Abstract

Mutations in genes expressed in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) underlie a number of human inherited retinal disorders that manifest with photoreceptor degeneration. Because light-evoked responses of the RPE are generated secondary to rod photoreceptor activity, RPE response reductions observed in human patients or animal models may simply reflect decreased photoreceptor input. The purpose of this study was to define how the electrophysiological characteristics of the RPE change when the complement of rod photoreceptors is decreased. To measure RPE function, we used an electroretinogram (dc-ERG)-based technique. We studied a slowly progressive mouse model of photoreceptor degeneration (PrphRd2/+), which was crossed onto a Nyxnob background to eliminate the b-wave and most other postreceptoral ERG components. On this background, PrphRd2/+ mice display characteristic reductions in a-wave amplitude, which parallel those in slow PIII amplitude and the loss of rod photoreceptors. At 2 and 4 mo of age, the amplitude of each dc-ERG component (c-wave, fast oscillation, light peak, and off response) was larger in PrphRd2/+ mice than predicted by rod photoreceptor activity (RmP3) or anatomical analysis. At 4 mo of age, the RPE in PrphRd2/+ mice showed several structural abnormalities including vacuoles and swollen, hypertrophic cells. These data demonstrate that insights into RPE function can be gained despite a loss of photoreceptors and structural changes in RPE cells and, moreover, that RPE function can be evaluated in a broader range of mouse models of human retinal disease.

INTRODUCTION

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is in close physical proximity with the neural retina and supports its normal functions. Rod photoreceptor outer segments (OSs) interdigitate with the apical processes of the RPE where nutrient transport between the cells, phagocytosis of shed outer segments, regeneration of rhodopsin, and removal of metabolic end products by the RPE facilitate the health and function of the photoreceptors (Bok 1993; Marmorstein 2001; Strauss 2005). Mutations in RPE genes underlie some forms of retinitis pigmentosa (Maw et al. 1997), Leber's congenital amaurosis (Marlhens et al. 1997), Malattia Leventinese/Doyne Honeycomb retinal dystrophy (Marmorstein et al. 2002; Stone et al. 1999), and Sorsby's fundus dystrophy (Weber et al. 1994). These diseases are collectively characterized by photoreceptor degeneration, despite the restricted expression of the mutated genes to the RPE. This scenario, in which RPE gene defects initiate structural/functional disruption of photoreceptors, underscores the importance of understanding the relationship between RPE abnormalities and photoreceptor degeneration.

RPE function can be noninvasively measured in mice using a modified electroretinogram technique (dc-ERG). The light-evoked responses of the RPE are characterized by four relatively slow components identified as the c-wave, fast oscillation (FO), light peak (LP), and off response (OR). These components allow different aspects of RPE function to be monitored (Steinberg et al. 1985) and provide a means for the identification of RPE defects in mouse models of human photoreceptor degeneration (Strauss 2005). Despite being evoked by light stimuli, none of the dc-ERG components reflects a direct response of the RPE to light. Instead, each is generated secondary to rod photoreceptor activity (Steinberg 1985; Wu et al. 2004b). The initial c-wave reflects the interaction of two signals. A positive polarity component reflects the light-evoked hyperpolarization of the apical membrane of the RPE, generated in response to the decrease in subretinal [K+] induced by rod photoreceptor activity (Schmidt and Steinberg 1971; Steinberg et al. 1970). A negative polarity component (slow PIII) reflects Kir4.1 channel activity in Müller glial cells (Kofuji et al. 2000; Oakley and Green 1976; Steinberg and Miller 1973; Witkovsky et al. 1975). These components combine to define the c-wave recorded at the corneal surface (Wu et al. 2004a).

The negative polarity FO follows the c-wave and reflects the recovery of the c-wave and slow PIII as [K+] is restored in the subretinal space (SRS) and a delayed hyperpolarization of the basal RPE membrane from a [Cl−] conductance (Griff and Steinberg 1984; Linsenmeier and Steinberg 1982). The identity of the Cl− channel is not yet known, although the retention of the FO in mice lacking different Cl− channels (Cftr, Best1, Clcn2) argue against their playing a major role in FO generation (Edwards et al. 2010; Marmorstein et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2006).

The slow forming LP follows the FO and reflects the depolarization of the RPE basal membrane by a Cl−-based conductance (Fujii et al. 1992; Gallemore and Steinberg 1989, 1993; Linsenmeier and Steinberg 1982). Although it is possible to evoke a c-wave and FO from an isolated RPE preparation by reducing apical [K+], the LP is not generated (Gallemore et al. 1988; Steinberg et al. 1985). This observation led to the concept of a “light peak substance,” a ligand that is required for LP generation and is released by the neural retina in response to light that binds to a receptor located on the RPE. The identity of the light peak substance is not known, although a number of candidates have been examined (Dawis and Niemeyer 1986; Gallemore and Steinberg 1990; Joseph and Miller 1992; Nao-i et al. 1989; Quinn et al. 2001; Wu et al. 2004). Altered LPs in rodents treated with the voltage-dependent calcium channel (VDCC) blocker nimodipine or in mice lacking VDCC subunits (α1D, β4) implicate a role for calcium-sensitive Cl− channels in LP generation/regulation (Marmorstein et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2007). LPs are reduced in mice expressing a single Clcn2 allele (Edwards et al. 2010).

The OR is generated when light stimuli are extinguished. Unlike all other ERG components, the polarity of the mouse OR depends on stimulus intensity, indicating that this is a complex response with more than one underlying generator.

Because each dc-ERG component is generated secondarily to rod photoreceptor activation (Wu et al. 2004b), interpretation of dc-ERG components is most straightforward when the activity of rod photoreceptors (reflected in the ERG a-wave) is maintained at a normal level (Marmorstein et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2006, 2007). As noted earlier, however, many mouse models of RPE gene defects are associated with rod photoreceptor degeneration, which will alter the rod photoreceptor-derived signal delivered to the RPE and thus the generation of each dc-ERG component. To understand the relationship between a decrease in rod photoreceptor activity and the response properties of the dc-ERG, we used a well-studied model of photoreceptor degeneration, PrphRd2/+ mice (Cheng et al. 1997; Hawkins et al. 1985; Sanyal and Hawkins 1989). Originally named rds (retinal degeneration slow), PrphRd2/+ mice express a single wild-type peripherin/rds allele and show altered OS elaboration, resulting in short disorganized OSs with irregular membrane whorls (Hawkins et al. 1985). As these mice age, the outer retina exhibits a progressive loss of photoreceptors accompanied by thinning of the outer nuclear layer (ONL). Functionally, PrphRd2/+ mice display progressive reductions in a-wave amplitude, which coincide with photoreceptor degeneration (Cheng et al. 1997). We recorded light-evoked activity from the retina and RPE from these mice and control littermates over time to define the relationship between RPE function and loss of photoreceptor activity. We found that the dc-ERG components were maintained at larger amplitudes than predicted by measures of rod photoreceptor activity or structure. The data presented here indicate that the RPE can undergo extensive loss of input as well as damage to the RPE cells themselves without displaying a significant decrease in light-evoked activity, as demonstrated by the amplitude of dc-ERG components. Moreover, this study demonstrates that specific aspects of RPE function can be meaningfully evaluated despite a profound reduction in photoreceptor activity.

METHODS

Mice

PrphRd2 breeders were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and mated with Nyxnob mice, which lack the ERG b-wave component (Pardue et al. 1998) and in which anatomical defects have not been observed (Ball et al. 2003; Gregg 2007; Pardue et al. 1998). The resulting offspring were crossed to generate mice that were homozygous for the Nyxnob defect and carried one PrphRd2 allele or two Prph+ alleles. Throughout this study, Nyxnob mice that carry a single PrphRd2 allele will be referred to as PrphRd2/+, whereas Nyxnob mice that carry two Prph+ alleles will be referred to as controls or Prph+/+. Mice were screened for the Prph+ or PrphRd2 allele by polymerase chain reaction amplification using two sets of primers for each.

For Prph+ allele:

sense (5′-CCAGAAATAGGTTCGCTGTCC-3′)

antisense (5′-GATGGTCATAGCTGTAGTGCG-3′)

cylpn sense (5′-ATGACGAGCCCTTGGGC-3′)

cylpn antisense (5′-CAGGACATTGCGAGCAGATG-3′)

For PrphRd2 allele:

sense (5′-GACCCAGATTGCCTGTGGCA-3′)

antisense (5′-TGAGCCACAGCAGACGTTGG-3′)

actin sense (5′-GACAACGGCTCTGGCCTGGTG-3′)

actin antisense (5′-GTGTGGCAGGGCATAGCCCTC-3′)

Electroretinography

After overnight dark adaptation, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (16 mg/kg). Eye drops were used to anesthetize the cornea (1% proparacaine HCl) and to dilate the pupil (2.5% phenylephrine HCl, 1% tropicamide, and 1% cyclopentolate HCl). Mice were placed on a temperature-regulated heating pad throughout the recording session. All procedures involving animals were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Two stimulation-recording systems and protocols were used for this study. Strobe flash ERGs were recorded using a stainless steel electrode in contact with the corneal surface via 1% methylcellulose. Needle electrodes were placed in the cheek and the tail for reference and ground leads, respectively. Dark-adapted responses were presented within an LKC ganzfeld and recorded using flash intensities ranging from −3.6 to 2.1 log cd s/m2. Stimuli were presented in order of increasing intensity and the number of successive responses averaged together decreased from 20 for low-intensity flashes to 2 for the highest intensity stimuli. Conversely, the duration of the interstimulus interval (ISI) increased from 4 s for low-intensity flashes to 90 s for the highest-intensity stimuli. Responses were differentially amplified (0.3–1,500 Hz), averaged, and stored using a UTAS E-3000 signal averaging system (LKC Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD).

To measure ERG components generated by the RPE, we used a previously established protocol adapted for mouse recording (Wu et al. 2004b). Briefly, responses were obtained from the corneal surface of the left eye using an unpulled 1-mm-diameter borosilicate capillary tube with filament (BF100-50-10; Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA). The capillary was filled with Hank's buffered salt solution (HBSS) to make contact with a Ag/Ag Cl wire electrode. A similar electrode was placed in contact with the right eye, which was shielded from light stimulation, to serve as a reference lead. Responses were differentially amplified at dc-100 Hz; gain = ×1,000 (DP-301, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT), digitized at 20 Hz, and stored using LabScribe Data Recording Software (iWorx; Dover, NH). After the initial setup for each mouse was complete, the stability of the recording was monitored for several minutes prior to stimulus presentation. White light stimuli were derived from an optical channel using a Leica microscope illuminator as the light source and delivered to the test eye with a 1-cm-diameter fiber-optic bundle. The unattenuated stimulus luminance was 4.4 log cd/m2. For the mouse eye, this luminance corresponds to 6.8 log photoisomerizations per rod/s, based on the assumption that 1 photopic cd/m2 equals 1.4 scotopic cd/m2 for the tungsten halogen light source (Wyszecki and Stiles 1980) and that 1 scotopic cd/m2 is equivalent to 100 photoisomerizations per rod/s (Hetling and Pepperberg 1999). Neural density filters (Oriel Instruments, Stratford, CT) placed in the light path reduced the stimulus luminance. Calibrations of luminance were made with an LS-110 photometer (Minolta, Ramsey, NJ) focused on the output of the fiber-optic bundle. A Uniblitz shutter system was used to control stimulus duration at 7 min.

Mice were tested at 2 and 4 mo of age. Intensity–response functions for the strobe-flash ERG were obtained in a single session. Intensity–response functions for the dc-ERG were defined in several recording sessions, separated by ≥2 days with each day using a single stimulus intensity. An individual mouse underwent no more than four dc-ERG recording sessions.

ERG analysis

The amplitude of the a-wave was measured at 6 ms after flash presentation from the prestimulus baseline (see Fig. 1A). The leading edge of the a-waves obtained in response to high-intensity stimuli was analyzed with Eq. 1, a modified form of the Lamb–Pugh model of rod phototransduction (Hood and Birch 1994; Lamb and Pugh 1992; Pugh and Lamb 1993)

| (1) |

where P3 represents the massed response of the rod photoreceptors and is analogous to the PIII component of Granit (1933). The amplitude of P3 is expressed as a function of flash energy (i) and time (t) after flash onset. S is the gain of phototransduction, RmP3 is the maximum response, and td is a brief delay.

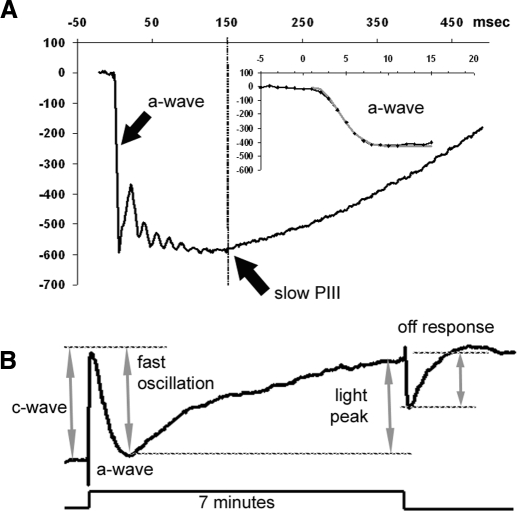

Fig. 1.

Representative electroretinogram (ERG) recordings obtained from a control (Prph+/+Nyxnob/nob) mouse. A: the characteristic waveform elicited by a 1 log cd s/m2 strobe flash. The slow PIII component and a-wave are denoted by black arrows. Slow PIII amplitude was measured 150 ms after onset of the flash as noted by the dotted line. The inset depicts the timing of the a-wave, which was analyzed by fitting the leading edge of the a-wave with Eq. 1. The fit to this example is indicated by the gray line. B: the characteristic waveform elicited by a 7 min 2.4 log cd/m2 light stimulus. Each dc-ERG component is identified and the manner in which each component was measured is shown by the gray arrows and dotted lines.

Amplitude of the slow PIII was measured from the prestimulus baseline to the value of the trough at 150 ms (see Fig. 1A) and fitted with the Naka–Rushton equation

| (2) |

where I is the stimulus luminance of the flash; R is the ERG amplitude at I luminance; Rmax is the asymptotic ERG amplitude; K is the half-saturation constant, corresponding to retinal sensitivity; and n is a dimensionless constant controlling the slope of the function.

Amplitudes of the dc-ERG components were calculated as previously described (see Fig. 1B; Wu et al. 2004b). The amplitude of the c-wave was measured from the prestimulus baseline to the maximum of the peak. The FO was measured from the peak of the c-wave to the minimum value of the trough. The LP amplitude was determined from the difference between the value of the asymptote and the value of the minimum of the FO trough. The OR amplitude was calculated by the difference between the maximum/minimum value of the waveform on light offset and the value of the LP asymptote.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

After mice were killed, the superior cornea was marked before enucleation. For immunohistochemistry, eyes were fixed in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 4% paraformaldehyde. After removal of the cornea and lens, the posterior pole was immersed through a graded series of sucrose solutions as follows: 10% for 1 h, 20% for 1 h, and 30% overnight. Eyes were embedded in OCT freezing medium, flash frozen on powderized dry ice, and immediately transferred to −80°C. Tissue was sectioned at 10 μm thickness with a cryostat (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) at −30°C, mounted on superfrost slides, and stored at −80°C until processed. Sections were blocked in 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 5% normal goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and then washed three times with PBS for 5 min each time. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody. Sections were rinsed with PBS three times for 10 min each time and incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa 488 or Alexa 594, 1:500; Molecular Probes) for 1 h at RT. After rinsing sections three times for 10 min each time with PBS, sections were mounted with DAPI (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and coverslipped. Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-peripherin/rds (1:500, a kind gift of Andy Goldberg, Oakland University) and mouse anti-ezrin (1:50; Neomarkers; Freemont, CA).

For light microscopy, eyes were fixed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 2% formaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The tissues were then osmicated, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, embedded in epoxy resin (Epon), and processed for evaluation. Sections (1 μm thick) were cut approximately along the horizontal meridian and through the optic nerve. Single eyes from at least three individual mice, taken from separate litters, were used for each time point.

Histological analysis and statistics

Sections were imaged with a fluorescence/differential interference contrast microscope (BX-61; Olympus, Tokyo), equipped with a charge-coupled device monochrome camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Bridgewater, NJ). Images were digitally captured (SlideBook software, version 4.2; Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO), using either a ×40 or ×100 (oil) objective and exported for analysis with Image ProPlus software (Image-Pro PLUS, version 6.2; Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). Thickness of the RPE, OS, inner segment layer (IS), outer plexiform layer (OPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), and inner plexiform layer (IPL) were measured in light microscopic fields that spanned nearly 200 μm and were centered 300 μm from the edge of the optic nerve head or 300 μm from the edge of the peripheral retina. The average number of photoreceptor nuclei spanning the ONL was also determined for each microscopic field. These measurements were performed on both sides of the optic nerve head and no differences were found between the regions. Hypertrophic RPE cells were counted in retinal sections from at least four mice per genotype.

For all graphs, error bars represent the SE.

RESULTS

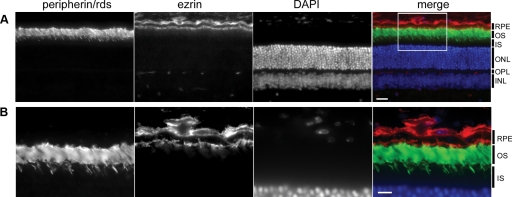

Peripherin/rds is not found in retinal pigment epithelial cells

Peripherin/rds is an integral transmembrane glycoprotein responsible for proper membrane folding of the photoreceptor disk array. As a semidominant mutation, expression of a single PrphRd2 allele prevents normal development of the photoreceptor outer segment, ultimately leading to progressive photoreceptor degeneration (Hawkins et al. 1985). Because we are investigating the response of the RPE to a loss of photoreceptor input using the PrphRd2/+ model, we began by assessing the localization of peripherin/rds in the retina and RPE. Figure 2 depicts an adult Prph+/+ retina stained for peripherin/rds (green) and ezrin (red) to identify the RPE microvilli. Ezrin is an epithelial cytoskeletal marker, which serves as a bridge between actin filaments and plasma membrane proteins and localizes to RPE microvilli (Bonilha et al. 2006). Sections were counterstained with DAPI (blue) and imaged to illustrate the localization of peripherin/rds in the retina and RPE. In agreement with previous reports, peripherin/rds was found to be limited to the retina, specifically to photoreceptor OSs (Fig. 2B; Arikawa et al. 1992; Travis et al. 1989). Therefore changes seen in dc-ERG components of PrphRd2/+ mice reflect changes in rod photoreceptor activity, not an intrinsic insult to the RPE itself.

Fig. 2.

Peripherin/retinal degeneration slow (rds) is not found in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). A: photomicrograph of an adult Prph+/+ retina section stained with anti-peripherin/rds (green). Sections were costained with anti-ezrin (red) antibodies to mark the apical microvilli of the RPE. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Each layer is identified. OS, outer segment layer; IS, inner segment layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer. Images were taken at ×40; scale bar = 20 μm. B: higher magnification (×100) photomicrograph of the denoted area from A; scale bar = 20 μm.

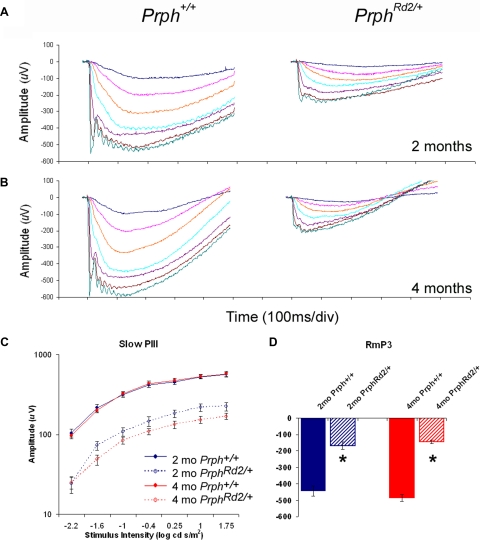

Strobe-flash electroretinogram components (a- wave, slow PIII) are progressively reduced in PrphRd2/+ mice with age

The ERG measures the summed potentials emitted by the retina/RPE in response to light. The hyperpolarization of rod photoreceptors underlies the a-wave (Penn and Hagins 1969), which is normally followed by the b-wave. The use of the Nyxnob genetic background eliminates the b-wave (Pardue et al. 1998), allowing slow PIII, which is generated by Müller cells (Witkovsky et al. 1975), to be measured directly (Wu et al. 2004a). Figure 3A represents the grand average of strobe-flash responses from Prph+/+ (n = 7) and PrphRd2/+ mice (n = 12) at 2 mo of age. Compared with Prph+/+ littermates at this age, PrphRd2/+ mice exhibit a 45% reduction in the Rmax amplitude of slow PIII and a 60% reduction in the maximum amplitude of the a-wave (RmP3) (Fig. 3, C and D, respectively). Consistent with a progressive photoreceptor degeneration, at 4 mo of age (Fig. 3B, n = 15 for each group), PrphRd2/+ mice exhibit a 70% reduction in RmP3 amplitude (Fig. 3C). Slow PIII is also further decreased at 4 mo, with Rmax reduced by 60% compared with Prph+/+ mice (Fig. 3D). Table 1 presents the values of RmP3, A, and td derived when Eq. 1 was fit to individual responses evoked by a 1 log cd s/m2 flash. In contrast to the significant reductions in RmP3, values of A obtained from PrphRd2/+ mice were not different from those from Prph+/+ mice at either 2 or 4 mo. This is consistent with previous findings (Birch et al. 1997; Cheng et al. 1997) and indicates that the amplification characteristics of the phototransduction cascade are operating normally. The amplitude of td was slightly larger in PrphRd2/+ mice than that in Prph+/+ mice at 2 mo. This may reflect an increased latency in the time rod photoreceptors take to respond, but a similar difference was not seen at 4 mo. Table 2 presents the values of Rmax, n, and K derived when Eq. 2 was fit to each individual response generated by a 1 log cd s/m2 flash. Although values of Rmax were significantly decreased, values for the slope parameter n were not different between genotypes at either age, whereas the sensitivity parameter K was significantly increased in PrphRd2/+ mice at both time points.

Fig. 3.

PrphRd2/+ mice exhibit reductions in a-wave and slow PIII amplitudes. Averaged ERG recordings for Prph+/+ and PrphRd2/+ mice at 2 (A, n = 7 and 12, respectively) and 4 (B, n = 15 for each) mo. C: the intensity–response function for slow PIII measured at 150 ms was generated. D: RmP3 in response to a 1 log cd s/m2 flash is also reported. Responses at 2 and 4 mo are shown in blue and red, respectively. Control animals are denoted by solid lines and mutant mice are identified by dotted lines.

Table 1.

Lamb and Pugh parameters fit to the light-evoked response elicited by a 1 log cd s/m2 stimulus

| RmP3 | A | td | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-mo Prph+/+ | −441.9 ± 30.4 | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 1.36 ± 0.16 |

| 2-mo PrphRd2/+ | −167.8 ± 22.8 | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 2.23 ± 0.31 |

| t-test | P < 0.0005 | n.s. | P = 0.042 |

| 4-mo Prph+/+ | −485.8 ± 20.7 | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 1.22 ± 0.14 |

| 4-mo PrphRd2/+ | −144.7 ± 10.8 | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 1.48 ± 0.26 |

| t-test | P < 0.0005 | n.s. | n.s. |

Values are means ± SE, n = 8–12/group at 2 mo; n = 15/group at 4 mo. n.s., not significant.

Table 2.

Naka–Rushton parameters fit to the slow PIII intensity–response functions

| Rmax | n | K | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-mo Prph+/+ | 569.6 ± 40.3 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.38 ± 0.07 |

| 2-mo PrphRd2/+ | 309.0 ± 25.3 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.14 |

| t-test | P < 0.0005 | n.s. | P = 0.010 |

| 4-mo Prph+/+ | 610.0 ± 37.0 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.37 ± 0.05 |

| 4-mo PrphRd2/+ | 248.0 ± 12.3 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.08 |

| t-test | P < 0.0005 | n.s. | P < 0.0005 |

Values are means ± SE, n = 8–12/group at 2 mo; n = 15/group at 4 mo. n.s., not significant.

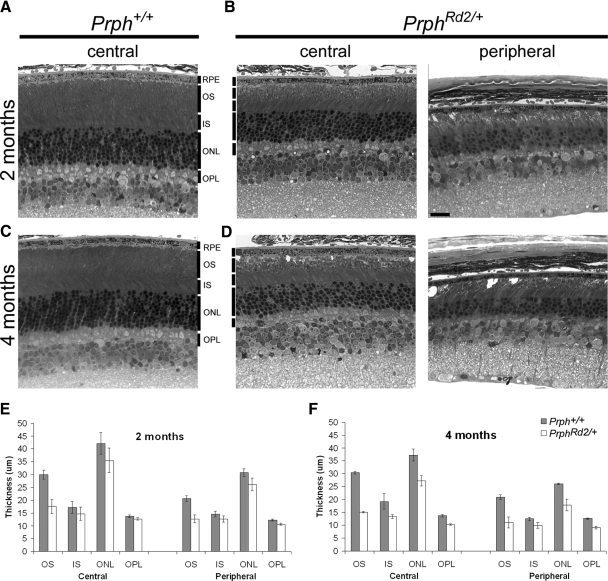

a-Wave amplitude reductions reflect rod photoreceptor degeneration in PrphRd2/+ mice

To define the relationship between rod photoreceptor integrity and a-wave amplitude we assessed the anatomical state of the retina at the time points studied electrophysiologically. Figure 4 depicts sections from Prph+/+ and PrphRd2/+ eyecups taken at 2 (Fig. 4, A and B) and 4 (Fig. 4, C and D) mo of age. Analysis was performed on both central (300 μm from the optic nerve head) and peripheral (300 μm from the distal edge of the retina) regions of the retina in sections passing through the optic nerve head. PrphRd2/+ mice displayed abnormalities in photoreceptor outer segments at 2 mo. Rod OSs were short and vacuoles were readily seen within this layer (Fig. 4, A and B). The thickness of the OS layer was reduced by roughly 40% in both central and peripheral regions. Additionally, photoreceptor death was under way because the thickness of the ONL in central regions of PrphRd2/+ retinas was 8.4 ± 1.03 cells per column compared with 10.75 ± 0.51 cells in Prph+/+ mice (Fig. 4, A, B). At 4 mo, the abnormalities seen in PrphRd2/+ mice were more pronounced (Fig. 4, C, D, F). Both the OS and IS layers of PrphRd2/+ mice were shorter and the remaining OSs were arranged in whorls. Compared with Prph+/+, OS length was reduced by roughly 50% in the PrphRd2/+ retina, whereas IS length was reduced by roughly 30%. OPL length was decreased by about 25% (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, ONL thickness was greatly reduced because PrphRd2/+mice had an average of 5.9 ± 0.22 cells per column (n = 3) in central regions of the ONL compared with 10.6 ± 0.42 cells spanning the central ONL in Prph+/+ mice (n = 4). At both ages examined, central and peripheral regions were equivalently affected in PrphRd2/+ mice. These data demonstrate the expected photoreceptor degeneration characteristic of PrphRd2/+ mice.

Fig. 4.

Slow degeneration of rod photoreceptors in PrphRd2/+ mice induces a progressive thinning of all inner retinal layers. Retinal cross sections obtained from 2 (A and B) and 4 (C and D) mo Prph+/+ and PrphRd2/+ mice. Light micrographs were taken from central (300 μm from the ONH [optic nerve head]) and peripheral (300 μm from the edge of the retina) areas of the retina. Each layer is identified. RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; OS, outer segment layer; IS, inner segment layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer. All images were taken at ×40. Scale bar = 20 μm. Thickness of each layer was measured at both time points (E and F, respectively). Compared with Prph+/+ mice, PrphRd2/+ mice have disorganized OSs and fewer photoreceptors (B). These changes become more severe at 4 mo, when vacuoles are apparent throughout the OS and each layer has become thinner (D).

The amplitude of the ERG a-wave reflects the mass response of rod photoreceptor OSs. As a consequence, a-wave amplitude will decrease when the total area of OSs are lost, due to OS shortening or a loss of rod photoreceptors. Both of these changes occur in PrphRd2/+ mice and we compared the extent of a-wave amplitude reduction with anatomical measures of the mutant retina. The thickness of the averaged central and peripheral ONL and OS length were reduced to 60 and 85% of Prph+/+, respectively. When these anatomical measures are combined, they predict that the PrphRd2/+ a-wave will be reduced to 51% of Prph+/+, which is somewhat lower than predicted by the reduction in RmP3 (62%). At 4 mo, RmP3 values of PrphRd2/+ mice were roughly 30% of Prph+/+ littermates. At this age, the averaged central and peripheral ONL thickness was 67% of Prph+/+ and OS length was 50% of Prph+/+ thickness, indicating that a-wave generators are reduced to about 33.5%. These data demonstrate that ERG component amplitudes in PrphRd2/+ mice correlate closely with the underlying anatomical structure at 4 mo, confirming that the a-wave can be used to quantify the number of functional OSs in the PrphRd2/+ retina and thus the effective stimulus to the RPE. Despite the disorganization of the OSs within the PrphRd2/+ mice, the basic structure of the retina is preserved and our data demonstrate that a-wave amplitude is a reliable measure of photoreceptor responsiveness.

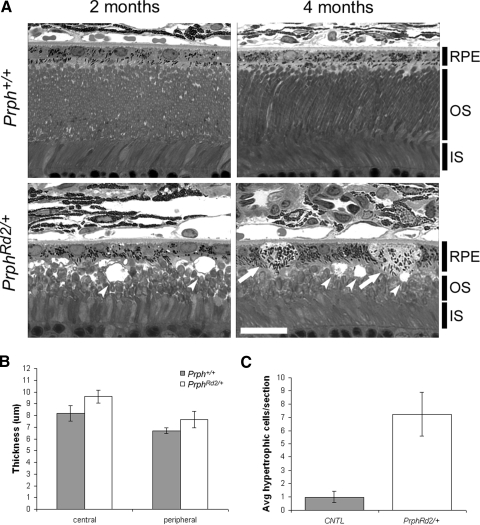

Hawkins et al. (1985) reported that 2- to 3-mo-old PrphRd2/+ mice have abnormally large phagosomes within the RPE and slow turnover of shed OS disks. Although these findings likely reflect the massive amount of rod photoreceptor material presented to the RPE in the PrphRd2/+ mutant, they also point toward a possible defect in RPE phagocytosis. Although rod photoreceptor degeneration was clearly evident in 2-mo-old mutants (Fig. 4), we found no changes in thickness or structure of the RPE cell layer at this time (Fig. 5A; Hawkins et al. 1985). At 4 mo, however, numerous vacuoles were observed in the OS layer and we also observed vacuolization in RPE cells (dimpled arrowheads, Fig. 5A). Furthermore, swollen, hypertrophic RPE cells, with lightly stained cytoplasm and reduced apical membranes were present throughout the epithelial layer (arrows, Fig. 4A). RPE layer thickness was also slightly greater in PrphRd2/+ mice compared with that in Prph+/+ animals (Fig. 5B). The density of hypertrophic cells (Fig. 5C) was greater in PrphRd2/+ mice (7.25 ± 1.65/section) compared with that in Prph+/+ (1.0 ± 0.41/section). Our findings demonstrate that PrphRd2/+ mice develop anatomical abnormalities in the RPE well after the onset of photoreceptor degeneration. These anatomical presentations allow us to examine RPE function following photoreceptor degeneration alone (2 mo) and when photoreceptor degeneration is coupled with structural defects in the RPE as well (4 mo).

Fig. 5.

PrphRd2/+ mice develop RPE abnormalities by 4 mo. A: representative photomicrographs of 2 and 4 mo old Prph+/+ and PrphRd2/+ retina/RPE sections. Layers present are identified. RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; OS, outer segment layer; IS, inner segment layer. Images were taken with a ×100 objective; scale bar = 20 μm. Arrows indicate swollen, hypertrophic RPE cells and dimpled arrowheads specify vacuoles. B: thickness of the RPE cell layer was measured in both central and peripheral regions of the retina at 4 mo. C: the total number of hypertrophic RPE cells per section at 4 mo was counted.

Light-evoked responses of the RPE are reduced in PrphRd2/+ mice

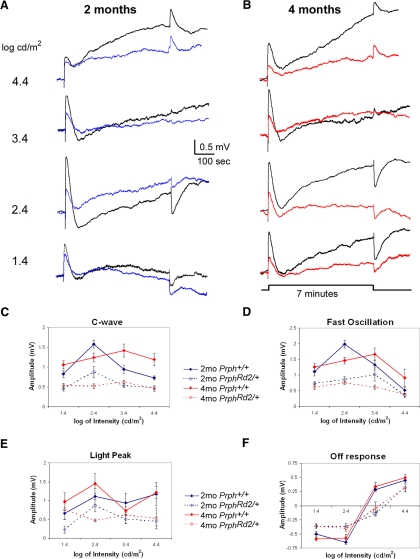

Figure 6 presents averaged responses obtained from Prph+/+ mice (black tracings) and PrphRd2/+ mice at 2 mo (Fig. 6A, blue tracings) and 4 mo (Fig. 6B, red tracings) for each stimulus intensity presented. At both ages, all dc-ERG components were present but reduced in PrphRd2/+ mice compared with those in Prph+/+ littermates. Figure 6, C–F illustrates intensity–response functions for each dc-ERG component. At 2 mo, the amplitude of the PrphRd2/+ c-wave was about 50% that of Prph+/+, a factor that was consistent across all stimulus intensities (Fig. 6C). A similar relationship was seen at 4 mo, with a further amplitude decrease. The changes noted in the FO were more complex. Although overall amplitude was decreased, at 2 mo there was an intensity-dependent shift to the right, indicating that a greater light intensity is required to elicit the same amplitude response as in Prph+/+ mice. At 4 mo, the shift was to the left (Fig. 6D). At both ages examined, the LP component was reduced in amplitude at all stimulus intensities. At 4 mo, however, the amplitude of the LP was no longer modulated by stimulus intensity and, instead, was relatively stable at 0.5—0.75 mV (Fig. 6E). Finally, the amplitude of the OR was attenuated at all light intensities. In addition, the intensity at which the OR reverses polarity was shifted to the right in PrphRd2/+ compared with that in Prph+/+ mice (Fig. 6F). The magnitude of this shift was similar at 2 and 4 mo of age and to the shift of the slow PIII intensity–response function (Table 2). Although differences in ocular pigmentation may induce a similar shift (Wu et al. 2004b), all mice studied here were littermates and similarly pigmented. Therefore we attribute the shift of the OR intensity–response function in PrphRd2/+ mice to a photoreceptor degeneration-associated decreased input to the OR generators.

Fig. 6.

PrphRd2/+ mice exhibit progressive reductions in dc-ERG components. dc-ERG recordings were performed on Prph+/+ and PrphRd2/+ mice at 2 (A) and 4 (B) mo of age in response to a 7-min stimulus at a series of intensities (1.4–4.4 log cd/m2). The averaged Prph+/+ waveforms are shown in black (n = 4–14 at 2 mo; n = 5–11 for 4 mo) and the averaged PrphRd2/+ waveforms are in blue (n = 5–7, 2 mo) and red (n = 4–6, 4 mo). C–F: the amplitude of each dc-ERG component was measured and graphed as a function of stimulus intensity at both time points.

RPE function is conserved despite reduced rod photoreceptor input

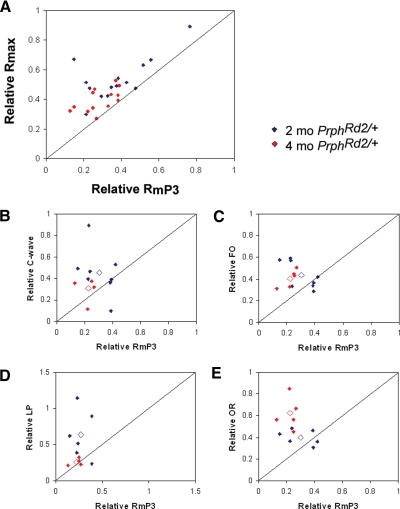

The nonneuronal light-evoked responses, recorded as the dc-ERG and slow PIII, are generated secondary to rod photoreceptor activity. To assess how these components are altered following photoreceptor degeneration in PrphRd2/+ mice, we compared the relative changes in dc-ERG components and slow PIII to those of the a-wave. In Fig. 7, A–E, the diagonal lines indicate where the two measurements are reduced by similar factors. If the slow PIII/dc-ERG component is reduced to a greater or lesser extent than the a-wave, points will fall below or above the diagonal line, respectively. Figure 7 plots the amplitude of Rmax (Fig. 7A) and of each dc-ERG component (Fig. 7, B–E) as a function of a-wave maximum amplitude (RmP3), with all measures expressed as a proportion of the corresponding Prph+/+ responses. To determine the relationship between the photoreceptor response and the Müller cell response, we plotted relative Rmax as a function of relative RmP3 at 2 (n = 12; blue symbols) and 4 (n = 15; red symbols) mo of age. Our data reveal that slow PIII is conserved relative to the photoreceptor response, given that all points fall above the line (Fig. 7A). A similar result was obtained for each dc-ERG component (Fig. 7, B–E). Despite the overall conservation of the dc-ERG responses, the components were affected differently as the mice aged. Both the c-wave and LP were affected to a greater extent at 4 mo than at 2 mo of age, suggesting that the RPE was less resilient to the decline in a-wave amplitude. These findings could reflect the increasing age of the mice, the further loss in photoreceptor activity, or the RPE damage found at this later age. The FO was affected to the same extent at both time points and the OR was spared to a greater extent at 4 mo than at 2 mo. The greater conservation of the OR at 4 mo suggests that the maximum impact of the PrphRd2/+ mutation on this response component was achieved by 2 mo. Collectively, these data indicate that the amplitude of ERG components generated by Müller and RPE cells are retained to a greater extent than predicted by a-wave amplitude.

Fig. 7.

Amplitudes of nonneuronal light-evoked responses are spared compared with a-wave amplitudes. A: relative changes in slow PIII amplitude as a function of RmP3. Each point indicates data obtained from an individual mouse plotted relative to the average control response. The diagonal line indicates an equivalent reduction in the a-wave and slow PIII response. B–E: the relative amplitude of each dc-ERG component was graphed as a function of relative RmP3 in response to a 24 cd s/m2 stimulus. Relative component amplitudes at 2 mo are represented by blue diamonds and relative amplitudes at 4 mo are represented by red diamonds. The average relative amplitude for each time point is represented by an open diamond. The diagonal line represents an equivalent reduction in RmP3 and the dc-ERG component. FO, fast oscillation; LP, light peak; OR, off response.

DISCUSSION

Light-evoked rod photoreceptor responses induce the generation of a series of electrical potentials by nonneuronal cell types. These responses can be recorded at the corneal surface as components of the ERG. The RPE generates four discernable potentials (c-wave, FO, LP, OR), whereas slow PIII reflects activity of retinal Müller cells. These response components are readily recorded from mice and can be used to characterize functional changes in mouse mutants involving genes expressed in Müller or RPE cells. However, the interpretation of any abnormality in these responses is complicated by the possibility that a mouse mutant may also develop rod photoreceptor degeneration or dysfunction, which will alter the amplitude and/or timing of the nonneuronal response. In the present study, we have established a basis for interpreting functional changes in mutant mouse models. We used the PrphRd2/+ mouse because this model of photoreceptor degeneration has been extensively characterized (Arikawa et al. 1992; Cheng et al. 1997; Hawkins et al. 1985; Jansen and Sanyal 1984; Sanyal and Hawkins 1989) and because peripherin/rds is thought to be restricted to rod OSs and not to RPE or Müller cells. We confirmed this localization using immunohistochemistry and demonstrated the exclusive localization of peripherin/rds to rod outer segments.

At 2 mo of age, a-waves of PrphRd2/+ mice were reduced by roughly 50%. A similar reduction was found in slow PIII and all dc-ERG components, although there was a general tendency for all components to be preserved above the level predicted by our a-wave and anatomical analyses. This “sparing” was seen at both 2 and 4 mo of age. There is no doubt that the dc-ERG components and slow PIII are initiated by rod photoreceptor activity. However, several of these components are known to be evoked by changes in [K+]. As a consequence, the disrupted architecture of the PrphRd2/+ subretinal space (SRS) might contribute to their relative preservation. For example, if the SRS were significantly smaller in PrphRd2/+ than that in Prph+/+ mice, an effective change in [K+] could be induced despite a decrease in photoreceptor number and outer segment length.

In addition to demonstrating that RPE and Müller cell function can be characterized in mouse models of photoreceptor degeneration, our results begin to define the relationship between rod photoreceptor degeneration and the electrical responses induced in nonneuronal cell types by photoreceptor activity. Although a number of mouse models involving genes expressed in Müller or RPE cells do not develop rod photoreceptor degeneration (Edwards et al. 2010; Marmorstein et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2004a,b, 2006, 2007), photoreceptor degeneration is observed in others (e.g., Duncan et al. 2003; Won et al. 2008). In these latter models, our results indicate that a reduction in Müller or RPE cell response amplitude beyond that seen at the level of the a-wave would be required to provide strong evidence of Müller or RPE cell-specific dysfunction.

It is not clear why Müller and RPE cell responses are spared in PrphRd2/+ mice. However, it has been reported that disorders that include severe RPE abnormalities (such as rubella retinopathy and diffuse drusen) are not associated with changes in RPE electrophysiology, as evidenced by normal or mildly affected electrooculogram and nonphotic responses (Gupta and Marmor 1994; Marmor 1991). Each dc-ERG component reflects the activity of ion channels that undoubtedly play many roles in maintaining retinal homeostasis. Although several ion channels (e.g., Kir4.1, Clcn2) have been implicated in the generation of the dc-ERG components studied here, it is not yet possible to explain the generation of a particular ERG component in terms of the activity of a specific ion channel(s). As the identification of additional ion channels involved in the generation of each component continues, it will be interesting to determine whether their density and/or location are altered in the PrphRd2/+ retina, which may contribute to the pattern of results we report. In this regard, Takeuchi et al. (2008) demonstrated that systemic administration of the calcium channel blocker, nilvadipine, to PrphRd2/+ mice (with a wildtype Nyxnob background) restores a- and b-wave amplitudes. Electron microscopy demonstrated that the treatment was associated with a partial restoration of photoreceptor OS disc arrays (Takeuchi et al. 2008). It would be interesting to analyze RPE function in these mice and to determine the relative impact of nilvadipine on the a-wave and dc-ERG components.

Slow PIII is known to reflect a cornea-negative potential generated by Müller cells (Kofuji et al. 2000; Wu et al. 2004a), which is normally masked by the larger amplitude and opposite polarity b-wave component. Slow PIII can be unmasked pharmacologically, using glutamate agonists that block b-wave generation (Malchow and Yazulla 1988; Oakley and Green 1976; Steinberg and Miller 1973; Witkovsky et al. 1975), but these agents have a short effective period (Smith et al. 1989), may increase excitotoxic photoreceptor degeneration (Olney 1982), and have not been used over a timeframe comparable to that examined here. In the present study, we used a genetic approach to isolate slow PIII. For mouse-based studies focused on the outer retina, crossing the mutation of interest to Nyxnob, or another mouse model that lacks the ERG b-wave such as Grm6nob3 (Maddox et al. 2008; Masu et al. 1995) or Trpm1−/− (Morgans et al. 2009), will allow slow PIII to be measured. In this study, we used Nyxnob to unmask slow PIII and were able to demonstrate that it was relatively conserved compared with a-wave amplitude in PrphRd2/+ mutants. Because slow PIII is generated by Kir4.1 activity (Kofuji et al. 2000), a potential explanation for its modest reduction involves up-regulation of Kir4.1 in Müller cells. However, Iandiev et al. (2006) reported that Kir4.1 levels are not altered in PrphRd2/+ mice, despite the Müller cell hypertrophy seen in this model (Ekstrom et al. 1988). Therefore further investigation into the mechanism of slow PIII action in the face of photoreceptor degeneration is warranted.

Proper RPE function is indispensable for photoreceptor health and retinal homeostasis. As such, mutations in genes expressed in the RPE underlie a wide range of human maculopathies and retinal dystrophies. Electrophysiological studies of mouse models for these genes have historically been restricted to protocols that focus on the functional properties of rod and cone photoreceptors and inner retinal neurons. The data presented here demonstrate the ability to measure and meaningfully analyze RPE physiology and provide a useful diagnostic tool for mouse models of these inherited retinal disorders. By demonstrating that RPE function is retained at fairly advanced disease levels and by defining how the response properties of the dc-ERG change with photoreceptor degeneration, it is hoped that the functional assays used here will be more broadly applied, especially to mouse models involving genes expressed in the RPE.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Veterans Administration Medical Research Service, Foundation Fighting Blindness Center Grant, Research to Prevent Blindness, and National Eye Institute Grant R24-EY-15638.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank V. Bonilha and Y. Li for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Arikawa et al., 1992.Arikawa K, Molday LL, Molday RS, Williams DS. Localization of peripherin/rds in the disk membranes of cone and rod photoreceptors: relationship to disk membrane morphogenesis and retinal degeneration. J Cell Biol 116: 659–667, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball et al., 2003.Ball SL, Pardue MT, McCall MA, Gregg RG, Peachey NS. Immunohistochemical analysis of the outer plexiform layer in the nob mouse shows no abnormalities. Vis Neurosci 20: 267–272, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch et al., 1997.Birch DG, Travis GH, Locke KG, Hood DC. Rod ERGs in mice and humans with putative null mutations in the RDS gene. In: Vision Science and Its Applications (OSA Technical Digest Series). Washington, DC: Optical Society of America, 1997, vol. 1, p. 262–265 [Google Scholar]

- Bok, 1993.Bok D. The retinal pigment epithelium: a versatile partner in vision. J Cell Sci Suppl 17: 189–195, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha et al., 2006.Bonilha VL, Rayborn ME, Saotome I, McClatchey AI, Hollyfield JG. Microvilli defects in retinas of ezrin knockout mice. Exp Eye Res 82: 720–729, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell and Rosenstein, 1996.Chappell RL, Rosenstein FJ. Pharmacology of the skate electroretinogram indicates independent ON and OFF bipolar cell pathways. J Gen Physiol 107: 535–544, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng et al., 1997.Cheng T, Peachey NS, Li S, Goto Y, Cao Y, Naash MI. The effect of peripherin/rds haploinsufficiency on rod and cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci 17: 8118–8128, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawis and Niemeyer, 1986.Dawis SM, Niemeyer G. Dopamine influences the light peak in the perfused mammalian eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 27: 330–335, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan et al., 2003.Duncan JL, LaVail MM, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, Yang H, Trautmann N, Chappelow AV, Feng W, Earp HS, Matsushima GK, Vollrath D. An RCS-like retinal dystrophy phenotype in mer knockout mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 826–838, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards et al., 2010.Edwards MM, Marín de Evsikova C, Collin GB, Gifford E, Wu J, Hicks WL, Whiting C, Varvel NH, Maphis N, Lamb BT, Naggert JK, Nishina PM, Peachey NS. Photoreceptor degeneration, azoospermia, leukoencephalopathy, and abnormal retinal pigment epithelial cell function in mice expressing an early stop mutation in CLCN2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51: 3264–3272, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom et al., 1988.Ekstrom P, Sanyal S, Narfstrom K, Chader GJ, van Veen T. Accumulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein in Muller radial glia during retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 29: 1363–1371, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii et al., 1992.Fujii S, Gallemore RP, Hughes BA, Steinberg RH. Direct evidence for a basolateral membrane Cl− conductance in toad retinal pigment epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 262: C374–C383, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore et al., 1988.Gallemore RP, Griff ER, Steinberg RH. Evidence in support of a photoreceptoral origin for the “light peak substance.” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 29: 566–571, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore and Steinberg, 1989.Gallemore RP, Steinberg RH. Effects of DIDS on the chick retinal pigment epithelium. II. Mechanism of the light peak and other responses originating at the basal membrane. J Neurosci 9: 1977–1984, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore and Steinberg, 1990.Gallemore RP, Steinberg RH. Effects of dopamine on the chick retinal pigment epithelium. Membrane potentials and light-evoked responses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 31: 67–80, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore and Steinberg, 1993.Gallemore RP, Steinberg RH. Light-evoked modulation of basolateral membrane Cl− conductance in chick retinal pigment epithelium: the light peak and fast oscillation. J Neurophysiol 70: 1669–1680, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granit, 1933.Granit R. The components of the retinal action potential in mammals and their relation to the discharge in the optic nerve. J Physiol 77: 207–239, 1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg et al., 2007.Gregg RG, Kamermans M, Klooster J, Lukasiewicz PD, Peachey NS, Vessey KA, McCall MA. Nyctalopin expression in retinal bipolar cells restores visual function in a mouse model of complete X-linked congenital stationary night blindness. J Neurophysiol 98: 3023–3033, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griff and Steinberg, 1984.Griff ER, Steinberg RH. Changes in apical [K+] produce delayed basal membrane responses of the retinal pigment epithelium in the gecko. J Gen Physiol 83: 193–211, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta and Marmor, 1994.Gupta LY, Marmor MF. Sequential recording of photic and nonphotic electro-oculogram responses in patients with extensive extramacular drusen. Doc Ophthalmol 88: 49–55, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins et al., 1985.Hawkins RK, Jansen HG, Sanyal S. Development and degeneration of retina in rds mutant mice: photoreceptor abnormalities in the heterozygotes. Exp Eye Res 41: 701–720, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetling and Pepperberg, 1999.Hetling JR, Pepperberg DR. Sensitivity and kinetics of mouse rod flash responses determined in vivo from paired-flash electroretinograms. J Physiol 516: 593–609, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood and Birch, 1994.Hood DC, Birch DG. Rod phototransduction in retinitis pigmentosa: estimation and interpretation of parameters derived from the rod a-wave. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 35: 2948–2961, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iandiev et al., 2006.Iandiev I, Biedermann B, Bringmann A, Reichel MB, Reichenbach A, Pannicke T. Atypical gliosis in Muller cells of the slowly degenerating rds mutant mouse retina. Exp Eye Res 82: 449–457, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen and Sanyal, 1984.Jansen HG, Sanyal S. Development and degeneration of retina in rds mutant mice: electron microscopy. J Comp Neurol 224: 71–84, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph and Miller, 1992.Joseph DP, Miller SS. Alpha-1-adrenergic modulation of K and Cl transport in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J Gen Physiol 99: 263–290, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji et al., 2000.Kofuji P, Ceelen P, Zahs KR, Surbeck LW, Lester HA, Newman EA. Genetic inactivation of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Kir4.1 subunit) in mice: phenotypic impact in retina. J Neurosci 20: 5733–5740, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb and Pugh, 1992.Lamb TD, Pugh EN., Jr A quantitative account of the activation steps involved in phototransduction in amphibian photoreceptors. J Physiol 449: 719–758, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsenmeier and Steinberg, 1982.Linsenmeier RA, Steinberg RH. Origin and sensitivity of the light peak in the intact cat eye. J Physiol 331: 653–673, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox et al., 2008.Maddox DM, Vessey KA, Yarbrough GL, Invergo BM, Cantrell DR, Inayat S, Balannik V, Hicks WL, Hawes NL, Byers S, Smith RS, Hurd R, Howell D, Gregg RG, Chang B, Naggert JK, Troy JB, Pinto LH, Nishina PM, McCall MA. Allelic variance between GRM6 mutants, Grm6nob3 and Grm6nob4 results in differences in retinal ganglion cell visual responses. J Physiol 586: 4409–4424, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchow and Yazulla, 1988.Malchow RP, Yazulla S. Light adaptation of rod and cone luminosity horizontal cells of the retina of the goldfish. Brain Res 443: 222–230, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlhens et al., 1997.Marlhens F, Bareil C, Griffoin JM, Zrenner E, Amalric P, Eliaou C, Liu SY, Harris E, Redmond TM, Arnaud B, Claustres M, Hamel CP. Mutations in RPE65 cause Leber's congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet 17: 139–141, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmor, 1991.Marmor MF. Clinical electrophysiology of the retinal pigment epithelium. Doc Ophthalmol 76: 301–313, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein, 2001.Marmorstein AD. The polarity of the retinal pigment epithelium. Traffic 2: 867–872, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein et al., 2002.Marmorstein LY, Munier FL, Arsenijevic Y, Schorderet DF, McLaughlin PJ, Chung D, Traboulsi E, Marmorstein AD. Aberrant accumulation of EFEMP1 underlies drusen formation in Malattia Leventinese and age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 13067–13072, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein et al., 2006.Marmorstein LY, Wu J, McLaughlin P, Yocom J, Karl MO, Neussert R, Wimmers S, Stanton JB, Gregg RG, Strauss O, Peachey NS, Marmorstein AD. The light peak of the electroretinogram is dependent on voltage-gated calcium channels and antagonized by bestrophin (best-1). J Gen Physiol 127: 577–589, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masu et al., 1995.Masu M, Iwakabe H, Tagawa Y, Miyoshi T, Yamashita M, Fukuda Y, et al. Specific deficit of the ON response in visual transmission by targeted disruption of the mGluR6 gene. Cell 80: 757–765, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maw et al., 1997.Maw MA, Kennedy B, Knight A, Bridges R, Roth KE, Mani EJ, Mukkadan JK, Nancarrow D, Crabb JW, Denton MJ. Mutation of the gene encoding cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet 17: 198–200, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nao-i et al., 1989.Nao-i N, Nilsson SE, Gallemore RP, Steinberg RH. Effects of melatonin on the chick retinal pigment epithelium: membrane potentials and light-evoked responses. Exp Eye Res 49: 573–589, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgans et al., 2009.Morgans CW, Zhang J, Jeffrey BG, Nelson SM, Burke NS, Duvoisin RM, Brown RL. TRPM1 is required for the depolarizing light response in retinal ON-bipolar cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 19174–19178, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley and Green, 1976.Oakley B, 2nd, Green DG. Correlation of light-induced changes in retinal extracellular potassium concentration with c-wave of the electroretinogram. J Neurophysiol 39: 1117–1133, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney, 1982.Olney JW. The toxic effects of glutamate and related compounds in the retina and the brain. Retina 2: 341–359, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardue et al., 1998.Pardue MT, McCall MA, LaVail MM, Gregg RG, Peachey NS. A naturally occurring mouse model of X-linked congenital stationary night blindness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39: 2443–2449, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn and Hagins, 1969.Penn RD, Hagins WA. Signal transmission along retinal rods and the origin of the electroretinographic a-wave. Nature 223: 201–204, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrukhin et al., 1998.Petrukhin K, Koisti MJ, Bakall B, Li W, Xie G, Marknell T, Sandgren O, Forsman K, Holmgren G, Andreasson S, Vujic M, Bergen AA, McGarty-Dugan V, Figueroa D, Austin CP, Metzker ML, Caskey CT, Wadelius C. Identification of the gene responsible for Best macular dystrophy. Nat Genet 19: 241–247, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh and Lamb, 1993.Pugh EN, Jr, Lamb TD. Amplification and kinetics of the activation steps in phototransduction. Biochim Biophys Acta 1141: 111–149, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn et al., 2001.Quinn RH, Quong JN, Miller SS. Adrenergic receptor activated ion transport in human fetal retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42: 255–264, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal and Hawkins, 1989.Sanyal S, Hawkins RK. Development and degeneration of retina in rds mutant mice: altered disc shedding pattern in the heterozygotes and its relation to ocular pigmentation. Curr Eye Res 8: 1093–1101, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt and Steinberg, 1971.Schmidt R, Steinberg RH. Rod-dependent intracellular responses to light recorded from the pigment epithelium of the cat retina. J Physiol 217: 71–91, 1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith et al., 1989.Smith EL, 3rd, Harwerth RS, Crawford ML, Duncan GC. Contribution of the retinal ON channels to scotopic and photopic spectral sensitivity. Vis Neurosci 3: 225–239, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, 1985.Steinberg RH. Interactions between the retinal pigment epithelium and the neural retina. Doc Ophthalmol 60: 327–346, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg et al., 1985.Steinberg RH, Linsenmeier RA, Griff ER. Retinal pigment epithelial cell contributions to the electrooculogram. Prog Retinal Res 4: 33–66, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg and Miller, 1973.Steinberg RH, Miller S. Aspects of electrolyte transport in frog pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res 16: 365–372, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg et al., 1970.Steinberg RH, Schmidt R, Brown KT. Intracellular responses to light from cat pigment epithelium: origin of the electroretinogram c-wave. Nature 227: 728–730, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockton and Slaughter, 1989.Stockton RA, Slaughter MM. B-wave of the electroretinogram. A reflection of ON-bipolar cell activity. J Gen Physiol 93: 101–122, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone et al., 1999.Stone EM, Lotery AJ, Munier FL, Héon E, Piguet B, Guymer RH, Vandenburgh K, Cousin P, Nishimura D, Swiderski RE, Silvestri G, Mackey DA, Hageman GS, Bird AC, Sheffield VC, Schorderet DF. A single EFEMP1 mutation associated with both Malattia Leventinese and Doyne honeycomb retinal dystrophy. Nat Genet 22: 199–202, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, 2005.Strauss O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol Rev 85: 845–881, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi et al., 2008.Takeuchi K, Nakazawa M, Mizukoshi S. Systemic administration of nilvadipine delays photoreceptor degeneration of heterozygous retinal degeneration slow (rds) mouse. Exp Eye Res 86: 60–69, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis et al., 1989.Travis GH, Brennan MB, Danielson PE, Kozak CA, Sutcliffe JG. Identification of a photoreceptor-specific mRNA encoded by the gene responsible for retinal degeneration slow (rds). Nature 338: 70–73, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber et al., 1994.Weber BH, Vogt G, Pruett RC, Stohr H, Felbor U. Mutations in the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP3) in patients with Sorsby's fundus dystrophy. Nat Genet 8: 352–356, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky et al., 1975.Witkovsky P, Dudek FE, Ripps H. Slow PIII component of the carp electroretinogram. J Gen Physiol 65: 119–134, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won et al., 2008.Won J, Smith RS, Peachey NS, Wu J, Hicks WL, Naggert JK, Nishina PM. Membrane frizzled-related protein is necessary for the normal development and maintenance of photoreceptor outer segments. Vis Neurosci 25: 563–574, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al., 2004a.Wu J, Marmorstein AD, Kofuji P, Peachey NS. Contribution of Kir4.1 to the mouse electroretinogram. Mol Vis 10: 650–654, 2004a [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al., 2006.Wu J, Marmorstein AD, Peachey NS. Functional abnormalities in the retinal pigment epithelium of CFTR mutant mice. Exp Eye Res 83: 424–428, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al., 2007.Wu J, Marmorstein AD, Striessnig J, Peachey NS. Voltage-dependent calcium channel CaV1.3 subunits regulate the light peak of the electroretinogram. J Neurophysiol 97: 3731–3735, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al., 2004b.Wu J, Peachey NS, Marmorstein AD. Light-evoked responses of the mouse retinal pigment epithelium. J Neurophysiol 91: 1134–1142, 2004b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyszecki and Stiles, 1980.Wyszecki G, Stiles WS. High-level trichromatic color matching and the pigment-bleaching hypothesis. Vision Res 20: 23–37, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]