Abstract

A straightforward method for the synthesis of γ-halo-substituted ketones formed via the CAN-initiated oxidative addition of halides to 1-substituted cyclobutanols has been developed. This method has short reaction times, and provides access to a range of bromo and iodo γ-substituted ketones in good to excellent yields.

Keywords: CAN, Cyclobutanol, γ-Substituted ketone, Oxidative coupling

1. Introduction

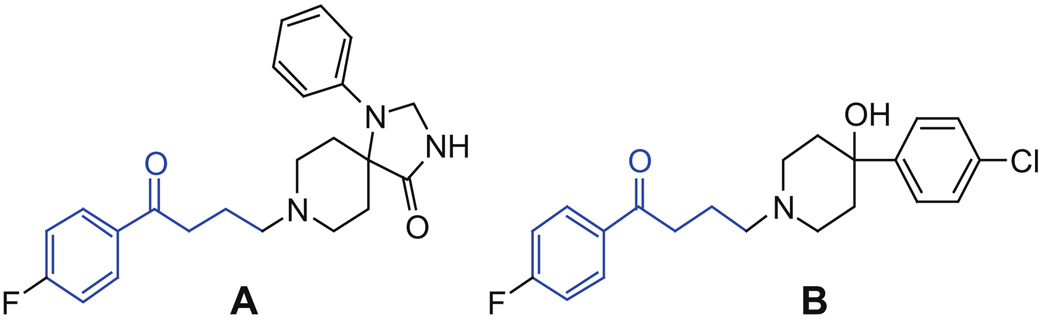

Ketones with γ-halo substitutions are useful starting materials for the synthesis of biologically active compounds. The γ-substituted ketone moieties in neurological agents such as spiperidol and haldol (Fig. 1) are incorporated by utilizing γ-chloro ketones in particular as starting materials.1,2 Ketones with γ-chloro substitutions have been used also in the synthesis of antagonists for the melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH1) receptor.3 The ability to efficiently generate starting materials containing γ-halo ketone subunits has the potential to greatly impact the synthesis of novel, pharmaceutically active compounds.

Figure 1.

Structures of spiperidol (A) and haldol (B).

Although γ-substituted ketone functionalities have been incorporated into molecules traditionally through γ-chloro ketones, the use of other γ-halo ketones such as γ-iodo or bromo ketones may be synthetically beneficial since these halides are better leaving groups than chloride. However, the synthetic approaches to structurally diverse γ-halo ketones have been limited to only a handful of synthetic routes for γ-chloro and a few γ-bromo ketones. While there is no general method for producing γ-chloro ketones, both aryl- and aliphatic γ-chloro ketones can be synthesized via Friedel–Crafts or Grignard reactions.4 Typically, γ-iodo and bromo ketones are produced by refluxing γ-chloro ketones in the presence of either iodide or bromide. While useful, these conversions typically require long reaction times and superstoichiometric amounts of the desired halide.5 The development of a general and direct route to γ-iodo and bromo ketones would be of interest.

Cerium(IV) reagents, namely cerium(IV) ammonium nitrate (CAN), have been used extensively by organic chemists as single-electron oxidants.6 CAN has proven to be a cost-effective, versatile reagent that is capable of mediating novel carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bonds.7,8 Previous research from our group has shown that β-substituted ketones are accessible through the use of CAN.9 By selectively oxidizing an inorganic anion in the presence of a 1-substituted cyclopropanol with CAN, the generated inorganic radical was added to the cyclopropanol resulting in ring opening. After a subsequent oxidation of the radical intermediate and deprotonation, β-substituted ketones were produced in very good to excellent yields. In addition to quick reaction times, these reactions worked for both 1-aryl- and 1-alkyl-cyclopropanols as well as a variety of inorganic anions. Based on this precedent, we sought to examine whether this method could be extended to 1-substituted cyclobutanols thereby providing access to γ-substituted ketones. The results of these studies are presented herein.

2. Results and discussion

To examine the breadth of γ-substituted compounds that could be achieved from the oxidation of inorganic anions with CAN, both 1-aryl- and 1-alkyl-cyclobutanols were synthesized. These starting materials were generated via the reaction of cyclobutanone, or 2-ethyl-cyclobutanone for 1f, with a variety of Grignard reagents.10,11 The reactions produced acceptable product yields, and were purified by nonchromatographic methods. The 1-phenyl-cyclobutanol (1a) was purified by recrystallization from n-pentane at reduced temperature (−20 °C). Substrates 1c,f were synthesized quantitatively and required no additional purification. For all other starting materials (1b,d and e), short-path distillations at reduced pressure were used to purify gram quantities of the desired compounds.

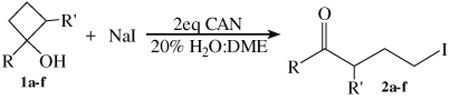

In an initial study, sodium iodide (NaI) was oxidized with CAN in the presence of substrate 1a using reaction conditions [20% H2O/acetonitrile (MeCN)] previously employed for the oxidative addition of inorganic anions to 1-substituted cyclopropanols.9 While γ-iodo ketone 2a was generated as the major product, multiple side products were observed by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. Since changes in solvent often times can impact the chemoselectivity of reactions initiated by CAN, several solvent systems were examined to determine if the reaction yield could be improved.12 Among the solvent systems screened, 1H NMR analysis showed that 20% H2O/1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME) generated 2a almost exclusively. As a result, this solvent system was utilized for the other unsubstituted substrates. As shown in Table 1, γ-iodo ketones 2a–e were obtained in good to very good isolated yields for both 1-aryl- and 1-alkyl-cyclobutanols.

Table 1.

Synthesis of γ-iodo ketones13

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Product | R | R′ | Yielda (%) |

| 1a | 2a | Ph | H | 79 |

| 1b | 2b | p-CH3O-Ph | H | 67 |

| 1c | 2c | p-F-Ph | H | 79 |

| 1d | 2d | Cyclohexyl | H | 64 |

| 1e | 2e | n-hexyl | H | 80 |

| 1f | 2fb | p-F-Ph | Et | 80 |

Isolated yield.

Conditions: Reaction run at 0 °C in 20% H2O/MeCN.

To examine the regioselectivity of the ring opening, 1f was subjected to the same reaction conditions. While product 2f was formed exclusively, the reaction mixture contained unreacted starting material. After scanning a series of solvent and reaction conditions, optimal yields of 2f were obtained in 20% H2O/MeCN at 0 °C.

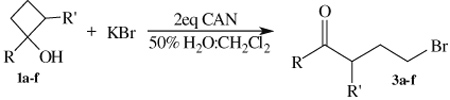

Next, the synthesis of γ-bromo ketones was examined. In previous work on the synthesis of β-substituted ketones, the oxidation of bromide anion by CAN was shown to be relatively slow compared to the oxidation of iodide. In order to avoid the possibility of direct oxidation of 1a–f by CAN, these brominations were performed in a two-phase solvent system of 50% H2O/methylene chloride (CH2Cl2).14 In an initial experiment, the bromination of 1a using potassium bromide (KBr) as the bromide anion source provided 3a in an 87% isolated yield (Table 2). Under similar experimental conditions, the bromination of aryl substrates 1b–c produced 3b–c in good to excellent yields. While complete conversion to 3f was not achieved even at reduced temperatures, bromination of 1f exhibited the same regioselectivity as the iodination. Surprisingly, reactions of 1-alkyl-cyclobutanols 1d–e produced 3d–e in yields of less than 20%. Examination of GC–MS and 1H NMR data showed that brominations of 1d–e resulted in a mixture of starting material, desired γ-bromo ketone and α,γ-dibrominated ketones.

Table 2.

Synthesis of γ-bromo ketones15

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Product | R | R′ | Yield (%) |

| 1a | 3a | Ph | H | 87a |

| 1b | 3b | p-CH3O-Ph | H | 70a |

| 1c | 3c | p-F-Ph | H | 95a |

| 1d | 3d | Cyclohexyl | H | NDb |

| 1e | 3e | n-hexyl | H | NDb |

| 1f | 3f | p-F-Ph | Et | 37c |

Isolated yield.

Mixture of 1-alkyl-cyclobutanol, γ-bromo ketone and α,γ-dibrominated ketones.

Determined by 1H NMR.

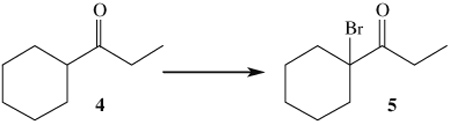

The presence of α-brominated products suggests formation of molecular bromine during the course of the reaction. A series of experiments were performed to determine if this supposition was correct (Table 3). Ketone 4 was used in these experiments since it is structurally similar to the starting material 1d and product 3d. Initially, 1 equiv of 4 was reacted with 0.5 equiv of molecular bromine (entry 1). In a subsequent experiment, substrate 4 was reacted with an equivalent of both CAN and KBr, which should generate an equal amount of molecular bromine if bromine atom homocoupling occurs following oxidation. Experiments contained in entries 1 and 2 show identical ratios of 5:4, a finding consistent with in situ formation of molecular bromine. Interestingly, the yield of 5 was increased by the addition of excess CAN (entry 3), an observation which is indicative of a larger mechanistic role of cerium beyond oxidation, presumably through Lewis acid activation.

Table 3.

α-Bromination of aliphatic substrates

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Conditionsa | Ratio (5:4)b | ||

| 1 | 4 (0.33 mmol), Br2 (0.17 mmol) | 3:1 | ||

| 2 | 4 (0.33 mmol), KBr (0.33 mmol), CAN (0.66 mmol) | 3:1 | ||

| 3 | 4 (0.33 mmol), KBr (0.33 mmol), CAN (0.83 mmol) | 9:1 | ||

50% H2O/CH2Cl2.

Ratios determined by GC.

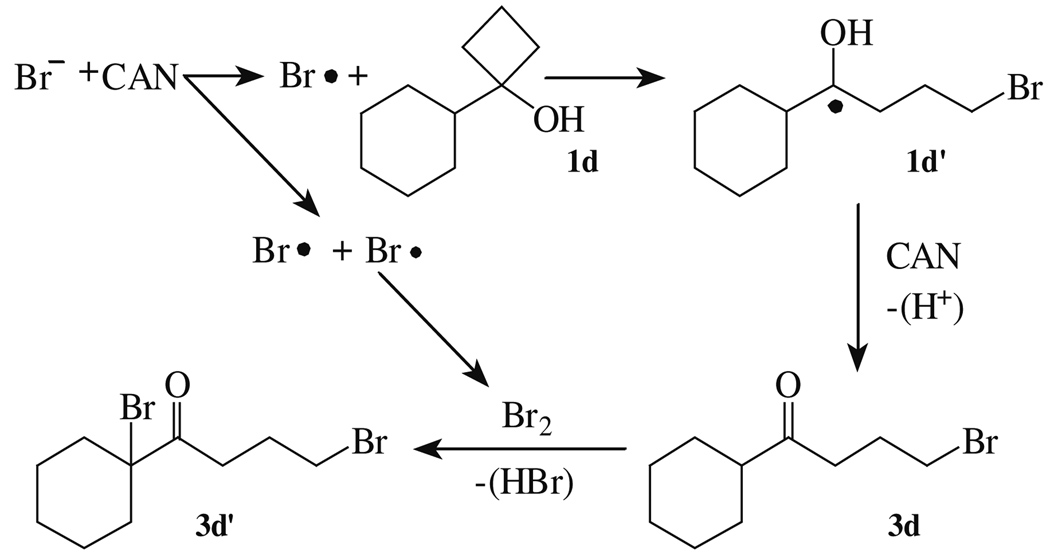

From the data obtained, the mechanistic pathway shown in Scheme 1 is proposed. Initially, bromine anion is oxidized by CAN to bromine radical, which adds to the 1-substituted cyclobutanol 1d. Bromine atom addition to cyclobutanols is supported by the observation that no γ-substituted products were obtained when 1d was treated with molecular bromine. The intermediate 1d′ generated from the ring opening of 1d is less stable than the corresponding benzylic radicals of 1-aryl-cyclobutanols 1a–c. As a result, 1-alkyl-cyclobutanols are expected to be less reactive allowing homocoupling of bromine atoms to become a competitive pathway. Following a second oxidation by CAN of 1d′ and deprotonation, molecular bromine adds α to the carbonyl of 3d producing the α,γ-dibrominated ketone 3d′.

Scheme 1.

Proposed pathway to dibrominated ketones.

Since bromination was only successful in the case of 1-aryl-substituted cyclobutanols, other oxidants were examined to determine whether the desired products could be obtained. Iodinations and brominations with NaI and KBr were performed with Cu-ClO4·6H2O in MeCN.16 However, only a complex mixture of reactions products was obtained, none being the γ-haloketone. The use of ferrocenium hexafluorophosphate in CH2Cl2 provided only unreacted starting material in all cases.17

Due to the rapid evolution and applications of ‘click chemistry’, direct routes to incorporation of azide into molecules would be very useful in synthesis. The extension of this approach to the oxidative addition of azide to 1-substituted cyclobutanols was examined. Unfortunately, oxidative addition of azide anions to 1-substituted-cyclobutanols has been disappointing thus far. When 1 equiv of sodium azide (NaN3) was oxidized by CAN in the presence of 1 equiv of 1a–e, evolution of nitrogen gas was observed even at reduced temperatures providing only starting material after reaction work-up. Even though azide anion is oxidized much faster than 1a–e by CAN, the homocoupling of azide radicals and subsequent decomposition to evolve N2 gas are favoured over radical addition to cyclobutanols. When 5 equiv excesses of NaN3 and CAN were used with 1 equiv of 1a, equal amounts of the desired γ-azido product and the γ-nitrato compound were generated with isolated yields of less than 20%. Although the synthesis of γ-azido ketones using this method was inefficient, subsequent transformations using the accessible γ-iodo and bromo products can produce other substrates including azides and nitriles.18,19

Since CAN is a versatile single-electron oxidant capable of oxidizing a variety of functional groups, this Ce-mediated protocol may appear to be incompatible with more complex substrates. However, rate studies performed by our research group have shown that the oxidation of inorganic anions by CAN is extremely fast indicating that these reagents are oxidized preferentially to other functional groups. Additionally, previous studies on the relative rates of oxidation of substrates and functional groups have shown that selective oxidations can be achieved using CAN.9,20 As a result, this protocol should be applicable to complex molecules providing that substrates do not contain functional groups with rates of oxidation similar to inorganic anions.

3. Conclusions

An alternative route to both γ-iodo and γ-bromo ketones has been developed. The synthesis of γ-iodo ketones from 1-substituted cyclobutanols is general producing both aryl- and alkyl-γ-iodo ketones in good to very good yields. While the synthesis of aliphatic γ-bromo ketones proved to be more difficult, 1-aryl-γ-bromo ketones were obtained in good to excellent yields. In both cases, the halide was shown to add selectively to the least hindered carbon of the cyclobutanol. This method has short reaction times, and provides access to a range of structurally diverse γ-halo ketones that can be used as starting materials for the synthesis of more complex compounds containing γ-substituted ketones.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

R.A.F. is grateful to the National Institutes of Health (1R15GM075960-01) for support of this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.12.114.

References and notes

- 1.van Winjngaarden I, Kruse CG, van der Heyden JAM, Tulip MThM. J. Med. Chem. 1988;31:1934. doi: 10.1021/jm00118a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iorio MA, Paszkowska Reymer T, Frigeni V. J. Med. Chem. 1987;30:1906. doi: 10.1021/jm00393a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen C-A, Jiang Y, Lu K, Daniewska I, Mazza CG, Negron L, Forray C, Parola T, Li B, Hegde LG, Wolinksy TD, Craig DA, Kong R, Wetzel JM, Andersen K, Marzabadi MR. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3883. doi: 10.1021/jm060383x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchida M, Komatsu M, Morita S, Kanbe T, Yamasaki K, Nakagawa K. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1989;37:958. doi: 10.1248/cpb.37.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou J, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14726. doi: 10.1021/ja0389366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Nair V, Deepthi A. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:1862. doi: 10.1021/cr068408n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nair V, Balagopal L, Rajan R, Mathew J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:21. doi: 10.1021/ar030002z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nair V, Panicker SB, Nair LG, George TG, Augustine A. Synlett. 2003:156. [Google Scholar]; (d) Molander GA. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paolobelli AB, Ceccherelli P, Pizzo F. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:4954. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair V, Nair LG, George TG, Augustine A. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:7607. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiao J, Nguyen LX, Patterson DR, Flowers RA. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1323. doi: 10.1021/ol070159h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Hahn RC, Corbin TF, Shechter H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:3404. [Google Scholar]; (b) Çelebi S, Leyva S, Modarelli DA, Platz MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8613. [Google Scholar]

- 11.General procedure for the synthesis of 1-substituted cyclobutanols: All glassware was flame-dried before use. Cyclobutanone (13.4 mmol) was dissolved in 25 mL of diethyl ether and purged with N2. The temperature was reduced to 0 °C. The appropriate Grignard reagent (14.7 mmol) was added dropwise with stirring. The reaction was allowed to stir for an additional 3 h. Water was added slowly to quench the reaction. The organic layer was removed, and the aqueous layer was extracted three times with ether. The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, filtered and concentrated. Pure 1-substituted cyclobutanols were then obtained by recrystallization from n-pentane at −20 °C (1a) or short-path, low pressure distillation (1b,d and e). Compounds 1c,f were produced in quantitative yields and required no additional purification. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were used to assess purity, and are included in the Supplementary data. Tabulated experimental details and product yields are also included in the Supplementary data.

- 12.(a) Zhang Y, Raines AJ, Flowers RA. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:6267. doi: 10.1021/jo048955d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang Y, Raines AJ, Flowers RA. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2363. doi: 10.1021/ol034763d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.General procedure for the synthesis of γ-iodo ketones: Sodium iodide (0.33 mmol) was dissolved in 1 mL of H2O, and was added to the 1-substituted cyclobutanol (0.33 mmol) in 2 mL of DME. The reaction was then purged with N2. CAN (0.67 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of DME, and was added dropwise via syringe with stirring. After stirring for 30 min, the volatiles were removed from the reaction via rotary evaporation. Water was added, and then extracted three times with diethyl ether. The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, filtered and concentrated. The γ-iodo ketones 2a–f were purified further by flash chromatography using a 15% ethyl acetate/hexanes solution as the eluting solvent. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were used to assess purity, and are included in the Supplementary data.

- 14.Nair V, Panicker SB, Augustine A, George TG, Thomas S, Vairamani M. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:7417. [Google Scholar]

- 15.General procedure for the synthesis of γ-bromo ketones: Potassium bromide (0.33 mmol) was dissolved in 1vmL H2O, and was added to the 1-substituted cyclobutanol (0.33 mmol) in 3 mL of CH2Cl2. The reaction was then purged with N2. CAN (0.67 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL H2O, and was added dropwise via syringe with stirring. After stirring for 30 min, the volatiles were removed from the reaction via rotary evaporation. Water was added, and then extracted three times with diethyl ether. The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, filtered and concentrated. The γ-bromo ketones 3a–c were purified further by flash chromatography using a 15% ethyl acetate:hexanes solution as the eluting solvent. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were used to assess purity, and are included in the Supplementary data.

- 16.Kirchgessner M, Sreenath K, Gopidas KR. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:9849. doi: 10.1021/jo061809i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahn U, Hartmann P, Dix I, Jones PG. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:3333. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh PND, Muthukrishnan S, Murthy RS, Klima RF, Mandel SM, Hawk M, Yarbough N, Gudmundsd�ttir AD. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:9169. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iida S, Togo H. Synlett. 2008;11:1639. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiao J, Zhang Y, Devery JJ, Xu L, Deng J, Flowers RA. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:5486. doi: 10.1021/jo0625406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.