Abstract

Helicobacter pylori VacA is a pore-forming toxin that causes multiple alterations in human cells and contributes to the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. The toxin is secreted by H. pylori as an 88 kDa monomer (p88) consisting of two domains (p33 and p55). While an X-ray crystal structure for p55 exists and p88 oligomers have been visualized by cryo-electron microscopy, a detailed analysis of p33 has been hindered by an inability to purify this domain in an active form. In this study, we expressed and purified a recombinant form of p33 under denaturing conditions and optimized conditions for the refolding of soluble protein. We show that refolded p33 can be added to purified p55 in trans to cause vacuolation of HeLa cells and inhibition of IL-2 production by Jurkat cells, effects identical to those produced by the p88 toxin from H. pylori. The p33 protein markedly enhances the cell-binding properties of p55. Size exclusion chromatography experiments suggest that p33 and p55 assemble into a complex consistent with the size of a p88 monomer. Electron microscopy of these p33/p55 complexes reveals small rod-shaped structures that can convert to oligomeric flower-shaped structures in the presence of detergent. We propose that the oligomerization observed in these experiments mimics the process by which VacA oligomerizes when in contact with membranes of host cells.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that persistently colonizes the human stomach (1–4). Infection by H. pylori is associated with the development of peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric lymphoma (5–6). An important virulence factor in the pathogenesis of H. pylori infection is a secreted protein known as vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) (7–11). In vivo studies have shown that VacA contributes to gastric damage in animal models (12–13), and specific vacA allelic forms are associated with an increased risk of disease in humans (14–15). VacA causes a wide range of cellular alterations in vitro (9), including the formation of large cytoplasmic vacuoles (7–8), permeabilization of the plasma membrane (16), reduction of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and cytochrome c release (17–18), activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (19), induction of autophagy (20), and inhibition of the activation and proliferation of T-lymphocytes (21–23). Many cellular effects of VacA are dependent on the formation of anion-selective membrane channels (9, 16, 24–25). VacA-induced cell vacuolation, the hallmark effect of VacA on epithelial cells, results from internalization of VacA and expansion of late endosomal compartments (9, 26). VacA-induced suppression of IL-2 production, a prominent effect of VacA on Jurkat T cells, is attributed to inhibited nuclear translocation of NFAT (21).

The vacA gene encodes a 140 kDa protein that undergoes proteolytic processing to yield an amino-terminal signal sequence, an 88 kDa secreted toxin, and a carboxyl-terminal autotransporter domain (13, 27–29). Partial proteolytic digestion in vitro of the 88 kDa secreted toxin yields two fragments, designated p33 and p55, which probably represent two domains of VacA (13, 30–32). Cleavage of the p88 protein into these two fragments occurs at a site that is predicted to be a surface-exposed flexible loop (13, 31). Amino acid sequences within an amino-terminal hydrophobic portion of the p33 domain are required for membrane channel formation (33–34), and sequences within the p55 domain are required for VacA binding to cells (35–37). When expressed intracellularly in HeLa cells, about 422 residues (corresponding to the p33 domain and the amino-terminal portion of the p55 domain) are sufficient to cause cell vacuolation (38). Intracellularly-expressed p33 localizes in association with mitochondria, whereas p55 does not (17). The crystal structure of p55 was recently analyzed and shown to consist predominantly of a right-handed parallel beta-helix (39), a property that is shared among most autotransporter passenger domains (39–41). It is predicted that a large portion of p33 also comprises a beta-helical fold (39), but thus far, detailed studies of p33 have been hindered by an inability to purify an active form of this domain.

The 88 kDa VacA monomers secreted by H. pylori can assemble into large water-soluble oligomeric complexes (42–45). These flower-shaped structures can be either single-layered (containing 6–9 subunits) or bilayered (containing 12–14 subunits) (42–45). Similar oligomeric structures have been visualized on the surface of VacA-treated cells or lipid bilayers (24, 44, 46). Amino acid sequences within both the p33 domain (residues 49–57) and p55 domain (residues 346–347) are required for assembly of VacA into these oligomeric structures, and mutant proteins lacking these sequences fail to cause cell vacuolation (47–48). Several VacA mutant proteins have dominant negative inhibitory effects on the ability of wild-type VacA to cause cellular alterations (33, 48–50), which supports the hypothesis that oligomeric structures are required for VacA effects on host cells. Water-soluble VacA oligomeric complexes lack cytotoxic activity unless they are first dissociated into monomeric components by exposure to low pH or high pH conditions (42, 51), and therefore, it is presumed that VacA monomeric components interact with host cells and subsequently reassemble into membrane channels. Although the structure of water-soluble VacA oligomeric complexes has been investigated in detail, the conditions that promote oligomerization of VacA are not well-understood.

In this study, we describe the expression and purification of a recombinant form of p33 that, when mixed with p55, causes cellular alterations identical to those caused by p88 VacA from H. pylori. We report that p33 and p55 assemble into a complex consistent with the size of a p88 monomer, and that p33 markedly enhances the cell-binding properties of p55. Furthermore, we report that, in the presence of detergent, p33 and p55 assemble into oligomeric structures that resemble the oligomeric complexes formed by p88 VacA from H. pylori. We discuss the importance of this assembly in the process by which VacA intoxicates human cells, and in addition, we discuss the distinctive structural properties of VacA that allow reconstitution of a functional protein from two individually-expressed component domains.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Purification of p88 VacA from H. pylori broth culture supernatant

H. pylori strain 60190 (expressing wild-type VacA) and a strain expressing a VacAΔ6-27 mutant protein were grown in broth culture, and VacA proteins were purified in an oligomeric form from the culture supernatant as described previously (33, 42). These preparations of purified VacA oligomers were acid-activated prior to use in cell culture experiments (42, 51).

Plasmids for expression of p33 and p55 VacA fragments

Plasmids encoding the p33 and p55 domains of VacA from H. pylori strain 60190 (a type s1/m1 form of VacA; GenBank accession number Q48245), as well as a c-Myc-tagged p33 protein and a p33Δ6-27 mutant protein, have been described previously (27, 32, 39, 49). The p33 proteins contain a C-terminal hexa-histidine tag and the p55 protein contains an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag.

Expression and purification of recombinant VacA proteins

VacA p55 was purified as described previously (39). VacA p33 was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) by culturing in Terrific broth (Fisher) supplemented with 25 µg of kanamycin/ml (TB-KAN) at 37°C overnight with shaking. A c-Myc-tagged form of p33 (32) was expressed in the same manner. Cultures were diluted 1:100 in TB-KAN and grown at 37°C until they reached an absorbance (A600) of 0.6. Cultures were induced with a final isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) concentration of 0.5 mM and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours.

VacA p33 proteins were purified from inclusion bodies. Briefly, IPTG-induced cultures were pelleted, washed in 0.9% NaCl, and resuspended (10 ml per liter of culture) in sonication buffer [10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, protease inhibitor (Roche), and lysozyme 20,000 U/ml (Ready-lyse, Epicentre)]. The cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes with shaking, and sonicated with six 20 watt bursts (45 seconds per burst with 15 second cooling periods). Lysed bacterial cells were centrifuged to pellet the inclusion bodies. The insoluble inclusion body pellet was resuspended in buffer containing 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, and 8 M urea (pH 8.0) at 5 ml per gram wet weight, and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. The samples were centrifuged, and the resulting supernatant was added to Ni-NTA beads (Novagen) at a ratio of 4 ml of supernatant per 1 ml of beads. The protein-bead mixture was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature before loading it into a column. The column was washed with 10 column volumes of 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, 10 mM imidazole, and 8 M urea (pH 6.3), followed by 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, and 8 M urea (pH 5.9). The p33 protein was eluted from the column with 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, and 8 M urea (pH 4.5). Successful expression and purification of p33 was confirmed by mass spectrometry (data not shown).

Refolding of VacA p33

The denatured VacA p33 protein was refolded by dialyzing the protein against a buffer containing 55 mM Tris, 21 mM NaCl, 0.88 mM KCl, 1.1 M guanidine, and 880 mM arginine (pH 8.2) for 24 hours. The protein then was dialyzed in two other buffers, each for 24 hours. The first reduced the guanidine to 800 mM and the arginine to 500 mM, and the second reduced the arginine to 250 mM and maintained an 800 mM guanidine concentration (52). Further reductions in the arginine or guanidine concentrations resulted in precipitation of p33 VacA.

Cell culture assays

HeLa cells were grown in minimal essential medium (modified Eagle’s medium containing Earle’s salts) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Jurkat lymphocytes (clone E6-1) (ATCC TIB-152) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 1.5 g/liter sodium bicarbonate, 4.5 g/l glucose, 10 mM HEPES and 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate supplemented with 10% FBS.

For vacuolating assays, HeLa cells were seeded at 1.2 × 10 4 cells/well into 96-well plates 24 hours prior to the addition of VacA proteins. The recombinant p33 and p55 proteins (each at 1 mg/ml) were pre-mixed at a 1:1 mass ratio, which corresponds to about a 1.7:1 molar ratio. The use of excess p33 on a molar basis compensated for the possibility that refolding of denatured p33 might be less than 100% efficient. Preparations of purified p33, p55 or the p33/p55 mixture were then added to the tissue culture medium overlying HeLa cells (supplemented with 10 mM ammonium chloride) and incubated overnight at 37°C. VacA-induced cell vacuolation was detected by inverted light microscopy and quantified by neutral red uptake assay, a well-established method that is based on rapid uptake of neutral red into VacA-induced cell vacuoles (8, 53). For dominant negative assays, we tested the ability of the refolded p33 Δ6-27 protein or the purified H. pylori p88 Δ6-27 protein to inhibit the activity of wild-type VacA (33, 49). To analyze VacA effects on T cells, we analyzed the capacity of VacA to inhibit IL-2 secretion by Jurkat T cells (21). Jurkat cells were plated at 1 × 105 cells/well, and the recombinant p33 and p55 were added to cells either individually or as a p33/p55 mixture (1:1 mass ratio) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After incubation, 0.05 µg/ml of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and 0.5 µg/ml of ionomycin were added for 24 hours at 37°C. The cells were then centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 7 minutes and the supernatants were tested for IL-2 by ELISA, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems Human IL-2 Immunoassay) (54).

Interactions of p33 and p55 with HeLa cells

Purified p55 was labeled with Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HeLa cells were incubated with Alexa 488-labeled p55 alone (10 µg/ml) or a mixture of labeled p55 plus purified refolded p33 (5 µg/ml of each) at 37°C degrees. Alternatively, cells were incubated with purified Alexa 488-labeled p55 plus a c-Myc-tagged p33 protein (32) that was purified and refolded using the same methodology described above for p33. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. The c-Myc-tagged p33 protein was detected by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-c-Myc antibody and an Alexa fluor-555 conjugated secondary antibody. Cells were viewed with an LSM 510 Inverted confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Size exclusion chromatography

Gel filtration was performed using either Superdex 200 10/300 GL high-resolution resin or Superdex 200 10/300 prep grade resin, equilibrated in 55 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 21 mM NaCl, 0.88 mM KCl, 800 mM guanidine, and arginine (either 800 mM or 250 mM). Protein samples were first injected onto the gel filtration column individually at a final concentration of 0.75 mg/ml for the p33 protein and 0.4 mg/ml for the p55 protein. To analyze p33/p55 mixtures, the appropriate sizing column fractions corresponding to either p33 or p55 were each concentrated to 1 mg/ml. VacA p33 was added to p55 in a 2:1 v/v ratio, the mixture incubated for 45 minutes at 4°C, and the p33/p55 mixture was then applied to a gel filtration column. Retention volumes of bovine thyroglobulin, alcohol dehydrogenase, bovine serum albumin, and carbonic anhydrase were used as standards to calculate the molecular masses of the purified VacA proteins.

Electron microscopy

To visualize the morphology of p33/p55 mixtures, appropriate gel filtration fractions containing these proteins were analyzed by electron microscopy (EM) using conventional negative staining as described (55). Protein solutions were diluted to appropriate final concentrations (25 to 100 µg/ml) and 2.5 µl aliquots were spotted onto glow-discharged copper-mesh grids (EMS) for approximately 1 min. In some experiments, p33/p55 mixtures were mixed 9:1 (v/v) with Brucella broth (56) or n-dodecyl beta-D-maltoside (DDM, Anatrace) prior to EM analysis. The final concentration of DDM was 0.34 mM, which corresponds to twice the critical micelle concentration. The grids were washed in 5 drops of water followed by one drop of 0.7% uranyl formate. Grids were then incubated on one drop of 0.7% uranyl formate for 1 min, blotted against filter paper and allowed to air dry. Initial images of wild-type p88 or p33/p55 mixed with Brucella broth were collected on an FEI morgagni run at 100 kV at a magnification of 36,000×. Images were recorded on an ATM 1K×1K CCD camera. Images of p88 used for multi-reference alignment were collected on a FEI 120 KV electron microscope at a magnification of 67,000×. Images were recorded on DITABIS digital imaging plates (Pforzheim, Germany). The plates were scanned on a DITABIS micron scanner (Pforzheim, Germany), converted to mixed raster content (mrc) format, and binned by a factor of 2 yielding final images with 4.48 Å/pixel. Images of p33/p55 in DDM purified by gel filtration were taken on a 200 kV FEI electron microscope equipped with a field emission electron source and operated at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV at a magnification of 100,000×. Images were collected using a Gatan 4K×4K CCD camera. CCD images were converted to mrc format and binned by a factor of 4 resulting in final images with 4.26Å/pixel. Images of both p88 and p33/p55 were taken under low-dose conditions using a defocus value of −1.5 um.

For alignment and averaging of p88 VacA and p33/p55 VacA in DDM, 9,871 and 1,273 images of p88 and p33/p55 VacA particles, respectively, were selected with Boxer and windowed with a 120 pixel side length (57). Image analysis was carried out with SPIDER and the associated display program WEB (58). The images were rotationally and translationally aligned and subjected to 10 cycles of multi-reference alignment and K-means classification. For analysis of p88 VacA, alignment particles were first classified into 20 class averages (data not shown) and 7 representative classes then were chosen as references for another cycle of multi-reference alignment. For analysis of p33/p55 VacA, particles were first classified into 10 class averages (data not shown) and then four representative projections were chosen as references for another cycle of multi-reference alignment.

RESULTS

Expression, purification and refolding of recombinant p33 VacA

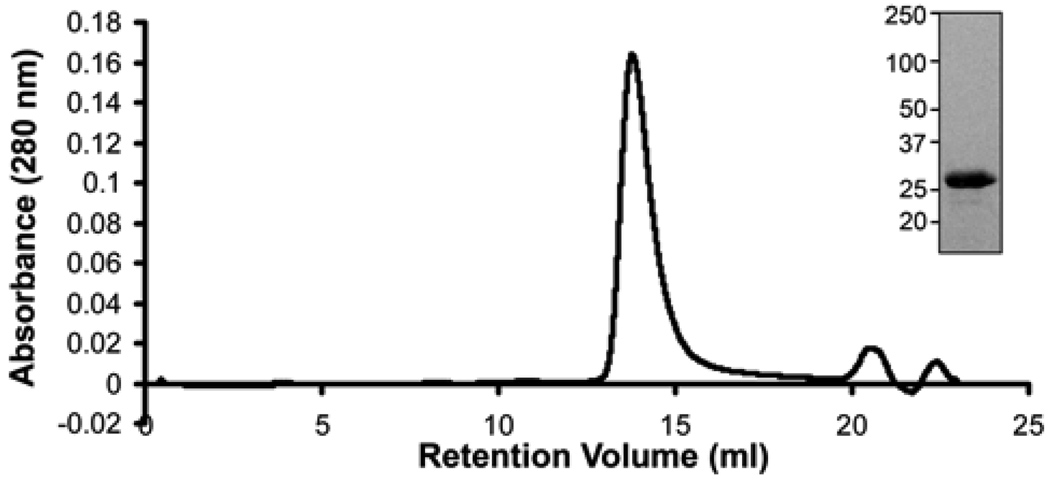

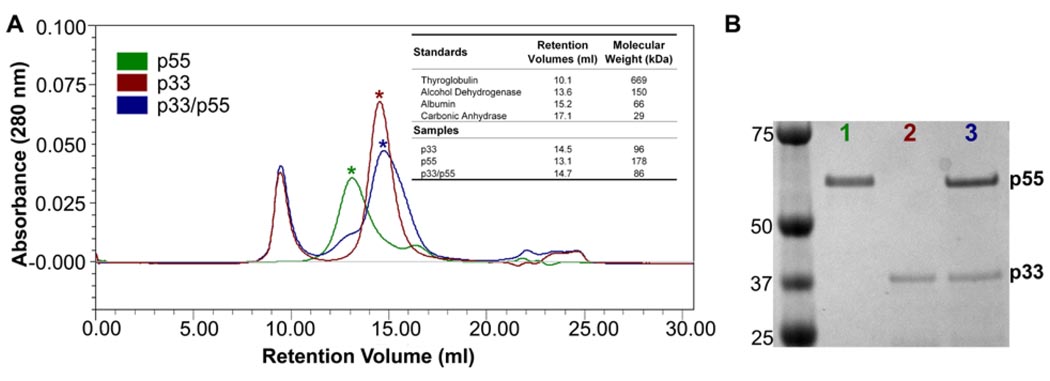

In previous studies, it has not been possible to purify a functionally active form of the p33 domain (32). We attempted to purify the p33 VacA fragment from E. coli extracts under native conditions but were unsuccessful. Therefore, we expressed and purified the recombinant 12 p33 under denaturing conditions and then used dialysis to reduce the concentration of denaturants and allow the protein to refold. After the p33 protein was refolded, it eluted as a well-defined peak by size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Purification of recombinant p33 VacA. SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue stain of p33 VacA purified under denaturing conditions (inset). Gel filtration chromatography (Superdex 200 10/300 GL high-resolution resin) of p33 VacA after protein refolding, using buffer containing 800 mM guanidine and 800 mM arginine, as described in Experimental Procedures.

Refolded p33 mixed with purified p55 causes cellular alterations

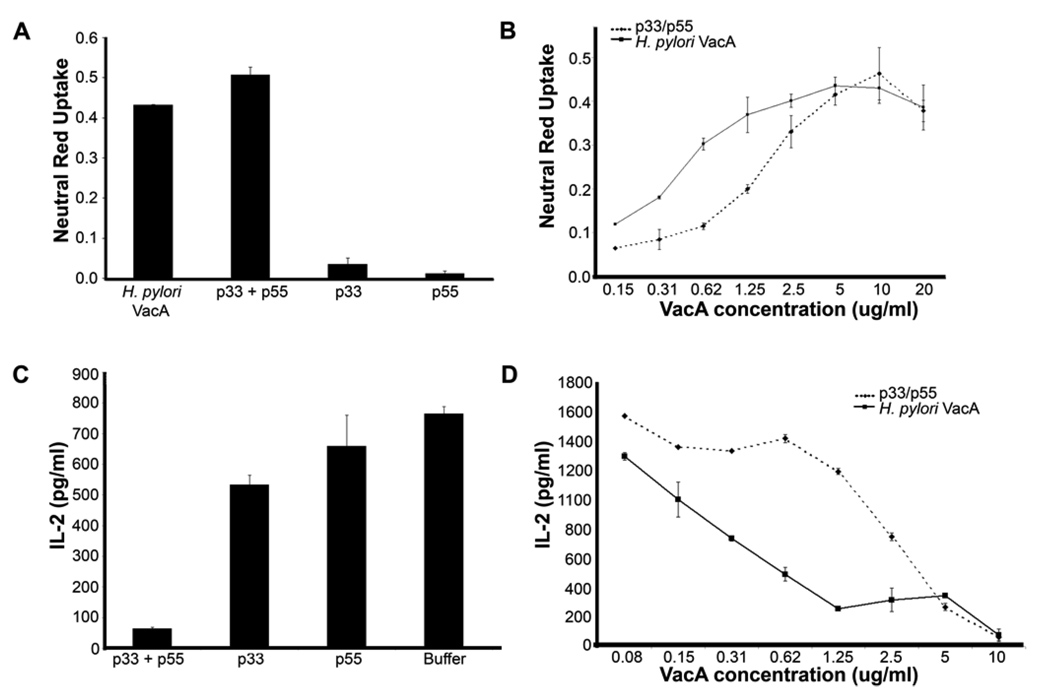

To test the activity of the purified p33 and p55 proteins, we added these proteins individually and in combination to HeLa cells, and analyzed the capacity of the proteins to cause cell vacuolation, a hallmark of VacA activity. No detectable vacuolating activity was observed when the p33 or p55 protein was added to cells individually, as demonstrated by neutral red uptake assay and light microscopic examination of the cells (Fig. 2A and data not shown). Similarly, none of the buffers alone or in combination exhibited any detectable activity (data not shown). In contrast, a mixture of the purified p33 and p55 proteins caused extensive vacuolation of HeLa cells (Fig. 2A and 2B). The potency of the p33/p55 mixture was slightly lower than that of the p88 VacA protein purified from H. pylori broth culture supernatant (Fig. 2B). A mixture of p55 plus heat-denatured p33 failed to cause any detectable effects on cells (data not shown).

Figure 2.

A–D. Effects of p33 and p55 VacA proteins on HeLa cells and Jurkat cells. Purified refolded p33 and purified p55 (each 1 mg/ml) were mixed together in a 1:1 mass ratio, which ensured an excess of p33 on a molar basis. The p88 VacA protein purified from H. pylori culture supernatant was acid-activated prior to contact with cells (42, 51), whereas the p33 and p55 preparations were not acid-activated. (A) HeLa cells were incubated with the purified VacA proteins at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml (or 5 µg/ml of each protein in the case of p33/p55 mixture). Cell vacuolation was quantified by neutral red uptake assay (OD 540 nm). (B) HeLa cells were incubated with the indicated final concentrations of a p33/p55 mixture (20 µg/ml corresponds to 10 µg/ml p33 and 10 µg/ml p55), or the p88 form of VacA purified from H. pylori broth culture supernatant. Cell vacuolation was quantified by neutral red uptake assay. (C) Jurkat cells were incubated with the indicated purified VacA proteins at a concentration of 6 µg/ml (or 3 µg/ml of each protein in the case of the p33/p55 mixture) for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then stimulated and IL-2 secretion was measured as described in Experimental Procedures. (D) Jurkat cells were incubated with the indicated final concentrations of a p33/p55 mixture or the p88 form of VacA purified from H. pylori culture supernatant. The cells were then stimulated and IL-2 secretion was measured as described in Experimental Procedures. Results represent mean ± standard deviation, based on analysis of triplicate samples.

Previous studies have shown that VacA from H. pylori inhibits production of IL-2 by Jurkat cells (21). To test whether p33 and p55 proteins exhibit a similar activity, we incubated Jurkat cells with the purified p33 and p55 proteins individually and in combination. When added individually, neither p33 nor p55 had any effect on IL-2 secretion (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the p33/p55 mixture inhibited IL-2 secretion from Jurkat cells (Fig. 2C and 2D). The potency of the p33/p55 mixture was slightly lower than that of the p88 VacA protein purified from H. pylori (Fig. 2D). Collectively, these results indicate that the refolded p33 protein, when mixed with the p55 protein, is biologically active and capable of causing alterations in eukaryotic cells.

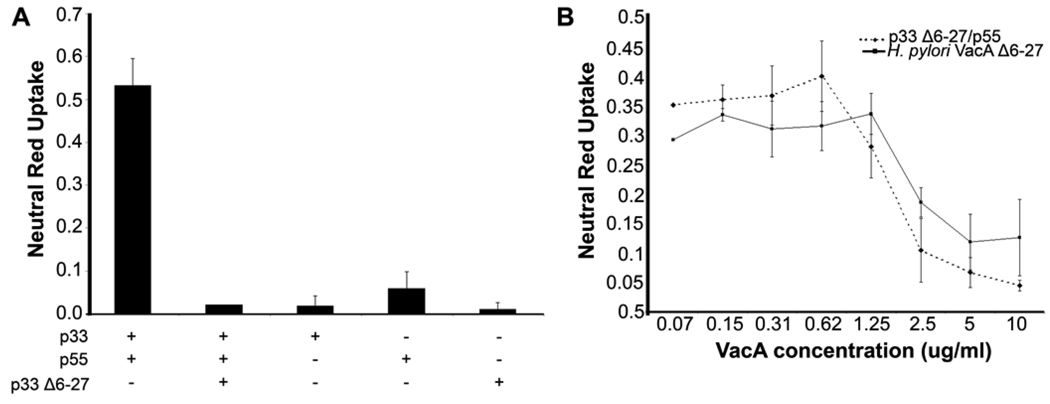

Refolded p33 Δ6-27 exhibits a dominant negative effect

When certain mutant VacA proteins (e.g. VacA Δ6 -27) are mixed with wild type VacA, the mutant proteins can act as dominant negative inhibitors of wild-type VacA activity (33, 47–50). To further validate the new methods for expression and refolding of p33 proteins, we expressed, purified and refolded the p33Δ6 -27 protein under the same conditions used for purification and refolding of the p33 wild-type protein. When added to cells individually or in combination with purified p55, the p33Δ6 -27 protein did not cause detectable cell vacuolation (Fig. 3A). To test for dominant negative properties of the mutant protein, we pre-mixed the p33 Δ6-27 protein with p33/p55 mixtures that were known to be active (Fig. 3A). When this p33/p55/p33Δ6-27 mixture was added to cells, no detectable vacuolation was observed, indicating that the mutant protein exhibited a dominant negative effect (Fig. 3A). The purified refolded p33Δ6 -27 protein, when mixed with purified p55, exhibited dominant-negative inhibitory properties similar to those of the p88Δ6 -27 protein purified from H. pylori broth culture supernatant (Fig. 3B) (33, 49).

Figure 3.

A&B. Refolded p33 Δ6-27 exhibits dominant negative properties. (A) VacA p33 Δ6-27 was purified and refolded as described in Experimental Procedures. Purified p33 Δ6-27 was mixed with p55 and p33 (each 1 mg/ml) at a 1:1:1 mass ratio. HeLa cells were then incubated with the indicated recombinant VacA proteins (either individually or in a mixture) at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml for 9 hours at 37°C. Cell vacuolation was quantified by neutral red uptake assay. (B) Wild-type p88 VacA (5 µg/ml) was incubated with the indicated concentrations of the VacA p33Δ6-27/p55 mixture or the p88 Δ6-27 VacA protein purified from H. pylori culture supernatant. Cell vacuolation was quantified by neutral red uptake assay. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation, based on analysis of triplicate samples.

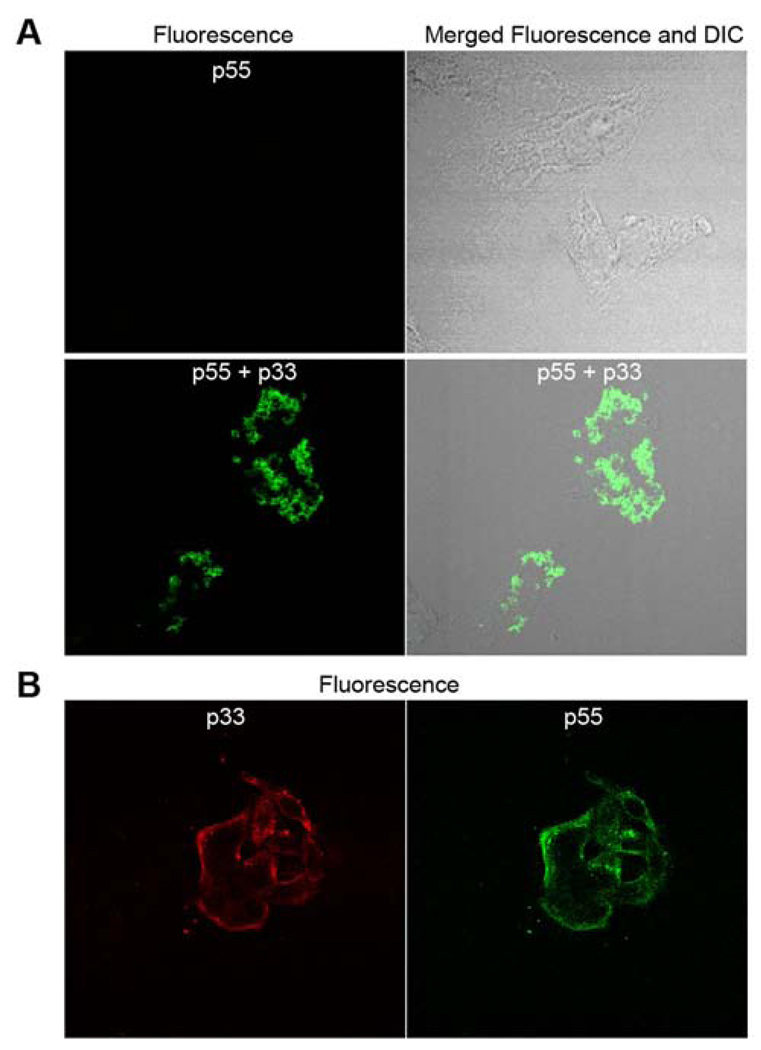

Interactions of p33 and p55 with HeLa cells

Several previous studies have shown that sequences within the p55 domain contribute to the binding of p88 VacA to cells, and it has been suggested that p55 functions as a cell-binding domain (35–37). To investigate the cell-binding properties of p55 in further detail, we incubated HeLa cells with purified fluorescently-labeled p55. Very little if any interaction of purified p55 with HeLa cells was observed (Figure 4A). In contrast, when p55 was incubated with HeLa cells in the presence of purified refolded p33, a marked increase in the binding and uptake of p55 by cells was observed (Figure 4A). Thus, p33 markedly enhanced the cell-binding properties of p55. Further studies indicated that when a mixture of p33 and p55 was incubated with cells, both p33 and p55 bound to the cell surface (Figure 4B). These properties of purified p33 and p55 proteins are consistent with previously observed properties of p33 and p55 proteins contained in crude E. coli extracts (32).

Figure 4.

A&B. Interaction of p55 and p33 proteins with HeLa cells. (A) HeLa cells were incubated with Alexa 488-labeled p55 alone (10 µg/ml) or a mixture of labeled p55 plus purified refolded p33 (5 ug/ml of each) for 4 h at 37°C degrees. Cells were imaged as described in the Experimental Procedures. (B) Cells were incubated with purified Alexa 488-labeled p55 plus purified refolded c-Myc-tagged p33 protein for 1 h at 37°C. The c-Myc-tagged p33 protein was detected by indirect immunofluorescence.

Interaction of refolded p33 with purified p55

To investigate potential interactions among the purified p33 and p55 proteins, we performed size exclusion chromatography experiments. When the refolded wild-type p33 protein was analyzed, a peak with a predicted mass of about 96 kDa was observed (Fig. 5, red peak with star). When the purified p55 protein was analyzed, a peak with a molecular mass of 178 kDa was observed (Fig. 5, green peak with star). When the p33/p55 mixture was analyzed, a peak with a predicted mass of 86 kDa was observed (Fig. 5, blue peak with star), the 96 kDa peak (corresponding to p33 alone) was lost, and the 178 kDa peak (corresponding to p55 alone) was minimized. Representative fractions were tested by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining; this revealed an approximate 33 kDa band for the VacA 96 kDa peak, a 55 kDa band for the 178 kDa peak, and two protein bands of 33 kDa and 55 kDa for the 86 kDa peak (Fig. 5B). When tested in cell culture assays, the p33/p55 mixture corresponding to the blue peak in Fig. 5 caused cell vacuolation with a potency similar to that shown in Fig. 2B (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that the refolded p33 protein interacts with the purified p55 protein to yield a p33/p55 complex. Moreover, these data suggest that p33 homo-oligomers and p55 homo-oligomers must undergo disassembly in order to interact with each other and form 88 kDa p33/p55 complexes.

Figure 5.

A&B. Analysis of p33 and p55 proteins by gel filtration. (A) Size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 10/300 prep grade resin) of refolded p33 (red peak), purified p55 (green peak) or a mixture of the two proteins (blue peak). Refolded p33 and purified p55 (each 1 mg/ml) were mixed at a 2:1 mass ratio and injected into the sizing column, as described in Materials and Methods. The buffer contained 800 mM guanidine and 250 mM arginine, which were required to maintain solubility of the p33 protein. The inset shows retention volumes of p33, p55, and the p33/p55 mixture in comparison to standard proteins. (B) The lower-molecular-mass peaks (stars) from each of the size exclusion chromatography experiments shown in panel A were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

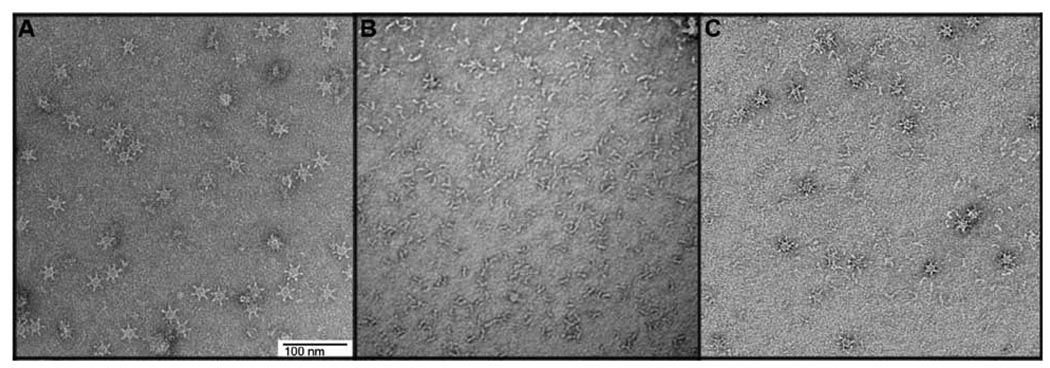

Assembly of p33/p55 complexes into oligomeric structures

The p88 VacA protein secreted by H. pylori can assemble into water-soluble oligomers (42–45). To investigate the possibility that p33 and p55 domains might assemble into similar structures, we visualized the p33/p55 mixture (purified by gel filtration as a monomeric complex) by EM. VacA p88 oligomers purified from H. pylori culture supernatant (and exchanged into guanidine- and arginine-containing buffer by gel filtration) were analyzed as a control. As expected, large flower-like structures were visualized in preparations of H. pylori p88 VacA (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the p33/p55 mixture consisted mainly of small rod-like particles (Fig. 6B), similar to the appearance of p88 monomers produced by H. pylori (42–43).

Figure 6.

A–C. Assembly of p33 and p55 proteins into oligomeric structures. EM analysis of (A) p88 purified from H. pylori culture supernatant, and then exchanged into a guanidine-containing buffer by gel filtration, or (B) a mixture of refolded p33 and p55 eluted from the sizing column (corresponding to Fig. 5A, blue peak with star). (C) The p33/p55 preparation shown in panel B was mixed with Brucella broth as described in Methods and then analyzed by EM. The images in this figure represent analysis of at least 3 grids for each condition and analysis of >10 fields per grid. Scale bar, 100 nm for all panels.

To explain why p88 proteins in H. pylori broth culture supernatant readily assemble into flower-like oligomeric structures whereas purified p33 and p55 proteins do not, we hypothesized that the broth culture medium used for growth of H. pylori (a nutrient-rich medium prepared from yeast extract and animal tissue, known as Brucella broth) might contain factors that promote VacA oligomerization. To test this hypothesis, we examined the appearance of the p33/p55 mixture by EM, either in the presence or absence of added Brucella broth. In the presence of added Brucella broth, increased formation of flower-shaped complexes was detected (Fig. 6C). These experiments indicated that Brucella broth stimulates the oligomerization of p33/p55 mixtures into oligomeric structures similar to those formed by p88 VacA from H. pylori.

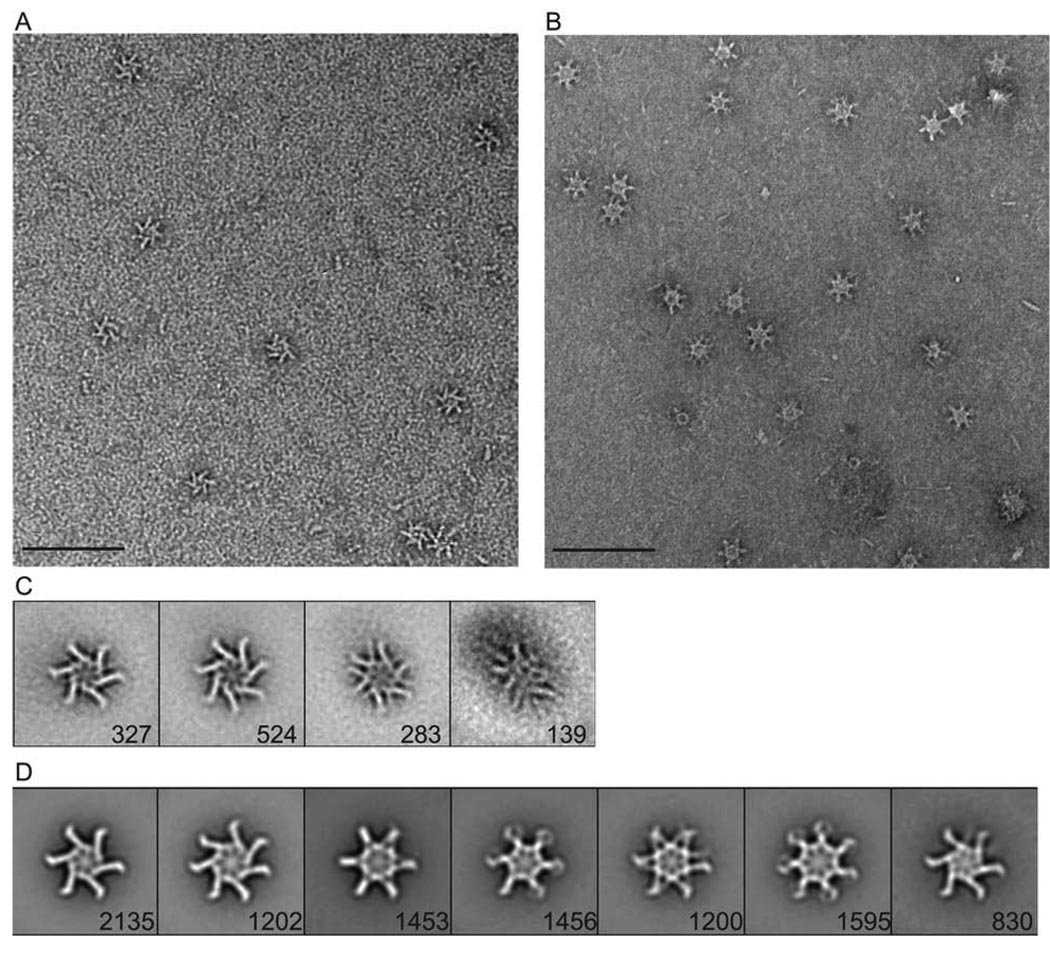

High-resolution imaging of p33/p55 oligomeric complexes

We reasoned that the complex mixture of components in Brucella broth, including numerous membrane-derived factors, promoted the formation of flower-like oligomers. In an effort to stimulate VacA oligomerization using more refined conditions, we incubated p33/p55 mixtures with various additives designed to create an amphipathic environment, including bovine heart total extract solubilized in chloroform, chloroform alone, and the detergent dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM). Each of these additives promoted oligomerization of the p33/p55 monomeric complexes into flower-like oligomeric structures (data not shown). The VacA oligomers formed in the presence of bovine heart extract or chloroform had a more heterogeneous appearance than the VacA oligomers formed in the presence of DDM, and therefore, we studied the latter oligomers in further detail. To permit higher resolution imaging, p33/p55 monomeric complexes (corresponding to the 86 kDa blue peak in Fig. 5) were mixed with DDM, dialyzed, and passed over a gel filtration column in the presence of DDM and arginine and the absence of guanidine. Under these conditions, the 86 kDa peak was minimized and a high-molecular mass (>300 kDa) peak was observed (data not shown). High-molecular mass complexes containing wild-type p33 and p55 were isolated and analyzed further by EM. The appearance of these oligomers (Fig. 7A) was similar to that of p88 oligomers isolated from H. pylori broth culture supernatant (Fig. 7B). To further characterize the structural features of p33/p55 oligomers, approximately 1,300 particles were classified into 10 groups and four classes were chosen as references for an additional round of reference based-alignment (Fig. 7C and data not shown). To directly compare the structural organization of p33/p55 oligomers with that of p88 oligomers purified from H. pylori broth culture supernatant, class averages of p88 oligomers were also generated. Because p88 oligomers seemed to adopt a larger number of conformations than p33/p55 oligomers, a larger number of p88 images were classified. Approximately 10,000 particles of p88 VacA were classified into 20 class averages (data not shown) and seven classes were chosen for an additional round of reference based-alignment (Fig. 7D and data not shown).

Figure 7.

A–D. Analysis of p33/p55 VacA oligomers in negative stain. Mixtures of refolded p33 and p55 eluted from the sizing column (corresponding to Fig. 5A, blue peak with star) were mixed with DDM, and then dialyzed overnight in buffer containing 55 mM Tris pH 8.0, 21 mM NaCl, 0.88 mM KCl, 250 mM arginine, and DDM. The protein was passed over a gel filtration column that was equilibrated with dialysis buffer containing DDM, and VacA oligomers eluting in a high-molecular-mass fraction were then analyzed by EM. (A) Representative image of negative stained p33/p55 VacA oligomers eluting in a high-molecular-mass fraction. Scale bar, 100 nm. (B) Representative image of negative stained p88 VacA oligomers isolated from H. pylori broth culture supernatant. Scale bar, 100 nm. (C) Four class averages of p33/p55 VacA particles in negative stain generated from reference-based alignment. The number of particles in each projection average is shown in the lower right corner of each average. Side length of individual panels is 511 Å. (D) Seven representative class averages of p88 VacA particles in negative stain generated from reference-based alignment. The number of particles in each projection average is shown in the lower right corner of each average. Side length of individual panels is 538 Å.

The result of the p33/p55 alignment (Fig. 7C) shows that the majority of the p33/p55 oligomers are composed of six or seven subunits (67%, Fig. 7C, panels 1 and 2), with one smaller class composed of an oligomer with 12 visible subunits (22%, Fig. 7C, panel 3), and one class representing poorly formed oligomers (Fig. 7C, panel 4). The 12-subunit complex may represent a double-layered oligomer with the two layers splayed (43–44). The overall appearances of hexameric and heptameric p33/p55 oligomers are reminiscent of single-layer hexameric and heptameric oligomers formed by p88 VacA (Fig. 7D, panels 1 and 2) (42–44). These single-layered oligomers exhibit a striking chirality, which suggests that one surface adsorbs preferentially to the support film. In contrast to the p33/p55 oligomers, a majority of the p88 oligomers exist as double-layered complexes containing 12–14 subunits (Fig. 7D, panels 3 though 6) (42–44). Importantly, difference maps created between averages of p33/p55 and p88 single-layer heptameric and hexameric oligomers did not show any statistically relevant difference peaks (data not shown), which indicates that these oligomeric forms are structurally equivalent.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that a functionally active form of H. pylori VacA can be reconstituted from two purified VacA fragments (p33 and p55). Previously, the p55 fragment was purified and its crystal structure determined (39), but it was not possible to purify a soluble, functionally-active form of p33. In the current study, we purified the p33 domain under denaturing conditions and then employed a series of steps designed to allow the protein to refold and remain soluble. We found that the refolded p33 protein was soluble in a buffer containing 800 mM guanidine and 250 mM arginine, but upon removal of these additives, the p33 protein became insoluble. Analysis of the p33 protein by circular dichroism was not feasible due to interference caused by the presence of arginine. Nevertheless, in comparison to denatured p33, the refolded p33 protein exhibited functional activity when mixed with the p55 fragment, which suggests that the p33 protein was successfully refolded.

Previous studies reported that a mixture of E. coli lysates containing VacA p33 and p55 can cause vacuolation of HeLa cells (32), and intracellular co-expression of p33 and p55 in HeLa cells results in cell vacuolation (38, 59). However, there are numerous limitations associated with the use of crude E. coli lysates or intracellular expression systems. By using purified p33 and p55 proteins in the current study, we were able to monitor the process by which p33 and p55 proteins interact to yield a functionally active VacA protein. Specifically, we demonstrate that the p33 and p55 proteins were purified with molecular masses of about 96 kDa and 178 kDa, respectively. The mass of the p33 protein is consistent with a trimeric form, but efforts to validate this by EM were unsuccessful. The mass of the p55 protein is consistent with a trimer as well, but the crystal structure of p55 revealed a head-to-head packed dimer that adopts an elongated dumbbell shape (39). The elongated shape and the unusual buffer conditions likely account for the high apparent molecular mass of p55 on the sizing column. Upon mixing of the p55 and p33 preparations, the p55 and p33 homo-oligomers each dissociated to yield a p33/p55 complex with a mass of about 86 kDa, corresponding to a complex containing one p55 subunit and one p33 subunit. These p33/p55 monomeric complexes were visible by EM as elongated rods (Fig. 6), similar to the appearance of p88 VacA monomers (43).

The ability to reconstitute a functional protein from two individually-expressed component domains is somewhat unusual among bacterial protein toxins, and unusual among proteins in general. This phenomenon is probably facilitated by distinctive structural features of VacA. The VacA p55 domain consists predominantly of a β-helix, composed of multiple ~25 amino acid repeats, each of which forms a 3 β-strand triangle-shaped coil (39). Adjacent coils are held together by backbone hydrogen bonds. The β-helix is therefore very different from globular proteins where adjacent structural elements are held together with an intricate arrangement of sidechain interactions. Based on computer modeling, the VacA p33 domain is also predicted to comprise a β-helical structure, and it is predicted that the p88 protein comprises an elongated continuous β-helical structure (39). In the current experiments, we speculate that the C-terminal coil of p33 interacts with the N-terminal coil of p55, recapitulating the structural relationship that exists between these two domains in the intact p88 VacA protein (39).

A distinctive property of the p88 VacA protein secreted by H. pylori is its ability to assemble into water-soluble, flower-shaped oligomeric structures (42–45). In contrast, we observed that purified p33 and p55 proteins interact to form ~86 kDa complexes, but do not readily assemble into oligomeric structures when maintained in buffer alone. One possible explanation is that the guanidine and arginine constituents of the buffer (required for maintenance of p33 solubility) prevent VacA oligomerization; however, we observed that these agents did not cause disassembly of p88 oligomers purified from H. pylori culture supernatant. We hypothesized that H. pylori broth culture supernatant might contain factors (either components of the rich Brucella broth medium used for culture of H. pylori, or additional H. pylori products) that allow VacA oligomers to form. We observed that, indeed, the addition of freshly prepared Brucella broth (not previously cultured with H. pylori) to purified p33/p55 mixtures promoted assembly of VacA into oligomeric structures. Similarly, the addition of detergent also stimulated oligomerization. We speculate that oligomerization is stimulated by exposure to an amphipathic environment, and that the oligomerization observed in these experiments mimics the process by which VacA oligomerizes when in contact with membranes of host cells.

The p88 VacA protein is typically purified in an oligomeric form from H. pylori broth culture supernatant (8, 42–45), and monomeric forms of p88 VacA have been relatively difficult to purify. When added to cultured eukaryotic cells, purified p88 VacA oligomers lack detectable activity in most assays unless the oligomers are first exposed to low pH or high pH conditions, which results in oligomer disassembly; oligomers have been observed to reassemble if the pH is returned to neutral (16, 24, 42, 51, 60–62). A current model presumes that VacA monomers interact with the cell surface, and then reassemble into oligomeric complexes that function as membrane channels. In the current study, we demonstrate that a mixture of purified p33 and p55 proteins is fully active in cell culture assays in the absence of low pH or high pH activation. Since the p33/p55 mixture predominantly consists of a p88 complex (Figures 5 and 6), this provides additional support for a model in which VacA monomers interact with the plasma membrane.

Several lines of evidence indicate that oligomerization of p88 VacA is required for VacA-induced cellular alterations (33, 47–48, 50). VacA oligomeric structures have been visualized on the surface of VacA-treated cells or lipid bilayers (24, 44, 46), and in contrast to double-layered oligomeric forms of VacA found in H. pylori culture supernatant, there is evidence that the VacA oligomeric complexes formed on the surface of cells are single-layered (24). Potentially, oligomerization of VacA occurs preferentially within lipid raft components of the plasma membrane (46, 63–64). In the current study, we observed that detergent promoted assembly of p33/p55 mixtures into predominantly single-layered oligomeric structures. Therefore, the complexes visualized in the current study are predicted to be useful models for VacA channels that form in the context of human cells.

The reconstitution of VacA activity from purified p33 and p55 components probably involves a complex series of molecular events. An initial step involves disassembly of p33 and p55 homo-oligomers and formation of a p33–p55 complex. Potentially the presence of p55 disrupts p33-p33 interactions, or the presence of p33 may disrupt p55-p55 interactions. An important observation is that neither p33 nor p55 bound to cells when added individually, whereas the p33/p55 mixture exhibited strong binding to cells (Figure 4). One possible explanation is that the homo-oligomeric forms of p33 and p55 lack cell-binding activity, and cell-binding surfaces become exposed upon disassembly of the homo-oligomeric complexes. Alternatively, the receptor-binding site(s) may span both the p33 and p55 domains. Finally, the assembly of p33/p55 complexes into higher-order flower-shaped oligomers may stabilize the interaction of VacA with the surface of eukaryotic cells, and oligomer formation is predicted to be required for insertion of VacA into membranes and channel formation.

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Williams and B. Hosse for EM and microbiology technical support, respectively. We thank J.D. King and J. F. Hillyer for advice on microscopic techniques. Cell imaging experiments were performed through the use of the VUMC Cell Imaging Shared Resource (supported by NIH grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, HD15052, DK59637, and Ey008126).

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (R01AI39657), Department of Veterans Affairs, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Molecular Microbial Pathogenesis Training Program (T32 AI007281-21), Molecular Biophysics Training Program (T32 GM08320) and Vanderbilt Development funds.

Abbreviations

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cells

- TB-KAN

Terrific broth containing kanamycin

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- EM

electron microscopy

- DDM

n-dodecyl beta-D-maltoside

- mrc

mixed raster content

REFERENCES

- 1.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:720–741. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1863–1873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: ancient history, modern implications. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2475–2487. doi: 10.1172/JCI38605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amieva MR, El-Omar EM. Host-bacterial interactions in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:306–323. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atherton JC. The pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastro-duodenal diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:63–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leunk RD, Johnson PT, David BC, Kraft WG, Morgan DR. Cytotoxic activity in broth-culture filtrates of Campylobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 1988;26:93–99. doi: 10.1099/00222615-26-2-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Purification and characterization of the vacuolating toxin from Helicobacter pylori. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10570–10575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cover TL, Blanke SR. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:320–332. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Bernard M, Cappon A, Del Giudice G, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C. The multiple cellular activities of the VacA cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;293:589–597. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer W, Prassl S, Haas R. Virulence mechanisms and persistence strategies of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;337:129–171. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-01846-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujikawa A, Shirasaka D, Yamamoto S, Ota H, Yahiro K, Fukada M, Shintani T, Wada A, Aoyama N, Hirayama T, Fukamachi H, Noda M. Mice deficient in protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z are resistant to gastric ulcer induction by VacA of Helicobacter pylori. Nat Genet. 2003;33:375–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Telford JL, Ghiara P, Dell'Orco M, Comanducci M, Burroni D, Bugnoli M, Tecce MF, Censini S, Covacci A, Xiang Z, et al. Gene structure of the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin and evidence of its key role in gastric disease. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1653–1658. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atherton JC, Cao P, Peek RM, Jr, Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ, Cover TL. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17771–17777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueiredo C, Machado JC, Pharoah P, Seruca R, Sousa S, Carvalho R, Capelinha AF, Quint W, Caldas C, van Doorn LJ, Carneiro F, Sobrinho-Simoes M. Helicobacter pylori and interleukin 1 genotyping: an opportunity to identify high-risk individuals for gastric carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1680–1687. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.22.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szabo I, Brutsche S, Tombola F, Moschioni M, Satin B, Telford JL, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C, Papini E, Zoratti M. Formation of anion-selective channels in the cell plasma membrane by the toxin VacA of Helicobacter pylori is required for its biological activity. EMBO J. 1999;18:5517–5527. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galmiche A, Rassow J, Doye A, Cagnol S, Chambard JC, Contamin S, de Thillot V, Just I, Ricci V, Solcia E, Van Obberghen E, Boquet P. The N-terminal 34 kDa fragment of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin targets mitochondria and induces cytochrome c release. EMBO J. 2000;19:6361–6370. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willhite DC, Blanke SR. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin enters cells, localizes to the mitochondria, and induces mitochondrial membrane permeability changes correlated to toxin channel activity. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:143–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayama M, Kimura M, Wada A, Yahiro K, Ogushi K, Niidome T, Fujikawa A, Shirasaka D, Aoyama N, Kurazono H, Noda M, Moss J, Hirayama T. Helicobacter pylori VacA activates the p38/activating transcription factor 2-mediated signal pathway in AZ-521 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7024–7028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terebiznik MR, Raju D, Vazquez CL, Torbricki K, Kulkarni R, Blanke SR, Yoshimori T, Colombo MI, Jones NL. Effect of Helicobacter pylori's vacuolating cytotoxin on the autophagy pathway in gastric epithelial cells. Autophagy. 2009;5:370–379. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gebert B, Fischer W, Weiss E, Hoffmann R, Haas R. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin inhibits T lymphocyte activation. Science. 2003;301:1099–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1086871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundrud MS, Torres VJ, Unutmaz D, Cover TL. Inhibition of primary human T cell proliferation by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) is independent of VacA effects on IL-2 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7727–7732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401528101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sewald X, Gebert-Vogl B, Prassl S, Barwig I, Weiss E, Fabbri M, Osicka R, Schiemann M, Busch DH, Semmrich M, Holzmann B, Sebo P, Haas R. Integrin subunit CD18 Is the T-lymphocyte receptor for the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czajkowsky DM, Iwamoto H, Cover TL, Shao Z. The vacuolating toxin from Helicobacter pylori forms hexameric pores in lipid bilayers at low pH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2001–2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tombola F, Carlesso C, Szabo I, de Bernard M, Reyrat JM, Telford JL, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C, Papini E, Zoratti M. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin forms anion-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers: possible implications for the mechanism of cellular vacuolation. Biophys J. 1999;76:1401–1409. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77301-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gauthier NC, Monzo P, Gonzalez T, Doye A, Oldani A, Gounon P, Ricci V, Cormont M, Boquet P. Early endosomes associated with dynamic F-actin structures are required for late trafficking of H. pylori VacA toxin. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:343–354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cover TL, Tummuru MK, Cao P, Thompson SA, Blaser MJ. Divergence of genetic sequences for the vacuolating cytotoxin among Helicobacter pylori strains. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10566–10573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt W, Haas R. Genetic analysis of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin: structural similarities with the IgA protease type of exported protein. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:307–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer W, Buhrdorf R, Gerland E, Haas R. Outer membrane targeting of passenger proteins by the vacuolating cytotoxin autotransporter of Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6769–6775. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6769-6775.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen VQ, Caprioli RM, Cover TL. Carboxy-terminal proteolytic processing of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. Infect Immun. 2001;69:543–546. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.543-546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres VJ, McClain MS, Cover TL. Interactions between p-33 and p-55 domains of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2324–2331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres VJ, Ivie SE, McClain MS, Cover TL. Functional properties of the p33 and p55 domains of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21107–21114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vinion-Dubiel AD, McClain MS, Czajkowsky DM, Iwamoto H, Ye D, Cao P, Schraw W, Szabo G, Blanke SR, Shao Z, Cover TL. A dominant negative mutant of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) inhibits VacA-induced cell vacuolation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37736–37742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClain MS, Iwamoto H, Cao P, Vinion-Dubiel AD, Li Y, Szabo G, Shao Z, Cover TL. Essential role of a GXXXG motif for membrane channel formation by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12101–12108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212595200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pagliaccia C, de Bernard M, Lupetti P, Ji X, Burroni D, Cover TL, Papini E, Rappuoli R, Telford JL, Reyrat JM. The m2 form of the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin has cell type-specific vacuolating activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10212–10217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reyrat JM, Lanzavecchia S, Lupetti P, de Bernard M, Pagliaccia C, Pelicic V, Charrel M, Ulivieri C, Norais N, Ji X, Cabiaux V, Papini E, Rappuoli R, Telford JL. 3D imaging of the 58 kDa cell binding subunit of the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:459–470. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang HJ, Wang WC. Expression and binding analysis of GST-VacA fusions reveals that the C-terminal approximately 100-residue segment of exotoxin is crucial for binding in HeLa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:449–454. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye D, Willhite DC, Blanke SR. Identification of the minimal intracellular vacuolating domain of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9277–9282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gangwer KA, Mushrush DJ, Stauff DL, Spiller B, McClain MS, Cover TL, Lacy DB. Crystal structure of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin p55 domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16293–16298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707447104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dautin N, Bernstein HD. Protein secretion in gram-negative bacteria via the autotransporter pathway. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:89–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Junker M, Schuster CC, McDonnell AV, Sorg KA, Finn MC, Berger B, Clark PL. Pertactin beta-helix folding mechanism suggests common themes for the secretion and folding of autotransporter proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4918–4923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507923103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cover TL, Hanson PI, Heuser JE. Acid-induced dissociation of VacA, the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin, reveals its pattern of assembly. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:759–769. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Bez C, Adrian M, Dubochet J, Cover TL. High resolution structural analysis of Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin oligomers by cryo-negative staining electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2005;151:215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adrian M, Cover TL, Dubochet J, Heuser JE. Multiple oligomeric states of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin demonstrated by cryo-electron microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:121–133. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lupetti P, Heuser JE, Manetti R, Massari P, Lanzavecchia S, Bellon PL, Dallai R, Rappuoli R, Telford JL. Oligomeric and subunit structure of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:801–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geisse NA, Cover TL, Henderson RM, Edwardson JM. Targeting of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin to lipid raft membrane domains analysed by atomic force microscopy. Biochem J. 2004;381:911–917. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ivie SE, McClain MS, Torres VJ, Algood HM, Lacy DB, Yang R, Blanke SR, Cover TL. Helicobacter pylori VacA subdomain required for intracellular toxin activity and assembly of functional oligomeric complexes. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2843–2851. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01664-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Genisset C, Galeotti CL, Lupetti P, Mercati D, Skibinski DA, Barone S, Battistutta R, de Bernard M, Telford JL. A Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin mutant that fails to oligomerize has a dominant negative phenotype. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1786–1794. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1786-1794.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torres VJ, McClain MS, Cover TL. Mapping of a domain required for protein-protein interactions and inhibitory activity of a Helicobacter pylori dominant-negative VacA mutant protein. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2093–2101. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2093-2101.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McClain MS, Cao P, Iwamoto H, Vinion-Dubiel AD, Szabo G, Shao Z, Cover TL. A 12-amino-acid segment, present in type s2 but not type s1 Helicobacter pylori VacA proteins, abolishes cytotoxin activity and alters membrane channel formation. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6499–6508. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6499-6508.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Bernard M, Papini E, de Filippis V, Gottardi E, Telford J, Manetti R, Fontana A, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C. Low pH activates the vacuolating toxin of Helicobacter pylori, which becomes acid and pepsin resistant. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23937–23940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Middelberg AP. Preparative protein refolding. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)02047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cover TL, Puryear W, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Effect of urease on HeLa cell vacuolation induced by Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1264–1270. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1264-1270.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Algood HM, Torres VJ, Unutmaz D, Cover TL. Resistance of primary murine CD4+ T cells to Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:334–341. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01063-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohi M, Li Y, Cheng Y, Walz T. Negative Staining and Image Classification - Powerful Tools in Modern Electron Microscopy. Biol Proced Online. 2004;6:23–34. doi: 10.1251/bpo70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hawrylik SJ, Wasilko DJ, Haskell SL, Gootz TD, Lee SE. Bisulfite or sulfite inhibits growth of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:790–792. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.790-792.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frank J, Radermacher M, Penczek P, Zhu J, Li Y, Ladjadj M, Leith A. SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:190–199. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ye D, Blanke SR. Functional complementation reveals the importance of intermolecular monomer interactions for Helicobacter pylori VacA vacuolating activity. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1243–1253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tombola F, Oregna F, Brutsche S, Szabo I, Del Giudice G, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C, Papini E, Zoratti M. Inhibition of the vacuolating and anion channel activities of the VacA toxin of Helicobacter pylori. FEBS Lett. 1999;460:221–225. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molinari M, Galli C, de Bernard M, Norais N, Ruysschaert JM, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C. The acid activation of Helicobacter pylori toxin VacA: structural and membrane binding studies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:334–340. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yahiro K, Niidome T, Kimura M, Hatakeyama T, Aoyagi H, Kurazono H, Imagawa K, Wada A, Moss J, Hirayama T. Activation of Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin by alkaline or acid conditions increases its binding to a 250-kDa receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase beta. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36693–36699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schraw W, Li Y, McClain MS, van der Goot FG, Cover TL. Association of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) with lipid rafts. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34642–34650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel HK, Willhite DC, Patel RM, Ye D, Williams CL, Torres EM, Marty KB, MacDonald RA, Blanke SR. Plasma membrane cholesterol modulates cellular vacuolation induced by the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4112–4123. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4112-4123.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]