Abstract

Tuning the electronic and steric environment of olefin metathesis catalysts with specialized ligands can adapt them to broader applications, including metathesis in aqueous solvents. Bidentate salicylaldimine ligands are known to stabilize ruthenium alkylidene complexes, as well as allow ring-closing metathesis in protic media. Here, we report the synthesis and characterization of exceptionally robust olefin metathesis catalysts bearing both bidentate salicylaldimine and N-heterocyclic carbene ligands, including a trimethylammonium-functionalized complex adapted for polar solvents. NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallographic analysis confirm the structures of the complexes. Although the N-heterocyclic carbene–salicylaldimine ligand combination limits the activity of these catalysts in nonpolar solvents, this pairing enables efficient ring-closing metathesis of both dienes and enynes in methanol and methanol–water mixtures under air.

Keywords: N-heterocyclic carbenes, metathesis, ruthenium, Schiff bases, water, X-ray diffraction

Introduction

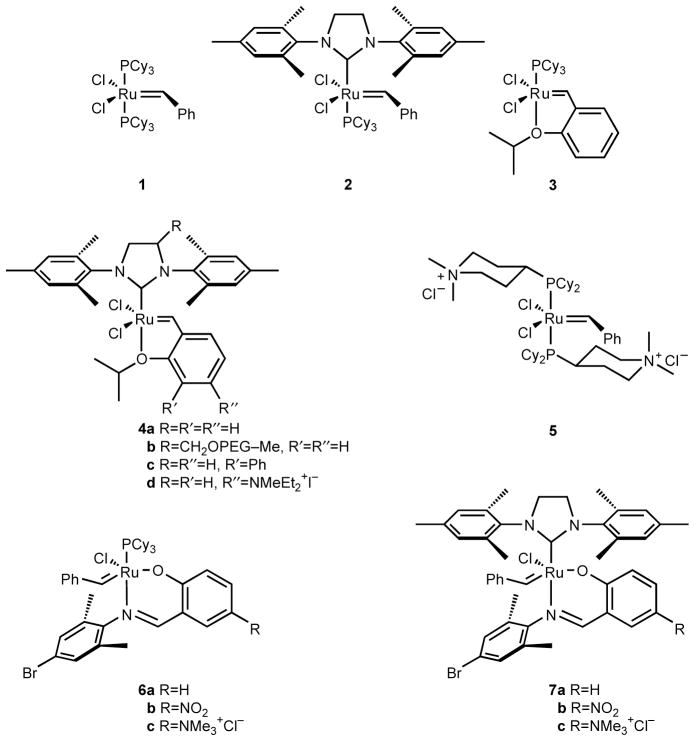

As an efficient, selective means for forming carbon–carbon bonds, olefin metathesis has revolutionized organic synthesis and polymer chemistry.[1] The high catalytic activity and functional group tolerance of well-defined ruthenium-based complexes 1–4a allow extensive use of metathesis chemistry (Figure 1).[2–5] Still more diverse utilization of metathesis necessitates catalysts tailored to specific applications.[6] For instance, aqueous olefin metathesis is attractive for carbon–carbon bond formation in biological applications[7] and green chemistry,[8,9] yet complexes 1–4a are insoluble in water and soluble versions such as 5 have proven to be unstable to air and incompatible with internal olefins.[10–12] Grubbs and coworkers have begun to address this challenge by modifying the local environment of the catalyst with a polyethylene glycol-bearing ligand, as in complex 4b.[9] Here, our intent is to complement this approach by tuning the primary coordination sphere of the catalyst to the demands of aqueous media.

Figure 1.

Olefin metathesis catalysts.

With the goal of creating designer catalysts for aqueous metathesis, we were attracted to reported ruthenium complexes containing bidentate salicylaldimine ligands, such as 6a–b and 7a–b.[13] These complexes display impressive stability and activity, and their readily accessible imine ligands lend themselves to catalyst tuning.[14] In addition, we were encouraged by the capacity of phosphine-bearing catalysts similar to 6a to perform ring-closing metathesis (RCM) in methanol.[15] Aware of the benefits that N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands provide other ruthenium metathesis catalysts, we chose to investigate salicylaldimine complexes such as 7a and b reported by Verpoort and coworkers.[16–18] According to their work, this family of NHC–imine complexes efficiently catalyzes ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP), RCM, and Kharasch addition. Imine-bearing ruthenium complexes are proposed to enter the olefin metathesis catalytic cycle with decoordination of the imine nitrogen rather than the phosphine dissociation observed for initiation of 1 and 2.[14,17] As a result, we expected that an NHC ligand such as 1,3-dimesityl-4,5-dihydroimidazol-2-ylidene (H2IMes) could beneficially replace the spectator tricyclohexylphosphine of 6a–c, leading to improved thermal stability and enhanced olefin metathesis activity.[19,20] This report details our synthesis of NHC–imine metathesis catalysts and the first crystal structure of a member of this class, complex 7a, as well as the activity of water-adapted complex 7c.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of NHC-Salicylaldimine Complexes

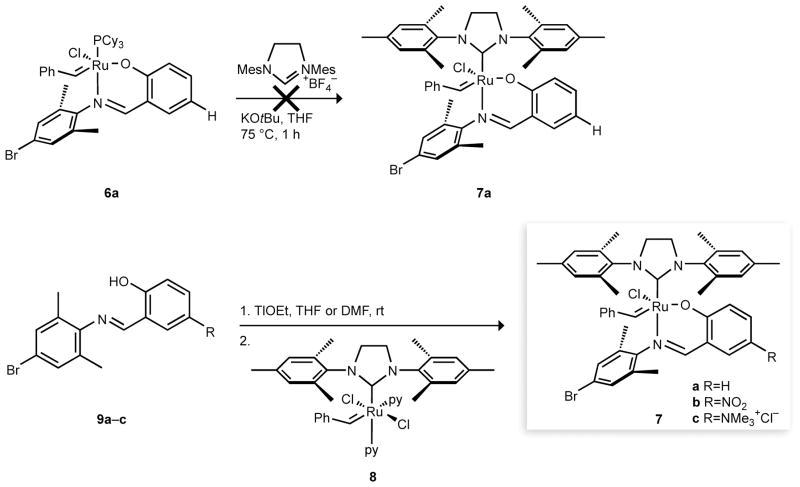

As shown in Scheme 1, our initial efforts concentrated on using the standard means for introducing the H2IMes ligand, here, in situ formation of the free carbene from the imidazolinium salt with potassium tert-butoxide and subsequent reaction with the phosphine-bearing ruthenium complex 6a.[17] Attempts to prepare reported complex 7a by this published method resulted, however, in decomposition of the ruthenium benzylidene starting material. Faced with this roadblock, we chose to approach 7a–c by introducing salicylaldimine ligands to a complex already bearing the H2IMes ligand. Alkoxide and aryloxide ligands, as well as neutral donors, react readily with bis(pyridine) precursor 8.[21] The chloride ligands in 8 are far more labile than in 2 and are displaced easily by incoming ligands, especially with the assistance of thallium ion. Accordingly, the thallium salts of salicylaldimine ligands 9a–c were prepared in situ with thallium ethoxide and reacted with 8 (Scheme 1). Gratifyingly, the green hexacoordinate starting material quickly formed wine-red complexes 7a–c as pyridine and chloride were displaced by the bidentate ligand. After the removal of thallium chloride and excess ligand, complexes 7a–c were isolated in good (56–87%) yield. Notably, this robust route even allowed access to cationic complex 7c with polar ligand 9c in DMF.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of NHC–imine complexes 7a–c by the reported route from 6a [17] and our route from 8.

Manipulation of the NHC–imine complexes 7a–c revealed their dramatic stability to air, heat, and water. These complexes tolerate storage for months as solids under vacuum without degradation as judged by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Although 2 decomposes completely in less than 1 d in C6D6 at 55 °C under air, ≥95% of complex 7b is intact after 8 d according to 1H NMR spectroscopy. Complex 7c tolerates water, and remains <40% intact after 2 d in CD3OD/D2O (3:1) under air at 20 °C (according to integration of Ar–CH3 and alkylidene 1H NMR signals). In contrast, previous catalysts bearing ligands with cationic functional groups (such as 5 [12]) decompose in minutes when exposed to traces of oxygen in solution.

Interestingly, no exchange of the alkylidene proton of complex 7c with solvent deuterons is observed in CD3OD/D2O (3:1). Such H/D exchange is observed for ruthenium alkylidene and vinylidene complexes without NHC ligands, including 5 and 6a–b,[23] but not for complex 4b.[9] Ligand electronics are known to affect the rate of alkylidene H/D exchange,[23] and the presence of the NHC ligands could slow this process.

Spectral and Structural Characterization of NHC–Salicylaldimine Complexes

1H and 13C NMR spectral data for complexes 7a–b synthesized by the route in Scheme 1 were consistent with their putative structures, but surprisingly did not match those previously reported for these complexes.[17] As listed in Table 1, the benzylidene proton resonance appears at δ 18.56 for 7a while the literature reports δ 19.42, which is nearly the same as that reported for the parent phosphine-bearing complex 6a.[14] Evidenced by 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 1–4a, replacement of the tricyclohexylphosphine ligand with H2IMes typically results in a shielding effect on the alkylidene proton that shifts its resonance approximately 0.9 ppm upfield.[2–5] In addition, the observed 1H spectrum of 7a includes eight distinct Ar–CH3 singlets, consistent with the asymmetry of the putative structure, while the literature spectrum reveals only six Ar–CH3 resonances, including an aliphatic three-proton doublet. No coalescence of the methyl resonances of 7a was observed at elevated temperature (55 °C in CDCl3 or 70 °C in C6D6). Spectra for 7b–c agree with these findings, with both complexes displaying benzylidene proton resonances about 0.9 ppm upfield from those of the parent complexes[24,15] and eight distinct methyl resonances.

Table 1.

1H NMR (CDCl3) data for 7a and related complexes.

| Compound | δ (ppm), Ru=CHAr | δ (ppm), ArCH3 |

|---|---|---|

| 7a | 18.56 (s, 1H) | 2.60 (s, 3H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 2.00 (s, 3H), 1.46 (s, 3H), 1.04 (s, 3H) |

| 7a [17] | 19.42 (s, 1H) | 2.49 (s, 6H), 2.31 (s, 3H), 2.20 (s, 6H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 1.76 (s, 3H), 1.72 (d, 3H) |

| 6a [14] | 19.45 (d, 1H) | 2.45 (q, 3H), 2.33 (s, 3H), 1.78 (d, 3H), 1.71–1.14 (m, 30H) |

| 1[a] [2] | 20.02 (s, 1H) | 2.62–1.15 (m, 66H) |

| 2[a] [4] | 19.16 (s, 1H) | 2.56–0.15 (m, 51H) |

| 3 [3] | 17.44 (d, 1H) | 2.37–1.20 (m, 33H), 1.80 (d, 6H) |

| 4a [5] | 16.56 (s, 1H) | 2.48 (s, 12H), 2.40 (s, 6H), 1.27 (d, 6H) |

CD2Cl2.

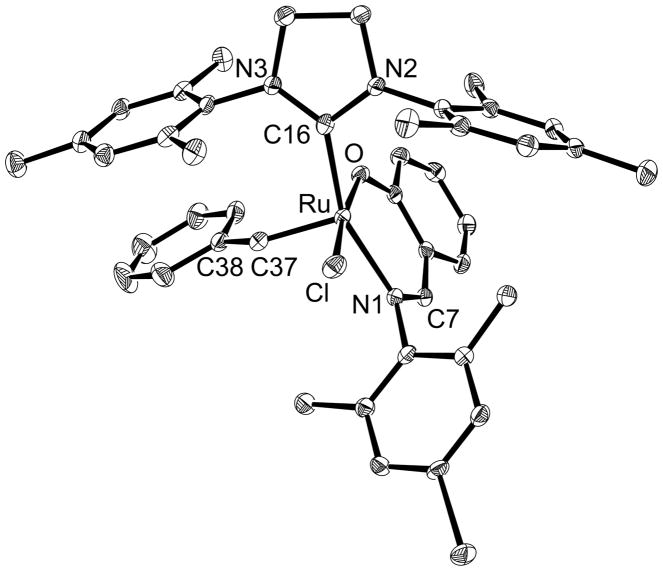

To resolve this conflict, we sought crystallographic evidence. Suitable crystals of complex 7a were grown by slow diffusion of pentane into a concentrated benzene solution over a few days. The crystalline material both displayed a 1H NMR spectrum that was indistinguishable from that of complex 7a prior to crystallization and retained RCM activity (vide infra). The X-ray data confirmed the structure of 7a, as shown in Figure 2 (see the Supporting Information for additional details). Both 7a and phosphine-bearing complexes similar to 6a–b adopt a distorted trigonal-bipyramidal geometry; the common bond lengths and angles in the two classes of complex are virtually identical.[15] As in the phosphine-bearing complexes, the anionic moieties are trans with an O–Ru–Cl bond angle of 172.5° in NHC–imine complex 7a. Just as in oxygen-ligated complex 4a,[5] the Ru–C16 bond is shorter than that in complex 2 (2.085 Å),[25] possibly reflecting the lesser trans influence of the imine ligand relative that of a phosphine.[26]

Figure 2.

Solid-state molecular structure of complex 7a. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): Ru–C37 1.838(2), Ru–C16 2.032(2), Ru–Cl 2.0530(15), Ru–O 2.1080(18), Ru–N1 2.3976(6), C16–N2 1.347(3), C16–N3 1.346(3), C7–N1 1.301(3), C37–H37 0.9500, C37–C38 1.476(3); C37–Ru–C16 98.28(9), C37–Ru–O 98.70(9), C16–Ru–N1 158.34(8), O–Ru–N1 89.40(6), C37–Ru–Cl 88.79(8), C16–Ru–O 83.79(7), C37–Ru–N1 103.07(8), C16–Ru–Cl 94.73(6), O–Ru–Cl 172.50(4), N1–Ru–Cl 89.35(5).

Synthesis of Authentic 7a by Phosphine Displacement with H2IMes

Returning to the original synthesis of complex 7a, we sought to reproduce the published results by using the improved method for introducing the H2IMes ligand reported by Nolan and coworkers.[27] Switching the reaction solvent to hexanes and the base to the more soluble potassium tert-amylate enhanced the synthesis, enabling the clean conversion of 6a to 7a as confirmed by 1H NMR. Once again, spectral characterization failed to reveal the signals of the proposed imine complex reported by De Clercq & Verpoort,[17] Although these results confirm that 7a is the authentic product of both our synthesis from H2IMes complex 8 and the preparation from 6a, the identity of the product reported previously[17] still remains unclear.

After we submitted this manuscript, Verpoort and coworkers reported the synthesis of complex 7b and three similar NHC–imine complexes by a route similar to ours.[28] These workers found the RCM activity of their NHC–imine complexes in nonpolar solvents to be similar to that of the NHC–imine complexes reported herein (vide infra). Although they confirmed the structure of these complexes by X-ray crystallographic analysis, they did not comment on the discrepancies with their earlier paper[17] nor did they examine RCM catalysis in an aqueous environment.

Ring-Closing Metathesis Activity of 7a–c

Having confirmed the structure of the NHC–imine complexes, we investigated their activity for diene RCM. In contrast to previous reports,[16] complexes 7a–c are dramatically less active in nonpolar solvents (e.g., benzene and CH2Cl2) than their phosphine-bearing counterpart, 6a (Table 2). Elevated temperatures are necessary for metathesis. Even at 55 °C, complexes 7a and 7b require 40–72 h to achieve a high conversion of most substrates in toluene or benzene, but standard complexes 2, 4a, and 4c and phosphine-bearing complexes such as 6a achieve such transformations in a few hours or less.[14,15] Cationic complex 7c shows similarly low activity in benzene, requiring 40 h for high conversions.

Table 2.

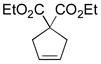

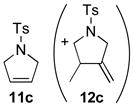

RCM of representative dienes and enynes catalyzed by ruthenium complexes under air.[a]

| Substrate | Product | Solvent (Substrate Conc. [M]) | Complex (mol%) | Time (h) | Conversion (%)[b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

10a |

11a |

CH2Cl2 (0.01) | 2 (1) | 1.5 | 99[c] |

| CH2Cl2 (0.01) | 4c (1) | 0.16 | 99[c] | ||

| C6D5Cl(0.1) | 6a (5) | 4 | 100[d] | ||

| C6D6 (0.1) | 7a (5) | 4 | 100[e] | ||

| C6D6 (0.1) | 7a (5) | 72 | 90 | ||

| C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 70 | 76 | ||

| CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 23 | 94 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7c (5) | 40 | >95 | ||

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 12 | >95 | ||

| 2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.025) | 7c (10) | 6 | 60 | ||

10b |

11b |

CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 9 | 36 |

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 9 | 34 | ||

| 2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.025) | 7c (5) | 6 | 29 | ||

10c |

|

CH2Cl2 (0.01) | 4a (1) | 4.5 | 91[f] |

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7a (5) | 6 | 8 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7a (5) | 26 | 68 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 24 | 10 | ||

| C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 6 | 43 (+ 8)[g] | ||

| C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 70 | 92 | ||

| CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 9 | >95 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7c (5) | 6 | 7 | ||

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 6 | >95 | ||

| 2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.025) | 7c (5) | 6 | 93 | ||

10d |

|

2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.05) | 7c (5) | 6 | 59 |

| 2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.025) | 7c (10) | 9 | 75 | ||

| D2O (0.2) | 4b (5) | 36 | 67 (+28)[h] | ||

10e |

11e |

CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 12 | 79 |

| 2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.025) | 7c (10) | 6 | 40 | ||

10f |

11f |

C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 40 | 45 |

| CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 9 | 94 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7c (5) | 40 | 65 | ||

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 9 | >95 | ||

| 2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.025) | 7c (5) | 6 | 57 | ||

10g |

11g |

C7D8 (0.05) | 7a (5) | 70 | 41 |

| C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 40 | 10 | ||

| CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 9 | <5 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7c (5) | 40 | 77 | ||

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 9 | <5 | ||

10h |

11h |

C7D8 (0.05) | 7a (5) | 40 | >95 |

| C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 40 | >95 | ||

| CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 5 | 95 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7c (5) | 40 | >95 | ||

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 7 | >95 | ||

| 2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.025) | 7c (5) | 6 | 85 | ||

10i |

11i |

C7D8 (0.05) | 7a (5) | 40 | 90 |

| C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 40 | 90 | ||

| CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 9 | 93 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7c (5) | 40 | 89 | ||

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 7 | >95 | ||

| 2:1 CD3OD/D2O (0.025) | 7c (10) | 6 | >95 | ||

10j |

11j |

C7D8 (0.05) | 7a (5) | 36 | 7 |

| C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 36 | 7 | ||

| CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 36 | 25 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7c (5) | 36 | 42 | ||

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 36 | 32 | ||

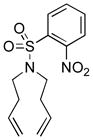

10k |

11k |

C7D8 (0.05) | 7a (5) | 36 | 93 |

| C7D8 (0.05) | 7b (5) | 18 | >95 | ||

| CD3OD(0.025) | 7b (5) | 2 | 90 | ||

| C6D6 (0.05) | 7c (5) | 5 | >95 | ||

| CD3OD(0.05) | 7c (5) | 2 | >95 | ||

| 5:2 CD3OD/D2O (0.02) | 7c (10) | 6 | >95 | ||

| 5:2 CH3OH/H2O (0.02) | 4d (5) | 0.5 | 92[i] | ||

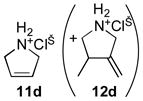

Yet, under similar conditions in methanol, complexes 7b and 7c catalyze the complete ring-closing of both polar and nonpolar substrates to form five-, six-, and seven-membered cyclic products in only 6–12 h. Although complex 7b is less soluble in methanol than complex 7c, these two catalysts display similar activity, demonstrating that the trimethylammonium substituent influences solubility more than reactivity. Unlike other metathesis catalysts adapted to protic solvents, complex 7c does not require inert atmosphere conditions for catalysis of RCM. In addition, complex 7c is effective for RCM of N,N-dimethyl-N,N-diallylammonium chloride (10e), which has proven to be recalcitrant for other catalysts.[29,30] This specialized catalyst is also active in methanol–water mixtures, with 10 mol% of 7c achieving the highest conversion of N,N-diallylamine hydrochloride (10d) to RCM product 11d yet reported in an aqueous environment.[9,11,30–32] Moreover, 7c accomplishes this transformation cleanly. For comparison, Grubbs and coworkers reported 67% ring-closing of 10d along with 28% conversion to cycloisomer 12d using 5 mol% of complex 4b in water at room temperature over 36 h.[9] With a variety of nonpolar dienes 7c also achieves good to excellent conversions to five-, six-, and seven-membered rings in methanol–water mixtures. In contrast to RCM with complexes 7a–c in nonpolar solvents or methanol, RCM in the aqueous environment is limited by decomposition of the catalyst or intermediates—in the former solvents the intact complex is observable by NMR spectroscopy throughout the timecourse of the reaction, but in methanol–water the resonances of the complex disappear.

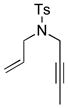

Enyne metathesis by salicylaldimine alkylidene ruthenium complexes has not been reported previously. We found that complexes 7a–c are efficient catalysts of enyne RCM. Substrate 10k is smoothly transformed in nonpolar solvents (5–36 h) and in protic media (2–6 h). For comparison, Grela and coworkers recently reported metathesis of 10k with complex 4d in 92% conversion in an aqueous solvent.[33] With 7a–c, the more difficult substrate 10j also undergoes ring closure to a moderate extent.

The solvent dependence of ring-closing metathesis with the NHC–imine complexes offers an explanation for their low activity. Catalysts bearing the H2IMes ligand are typically more active in aromatic solvent than in CH2Cl2.[34] In contrast, complex 7b is more active in more polar solvents (Table 3). This solvent dependence is consistent with the initiation rate trend for catalysis by 2, wherein switching from toluene to CH2Cl2 increased the initiation rate by 30%.[20] Together, these data suggest that the activity of NHC–imine complexes 7a–c is limited by their rate of initiation. Direct observations of metathesis reaction mixtures by 1H NMR also support this conclusion. For both NHC–imine catalysts and several other chelated catalysts,[35] propagating alkylidene species are not detected during metathesis, and, in nonpolar solvents, the 1H NMR signals for the complexes are typically unchanged upon completion. These results imply that the ligand combination in 7a–c allows only a small fraction of the complex species to participate in metathesis. Although NHC ligands improve metathesis propagation activities for ruthenium complexes, they tend to decrease their initiation rates drastically.[20] Switching from a tricyclohexylphosphine spectator ligand to an NHC could likewise decrease the initiation rate for imine complexes, such that they remain largely dormant as 16-electron species.[20] Increasing the temperature and solvent polarity apparently enables the complexes to surmount this hurdle, resulting in the high RCM activity of 7b–c in a polar solvent. Thus, ruthenium NHC–imine complexes are rare examples of complexes that are more active as metathesis catalysts in methanol than in nonpolar solvents.[31]

Table 3.

Solvent dependence of RCM of N-tosyl diallylamine (10c) catalyzed by complex 7b.[a]

| Solvent | Dielectric constant (ε) | Conversion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| C6D6 | 2.28 | 14 |

| CD2Cl2 | 8.9 | 36 |

| CD3OD | 32.6 | 69 |

Reaction conditions: 5 mol% 7b, 0.025 M substrate 10c, 40 °C, 24 h, under air.

These characteristics of high stability and slow initiation suit salicylaldimine-based catalysts to specific applications. For example, complexes 7b–c could enable ROMP in protic media, though their slow initiation rates are likely to result in large polydispersities that could be inappropriate for some applications.[36] Similarly, the low concentrations of propagating alkylidene species produced by salicylaldimine catalysts prevent them from supporting cross-metathesis. Nonetheless, these same qualities make NHC–salicylaldimine catalysts promising for RCM in aqueous environments. Slow initiation appears to protect the complex from water while providing a steady supply of active species with which to accomplish RCM. These advantages could be combined with the protective local environment provided by polyethylene glycol-functionalized ligands[9] to provide even more efficient catalysts for aqueous RCM.

Conclusion

Specialized ligands can tune the characteristics of olefin metathesis catalysts, adapting them to demanding applications, including metathesis in aqueous environments. We prepared ruthenium complexes bearing both NHC and salicylaldimine ligands, and confirmed their structure by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallographic analysis. These new complexes initiate slowly, but are highly effective catalysts for diene and enyne RCM in protic media. The enhanced stability engendered by the salicylaldimine ligands allows trimethylammonium-functionalized complex 7c to achieve clean RCM of N,N-diallylamine hydrochloride (10d) with the highest conversion yet reported in an aqueous environment. Further investigations will address the potential of these catalysts for RCM of more complex substrates as well as the possible enhancement of salicylaldimine-based catalysts with polyethylene glycol-bearing ligands.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

Commercial chemicals were of reagent grade or better, and were used without further purification. Anhydrous THF, DMF, and CH2Cl2 were obtained from CYCLE-TAINER® solvent delivery systems (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ). Other anhydrous solvents were obtained in septum-sealed bottles. In all reactions involving anhydrous solvents, glassware was either oven-or flame-dried. Manipulation of organometallic compounds was performed using standard Schlenk techniques under an atmosphere of dry Ar(g), except as noted otherwise.

The term “concentrated under reduced pressure” refers to the removal of solvents and other volatile materials using a rotary evaporator at water aspirator pressure (<20 torr) while maintaining the water-bath temperature below 40 °C. In other cases, solvent was removed from samples at high vacuum (<0.1 torr). The term “high vacuum” refers to vacuum achieved by a mechanical belt-drive oil pump.

NMR spectra were acquired with a Bruker DMX-400 Avance spectrometer (1H, 400 MHz; 13C, 100.6 MHz), Bruker Avance DMX-500 spectrometer (1H, 500 MHz; 13C, 125.7 MHz), or Bruker Avance DMX-600 spectrometer (1H, 600 MHz) at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison (NMRFAM). NMR spectra were obtained at ambient temperature unless indicated otherwise. Coupling constants J are given in Hertz.

Mass spectrometry was performed with a Micromass LCT (electrospray ionization, ESI) in the Mass Spectrometry Facility in the Department of Chemistry. Elemental analyses were performed at Midwest Microlabs (Indianapolis, IN).

N-(4-Bromo-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-salicylaldimine (9a), N-(4-bromo-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-5-nitrosalicylaldimine (9b), and ruthenium imine complex 6a were prepared according to the methods of De Clercq & Verpoort.[14] (3-Formyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)-trimethylammonium iodide was prepared according to the method of Ando & Emoto[37] and converted to the chloride salt by anion exchange. (H2IMes)(C5H5N)2(Cl)2Ru=CHPh (8) was synthesized by the method of Grubbs and coworkers.[21]

The following RCM substrates were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification: diethyl diallylmalonate (10a), N,N-diallyl-2,2,2-trifluoroacetamide (10b), allyl ether (10f), and 1,7-octadiene (10h) from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI); N,N-diallyl-N,N-dimethylammonium chloride (10e) from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland); and diallyldiphenylsilane (10g) from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium).

N,N-Diallyl-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide (10c) was prepared by the method of Lamaty and coworkers.[38] Diallylamine hydrochloride (10d) was prepared from the corresponding amine (Aldrich) by treatment with ethereal HCl. N-(2-Propenyl)-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide was prepared by the method of Pagenkopf and coworkers.[39]

Preparation of N-(4-Bromo-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-5-trimethylammoniumsalicylaldimine Chloride (9c)

4-Bromo-2,6-dimethylaniline (1.003 g, 5.02 mmol) and (3-formyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)-trimethylammonium chloride (1.082 g, 5.02 mmol) were dissolved in ethanol (25 mL), and the resulting solution was stirred at reflux for 16 h. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was treated with hexanes (15 mL), removed by filtration, and dried under high vacuum to afford 9c (1.544 g, 3.88 mmol, 77% yield) as a yellow powder. 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ: 8.61 (s, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (s, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (s, 9H), 2.18 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ: 168.5, 163.0, 148.4, 140.1, 132.2, 131.9, 126.3, 125.6, 120.4, 120.0, 119.3, 58.2, 18.5. HRMS–ESI (m/z): [M–Cl]+ calcd for C18H22BrN2O, 361.0916; found 361.0906.

Preparation of NHC–Imine Complex 7a

N-(4-Bromo-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-salicylaldimine 9a (60 mg, 197 μmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (5 mL). Thallium(I) ethoxide (14 μL, 197 μmol) was added to this solution, and the resulting yellow mixture was stirred for 1.5 h. The green complex 8 (114 mg, 158 μmol) was added as a solid, resulting in a rapid color change of the solution from yellow to red. After 1.5 h, the solvent was removed by high vacuum. The residue was dissolved in benzene (5 mL), and the resulting solution was filtered through a glass wool plug to remove the thallium chloride byproduct. The solvent was removed under high vacuum, and pentane (10 mL) was added to the residue to make a slurry. The red solid was removed by filtration, washed with pentane (3 × 5 mL), and dried under high vacuum to afford 7a (101 mg, 121 μmol, 76% yield) as a red powder. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained by layering pentane over a solution of 7a in benzene. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2) δ: 18.47 (s, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.01–6.95 (m, 6H), 6.91 (s, 1H), 6.77 (s, 1H), 6.48 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 4.14–3.94 (m, 4H), 2.56 (s, 3H), 2.44 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 2.11 (s, 3H), 1.97 (s, 3H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (CD2Cl2) δ: 298.7, 220.7, 170.3, 167.5, 152.2, 151.7, 140.2, 139.5, 138.2, 137.6, 137.4, 137.0, 136.9, 135.1, 134.3, 132.7, 129.6, 129.4, 128.6, 128.2, 123.8, 119.1, 117.7, 114.0, 51.8, 51.2, 21.1, 21.0, 20.1, 18.8, 18.3, 18.2, 17.9, 17.8. HRMS–ESI (m/z): [M]+ calcd for C43H45BrClN3ORu, 829.1511; found 829.1517. Anal. Calc. for C43H45BrClN3ORu: C, 61.76; H, 5.42; N, 5.02. Found: C, 61.70; H, 5.43; N, 4.90.

Preparation of NHC–Imine Complex 7b

Complex 7b was prepared in 79% yield from 9b and 8 by using a procedure similar to that for the preparation of 7a. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2) δ: 18.43 (s, 1H), 8.06 (dd, J = 9.4 Hz, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (s, 1H), 7.49 (b, 2H), 7.40 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.07–7.00 (m, 4H), 6.96 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 6.76 (s, 1H), 6.42 (s, 1H), 6.37 (s, 1H), 4.17–3.96 (m, 4H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.34 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.45 (s, 3H), 1.04 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (CD2Cl2) δ: 297.2, 214.4, 170.2, 163.0, 147.4, 146.0, 135.6, 134.9, 134.4, 134.0, 133.1, 132.4, 131.9, 131.1, 130.6, 129.9, 129.1, 127.5, 125.9, 125.2, 125.1, 125.0, 124.9, 124.8, 123.8, 123.5, 119.6, 113.8, 113.6, 47.2, 46.6, 16.4, 16.3, 15.4, 14.3, 13.7, 13.5, 13.3, 13.1. HRMS–ESI (m/z): [M]+ calcd for C43H44BrClN4O3Ru, 874.1361; found 874.1324.

Preparation of NHC–Imine Complex 7c

N-(4-Bromo-2,6-dimethylphenyl)-5-trimethylammoniumsalicylaldimine chloride 9c (71 mg, 180 μmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMF (3 mL). Thallium(I) ethoxide (12.7 μL, 180 μmol) was added to the solution, and the resulting yellow mixture was stirred for 1 h. The green complex 8 (119 mg, 164 μmol) was added to this mixture as a solution in THF (0.5 mL), resulting in a rapid color change from yellow to red. After 1 h the solvent was removed under high vacuum. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (20 mL), and the resulting solution was filtered to remove the thallium chloride byproduct. Subsequent manipulations were performed under air with reagent-grade solvents. The filtrate was washed twice with deionized water (20 mL) and once with brine (20 mL), and the organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (1 mL), and the resulting solution was transferred into pentane (20 mL) to precipitate a red-brown solid. The precipitate was removed by filtration, washed with pentane (10 mL), and dried under high vacuum to yield 7c (132 mg, 142 μmol, 87% yield) as a red-brown powder. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2) δ: 18.37 (s, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.46–7.59 (m, 3H), 7.38 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (m, 4H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.78 (s, 1H), 6.44 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 1H), 3.94–4.16 (m, 4H), 3.79 (s, 9H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 2.44 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.26 (s, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 1.97 (s, 3H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (CD2Cl2) δ: 300.7, 219.4, 170.3, 166.9, 152.1, 151.0, 140.3, 139.3, 139.2, 138.5, 137.7, 137.1, 136.7, 134.6, 134.1, 133.7, 132.2, 130.6, 130.5, 129.8, 129.7, 129.4, 129.3, 128.4, 127.6, 126.1, 124.9, 118.3, 118.0, 58.4, 51.8, 51.3, 21.1, 21.0, 20.0, 18.8, 18.3, 18.1, 18.0, 17.9. HRMS–ESI (m/z): [M–Cl]+ calcd for C46H53BrClN4ORu, 887.2167; found 887.2125.

Preparation of N,N-Di-3-butenyl-2-nitrobenzenesulfonamide (10i)

A procedure from the literature[40] was modified as follows. 2-Nitrobenzenesulfonamide (1.01 g, 5.00 mmol) and 4-bromo-1-butene (4.05 g, 30.0 mmol) were dissolved in acetone (25 mL), and potassium carbonate (1.73 g, 12.5 mmol) was added to this solution. The resulting mixture was stirred for 5 d. After filtration, the reaction mixture was acidified with formic acid until no additional evolution of CO2(g) was observed, and then concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in EtOAc, washed once with 1 M HCl (50 mL), twice with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (50 mL), and once with brine (50 mL). The organic layer was dried with MgSO4(s) and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography (20% EtOAc v/v in hexane) to afford 10i (180 mg, 0.580 mmol, 11.6%) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 8.07–8.01 (m, 1H), 7.72–7.61 (m, 3H), 5.77–5.64 (m, 2H), 5.13–4.98 (m, 4H), 3.39 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 2.31 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ: 148.2, 134.3, 133.9, 133.6, 131.8, 131.0, 124.3, 117.6, 46.9, 32.8. HRMS–ESI (m/z): [M+Na]+ calcd for C14H18N2O4SNa, 333.0885; found 333.0891.

Preparation of N-(2-Propenyl)-N-(2-butynyl)-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide (10j)

Following the procedure of Pagenkopf and coworkers,[39] N-(2-propenyl)-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide (2.00 g, 9.51 mmol), 1-bromo-2-butyne (3.79 g, 28.5 mmol), and potassium carbonate (1.58 g, 11.41 mmol) yielded 10j (1.15 g, 4.36 mmol, 46%) as a yellow oil following silica gel flash chromatography (10% EtOAc v/v in hexane). 1H NMR data were in agreement with those reported by Buchwald and coworkers.[41]

Preparation of Allyl 1,1-Diphenylpropargyl Ether (10k)

Allyl 1,1-diphenylpropargyl ether was prepared by the method of Dixneuf and coworkers.[42] Rf = 0.52 (silica gel, 5% EtOAc v/v in hexane). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.58 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 7.30 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 7.23 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.05–5.93 (m, 1H), 5.36 (d, J = 17.5, 1H), 5.16 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 4.04 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 2.86 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ: 143.3, 134.9, 128.4, 127.9, 126.7, 116.3, 83.4, 80.2, 77.8, 66.1. HRMS–ESI (m/z): [M+Na]+ calcd for C18H16ONa, 271.1099; found 271.1106.

Representative Procedure for RCM Reactions

On the benchtop under air, the ruthenium complex 7a (1.6 mg, 1.9 μmol) was dissolved in non-distilled, non-degassed C6D6 (0.75 mL) in an NMR tube, and substrate 10c (8.1 μL, 38 μmol) was added to this solution. The tube was capped, wrapped with parafilm, shaken, and placed in a temperature-controlled water bath at 55 °C. Product formation was monitored by 1H NMR integration of the allylic methylene signals.

Alternative Preparation of NHC–Imine Complex 7a

A flame-dried Schlenk flask was charged with 1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)-4,5-dihydroimidazolium tetrafluoroborate (12.2 mg, 30.9 μmol) and anhydrous hexanes (5 mL). After the addition of 1.7 M potassium t-amylate in toluene (18.2 μL, 30.9 μmol), the suspension was stirred for 5 min. Complex 6a (5.0 mg, 6.2 μmol) was added as a solid, and the resulting reddish mixture was heated to 75 °C for 1 h, after which the solvent was removed under high vacuum. The crude product was analyzed by 1H NMR in CD2Cl2.

Structure Determination of NHC–Imine Complex 7a

A red crystal of complex 7a with approximate dimensions 0.36 × 0.31 × 0.30 mm3 was selected under oil under ambient conditions and attached to the tip of a nylon loop. The crystal was mounted in a stream of cold N2(g) at 100(2) K and centered in the X-ray beam by using a video camera.

The crystal evaluation and data collection were performed on a Bruker CCD-1000 diffractometer with Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) radiation and a diffractometer to crystal distance of 4.9 cm.

The initial cell constants were obtained from three series of ω scans at different starting angles. Each series consisted of 20 frames collected at intervals of 0.3° in a 6° range about ω with the exposure time of 15 s per frame. A total of 141 reflections was obtained. The reflections were indexed successfully with an automated indexing routine built in the SMART program. The final cell constants were calculated from a set of 13907 strong reflections from the actual data collection.

Diffraction data were collected by using the hemisphere data collection routine. The reciprocal space was surveyed to the extent of a full sphere to a resolution of 0.80 Å. A total of 27059 data were harvested by collecting three sets of frames with 0.3° scans in ω and ϕ with an exposure time 45 s per frame. These highly redundant datasets were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects. The absorption correction was based on fitting a function to the empirical transmission surface as sampled by multiple equivalent measurements.[43]

The systematic absences in the diffraction data were consistent for the space groups P1̄ and P1. The E-statistics strongly suggested the centrosymmetric space group P1̄ that yielded chemically reasonable and computationally stable results of refinement.[43]

A successful solution by the direct methods provided most non-hydrogen atoms from the E-map. The remaining non-hydrogen atoms were located in an alternating series of least-squares cycles and difference Fourier maps. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement coefficients. All hydrogen atoms were included in the structure factor calculation at idealized positions and were allowed to ride on the neighboring atoms with relative isotropic displacement coefficients.

The final least-squares refinement of 459 parameters against 7597 data resulted in residuals R (based on F2 for I ≥ 2σ) and wR (based on F2 for all data) of 0.0262 and 0.0739, respectively. The final difference Fourier map was featureless.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to H. E. Blackwell, L. L. Kiessling, D. M. Lynn, and M. Kim for contributive discussions. J.B.B. was supported by an NDSEG Fellowship sponsored by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. This work was supported by grant GM44783 (NIH). NMRFAM was supported by grant P41RR02301 (NIH).

References

- 1.For reviews, see: Grubbs RH, editor. Handbook of Metathesis. 1–3. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2003. Nicolaou KC, Bulger PG, Sarlah D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4490–4527. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500369.Grubbs RH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3760–3765. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600680.

- 2.Schwab P, Grubbs RH, Ziller JW. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingsbury JS, Harrity JPA, Bonitatebus PJ, Jr, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:791–799. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholl M, Ding S, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. Org Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garber SB, Kingsbury JS, Gray BL, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:8168–8179. [Google Scholar]

- 6.For a recent notable example, see: Bieniek M, Bujok R, Cabaj M, Lugan N, Lavigne G, Arlt D, Grela K. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13652–13653. doi: 10.1021/ja063186w.

- 7.For examples, see: Mortell KH, Gingras M, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:12053–12054.Miller SJ, Blackwell HE, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9606–9614.Kiessling LL, Strong LE. Top Organomet Chem. 1998;1:199–231.Leeuwenburgh MA, van der Marel GA, Overkleeft HS. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:757–765. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.10.009.Agrofoglio LA, Nolan SP. Curr Top Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2005;5:1541–1558. doi: 10.2174/156802605775009739.Gaich T, Mulzer J. Curr Top Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2005;5:1473–1494. doi: 10.2174/156802605775009793.Jenkins CL, Vasbinder MM, Miller SJ, Raines RT. Org Lett. 2005;7:2619–2622. doi: 10.1021/ol050780m.Martin WHC, Blechert S. Curr Top Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2005;5:1521–1540. doi: 10.2174/156802605775009757.Prunet J. Curr Top Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2005;5:1559–1577. doi: 10.2174/156802605775009801.Stymiest JL, Mitchell BF, Wong S, Vederas JC. J Org Chem. 2005;70:7799–7809. doi: 10.1021/jo050539l.Van de Weghe P, Eustache J. Curr Top Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2005;5:1495–1519. doi: 10.2174/156802605775009748.Van de Weghe P, Eustache J, Cossy J. Curr Top Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2005;5:1461–1472. doi: 10.2174/156802605775009784.

- 8.a) Streck R. J Mol Catal. 1992;76:359–372. [Google Scholar]; b) Yao Q, Zhang Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:3395–3398. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cornils B, Herrmann WA, editors. Aqueous-Phase Organometallic Catalysis. 2. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong SH, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3508–3509. doi: 10.1021/ja058451c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohr B, Lynn DM, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 1996;15:4317–4325. [Google Scholar]; Gallivan JP, Jordan JP, Grubbs RH. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:2577–2580. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkland TA, Lynn DM, Grubbs RH. J Org Chem. 1998;63:9904–9909. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynn DM, Mohr B, Grubbs RH, Henling LM, Day MW. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6601–6609. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Drozdzak R, Allaert B, Ledoux N, Dragutan I, Dragutan V, Verpoort F. Adv Synth Catal. 2005;347:1721–1743. [Google Scholar]; b) Drozdzak R, Allaert B, Ledoux N, Dragutan I, Dragutan V, Verpoort F. Coord Chem Rev. 2005;249:3055–3074. [Google Scholar]; c) Drozdzak R, Ledoux N, Allaert B, Dragutan I, Dragutan V, Verpoort F. Cent Eur J Chem. 2005;3:404–416. [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Clercq B, Verpoort F. Adv Synth Catal. 2002;344:639–648. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang S, Jones L, II, Wang C, Henling LM, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 1998;17:3460–3465. [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Clercq B, Verpoort F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:9101–9104. [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Clercq B, Verpoort F. J Organomet Chem. 2003;672:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opstal T, Verpoort F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:2876–2879. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J, Stevens ED, Nolan SP, Petersen JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2674–2678. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanford MS, Love JA, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6543–6554. doi: 10.1021/ja010624k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanford MS, Love JA, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2001;20:5314–5318. [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Conrad JC, Amoroso D, Czechura P, Yap GPA, Fogg DE. Organometallics. 2003;22:3634–3636. [Google Scholar]; b) Conrad JC, Parnas HH, Snelgrove JL, Fogg DE. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11882–11883. doi: 10.1021/ja042736s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Conrad JC, Camm KD, Fogg DE. Inorg Chim Acta. 2006;359:1967–1973. [Google Scholar]; d) Monfette S, Fogg DE. Organometallics. 2006;25:1940–1944. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynn DM, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3187–3193. doi: 10.1021/ja0020299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Binder JB, Raines RT. unpublished results. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Love JA, Sanford MS, Day MW, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10103–10109. doi: 10.1021/ja027472t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartley FR. Chem Soc Rev. 1973;2:163–179. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jafarpour L, Hillier AC, Nolan SP. Organometallics. 2002;21:442–444. [Google Scholar]

- 28.a) Allaert B, Dieltiens N, Ledoux N, Vercaemst C, Van Der Voort P, Stevens CV, Linden A, Verpoort F. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 2006;260:221–226. [Google Scholar]; b) Ledoux N, Allaert B, Schaubroeck D, Monsaert S, Drozdzak R, Van Der Voort P, Verpoort F. J Organomet Chem. 2006;691:5482–5486. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynn DM. PhD thesis. California Institute of Technology; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter F, De Clercq B. 2005043541. US Patent App. 2005

- 31.Connon SJ, Blechert S. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:1873–1876. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hahn FE, Paas M, Froehlich R. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:5816–5821. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michrowska A, Gulajski L, Kaczmarska Z, Mennecke K, Kirschning A, Grela K. Green Chem. 2006;8:685–688. [Google Scholar]

- 34.a) Fuerstner A, Thiel OR, Ackermann L, Schanz HJ, Nolan SP. J Org Chem. 2000;65:2204–2207. doi: 10.1021/jo9918504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Furstner A, Ackermann L, Gabor B, Goddard R, Lehmann CW, Mynott R, Stelzer F, Thiel OR. Chem-Eur J. 2001;7:3236–3253. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010803)7:15<3236::aid-chem3236>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanford MS, Henling LM, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 1998;17:5384–5389. [Google Scholar]

- 36.a) Cairo CW, Gestwicki JE, Kanai M, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1615–1619. doi: 10.1021/ja016727k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gestwicki JE, Cairo CW, Strong LE, Oetjen KA, Kiessling LL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14922–14933. doi: 10.1021/ja027184x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2348–2368. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ando M, Emoto S. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1978;51:2433–2434. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varray S, Lazaro R, Martinez J, Lamaty F. Organometallics. 2003;22:2426–2435. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel MC, Livinghouse T, Pagenkopf BL. Org Synth. 2003;80:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Handa S, Kachala MS, Lowe SR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:253–256. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sturla SJ, Buchwald SL. J Org Chem. 1999:64. doi: 10.1021/jo990384f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le Paih J, Rodriguez DC, Derien S, Dixneuf PH. Synlett. 2000:95–97. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruker–AXS. SADABS V.2.05, SAINT V.6.22, SHELXTL V.6.10 & SMART 5.622 Software Reference Manuals. Bruker–AXS; Madison, WI, USA: 2000–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakamatsu H, Blechert S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2403–2405. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020703)41:13<2403::AID-ANIE2403>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaja M, Connon SJ, Dunne AM, Rivard M, Buschmann N, Jiricek J, Blechert S. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:6545–6558. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.