Abstract

Background

While the dominant product of vascular cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, prostacyclin (PGI2), restrains atherogenesis, inhibition and deletion of COX-2 have yielded conflicting results in mouse models of atherosclerosis. Floxed mice were used to parse distinct cellular contributions of COX-2 in macrophages (Mac) and T cells (TC) to atherogenesis.

Methods and Results

Deletion of Mac COX-2 (MacKO) was attained using LysMCre mice and suppressed completely lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated Mac prostaglandin (PG) formation and LPS evoked systemic PG biosynthesis by ∼ 30%. LPS stimulated COX-2 expression was suppressed in polymorphonuclear leucocytes (PMN) isolated from MacKOs, but PG formation was not even detected in PMN supernatants from control mice. Atherogenesis was attenuated when MacKOs were crossed into hyperlipidemic LdlR KOs. Deletion of Mac COX-2 appeared to remove a restraint on COX-2 expression in lesional non-leukocyte (CD45 and CD11b negative) vascular cells that express vascular cell adhesion molecule and variably, α-smooth muscle actin and vimentin, portending a shift in PG profile and consequent atheroprotection. Basal expression of COX-2 was minimal in TCs, but use of CD4Cre to generate TC knockouts (TCKOs) depressed its modest upregulation by anti-CD3ε. However, biosynthesis of PGs, TC composition in lymphatic organs and atherogenesis in LDLR KOs were unaltered in TCKOs.

Conclusions

Mac COX-2, primarily a source of thromboxane A2 and PGE2, promotes atherogenesis and exerts a restraint on enzyme expression by lesional cells suggestive of vascular smooth muscle cells, a prominent source of atheroprotective PGI2. TC COX-2 does not influence detectably TC development or function nor atherogenesis in mice.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Inflammation, Prostaglandins

Lipid products of the prostaglandin (PG) G/H synthase enzymes (colloquially known as cyclooxygenases (COX) -1 and -2) are mediators of pain, fever and inflammation 1 and the primary targets of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, deletion of either COX-1 or the more readily inducible COX-2 may promote, dampen or leave unaffected the inflammatory response in diverse rodent models 2. Although NSAIDs specific for inhibition of COX-2 are less likely to cause serious gastrointestinal adverse events than drugs that inhibit both COXs together, placebo controlled trials have demonstrated that they also confer a cardiovascular risk, attributable to suppression of cardioprotective COX-2 products, particularly prostacyclin (PGI2) 3.

Deletion, mutational inactivation, knockdown and pharmacological inhibition of COX-2 predispose mice to thrombogenesis and an elevation of blood pressure 3, 4, effects also seen in mice lacking the PGI2 ligated, I prostanoid (IP) receptor 3. However, while deletion of the IP fosters initiation and early development of atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice 5, 6, COX-2 deletion or its pharmacological inhibition have yielded contrasting results 7. It has been speculated that this may reflect (i) the differential impact of COX-2 inhibition on cells with divergent effects on atherogenesis; (ii) contrasting effects of COX-2 inhibition on atherogenesis at varied stages of disease evolution and (iii) varied degrees of selectivity for COX-2 amongst the drug regimens employed 7.

We generated mice in which the COX-2 gene is flanked by loxP sites 8, 9 to permit cell specific analysis of its contribution to the inflammatory response in vivo. Macrophages (Macs) are fundamental to the inflammatory response, mediating phagocytosis, releasing cytokines and serving as antigen presenting cells 10. Activation of Macs by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) markedly upregulates COX-2 and augments release of its major products, thromboxane (Tx) A2 and PGE2 11. The discrete contribution of Mac COX-2 to inflammation has been thus far approached indirectly. Transfer of COX-2 deficient fetal liver cells to lethally irradiated mice retards atherogenesis 12, 13. Here, COX-2 deficiency confined to myeloid cells, including Macs (Mac-COX-2 KOs), was achieved by mating the floxed mice with those carrying the LysMCre recombinase 14.

Prostaglandins also influence immune regulation by modulating the development and functions of dendritic cells, T and B cells 2, 15, 16. We have previously reported that products of both COX-1 and COX-2 influence T cell development in the thymus 17, 18 and PGs can exert contrasting effects on the function of mature T cells 2. However, the cellular origin of such lipids has long been a source of debate. While subpopulations of T cells have been identified that express COX-2 19-24 the evidence that T cell derived prostaglandins subserve an autocrine function remains inconclusive 19, 23, 25. Here, we crossed floxed mice with CD4-Cre to deplete COX-2 in T cells and examine its effect on T cell development and function and in atherogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Generation of macrophage-specific COX-2-deficient mice (Mac-COX-2 KOs)

Mice with the COX-2 gene flanked with 2 LoxP sites, COX-2f/f mice, were generated as described 8, 9 on a mixed 129Sv/B6 background (∼75% B6, ∼25% 129Sv) and crossed with B6 LysMCre+/+ mice to obtain LysMCre+/-/COX-2f/+ mice, which then were backcrossed with COX-2f/f to create LysMCre+/-/COX-2f/f mice. These mice were intercrossed to generate homozygous LysMCre+/+/COX-2f/f mice as Mac-COX-2 KO and COX-2f/f mice as their littermate wild-type controls (WT). LysMCre+/+/COX-2f/f mice were further crossed with B6 LdlR−/− mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to obtain LysMCre+/-/COX-2f/+/ LdlR+/- mice. These mice were intercrossed to create the LysMCre+/-/COX-2f/f/ LdlR-/- genotype. Intercrossing LysMCre+/-/COX-2f/f/ LdlR-/- mice generated LysMCre+/+/COX-2f/f/ LdlR−/− mice (Mac-COX-2 KO/ LdlR−/−) and their COX-2f/f/ LdlR−/− littermate controls (WT/ LdlR−/−), which were both fed a high fat diet (HFD, 0.2% cholesterol/21% saturated fat; formula TD 88137, Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN) from 8 weeks of age for either 3 or 6 months. Genotyping by PCR was derived from Wang et al 9 for the floxed COX-2 gene and from the Jackson Laboratory protocol for LdlR. LysMCre genotyping used primer pair 5′CTT GGG CTG CCA GAA TTT CTC (LysM1) and 5′TTA CAG TCG GCC AGG CTG AC for the detection of the wild type allele, and primer pair LysM1 and 5′CCC AGA AAT GCC AGA TTA CG for the LysMCre allele.

Generation of T cell-specific COX-2-deficient mice (TCKOs)

The floxed mice described above were crossed with B6 CD4Cre mice (Taconic, Hudson, NY) to obtain CD4Cre/COX-2f/+ mice, which then were backcrossed with COX-2f/f to create CD4Cre/COX-2f/f mice. These mice were crossed with COX-2f/f to generate CD4Cre/COX-2f/f mice as T cell-specific COX-2-deficient mice (TCKOs) and COX-2f/f mice as WT. These mice were further crossed with B6 LdlR−/− mice (The Jackson Laboratory) to obtain CD4Cre/COX-2f/f/ LdlR-/- mice and COX-2f/f/ LdlR-/-, which were crossed to create the CD4Cre-/-/COX-2f/f/ LdlR-/- (T-COX-2 KO/LdlR-/-) and COX-2f/f/ LdlR-/- littermate controls (WT/LdlR-/-). These mice were fed the same HFD as the Mac-COX-2 KOs. CD4Cre genotyping used primer pair 5′CGA TGC AAC GAG TGA TGA GG and 5′GCA TTG CTG TCA CTT GGT CGT. To detect COX-2 deletion, primer pairs 5′TTT GCC ACT GCT TGT ACA GCA ATT and 5′TGA GGC AGA AAG AGG TCC AGC CTT were used. All animals in this study were housed following guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania. All experimental protocols were IACUC approved.

Peritoneal macrophage culture

Peritoneal macrophages were collected 4 days after intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 ml 10% thioglycollate. Nonadherent cells were removed after 2 hrs incubation. Adherent cells were treated with LPS (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) 5μg/ml for 6 hrs for RNA and 12 hrs for protein and supernatant collection.

Mass spectrometic analysis of prostanoids and their metabolites

Prostanoids or their metabolites were measured by mass spectrometry as described previously 11, 26. Briefly, macrophage production of PGE2, PGD2, TxA2, and PGI2 was determined by quantitation of PGE2, PGD2, TxA2, and 6-keto PGF1α in cell culture supernatants, respectively, and normalized with protein. Systemic production of PGE2, PGD2, TxA2, and PGI2 was determined by quantitation of their major urinary metabolites [7-hydroxy-5,11-diketotetranorprostane-1,16-dioic acid (PGE-M), 11,15-dioxo-9α-hydroxy-, 2,3,4,5-tetranorprostan-1,20-dioic acid (tetranor PGD-M), 2,3-dinor TxB2 (Tx-M), and 2,3-dinor 6-keto PGF1α (PGI-M)] in 24 hr collections respectively and normalized with creatinine.

Quantitation of atherosclerosis

Mouse aortic trees were prepared and stained and atherosclerotic lesions were quantitated as previously described 11. Briefly, mice on a LdlR-/- background fed a HFD for 3 or 6 months were sacrificed. The entire aorta from the aortic root to the iliac bifurcation was collected and fixed in 10% buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Adventitial fat was removed. The aorta was opened longitudinally, stained with Sudan IV (Sigma) and pinned down on black wax to expose the intima. The extent of atherosclerosis (Phase 3 Imaging Systems, Glen Mills, PA) was determined by the en face method– lesion area percentage to the entire intimal area.

Immunohistochemical examination of lesion morphology

Mouse hearts were embedded in OCT compound and 8 μm serial sections of the aortic root mounted on masked slides (Carlson Scientific, Peotone, IL) for analysis of lesion morphology. Briefly, acetone fixed and peroxidase-quenched sections were blocked with goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), incubated with primary antibodies FITC-conjugated mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin clone 1A4 (Sigma), followed by incubation with biotinylated goat anti-FITC (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) or with rabbit-anti-mouse COX-2 antibody (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI), followed by biotinylated goat anti- rabbit Ig (Vector Laboratories) secondary antibody. Serial sections were stained with biotinylated rat anti-mouse VCAM-1/CD106 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), biotinylated rat anti-mouse CD11b (BD Biosciences) or rat-anti-mouse CD45 (BD Biosciences) followed by incubation with biotinylated goat-anti-rat Ig secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch,). Alternatively serial sections were blocked with rabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch,) and then incubated with goat anti-vimentin (Sigma) or anti-mouse active caspase 3 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) followed by biotinylated rabbit anti goat (Jackson Immunoresearch,) and biotinylated goat-anti-rabbit Ig (Vector Laboratories) secondary antibodies respectively.

All reactions were amplified with Vectastain ABC avidin-biotin (Vector Laboratories), and developed with diaminobenzidine (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). All sections were counterstained with Gill's Formulation No. 1 hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific). Isotype matched controls were run in parallel and showed negligible staining in all cases.

Statistical analysis

When comparisons between genotypes involve both male and female genders, the data were first subjected to the two-way ANOVA. Non-parametric ANOVA was performed out of concern for the parametric assumptions of equal variances and normality, specifically the two-way Friedman test was used with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Pairwise comparisons were performed only if the multiple-testing corrected ANOVA p-values were significant at the 0.05 level. This applies in particular to the urinary PG metabolites and atherosclerotic lesion burden. All two-sample tests were performed using non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. A total of 35 two-sample comparisons were performed at the 0.05 significance level, yielding 19 significant uncorrected p-values at the 0.05 level. If all null 35 hypotheses were true, we would expect 1.75 falsely rejected null hypotheses on average, at the 0.05 level, indicating greater than 90% of the concluded differences are real. Because non-parametric significance tests were performed, data are presented using medians with first and third quartiles.

Results

Macrophage contribution to systemic biosynthesis of prostanoids

Stimulation of peritoneal Macs with LPS ex vivo markedly augmented expression of COX-2 (Figure 1) and formation of PGs (Figure 2 A). Expression of LPS stimulated COX-2 mRNA (∼98 %) and proteins (∼ 95%) were reduced in the Mac-COX-2 KOs (Figure 1 A and B). A similar reduction was observed in bone marrow derived macrophages (Supplementary Figure 1 A), but not in vascular smooth muscle cells (Supplementary Figure 1 C). The dominant products of peritoneal Macs, TxA2 and PGE2, were markedly depressed in Mac-COX-2 KOs, as were the less abundant products, PGI2, and PGD2 (Figure 2A). Although the abundance and profile of the prostanoids differed somewhat in bone marrow derived Macs, the levels were again markedly suppressed in the KOs (Supplementary Figure 1 B). The impact of Mac COX-2 deletion on prostanoid biosynthesis was also assessed by measurement of the increment in major urinary metabolites after LPS. Stimulated, systemic biosynthesis of prostanoids was significantly depressed 30 – 38% on average in the Mac-COX-2 KOs (Figure 2 B).

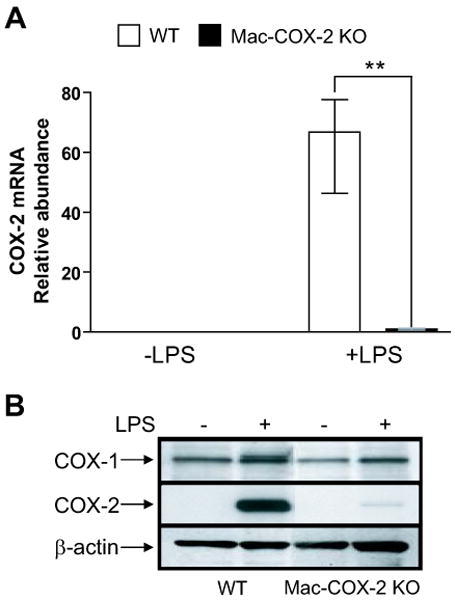

Figure 1. Macrophage-specific COX-2 deletion characterization.

A. COX-2 mRNA levels determined by real-time PCR. All samples were normalized with 18s RNA. COX-2 mRNA was significantly reduced in stimulated Mac-COX-2 KO peritoneal macrophages (p=0.001). **, p<0.01; n=5-6. B. COX protein levels in peritoneal macrophages. Samples were collected from a pull of 3 mice in each genotype. Data are presented using medians with first and third quartiles.

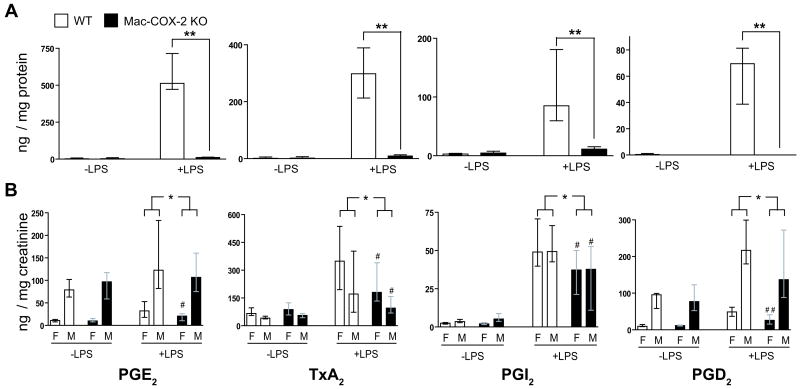

Figure 2. Impact of macrophage COX-2 deletion in prostanoid production measured by mass spectrometry.

A. Prostanoid profiles in cultured macrophage supernatants. PGE2, TxA2, PGI2 and PGD2, was determined by quantitation of PGE2, TxA2, 6-keto PGF1α, and PGD2. All data were normalized with total proteins. PG levels were significantly lower in stimulated Mac-COX-2 KO supernatants (p=0.002 for PGE2, TxA2, PGI2 and PGD2). **p<0.01; n=5-6. B. Profiles of urinary prostanoid metabolites in LPS endotoxemia. Twenty-four hr urine was collected before and after a bolus of LPS 1mg/kg intraperitoneal injection. Biosynthesis of PGE2, TxA2, PGI2 and PGD2 was assessed by quantitation of their major urinary metabolites: 7-hydroxy-5,11-diketotetranorprostane-1,16-dioic acid (PGE-M), 2,3 dinot TxB2 (Tx-M), 2,3 dinor 6 keto PGF1α (PGI-M) and 11,15-dioxo-9α-hydroxy-2,3,4,5-tetranorprostan-1,20-dioic acid (tetranor PGD-M), respectively. All urine data were normalized with creatinine. Analysis of variance revealed a significant reduction in LPS stimulated prostanoid metabolite excretion in the Mac-COX-2 KO mice (p=0.04, p=0.02, p=0.02, and p=0.012 for PGE-M, Tx-M, PGI-M, and PGD-M respectively). *, p<0.05; n=25-27. Significant depression of Tx-M (p=0.038), and PGI-M (p=0.044) were observed in male KOs and of PGE-M (p=0.024), Tx-M (p=0.031), and PGI-M (p=0.039) and PGD-M (p=0.009) were observed in female KOs (#, p<0.05; ##, p<0.01; n=14-16). Data are presented using medians with first and third quartiles.

LysMCre mice express Cre recombinase in all myeloid cells including Macs, neutrophils and some dendritic cells. Although induction of COX-2 was evident in WT neutrophils (Supplementary Figure 2), prostanoid generation was not detectable with or without LPS stimulation in either WT or KO cells. Similarly, COX-2 deletion was detected in only ∼ 15% of the CD11c+ splenic dendritic cells 14, so the dominant impact in the KOs is on Mac COX-2.

Modest expression of COX-2 mRNA in T cells

Specific deletion of the COX-2 gene in T cells in TCKO mice was confirmed by genomic PCR (Supplementary Figure 3 A). While both COX-1 and COX-2 mRNAs were readily detected in non-T cells (mostly B cells) from lymph nodes, their levels were very low in T cells (Supplementary Figure 3 C and 3 D). T cell stimulation with surface bound anti-CD3ε antibody at a concentration of 10 μg/ml augmented expression of COX-2 (Supplementary Figure 3 D, insert), but not COX-1 (Supplementary Figure 3C, insert) and this effect was attenuated in TCKOs. However, neither COX-2 nor COX-1 protein was detected in T cells under basal or stimulated conditions in the WTs or TCKOs (Supplementary Figure 3 B). Notably, a faint band with a slightly larger molecular weight to COX-2 was expressed under stimulated conditions; this protein persisted in cells from mice with global deletion of COX-2. Consistent with the absence of COX-2 protein, generation of prostanoids remained at the limit of detection (despite the addition of exogenous substrate) in both WTs and TCKOs.

T cell COX-2 does not influence T cell development or function in mice

As both COXs have been implicated in regulating T cell development in the thymus 17, 18, we sought to determine whether this might reflect in part an autocrine function of T cell COX-2. Adult mouse thymus, lymph nodes, and spleen revealed no macroscopic or microscopic difference between WTs and TCKOs in size or morphology (Supplementary Figure 4 A). Similarly, no differences were observed in CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ subpopulations or in anti-CD3 stimulated regulatory T cell function (Supplementary Figure 4 B).

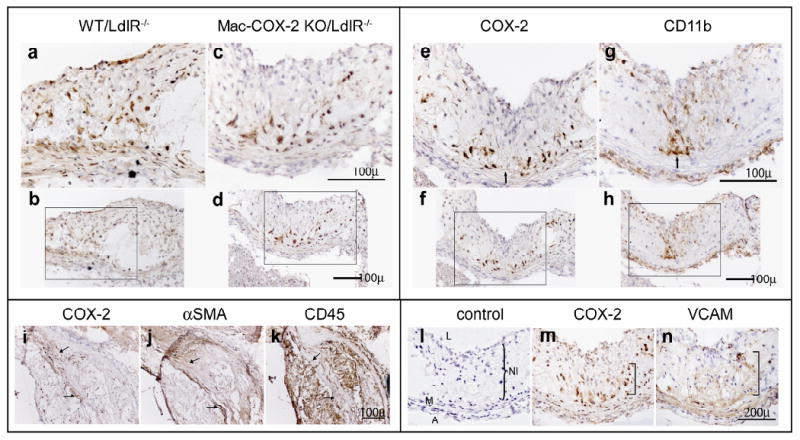

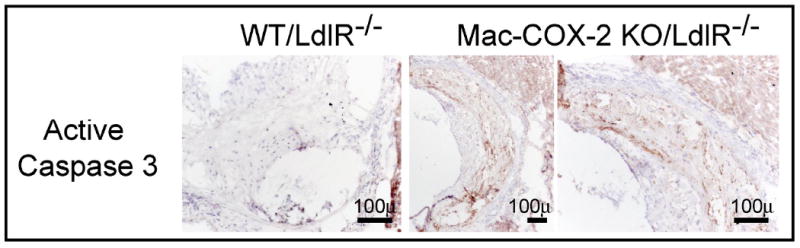

Macrophage COX-2 accelerates atherogenesis and restrains enzyme expression in a population of non – macrophage lesional cells

Atherosclerotic lesion burden (Figure 3 A) was reduced significantly in Mac-COX-2 KOs by ∼ 25% in both genders after 6 months on a high fat diet (HFD). Plasma lipids were not affected by Mac COX-2 deletion in either gender (Supplementary Figure 5). Mac COX-2 is a potential source of inflammatory modulators of adipocyte function 27, 28 and is markedly upregulated when fibroblasts are induced to differentiate into adipocytes 29. Neither weight gain nor percentage body fat (Supplementary Figure 6A and B) measured after 3 or 6 months on the HFD differed between controls and Mac-COX-2 KOs backcrossed onto a low density lipoprotein receptor deficient (LdlR-/-) background. Lesional analysis was performed at 3 months as genotypic distinctions in morphology are often less evident at more advanced stages of atherogenesis 11. Both WT and MacKO lesions were already advanced, with prominent atheromatous cores and fibrotic caps. WT lesions showed widely dispersed cells staining positive for COX-2 (Figure 4; panels a and b), while a more discrete intimal population of cells, with a biased distribution toward the intimal - medial border, stained for COX-2 in the MacKO lesions (Figure 4; panels c and d). These latter COX-2 positive cells were distinct from CD45 positive leukocytes including CD11b positive macrophages on serial sections (Figure 4; panels e and f vs panels g and h and Supplementary Figures 7 a and 7 b). While they are distinct from cells stained with macrophage markers, their precise origin is unclear. They are uniformly negative for the pan-leukocyte marker, CD45, but do stain positive for vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (Figure 4; panels l, m, and n) and resemble a previously reported proliferative subset of lesional VSMCs 30, 31. These cells were heterogeneous with respect to expression of α-SMA (Figure 4 J) and vimentin (Supplementary Figure 7 Cc). Although analysis of PG formation by these lesional cells is not technically possible, if they proved to be VSMCs, upregulation of COX-2 at the expense of that in Macs would likely favor a shift towards formation of atheroprotective PGI2 11. There was no apparent alteration in the lesional expression of COX-1 in the Mac-COX-2 KOs (Supplementary Figure 8 a and b). Apoptosis, reflected by staining for activated caspase 3, was augmented in lesions from Mac COX-2 KOs (Figure 5).

Figure 3. Effects of cell specific COX-2 deletion in atherogenesis.

All mice were backcrossed onto a low density lipoprotein receptor deficient (LdlR-/-) background and fed a high fat diet (HFD) from 8 wks of age. Aortic atherosclerotic lesion formation, represented by the ratio of lesion area to total aortic area, in mice either after 3 or 6 months on a HFD, was analyzed by en face. A. Analysis of variance revealed a significant reduction in lesion area in the Mac-COX-2 KO/ LdlR-/- mice on 6 months of HFD (p=0.007; n=28-31). **, p<0.01. Subsequent comparison demonstrated same trend in both females (p=0.029, n=14-16) and males (p=0.014, n=12-17). #, p<0.05. B. T cell COX-2 deletion failed to impact lesion formation. p=0.23, n=8-12 at 3 months and p=0.15, 16-20 at 6 months. Data are presented using medians with first and third quartiles.

Figure 4. Impact of macrophage COX-2 deletion in vascular smooth muscle COX-2 expression in atherosclerotic lesions by immunohistochemistry.

Lesion morphology in aortic roots from mice on HFD for 3 months was analysed. Upper left panel: Representative COX-2 staining in WT/LdlR-/- (a and b) and Mac-COX-2 KO/ LdlR-/- (c and d) aortic root sections. Upper right panel: COX-2 (e and f) and CD11b (g and h) staining on Mac-COX-2 KO/LdlR-/- aortic sections. COX-2 expressing cells are not CD11b+ macrophages. Arrows indicate corresponding areas on serial sections. a and c, and e and g, are magnifications of boxed areas in b and d, and f and h, respectively. Lower left panel: Cells expressing COX-2 in Mac-COX-2 KO/LdlR-/- aortic sections (i) are negative for or express only low levels of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (j) and are not CD45 positive lymphocytes (k). Arrows indicate corresponding areas on serial sections. Lower right panel: Representative COX-2 staining in WT/LdlR-/- (l) and in Mac-COX-2 KO/LdlR-/- aortic sections (m). Cells expressing COX-2 in Mac-COX-2 KO/LdlR-/- aortic sections are also positive for VCAM (n) in neointima. L: lumen, NI: neointima, M: media, A: adventitia. Parentheses show NI.

Figure 5. Impact of macrophage COX-2 deletion on apoptosis in atherosclerotic lesions.

Apoptosis was measured by active caspase 3 staining. Mac-COX-2 KO/LdlR-/- aortic sections demonstrated an increased incidence of apoptotic cells.

T Cell COX-2 does not influence atherogenesis

In contrast to the functional importance of COX-2 in myeloid cells, deletion of COX-2 in T cells had no detectable effect on either atherogenesis (Figure 3 B) or weight gain (Supplementary Figure 6 C).

Discussion

Randomized trials have provided evidence that NSAIDs selective for inhibition of COX-2 confer a cardiovascular hazard, explicable in terms of suppression of cardioprotective products of COX-2, particularly PGI2 3. Inhibition or deletion of COX-2 or deletion of the IP augments the response to thrombogenic stimuli 4, elevates systemic 4 and pulmonary 32, 33 blood pressure, disrupts vascular remodeling 34 and predisposes to cardiac failure and arrhythmogenesis 9 in rodents. However, although deletion of the IP retards atherogenesis 5, 6, deletion or inhibition of COX-2 may accelerate, retard or leave unaltered atherogenesis 7. Many cell types, each of which differs in their spectrum of COX-2 products, contribute to or restrain atherogenesis, so that the timing of intervention, as well as efficiency and selectivity of enzyme inhibition might contribute to the variability of the results in rodents. Meantime, despite its established cardiovascular risk 35, and retraction of papers suggesting that upregulation of COX-2 predisposed to destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques in humans 36, 37, a large randomized trial is underway to determine whether the COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, might more favorably influence cardiovascular outcomes than other NSAIDs 38.

Given the contrasting impact of prostanoids formed by COX-2 in different cells on atherogenesis, we have initiated analysis of the functional importance of COX-2 deletion in discrete cell types on disease evolution. In these studies, using LysMCre mice, we found evidence that Mac COX-2 accelerates atherogenesis in the LdlR-/- mice. A surprising finding was that although lesional Mac COX-2 was indeed depleted in the KOs, COX-2 was upregulated in a subset of cells, negative for the macrophage marker, Cd11b, and the pan-leukocyte marker CD45. The origin of these cells remains to be defined, but they have some features of VSMC morphology; they stain positive for VCAM and are heterogeneous with respect to expression of α-SMA and vimentin. We and others have previously shown that prostanoids, such as PGI2 and PGE2 may upregulate COX-2 39, 40. Here, it appeared that either direct products of Mac COX-2 or compounds indirectly regulated by the enzyme act to restrain expression of COX-2 in this subset of VSMCs. This interplay of COX-2 expression between different cell types is reminiscent of the upregulation of COX-2 that we observed in cardiac fibroblasts consequent to cardiomyocyte enzyme deletion 9. Here, this shift in enzyme expression may have had a functional consequence. Thus, while the dominant products of COX-2 in macrophages are thromboxane A2 and PGE2, both of which can accelerate atherogenesis 7, 11, PGI2 is the major COX-2 product of VSMCs and has the opposite effect. For now, this remains speculative. Harvesting such lesional cells in quantities to document product formation is not technically possible. Addressing the hypothetical importance of augmented formation of PGI2 in these mice will be pursued using pharmacological antagonism and genetic deletion of the IP. Narasimha et al have recently reported a failure of Mac COX-2 deletion to modify atherogenesis in ApoE deficient mice 41. COX-2 expression in the lesions of their MacKOs was observed, but the cells involved were not characterized.

While the impact of prostanoids on T cell development and function is well established, the possibility that T cells might themselves generate prostanoids to subserve an autocrine function remains unresolved. Evidence for T cell expression of COX-2, but not of prostanoid product formation has been obtained in autoimmune diseases, 20, 42 although PGE2 production was detected coincident with COX-2 expression in FOXP3+CD4+CD25+ adaptive regulatory T cells (TRadapt) 23 NSAIDs of varied selectivity for inhibition of COX-2 fail to modulate T cell activation, proliferation or susceptibility to apoptosis 25. The present results exclude a major impact of T cell COX-2 on T cell development or function in mice. Furthermore, despite the importance of T cells in atherogenesis 43, 44, there was no detectable effect of COX-2 deletion in T cells on either weight gain or lesion development in hyperlipidemic mice.

In conclusion, Mac COX-2 promotes atherogenesis in LdlR-/- mice, while the enzyme in T lymphocytes has no impact on disease evolution. Targeted deletions of COX-2 are likely to reveal contrasting functional effects of COX-2 in distinct cell types in complex, multicellular diseases, such as atherosclerosis.

Clinical Perspective.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) specific for inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 confer a risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, hypertension and heart failure. Rodent models have established that suppression of COX-2 derived prostacyclin (PGI2) augments thrombogenesis, hypertension and heart failure. An unanswered question is whether delayed emergence of the NSAID hazard in chemoprevention trials selected for patients at low initial cardiovascular risk reflects the risk transformation during chronic drug administration. Deletion of the PGI2 receptor fosters initiation and early development of atherosclerosis in mice.

Attempts to address this issue with COX-2 knock out mice and inhibitors have yielded conflicting results. This may reflect (i) different times of drug initiation and varied selectivity of the regimens employed; (ii) restricted utility of the KOs due to the developmental effects of COX-2 deletion and (iii) contrasting effects of COX-2 products formed by different cells during disease evolution. To begin to address the last possibility, we report that while knock out of T cell COX-2 has no effect, deletion of myeloid COX-2, dominant in macrophages, restrains atherosclerosis. Interestingly, this removes a restraint on enzyme expression in other lesional cells. These are not macrophages and have some hallmarks of vascular smooth muscle cells. If they are, this likely explains the impact on atherogenesis, as it would shift from proatherogenic COX-2 products of macrophages – thromboxane (TxA2) and prostaglandin (PG)E2 - to PGI2 formed by vascular smooth muscle cell COX-2. Elucidation of the cell specific biology of COX-2 deletion may advance the prospect of cell targeted NSAID delivery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the advice and technical support of Jenny Bruce, Gregory Grant, Martha Jordan, Fred Keeney, John Lawson, Wenxuan Li, Thomas Price, Darshini Trivedi, Weili Yan, Ying Yu, Jueli Zeng, Helen Zou and Erica Shwarz, for technical help or advice. We thank Dr. Ira A. Tabas for providing LysMCre mice.

Funding Sources: Supported by grants HL81012, HL083799 and RR023567 from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. FitzGerald is the McNeill Professor of Translational Medicine and Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr FitzGerald has served in the past 5 years as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Biolipox, Daiichi Sankyo, the Genome Institute of the Novartis Foundation, Lilly, Logical Therapeutics, Novartis, Merck and Synosia all of which make drugs targeting the prostaglandin cascade. The other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.Smyth E, Burke A, FitzGerald GA. Lipid-derived autocoids. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG, editors. Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2005. pp. 653–670. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilley SL, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Mixed messages: modulation of inflammation and immune responses by prostaglandins and thromboxanes. J Clin Invest. 2005;108:15–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI13416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosser T, Yu Y, FitzGerald GA. Emotion recollected in tranquility; lessons from the COX-2 saga. Ann Rev Med. 2010;61:17–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-011209-153129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Y, Wang M, Yu Y, Lawson J, Funk CD, Fitzgerald GA. Cyclooxygenases, microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1, and cardiovascular function. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1391–1399. doi: 10.1172/JCI27540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi T, Tahara Y, Matsumoto M, Iguchi M, Sano H, Murayama T, Arai H, Oida H, Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Yamashita JK, Katagiri H, Majima M, Yokode M, Kita T, Narumiya S. Roles of thromboxane A(2) and prostacyclin in the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:784–794. doi: 10.1172/JCI21446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan KM, Lawson JA, Fries S, Koller B, Rader DJ, Smyth EM, Fitzgerald GA. COX-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science. 2004;306:1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egan KM, Wang M, Fries S, Lucitt MB, Zukas AM, Puré E, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Cyclooxygenases, thromboxane and atherosclerosis: plaque destabilization by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition combined with thromboxane receptor antagonism. Circulation. 2005;111:334–342. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153386.95356.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vardeh D, Wang D, Costigan M, Lazarus M, Saper CB, Woolf CJ, Fitzgerald GA, Samad TA. COX-2 in CNS neural cells mediates mechanical inflammatory pain hypersensitivity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:287–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI37098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D, Patel VV, Ricciotti E, Zhou R, Levin MD, Gao E, Yu Z, Ferrari VA, Lu MM, Xu J, Zhang H, Hui Y, Cheng Y, Petrenko N, Yu Y, FitzGerald GA. Cardiomyocyte cyclooxygenase-2 influences cardiac rhythm and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7548–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805806106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li AC, Glass CK. The macrophage foam cell as a target for therapeutic intervention. Nat Med. 2002;8:1235–1242. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, Zukas AM, Hui Y, Ricciotti E, Puré E, FitzGerald GA. Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 augments prostacyclin and retards atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14507–14512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606586103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burleigh ME, Babaev VR, Oates JA, Harris RC, Gautam S, Riendeau D, Marnett LJ, Morrow JD, Fazio S, Linton MF. Cyclooxygenase-2 promotes early atherosclerotic lesion formation in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002;105:1816–1823. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014927.74465.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burleigh ME, Babaev VR, Yancey PG, Major AS, McCaleb JL, Oates JA, Morrow JD, Fazio S, Linton MF. Cyclooxygenase-2 promotes early atherosclerotic lesion formation in ApoE-deficient and C57BL/6 mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Förster I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 1999;8:265–277. doi: 10.1023/a:1008942828960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gualde N, Harizi H. Prostanoids and their receptors that modulate dendritic cell-mediated immunity. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:353–60. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocca B, FitzGerald GA. Cyclooxygenases and prostaglandins: shaping up the immune response. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:603–30. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocca B, Spain LM, Ciabattoni G, Patrono C, FitzGerald GA. Differential expression and regulation of cyclooxygenase isozymes in thymic stromal cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:4589–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocca B, Spain LM, Puré E, Langenbach R, Patrono C, FitzGerald GA. Distinct roles of prostaglandin H synthases 1 and 2 in T-cell development. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1469–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pablos JL, Santiago B, Carreira PE, Galindo M, Gomez-Reino JJ. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 are expressed by human T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:86–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu L, Zhang L, Yi Y, Kang HK, Datta SK. Human lupus T cells resist inactivation and escape death by upregulating COX-2. Nat Med. 2004;10:411–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Bertucci AM, Smith KA, Xu L, Datta SK. Hyperexpression of cyclooxygenase 2 in the lupus immune system and effect of cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor diet therapy in a murine model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:4132–41. doi: 10.1002/art.23054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang P, Zhang Y, Ping L, Gao XM. Apoptosis of murine lupus T cells induced by the selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahic M, Yaqub S, Johansson CC, Taskén K, Aandahl EM. FOXP3+CD4+CD25+ adaptive regulatory T cells express cyclooxygenase-2 and suppress effector T cells by a prostaglandin E2-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2006;177:246–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori N, Inoue H, Yoshida T, Tanabe T, Yamamoto N. Constitutive expression of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene in T-cell lines infected with human T cell leukemia virus type I. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:813–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivero M, Santiago B, Galindo M, Brehmer MT, Pablos JL. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition lacks immunomodulatory effects on T cells. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:379–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song WL, Wang M, Ricciotti E, Fries S, Yu Y, Grosser T, Reilly M, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Tetranor PGDM, an Abundant Urinary Metabolite Reflects Biosynthesis of Prostaglandin D2 in Mice and Humans. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1179–1188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706839200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:175–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heilbronn LK, Campbell LV. Adipose tissue macrophages, low grade inflammation and insulin resistance in human obesity. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1225–30. doi: 10.2174/138161208784246153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell-Parikh LC, Ide T, Lawson JA, McNamara P, Reilly M, FitzGerald GA. Biosynthesis of 15-deoxy-delta12,14-PGJ2 and the ligation of PPARgamma. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:945–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI18012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babaev VR, Bobryshev YV, Stenina OV, Tararak EM, Gabbiani G. Heterogeneity of smooth muscle cells in atheromatous plaque of human aorta. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:1031–1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuff CA, Kothapalli D, Azonobi I, Chun S, Zhang Y, Belkin R, Yeh C, Secreto A, Assoian RK, Rader DJ, Puré E. The adhesion receptor CD44 promotes atherosclerosis by mediating inflammatory cell recruitment and vascular cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1031–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cathcart MC, Tamosiuniene R, Chen G, Neilan TG, Bradford A, O'Byrne KJ, Fitzgerald DJ, Pidgeon GP. COX-2-Linked Attenuation of Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension and Intravascular Thrombosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:51–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.134221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fredenburgh LE, Liang OD, Macias AA, Polte TR, Liu X, Riascos DF, Chung SW, Schissel SL, Ingber DE, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S, Perrella MA. Absence of cyclooxygenase-2 exacerbates hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and enhances contractility of vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2008;117:2114–2122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudic RD, Brinster D, Cheng Y, Fries S, Song WL, Austin S, Coffman TM, FitzGerald GA. COX-2 derived prostacyclin modulates vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2005;96:1240–1247. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000170888.11669.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon SD, Wittes J, Finn PV, Fowler R, Viner J, Bertagnolli MM, Arber N, Levin B, Meinert CL, Martin B, Pater JL, Goss PE, Lance P, Obara S, Chew EY, Kim J, Arndt G, Hawk E. Cross Trial Safety Assessment Group. Cardiovascular risk of celecoxib in 6 randomized placebo-controlled trials: the cross trial safety analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:2104–2113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.764530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cipollone F, Prontera C, Pini B, Marini M, Fazia M, De Cesare D, Iezzi A, Ucchino S, Boccoli G, Saba V, Chiarelli F, Cuccurullo F, Mezzetti A. Overexpression of functionally coupled cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E synthase in symptomatic atherosclerotic plaques as a basis of prostaglandin E(2)-dependent plaque instability. Circulation. 2001;104:921–927. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.093152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cipollone F, Fazia M, Iezzi A, Ciabattoni G, Pini B, Cuccurullo C, Ucchino S, Spigonardo F, De Luca M, Prontera C, Chiarelli F, Cuccurullo F, Mezzetti A. Balance between PGD synthase and PGE synthase is a major determinant of atherosclerotic plaque instability in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1259–1265. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133192.39901.be. Withdrawn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Couzin J. Massive trial of celebrex seeks to settle safety concerns. Science. 2005;310:1890–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.310.5756.1890a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barry OP, Praticò D, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Transcellular activation of platelets and endothelial cells by bioactive lipids in platelet microparticles. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2118–2127. doi: 10.1172/JCI119385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faour WH, He Y, He QW, de Ladurantaye M, Quintero M, Mancini A, Di Battista JA. Prostaglandin E(2) regulates the level and stability of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in interleukin-1 beta-treated human synovial fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31720–31731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narasimha AJ, Watanabe J, Ishikawa TO, Priceman SJ, Wu L, Herschman HR, Reddy ST. Absence of Myeloid COX-2 Attenuates Acute Inflammation but Does Not Influence Development of Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E Null Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):260–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.198762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kainulainen H, Rantala I, Collin P, Ruuska T, Päivärinne H, Halttunen T, Lindfors K, Kaukinen K, Mäki M. Blisters in the small intestinal mucosa of coeliac patients contain T cells positive for cyclooxygenase 2. Gut. 2002;50:84–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson AK, Hansson GK. T cells in atherogenesis: for better or for worse? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2421–32. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000245830.29764.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:508–19. doi: 10.1038/nri1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.