Abstract

The erythrocyte is exposed to reactive oxygen species in the circulation and also to those produced by autoxidation of hemoglobin. Consequently, erythrocytes depend on protection by the antioxidant glutathione. Mathematical models based on realistic kinetic data have provided valuable insights into the regulation of biochemical pathways within the erythrocyte but none have satisfactorily accounted for glutathione metabolism. In the current model, rate equations were derived for the enzyme-catalyzed reactions, and for each equation the nonlinear algebraic relationship between the steady-state kinetic parameters and the unitary rate constants was derived. The model also includes the transport processes that supply the amino acid constituents of glutathione and the export of oxidized glutathione. Values of the kinetic parameters for the individual reactions were measured predominately using isolated enzymes under conditions that differed from the intracellular environment. By comparing the experimental and simulated results, the values of the enzyme-kinetic parameters of the model were refined to yield conformity between model simulations and experimental data. Model output accurately represented the steady-state concentrations of metabolites in erythrocytes suspended in plasma and the changing glutathione concentrations in whole and hemolyzed erythrocytes under specific experimental conditions. Analysis indicated that feedback inhibition of γ-glutamate-cysteine ligase by glutathione had a limited effect on steady-state glutathione concentrations and was not sufficiently potent to return glutathione concentrations to normal levels in erythrocytes exposed to sustained increases in oxidative load.

Keywords: Cell/Blood, Enzymes, Enzymes/Oxidation-Reduction, Glutathione, Metabolism, Tissue/Organ Systems/Erythrocyte, Glutathione Metabolism, Mathematical Model

Introduction

Erythrocyte glutathione plays a vital role in mitigating the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS)4 encountered in the circulation (1) and produced by continuous oxidation of hemoglobin within the cytosol of the erythrocyte (2, 3). Reduced glutathione (GSH) reacts with superoxide reaction products, and via specific enzymes, it degrades hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxides (glutathione peroxidase, EC 1.11.1.9), and covalently modifies toxic xenobiotics and endogenous electrophiles (glutathione S-transferase, EC 2.5.1.18) to form water-soluble conjugates that are exported from the erythrocyte for excretion (4). In diseases associated with increased production of ROS that results in GSH depletion, restoration of the normal erythrocyte GSH concentration has been shown to have positive therapeutic effects (5, 6).

Experimental studies have provided a wealth of information on the individual reactions that together underlie the metabolic processes of the human erythrocyte (7–14). This information has been used to develop mathematical models to analyze and then predict the way in which the kinetic characteristics and control mechanisms for each reaction combine to regulate particular metabolic processes. Comprehensive models of erythrocyte glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate metabolism (12, 15–17), and the regulation of erythrocyte volume, pH, and transmembrane electrolyte distribution (18–20) have all been developed and used to provide insights into various biophysical and biochemical mechanisms and the regulation of erythrocyte function. Although models used to simulate certain aspects of glutathione function have been developed (21, 22), until now there have been no detailed and comprehensive models of glutathione metabolism based on realistic enzyme mechanisms and estimates of steady-state kinetic parameters.

An understanding of glutathione metabolism in the erythrocyte has been developed from information gained by investigating the kinetics of isolated enzymes. Such information allows the prediction that increased activity of the γ-glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL), increased substrate availability, and decreased GSH concentrations in the cell should all increase the rate of glutathione synthesis; but it is not possible to predict the magnitude of the increases or the interactions that produce a particular steady-state concentration without a comprehensive mathematical model (23). Therefore, our aim was to use available information on reaction mechanisms and steady-state kinetic parameter values to develop a mathematical model of glutathione metabolism that would allow a quantitative, predictive description of glutathione homeostasis in human erythrocytes. Unresolved issues to be investigated using the mathematical model included the following. (i) There are no known transport proteins in the erythrocyte membrane for dicarboxylic (net negatively charged) amino acids such as glutamate and aspartate. Extracellular glutamate at the concentration found in plasma (∼40 μm) enters the erythrocyte at a rate that is <5% of the normal rate of incorporation of glutamate into GSH in erythrocytes (24, 25). Hence, it is proposed that erythrocyte glutamate is provided via glutamine or by transamination of α-ketoglutarate from alanine (26); however, the relative contributions of these substrates as glutamate suppliers are yet to be established. (ii) Enzyme-catalyzed reactions of GSH with hydrogen peroxide and other ROS produce the oxidized form (GSSG). The GSSG concentration is maintained at <1% that of GSH by recycling of GSSG to GSH via glutathione reductase (GSSGR), and active (MgATP-dependent) export of GSSG from the erythrocyte (23). The relative contributions of reduction and export are not known, but the relationship between the rates of these two processes will have a significant effect on the steady-state concentration of GSH. (iii) To maintain constant concentrations of GSH within the erythrocyte at ∼2.3 mm, the rate of synthesis must equal the rate of export of glutathione conjugates and GSSG (27). The current hypothesis is that feedback inhibition of GCL by GSH maintains this balance, but the significance and extent of GSH inhibition within whole erythrocytes have not been determined (23).

Before using the mathematical model to investigate the regulation of glutathione concentration in erythrocytes in the circulation, it was necessary to estimate parameter values that were not adequately defined in the literature and then to verify that the output of the model was realistic by comparing model outcomes with experimental measurements made using whole erythrocytes under various buffer and metabolite conditions and with hemolyzed erythrocytes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Erythrocyte and Hemolyzate Preparation

The blood donors were between the ages of 20 and 55 years and in good health. Ethics approval was given by the Macquarie University Human Ethics Committee, and written consent was obtained from the donors before 12–24 ml of venous blood was collected from the cubital fossa into heparinized Vacutainers. The erythrocytes were separated, washed centrifugally (3000 × g for 10 min) three times at 4 °C in wash solution (80 mm KCl, 70 mm NaCl, 0.15 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES-Na, and 0.1 mm EDTA, pH 7.55), and then made up to 10% hematocrit (Ht) in incubation solution (80 mm KCl, 70 mm NaCl, 0.15 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES-Na, 10 mm glucose, 2 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 7.55). To partially deplete erythrocyte glutathione, 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) was added to give concentrations from 0.0 to 0.4 mm, and the erythrocyte suspension was incubated for 40 min at 37 °C. The cells were then washed three times, as described above, at room temperature in incubation solution with 5.0 mm N-acetylcysteine (NAC) before resuspension to Ht = 10% in incubation solution with 5.0 mm NAC and both glutamine and glycine at 1.0 mm. Over the 220 min taken for the whole erythrocyte experiments, there was marked oxidation of cysteine even in the presence of 2 mm DTT, so NAC was used as a more stable source of cysteine. Three milliliters of this suspension was incubated at 37 °C for 220 min with 100-μl samples removed at 20-min intervals. These samples were centrifuged, and 70 μl of supernatant was removed leaving the erythrocyte pellet. Two hundred μl of 6.55% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid was added to the pellet with rapid stirring, and the resulting deproteinized supernatant was used to measure erythrocyte total free glutathione (TFG, i.e., GSH + 2 × GSSG) concentration with an assay based on the 5–5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)/enzymatic recycling method (28, 29) as described previously (30). The rate of TFG synthesis was measured as the slope of the straight line fitted to the measured TFG concentration as it increased with time.

To prepare hemolyzates, whole blood was diluted to Ht = 10% in physiological saline that contained 10 mm glucose and then passed through a leukocyte-depleting filter (Sepacell R-500N, Asahi Medical Co.) before washing and TFG depletion as described above. The erythrocytes were then suspended in hemolyzate solution (110 mm KCl, 20 mm NaCl, 7.0 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES-Na, 40 mm nicotinamide, pH 7.20). Nicotinamide was added to competitively inhibit the membrane-linked NAD+/NADP+ glycohydrolase (31, 32). After centrifugation and removal of the supernatant, the packed erythrocytes were lyzed by sonification (S-450D Sonifier, Branson, Danbury, CT) using 3 × 30 s exposures at 45 watts and then diluted with an equal volume of hemolyzate solution plus 2.0 mm cysteine, glutamate, and glycine, 4.0 mm ATP, 4.0 mm DTT, and 20 mm glucose, pH 7.20, to give a hemoglobin concentration equivalent to Ht = 35%. Aliquots of 1.2 ml were incubated at 37 °C for 35 min in a Thermomixer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and 40-μl samples were taken at 5-min intervals for TFG measurement. Accurate rates of TFG production could be measured in 35 min in the hemolyzates because synthesis was ∼25 times more rapid than in whole erythrocytes. Cysteine rather than NAC was used in the lyzate experiments because over a period of 35 min and in the presence of DTT there was sufficient (unoxidized) cysteine to maintain a constant rate of TFG production.

Scope of Model

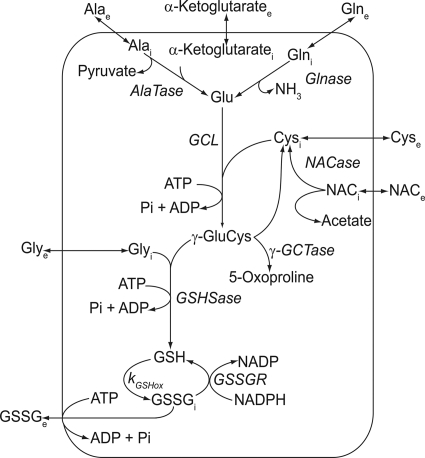

The model encompasses the core metabolic pathways of glutathione synthesis and the transport of the constitutive amino acids and related metabolites in the human erythrocyte (described in Fig. 1). The Cleland representation (33, 34) for each enzyme-catalyzed reaction is shown in Fig. 2, and the individual kinetic equations for the reactions and transport processes used in the model are given in the “Supplemental Information”. The system of differential equations constructed from these kinetic equations was solved numerically using Mathematica (version 7.01, Wolfram Research Inc., Champaign, IL).

FIGURE 1.

Scheme of the metabolic reactions involving glutathione in the human erythrocyte. The reaction scheme was the basis of the mathematical model. Glnase, glutaminase; AlaTase, alanine aminotransferase; NACase, NAC deacetylase; GSHSase, glutathione synthetase; γ-GCTase, γ-glutamylcyclotransferase. Membrane transport is via the amino acid transporters for alanine, glutamine, cysteine, glycine, the anion exchange protein for the majority of NAC transport, and the multidrug resistance-associated protein (MPR1) for the primary active export of GSSG.

FIGURE 2.

Representation of the mechanisms of the enzymatic reactions included in the model using Cleland's convention (33, 34). All of the abbreviations are as defined in Fig. 1. Reactions: A, GCL (13); B, glutathione synthetase (72); C, GSSGR (12); D, N-acetylcysteine deacetylase; E, alanine aminotransferase; F, glutaminase; G, γ-glutamylcyclotransferase (73); H, the reaction mechanism assumed for GSSGi active export. References are included when the mechanism for the particular enzyme has been reported previously. For the remaining enzymes, ordered sequential reactions were assumed.

Strategy of Model Development

Rate equations were derived for each of the enzyme-catalyzed reactions using the method of King and Altman as implemented in the algorithm of Cornish-Bowden programmed in Mathematica (35–37). When deriving rate equations, consideration was given to the reaction mechanism and to physiologically important inhibitors. From the rate equation for each enzyme, a nonlinear algebraic relationship between the steady-state kinetic parameters and the unitary rate constants was written (38, 39). Sets of unitary rate constants that were consistent with the steady-state parameters were determined in order to check the adequacy of each enzyme model. This process also assisted us in making a parameter choice when faced with a variety of literature values. In determining unitary rate constants, constraints were placed on their possible values; second-order rate constants were not allowed to exceed the “diffusion limit” of enzyme-catalyzed reactions of ∼109 m−1 s−1 (37). All first-order rate constants (not part of a dead-end step) (40), were made at least 2 orders of magnitude larger than the rate constants that characterized the interconversion of ternary complexes. The kinetic behavior of each enzyme or transporter was modeled in one of two ways: for most enzymes the steady-state rate equation was used, but for some reactions simple chemical kinetic equations were considered expedient, e.g. the oxidation of GSH.

Measurement of the Enzyme Kinetics of Glutaminase and Alanine Aminotransferase Using Proton NMR Spectroscopy

Leukocyte-free packed erythrocytes were lyzed by snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen before differing amounts of glutamine were added to form a series of substrate concentrations. For alanine and α-ketoglutarate, the initial concentration of one substrate was kept constant at 10.5 mm, whereas the concentration of the second substrate was varied. At each concentration, NMR spectra were acquired at 50-min intervals, with each measurement taking less than 4 min. For the remainder of the time, samples were incubated at 37 °C. The spectra were recorded using a Bruker (Karlsruhe, Germany) DRX-400 spectrometer with a 9.4-tesla vertical, wide bore magnet (Oxford Instruments, Oxford, United Kingdom) operating at 400.13 MHz for 1H observation. The rate of glutamine conversion to glutamate by glutaminase in the red blood cell lysate was followed by observing the decrease in the glutamine concentration over the 6-h NMR analysis. The rates of decrease of α-ketoglutarate and alanine were measured similarly. The data were used to calculate values of the Michaelis-Menten constants for glutaminase and alanine aminotransferase. The values of the constants are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the reported Km values of human erythrocyte enzymes with those included in the model

All values are in μmol(liter of erythrocyte water)−1 (i.e., μm) ± S.E. where available. The Km values for alanine aminotransferase and glutaminase were measured using 1H NMR spectroscopy to follow the reactions in concentrated hemolysates (results not shown). GSHSase, glutathione synthetase; γ-GCTase, γ-glutamylcyclotransferase; NACase, N-acetylcysteine deacetylase; ALATase, alanine aminotransferase; GLNase, glutaminase.

| Enzyme | Parameter | Reported values | Model values | Reference no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCL | KmCys | 333a | 300b | 314 | |

| KmGlu | 2,000a | 2,200b | 2,100 | ||

| KmATP | 400a | 430b | 415 | ||

| KiGSH | 2,300 | 2,300 | 9 | ||

| GSHSase | Kmγ-GluCys | 250a | 200b | 226 | |

| KmGly | 400a | 360b | 381 | ||

| KmATP | 400a | 500b | 451 | ||

| γ-GCTase | Kmγ-GluCys | 1,870 | 1,890 | 11 | |

| GSSGR | KmGSSG | 65 | 65 | 10 | |

| KmNADPH | 8.5 | 9.1 | |||

| NACase | KmNAC | 824 ± 88c | 252 | 45 | |

| ALATase | KmAla | 3,010 ± 2,450 | 3,022 | ||

| Kmα-Keto | 260 ± 80 | 258 | |||

| GLNase | KmGln | 118,000 | 114,000 | ||

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the reported Vmax values of human erythrocyte enzymes with those included in the model

All values are in mmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1 ± S.E. where available. GSGSase, glutathione synthetase; γ-GCTase, γ-glutamylcyclotransferase; NACase, N-acetylcysteine deacetylase; ALATase, alanine aminotransferase; GLNase, glutaminase.

| Enzyme | Reported values | Model values | Reference No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCL | 5.1 | 14.0 | 74 |

| 27.8–33.7 | 58 | ||

| 122 ± 6.3 | 75 | ||

| GSHSase | 5.1 | 17.5 | 11 |

| 4.50–9.91 | 58 | ||

| 20.4 ± 1.6 | 75 | ||

| γ-GCTase | 2.24 | 2.24 | 11 |

| GSSGR | 123 ± 22 | 132 | 12 |

| NACase | 0.110 ± 0.003 | 0.126 | 45 |

| ALATase | 0.917 ± 0.290a | 0.861 | |

| GLNase | 5.08a | 5.12 | 76 |

| 10.5 |

a Vmax values for alanine aminotransferase and glutaminase were measured using 1H NMR spectroscopy to follow the reactions in concentrated hemolysates (results not shown).

Refinement of Parameter Values

Experimentally measured steady-state kinetic and binding parameter values were used in the model (Tables 1–3). However, there was a wide range of reported values for the Vmax of GCL and glutathione synthetase, and to our knowledge, the Vmax for GSSG export has not been measured in erythrocytes. For these reactions, parameter values were estimated by a repeated process of simulation and comparison with experimental results until a value was obtained that enabled the model to simulate the behavior of the erythrocytes under both experimental and putative physiological conditions.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the reported parameter values for transport processes across the human erythrocyte membrane with those included in the model

Vmax units are in μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1, Km values in μm, and kd values in h−1 (± S.E. where available). The type of carrier protein is in the second column, and references are given in parentheses.

* AE denotes the erythrocyte anion exchange protein. To our knowledge, the transport of α-ketoglutarate across the erythrocyte membrane has not yet been characterized, and the Vmax for GSSG export has not been measured in whole erythrocytes.

Transport Processes

Cysteine, glycine, and alanine all enter the erythrocyte by the Na+-dependent ASC transporter, and glycine also crosses the erythrocyte membrane via the so called Gly transporter, which is Na+- and Cl−-dependent (41, 42). The main route for glutamine is the N-transport protein, which is also Na+-dependent (24). These transport processes were described by Michaelis-Menten equations with each amino acid having specific Vmax and Km values obtained from the literature (Table 3). To represent the ability of secondary active transport to concentrate amino acids inside erythrocytes (43), selected Vmax values were made lower for efflux than for influx, on the supposition that the low intracellular Na+ in erythrocytes would reduce the number of effective (Na+ bound) carriers (Table 3). Cysteine and glycine also cross the membrane via the high capacity, low affinity L transport system (44), which is not Na+-dependent and appears to contribute only a small proportion of amino acid transport (e.g., ∼16% of glycine) at the concentrations of amino acids found in the plasma (42, 43). However, L transporters would be expected to have a considerable effect at the higher concentrations of amino acids used experimentally. Because of their low affinity, the function of the L transporters could be accurately represented by first-order rate equations. Sixty percent of the influx of NAC into the erythrocyte is via the anion exchange protein (capnophorin; band 3), and as the rate of entry increases in proportion to the increase of extracellular NAC at concentrations less than 12 mm (45), NAC transport was also represented by a first-order rate equation. Alanine and α-ketoglutarate are included in the model as a potential source of intracellular glutamate. α-Ketoglutarate is present in the plasma at a concentration of ∼40 μm (46) and is known to enter the erythrocyte (26), but to our knowledge the concentration of α-ketoglutarate within the erythrocyte and the route and kinetics for its flux across the membrane have not been reported. As a divalent anion at plasma pH, α-ketoglutarate would require a carrier protein in order to enter the erythrocyte, so the transport process was represented in our model as a Michaelis-Menten system, and the Km and Vmax values were chosen so that a constant intracellular glutamate concentration was achieved when simulating the metabolism of erythrocytes in plasma.

GSSG Export

Oxidized glutathione is exported from the erythrocytes by two transport systems; each employs primary active transport using MgATP (48), but they differ in their affinity for GSSG. With a Km value of ∼6 mm, and considering that GSSG concentrations are normally <5.0 μm in the erythrocyte, the low affinity exporter would have minimal influence on transport flux under physiological conditions, and so it was not included in the model. The high affinity exporter has a Km value in the range of 23 to 100 μm (49, 50) (Table 3) and has been identified as the multidrug resistance-associated protein MPR1, which exports both GSSG and glutathione conjugates from the erythrocyte (51). The Vmax for MPR1 in the human erythrocyte has not been reported. A Vmax value of 2.14 mmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1, which is 60 times less than that of GSSGR, was considered a plausible estimate (Table 2). The reaction scheme for the export of GSSG is represented in Fig. 2H, and the corresponding rate equation is given online as “Supplemental Information”.

Representation of Oxidation of GSH

Within the erythrocyte, GSH acts via glutathione peroxidase to detoxify hydrogen peroxide, which arises from autoxidation of hemoglobin (52). It limits lipid peroxidation and is an essential co-reactant of glyoxalases I and II (53). In these and other physiological and pathological processes, GSH is oxidized to form GSSG. It was beyond the scope of the present model to include all of these individual reactions, so following the example of Schuster et al. (21), individual reactions leading to the oxidation of GSH were not specified. Instead the overall process was described by a non-enzymatic rate equation with a second-order rate constant (kGSHox) (see “Supplemental Information” online).

RESULTS

Experimentally Determined Kinetic Parameters for GCL and Glutathione Synthetase

The reported Vmax values for the synthetic enzymes GCL and glutathione synthetase, vary considerably in the literature (Table 2), so to estimate appropriate values for these two parameters, the rate of TFG synthesis was measured in hemolyzates that were incubated for 35 min with 1.0 mm cysteine, glycine, and glutamate, 10 mm glucose, and 2.0 mm ATP. Under these conditions the rate of TFG synthesis was 1.48 ± 0.10 mmol (liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1 (n = 4). With all other parameters set at the values given in Tables 1 and 2, Vmax values for GCL and glutathione synthetase of 14.0 and 17.5 mmol (liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1, respectively, gave a simulated rate of synthesis of TFG in the hemolyzate of 1.5 mmol (liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1.

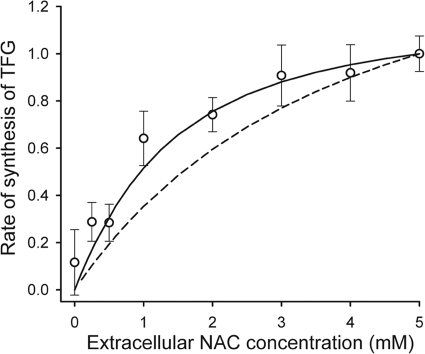

Experimentally Determined Kinetic Parameters for N-Acetylcysteine Deacetylase

Stable forms of cysteine such as NAC are routinely used to supply cysteine to cells when experiments with prolonged incubation periods are required (54). NAC is deacetylated in the cytoplasm by N-acetylcysteine deacetylase to yield cysteine (Fig. 2D), which then supports the synthesis of GSH (45). The dependence of the rate of TFG synthesis on the concentration of extracellular NAC was measured using erythrocytes depleted to ∼20% of their normal TFG concentration. GSH-depleted erythrocytes were used because export of GSSG from the cells and feedback inhibition by GSH are both minimal, and TFG concentrations could be measured more accurately against a low initial background concentration. On comparison of the measured rate of accumulation of TFG in erythrocytes with model predictions (Fig. 3), it became apparent that the previously reported value of Km = 824 ± 88 μm for N-acetylcysteine deacetylase (45) was too high to allow an acceptable fit between experimental and simulated results. Four mm extracellular buthionine sulfoximine, a potent, irreversible inhibitor of GCL (26), has been shown to reduce the rate of TFG synthesis in erythrocytes by ∼60% when NAC is the cysteine source (30). Incomplete inhibition by buthionine sulfoximine was partially due to the low permeability of erythrocyte membranes to this inhibitor, but it is also possible that as NAC (a strong reductant/antioxidant) accumulates in the erythrocyte it displaces bound GSH, which reportedly is present at around 10% of the total glutathione (55); this contributes to the increasing TFG concentration over the duration of the erythrocyte incubation experiments. A Km value of 252 μm was used in the model to account for the experimentally observed effects of NAC within the erythrocyte.

FIGURE 3.

Extracellular NAC as a substrate for glutathione synthesis. CDNB-depleted erythrocytes were washed three times at room temperature in incubation solution at pH 7.55 with 10 mm glucose, 1.0 mm glutamine and glycine, and varying concentrations of NAC. Erythrocytes were then suspended to give Ht = 10% in the same solution and incubated for 220 min at 37 °C. The TFG concentration was measured in samples taken at 20-min intervals; these values were used to estimate the linear rate of TFG synthesis ± S.E. Data are from one of three experiments, all of which gave similar results. The solid line represents the model output with NAC deacetylase, Km = 252 μm, and the dashed line represents Km = 911 μm. Simulated and experimental data are presented as a proportion of the maximum rate.

Verification of the Model Predictions Inhibition of TFG Production by GSH

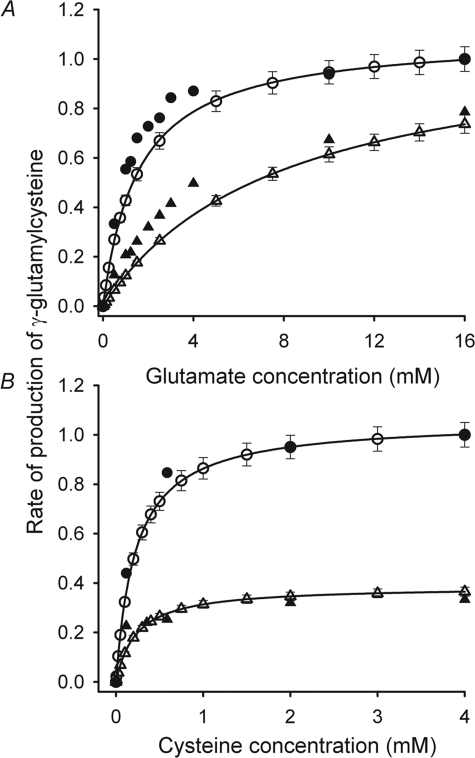

Feedback inhibition of GCL by GSH with Ki = 2.3 mm is usually considered an important factor in maintaining a constant concentration of GSH in erythrocytes within the circulation (23). To determine whether GSH inhibition was adequately represented in the model, the equation describing the reaction catalyzed by GCL (Fig. 2A and “Supplemental Information”) was solved for GSH concentrations of 0 and 10 mm over a range of glutamate and cysteine concentrations (Fig. 4). The substrate and GSH concentrations used for the simulation were the same as those used by Richman and Meister (9) when they measured feedback inhibition by GSH of γ-GluCys production using purified GCL from human erythrocytes. The rates of γ-GluCys synthesis calculated using the equation for the GCL-catalyzed reaction demonstrated the same order of magnitude and characteristics of GSH inhibition as the measured data presented by Richman and Meister (9).

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of GCL-catalyzed γ-GluCys production by GSH. Rates of γ-GluCys production are relative to the maximum rate in the absence of GSH. The open symbols denote the calculated values of the initial (0–10 s) rates of γ-GluCys production ±5% error in the presence 0 mm GSH (○) and 10 mm GSH (▵). The lines are best fits of the Michaelis-Menten equation to these data. See Fig. 1A and the “Supplemental Information” for the reaction scheme and steady-state kinetic expression for GCL. The solid symbols denote data from Richman and Meister (Ref. 9, Figs. 1 and 3 A therein) measured in the absence of GSH (●) and at 10 mm GSH (▲). The simulated data were calculated with the concentrations of ATP, cysteine, and glutamate used by Richman and Meister (9). A, competitive inhibition of glutamate binding by GSH. In these simulations cysteine concentration was set at 2.0 mm and ATP at 1.0 mm. B, inhibition of cysteine incorporation into γ-GluCys by GSH. Glutamate concentration was set at 2.0 mm and ATP at 1.0 mm.

Once the GCL equation was shown to accurately represent GSH feedback inhibition the model was used to predict the effect of initial GSH concentrations on the rate of TFG production in hemolyzed and whole erythrocytes. Washed erythrocytes were depleted of 90% of their GSH by incubating them for 40 min in 0.4 mm CDNB. The cells were then lyzed and the hemolyzate mixed with hemolyzate solution to give concentrations of glutamate and glycine of 1.0 mm and 2.0 mm ATP. Appropriate volumes of GSH stock solution of 100 mm were added to the hemolyzate to give final concentrations of 0.27–2.24 mm before the reaction was started by adding 1.0 mm cysteine. The rate of TFG synthesis showed a decline of 35% as the initial GSH concentrations were increased over this range (Fig. 5A). The prediction by the model of a 32% decline represented a close agreement between simulated and experimental results and confirmed the ability of the model to accurately describe feedback inhibition of TFG synthesis by GSH.

FIGURE 5.

GSH inhibition of TFG synthesis. The synthesis rates are relative to the maximum value. A, erythrocytes were depleted of GSH by incubation in 0.5 mm CDNB and then hemolyzed by sonification. GSH was added to the concentrations indicated, and the rate of TFG appearance was measured over a 35-min incubation period at 37 °C. The symbols denote the mean ± S.E. of the results from three separate experiments. For the hemolysate the rates of change of TFG predicted using the model are represented by the solid line, whereas the dashed line denotes model output when the value of KiGSH was increased by 10%. When KiGSH was decreased by 10%, the calculated values fell below but too close to the solid line to be distinguished. B, erythrocytes were exposed to a range of concentrations of CDNB (0.0 to 0.4 mm) that yielded TFG concentrations of 0.2 to 2.3 mm. All symbols and error bars denote mean ± S.E., and the open and closed symbols represent data from two separate experiments. The model calculations of the total rates of production of TFG (i.e., rate of increase of TFG within the erythrocyte plus the rate of export of TFG from the erythrocyte) under the conditions of the experiment fell along the solid line. Calculated values of the rate of change of TFG concentration in the erythrocytes are denoted by the dot-dashed and dashed lines, with the values of the second-order rate constant for GSH oxidation (kGSHox) at 0.0224 and 0.0467 mol−1 L h−1, respectively.

Whole erythrocytes were prepared with initial GSH concentrations ranging from the normal cytoplasmic concentration of ∼2.3 down to 0.2 mmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 by incubating erythrocytes with CDNB at concentrations from 0.0 to 0.4 mm. After washing, the erythrocytes were suspended in incubating solution with 5.0 mm NAC and both glutamine and glycine at 1.0 mm, and the rate of appearance of TFG in the erythrocytes over the next 220 min was measured. At the highest TFG concentrations large errors resulted from measuring small changes in TFG against a high initial background concentration. Nevertheless, it was clear from the results that the rate of accumulation of TFG in the erythrocytes declined by ∼80% as the initial erythrocyte TFG concentration was increased. When this experiment was simulated the predicted fall in the rate of TFG synthesis due to increased GSH feedback inhibition at higher initial concentration was less than 20% (Fig. 5B). Inspection of the model output showed that the remaining 60% of the measured decline was due to the increased rate of GSH oxidation at the higher concentrations and the resultant export of excess GSSG. With the value of kGSHox set at 0.0467 mol−1 L h−1, the model accurately predicted the effect of initial TFG concentration on the rate of production of TFG within the erythrocyte (Fig. 5B).

Erythrocytes in Plasma

Although erythrocyte GSH concentrations are quite variable between individuals, GSH concentrations have been shown to remain relatively constant for months in the erythrocytes of any particular healthy subject (56). Glutathione has a turnover time of 4–6 days (24.0–16.0 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1) (26, 57), and the rate of synthesis is limited by the supply of cysteine (5 μm in erythrocytes and 10 μm in the plasma). As GSH is not attacked by peptidases or degraded in any other way in the erythrocyte, steady-state concentrations are achieved by the balance between GSH synthesis and the export of GSSG and GSH-conjugates (27). This balance was thought (until this present study) to be maintained by feedback inhibition of GCL by GSH.

To model erythrocytes in plasma, concentrations of the amino acid substrates both inside and outside the cells were set at previously reported concentrations (Tables 4 and 5), and the plasma concentrations were held constant on the assumption that plasma amino acids are continually being replenished. As erythrocyte glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway maintain ATP and NADPH concentrations at relatively stable values, the concentrations of these two metabolites were also kept constant.

TABLE 4.

Concentrations of metabolites predicted by the model at the in vivo steady state

All concentrations are μmol(liter of erythrocyte water)−1 (i.e., μm) ± S.E. where available. There is no equation for efflux of intracellular 5-oxoproline (5-Oxopi) in the model, so in the simulation it continues to accumulate within the erythrocyte over the 24-h period. The plasma concentration of 5-oxoproline has been measured as 14 μm (83). We were unable to find previously measured values for erythrocyte concentrations of α-ketoglutarate (α-Keto) or 5-oxoproline.

| Metabolite | Reported values | Predicted by model at steady state | Reference No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSHi | 3200 ± 0.5 | 3223 | 12 |

| 2910 ± 200 | 30 | ||

| GSSGi | 0.30 ± 0.103 | 0.452 | 55 |

| Cysi | 5 | 4.99 | 78 |

| 4.8 ± 1.2 | 77 | ||

| 5.79 ± 0.21 | 55 | ||

| Glni | 248 ± 51 | 460 | 77 |

| 758 ± 15 | 81 | ||

| Alai | 294 ± 19 | 280 | 82 |

| 419 ± 16 | 81 | ||

| α-Ketoi | 4.66 | ||

| Glui | 385 ± 72 | 457 | 77 |

| 446 ± 17 | 81 | ||

| Glyi | 372 ± 76 | 342 | 77 |

| 544 ± 21 | 81 | ||

| γ-GluCysi | <2.0a | 1.07 | 59 |

| 5-Oxopi | 42 |

a Free γ-GluCysi.

TABLE 5.

Values of external parameters required to produce the set of in vivo steady-state concentrations

Concentrations of these metabolites were held constant during the simulation of the metabolic steady state of erythrocytes in plasma. All concentrations are μm ± S.E. where available. α-Keto denotes α-ketoglutarate.

| External parametera | Reported values | Values in model | Reference No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyse | 10 | 10 | 78 |

| 11.3 ± 2.9 | 84 | ||

| Glne | 517 ± 70 | 586 | 77 |

| 655 ± 16 | 81 | ||

| Alae | 316 ± 16 | 300 | 81 |

| 349 ± 24 | 82, 85 | ||

| α-Ketoe | 40 ± 30 | 37.4 | 46 |

| Glye | 285 ± 18 | 267 | 77 |

| 248 ± 13 | 81 | ||

| GSSGe | 0.10 | 0.10 | 86 |

| 0.05 ± 0.05 | 84 | ||

| ATP | 1.42–3.57 | 1950 | 87 |

| 2.04 ± 0.14 | 47 | ||

| NADPH | 56 ± 5.6 | 65 | 87 |

a Subscript e indicates that the solute is extracellular (plasma).

When the plasma cysteine concentrations were set to 10 μm, the steady-state cysteine concentration within the erythrocyte was ∼5.0 μm and the calculated rate of TFG synthesis was 20.5 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1. To obtain a constant erythrocyte TFG concentration, the second-order rate constant for oxidation of GSH was adjusted so that the rate of export of GSSG × 2 equaled the rate of TFG synthesis (kGSHox = 0.0467 mol−1 L h−1) (Fig. 6B). When the model was run to simulate a period of 24 h, intracellular concentrations of glutamine, alanine, glutamate, cysteine, and glycine reached steady-state concentrations close to those reported for normal erythrocytes, and the estimated rate of 5-oxoproline production was 1.2 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)h−1 (Fig. 6A and Table 4). The simulation showed γ-GluCys at a steady-state concentration of 1.08 μm. Although erythrocyte concentrations of γ-GluCys of 10–47 μm have been measured following the reduction of disulfide bonds by >10 mm DDT (58, 59), the concentration of free γ-GluCys in erythrocytes is thought to be <2.0 μm (59).

FIGURE 6.

Modeled attainment of steady-state concentrations of substrates, intermediates, and products of glutathione metabolism in erythrocytes under approximated in vivo conditions. A, concentrations of substrates and intermediates: ●, cysteine; ▵, glutamine; ○, glutamate; □, glycine; ▼, γ-GluCys. B, concentrations of products: ▵, erythrocyte TFG (i.e., [GSHi] + 2 × [GSSGi]); □, total synthesized glutathione (i.e., [GSHi] + 2 × ([GSSGi] + [GSSGe])); ○, extracellular TFG (i.e., 2 × [GSSGe]); (●), 5-oxoproline. The concentrations of extracellular TFG (2 × [GSSGe]) were expressed in mmol(liter of erythrocyte water)−1 for direct comparison with other values in the figure.

Predicted Changes Produced by Perturbation of the Steady State

When the TFG concentration in the model was increased to 120% of the normal steady-state value, there was an initial decrease in the rate of TFG synthesis from 20.5 to 19.9 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1, primarily because of feedback inhibition of GCL by GSH. Simultaneously the rate of export of GSSG × 2 increased from 20.5 to 27.1 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1 because of the increased rate of oxidation at the higher concentration of GSH. Now that the rate of export of TFG exceeded the rate of synthesis, there was a decline of the erythrocyte TFG concentration until, by ∼10 days, this concentration had returned to its initial value (Fig. 7A). When the erythrocyte TFG concentration was decreased, the rate of TFG export also decreased so that synthesized TFG accumulated until the initial concentration was attained (Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Perturbations of steady-state conditions in erythrocytes under approximated in vivo conditions. The connected data points indicate the results of model calculations of erythrocyte TFG concentrations. A, symbols denote the following: ●, at the steady state; ▵, after an increase; □, after a decrease of the initial intracellular [TFG] by 20%. B, erythrocyte [TFG] values at the steady state are indicated by closed circles (●). The remainder of the symbols denote erythrocyte [TFG] values resulting from a sustained increase in the value of the unitary rate constant for oxidation of GSH (kGSHox) by 20%: ▲, no other change; (◇, increase in GCL Vmax by 50%; ▵, increase in extracellular cysteine concentration by 50%; □, increase in the Vmax for glutamine influx by 10%; ○, increase in the Vmax of GSSGR by 20%. The slow rate of increase seen in all the time courses was deduced to be due to a slight difference in the rate of TFG synthesis (20.495 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1) and export (20.492 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1) at the quasi steady state. Running the model for a period of 12 simulated days emphasized the effects of this difference.

When the rate constant for oxidation of GSH (kGSHox) was increased to ∼120% of the normal value (i.e., from 0.0467 to 0.0560 mol−1 L h−1), the rate of oxidation of GSH and export of GSSG were increased, and as a result erythrocyte TFG concentrations declined from the initial value of 2.29–2.13 mmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1. Calculations using the model showed that over a period of 12 days at this high oxidative load there was no return to the normal erythrocyte TFG concentration, despite the expected reduction in feedback inhibition by GSH (Fig. 7B).

DISCUSSION

Parameter Estimates

The new kinetic model is intended to be a realistic representation of glutathione metabolism within intact human erythrocytes, and for this purpose the model included experimentally determined values of binding and kinetic parameters for the enzymes and membrane transport proteins involved (Fig. 1 and Tables 1–3). The Vmax values for GCL and glutathione synthetase were estimated and then amended until the model accurately predicted the measured rate of GSH synthesis in hemolysates. The measured maximum rate of TFG synthesis in the hemolyzate (1.48 ± 0.10 mmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1) was reproduced by the model when Vmax values of 14.0 and 17.5 mmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1) were used for GCL and glutathione synthetase, respectively. These estimated Vmax values fall within the range of previously measured values (Table 2). With these values, the model predicted a steady-state rate of TFG synthesis for erythrocytes in plasma of 20.6 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1 giving a turnover time for erythrocyte TFG of ∼5 days; previous estimates had been from 4 to 6 days (26, 57). Simulations of experiments in which TFG was depleted in erythrocytes supplied with 5.0 mm NAC as the cysteine source gave a rate of TFG formation of 72.0 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1, which was the same as the experimentally estimated value reported previously (30).

Sensitivity Analysis

To determine the effect of changes in parameter values on the model output, Km and Vmax values for all enzymes and transport processes (Fig. 1) were varied by ± 10% before calculating the rate of TFG production for erythrocytes in plasma (Table S1). For the majority of the parameters a 10% change in value altered the calculated rate of TFG production by less than 0.5%. The modeled outcome was more sensitive to changes of ±10% in the following parameters: (i) for GCL, KmCys, KmGlu, KiGSH, and Vmax with resultant changes in the rate of TFG production of approximately ±3.5% for each parameter (the effect of ± 10% changes in the value of KiGSH is presented graphically in Fig. 5); (ii) for membrane transport of cysteine, Km, Vmax, and Kd (±3.3–8.3%); (iii) for membrane transport of glutamine, Km (±4.3%); (iv) for glutaminase, Km and Vmax (±2.0%). TFG synthesis by erythrocytes in the circulation is particularly dependent upon the supply of cysteine and glutamate and the activity of GCL. The sensitivity analysis showed clearly that this dependence had been captured by the model.

Although changes in the values of the parameters for GSSGR and GSSG transport had little effect on the total rate of TFG synthesis (Table S1), they had a marked impact on the rate of export of GSSG. For GSSG export a 10% increase/decrease in the values of KmGSSGi and the Vmax produced changes of −22%/+ 10% and + 7.4%/−7.8%, respectively. Corresponding changes for KmGSSG and the Vmax for GSSGR were all approximately ±8.0%. These differences in the rate of GSSG export would be reflected in the concentrations of TFG inside the erythrocytes.

GSH Inhibition of TFG Accumulation within Erythrocytes

When initial TFG concentrations were increase from 0.27 to 2.24 mm in hemolyzed erythrocytes, the rate of TFG production fell by ∼35% (Fig. 5A) confirming previous experimental results (60). The model predicted a comparable decline (32%), and in the hemolyzates the effect of the initial GSH concentrations was solely due to feedback inhibition onto GCL. For intact erythrocytes the measured rate of TFG appearance within the cells decreased by ∼80% as the initial TFG concentrations were increased from 0.2 to 2.3 mmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 (Fig. 5B). When model simulations that accurately represented this experimental result were analyzed, it became apparent that GSSG export accounted for ∼75% of the decline in the rate of erythrocyte TFG accumulation with increasing initial GSH concentration, whereas feedback inhibition by GSH contributed ∼25% of the overall effect.

Oxidation of GSH

With a value of kGSHox of 0.0467 mol−1 L h−1 the model provided an accurate description of the inverse relationship between the initial GSH concentration and the rate of TFG accumulation in erythrocytes (Fig. 5B), and at this value of kGSHox the rate of export of GSSG from erythrocytes in plasma (10.3 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1) agreed with previous estimates (11.4 μmol(liter of erythrocytes)−1 h−1) (26). In glucose-free erythrocytes exposed to O2 at ∼7 times the partial pressure in arterial blood, the oxidation rate of GSH has a reported value of 0.80 mmol l−1 h−1 at 3.2 mm GSH (12). Although the high partial pressure of O2 would accelerate the conversion of GSH to GSSG in this experiment, an increase in the basal level of oxidation would also be expected in erythrocytes exposed to peroxides that continually enter the circulation. Using the value of the rate constant for GSH oxidation included in the model (kGSHox = 0.0467 mol−1 L h−1), the calculated rate of oxidation at 1.1 mmol l−1 h−1 was not dissimilar from the previously measured value (12).

Perturbations of the Steady State

Once the model was shown to represent glutathione metabolism of erythrocytes in plasma (Table 4 and Fig. 6) accurately, it was used to simulate the response of these cells to a 20% change in the GSH concentration (Fig. 7A). When the TFG concentration was increased, GSSG export initially exceeded the rate of glutathione synthesis, whereas at low GSH concentrations the synthesis of GSH proceeded at a greater rate than export. As a result the system returned to the normal steady state over a period of several days (Fig. 7A). Feedback inhibition of GCL by GSH appeared to contribute little to this process, because elimination of this inhibition, by increasing the value of KiGSH from 2.3 mm to 2.3 m did not noticeably affect the time course of the return to the steady-state concentration.

When the model was used to simulate a persistent increase in the rate of GSH oxidation (i.e., increasing kGSHox by 20%), a mismatch between the increased rate of export of GSSG and the rate of GSH synthesis caused an initial decline in GSH until a new steady state was attained at erythrocyte TFG concentrations ∼10% less than TFG concentration predicted for erythrocytes under normal plasma conditions, and the decreased TFG concentration was still apparent after a simulated period of 12 days (Fig. 7B). In this situation the only control mechanism included in the model that could stimulate TFG synthesis to counteract the increased export was the reduced effect of feedback inhibition of GSH on GCL at the lower erythrocyte TFG concentration. The model simulations shown in Fig. 7B indicate that this mechanism was not sufficiently potent to return erythrocyte concentrations of TFG toward “normal” in the face of a significant increase in the rate of oxidation of GSH and the consequent increased rate of export of GSSG. This outcome is consistent with predictions made using a model of glutathione metabolism in the liver, which showed a negligible effect of GSH inhibition when cysteine supply was limited and in which hepatocyte GSH concentrations were less than 6 mm (61).

The predicted failure of erythrocytes to re-establish normal glutathione concentrations after a sustained increase in the oxidative load has been seen in vivo (48). As replenishing GSH appears to limit progressive cell and tissue damage associated with oxidative stress (5, 6, 63), the model was used to investigate processes that could in principle maintain constant GSH concentrations in erythrocytes during chronic exposure to increased levels of ROS.

One therapeutic approach has been to increase cysteine availability by oral administration of NAC. Ingestion of NAC in quantities that can double the plasma concentrations of cysteine by a reduction of cystine (64, 65) appears to be well tolerated. The model predicted that a 50% increase in the extracellular cysteine concentration could substantially mitigate the effect of the increased rate of oxidation (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, in sickle cell anemia, erythrocytes that are constantly subjected to oxidative stress due to rapid autoxidation of sickle hemoglobin (66) have a significant increase in the Vmax and a decrease in Km for Na+-dependent, secondary active transport of glutamine and the increased rate of entry of glutamine results in accumulation of glutamate (67). When the Vmax value for glutamine influx was increased by 10%, model simulations showed an increase in cell glutamate concentration (to 560 μm), and erythrocyte TFG concentrations returned to almost normal values within 10 days of the initiation of the 20% increase in kGSHox R (Fig. 7B). This is not unexpected, as glutamate concentrations normally within the erythrocyte (∼450 μm) are well below the Km for GCL (∼2.0 mm; Table 1). Oral glutamine therapy and ingestion of NAC have been suggested as part of the therapeutic regime for patients with sickle cell anemia (68), and the current model predictions provide evidence supporting the efficacy of this treatment.

The redox state of cells is known to regulate enzymatic activity (69). In particular, 4-hydroxynonal, an end-product of lipid peroxidation that accumulates in the plasma during periods of oxidative stress, has been shown to up-regulate the expression of the catalytic subunit of GCL in bronchial epithelial cells (70). Therefore it is not impossible that under conditions of chronic oxidative stress, gene expression of one or both of the subunits of GCL could be induced during erythropoiesis. However, calculations with the current model demonstrated that an increase of considerably more than 50% in the Vmax of GCL would be required to alleviate the oxidation-induced decline in total GSH (Fig. 7B).

The critical role of NADPH-dependent GSSGR function in maintaining GSH levels under oxidative stress was identified by investigations of erythrocytes deficient in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. In normal erythrocytes NAPDH availability is not thought to limit the response of GSH to regular oxidative challenges encountered in the circulation (71). In the current model, NADPH was set at a constant concentration (65 μm) sufficient to saturate GSSGR (KmNADPH = 9.1 μm; Table 1). The importance of GSSGR in maintaining a normal TFG concentration within erythrocytes was demonstrated by the model prediction that an increase in the Vmax of GSSGR by 20% returned TFG levels to normal during prolonged exposure to a moderate increase in the rate of oxidation of GSH (Fig. 7B).

Conclusions

A detailed, comprehensive model of the synthesis of GSH and export of its oxidized form, GSSG, from the human erythrocyte has been presented. By reiterated comparison of experimental and simulated results, the values of various kinetic parameters of the model were refined to yield close conformity between the model simulations and experimental data. The model was used to reproduce a normal set of in vivo steady-state metabolite concentrations that matched well with the available experimental data for erythrocytes in plasma (i.e., whole blood). A novel finding to emerge from the present work is that GSH feedback inhibition on GCL does not play the previously posited dominant role in influencing the normal steady-state concentrations of GSH in human erythrocytes. Simulations using the model identified the reactions that have particular scope to alter GSH concentrations in erythrocytes in response to changes in oxidative load. In several chronic diseases characterized by increased production of ROS, the average concentrations of TFG in erythrocytes are less than for healthy individuals, and the low GSH concentration is a prognosticator of a poor disease outcome. Further elucidation of the control of GSH metabolism in human erythrocytes is needed if therapeutic protocols to stimulate GSH synthesis in response to oxidative stress are to be developed.

Supplementary Material

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains “Supplemental Information” and supplemental Table S1.

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- CDNB

- 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- GCL

- γ-glutamate-cysteine ligase

- GSSGR

- glutathione reductase

- γ-GluCys

- γ-glutamylcysteine

- Ht

- hematocrit

- kGSHox

- unitary rate constant for the oxidation of GSH

- NAC

- N-acetylcysteine

- TFG

- total free glutathione (i.e., 2 × GSSG + GSH).

REFERENCES

- 1.Mak I. T., Stafford R., Weglicki W. B. (1994) Am. J. Physiol. 267, C1366–C1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh H. S., Jaffe E. R. (1975) in The Red Blood Cell (Surgenor D. M. ed) 2nd Ed., Academic Press, New York, 799–824 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rice-Evans C. (1990) in Erythroid Cells (Harris J. R. ed), pp. 429–451, Plenum Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. (2004) Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 3rd Ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pace B. S., Shartava A., Pack-Mabien A., Mulekar M., Ardia A., Goodman S. R. (2003) Am. J. Hematol. 73, 26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foschino Barbaro M. P., Serviddio G., Resta O., Rollo T., Tamborra R., Elisiana Carpagnano G., Vendemiale G., Altomare E. (2005) Free Radic. Res. 39, 1111–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minnich V., Smith M. B., Brauner M. J., Majerus P. W. (1971) J. Clin. Invest. 50, 507–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majerus P. W., Brauner M. J., Smith M. B., Minnich V. (1971) J. Clin. Invest. 50, 1637–1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richman P. G., Meister A. (1975) J. Biol. Chem. 250, 1422–1426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worthington D. J., Rosemeyer M. A. (1976) Eur. J. Biochem. 67, 231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith J. E., Moore K., Board P. G. (1980) Enzyme 25, 236–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorburn D. R., Kuchel P. W. (1985) Eur. J. Biochem. 150, 371–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith O. W., Mulcahy R. T. (1999) Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 73, 209–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo T., Kawakami Y., Taniguchi N., Beutler E. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 7373–7377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzhütter H. G., Jacobasch G., Bisdorff A. (1985) Eur. J. Biochem. 149, 101–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi A., Palsson B. O. (1989) J. Theor. Biol. 141, 515–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulquiney P. J., Kuchel P. W. (1999) Biochem. J. 342, 597–604 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lew V. L., Bookchin R. M. (1986) J. Membr. Biol. 92, 57–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raftos J. E., Bulliman B. T., Kuchel P. W. (1990) J. Gen. Physiol. 95, 1183–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raftos J. E., Chapman B. E., Kuchel P. W., Lovric V. A., Stewart I. M. (1986) Haematologia 19, 251–268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuster R., Holzhütter H. G., Jacobasch G. (1988) Biosystems 22, 19–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakayama Y., Kinoshita A., Tomita M. (2005) Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith O. W. (1999) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 27, 922–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellory J. C., Preston R. L., Osotimehin B., Young J. D. (1983) Biomed. Biochim. Acta 42, S48–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young J. D., Jones S. E., Ellory J. C. (1980) Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B Biol. Sci. 209, 355–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith O. W. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 4900–4904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunn G., Dale G. L., Beutler E. (1979) Blood 54, 238–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owens C., Belcher R. (1965) J. Biol. Chem. 94, 705–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tietze F. (1969) Anal. Biochem. 27, 502–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raftos J. E., Dwarte T. M., Luty A., Willcock C. J. (2006) Redox Rep. 11, 9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuchel P. W., Jarvie P. E., Conyers R. A. (1982) Biochem. Med. 27, 95–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King G. F., Kuchel P. W. (1985) Biochem. J. 227, 833–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleland W. W. (1963) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 67, 104–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cleland W. W. (1967) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 36, 77–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King E. L., Altman C. (1956) J. Phys. Chem. 60, 1375–1378 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornish-Bowden A. (1977) Biochem. J. 165, 55–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulquiney P. J., Kuchel P. W. (2003) Modelling Metabolism with Mathematica, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhoads D. G., Lowenstein J. M. (1968) J. Biol. Chem. 243, 3963–3972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulquiney P. J., Kuchel P. W. (1999) Biochem. J. 342, 581–596 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapoport S. M. (1988) in The Roots of Modern Biochemistry: Fritz Lipman's Struggle and Its Consequences (Kleinkauf H., von Dohren H., Jaenicke L. eds), pp. 157–164, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellory J. C., Swietach P., Gibson J. S. (2003) in Red Cell Membrane Transport in Health and Disease (Bernhardt I., Ellory J. C. eds), pp. 303–316, Springer-Verlag, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tunnicliff G. (2003) J. Biomed. Sci. 10, 30–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stein W. D. (1990) Channels, Carriers, and Pumps, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, London [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verrey F. (2003) Pflügers Arch. 445, 529–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raftos J. E., Whillier S., Chapman B. E., Kuchel P. W. (2007) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 1698–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forni L. G., McKinnon W., Lord G. A., Treacher D. F., Peron J. M., Hilton P. J. (2005) Crit. Care 9, R591–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lovric V. A., Schuller M., Bryant J., Raftos J., Kronenberg H. K. (1981) Med. J. Aust. 1, 635–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srivastava S. K., Beutler E. (1969) J. Biol. Chem. 244, 9–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kondo T., Dale G. L., Beutler E. (1980) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77, 6359–6362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akerboom T. P., Bartosz G., Sies H. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1103, 115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klokouzas A., Barrand M. A., Hladky S. B. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 6569–6577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaffe E. R. (1981) in The Function of Red Blood Cells: Erythrocyte Pathobiology (Brewer G. J. ed), pp. 133–151, 1st Ed., Alan R. Liss, New York [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rae C., Berners-Price S. J., Bulliman B. T., Kuchel P. W. (1990) Eur. J. Biochem. 193, 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phelps D. T., Deneke S. M., Daley D. L., Fanburg B. L. (1992) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 7, 293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mills B. J., Lang C. A. (1996) Biochem. Pharmacol. 52, 401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richie J. P., Jr., Abraham P., Leutzinger Y. (1996) Clin. Chem. 42, 1100–1105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dimant E., Landsberg E., London I. M. (1955) J. Biol. Chem. 213, 769–776 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ristoff E., Augustson C., Geissler J., de Rijk T., Carlsson K., Luo J. L., Andersson K., Weening R. S., van Zwieten R., Larsson A., Roos D. (2000) Blood 95, 2193–2196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hagenfeldt L., Arvidsson A., Larsson A. (1978) Clin. Chim. Acta 85, 167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jackson R. C. (1969) Biochem. J. 111, 309–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reed M. C., Thomas R. L., Pavisic J., James S. J., Ulrich C. M., Nijhout H. F. (2008) Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 5, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagner T. C., Scott M. D. (1994) Anal. Biochem. 222, 417–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thornalley P. J., McLellan A. C., Lo T. W., Benn J., Sönksen P. H. (1996) Clin. Sci. 91, 575–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whillier S., Raftos J. E., Chapman B., Kuchel P. W. (2009) Redox Rep. 14, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burgunder J. M., Varriale A., Lauterburg B. H. (1989) Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 36, 127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hebbel R. P., Morgan W. T., Eaton J. W., Hedlund B. E. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 237–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niihara Y., Zerez C. R., Akiyama D. S., Tanaka K. R. (1997) J. Lab. Clin. Med. 130, 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niihara Y., Zerez C. R., Akiyama D. S., Tanaka K. R. (1998) Am. J. Hematol. 58, 117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu S. C. (2009) Mol. Aspects Med. 30, 42–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang H., Shih A., Rinna A., Forman H. J. (2009) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 481, 110–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salvador A., Savageau M. A. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14463–14468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meister A., Anderson M. E. (1983) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 52, 711–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oakley A. J., Yamada T., Liu D., Coggan M., Clark A. G., Board P. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22031–22042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Beutler E., Dale G. L. (1989) in Glutathione: Chemical, Biochemical and Medical Aspects (Dolphin D., Poulson R., Avramovic O. eds), pp. 291–395, Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu H., Harrell L. E., Shenvi S., Hagen T., Liu R. M. (2005) J. Neurosci. Res. 79, 861–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rapoport S. (1961) Folia Haematol. Int. Mag. Klin. Morphol. Blutforsch. 78, 364–381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kiessling K., Roberts N., Gibson J., Ellory J. (2000) Hematol. J. 1, 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bannai S. (1984) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 779, 289–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tunnicliff G. (1994) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Comp. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 108, 471–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Winter C. G., Christensen H. N. (1964) J. Biol. Chem. 239, 872–878 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Divino Filho J. C., Bárány P., Stehle P., Fürst P., Bergström J. (1997) Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 12, 2339–2348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aguiló A., Castaño E., Tauler P., Guix M. P., Serra N., Pons A. (2000) J. Nutr. Biochem. 11, 81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Friesen R. W., Novak E. M., Hasman D., Innis S. M. (2007) J. Nutr. 137, 2641–2646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnson J. M., Strobel F. H., Reed M., Pohl J., Jones D. P. (2008) Clin. Chim. Acta 396, 43–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Van Thien H., Ackermans M. T., Weverling G. J., Thanh Chien V. O., Endert E., Kager P. A., Sauerwein H. P. (2004) Clin. Nutr. 23, 59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Blanco R. A., Ziegler T. R., Carlson B. A., Cheng P. Y., Park Y., Cotsonis G. A., Accardi C. J., Jones D. P. (2007) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86, 1016–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Grimes A. J. (1980) Human Red Cell Metabolism, Blackwell Scientific Publications, London [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.