the Nitrosospira-related clones showed the opposite trend. This was further confirmed by qPCR quantification of the amoA gene abundance (Table 3). Comparison of the in situ amoA gene abundances of Nitrosomonas and total AOB (Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira) determined by qPCR showed that the percentage of the Nitrosomonas amoA gene copies in the sediments of the four class 1 stations (33% ± 15%) was significantly higher than that of the four class 2 stations (4% ± 2%) (Student's t test, P = 0.004, df = 6). It has been proposed that the decrease of Nitrosomonas AOB and the increase of Nitrosospira AOB might be correlated with the increase in salinity of estuarine and coastal environments (36); however, a significant difference of the average sediment pore water salinities between the stations of the two classes (27‰ ± 2‰ versus 27‰ ± 1‰) was not found in Jiaozhou Bay (Student's t test, P = 0.673, df = 6). Further, the microbe-environment CCA analyses indicated that salinity contributed only little to the distribution and classification of the sediment AmoA sequence assemblages (Fig. 5). Other studies also indicated that salinity may not be the primary factor determining the Beta-AOB population distribution (9). Freshwater input from the surrounding small rivers and WWTPs did not significantly change the water salinity of Jiaozhou Bay (Table 1). Long-term surveys also indicated that the overall bay water salinity was quite high (∼30‰) and stable (23, 53, 54, 82, 94). Jiaozhou Bay is thus a marine-water-dominant environment. The shift in the sediment Beta-AOB community composition was probably caused by exogenous input of microbes and nutrients, via localized rivers and WWTPs.

The Nitrosomonas oligotropha lineage forms a major component of the ammonia-oxidizing communities in freshwater environments (48, 49, 84), particularly in wastewaters and activated sludges, biofilm reactors, biofilters, or other N removal applications (17, 52, 57, 73). Although bacterial isolates or gene clones of this lineage were also detected in estuarine or coastal bay environments, most of them were actually found in the freshwater or the low-salinity end of ecosystems (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) (10, 11, 16, 17, 27, 32, 58, 65, 69, 79, 84). Hence, factors contributing to the survival of N. oligotropha lineage AOB in relatively high-salinity coastal environments needed to be identified (Table S2). We propose that freshwater flushing during low tides might provide the survival conditions for these bacteria in intertidal sediments (66). Strong seasonal freshwater input, making the estuarine environment resemble a freshwater environment in certain periods of the year, might also explain the source and preservation of N. oligotropha lineage AOB in sediments during high-salt seasons (13). Association with biofilms or benthic infaunal burrow walls might also provide the mechanism for survival or preservation of these bacteria in highly dynamic estuarine environments where tidal or seasonal salinity fluctuation occurs (59, 79). Effluent discharges from WWTPs were found to be the direct source of certain environmental N. oligotropha lineage AOB in Tokyo Bay (88) and in other geographical locations (16, 17, 27, 65). Salinity usually has some adverse or inhibitory effects on estuarine sediment nitrification (9, 77), probably due to the low salt tolerance of some of the nitrifiers, particularly the N. oligotropha lineage (84). This was further supported by a stable isotope-probing study, which indicated that AOB in the N. oligotropha lineage found in the brackish and marine sites of the Ythan estuary were probably dormant in situ (36). These findings demonstrated that passive transport via river runoff or wastewater discharge could be the predominant source of the allochthonous freshwater AOB in brackish and marine environments. In true marine and many marine-water-dominant coastal environments, AOB in the N. oligotropha lineage were not detected (6, 7, 34, 35, 41-43, 50, 61, 62, 68, 70, 75, 86). The dormancy of certain freshwater AOB in the coastal environment may thus help in tracking down the source of their allochthonous input (16, 17, 88). As AOB in the N. oligotropha lineage are usually associated with WWTP effluents or rivers, environmental N. oligotropha clones and isolates might potentially serve as bioindicators and biotracers of pollution or river or wastewater input in coastal environments.

Microbe-environment interaction and the role of sedimentological factors.

Although the physicochemical classification indicated that the A3 station was more similar to the less eutrophic stations (Fig. 2), the classification based on sedimentological parameters indicated that it was clustered most closely with the east shore station Y1 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), similar to the results of the AmoA community analysis (Fig. 4 and 5; also Fig. S3). Our qPCR quantifications of the sediment 16S rRNA and amoA genes also indicated that station A3 was similar to the more eutrophic class 1 stations or it was intermediate between the class 1 and class 2 stations (Table 3). The fine-grained-sediment-dominant condition and low oxygen saturation indicated that station A3 might have the potential to receive and accumulate large amounts of organic-rich suspended particulate matter from overlying water. Being far away from the bay mouth might hinder water exchange and hence reduce environmental self-cleansing at this station. Hence, the inclusion of A3 in class 1 of AmoA assemblages suggests that the prevailing sedimentological condition might play an important role in structuring the sediment Beta-AOB community. This was further supported by the community-environment CCA analysis (Fig. 5b), which showed that the gradient of some of the sedimentological factors, such as sediment sand content, correlated significantly with the spatial distribution and classification of the Jiaozhou Bay sediment Beta-AOB assemblages. Sedimentological conditions were mainly related to the in situ hydrological regimen, such as currents, tides, waves, upwelling, lateral transport, water mixing, and the intensity and dynamics of these activities. The correlation of the sediment sand content with Beta-AOB assemblages could be related directly or indirectly to hydrological activities, via their impact on the sediment source, composition, organic matter content, pore water redox, nutrient composition and concentration, and other physicochemical, sedimentological, or geochemical factors. The exact mechanism needs to be determined in future studies.

Although Beta-AOB might comprise only a small fraction (<0.08%) of the total bacteria in the surface sediments of Jiaozhou Bay, their absolute abundances were in the normal range of a variety of coastal environments, from the pristine or less eutrophied coastal sites (9, 29, 63, 78, 79) to the more eutrophied coastal sites, such as Tokyo Bay (88, 89). The relatively lower contribution of Beta-AOB to the total sediment bacterial community in Jiaozhou Bay may have several explanations: (i) growth stimulation of heterotrophic aerobic respiratory microbes by organic pollution might lower the relative abundance of Beta-AOB and also the oxygen availability and thus the absolute abundance of Beta-AOB; (ii) variable 16S rRNA gene copies (up to 15) in bacterial genomes (1) may also lower the apparent proportion of environmental Beta-AOB, which usually have only two to three nearly identical amoA gene copies in their genomes (4, 18, 67, 85); and (iii) potentially present ammonia-oxidizing archaea and anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria may compete effectively with Beta-AOB for ammonia, thereby lowering abundance and thus the relative contribution of Beta-AOB to nitrification at some of the locations (33). The correlation of the sediment Beta-AOB assemblages with NO2−-N (Fig. 5) indicates that Beta-AOB may contribute to active nitrification differently at different sites and different eutrophic statuses of Jiaozhou Bay. Future studies will focus on the sediment nitrification rate and its relation to the Beta-AOB community composition, structure, and abundance and their response to the various environmental gradients and eutrophication in Jiaozhou Bay.

While it has been reported recently that sedimentological parameters may have a significant influence on the bacterial and archaeal nitrogen cycling community structures (21, 26, 44) and niche differentiation between sandy and muddy marine environments was implied in a previous study (43), this work appears to be the first report of a direct link between a sedimentological parameter and the composition and distribution of the sediment Beta-AOB community. Both amoA clone library and qPCR analyses indicated that continental inputs from nearby WWTPs and polluted rivers might have significantly changed the composition and abundance of the sediment AOB assemblages. Our work also indicates the potential application of the Beta-AOB community composition in general and individual isolates or environmental clones in the Nitrosomonas oligotropha lineage in particular as bioindicators and biotracers of pollution or freshwater or wastewater input in a coastal environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chunyan Wang, Yi Jin, Wenliang Ma, and Wei Fan for their assistance in the project.

This work was supported by China National Natural Science Foundation grant 40576069, Hi-Tech Research and Development Program of China grant 2007AA091903, China Ocean Mineral Resources R&D Association grants DYXM-115-02-2-20 and DYXM-115-02-2-6, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China grant 09CX05005A, and an MEL Advanced Visiting Scholarship from the State Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Sciences, Xiamen University. M.G.K. was funded by incentive funds provided by the University of Louisville-EVPR office and the U.S. National Science Foundation (EF-0412129).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 May 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acinas, S. G., L. A. Marcelino, V. Klepac-Ceraj, and M. F. Polz. 2004. Divergence and redundancy of 16S rRNA sequences in genomes with multiple rrn operons. J. Bacteriol. 186:2629-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arp, D. J., and L. Y. Stein. 2003. Metabolism of inorganic N compounds by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38:471-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arp, D. J., P. S. Chain, and M. G. Klotz. 2007. The impact of genome analyses on our understanding of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:503-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avrahami, S., and R. Conrad. 2003. Patterns of community change among ammonia oxidizers in meadow soils upon long-term incubation at different temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6152-6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bano, N., and J. T. Hollibaugh. 2000. Diversity and distribution of DNA sequences with affinity to ammonia-oxidizing bacteria of the β subdivision of the class Proteobacteria in the Arctic Ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1960-1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beman, J. M., and C. A. Francis. 2006. Diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in the sediments of a hypernutrified subtropical estuary: Bahía del Tóbari, Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:7767-7777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg, P., N. Risgaard-Petersen, and S. Rysgaard. 1998. Interpretation of measured concentration profiles in sediment pore water. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43:1500-1510. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernhard, A. E., J. Tucker, A. E. Giblin, and D. A. Stahl. 2007. Functionally distinct communities of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria along an estuarine salinity gradient. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1439-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernhard, A. E., T. Donn, A. Giblin, and D. A. Stahl. 2005. Loss of diversity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria correlates with increasing salinity in an estuary system. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1289-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bollmann, A., and H. J. Laanbroek. 2002. Influence of oxygen partial pressure and salinity on the community composition of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in the Schelde Estuary. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 28:239-247. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caffrey, J. M., N. Bano, K. Kalanetra, and J. T. Hollibaugh. 2007. Ammonia oxidation and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea from estuaries with differing histories of hypoxia. ISME J. 1:660-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caffrey, J. M., N. Harrington, I. Solem, and B. B. Ward. 2003. Biogeochemical processes in a small California estuary. 2. Nitrification activity, community structure and role in nitrogen budgets. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 248:27-40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camargo, J. A., and A. Alonso. 2006. Ecological and toxicological effects of inorganic nitrogen pollution in aquatic ecosystems: a global assessment. Environ. Int. 32:831-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casciotti, K. L., D. M. Sigman, and B. B. Ward. 2003. Linking diversity and stable isotope fractionation in ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Geomicrobiol. J. 20:335-353. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cébron, A., M. Coci, J. Garnier, and H. J. Laanbroek. 2004. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoretic analysis of ammonia-oxidizing bacterial community structure in the lower Seine River: impact of Paris wastewater effluents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6726-6737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cébron, A., T. Berthe, and J. Garnier. 2003. Nitrification and nitrifying bacteria in the lower Seine River and estuary (France). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7091-7100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chain, P., J. Lamerdin, F. Larimer, W. Regala, V. Lao, M. Land, L. Hauser, A. Hooper, M. Klotz, J. Norton, L. Sayavedra-Soto, D. Arciero, N. Hommes, M. Whittaker, and D. Arp. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium and obligate chemolithoautotroph Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Bacteriol. 185:2759-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coci, M., D. Riechmann, P. L. Bodelier, S. Stefani, G. Zwart, and H. J. Laanbroek. 2005. Effect of salinity on temporal and spatial dynamics of ammonia-oxidising bacteria from intertidal freshwater sediment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 53:359-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dang, H. Y., and C. R. Lovell. 2000. Bacterial primary colonization and early succession on surfaces in marine waters as determined by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dang, H. Y., C. Y. Wang, J. Li, T. G. Li, F. Tian, W. Jin, Y. S. Ding, and Z. N. Zhang. 2009. Diversity and distribution of sediment nirS-encoding bacterial assemblages in response to environmental gradients in the eutrophied Jiaozhou Bay, China. Microb. Ecol. 58:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dang, H. Y., J. Li, X. X. Zhang, T. G. Li, F. Tian, and W. Jin. 2009. Diversity and spatial distribution of amoA-encoding archaea in the deep-sea sediments of the tropical West Pacific Continental Margin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106:1482-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dang, H. Y., J. Ren, L. S. Song, S. Sun, and L. G. An. 2008. Diverse tetracycline resistant bacteria and resistance genes from coastal waters of Jiaozhou Bay. Microb. Ecol. 55:237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dang, H. Y., J. Ren, L. S. Song, S. Sun, and L. G. An. 2008. Dominant chloramphenicol-resistant bacteria and resistance genes in coastal marine waters of Jiaozhou Bay, China. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24:209-217. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dang, H. Y., T. G. Li, M. N. Chen, and G. Q. Huang. 2008. Cross-ocean distribution of Rhodobacterales bacteria as primary surface colonizers in temperate coastal marine waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:52-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dang, H. Y., X. X. Zhang, J. Sun, T. G. Li, Z. N. Zhang, and G. P. Yang. 2008. Diversity and spatial distribution of sediment ammonia-oxidizing Crenarchaeota in response to estuarine and environmental gradients in the Changjiang Estuary and East China Sea. Microbiology 154:2084-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Bie, M. J. M., A. G. Speksnijder, G. A. Kowalchuk, T. Schuurman, G. Zwart, J. R. Stephen, O. E. Diekmann, and H. J. Laanbroek. 2001. Shifts in the dominant populations of ammonia-oxidizing β-subclass Proteobacteria along the eutrophic Schelde estuary. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 23:225-236. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng, B., J. Zhang, G. Zhang, and J. Zhou. 2010. Enhanced anthropogenic heavy metal dispersal from tidal disturbance in the Jiaozhou Bay, North China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 161:349-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dollhopf, S. L., J. H. Hyun, A. C. Smith, H. J. Adams, S. O'Brien, and J. E. Kostka. 2005. Quantification of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and factors controlling nitrification in salt marsh sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:240-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falkowski, P. G. 1997. Evolution of the nitrogen cycle and its influence on the biological sequestration of CO2 in the ocean. Nature 387:272-275. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foesel, B. U., A. Gieseke, C. Schwermer, P. Stief, L. Koch, E. Cytryn, J. R. de la Torré, J. van Rijn, D. Minz, H. L. Drake, and A. Schramm. 2008. Nitrosomonas Nm143-like ammonia oxidizers and Nitrospira marina-like nitrite oxidizers dominate the nitrifier community in a marine aquaculture biofilm. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 63:192-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Francis, C. A., G. D. O'Mullan, and B. B. Ward. 2003. Diversity of ammonia monooxygenase (amoA) genes across environmental gradients in Chesapeake Bay sediments. Geobiology 1:129-140. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francis, C. A., J. M. Beman, and M. M. Kuypers. 2007. New processes and players in the nitrogen cycle: the microbial ecology of anaerobic and archaeal ammonia oxidation. ISME J. 1:19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freitag, T. E., and J. I. Prosser. 2003. Community structure of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria within anoxic marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1359-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freitag, T. E., and J. I. Prosser. 2004. Differences between betaproteobacterial ammonia-oxidizing communities in marine sediments and those in overlying water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3789-3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freitag, T. E., L. Chang, and J. I. Prosser. 2006. Changes in the community structure and activity of betaproteobacterial ammonia-oxidizing sediment bacteria along a freshwater-marine gradient. Environ. Microbiol. 8:684-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galloway, J., F. Dentener, D. Capone, E. Boyer, R. Howarth, S. Seitzinger, G. Asner, C. Cleveland, P. Green, E. Holland, D. Karl, A. Michaels, J. Porter, A. Townsend, and C. Vorosmarty. 2004. Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry 70:153-226. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glibert, P. M., S. Seitzinger, C. A. Heil, J. M. Burkholder, M. W. Parrow, L. A. Codispoti, and V. Kelly. 2005. The role of eutrophication in the global proliferation of harmful algal blooms: new perspectives and new approaches. Oceanography 18:198-209. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grommen, R., L. Dauw, and W. Verstraete. 2005. Elevated salinity selects for a less diverse ammonia-oxidizing population in aquarium biofilters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 52:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gruber, N., and J. N. Galloway. 2008. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 451:293-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayashi, T., R. Kaneko, M. Tanahashi, and T. Naganuma. 2007. Molecular diversity of the genes encoding ammonia monooxygenase and particulate methane monooxygenase from deep-sea sediments. Res. J. Microbiol. 2:530-537. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hollibaugh, J. T., N. Bano, and H. W. Ducklow. 2002. Widespread distribution in polar oceans of a 16S rRNA gene sequence with affinity to Nitrosospira-like ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1478-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunter, E. M., H. J. Mills, and J. E. Kostka. 2006. Microbial community diversity associated with carbon and nitrogen cycling in permeable shelf sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5689-5701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson, C. R., and A. Q. Weeks. 2008. Influence of particle size on bacterial community structure in aquatic sediments as revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5237-5240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim, O. S., P. Junier, J. F. Imhoff, and K. P. Witzel. 2008. Comparative analysis of ammonia monooxygenase (amoA) genes in the water column and sediment-water interface of two lakes and the Baltic Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 66:367-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klotz, M. G., and L. Y. Stein. 2008. Nitrifier genomics and evolution of the nitrogen cycle. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 278:146-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Könneke, M., A. E. Bernhard, J. R. de la Torre, C. B. Walker, J. B. Waterbury, and D. A. Stahl. 2005. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437:543-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koops, H. P., and A. Pommerening-Röser. 2001. Distribution and ecophysiology of the nitrifying bacteria emphasizing cultured species. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:1-9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kowalchuk, G. A., and J. R. Stephen. 2001. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: a model for molecular microbial ecology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:485-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kowalchuk, G. A., J. R. Stephen, W. De Boer, J. I. Prosser, T. M. Embley, and J. W. Woldendorp. 1997. Analysis of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria of the β subdivision of the class Proteobacteria in coastal sand dunes by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and sequencing of PCR-amplified 16S ribosomal DNA fragments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1489-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lam, P., M. M. Jensen, G. Lavik, D. F. McGinnis, B. Muller, C. J. Schubert, R. Amann, B. Thamdrup, and M. M. Kuypers. 2007. Linking crenarchaeal and bacterial nitrification to anammox in the Black Sea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7104-7109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Limpiyakorn, T., Y. Shinohara, F. Kurisu, and O. Yagi. 2005. Communities of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in activated sludge of various sewage treatment plants in Tokyo. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 54:205-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu, S. M., J. Zhang, H. T. Chen, and G. S. Zhang. 2005. Factors influencing nutrient dynamics in the eutrophic Jiaozhou Bay, North China. Prog. Oceanogr. 66:66-85. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu, Z., H. Wei, G. Liu, and J. Zhang. 2004. Simulation of water exchange in Jiaozhou Bay by average residence time approach. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 61:25-35. [Google Scholar]

- 55.López-Gutiérrez, J. C., S. Henry, S. Hallet, F. Martin-Laurent, G. Catroux, and L. Philippot. 2004. Quantification of a novel group of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the environment by real-time PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 57:399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lozupone, C. A., M. Hamady, S. T. Kelley, and R. Knight. 2007. Quantitative and qualitative β diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1576-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lydmark, P., R. Almstrand, K. Samuelsson, A. Mattsson, F. Sorensson, P. E. Lindgren, and M. Hermansson. 2007. Effects of environmental conditions on the nitrifying population dynamics in a pilot wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2220-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Magalhães, C. M., S. B. Joye, R. M. Moreira, W. J. Wiebe, and A. A. Bordalo. 2005. Effect of salinity and inorganic nitrogen concentrations on nitrification and denitrification rates in intertidal sediments and rocky biofilms of the Douro River estuary, Portugal. Water Res. 39:1783-1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magalhães, C., N. Bano, J. T. Hollibaugh, W. J. Wiebe, and A. A. Bordalo. 2007. Composition and activity of beta-Proteobacteria ammonia-oxidizing communities associated with intertidal rocky biofilms and sediments of the Douro River Estuary, Portugal. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103:1239-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Magalhães, C., N. Bano, W. J. Wiebe, A. A. Bordalo, and J. T. Hollibaugh. 2008. Dynamics of nitrous oxide reductase genes (nosZ) in intertidal rocky biofilms and sediments of the Douro River Estuary (Portugal), and their relation to N-biogeochemistry. Microb. Ecol. 55:259-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCaig, A. E., C. J. Phillips, J. R. Stephen, G. A. Kowalchuk, S. M. Harvey, R. A. Herbert, T. M. Embley, and J. I. Prosser. 1999. Nitrogen cycling and community structure of proteobacterial β-subgroup ammonia-oxidizing bacteria within polluted marine fish farm sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:213-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Molina, V., O. Ulloa, L. Farías, H. Urrutia, S. Ramírez, P. Junier, and K. P. Witzel. 2007. Ammonia-oxidizing β-proteobacteria from the oxygen minimum zone off northern Chile. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3547-3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mosier, A. C., and C. A. Francis. 2008. Relative abundance and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in the San Francisco Bay estuary. Environ. Microbiol. 10:3002-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mullins, T. D., T. B. Britschgi, R. L. Krest, and S. J. Giovannoni. 1995. Genetic comparisons reveal the same unknown bacterial lineages in Atlantic and Pacific bacterioplankton communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40:148-158. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakamura, Y., H. Satoh, T. Kindaichi, and S. Okabe. 2006. Community structure, abundance, and in situ activity of nitrifying bacteria in river sediments as determined by the combined use of molecular techniques and microelectrodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40:1532-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicolaisen, M. H., and N. B. Ramsing. 2002. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) approaches to study the diversity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 50:189-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Norton, J. M., M. G. Klotz, L. Y. Stein, D. J. Arp, P. J. Bottomley, P. S. Chain, L. J. Hauser, M. L. Land, F. W. Larimer, M. W. Shin, and S. R. Starkenburg. 2008. Complete genome sequence of Nitrosospira multiformis, an ammonia-oxidizing bacterium from the soil environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3559-3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Mullan, G. D., and B. B. Ward. 2005. Relationship of temporal and spatial variabilities of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria to nitrification rates in Monterey Bay, California. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:697-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ottosen, L. D. M., N. Risgaard-Petersen, L. P. Nielsen, and T. Dalsgaard. 2001. Denitrification in exposed intertidal mud-flats, measured with a new 15N-ammonium spray technique. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 209:35-42. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phillips, C. J., Z. Smith, T. M. Embley, and J. I. Prosser. 1999. Phylogenetic differences between particle-associated and planktonic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria of the β subdivision of the class Proteobacteria in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:779-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poret-Peterson, A. T., J. E. Graham, J. Gulledge, and M. G. Klotz. 2008. Transcription of nitrification genes by the methane-oxidizing bacterium, Methylococcus capsulatus strain Bath. ISME J. 2:1213-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prosser, J. I., and G. W. Nicol. 2008. Relative contributions of archaea and bacteria to aerobic ammonia oxidation in the environment. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2931-2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Purkhold, U., M. Wagner, G. Timmermann, A. Pommerening-Röser, and H. P. Koops. 2003. 16S rRNA and amoA-based phylogeny of 12 novel betaproteobacterial ammonia-oxidizing isolates: extension of the dataset and proposal of a new lineage within the nitrosomonads. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1485-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qin, Y. Y., D. T. Li, and H. Yang. 2007. Investigation of total bacterial and ammonia-oxidizing bacterial community composition in a full-scale aerated submerged biofilm reactor for drinking water pretreatment in China. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 268:126-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Risgaard-Petersen, N., M. H. Nicolaisen, N. P. Revsbech, and B. A. Lomstein. 2004. Competition between ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and benthic microalgae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5528-5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rotthauwe, J.-H., K.-P. Witzel, and W. Liesack. 1997. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4704-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rysgaard, S., P. Thastum, T. Dalsgaard, P. B. Christensen, and N. P. Sloth. 1999. Effects of salinity on NH4+ adsorption capacity, nitrification, and denitrification in Danish estuarine sediments. Estuaries 22:21-30. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Santoro, A. E., C. A. Francis, N. R. de Sieyes, and A. B. Boehm. 2008. Shifts in the relative abundance of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea across physicochemical gradients in a subterranean estuary. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1068-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Satoh, H., Y. Nakamura, and S. Okabe. 2007. Influences of infaunal burrows on the community structure and activity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in intertidal sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1341-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schloss, P. D., and J. Handelsman. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1501-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seitzinger, S. P. 1988. Denitrification in freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems: ecological and geochemical significance. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33:702-724. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shen, Z. L. 2001. Historical changes in nutrient structure and its influences on phytoplankton composition in Jiaozhou Bay. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 52:211-224. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shinkai, T., and Y. Kobayashi. 2007. Localization of ruminal cellulolytic bacteria on plant fibrous materials as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization and real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1646-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stehr, G., B. Biittcher, P. Dittberner, G. Rath, and H.-P. Koops. 1995. The ammonia-oxidizing nitrifying population of the River Elbe estuary. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 17:177-186. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stein, L. Y., D. J. Arp, P. M. Berube, P. S. Chain, L. Hauser, M. S. Jetten, M. G. Klotz, F. W. Larimer, J. M. Norton, H. J. Op den Camp, M. Shin, and X. Wei. 2007. Whole-genome analysis of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium, Nitrosomonas eutropha C91: implications for niche adaptation. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2993-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stephen, J. R., A. E. McCaig, Z. Smith, J. I. Prosser, and T. M. Embley. 1996. Molecular diversity of soil and marine 16S rRNA gene sequences related to β-subgroup ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4147-4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stephen, J. R., Y. J. Chang, S. J. Macnaughton, G. A. Kowalchuk, K. T. Leung, C. A. Flemming, and D. C. White. 1999. Effect of toxic metals on indigenous soil β-subgroup proteobacterium ammonia oxidizer community structure and protection against toxicity by inoculated metal-resistant bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:95-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Urakawa, H., H. Maki, S. Kawabata, T. Fujiwara, H. Ando, T. Kawai, T. Hiwatari, K. Kohata, and M. Watanabe. 2006. Abundance and population structure of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria that inhabit canal sediments receiving effluents from municipal wastewater treatment plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6845-6850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Urakawa, H., S. Kurata, T. Fujiwara, D. Kuroiwa, H. Maki, S. Kawabata, T. Hiwatari, H. Ando, T. Kawai, M. Watanabe, and K. Kohata. 2006. Characterization and quantification of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in eutrophic coastal marine sediments using polyphasic molecular approaches and immunofluorescence staining. Environ. Microbiol. 8:787-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wakelin, S. A., M. J. Colloff, and R. S. Kookana. 2008. Effect of wastewater treatment plant effluent on microbial function and community structure in the sediment of a freshwater stream with variable seasonal flow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2659-2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang, C. Y., H. Y. Dang, and Y. S. Ding. 2008. Incidence of diverse integrons and β-lactamase genes in environmental Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Jiaozhou Bay, China. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24:2889-2896. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ward, B. B. 2005. Molecular approaches to marine microbial ecology and the marine nitrogen cycle. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33:301-333. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ward, B. B., D. Eveillard, J. D. Kirshtein, J. D. Nelson, M. A. Voytek, and G. A. Jackson. 2007. Ammonia-oxidizing bacterial community composition in estuarine and oceanic environments assessed using a functional gene microarray. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2522-2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang, G. L., J. Zhang, J. Xu, and F. Zhang. 2006. Distributions, sources and atmospheric fluxes of nitrous oxide in Jiaozhou Bay. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 68:557-566. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang, Y., X. H. Ruan, H. J. Op den Camp, T. J. Smits, M. S. Jetten, and M. C. Schmid. 2007. Diversity and abundance of aerobic and anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria in freshwater sediments of the Xinyi River (China). Environ. Microbiol. 9:2375-2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.