Summary

The T=4 tetravirus and T=3 nodavirus capsid proteins undergo closely similar autoproteolysis to produce the N-terminal ß and C-terminal, lipophilic γ polypeptides. The γ peptides and N-termini of ß also act as molecular switches that determine their quasi-equivalent capsid structures. The crystal structure of Providence virus (PrV), only the second of a tetravirus (the first was NωV), reveals conserved folds and cleavage sites, but the protein termini have completely different structures and the opposite functions of those in N⌉V. N-termini of ß form the molecular switch in PrV, while γ peptides have this role in N⌉V. PrV γ peptides instead interact with packaged RNA at the particle 2-folds using a repeating sequence pattern found in only four other RNA or membrane binding proteins. The disposition of peptide termini in PrV is closely related to those in nodaviruses suggesting that PrV may be closer to the primordial T=4 particle than NωV.

Introduction

Virus evolution has resulted in a relatively small number of core subunit folds for the major capsid proteins. The core folds are preserved for key functions such as assembly, integrity and infectivity of the particles, maturation, autoproteolysis, genome packaging and uncoating. Both complex and simple viruses achieve remarkable structural diversity, in part, through less conserved modifications to these core folds. Examples include insertions or deletions, and use of extended N- and C-termini for specific roles (Baker et al., 2005; Fokine et al., 2005; Johnson and Speir, 1997; Khayat et al., 2005; Speir and Johnson, 2008b; Speir et al., 1995). Two model systems for studying these critical structural features in intact capsids are the icosahedral T=4 tetraviruses and T=3 nodaviruses that infect insects and animals.

The tetraviruses (Tetraviridae) are a family of viruses with non-enveloped T=4 capsids that package single stranded, positive sense RNA genomes and infect only a single order of insects, the Lepidoptera (moths & butterflies), making it the only RNA virus family with a host range restricted to insects and non-enveloped T=4 particles (Hanzlik and Gordon, 1997; Speir and Johnson, 2008a). The 400Å diameter icosahedral virions are composed of 240 subunits, each of which undergoes autoproteolysis after the virions assemble, splitting the ~65-70 kDa capsid protein (alpha) into large (~58-63 kDa, beta) and small (~7-8 kDa, gamma) polypeptides that both remain associated with the particle. Genomic organization and particle morphology separate the tetraviruses into two genera: betatetraviruses and omegatetraviruses. Betatetraviruses have monopartite genomes and capsids with distinct pits between surface protrusions easily visualized via cryoEM (Olson et al., 1990; Speir and Johnson, 2008a). Omegatetraviruses have bipartite genomes and oval protrusions on the capsid surface. Evidence suggests that both RNA strands are packaged in a single omega-like particle and that the beta-like viruses often package an additional subgenomic RNA coding for the capsid protein (Pringle et al., 2003). Thus, virus particles from both genera package two RNA molecules, as do the nodaviruses, the only other small, spherical RNA animal viruses with a bipartite genome.

CryoEM structures of several tetravirus capsids have been reported (Johnson et al., 1994; Matsui et al., 2009; Olson et al., 1990; Speir and Johnson, 2008a; Tang et al., 2009), but the 2.8Å resolution structure of authentic Nudaurelia capensis ω virus (NωV), an omegatetravirus, is the only crystal structure previously determined (Helgstrand et al., 2004; Munshi et al., 1996). The NωV crystal structure showed the 644 a.a. capsid subunit has three domains: an exterior Ig-like fold, a central beta jelly roll sandwich in tangential orientation, and an interior helical domain adjacent to the RNA. The helical domain is created by the N- and C-termini of the polypeptide located before and after the jelly roll fold, and the Ig-like domain, unique in non-enveloped virus capsids, is an insert between the E and F beta-strands of the barrel. The architecture of the capsid is controlled by a quasi-symmetrical molecular switch, involving a segment of the cleaved C-terminal gamma peptide (residues 608-641) that is only ordered in the C and D subunits. Importantly, the subunit structure, autoproteolysis sites, and activity of the gamma peptides form a strong relationship between tetraviruses and the T=3 insect nodaviruses. First, their beta-barrel folds and autocatalytic sites superimpose with little variation (Johnson et al., 1994; Munshi et al., 1996). Second, the gamma peptides have a shared biological function. In the nodaviruses they have transient exposure at the capsid surface and can disrupt membranes (Banerjee et al., 2009; Bothner et al., 1998; Schneemann and Marshall, 1998; Schneemann et al., 1998; Venter and Schneemann, 2008). Preliminary studies show that NωV capsids can also disrupt artificial membranes, but only after maturation, indicating that tetravirus gamma peptides are lipophilic like those of the nodaviruses (Odegard and Johnson, unpublished data). However, there is no high resolution structure for any of the other eleven members of the tetraviridae to determine what form their subunit folds and molecular switches take, especially within the more populated betatetravirus genus.

Studies of Providence virus (PrV) were undertaken in order to obtain the structure of a betatetravirus. Which features of the PrV structure, if any, are retained between tetravirus family members and possibly with the nodaviruses? PrV was discovered as a persistent infection in a midgut cell line (MG8) derived from the corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea), making it the only tetravirus shown to replicate in cell culture (Pringle et al., 2003). Although its coat protein has higher sequence similarity with the omegatetraviruses (46-47%) than with the betatetraviruses (35%), PrV was classified as a betatetravirus because of its monopartite genomic organization and pitted surface capsid morphology (Pringle et al., 2003). It’s capsid protein precursor contains 755 a.a. and is rapidly cleaved into the 632 a.a. (68 kDa) precursor protein, alpha, and a 123 a.a. non-structural protein of unknown function. The 68 kDa alpha precursor is then autocatalytically cleaved after capsid assembly into the beta (60 kDa) and gamma (8 kDa) structural polypeptides. Despite repeated attempts using a number of approaches, only insoluble aggregates of PrV coat protein could be produced in a recombinant baculovirus expression system. However, a small quantity of purified authentic virus sufficed to perform structural studies (Taylor et al., 2006). Here, we present both a cryoEM image reconstruction and a 3.8Å resolution X-ray crystal structure of PrV, the second of a tetravirus and the first from the beta-like genus. The structure of PrV reveals both interesting differences and similarities to the known tetravirus and nodavirus structures. In particular, the roles of the capsid protein termini have been exchanged in the molecular switch. A small segment of RNA is intimately associated with the repositioned gamma peptide, which has a repeating sequence pattern that is present in only four other proteins, two that bind RNA and two that bind membranes.

Results and Discussion

Capsid and subunit structures

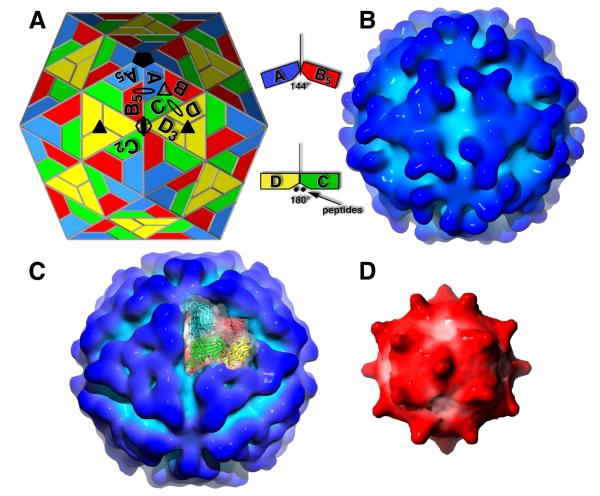

A cryoEM reconstruction of PrV was determined to 28Å resolution, showing a T=4 quasi symmetric protein shell and the characteristic triangular pitted surface of betatetraviruses (Fig. 1C). The capsid is 420Å in diameter with a protein shell thickness of nearly 100Å at its largest dimensions. Linear depressions running between the 5-fold axes mark the bent contacts between the flat triangular facets and the triangular pitted surface is a feature of all betatetraviruses characterized at moderate resolution to date. In addition to the well defined protein shell, the PrV reconstruction showed an uncharacteristically well defined RNA core (Fig. 1D). Depressions appear at the 5-fold axes of the RNA core in contrast to bulges at the 2-fold axes that reach up and contact the protein shell (see below). The volume of the RNA density is approximately 3.4×106 Å3, which can accommodate between 5100-11800 RNA bases depending on the level of hydration (Johnson and Rueckert, 1997). The two RNA strands packaged in the PrV capsid contain 8900 bases, which is in the middle of the range. Thus, this may correspond to the entire RNA content of the particle if it is packed at a high density like the genomes of picornaviruses (Johnson and Rueckert, 1997).

Figure 1.

Electron cyro-microscopy reconstruction of Providence virus. (A) A T=4 quasi-symmetry model of the tetravirus capsids. Positions of icosahedral and quasi-icosahedral rotations axes are shown as filled and unfilled geometric symbols, respectively (oval = twofold; triangle = threefold; pentagon = fivefold; hexagon = sixfold). The A, B, and C polygons related by a quasi 3-fold, and the D polygon related to C by a quasi 2-fold, define the icosahedral asymmetric unit (ABCD). Each of the polygons represent identical protein subunits but occupy slightly different geometrical (chemical) environments. Polygons with subscripts are related to those without by the icosahedral symmetry of the subscript (i.e. A to A5 by 5-fold rotation). Unlike T=3 capsids, there is no icosahedral 2-fold dimer. Instead, the icosahedral 2-folds are coincident with quasi 6-fold arrangements of B, C, and D subunits (3 sets of dimers). Looking at the arrangements of ABC and DDD subunit triangles clarifies tetravirus capsid architecture. In a clear break from quasi equivalence, ABC triangles form a bent interface with each other and ABC-DDD triangles form a flat interface due to the insertion of subunit polypeptides at the interface. (B) Surface representation of the NωV reconstruction at approximately 21 Å resolution and in the same orientation as (A). Darker blue areas are at a greater radius from the particle center. The subunit Ig-like domains form large, contiguous triangular facets with curved edges around the icosahedral 3-fold axes. (C) Surface representation of PrV at approximately 28 Å resolution (same coloring and orientation as A and B). The subunits of one icosahedral asymmetric unit are shown as ribbons through their corresponding transparent surface. The most distinctive difference from NωV is that the triangular facets now have nearly straight edges and 3-fold related pits (characteristic of betatetraviruses) due to a change in the orientation of the Ig-like domains. (D) Surface representation of the PrV RNA core (same orientation as A, B, C) after removing density corresponding to the crystal structure protein coordinates. Darker red areas are at a greater radius from the particle center. Large bulges of density extend from the core at each icosahedral 2-fold axis and make contact with the capsid protein shell.

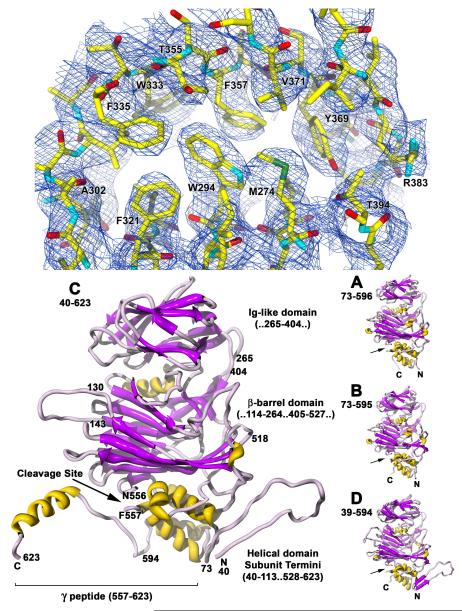

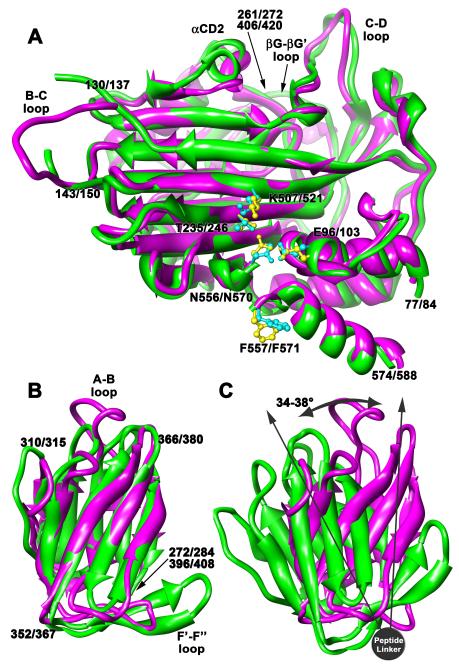

The crystal structure of PrV at 3.8 Å resolution revealed some completely new features. As seen in NωV, the PrV capsid subunit has three domains: an exterior Ig-like fold (272-396), a central jelly roll beta sandwich in a tangential orientation (77-261, 406-574), and an interior helical domain formed by residues 1-77 and 575-631 (Fig. 2). The beta sandwich and helical domains are closely similar to those of NωV (Fig. 3A). The r.m.s.d’s range from 1.3 Å to 1.6 Å after superposition of the related subunits (i.e. 84-272 and 420-588 of the NωV A subunit to 77-261 and 406-574 of the PrV A subunit). The largest deviations occur in the B-C, C-D, and G-G’ loops, with the latter two being positioned under the Ig-like domain.

Figure 2.

The crystal structure of Providence virus. (Top) Electron density from the C subunit Ig-like domain core contoured at approximately 1.5σ. The beta strands and side chains are clearly delineated in the 30-fold averaged map. (Bottom) Ribbon representation of all four quasi equivalent subunits (top – capsid exterior, bottom – capsid interior). The C subunit is enlarged to show the different domains and their residue ranges (labeled to the right), the cleavage site (labeled with arrows in all 4 subunits), and its extended gamma peptide (underlined). The residue range fitted is shown underneath each subunit letter. Note that subunits A, B, and D do not have an extended gamma peptide as see in C, but the D subunit has an extended N-terminus with an almost identical structure to that of C.

Figure 3.

Tetravirus structure comparison. (A) Superposition of the beta barrel and core helical domains of the PrV (magenta) and NωV (green) C subunits viewed tangential to the protein shell. Residues 77-261 and 406-574 from PrV were aligned with residues 84-272 and 420-588 of NωV. Labels list the PrV residue number first, followed by a slash, then the NωV residue number. The r.m.s.d is 1.5Å and the sequence identity is 47% for 350/356 aligned residues. The autoproteolysis sites have identical key residues, shown in blue for Prv and yellow for NωV, and closely similar structures. The Ig-like domains would be attached at the positions designated by the long arrow at the top. (B) Superposition of the Ig-like domains from the C subunits (same coloring and labeling as above). Residues 272-396 of PrV were aligned with residues 284-408 of NωV. More variation occurs in these domains, mainly in the turns between beta strands, resulting in an r.m.s.d of 2.4Å. The sequence identity is only 15% for 113/125 aligned residues. (C) The orientations of the C-subunit Ig-like domains when the beta barrels are aligned as in (A). The domains have strikingly different rotations about the peptide linker that range between 34-38° depending on the subunit.

The Ig-like domain folds are also similar but show more variation (Fig. 3B). The r.m.s.d’s range from 2.3-2.4 Å for the related subunits. The beta strands align well between PrV and NωV but the turns between the strands have different lengths and structures. Most striking is that the Ig-like domains have different orientations relative to the beta barrels (Fig. 3C). The rotation differences about the peptide linkers between the PrV Ig-like domains and those of NωV range from 34-38°. This creates the well defined triangular, pitted facets observed on the surfaces of the betatetraviruses. Interestingly, sequence similarity is much lower between the Ig-domains of the tetraviruses than any other domain, suggesting the combined sequence and structure variations are to enable host-specific interactions.

Autoproteolysis cleavage sites

The autoproteolysis sites of PrV and NωV have identical key residues and closely similar structures (Fig. 3A). Residues identified in previous studies of NωV to be involved in the cleavage reaction are N570 and F571 (the scissile bond), E103, T246, and K521 (Taylor, 2005). The corresponding residues in PrV are the same: N556 and F557, E96, T235, and K507. Thus, the proposed deamidation cleavage mechanism is likely to apply to PrV (Munshi et al., 1996; Zlotnick et al., 1994). Additional residues within a 6 Å radius of the scissile bond are also conserved in both PrV and NωV: Asp90/97, Ala92/99, Gly93/100, Tyr439/453, as well as Gln429/443 in symmetry related subunits. It is not known if any of these additional residues are involved in the cleavage reaction, but all of them reside in small conserved regions identified after the structures were aligned. Their interactions may be important in maintaining the structure of the sites and to help stabilize the asparagine during or after the cleavage reaction.

While the cleavage sites and jelly roll, helical and Ig-like domains are similar between PrV and NwV, the subunit termini have strikingly different regions of ordered polypeptide, structures, and interactions. Indeed, the N- and C-termini of PrV and NωV exchange functions in each capsid, but result in identical outcomes relative to the capsid architecture.

Two different ways to build the same molecular switch

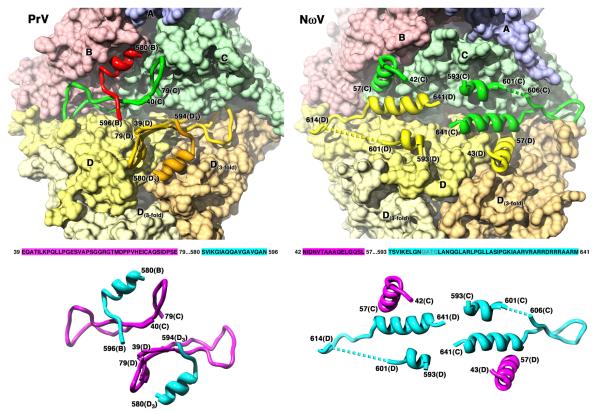

The architecture of T=4 quasi-equivalent icosahedral capsids can be reduced to the interaction of two trimers, each composed of 3 subunits (Helgstrand et al., 2004). One trimer is formed by the A, B, and C subunits and is arranged around the icosahedral 5-fold axes. The other trimer has three D subunits related by the icosahedral 3-fold axes (Figure 1A). The angular interactions between these triangular units occur at two different quasi 2-fold axes that determine the shape of the capsid. The angle between adjacent ABC triangles is bent, while the angle between an ABC triangle and a DDD triangle is flat. The blend of these two types of dihedral angles creates a closed particle. These interactions are controlled by the order, or lack of order, in the subunit termini.

The flat contact in NωV is supported by the gamma peptides (cleaved C-termini) of the C and D subunits from the same icosahedral asymmetric unit (Fig. 4). In both subunits, residues 624-641 form a short extended polypeptide followed by a 3-turn helix that runs tangential to the capsid and sits in the groove between them. The gamma peptide structures are closely related by the quasi 2-fold symmetry and terminate just before crossing each other in the inter-subunit groove; thus, the gamma peptides fill the groove between their own subunits. The helices interact with other regions of the same gamma peptide (residues 594-601), but also with the N-terminus of the quasi 2-fold related subunit. Residues 42-74 of the C subunits and 43-74 of the D subunits form a loop and 4-turn helix that is oriented toward the interior of the particle. These structures are brackets that hold the quasi 2-fold related gamma peptides in the groove. Thus, the quasi-equivalent switch in NωV is formed by the C-termini of the C and D subunits.

Figure 4.

Opposite roles for PrV polypeptides forming the molecular switch. (Top) Inside surface representation of the flat contacts. Subunits are shown colored as in Fig. 1A, except that the three D subunits are differentiated using shades of yellow to gold. The ordered polypeptides that form the switch are shown as ribbons without their corresponding surfaces. In PrV, extended N-termini from C (40-79) and D (39-79) fill the groove, and are supported by the last ordered residues of the C-terminal gamma peptides from quasi or icosahedral 3-fold related subunits (B580-B596 and D580-D594, respectively). In NωV, the same roles for the polypeptides are reversed. Extended C-terminal gamma peptides from the C and D subunits (593-641) fill the groove and are supported by the first ordered residues of the quasi 2-fold related subunit: D43-57 supports the C subunit gamma peptide, and C42-57 supports the D subunit gamma peptide. (Bottom) Diagram showing just the molecular switches from PrV and NωV. The relevant capsid protein sequence of each section is shown and color coded as the N-terminal peptides (magenta) or the C-terminal peptides (blue). The structure of each is shown with the same color coding, demonstrating the swap of N-termini for C-termini between PrV and NωV for the same roles in forming the flat contacts.

The structural elements that support the flat contact in PrV have completely different structures and are derived from opposite ends of the protein when compared to NωV (Fig. 4). The 30-fold averaged density for the PrV polypeptide termini unambiguously showed that they take different directions underneath the subunits compared to those of NwV. Well defined side chains allowed straightforward de novo tracing and sequence assignment of the PrV termini. The gamma peptide of the D subunit in PrV is disordered after residue 594, and never enters the groove. The C subunit gamma peptide is ordered to residue 623 and extends in the opposite direction from the groove across the quasi 6-fold axis (icosahedral 2-fold) underneath the capsid hexamers (see below). The PrV groove is filled by residues 40-78 from both the C and D subunits and they form large loops that stretch out across the groove directly in front of the quasi 2-fold related subunit, not in front of their own subunits as the C-termini do in NωV. A new role for the PrV gamma helices is the bracing of the N-termini positioned in the grooves. Residues 590-596 of the B-subunit gamma peptide run beneath the C subunit N-terminus, and residues 590-594 of a 3-fold related D subunit run beneath that of the D subunit (Fig. 4). Both of these small stretches of residues are the last ordered polypeptide found in the B and D subunits. Relative to NωV, the structural elements used in the PrV molecular switch have been exchanged; the N-termini fill the groove instead of the C-termini, and the symmetry related C-termini support the polypeptides filling the groove instead of the local N-termini. This arrangement is similar to the nodaviruses Flock House virus (FHV) and Pariacoto virus (PaV), which use extended N-arms to fill the groove along with duplex RNA (Fisher and Johnson, 1993; Tang et al., 2001). Thus, the PrV polypeptide termini have different folds and functions, and form different structures and contacts when compared to those of NωV. This exchange of roles to support the same critical subunit interfaces for T=4 capsid formation illustrates the extraordinary plasticity of the molecular switches.

T=3 to T=4 particle evolution

The quaternary structures of both PrV and nodaviruses require a change in dihedral angle between identical subunit interfaces related by either two different quasi 2-fold contacts (PrV) or between a quasi 2-fold contact and an icosahedral 2-fold contact (nodaviruses). The interfaces at these locations are either flat (180° dihedral angle) or bent (~138° dihedral angle). In each case, the flat contacts result from an N-terminal polypeptide and, in FHV and PaV, a segment of RNA that insert into the interface to prevent the bending. The equivalent segments of protein and RNA are disordered at the bent contacts allowing the subunits to hinge down. Strikingly, NωV has evolved so far from PrV that C-terminal regions of the subunit are used to switch these contacts. We suggest that PrV is closer to the primordial T=4 particle, presumably derived from the T=3 nodaviruses, than NωV because it uses molecular switches that are closely similar to those of the nodaviruses. In contrast, while the jellyroll fold of NωV superimposes well on both PrV and FHV, the molecular switch is derived from the opposite termini.

PrV C subunit extended gamma peptide structure

The gamma peptides of the PrV C subunits adopt an extended structure strikingly different than that of NωV (Fig. 2 bottom, Fig. 5A). Starting at the bottom of the protein shell (residue 594), the 2-fold related polypeptides extend away from the subunit cores and up toward the shell domains (residues 599-606), then they flatten out across the icosahedral 2-fold (quasi 6-fold) axes where they interact with each other to form an anti-parallel helix dimer (607-618). Residues 619-623 dip back toward the interior after the dimer contact. These interactions create a small, internal concave cavity at the icosahedral 2-fold axes (center of the quasi-symmetric hexamers).

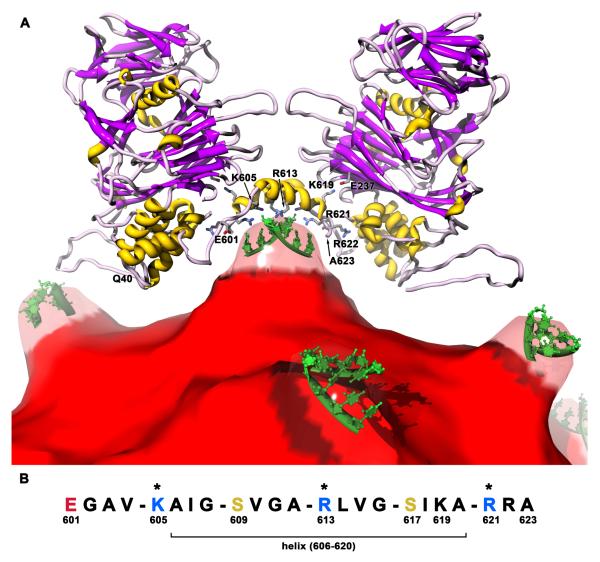

Figure 5.

Protein-RNA contacts between the C subunit gamma peptides and packaged genome in PrV. (A) The gamma peptide structures create a concave volume 28Å in diameter containing 12 charged residues (10 basic, 2 acidic) that is filled with RNA. One pair of icosahedral 2-fold related C subunits (ribbons) are shown above the RNA core (red) viewed tangential to the capsid shell. The RNA protruding at the 2-folds (Fig. 1D) has been made transparent to show the small section of partially ordered RNA (green) observed in the crystal structure. Side chains with key interactions are shown on the anti-parallel helices sitting over the RNA (only those on the front helix are numbered). (B) Sequence of the gamma peptide at the site of RNA interactions. Acidic residues are red, basic are blue, and other hydrophilics are gold. Residues with asterisks directly contact the ordered RNA. A pattern of a single hydrophilic residue followed by 3 hydrophobic residues repeats 5 times, which structurally forms a hydrophobic zipper between the anti-parallel helices with the hydrophilic residues oriented downward toward the RNA. Sequence searches using this pattern revealed some similarities to other RNA and membrane binding proteins.

Residues 607-618 form a 3 turn amphipathic helix, with hydrophilic and charged residues oriented toward the interior of the particle and small hydrophobic residues oriented upward toward the protein shell and toward the 2-fold related helix (Fig. 5A). The 2-fold axis goes through the center of the helix dimer with the side chains of Leu614 residues on either side that form a non-polar interaction at the 2-fold. The Leu614 side chains are bracketed by 2-fold related Val610 side chains, and two more sets of “teeth” formed by the interdigitation of Ile607, Ile618 and Val604 progressing toward the ends of each helix. This creates a 10 residue, anti-parallel, non-polar zipper between the 2-fold related helices (604, 607, 610, 614, 618).

Facing the inside of the capid are Lys605, Arg613, and Arg621 from each helix (6 total from both helices), making a highly positive, concave surface oriented toward the packaged RNA (Fig. 5A). Just beneath these residues and sitting on the 2-fold axis is a duplex of partially ordered RNA. Four nucleotides, each arbitrarily modeled as uridine, were fitted to the density (U1-U4). The RNA duplex is positioned on the icosahedral 2-fold axis. The first nucleotide is unpaired, while the other three form base pairs with their 2-fold related nucleotides. The nucleotide bases correspond to broad, continuous density across both the stacking interactions between bases on the same strand, and in the base pair interactions. In contrast, the ribose-phosophate backbone is poorly represented by the density, with some breaks between phosphate linkages. Connectivity between phosphates and better definition of the nucleotides occurs at low contour levels (e.g. 0.7, still above noise due to the 30-fold averaging) but the density still does not encompass all features of the model. The temperature factors after refinement are twice that of the protein average, reflecting the limited order of the RNA duplex density.

The three positively charged residues in each helix make contact with the RNA duplex (distance of < 4.5Å). Together they make van der Waals contact and potential hydrogen bonds with all 4 nucleotides. The side chains of Lys605 and Arg621 both have well ordered density and are positioned at each end of the duplex. Lys605 is slightly above the nucleotide plane and in position to hydrogen bond with both the base and ribose of U4. Arg621 is in plane with the nucleotides and can hydrogen bond with the bases of both U1 and U2 (but the geometry of contacts to U1 are not optimal). The 2-fold related Arg621, which sits next to and a little below Lys605, can also form hydrogen bonds with both the base and ribose of U4. Thus, while Lys605 acts to bind only the nearby RNA strand, Arg621 interacts with both strands of the duplex.

Arg613 also interacts with both strands of the duplex. The main chain of Arg613 is adjacent to the 2-fold axis and sits above the U3 backbone. The side chain is partially disordered but density appears for the guanidinium group centered over the U4 base. Potential hydrogen bonds to the U4 and 2-fold related U3 bases can be formed, along with a possible stacking interaction between the guanadinium group and the U4 base. The use of Arg and Lys side chains, mainly bonding bases and sugars, and the concave binding site are all characteristics of RNA binding proteins (Bahadur et al., 2008; Ellis et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2001; Morozova et al., 2006).

PrV gamma peptides create an unusual RNA binding motif

BlastP searches (Altschul et al., 1997) detect no significant sequence similarity between residues 557-623 of PrV and entries in the GenBank database using. This was unexpected as residues 364-380 of the FHV gamma peptide returns hits from other nodaviruses. There are no sequence patterns in the full PrV capsid protein that match an entry in the Prosite database (Hulo et al., 2008). These results highlight the unusual capsid sequence characteristics of the betatetraviruses, even within their own virus family. However, the structure of the anti-parallel, non-polar zipper and regular spacing of RNA binding residues in the C subunit gamma peptides creates a repeating sequence pattern (Fig. 5B) that is present in other RNA and membrane binding proteins.

The sequence from 601-621 has a hydrophilic or charged residue that points toward the particle interior and the duplex RNA followed by three small non-polar residues, and this is repeated four times (EGAV-KAIG-SVGA-RLVG-SIKA-R). A fifth repeat is also present, with the exception of Lys619 in the non-polar section. Lys619 points upward toward the capsid shell where it forms salt-bridges with 2-fold related residues Glu237 and Asp554, and quasi 6-fold related residue Glu434. The latter may act to stabilize the C-terminus structure at the 2-fold axes. The last RNA binding arginine residue completes the pattern. The pattern coded for Prosite searches is: [DEKRS]-[GAVIL](3)-[DEKRS]-[GAVIL](3)-[DEKRS]-[GAVIL](3)-[DEKRS]-[GAVIL](3)-[DEKRS]-[KGAVIL](3)-[DEKRS], where any residue listed between the brackets can be in that position, and the number after the brackets is how many repeats of that residue list are expected (Sigrist et al., 2002). Aspartate was added to the hydrophilic list for completeness although it isn’t in this part of the sequence. The size and complexity of the pattern limits the expected number of random matches to be less than 0.01 in 100,000 sequences.

Searches of the SwissProt database with the PrV C-terminus pattern resulted in four hits: two RNA and two membrane binding proteins. The RNA binding proteins are fibrillarin (31-34kDa) from yeast and the trypanosome protozoa Leishmania (patterns are RGGA(3)-KGGA-KVVI-E and RGGG(5)-R, respectively). Fibrillarin is an abundant nucleolar protein widespread among organisms and known to be involved in the processing of ribosomal RNA precursors (Shaw and Jordan, 1995). The pattern matches the glycine and arginine rich domain (GAR, also called RGG box in other RNA binding proteins) found in all fibrillarins and other nucleolus proteins involved in RNA interactions, but which have variable sequences. GAR domains appear to non-specifically bind pre-ribosomal RNA to unwind the helix, thereby facilitating more specific interactions by other proteins (Ghisolfi et al., 1992). The membrane interacting proteins are the abundant Merozoite surface antigen 2 (MSA-2, 28kDa) from isolates 3D7 and FCR-3 of Plasmodium falciparum, the protozoan parasite that causes the most severe form of human malaria and is responsible for nearly all malaria-specific mortality (Snow et al., 2005). The N-terminal portion of MSA-2 is thought to play a role in recognition and attachment to erythrocyte membranes. The pattern matches repeats of GGSA (e.g. SAGG-SAGG…) that start around residue 55, just after a conserved region at the N-termini (Smythe et al., 1988; Smythe et al., 1991). A recent study revealed that the N-terminal residues of MSA-2 interact with artificial membranes in vitro (Zhang et al., 2008).

The postulated functions of the fibrillarin and MSA-2 segments identified using the prosite pattern are surprisingly consistent with the functions of the 44 residue gamma peptide of FHV, namely membrane disruption and RNA packaging. The N-terminal 21 residues of FHV gamma form an amphipathic helix that can disrupt membranes in vitro and is likely the host membrane-interacting region of FHV during cell entry (Maia et al., 2006). The C-terminal 23 residues of FHV gamma are hydrophobic and contain three phenylalanine residues responsible for specifically packaging viral RNA during assembly (Schneemann and Marshall, 1998). While these specific activities appeared local to either half of the peptide, recently it has been shown that full length gamma was necessary to restore infectivity to a maturation-defective FHV and that regions other than the membrane interacting segments may play roles in keeping the particle in a state of readiness for biological activity (Banerjee et al., 2009).

The PrV gamma peptide has both functions assigned, via Prosite annotations, to the same polypeptide, whereas they are separated, but interdependent on the FHV gamma peptide. Both peptides place these functions in close proximity to one another, indicating there is an important link between cell entry and genome interactions in their virus life cycles. Indeed, exposure or loss of lytic peptides always precedes release of the genome. In the crystal structure of FHV the amphipathic helices of gamma contact ordered RNA, but are situated at the periphery of the RNA structure and only interact with the ribose-phosphate backbone. The remainder of FHV gamma provides more specific recognition, yet FHV does not form empty particles and will package either viral or heterologous RNA into a dodecahedral cage across the 2-folds (Tihova et al., 2004). The amphipathic helices of the PrV gamma are directly associated with the RNA and have common features of RNA binding proteins: Arg or Lys residues utilized in a concave binding site that primarily binds bases and sugars. Thus, it appears to provide both membrane penetration and RNA binding functions in a single segment. These overlapping activities together with the anti-parallel helix interaction at the 2-folds may constitute a binding site specific for features of the PrV genome, though the specificity of the RNA binding by PrV gamma has not been determined. This would explain the inability to generate virus like particles of PrV in a baculovirus system as it lacks the genomic RNA that would be required for particle assembly (Taylor et al., 2006). While the structural and RNA binding functions of the nodavirus and tetravirus gamma peptides can vary, it remains to be determined how many share the ability to disrupt membranes.

RNA binding, packaging, and release are essential functions of a virus capsid. While a broad diversity of mechanisms are used to accomplish this task throughout virology, both PrV and FHV (i.e. tetraviruses and nodaviruses) share many structural features in relation to this mechanism, such as the autocatalytic cleavage site, binding of RNA at the particle 2-folds and employing the N-terminal portion of the subunit as a molecular switch for mediating one of the quasi-equivalent contacts. An additional shared feature is the gamma helix bundles at the particle 5-folds. In FHV, a bundle composed of 5 gamma helices has been proposed as a membrane insertion complex that will drag the RNA along with it during the invagination process (Cheng et al., 1994). In PrV, a bundle composed of 10 gamma helices is closely similar to that of FHV, suggesting a similar activity is possible as was suggested for NωV (Munshi et al., 1996). The most striking difference is the environment for RNA binding observed in PrV and FHV. In FHV, the ordered RNA binding site is located between the hexamers. In PrV, it is at the center of the hexamers; thus, the RNA is associating directly with a potential insertion complex at the quasi 6-fold axes. Although the gamma helices do not form as regular a bundle as that at the pentamers, they are covered by only a few loops from the beta-barrel domains, putting them in a good position for translocation across the membrane. This may represent partial formation of a membrane insertion complex with bound RNA that provides a more complete model for transfer of the RNA out of the particle and into the cell. How the actual delivery of the genome is accomplished remains an active area of research for both nodaviruses and tetraviruses.

Experimental Procedures

Purification and Crystallization

PrV was purified, crystallized, and its crystal structure determined as described (Taylor et al., 2006). Briefly, PrV was maintained in an H. zea midgut cell line (referred to as MG8) and the particles purified via high speed pelleting through a 30% sucrose cushion followed by velocity sedimentation on a 10-40% sucrose gradient. Two μl of virus (approximately 7 mg/ml) stored at 4°C in 20 mM Tris, pH7.5 was mixed with 2 μl of reservoir solution and maintained at 22°C to grow crystals using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. The reservoir buffer was 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.5 and ranged from 0.5 – 1.5% PEG 8000 and 10 – 100 mM NaCl. Monoclinic crystals grew to 0.1 mm plates within one to four weeks.

Electron cryo microscopy and image reconstruction

A 5μl virus sample (1.5mg/ml) was applied to a holey carbon film on a copper EM grid, blotted with filter paper to near dryness, and rapidly frozen by plunging into liquid ethane slush. Examination and imaging at approximately −180°C were carried out using a Gatan Model 626 cryotransfer system in a Philips CM200FEG electron microscope operating at 120kV. Images were recorded under low dose conditions (<10e/Å2) at a nominal magnification of 38,000 and a defocus of about −1μm. Micrographs were digitized on a Zeiss SCAI scanner with a step size of 7 μm and averaged so that the pixel size of the final images was 5.52 Å. 246 particles were manually picked using the program EMAN (Ludtke et al., 1999) and used in the three-dimensional reconstruction with the program SPIDER (Frank et al., 1996). Independent reconstructions were obtained using the atomic coordinates of NωV (Munshi et al., 1996) and a feature-less 400 Å diameter sphere with constant density as reference starting models. Cycles of angular refinement were performed with an angular interval of 1.5° until convergence. Full icosahedral symmetry was imposed during the reconstruction. Final reconstructions based on either starting model were the same, confirming a unique PrV structure. In order to evaluate the quality of the reconstruction, the 246 images were divided into two groups for Fourier shell correlation and phase residual computations between the two reconstructions. The resolution of the final reconstruction was estimated as 28 Å where the phase residual was still below 50°.

Structure Determination and Analysis

The PrV crystal structure was determined as previously described (Taylor et al., 2006). Initial phases were computed from 50-8Å resolution using the coordinates of NωV (Munshi et al., 1996) fitted to the cryoEM reconstruction of PrV, then oriented and positioned in the PrV cell. The phases were refined and extended to 3.8Å resolution using the 30-fold non-crystallographic symmetry for real-space averaging (Rave = 30.4%, CCave = 0.72). Electron density quality in the initial averaged electron density map was sufficient to recognize the subunit folds and the different orientation of the Ig-like domain, but the map had some discontinuous and poorly defined regions. Individual domains were re-fitted into the PrV density and portions of the PrV structure were built. This initial PrV model was refined using CNS v1.1 (Brunger et al., 1998) as two rigid bodies for each of the four subunits in the icosahedral asymmetric unit (Ig-like domain, β-barrel & helical domains) to an R-factor of 50.0% for data between 15-8Å resolution. The resulting coordinates were used to average the electron density at 3.8Å resolution and produced an improved map clearly showing that the Ig-like domains and parts of the helical domains had to be built de novo. Several more cycles of rebuilding, averaging, and coordinate refinement in CNS v1.2 (Brunger, 2007) gave an excellent quality map that allowed contiguous polypeptide traces for all 4 subunits (to varying lengths) and confident positioning of amino acid side chains. While a few of the B-values did not correlate well with the strength of ordered density as expected at this resolution (DeLaBarre and Brunger, 2006), B-value refinement was validated by plotting the average value per residue for each of the four independent subunits, which showed closely overlapping profiles that correlated well with the residue environment (e.g. buried v.s. exposed, termini, loops). Harmonic restraints were added to partially disordered loop regions (e.g. 215-224) to stabilize polypeptide geometry in the last rounds of refinement. The final round of refinement with 16553 protein atoms, 77 RNA atoms, 6 water molecules, and 2 calcium ions gave an Rcryst of 28.5% for all data (Table 1), and the final averaging cycle gave an Rave of 26.4% and CCave of 0.79.

Table 1.

Data processing and refinement statistics for the PrV crystal structurea.

| Data collection | ||

|---|---|---|

| (All data) | (Outer shell) | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0-3.8 | 3.94-3.8 |

| Unique Reflections | 272211 | 25858 |

| Completeness (%) | 29.6 | 28.2 |

| Rmerge (%)b | 15.8 | 24.9 |

| Average I/σI | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| Redundancyc | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Refinement | ||

|---|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0-3.8 | 3.97-3.8 |

| Unique Reflections (F/σF > 0) | 263822 | 29998 |

| Completeness (%) | 28.6 | 26.1 |

| Rcryst (%)d (F/σF > 0) | 28.5 | 30.9 |

| No. of atomse (Cα atoms) | 16638 (2187) | |

| Ribonucleotides, Ions & Waters | 12 | |

| Protein geometry & thermal parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD from ideality: | Ramachandran Plot (%): | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 | Favored | 70.0 |

| Angles (°) | 1.7 | Allowed | 29.0 |

| Dihedrals (°) | 25.2 | Generous | 1.0 |

| Impropers (°) | 1.06 | Disallowed | 0.0 |

| Average B values (Å2): | |||

| Protein (2187 residues) | 20.8 | ||

| RNA (4 residues) | 57.2 | ||

| Waters, Ions (8 atoms) | 19.3 | ||

Values given are for all data. The space group is C2 with unit cell dimensions a = 659.8 Å; b = 434.1 Å; c = 415.9 Å; and β = 126.1°.

Rmerge = (∑h∑i (Ihi - <Ih>)/∑h∑i Ih) × 100 where <Ih> is the mean of the Ihi observations of reflection h.

Redundancy = < # observations / # unique reflections >.

Rcryst = (∑h∣Fo - Fc∣/∑hFo) where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors.

Number for all non-hydrogen atoms, including waters.

PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993), MolProbity (Davis et al., 2007), and the PDB validation tools were used to examine and validate polypeptide geometry. Subunit interactions were identified using ViperDB analysis (Carrillo-Tripp et al., 2009) and the hydrogen bond tool in Chimera for OS X (Pettersen et al., 2004). All the figures were produced using Chimera.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ronald A. Milligan, Kelly Dryden, Mark Yeager, and Elisabetta Sabini for help with cryo-EM data collection and analysis. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 GM 54076 (J.E.J).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession Numbers The coordinates for the PrV icosahedral asymmetric unit have been deposited in the PDB with accession number 2QQP. The structure is also available from the VIPER database (viperdb.scripps.edu).

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur RP, Zacharias M, Janin J. Dissecting protein-RNA recognition sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2705–2716. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker ML, Jiang W, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. Common ancestry of herpesviruses and tailed DNA bacteriophages. J Virol. 2005;79:14967–14970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14967-14970.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee M, Khayat R, Walukiewicz HE, Odegard AL, Schneemann A, Johnson JE. Dissecting the functional domains of a nonenveloped virus membrane penetration peptide. J Virol. 2009;83:6929–6933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02299-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothner B, Dong XF, Bibbs L, Johnson JE, Siuzdak G. Evidence of viral capsid dynamics using limited proteolysis and mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:673–676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Tripp M, Shepherd CM, Borelli IA, Venkataraman S, Lander G, Natarajan P, Johnson JE, Brooks CL, Reddy VS. VIPERdb2: an enhanced and web API enabled relational database for structural virology. Nucleic Acids Res. (3rd) 2009;37:D436–442. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng RH, Reddy VS, Olson NH, Fisher AJ, Baker TS, Johnson JE. Functional implications of quasi-equivalence in a T = 3 icosahedral animal virus established by cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography. Structure. 1994;2:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. (3rd) 2007;35:W375–383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLaBarre B, Brunger AT. Considerations for the refinement of low-resolution crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:923–932. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906012650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JJ, Broom M, Jones S. Protein-RNA interactions: structural analysis and functional classes. Proteins. 2007;66:903–911. doi: 10.1002/prot.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AJ, Johnson JE. Ordered duplex RNA controls capsid architecture in an icosahedral animal virus. Nature. 1993;361:176–179. doi: 10.1038/361176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokine A, Leiman PG, Shneider MM, Ahvazi B, Boeshans KM, Steven AC, Black LW, Mesyanzhinov VV, Rossmann MG. Structural and functional similarities between the capsid proteins of bacteriophages T4 and HK97 point to a common ancestry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7163–7168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502164102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Radermacher M, Penczek P, Zhu J, Li Y, Ladjadj M, Leith A. SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:190–199. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisolfi L, Joseph G, Amalric F, Erard M. The glycine-rich domain of nucleolin has an unusual supersecondary structure responsible for its RNA-helix-destabilizing properties. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2955–2959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzlik TN, Gordon KH. The Tetraviridae. Adv Virus Res. 1997;48:101–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgstrand C, Munshi S, Johnson JE, Liljas L. The refined structure of Nudaurelia capensis omega virus reveals control elements for a T = 4 capsid maturation. Virology. 2004;318:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulo N, Bairoch A, Bulliard V, Cerutti L, Cuche BA, de Castro E, Lachaize C, Langendijk-Genevaux PS, Sigrist CJ. The 20 years of PROSITE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D245–249. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Munshi S, Liljas L, Agrawal D, Olson NH, Reddy V, Fisher A, McKinney B, Schmidt T, Baker TS. Comparative studies of T = 3 and T = 4 icosahedral RNA insect viruses. Arch Virol Suppl. 1994;9:497–512. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9326-6_48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Rueckert RR. Packaging and release of the viral genome. In: Burnett RM, Chiu W, Garcea R, editors. Structural Biology of Viruses. Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Speir JA. Quasi-equivalent viruses: a paradigm for protein assemblies. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:665–675. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Daley DT, Luscombe NM, Berman HM, Thornton JM. Protein-RNA interactions: a structural analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:943–954. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.4.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khayat R, Tang L, Larson ET, Lawrence CM, Young M, Johnson JE. Structure of an archaeal virus capsid protein reveals a common ancestry to eukaryotic and bacterial viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18944–18949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506383102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia LF, Soares MR, Valente AP, Almeida FC, Oliveira AC, Gomes AM, Freitas MS, Schneemann A, Johnson JE, Silva JL. Structure of a membrane-binding domain from a non-enveloped animal virus: insights into the mechanism of membrane permeability and cellular entry. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29278–29286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Lander G, Johnson JE. Characterization of large conformational changes and autoproteolysis in the maturation of a T=4 virus capsid. J Virol. 2009;83:1126–1134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01859-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova N, Allers J, Myers J, Shamoo Y. Protein-RNA interactions: exploring binding patterns with a three-dimensional superposition analysis of high resolution structures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2746–2752. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi S, Liljas L, Cavarelli J, Bomu W, McKinney B, Reddy V, Johnson JE. The 2.8 A structure of a T = 4 animal virus and its implications for membrane translocation of RNA. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:1–10. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson NH, Baker TS, Johnson JE, Hendry DA. The three-dimensional structure of frozen-hydrated Nudaurelia capensis beta virus, a T = 4 insect virus. J Struct Biol. 1990;105:111–122. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(90)90105-l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle FM, Johnson KN, Goodman CL, McIntosh AH, Ball LA. Providence virus: a new member of the Tetraviridae that infects cultured insect cells. Virology. 2003;306:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneemann A, Marshall D. Specific encapsidation of nodavirus RNAs is mediated through the C terminus of capsid precursor protein alpha. J Virol. 1998;72:8738–8746. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8738-8746.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneemann A, Reddy V, Johnson JE. The structure and function of nodavirus particles: a paradigm for understanding chemical biology. Adv Virus Res. 1998;50:381–446. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60812-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Jordan EG. The nucleolus. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:93–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist CJ, Cerutti L, Hulo N, Gattiker A, Falquet L, Pagni M, Bairoch A, Bucher P. PROSITE: a documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Brief Bioinform. 2002;3:265–274. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe JA, Coppel RL, Brown GV, Ramasamy R, Kemp DJ, Anders RF. Identification of two integral membrane proteins of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5195–5199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe JA, Coppel RL, Day KP, Martin RK, Oduola AM, Kemp DJ, Anders RF. Structural diversity in the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface antigen 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1751–1755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow RW, Guerra CA, Noor AM, Myint HY, Hay SI. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2005;434:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature03342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speir JA, Johnson JE. Tetraviruses. In: Mahy BWJ, van Regenmortel MHV, editors. Encyclopedia of Virology. Elsevier; Oxford: 2008a. pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Speir JA, Johnson JE. Virus Particle Structure: Nonenveloped Viruses. In: Mahy BWJ, van Regenmortel MHV, editors. Virology. Elsevier; Oxford: 2008b. pp. 380–393. [Google Scholar]

- Speir JA, Munshi S, Wang G, Baker TS, Johnson JE. Structures of the native and swollen forms of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus determined by X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy. Structure. 1995;3:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00135-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Lee KK, Bothner B, Baker TS, Yeager M, Johnson JE. Dynamics and stability in maturation of a t=4 virus. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:803–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Johnson KN, Ball LA, Lin T, Yeager M, Johnson JE. The structure of pariacoto virus reveals a dodecahedral cage of duplex RNA. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:77–83. doi: 10.1038/83089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DJ, Speir JA, Reddy V, Cingolani G, Pringle FM, Ball LA, Johnson JE. Preliminary x-ray characterization of authentic Providence virus and attempts to express its coat protein gene in recombinant baculovirus. Arch Virol. 2006;151:155–165. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0637-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.J.a.J., J. E. Folding and particle assembly are disrupted by single point mutations near the autocatalytic site of Nudaurelia capensis ω virus capsid protein. Protein Sci. 2005;14:401–408. doi: 10.1110/ps.041054605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tihova M, Dryden KA, Le TV, Harvey SC, Johnson JE, Yeager M, Schneemann A. Nodavirus coat protein imposes dodecahedral RNA structure independent of nucleotide sequence and length. J Virol. 2004;78:2897–2905. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.2897-2905.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter PA, Schneemann A. Recent insights into the biology and biomedical applications of Flock House virus. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2675–2687. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8037-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Perugini MA, Yao S, Adda CG, Murphy VJ, Low A, Anders RF, Norton RS. Solution conformation, backbone dynamics and lipid interactions of the intrinsically unstructured malaria surface protein MSP2. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick A, Reddy VS, Dasgupta R, Schneemann A, Ray WJ, Jr., Rueckert RR, Johnson JE. Capsid assembly in a family of animal viruses primes an autoproteolytic maturation that depends on a single aspartic acid residue. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13680–13684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]