Abstract

Rhodopseudomonas palustris grows photoheterotrophically on aromatic compounds available in aquatic environments rich in plant-derived lignin. Benzoate degradation is regulated at the transcriptional level in R. palustris in response to anoxia and the presence of benzoate and/or benzoyl-CoA (Bz-CoA). Here, we report evidence that anaerobic benzoate catabolism in this bacterium is also regulated at the posttranslational level. In this pathway, benzoate is activated to Bz-CoA by the AMP-forming Bz-CoA synthetase (BadA) enzyme. Mass spectrometry and mutational analysis data indicate that residue Lys512 is critical to BadA activity. Acetylation of Lys512 inactivated BadA; deacetylation reactivated BadA. Likewise, 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA (HbaA) and cyclohexanecarboxyl-CoA (AliA) synthetases were also reversibly acetylated. We identified one acetyltransferase that modified BadA, Hba, and AliA in vitro. The acetyltransferase enzyme is homologous to the protein acetyltransferase (Pat) enzyme of Salmonella enterica sv Typhimurium LT2, thus we refer to it as RpPat. RpPat also modified acetyl-CoA (Ac-CoA) synthetase (Acs) from R. palustris. In vivo data indicate that at least two deacetylases reactivate BadAAc. One is SrtN (encoded by srtN, formerly rpa2524), a sirtuin-type NAD+-dependent deacetylase (O-acetyl-ADP-ribose-forming); the other deacetylase is LdaA (encoded by ldaA, for lysine deacetylase A; formerly rpa0954), an acetate-forming protein deacetylase. LdaA reactivated HbaAc and AliAAc in vitro.

INTRODUCTION

Aromatic compounds are widespread in the environment, where they are primarily derived from plant material such as lignin (Dagley, 1981). In the last century, human contamination with aromatic compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, benzene, toluene, xylene and others has become an environmental concern. The biodegradation of aromatic compounds presents unique biochemical challenges because of the high resonance energy that stabilizes benzene rings. However, many microorganisms possess the metabolic capabilities necessary for the use of these recalcitrant compounds as carbon and energy sources under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Diaz, 2004, Fuchs, 2008, Gibson & Harwood, 2002, Vaillancourt et al., 2006). Although microbes use different pathways depending on oxygen availability, all aromatic compound degradation pathways require activation of the stable aromatic ring and then subsequent ring cleavage. Under anoxic conditions,, aromatic rings tend to be activated by coenzyme A (CoA) thioesterification prior to ring modification and ring reduction steps leading to ring cleavage (Carmona et al., 2009, Fuchs, 2008). Under oxic conditions, dioxygenases destabilize the aromatic ring by hydroxylation, before they catalyze ring cleavage (Vaillancourt et al, 2006). More recently, hybrid pathways have been described that involve formation of CoA derivatives of aromatic acids, followed by ring hydroxylation by dioxygenases (Zaar et al., 2001, Zaar et al., 2004, Fuchs, 2008).

The photoheterotrophic, purple non-sulfur α-proteobacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris has one of the best-studied systems for anaerobic aromatic compound degradation (Harwood et al., 1999). When growing photosynthetically in the absence of oxygen, R. palustris converts aromatic compounds to Ac-CoA, which is then used as carbon and energy source.

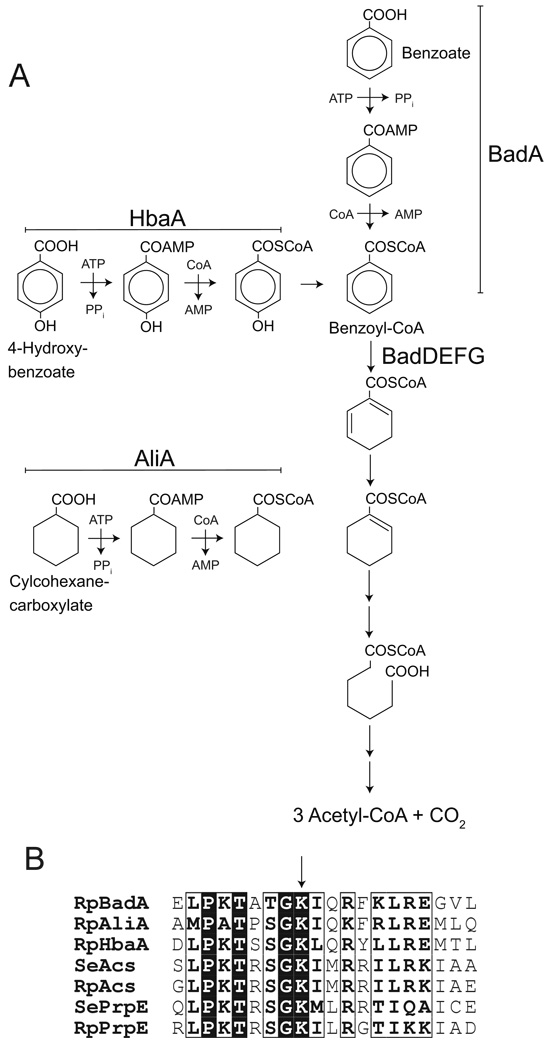

The first step in the degradation of benzoate, and the related compounds 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HBA) and cyclohexanecarboxylate (CHC), is the activation of the acid to the corresponding CoA thioester by an AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetase (Fig. 1a). R. palustris has at least three acyl-CoA synthetases with overlapping specificity; BadA primarily activates benzoate to Bz-CoA, and HbaA and AliA activate 4-HBA and CHC, respectively, to their CoA thioesters (Geissler et al., 1988, Gibson et al., 1994, Samanta & Harwood, 2005, Egland et al., 1995). In the central benzoate pathway, the aromatic ring of Bz-CoA is reduced, hydrated, and cleaved, yielding the linear compound pimeloyl-CoA, which is degraded via β-oxidation yielding Ac-CoA and CO2 (Egland et al., 1997, Harrison & Harwood, 2005). The products of HbaA and AliA (4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA and cyclohexanecarboxyl-CoA, respectively), feed into the central benzoate degradation pathway (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1. Anaerobic benzoate catabolism in R. palustris.

A. Pathways for degradation of benzoate, 4-hydroxybenzoate, and cyclohexanecarboxylate in R. palustris. BadA, benzoyl-CoA synthetase; HbaA, 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA synthetase; AliA, cyclohexanecarboxyl-CoA synthetase. Adapted from (Egland & Harwood, 1999). B. Alignment of protein sequences near C-terminal end of acyl- and aryl-CoA synthetases (residues 504-523 of BadA). Arrow indicates lysine residue that is acylated in S. enterica Acs and PrpE. Rp, R. palustris; Se, S. enterica; Acs, Ac-CoA synthetase; PrpE, propionyl-CoA synthetase. Alignment generated with ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994) and ESPript (Gouet et al., 1999).

Three transcriptional regulators control benzoate degradation in R. palustris by modulating expression of the badDEFGAB operon that encodes the O2-sensitive 4-component Bz-CoA reductase (BadDEFG), Bz-CoA synthetase (BadA) and a ferredoxin (BadB). AadR, (a homolog of E. coli Fnr), activates the transcription of the badDEFGAB operon in response to anoxia (Dispensa et al., 1992). In addition, BadR (an activator), and BadM (a repressor), respond to benzoate or Bz-CoA (Egland & Harwood, 1999, Peres & Harwood, 2006).

To date, a role for posttranslational regulation of the enzymes involved in anaerobic aromatic compound degradation has not been reported. Several groups have shown that the activity of members of the AMP-forming family of acyl-CoA synthetases in bacteria and eukaryotes is regulated by reversible acylation of the epsilon amino group (Nε) of a conserved lysine residue (Starai et al., 2002, Garrity et al., 2007, Gardner et al., 2006, Hallows et al., 2006, Schwer et al., 2006). Hence we considered the possibility that the activity of aryl-CoA synthetases BadA and HbaA, and that of the alicyclic acyl-CoA synthetase AliA, could be controlled by reversible Nε-Lys acylation.

In Salmonella enterica, the protein acyltransferase (SePat) enzyme uses Ac-CoA or propionyl-CoA (Pr-CoA) to acetylate Ac-CoA synthetase (Acs) or propionylate Pr-CoA synthetase (PrpE) (Starai & Escalante-Semerena, 2004, Garrity et al., 2007); in both cases, acylation inactivates the enzyme. The lysine residues that are acylated (K609 in Acs, K592 in PrpE) are located within the active site and are required for catalysis of the first half-reaction, in which the fatty acid and ATP react to form an acyl-AMP intermediate (Reger et al., 2007; Horswill and Escalante, 2002). Acetylated Acs (AcsAc) and propionylated PrpE (PrpEPr) are reactivated by deacylation, a reaction catalyzed by the NAD+-dependent CobB sirtuin enzyme (Starai et al., 2002, Starai et al., 2003, Garrity et al., 2007, Hoff et al., 2006).

The SePat protein is a member of the yeast Gcn-5 family of acyltransferases (a.k.a. GNATs, pfam 00583) (Vetting et al., 2005a). SePat is an unusual GNAT in that it contains two distinct domains. The N-terminal domain (~791 aa) is similar to an ADP-forming acyl-CoA synthetase, but lacks the catalytic histidine residue critical for the activity of these enzymes. The C-terminal domain of the SePat enzyme (~95 aa) is homologous to the catalytic domain of GNATs (Starai & Escalante-Semerena, 2004, Vetting et al., 2005b).

In the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis, Ac-CoA synthetase (BsAcsA) is also regulated by acetylation (Gardner et al., 2006). While acetylation of BsAcsA has the same effect as in S. enterica, the posttranslational modification system in B. subtilis is somewhat different. In the latter, BsAcsA is acetylated by BsAcuA, another GNAT-like protein that is much smaller than SePat, and contains only the yGcn-5 acetyltransferase domain (Gardner et al., 2006, Gardner & Escalante-Semerena, 2008). B. subtilis has two different deacetylases capable of reactivating BsAcsA. One of these, BsAcuC, uses a Zn(II) ion to hydrolyze the acetyl moiety, generating free acetate (Gardner et al., 2006, Nielsen et al., 2005). The other deacetylase, SrtN, is a sirtuin-type deacetylase similar to CobB in S. enterica (Gardner & Escalante-Semerena, 2009, Denu, 2005).

There are many AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetases found in all domains of life, including at least 40 in R. palustris, which activate a wide range of fatty and aromatic acids for catabolic and biosynthetic purposes (Larimer et al., 2004).

In this paper, we report in vivo and in vitro evidence that the enzymatic activity of RpBadA, RpHbaA and RpAliA is negatively affected by acetylation, that a single acetylation event renders the enzymes inactive, that the site of acetylation is a catalytically important, conserved Lys residue in this family of enzymes, and that reactivation of the modified enzyme is achieved upon deacetylation. Thus, in R. palustris, the degradation of aromatic compounds is regulated at the posttranslational and transcriptional level. Our findings raise the possibility that Nε-Lys acetylation is also important in other anaerobic aromatic degrading microbes.

RESULTS

AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetases involved in anaerobic benzoate catabolism in R. palustris have a conserved lysine residue, which in other proteins is the site of acylation

An alignment of the protein sequences of the R. palustris acyl-CoA synthetases BadA, HbaA and AliA with S. enterica Acs and PrpE, shows that all three R. palustris acyl-CoA synthetases contain the catalytically important lysine residue that is modified in SeAcs and SePrpE (Fig. 1b). From the crystal structure of the Bz-CoA synthetase of Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 (61% identical to BadA, Protein Data Base code 2V7B), we inferred that residue K512 in BadA (K520 in B. xenovorans Bz-CoA synthetase) lies within the C-terminal domain of the protein (Bains & Boulanger, 2007), and hypothesized it could be modified by acetylation.

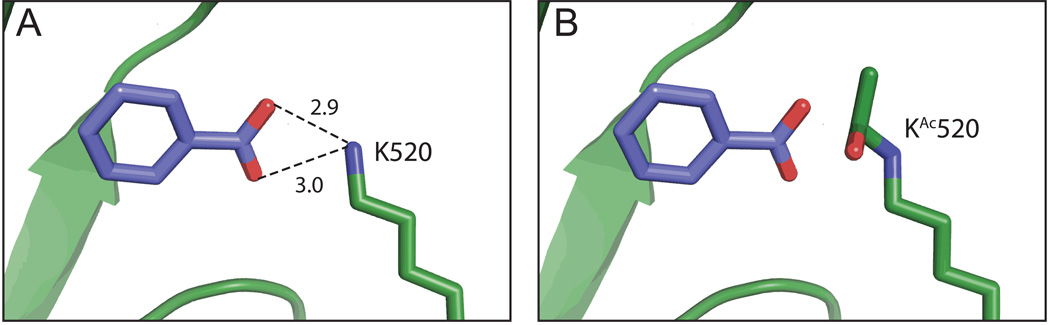

The crystal structure of B. xenovorans Bz-CoA synthetase shows that residue K520 is part of the lid for the benzoate-binding pocket, and that this residue forms two hydrogen bonds with the carboxylate group of benzoate (Fig. 2a) (Bains & Boulanger, 2007). We modeled an acetylated lysine residue at position 520 using the Pymol molecular graphics software package (http://www.pymol.org), and, as shown in figure 2b, the presence of the acetyl moiety would block the interactions between the ε-amino group of K520 and the carboxylate group of benzoate (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Modeling the effect of Nε-Lys acetylation on the structure of benzoyl-CoA synthetase from B. xenovorans LB400.

A.The crystal structure of Bz-CoA synthetase from B. xenovorans LB400 (PDB 2V7B) was reported with benzoate (shown in purple) in the active site (Bains & Boulanger, 2007). A close-up view of this region shows the hydrogen bonds formed between the oxygen atoms of benzoate (red) and the epsilon amino group of residue Lys520 (blue), with bond distances indicated. B. An acetylated Lys residue was modeled in lieu of Lys520 using Pymol (http://www.pymol.org). Acetylation of Lys520 suggests the loss of hydrogen bonding between the epsilon amino group of Lys520 and the carboxylic acid oxygen atoms of benzoate.

Genes of R. palustris encoding a reversible Nε-Lys acetylation system

In R. palustris, the genes encoding the BadA, HbaA and AliA acyl-CoA synthetases are located within a 24-gene cluster dedicated to aromatic compound transport and degradation (Egland et al., 1997). This gene cluster contains badL, whose product is homologous to members of the yGcn-5 acetyltransferase family of enzymes (Vetting, et al., 2005a). We investigated the possibility that BadL could modify BadA, Hba, and AliA. For this purpose, we isolated recombinant BadL protein to homogeneity from an E. coli overexpression strain, and used it in our in vitro protein acetylation assay. BadL did not modify BadA, HbaA or AliA under the conditions of our assay (data not shown).Additional bioinformatics analysis of the R. palustris genome identified a homolog of the S. enterica pat gene (Table 1), but did not identify a homolog of the acuA gene of B. subtilis. We did find, however, a gene homologous to the S. enterica cobB gene, which encodes a NAD+-dependent deacetylase sirtuin (Tsang & Escalante-Semerena, 1998), and a Zn-dependent lysine deacetylase homologous to the B. subtilis acuC gene. Hereafter we refer to the putative sirtuin-encoding R. palustris gene as srtN, and the putative Zn-dependent deacetylase as ldaA (for lysine deacetylase protein A, Table 1). We investigated the possibility that the putative R. palustris Pat, LdaA and SrtN proteins were involved in anaerobic benzoate catabolism in R. palustris.

Table 1.

Similarity of R. palustris proteins to homologs in S. enterica LT2 and B. subtilis SMY

|

R. palustris gene |

Protein name |

Predicted function |

Homology to S. entericaa |

Homology to B. subtilis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpa4240 | Pat | acyltransferase | 37/55 | NAb |

| rpa0954 | LdaAc | deacetylase | NA | 33/48 |

| rpa2524 | SrtNd | deacetylase | 35/49 | 39/49 |

Homology listed as percent identity/percent similarity of protein sequences.

NA, not applicable because there is not a homolog in this species.

LdaA is homologous to AcuC in B. subtilis SMY.

SrtN is homologous to CobB in S. enterica sv Typhimurium LT2.

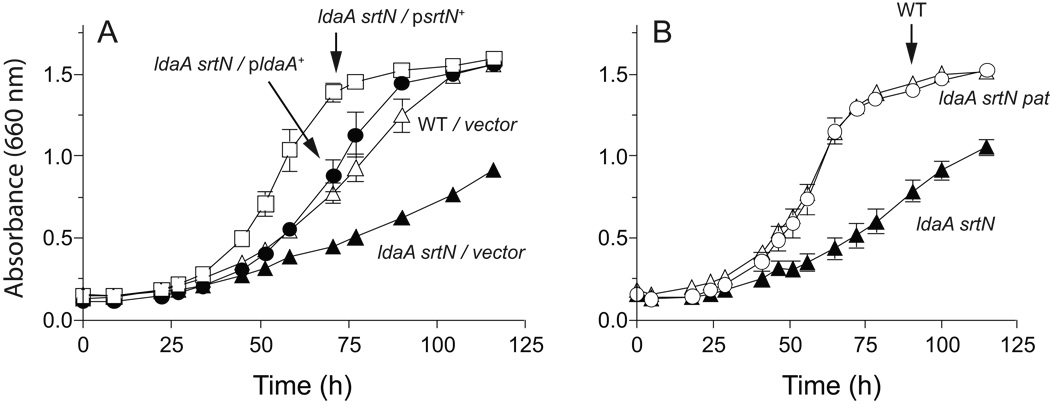

In vivo evidence that RpPat, RpLdaA, and RpSrtN modulate BadA activity

To determine whether the logic of reversible Nε-Lys acetylation systems found in other bacteria also applied to R. palustris, we constructed in-frame deletions of ldaA, srtN, and pat in this bacterium. We predicted that inactivation of the deacetylase genes would result in irreversible acetylation, thus inactivation, of the acyl-CoA synthetases we were testing. Consequently R. palustris protein deacetylase-deficient strains would not grow on aromatic substrates such as benzoate. Although we did not observe significant growth defects on benzoate when either ldaA or srtN was deleted individually (not shown), there was a growth defect when both putative deacetylase genes were inactivated (Fig. 3). Growth on benzoate was restored when either ldaA or srtN was supplied in trans, suggesting that both deacetylases affect growth on benzoate in vivo (Fig. 3a). This growth defect was specific to growth on aromatic and alicyclic compounds, as we saw no defect on other carbon sources such as malonate (Fig. S1). If the observed phenotypes were caused by modification of the synthetases, and RpPat modified these enzymes, we reasoned that deletion of the putative RpPat acetyltransferase would restore anaerobic benzoate catabolism in the ldaA srtN pat strain. Growth of the ldaA srtN pat strain was reproducibly better than the ldaA srtN strain (Fig. 3b), although on some occasions the ldaA srtN pat strain exhibited a slight lag compared to the wild type.

Figure 3. Photoheterotrophic growth of R. palustris on benzoate.

(A) Growth behavior of the R. palustris ΔldaA ΔsrtN strain carrying a plasmid encoding a wild-type allele of ldaA or srtN. Data points are averages of three replicates, and error bars represent standard deviations. Open triangles, wild type (CGA009) harboring plasmid pBBR1MCS-2 as a vector control; filled triangles, strain JE11636 (ldaA srtN / pBBR1MCS-2); circles, strain JE11637 (ldaA srtN / pRpLDAA4); squares, strain JE11638 (ldaA srtN / pRpSRTN4). (B) Growth behavior of the R. palustris ΔldaA ΔsrtN Δpat strain (open circles) compared to the wild type (open triangles) and the ΔldaA ΔsrtN strain (filled triangles). Optical density was monitored during photosynthetic growth on 3 mM benzoate

To determine the extent of acetylation of BadA, we partially purified an H10-tagged copy of BadA from each strain (wild type, ldaA srtN, and ldA srtN pat) grown to full density photosynthetically on benzoate. The activity of BadA was measured after incubation with just NAD+, as a control to determine baseline activity, and after deacetylation with the CobB deacetylase from S. enterica; as seen in Table 2, SeCobB efficiently deacetylated. BadA purified from the wild type strain was equally active before and after incubation with SeCobB and NAD+, suggesting that the extent of acetylation of BadA was negligible. In the ldaA srtN strain, however, the activity of BadA increased 12-fold after incubation with SeCobB and NAD+, indicating that the majority of BadA was acetylated in this strain. Similarly, BadA purified from the ldaA srtN pat strain was 8-fold more active after incubation with SeCobB and NAD+. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the growth defect observed in the ldaA srtN strain on benzoate was most likely due to nearly complete acetylation of BadA. Deletion of pat in the ldaA srtN background improved growth on benzoate, but, at least during stationary phase, it appeared that there might be another acetyltransferase in R. palustris that could acetylate BadA.

Table 2.

Activity of BadA partially purified fromR. palustris

| Strain | Genotype | Pre-incubation with: | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD+a | SeCobB + NAD+ | ||

| JE13049 | WT / pRpBADA4b | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 |

| JE11639 | ldaA srtN / pRpBADA4 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| JE13050 | ldaA srtN pat / pRpBADA4 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

Each measurement was performed in triplicate; the experiment was performed twice.

Enzyme activity reported as µmol AMP min−1 mg(BadA)−1

badA+ cloned into pBBR1MCS-2

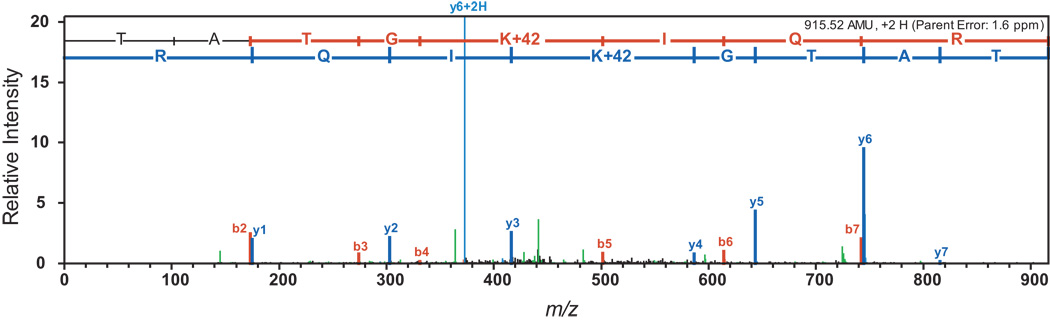

In vivo, BadA is acetylated at residue K512 during photoheterotrophic growth on benzoate

To determine the location of the site of modification in BadA, the latter was isolated from an ldaA srtN / pRpBADA4 (H10-BadA) strain grown photosynthetically on benzoate. We used nickel affinity chromatography to isolate H10-BadA, which was subjected to trypsin digestion, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry. Individual sequence determination of these peptides using mass spectrometric techniques revealed that residue K512 was acetylated (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Residue K512 of BadA is the site of acetylation.

LC/MS-MS analysis of H10-BadA protein purified from R. palustris strain JE11639 (ldaA srtN / pRpBADA4) grown photosynthetically on benzoate (3 mM). MS/MS spectrum of the 915.52 amu tryptic peptide, where peaks in red indicate b series m/z (predicted fragment ion masses of TATGKAcIQR with the charge on the NH2-terminal amino acid), and blue peaks indicate y series m/z (predicted fragment ion masses of TATGKAcIQR with the charge on the COOH-terminal amino acid). These ion series confirm that the sequence of the 915.52 amu peptide as TATGKAcIQR, which corresponds to the predicted acetylation site of Lys512.

Is BadA benzoylated or acetylated in vivo?

As mentioned above, the activity of Ac-CoA synthetase is controlled by acetylation (Starai et al., 2002), while the activity of Pr-CoA synthetase is controlled by propionylation (Garrity et al., 2007). In light of this information, we investigated the possibility that BadA, which generates Bz-CoA, was modified by benzoylation. To increase the likelihood of detecting benzoylation we increased the intracellular Bz-CoA concentration by inactivation of the badF gene, which encodes one subunit of Bz-CoA reductase (Egland et al., 1997). For this purpose, we constructed strain JE12146 [badF ldaA srtN / pRpBADA4 (H10-BadA)], which we grew on PM medium containing succinate (10 mM) and benzoate (3 mM). Mass spectrometric analysis of H10-BadA isolated from strain JE12146 resulted in a nearly identical fragmentation pattern as the one shown in Fig. 4, indicating that, in vivo, BadA was acetylated, not benzoylated.

In vitro, Rp Pat acetylates and inactivates acyl-CoA synthetases BadA, HbaA, and AliA

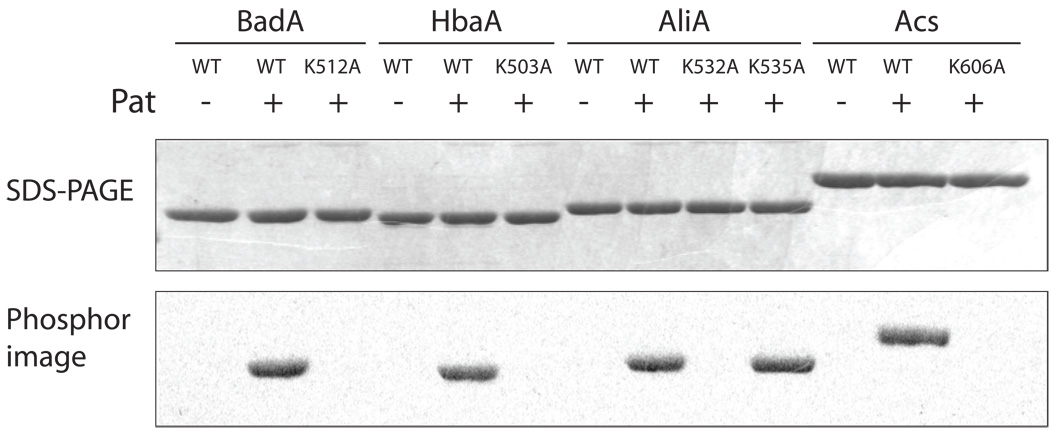

We confirmed that RpPat directly acetylated acyl-CoA synthetases by incubating purified Pat with [14C-1]-Ac-CoA and either BadA, HbaA, AliA or Acs from R. palustris (Fig. 5). Based on data obtained in other systems, we expected RpAcs to serve as positive control for RpPat activity. In each case, the labeled acetyl group was transferred to the CoA synthetase only when RpPat was present in the reaction mixture. RpPat did not acetylate a variant of BadA with a K512A substitution (BadAK512A) (Fig. 5), indicating that BadA was modified once, and that residue K512 was the site of acetylation. Similarly, variants HbaAK503A and AcsK606A were not acetylated by RpPat, which suggested that these lysine residues were the only sites of acetylation in HbaA and Acs, respectively (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Acetylation of BadA, HbaA, AliA, and Acs proteins using [14C-1]-Ac-CoA.

Either wild-type (WT) or Lys-to-Ala variants of CoA synthetases were incubated with [14C-1]-Ac-CoA with or without RpPat. Top panel shows SDS-PAGE of acetylation reactions; lower panel shows the phosphor image of the same gel.

Unlike other acyl-CoA synthetases we have investigated, AliA contains a second lysine residue at position K535 that is three residues away from the presumed acetylation site (K532) (Fig. 1b). We tested acetylation of AliAK532A and AliAK535A variants, and found that the AliAK532A protein was not acetylated, demonstrating that residue K532 was the single site of acetylation (Fig. 5). These acetylated lysine residues are homologous to the previously reported sites of acylation in S. enterica Acs and PrpE proteins (indicated with an arrow in Fig. 1b) (Starai et al., 2002, Garrity et al., 2007).

Acetylation dramatically affected the activity of all acyl-CoA synthetases tested. Each acyl-CoA synthetase was pre-incubated with RpPat and either CoA, as a negative control, or Ac-CoA, and the activity of the acyl-CoA synthetase was measured spectrophotometrically. Upon acetylation, the activity of BadAAc decreased to <1% of that of BadAWT, and was comparable to that of the BadAK512A variant (Table 3). The activities of HbaA, AliA, and Acs all decreased below the limit of detection after incubation with RpPat and Ac-CoA. K-to-A substitutions at the acetylation sites of HbaA, AliA and Acs resulted in a decrease of activity to <3% of wild-type activity (Table 3), demonstrating that these lysine residues were crucial for activity.

Table 3.

CoA synthetase enzyme activity

| Pre-incubation with: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| R. palustris enzyme | Substrate | Pat + CoAa | Pat + AcCoA |

| BadA | benzoate | 8.1 ± 0.3 | 0.06 ± 0.0 |

| BadAK512A | benzoate | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.05 ± 0.0 |

| HbaA | 4-hydroxybenzoate | 2.3 ± 0.1 | BLDb |

| HbaAK503A | 4-hydroxybenzoate | BLD | BLD |

| AliA | cyclohexanecarboxylate | 10.1 ± 0.5 | BLD |

| AliAK532A | cyclohexanecarboxylate | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.0 |

| AliAK535A | cyclohexanecarboxylate | 9.6 ± 0.4 | BLD |

| Acs | acetate | 12.7 ± 0.3 | BLD |

| AcsK606A | acetate | BLD | BLD |

Enzyme activity reported as µmol AMP min−1 mg−1.

BLD: below the limit of detection.

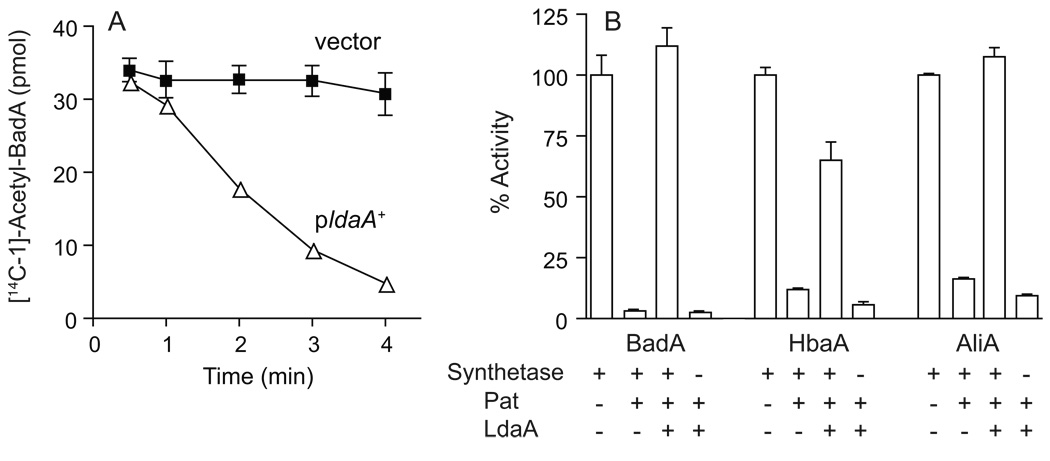

LdaA deacetylates and reactivates acyl-CoA synthetases BadA, HbaA, and AliA

Attempts to purify LdaA were met with limited success due to poor solubility of the protein. However, enough protein was present in cell-free extracts enriched for LdaA to demonstrate protein deacetylase activity. This information was obtained after the incubation of cell-free extracts of strain JE11959 (E. coli MG1655 ΔcobB / pRpLDAA1 ldaA+) with [14C]-acetyl-BadA. Within five minutes of incubation, the levels of acetylation of BadA were below the limit of detection (>90% deacetylation), compared with no substantial deacetylation using cell-free extracts from a strain containing the empty cloning vector (JE11958) (Fig. 6a). We also asked if deacetylation of acyl-CoA synthetases would restore their activity. We incubated BadA, HbaA and AliA with RpPat and unlabeled acetyl-CoA. After incubation, the reaction mixtures were incubated with cell-free extracts from strain JE11959 (enriched for LdaA) or JE11958 (devoid of LdaA). The activity of BadA and AliA was restored to levels observed before acetylation, and HbaA activity was restored to 65% of its unacetylated activity under the conditions of our experiment. These results demonstrated that deacetylation by LdaA reactivated BadA, HbaA and AliA.

Figure 6. Deacetylation of BadA, HbaA and AliA using LdaA in cell lysates.

A.[14C]-BadAAc protein was incubated with cell lysates of E. coli harboring either plasmid pRpLDAA1 (triangles) or cloning vector (squares). Aliquots of the reaction were quenched at each time point, resolved using SDS-PAGE, and quantified by phosphor imaging. Data represent averages and standard deviations of three reactions. B. BadA, HbaA and AliA activity is restored upon deacetylation. Each acyl-CoA synthetase (or no-synthetase control) was pre-incubated with or without Pat and acetyl-CoA, and the acetylation reaction was stopped by buffer exchange. Cell-free extracts of strains JE11958 (empty vector) or JE11959 (pRpLDAA1) were added to the reaction, and acyl-CoA synthetase activity was measured in triplicate.

Purified RpSrtN did not deacetylate any of the acetylated acyl-CoA synthetases, even with the addition of the S. enterica nicotinamidase enzyme PncA, which has been used to diminish inhibition by the byproduct nicotinamide (Garrity et al., 2007). However, the S. enterica CobB sirtuin deacetylated [14C]-acetyl-BadA in vitro and restored enzyme activity. We also tested whether E. coli cell lysates enriched in RpSrtN would deacetylate BadA; we did not observe any deacetylation. At present, it is unclear why RpSrtN was inactive in vitro.

DISCUSSION

Anaerobic benzoate catabolism in R. palustris is under the control of reversible Nε-Lys acetylation

We have reported here the first evidence of reversible Nε-Lys acetylation control of acyl-CoA synthetases in an α-proteobacterium, and, to our knowledge, the first posttranslational regulation of aryl-CoA synthetases. We identified one protein acetyltransferase enzyme in R. palustris (RpPat) that effectively modifies three AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetases involved in aromatic and alicylic acid activation. The fact that a single modification of a conserved Lys residue close to the C terminus of the protein is sufficient to render all three >95% inactive, reflects the importance of the Lys residue on the function of BadA, HbaA, and AliA.

Two cognate protein deacetylases (i.e. RpLdaA, RpSrtN) appear to work in concert with RpPat to modulate the activity of BadA, HbaA, and AliA. It is unclear, how RpLdaA and RpSrtN specifically contribute to aromatic acid degradation in this bacterium. However, the absence of both deacetylases has a clear impact on growth on benzoate, and, as shown in table 2, when BadA is purified from a ldaA srtN strain, it is mostly in the acetylated state.

The lack of activity of RpSrtN was unexpected, since sirtuins from other sources (e.g. SeCobB) are active under the same conditions we tested. An explanation for this observation requires further investigation.

Are other protein acetyltransferases involved?

Our data clearly show that RpPat can efficiently inactivate BadA, HbaA and AliA (and acetyl-CoA synthetase) in vitro, and that deletion of pat in an ldaA srtN strain restores growth on benzoate to near wild type levels. However, BadA is still partially acetylated in a pat strain, strongly suggesting that one or more yet-to-be-identified acetyltransferases with Pat-like activity exist in R. palustris.

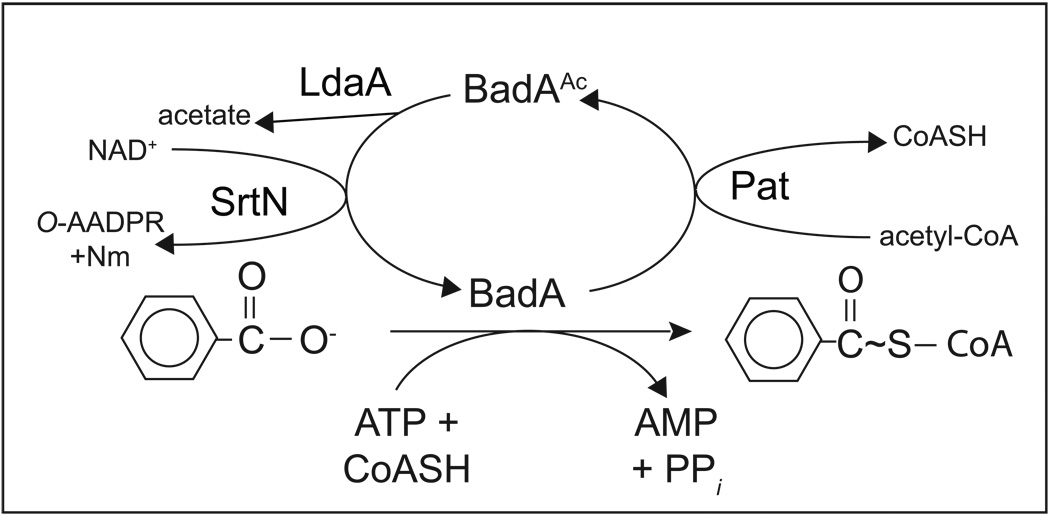

A model for the posttranslational control of acyl-CoA synthetases in R. palustris

The scheme in figure 7 summarizes what we know about the control of Bz-CoA synthetase (BadA) activity by Nε-Lys acetylation system of this bacterium. Based on our data, we extrapolate that Hba and AliA activities are controlled in a similar manner. This work has unveiled what is likely to be a complex system for metabolic control in R. palustris. We suspect there are many other proteins under reversible Nε-Lys acetylation control in this bacterium.

Figure 7. Proposed model for the posttranslational regulation of BadA.

In this model, BadA protein is acetylated by RpPat (and possibly by other unknown acetyltransferases) at residue Lys512, rendering it inactive. BadA is reactivated by the deacetylases LdaA and SrtN. LdaA uses water to hydrolyze the acetyl group, releasing acetate, whereas SrtN uses NAD+ as a substrate, generating O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (O-AADPR) and nicotinamide (Nm). Regulation of HbaA and AliA is predicted to be similar to that for BadA. CoASH, coenzyme A; PPi, pyrophosphate.

Physiological role of acyl-CoA synthetase regulation

BadA, HbaA, and AliA are members of the AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetase family of enzymes, and each of these enzymes catalyzes the first step in benzoate, 4-HBA, and CHC degradation, respectively. Each enzyme consumes ATP and CoA to convert the substrate to the corresponding CoA thioester. The next step in benzoate degradation is catalyzed by Bz-CoA reductase, which, in the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica, uses 2 ATP to drive the transfer of electrons from ferredoxin to Bz-CoA (Boll et al., 1997, Boll & Fuchs, 1995). Since the first two steps of aromatic acid degradation are energetically expensive, we hypothesize that Nε-Lys acetylation is a mechanism that prevents uncontrolled Ac-CoA synthesis, which, if it happened, would consume large amounts of ATP and free CoA, and might lead to growth arrest. The fact that srtN+ provided in trans restored growth of an ldaA srtN strain on aromatic compounds, suggests a link between the reactivation of acetylated acyl-CoA synthetases and a physiological state where NAD+ is high. Such a condition may signal a need to catabolize benzoate to generate carbon and reducing power for growth. Thus, control of protein function by acetylation may be an important system for maintaining CoA and redox homeostasis with a direct link to the carbon and energy status of the cell.

Implications of the acetylation of acyl-CoA synthetases

It has been suggested that BadR, a transcriptional activator of the badDEFGAB operon, may sense Bz-CoA, rather than benzoate (Egland & Harwood, 1999). Indeed, in the denitrifying bacterium Azoarcus sp. strain CIB, the genes encoding enzymes involved in the anaerobic degradation of benzoate are organized in a single operon that is regulated by the BzdR repressor, which responds to Bz-CoA (Barragan et al., 2005). Our data showing that Bz-CoA synthetase (BadA) activity is regulated by acetylation, suggests that this posttranslational modification is important for modulating the concentration of Bz-CoA in cells. This may, in turn, affect transcriptional regulation, providing additional inputs into the regulatory network.

Extent of CoA synthetase regulation by reversible Nε-Lys acylation

Previous work has shown that AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetases that activate short chain fatty acids, such as acetate and propionate, are regulated by reversible Nε-Lys acetylation and propionylation, respectively, in bacteria and eukaryotes (Starai et al., 2002, Garrity et al., 2007, Gardner et al., 2006, Schwer et al., 2006, Hallows et al., 2006). The AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetases are a large and diverse group of enzymes that can activate diverse substrates, including short-, medium-, and long-chain fatty acids, dicarboxylic acids, aromatic acids, and substituted aromatic acids such as 4-chlorobenzoate. R. palustris, which has unusually broad metabolic capabilities, has at least 40 genes annotated to encode putative AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetases (Larimer et al., 2004). Many of these enzymes contain the conserved Lys residue that is acetylated in Acs (Lys606 in RpAcs), which is not surprising since it appears to play a role in substrate binding (Reger et al., 2007, Conti et al., 1997, May et al., 2002, Nakatsu et al., 2006). It will be interesting to determine the extent of regulation of acyl-CoA synthetases by Nε-Lys acetylation.

In summary, the results presented here demonstrate that, in the photosynthetic α-proteobacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris, the activities of acetyl-CoA synthetase, two aryl-CoA synthetases, and one alicyclic-CoA synthetase are regulated at the posttranslational level by reversible acetylation of the epsilon amino group of a conserved Lys residue. We have identified three enzymes (one acetyltransferase, and two deacetylases) that orchestrate the control of the above-mentioned synthetases, and we hypothesize that there is at least one more acetyltransferase involved. The modifying/demodifying enzymes are likely a regulatory system that is finely tuned to CoA (carbon status) and redox (energy status) homeostasis in this bacterium. In view of these results and the widespread participation of AMP-forming acyl-CoA synthetases in aromatic acid degradation it seems possible that posttranslational modification by Nε-Lys acetylation constitutes an common and previously overlooked mechanism for regulating these pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, chemicals

All strains used in this study are listed in Table S1, and a list of plasmids can be found in Table S2. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in lysogeny broth (LB, Difco) (Bertani, 1951, Bertani, 2004). All R. palustris strains are derivatives of R. palustris CGA009 (Larimer et al., 2004) and were cultured at 30 °C in YP rich medium (20 g yeast extract L−1, 20 g peptone L−1), or defined basal photosynthetic medium [PM, (Kim & Harwood, 1991)] supplemented with NaHCO3 (10 mM) and either succinate (10 mM), malonate (10 mM), benzoate (3 mM), 4-hydroxybenzoate (3 mM) or cyclohexanecarboxylate (3 mM). For growth curves, three- or four-days old, aerobically grown cultures of R. palustris were grown in YP medium supplemented with kanamycin where appropriate. Cultures were diluted (1:10) in triplicate into 5 ml of anoxic PM supplemented with the appropriate carbon source and kanamycin; all manipulations were performed in Balch tubes (Balch & Wolfe, 1976). Tubes were incubated at 30 °C in light without shaking. Cell density was monitored at 660 nm using a Manostat Spec20D; each growth curve was repeated at least three times. When used, ampicillin was at 100 µg ml−1 unless otherwise indicated, chloramphenicol was at 20 µg ml−1, gentamicin was at 100 µg ml−1, and kanamycin was at 50 µg ml−1 (E. coli) or 75 µg ml−1 (R. palustris). Radiolabeled [14C-1]-Ac-CoA (54 mCi/mmol) was purchased from Moravek, and all other chemicals were obtained from Sigma.

Molecular techniques

DNA manipulations were performed using standard techniques (Ausubel, 1989). Restriction endonucleases were purchased from Fermentas. DNA was amplified using PfuUltra II Fusion DNA polymerase (Stratagene), and site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange kit from Stratagene unless otherwise noted. Plasmid DNA was purified using the Wizard Plus SV Miniprep kit (Promega) and PCR products were purified using the QiaQuick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed using BigDye (ABI PRISM) protocols, and sequencing reactions were resolved and analyzed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center. Oligonucleotide primer sequences are listed in Table S3 (Supplementary Material).

Construction of gene deletions in R. palustris

In-frame deletions of R. palustris pat and badF were generated using described protocols (Schafer et al., 1994). A DNA fragment was amplified using overlap extension PCR (Horton et al., 1993) that contained 1 kb of upstream DNA fused in-frame to 1 kb of downstream DNA. The PCR product was cut with EcoRI and HindIII enzymes, ligated into plasmid pK18mobsacB (Schafer et al., 1994), and transformed into E. coli strain DH5α. The resulting plasmid was purified and electroporated into R. palustris to generate a strain in which the plasmid had integrated into the chromosome. A kanamycin resistant colony was used to inoculate 5 ml of YP + kanamycin medium, grown aerobically at 30 °C, and transferred to 50 ml of anaerobic PM + succinate (10 mM) + sucrose (10%, w/v), without antibiotic, to select for loss of the integrated plasmid. This culture was diluted and plated on PM + succinate (10 mM). Kanamycin sensitive colonies were screened by PCR for deletion of the gene; the presence of the deletion was established by DNA sequencing.

Deletions of srtN and ldaA were constructed similarly, except that plasmid pJQ200SK, which encodes gentamicin resistance (Quandt & Hynes, 1993), was used instead of plasmid pK18mobsacB. To delete the R. palustris srtN gene, a fusion of 1 kb of upstream DNA and 1 kb of downstream DNA was ligated into plasmid pJQ200SK using restriction enzymes SacI and BamHI; SacI and NotI were used for the ldaA deletion plasmid. The resulting plasmids were electroporated into R. palustris, and gentamicin resistant colonies were streaked on PM + succinate (10 mM) plates containing sucrose (10%, w/v). Gentamicin-sensitive colonies arising on these plates were screened by PCR for the deletion, which was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Plasmids used for protein overproduction

The badA, hbaA and aliA genes were amplified from R. palustris genomic DNA using the primers listed in Table S2 (Supplementary Material), and were cloned into the NdeI and BamHI sites of plasmid pET-16b. Each protein was fused to an N-terminal H10 tag. The badA gene was also cloned into the NdeI and EcoRI sites of plasmid pTEV5 (Rocco et al., 2008), which directed the synthesis of BadA with an N-terminal H6 tag, cleavable by TEV protease. The acs gene (formerly rpa0211) was cloned into the NheI and EcoRI sites of pTEV5. Plasmids directing the synthesis of variants BadAK512A and AliAK532A were generated from the pET-16b vectors using site-directed mutagenesis. Alleles encoding the remaining variants (AcsK606A, HbaAK503A, and AliAK535A) were constructed by amplification using overlap extension PCR with the mutagenesis and cloning primers, and the resulting products were ligated into plasmids pTEV5 (AcsK606A) or pET-16b (HbaAK503A and AliAK535A). The presence of mutations was confirmed by DNA sequencing. R. palustris pat was amplified from genomic DNA, and was cloned into the KpnI and HindIII sites of plasmid pKLD66 (Rocco et al., 2008). The fifth codon of pat is a relatively rare arginine codon in E. coli (CGA), thus it was changed to the more common codon CGT using site-directed mutagenesis. The resulting plasmid, pRpPAT2, expressed RpPat with sequential H6 and MBP tags at the N-terminus, both of which were cleavable by TEV protease. The srtN gene was amplified from R. palustris genomic DNA and cloned into the NdeI and XhoI sites of pET-24b, which expressed RpSrtN with a C-terminal H6 tag.

Plasmids for expression in R. palustris

The R. palustris ldaA+ gene was amplified and cloned into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of plasmid pBBR1MCS-2 (Kovach et al., 1995) to generate plasmid pRpLDAA4. The R. palustris srtN gene was amplified with an optimized ribosome-binding site for E. coli, and was cloned into the KpnI and HindIII sites of plasmid pBBR1MCS-2 to generate plasmid pRpSRTN4. The R. palustris badA+ gene was amplified from plasmid pRpBADA1, and cloned into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of plasmid pBBR1MCS-2 to generate plasmid pRpBADA4; the latter directed the synthesis of H10-BadA.

Plasmid for expression in E. coli

The R. palustris ldaA+ gene was amplified with an optimized ribosome-binding site for E. coli, and was cloned into the XbaI and HindIII sites of plasmid pBAD30 (Guzman et al., 1995) to generate plasmid pRpLDAA1, which expressed ldaA+ under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter. The R. palustris srtN+ gene was cloned in a similar manner, except that the gene was cloned into the KpnI and HindIII sites of pBAD30.

Protein purification

pET-16b vectors containing badA+, hbaA+, or aliA+ were transformed into a Δpat derivative of strain of E. coli C41λ(DE3) (Miroux & Walker, 1996)to prevent acetylation prior to purification. The resulting strains were grown until early stationary phase and sub-cultured (1:100) into two liters of LB supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg ml−1). Cultures were grown with shaking to an OD600 ~0.6, and protein expression was induced with isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.5 mM). Cultures were grown overnight at 16 °C, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,500 × g for 12 min in a Beckman Coulter Avanti J-20 XOI refrigerated centrifuge with a JLA-8.1000 rotor. Cell pellets were re-suspended in 30 ml of buffer ABadA [sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0), NaCl (300 mM), imidazole (5 mM)] containing 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme and 1 mg ml−1 DNaseI. Cells were disrupted using a French pressure cell (Spectronic instruments) at 1.26 kPa (2–3 times) and debris was removed by centrifugation at 39,000 × g for 30 min. Proteins were purified by Ni-affinity purification using an ÄKTA FPLC Purifier system (Amersham Biosciences) equipped with a 1-ml HisTrap HP column. The column was equilibrated with buffer A before loading the filtered cell-free extract, and then washed with 10 ml of Buffer ABadA, followed by 15 ml of 4% buffer BBadA [sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0), NaCl (300 mM), imidazole (250 mM)]. Proteins were desorbed from the resin using a 15-ml linear gradient to 100% B. Each protein was dialyzed ≥3 h against buffer 1 [Tris-Cl (50 mM, pH 7.5, at 4 °C), NaCl (100 mM), EDTA (1 mM), glycerol (20%, v/v)] and then buffer 2 [Tris-Cl (50 mM, pH 7.5, at 4 °C), NaCl (100 mM), glycerol (20%, v/v)], before drop freezing into liquid N2. Protein concentrations were determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm. The molar extinction coefficients used to calculate protein concentrations were 134,420 M-1 cm-1 for RpAcs, 59,600 M-1 cm-1 for AliA, 65,430 M-1 cm−1 for BadA, 69,840 M−1 cm−1 for HbaA, and 68,560 for RpPat.

R. palustris Ac-CoA synthetase (RpAcs) and untagged BadA

pTEV5 vectors expressing RpH6-Acs and H6-BadA were transformed into a Δpat strain of E. coli C41λ(DE3) to prevent acetylation prior to purification. Conditions used for the overproduction and purification of RpH6-Acs and H6-BadA were similar to those described above. The H6 tag was removed using H6-TEV protease (Blommel & Fox, 2007) as described (Garrity et al., 2007), and RpAcs and BadA were purified away from the tag and H6-TEV protease by passage over a 1 ml HisTrap HP column.

R. palustris protein acety transferase (RpPat)

Plasmid pRpPAT2 was transformed into E. coli BL21λ(DE3) / pLysS and expressed in four liters of LB + ampicillin (200 µg ml−1) + chloramphenicol (20 µg ml−1). After induction with IPTG (0.5 mM), the temperature was reduced to 28 °C and the cultures were allowed to grow overnight with shaking. RpH6-MBP-Pat was purified as described above, with minor adjustments, and the His6-MBP tag was removed with H6-TEV protease. For the first purification, buffer APat contained sodium phosphate (50 mM, pH 7.5), NaCl (500 mM), imidazole (20 mM) and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP, 0.5 mM), and buffer BPat was the same as buffer APat except that the imidazole concentration was increased to 500 mM. For the second purification step (removal of the tag and H6-TEV protease) the same buffers were used, except imidazole was omitted from buffer APat. Purified Pat was dialyzed three times against successively lower NaCl concentrations, into storage bufferPat [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES, 50 mM, pH 7.5), NaCl (150 mM), glycerol (20%, v/v)] and drop frozen into liquid N2.

R. palustris sirtuin deacetylase ( Rp SrtN)

Plasmid pRpSRTN6 was transformed into E. coli C41λ(DE3) and expressed in 4 L of LB + kanamycin, and ZnSO4 (50 µM). After induction with IPTG (0.5 mM), the temperature was reduced to 28 °C and the cultures were allowed to grow overnight with shaking. RpSrtN was purified using Ni-affinity chromotography as described above for BadA, HbaA and Alia, except that 0.5 mM TCEP was added to the purification buffers, and 5 mM DTT was included in the storage buffers.

S. enterica CobB sirtuin deacetylase and PncA nicotinamidase

Plasmid pCOBB33, expressing S. enterica CobB fused to an N-terminal chitin binding domain tag, was transformed into E. coli C41λ(DE3) and expressed in 4 L of LB + ampicillin, and ZnSO4 (50 µM). S. enterica CobB was purified as described (Garrity et al., 2007). Expression and purification of S. enterica PncA nicotinamidase were as described (Garrity et al., 2007).

In vitro protein acetylation assay

Protein acetylation was observed using radiolabeled Ac-CoA as described (Starai & Escalante-Semerena, 2004). Reactions contained HEPES buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0), TCEP (1 mM), KCl (20 mM), [1-14C]Ac-CoA (19 µM), acyl-CoA synthetase (3 µM), and RpPat (0.06 µM). Reactions (25 µl total volume) were incubated for 60 min at 30°C. Samples (5 µl each) were resolved using SDS-PAGE (Laemmli, 1970), and proteins were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining (Sasse, 1991). Gels were dried and exposed overnight to a MultiPurpose Phosphor Screen (Packard). Radioactivity was detected using a Cyclone Storage Phosphor System (Packard) equipped with OptiQuant v 04.00 software (Packard).

In vitro CoA synthetase activity assay

CoA synthetases (3 µM each) were individually incubated with Pat (1 µM) and 50 µM Ac-CoA or CoASH (non-acetylated control) for 2h at 30 °C using the same buffer system described above for 14C acetylation assays. Acetylation reactions were stopped by buffer exchange into HEPES (50 mM, pH 7.5) containing KCl (20 mM). Acyl-CoA synthetase activity was measured using an NADH-consuming assay (Reger et al., 2007). Reactions contained HEPES (50 mM, pH 7.5), TCEP (1 mM), ATP (2.5 mM), CoASH (1 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), phosphoenolpyruvate (3 mM), NADH (0.1 mM), pyruvate kinase (1 U), myokinase (5 U), lactate dehydrogenase (1.5 U), and either benzoate, 4-hydroxybenzoate, cyclohexanecarboxylate, or acetate (0.2 mM). Reactions were started by the addition of acyl-CoA synthetase (30 nM), and the absorbance at 340 nm was monitored for 10 min using a PerkinElmer Lambda 40 UV-visible spectrophotometer. Enzyme activities were calculated as described (Garrity et al., 2007).

Protein deacetylation assays

The R. palustris ldaA+ gene was expressed in strain JE11691, a CobB (sirtuin) deacetylase-deficient strain of E. coli K-12 MG1655. The R. palustris srtN+ strain was expressed similarly, using strain JE11960. Cultures (100 ml each) were grown overnight in LB + ampicillin (100 µg ml−1) + arabinose (1 mM). Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and re-suspended in 1 ml of deacetylase buffer containing HEPES (50 mM, pH 7.5), NaCl (300 mM), dithiothreitol (1 mM), and ZnCl2 (25 µM). Cells were lysed with BugBuster® reagent (Novagen) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was dialyzed for 1 h against deacetylase buffer in a microdialyzer (Pierce). AliA and untagged BadA proteins were acetylated with 20 µM [1-14C]-Ac-CoA or unlabeled Ac-CoA and 0.06 µM RpPat as described above, and the acetylation reaction was stopped by buffer exchange into HEPES (50 mM, pH 7.5), TCEP (1 mM), and KCl (20 mM) using Microcon YM-30 centrifugal filter units. HbaA was acetylated similarly, except that KCl was omitted from the reaction, and 50 µM acetyl-CoA and 0.5 µM Pat were used to achieve greater extents of acetylation. A sample of dialyzed, clarified cell-free extracts containing 80 µg of protein was added to the reaction mixture (50 µl final volume) containing acetylated BadA, and 10-µl samples were removed over time and quenched with SDS-PAGE gel-loading buffer. BadA protein was visualized using SDS-PAGE, and radioactivity was quantified using phosphorimaging as described above. To determine CoA synthetase activity, 100 µl of the acetylation reaction was incubated with cell lysates (250 µg of protein) from strains expressing ldaA or the empty vector. The deacetylation reactions were incubated for 30 min at 30 °C, and the rate of AMP generation was measured using the coupled spectrophotometric assay described above.

We tested whether RpSrtN or SeCobB could deacetylate BadAAc. For this purpose we incubated [14C-Ac]-BadA (6 µM) with RpSrtN or SeCobB (6 µM) and NAD+ (1 mM) in HEPES buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5) containing TCEP (1 mM). Proteins were resolved using SDS-PAGE and radioactivity was quantified by phosphorimaging. Addition of PncA nicotinamidase (~4 µM) to the reaction mixture did not enhance deacetylation.

Purification of BadA from R. palustris

Five hundred-ml cultures of strains JE13049 (CGA009 / pRpBADA4), JE11639 (CGA009 ldaA srtN / pRpBADA4), and JE13050 (CGA009 ldaA srtN pat / pRpBADA4) were grown until they reached stationary phase (four to seven days) anaerobically in the light on PM + benzoate (3 mM). Similarly, an 800-ml culture of strain JE12146 (CGA009 ldaA srtN badF / pRpBADA4) was grown on PM + succinate (10 mM) + benzoate (3 mM) for eight days in the light. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and re-suspended in 10 ml of buffer ABadA plus 1 mg ml−1 of lysozyme. Cells were lysed by sonication and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. H10-BadA protein was purified using a His-Bind Quick 900 cartridge (Novagen) with the same buffer system for BadA as described above. For subsequent deacetylation reactions, purified BadA was dialyzed overnight into HEPES (50 mM, pH 7.5) buffer containing NaCl (150 mM).

The synthetase activity of BadA was then assessed. To do this, BadA (1 µM) purified from strains JE11639, JE13049, and JE13050 (see table 2) was deacetylated with SeCobB (or no deacetylase control to estimate the in vivo activity of BadA) as described in the above section for 2 h at 37 °C. A sample of the deacetylation reaction mixtures was used to assess BadA activity. The concentration of BadA in the synthetase activity assays was 40 nM.

Identification of acetylation sites by mass spectrometry

To determine the site of acetylation, purified BadA protein was incubated with RpPat and 50 µM Ac-CoA as described above, and compared to a non-acetylated control. To determine the identity of the in vivo modification of BadA, H10-BadA purified from R. palustris was resolved by SDS-PAGE and the band corresponding to BadA was excised. In-gel trypsin digestion and mass spectrometric analysis of the peptides was performed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Mass Spectrometry Facility. Tryptic digestion and peptide recovery was performed as outlined on website: http://www.biotech.wisc.edu/ServicesResearch/MassSpec/ingel.htm.

Peptides were analyzed by nanoLC-MS/MS using the Agilent 1100 nanoflow system connected to a hybrid linear ion trap-orbitrap mass spectrometer LTQ-Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source. Capillary HPLC was performed using an in-house fabricated column with integrated electrospray emitter (11) except that 360 µm × 75 µm fused silica tubing was used. The column was packed with 5 µm C18 particles (Column Engineering) to ~12 cm. Sample loading (8 µl) and desalting were achieved using a trapping column (Zorbax 300SB-C18, 5 µM, 5 × 0.3 mm, Agilent) in line with the autosampler. HPLC solvents were as follows: Loading: acetonitrile (1%, v/v), acetic acid (0.1 M); A: acetic acid in water (0.1 M), and B: acetonitrile (95%, v/v), acetic acid in water (0.1 M). Sample loading and desalting were done at 10 µl/min with the loading solvent delivered from an isocratic pump. Gradient elution was performed at 200 nL/min and increasing %B in A of 0 to 40 in 100 min, 40 to 60 in 15 min, and 60 to 100 in 5 min. The LTQ-Orbitrap was set to acquire MS/MS spectra in data-dependent mode as follows: MS survey scans from charge-to-mass ratio (m/z) from 300 to 2000 were collected in profile mode at a resolving power of 100,000. MS/MS spectra were collected on the three most-abundant signals in each survey scan. Dynamic exclusion was employed to increase dynamic range and maximize peptide identifications. This feature excluded precursors up to 0.55 m/z below and 1.05 m/z above previously selected precursors. Precursors remained on the exclusion list for 15 s. Singly charged ions and ions for which the charge state could not be assigned were rejected from consideration for MS/MS. Raw MS/MS data were converted to mgf file format using Trans Proteomic Pipeline (Seattle Proteome Center, Seattle, WA). Resulting mgf files were searched against NCBI non-redundant proteobacteria amino acid sequence database using in-house Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, London, UK) with methionine oxidation and lysine acetylation as variable modifications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by PHS grant R01-GM62203 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (to J.C.E.-S.), and DOE grant DE-FG02-08ER15707 to C.S.H. H.A.C. was supported in part by PHS Biotechnology Training Grant T32 GM08349, and an NSF graduate research fellowship. We are grateful to Grzegorz Sabat at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center for assistance with mass spectrometry, and Ana Misic for help with modeling in Pymol.

Abbreviations

- 4-HBA

4-hydroxybenzoic acid

- CHC

cyclohexanecarboxylate

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- IPTG

isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside

- CoASH

coenzyme A

- Bz,CoA

benzoyl-CoA

- Ac-CoA

acetyl-CoA

- PPi

pyrophosphate

- O-AADPR

O-acetyl-ADP-ribose

- Nm

nicotinamide

REFERENCES

- Bains J, Boulanger MJ. Biochemical and structural characterization of the paralogous benzoate CoA ligases from Burkholderia xenovorans LB400: defining the entry point into the novel benzoate oxidation (box) pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:965–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch WE, Wolfe RS. New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (HS-CoM)-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1976;32:781–791. doi: 10.1128/aem.32.6.781-791.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barragan MJ, Blazquez B, Zamarro MT, Mancheno JM, Garcia JL, Diaz E, Carmona M. BzdR, a repressor that controls the anaerobic catabolism of benzoate in Azoarcus sp. CIB, is the first member of a new subfamily of transcriptional regulators. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:10683–10694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertani G. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1951;62:293–300. doi: 10.1128/jb.62.3.293-300.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertani G. Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:595–600. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.595-600.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blommel PG, Fox BG. A combined approach to improving large-scale production of tobacco etch virus protease. Protein Expr. Purif. 2007;55:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll M, Albracht SS, Fuchs G. Benzoyl-CoA reductase (dearomatizing), a key enzyme of anaerobic aromatic metabolism. A study of adenosinetriphosphatase activity, ATP stoichiometry of the reaction and EPR properties of the enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;244:840–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll M, Fuchs G. Benzoyl-coenzyme A reductase (dearomatizing), a key enzyme of anaerobic aromatic metabolism. ATP dependence of the reaction, purification and some properties of the enzyme from Thauera aromatica strain K172. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;234:921–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.921_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona M, Zamarro MT, Blazquez B, Durante-Rodriguez G, Juarez JF, Valderrama JA, Barragan MJ, Garcia JL, Diaz E. Anaerobic catabolism of aromatic compounds: a genetic and genomic view. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009;73:71–133. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00021-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti E, Stachelhaus T, Marahiel MA, Brick P. Structural basis for the activation of phenylalanine in the non-ribosomal biosynthesis of gramicidin S. Embo J. 1997;16:4174–4183. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagley S. New perspectives in aromatic catabolism. In: Leisinger T, Cook AM, Hutter R, Nuesch J, editors. Microbial degradation of xenobiotics and recalcitrant compounds. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Denu JM. Vitamin B(3) and sirtuin function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:479–483. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz E. Bacterial degradation of aromatic pollutants: a paradigm of metabolic versatility. Int. Microbiol. 2004;7:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dispensa M, Thomas CT, Kim MK, Perrotta JA, Gibson J, Harwood CS. Anaerobic growth of Rhodopseudomonas palustris on 4-hydroxybenzoate is dependent on AadR, a member of the cyclic AMP receptor protein family of transcriptional regulators. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:5803–5813. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5803-5813.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egland PG, Gibson J, Harwood CS. Benzoate-coenzyme A ligase, encoded by badA, is one of 3 ligases able to catalyze benzoyl-coenzyme A formation during anaerobic growth of Rhodopseudomonas palustris on benzoate. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:6545–6551. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6545-6551.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egland PG, Harwood CS. BadR, a new MarR family member, regulates anaerobic benzoate degradation by Rhodopseudomonas palustris in concert with AadR, an Fnr family member. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:2102–2109. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2102-2109.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egland PG, Pelletier DA, Dispensa M, Gibson J, Harwood CS. A cluster of bacterial genes for anaerobic benzene ring biodegradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997;94:6484–6489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs G. Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1125:82–99. doi: 10.1196/annals.1419.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JG, Escalante-Semerena JC. Biochemical and mutational analyses of AcuA, the acetyltransferase enzyme that controls the activity of the acetyl coenzyme a synthetase (AcsA) in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:5132–5136. doi: 10.1128/JB.00340-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JG, Escalante-Semerena JC. In Bacillus subtilis, the sirtuin protein deacetylase encoded by the srtN gene (formerly yhdZ), and functions encoded by the acuABC genes control the activity of acetyl-CoA synthetase. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:1749–1755. doi: 10.1128/JB.01674-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JG, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM, Escalante-Semerena JC. Control of acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase (AcsA) activity by acetylation/deacetylation without NAD(+) involvement in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:5460–5468. doi: 10.1128/JB.00215-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity J, Gardner JG, Hawse W, Wolberger C, Escalante-Semerena JC. N-lysine propionylation controls the activity of propionyl-CoA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30239–30245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler JF, Harwood CS, Gibson J. Purification and properties of benzoate-coenzyme A ligase, a Rhodopseudomonas palustris enzyme Involved in the anaerobic degradation of benzoate. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:1709–1714. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1709-1714.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J, Dispensa M, Fogg GC, Evans DT, Harwood CS. 4-Hydroxybenzoate-coenzymeA ligase from Rhodopseudomonas palustris - Purification, gene sequence, and role in anaerobic degradation. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:634–641. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.634-641.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J, Harwood C. Metabolic diversity in aromatic compound utilization by anaerobic microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2002;56:345–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallows WC, Lee S, Denu JM. Sirtuins deacetylate and activate mammalian acetyl-CoA synthetases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:10230–10235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604392103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison FH, Harwood CS. The pimFABCDE operon from Rhodopseudomonas palustris mediates dicarboxylic acid degradation and participates in anaerobic benzoate degradation. Microbiology. 2005;151:727–736. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood CS, Burchhardt G, Herrmann H, Fuchs G. Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds via the benzoyl-CoA pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1999;22:439–458. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff KG, Avalos JL, Sens K, Wolberger C. Insights into the sirtuin mechanism from ternary complexes containing NAD+ and acetylated peptide. Structure. 2006;14:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M-K, Harwood CS. Regulation of benzoate-CoA ligase in Rhodopseudomonas palustris. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1991;83:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, 2nd, Peterson KM. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer FW, Chain P, Hauser L, Lamerdin J, Malfatti S, Do L, Land ML, Pelletier DA, Beatty JT, Lang AS, Tabita FR, Gibson JL, Hanson TE, Bobst C, Torres JL, Peres C, Harrison FH, Gibson J, Harwood CS. Complete genome sequence of the metabolically versatile photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nbt923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May JJ, Kessler N, Marahiel MA, Stubbs MT. Crystal structure of DhbE, an archetype for aryl acid activating domains of modular nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:12120–121205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182156699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu T, Ichiyama S, Hiratake J, Saldanha A, Kobashi N, Sakata K, Kato H. Structural basis for the spectral difference in luciferase bioluminescence. Nature. 2006;440:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature04542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen TK, Hildmann C, Dickmanns A, Schwienhorst A, Ficner R. Crystal structure of a bacterial class 2 histone deacetylase homologue. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;354:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peres CM, Harwood CS. BadM is a transcriptional repressor and one of three regulators that control benzoyl coenzyme A reductase gene expression in Rhodopseudomonas palustris. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:8662–8665. doi: 10.1128/JB.01312-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt J, Hynes MF. Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1993;127:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger AS, Carney JM, Gulick AM. Biochemical and crystallographic analysis of substrate binding and conformational changes in acetyl-CoA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6536–6546. doi: 10.1021/bi6026506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocco CJ, Dennison KL, Klenchin VA, Rayment I, Escalante-Semerena JC. Construction and use of new cloning vectors for the rapid isolation of recombinant proteins from Escherichia coli. Plasmid. 2008;59:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta SK, Harwood CS. Use of the Rhodopseudomonas palustris genome sequence to identify a single amino acid that contributes to the activity of a coenzyme A ligase with chlorinated substrates. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1151–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse J. Detection of proteins. In: Ausubel FA, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley Interscience; 1991. pp. 10.16.11–10.16.18. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer A, Tauch A, Jager W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Puhler A. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene. 1994;145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Bunkenborg J, Verdin RO, Andersen JS, Verdin E. Reversible lysine acetylation controls the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme acetyl-CoA synthetase 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:10224–10229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603968103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Celic I, Cole RN, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. Sir2-dependent activation of acetyl-CoA synthetase by deacetylation of active lysine. Science. 2002;298:2390–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1077650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Escalante-Semerena JC. Identification of the protein acetyltransferase (Pat) enzyme that acetylates acetyl-CoA synthetase in Salmonella enterica. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Takahashi H, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. Short-chain fatty acid activation by acyl-coenzyme A synthetases requires SIR2 protein function in Salmonella enterica and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2003;163:545–555. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W:improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acid Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang AW, Escalante-Semerena JC. CobB, a new member of the SIR2 family of eucaryotic regulatory proteins, is required to compensate for the lack of nicotinate mononucleotide:5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole phosphoribosyltransferase activity in cobT mutants during cobalamin biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium LT2. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:31788–31794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt FH, Bolin JT, Eltis LD. The ins and outs of ring-cleaving dioxygenases. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;41:241–267. doi: 10.1080/10409230600817422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetting MW, Carvalho LPSd, Yu M, Hegde SS, Magnet S, Roderick SL, Blanchard JS. Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005a;433:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetting MW, de Carvalho LP, Roderick SL, Blanchard JS. A novel dimeric structure of the RimL Nalpha-acetyltransferase from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 2005b;280:22108–22114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502401200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaar A, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Fuchs G. A novel pathway of aerobic benzoate catabolism in the bacteria Azoarcus evansii and Bacillus stearothermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:24997–25004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaar A, Gescher J, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Fuchs G. New enzymes involved in aerobic benzoate metabolism in Azoarcus evansii. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:223–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.