Abstract

Trypanosoma brucei adapts to changing environments as it cycles through arrested and proliferating stages in the human and tsetse fly hosts. Changes in protein tyrosine phosphorylation of several proteins, including NOPP44/46, accompany T. brucei development. Moreover, inactivation of T. brucei protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1 (TbPTP1) triggers differentiation of bloodstream stumpy forms into tsetse procyclic forms through unknown downstream effects. Here, we link these events by showing that NOPP44/46 is a major substrate of TbPTP1. TbPTP1 substrate-trapping mutants selectively enrich NOPP44/46 from procyclic stage cell lysates, and TbPTP1 efficiently and selectively dephosphorylates NOPP44/46 in vitro. To provide insights into the mechanism of NOPP44/46 recognition, we determined the crystal structure of TbPTP1. The TbPTP1 structure, the first of a kinetoplastid protein-tyrosine phosphatase (PTP), emphasizes the conservation of the PTP fold, extending to one of the most diverged eukaryotes. The structure reveals surfaces that may mediate substrate specificity and affords a template for the design of selective inhibitors to interfere with T. brucei transmission.

Keywords: Crystal Structure, Development, Signal Transduction, Trypanosome, Tyrosine Protein Phosphatase (Tyrosine Phosphatase)

Introduction

Trypanosoma brucei causes human African trypanosomiasis or African sleeping sickness, which is marked by debilitating neurologic symptoms ranging from sensory impairment to the characteristic aberrant sleeping patterns that progress to coma. If untreated, human African trypanosomiasis is fatal. With 30,000 deaths a year and 60 million people living at risk (1), human African trypanosomiasis is a major disease burden in sub-Saharan Africa. Current drugs are ineffective and toxic, and drug resistance is becoming a growing hurdle for treatment (2).

T. brucei alternates between human and tsetse fly hosts, requiring extensive and rapid physiologic adaptations. In humans, the major T. brucei population consists of the extracellular, proliferative slender form in the bloodstream, which irreversibly differentiates into the G1-arrested stumpy form poised for transmission to the tsetse fly. Taken up by the tsetse fly, the stumpy form differentiates into the proliferative procyclic form in the insect midgut. Eventually, the tsetse salivary gland becomes populated with metacyclic forms, which infect the human host (3). This differentiation cycle requires survival in a diverse set of environments and forms the basis for infectivity and transmission.

The molecular signals, regulators, and effectors underlying this complex sequence of events are not well understood but could provide novel targets for therapeutic interference. Distinct patterns of protein tyrosine phosphorylation accompany and often precede stage progression (4), suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation is a key mechanism of developmental regulation. Studies of the T. brucei dual specificity kinases also provide evidence that tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the trypanosome life cycle (5–7). Moreover, NOPP44/46,2 a nucleolar RNA-binding protein required for ribosome biogenesis (8), exhibits dramatic changes in tyrosine phosphorylation in concert with the T. brucei life cycle transitions (9). NOPP44/46 is tyrosine-phosphorylated in both proliferating procyclic and non-proliferating stumpy forms, but not in proliferating slender forms, indicating a complex interplay between life cycle and cell cycle in modulating tyrosine phosphorylation.

Recently, TbPTP1, a PTP with sequence similarity to classical human PTPs, was identified as a central molecular switch for the stumpy-to-procyclic progression (10). TbPTP1 activity arrests stumpy bloodstream forms, suggesting a model in which TbPTP1 inactivation in the fly midgut releases the arrest and triggers development into the procyclic form (10). Thus, TbPTP1 might function downstream of the recently described proteins associated with differentiation (PAD) transporters, which represent the first known step in the pathway that allows the differentiation signals citrate or cis-aconitate to trigger developmental changes (11). However, the substrates and downstream effects of TbPTP1 remain unknown.

By sequence comparison, TbPTP1 is similar to human classical PTPs such as the prototypical PTP1B. TbPTP1 has an ortholog in Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania major and contains six regions that appear to be specific to trypanosomatids (10). The Kinetoplastida, including T. brucei, constitute some of the most diverged eukaryotes. The evolutionary distance and unique sequences raise the question whether the overall structural conservation of the PTP fold is maintained in these distant eukaryotes.

Here, we identify NOPP44/46 as a major substrate of the life cycle switch TbPTP1. We also describe the TbPTP1 crystal structure, revealing strong conformational similarity to other eukaryotic PTPs and surface characteristics that help rationalize NOPP44/46 binding. Trypanosome-specific sequence motifs follow the canonical PTP fold, and all major functional elements are structurally conserved. These data establish the structural correlates of kinetoplastid PTPs within the PTP family and provide a new link in the signaling pathway controlling the stumpy-to-procyclic transition.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Protein Expression, and Purification

The full-length TbPTP1 (systematic ID Tb10.70.0070) gene was amplified from genomic T. brucei DNA (kindly provided by Dr. Christian Klotz) and cloned into the pET28b expression vector in-frame with the N-terminal six-histidine tag. Point mutants were generated according to the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene). BL21 (DE3)-CodonPlus cells were transformed, and protein expression was induced at A600 of 0.6 by adding 100 μm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. After 20 h of induction at 20 °C, cells were harvested, resuspended in 20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, and lysed by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged for 1 h at 20,000 × g, and the supernatant was loaded on a metal-chelating affinity column. Fractions containing TbPTP1 were identified by measuring the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (12). Fractions were pooled, loaded on a gel filtration column, and eluted in 20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl. Recombinant TbPTP1 was concentrated to 10 mg/ml.

In Vitro Dephosphorylation

NOPP44/46 (Genbank accession number HM44803) was amplified from T. brucei strain 29.13 (13) genomic DNA and cloned into pLEW-MHTAP (14) for expression in procyclic form T. brucei 29.13. Expression of the tagged protein was induced with tetracycline for 24 h, and the protein was purified using a modified tandem affinity purification protocol with 1 mm sodium orthovanadate in the lysis buffer (15, 16). The purified preparation was treated with 10 mm dithiothreitol for 15 min to inactivate the sodium orthovanadate. Dephosphorylation reactions were carried out at room temperature for 15 min in 20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl buffer, with varying amounts of TbPTP1. For dephosphorylation of NOPP44/46 with other PTPs, PTP input was normalized to the activity of 100 nm TbPTP1 at a saturating concentration of the non-cognate substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate. Reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and detected by Western blot using the 4G10 anti-Tyr(P) antibody. Blots were stripped and reprobed with monoclonal anti-NOPP44/46 1D2 (9).

Substrate Trapping

TbPTP1 resin was prepared by coupling TbPTP1 to NHS-activated SepharoseTM 4 fast flow (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Wild-type or the D199A mutant TbPTP1 was coupled at a concentration of 1 mg/ml followed by an incubation in 0.1 m Tris blocking buffer. Lysates were prepared from procyclic form T. brucei grown for 16 h in medium containing 1.5 μm sodium orthovanadate. Cells were extracted in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EGTA, 1% Triton X-100) containing 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science), and 5 mm iodoacetamide to inhibit endogenous PTP activity. Iodoacetamide and orthovanadate were inactivated by the addition of 10 mm dithiothreitol. To capture substrates of TbPTP1, 10 μl of wild-type or D199A TbPTP1 resin was incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with 500 μl of lysate corresponding to 0.5 × 109 T. brucei cells. The resin was washed five times in high salt buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 2 m NaCl, 15% glycerol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) followed by five washes alternating in guanidine-HCl buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 200 mm guanidine-HCl, 15% glycerol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) and low salt buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, 15% glycerol). The resin was boiled in reducing SDS-PAGE buffer for 15 min, run on a 12% Tris-glycine gel, and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for Western analysis with 4G10 anti-Tyr(P) (GE Healthcare) and anti-NOPP44/46 antibody (9). To control for input of recombinant wild-type and trapping TbPTP1, TbPTP1 was released from the column material by boiling in SDS sample buffer prior to trapping and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Crystallization, Structure Determination, and Structure Analysis

Initial crystals were obtained by sitting drop vapor diffusion trials at 18 °C from a 1:1 mixture of TbPTP1 at 10 mg/ml and 10% polyethylene glycol 3000, 100 mm CHES, pH 9.5. Diffraction quality crystals were obtained by hanging drop vapor diffusion after introducing mutations E138A, E139A, and E140A, predicted to reduce the surface entropy of TbPTP1 (17), the addition of 10 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, and in-drop trypsin cleavage of the His6 tag using a trypsin:TbPTP1 ratio of 1:1,000 (w/w). Crystals were immersed in mother liquor containing 10% glycerol, mounted, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Diffraction data were collected at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Advanced Light Source Beamline 8.3.1. Data were reduced using the HKL2000 program suite (18). Phases were obtained by molecular replacement using MolRep (19) and the search model PTPN3 (Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession 2B49) modified by CHAINSAW (20). After automated model building in PHENIX (21), the final model was built by alternating manual model building using Coot (22) and maximum likelihood refinement using PHENIX. The Rfree was determined using a random 5% of the data. The structure was validated using MOLProbity (23). Images were generated in PyMOL, and structure comparisons were performed using the DALI server and PDBsum. The crystal structure was deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 3M4U.

RESULTS

TbPTP1 Binds NOPP44/46

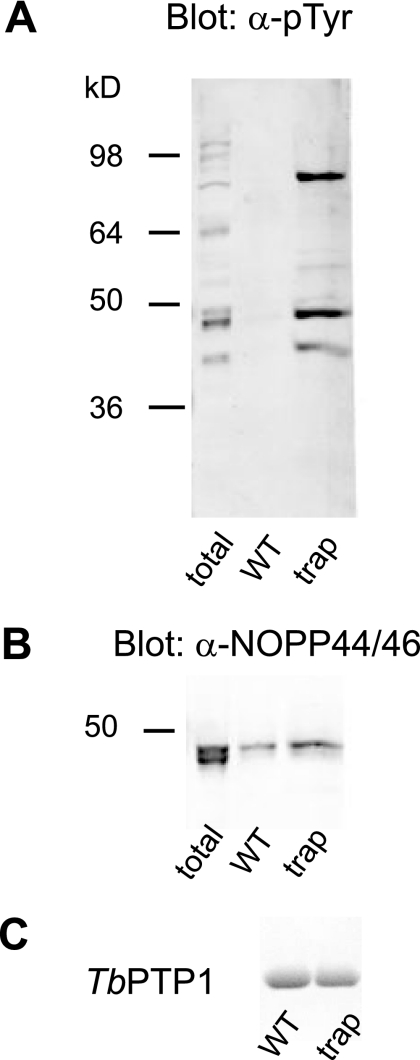

To identify cellular substrates of TbPTP1, we generated a substrate-trapping mutant by replacing the general acid Asp199 with Ala. This mutant is catalytically inactive but retains substrate binding, thus allowing for stable trapping and isolation of substrates (24). Based on previous studies suggesting that TbPTP1 is inactive and tyrosine phosphorylation most pronounced in procyclic forms (4, 10), we used cell lysates from T. brucei procyclic forms for trapping experiments. Tyrosine phosphorylation was preserved throughout cell lysis by the addition of iodoacetamide and sodium orthovanadate to inhibit endogenous PTPs. The wild-type and D199A TbPTP1 variants were covalently linked to NHS-Sepharose beads and incubated with T. brucei lysate. After high salt, guanidinium hydrochloride, and detergent washes, bound proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Western blotting of eluates using anti-Tyr(P) antibody showed the enrichment of several tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins by the D199A mutant relative to the wild-type TbPTP1 (Fig. 1A). Two major bands migrated at a molecular mass of ∼45 and ∼70 kDa, and a minor band migrated at ∼40 kDa. The enrichment of these bands was selective as other Tyr(P) proteins apparent in the total lysate were not trapped by TbPTP1.

FIGURE 1.

Substrate trapping identifies NOPP44/46 as a major TbPTP1 substrate. A, anti-Tyr(P) (α-pTyr) Western blot after TbPTP1 substrate trapping. The trapping mutant (trap) selectively enriches three major tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. WT, wild type. B, anti-NOPP44/46 Western blot of proteins bound to wild type and trapping mutant. The Western blot in B is an experimental replicate of A and identifies the ∼45-kDa band as NOPP44/46. Some phospho-independent binding is also apparent. C, Coomassie Blue staining showing equivalent amounts of TbPTP1 wild type and mutant elute from the resin prior to trapping.

Because the molecular mass of the 45-kDa species corresponded to that of NOPP44/46, a protein known to be tyrosine-phosphorylated in procyclic forms in vivo (4, 9), we explored the possibility that NOPP44/46 was a trapped substrate of TbPTP1. Experimental replicates of trapping eluates were probed with anti-NOPP44/46, resulting in signal at the position identical to the band detected with anti-Tyr(P) antibodies (Fig. 1B). Some phospho-independent binding of NOPP44/46 to wild-type TbPTP1 was also observed. The specific enrichment of phosphorylated NOPP44/46 with the trapping TbPTP1 identifies NOPP44/46 as a potential in vivo substrate of TbPTP1.

TbPTP1 Dephosphorylates NOPP44/46 in Vitro

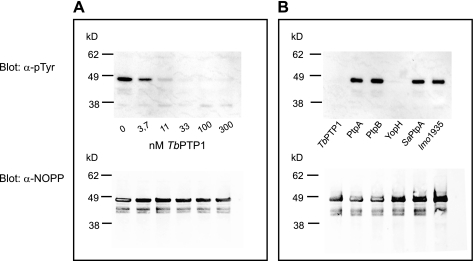

To confirm the observed interaction between TbPTP1 and NOPP44/46, we tested dephosphorylation of NOPP44/46 by TbPTP1 in vitro. Although the pH optimum of TbPTP1 is 6 (10), this preference is unlikely to reflect physiologic function rather than the generally higher nucleophilicity of cysteine residues at low pH. In vitro dephosphorylation assays were therefore performed at pH 7.5, more similar to the pH at which TbPTP1 likely functions. Phosphorylated NOPP44/46 was obtained by overexpressing a C-terminally TAP-tagged version of the full-length protein in procyclic forms. Rapid dephosphorylation of NOPP44/46 was observed at the lowest TbPTP1 concentration tested (3.7 nm) and was complete at TbPTP1 concentrations at or above 33 nm (Fig. 2A). To test whether dephosphorylation of NOPP44/46 by TbPTP1 is specific, we tested the activity of a panel of unrelated microbial PTPs on NOPP44/46. Of the five tested PTPs, only TbPTP1 and Yersinia YopH dephosphorylated NOPP44/46; no activity was observed using Mycobacterium tuberculosis PtpA and PtpB, Staphylococcus aureus SaPtpA, or Listeria monocytogenes lmo1935 (Fig. 2B). With YopH known to have broad substrate specificity (25), these data show complete, efficient, and selective dephosphorylation of NOPP44/46 by TbPTP1 in vitro.

FIGURE 2.

TbPTP1 efficiently and selectively dephosphorylates NOPP44/46 in vitro. A TAP-tagged allele of NOPP44/46 was expressed in procyclic forms and affinity-purified for dephosphorylation reactions. A, TbPTP1 dephosphorylates NOPP44/46 in a dose-dependent manner. α-pTyr, anti-Tyr(P) antibody. B, TbPTP1, but not unrelated phosphatases from M. tuberculosis (PtpA and PtpB), S. aureus (SaPtpA), and L. monocytogenes (lmo1935), dephosphorylates NOPP44/46.

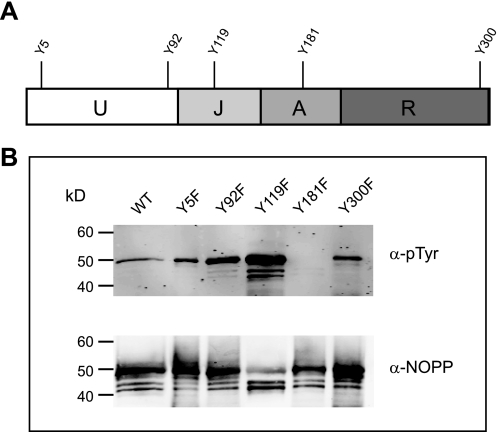

NOPP44/46 Is Phosphorylated on Tyr181

To define the phosphorylation site(s) on NOPP44/46 recognized by TbPTP1, we assessed the phosphorylation state of NOPP44/46 variants in which each of the five Tyr residues was replaced individually with Phe. Y181F completely abrogated tyrosine phosphorylation of NOPP44/46, as shown by anti-Tyr(P) Western analysis (Fig. 3). None of the other mutations reduced the level of NOPP44/46 Tyr phosphorylation, indicating that Tyr181 is the only phosphorylated Tyr and the target of TbPTP1. The NOPP44/46 phosphorylation site is located in a 40-residue acidic loop encompassing residues 167–207. The sequence of this segment, 167DAGDEDDNDDDDEAYDEDDSDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDE207, indicates that phosphorylation adds additional negative charges to a nearly uninterrupted acidic sequence. This acidic region containing the target Tyr is found only in T. brucei homologs.

FIGURE 3.

NOPP44/46 is phosphorylated on Tyr181. A, schematic of NOPP44/46 indicating domain organization and position of the five tyrosine residues. U, unique region; J, junction; A, acidic region; R, RGG repeat region. B, all five NOPP44/46 tyrosines were individually changed to Phe, and the phosphorylation of NOPP44/46 was detected by anti-Tyr(P) antibody (α-pTyr) (upper panel) and anti-NOPP44/46 control Western (lower panel). WT, wild type.

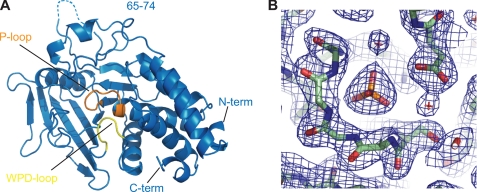

TbPTP1 Has a Classical PTP Fold

To explore the basis for recognition of the unusual substrate target sequence and the architecture of this diverged kinetoplastid PTP, we determined the crystal structure of TbPTP1 at 2.4 Å resolution (Table 1). The asymmetric unit contains two TbPTP1 molecules with a root mean square (r.m.s.) deviation of all atoms of 0.3 Å. The structure comprises residues Ser6–Thr301 in chain A and residues Met1–Leu298 in chain B (Fig. 4), as well as one phosphate per TbPTP1 and 192 water molecules. No clear electron density was visible for residues Leu66–Gln73 and Ala160–Ala162 of chain A and residues Lys67–Arg75, Ala140, and Gln147–His151 of chain B. The protein contains four changes. The catalytic cysteine is changed to alanine, possibly through desulfurization by the phosphine tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine present at high concentrations in the protein drop, and Glu138-140 were mutated to alanine to improve the crystallization properties of the protein (17).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for TbPTP1

Parentheses denote values for the highest resolution shell.

| Data collection | |

| Crystal symmetry | P212121 |

| Unit cell | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 76.63, 77.38, 117,2 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.4 |

| Rmerge (%) | 10 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.46 (97) |

| Multiplicity | 5 (4.9) |

| I/σI | 54 (2.5) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution (Å) | 47-2.4 |

| Reflections | 28,040 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 20/26 |

| r.m.s. Δ bonds (Å) | 0.008 |

| r.m.s. Δ angles (°) | 1.065 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 42.4 |

| Main chain dihedral angles | |

| Most favored (%) | 96.6 |

| Allowed (%) | 3.2 |

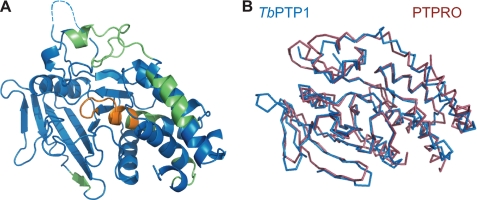

FIGURE 4.

Overall structure of TbPTP1. A, TbPTP1 shares the canonical PTP fold. The catalytic motifs P-loop and WPD loop are highlighted in orange and yellow, respectively. No electron density for residues 65–74 was visible in chain A (dotted line). N-term, N terminus; C-term, C terminus. B, 2Fo − Fc electron density map of the active site showing phosphate (center), contoured at 1.0 σ.

The overall fold of TbPTP1 resembles that of other classical PTPs, with an extended, twisted β-sheet at the center and α-helices surrounding it (Fig. 4A). The catalytic loop, or P-loop, is situated at the center of the active site and comprises the invariant PTP signature motif Cys-Xaa5-Arg. A phosphate binds in the position similar to that of Tyr(P) substrate phosphate in PTP-peptide substrate structures (26) (Fig. 4B). The active site cavity is further delineated by the Tyr(P) loop that deepens the cavity to ∼9 Å, thus excluding Ser(P) and Thr(P) residues. The WPD loop containing the general acid Asp199 assumes a closed conformation, similar to that seen in other PTP structures with small ligands bound (27). TbPTP1 contains 9 of 10 PTP sequence motifs (28) in the same spatial organization as human PTPs. The six trypanosome-specific sequence motifs of TbPTP1 follow the canonical PTP fold and do not give rise to new structural features. Consistent with a role in substrate recognition or regulation, the trypanosome-specific sequences predominantly map to the surface of TbPTP1 (Fig. 5A). The phosphate engages in the typical interactions with the P-loop, hydrogen-bonding with six main chain amides and the invariant Arg235 side chain.

FIGURE 5.

TbPTP1 has a similar fold to human PTPs. A, trypanosome-specific sequence motifs (green) map on the surface outside of the active site (P-loop in orange). B, superposition of the Cα chain in ribbon representation showing overall strong similarity to human PTPRO.

The closest structural homologs of TbPTP1 found by the DALI server are the prototypical human PTP1B and PTPRO (Glepp1), with a Cα r.m.s. deviation of 2.1 and 2.2 Å, respectively. The superposition of TbPTP1 with PTPRO (PDB ID 2G59) shows the overall large similarity, with major differences only at the termini and surface loops (Fig. 5B). The TbPTP1 loop from 62 to 79, although mostly invisible in the structure, has shifted at the base when compared with the equivalent PTPRO loop and contains a single-residue insertion when compared with PTPRO and up to seven residues when compared with other human PTPs. The TbPTP1 loop 138–154 containing a PEST sequence shows the most divergence from the PTPRO structure.

TbPTP1 forms weak interactions between the two molecules in the asymmetric unit in the crystal (data not shown). The interactions comprise two symmetric salt bridges between Lys123 and Glu201, hydrogen bonds between Gly127 and Glu201, as well as 44 non-bonded interactions resulting in an interface of ∼500 Å2. PTPs such as PTPγ form dimers in the crystal and in solution (27). However, TbPTP1 migrates as a monomer in size exclusion chromatography (data not shown), suggesting that these contacts do not reflect a physiologic state but are a result of crystal packing.

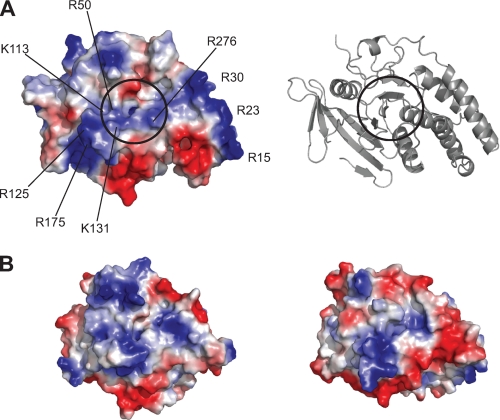

Although the three-dimensional organization of the PTP active site is highly similar in all PTPs across families, PTP surface properties vary widely and produce large diversity (27). The TbPTP1 electrostatic surface shows distinct and continuous electronegative and positive areas (Fig. 6). The active site shows moderately electropositive potential, with the closed WPD loop burying additional electropositive regions of the phosphate binding pocket. A continuous electropositive stretch runs across the active site and along one side of the molecule. This stretch includes the side chains of Arg15, -23, -30, -50, -125, -175, -276, and Lys113 and -131 (Fig. 6A). The electrostatic surface of PTP1B with a closed WPD loop also shows extended electropositive areas (Fig. 6B). These surfaces likely complement the sequence of the highly electronegative PTP1B substrate, the insulin receptor. PTP1B binds the triply phosphorylated peptide sequence pYETDpYpY, which also concentrates a large number of charges around the PTP1B active site. In contrast, PTPRO shows few electropositive areas outside of the direct active site vicinity and a predicted second Tyr(P) binding site (Fig. 6B, right panel).

FIGURE 6.

Electrostatic surface potential of TbPTP1. A, left, the TbPTP1 surface shows distinct electronegative (red) and positive (blue) regions, with a continuous electropositive stretch across the active site. The entry to the active site is indicated by the circle. Right, schematic representation in the same orientation as left panel. B, electrostatic surface representation of PTP1B (1SUG, left) and PTPRO (2G59, right) in the same orientation as TbPTP1. PTP1B also binds a highly negatively charged substrate and shows large electropositive areas.

DISCUSSION

T. brucei requires stringent control of developmental programs to successfully infect its human and tsetse fly hosts, and a molecular hallmark of life cycle transitions in T. brucei is the coordinated change in tyrosine phosphorylation. Recently, the tyrosine phosphatase TbPTP1 was identified as a key regulator of the trypanosome life cycle. TbPTP1 has an ortholog in T. cruzi with 61.3% sequence identity. Although an intracellular parasite, T. cruzi shares the bloodstream-to-insect route of transmission controlled by TbPTP1 in T. brucei, suggesting that the function of the two PTPs may be conserved.

Despite the evolutionary distance between humans and trypanosomes, our crystal structure of TbPTP1 shows a high degree of structural conservation of the conventional PTP fold. The 24% sequence identity of TbPTP1 to human PTP1B translates into a Cα r.m.s. deviation of 2.1 Å. The conservation of the PTP fold thus extends not only to bacteria but also to distant eukaryotes and underscores the utility and evolutionary success of this scaffold for tyrosine dephosphorylation. TbPTP1 shares 9 of 10 signature motifs with the human PTPs and has six additional trypanosome-specific motifs that may play roles in functional regulation or substrate recognition. The folding of these motifs suggests that although not giving rise to new structural elements, their position mostly on the surface is consistent with a role in substrate recognition and/or regulation.

The TbPTP1 structure also provides the basis for inhibitor design. The strong similarity to human PTPs highlights the need for structural information to guide the design of selective TbPTP1 inhibitors as tools and potential therapeutics. TbPTP1 prevents premature differentiation of stumpy bloodstream forms to procyclic forms, which lack immune evasion mechanisms that allow survival in the mammalian host. Thus, inhibition of TbPTP1 would reduce the pool of tsetse-infective parasites within the mammalian host, potentially attenuating transmission, an approach that has gained acceptance for the reduction of malaria (29). Blocking transmission could be particularly advantageous for controlling animal trypanosomiasis, which affects livestock and remains a major hurdle to economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, T. brucei rhodesiense infects both humans and animals, providing a parasite reservoir for human infection.

Although tyrosine phosphorylation is emerging as a key regulator of the trypanosome life cycle, little is known about the molecular pathways that lead to downstream developmental changes. Identification of TbPTP1 substrates is essential to understanding the mechanisms by which TbPTP1 regulates T. brucei differentiation. Among the phosphoproteins selectively enriched using a TbPTP1 trapping mutant, we identified NOPP44/46 and yet unidentified ∼70- and ∼40-kDa phosphoproteins as substrates of this PTP. Other substrate phosphoproteins might be associated with the insoluble fraction and not detected by our methods. The functional interaction of TbPTP1 and NOPP44/46 is supported by efficient and selective in vitro dephosphorylation. Furthermore, the phosphorylation pattern of NOPP44/46 during developmental stages, unlike that of other major tyrosine-phosphorylated species, matches the proposed activity profile of TbPTP1 in slender and procyclic forms (4, 9). The presence of phosphorylated NOPP44/46 in stumpy forms may reflect decreasing TbPTP1 activity or changes in the activity of the cognate kinase(s) in combination with a large increase in NOPP44/46 protein levels observed in stumpy forms (9).

The TbPTP1 crystal structure allows rationalizing NOPP44/46 substrate binding. The distinct, continuous electropositive area running across the TbPTP1 surface and the active site might be a footprint of electronegative regions of its substrate(s), such as the acidic stretch harboring the NOPP44/46 Tyr(P). Phosphorylation sites are usually found in flexible loop regions, suggesting that linear sequences rather than conformational sites serve as dephosphorylation substrates. This is consistent with the NOPP44/46 dephosphorylation site, which is predicted to be highly disordered. Moreover, the kinetics of substrate peptide turnover by PTPs are often approaching the limits of diffusion, suggesting that the selectivity and binding determinants of peptides are contained within the primary peptide sequence (30).

A phosphoproteomic study of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in T. brucei procyclic forms identified 34 phosphoproteins (31). NOPP44/46 Tyr181, however, was not identified, likely due to experimental limitations of that study. By immunofluorescence, phosphotyrosine proteins mostly associated with the cytoskeleton and the nucleolus, which is also the site of NOPP44/46 (32). A physiological interaction between TbPTP1 and NOPP44/46 would require cellular co-localization, and consistent with this tenet, TbPTP1 was found to associate with the cytoskeletal and nuclear fractions (10). However, it remains possible that NOPP44/46 is dephosphorylated outside of the nucleus as a recent study suggests that a pool of NOPP44/46 is exported out of the nucleus via exportin 1 (33).

TbPTP1 is a molecular switch for the stumpy-to-procyclic transition as both genetic and pharmacological inhibition of the phosphatase lead to spontaneous differentiation of committed stumpy forms to procyclic forms in vitro (10). Because trypanosomatids do not use transcriptional control to regulate expression of protein-coding genes (with a few exceptions), the key substrates of TbPTP1 that mediate this effect are likely to modulate mRNA stability, translation, or protein turnover. The identification of a known ribosome biogenesis protein, NOPP44/46 (8), as a potential in vivo substrate of TbPTP1 points toward a possible role in translational control. For example, the tyrosine phosphorylation state of NOPP44/46 may modulate ribosome biogenesis, which would in turn affect translational capacity. This possibility will be examined in future studies. Alternatively, NOPP44/46 may have uncharacterized cellular functions in addition to its essential role in ribosome biogenesis that could play specific roles in differentiation. In vivo, NOPP44/46 acts as a structural scaffold for several nucleolar proteins (34, 35), and its phosphorylation state may modulate these interactions to promote specific cellular changes. Studies in other organisms suggest the existence of functional links between proteins involved in ribosome biogenesis and development, highlighting complex yet conserved modes of developmental regulation. In zebrafish, Pescadillo, an essential gene required for nucleolar assembly and 60 S biogenesis, was originally discovered in a screen for regulators of embryonic development (36–39). In yeast, the Pescadillo ortholog, Yph1p, is found in two distinct multiprotein complexes with different functions in ribosome biogenesis and DNA replication (40). Interestingly, depletion of NOPP44/46 (44) and Yph1p both lead to cell cycle arrest with defective S-phase progression (40, 41). Furthermore, the ribosomal biogenesis factors such as nucleolin and nucleophosmin play roles in the cytosol or nucleus distinct from their function in ribosome biogenesis (42, 43). As other substrates of TbPTP1 are identified and tools for the study of TbPTP1 in vivo are refined, we will be better able to determine how these processes act together or apart to influence trypanosomatid differentiation and potentially provide insight into a novel signaling mechanism conserved in eukaryotic development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine L. Gee for help with model building and refinement, the staff at the Advanced Light Source Beamline 8.3.1 for help with data collection, and Carolina Vega and Charles Kifer for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AI31077 (to M. P.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3M4U) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- NOPP44/46

- nucleolar phosphoprotein 44/46

- TbPTP1

- T. brucei protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1

- PTP

- protein-tyrosine phosphatase

- r.m.s.

- root mean square

- CHES

- 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fèvre E. M., Wissmann B. V., Welburn S. C., Lutumba P. (2008) PLoS. Negl. Trop. Dis. 2, e333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brun R., Blum J., Chappuis F., Burri C. (2010) Lancet 375, 148–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenn K., Matthews K. R. (2007) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 539–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parsons M., Valentine M., Deans J., Schieven G. L., Ledbetter J. A. (1991) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 45, 241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.García-Salcedo J. A., Nolan D. P., Gijón P., Gómez-Rodriguez J., Pays E. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 45, 307–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z., Wang C. C. (2006) Eukaryot. Cell 5, 1026–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller I. B., Domenicali-Pfister D., Roditi I., Vassella E. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3787–3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen B. C., Brekken D. L., Randall A. C., Kifer C. T., Parsons M. (2005) Eukaryot. Cell 4, 30–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsons M., Ledbetter J. A., Schieven G. L., Nel A. E., Kanner S. B. (1994) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 63, 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szöor B., Wilson J., McElhinney H., Tabernero L., Matthews K. R. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 175, 293–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean S., Marchetti R., Kirk K., Matthews K. R. (2009) Nature 459, 213–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montalibet J., Skorey K. I., Kennedy B. P. (2005) Methods 35, 2–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wirtz E., Leal S., Ochatt C., Cross G. A. (1999) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 99, 89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen B. C., Kifer C. T., Brekken D. L., Randall A. C., Wang Q., Drees B. L., Parsons M. (2007) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 151, 28–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panigrahi A. K., Schnaufer A., Carmean N., Igo R. P., Jr., Gygi S. P., Ernst N. L., Palazzo S. S., Weston D. S., Aebersold R., Salavati R., Stuart K. D. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 6833–6840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rigaut G., Shevchenko A., Rutz B., Wilm M., Mann M., Séraphin B. (1999) Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 1030–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldschmidt L., Cooper D. R., Derewenda Z. S., Eisenberg D. (2007) Protein Sci. 16, 1569–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–76315299374 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein N. (2008) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 41, 641–643 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen V. B., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flint A. J., Tiganis T., Barford D., Tonks N. K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 1680–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z. Y., Clemens J. C., Schubert H. L., Stuckey J. A., Fischer M. W., Hume D. M., Saper M. A., Dixon J. E. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 23759–23766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salmeen A., Andersen J. N., Myers M. P., Tonks N. K., Barford D. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 1401–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barr A. J., Ugochukwu E., Lee W. H., King O. N., Filippakopoulos P., Alfano I., Savitsky P., Burgess-Brown N. A., Müller S., Knapp S. (2009) Cell 136, 352–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen J. N., Mortensen O. H., Peters G. H., Drake P. G., Iversen L. F., Olsen O. H., Jansen P. G., Andersen H. S., Tonks N. K., Møller N. P. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 7117–7136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White N. J. (2008) Malar. J. 7, Suppl. 1, S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z. Y. (2002) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 42, 209–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nett I. R., Davidson L., Lamont D., Ferguson M. A. (2009) Eukaryot. Cell 8, 617–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das A., Peterson G. C., Kanner S. B., Frevert U., Parsons M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 15675–15681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hellman K., Prohaska K., Williams N. (2007) Eukaryot. Cell 6, 2206–2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park J. H., Brekken D. L., Randall A. C., Parsons M. (2002) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 119, 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park J. H., Jensen B. C., Kifer C. T., Parsons M. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 173–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allende M. L., Amsterdam A., Becker T., Kawakami K., Gaiano N., Hopkins N. (1996) Genes Dev. 10, 3141–3155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinoshita Y., Jarell A. D., Flaman J. M., Foltz G., Schuster J., Sopher B. L., Irvin D. K., Kanning K., Kornblum H. I., Nelson P. S., Hieter P., Morrison R. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6656–6665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lerch-Gaggl A., Haque J., Li J., Ning G., Traktman P., Duncan S. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45347–45355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maiorana A., Tu X., Cheng G., Baserga R. (2004) Oncogene 23, 7116–7124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du Y. C., Stillman B. (2002) Cell 109, 835–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das A., Park J. H., Hagen C. B., Parsons M. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111, 2615–2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inder K. L., Lau C., Loo D., Chaudhary N., Goodall A., Martin S., Jones A., van der Hoeven D., Parton R. G., Hill M. M., Hancock J. F. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28410–28419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okuda M., Horn H. F., Tarapore P., Tokuyama Y., Smulian A. G., Chan P. K., Knudsen E. S., Hofmann I. A., Snyder J. D., Bove K. E., Fukasawa K. (2000) Cell 103, 127–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Worthen C., Jensen B. C., Parsons M. (2010) PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. e678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]