Abstract

Objective To study the association between method of attempted suicide and risk of subsequent successful suicide.

Design Cohort study with follow-up for 21-31 years.

Setting Swedish national register linkage study.

Participants 48 649 individuals admitted to hospital in 1973-82 after attempted suicide.

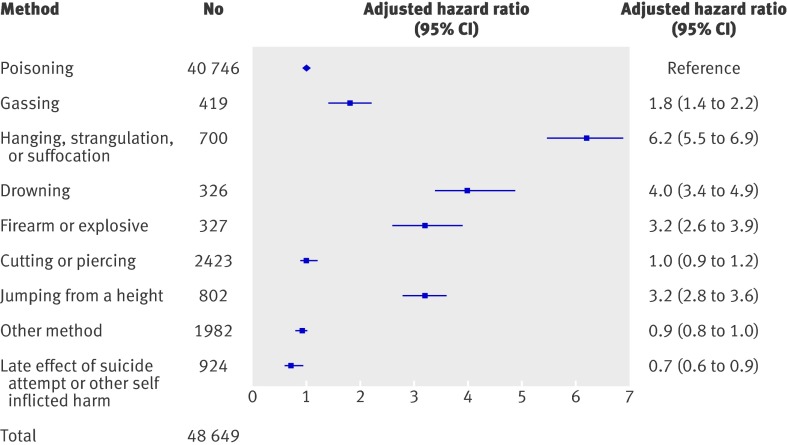

Main outcome measure Completed suicide, 1973-2003. Multiple Cox regression modelling was conducted for each method at the index (first) attempt, with poisoning as the reference category. Relative risks were expressed as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Results 5740 individuals (12%) committed suicide during follow-up. The risk of successful suicide varied substantially according to the method used at the index attempt. Individuals who had attempted suicide by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation had the worst prognosis. In this group, 258 (54%) men and 125 (57%) women later successfully committed suicide (hazard ratio 6.2, 95% confidence interval 5.5 to 6.9, after adjustment for age, sex, education, immigrant status, and co-occurring psychiatric morbidity), and 333 (87%) did so with a year after the index attempt. For other methods (gassing, jumping from a height, using a firearm or explosive, or drowning), risks were significantly lower than for hanging but still raised at 1.8 to 4.0. Cutting, other methods, and late effect of suicide attempt or other self inflicted harm conferred risks at levels similar to that for the reference category of poisoning (used by 84%). Most of those who successfully committed suicide used the same method as they did at the index attempt—for example, >90% for hanging in men and women.

Conclusion The method used at an unsuccessful suicide attempt predicts later completed suicide, after adjustment for sociodemographic confounding and psychiatric disorder. Intensified aftercare is warranted after suicide attempts involving hanging, drowning, firearms or explosives, jumping from a height, or gassing.

Introduction

Suicide is a leading cause of death, and improving assessment and treatment of those at risk is paramount in clinical medicine in general and clinical psychiatry in particular.1 The risk of suicide after an unsuccessful attempt is around 10% over follow-up of 5-35 years.2 3 4 5 6 Male sex, older age in women, psychiatric disorder,7 8 9 and higher suicidal intent7 10 11 12 13 14 are identified risk factors. Improved accuracy in the evaluation of risk after a suicide attempt, however, is important. For example, although suicidal intent certainly seems relevant,7 available instruments show inconsistent results concerning the relation between suicidal intent and future suicide; furthermore, low specificity of predictive factors restricts the precision of predictions.11

Characteristics of attempted suicide, such as being well planned, drastic, or violent, might imply a higher risk of a later successful attempt.15 Despite being theoretically likely and clinically informative, however, this issue has been little investigated. One underpowered study of suicide after an attempted suicide in patients with severe depression found no differences related to method.16 Among patients who poisoned themselves, highly lethal attempts were related to higher risk for completed suicide.14 Finally, a follow-up of 876 people admitted to hospital after a first ever suicide attempt suggested that violent index attempts were associated with 2.5 times higher risk of subsequent successful suicide than non-violent attempts.17

Most attempted suicides involve self poisoning or cutting,18 both sometimes classified as non-violent.19 Consequently, even large samples might not include sufficient numbers of attempts by various other methods to study variability regarding risk of completed suicide. To help focus aftercare on individuals at high risk of suicide, we conducted a nationwide cohort study of all 48 649 attempts in which individuals were treated in hospital in Sweden in 1973-82. We linked several national registers to compare risks of suicide by method over a 21-31 year follow-up. Drawing on a previous study,9 we controlled for sociodemographic confounding and co-occurring psychiatric disorder. We hypothesised higher risk of eventual suicide among those using methods other than poisoning at the index suicide attempt.

Methods

By linking Swedish national registers, we conducted a cohort study including all individuals admitted to hospital in 1973-82 after a suicide attempt. We studied how the attempted method predicted subsequent successful suicide during a follow-up of 21-31 years.

Participants

We identified all individuals living in Sweden in 1973-82 (9.4 million) by unique personal identification numbers and linked data from the hospital discharge register (national coverage from 1973 for psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts; reporting is mandatory for all healthcare providers, including private hospitals) and the cause of death register (both held by the National Board of Health and Welfare), the 1970 population and housing census, and the education and migration registers (the latter three held by Statistics Sweden).

From these, we selected individuals aged 10 or older who were admitted to inpatient care in Sweden during 1973-82 because of suicidal behaviour, defined as a definite (ICD-8 (international classification of diseases, eighth revision) codes E950-9) or uncertain suicide attempt (codes E980-9) according to the hospital discharge register (n=49 509). In people with more than one admission, we defined the first as the index attempt. We excluded 860 individuals who immigrated within two years before baseline to avoid confounding by stressful effects of being in the asylum seeking process. Hence, the final cohort included 48 649: 23 538 men and 25 111 women (mean age 38 (SD 16) years and 37 (SD 17), respectively).

Variables

ICD-8 E codes provided information on the method used for each suicide attempt, classified as poisoning; cutting or piercing; gassing; hanging, strangulation, or suffocation; drowning; using a firearm or explosive; jumping from a height; other method; and late effect of suicide attempt or other self inflicted harm (such as a diagnosis of pneumonia after previous poisoning). During the period when ICD-8 was used, the hospital discharge register classified suicide attempts by only one (principal) method. Psychiatric morbidity was classified as a principal diagnosis of non-organic psychotic disorder (ICD-8 codes 295, 297, 298.2-9, 299), affective disorder (codes 296, 298.0-1, 300.4, 301.1), or other psychiatric disorder (codes 290-294, 300-315 except 300.4 and 301.1) present at discharge from the index admission for a suicide attempt or at discharge from the first inpatient episode beginning within one week after the index episode.

Education was measured on a seven step ordinal scale, ranging from not having completed the nine years of compulsory school to postgraduate education, by using the 1970 population and housing census and the education register for 1990, 2000, and 2004. First generation immigrant status was obtained from the migration register. Swedish national registers are generally of good to excellent quality, and linkage offers unique possibilities for epidemiological research.20

Analyses and statistical methods

All patients were followed from hospital discharge for attempted suicide to a definite or uncertain suicide (ICD-8-9 codes E950-9 and E980-9; ICD-10 codes X60-84 and Y10-34), death other than suicide, first emigration, or end of follow-up (31 December 2003). Uncertain suicides were included, as exclusion might underestimate suicide rates.21

We followed patients for 21-31 years and determined absolute mortality from suicide after a previous attempt separately by method and sex. Multiple Cox regression modelling was conducted for each index method, with poisoning as the reference category. We checked that proportional hazards were constant over time by plotting the partial residuals. These curves showed no evidence of deviations from random distributions, indicating that the assumption of the model was not violated (data not shown). Relative risks were expressed as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals, adjusted for age, sex, education, immigrant status, and co-occurring psychiatric disorder. SPSS for Windows (version 17) was used for all analyses.

Results

During the 21-31 year follow-up, of the 48 649 people admitted to hospital after an attempted suicide, 5740 (11.8%) later successfully committed suicide (table 1). Attempted suicide by poisoning was the most common method (83.8% of attempters) and was linked to 4270 later suicides. The highest relative risk for eventual successful suicide (53.9% in men, 56.6% in women) was found for those in whom the index attempt was by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation.

Table 1.

Method used in index suicide attempt and later successful suicide among 48 649 individuals treated for attempted suicide in Sweden 1973-82 and followed up to 2003

| Suicide attempt method | No of attempts | Suicide within 1 year after attempt | No (%) of suicides during follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | Percentage of all suicides during follow-up | |||

| Total | 48 649 | 2041 (4.2) | 35.6 | 5740 (11.8) |

| Men | ||||

| Poisoning | 18 225 | 572 (3.1) | 25.5 | 2247 (12.3) |

| Cutting or piercing | 1686 | 62 (3.7) | 28.3 | 219 (13.0) |

| Gassing | 318 | 38 (11.9) | 55.1 | 69 (21.7) |

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation | 479 | 226 (47.2) | 87.6 | 258 (53.9) |

| Drowning | 165 | 36 (21.8) | 72.0 | 50 (30.3) |

| Firearm or explosive | 287 | 77 (26.8) | 77.8 | 99 (34.5) |

| Jumping from a height | 467 | 122 (26.1) | 78.7 | 155 (33.2) |

| Other method | 1403 | 65 (4.6) | 52.0 | 125 (8.9) |

| Late effect of suicide attempt/other self inflicted harm | 508 | 13 (2.6) | 34.2 | 38 (7.5) |

| All methods | 23 538 | 1211 (5.1) | 37.1 | 3260 (13.8) |

| Women | ||||

| Poisoning | 22 521 | 541 (2.4) | 26.7 | 2023 (9.0) |

| Cutting or piercing | 737 | 25 (3.4) | 31.6 | 79 (10.7) |

| Gassing | 101 | 8 (7.9) | 53.3 | 15 (14.9) |

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation | 221 | 107 (48.4) | 85.6 | 125 (56.6) |

| Drowning | 161 | 55 (34.2) | 78.6 | 70 (43.5) |

| Firearm or explosive | 40 | 1 (2.5) | 33.3 | 3 (7.5) |

| Jumping from a height | 335 | 51 (15.2) | 68.9 | 74 (22.1) |

| Other method | 579 | 29 (5.0) | 50.0 | 58 (10.0) |

| Late effect of suicide attempt/other self inflicted harm | 416 | 13 (3.1) | 39.4 | 33 (7.9) |

| All methods | 25 111 | 830 (3.3) | 33.5 | 2480 (9.9) |

The proportion of all completed suicides that occurred within the first year of follow-up was 26-32% for index methods of poisoning and cutting or piercing (table 1). This proportion was substantially higher for other methods (53-88%), except for attempts involving firearms or explosives in women, when the number of cases was small.

In the analysis of relative suicide risk by method used at the index attempt, we used poisoning as reference category (figure). Compared with poisoning, hanging in particular, but also drowning, using a firearm or explosive, jumping from a height, or gassing, conferred substantially higher risk of future successful suicide. Similar or lower risks were found for cutting or piercing, other methods, or late effect of suicide attempt or other self inflicted harm.

Method of index suicide attempt and risk of later successful suicide among 48 649 individuals treated for attempted suicide in Sweden 1973-82 and followed to 2003. Hazard ratios from Cox regression models adjusted for sex, age, highest education, immigrant status, and psychiatric disorder (psychotic disorder, affective disorder, other psychiatric disorder)

Psychotic disorder (hazard ratio 2.5, 95% confidence interval 2.2 to 2.8), affective disorder (1.5, 1.4 to 1.6), and other psychiatric disorder (1.2, 1.2 to 1.3) were independent risks for successful suicide. When we stratified method of attempt by co-occurring psychiatric disorder (table 2), hanging and comorbid psychotic disorder implied high rates of suicide (58/69 (84%) during the entire follow-up and 48/69 (70%) within the first year for men; 27/32 (84%) and 22/32 (69%), respectively, for women).

Table 2.

Successful suicide during follow-up for different methods of index suicide attempt stratified by psychiatric diagnosis* in 38 837 people who attempted suicide and were admitted to hospital during 1973-82 in Sweden and followed up to 2003. Figures are numbers (percentages) and hazard ratios† with 95% confidence intervals

| Diagnostic group and method | Men (n=17 762) | Women (n=20 075) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No | Suicide within 1 year after index attempt | Suicide during follow-up | HR (95% CI) | Total No | Suicide within 1 year after index attempt | Suicide during follow-up | HR (95% CI) | ||

| No psychiatric diagnosis | |||||||||

| Poisoning | 9696 | 323 (3.3) | 981 (10.1) | Reference | 12 871 | 300 (2.3) | 863 (6.7) | Reference | |

| Gassing | 143 | 15 (10.5) | 25 (17.5) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.6) | 61 | 5 (8.2) | 7 (11.5) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.8) | |

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation | 142 | 75 (52.8) | 80 (56.3) | 8.3 (6.6 to 10.5) | 57 | 25 (43.9) | 28 (49.1) | 9.0 (6.1 to 13.1) | |

| Drowning | 78 | 10 (12.8) | 13 (16.7) | 1.9 (1.1 to 3.3) | 44 | 9 (20.5) | 11 (25.0) | 4.7 (2.6 to 8.5) | |

| Firearm or explosive | 209 | 58 (27.8) | 69 (33.0) | 3.9 (3.0 to 4.9) | 31 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Cutting or piercing | 807 | 27 (3.3) | 76 (9.4) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) | 295 | 7 (2.4) | 19 (6.4) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | |

| Jumping from a height | 280 | 89 (31.8) | 97 (34.6) | 4.7 (3.8 to 5.8) | 192 | 33 (17.2) | 44 (22.9) | 3.8 (2.8 to 5.1) | |

| Non-organic psychotic disorder | |||||||||

| Poisoning | 373 | 24 (6.4) | 81 (21.7) | Reference | 520 | 25 (4.8) | 85 (16.3) | Reference | |

| Gassing | 12 | 7 (58.3) | 8 (66.7) | 5.4 (2.6 to 11.2) | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 20.0 (2.7 to 147.1) | |

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation | 69 | 48 (69.6) | 58 (84.1) | 8.6 (6.0 to 12.2) | 32 | 22 (68.8) | 27 (84.4) | 13.7 (8.7 to 21.5) | |

| Drowning | 18 | 8 (44.4) | 12 (66.7) | 6.2 (3.3 to 11.6) | 19 | 12 (63.2) | 13 (68.4) | 9.7 (5.3 to17.8) | |

| Firearm or explosive | 9 | 5 (55.6) | 5 (55.6) | 4.2 (1.7 to 10.4) | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2.8 (0.4 to 20.3) | |

| Cutting or piercing | 95 | 5 (5.3) | 24 (25.3) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) | 41 | 2 (4.9) | 6 (14.6) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.1) | |

| Jumping from a height | 37 | 12 (32.4) | 18 (48.6) | 3.1 (1.9 to 5.2) | 34 | 7 (20.6) | 9 (26.5) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.5) | |

| Affective disorder | |||||||||

| Poisoning | 1700 | 70 (4.1) | 247 (14.5) | Reference | 3799 | 114 (3.0) | 459 (12.1) | Reference | |

| Gassing | 71 | 9 (12.7) | 19 (26.8) | 1.9 (1.2 to 3.0) | 22 | 2 (9.1) | 6 (27.3) | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.3) | |

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation | 149 | 71 (47.7) | 82 (55.0) | 5.7 (4.4 to 7.4) | 86 | 44 (51.2) | 50 (58.1) | 7.6 (5.7 to 10.3) | |

| Drowning | 26 | 9 (34.6) | 11 (42.3) | 3.9 (2.1 to 7.1) | 69 | 27 (39.1) | 33 (47.8) | 6.0 (4.2 to 8.5) | |

| Firearm or explosive | 22 | 11 (50.0) | 15 (68.2) | 7.7 (4.5 to 13.0) | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 7.1 (1.0 to 50.5) | |

| Cutting or piercing | 205 | 14 (6.8) | 36 (17.6) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) | 167 | 10 (6.0) | 23 (13.8) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) | |

| Jumping from a height | 32 | 13 (40.6) | 19 (59.4) | 6.9 (4.3 to 10.9) | 22 | 8 (36.4) | 10 (45.5) | 5.1 (2.7 to 9.6) | |

| Other psychiatric disorder | |||||||||

| Poisoning | 3043 | 84 (2.8) | 431 (14.2) | Reference | 2465 | 48 (1.9) | 252 (10.2) | Reference | |

| Gassing | 64 | 3 (4.7) | 12(18.8) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 9 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1.8 (0.3 to 13.2) | |

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation | 95 | 31(32.6) | 35 (36.8) | 3.7 (2.6 to 5.2) | 38 | 15 (39.5) | 18 (47.4) | 8.6 (5.3 to 14.0) | |

| Drowning | 27 | 8 (29.6) | 10 (37.0) | 3.8 (2.0 to 7.1) | 21 | 7 (33.3) | 9 (42.9) | 7.0 (3.6 to 13.7) | |

| Firearm or explosive | 14 | 2 (14.3) | 4 (28.6) | 2.2 (0.8 to 5.9) | 4 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Cutting or piercing | 314 | 10 (3.2) | 48 (15.3) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) | 148 | 3 (2.0) | 18 (12.2) | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.9) | |

| Jumping from a height | 32 | 6 (18.8) | 9 (28.1) | 2.5 (1.3 to 4.8) | 23 | 2 (8.7) | 6 (26.1) | 2.9 (1.3 to 6.6) | |

*Excludes 9812 people diagnosed between 1 week and 1 year after index attempt as these might represent subclinical psychiatric disorders not evident at index assessment and other methods and late effect of suicide attempt and other self inflicted harm.

†Adjusted for age, level of education, and immigrant status.

Most of those who successfully committed suicide used the same method as they did at the index attempt (table 3). This was most pronounced among those who used hanging in the index attempt, of whom 93% of men and 92% of women later died from suicide by hanging. High proportions also used the same method for the final successful attempt after attempts by drowning (82% of men and 86% of women), use of a firearm (men only), or jumping from a height.

Table 3.

Method at index attempt and at eventual successful suicide among 5740 people who had been admitted to hospital after attempted suicide during 1973-82 in Sweden and followed up to 2003

| Method* | Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index attempt | No (%) using same method at eventual suicide | Index attempt | No (%) using same method at eventual suicide | ||

| Poisoning | 2247 | 1283 (57) | 2023 | 1317 (65) | |

| Gassing | 69 | 43 (62) | 15 | 8 (53) | |

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation | 258 | 240 (93) | 125 | 115 (92) | |

| Drowning | 50 | 41 (82) | 70 | 60 (86) | |

| Firearms or explosives | 99 | 78 (79) | 3 | 1 (33) | |

| Cutting or piercing | 219 | 42 (19) | 79 | 5 (6) | |

| Jumping from a height | 155 | 119 (77) | 74 | 54 (73) | |

*Other methods and late effect of suicide attempt or other self inflicted harm are not shown.

Discussion

Use of methods other than poisoning and cutting, particularly hanging, for attempted suicide are moderately to strongly related to subsequent successful suicide. This should be taken into account in clinical practice in the evaluation of suicide risk and in the planning of care after a suicide attempt.

Strengths and limitations

By linking nationwide longitudinal registers, we attempted to minimise the selection bias and low power that have affected previous clinical studies. The resulting large cohort was followed for at least 21 years and provided data on suicide attempts and psychiatric morbidity. As the cause of death register covers more than 99% of all deaths in Swedish residents, including those occurring abroad, loss of information on outcome was minimal.22 Furthermore, we adjusted risk estimates for sociodemographic confounders and coexisting psychiatric morbidity. There were, however, some limitations. Firstly, the cohort included only people in whom the attempted suicide led to inpatient care. Therefore, our results might not apply to attempts not involving inpatient care. Such patients are generally difficult for mental health professionals to access, assess, and treat. Secondly, we did not study diagnostic subcategories in detail, psychiatric comorbidity, repeated suicide attempts,23 or the possible contribution of physical illness.24 Thirdly, we had no information on suicidal intent,13 hopelessness,25 or treatment efforts. Fourthly, though we adjusted for educational level, we lacked information on unemployment.26 Finally, despite a substantially higher relative risk for suicide after methods other than poisoning, most individuals (77% of men, 90% of women) used self poisoning at the index attempt and most subsequent suicides occurred among them (69% of all completed suicides in men, and 82% in women).

Interpretation

Cutting was not associated with higher suicide mortality than poisoning. This method usually represents low intention of suicide and rather reflects poor emotional regulation.27 As cutting seldom leads to admission to hospital,28 individuals who were admitted were possibly more help seeking or perceived as having a higher risk of suicide. We did not, however, evaluate the latter reason in our study.

Obviously, choice of method in those who attempt suicide might reflect suicidal intent, previously linked to poorer prognosis.11 29 30 In addition, some methods are more likely to lead to successful suicide independently of intent, by being more lethal.15 31 Regardless of this, however, suicide attempts by hanging and drowning in particular were strongly associated with risk of eventual successful suicide above the baseline risks represented by self poisoning and cutting.

In people with severe mental illness, such as a psychotic and affective disorder, methods such as hanging, drowning, and using a firearm indicated a particularly high risk. Even in those without documented psychopathology, hanging particularly implied an extremely high risk for subsequent suicide.

As in previous studies,7 9 32 33 suicide was particularly common during the first year after the index attempt, perhaps because of a distressing life situation or intense symptom rich phases of coexisting psychiatric disorder. For example, when we stratified analyses by psychiatric comorbidity, 69% of those who attempted suicide by hanging and had a psychotic disorder died from suicide within one year. The important short term excess in suicide rate after a suicide attempt by such means has not been acknowledged in previous studies and suggests possible benefits of more focused aftercare during the first few years after admission to hospital. For the sake of preventive measures, it should also be noted that patients often used the same method for the index attempt and the eventual successful suicide.

Conclusion

Aftercare for people who have attempted suicide is often based on estimates of suicidal intent.34 Other reports have suggested that psychiatric disorder should be considered in the evaluation of risk.9 Our findings strongly indicate that such assessments should also be guided by the method used as people who attempt suicide by hanging, drowning, shooting by firearm, or jumping from a height are at substantially higher risk for completed suicide in the short and long term. Furthermore, people who attempt suicide by highly lethal methods are likely to choose the same means at the final suicidal act.

What is already known on this topic

Previous suicide attempts constitute a strong risk factor for subsequent successful suicide

Coexisting psychiatric morbidity and suicidal intent further increase the risk

What this study adds

The method of the index attempt is moderately to strongly associated with risk of completed suicide

Suicide attempts involving hanging or strangulation, drowning, firearm, jumping from a height, or gassing are associated with a moderate to strong increased risk of suicide compared with poisoning

Contributors: BR had the original idea for the study, designed it, analysed results, and drafted the manuscript. DT managed the dataset and performed the statistical analyses. PL and NL were advisers on statistics. DT, NL, PL, and MD interpreted results and co-wrote the paper. BR is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet. NL is funded by the Swedish Research Council-Medicine.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare (1) no financial support for the submitted work from anyone other than their employer; (2) no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (3) no spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; and (4) no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the regional ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet (2005/174-31/4). Consent was not obtained but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c3222

References

- 1.Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet 2009;373:1372-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Moore GM, Robertson AR. Suicide in the 18 years after deliberate self-harm a prospective study. Br J Psychiatry 1996;169:489-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkins GR, Hale R, Papanastassiou M, Crawford MJ, Tyrer P. Suicide rate 22 years after parasuicide: cohort study. BMJ 2002;325:1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suokas J, Suominen K, Isometsä E, Ostamo A, Lönnqvist J. Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide—findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;104:117-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suominen K, Isometsä E, Suokas J, Haukka J, Achte K, Lönnqvist J. Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: a 37-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawton K, Zahl D, Weatherall R. Suicide following deliberate self-harm: long-term follow-up of patients who presented to a general hospital. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:537-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skogman K, Alsén M, Öjehagen A. Sex differences in risk factors for suicide after attempted suicide—a follow-up study of 1052 suicide attempters. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004;39:113-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tidemalm D, Långström N, Lichtenstein P, Runeson B. Risk of suicide after suicide attempt according to coexisting psychiatric disorder: Swedish cohort study with long term follow-up. BMJ 2008;337:a2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck AT, Schuyler D, Herman J. Development of suicidal intent scales. In: Beck AT, Resnick HL, Lettieri DJ, eds. The prediction of suicide. Charles Press, 1974:45-56.

- 11.Harriss L, Hawton K, Zahl D. Value of measuring suicidal intent in the assessment of people attending hospital following self-poisoning or self-injury. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:60-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niméus A, Alsén M, Träskman-Bendz L. High suicidal intent scores indicate future suicide. Arch Suicide Res 2002;6:211-9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierce DW. The predictive validation of a suicide intent scale: a five year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1981;139:391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suokas J, Lönnqvist J. Outcome of attempted suicide and psychiatric consultation: risk factors and suicide mortality during a five-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991;84:545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;294:2064-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brådvik L. Suicide after suicide attempt in severe depression: a long-term follow-up. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2003;33:381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holley HL, Fick G, Love EJ. Suicide following an inpatient hospitalization for a suicide attempt: a Canadian follow-up study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:543-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haukka J, Suominen K, Partonen T, Lönnqvist J. Determinants and outcomes of serious attempted suicide: a nationwide study in Finland, 1996-2003. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:1155-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Träskman L, Åsberg M, Bertilsson L, Sjöstrand L. Monoamine metabolites in CSF and suicidal behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:631-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamper-Jørgensen F, Arber S, Berkman L, Mackenbach J, Rosenstock L, Teperi J. Part 3: International evaluation of Swedish public health research. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2005;65:46-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neeleman J, Wessely S. Changes in classification of suicide in England and Wales: time trends and associations with coroners’ professional backgrounds. Psychol Med 1997;27:467-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Board of Health and Welfare. Cause of death register. www.socialstyrelsen.se/register/dodsorsaksregistret. 2009.

- 23.Nordentoft M, Breum L, Munck LK, Nordestgaard AG, Hunding A, Laursen Bjaeldager PA. High mortality by natural and unnatural causes: a 10 year follow up study of patients admitted to a poisoning treatment centre after suicide attempts. BMJ 1993;306:1637-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen B, Wang AG, Brille-Brahe U. Attempted suicide in Denmark. IV. A five-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990;81:250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niméus A, Träskman-Bendz L, Alsén M. Hopelessness and suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord 1997;42:137-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, Coutts A, McKee M. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet 2009;374:315-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuisku V, Pelkonen M, Kiviruusu O, Karlsson L, Ruuttu T, Marttunen M. Factors associated with deliberate self-harm behaviour among depressed adolescent outpatients. J Adolesc 2009;32:1125-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madge N, Hewitt A, Hawton K, de Wilde EJ, Corcoran P, Fekete S, et al. Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: comparative findings from the Child and Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008;49:667-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coryell W, Young EA. Clinical predictors of suicide in primary major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suominen K, Isometsä E, Ostamo A, Lönnqvist J. Level of suicidal intent predicts overall mortality and suicide after attempted suicide: a 12-year follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry 2004;4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conner KR, Phillips MR, Meldrum S, Knox KL, Zhang Y, Yang G. Low-planned suicides in China. Psychol Med 2005;35:1197-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordstrom P, Samuelsson M, Asberg M. Survival analysis of suicide risk after attempted suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995;91:336-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J. Excess mortality of suicide attempters. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawton K, Arensman E, Townsend E, Bremner S, Feldman E, Goldney R, et al. Deliberate self harm: systematic review of efficacy of psychosocial and pharmacological treatments in preventing repetition. BMJ 1998;317:441-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]