Abstract

A profluorescent probe that has no fluorescent response to H2O2, iron or copper ions but can be readily activated in the presence of both H2O2 and Fe (or Cu) ion has been developed; the probe is capable of detecting oxidative stress promoted by Fe (or Cu) and H2O2 (i.e. the Fenton Reaction conditions) in living cells.

Oxidative stress plays a major role in the pathogenesis of a large number of human diseases, among which, the highly reactive and deleterious oxidizing species produced via the reaction of endogeneous H2O2 and redox metals (e.g., iron and copper) (the Fenton reactions (eq. 1)) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of Wilson’s disease, Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), atherosclerosis, hemochromatosis, liver damage, cancer and diabetes, etc.1 Abnormal accummulation of redox metals (e.g., iron and copper) and overproduction of H2O2 in certain tissues in the body have been observed in patients with neurodegenerative diseases.1 Elevated levels of redox metal ions and H2O2 and the Fenton reactions contribute to the oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. We and others have been developing agents capable of performing H2O2-triggered “anti-Fenton reaction” via a prochelator activation and a subsequent metal caging strategy.2,3 The advantage of this novel strategy is that chelation can only be triggered by toxic levels of H2O2 thus will not interfere with the healthy metal homeostasis, holding promise in combating these diseases. However, a direct demonstration of the mechanism of this novel strategy in living systems is still lacking.

| (1) |

To provide direct evidence on the mechanism of this novel anti-Fenton strategy in living systems, we have developed our third generation prochelator, RS-BE, which is profluorescent and does not react with Fe (or Cu) ions. However, it can be converted to an active chelator by H2O2, still fluorescence silent, but the fluorescence is activated upon metal chelation on the active chelator. Thus, the “anti-Fenton process” is readily monitored by an ideal “turn-on” fluorescent process in living cells which is described in this communication.

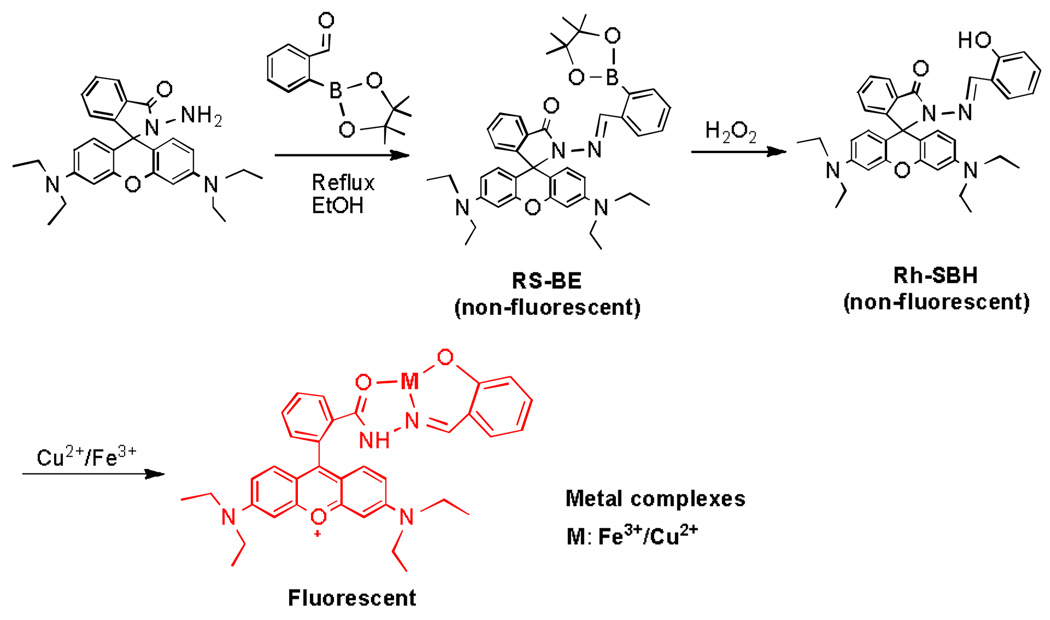

The profluorescent prochelator RS-BE was designed by “masking” the key chelating hydryoxyl group in the active chelator Rh-SBH with a bulky boronic acid pinacol ester group which may be unmasked by H2O2 (Scheme 1). Subsequent metal coordination with the active chelator Rh-SBH may induce the conversion of the profluorescent Rh-SBH molecule from the ring-closed spirolactam form (non-fluorescent) to the ring-opened amide form (fluorescent) in the metal complexes (Scheme 1).4 This metal-coordination induced profluorescence activation process may be called a “coordination-induced fluorescence activation (CIFA)”.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis and activation of RS-BE

Synthesis of the prochelator RS-BE was accomplished in 3 0 % yield by refluxing rhodamine hydrazine and 2-fomylphenylboronic acid, pinacol ester in ethanol (ESI†). The active chelator, Rh-SBH, was also synthesized and characterized following a published procedure. 4

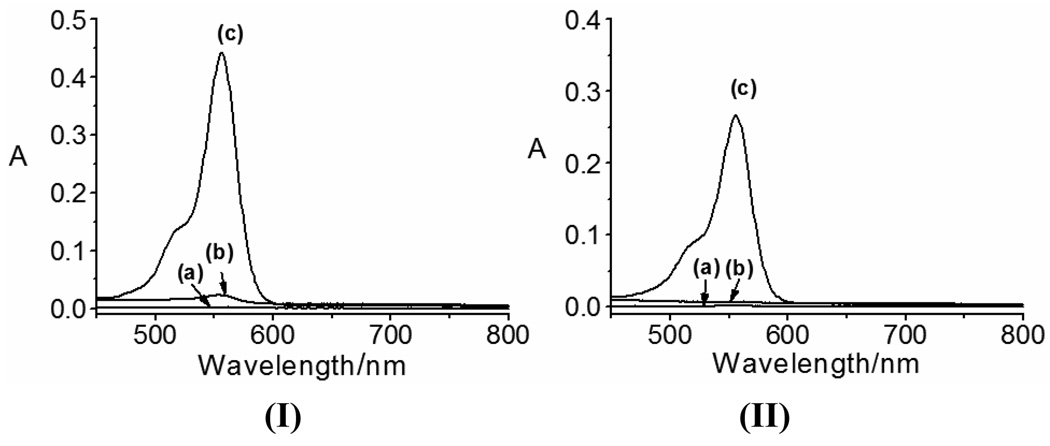

The UV-vis spectroscopic properties of RS-BE and its interactions with Cu2+, Fe2+ and H2O2 were evaluated first. Due to limited water solubility of RS-BE, a mixed solvent acetonitrile(ACN)/potassium phosphate buffer (KPB) (10 mM, pH 7.5, v/v 1:1) was used. Solution of RS-BE (50 µM) is colorless, exhibiting absorption in UV region (240–300 nm) only (Fig.S1). As shown in Fig.1 and Fig. S1, addition of Cu2+ or Fe2+ ions changes little the aborption characteristics of RS-BE, suggesting the prochelator does not bind strongly to Cu2+ or Fe2+ ions under the conditions. However, upon addition of excess H2O2 to the systems (60 min incubation with 500 µM H2O2), the solutions turned pink and a new peak at 550 nm was observed in both the Cu2+- and Fe2+-RS-BE systems (Fig.1 and Fig. S1; Fe2+ may be oxidized to Fe3+ by excess H2O2 here), implying metal-chelation occurred via a H2O2-triggered prochelator activation (from RS-BE to Rh-SBH) and subsequent metal-chelation mechanism (Scheme 1), as demonstrated for our previously designed prochelators.2 Further investigations on the interactions of Fe2+ or Fe3+ with the active chelator Rh-SBH suggest that Rh-SBH response to Fe3+, not Fe2+(Fig. S2). A strong response of Rh-SBH to Cu2+ but a weaker response to Fe2+ were also reported under aerobic conditions in a different buffer (ACN/Tris, 10 mM, pH 7.0).4 The appearance of the new peak at 550 nm has been assigned to the metal-binding induced conversion from ring-closed spirolactam form of Rh-SBH (colourless) to the ring-opened amide form (pink) in the metal complexes.4 Rh-SBH displays a selective absorption response to Cu2+ and Fe3+ over other metal ions (Fig. S3), and the spirolactam form is stable over pH 5.0 to 8.2, in agreement with that reported.4

Fig. 1.

Absorption spectra of RS-BE and its interactions with Cu2+ (I) or Fe2+ (II) before and after addition of 500 µM H2O2 in ACN/KPB buffer (10 mM, pH 7.5, v/v 1:1): (a) RS-BE (50 µM) only, (b) RS-BE with metal ions (50 µM) and (c) with metal ions and H2O2 (500 µM).

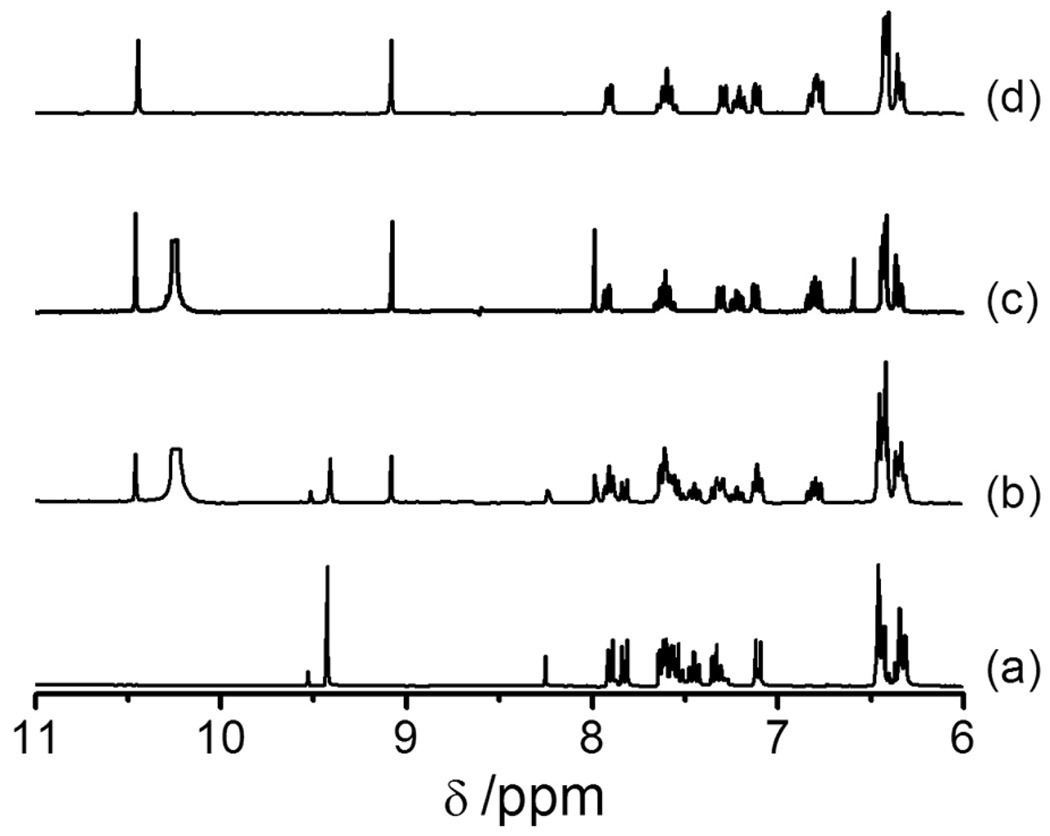

The clean conversion of RS-BE to RH-SBH by H2O2 was further confirmed via NMR spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 2, after incubating RS-BE with H2O2, 1H NMR peaks for RS-BE (δ 9.42(s), =CH-) gradually decreased in intensity, while the peaks corresponding to Rh-SBH (δ 9.09(s), =CH-; 10.45(s) – OH−) appeared simultaneously and increased in intensity with time. The peaks (δ7.81(d), 7.51–7.57(m) and 7.30(t), salicylaldehyde) also underwent similar conversions. Meanwhile, the peaks for boric acid and pinacol, the H2O2-deprotected products of the boronic acid pinacol ester moiety, appeared at δ6.55(s, B(OH)3), δ7.99(s, -OH) and δ1.15 (s, 4×(CH3), Figs. S5, S6). No 1H NMR change was observed for the xanthene moiety due to its distance from the reaction site. In ~2 h, RS-BE had been cleanly converted to Rh-SBH with no intermediate formed, as indicated by the 1H-NMR spectra. 13C-NMR data also confirmed that RS-BE was converted by H2O2 to Rh-SBH which is still in the the ring-closed spirolactam form (Fig. S7).

Fig. 2.

1H NMR spectra (from δ11.0- 6.0, (CD3)2SO) ) of (a) RS-BE (5 mM); (b) and (c), the reaction of RS-BE (5 mM) with H2O2 (50 mM) at 293 K after 1 h and 2 h, respectively; and (d) Rh-SBH (5 mM).

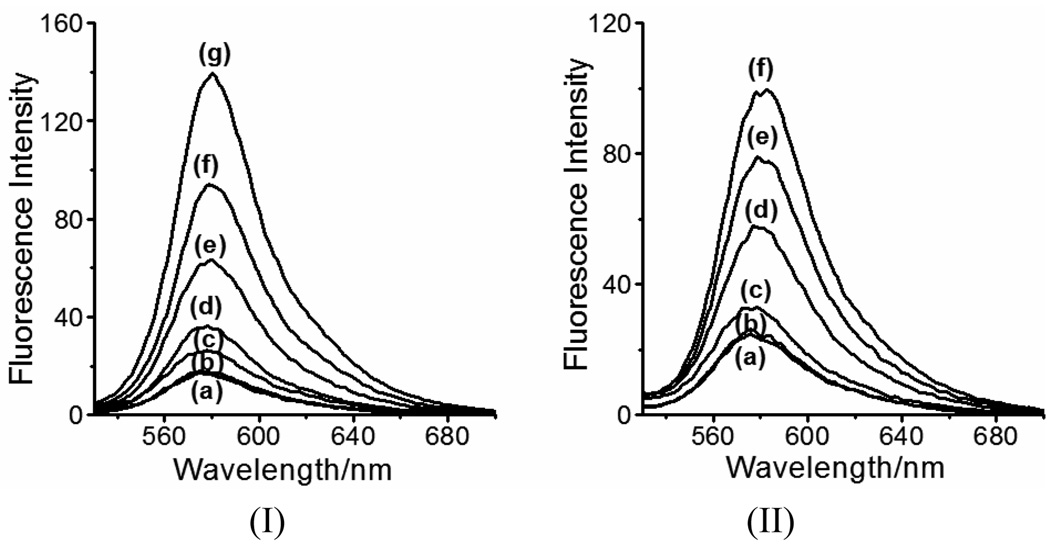

We further examined the fluorescence responses of RS-BE to Cu2+, Fe2+ and H2O2. As shown in Fig. 3, RS-BE in ACN/KPB buffer (1:1, pH 7.5) exhibits weak fluoresence at 575 nm (curve (a)). The fluorescence is not affected by the presence of H2O2 (Fig. S8). Addition of Cu2+ or Fe2+ (curves (b) in Fig. 3) to RS-BE in the absence of H2O2 did not change its fluorescence profiles either. However, upon the addition of H2O2 to the system containing RS-BE/Cu2+(or Fe2+), as we expected, the fluorescent intensity at 575 nm increased with time (curves (c)–(g) in Fig.3 (I) and (c)–(f) in Fig. 3 (II)). At 2 h, a ~7.5-fold increase in fluorescent intensity was observed in the RS-BE/Cu2+/H2O2 system while a ~5-fold increase in the RS-BE/Fe2+/H2O2 system (Fe2+ may be oxidized to Fe3+ by excess H2O2 here). In addition, the emission spectrum of RS-BE/Cu2+(or Fe2+) underwent a red shift from 575 nm to 580 nm after the addition of H2O2. This fluorescence response matches those observed for the reactions of Rh-SBH with metal ions.4 Therefore, we can conclude that in the presence of Cu2+(or Fe2+), the fluorescence enhancement of RS-BE upon additon of H2O2 must be occurred via a H2O2-triggered prochelator activation (from RS-BE to Rh-SBH) and subsequent metal-chelation mechanism (Scheme 1), corroborating the conclusions from the UV-vis studies (Fig. 1). These interesting fluorescent responses offer us the opportunity to study the “anti-Fenton” mechanism in living cells by using RS-BE as a novel “turn-on” fluorescent probe.

Fig. 3.

H2O2-triggered fluorescence responses (Ex, 510 nm; Em, 580) of RS-BE (50 µM) to Cu2+ (I) or Fe2+ (II) (50 µM) in ACN/KPB buffer (10 mM, pH 7.5, v/v 1:1). (Ia) and (IIa) RS-BE only; (Ib) and (IIb) RS-BE with Cu2+ and Fe2+, respectively; from (Ic) to (Ig), RS-BE/Cu2+ incubated with 500 µM H2O2 for 10, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min, respectively; from (IIa) to (IIf), RS-BE/Fe2+ incubated with 500 µM H2O2 for 30, 60, 90 and 120 min, respectively.

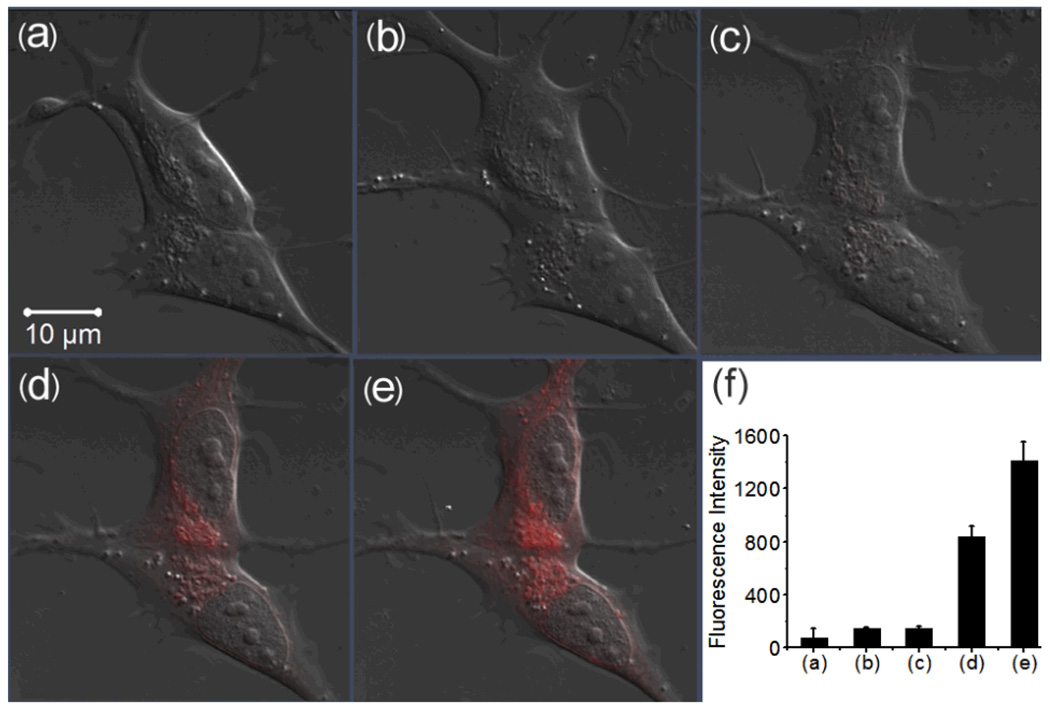

RS-BE was then tested in live cells (SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, a human neuronal cell line) its fluorescent responses to Cu2+, Fe3+ and H2O2 via a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710). Iron- and copper-8-hydroxylquinoline complexes (Fe(8-HQ) and Cu(8-HQ)) were used to enhance membrance permeability of the metal ions.5,6 Human SH-SY5Y cells loaded with 10 µM RS-BE (incubated for 30 min) did not show intracellular fluoresence (Fig. 4(b)). Then, the cells were further implemented with 10 µM Fe(8-HQ). No fluorescence was observed after 30 min incubation (Fig. 4(c)), suggesting that the normal cellular components or the added Fe(8-HQ) does not trigger fluorescent signal of the profluorescent probe RS-BE, as we desired. At last, we treated the Fe(8-HQ) loaded cells with 100 µM H2O2, followed by immediate recording fluorescence images of the cells every 5 mins for 30 min. Excitingly, as shown in Fig. S9 and Fig. 4(d) and (e), intracellular fluorescent signal which matches the profile of Rh-SBH-metal comlexes emerged after 5 min treatment with H2O2 and increased in intensity with time. A ~10-fold increase in intensity was observed after 25 min (Fig.4(f)). These data suggest that a H2O2-triggered prochelator activation (from RS-BE to Rh-SBH) followed by Fe-chelation occurred in the cells.

Fig. 4.

Confocal fluorescence images of live human SH-SY5Y cells with the treatment of RS-BE/Fe/ H2O2 (scale bar 10 µm). (a) DIC; (b) the cells incubated with 10 µM RS-BE for 30 min; (c) the cells were then incubated with 10 µM Fe(8-HQ) for 30 min; (d) and (e) the cells were further treated with 100 µM H2O2 for 10 and 25 min, respectively, (f) Integrated emission (547–703 nm) intensity of (a), (b), (c), (d) and (e) images.

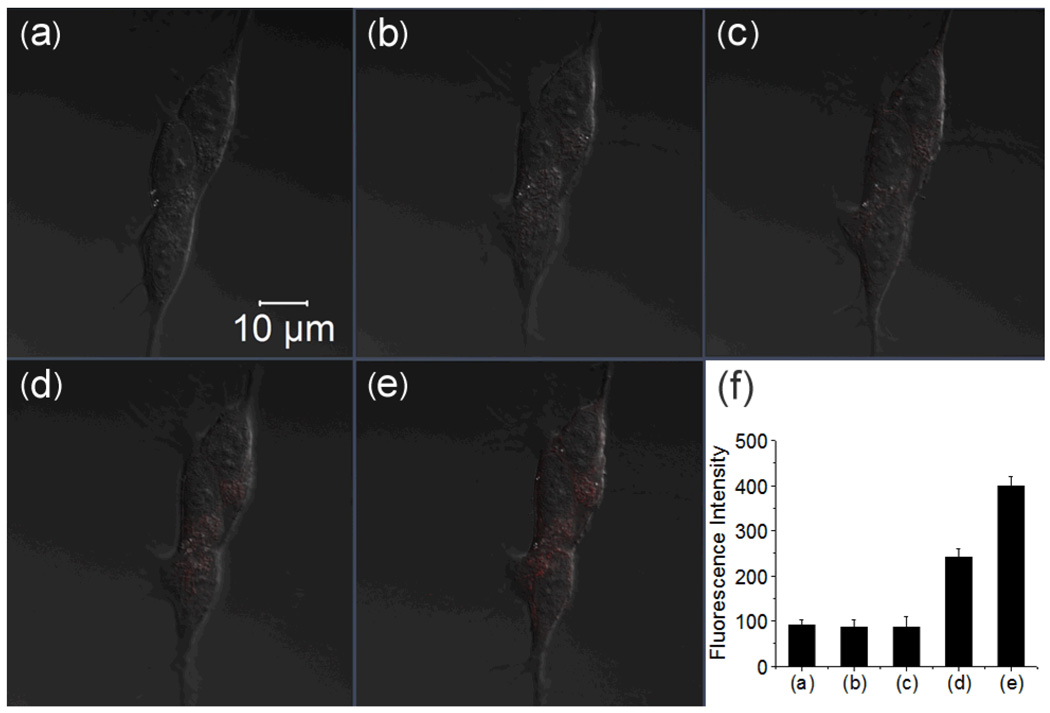

Similar experiements were performed to test the response of RS-BE with Cu2+ and H2O2 in human SH-SY5Y cells. As expected, supplement of 10 µM RS-BE and subsequent 10 µM Cu(8-HQ) or CuCl2 did not result in an intracellular fluorescent response (Fig.5(b) and (c), Fig. S10). Further addition of 100 µM H2O2 to the cells loaded with RS-BE and Cu(8-HQ) displayed a specific intracellular fluorescence enhancement (Fig. 5(d) and (e)) but with weaker intensity compared to those with Fe3+. In 60 min, only ~3.8-fold increase in intensity was observed. Little intracellular fluorescence enhancement was observed 30 min after the addition of 100 µM H2O2 to the cells preloaded with RS-BE and CuCl2 (Fig. S10). However, cells treated with higher levels of H2O2 (500 µM) and CuCl2 (50 µM) did exhibit the specific intracellular fluorescence enhancement, though still weak (Fig. S11). The weaker fluorescent response in the cells loaded with Cu2+ may be due to poor availability of free copper ions in cells.7

Fig. 5.

Confocal fluorescence images of live human SH-SY5Y cells with the treatment of RS-BE/Cu/ H2O2 (scale bar 10 µm). (a) DIC; (b) cells incubated with 10 µM RS-BE for 30 min; (c) the cells were then incubated with 10 µM Cu(8-HQ) for 30 min; (d) and (e) the cells were further treated with 100 µM H2O2 for 30 and 60 min, respectively; (f) Integrated emission (547–703 nm) intensity of (a), (b), (c), (d) and (e) images.

Taken together, we have developed a novel prochelator-type profluorescent sensor RS-BE that does not have fluorescent response to H2O2, iron or copper ions but the fluorescence can be readily “turned-on” in the presence of both H2O2 and Fe (or Cu) ions. The sensor works via a H2O2- triggered prochelator activation (from RS-BE to Rh-SBH) followed by metal-coordination-induced fluorescence activation (CIFA) mechanism, thus providing an ideal probe to monitor the “anti-Fenton” processes by a “turn-on” fluorescence process. This sensor has been demonstrated the ability to monitor the in situ presence of H2O2 and Fe (or Cu) ions (i.e. the “Fenton Reaction” conditions) in live human SH-SY5Y cells, therefore, is capable of detecting oxidative stress promoted by H2O2 and Fe (or Cu) in cellular system. However, upon being “turned on”, this sensor cannot signal the subsequent drop in H2O2 levels as the reaction of RS-BE with H2O2 to generate Rh-SBH is irreversible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth and the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. 1 R21 AT002743-02 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM)) for funding.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information(ESI) avaivable: details on synthesis, absorption, NMR and fluorescence spectra, cell culture and imaging.

Notes and References

- 1.(a) Crichton R. Inorganic Biochemistry of Iron Metabolism. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Bush AI. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:205–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zecca L, Stroppolo A, Gatti A, et al. PNAS. 2004;101:9843–9848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403495101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Perez C, Tong Y, Guo M. Curr. Bioactive Comp. 2008;4:150–158. doi: 10.2174/157340708786305952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chaston TB, Richardson DR. Am. J. Hematol. 2003;73:200–210. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Krapfenbauer K, Engidawork E, Cairns N, Fountoulakis M, Lubec G. Brain. Res. 2003;967:152–160. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Tabner BJ, Turnbull S, El-Agnaf OMA, Allsop D. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2002;32:1076–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Cooper GJS, Young AA, Gamble GD, et al. Diabetologia. 2009;52:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Wei Y, Guo M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4722–4725. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wei Y, Guo M. Chem. Commun. 2009:1413–1415. doi: 10.1039/b819204a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charkoudian LK, Pham DM, Franz KJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12424–12425. doi: 10.1021/ja064806w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiang Y, Tong A, Jin P, Yong J. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2863–2866. doi: 10.1021/ol0610340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Petrat F, Doege K, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44976–44986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel KG, Gupta P, Harbach RH, Guida WC, Dou QP. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;67:1139–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim B-E, Nevitt T, Thiele DJ. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:176–185. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.