Abstract

Muscle atrophy is a consequence of chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes) and glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance that results from enhanced activity of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The PI3K/Akt pathway inhibits the FOXO-mediated transcription of the muscle-specific E3 ligase atrogin-1/MAFbx (AT-1), whereas the MEK/ERK pathway increases Sp1 activity and ubiquitin (UbC) expression. The observations raise a question about how the transcription of these atrogenes is synchronized in atrophic muscle. We tested a signaling model in which FOXO3a mediates crosstalk between the PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways to coordinate AT-1 and UbC expression. In rat L6 myotubes, dexamethasone (≥24 h) reduced insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 protein and PI3K/Akt signaling and increased AT-1 mRNA. IRS-2 protein, MEK/ERK signaling, Sp1 phosphorylation, and UbC transcription were simultaneously increased. Knockdown of IRS-1 using small interfering RNA or adenovirus-mediated expression of constitutively activated FOXO3a increased IRS-2 protein, MEK/ERK signaling, and UbC expression. Changes in PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK signaling were recapitulated in rat muscles undergoing atrophy due to streptozotocin-induced insulin deficiency and concurrently elevated glucocorticoid production. IRS-1 and Akt phosphorylation were decreased, whereas MEK/ERK signaling and expression of IRS-2, UbC and AT-1 were increased. We conclude that FOXO3a mediates a reciprocal communication between the IRS-1/PI3K/Akt and IRS-2/MEK/ERK pathways that coordinates AT-1 and ubiquitin expression during muscle atrophy.—Zheng, B., Ohkawa, S., Li, H., Roberts-Wilson, T.-K., Price, S. R. FOXO3a mediates signaling crosstalk that coordinates ubiquitin and atrogin-1/MAFbx expression during glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy.

Keywords: diabetes, transcription

Muscle atrophy is a consequence of disuse, chronic illnesses, and glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance that decreases patients’ quality of life and increases their risks of mortality. The loss of muscle proteins results largely from the activation of proteolytic systems including the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Augmented activity of this pathway has been associated with increased expression of a number of pathway components including ubiquitin, E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzymes, and muscle-specific E3 ligases [e.g., atrogin-1/MAFbx (AT-1) and MuRF1].

Glucocorticoids play a permissive role in the atrophy process. Administration of the steroid receptor antagonist RU486 or adrenalectomy attenuated the atrophy process in a number of experimental animal models (1,2,3). Conversely, giving rats catabolic doses of glucocorticoids [e.g., dexamethasone (DEX)] increased the protein degradation rate, ubiquitin conjugation, and proteoytic activities associated with proteasome in skeletal muscle (4,5,6). At least some of these changes have been ascribed to increased expression of genes in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (4, 6,7,8,9,10). In most cases, the mechanisms by which glucocorticoids enhanced the transcription of these targets differed and did not involve a traditional glucocorticoid response element. For the C3 proteasome subunit, glucocorticoids repressed the binding of a NF-κB Rel A-containing protein complex to the C3 subunit promoter region (8). In this case, NF-κB acted as a transcriptional repressor, a function that seems contradictory to the effects of NF-κB on other atrogenes (e.g., MuRF1; ref. 11). For AT-1 and MuRF1, glucocorticoids activated the FOXO (i.e., FOXO1 and FOXO3) transcription factors by reducing the activity of Akt (7, 10). Lastly, glucocorticoids increased ubiquitin C (UbC) gene expression by a mechanism that involved the MEK/ERK pathway and Sp1 (9). Notably, the UbC response did not occur in cell types other than muscle (12).

Reduced IGF-1/insulin signaling resulting from either a deficiency of hormone production (e.g., type I diabetes) or defective signaling at the receptor or postreceptor level (e.g., type II diabetes, sepsis) is frequently observed in systemic conditions linked to muscle atrophy. It is well established that glucocorticoids antagonize the actions of insulin and IGF-1, in part, by reducing PI3K/Akt signaling. Hu et al.(13) reported that the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) decreased PI3K activity in skeletal muscle through a direct inhibitory interaction between the PI3K p85 regulatory subunit and the GR. In an unrelated study (14), GR number and binding affinity were increased in skeletal muscles of septic rats (which require glucocorticoids for atrophy). Others (15, 16) reported that treating rats with high doses of glucocorticoids led to a reduction in insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 protein but the effects on tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor and IRS-1 were inconsistent. Finally, treatment of L6 myotubes selectively increased the amount of the PI3K p85 subunit without a corresponding increase in the p110 PI3K catalytic subunit (17). The response was suggested to inhibit PI3K activity by increasing the binding competition between the free p85 subunit and the PI3K holocomplex (i.e., p85/p110 subunits) to phosphorylated (i.e., activated) IRS-1.

We previously reported that the glucocorticoid-induced increase in UbC transcription was prevented by inhibiting MEK1/2 and, surprisingly, Sp1 was identified as the transcription factor that mediated the response (9). The mechanism by which glucocorticoids activated MEK and Sp1 was not defined. Since hormones like insulin and IGF-1 activate both the PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways as well suppress muscle proteolysis, these findings seem paradoxical. How can such disparate findings be reconciled? Given the parallel nature of the PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways, we hypothesized that inhibition of the PI3K pathway by glucocorticoids might produce a reciprocal change in MEK/ERK signaling by an unknown crosstalk mechanism. Based on this hypothetical model, glucocorticoids should act indirectly, rather than directly, to activate the MEK/ERK system and increase UbC transcription. Therefore, we investigated the induction mechanism for the MEK/ERK pathway and evaluated whether FOXO3a activation is sufficient to increase UbC expression. We also confirmed that glucocorticoid-mediated changes in PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK signaling occur in the muscles of rats with acute streptozotocin (STZ)-induced insulinopenia, a model of muscle atrophy that involves increased glucocorticoid production (18, 19).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Polyclonal antibodies were from commercial sources as indicated: MEK1/2, pMEK1/2 (pSer217/221), ERK1/2, pERK (pThr202/tyr204), Akt, pAkt (pSer473), pFOXO1/3a, and FOXO1/3a were from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA, USA); Sp1 and the PI3K p110 subunit were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); PI3K p85 subunit was from Millipore (Bedford, MA, USA); and IRS-1 and IRS-2 were from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY, USA). A pMEK1/2 monoclonal antibody was used in some studies and was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Water-soluble DEX was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Calf intestinal phosphatase was from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). The adenovirus encoding a FLAG-tagged PI3K p85α subunit was kindly provided by Dr. C. Ronald Kahn (Joslin Diabetes Institute and Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA); the adenovirus encoding constitutively active FOXO3a was prepared by Vector Biolabs (Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Cell culture of L6 myotubes

L6 myoblasts were from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA) and were maintained and differentiated for 3 d as described previously (20). This protocol results in fully differentiated myotubes (21). For experiments involving DEX (100 nM), the drug was added to cells 3 d after switching the cells into differentiating media (DMEM+2% horse serum) with repeated treatments every 24 h up to 48 h.

Diabetic rat model

The insulin deficiency (i.e., type 1 diabetes mellitus) model of muscle atrophy has been previously described (19). Briefly, male rats (∼150 gm) received a single injection of STZ (125 mg/kg) in citrate buffer by tail vein. STZ and control rats were pair-fed and on the third day after injection, the animals were anesthetized, and the gastrocnemius muscle was harvested. Food was withheld during the night before the tissue harvest to avoid the confounding influences of varying food intake between STZ and control rats on skeletal muscle protein metabolism.

Luciferase assays

To evaluate UbC promoter activity, cells were transfected with the either PGL3-basic-luciferase or rUbC (−340 to +3)-Luc (UbC-Luc) plasmids plus the TS-Renilla luciferase control plasmid (9, 22) using Fugene-6 as described previously (9). Similarly, a FOXO-luciferase reporter plasmid was purchased (Addgene, Camridge, MA, USA) and used as described for UbC-Luc. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activites were measured using the Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to standard protocol.

mRNA measurements

mRNA were measured using RT-PCR with the iQ SYBR Green reagent (Bio-Rad). RNA was isolated using the TRIzol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and was reversed transcribed using random hexamers. For UbC, PCR was performed with primers that were previously used to amplify a 172 bp region of the rat UbC gene that is not found in other ubiquitin-encoding genes in the same or other species (23, 24). For atrogin-1 and MuRF1, the PCR reactions were performed using published primer sets (25). 18S rRNA was used for a normalization control. Data were analyzed using the Bio-Rad iCycler software as described previously (26).

Adenoviral infection of myotubes

Myotubes were infected with adenoviruses that encode either GFP as a control (AdGFP), a FLAG-tagged, wild-type PI3K p85α subunit (Adp85), or a HA-tagged, constitutively active FOXO3a (AdcaFOXO3a) using a multiplicity of infection (MOI) ≤ 22. After 24 or 48 h, heterologous protein expression was confirmed by immunoblot analysis. When UbC promoter activity was evaluated in adenovirus-infected myotubes, cells were first transfected with UbC-Luc and TS-Renilla luciferase followed 24 h later by viral infection to ectopically express p85α. Luciferase activities were measured ∼48 h after infection.

Small interfering (siRNA) knockdown of IRS proteins

Pools of siRNA specific for human IRS-1 or IRS-2 were purchased commercially from Dharmacon RNAi Technologies (Chicago, IL, USA) and transfected into L6 cells using a protocol similar to that described by Huang et al.(27). Briefly, myoblasts were transfected with the pooled siRNA (50 nM) using a calcium phosphate method (CellPhect; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Afterward, the cells were incubated in antibiotic-free DMEM containing 2% FBS. The process was repeated 2 d later, and the culture media were simultaneously switched to normal differentitation media (DMEM plus 2% horse serum and antibiotics) for 3 d before the cells were harvested for immunoblot analyses.

Immunoblot analysis

For immunoblot analyses of most proteins, cells were lysed in a buffer consisting of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 137 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM Na3V04, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml antipain, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 μg/ml pepstatin, 1.5 mg/ml benzamidine, and 34 μg/ml PMSF (28). When Sp1 was examined, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 25 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM Na2PO4, 1 mM Na VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 0.1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.1 μg/ml leupeptin. Commercially available antibodies were used for immunoblot analyses according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Equal loading of total protein in the sample lanes was verified by Ponceau S Red staining and imaging. This method was used in lieu of measuring a specific “control” protein in each sample due to the inherent difficulties associated with identifying a protein whose turnover rate is unchanged during atrophy.

Protein degradation

Rates of protein degradation were measured as described previously (29,30,31). Briefly, cell proteins were labeled with 14C-phenylalanine (Phe) for 3 d. After a brief washout, cells were incubated in media containing an excess of unlabeled Phe and the rate of acid-soluble 14C-Phe release into the media was measured. To calculate the rate of protein degradation, the logarithm of the percentage radioactivity remaining in cells was plotted vs. time and was expressed as the log percentage radioactivity remaining × 103(31). All experimental values were then expressed as a percentage of the mean control cell rate.

Sp1 phosphorylation analysis

Cells were lysed in buffer consisting of 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 2 mM MnCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.4% Nonidet P-40, 5% glycerol, 10 mM benzamidine, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, and 0.5 mM PMSF. Calf intestinal phosphatase and reaction buffer were added to aliquots of clarified cell lysates and incubated at 37°C for 30–60 min according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Afterward, Sp1 in the treated lysates was examined by immunoblot analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means ± se. When 2 data sets were compared, a Student’s t test was used. When multiple treatment groups were compared, an ANOVA was performed with a Tukey post hoc test used to determine significant differences between individual groups. In some cases, experimental values were calculated as the mean ±se percentage of the corresponding mean control value before statistical analysis. In this case, a 1-sample t test was performed using a mean control of 100% for comparison. In all cases, differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. The GraphPad Prizm statistical and graphing software package (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for all calculations.

RESULTS

Glucocorticoids alter MEK/ERK/Sp1 and PI3K/Akt signaling

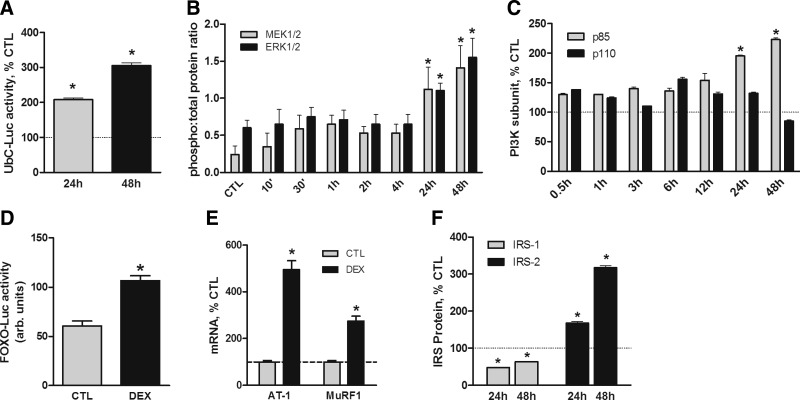

In earlier experiments, UbC promoter-luciferase reporter gene activity in myotubes was not significantly stimulated by relatively short (<16 h) treatment times with DEX but was increased after 48 h (9). Subsequent testing revealed that UbC-luciferase reporter activity was significantly increased after 24 h with DEX and was even greater at the 48 h time point (Fig. 1A). Given the involvement of MEK1/2 in the stimulation of UbC expression, the timing of the activation was surprising. Therefore, the activation time course of the MEK/ERK pathway following the addition of DEX was determined. MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was significantly increased after 24 h, and the increase was sustained through 48 h (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. S1A). Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, another member of the MAP kinase family, was not changed by either 1 or 24 h of DEX treatment (data not shown). We also examined the effects of acute and chronic glucocorticoid treatments on PI3K. DEX increased the content of the PI3K p85 regulatory subunit with a time course that was similar to that of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 1C and Supplemental Fig. S1B). The amount of PI3K p110 catalytic subunit was unchanged at all time points. Giorgino et al.(17) reported a similar DEX-induced change in the stoichiometry of the PI3K subunits that resulted in attenuated PI3K activity in serum-deprived myotubes. Consistent with their findings, treatment of myotubes with DEX for 48 h resulted in activation of the FOXO proteins. FOXO activity was monitored with a FOXO-luciferase reporter gene and by confirming the induction of AT-1 and MuRF1 mRNA (Fig. 1D, E).

Figure 1.

DEX increases UbC expression and alters PI3K and MEK/ERK signaling. L6 myotubes were treated with DEX (100 nM) for up to 48 h. A) Cells were transiently transfected with an UbC-luciferase reporter plasmid (UbC-Luc) before treatment with DEX to evaluate UbC gene transcription. Unless indicated otherwise, all data are mean percentage ± se of mean control value (n=3 experiments). B) Cells were treated with DEX for indicated times. Phosphorylated and total MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 proteins were evaluated by immunoblot analyses. Data are mean percentage ± se of the ratio of phosphorylated to total protein. C) Levels of PI3K p85 regulatory and P110 catalytic subunits were compared by immunoblot analyses. D) Myotubes were transiently transfected with an FOXO-luciferase reporter plasmid (FOXO-Luc) before treatment with DEX (100 nM, 48 h) to evaluate FOXO activity. Results were normalized for transfection efficiency and are reported in arbitrary units. E) Cells were treated with DEX for 48 h before measuring the relative amounts of mRNA for AT-1 and MuRF1 by qRT-PCR. F) IRS-1 and IRS-2 proteins in control and DEX-treated cells were compared by immunoblot analyses. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated control cells (n=4 experiments).

The IRS proteins can serve as upstream components of multiple signaling cascades including PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK. Therefore, the levels of these proteins may influence the activities of these pathways. After ≥24 h of DEX treatment, the amount of IRS-1 was decreased, whereas the level of IRS-2 was increased (Fig. 1F and Supplemental Fig. S1C). There was a detectable increase observed at the intermediate 12 h time point (Supplemental Fig. S1C) that was similar to the small changes in PI3K p85 at 12 h (Supplemental Fig. S1B). In both cases, these incremental changes were variable, significantly less than those at either 24 or 48 h, and are likely to represent a transition phase.

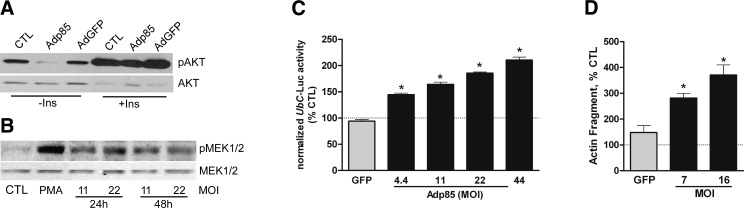

Given the similar time courses for alterations in IRS proteins, PI3K subunits, and MEK/ERK signaling, we tested whether the inhibition of PI3K-mediated signaling was linked to the activation of the MEK/ERK pathway by infecting myotubes with an adenovirus encoding p85α (Supplemental Fig. S2A). As expected, basal Akt phosphorylation was inhibited in cells expressing heterologous p85α but the cells remained responsive to insulin (Fig. 2A). The levels of phosphorylated MEK1/2 were also increased in infected cells (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the increased activation state of the MEK/ERK pathway, UbC promoter activity was increased in a concentration-dependent fashion by heterologous p85α expression (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Heterologous PI3K p85α expression mimicks DEX actions. L6 myotubes were infected with adenoviruses to express the PI3K p85α regulatory subunit (Adp85) or GFP (AdGFP) as a control. A) After 48 h, cells were harvested for immunoblot analyses of pAkt or total Akt; some cells were treated with insulin (100 nM) for 10 min immediately before harvest. B) Similar analyses were performed for pMEK1/2 and total MEK1/2; some control cells were treated with phorbol myristate (100 nM) for 10 min as an activation control. MOI of Adp85 is indicated at bottom. C, D) Myotubes were first transfected with UbC-Luc, followed 24 h later by infection with Adp85 or AdGFP. After 48 h (72 h total), cells were harvested, and luciferase activity was measured (C). Abundance of a 14-kDa actin cleavage fragment generated by caspase-3 was evaluated by immunoblot analysis (D). Data are mean percentage ± se of mean uninfected cell value. *P < 0.05 vs. GFP control cells (n=3 experiments).

As confirmation that PI3K activity was inhibited when the level of p85α was augmented, we measured the abundance of a 14 kDa actin fragment that is a product of caspase-3-mediated actin cleavage in control and Adp85α-infected cells. The abundance of this peptide has been linked to inhibition of PI3K, and it is typically higher in the muscles of animals and patients undergoing atrophy, leading to the proposal that it serves as a biomarker of muscle wasting (21, 32, 33). The 14-kDa actin fragment was higher in Adp85α-infected cells (Fig. 2D and Supplemental Fig. S2B).

FOXO regulates crosstalk between the PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways

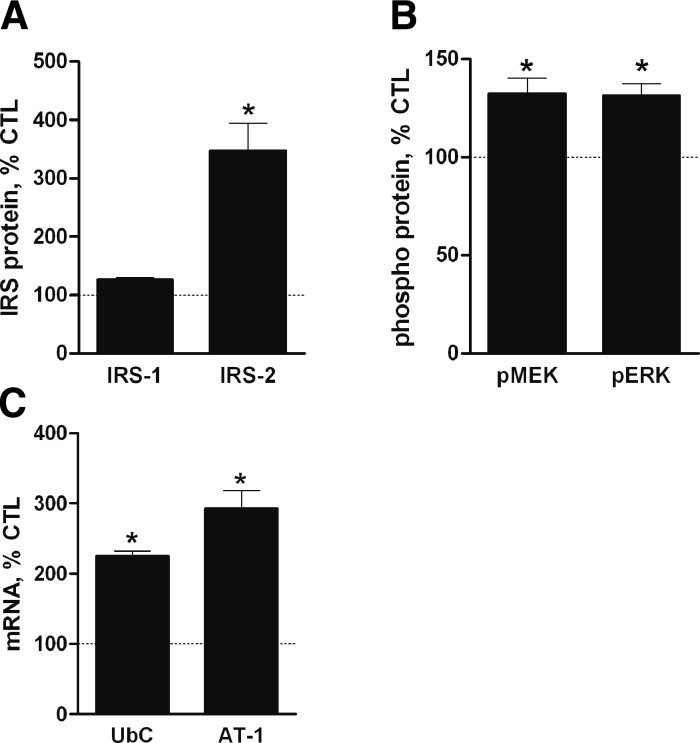

Reduced PI3K/Akt activity in muscle leads to activation of the FOXOs and a resulting increase in the expression of selected “atrogenes” (34). Another proposed FOXO target that is relevant to this study is the IRS-2 gene (35, 36) because IRS-2 protein was increased by DEX treatment. If IRS-2 is induced by FOXO in skeletal muscle, then the response would suggest a mechanism for the reciprocal crosstalk between the PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways and coordinate expression of the E3 ligases and UbC. The possibility was tested by expressing constitutively active FOXO3a (caFOXO3a) in muscle cells (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Expression of caFOXO3a had minimal effect on IRS-1 protein but increased IRS-2 (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. S3B). MEK and ERK phosphorylation was also enhanced as were the levels of UbC and AT-1 mRNA (Fig. 3B, C and Supplemental Fig. S3C).

Figure 3.

FOXO3a mediates DEX effects on IRS-2, MEK/ERK signaling, and UbC expression. A, B) L6 myotubes were infected with AdcaFOXO3a or AdGFP (MOI=22). After 48 h, cells were harvested. Immunoblot analyses were performed for IRS-1 and IRS-2 (A) or pMEK1/2 and pERK1/2 (B; normalized with total MEK1/2 and ERK1/2). Data are mean percentage ± se of mean GFP control cell value (n=3 experiments). C) mRNAs for UbC and AT-1 were measured by quantitative RT-PCR using 18S RNA as control RNA. Data are mean percentage ± se of mean GFP control cell value (n≥4 experiments). *P < 0.05 vs. control cells.

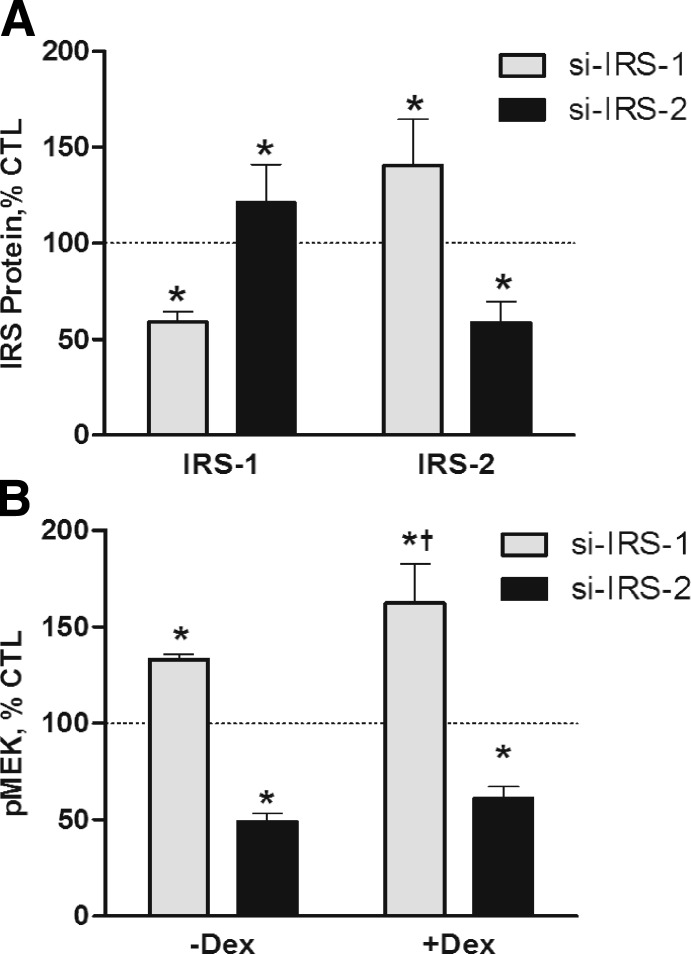

IRS-2 regulates MEK/ERK signaling in skeletal muscle

To determine if IRS-1 and IRS-2 have distinct regulatory functions, muscle cells were transfected with pooled siRNA specific for IRS-1 or IRS-2. The siRNA reduced their respective proteins by nearly 50% (Supplemental Fig. S4A); pooled nonspecific siRNA had no effect on either protein. The alterations in IRS-1 and IRS-2 resulted in a reciprocal change in the companion protein (Fig. 4A and Supplemental Fig. S4A). Baseline MEK1/2 signaling was decreased in cells treated with IRS-2 siRNA, and MEK1/2 activation by DEX was prevented (Fig. 4B and Supplemental Fig. S4B). In contrast, basal pMEK1/2 was increased in cells treated with IRS-1 siRNA and DEX induced a greater increase in pMEK1/2 (Fig. 4B and Supplemental Fig. S4B).

Figure 4.

IRS-1 and IRS-2 are functionally different. L6 myotubes were transfected with nonspecific siRNA or siRNA specific for IRS-1 or IRS-2. A) Immunoblot analyses were performed to compare IRS-1 and IRS-2 protein levels, relative to the nonspecific siRNA control. B) Immunoblot analyses were performed to compare pMEK levels, relative to the specific siRNA control. Cells represented on right side of panel were treated with DEX (100 nM) for 48 h before harvest. Data are mean percentage ± se of mean nonspecific siRNA control value. *P < 0.05 vs. control cells; †P < 0.05 vs. IRS-1 siRNA-DEX (n≥4 experiments).

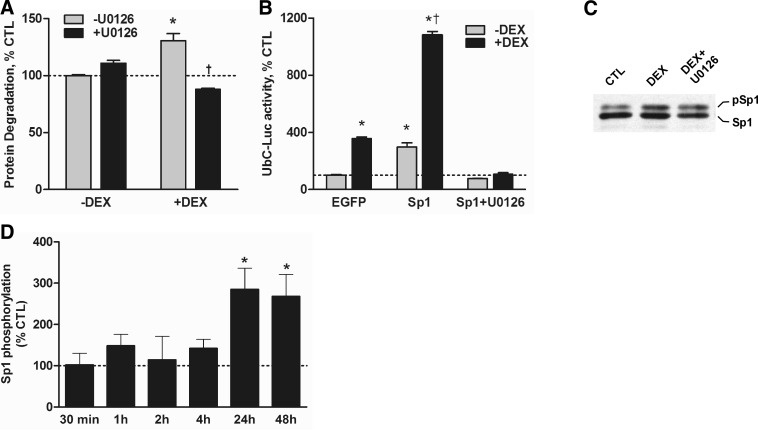

MEK signaling, protein degradation, and Sp1 phosphorylation

Our results suggest that perturbations in MEK signaling should affect protein degradation and UbC expression, particularly when accelerated by glucocorticoids. To test these possibilities directly, we first determined how U0126, a selective inhibitor of MEK1/2, affected the rate of protein degradation in myotubes. DEX alone significantly raised the proteolytic rate (Fig. 5A); U0126 alone slightly increased the rate, but the change was not significant. In contrast, addition of U0126 with DEX prevented the induction of protein degradation and actually reduced the rate below the level measured in untreated control cells. To extend this line of investigation, we tested how U0126 affected the induction of UbC-Luc reporter gene activity by Sp1 and DEX to determine if MEK modulates Sp1 activity and UbC expression. DEX increased reporter gene activity in control cells (Fig. 5B). In cells that were transfected to overexpress Sp1, luciferase activity was also augmented ∼3-fold and DEX raised the activity >10-fold (Fig. 5B). Addition of U0126 completely blocked the enhancement of UbC promoter activity by Sp1 regardless of whether the cells were treated with DEX.

Figure 5.

MEK1/2 regulates protein degradation, UbC promoter activity, and Sp1 phosphorylation. A) Rates of overall protein degradation in L6 myotubes were measured over 72 h in cells treated DEX (100 nM; added every 24 h). Some control and DEX-treated cells were also treated with 50 μM U0126 to inihibit MEK1/2. Data were calculated as percentage of mean control cell rate and are mean ± se percentage of control value (n=12/treatment). *P < 0.05 vs. untreated control cells; †P < 0.05 vs. DEX without U0126. B) Cells were transfected with the UbC-Luc and expression plasmids for either enhanced GFP (EGFP) or Sp1. Cell treatments were either DEX (100 nM) and/or U0126 (50 μM) for 48 h. Normalized luciferase activities were calculated and are a percentage of mean control value. Data are mean ± se of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated EGFP cells; †P < 0.05 vs. Sp1cells without DEX. C) Cells were treated with DEX (100 nM) ± U0126 (50 μM) for 36 h before performing an immunoblot analysis of Sp1. Positions of dephosphorylated Sp1 and phosphorylated Sp1 are indicated; n = 3 experiments. D) Immunoblot analysis of Sp1 was performed with lysates of cells treated with DEX (100 nM) for the specified times and control cells. Amounts of phosphorylated and total Sp1 were measured, and amounts of phosphorylated Sp1 relative to controls are shown. Data are mean ±se percentage of mean control value. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated control cells (n=4/treatment).

Sp1 was detected as a doublet during immunoblot analyses in our earlier report (9), suggesting that the protein may be post-translationally modified by phosphorylation. Therefore, lysates of DEX-treated muscle cells were treated with calf-intestinal phosphatase. Immunoblots of the treated lysates showed that the higher molecular weight form of Sp1 was converted to the lower molecular weight species, consistent with phosphorylation of the protein (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Further analysis revealed that DEX treatment for 24 h augmented the amount of phosphorylated Sp1 relative to control cells and that U0126 prevented the increase by DEX (Fig. 5C). The timing of the increase in Sp1 phosphorylation coincided with the time courses of MEK/ERK activation and induction of UbC expression (Fig. 5D and Supplemental Fig. S5B).

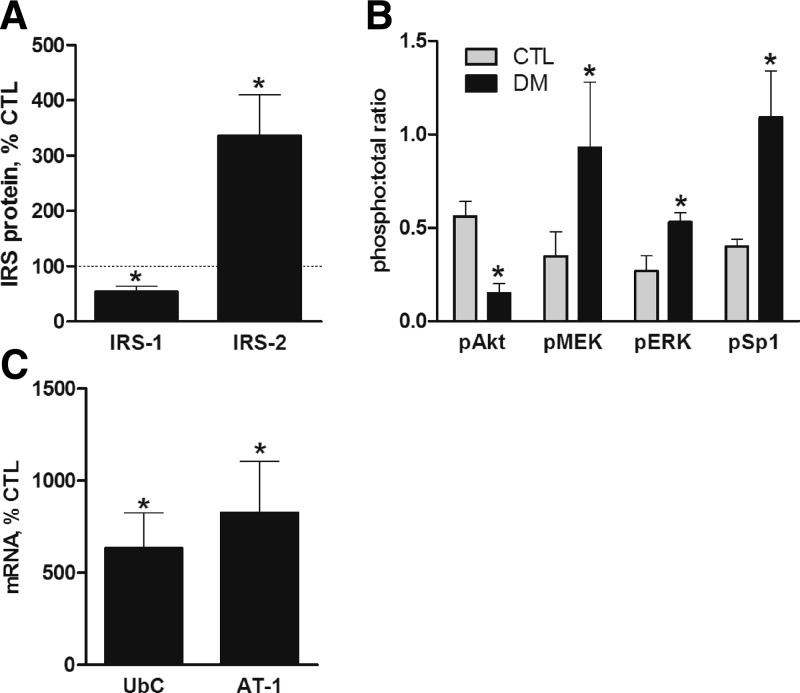

PI3K/Akt/FOXO and MEK/ERK signaling in insulin deficiency

The described experiments were performed with cultured myotubes that were maintained under a relatively controlled environment. In vivo, however, atrophy resulting from pathological conditions is associated with a variety of complex changes in the extracellular milieu of skeletal muscles. To determine if the changes observed in cultured myotubes are relevant to an in vivo model of muscle atrophy, we evaluated the status of the IRS-1/PI3K/Akt and IRS-2/MEK/ERK pathways in the gastrocnemius muscle from rats with streptozotocin-induced acute diabetes (STZ-DM). STZ-DM rats exhibit profound muscle loss due to insulin insufficiency and increased glucocorticoid production (18, 19). IRS-1 protein and Akt phosphorylation were reduced with STZ-DM, whereas IRS-2 and phosphorylated MEK, ERK, and Sp1 were increased (Fig. 6A, B and Supplemental Fig. S6). As reported earlier, UbC and AT-1 mRNA were increased in the same muscles (Fig. 6C; refs. 12, 37).

Figure 6.

Changes in IRS-1/PI3K/Akt and IRS-2/MEK/Erk/Sp1 signaling in diabetic rat muscle. Acute diabetes was induced with streptozotocin. A, B) Levels of IRS-1 and IRS-2 (A) and pAkt, pMEK1/2, pERK1/2, and Sp1 (B) in control and diabetic rat gastrocnemius muscles were compared by immunoblot analyses (n=3 rats/group in 2 experiments). C) mRNA for UbC and AT-1 were measured by quantitative RT-PCR using 18S RNA as the control RNA (n≥4 rats/group from 2 experiments). Data are mean percentage ± se of mean control rat value. *P < 0.05 vs. controls.

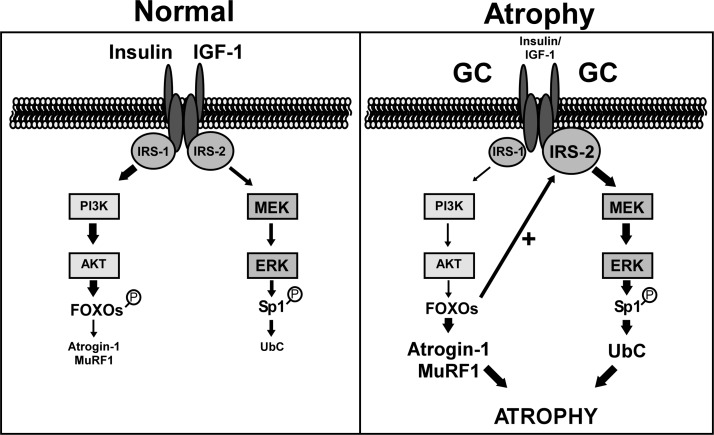

DISCUSSION

The multienzyme ubiquitin-proteasome pathway plays a major role in the loss of skeletal muscle due to disuse or chronic diseases. The accelerated rate of protein degradation in these conditions is associated with changes in the expression of various pathway components including ubiquitin, E2-conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases. The coordination of this genetic program suggests that the combined higher expression of these genes results in an increase in the overall degradative capacity of the system. Given that different transcriptions factors and signaling pathways mediate the ubiquitin and AT-1 responses (Fig. 7), it has not been apparent how such coordination is achieved. Our study is the first to address this important question, and we have provided a mechanism by which one stimulus, glucocorticoids, induces both genes.

Figure 7.

FOXO3a coordinates AT-1 and UbC expression via reciprocal crosstalk between the IRS-1/PI3K/Akt and IRS-2/MEK/ERK pathways. Under atrophy-inducing conditions (e.g., insulin deficiency) with increased glucocorticoid production, insulin/IGF-1 signaling through IRS-1/PI3K/Akt is attenuated. This leads to decreased phosphorylation (i.e., activation) and nuclear translocation of the FOXO proteins where they stimulate transcription of the AT-1 (and MuRF1) gene. FOXO3a (and perhaps other FOXOs) also raises the level of IRS-2, thereby increasing MEK/ERK signaling, Sp1 phosphorylation, and UbC expression.

Given the abundance of ubiquitin in skeletal muscle, some have questioned whether an increase in its expression is necessary for muscle atrophy. A sizeable amount of ubiquitin in the cell is conjugated to protein and, thus, is not readily available to target new substrates for degradation. A counterargument is that increased expression is required to maintain the pool of free ubiquitin for protein conjugation. Free ubiquitin generally turns over rapidly in cells, and stressful cellular conditions lead to a reduction in its content (38, 40). Moreover, Shabek et al.(41) recently reported that ubiquitin can be simultaneously degraded with its conjugated substrates by the proteasome. Therefore, the increase in ubiquitin production may be necessary to maintain a steady or accelerated rate of protein degradation in muscle during atrophy. Our results are consistent with this view because inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway with U0126 prevented both the induction of UbC promoter activity and the increase in proteolysis by DEX.

Glucocorticoids are required for the muscle atrophy that occurs during chronic diseases (42). When given in relatively high doses, glucocorticoids induce muscle wasting, in part, by stimulating protein degradation. It is widely accepted that a primary action of glucocorticoids in muscle is to inhibit PI3K/Akt signaling, thereby inducing FOXO activity and increasing AT-1 and MuRF1 transcription (7, 10, 43). We have now expanded this general model of glucocorticoid action by demonstrating that they activate the MEK/ERK pathway by an indirect mechanism that also involves the FOXO proteins. As a result of this reciprocal crosstalk network between the PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways (summarized in Fig. 7), baseline signaling through the latter is augmented, leading to increased UbC transcription. The network appears to be designed to delay up-regulation of UbC expression until there is a need for unconjugated ubiquitin protein. Moreover, the model predicts that both pathways should re-equilibrate to their preatrophy baseline shortly after restoration of glucocorticoid production or other signals that impair PI3K/Akt activity to their healthy state level. A final notable aspect of this network is that induction of both AT-1 and ubiquitin occur selectively in skeletal muscle and, to a limited degree, in the heart (12, 37, 44).

Prevailing evidence indicates that the mechanisms by which glucocorticoids inhibit the insulin/IGF-1/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is dependent on the cell types and whether cells are exposed to the hormone for a relatively short (i.e., acute) or prolonged (i.e., chronic) time. In dermal epithelial cells, the activated GR interacted directly with the p85 PI3K subunit to acutely inhibit PI3K activity (45). Similar findings in skeletal muscle were recently reported by Hu et al.(13). This type of inhibition might require continuous ligand-dependent activation of the receptor protein and, therefore, might be susceptible to receptor down-regulation. Other groups (17) attributed the attenuation of PI3K activity in DEX-treated myocytes to a selective increase in p85α regulatory subunit expression without altering the p110 catalytic subunit. Based on their model, impairment of PI3K/Akt signaling should occur for as long as the relative p85:p110 ratio remains above the baseline ratio in untreated cells. In our studies, heterologous overexpression of p85α in myotubes inhibited Akt phosphorylation while simultaneously increasing MEK1 phosphorylation, UbC promoter activity, and actin degradation over a protracted time frame (i.e., 24–48 h). Based on our model, it is also likely that the DEX-induced decrease in IRS-1 contributed to the inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling and activation of the FOXO proteins. Nakao et al.(46) reported a similar decrease in the level of IRS-1 protein and Akt signaling in muscles during unloading and in DEX-treated C2C12 muscle cells. Thus, glucocorticoids appear to down-regulate the PI3K/Akt pathway in muscle by a multifacted mechanism.

Our results indicate that IRS-1 and IRS-2 have distinctive biological functions in skeletal muscle. IRS-2 protein and MEK/ERK signaling increased in response to a transient reduction in IRS-1 expression, whereas partial depletion of IRS-2 reduced the level of phospho-MEK and prevented its increase by DEX. Similarly, Huang et al.(27) reported that knockdown of IRS-2 largely prevented insulin-induced ERK activation in L6 myotubes, whereas silencing IRS-1 attenuated insulin-induced actin remodeling, glucose uptake, and Glut4 translocation. A key difference in their experiments and ours is that they studied which IRS proteins were responsible for various insulin-induced responses, whereas we examined IRS functions in the basal, unstimulated state or after DEX treatment. Consistent with these cell-based studies, the phenotypes of IRS-1 and IRS-2 heterozygous and null mice are indicative of IRS-1 and IRS-2 being functionally distinct in skeletal muscle (reviewed in refs. 47, 48). One relevant trait of IRS-1 null mice is that IRS-2 protein is increased in the muscles compared with normal mice (49, 50). We also found that IRS-2 function was increased in muscles of chronic kidney failure rats, whereas IRS-1/PI3K/Akt signaling was impaired (51). UbC and AT-1 expression was also increased in muscle during chronic kidney failure (37). Based on these observations, we suggest that FOXO activity is regulated predominantly by IRS-1 rather than IRS-2. Given the complexity of FOXO activation, other factors may also be involved in the control of FOXO (52).

The terminal effector for the induction of UbC by DEX was previously identified to be Sp1 (9). In the mid-1980s, Mitchell and Tijan (53) characterized Sp1 as a transcription factor that binds to glucocorticoid boxes in the promoter regions of mammalian “housekeeping” genes. In the intervening period, it has become evident that Sp1 is a complex protein with multiple regulatory domains that can be modulated by post-translational modifications and protein cofactors (54). Through phosphorylation, a variety of kinases alter Sp1 activity or DNA-binding specificity (55,56,57,58,59). Our data reveal for the first time that glucocorticoids induce the phosphorylation of Sp1 in skeletal muscle with a time course coincident with MEK/ERK activation and increased UbC expression. Moreover, inhibition of MEK1/2 with U0126 blocked the increase in Sp1 phosphorylation by DEX and prevented the induction of a UbC-luciferase reporter gene by DEX and Sp1. In light of our earlier observation that DEX increases Sp1 activity and UbC transcription in skeletal muscle cells but not other cell types (12), we speculate that this mechanism of MEK1/2 activation by DEX occurs uniquely in skeletal muscle.

In conclusion, we have characterized a novel crosstalk signaling network that functions to coordinate the expression of at least 2 muscle “atrogenes,” ubiquitin and AT-1. The critical mediator is FOXO3a, but other FOXOs (FOXO 1 and FOXO4) also may be capable of eliciting these responses. By up-regulating IRS-2 expression, FOXO3a increases basal MEK/ERK signaling in the absence of other initiating signals like growth factors (Fig. 7). A key aspect of this model is the fact that the responses to glucocorticoids occur in a time-frame that is consistent with chronic induction of these genes. Such coordination of the components of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway has been hypothesized and would be important for sustaining an elevated rate of protein degradation during chronic diseases. This report is the first to provide evidence of coordination between two atrophy-related signaling pathways in cultured myotubes and muscles of intact animals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. C. Ronald Kahn (Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA) for providing the p85α adenovirus. The authors also thank Dr. H. A. Franch and Sara Zoromsky for performing experiments for the revised manuscript. Financial support was from U.S. National Institutes of Health grants DK-50740 (to S.R.P.), DK-61521 (to S.R.P.), and DK-73476 (to H.F.).

References

- Hall-Angerås M., Angerås U., Zamir O., Hasselgren P. O., Fischer J. E. Effect of the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU38486 on muscle protein degradation in sepsis. Surgery. 1991;109:468–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konagaya M., Bernard P. A., Max S. R. Blockade of glucocorticoid receptor binding and inhibition of dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in rat by RU38486, a potent glucocorticoid antagonist. Endocrinology. 1986;119:375–380. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-1-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price S. R., England B. K., Bailey J. L., Van Vreede K., Mitch W. E. Acidosis and glucocorticoids concomitantly increase ubiquitin and proteasome subunit mRNA levels in rat muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1994;267:C955–C960. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.4.C955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combaret L., Taillandier D., Dardevet D., Bechet D., Ralliere C., Claustre A., Grizard J., Attaix D. Glucocorticoids regulate mRNA levels for subunits of the 19 S regulatory complex of the 26 S proteasome in fast-twitch skeletal muscles. Biochem J. 2004;378:239–246. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auclair D., Garrel D. R., Zerouala A. C., Ferland L. H. Activation of the ubiquitin pathway in rat skeletal muscle by catabolic doses of glucocorticoids. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1997;272:C1007–C1016. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.3.C1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysis D., Underwood L. E. Regulation of components of the ubiquitin system by insulin-like growth factor I and growth hormone in skeletal muscle of rats made catabolic with dexamethasone. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5635–5641. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandri M., Sandri C., Gilbert A., Skurk C., Calabria E., Picard A., Walsh K., Schiaffino S., Lecker S. H., Goldberg A. L. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004;117:399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Mitch W. E., Wang X., Price S. R. Glucocorticoids induce proteasome C3 subunit expression in L6 muscle cells by opposing the suppression of its transcription by NF-κB. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19661–19666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M907258199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinovic A. C., Zheng B., Mitch W. E., Price S. R. Ubiquitin (UbC) expression in muscle cells is increased by glucocorticoids through a mechanism involving Sp1 and MEK1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16673–16681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt T. N., Drujan D., Clarke B. A., Panaro F., Timofeyva Y., Kline W. O., Gonzalez M., Yancopoulos G. D., Glass D. J. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2004;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D., Frantz J. D., Tawa N. E., Jr, Melendez P. A., Oh B. C., Lidov H. G., Hasselgren P. O., Frontera W. R., Lee J., Glass D. J., Shoelson S. E. IKKbeta/NF-kappaB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell. 2004;119:285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinovic A. C., Zheng B., Mitch W. E., Price S. R. Tissue-specific regulation of ubiquitin (UbC) transcription by glucocorticoids: In vivo and in vitro analyses. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F660–F666. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00178.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Wang H., Lee I. H., Du J., Mitch W. E. Endogenous glucocorticoids and impaired insulin signaling are both required to stimulate muscle wasting under pathophysiological conditions in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3059–3069. doi: 10.1172/JCI38770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Fischer D. R., Pritts T. A., Wray C. J., Hasselgren P. O. Expression and binding activity of the glucocorticoid receptor are upregulated in septic muscle. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:R509–R518. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00509.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgino F., Almahfouz A., Goodyear L. J., Smith R. J. Glucocorticoid regulation of insulin receptor and substrate IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in rat skeletal muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2020–2030. doi: 10.1172/JCI116424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad M. J. A., Folli F., Kahn J. A., Kahn C. R. Modulation of insulin receptor, insulin receptor substrate-1 and phoshatidylinositol 3-kinase in liver and muscle of dexamethasone-treated rats. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2065–2072. doi: 10.1172/JCI116803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgino F., Pedrini M. T., Matera L., Smith R. J. Specific increase in p85α expression in response to dexamethasone is associated with inhibition of insulin-like growth factor-I stimulated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in cultured muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7455–7463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitch W. E., Bailey J. L., Wang X., Jurkovitz C., Newby D., Price S. R. Evaluation of signals activating ubiquitin-proteasome proteolysis in a model of muscle wasting. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1999;276:C1132–C1138. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.5.C1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price S. R., Bailey J. L., Wang X., Jurkovitz C., England B. K., Ding X., Phillips L. S., Mitch W. E. Muscle wasting in insulinopenic rats results from activation of the ATP-dependent, ubiquitin proteasome proteolytic pathway by a mechanism including gene transcription. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1703–1708. doi: 10.1172/JCI118968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franch H. A., Raissi S., Wang X., Zheng B., Bailey J. L., Price S. R. Acidosis impairs insulin receptor substrate-1-associated phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in muscle cells: consequences on proteolysis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F700–F706. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00440.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Ordas R., Klein J. D., Price S. R. Regulation of caspase-3 activity by insulin in skeletal muscle cells involves PI3-kinase and MEK1/2. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1772–1778. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90636.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim N. M., Marinovic A. C., Price S. R., Young L. G., Frohlich O. Pitfall of an internal control plasmid: response of Renilla luciferase (pRL-TK) plasmid to dihydrotestosterone and dexamethasone. BioTechniques. 2000;29:782–784. doi: 10.2144/00294st04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinovic A. C., Mitch W. E., Price S. R. Tools for evaluating ubiquitin (UbC) gene expression: characterization of the rat UbC promoter and use of an unique 3′ mRNA sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;274:537–541. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Noga M., Matsuda M. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the rat polyubiquitin mRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218:232–234. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacheck J. M., Ohtsuka A., McLary S. C., Goldberg A. L. IGF-1 stimulates muscle growth by suppressing protein breakdown and expression of atrophy-related ubiquitin-ligases, atrogin-1 and MuRF1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E591–E601. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00073.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondesen B. A., Mills S. T., Kegley K. M., Pavlath G. K. The COX-2 pathway is essential during early stages of skeletal muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C475–C483. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00088.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Thirone A. C., Huang X., Klip A. Differential contribution of insulin receptor substrates 1 versus 2 to insulin signaling and glucose uptake in L6 myotubes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19426–19435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folli F., Saad M. J. A., Backer J. M., Kahn C. R. Insulin stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity and association with insulin receptor substrate 1 in liver and muscle of the intact rat. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22171–22177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovitz C. T., England B. K., Ebb R. G., Mitch W. E. Influence of ammonia and pH on protein and amino acid metabolism in LLC-PK1 cells. Kidney Int. 1992;42:595–601. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isozaki Y., Mitch W. E., England B. K., Price S. R. Protein degradation and increased mRNA encoding proteins of the ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway in BC3H1 myocytes require an interaction between glucocorticoids and acidification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;97:1967–1971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulve E. A., Dice J. F. Regulation of protein synthesis and degradation in L8 myotubes: effects of serum, insulin, and insulin-like growth factors. Biochem J. 1989;260:377–387. doi: 10.1042/bj2600377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Wang X., Miereles C., Bailey J. L., Debigare R., Zheng B., Price S. R., Mitch W. E. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:115–123. doi: 10.1172/JCI200418330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workeneh B. T., Rondon-Berrios H., Zhang L., Hu Z., Ayehu G., Ferrando A., Kopple J. D., Wang H., Storer T., Fournier M., Lee S. W., Du J., Mitch W. E. Development of a diagnostic method for detecting increased muscle protein degradation in patients with catabolic conditions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3233–3239. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Brault J. J., Schild A., Cao P., Sandri M., Schiaffino S., Lecker S. H., Goldberg A. L. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S., Dunn S. L., White M. F. The reciprocal stability of FOXO1 and IRS2 creates a regulatory circuit that controls insulin signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3389–3399. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide T., Shimano H., Yahagi N., Matsuzaka T., Nakakuki M., Yamamoto T., Nakagawa Y., Takahashi A., Suzuki H., Sone H., Toyoshima H., Fukamizu A., Yamada N. SREBPs suppress IRS-2-mediated insulin signalling in the liver. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:351–357. doi: 10.1038/ncb1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecker S. H., Jagoe R. T., Gilbert A., Gomes M., Baracos V., Bailey J., Price S. R., Mitch W. E., Goldberg A. L. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. FASEB J. 2004;18:39–51. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0610com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A. L., Baboshina O., Williams B., Schwartz L. M. Coordinated induction of the ubiquitin conjugation pathway accompanies the devolopmentally programmed death of insect skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9407–9412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A. L., Bright P. M. The dynamics of ubiquitin pools within cultured human lung fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J., Leggett D. S., Finley D. Ubiquitin depletion as a key mediator of toxicity by translational inhibitors. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9251–9261. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9251-9261.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabek N., Herman-Bachinsky Y., Ciechanover A. Ubiquitin degradation with its substrate, or as a monomer in a ubiquitination-independent mode, provides clues to proteasome regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11907–11912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905746106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitch W. E., Goldberg A. L. Mechanisms of muscle wasting: the role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1897–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612193352507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell D. S., Baehr L. M., van den Brandt J., Johnsen S. A., Reichardt H. M., Furlow J. D., Bodine S. C. The glucocorticoid receptor and FOXO1 synergistically activate the skeletal muscle atrophy associated with MuRF1 gene. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E785–E797. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00646.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine S. C., Latres E., Baumhueter S., Lai V. K., Nunez L., Clarke B. A., Poueymirou W. T., Panaro F. J., Na E., Dharmarajan K., Pan Z. Q., Valenzuela D. M., DeChiara T. M., Stitt T. N., Yancopoulos G. D., Glass D. J. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294:1704–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1065874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leis H., Page A., Ramirez A., Bravo A., Segrelles C., Paramio J., Barettino D., Jorcano J. L., Perez P. Glucocorticoid receptor counteracts tumorigenic activity of akt in skin through interference with the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:303–311. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao R., Hirasaka K., Goto J., Ishidoh K., Yamada C., Ohno A., Okumura Y., Nonaka I., Yasutomo K., Baldwin K. M., Kominami E., Higashibata A., Nagano K., Tanaka K., Yasui N., Mills E. M., Takeda S., Nikawa T. Ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b is a negative regulator for IGF-1 signaling during muscle atrophy caused by unloading. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4798–4811. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01347-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirone A. C., Huang C., Klip A. Tissue-specific roles of IRS proteins in insulin signaling and glucose transport. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plum L., Wunderlich F. T., Baudler S., Krone W., Bruning J. C. Transgenic and knockout mice in diabetes research: novel insights into pathophysiology, limitations, and perspectives. Physiology. 2005;20:152–161. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00049.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdag A. C., Dumke C. L., Kahn C. R., Cartee G. D. Calorie restriction increases insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle from IRS-1 knockout mice. Diabetes. 1999;48:1930–1936. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.10.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakami A., Toyonaga T., Tsuruzoe K., Shirotani T., Matsumoto K., Yoshizato K., Kawashima J., Hirashima Y., Miyamura N., Kahn C. R., Araki E. Heterozygous knockout of the IRS-1 gene in mice enhances obesity-linked insulin resistance: a possible model for the development of type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol. 2002;174:309–319. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1740309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. L., Zheng B., Hu Z., Price S. R., Mitch W. E. Chronic kidney disease causes defects in signaling through the insulin receptor substrate/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway: implications for muscle atrophy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1388–1394. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan D. R., Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276–2288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. J., Tijan R. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science. 1988;245:371–378. doi: 10.1126/science.2667136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. A., Suh D. C., Kang J. E., Kim M. H., Park H., Lee M. N., Kim J. M., Jeon B. N., Roh H. E., Yu M. Y., Choi K. Y., Kim K. Y., Hur M. W. Transcriptional activity of Sp1 is regulated by molecular interactions between the zinc finger DNA binding domain and the inhibitory domain with corepressors, and this interaction is modulated by MEK. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28061–28071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alroy I., Soussan L., Seger R., Yarden Y. Neu differentiation factor stimulates phosphorylation and activation of the Sp1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1961–1972. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong S. A., Barry D. A., Leggett R. W., Mueller C. R. Casein kinase II-mediated phosphorylation of the C terminus of Sp1 decreases its DNA binding activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13489–13495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courey A. J., Tjian R. Analysis of Sp1 in vivo reveals multiple transcriptional domains, including a novel glutamine-rich activation motif. Cell. 1988;55:887–898. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fojas d. B., Collins N. K., Du P., Azizkhan-Clifford J., Mudryj M. Cyclin A-CDK phosphorylates Sp1 and enhances Sp1-mediated transcription. EMBO J. 2001;20:5737–5747. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A., Cereghini S., Sontag E. Protein phosphatase 2A and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulate the activity of Sp1-responsive promoters. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9385–9389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.