Abstract

Purpose: This longitudinal study examines the association between physical function decline and the risk of elder self-neglect in a community-dwelling population. Design and Methods: Of the 5,570 participants in the Chicago Health Aging Project, 1,068 were reported to social services agency for suspected elder self-neglect from 1993 to 2005. The primary predictor was objectively assessed physical function using decline in physical performance testing. Secondary predictors were assessed using the decline in self-reported Katz, Nagi, and Rosow–Breslau scales. Outcome of interest was elder self-neglect. Logistic and linear regression models were used to assess these associations. Results: After adjusting for confounding factors, every 1-point decline in physical performance testing was associated with increased risk of reported elder self-neglect (odds ratio [OR], 1.05, confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.07, p < .001). Decline in Katz (OR, 1.05, CI, 1.00–1.10, p < .05) and decline in Rosow–Breslau (OR, 1.19, CI, 1.11–1.27, p < .001) were associated with increased risk of reported elder self-neglect. Decline in physical performance testing (standardized parameter estimate [PE]: 0.19, SE: 0.06, p = .002), Katz (PE: 0.65, SE: 0.14, p < .001), Nagi (PE: 0.48, SE: 0.14, p < .001), and Rosow–Breslau (PE: 0.57, SE: 0.21, p = .006) scales were associated with increased risk of greater self-neglect severity. Implications: Decline in physical function was associated with increased risk of reported elder self-neglect and greater self-neglect severity in this community-dwelling population.

Keywords: Self-neglect, Physical function decline, Longitudinal study

Elder self-neglect is a common and important public health issue across all sociodemographic socioeconomic strata and across all locale in the United States. Elder self-neglect has great relevance not only to health care professional and social services agency but also to public health professionals, community organizations, and other relevant disciplines. Evidence suggests that there are about 1.2 million cases of elder self-neglect in the United States (National Center on Elder Abuse, 1998). A recent study suggests that elder self-neglect reported to social services agency is associated with increased risk of mortality, and there is a gradient relation between greater self-neglect severity and higher risk for mortality (Dong, Simon, Mendes de Leon, et al., 2009). Moreover, evidence indicates that reports of elder self-neglect to social services agencies are on the rise (Teaster, 2002). As our aging population increases rapidly, elder self-neglect will likely become an even more pervasive public health issue.

The National Centers on Elder Abuse defines elder self-neglect as “ … as the behavior of an elderly person that threatens his/her own health and safety. Self-neglect generally manifests itself in an older person as a refusal or failure to provide himself/herself with adequate food, water, clothing, shelter, personal hygiene, medication (when indicated), and safety precautions” (National Center on Elder Abuse Website, 2006). There have been a number of conceptual frameworks postulated for the syndrome of elder self-neglect (Choi, Kim, & Asseff, 2009; Dyer, Goodwin, Pickens-Pace, Burnett, & Kelly, 2007; Iris, Ridings, & Conrad, 2009; Orem, 1991; Pavlou & Lachs, 2006).

This study follows the conceptual framework derived by Dyer and colleagues (2007) from a large cohort of elder self-neglect cases reported to social services agencies. This conceptual framework represents a comprehensive synthesis of elder self-neglect and is widely used by public health workers, clinicians, and researchers to better understand the issues of elder self-neglect (Dong, Mendes de Leon, & Evans, 2009; Dyer et al., 2008; McDermott, 2008; Naik, Burnett, Pickens-Pace, & Dyer, 2008; Paveza, Vandeweerd, & Laumann, 2008; Pickens et al., 2007). In this conceptual framework, the common elements include medical comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, etc.), depression, cognitive impairment, executive dysfunction, physical function impairment, lack of social network, and social support. The central hypothesis of this framework suggests that increased burden of medical comorbidities compounded by cognitive impairment and depression may lead to executive dysfunction which in turn could worsen the levels of physical function. In this model, impairment with essential activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL represent the central event associated with worsening vulnerability in the syndrome of elder self-neglect. In addition, physical function impairment combined with lack of social network and inadequate support services magnify the lack of ability for self-protection, leading to the syndrome of elder self-neglect.

Physical function impairment has been associated with substantial morbidity and mortality (Johnson, 2000; Olsen & Jeune, 1980; Wallman et al., 2006). However, our current understanding of the relations between physical function and elder self-neglect has been limited. Prior cross-sectional research found that elder self-neglect was associated with self-reported physical function impairments (Cornwall, 1981; Longres, 1995; Nelson & Farberow, 1980; O’Rawe, 1982; Orrell, Sahakian, & Bergmann, 1989; Pickens et al., 2007). Direct performance testing of physical function may be more accurate, but we found only three cross-sectional studies that have described the lower levels of physical performance testing associated with elder self-neglect (Dong, Mendes de Leon, et al., 2009; Dyer et al., 2007; Naik et al., 2008). Moreover, current knowledge of the temporal relations of physical function and elder self-neglect in a representative population remains limited. This information is critical in ascertaining more precise understanding of risk factors associated with elder self-neglect in order to inform future prevention and intervention strategies.

Furthermore, elder self-neglect, like many other geriatric syndromes, manifests along a continuum of severity rather than in discrete categories (Dong & Gorbien, 2005), but our understanding of elder self-neglect is mainly from the most severe cases and from a dichotomous categorization of subjects as “self-neglect” or “no self-neglect.” Improved understand of elder self-neglect and its severity is of enormous public health importance as frontline social services agency deal with the issues of elder self-neglect across the continuum. In this longitudinal study, we aim to expand the prior literature in two ways by examining (a) the relationship between decline in physical function and the risk of self-neglect and (b) the relationship between decline in physical function and the risk of greater self-neglect severity within the context of a prospective population-based cohort. We hypothesize that decline in physical function is associated with increased risk of reported and confirmed elder self-neglect and that there is a linear relation between decline in physical function with greater self-neglect severity.

Design and Methods

Setting

The Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP) is a study of risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline that began in 1993. Its participants are residents aged 65 years and older from three adjacent neighborhoods on the south side of Chicago: Morgan Park, Washington Heights, and Beverly. More details of the study design of CHAP have been published previously (Bienias, Beckett, Bennett, Wilson, & Evans, 2003; Evans et al., 2003).

Of the 7,813 age-eligible residents identified through a complete census of these areas, 6,158 (78.9%) were enrolled in CHAP and administered a baseline interview. Data collection occurred in cycles, each lasting 3 years, with each cycle ending as the succeeding cycle began. Each cycle consisted of in-person interviews of participants in their own homes. As of the third cycle in 2000, CHAP started to enroll participants in successive age cohorts, that is, of community residents who had turned 65 years since the inception of the study. The same pattern of data collection was used for members of these “successive age cohorts,” and their data were combined with the original cohort in analyses.

Participants

In the current study, participants include all those who were enrolled between 1993 and 2005 and who had repeated physical function measures (N = 5,570) prior to the report of elder self-neglect to social services agency. From this cohort, we identified a subset of participants (n = 1,068), who were reported to social services agency for suspected elder self-neglect. Suspected cases of elder self-neglect were reported by friends, neighbors, family, social workers, city workers, health care professionals, and others. The reports were usually triggered by concerns for the health and safety of the older adult in their home environment, which would initiate a number of different services to help the affected person. CHAP and social services data were matched using variables of date of birth, sex, race, home telephone number, and exact home address. Our data management and programming team performed data set matching twice to ensure accuracy. All CHAP participants received structured standardized in-person interviews that included assessment of health history and detailed assessment of disability and physical function. Written informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rush University Medical Center.

Reporting and Assessment of Self-neglect

Elder self-neglect in this study was based on all suspected cases reported to social services agency. When a case was reported, case workers performed a home assessment, which assessed the deficits in the domains of personal hygiene and grooming, household and environmental hazards, health needs, and overall home safety concerns. The level of severity was rated by case workers based on their concerns for the client’s personal health and safety issues. The maximum cumulative score was 45, with a higher score indicating greater severity. Confirmed elder self-neglect in this study was defined as anyone with a score of 1 or greater (n = 862). The elder self-neglect severity referred to the scores 1–45, with higher score indicate greater levels of elder self-neglect severity. The detail of this measure has been previously described (Dong, Mendes de Leon, et al., 2009; Dong, Simon, & Evans, 2009; Dong, Wilson, Mendes de Leon, & Evans, 2009). Available information from the social services agency internal report (Illinois Department on Aging, 1989) showed that this measure was tested using the kappa statistic algorithm (Fleiss, 1971), and all variables had interrater reliability coefficients of greater than .70. In addition, the internal consistencies of the items were high with Cronbach’s alpha of .95 (Dong, Simon, & Evans). Both face and content validity were evaluated using qualitative data from case managers and agency administrators. In addition, external validity of the measure was assessed as a continuous variable and was shown to predict higher health care utilization (Illinois Department on Aging) and increased risk of premature mortality (Dong, Simon, Mendes de Leon, et al., 2009).

Assessment of Physical Function

Physical function implies the assessment of specific activities and tasks, and impairment threatens one’s ability to live independently. Physical function was assessed by direct performance testing, which provided a comprehensive assessment of lower extremity function. Physical performance tests have been used to “validate” self-report measures and provide a more objective and detailed assessment of certain abilities (Guralnik et al., 1994). Lower extremity performance tests consisted of measures of tandem stand, timed walk, tandem walk, and ability to rise to a standing position from a chair. The tests requiring walking performance were quantified in terms of both the number of seconds to complete the task. Other tests were measured in terms of the number of trials completed within a specified time period. Most of these performance tests were used in the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly project (Guralnik et al., 1994) and in other large-scale studies of disability. Summary measures of these above tests were created as physical performance test scores (range 0–15). Lower score indicates impairment in these above activities and tasks, which are often needed for independent living and may contribute toward physical disability. Because of their reliance on direct observation of actual performance, the tests possess high face validity and have also been shown to have good internal consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s α = .76; Guralnik et al., 1994) and excellent test–retest reliability (0.88–0.92; Ostir, Volpato, Fried, Chaves, & Guralnik, 2002).

In addition to the performance-based measure of physical function, self-reported physical function was assessed using three well-established measures of ability to perform common daily activities. The first measure used was the Katz index of activities of daily living (Katz ADL), which measures limitations in an individual’s ability to perform basic self-care tasks (Katz & Akpom, 1976). It consists of six items (feeding, dressing, bathing, toileting, transferring, and continence), and an ADL score is created by adding the individual items (range 0–6). Impairment in any of the ADL measures has great clinical relevance and could indicate the older person’s difficulties with basic ADL and reliance on others to provide these assistances. Impairment in all ADL measure would suggest that the older person will require total care by another person unable to engage in any meaning physical activity.

The second measure was an index of mobility based on work by Rosow and Breslau (1966). It is composed of three items measuring the ability to do heavy work around the house (e.g., shoveling snow and washing widows, walls, or floors), walk upstairs and downstairs, and walk half a mile. Adding the individual items yields a summary score with a range from 0 to 3. The third measure used in this study was an index of basic physical activities and is based on work by Nagi (1976). It measures five activities of upper or lower extremity function (e.g., pulling or pushing large objects like living room chair; stooping, crouching, or kneeling; lifting or carrying weights more than 10 lbs, like a heavy bag or groceries; reaching or extending arms above shoulder level; and writing or handling or fingering small objects). Each item is scored according to degree of difficulty on a 5-point scale (0–5). Impairment in any of these mobility and physical activities measures could indicate the older adult’s difficulties with daily housework or out of the house activities. Impairment in all mobility and physical activities measure suggests that the older adults would have total dependence on others with daily housework and out of house activities. The threshold for physical disability from these impairments likely to vary depends on the availability of external help and/or assistive devices to the older adults to perform these activities.

Covariates

Based on the previously mentioned conceptual framework, we selected a number of covariates to examine the relations between physical function decline and elder self-neglect. Demographic variables include age (in years), sex (men or women), race (self-reported: non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White), and education (years of education completed). Cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975); immediate and delayed recall of brief stories in the East Boston Memory Test, which measures episodic memory (Albert et al., 1991); and the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, which measures the domains of perceptual speed and executive function (Smith, 1984). To assess global cognitive function with minimal floor and ceiling artifacts, we constructed a summary measure for global cognition based on all four tests. Individual test scores were summarized by first transforming a person’s score on each individual test to a z-score and then averaging z-scores across tests to yield a composite score for global cognitive function. Information on self-reported medical conditions was collected for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, coronary artery disease, shingles, Parkinson’ disease, hip fracture, cancer, and thyroid disease. Symptoms of depression were measured using a modified version (Kohout, Berkman, Evans, & Cornoni-Huntley, 1993) of the Center for the Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (range 0–10; Radloff, 1977). Social networks were summarized as the total number of children, relatives, and friends seen at least monthly (Cornoni-Huntley, Brock, Ostfeld, Taylor, & Wallace, 1986)

Analytic Approach

Descriptive characteristics were provided for the reported and unreported elder self-neglect groups. Our outcomes of interest were reported self-neglect, confirmed self-neglect, and self-neglect severity. Our predictor of interest was decline in physical function. For change in physical function measures, we summarized the differences in physical function scores (physical performance testing, Katz, Nagi, and Rosow–Breslau), which were uniformly assessed during the CHAP interviews. For subjects with elder self-neglect, we summarized the differences between first available physical function measure and the most immediate physical function measure prior to the reporting of elder self-neglect. For subjects without elder self-neglect, we summarized the differences between the first available physical function measure and the most immediate assessment prior to the end of year 2005 as that was the last available date of self-neglect data.

Logistic regression models were used to analyze the relationship between decline in physical function and risk of elder self-neglect. We used a series of models to consider the relationship between decline in physical function and elder self-neglect, taking into consideration of potential confounders as guided by the conceptual framework. In our core model (Model A), we included age, sex, race, education to estimate the association of decline in physical function, and risk of elder self-neglect outcomes. In addition, we added to the prior model the health-related variables of global cognitive function and common medical comorbidities of hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, shingles, Parkinson’s disease, hip fracture, cancer, thyroid disease, and diabetes (Model B). Finally, models were repeated controlling for additional psychological and social factors of depressive symptomatology and social network (Model C).

We repeated the Models A–C for confirmed elder self-neglect. Lastly, we used linear regression to examine the association between decline in physical function and elder self-neglect severity and repeated Models A–C. Odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), standardized parameter estimates (PE), standard error, and p values were reported for the regression models. Analyses were carried out using SAS, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

There were a total of 5,570 CHAP participants in this study, and 1,068 participants were identified by the social services agency for suspected elder self-neglect. The mean age of the 1,068 participants was 74.0 years (SD 6.3 years), with approximately 66.9% of them being women. A majority of the reported elder self-neglect (86.9%) cases were for Black older adults. The characteristics of older participants with and without reported elder self-neglect are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Elders With Self-neglect and Without Self-neglect in a Community-Dwelling Population

| Self-neglect (n = 1,068) | No self-neglect (n = 4,502) | |

| Age, years, M (SD) | 74.0 (6.3) | 72.5 (6.0) |

| Women, n (%) | 714 (66.9) | 2700 (59.9) |

| Blacks, n (%) | 928 (86.9) | 2655 (58.9) |

| Education, years, M (SD) | 10.9 (3.5) | 12.5 (3.6) |

| Medical conditions, n (SD) | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.9) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 161 (15.1) | 534 (11.9) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 106 (9.9) | 329 (7.3) |

| Cancer, n (%) | 189 (17.7) | 819 (18.2) |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 91 (8.5) | 346 (7.7) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 659 (61.7) | 2369 (52.6) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 252 (23.6) | 710 (15.8) |

| Hip fracture, n (%) | 34 (3.2) | 129 (2.9) |

| Shingles, n (%) | 33 (3.1) | 266 (5.9) |

| Parkinson’s disease, n (%) | 7 (0.7) | 31 (0.7) |

| Global cognitive function, M (SD) | −0.07 (0.77) | 0.27 (0.73) |

| MMSE, M (SD) | 25.4 (4.6) | 26.7 (4.2) |

| CES-D, M (SD) | 1.9 (2.2) | 1.4 (1.8) |

| Social network, M (SD) | 7.2 (6.1) | 8.0 (6.7) |

Note: CES-D = Center for the Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

The mean score for the directly observed physical performance testing was 9.4 (SD 3.6; range 0–15) for participants with reported elder self-neglect and 10.8 (3.3) for those without reported elder self-neglect (Table 2). The mean decline in physical performance testing score was −2.7 (3.9) for those with elder self-neglect and −1.8 (3.8) for those without elder self-neglect. Data for reported physical function measures were detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Physical Function Measures Between Elders With and Without Self-neglect

| Self-neglect (n = 1,068) | No self-neglect (n = 4,502) | |

| Physical performance testing, M (SD) | 9.4 (3.6) | 10.8 (3.3) |

| Physical performance testing change, M (SD) | −2.7 (3.9) | −1.8 (3.8) |

| Katz impairment, M (SD) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.2 (0.8) |

| Katz impairment change, M (SD) | 0.7 (1.6) | 0.5 (1.4) |

| Nagi impairment, M (SD) | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.2) |

| Nagi impairment change, M (SD) | 0.8 (1.7) | 0.6 (1.4) |

| Rosow impairment, M (SD) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.8) |

| Rosow impairment change, M (SD) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.6 (1.0) |

Notes: Physical performance testing, range (0–15). Katz: self-reported activities of daily living, range (0–6). Nagi: self-reported index of physical activity, range (0–5). Rosow–Breslau: self-reported index of mobility, range (0–3).

Decline in Physical Performance Testing and Risk of Elder Self-neglect

To measure the association between declines in physical performance testing and risk of reported elder self-neglect, an initial logistic regression model adjusting for age, sex, race, and education was created with reported elder self-neglect as the outcome (OR, 1.05, 95% CI, 1.03–1.07, p < .001; Table 3, Model A). After adding cognitive function, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cancer, thyroid disease, and myocardial infarction to the model (Model B), the association did not change. In the last model (Model C), after adjusting for psychosocial measures of depressive symptomatology and social network, every 1-point decline in physical performance testing was associated with increased risk of reported elder self-neglect (OR, 1.05, 95% CI, 1.03–1.07, p < .001). For confirmed elder self-neglect, the associations were similar (Table 4).

Table 3.

Decline in Physical Function and Risk of Reported Elder Self-neglect

| Odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence intervals |

||||||

| Physical performance testing |

Katz ADL |

|||||

| Predictors | Model A | Model B | Model C | Model A | Model B | Model C |

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Age | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) |

| Men | 0.78 (0.66–0.91) | 0.78 (0.67–0.92) | 0.79 (0.68–0.93) | 0.77 (0.67–0.89) | 0.79 (0.68–0.91) | 0.79 (0.68–0.92) |

| Black | 5.02 (4.03–6.24) | 4.78 (3.83–5.97) | 4.70 (3.75–5.89) | 4.86 (3.96–5.97) | 4.71 (3.82–5.81) | 4.69 (3.79–5.81) |

| Education | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) |

| Health related | ||||||

| Medical conditions | 1.11 (1.01–1.21) | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) | 1.13 (1.04–1.22) | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) | ||

| Global cognition | 0.88 (0.78–0.99) | 0.87 (0.76–0.99) | 0.89 (0.79–0.99) | 0.86 (0.76–0.97) | ||

| Psychosocial | ||||||

| CES-D | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | ||||

| Social network | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | ||||

| Outcome: reported self-neglect | 1.05 (1.03–1.07)* | 1.05 (1.03–1.07)* | 1.05 (1.03–1.07)* | 1.05 (1.00–1.10)** | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 1.05 (1.00–1.10)** |

| Nagi physical activity |

Rosow–Breslau mobility |

|||||

| Predictors | Model A | Model B | Model C | Model A | Model B | Model C |

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Age | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) |

| Men | 0.76 (0.65–0.88) | 0.77 (0.66–0.89) | 0.78 (0.67–0.91) | 0.78 (0.67–0.91) | 0.79 (0.69–0.93) | 0.80 (0.69–0.94) |

| Black | 4.88 (3.97–5.99) | 4.69 (3.80–5.80) | 4.65 (3.76–5.77) | 4.84 (3.94–5.95) | 4.68 (3.79–5.78) | 4.67 (3.77–5.79) |

| Education | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.95 (0.93–1.97) | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) |

| Health related | ||||||

| Medical conditions | 1.13 (1.04–1.23) | 1.12 (1.03–1.21) | 1.13 (1.04–1.22) | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) | ||

| Global cognition | 0.87 (0.78–0.98) | 0.84 (0.75–0.95) | 0.88 (0.79–0.99) | 0.86 (0.76–1.97) | ||

| Psychosocial | ||||||

| CES-D | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) | ||||

| Social network | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | ||||

| Outcome: reported self-neglect | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 1.05 (0.99–1.09) | 1.18 (1.10–1.26)* | 1.17 (1.09–1.25)* | 1.19 (1.11–1.27)* |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living; CES-D = Center for the Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale.

*p < .001. **p < .05.

Table 4.

Decline in Physical Function and Risk of Confirmed Self-neglect

| Models | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Physical performance testing | A | 1.06 | 1.04–1.09 | <.001 |

| B | 1.06 | 1.04–1.09 | <.001 | |

| C | 1.06 | 1.04–1.09 | <.001 | |

| Katz ADL | A | 1.08 | 1.03–1.13 | .002 |

| B | 1.07 | 1.02–1.13 | .007 | |

| C | 1.08 | 1.03–1.13 | .003 | |

| Nagi index of physical activity | A | 1.06 | 1.01–1.12 | .018 |

| B | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 | .029 | |

| C | 1.07 | 1.02–1.13 | .008 | |

| Rosow–Breslau index of mobility | A | 1.22 | 1.13–1.31 | <.001 |

| B | 1.21 | 1.13–1.30 | <.001 | |

| C | 1.23 | 1.14–1.32 | <.001 |

Notes: Model A: adjusted for age, sex, race, education. Model B: adjusted for A + cognitive function, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cancer, thyroid disease, and coronary artery disease. Model C: adjusted for B + depressive symptomatology and social network. Katz ADL = Katz index of activities of daily living. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Decline in Self-reported Physical Function and Risk of Elder Self-neglect

Decline in self-reported physical function was also associated with increased risk of reported elder self-neglect. For every one increased impairment in Katz ADL (Table 3, Model C), there was significant increased risk of reported elder self-neglect (OR, 1.05, 95% CI, 1.00–1.10, p = .034). For every one increased impairment in Rosow–Breslau, there was also significant increased risk of reported elder self-neglect (OR, 1.19, 95% CI, 1.11–1.27, p < .001). However, the decline in Nagi index of physical activity was not associated with increased risk of elder self-neglect.

Decline in self-reported physical function was also associated with increased risk of confirmed elder self-neglect. Every one increased impairment in Katz ADL (Table 4, Model C) was significantly associated with increased risk of confirmed elder self-neglect (OR, 1.08, 95% CI, 1.03–1.13, p = .003). Every one increased impairment in Nagi was significantly associated with increased risk of confirmed elder self-neglect (OR, 1.07, 95% CI, 1.02–1.12, p = .008). Every one increased impairment in Rosow–Breslau was also associated with increased risk of confirmed elder self-neglect (OR, 1.23, 95% CI, 1.14–1.32, p < .001).

Self-neglect Severity and Self-reported Physical Function

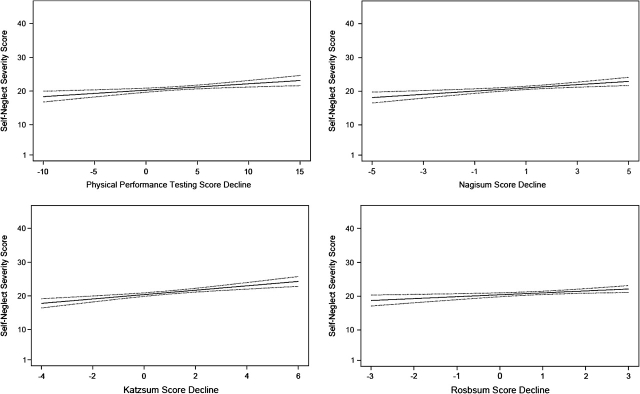

To measure the relations between decline in physical performance testing and greater elder self-neglect severity, an initial linear regression model adjusting for age, sex, race, and education was created with elder self-neglect severity as the outcome (Table 5, Model A). The coefficient representing the association of elder self-neglect severity and physical performance testing was .18 (p = .003), suggesting a statistically significant association between decline in physical performance testing and greater severities of elder self-neglect. After adding global cognitive function and medical comorbidities of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cancer, thyroid disease, and myocardial infarction to the model (Model B), the association did not change. In the last model (Model C), after adjusting for depressive symptomatology and social network, the coefficient changed minimally but remained statistically significant (coefficient = .19, p = .002). Figure 1 graphically represents the greater decline in physical performance testing, the higher the risk of greater self-neglect severity.

Table 5.

Decline in Physical Function and Self-neglect Severity

| Models | Parameter estimates | SE | p Value | |

| Physical performance testing | A | 0.18 | 0.06 | .003 |

| B | 0.18 | 0.06 | .003 | |

| C | 0.19 | 0.06 | .002 | |

| Katz ADL | A | 0.63 | 0.13 | <.001 |

| B | 0.63 | 0.13 | <.001 | |

| C | 0.65 | 0.14 | <.001 | |

| Nagi index of physical activity | A | 0.43 | 0.13 | .001 |

| B | 0.47 | 0.13 | <.001 | |

| C | 0.48 | 0.14 | <.001 | |

| Rosow–Breslau index of mobility | A | 0.46 | 0.20 | .025 |

| B | 0.49 | 0.20 | .014 | |

| C | 0.57 | 0.21 | .006 |

Notes: Self-neglect severity represents a 1-point increase on the scale of 0–45. Model A: adjusted for age, sex, race, and education. Model B: adjusted for A + cognitive function, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cancer, thyroid disease, and coronary artery disease. Model C: adjusted for B + depressive symptomatology and social network. Katz ADL = Katz index of activities of daily living.

Figure 1.

Decline in physical function and self-neglect severity. The association (with 95% confidence intervals) of decline in levels of physical performance testing and higher number of impairments in self-reported physical function measures (Katz, Nagi, and Rosow–Breslau) and greater self-neglect severity.

The decline in self-reported physical function measures (Katz, Nagi and Rosow–Breslau scores) were also associated with greater self-neglect severity. In the fully adjusted model (Table 5, Model C), we found a statistically significant association between the increased impairment in Katz (coefficient = .65, p < .001), Nagi (coefficient = .65, p < .001), and Rosow–Breslau (coefficient = .57, p = .006) scores with increased risk of greater self-neglect severity. Figure 1 shows a graphic presentation of increased number of Katz, Nagi, and Rosow–Breslau impairments with the risk of greater self-neglect severity.

Discussion

In this prospective population-based study of 5,570 older adults from an urban, geographically defined, and socioeconomically diverse community, we found that both decline in physical performance testing and increased impairment in self-reported physical function were associated with increased risk for elder self-neglect. In addition, decline in the earlier mentioned physical function measures was also associated with increased risk of greater self-neglect severity.

Our findings expand the results of other cross-sectional studies of elder self-neglect and physical function. Dyer and colleagues (2007) conducted a cross-sectional chart review of nearly 460 cases of elder self-neglect referred by social services agency and found that 76.3% of the cases had abnormal levels of physical performance testing. In another recent study, Naik and colleagues (2008) examined 100 community subjects reported to social services agency for elder self-neglect and found that impairment in instrumental ADL was significantly associated with elder self-neglect. However, the authors did not find a statistically significant cross-sectional association between impairment in physical performance testing and elder self-neglect (p = .49).

Prior cross-sectional study also suggested the association between lower levels of physical function and greater self-neglect severity. Dong, Mendes de Leon, et al. (2009) found that greater self-neglect severity was associated with lower levels of physical performance testing (coefficient = −.062, p = .001) and higher number of impairment in Katz ADL (coefficient = .024, p = .001), Nagi (coefficient = .024, p = .001), and the Rosow–Breslau (coefficient = .016, p = .001) scales.

Our findings appear to support the conceptual framework by Dyer and colleagues (2007). Our present study specifically tested the central key factor preceding the syndrome of elder self-neglect: decline in physical function. Under Dyer’s framework, medical comorbidities, depression, cognitive impairment, executive dysfunction, and nutritional deficiencies all contribute to impairment in physical function. In our multivariate analyses, we adjusted for these factors, but this adjustment did not significantly alter our study findings. In addition, this conceptual framework considered extrinsic issues, such as sociodemographic characteristics that may potentially exacerbate the lack of social network. In our present study, even after we considered the sociodemographic characteristics and level of social network, decline in physical function remained to be independently associated with elder self-neglect. In addition, our findings further support the framework by Pavlou and Lachs (2006), who proposed to frame elder self-neglect as a geriatric syndrome. The missing centerpiece of their framework was the evidence of relationship between impairment of physical function and elder self-neglect. Although our study provided evidence supporting the aforementioned conceptual frameworks, future longitudinal studies of other risk or protective factors are needed to further validate these frameworks.

We believe that our results contribute to the current understanding of elder self-neglect in four ways. First, this study is a large sample of older adults in a longitudinal population-based study of a geographically defined community that is racially or ethnically and socioeconomically diverse, expanding the generalizability of the study. Second, this present study is the first examination of temporal relations between the decline in physical function and risk of elder self-neglect, which further validates elder self-neglect as an important geriatric syndrome. Improved understanding of these relations is critically informative to future prevention and intervention strategies for elder self-neglect.

Third, prior understanding of elder self-neglect has been mostly based on the dichotomous categorization of elder self-neglect as present or absent, and little was known about the possibility that there was incremental risk along the continuum of elder self-neglect severity. Our study is the first to demonstrate that decline in physical function is associated with significant increased risk for greater self-neglect severity. These findings have important clinical implications for health care professionals and social services agency, including the importance of devising early detection and intervention strategies to deal with mild cases of elder self-neglect in order to prevent and forestall further deteriorations.

Fourth, our study utilized comprehensive measures of physical function, both the observed physical performance testing and the self-reported physical function measures. This approach decreases the potential biases associated with self-reported functional measure and provides more objective and uniform testing of physical performance abilities and further confirms the validity of this relationship between physical function and elder self-neglect.

The precise causal mechanisms between physical function decline and elder self-neglect remain unclear. We considered a series of sociodemographic characteristic, medical comorbidities, cognitive function, depressive symptomatology, and social factors. However, adjustments for these factors did not change the relationship between physical function decline and elder self-neglect. Metabolic abnormalities, nutritional deficiencies, and sarcopenia may be other factors that account for the association between physical function decline and elder self-neglect, but these factors were not considered in this analysis. Social support may be another intermediate factor between decline in physical function and elder self-neglect. However, we do not have measures of social support in our existing data to further elucidate these relations.

Although the proposed study has the strengths of being of a rigorously defined longitudinal population-based cohort and having extensive physical function measures, it also has limitations that should be noted. First, elder self-neglect was not ascertained uniformly for all members of the CHAP population but only for participants referred to the social services agency because someone suspected problems. The measure of elder self-neglect was designed for practical and administrative use within the social services agency, and the nonuniformed data collection could introduce bias into our findings.

Second, it is conceivable that elder self-neglect occurred prior to being reported to social services agency, which could potentially bias our findings. However, availability of 12 years of longitudinal data from 1993 through 2005 may somewhat decrease this potential bias. Nevertheless, future study is needed to uniformly collect data on elder self-neglect to examine the relations of decline in physical function and incident elder self-neglect in representative populations.

Third, although this study examined physical function decline as the predictor of elder self-neglect, it is conceivable that physical function decline is an outcome of elder self-neglect. Our cohort did not have sufficient repeated measures of physical function after the elder self-neglect report to examine these relationships. Fourth, this study could not examine the relation between the decline in physical function and specific indicators or behaviors of elder self-neglect. Prior study by McDermott and colleagues (McDermott, 2008) suggests that the precise understanding of the self-neglect phenotypes could further contribute to a clearer conceptual framework for elder self-neglect. Fifth, there are likely to be additional factors (substance abuse, schizophrenia, personality disorders, social support, etc.) not considered in our analyses, which may account for these findings. However, this study sets the foundation for future study of elder self-neglect to fully examine these causal mechanisms.

Lastly, we did not have measures of Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills (KELS), which further assesses an older adult’s ability to live independently. Future studies are needed to elucidate differential effects of self-reported and directly observed physical function measures used in our study with other physical function measures such as KELS in order to compare the differences in the predictive abilities for elder self-neglect.

Our findings have clinical implications for health care professionals in prevention, detection, and management of elder self-neglect. As the population ages, health care professionals are increasingly being asked to comment on older patient’s functional status within the context of their daily living. Health care professionals should consider screening for elder self-neglect among older patients who report decline in physical function abilities. In addition, health care professionals should be educated on the importance of these potential risk factors, which could be integrated into the routine history taking for older patients in clinical settings. Vigilant monitoring of physical function abilities could help clinicians to detect and prevent elder self-neglect.

Likewise, health care professionals who work with elder self-neglect cases should also be aware of the importance of physical function status in their clinical practice. Especially, geriatricians, public health workers, social workers, and social services agencies who work with elders who self-neglect or who are at risk for self-neglect could be in unique positions to further screen for physical function impairment. In addition, if the health care professionals detect rapid decline in physical function, it would be critical to consider the risk for greater severities of elder self-neglect. Close monitoring and improved understanding of their physical function abilities could help clinicians leverage family members, social workers, health professionals, and public health and community organizations to create an interdisciplinary approach to comprehensively care for those with elder self-neglect.

Our findings also have direct implication for future research, by providing the first longitudinal evidence on decline in physical function as a potential risk factor for elder self-neglect. Future research is needed to explore temporal associations of the racial or ethnic and gender differences in decline in physical function and the risk of elder self-neglect in community-dwelling populations. Future studies are needed to explore the longitudinal association of decline in cognitive function, depressive symptomatology, social support and medical comorbidities, and the risk of elder self-neglect, which could further validate the conceptual framework of Dyer and colleagues (2007). Future studies are needed to examine the role of interventions to improve physical function and to rigorously examine if target interventions can prevent and reduce elder self-neglect in the community.

We conclude that decline in physical function is associated with increased risk for elder self-neglect in this community-dwelling population of older adults. In addition, decline in physical function is associated with increased risk of greater self-neglect severity. Our findings further illustrate the public health importance of the syndrome of elder self-neglect and demonstrate its association with physical function, the cornerstone of health and aging. Future studies should uniformly collect data on elder self-neglect to address the causal mechanisms between change in physical function and specific behaviors of elder self-neglect. Future study is also needed to explore the racial or ethnic and gender differences in the association between decline in physical function and risk of elder self-neglect in the general population.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging grant (R01 AG11101), Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging (K23 AG030944), The Starr Foundation, John A. Hartford Foundation, and The Atlantic Philanthropies.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms. Ann Marie Lane for community development and oversight of project coordination and Ms. Michelle Bos, Ms. Holly Hadden, Mr. Flavio LaMorticella, and Ms. Jennifer Tarpey for coordination of the study. We further thank Todd Beck, Melissa Simon, and Jennifer Weuve, PhD, for statistical programming and George Dombrowski and Melissa Simon for data management support. Drs. XinQi Dong, Melissa Simon, Terry Fulmer, Bharat Rajan, Carlos F. Mendes de Leon, and Denis A. Evans declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA, Taylor JO, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH. Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;57:167–178. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienias JL, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Design of the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP) Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2003;5:349–355. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Kim J, Asseff J. Self-neglect and neglect of vulnerable older adults: Reexamination of etiology. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2009;52:171–187. doi: 10.1080/01634370802609239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornoni-Huntley J, Brock DB, Ostfeld A, Taylor JO, Wallace RB. Established populations for epidemiological studies of the elderly resource data book. 1986. (NIH Publication No. 86-2443). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall JV. Filth, squalor and lice. Self neglect in the elderly. Nursing Mirror. 1981;153:48–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Gorbien M. Decision-making capacity: The core of self-neglect. Journal of Elder Abuse Neglect. 2005;17:19–36. doi: 10.1300/j084v17n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA. Is greater self-neglect severity associated with lower levels of physical function? Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21:596–610. doi: 10.1177/0898264309333323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Simon MA, Evans DA. Cross-sectional study of the characteristics of reported elder self-neglect in a community-dwelling population: Findings from a population-based cohort. Gerontology. 2009 doi: 10.1159/000243164. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Simon M, Mendes de Leon C, Fulmer T, Beck T, Hebert L, et al. Elder self-neglect and abuse and mortality risk in a community-dwelling population. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:517–526. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA. Self-neglect and cognitive function among community-dwelling older persons. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1002/gps.2420. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer CB, Franzini L, Watson M, Sanchez L, Prati L, Mitchell S, et al. Future research: A prospective longitudinal study of elder self-neglect. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:S261–S265. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer CB, Goodwin JS, Pickens-Pace S, Burnett J, Kelly PA. Self-neglect among the elderly: A model based on more than 500 patients seen by a geriatric medicine team. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1671–1676. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Morris MC, Scherr PA, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community: Relation to apolipoprotein E allele status. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60:185–189. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin. 1971;76:378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Department on Aging. Determination of need revision final report Volume I. Springfield, IL: Author; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Iris M, Ridings JW, Conrad KJ. The development of a conceptual model for understanding elder self-neglect. The Gerontologist. 2009 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp125. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NE. The racial crossover in comorbidity, disability, and mortality. Demography. 2000;37:267–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Akpom CA. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. International Journal of Health Services. 1976;6:493–508. doi: 10.2190/UURL-2RYU-WRYD-EY3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. Journal of Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longres JF. Self-neglect among the elderly. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect. 1995;7:87–105. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott S. The devil is in the details: Self-neglect in Australia. Journal of Elder Abuse Neglect. 2008;20:231–250. doi: 10.1080/08946560801973077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Memorial Foundation Quality of Health Society. 1976;54:439–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik AD, Burnett J, Pickens-Pace S, Dyer CB. Impairment in instrumental activities of daily living and the geriatric syndrome of self-neglect. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:388–393. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.3.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Elder Abuse. The National Elder Abuse Incidence Study. Washington, DC: American Public Human Services Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Elder Abuse Website. NCEA: The basics. 2006. [On-line]. Retrieved June 1, 2008, from http://elderabusecenter.org/pdf/research/apsreport030703.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson FL, Farberow NL. Indirect self-destructive behavior in the elderly nursing home patient. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1980;35:949–957. doi: 10.1093/geronj/35.6.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rawe AM. Nursing care study: Self-neglect—A challenge for nursing. Nursing Times. 1982;78:1932–1936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J, Jeune B. The mortality experience of early old-age and disability pensioners from unskilled- and semiskilled labour groups in Fredericia. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine Supplementum. 1980;16:50–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem DE. Nursing: Concepts of practice. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Orrell MW, Sahakian BJ, Bergmann K. Self-neglect and frontal lobe dysfunction. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;155:101–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostir GV, Volpato S, Fried LP, Chaves P, Guralnik JM. Reliability and sensitivity to change assessed for a summary measure of lower body function: Results from the Women’s Health and Aging Study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2002;55:916–921. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paveza G, Vandeweerd C, Laumann E. Elder self-neglect: A discussion of a social typology. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:S271–S275. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou MP, Lachs MS. Could self-neglect in older adults be a geriatric syndrome? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:831–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens S, Naik AD, Burnett J, Kelly PA, Gleason M, Dyer CB. The utility of the Kohlman evaluation of living skills test is associated with substantiated cases of elder self-neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2007;19:137–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol digit modalities test manual-revised. Los Angeles: Western Psychological; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Teaster PB. A response to abuse of vulnerable adults: The 2000 survey of state adult protective service. 2002. [On-line]. Retrieved June 1, 2008, from http://www.elderabusecenter.org/pdf/research/apsreport010703.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wallman T, Wedel H, Johansson S, Rosengren A, Eriksson H, Welin L, et al. The prognosis for individuals on disability retirement. An 18-year mortality follow-up study of 6887 men and women sampled from the general population. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]