Abstract

Brain networks with energy-efficient hubs might support the high cognitive performance of humans and a better understanding of their organization is likely of relevance for studying not only brain development and plasticity but also neuropsychiatric disorders. However, the distribution of hubs in the human brain is largely unknown due to the high computational demands of comprehensive analytical methods. Here we propose a 103 times faster method to map the distribution of the local functional connectivity density (lFCD) in the human brain. The robustness of this method was tested in 979 subjects from a large repository of MRI time series collected in resting conditions. Consistently across research sites, a region located in the posterior cingulate/ventral precuneus (BA 23/31) was the area with the highest lFCD, which suggest that this is the most prominent functional hub in the brain. In addition, regions located in the inferior parietal cortex (BA 18) and cuneus (BA 18) had high lFCD. The variability of this pattern across subjects was <36% and within subjects was 12%. The power scaling of the lFCD was consistent across research centers, suggesting that that brain networks have a “scale-free” organization.

Keywords: resting state functional MRI connectivity, functional connectomes, default mode networks, scale-free networks, consciousness

To support fast communication with minimal energy cost, cortical brain networks may have few nodes with dense local clustering (hubs) and numerous nodes with an average low number of connections (1–7). The energy-efficient regions (densely connected nodes) are thought to serve as the interconnection hubs, and neuropsychiatric diseases have been linked to abnormalities in their configuration (8, 9). However, the investigation of hubs in the brain has been hindered by the cumbersome computational requirements of comprehensive analytical methods.

During the last decade, numerous studies have evaluated the functional connectivity among brain regions by using correlation analyses of spontaneous fluctuations of brain activity measured with MRI time series in resting conditions (10). A popular technique used for the analysis of resting-state time series is based on regions-of-interest (seed regions). This technique uses correlation analysis of blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signals for the identification of brain regions functionally connected to the seed regions (reviewed in ref. 11). Cluster analyses are also used to evaluate the degree of functional connectivity among multiple seed regions (12). These methods are constrained by the fact that they rely strongly on a priori selection of specific seed regions rather than allowing for the characteristics of the network to identify and locate the node regions; these methods are also computationally demanding. For these limitations previous studies assessing the topological organization of the human brain restricted their analysis to ~102 seed regions (5, 13). More recently researchers have started to use data-driven approaches that are based on graph theory to assess the functional connectivity of the human brain using datasets obtained with MRI (14). Moreover, the overall resting functional connectivity (short- and long-range interconnections) of the gray matter (4-mm isotropic spatial resolution) was shown to correspond well with the structural connections determined with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (15) and to be associated with intellectual performance (16).

Here we propose an alternative voxelwise data-driven method that we term “functional connectivity density mapping” (FCDM), to overcome the limitations of seed-based approaches for the identification of hubs in the human brain, using resting-state functional connectivity datasets. This ultrafast technique allows calculation of individual functional connectivity maps with higher spatial resolution (≥3 mm isotropic) to take full advantage of the native resolution of the functional MRI datasets. The method is based on the highly clustered organization of the brain (14). Specifically, to speed up the computation of the number of functional connections (i.e., edges in graph theory), we restricted the temporal correlation analysis to the local functional connectivity cluster.

Thus, we aimed to determine the location of the functional connectivity hubs in the human brain by using data from the “1000 Functional Connectomes Project” (17), which is a large public database of resting-state time series that were collected independently at 35 sites around the world (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/fcon_1000/). We further aimed to evaluate the variability of the local functional connectivity density (lFCD) across subjects and imaging parameters as well as its reproducibility within and between subjects. We hypothesized that the lFCD would have low within-subjects variability and that its spatial distribution would be rather constant across research sites in the world. We also hypothesized that the probability distribution of the lFCD would have a power scaling with the number of functional connections per node, which is the main characteristic of the “scale-free” networks (6), rather than a Poisson distribution, the landmark of random and “small-world” networks (2).

Results

Metaanalysis of FCDM.

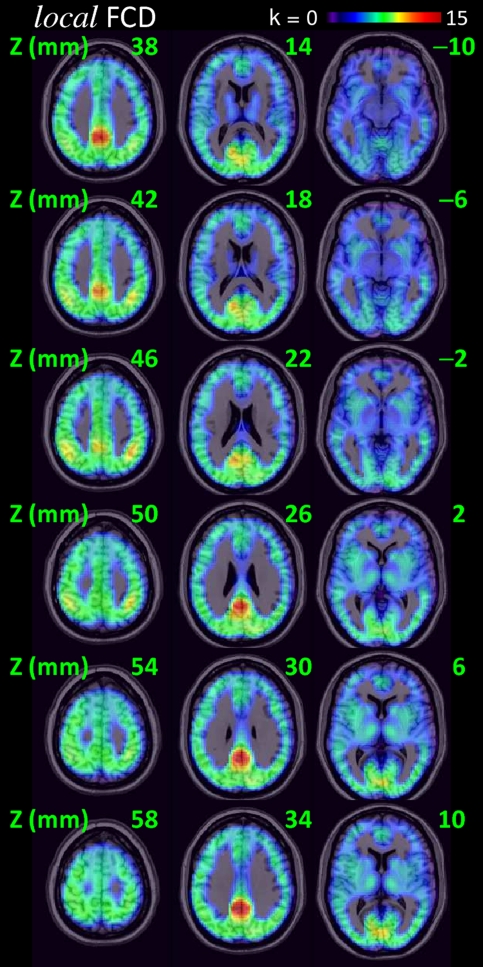

Fig. 1 shows the average distribution of the lFCD in the human brain across all 979 subjects included in this study. A region localized within the posterior cingulate cortex/ventral precuneus (BA 23/31) had the highest lFCD. Regions located in the cuneus, inferior parietal cortex, middle occipital, cingulate, middle temporal, precentral, inferior, and middle frontal gyri and claustrum, thalamus, putamen, caudate, and cerebellum also included lFCD maxima (Table 1). However, these other hubs had much lower lFCD values. The standard deviation of the hub locations was 7.3 ± 3.4 mm; thus positions of the three main hubs were rather constant across research sites. The variability in the position of the main hub (posterior cingulate cortex/ventral precuneus) across research sites was minimal (D = 4.4 ± 2.7 mm from the coordinates listed in Table 1) and comparable to the average image resolution the datasets (Δx = 3.3 ± 0.5 mm, Δy = 3.3 ± 0.5 mm, and Δz = 3.7 ± 0.6 mm). The spatial variability of the second main hub (left inferior parietal) was larger than that for the main hub (P = 0.05, t test) but still small (D = 6.7 ± 4.1 mm). The spatial variability of the occipital hub (right cuneus, BA 18; D = 10.7 ± 7.5 mm) was larger than that for the main and inferior parietal hubs (P < 0.05; t test).

Fig. 1.

Spatial distribution of the lFCD superimposed on axial MRI views of the human brain (radiological convention). These maps reflect the average number of functional connections per voxel (k) across 979 subjects from 19 research sites around the world. Green labels indicate the axial distance to the origin of the stereotactic space (Montreal Neurological Institute). The lFCD reaches maximal value in posterior cingulate/ventral precuneus (red–orange). FCDM parameters: TSNR = 50 and TC = 0.6.

Table 1.

Location, average strength (mean), and SD of the local maxima of the functional connectivity density normalized across research sites (k/k0)

| Brain region | BA or nucleus | x, mm | y, mm | z, mm | Mean (k/k0) | SD (k/k0) |

| Posterior cingulate/precuneus | 23/31 | 6 | −48 | 33 | 8.4 | 6.6 |

| Cuneus | 18 | 27 | −81 | 27 | 4.7 | 3.3 |

| Cuneus | 18 | −24 | −84 | 24 | 5.0 | 3.4 |

| Middle occipital | 18 | 33 | −87 | 6 | 4.0 | 3.1 |

| Cingulate | 24 | 6 | −9 | 45 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| Cingulate | 24 | 6 | 9 | 42 | 4.2 | 3.6 |

| Inferior parietal | 40 | −39 | −51 | 45 | 5.8 | 4.7 |

| Inferior parietal | 40 | 45 | −57 | 45 | 5.3 | 3.9 |

| Middle temporal | 39 | −48 | −63 | 24 | 4.5 | 3.1 |

| Precentral | 6 | 33 | −3 | 54 | 4.5 | 3.3 |

| Middle frontal | 6 | −30 | −3 | 54 | 3.9 | 3.0 |

| Inferior frontal | 9 | −42 | 12 | 30 | 3.9 | 3.3 |

| Inferior frontal | 9 | 48 | 15 | 30 | 3.9 | 2.7 |

| Claustrum | 13 | 36 | 6 | 6 | 3.7 | 2.5 |

| Cerebellum | Fastigial | −9 | −60 | −21 | 4.3 | 3.6 |

| Thalamus | Medial dorsal | 12 | −15 | 6 | 3.7 | 2.4 |

| Thalamus | Medial dorsal | −12 | −18 | 6 | 3.7 | 2.5 |

| Putamen | Lentiform | −15 | 9 | 6 | 3.2 | 2.3 |

| Putamen | Lentiform | −27 | 6 | 3 | 3.5 | 2.5 |

The sample consisted of 979 healthy subjects from all research sites in Table 2. The (x, y, z) coordinates are in the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) stereotaxic space.

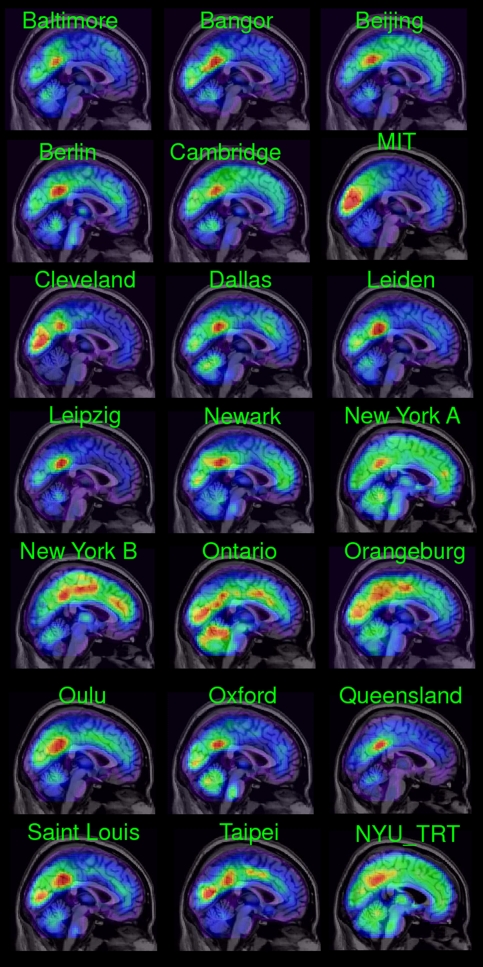

The average strength of the lFCD varied across research centers (Fig. 2), which is likely due to differences in acquisition parameters, instruments, demographic variables, and potential differences in resting conditions (e.g., eyes opened/closed, awake/sleep, etc). For most research sites the average distribution of the lFCD reached the highest values in a region located in the posterior cingulate cortex (BA 23) and extends to the precuneus (BA 31) and middle cingulum (BA 23). However, the cerebellar vermis also reached high lFCD values for some of the imaging datasets (Dallas, New York A, Ontario, Orangeburg, and Oxford). The variability of the lFCD across research sites increased the standard deviation of the lFCD, which did not have a normal distribution across subjects (Fig. S1 Left). However, the use of a single scaling factor for each research site, 1/k0, reflecting the mean lFCD across subjects and voxels in the brain, k0, allowed us to normalize the distribution of the lFCD (Fig. S1 Right) and merge the datasets from different research sites (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Spatial distribution of the average lFCD superimposed on the middle sagital MRI plane for all research sites (green labels) in this study (Table 2). FCDM parameters: TSNR = 50 and TC = 0.6.

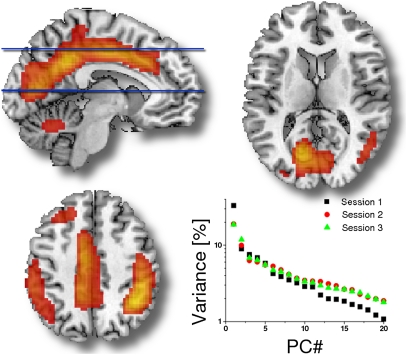

Using principal component analysis (PCA) we determined that the average intersubjects variability of the lFCD maps across centers was only 23.5 ± 1.3%. The first principal component (PC 1) of the lFCD accounted for 34.1 ± 1.3% of the variability and 11 ± 8 principal components were needed to account for 75% of the variance (Fig. 3). Using factor analysis on datasets with narrow age range (Beijing, Cambridge, Leiden, Oulu, and Saint Louis) we found that the factors of the mean lFCD were higher for women than for men (P < 0.01, t test) and that for two of the datasets (Baltimore and Cleveland) the factors of the mean lFCD were negatively correlated with age (R < −0.37; P < 0.036; Pearson's linear correlation). These gender and aging effects did not reach statistical significance for the remaining datasets.

Fig. 3.

Average spatial distribution of the first principal component (PC 1) across all research sites showing the brain regions with high lFCD variance (red–yellow: 10–30%, radiological convention). Scatter plot shows lFCD variance as a function of the principal components for each of the sessions of the New York test–retest dataset.

We accessed the statistical significance of the rescaled lFCD patterns using the 22 available datasets listed in Table 2. The rescaled lFCD was rather constant across these 979 subjects, regardless of differences in demographic variables between studies, and was statistically significant in all gray matter regions, even when correcting for multiple comparisons at the voxel level with a conservative familywise error (FWE) threshold PFWE < 0.05 (one-sample t test). Across subjects, the lFCDs in the posterior cingulate/ventral precuneus and parietal hubs were 8.5 ± 0.2 (mean ± SE) and 5.9 ± 0.2 times higher than the average lFCD in the brain, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. S2).

Table 2.

Available demographic data and imaging parameters for the selected resting-state functional MRI datasets from the image repository for the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project and the corresponding variability, principal component PC 1, and average scaling factor γ, of P(k)

| Dataset | Subjects | Age, years | tp | TR, s | Variability, % | PC 1, % | γ |

| Baltimore | 8 M/15 F | 20–40 | 123 | 2.5 | 22 | 31* | −6.5 ± 0.2 |

| Bangor | 20 M/0 F | 19–38 | 265 | 2.0 | 24 | 42 | −5.2 ± 0.1 |

| Beijing | 76 M/122 F | 18–26 | 225 | 2.0 | 32 | 27** | −5.4 ± 0.1 |

| Berlin− | 13 M/13 F | 23–44 | 195 | 2.3 | 29 | 32 | −5.4 ± 0.1 |

| Cambridge | 75 M/123 F | 18–30 | 119 | 3.0 | 31 | 33** | −5.0 ± 0.1 |

| MIT | 18 M/20 F | 20–32 | 145 | 2.0 | 25 | 22 | −5.8 ± 0.2 |

| Cleveland | 11 M/20 F | 24–60 | 127 | 2.8 | 21 | 36* | −5.1 ± 0.1 |

| Dallas | 12 M/12 F | 20–71 | 115 | 2.0 | 26 | 43 | −4.9 ± 0.1 |

| Leiden | 23 M/8 F | 20–27 | 215 | 2.2 | 21 | 40** | −4.8 ± 0.1 |

| Leipzig | 16 M/21 F | 20–42 | 195 | 2.3 | 30 | 31 | −4.7 ± 0.1 |

| Newark | 9 M/10 F | 21–39 | 135 | 2.0 | 22 | 30 | −5.3 ± 0.1 |

| New York A | 40 M/19 F | 20–49 | 192 | 2.0 | 29 | 24 | −4.0 ± 0.1 |

| New York B | 8 M/12 F | 18–46 | 175 | 2.0 | 37 | 30 | −5.2 ± 0.1 |

| NYU_TRT | 10 M/17 F | 22–49 | 197 | 2.0 | 31 | 33 | −5.6 ± 0.6 |

| Ontario | 11 subjects | N/A | 105 | 3.0 | 24 | 30 | −5.0 ± 0.1 |

| Orangeburg | 15 M/5 F | 20–55 | 165 | 2.0 | 19 | 41 | −5.4 ± 0.1 |

| Oulu | 37 M/66 F | 20–23 | 245 | 1.8 | 33 | 29** | −4.6 ± 0.1 |

| Oxford | 12 M/10 F | 20–35 | 175 | 2.0 | 24 | 36 | −5.3 ± 0.1 |

| Queensland | 11 M/8 F | 20–34 | 190 | 2.1 | 19 | 41 | −4.9 ± 0.1 |

| Saint Louis | 14 M/17 F | 21–29 | 127 | 2.5 | 23 | 29** | −4.8 ± 0.1 |

| Taipei A | 14 subjects | N/A | 295 | 2.0 | 24 | 40 | −4.4 ± 0.1 |

| Taipei B | 8 subjects | N/A | 175 | 2.0 | 21 | 49 | −5.1 ± 0.1 |

For some of the research sites the factors of the principal component were significantly correlated (P < 0.05) with age (*) or gender (**). tp, number of time points in the image time series. M, males; F, females.

P(k) Distribution.

The probability distribution of the lFCD can be calculated as P(k)= n(k)/n0, where n(k) is the number of voxels with k functional connections and n0 is the total number of voxels in the brain. Fig. S3 shows P(k) as a function of k for a typical subject and three different threshold TC criteria. For voxels with more than five functional connections, P(k) decreases with k following a power scaling:

The scaling factor, γ, did not vary significantly across threshold conditions and the power scaling between P(k) and k was robust across subjects (Fig. S3). The scaling factor γ varied from −4.0 to −6.5 across centers (Table 2 and Fig. S4).

Test–Retest Reliability.

The within-subjects reproducibility of FCDM was evaluated using the New York test–retest reliability (NYU_TRT) dataset (18). For all sessions, lFCD was high bilaterally in posterior cingulate/ventral precuneus, inferior parietal and occipital cortices, cingulate gyrus, anterior insula, caudate, thalamus, and cerebellar vermis (Fig. S5). The lFCD in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex, pons, and cerebellum were higher for session 1 than for session 2 whereas only the lFCD in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex was higher for session 1 than for session 3. There were no statistically significant lFCD differences between sessions 2 and 3. Using PCA we found that the global variability of the lFCD data across subjects was <26%. Consistently for all three sessions, PC 1 was similar to the map of the average lFCD (especially for session 1) and accounted for 20% of variance of the data (Fig. 3 and Fig. S6). Differently, the spatial distribution of the second component (PC 2) was variable across sessions (Fig. S6) and accounted for 10% of the variance of the data. Using region-of-interest (ROI) analyses we verified that the lFCD data had 36 ± 8% between-subjects variability and 12 ± 6% within-subjects variability on average across the 19 ROIs listed in Table 1.

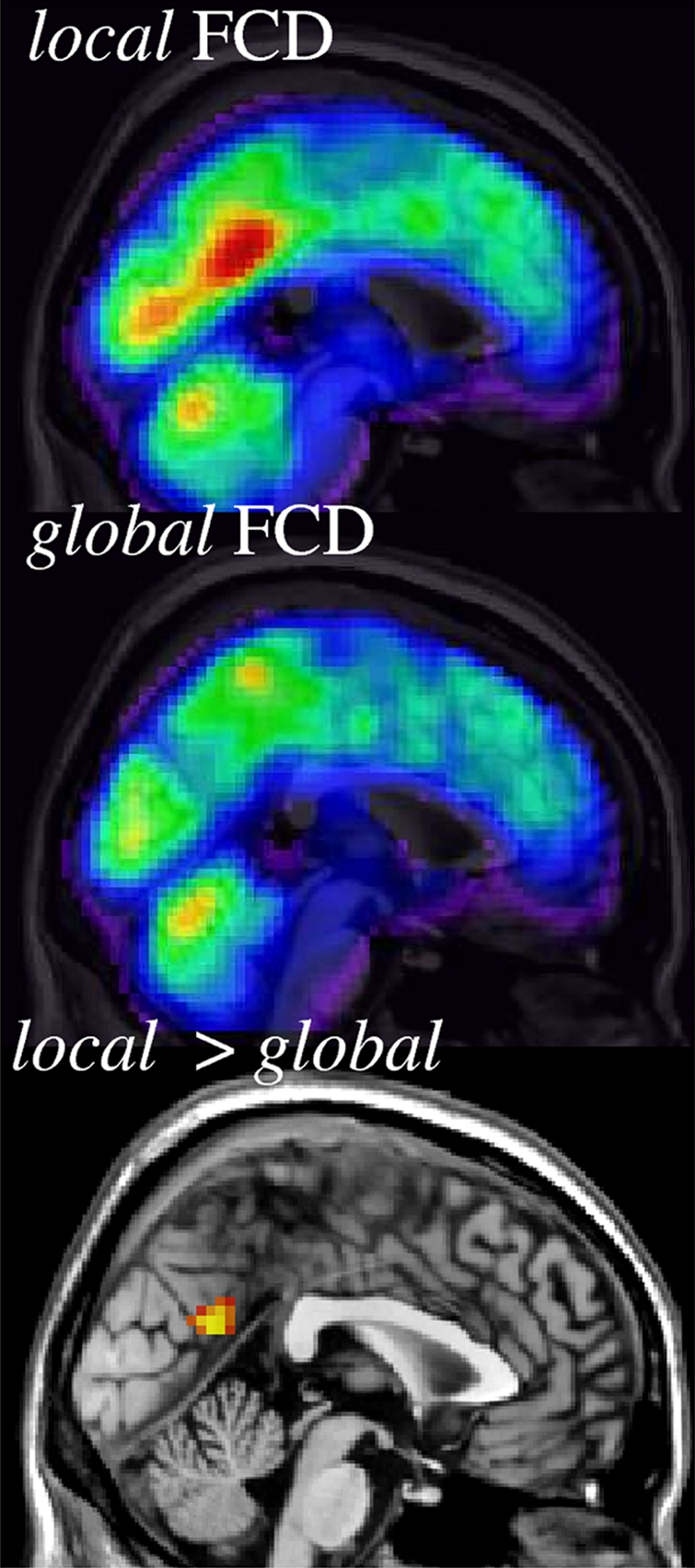

lFCD Versus Global (g)FCD.

Only two datasets (Ontario and Baltimore, 34 subjects) were used to contrast lFCD against gFCD due to the CPU time demands of the gFCD calculation. Whereas the ultrafast lFCD calculation required only 4 min/subject using a standard Windows XP platform (3.0-GHz dual core Intel processor), the computer-demanding gFCD calculation required 5,406 min/subject using the same platform. Thus, the (local cluster restricted) lFCD calculation was 1,351 times faster than the (unrestricted) gFCD calculation. The rescaled gFCD, K/K0, had similar spatial distribution to the lFCD, k/k0, but did not show the posterior cingulate/ventral precuneus hub, a brain region where the rescaled lFCD was significantly higher than the rescaled gFCD (PFWE-corr < 0.001, paired t test; Fig. 4 and Fig. S7A). In other regions, however, there were not significant differences between lFCD and gFCD (PFWE-corr > 0.2, paired t test). The probability distribution was similar for both approaches but its scaling factor was higher (less negative) for gFCD than for lFCD (Fig. S7B).

Fig. 4.

Spatial distribution of the rescaled lFCD (blue–red: k/k0 = 0–10) and gFCD (blue–red: K/K0 = 0–10) and a statistical map (orange–yellow: PFWE-corr < 0.05; paired t test) of the significant differences between lFCD and gFCD across 34 healthy subjects from two research sites (Ontario and Baltimore), superimposed on the middle sagittal MRI view of the human brain. TSNR = 50 and TC = 0.6.

Discussion

Here we propose a data-driven method to map the lFCD from resting-state MRI time series. FCDM achieves ultrafast computation by restricting the calculation to the local functional connectivity clusters. Typically, only a few minutes are required to map the lFCD in the whole brain from single-subject data, which is >1,000 times faster than what can be achieved using traditional global approaches. The methodology further includes the necessary preprocessing steps to minimize motion and physiologic artifacts. Principal component analysis, ROI analyses, and statistical parametric mapping (SPM) t tests were used to quantify the robustness of FCDM using resting-state functional MRI datasets from the image repository “1000 Functional Connectomes.” The between-subjects variability of the lFCD was <36% and the within-subjects variability of the lFCD was 12%.

Spatial Distribution of lFCD.

The main finding of this study is that in resting conditions the spatial distribution of the lFCD is highly localized in posterior cingulate/ventral precuneus and middle cingulum as well as occipital (cuneus and calcarine cortex) and inferior parietal regions. Thus, as suggested by previous studies (8), these regions are likely the functional hubs of the brain. The posterior and middle cingulum and the ventral precuneus are interconnected core regions of the default mode network (19) that also connect to motor regions and include dorsal and ventral visual stream inputs (20). These regions are more active at rest than during cognitive performance and show negative BOLD responses during cognitive functional MRI tasks (21). The precuneus is a brain region whose activity is associated with the overall state of consciousness (22) and positron emission tomography (PET) studies consistently show it has the highest metabolism in brain (along with cingulate and visual cortical areas) (23, 24), suggesting that it is an important hub for intrinsic activity in the human brain. Because glucose metabolism supports the energy requirements of neuronal activity (25, 26), and it is assumed that the capacity of the human brain depends on energy-efficient cortical networks (1–5), our findings suggest that higher glucose metabolism in ventral precuneus, cingulate, and visual regions serves to support a higher communication rate in these regions. In the posterior cingulate/ventral precuneus the gFCD was lower than the lFCD, suggesting that the functional connectivity of this region is well localized rather than globally distributed as for the remaining brain regions. The neuronal density might explain the high lFCD in the visual regions (calcarine cortex and cuneus). These regions are essential for visual processing (27) and have up to 2.5 times higher neuronal density than all other cortical regions (28).

FCDM Variability.

This study quantified the variability of resting-state functional connectivity datasets. Across subjects, the variability of FCDM was <36%. Within subjects the variability of FCDM was 12%. Numerous principal components (11 ± 8) were needed to account for 75% of the variability of FCDM although PC 1 alone accounted for 34% of the variability. Because PC 1 maps into the nodes with the highest connectivity, this result suggests that the highly connected regions account for a significant portion of the intersubject variability. Multiple factors might influence this variability such as demographics (age, gender), state of the subjects (alertness, fatigue, excitement), and/or genetics. Indeed our findings on gender effects on the mean lFCD and the negative correlation of the mean lFCD with age for two of the datasets suggest that gender and perhaps also age contribute to the variability of lFCD. Similarly lFCD in rostral cingulate gyrus (part of PC 1) differed between the test–retest sessions, which suggests that the state of the subjects also influences FCDM variability.

Within subjects, the variability of FCDM (estimated from the New York dataset, which evaluated subjects in three different sessions) corresponded to 12 ± 6%. Overall, taking into account that the reliability of BOLD functional MRI studies typically ranges between 20 and 80% (29–31), the test–retest variability of the lFCD in resting conditions seems to be comparable or lower than that of standard functional imaging techniques.

Study Limitations.

FCDM and seed–voxel correlation analysis of functional connectivity are complementary. FCDM gives a voxelwise measure of the amount of functional connections but does not provide the directionality of the functional connectivity, which can be assessed with seed–voxel correlation analyses. Therefore, FCDM could be used to identify hub locations that could then be used to select seed regions for subsequent functional connectivity analyses.

The ultrafast FCDM calculation is restricted to the local functional connectivity cluster. Thus, the FCDM results do not account for long-range functional connections. However, this should not be interpreted as a strong limitation because previous studies have shown the free-scale topology of the brain, suggesting that its networks are highly clustered (14), and the restriction of the calculation enhances the regional specificity of the results. Indeed, we show that the lFCD calculation produces similar results and has higher sensitivity for local hub detection than the computer-demanding gFCD calculation.

The functional connectivity datasets may contain physiological noise (heart rate) (10). Taking into account that band-pass filtering removes the magnetic field drift (32), the main source of low-frequency fluctuations (33), we estimate that heart rate could explain up to 10% of the variability of the functional connectivity patterns across subjects.

Conclusion.

Here we showed that as hypothesized, the probability distribution of lFCD had a power scaling with k and that this scaling was robust across different threshold conditions, subjects, and research sites. These findings suggest that functional brain networks have a scale-free organization that shows a high degree of consistency across and within individuals.

Methods

Subjects.

To evaluate the test–retest reliability as well as the within- and between-subjects variability of FCDM we used data from 979 healthy subjects (see demographic information in Table 2) from the image repository for the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project, which includes resting-state functional MRI datasets independently collected at 35 sites and can be assessed at http://www.nitrc.org/projects/fcon_1000/. Specifically, the dataset analyzed in this study includes data from 19 of these sites (Table 2). Datasets from the remaining 16 sites of the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project either were not available (pending verification of IRB status) or did not meet the imaging acquisition criteria (3 s ≥ repetition time, full brain coverage, time points >100, spatial resolution better than 4 mm) and were not included in this study.

FCDM.

Standard functional MRI and FCDM share similar data processing steps (Fig. S8). For multisubject studies, FCDM required two consecutive preprocessing steps: imaging realignment was required to minimize spurious motion-related effects (34), and spatial normalization was required to account for differences in brain size, shape, and orientation across subjects (35). We used the statistical parametric mapping package SPM2 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK) for these purposes. Specifically, the images were motion corrected with a 12-parameter affine transformation and spatially normalized to the standard brain using a 12-parameter affine transformation with medium regularization, 16-nonlinear iterations, voxel size of 3 × 3 × 3 mm3, and the SPM2 EPI.mnc template.

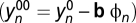

Because of magnetic susceptibility differences at air/tissue interfaces in the head, the MRI signal is sensitive to head motion (36). Therefore, the MRI signal can be correlated with motion, even after image realignment. Because the spontaneous signal fluctuations in the MRI signal are very small (<0.5%), it is essential to minimize motion-related fluctuations in the MRI signal, a step that we refer to as motion filtering. Specifically, motion filtering involved multilinear regression of the time-varying MRI signals, yn = f(tn), using the six realignment parameters (xn: three translations and three rotations),

where the fitting parameters ai (1 < i < 6) are the amplitudes of the signal drift as a function of each motion component, and  is the motion-filtered imaging time series. The removal of motion-correlated fluctuations from the imaging time series,

is the motion-filtered imaging time series. The removal of motion-correlated fluctuations from the imaging time series,

occurred for all volume elements (voxels) of the image and partially removed physiologic noise of cardiac and respiratory origin. A similar approach (physiologic noise filtering) could be used to further remove physiologic noise, which is one of the most important confounds of functional connectivity datasets (37), if respiratory and/or pulse rate data (ϕn) are collected simultaneously with the resting-state imaging time series  . We were not able to perform physiologic noise filtering because physiologic data were not available in this study. As in standard analyses of functional connectivity datasets, 0.01- tο 0.10-Hz band-pass temporal filtering was used to remove magnetic field drifts of the scanner (32) and physiologic noise of high-frequency components (38).

. We were not able to perform physiologic noise filtering because physiologic data were not available in this study. As in standard analyses of functional connectivity datasets, 0.01- tο 0.10-Hz band-pass temporal filtering was used to remove magnetic field drifts of the scanner (32) and physiologic noise of high-frequency components (38).

Two parameters were used to calculate the lFCD: The correlation threshold, TC, was used to determine significant correlations between voxels and the MRI signal-to-noise ratio threshold, TSNR, was used to evaluate which voxels of the image will be subject to correlation analyses. Taking into account that TC < 0.4 leads to increased false positive rate and increased CPU time to compute the maps and that TC > 0.7 lead to lFCD maps with lower sensitivity due to reduced dynamic range, we fixed TC = 0.6 for all calculations of FCDM. Similarly we fixed TSNR = 50 for all calculations of FCDM to minimize the false positive rate of lFCD maps especially near air/tissue interfaces, which are known to produce MRI signal loss artifacts (near the sinus cavity and temporal bone). The number of functional connections between a given voxel and other voxels was computed through correlation using these threshold parameters. Specifically, we used Pearson's linear correlations to evaluate the strength of the functional connectivity between voxels. Functional connections with correlation coefficient R > TC were considered significant. The number of significant functional connections per voxel in the local cluster, k, was computed using a three-dimensional searching algorithm developed in IDL (ITT Visual Information Solutions) that detects the boundaries of the voxel's cluster using TC and TSNR. Thus, k is determined when the boundary of the voxel's functional cluster is completely detected. Then, the calculations involving cluster detection and computation of significant functional connections are repeated for the next imaging voxel. Thus, an lFCD map reflecting k was computed and saved in Analyze format in hard drive for each subject. As in standard functional MRI studies, spatial smoothing (8 mm) was necessary to minimize the differences in the functional anatomy of the brain across subjects (35).

Global FCD.

To evaluate the differential effect of long-range connectivity on FCD and on CPU time we computed the gFCD for two of the datasets (Baltimore and Ontario). The voxelwise and computer-demanding gFCD calculation had the same spatial resolution, as well as preprocessing (realignment, spatial normalization, and motion and temporal filtering) and postprocessing (spatial smoothing) steps as for lFCD, but it determines the number of significant connections (R > TC) without local cluster restrictions.

Principal Component Analyses.

PCA was used to analyze the variability of FCDM across subjects. lFCD maps with zero empirical mean were calculated by subtracting the average lFCD value across subjects from the lFCD data. Then, we computed the principal components of FCDM datasets using the covariance of the data in IDL.

Statistical Analyses.

Group analyses of FCDM were performed with t tests using the general lineal model in SPM2. Clusters with pcorr < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons using a familywise error (FWE) threshold, were considered significant in group analysis of FCDM. The Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates of the lFCD-cluster maxima were transformed to the Talairach space using a best-fit transform (icbm_spm2tal; http://brainmap.org/icbm2tal/) that minimizes bias associated with reference frame and scaling. The brain regions were labeled according to the Talairach daemon (http://www.talairach.org/) and a query range of 5 mm to account for the spatial uncertainty of the MRI signal. We further checked the labels of the hubs using the automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas and the Brodmann atlas, which are included in the MRIcro software (http://www.cabiatl.com/mricro/).

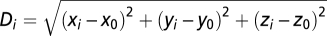

Variability of the Hub Coordinates.

A map of average lFCD across subjects was computed and the coordinates of the lFCD maxima were determined for each research site using an automatic feature from accelerated segment test (FAST) algorithm that was developed in IDL. The Euclidian distance,  , from the average hub position across research sites,

, from the average hub position across research sites,  , in Table 1 to the hub position for the i-research site,

, in Table 1 to the hub position for the i-research site,  , was computed for the three main cortical hubs [posterior cingulate/precuneus (BA 23/31), left inferior parietal (BA 40), and right cuneus (BA 18)] and all research sites.

, was computed for the three main cortical hubs [posterior cingulate/precuneus (BA 23/31), left inferior parietal (BA 40), and right cuneus (BA 18)] and all research sites.

ROI Analyses.

Isotropic cubic masks containing 27 imaging voxels (0.73 mL) were defined at the centers of relevant functional connectivity hubs (Table 1) to extract the average strength of the lFCD signal from individual lFCD maps. The average and standard deviation values of the lFCD within these ROIs were computed for each subject using a custom program written in IDL.

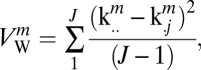

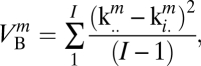

lFCD Retest Reliability.

The three sessions of the New York test–retest (NYU_TRT) dataset were used to evaluate the reliability of FCDM. Specifically, the ROI-averaged lFCD coefficients kmij corresponding to the 1 ≤ m ≤ M = 19 ROIs in Table 1, 1 ≤ i ≤ I = 25 subjects, and 1 ≤ j ≤ J = 3 sessions, were used to compute the within,

|

and between,

|

subjects variance for each ROI from which the relative lFCD variability

and

were estimated. Note that  are the averages of km across sessions, subjects, and both sessions and subjects for each ROI, respectively.

are the averages of km across sessions, subjects, and both sessions and subjects for each ROI, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was accomplished with support from National Institutes of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant 2RO1AA09481.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1001414107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Laughlin SB, Sejnowski TJ. Communication in neuronal networks. Science. 2003;301:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.1089662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature. 1998;393:440–442. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassett DS, Bullmore E. Small-world brain networks. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:512–523. doi: 10.1177/1073858406293182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvador R, et al. Neurophysiological architecture of functional magnetic resonance images of human brain. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1332–1342. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Achard S, Salvador R, Whitcher B, Suckling J, Bullmore E. A resilient, low-frequency, small-world human brain functional network with highly connected association cortical hubs. J Neurosci. 2006;26:63–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3874-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barabasi AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barabási AL. Scale-free networks: A decade and beyond. Science. 2009;325:412–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1173299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckner RL, et al. Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: Mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1860–1873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5062-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassett DS, et al. Hierarchical organization of human cortical networks in health and schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9239–9248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1929-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordes D, Haughton V, Carew JD, Arfanakis K, Maravilla K. Hierarchical clustering to measure connectivity in fMRI resting-state data. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Achard S, Bullmore E. Efficiency and cost of economical brain functional networks. PLOS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Heuvel MP, Stam CJ, Boersma M, Hulshoff Pol HE. Small-world and scale-free organization of voxel-based resting-state functional connectivity in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2008;43:528–539. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Heuvel MP, Mandl RC, Kahn RS, Hulshoff Pol HE. Functionally linked resting-state networks reflect the underlying structural connectivity architecture of the human brain. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:3127–3141. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Heuvel MP, Stam CJ, Kahn RS, Hulshoff Pol HE. Efficiency of functional brain networks and intellectual performance. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7619–7624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1443-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biswal BB, et al. Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4734–4739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911855107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shehzad Z, et al. The resting brain: Unconstrained yet reliable. Cereb Cortex. 2009;10:2209–2229. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raichle ME, et al. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogt BA, Vogt L, Laureys S. Cytology and functionally correlated circuits of human posterior cingulate areas. Neuroimage. 2006;29:452–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomasi D, Ernst T, Caparelli EC, Chang L. Common deactivation patterns during working memory and visual attention tasks: An intra-subject fMRI study at 4 Tesla. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:694–705. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horovitz SG, et al. Decoupling of the brain's default mode network during deep sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11376–11381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901435106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raichle ME, Gusnard DA. Appraising the brain's energy budget. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10237–10239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172399499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langbaum JB, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Categorical and correlational analyses of baseline fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography images from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Neuroimage. 2009;45:1107–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shulman RG, Hyder F, Rothman DL. Lactate efflux and the neuroenergetic basis of brain function. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:389–396. doi: 10.1002/nbm.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruetter R. Glycogen: The forgotten cerebral energy store. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:179–183. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tootell RB, et al. Functional analysis of primary visual cortex (V1) in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:811–817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Changeux J. Neuronal Man. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aron AR, Gluck MA, Poldrack RA. Long-term test-retest reliability of functional MRI in a classification learning task. Neuroimage. 2006;29:1000–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong J, et al. Test-retest study of fMRI signal change evoked by electroacupuncture stimulation. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1171–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manoach DS, et al. Test-retest reliability of a functional MRI working memory paradigm in normal and schizophrenic subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:955–958. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foerster BU, Tomasi D, Caparelli EC. Magnetic field shift due to mechanical vibration in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1261–1267. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bianciardi M, et al. Sources of functional magnetic resonance imaging signal fluctuations in the human brain at rest: A 7 T study. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friston KJ, Williams S, Howard R, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Movement-related effects in fMRI time-series. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:346–355. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friston K, Ashburner J, Kiebel S, Nichols T, Penny W. Statistical Parametric Mapping: The Analysis of Functional Brain Images. London: Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caparelli EC, Tomasi D, Ernst T. The effect of small rotations on R2* measured with echo planar imaging. Neuroimage. 2005;24:1164–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shmueli K, et al. Low-frequency fluctuations in the cardiac rate as a source of variance in the resting-state fMRI BOLD signal. Neuroimage. 2007;38:306–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cordes D, et al. Frequencies contributing to functional connectivity in the cerebral cortex in “resting-state” data. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1326–1333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.