Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia that affects several million people worldwide. The major neuropathological hallmarks of AD are the presence of extracellular amyloid plaques that are composed of Aβ40 and Aβ42 and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), which is composed of hyperphosphorylated protein Tau. While the amyloid plaques and NFT could define the disease progression involving neuronal loss and dysfunction, significant cognitive decline occurs before their appearance. Although significant advances in neuroimaging techniques provide the structure and physiology of brain of AD cases, the biomarker studies based on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma represent the most direct and convenient means to study the disease progression. Biomarkers are useful in detecting the preclinical as well as symptomatic stages of AD. In this paper, we discuss the recent advancements of various biomarkers with particular emphasis on CSF biomarkers for monitoring the early development of AD before significant cognitive dysfunction.

1. Introduction

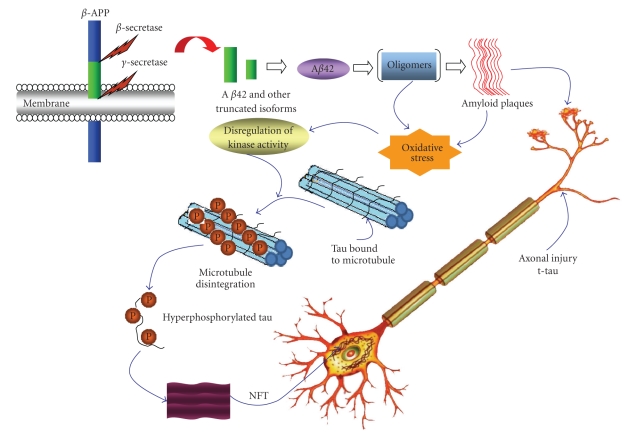

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most widespread neurodegenerative disease globally [1] and is estimated to afflict more than 27 million people worldwide [2]. AD accounts for at least 60% of all dementia diagnosed clinically. The major pathological hallmarks of AD are the loss of neurons, occurrence of extracellular senile plaques as well as intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) [3]. Senile plaques are primarily composed of amyloid β-protein (Aβ), which is produced from the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by sequential proteolytic cleavages made by two proteolytic enzymes, β-secretase (β-site APP-cleaving enzyme; BACE) and γ-secretase (Figure 1) [4]. Amyloid plaque is an aggregate of Aβ containing 40–42/43 residues. NFT is primarily composed of hyperphosphorylated form of Tau protein [5]. Tau is synthesized within the neuron and localized in the axon where it promotes stability and assembly of microtubules [6]. During AD progression, tau is hyperphosphorylated and subsequently dissociated from microtubule and polymerized into paired helical filaments (Figure 1) [5, 6]. Although the clinical symptoms of AD are frequently diagnosed in older age, the degenerative process probably starts many years before the clinical onset of the disease [7, 8]. Currently, the diagnosis and treatment of AD is limited. The presymptomatic detection of AD is crucial, as it would facilitate the development of an efficient and rapid treatment of this destructive disorder early on (for recent review see [9–11]).

Figure 1.

Pathological cascades and potential biomarkers of AD. Proteolytic cleavage of APP first by β-secretase followed by γ-secretase can produce Aβ42 and other shorter Aβ fragments. The subsequent aggregation of Aβ42 results in oligomers and amyloid fibrils. Amyloid fibrils are eventually deposited as senile plaques as shown. The toxicity of oligomers and amyloid fibrils could lead to the cascade of tau-hyperphosphorylation, which is otherwise bound to microtubules, providing microtubule stability. Upon hyperphosphorylation, tau dissociates from microtubules and aggregates into NFT, which could eventually cause increased cytoskeleton flexibility and neuronal death.

The biomarkers are the entities whose concentration, presence, and activity are associated with disease. Biomarkers are essential part of disease treatments as they are essential for diagnosis, monitoring the disease progression, detecting early onset of the disease, monitoring the effect of therapeutic intervention, and also avoiding false diagnosis of the disease [19]. An ideal biomarker (1) should be highly specific, (2) should predict the course of illness accurately, and (3) should reflect the degree of response to treatment. The biomarker research for AD has significantly advanced in recent years (Table 1) [9, 10]. The neuroimaging techniques assess the regional structure and function of the brain, as well as assist identifying the biochemical profile of brain dysfunction. The body fluids such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), plasma, and urine are considered as important sources for the AD biomarker development (Table 1). CSF is considered a better source for biomarker development as it is in direct contact with the extracellular space of the brain and can reflect biochemical changes that occur inside the brain. Thus far, three CSF biomarkers, Aβ42, total-tau (t-tau), and phosphorylated-tau (p-tau), have been found to have the highest diagnostic potential. Biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress and urine-based biomarkers are among the other sources that provide vital information on development and progression of AD. Unfortunately, none of the biomarkers presently available are able to accomplish the disease diagnosis single-handedly. Monitoring more than one biomarker at the same time is suggested to be suitable for detecting the disease progression. The main focus of this paper is to provide insights on the various potential biomarkers with particular emphasis on CSF biomarkers for AD diagnosis. These biomarkers are very promising for early diagnosis of AD.

Table 1.

Some promising biomarkers in diagnosis of AD.

| Category | Markers | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging | (1) Noninvasive | (1) Expensive | [12–14] | |

| CT, PET, PIB-PET, | (2) Provides structural and functional | (2) Requires experienced personnel | ||

| MRI | details of brain immediately | (3) The sensitivity and specificity to | ||

| (3) Can reveal disease progression | AD is not satisfactory | |||

|

| ||||

| Plasma | α 2-Macroglobulin, | (1) Noninvasive | (1) Less correlation to AD | [15–17] |

| Complement | (2) Samples are easily accessible | (2) Less sensitive and specific for AD | ||

| factor H, Aβ42 | diagnosis (due to epitope masking) | |||

|

| ||||

| CSF | Aβ42, t-tau, | (1) Can correlate AD directly | (1) Invasive, sample has to be collected | [10, 18] |

| p-tau p-tau/Aβ42, | (2) Highly sensitive and specific | by lumbar puncture | ||

| t-tau/Aβ42 | (3) Can detect AD progression | (2) Irreproducible diagnosis due to | ||

| sample storage and transportation | ||||

2. Imaging Biomarkers

Neuroimaging techniques provide structural and functional details of the brain immediately [20, 21]. The imaging techniques are also helpful to predict and monitor the disease progression. Recent progress of functional and molecular neuroimaging [22] could provide insights into brain structure and physiology and also could detect the specific proteins and protein aggregates due to AD in the brain [20].

The loss of brain volume is one of the consequences of AD neurodegeneration [11, 21], and it could be differentiated from normal brain by using computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques [23]. These techniques are able to show neuronal loss, atrophy of medial temporal regions, as well as neurofibrillary tangles in the brain of AD patients. Using MRI technique, it is now possible to distinguish atrophy during early stage of AD from the atrophy of normal aging [24]. MRI has also the ability to distinguish AD subjects from normal controls, with a very high sensitivity and specificity [24]. MRI can reveal disease progression from cognitive normalcy to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and to AD [12]. Discrimination of AD from other forms of dementia, namely, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and DLB (dementia with Lewy bodies) is also possible based on different atrophy patterns that MRI reveals [25–27]. AD is also associated with metabolic impairment with typical regional pattern in the brain and could be detected by positron emission tomography (PET). If 18F-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) is chosen for PET, the concentrations of tracer imaged then gives tissue metabolic activity, in terms of regional glucose uptake. PET-FDG has been employed to examine regional cerebral metabolism, which is helpful in distinguishing AD from normal patients [13, 28–30]. Recently, several other radiologically contrast compounds have been developed for PET imaging, which could bind the pathological structures such as amyloid plaques, NFT, activated microglia, and reactive astrocytes, enabling the examination of antemortem pathological changes due to AD. The compounds that have been reported as probes for amyloid plaques in PET imaging include, [18F] FDDNP (2-(1-{6-[(2-[F-18] fluoroethyl) (methyl) amino]-2-naphthyl} ethylidene) malononitrile), 18F-BAY94-9172, 11C-SB-13, 11C-BF-227, and 11C-PIB. The only compound developed that can bind NFT in vivo is [18F] FDDNP. The 11C-PIB (PIB, Pittsburgh compound B) has been the most extensively studied and applied in AD research [14, 31]. In individuals with AD, increased retention of PIB shows a very specific pattern that is restricted to brain regions (frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital cortices, and striatum), typically associated with amyloid deposition [32]. A significant number of cognitively normal individuals over the age of 60 show a PIB signal pattern indistinguishable from that of individuals with AD, suggesting that measurement of PIB using PET can detect a preclinical stage of the disease. When PIB-PET was performed along with the Aβ42 concentrations in CSF of AD patients, the PIB-positive group showed low Aβ42 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid [33–35]. This finding is consistent with the “amyloid sink” hypothesis [36, 37], according to which the soluble Aβ42 is retained in the brain once plaques are formed. Besides the radiological studies of amyloid plaques and NFT, the PET imaging agent which images the inflammation due to activated microglia and reactive astrocytes has been developed. For example, increased expression of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) has been target for the compound [11C] (R)-PK11195. The study using this compound in conjunction with PIB has suggested that microgliosis occurs concomitantly with amyloid deposition and may have direct role in cognitive dysfunction [38]. Like microglia, the changes in astrocytes on association with plaques could be used as biomarkers. For example, using inhibitors of monoamine oxidase B as radiotracers in AD has targeted the elevation of monoamine oxidase B activity [39, 40]. Although all of these imaging techniques are helpful for diagnosis of AD, the approach faced overlapping symptoms due to other pathological processes and normal aging. The approach also needs expensive instruments and experienced personnel for its application in routine diagnosis of AD.

Fluid Biomarkers —

The sampling of CSF and plasma represents the most direct and convenient means to study the biochemical changes occurring in the central nervous system [10, 19, 41]. These fluids are the most attractive resources for ongoing research for discovering AD biomarkers. Most of the research has been performed either with the plasma or CSF, yet CSF represents more suitable source for biomarker discovery.

3. Plasma Biomarkers

Plasma is the liquid portion of blood where red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets are suspended. Plasma could be easily isolated from whole blood by low speed centrifugation in the presence of an anticoagulant. The easier sampling of blood plasma makes this fluid ideal for biomarker investigation. However, plasma biomarkers as reliable markers for AD have met little success (Table 1). Various blood biomarkers have been proposed, yet changes in the levels of these molecules have proved difficult to verify in independent studies. Multiple studies have identified plasma proteins whose expression levels in AD patients differ from controls. For example, α 2-Macroglobulin (α2M) and complement factor H (CFH) showed an increased expression in AD subjects than in control [15]. Both of these proteins are shown to be present in senile plaques [42, 43]. Similarly, the increased levels of α 1-antitrypsin [44], α1-antichymotrypsin [45, 46], and decreased levels of Apolipoprotein A1 [47] in blood plasma/serum were observed in AD patients compared to healthy controls. Although these proteins may reflect pathological processes observed in AD and could differentiate diseased plasma compared to controls, these differences have yet to achieve sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. Irreproducibility might occur due to different analytical methodologies utilized in various laboratories, different choice of anticoagulant and depletion strategy, and storage related problems. The most popular plasma peptide utilized for biomarker research is Aβ, which is the fundamental element of senile plaques in brain of AD patients [3]. Using ELISA, Aβ can be detected in plasma. The findings from different studies have shown variable results. Some studies have suggested slightly higher Aβ42 or Aβ40 plasma levels in patients with AD than in controls [48]. However, most of the studies have found no change in plasma Aβ concentration between AD and healthy control [48]. It is also suggested that large Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio could indicate the risk factors for AD [49]. These ambiguous results are probably explained by the fact that plasma Aβ is derived from peripheral tissues and does not reflect brain Aβ production. Furthermore, the hydrophobic nature of Aβ makes the peptide bind to plasma proteins, which could result in “epitope masking” [16] and other analytical interferences. Recently, analysis of 18 plasma signaling and inflammatory proteins has accurately identified patients with AD and predicted the onset of AD in individuals with MCI [50]. However, further studies are required to analyze if this set of proteins is the best possible recipe of plasma biomarkers for preclinical AD diagnosis.

4. Urine-Based Biomarkers

Neural thread protein (NTP) levels have been consistently identified as an AD biomarker in urine [51, 52]. With disease severity, the urinary concentration of this protein increases. AD associated NTP (AD7c-NTP) in CSF also showed consistent results [51, 53]. More research needs to be done to study the effects of AD7c-NTP levels upon therapeutic intervention [54–56]. Urinary F2-isoprostanes have been reported to be increased [54–56] or unchanged [57, 58], making them less reliable biomarkers. The utility of urine sample for AD diagnosis has advantage that sample collection is relatively easier and noninvasive compared to CSF and plasma. However, very low protein concentrations and high salt levels make it difficult to use urine sample as a source of biomarker [59].

5. CSF Biomarkers

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a translucent bodily fluid that occupies the subarachnoid space and the ventricular system around the brain. CSF acts as a “liquid cushion” providing a basic mechanical and immunological protection to the brain inside the skull and it can be obtained via lumbar puncture. Although lumbar puncture is invasive and potentially painful for the patient, CSF is probably the most informative fluid in biomarkers discovery for neurodegenerative disease prognosis [10]. CSF has more physical contact with brain than any other fluids, as it is not separated from the brain by tightly regulated blood brain barrier (BBB). As a result, proteins or peptides that may be directly reflective of brain specific activities as well as disease pathology would most likely diffuse into CSF than into any other bodily fluid. These proteins and metabolites can serve as excellent biomarkers of AD as well as other neurodegenerative diseases. In early course of AD, for an example of MCI, when the correct diagnosis is most difficult, CSF biomarkers would be valuable in particular [10]. Tau and Aβ in CSF represents the earliest and most intensively studied biomarkers [9, 10, 41, 60, 61]. Both proteins are linked to hallmark lesions of AD, amyloid plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles. In the next section, we will discuss the clinical significance of Aβ and tau biomarkers in detail.

5.1. APP, Aβ40/42, and Truncated Aβ in CSF as Biomarkers

One of the major pathological features of AD is the presence of senile plaques primarily composed of Aβ, a proteolytic fragment of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) (Figure 1) [62]. The expression level of APP could serve as diagnostic markers in AD [61]. However, the experimental studies of APP expression level in CSF of AD patients are inconsistent [61]. The inconsistencies between studies ruled out the possibility of CSF-APP being a useful biomarker for AD. APP is expressed in all tissues and could undergo cleavage by either α-secretase or β-secretase to release sAPP-α or sAPP-β, respectively. The processing of APP by α-secretase occurs via nonamyloidogenic pathway, and a reduced CSF level of sAPPα in AD patients has been reported [63]. In contrast, APP processing first by β-secretase and subsequent digestion by γ-secretase leads to formation of Aβ (38–43 residues) peptides. The 42-residue-long Aβ isoform (Aβ42) is highly hydrophobic and forms oligomers and fibrils that accumulate as extracellular plaques (Figure 1) [4]. Because Aβ42 is the dominant component of the plaques seen in AD [64], many groups have investigated the use of Aβ42, as well as the other Aβ species as a diagnostic tool. The amount of total Aβ in CSF is not well correlated with the diagnosis of AD [65]. The majority of studies have demonstrated a decrease of CSF Aβ42 in AD patients [34, 66–70]. However, few reports suggest the increased [71] or unchanged [72] CSF Aβ42 in AD. These differences in observations might be due to the variations in sample assaying protocols and selection of patient groups. Deposition of the peptide in plaques (“amyloid sinks”) is considered the underlying basis for the decrease of CSF-Aβ42 levels seen in AD [36, 37]. Although it is not clearly proved, the observation is supported by the strong correlation between low CSF-Aβ42 levels and high plaque burden when measured by PIB imaging [33]. This observation was further supported by the fact that AD mouse model showed low CSF Aβ level with high amount of plaque in the brain [73]. Although it has been shown that CSF Aβ42 levels can identify PIB-positive individuals with highest possible sensitivity and specificity, the decreased CSF levels of Aβ42 have also been reported in other dementia such as FTD [74–76]. Low concentrations of CSF Aβ42 was also found with individuals without PIB-positive plaque [77]. This finding might be explained by the fact that PIB binds fibrillar Aβ not the Aβ oligomers or diffuse plaques [77] that are found in earlier stages of AD process. It is however that CSF Aβ42 has high potential as a biomarker for diagnosis, plaque burden, prognosis and may provide clue of preclinical AD. Aβ40 is unchanged in the CSF of AD patients [21]. However, the decreased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio is much more pronounced in AD diagnosis than the reduction of Aβ42 alone. Therefore, Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio might be more useful in AD diagnosis in the early as well as the clinical phases of the disease [78]. Moreover, the presence of several shorter Aβ isoforms in CSF has suggested that Aβ constitutes a large family of peptides with considerable length variations. The carboxy-terminal truncated Aβ peptides for example, Aβ37, Aβ38, and Aβ39 have been found in CSF of AD subjects. In AD patients, an increase in Aβ38 levels, accompanied with a decrease in Aβ42 levels were also observed [79, 80]. Thus, the Aβ42/Aβ38 ratio might prove useful for more precise diagnosis of AD [79, 80]. Immunoprecipitation techniques and mass spectrometry have identified a number of short truncated Aβ isoforms, such as Aβ14, Aβ15, and Aβ16 in the CSF of AD patients. These forms have been reported to be produced through a novel pathway of APP processing involving the β and α secretase actions [81]. In the AD subjects, elevated Aβ16 levels, accompanied with a decrease in Aβ42 levels were reported in CSF [82].

5.2. CSF-Tau as a Biomarker

The protein tau is an intracellular protein, which maintains the stability of microtubules in neurons. In normal individual, only low concentration of tau is present in CSF. The function of tau is tightly regulated by a number of post-translational modifications including phosphorylation at serine and threonine residues. The precise form of tau in CSF and the mechanism for leakage of intracellular tau into CSF is not clearly understood. Despite intense research, the amyloid and tau pathologies remain unclear. Several experimental studies have suggested that hyperphosphorylation and NFT formation is the downstream phenomenon of AD pathologies [83]. However, it is also noteworthy that loss of function of tau due to hyperphosphorylation and subsequent detachment of tau from microtubule could lead to the increased cytoskeleton flexibility and loss of axonal integrity in the brain (Figure 1) [84]. In AD, tau becomes hyperphosphorylated and gets dissociated from microtubule and subsequently polymerized into insoluble paired helical filaments (PHF) [84]. PHF eventually contributes to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles [85, 86]. NFT formation and neuronal degradation is an essential part of AD pathology (Figure 1). Upon significant disruption of neuronal architecture, tau protein could be released into CSF [60]. Therefore, increased levels of tau and hyperphosphorylated tau in CSF can correlate with the onset of neurodegeneration in AD. The total tau (t-tau) concentration in CSF has been investigated by ELISA analysis using monoclonal antibodies against all tau isoforms. Several studies have suggested that t-tau concentration in CSF of AD patients is higher than control [60, 87]. Although the CSF t-tau is very sensitive biomarker for detecting AD, it has limited ability to discriminate AD from other major forms of dementia as t-tau also increased in CSF of others form of dementia including vascular dementia (VAD) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [60]. Several studies also used the p-tau in CSF as potential biomarkers since it is the major component of NFT. CSF concentrations of p-tau in AD have been examined using ELISAs based on monoclonal antibodies that can detect its various epitopes of p-tau, namely, (Thr181 + Thr231), (Thr231 + Ser235), Ser199, Thr231, (Ser396 + Ser404), and Thr181 [41, 88, 89]. ELISA study using all antibodies has showed increased CSF concentration of p-tau in AD patients. Moreover, the ability of increased p-tau assays to discriminate AD from normal aging and other dementia is more sensitive and specific than that of CSF concentrations of t-tau and Aβ42 [60, 90, 91]. The experimental evidences of high CSF concentrations of p-tau in only AD patients have suggested that p-tau is not a simple marker of axonal damage and neuronal degeneration, as t-tau, but it is more closely related to AD pathology and the formation of NFT.

5.3. Combined Aβ and Tau in CSF as Biomarkers

It has been suggested that combinations of CSF markers could more successfully discriminate AD from control or other forms of dementia than an individual marker. There are several studies where the diagnostic performance of the combination of CSF t-tau and Aβ42 is analyzed. The evidences have suggested that high CSF concentration of t-tau and low concentrations of Aβ42 could detect AD with high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity [61]. The other combinations of CSF biomarkers have also been evaluated, which suggested that the high CSF p-tau/Aβ42 ratio possesses higher sensitivity and specificity [18] for differentiating AD from normal controls and from subjects with other non-AD dementia than that of the CSF t-tau, p-tau, Aβ42, and ratio of t-tau/Aβ42. It is also suggested that the combination of tau and Aβ42 has more diagnostic potential in terms of sensitivity and specificity in MCI patients to develop future AD [92].

5.4. Oligomers of Aβ in CSF: Promising Biomarkers for Early Diagnosis in AD

Recent studies have suggested that oligomeric Aβs are the most neurotoxic species in AD. Substantial in vivo and in vitro evidence supports this hypothesis [93–97]. Several in vitro neurotoxicity studies have shown that Aβ oligomers are potent neurotoxins [98–104], and the toxicity of some oligomers is higher than that of the corresponding amyloid fibrils [105]. The evidences, which support the fact that Aβ oligomers could be targeted for drug and biomarker discovery include (1) soluble oligomers could inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) [95, 98, 100, 103, 104, 106, 107] and disrupt cognitive function [108] in vivo; (2) compounds that bind and disrupt the formation of oligomers have been shown to block the neurotoxicity of Aβ [108, 109]; (3) drugs that reduce the amyloid plaque burden without disruption of oligomers have little effect on recovery of neurological function [110]. Many oligomers such as Aβ-derived diffusible ligand (ADDL)-like Aβ42 oligomers [111], 90 kDa Aβ42 oligomer [112, 113], 56 kDa oligomer of “Aβ*56 [114], and Aβ trimers [115] have shown high in vivo toxicity, providing a compelling reason for Aβ oligomers to be used as potential AD biomarkers especially for early diagnosis in AD. In addition, elevated levels of Aβ oligomers were detected in AD patients and transgenic mice compared to control [116–118]. The elevated level of oligomers could also appear in CSF but with lower concentration. Therefore, highly sensitive techniques are required for oligomer detection in CSF. The study using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy suggested the presence of Aβ oligomers in CSF of AD patients, compared to healthy control [119]. Recently, ultrasensitive, nanoparticle-based, protein detection assay (bio-barcode) showed that the ADDLs concentrations in CSF of AD patients were consistently higher than the nondemented age-matched control [120]. In this study, ADDLs specific antibodies coupled to DNA-tagged nanoparticles were used to capture the oligomers from the CSF of patients with AD. Although the number of AD patients and controls studied was low, the findings were very promising. Although Aβ oligomers are attractive biomarker candidates, several limitations exist to use these species. The concentration of these Aβ oligomers in CSF is very low in comparison with Aβ monomers. Again, the detection of individual Aβ oligomers is difficult since oligomers are metastable and therefore one form of oligomers could transform to another form immediately. Assay sensitivity must reach very high level if one can detect total heterogeneous population of Aβ oligomers in CSF. The monoclonal antibodies specific for only Aβ oligomers could be difficult to develop. Recently, an antibody against Aβ oligomers was developed, which can detect all Aβ oligomers, including oligomers from other amyloidogenic protein [117]. However, using these oligomers specific antibody to diagnose of AD is difficult since it cannot differentiate AD from other neurodegenerative diseases. New analytical methods and novel oligomers-specific antibody must be developed to detect oligomers in CSF of AD patients, which would have ultimate ability to detect early onset of AD.

5.5. Neuronal Biomarkers in CSF

Besides tau and Aβ, neuronal and synaptic proteins could also be used as CSF biomarkers in AD. For example, Visinin-like protein 1 (VLP-1), a calcium sensor protein was shown to be significantly increased in the CSF of AD subjects compared to controls. It is believed to seep out from dented neurons [121]. The sensitivity and specificity of CSF VLP-1 is comparable to CSF t-tau, p-tau, and Aβ42. Combined analysis of Aβ42, p-tau, and VLP-1 has been reported to raise the diagnostic precision of AD. VLP-1 biomarker might also prove useful in indicating the degree of dementia [121]. The neurofilaments, which are structural component of axons, could also be used as biomarkers for discriminating AD patients from other forms of dementia, as their expression levels are high in VAD and FTD [122], while normal levels are found in most AD patients. Another synaptic protein called growth-associated protein (GAP-43) is found in higher levels in CSF of AD than that of controls, and FTD [123]. Furthermore, it has been shown that CSF GAP-43 and t-tau were increased in AD and correlated positively [123], suggesting both biomarkers are reflecting axonal and synaptic degeneration.

5.6. Oxidative Stress Marker in CSF

Besides the formation of amyloid plaque and NFT, AD is also frequently characterized by reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated neuronal damage. The oxidative damage in the brain mainly involves lipid peroxidation [124]. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are susceptible to oxidation by reactive oxygen species. Isoprostanes are lipid oxidation products generated due to the reaction between fatty acids and ROS. Therefore, isoprostanes could be used as valuable AD biomarkers. Several studies have suggested that F2-isoprostanes, a group of isoprostanes, are increased in CSF of AD patients compared to healthy control or patients with other dementia [125, 126]. CSF-F2-isoprostanes have also been shown to be increased in patients with MCI and asymptomatic carriers of familial AD mutations. A combined analysis of CSF-Aβ42, tau, and F2-isoprostanes, was able to diagnose AD with a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 89% [127].

5.7. Inflammatory Biomarkers in CSF

AD pathology involves release of inflammatory mediators. The differential occurrence of several proteins due to inflammatory process in AD might be used as biomarker. These proteins can be detected using ELISA, as well as proteomics approaches. One of the most studied inflammatory biomarkers is α1-antichymotrypsin (A1ACT), which is observed either increased [45, 128] or unchanged [129] in CSF samples of AD patients. However, the contradictory results suggest that more studies must be conducted to raise the possibility of A1ACT to be regarded as an effective biomarker. The study of cytokines, which are produced during inflammation processes in AD, also gave inconsistent results. For example, CSF interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels have been reported to be increased [130–132], decreased [133], or unchanged [134–136] in AD. Studies of IL-6 receptor, Gp130, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) also produced conflicting results [137]. The genetic background, environmental factors, and usage of anti-inflammatory drugs might produce substantial variation in cytokine levels in an individual [138]. This could be the reason for such uncertain results.

6. CSF Biomarkers: A Potential Hope for AD Diagnosis

As discussed in the preceding sections, most biomarker research in AD is based on either brain imaging or is fluid-based. Although imaging techniques are definitive tests for detecting amyloid plaques and atrophy using molecular probe, still antemortem diagnosis of AD and MCI are less successful. More sensitive chemical probes are required to be developed, which would bind oligomers or diffuse plaque. However, imaging techniques being very expensive and requiring more experience for handling the instruments precludes their day-to-day use for AD diagnosis. In fluid biomarker research, CSF has been proved to be a supreme source for biomarkers for several reasons. CSF is in close proximity to the brain, and therefore biochemical changes in the brain affect the composition of biomarkers in CSF. Since AD pathology is restricted to the brain, CSF is an obvious source of biomarkers for AD. CSF is also a rich source of brain-specific proteins, and changes in these protein levels are observed in CSF with disease progression. CSF biomarkers are also very sensitive to the fine changes in brain that occur in the preclinical stages of the AD. Therefore, CSF is probably the most informative fluid sample available for preclinical as well as symptomatic AD diagnosis. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of CSF biomarkers in differentiating AD from healthy controls, and from other forms of dementia is already achieved with satisfactory levels. Moreover, a combination of more than one biomarker in CSF, such as CSF p-tau, t-tau, and Aβ42 is considered to give higher diagnostic accuracy of AD. It can identify AD, prodromal AD, and also can differentiate AD from other dementia with high sensitivity and specificity that is otherwise impossible to achieve.

Although CSF biomarkers have proved to be highly informative, sensitive, and specific for detection of clinical AD and early stage of AD, their regular use in clinic is still limited. One of the major reasons against the vast applicability of CSF in AD diagnosis is lumbar puncture, an invasive method to collect the CSF sample. Other issues including inconsistency of data analysis of CSF sample due to sample collection, transportation, storage, and high expense of the test might limit the use of CSF for routine diagnosis. However, various strategies are available to resolve these issues. For example, the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory in Gothenburg, Sweden and Alzheimer's Association, have together started a quality control program, the objective of which is to standardize CSF biomarker measurements between both research and clinical laboratories [10]. This program would obviously enhance the diagnostic precision of CSF markers, thus enabling them to support a routine analysis for diagnosis of AD.

7. Future Direction

According to the current clinical diagnostic criteria, AD diagnosis cannot be made until the patient has dementia, which is defined as cognitive symptoms severe enough to interfere with social or occupational activities [139]. This might hinder the preclinical diagnosis of AD. The disease modifying drugs will be most effective and will have most therapeutic value if these are administered in the earliest stage of AD, before amyloid plaques and NFT become prevalent. Since AD is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder both at clinical and neuropathological level, development of biomarkers with 100% efficiency in terms of sensitivity and specificity is difficult to achieve. Also, the effectiveness of the disease modifying drugs could vary from one subgroup to another subgroups, making the utility of biomarkers in clinical trial and drug discovery difficult. Combined analysis of CSF biomarkers represents more suitable diagnostic tool to detect AD patients or detect individuals with MCI. Moreover, sensitive assays should be developed to detect amyloid oligomers in CSF and in the brain. This would raise the possibility for the diagnosis of early onset of AD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Soumen Maji for the cartoon drawing in Figure 1, Ashwani Kumar, and Dr. Sreenivas Chavali for their valuable suggestions during manuscript preparation. We would also like to thank CSIR, India (Grant no. 10CSIR001) for financial support.

Abbreviations

- Aβ:

Amyloid β protein

- AD:

Alzheimer's disease

- ADDL:

Aβ-Derived diffusible ligand

- APP:

Amyloid precursor protein

- BACE:

β-site APP-cleaving enzyme

- BBB:

Blood brain barrier

- CT:

Computerized tomography

- DLB:

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- FTD:

Frontotemporal dementia

- MCI:

Mild cognitive impairment

- MRI:

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NFT:

Neurofibrillary tangles

- PET:

Positron emission tomography

- PIB:

Pittsburgh compound B

- p-tau:

Phosphorylated-tau

- VAD:

Vascular dementia.

References

- 1.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60(8):1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2007;3(3):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selkoe DJ. Cell biology of protein misfolding: the examples of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Nature Cell Biology. 2004;6(11):1054–1061. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazo ND, Maji SK, Fradinger EA, et al. The amyloid beta protein. In: Sipe JD, editor. Amyloid Protein-The Beta Sheet Conformation and Disease. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Publishers; 2005. pp. 385–491. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung Y-C. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein τ (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83(13):44913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Quinlan M. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261(13):6084–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JC. The challenge of characterizing normal brain aging in relation to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 1997;18(4):388–389. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JC, Price JL. Pathologic correlates of nondemented aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2001;17(2):101–118. doi: 10.1385/jmn:17:2:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrin RJ, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM. Multimodal techniques for diagnosis and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2009;461(7266):916–922. doi: 10.1038/nature08538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blennow K, Hampel H, Weiner M, Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2010;6(3):131–144. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark CM, Davatzikos C, Borthakur A, et al. Biomarkers for early detection of Alzheimer pathology. NeuroSignals. 2007;16(1):11–18. doi: 10.1159/000109754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Killiany RJ, Gomez-Isla T, Moss M, et al. Use of structural magnetic resonance imaging to predict who will get Alzheimers disease. Annals of Neurology. 2000;47(4):430–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moulin CJA, Laine M, Rinne JO, et al. Brain function during multi-trial learning in mild cognitive impairment: a PET activation study. Brain Research. 2007;1136(1):132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathis CA, Wang Y, Holt DP, Huang G-F, Debnath ML, Klunk WE. Synthesis and evaluation of 11C-labeled 6-substituted 2-arylbenzothiazoles as amyloid imaging agents. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2003;46(13):2740–2754. doi: 10.1021/jm030026b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hye A, Lynham S, Thambisetty M, et al. Proteome-based plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2006;129(11):3042–3050. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo Y-M, Kokjohn TA, Kalback W, et al. Amyloid-β peptides interact with plasma proteins and erythrocytes: implications for their quantitation in plasma. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;268(3):750–756. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukumoto H, Tennis M, Locascio JJ, Hyman BT, Growdon JH, Irizarry MC. Age but not diagnosis is the main predictor of plasma amyloid β-protein levels. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60(7):958–964. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.7.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maddalena A, Papassotiropoulos A, Müller-Tillmanns B, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease by measuring the cerebrospinal fluid ratio of phosphorylated tau protein to β-amyloid peptide42. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60(9):1202–1206. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.9.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aluise CD, Sowell RA, Butterfield DA. Peptides and proteins in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers for the prediction, diagnosis, and monitoring of therapeutic efficacy of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1782(10):549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kantarci K, Jack CR., Jr. Neuroimaging in Alzheimer disease: an evidence-based review. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 2003;13(2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/s1052-5149(03)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thal LJ, Kantarci K, Reiman EM, et al. The role of biomarkers in clinical trials for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2006;20(1):6–15. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000191420.61260.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raichle ME, Mintun MA. Brain work and brain imaging. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2006;29:449–476. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frisoni GB. Structural imaging in the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: problems and tools. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2001;70(6):711–718. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheltens P, Fox N, Barkhof F, De Carli C. Structural magnetic resonance imaging in the practical assessment of dementia: beyond exclusion. Lancet Neurology. 2002;1(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes J, Whitwell JL, Frost C, Josephs KA, Rossor M, Fox NC. Measurements of the amygdala and hippocampus in pathologically confirmed Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Archives of Neurology. 2006;63(10):1434–1439. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes J, Godbolt AK, Frost C, et al. Atrophy rates of the cingulate gyrus and hippocampus in AD and FTLD. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28(1):20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitwell JL, Jack CR., Jr. Comparisons between Alzheimer disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and normal aging with brain mapping. Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2005;16(6):409–425. doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000245457.98029.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker JT, Mintun MA, Aleva K, Wiseman MB, Nichols T, DeKosky ST. Compensatory reallocation of brain resources supporting verbal episodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46(3):692–700. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grady CL, Furey ML, Pietrini P, Horwitz B, Rapoport SI. Altered brain functional connectivity and impaired short-term memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2001;124(4):739–756. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.4.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodard JL, Grafton ST, Votaw JR, Green RC, Dobraski ME, Hoffman JM. Compensatory recruitment of neural resources during overt rehearsal of word lists in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 1998;12(4):491–504. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(3):446–452. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in alzheimer’s disease with pittsburgh compound-B. Annals of Neurology. 2004;55(3):306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Annals of Neurology. 2006;59(3):512–519. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid tau/β-amyloid 42 ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64(3):343–349. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.noc60123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forsberg A, Engler H, Almkvist O, et al. PET imaging of amyloid deposition in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiology of Aging. 2008;29(10):1456–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motter R, Vigopelfrey C, Kholodenko D, et al. Reduction of beta-amyloid peptide(42), in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimers disease. Annals of Neurology. 1995;38(4):643–648. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samuels SC, Silverman JM, Marin DB, et al. CSF beta-amyloid, cognition, and APOE genotype in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1999;52(3):547–551. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edison P, Archer HA, Gerhard A, et al. Microglia, amyloid, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease: an [11C](R)PK11195-PET and [11C]PIB-PET study. Neurobiology of Disease. 2008;32(3):412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura S, Kawamata T, Akiguchi I, Kameyama M, Nakamura N, Kimura H. Expression of monoamine oxidase B activity in astrocytes of senile plaques. Acta Neuropathologica. 1990;80(4):419–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00307697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirvonen J, Kailajärvi M, Haltia T, et al. Assessment of MAO-B occupancy in the brain with PET and 11 C-L-deprenyl-D 2: a dose-finding study with a novel MAO-B inhibitor, EVT 301. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2009;85(5):506–512. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blennow K, Hampel H. CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurology. 2003;2(10):605–613. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauer J, Strauss S, Schreiter-Gasser U, et al. Interleukin-6 and α-2-macroglobulin indicate an acute-phase state in Alzheimer’s disease cortices. FEBS Letters. 1991;285(1):111–114. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80737-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strohmeyer R, Ramirez M, Cole GJ, Mueller K, Rogers J. Association of factor H of the alternative pathway of complement with agrin and complement receptor 3 in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2002;131(1-2):135–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maes OC, Kravitz S, Mawal Y, et al. Characterization of α1-antitrypsin as a heme oxygenase-1 suppressor in Alzheimer plasma. Neurobiology of Disease. 2006;24(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsubara E, Hirai S, Amari M, et al. α1-antichymotrypsin as a possible biochemical marker for Alzheimer-type dementia. Annals of Neurology. 1990;28(4):561–567. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liebermann J, Schleissner L, Tachiki KH, Kling AS. Serum α1-antichymotrypsin level as a marker for Alzheimer-type dementia. Neurobiology of Aging. 1995;16(5):747–753. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00056-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merched A, Xia Y, Visvikis S, Serot JM, Siest G. Decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and serum apolipoprotein AI concentrations are highly correlated with the severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2000;21(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Irizarry MC. Biomarkers of Alzheimer Disease in Plasma. NeuroRx. 2004;1(2):226–234. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graff-Radford NR, Crook JE, Lucas J, et al. Association of low plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios with increased imminent risk for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64(3):354–362. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray S, Britschgi M, Herbert C, et al. Classification and prediction of clinical Alzheimer’s diagnosis based on plasma signaling proteins. Nature Medicine. 2007;13(11):1359–1362. doi: 10.1038/nm1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghanbari H, Ghanbari K, Beheshti I, Munzar M, Vasauskas A, Averback P. Biochemical assay for AD7C-NTP in urine as an Alzheimer’s disease marker. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 1998;12(5):285–288. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1998)12:5<285::AID-JCLA6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levy S, McConville M, Lazaro GA, Averback P. Competitive ELISA studies of neural thread protein in urine in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 2007;21(1):24–33. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. The AD7c-ntp neuronal thread protein biomarker for detecting Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2002;7:d989–996. doi: 10.2741/monte. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Praticò D, Clark CM, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ, Rokach J, Fitzgerald GA. Increased 8,12-iso-iPF(2α)-VI in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation of a noninvasive index of lipid peroxidation with disease severity. Annals of Neurology. 2000;48(5):809–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Praticò D, Clark CM, Liun F, Lee VY-M, Trojanowski JQ. Increase of brain oxidative stress in mild cognitive impairment: a possible predictor of Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology. 2002;59(6):972–976. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.6.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tuppo EE, Forman LJ, Spur BW, Chan-Ting RE, Chopra A, Cavalieri TA. Sign of lipid peroxidation as measured in the urine of patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Research Bulletin. 2001;54(5):565–568. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bohnstedt KC, Karlberg B, Wahlund L-O, Jönhagen ME, Basun H, Schmidt S. Determination of isoprostanes in urine samples from Alzheimer patients using porous graphitic carbon liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B. 2003;796(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(03)00600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Montine TJ, Shinobu L, Montine KS, et al. No difference in plasma or urinary F2-isoprostanes among patients with Huntington’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease and controls. Annals of Neurology. 2000;48(6):p. 950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thongboonkerd V. Practical points in urinary proteomics. Journal of Proteome Research. 2007;6(10):3881–3890. doi: 10.1021/pr070328s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Formichi P, Battisti C, Radi E, Federico A. Cerebrospinal fluid tau, Aβ, and phosphorylated tau protein for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2006;208(1):39–46. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Craig-Schapiro R, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM. Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2009;35(2):128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Citron M, Diehl TS, Gordon G, Biere AL, Seubert P, Selkoe DJ. Evidence that the 42- and 40-amino acid forms of amyloid β protein are generated from the β-amyloid precursor protein by different protease activities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(23):13170–13175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Nostrand WE, Wagner SL, Shankle WR, et al. Decreased levels of soluble amyloid β-protein precursor in cerebrospinal fluid of live Alzheimer disease patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(7):2551–2555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roher AE, Lowenson JD, Clarke S, et al. β-Amyloid-(1-42) is a major component of cerebrovascular amyloid deposits: implications for the pathology of Alzheimer disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(22):10836–10840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lannfelt L, Basun H, Vigo-Pelfrey C, et al. Amyloid β-peptide in cerebrospinal fluid in individuals with the Swedish Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein mutation. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;199(3):203–206. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12059-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andreasen N, Hesse C, Davidsson P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid(1-42) in Alzheimer disease: differences between early- and late-onset Alzheimer disease and stability during the course of disease. Archives of Neurology. 1999;56(6):673–680. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Galasko D, Chang L, Motter R, et al. High cerebrospinal fluid tau and low amyloid β42 levels in the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and relation to apolipoprotein E genotype. Archives of Neurology. 1998;55(7):937–945. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hampel H, Teipel SJ, Fuchsberger T, et al. Value of CSF β-amyloid1-42 and tau as predictors of Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Molecular Psychiatry. 2004;9(7):705–710. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lewczuk P, Esselmann H, Otto M, et al. Neurochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia by CSF Aβ42, Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and total tau. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25(3):273–281. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mulder C, Schoonenboom SNM, Wahlund L-O, et al. CSF markers related to pathogenetic mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2002;109(12):1491–1498. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0763-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jensen M, Schröder J, Blomberg M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 is increased early in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and declines with disease progression. Annals of Neurology. 1999;45(4):504–511. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199904)45:4<504::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Csernansky JG, Miller JP, McKeel D, Morris JC. Relationships among cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2002;16(3):144–149. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Parsadanian M, et al. Plaque-associated disruption of CSF and plasma amyloid-β (Aβ) equilibrium in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;81(2):229–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hulstaert F, Blennow K, Ivanoiu A, et al. Improved discrimination of AD patients using β-amyloid (1-42) and tau levels in CSF. Neurology. 1999;52(8):1555–1562. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.8.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Riemenschneider M, Wagenpfeil S, Diehl J, et al. Tau and Aβ42 protein in CSF of patients with frontotemporal degeneration. Neurology. 2002;58(11):1622–1628. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sjögren M, Minthon L, Davidsson P, et al. CSF levels of tau, β-amyloid1-42 and GAP-43 in frontotemporal dementia, other types of dementia and normal aging. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2000;107(5):563–579. doi: 10.1007/s007020070079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cairns NJ, Ikonomovic MD, Benzinger T, et al. Absence of Pittsburgh compound B detection of cerebral amyloid β in a patient with clinical, cognitive, and cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer disease: a case report. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66(12):1557–1562. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, et al. Prediction of Alzheimer’s disease using the CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2007;23(5):316–320. doi: 10.1159/000100926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lewczuk P, Esselmann H, Meyer M, et al. The amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide pattern in cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence of a novel carboxyterminally elongated Aβ peptide. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2003;17(12):1291–1296. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schoonenboom NS, Mulder C, Van Kamp GJ, et al. Amyloid β 38, 40, and 42 species in cerebrospinal fluid: more of the same? Annals of Neurology. 2005;58(1):139–142. doi: 10.1002/ana.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Portelius E, Price E, Brinkmalm G, et al. A novel pathway for amyloid precursor protein processing. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.06.002. Neurobiology of Aging. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Andreasson U, et al. An Alzheimer’s disease-specific β-amyloid fragment signature in cerebrospinal fluid. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;409(3):215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin W-L, et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293(5534):1487–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mandelkow E-M, Mandelkow E. Tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends in Cell Biology. 1998;8(11):425–427. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goedert M. Tau protein and the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends in Neurosciences. 1993;16(11):460–465. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90078-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Iqbal K, Alonso ADC, Gong C-X, et al. Mechanisms of neurofibrillary degeneration and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles. Journal of Neural Transmission, Supplement. 1998;(53):169–180. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6467-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vandermeeren M, Mercken M, Vanmechelen E, et al. Detection of τ proteins in normal and Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid with a sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1993;61(5):1828–1834. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb09823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morikawa Y-I, Arai H, Matsushita S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau protein levels in demented and nondemented alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23(4):575–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hu YY, He SS, Wang X, et al. Levels of nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated tau in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients: an ultrasensitive bienzyme-substrate-recycle enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. American Journal of Pathology. 2002;160(4):1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62554-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hampel H, Buerger K, Zinkowski R, et al. Measurement of phosphorylated tau epitopes in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer disease: a comparative cerebrospinal fluid study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(1):95–102. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koopman K, Le Bastard N, Martin J-J, Nagels G, De Deyn PP, Engelborghs S. Improved discrimination of autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from non-AD dementias using CSF P-tau181P. Neurochemistry International. 2009;55(4):214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li G, Sokal I, Quinn JF, et al. CSF tau/Aβ42 ratio for increased risk of mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Neurology. 2007;69(7):631–639. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000267428.62582.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maji SK, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Inayathullah M, et al. Amino acid position-specific contributions to amyloid β-protein oligomerization. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(35):23580–23591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kirkitadze MD, Bitan G, Teplow DB. Paradigm shifts in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders: the emerging role of oligomeric assemblies. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2002;69(5):567–577. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Klein WL, Stine WB, Jr., Teplow DB. Small assemblies of unmodified amyloid β-protein are the proximate neurotoxin in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25(5):569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Aβ oligomers—a decade of discovery. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;101(5):1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416(6880):535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Oda T, Wals P, Osterburg HH, et al. Clusterin (apoJ) alters the aggregation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ 1-42) and forms slowly sedimenting Aβ complexes that cause oxidative stress. Experimental Neurology. 1995;136(1):22–31. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ 1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(11):6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Walsh DM, Hartley DM, Kusumoto Y, et al. Amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis. Structure and biological activity of protofibrillar intermediates. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(36):25945–25952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hartley DM, Walsh DM, Ye CP, et al. Protofibrillar intermediates of amyloid β-protein induce acute electrophysiological changes and progressive neurotoxicity in cortical neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(20):8876–8884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08876.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chen Q-S, Kagan BL, Hirakura Y, Xie C-W. Impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation by Alzheimer amyloid β-peptides. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2000;60(1):65–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000401)60:1<65::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nalbantoglu J, Tirado-Santiago G, Lahsaïni A, et al. Impaired learning and LTP in mice expressing the carboxy terminus of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1997;387(6632):500–505. doi: 10.1038/387500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Blaine Stine W, Jr., Baker LK, Krafft GA, Ladu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(35):32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Klyubin I, Walsh DM, Cullen WK, et al. Soluble Arctic amyloid β protein inhibits hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19(10):2839–2846. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang H-W, Pasternak JF, Kuo H, et al. Soluble oligomers of β amyloid (1-42) inhibit long-term potentiation but not long-term depression in rat dentate gyrus. Brain Research. 2002;924(2):133–140. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-β protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(1):79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.De Felice FG, Vieira MNN, Meirelles MNL, Morozova-Roche LA, Dobson CM, Ferreira ST. Formation of amyloid aggregates from human lysozyme and its disease-associated variants using hydrostatic pressure. FASEB Journal. 2004;18(10):1099–1101. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1072fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Head E, Pop V, Vasilevko V, et al. A two-year study with fibrillar beta-amyloid (Abeta) immunization in aged canines: effects on cognitive function and brain Abeta. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(14):3555–3566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0208-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.White JA, Manelli AM, Holmberg KH, Van Eldik LJ, LaDu MJ. Differential effects of oligomeric and fibrillar amyloid-β1-42 on astrocyte-mediated inflammation. Neurobiology of Disease. 2005;18(3):459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Demuro A, Mina E, Kayed R, Milton SC, Parker I, Glabe CG. Calcium dysregulation and membrane disruption as a ubiquitous neurotoxic mechanism of soluble amyloid oligomers. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(17):17294–17300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chong YH, Shin YJ, Lee EO, et al. ERK1/2 activation mediates Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity via caspase-3 activation and Tau cleavage in rat organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(29):20315–20325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lesné S, Ming TK, Kotilinek L, et al. A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440(7082):352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Townsend M, Shankar GM, Mehta T, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Effects of secreted oligomers of amyloid β-protein on hippocampal synaptic plasticity: a potent role for trimers. Journal of Physiology. 2006;572(2):477–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kuo Y-M, Emmerling MR, Vigo-Pelfrey C, et al. Water-soluble Aβ (N-40, N-42) oligomers in normal and Alzheimer disease brains. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(8):4077–4081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, et al. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300(5618):486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL, et al. Alzheimer’s disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric Aβ ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(18):10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pitschke M, Prior R, Haupt M, Riesner D. Detection of single amyloid β-protein aggregates in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheirner’s patients by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(7):832–834. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Georganopoulou DG, Chang L, Nam J-M, et al. Nanoparticle-based detection in cerebral spinal fluid of a soluble pathogenic biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(7):2273–2276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409336102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lee J-M, Blennow K, Andreasen N, et al. The brain injury biomarker VLP-1 is increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer disease patients. Clinical Chemistry. 2008;54(10):1617–1623. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.104497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rosengren LE, Karlsson J-E, Sjögren M, Blennow K, Wallin A. Neurofilament protein levels in CSF are increased in dementia. Neurology. 1999;52(5):1090–1093. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sjögren M, Davidsson P, Gottfries J, et al. The cerebrospinal fluid levels of tau, growth-associated protein-43 and soluble amyloid precursor protein correlate in Alzheimer’s disease, reflecting a common pathophysiological process. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2001;12(4):257–264. doi: 10.1159/000051268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Praticò D. Alzheimer’s disease and oxygen radicals: new insights. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2002;63(4):563–567. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00919-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Montine TJ, Beal MF, Cudkowicz ME, et al. Increased CSF F2-isoprostane concentration in probable AD. Neurology. 1999;52(3):562–565. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Praticò D, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ, Rokach J, Fitzgerald GA. Increased F2-isoprostanes in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for enhanced lipid peroxidation in vivo. FASEB Journal. 1998;12(15):1777–1783. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.15.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Montine TJ, Kaye JA, Montine KS, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid abeta42, tau, and f2-isoprostane concentrations in patients with Alzheimer disease, other dementias, and in age-matched controls. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2001;125(4):510–512. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0510-CFATAF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Harigaya Y, Shoji M, Nakamura T, Matsubara E, Hosoda K, Hirai S. Alpha 1-antichymotrypsin level in cerebrospinal fluid is closely associated with late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Internal Medicine. 1995;34(6):481–484. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.34.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pirttila T, Mehta PD, Frey H, Wisniewski HM. α1-Antichymotrypsin and IL-1β are not increased in CSF or serum in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 1994;15(3):313–317. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Blum-Degena D, Müller T, Kuhn W, Gerlach M, Przuntek H, Riederer P. Interleukin-1β and interleukin-6 are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s and de novo Parkinson’s disease patients. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;202(1-2):17–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Jia JP, Meng R, Sun YX, Sun WJ, Ji XM, Jia LF. Cerebrospinal fluid tau, Aβ1-42 and inflammatory cytokines in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;383(1-2):12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Martínez M, Fernández-Vivancos E, Frank A, De La Fuente M, Hernanz A. Increased cerebrospinal fluid Fas (Apo-1) levels in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship with IL-6 concentrations. Brain Research. 2000;869(1-2):216–219. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yamada K, Kono K, Umegaki H, et al. Decreased interleukin-6 level in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;186(2-3):219–221. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11318-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Engelborghs S, De Brabander M, De Crée J, et al. Unchanged levels of interleukins, neopterin, interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurochemistry International. 1999;34(6):523–530. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.März P, Heese K, Hock C, et al. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble forms of IL-6 receptors are not altered in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;239(1):29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00886-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tarkowski E, Blennow K, Wallin A, Tarkowski A. Intracerebral production of tumor necrosis factor-α, a local neuroprotective agent, in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 1999;19(4):223–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1020568013953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Teunissen CE, de Vente J, Steinbusch HWM, De Bruijn C. Biochemical markers related to Alzheimer’s dementia in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Neurobiology of Aging. 2002;23(4):485–508. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Flirski M, Sobow T. Biochemical markers and risk factors of Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 2005;2(1):47–64. doi: 10.2174/1567205052772704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurology. 2007;6(8):734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]