Abstract

Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA increases with aging. This damage has the potential to affect mitochondrial DNA replication and transcription which could alter the abundance or functionality of mitochondrial proteins. This review describes mitochondrial DNA alterations and changes in mitochondrial function that occur with aging. Age-related alterations in mitochondrial DNA as a possible contributor to the reduction in mitochondrial function are discussed.

Keywords: Aging, mitochondria, mitochondrial DNA

1. Introduction

Mitochondria are unique organelles because they contain their own DNA. Multiple copies of the mitochondrial genome are present in each mitochondrion. The mammalian mitochondrial genome is composed of ∼16.5 kilobases of circular, double-stranded DNA encoding for 2 ribosomal RNAs, 22 transfer RNAs, and 13 protein subunits of the electron transport chain (Anderson et al., 1981; Bibb et al., 1981), all of which are essential for proper mitochondrial function. The majority of mitochondrial proteins are encoded by the nuclear genome and transported to mitochondria. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is organized into protein-DNA complexes called nucleoids within the mitochondrial matrix (Gilkerson, 2009). Although mtDNA is packaged into nucleoids, which provide more protection to the genome than was originally thought, it remains in close proximity to the electron transport chain (located in the inner mitochondrial membrane) which is the main source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the cell.

Mitochondria generate chemical energy (ATP), which is required to fuel many thermodynamically unfavorable processes within cells (e.g., ion transport against electrochemical gradients, protein synthesis, ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation, and contractility). Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation generates ATP through a set of coupled reactions where macronutrients are oxidized, oxygen is reduced to water, and ADP is phosphorylated to ATP. First, carbon substrates enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle either through acetyl CoA or anaplerotic reactions. These substrates are then oxidized to generate reducing equivalents in the form of NADH and FADH2, which provide electron flow though respiratory chain complexes I (NADH dehydrogenase) and II (succinate dehydrogenase), respectively. Electron flow from complexes I and II converges on complex III (ubiquinone-cytochrome c reductase), along with electrons shuttled in from electron transferring flavoproteins (beta oxidation), through the mobile electron carrier coenzyme Q. A second mobile electron carrier (cytochrome c) transfers electrons on to complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) where they are finally transferred to oxygen, yielding water. A proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane is generated as a result of electron transport through complexes I, III, and IV. Complex V (ATP synthase) phosphorylates ADP to ATP by harnessing the potential energy of this gradient.

During the process of ATP production by oxidative phosphorylation, ROS are also generated at complex I and complex III. Electron leak at these complexes can reduce oxygen to form the superoxide radical, ·O2-. ROS are highly reactive molecules that can damage nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins. Because of the close proximity of mtDNA to the electron transport chain it is thought that mtDNA is highly susceptible to oxidative damage by ROS. The mitochondrial theory of aging proposes that ROS-induced oxidative damage to mitochondria and its DNA is a major contributor to aging (Harman, 1972; Linnane et al., 1989). Key to this theory is the idea that a vicious cycle of mitochondrial damage resulting in dysfunction drives the aging process. Briefly, ROS generated during oxidative phosphorylation may damage mtDNA, lipids, and proteins. Mutations that may occur within the mtDNA as a result of unrepaired oxidative damage may lead to the production of dysfunctional proteins. Dysfunctional electron transport chain proteins may produce more ROS which would continue the damaging cycle.

Accumulating evidence suggests that the ROS production rate is largely dependent on the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) (Balaban et al., 2005). Mitochondrial redox potential is high when membrane potential is high, allowing for greater potential for backflow of electrons through complexes I and III. In contrast, state 3 respiration minimizes this effect by increasing the forward flux of electrons along the cytochromes. The mitochondrial membrane potential is also influenced by uncoupling proteins that are expressed in tissues such as adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. The uncoupling of mitochondrial oxygen consumption from ATP production by uncoupling proteins (UCP-1) is an important mechanism of thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue in animals. Mitochondrial uncoupling and thermogenesis also occur in skeletal muscle, which, by virtue of its mass, plays a key role in regulating energy expenditure and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Proteins with similar structural homology to UCP-1 are expressed in skeletal muscle (UCP-2,3) (Boss et al., 1997; Fleury et al., 1997). Although the role of UCP-3 as an uncoupler is questionable (Cadenas et al., 1999; Dulloo et al., 2001), this protein has been determined to be important in fatty acid (FA) metabolism by shuttling FA anions out of the mitochondrial matrix. FAs may participate in “flip-flop acidification” whereby neutral FAs, but not FA anions, can rapidly flip-flop across the inner mitochondrial membrane. An acid-base equilibrium is then achieved via protonation of FA anions on the cytosolic side of the membrane and deprotonation of neutral FAs on the matrix side of the membrane. This “flip-flop acidification” would lead to dissipation of the mitochondrial proton gradient and uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation (Jezek and Garlid, 1998). FA anion carriers such as UCP-3 transport these deprotonated FAs back to the cytosolic side of the membrane. By exporting FA anions from the mitochondrial matrix, UCP-3s are believed to minimize peroxidation of lipids that would occur in close proximity to the superoxide-generating electron transport chain. Furthermore, although UCP-3s are not believed to act as proton channels such as UCP-1, they are key components in the process of FA cycling, which dissipates a portion of the proton gradient (Jezek and Garlid, 1998).

Mitochondrial structure is maintained by the balanced processes of fusion and fission. Mitochondrial fission, mediated by mitofusins, is believed to be an initial step in maintaining the functionality of the mitochondrial reticulum through separation and subsequent autophagy of dysfunctional regions of the organelle (Legros et al., 2002; Chan, 2006). During mitochondrial fusion, the contents of the mitochondrial matrix are exchanged between organelles. This process is regulated by dynamin-related protein Drp1 and the mitochondrial fission protein hFis1 (Lopez-Lluch et al., 2008). While some believe that fusion causes mutated mtDNA to diffuse between organelles and become evenly distributed about the cell, there is evidence to suggest that mitochondrial nucleoids are bound to regions of the inner membrane, which restricts their diffusion (Miyakawa et al., 1987). Nevertheless, it is possible that defects in fusion and fission could contribute to declines in mitochondrial function with old age because mtDNA deletions and mutations may not be effectively diluted by fusion or eliminated by fission and autophagy. The role of mitochondrial remodeling in aging has recently been demonstrated by depletion of hFis by RNA interference, which induces a senescent phenotype (Lee et al., 2007). Furthermore, the activity of Lon protease, which degrades oxidized mitochondrial proteins, decreases with age (Lee et al., 1999). The resulting accumulation of oxidized, dysfunctional proteins could further increase oxidative stress and oxidative damage to proteins and DNA with aging.

2. Mitochondrial DNA Alterations in Aging

Oxidative damage

Consequences of oxidative damage to mtDNA include point mutations, deletions, and strand breaks. Exposure to ROS can result in a number of oxidative modifications to mtDNA including the lesions 8-oxoguanine, 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (FapyG), 4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine (FapyA), and thymine glycol. The most commonly studied of these oxidative lesions is 8-oxoguanine. 8-oxoguanine can be removed from mtDNA through the process of base excision repair by the mitochondrial targeted splice variant of oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) (de Souza-Pinto et al., 2001). If 8-oxoguanine is not removed, an A can be inserted opposite of 8-oxoguanine during replication. This can result in a G:C → T:A transversion at the site of the adduct (Krokan et al., 1997; Wallace, 2002). The MutY homolog protein can remove the mispaired A opposite 8-oxoguanine; however, this results in an abasic site which is susceptible to strand breaks. Strand breaks, if not repaired, can lead to DNA degradation (Oka et al., 2008; Shokolenko et al., 2009) as well as deletions (Srivastava and Moraes, 2005). While 8-oxoguanine is the most commonly studied oxidative lesion, the formamidopyrimidine lesions occur at similar (FapyA) or even greater (FapyG) levels (Jaruga et al., 2000; Hu et al., 2005). The formamidopyrimidine lesions FapyA and FapyG share a common intermediate with 8-oxoadenine and 8-oxoguanine respectively (Candeias and Steenken, 2000; Krishnamurthy et al., 2008). FapyA and FapyG, like 8-oxoguanine, can lead to the misincorporation of adenine across from the site of the lesion (Delaney et al., 2002; Wiederholt and Greenberg, 2002). Thymine glycol lesions block DNA replication and transcription (Ide et al., 1985; Clark and Beardsley, 1987; Hatahet et al., 1994). Most FapyG lesions are repaired by OGG1 while FapyA and thymine glycol lesions are repaired by NTH1 (Karahalil et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2005). Any of these lesions might play a role in aging, either through mutagenicity or disruption of normal replication and transcription of mtDNA, which emphasizes the importance of effective base excision repair mechanisms in mitochondria.

An age-related increase in oxidative damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNA has been reported by a number of investigators (Hamilton et al., 2001b; Van Remmen et al., 2003; Short et al., 2005a). The reported values of DNA oxidative damage were likely overestimated in early studies because the methods used to isolate DNA caused additional oxidative damage. Even though the values were high, the conclusions drawn from those studies regarding the effects of age on DNA damage should remain valid since all samples would have undergone the same methods of extraction and therefore should have incurred the same amount of artifactual oxidation (Anson et al., 2000). More recent studies using better methods for DNA isolation have shown an increase in mtDNA 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG) content with aging (Hamilton et al., 2001b). In this study mtDNA was obtained using the sodium iodide isolation method, which has been shown to eliminate 8-oxo-dG generation during DNA isolation (Hamilton et al., 2001a). mtDNA isolated from liver had 50-124% higher levels of 8-oxo-dG in aged mice and rats (Hamilton et al., 2001b). The age-related increase in mtDNA oxidative damage may be due to an increased sensitivity to oxidative damage during aging as has been shown for nuclear DNA, (Hamilton et al., 2001b) or an increased rate of formation, but is not likely due to a loss of mitochondrial DNA repair capacity (Stevnsner et al., 2002).

Point mutations and deletions

Perhaps due to the increase in mtDNA oxidative damage, an accumulation of point mutations and deletions also occur within the mitochondrial genome with aging, although it is still unclear whether these alterations are a cause or consequence of the aging process. Either the loss of gene products (deletions) or improper encoding of gene products (point mutations) could be expected to lead to impaired respiratory chain complex formation and eventual functional decline.

The mitochondrial genome contains a non-coding control region called the displacement loop (D-loop) which is important for mtDNA replication and transcription. This region has been extensively studied for the presence of age-related point mutations. Previous studies have found an accumulation of point mutations including A189G, T408A, and T414G in this control region with aging (Michikawa et al., 1999; Calloway et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2001; Del Bo et al., 2002; Del Bo et al., 2003; Theves et al., 2006; McInerny et al., 2009). One study investigated mutations in mtDNA isolated from fibroblasts of 9 individuals twice over a 9-19 year period (Michikawa et al., 1999). Every individual had accumulated at least one point mutation within the mtDNA control region at the later age. Another study investigated the accumulation of the A189G mutation in individuals from 10 maternal lineages (Theves et al., 2006). The A189G mutation was absent in buccal cells of young individuals but present in older individuals from the same family indicating that this is a somatic mutation that accumulates with aging as opposed to an inherited mutation. The A189G mutation was also investigated in muscle of unrelated individuals ages 1-97 (Theves et al., 2006). As in buccal cells, a higher percentage of mutations exist in older individuals. The accumulation of mutations is higher in skeletal muscle than buccal cells of older individuals. This tissue-specific accumulation of point mutations, which has also been shown by other investigators (Liu et al., 1998; McInerny et al., 2009), may be related to the metabolic characteristics of the tissue. The age-related accumulation of mutations within this regulatory region of the mitochondrial genome may influence its activity. In fact, recent studies in young (4-6 months) and old (23-29 months) rats have shown an age-related loss of 7S DNA (a product of D-loop activity) in striatum, cortex, and spinal cord (McInerny et al., 2009).

Until recently mtDNA deletions were thought to occur during replication. Krishnan et al. have proposed that mtDNA deletions are most likely occurring during the repair of damaged mtDNA rather than during replication (Krishnan et al., 2008). Among other evidence against mtDNA deletions occurring during replication is the idea that mitotic cells, which have a higher frequency of mtDNA replication that postmitotic cells, should contain more deletions, yet no mtDNA containing deletions have been found in human colonic tissue (Taylor et al., 2003; Krishnan et al., 2008). The proposed mechanism by which mtDNA deletions arise during mtDNA repair is through exonuclease activity at double-strand breaks (Krishnan et al., 2008). It is possible that the age-related accumulation of ROS-induced damage could result in double-strand breaks through direct DNA damage or increased replication stalling thereby leading to an increase in mtDNA deletions in older age (Krishnan et al., 2008).

An age-related accumulation of various deletions have been shown in multiple tissues of different species (Corral-Debrinski et al., 1992; Cortopassi et al., 1992; Melov et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998; Meissner et al., 2008). An early study investigated the presence of deletions in skeletal muscle from young and old individuals. Young individuals had predominantly full length mtDNA. Little to no full length mtDNA was observed in old individuals, but no single rearrangement was common to all of them (Melov et al., 1995). While a number of deletions can occur, the most commonly studied in humans is a 4977 bp deletion that removes all or parts of the genes for NADH dehydrogenase subunits 3, 4, 4L, and 5, cytochrome c oxidase subunit III, and ATP synthase subunits 6 and 8 (MITOMAP, 2009). Meissner et al. performed an extensive study using a quantitative PCR approach to investigate the abundance of the 4977 bp deletion in 9 regions of brain, heart, and skeletal muscle of 92 individuals aged 2 months to 102 years (Meissner et al., 2008). The abundance of the 4977 bp deletion increased in all tissues with aging, although the levels were highly variable between individuals of the same decade and among different tissues within a single individual (Meissner et al., 2008). The high variability of deletions among different tissues and even among different regions of a tissue has also been observed in other studies (Corral-Debrinski et al., 1992; Cortopassi et al., 1992; Zhang et al., 1997). Of particular interest in the study by Meissner et al. was the detection of the 4977 bp deletion in the brain of 10 and 12 year old individuals (Meissner et al., 2008). This observation is in agreement with others who have suggested that large-scale deletions are the result of a single random mutation in early childhood or adolescence that is clonally expanded over the lifetime (Khrapko et al., 2003). This could explain the variability of mutant fractions in tissue homogenates since, by chance, one sample may include a cluster of mutants while another sample may not (Khrapko et al., 2003).

In light of this, recent studies have investigated point mutations and deletions in single cells instead of tissue homogenates (Bodyak et al., 2001; Nekhaeva et al., 2002; Del Bo et al., 2003; Gokey et al., 2004; Herbst et al., 2007). Typically, different cells contain different mutations, but only one particular point mutation or deletion is found in a single cell and the percent of mutant DNA molecules within a cell increases with age (Bodyak et al., 2001; Nekhaeva et al., 2002). Skeletal muscle develops a mosaic pattern of increasing cytochrome c oxidase (COX) deficient muscle fibers with increasing age. Because this phenotype may be indicative of mtDNA alterations these cells have been a target of investigation. A comparison of D-loop point mutations in COX positive, COX negative, and COX negative ragged red fibers in 4 aged individuals showed no correlation between the percentage of mutated molecules and the histochemical phenotype; however, the cumulative burden of multiple mtDNA alterations (point mutations, length variations, deletions) correlates with the COX phenotype (Del Bo et al., 2003). A study of deletions in COX negative muscle fibers from aged rats showed that >90% of the mtDNA at the site of the electron transport system abnormality (COX-/SDH++) contained deletion mutations (Herbst et al., 2007). That a single mutation increases with age and high levels correlate with cell dysfunction indicates that clonally expanded mtDNA mutations may play a role in the functional decline that occurs with aging.

In summary, the overall level of mutations and deletions detected in tissue homogenates seems too low (typically <1% of total mtDNA) to result in any whole tissue functional consequences. Two explanations have been proposed to address this issue. First, it seems unlikely for low levels of single mutations to influence functional decline in aging, but an accumulation of a number of mutations may (Zhang et al., 1998). For example, an accumulation of mutations within a region that controls both replication and transcription (D-loop) could lead to a decline in function through reduced mtDNA copy number and/or reduced mitochondrial transcripts. Second, the overall levels of mutations in tissue homogenates are relatively low, but the mutational load is high in single cells containing a clonal expansion (Zhang et al., 1998). A high mutational load within a single cell due to clonal expansion could likely reduce mitochondrial function and even signal for cell loss through apoptosis which has the potential to impact whole tissue function if enough cells are affected.

Mitochondrial DNA mutator mice

mtDNA mutator mice have been used to investigate the role of mtDNA mutations in aging, although it is still unclear whether a causative role exists for mitochondrial DNA mutations and/or deletions in human aging. mtDNA mutator mice express a proofreading deficient mitochondrial polymerase γ (Trifunovic et al., 2004; Kujoth et al., 2005). These mice maintain normal DNA polymerase activity, but display reduced exonuclease activity which results in an accumulation of mtDNA point mutations and deletions. The increased mutational load in these mice is associated with a reduced lifespan and an accelerated aging phenotype characterized by weight loss, reduced subcutaneous fat, alopecia, graying, kyphosis, osteoporosis, anemia, reduced fertility, heart enlargement, thymic involution, testicular atrophy, loss of intestinal crypts, hearing loss, and skeletal muscle mass loss (Trifunovic et al., 2004; Kujoth et al., 2005). Tissue dysfunction associated with the accumulation of mtDNA mutations was proposed to be the result of a loss of critical irreplaceable cells by apoptosis demonstrated by enhanced caspase-3 activation (Kujoth et al., 2005).

A major point of contention concerns the role of point mutations versus deletions in the accelerated aging of mtDNA mutator mice. Initial studies provided a correlation between increased mtDNA mutations and aging (Trifunovic et al., 2004; Kujoth et al., 2005). Subsequent work suggested that it was the presence of increased mtDNA deletions that limit the lifespan of mtDNA mutator mice, not point mutations (Vermulst et al., 2007; Vermulst et al., 2008). mtDNA deletions accumulate at an accelerated rate in brains of homozygous mutator mice compared to both heterozygote mutator mice and wild-type mice; (Vermulst et al., 2008) however, heterozygote mutator mice have high levels of point mutations (500-fold higher than wild-type mice) but do not display any features of premature aging like the homozygous mutator mice (Vermulst et al., 2007). Thus, it was concluded that deletions were responsible for the premature aging of mtDNA mutator mice. In contrast, the absolute level of mitochondrial DNA deletions were demonstrated to be very low in the mtDNA mutator mice, especially when compared to the level of point mutations (Kraytsberg et al., 2009). Moreover, the deletor mouse, which expresses a defective helicase (Twinkle) that is involved in mtDNA replication and repair, has increased levels of deletions with a normal lifespan (Tyynismaa et al., 2005). More recent studies have further investigated alterations in the mtDNA of mutator mice that may be responsible for their functional decline. Recently it has been shown that linear deleted mtDNAs present in mtDNA mutator mice are replication intermediates caused by replication pausing and breakage at fragile sites indicating that the replication cycle in mtDNA mutator mice is altered (Bailey et al., 2009). Another recent study suggested that amino acid substitutions in mtDNA-encoded respiratory chain subunits cause instability in respiratory chain complexes which is responsible for the respiratory chain deficiency in mtDNA mutator mice (Edgar et al., 2009). Overall, there is evidence to suggest that both point mutations and deletions may contribute to the functional decline and premature aging of mtDNA mutator mice.

3. Mitochondrial DNA Abundance in Aging

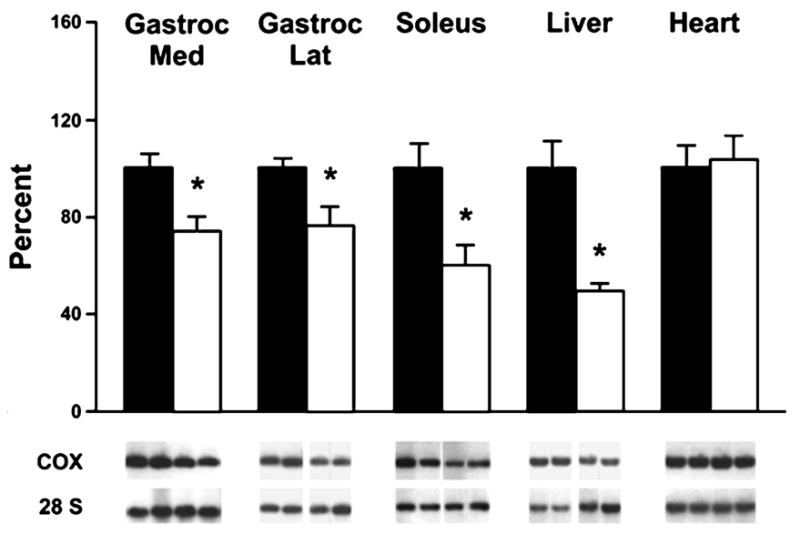

A decline in mtDNA abundance could contribute to the age-related decline in mitochondrial function. Reduced mtDNA template availability could negatively impact the levels of mitochondrial gene transcripts resulting in reduced levels of mitochondrial proteins. An age-related decline in mtDNA abundance has been demonstrated by some investigators. Barazzoni et al. found that mtDNA copy number was reduced by 25% in gastrocnemius, 40% in soleus, and 50% in liver of old rats (27 months) compared to young rats (6 months). Interestingly, mtDNA copy number did not change with age in heart (Figure 1) (Barazzoni et al., 2000). Subsequent studies confirmed this observation in human skeletal muscle. One study using discrete groups of younger and older individuals showed that mtDNA abundance was reduced by 38% in vastus lateralis of old individuals (65-75 years) compared to young individuals (21-27 years) (Welle et al., 2003). Another study using individuals across a large age span (19-89 years) demonstrated a decline in mtDNA abundance with aging in vastus lateralis (Figure 2a) (Short et al., 2005a). Other groups, however, have found that mtDNA copy number does not change with aging in human brain, skeletal muscle, or heart (Miller et al., 2003; Frahm et al., 2005). Another study also showed no age-related change in mtDNA copy number in mouse bone marrow or brain; however, the mtDNA content of heart, lung, kidney, spleen, and skeletal muscle increased with age (Masuyama et al., 2005). Differences in methods for quantifying mtDNA abundance may have contributed to some of the reported discrepancies in mtDNA abundance, though most of the variation is likely due to tissue-specific differences. For example, in the study by Barazzoni et al. the lack of age-related change in mtDNA abundance in the heart is likely due to the continuous contractile activity of the heart (Barazzoni et al., 2000), unlike skeletal muscle which undergoes age-related disuse. In fact, studies have shown that aerobic exercise can enhance muscle mtDNA abundance (Lanza et al., 2008). PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor [PPAR]-γ coactivator 1α) activates TFAM (mitochondrial transcription factor A), a protein that is known to be involved in mtDNA replication (Larsson et al., 1998). Aerobically trained mice have increased expression of PGC-1α protein and TFAM mRNA in conjunction with enhanced mtDNA abundance (Chow et al., 2007). Aerobic training in humans also enhances protein levels of PGC-1α and TFAM and can partly normalize the age-related decline in mtDNA abundance (Lanza et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Effects of aging on mitochondrial DNA content in gastrocnemius medial, gastrocnemius lateral, soleus, liver, and heart tissues of rats. Bars represent average ± S.E. of values from seven young (6 months) and nine old (27 months) animals. Under each bar are shown representative bands from Southern blots from two animals of each age group. Top bands show signals from the mtDNA fragment (3.0 kilobases), and bottom bands show signals from the nuclear DNA fragment containing the 28 S rRNA gene (6.4 kilobases). *, statistically different results (p < 0.03 or less) using Student's t test for unpaired data comparing young and old rats. This research was originally published in The Journal of Biological Chemistry. Barazzoni, R., Short, K. R. and Nair, K. S. Effects of aging on mitochondrial DNA copy number and cytochrome c oxidase gene expression in rat skeletal muscle, liver, and heart. J Biol Chem. 2000; 275:3343-7. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

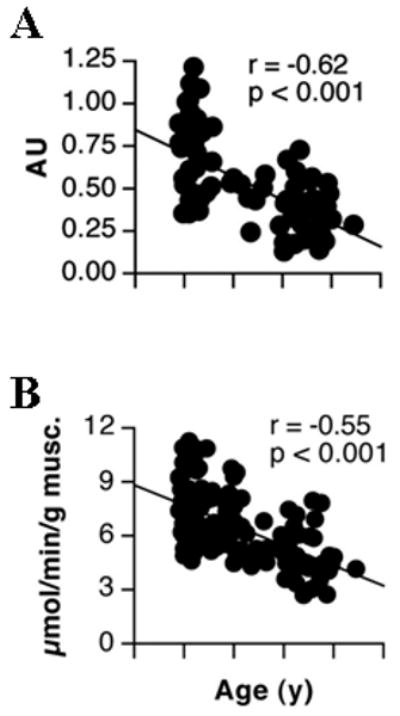

Figure 2.

Decline in muscle mtDNA abundance and mitochondrial ATP production rate with age. (A) mtDNA abundance was measured using a quantitative real-time PCR approach with a probe to the NADH Dehydrogenase 1 gene and is expressed in arbitrary units (AU). (B) Mitochondrial ATP production rate is shown using glutamate plus malate as a substrate. Taken with permission from Short et al., 2005a.

The abundance of mitochondrial DNA can be regulated by rates of mtDNA replication, which can be stimulated by exercise as described above, and by rates of mtDNA degradation. The decline in mtDNA copy number that occurs with aging might be a result of damaged mtDNA being degraded. Earlier studies showed that both mitochondrial DNA and RNA undergo degradation following hydrogen peroxide treatment of fibroblasts (Crawford et al., 1998). More recently it was demonstrated that hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative damage to mtDNA causes strand breaks that result in the degradation of linear mtDNA molecules (Shokolenko et al., 2009). The enzyme Endonuclease G is a candidate for playing a role in the degradation of oxidatively damaged mtDNA (Low, 2003). The specific activity of Endonuclease G has been correlated to the rate of oxygen consumption of a tissue and, by extension, the amount of oxidative damage to mtDNA (Houmiel et al., 1991; Low, 2003). Indeed, the rate of superoxide production is generally regarded as being equivalent to about 3 percent of total oxygen reduced by cytochrome c oxidase, making it plausible that tissue oxygen consumption and oxidative damage are in direct proportion. However, many mitochondrial physiologists favor the notion that ROS production rate is largely dependent on the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ) and less on the absolute rates of oxygen consumption (Balaban et al., 2005). ROS production has been shown to be higher under conditions where membrane potential is high (e.g. state 2 or state 4 respiration) where the high redox potential would perhaps promote backflow of electrons through complexes I and III, both of which are considered to be major sites for superoxide generation. In contrast, when membrane potential is lower (i.e., state 3) this effect would be minimized by increasing the forward flux of electrons along the cytochromes, providing less opportunity for generation of superoxide. Treatment of DNA with the oxidants L-ascorbic acid or peplomycin, both of which introduce DNA strand breaks, has been shown to enhance susceptibility of DNA to nucleolytic attack by Endonuclease G (Ikeda and Ozaki, 1997). Altogether these data indicate that there is a mechanism in place within mitochondria that can prevent the accumulation of oxidatively damaged DNA by eliminating defective genomes. The elimination of damaged mtDNA would lead to lower copy numbers only if mtDNA levels are not replenished through replication. Reduced replication of mtDNA is not explained by an age-related reduction in the transcript levels of several genes involved in mtDNA replication (TFAM, NRF-1, DNA polymerase γ, single-stranded DNA binding protein) (Welle et al., 2003). Instead, an increase in point mutations within the mitochondrial DNA control region may result in a poor template for replication thereby preventing enhanced replication to compensate for the loss of degraded DNA.

mtDNA strand breaks as a result of oxidative damage have also been shown to be involved in pathways of cell death. Oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) is an enzyme involved in base excision repair of 8-oxo-dG lesions. Fibroblasts deficient in mitochondrial OGG1 were treated with menadione to induce oxidative damage. Reduced mtDNA levels were accompanied by decreased levels of ATP, a decline in the mitochondrial membrane potential, and mitochondrial calcium levels in these cells (Oka et al., 2008). Menadione treatment also increased the activity of the calcium activated protease calpain and cell death, providing a mechanism by which mtDNA strand breaks lead to cell death. In contrast, OGG1-null mice display normal mitochondrial function despite a 20-fold increase in 8-oxo-dG levels (Stuart et al., 2005). Of course, 8-oxo-dG is not the only oxidative lesion in mtDNA and may not be the major cause of functional decline.

4. Changes in Mitochondrial Function with Aging

Although there is some question concerning the physiological impact of many reported age-related changes to mtDNA, it remains a distinct possibility that even small changes to mtDNA integrity could exert trickle-down effects, ultimately altering the overall function of mitochondria. Damage, deletions, or mutations to mtDNA are likely to influence downstream processes such as transcription, translation, enzyme activity, mitochondrial ATP synthesis, and overall organ function.

Transcription

At the transcriptional level, several studies have found that mRNA levels corresponding to proteins encoded by mtDNA are reduced with age. Welle et al. used serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) and quantitative RT-PCR to demonstrate that the relative concentrations of mtDNA transcripts were lower in skeletal muscle from older compared to young humans (Welle et al., 2003). Specific transcripts included mRNAs encoding proteins involved in electron transport and ATP synthesis (subunits of cytochrome-c-oxidase, NADH dehydrogenase, cytochrome b, and ATP synthase). A subsequent study confirmed this observation in rats, but demonstrated that the age-related reduction in mtDNA encoded cytochrome c oxidase subunit 3 (COX3) mRNA was tissue-specific (Barazzoni et al., 2000). The most striking reduction in mRNA abundance was observed in glycolytic skeletal muscle (lateral gastrocnemius), but the effects of age were less apparent in more oxidative skeletal muscle (medial gastrocnemius, soleus) and completely absent in liver and heart muscle (Barazzoni et al., 2000). A more recent study measured COX3 mRNA abundance in skeletal muscle of humans aged 18-89 years and found a negative correlation between age and mRNA expression with an overall rate of decline of 10% per decade (Short et al., 2005a). Numerous factors could contribute to an age-related decline in transcripts originating from the mitochondrial genome, including decreased rate of transcription, decreased mRNA stability in post-transcriptional pathways, and decreased mtDNA copy number, all of which may occur as a result of environmental influences such as physical activity levels, diet, and medications. Although there is some evidence to support an age-related reduction in the transcription efficiency of mtDNA (Fernandez-Silva et al., 1991), other data points to a reduction in mtDNA abundance with aging (Barazzoni et al., 2000; Short et al., 2005a; Lanza et al., 2008) as a potentially limiting factor for mitochondrial gene expression. However, there is not always stoichiometry between mtDNA abundance (template) and mRNA expression (transcript). Barrazoni et al. found that mtDNA copy number decreased with age in tissues in which there were no observed decreases in COX3 mRNA expression (liver and soleus muscle) (Barazzoni et al., 2000). Thus, it seems that transcript levels do not always follow template availability and mRNA stability and transcriptional efficiency may be more important determinants of transcript availability than the amount of template present.

Translation

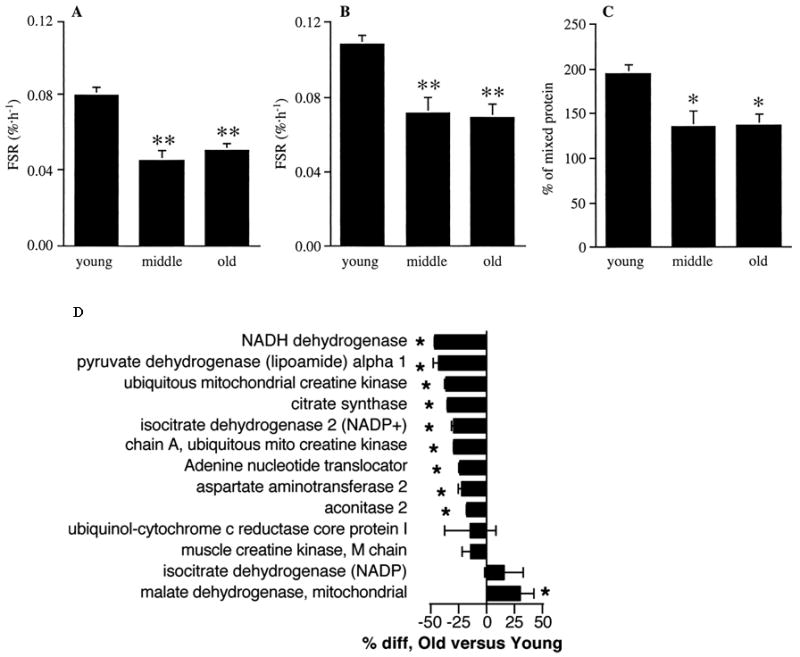

It is conceivable that modifications to mtDNA could affect the translation of mtDNA-encoded proteins as a consequence of the aforementioned effects on gene transcript levels. The rate at which amino acids are assembled into polypeptide chains and eventually functional proteins is not only dependent on the quantity of transcriptional message, but also on the availability of tRNA and function of translational machinery, the so-called “mitoribosomes.” Various studies have provided evidence of decreased translational rates with aging, as evidenced by lower synthesis rates of mitochondrial proteins. Early experiments measured mitochondrial protein synthesis rates in vitro from the incorporation of radiolabelled amino acid tracers in isolated mitochondria. Such experiments in Drosophila, mice, and rat tissues revealed that the synthesis rates of mitochondrial proteins decreased with advancing age of the organism (Marcus et al., 1982a; Marcus et al., 1982b; Bailey and Webster, 1984). In 1996, Rooyackers et al. used stable isotopes of amino acids to measure the in vivo synthesis rates of mitochondrial proteins in human skeletal muscle (Figure 3a-c) (Rooyackers et al., 1996). By infusing an amino acid tracer and measuring the incorporation of the label into mitochondrial protein fractions, this study found that mitochondrial protein synthesis rates were ∼40% lower in middle aged (54 years) compared to young (24 years) men and women, which could be related to reduced transcript abundance. Although no further decline was observed between middle aged and older (73 years) individuals, this study was the first to demonstrate an age-related reduction in the translational rate of gene transcripts.

Figure 3.

Protein synthesis rates and content of muscle mitochondrial proteins. Fractional synthesis rates (FSR) of skeletal muscle mitochondrial protein using plasma [13C]KIC (A) and tissue fluid [13C]leucine (B) as precursor pool enrichment, and as a percentage of mixed protein synthesis rates (C) in young, middle-aged, and old human subjects. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 versus young. (D) Relative abundance of mitochondrial proteins in muscle from young and older subjects. The percentage difference (*, P < 0.05) of older relative to young is shown. Negative values indicate less protein in older subjects. Taken with permission from Rooyackers et al., 1996 and Short et al., 2005a.

The coordinated synthesis and degradation of proteins ensures that mitochondrial proteins are continually turned over so that damaged, dysfunctional proteins are replaced with new proteins that function properly. The observed reduction in mitochondrial protein synthesis with aging could lead to decreased protein expression if the degradation rate remains constant or decreases. Conversely, if protein synthesis and breakdown both decrease with age, the net expression of mitochondrial proteins may not decrease, however the function of the protein pool may be impaired because of decreased overall turnover. Our understanding of the effects of age on protein synthesis is expanding rapidly, particularly with the recent development of novel methodology to measure in vivo synthesis rates of individual proteins (Jaleel et al., 2008). To our knowledge, no studies have measured specific rates of mitochondrial protein breakdown in vivo. Some more indirect evidence supports the possibility that aging may decrease the rate of mitochondrial protein breakdown. Henderson et al. found that whole-body proteolysis decreased with age in humans, measured by phenylalanine rate of appearance during a primed, continuous infusion of [15N] phenylalanine (Henderson et al., 2009). The in vivo synthesis rates of specific skeletal muscle proteins such as myosin heavy chain decline with aging (Balagopal et al., 1997), which may explain the overall decline in MHC expression (specifically type II) with aging (Short et al., 2005b). Aerobic exercise increased MHCI and IIa mRNA expression in young and old; an effect that appears to be transcriptionally mediated (Short et al., 2005b). Specific to mitochondrial proteins, an age-related decline in Lon protease expression, a key enzyme in mitochondrial proteolysis, is reduced with aging in mice (Bota et al., 2002). Thus, there is evidence to support the notion of decreased mitochondrial protein turnover with aging, which would slow the clearance rate of proteins whose function may be compromised by post-translational modifications. Indeed, protein carbonylation and nitrotyrosine-modified proteins are more abundant with old age (Fugere et al., 2006; Hepple et al., 2008).

Although preliminary evidence suggests that both mitochondrial protein synthesis and degradation decrease with age, there appears to be an imbalance between the two rates such that overall expression of mitochondrial proteins decreased with aging. This was demonstrated using isotope-coated affinity tags (ICATs) and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to determine the relative abundance of several mitochondrial proteins in muscle biopsy tissue from young and older men and women (Figure 3d) (Short et al., 2005a). This study found that several mitochondrial proteins, including proteins encoded by nuclear DNA and mtDNA, were significantly less abundant in skeletal muscle of older adults. A more recent study from our group found similar reductions in many mitochondrial proteins using a similar LC-MS/MS approach using isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) (Lanza et al., 2008). In sum, it is clear that aging not only affects the abundance of mitochondrial gene transcripts, but also the translation of mitochondrial proteins, ultimately affecting protein expression.

Enzyme activity

The 13 polypeptides encoded by mitochondrial DNA are specific subunits of 4 of the 5 respiratory chain proteins (NADH dehydrogenase subunits 1-6, cytochrome b, cytochrome c oxidase, and ATP synthase). Succinate dehydrogenase (complex II) is the only respiratory chain protein that is entirely coded by nuclear DNA with the remainder originating from both genomes. Here it becomes important to emphasize that none of the respiratory chain complexes are encoded exclusively by mtDNA. Even respiratory chain complexes that contain mtDNA-encoded subunits also contain substantial components that are nuclear-encoded (i.e., Complexes I, III, IV, and V). Once the individual protein subunits are translated, they are transported into the mitochondrion, and assembled into functional complexes whose activity depends on the overall abundance of the protein complexes as well as post-translational factors that may influence the activity of the enzyme independently of its expression. Given the abundance of factors that can impact the activity of a particular enzyme, it is difficult to ascribe causality to a particular gene on a particular genome. Notwithstanding, it remains a distinct likelihood that enzyme activity may be affected by distant upstream events such as modifications to the structure, integrity, or abundance of mtDNA that may exert trickle down influence on activity. A large number of studies have reported on the effects of age on mitochondrial enzyme activities with varied results. Numerous studies indicate that the activities of mitochondrial enzymes such as citrate synthase (CS) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) decrease with age (Papa, 1996; Rooyackers et al., 1996; Barazzoni et al., 2000; Welle et al., 2003; Short et al., 2005a) but many studies have also found that the activities of these enzymes are unaffected by aging (Larsson et al., 1978; Grimby et al., 1982; Aniansson et al., 1986; Trappe et al., 1995; Rasmussen et al., 2003a, 2003b). To further cloud the issue, other studies have found that the effects of age on enzyme activity are tissue-specific (Houmard et al., 1998). Much of this noise in the literature may be explained by varying degrees of physical activity of research volunteers since the activity of mitochondrial enzymes clearly increases with physical activity (Holloszy, 1967). The ease at which these enzyme activities can be measured spectrophotometrically from small amounts of previously frozen tissue samples have popularized their widespread use as proxies for tissue mitochondrial function. However, one should not rely on the activity of a single enzyme as an accurate index of the collective function of an organelle whose function is dependent on complex interaction among multiple enzyme complexes.

Mitochondrial function

Measurement of ATP production in functional, intact mitochondria or at the whole tissue level arguably represents the most direct assessment of mitochondrial function. Alternatively, the rate of oxygen consumption in isolated mitochondria in vitro, intact tissue in situ, or the whole organism in vivo may be used as another index of mitochondrial function, assuming fixed stoichiometry between the consumption of oxygen and synthesis of ATP. Many of these approaches have been applied to investigate the effects of age on mitochondrial function. The current consensus on the effects of age is that there is no consensus. Table 1 highlights many published studies that have applied a variety of in vivo and in vitro methodologies to examine the effects of age on human skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. The details of many of these studies are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Table 1.

Effects of age on mitochondrial function

| Reference | Tissue | Measurement | Age effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro studies | |||

| Barrientos et al., 1996 | Vastus lateralis | Isolated mitochondria respiration | ↔ |

| Boffoli et al., 1996 | Vastus lateralis | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Brierley et al., 1996 | Vastus lateralis | Isolated mitochondria respiration | ↔ |

| Chretien et al., 1998 | Deltoid | ↔ | |

| Coggan et al., 1992 | Lateral gastrocnemius | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Houmard et al., 1998 | Vastus lateralis | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Lateral gastrocnemius | ↔ | ||

| Hutter et al., 2007 | Vastus Lateralis | Permeabilized fiber respiration | ↔ |

| Lanza et al., 2008 | Vastus lateralis | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Isolated mitochondria ATP synthesis | ↓ | ||

| McCully et al., 1993 | Lateral gastrocnemius | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Meredith et al., 1989 | Vastus lateralis | Tissue homogenate respiration | ↓ |

| Pastoris et al., 2000 | Vastus lateralis | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Gluteus maximus | ↔ | ||

| Rectus abdominus | ↔ | ||

| Proctor et al., 1995 | Vastus lateralis | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Rasmussen et al., 2003 | Vastus lateralis | Isolated mitochondria respiration | ↔ |

| Rasmussen et al., 2003 | Vastus lateralis | Isolated mitochondria respiration | ↔ |

| Rooyackers et al., 1996 | Vastus lateralis | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Short et al., 2005 | Vastus lateralis | Isolated mitochondria ATP synthesis | ↓ |

| Short et al., 2003 | Vastus lateralis | Enzyme activity | ↓ |

| Tonkonogi et al., 2003 | Vastus lateralis | Isolated mitochondria and permeabilized | ↓ |

| fiber respiration | ↓ | ||

| Trounce et al., 1989 | Vastus lateralis | Isolated mitochondria respiration | ↔ |

| In vivo studies (basal ATP flux) | |||

| Amara et al., 2007 | Tibialis anterior | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↔ |

| First dorsal interosseus | Near-infrared spectroscopy | ↓ | |

| Petersen et al., 2003 | Soleus | Basal oxidation (13C-MRS) and phosphorylation (31P-MRS) | ↓ |

| In vivo studies (maximal ATP flux) | |||

| Chilibeck et al., 1998 | Gastrocnemius | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↔ |

| Conley et al., 2000 | Vastus lateralis | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↓ |

| Kent-braun and Ng, 2000 | Tibialis anterior | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↔ |

| Lanza et al., 2005 | Tibialis anterior | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↔ |

| Lanza et al., 2007 | Tibialis anterior | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↔ |

| McCully et al., 1991 | Lateral gastrocnemius | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↓ |

| McCully et al., 1993 | Lateral Gastrocnemius | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↓ |

| Schunk et al., 1999 | Vastus lateralis | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↔ |

| Taylor et al., 1997 | Calf | 31P-MRS PCr kinetics | ↔ |

Several studies of mitochondria isolated from human muscle biopsy tissue support the notion of an age-related decline in mitochondrial function (Table 1). For example, we recently measured maximal ATP synthesis rates with substrates supporting electron flow through respiratory chain complexes I and II in mitochondria isolated from vastus lateralis muscle in men and women across a large age range (Figure 2b) (Short et al., 2005a). We observed a negative relationship between age and ATP synthesis with an overall reduction of 8% when expressed per milligram of tissue and 5% per decade after normalizing for mitochondrial protein content (Short et al., 2005a). These data indicate that tissue oxidative capacity declines with aging and that this decline cannot be entirely accounted for by a decline in mitochondrial content. Another recent study found that ATP synthesis declined with age when expressed per tissue weight, but this age effect was still evident when expressed per mitochondrial protein content, although not to the same degree of statistical significance (Karakelides et al., 2009). In other words, we provide evidence of an intrinsic mitochondrial defect with aging that limits the capacity to generate ATP when the appropriate substrates are provided. This finding is in agreement with some, but not all previously published observations in isolated mitochondria. Several other groups are unable to detect age-related differences in respiration rates of mitochondria isolated from the same muscle group (Trounce et al., 1989; Barrientos et al., 1996; Brierley et al., 1996; Rasmussen et al., 2003a, 2003b). Although ATP synthesis and oxygen consumption are generally well-correlated, it is conceivable that oxygen consumption rates may remain constant in spite of declining ATP synthesis if the degree of mitochondrial coupling is affected by age, as shown in aging mice (Marcinek et al., 2005).

Studies of intact, permeabilized muscle fibers provide a slightly less reductionist approach to assessing mitochondrial function. In these preparations, muscle fiber bundles are isolated from human biopsy tissue and chemically permeabilized to allow the passage of substrates across the plasma membrane. An advantage of this approach is that measurements can be made from the entire population of mitochondria rather than just those that are easily liberated from the homogenized tissue. Furthermore, measurements are made with intact intracellular circulatory and regulatory systems that are likely to be important factors in the function of the organelles. Such in situ measurements have revealed a similar lack of agreement concerning the effects of age as measurements performed in isolated mitochondria. For example, Tonkonogi et al. report decreased respiration rates (Tonkonogi et al., 2003), whereas Hutter et al. observe no such age-related declines (Hutter et al., 2007).

In vitro and in situ methods are vital to investigating intrinsic organelle function at distinct points along the respiratory chain and provide essential mechanistic information. However, one could argue that the conditions under which these experiments are performed (e.g., saturating substrate concentrations, optimal enzyme conditions, high oxygen tension) are not representative of true physiological conditions, and the results may not be physiologically relevant. The pioneering work of Britton Chance demonstrated that phosphorous magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS) could be used to non-invasively assess human muscle energetics (Chance et al., 1980). Several investigators have now applied various 31P-MRS based methods to examine the impact of aging on mitochondrial function measured in vivo. Similar to ex vivo studies discussed above, these studies find that either muscle oxidative capacity decreases (McCully et al., 1991; McCully et al., 1993; Conley et al., 2000) or remains unchanged with age (Taylor et al., 1997; Chilibeck et al., 1998; Schunk et al., 1999; Kent-Braun and Ng, 2000; Lanza et al., 2005; Lanza et al., 2007). A notable study by Kent-Braun and Ng measured oxidative capacity in the tibialis anterior muscle using a kinetic analysis of phosphocreatine recovery following a brief muscle contraction (Kent-Braun and Ng, 2000). The lack of an age-effect in this study was attributed to the careful control of the physical activity patterns in the two age groups such that this variable would not confound the comparison of oxidative capacity with aging, as reviewed elsewhere (Russ and Kent-Braun, 2004). Interestingly, Amara et al., found that oxidative capacity was similar in young and old tibialis anterior muscle, but decreased with age in the first dorsal interosseus (Amara et al., 2007). Thus, there is in vivo evidence that not all tissues are affected the same way by the aging process and may partly explain some of the discrepant findings in the literature.

In contrast to in vivo studies that have measured tissue oxidative capacity, Petersen et al. measured steady-state basal ATP flux using a unique 31P-MRS approach. These investigators found that the basal oxidative phosphorylation flux was reduced by nearly 50% in older compared to young individuals (Petersen et al., 2003). Additional studies are needed to clarify the extent to which a decline in basal ATP flux is due to a reduction in oxidative capacity, lower mitochondrial content in the tissue, reduced oxygen or substrate delivery, or other vascular factors. Notwithstanding, these data clearly reveal that skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics are significantly altered with old age, even in the resting state. Overall, studies performed in humans in vivo indicate that the effect of aging per se on mitochondrial function continues to be a topic of heated debate, particularly in consideration of lifestyle changes (e.g., physical activity, nutrition) that may influence mitochondrial function. Furthermore, it remains to be determined the degree to which many of the downstream effects are related to defects at the level of mtDNA, nuclear DNA, or synergy between both genomes.

5. Threshold effects

The previous paragraphs have reviewed much of the evidence linking aging with changes downstream from the mitochondrial genome. A lingering question is: to what extent can the documented changes in transcript levels, translational rates, protein expression, enzyme activity, and mitochondrial function be related back to mtDNA mutations and deletions that occur with aging? The answer to this is not straightforward, but much insight can be gleaned from a large body of literature supporting the notion of “mitochondrial threshold effects.” As reviewed elsewhere (Rossignol et al., 2003), this theory posits that a specific level of heteroplasmy (mutant mtDNA vs. wild-type mtDNA) is required to induce a significantly altered phenotype. When the percent heteroplasmy remains below this critical threshold, there is sufficient reserve or redundancy to provide an effective safety margin. At the level of gene transcription, there appears to be proportionality between mtDNA mutations and mRNA mutations (Hayashi et al., 1991). At the level of translation, various studies have found that between 40 and 50% heteroplasmy is required to affect mitochondrial protein translation (Hayashi et al., 1991; Boulet et al., 1992). An even more robust threshold effect is observed at the level of enzyme activity. For example, cytochrome c oxidase activity was unaffected at 50% heteroplasmy where substantial reductions in protein translation were observed (Boulet et al., 1992). Finally, the manifestation of a metabolic phenotype (i.e., altered mitochondrial function) will depend on a threshold level of diminished enzyme activity. An interesting clinical example is that of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy where mtDNA mutations exists at several genes encoding subunits of complex I (homoplasmic), but these patients exhibit completely normal mitochondrial function in calf muscle assessed by 31P-MRS (Lodi et al., 2002). These investigators speculate that the nuclear genetic environment plays a key role in compensating for the specific mtDNA mutation in these patients. Since mitochondrial ATP production is the result of convergent electron flow through several protein complexes, it is probable that a defect in the expression or activity of a single protein is compensated for by greater electron flux through other electron carriers or a sufficient reserve of wild-type proteins to buffer the effects of the mutation. The precise thresholds for mtDNA mutations exhibiting altered phenotypes seems to vary considerably depending on the type of mutation and organism / tissue of interest, but a unifying theme seems to be that there is sufficient redundancy at various levels such that a substantial degree of heteroplasmy would be required to observe an altered phenotype. The interested reader is pointed to an excellent review on this topic (Rossignol et al., 2003).

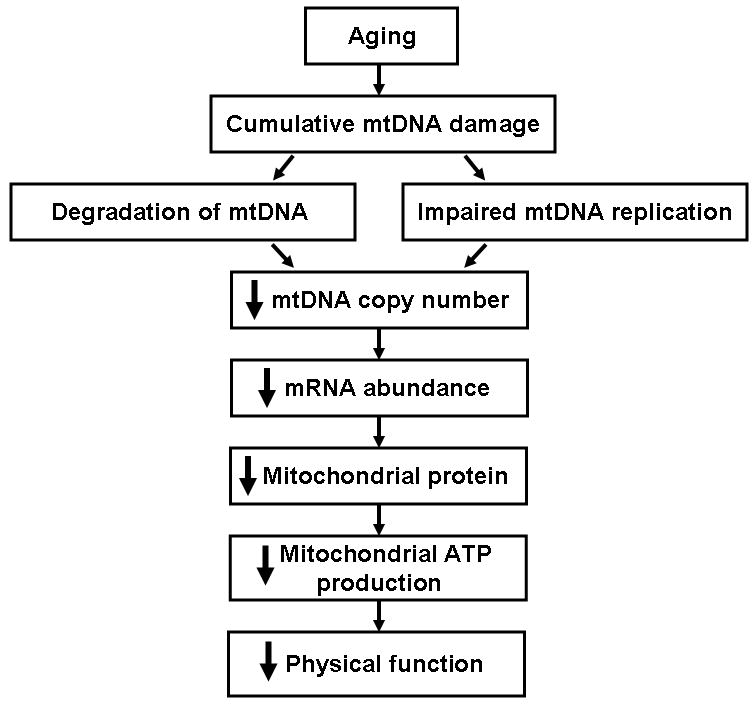

6. Summary

The exact mechanism responsible for the decline in mitochondrial function with aging remains to be determined. A proposed model is presented in Figure 4. Oxidative damage increases with age and can result in alterations of the mitochondrial genome including point mutations, deletions, and DNA strand breaks. The extent of mutations and deletions within a tissue increase with aging, however, the overall mutational load typically remains low. Recent evidence that oxidatively damaged mtDNA is degraded may explain the decline in mtDNA abundance that occurs during aging. A reduction in template availability and point mutations within the control region (D-loop) could both result in reduced mtDNA replication and an inability to compensate for the loss of damaged genomes. The decline in mtDNA abundance likely contributes to other downstream age-related deficiencies including reduced transcript and protein levels and reduced ATP synthesis.

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial DNA damage accumulates with aging. Damaged DNA may impair mitochondrial DNA replication and/or induce mitochondrial DNA degradation, both of which could result in a decline in levels of mitochondrial DNA, mRNA, and protein. Reduced levels of mitochondrial proteins could result in decreased ATP synthesis and an eventual decline in physical function.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by NIH grants RO1-AG09531, UL1-RR024150, T32-DK07352 (S. L. Hebert), and the David Murdock-Dole Professorship (K. S. Nair).

Abbreviations

- FapyG

2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine

- FapyA

4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine

- 8-oxo-dG

8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine

- COX

Cytochrome c oxidase

- D-loop

Displacement loop

- FA

Fatty acid

- mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA

- OGG1

Oxoguanine DNA glycosylase

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- UCP

Uncoupling protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amara CE, Shankland EG, Jubrias SA, Marcinek DJ, Kushmerick MJ, Conley KE. Mild mitochondrial uncoupling impacts cellular aging in human muscles in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1057–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610131104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, de Bruijn MH, Coulson AR, Drouin J, Eperon IC, Nierlich DP, Roe BA, Sanger F, Schreier PH, Smith AJ, Staden R, Young IG. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290:457–65. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aniansson A, Hedberg M, Henning GB, Grimby G. Muscle morphology, enzymatic activity, and muscle strength in elderly men: a follow-up study. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:585–91. doi: 10.1002/mus.880090702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anson RM, Hudson E, Bohr VA. Mitochondrial endogenous oxidative damage has been overestimated. Faseb J. 2000;14:355–60. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey LJ, Cluett TJ, Reyes A, Prolla TA, Poulton J, Leeuwenburgh C, Holt IJ. Mice expressing an error-prone DNA polymerase in mitochondria display elevated replication pausing and chromosomal breakage at fragile sites of mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2327–35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey PJ, Webster GC. Lowered rates of protein synthesis by mitochondria isolated from organisms of increasing age. Mech Ageing Dev. 1984;24:233–41. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(84)90074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopal P, Rooyackers OE, Adey DB, Ades PA, Nair KS. Effects of aging on in vivo synthesis of skeletal muscle myosin heavy-chain and sarcoplasmic protein in humans. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E790–800. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.4.E790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barazzoni R, Short KR, Nair KS. Effects of aging on mitochondrial DNA copy number and cytochrome c oxidase gene expression in rat skeletal muscle, liver, and heart. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3343–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos A, Casademont J, Rotig A, Miro O, Urbano-Marquez A, Rustin P, Cardellach F. Absence of relationship between the level of electron transport chain activities and aging in human skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:536–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb MJ, Van Etten RA, Wright CT, Walberg MW, Clayton DA. Sequence and gene organization of mouse mitochondrial DNA. Cell. 1981;26:167–80. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodyak ND, Nekhaeva E, Wei JY, Khrapko K. Quantification and sequencing of somatic deleted mtDNA in single cells: evidence for partially duplicated mtDNA in aged human tissues. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:17–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss O, Samec S, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Rossier C, Dulloo A, Seydoux J, Muzzin P, Giacobino JP. Uncoupling protein-3: a new member of the mitochondrial carrier family with tissue-specific expression. FEBS Lett. 1997;408:39–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bota DA, Van Remmen H, Davies KJ. Modulation of Lon protease activity and aconitase turnover during aging and oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:103–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet L, Karpati G, Shoubridge EA. Distribution and threshold expression of the tRNA(Lys) mutation in skeletal muscle of patients with myoclonic epilepsy and ragged-red fibers (MERRF) Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:1187–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley EJ, Johnson MA, James OF, Turnbull DM. Effects of physical activity and age on mitochondrial function. Qjm. 1996;89:251–8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.4.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas S, Buckingham JA, Samec S, Seydoux J, Din N, Dulloo AG, Brand MD. UCP2 and UCP3 rise in starved rat skeletal muscle but mitochondrial proton conductance is unchanged. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:257–60. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calloway CD, Reynolds RL, Herrin GL, Jr, Anderson WW. The frequency of heteroplasmy in the HVII region of mtDNA differs across tissue types and increases with age. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1384–97. doi: 10.1086/302844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candeias LP, Steenken S. Reaction of HO* with guanine derivatives in aqueous solution: formation of two different redox-active OH-adduct radicals and their unimolecular transformation reactions. Properties of G(-H)*. Chemistry. 2000;6:475–84. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(20000204)6:3<475::aid-chem475>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DC. Mitochondria: dynamic organelles in disease, aging, and development. Cell. 2006;125:1241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Eleff S, Leigh JS., Jr Noninvasive, nondestructive approaches to cell bioenergetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:7430–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilibeck PD, McCreary CR, Marsh GD, Paterson DH, Noble EG, Taylor AW, Thompson RT. Evaluation of muscle oxidative potential by 31P-MRS during incremental exercise in old and young humans. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1998;78:460–5. doi: 10.1007/s004210050446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow LS, Greenlund LJ, Asmann YW, Short KR, McCrady SK, Levine JA, Nair KS. Impact of endurance training on murine spontaneous activity, muscle mitochondrial DNA abundance, gene transcripts, and function. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:1078–89. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00791.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JM, Beardsley GP. Functional effects of cis-thymine glycol lesions on DNA synthesis in vitro. Biochemistry. 1987;26:5398–403. doi: 10.1021/bi00391a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KE, Jubrias SA, Esselman PC. Oxidative capacity and ageing in human muscle. J Physiol. 2000;526(Pt 1):203–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Debrinski M, Horton T, Lott MT, Shoffner JM, Beal MF, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA deletions in human brain: regional variability and increase with advanced age. Nat Genet. 1992;2:324–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortopassi GA, Shibata D, Soong NW, Arnheim N. A pattern of accumulation of a somatic deletion of mitochondrial DNA in aging human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7370–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford DR, Abramova NE, Davies KJ. Oxidative stress causes a general, calcium-dependent degradation of mitochondrial polynucleotides. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:1106–11. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza-Pinto NC, Eide L, Hogue BA, Thybo T, Stevnsner T, Seeberg E, Klungland A, Bohr VA. Repair of 8-oxodeoxyguanosine lesions in mitochondrial dna depends on the oxoguanine dna glycosylase (OGG1) gene and 8-oxoguanine accumulates in the mitochondrial dna of OGG1-defective mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5378–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bo R, Bordoni A, Martinelli Boneschi F, Crimi M, Sciacco M, Bresolin N, Scarlato G, Comi GP. Evidence and age-related distribution of mtDNA D-loop point mutations in skeletal muscle from healthy subjects and mitochondrial patients. J Neurol Sci. 2002;202:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bo R, Crimi M, Sciacco M, Malferrari G, Bordoni A, Napoli L, Prelle A, Biunno I, Moggio M, Bresolin N, Scarlato G, Pietro Comi G. High mutational burden in the mtDNA control region from aged muscles: a single-fiber study. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:829–38. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney MO, Wiederholt CJ, Greenberg MM. Fapy.dA induces nucleotide misincorporation translesionally by a DNA polymerase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:771–3. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020301)41:5<771::aid-anie771>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulloo AG, Samec S, Seydoux J. Uncoupling protein 3 and fatty acid metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:785–91. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar D, Shabalina I, Camara Y, Wredenberg A, Calvaruso MA, Nijtmans L, Nedergaard J, Cannon B, Larsson NG, Trifunovic A. Random point mutations with major effects on protein-coding genes are the driving force behind premature aging in mtDNA mutator mice. Cell Metab. 2009;10:131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Silva P, Petruzzella V, Fracasso F, Gadaleta MN, Cantatore P. Reduced synthesis of mtRNA in isolated mitochondria of senescent rat brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176:645–53. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleury C, Neverova M, Collins S, Raimbault S, Champigny O, Levi-Meyrueis C, Bouillaud F, Seldin MF, Surwit RS, Ricquier D, Warden CH. Uncoupling protein-2: a novel gene linked to obesity and hyperinsulinemia. Nat Genet. 1997;15:269–72. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frahm T, Mohamed SA, Bruse P, Gemund C, Oehmichen M, Meissner C. Lack of age-related increase of mitochondrial DNA amount in brain, skeletal muscle and human heart. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:1192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugere NA, Ferrington DA, Thompson LV. Protein nitration with aging in the rat semimembranosus and soleus muscles. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:806–12. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.8.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilkerson RW. Mitochondrial DNA nucleoids determine mitochondrial genetics and dysfunction. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokey NG, Cao Z, Pak JW, Lee D, McKiernan SH, McKenzie D, Weindruch R, Aiken JM. Molecular analyses of mtDNA deletion mutations in microdissected skeletal muscle fibers from aged rhesus monkeys. Aging Cell. 2004;3:319–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimby G, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, Hvid K, Saltin B. Morphology and enzymatic capacity in arm and leg muscles in 78-81 year old men and women. Acta Physiol Scand. 1982;115:125–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1982.tb07054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton ML, Guo Z, Fuller CD, Van Remmen H, Ward WF, Austad SN, Troyer DA, Thompson I, Richardson A. A reliable assessment of 8-oxo-2-deoxyguanosine levels in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA using the sodium iodide method to isolate DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001a;29:2117–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.10.2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton ML, Van Remmen H, Drake JA, Yang H, Guo ZM, Kewitt K, Walter CA, Richardson A. Does oxidative damage to DNA increase with age? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001b;98:10469–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171202698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman D. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1972;20:145–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatahet Z, Purmal AA, Wallace SS. Oxidative DNA lesions as blocks to in vitro transcription by phage T7 RNA polymerase. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;726:346–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb52847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi J, Ohta S, Kikuchi A, Takemitsu M, Goto Y, Nonaka I. Introduction of disease-related mitochondrial DNA deletions into HeLa cells lacking mitochondrial DNA results in mitochondrial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10614–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson GC, Dhatariya K, Ford GC, Klaus KA, Basu R, Rizza RA, Jensen MD, Khosla S, O'Brien P, Nair KS. Higher muscle protein synthesis in women than men across the lifespan, and failure of androgen administration to amend age-related decrements. Faseb J. 2009;23:631–41. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepple RT, Qin M, Nakamoto H, Goto S. Caloric restriction optimizes the proteasome pathway with aging in rat plantaris muscle: implications for sarcopenia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1231–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90478.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst A, Pak JW, McKenzie D, Bua E, Bassiouni M, Aiken JM. Accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations in aged muscle fibers: evidence for a causal role in muscle fiber loss. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:235–45. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO. Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:2278–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmard JA, Weidner ML, Gavigan KE, Tyndall GL, Hickey MS, Alshami A. Fiber type and citrate synthase activity in the human gastrocnemius and vastus lateralis with aging. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:1337–41. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.4.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmiel KL, Gerschenson M, Low RL. Mitochondrial endonuclease activity in the rat varies markedly among tissues in relation to the rate of tissue metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1079:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90125-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, de Souza-Pinto NC, Haraguchi K, Hogue BA, Jaruga P, Greenberg MM, Dizdaroglu M, Bohr VA. Repair of formamidopyrimidines in DNA involves different glycosylases: role of the OGG1, NTH1, and NEIL1 enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40544–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter E, Skovbro M, Lener B, Prats C, Rabol R, Dela F, Jansen-Durr P. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment can be separated from lipofuscin accumulation in aged human skeletal muscle. Aging Cell. 2007;6:245–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide H, Kow YW, Wallace SS. Thymine glycols and urea residues in M13 DNA constitute replicative blocks in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:8035–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.22.8035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S, Ozaki K. Action of mitochondrial endonuclease G on DNA damaged by L-ascorbic acid, peplomycin, and cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:291–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel A, Short KR, Asmann YW, Klaus KA, Morse DM, Ford GC, Nair KS. In vivo measurement of synthesis rate of individual skeletal muscle mitochondrial proteins. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1255–68. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90586.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga P, Speina E, Gackowski D, Tudek B, Olinski R. Endogenous oxidative DNA base modifications analysed with repair enzymes and GC/MS technique. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E16. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezek P, Garlid KD. Mammalian mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:1163–8. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karahalil B, de Souza-Pinto NC, Parsons JL, Elder RH, Bohr VA. Compromised incision of oxidized pyrimidines in liver mitochondria of mice deficient in NTH1 and OGG1 glycosylases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33701–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakelides H, Irving BA, Short KR, O'Brien P, Nair KS. Age, obesity, and sex effects on insulin sensitivity and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Diabetes. 2009 doi: 10.2337/db09-0591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent-Braun JA, Ng AV. Skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in young and older women and men. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1072–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khrapko K, Nekhaeva E, Kraytsberg Y, Kunz W. Clonal expansions of mitochondrial genomes: implications for in vivo mutational spectra. Mutat Res. 2003;522:13–9. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraytsberg Y, Simon DK, Turnbull DM, Khrapko K. Do mtDNA deletions drive premature aging in mtDNA mutator mice? Aging Cell. 2009;8:502–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy N, Haraguchi K, Greenberg MM, David SS. Efficient removal of formamidopyrimidines by 8-oxoguanine glycosylases. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1043–50. doi: 10.1021/bi701919u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan KJ, Reeve AK, Samuels DC, Chinnery PF, Blackwood JK, Taylor RW, Wanrooij S, Spelbrink JN, Lightowlers RN, Turnbull DM. What causes mitochondrial DNA deletions in human cells? Nat Genet. 2008;40:275–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.f.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krokan HE, Standal R, Slupphaug G. DNA glycosylases in the base excision repair of DNA. Biochem J. 1997;325(Pt 1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3250001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujoth GC, Hiona A, Pugh TD, Someya S, Panzer K, Wohlgemuth SE, Hofer T, Seo AY, Sullivan R, Jobling WA, Morrow JD, Van Remmen H, Sedivy JM, Yamasoba T, Tanokura M, Weindruch R, Leeuwenburgh C, Prolla TA. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309:481–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Befroy DE, Kent-Braun JA. Age-related changes in ATP-producing pathways in human skeletal muscle in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1736–44. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00566.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Larsen RG, Kent-Braun JA. Effects of old age on human skeletal muscle energetics during fatiguing contractions with and without blood flow. J Physiol. 2007;583:1093–105. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Short DK, Short KR, Raghavakaimal S, Basu R, Joyner MJ, McConnell JP, Nair KS. Endurance exercise as a countermeasure for aging. Diabetes. 2008;57:2933–42. doi: 10.2337/db08-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L, Sjodin B, Karlsson J. Histochemical and biochemical changes in human skeletal muscle with age in sedentary males, age 22--65 years. Acta Physiol Scand. 1978;103:31–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson NG, Wang J, Wilhelmsson H, Oldfors A, Rustin P, Lewandoski M, Barsh GS, Clayton DA. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat Genet. 1998;18:231–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0398-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CK, Klopp RG, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene expression profile of aging and its retardation by caloric restriction. Science. 1999;285:1390–3. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5432.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jeong SY, Lim WC, Kim S, Park YY, Sun X, Youle RJ, Cho H. Mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators, hFis1 and OPA1, modulate cellular senescence. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22977–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legros F, Lombes A, Frachon P, Rojo M. Mitochondrial fusion in human cells is efficient, requires the inner membrane potential, and is mediated by mitofusins. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4343–54. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnane AW, Marzuki S, Ozawa T, Tanaka M. Mitochondrial DNA mutations as an important contributor to ageing and degenerative diseases. Lancet. 1989;1:642–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu VW, Zhang C, Nagley P. Mutations in mitochondrial DNA accumulate differentially in three different human tissues during ageing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1268–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodi R, Carelli V, Cortelli P, Iotti S, Valentino ML, Barboni P, Pallotti F, Montagna P, Barbiroli B. Phosphorus MR spectroscopy shows a tissue specific in vivo distribution of biochemical expression of the G3460A mutation in Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:805–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lluch G, Irusta PM, Navas P, de Cabo R. Mitochondrial biogenesis and healthy aging. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:813–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low RL. Mitochondrial Endonuclease G function in apoptosis and mtDNA metabolism: a historical perspective. Mitochondrion. 2003;2:225–36. doi: 10.1016/S1567-7249(02)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]