Abstract

We previously showed that agonistic antibodies to CD40 could substitute for CD4 T-cell help and prevent reactivation of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) in the lungs of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II−/− (CII−/−) mice, which are CD4 T cell deficient. Although CD8 T cells were required for this effect, no change in their activity was detected in vitro. A key question was whether anti-CD40 treatment (or CD4 T-cell help) changed the function of CD8 T cells or another cell type in vivo. To address this question, in the present study, we showed that adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells from virus-infected wild-type mice or anti-CD40-treated CII−/− mice caused a significant reduction in lung viral titers, in contrast to those from control CII−/− mice. Anti-CD40 treatment also greatly prolonged survival of infected CII−/− mice. This confirms that costimulatory signals cause a change in CD8 T cells enabling them to maintain effective long-term control of MHV-68. We investigated the nature of this change and found that expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 was significantly increased on CD8 T cells in the lungs of MHV-68-infected CII−/−, CD40−/−, or CD80/86−/− mice, compared with that in wild-type or CD28/CTLA4−/− mice, correlating with the level of viral reactivation. Furthermore, blocking PD-1-PD-L1 interactions significantly reduced viral reactivation in CD4 T-cell-deficient mice. In contrast, the absence of another inhibitory receptor, NKG2A, had no effect. These data suggest that CD4 T-cell help programs a change in CD8 T-cell function mediated by altered PD-1 expression, which enables effective long-term control of MHV-68.

Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) is a naturally occurring rodent pathogen which is closely related to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (17, 64). Intranasal administration of MHV-68 to mice results in acute productive infection of lung epithelial cells and a latent infection in various cell types, including B lymphocytes, dendritic cells, epithelial cells, and macrophages (18, 19, 52, 53, 61, 65). The virus induces an inflammatory infiltrate in the lungs, lymph node enlargement, splenomegaly, and mononucleosis comprising increased numbers of activated CD8 T cells in the blood (53, 58). It has also been reported to induce lymphoproliferative disease/lymphoma in immunocompromised mice (30, 55, 60). Thus, the pathogenesis resembles that of EBV in humans, although structurally, the virus is more closely related to KSHV.

Infectious MHV-68 is cleared from the lungs by a T-cell-dependent mechanism 10 to 15 days after infection (18, 53, 56). In wild-type mice, the lungs remain clear of replicating virus thereafter. Although CD4 T cells are not essential for primary clearance of replicating virus, they are required for effective long-term control (11). Thus, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II−/− mice that lack CD4 T cells or mice rendered CD4 deficient by antibody treatment initially clear infectious virus from the lungs. However, infectious virus reactivates in the lungs 10 to 15 days later and gradually increases in titer (11, 43). The infected CD4-deficient mice eventually die, apparently from long-term lung damage due to continuing lytic viral replication (11). MHC class II−/− mice do not produce antibody to T-dependent antigens (10). Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes have been identified in open reading frame (ORF) 6 (p56, H-2Db-restricted), and ORF 61 (p79, H-2Kb-restricted) gene products, which appear to encode early lytic-phase proteins (32, 49). The epitopes are presented during two distinct phases during MHV-68 infection, which changes the pattern of CTL dominance (32, 51). However, there is no significant difference in the numbers of CD8 T cells specific for each epitope in wild-type mice and CD4 T-cell-deficient mice (4, 50). In addition, CTL activity measured in vitro does not differ substantially in the lungs of wild-type mice or CD4 T-cell-deficient mice (4, 11, 50). Furthermore, postexposure vaccination with the p56 epitope failed to prevent viral reactivation in class II−/− mice, despite dramatically expanding the number of CD8 T cells specific for the peptide (5). In contrast, vaccination of wild-type mice against these epitopes reduced lytic viral titers in the lung dramatically on subsequent challenge with MHV-68. B-cell-deficient mice clear MHV-68 with the kinetics of wild-type mice and do not show viral reactivation in the lungs (13, 61), suggesting that antibody is not essential for control of the virus. Depletion of CD4 T cells during the latent phase of infection in B-cell-deficient mice does not induce viral reactivation, whereas depletion of both CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets provokes viral reactivation in the lungs (52). Short-term depletion of both CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets during the latent phase of infection in wild-type mice does not lead to viral reactivation probably due to the presence of neutralizing antibody (11). Taken together, these results suggest that CD4 and CD8 T cells and B cells play overlapping roles in preventing or controlling reactivation of MHV-68 during the latent phase of infection. However, the B-cell- and CD8 T-cell-mediated control mechanisms do not develop in the absence of CD4 T cells.

We, and others, have previously shown that the costimulatory molecule CD28 is not required for long-term control of MHV-68 (28, 29). However, interestingly, mice lacking both of the ligands for CD28, CD80 and CD86, show viral reactivation in the lung (21, 35). Our previously published data showed that agonistic antibodies to CD40 could substitute for CD4 T-cell function in the long-term control of MHV-68 (46). CD8 T-cell receptor-positive (TCR+) cells were required for this effect, while antibody production was not restored (45, 46). MHV-68-infected CD40L−/− mice (7) and CD40−/− mice (29) also showed viral reactivation in the lungs. However, no change in CD8 CTL activity was detected in in vitro assays following anti-CD40 treatment (46). A key question was whether anti-CD40 treatment (or CD4 T-cell help) caused a direct change in CD8 T-cell function or whether both CD8 T cells and an independent anti-CD40-sensitive step were required for viral control. To address this question, we used adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells from MHV-68-infected wild-type mice, anti-CD40-treated mice, or control MHC class II−/− mice to MHV-68-infected class II−/− recipients. We also investigated whether anti-CD40 treatment prolonged survival in addition to reducing lung viral titers. The heterodimeric molecule CD94/NKG2A has been implicated in negatively regulating the CD8 T-cell response to polyomavirus (38) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) (54), while the inhibitory receptor PD-1 (programmed death 1) has been implicated in T-cell exhaustion following infection with several other persistent viruses (2, 15, 20, 22, 26, 36, 39-41, 57, 67). In the present study, we investigated the effect of signaling via various costimulatory molecules on the expression of NKG2A and PD-1 and how these molecules influenced viral control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Age-matched 6- to 12-week-old female mice were used in all experiments. C57BL/6 mice that were homozygous for a disruption in the IAb gene (MHC class II−/−) (10) were purchased from Taconic Farms. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory or Taconic Farms. DBA/1, DBA/2, CD40−/−, and CD80/86−/− (double-deficient) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. CD28/CTLA4−/− (double-deficient) mice were obtained from a breeding colony established from pairs kindly supplied by Arlene Sharpe (Harvard University). Mice were bred and housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions in the animal resource center at the Torrey Pines Institute for Molecular Studies (TPIMS). All experiments were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of TPIMS, in compliance with the National Institutes of Health U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the care and use of animals.

Viral infection and sampling.

Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) was propagated in BHK-21 cells (ATCC CCL-10). Mice were infected intranasally with 5 × 104 PFU of the virus in phosphate-buffered saline. At the specified time points after infection, mice were terminally anesthetized with Avertin. The inflammatory cells infiltrating the lungs were harvested by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) via the trachea, and single-cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen, as previously described (1). The lungs were removed and homogenized in medium on ice prior to virus titration.

A hybridoma secreting FGK45, an agonistic antibody to CD40 (42) was kindly provided by F. Melchers and A. Rolink. The antibody was purified from culture supernatants by protein G Sepharose chromatography. Class II−/− mice were treated with either 100 μg/mouse anti-CD40 or isotype control antibody administered intravenously (i.v.) on days 1 and 15 postinfection, unless otherwise noted. In some experiments, groups of wild-type C57BL/6, DBA/1, or DBA/2 mice were depleted of CD4 T cells using anti-CD4 antibody GK1.5 (0.5 mg/mouse every 2 or 3 days) or treated with rat Ig as a control, commencing at day −1 for 14 days and weekly thereafter. Blocking antibodies against PD-1 (programmed death 1) (RMP114), PD-L1 (programmed death ligand 1) (MIH5), and PD-L2 (TY25) were prepared as described previously (59, 66), and 0.25 mg/mouse was administered every 2 or 3 days from day 35 postinfection.

Adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells.

CD8 T cells were prepared from spleen and lymph node cell populations by negative selection using a CD8 T-cell subset preparation column kit (R&D Systems, ME) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Red blood cells (RBC) in the cell suspensions were lysed prior to CD8 T-cell enrichment, by using Tris ammonium chloride buffer. A total of 3 × 106 purified CD8 cells were administered intravenously to recipient mice, which had been lightly irradiated (300 rads) 1 day earlier.

Virus titration.

The titers of replicating virus were determined by plaque assay on NIH 3T3 cells (ATCC CRL1658) as described previously (11). Briefly, dilutions of stock virus or homogenized mouse lungs were adsorbed onto NIH 3T3 monolayers for 1 h at 37°C and overlaid with carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). After 6 days, the CMC overlay was removed, and the monolayers were fixed with formalin and stained with crystal violet to facilitate determination of the number of plaques. The detection limit of this assay is 10 PFU/0.1 g lung tissue based on plaques recovered from homogenates of uninfected lung or splenocytes, spiked with known amounts of virus.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)- or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies as previously described (44). Antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA), eBiosciences (San Diego, CA), or BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Isotype controls were included in each assay. Mouse adsorbed PE-conjugated goat anti-rat (Fab′)2 (SBA, Birmingham, AL) was used as a secondary reagent to detect cell-surface-bound unconjugated rat antibodies used in blocking studies.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed with SigmaStat software (Jandel Scientific, St. Rafael, CA) using Student's t test or the Mann-Whitney rank sum test, depending on whether the data were normally distributed. Survival curve analysis was performed with Graphpad Prism software using a log rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

RESULTS

CD4 T-cell help programs a change in CD8 T-cell function leading to effective viral control and prolonged survival.

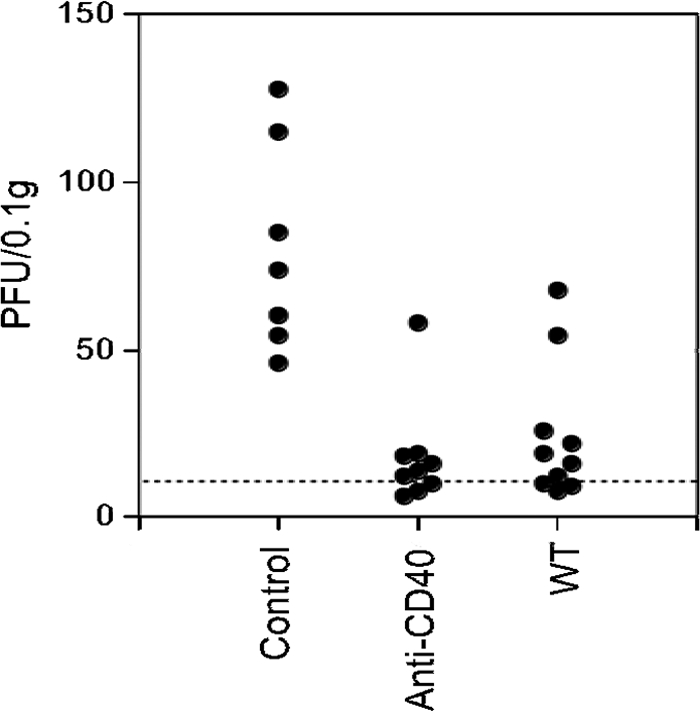

Mice lacking CD4 T cells initially control MHV-68 but later show viral reactivation in the lungs (11). The interaction of CD40 on antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, with CD40L on CD4 T cells appears to be an important component of this effect (7, 23, 29, 46). Our previous data (46) showed that agonistic antibodies to CD40 could prevent reactivation of MHV-68 in CD4 T-cell-deficient mice and that CD8 T cells were required for this effect. However, no change in CD8 CTL activity was detected in in vitro assays. A key question was whether anti-CD40 treatment caused a direct change in CD8 T-cell function or whether both CD8 T-cell activity and a separate anti-CD40-sensitive process were required for viral control. To address this question, we used adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells from MHV-68-infected wild-type mice, anti-CD40-treated mice, or control MHC class II−/− mice to MHV-68-infected class II−/− recipients and compared lung viral titer in the three groups at day 42 postinfection. The results showed that adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells from virus-infected wild-type mice or anti-CD40-treated class II−/− mice caused a significant reduction in lung viral titers compared to those in recipients of CD8 T cells from control class II−/− mice (Fig. 1). This confirms that anti-CD40 treatment causes a change in CD8 T-cell function enabling them to maintain effective long-term control of virus. Similarly, in wild-type mice, CD40 stimulation is provided via CD40L on CD4 T cells.

FIG. 1.

Anti-CD40 treatment induces a change in CD8 T-cell function. Groups of donor or recipient MHC class II−/− (CII−/−) mice or donor wild-type (WT) mice were infected with MHV-68 (5 × 104 PFU intranasally [i.n.]). Donor class II−/− mice were treated with either 100 μg/mouse anti-CD40 or isotype control antibody i.v. on days 1 and 15 postinfection. At day 18 after infection, donor mice were killed, and CD8 T cells were purified by negative selection from pooled lymph node and spleen cells from each group. A total of 3 × 106 purified CD8 cells were administered intravenously to the recipient mice, which had been lightly irradiated (300 rads) 1 day earlier. Virus titers in the lungs were determined by plaque assay at day 42 after infection. Data are pooled from two independent experiments, and each symbol represents the titer for an individual mouse. There was a highly significant difference between the lung virus titers in mice that had received cells from control antibody-treated and anti-CD40-treated CII−/− donors (P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test) or wild-type donors (P = 0.003). The dashed line represents the limit of detection.

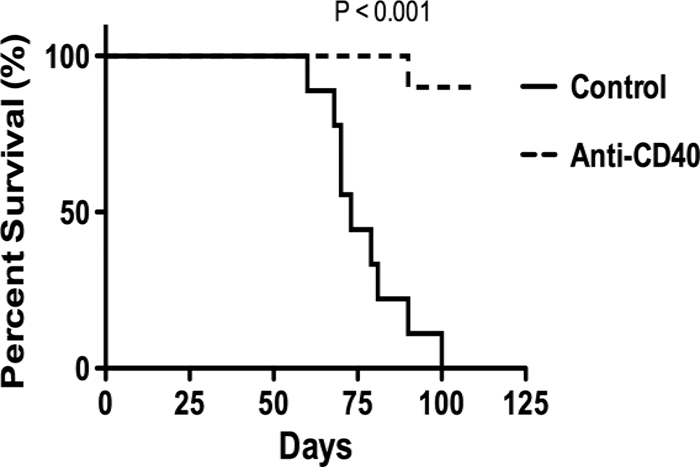

We further tested the longevity and biological significance of this observation by determining its effect on survival. The majority of MHV-68-infected class II−/− mice treated with anti-CD40 were still alive 120 days after infection (Fig. 2) and did not show detectable levels of viral reactivation in the lungs. Additional supportive antibiotic treatment was required to maintain long-term survival in this group, as bacterial respiratory infections remained a problem. In separate experiments, we determined that this antibiotic treatment had no effect on either viral clearance or reactivation (data not shown). In contrast, control rat Ig-treated class II−/− mice showed viral reactivation from day 25 to 30 onwards, and the majority of control class II−/− mice infected with MHV-68 died between days 60 and 80 after infection, presumably due to the effects of long-term viral replication in the lungs. All mice in this group were dead by day 100 postinfection.

FIG. 2.

Anti-CD40 treatment increases survival of MHV-68-infected MHC class II−/− mice. Groups of 5 MHC class II−/− mice were infected with MHV-68 and treated with either 100 μg/mouse anti-CD40 or isotype control antibody i.v. on days 1 and 15 postinfection. Control groups of wild-type mice were also infected with MHV-68. Mice were observed for 125 days after infection. Data are representative of two independent experiments that gave similar results. There was a highly statistically significant difference in survival between anti-CD40-treated mice and control class II−/− mice (P < 0.001, log rank [Mantel Cox] test).

Phenotypic changes in CD8 T cells in the presence and absence of “help.”

In order to determine the nature of the changes induced in CD8 T cells by CD4 T-cell help, we compared the surface expression of a range of costimulatory or inhibitory molecules, activation markers, and molecules associated with cytoxicity or cell death on the surfaces of CD8 T cells from wild-type mice versus CD4 T-cell-deficient mice. We also determined the effect of anti-CD40 treatment of MHC class II−/− mice on the expression of these cell surface molecules. Similar proportions of CD8 T cells from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid samples from control or anti-CD40-treated class II−/− mice expressed the memory or activation markers CD62L, CD44, and CD69. Very low proportions of CD8 T cells from BAL fluid samples from wild-type mice, control mice, or anti-CD40-treated class II−/− mice expressed the cytotoxic molecules FasL, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand), or the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD40L, and CD28 (Table 1). The proportion of CD8 T cells expressing high levels of the activation markers CD69 and CD44 was significantly higher in class II−/− mice than in wild-type mice. However, the proportions of cells expressing these markers were similar in control mice and anti-CD40-treated class II−/− mice, suggesting that they reflected conditions in the class II−/− environment, rather than the ability of the CD8 T cells to control virus. A significant reduction in the proportion of CD8 cells expressing the inhibitory receptor NKG2A was noted in the BAL fluid samples from anti-CD40-treated class II−/− mice compared with that in control class II−/− mice (P < 0.001, Student's t test). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for NKG2A (which relates to the level of expression on cells positive for this marker) was also significantly higher in control mice than in anti-CD40-treated class II−/− or wild-type mice. Values for the anti-CD40-treated group were similar to those in wild-type mice. Although we originally used clone 20d5 (BD Pharmingen), which recognizes NKG2A/C and NKG2E, we repeated the staining using an antibody that was specific for NKG2A (clone 16A11, a kind gift of David Raulet) (62, 63). The staining was similar for each antibody, suggesting that NKG2C and NKG2E were not expressed at detectable levels on CD8 T cells from the BAL fluid samples from MHV-68-infected mice (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Changes in the phenotype of CD8+ cells from BAL fluid samples induced by treating MHC class II−/− mice with an agonistic antibody to CD40a

| Cell surface marker | % Positiveb,d |

MFIc,d |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Anti-CD40 | WT | Control | Anti-CD40 | WT | |

| CD28 | LL | LL | LL | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.4 |

| CD40 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | ND | ND | ND |

| CD40L | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| CD44 | 60.4 ± 1.9 | 64.9 ± 1.9 | 34.8 ± 14.9** | 796 ± 4.6 | 740 ± 54 | 708 ± 119 |

| CD54 | 55.1 ± 4.2 | 33.6 ± 14.1 | 31.8 + 15.0 | 23.6 ± 4.2 | 20.3 ± 2.4 | 28.7 + 2.9 |

| CD62L | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 4.7 ± 1.4 | ND | ND | ND |

| CD69 | 27.8 ± 4.7 | 33.5 ± 3.4 | 13.1 + 2.9*** | 193 ± 119 | 131 ± 70 | 227 + 172 |

| CD95L | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 4.1 | 2.3 ± 1.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| TNF | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 2.8 ± 2.8 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 41BB | LL | LL | LL | 4.9 ± 2.2 | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 5.8 |

| NKG2A | 28.6 ± 3.0 | 17.1 ± 2.0*** | 18.3 ± 5.4*** | 31.8 ± 5.8 | 22.6 ± 1.2*** | 21.1 ± 6.5** |

| TRAIL | LL | LL | LL | ND | ND | ND |

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 or MHC class II−/− mice were infected intranasally with MHV-68, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid cells were harvested 50 days after infection. MHC class II−/− mice were treated with 100 μg of either isotype control antibody (control) or anti-CD40 antibody at days 1 and 15 postinfection. BAL fluid cells were dual stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies to CD8 and the cell surface markers shown above. Labeled cell populations were analyzed by flow cytometry. Forward scatter and side scatter were used to gate the lymphocyte population. Results are mean ± standard deviations for BAL fluid samples from 2 or 3 independent experiments (with the exception of data for 41BB and CD54 which were from single experiments) with 3 to 5 mice analyzed individually per group for each experiment.

Percentage of BAL fluid cells positive for both CD8 and the specified marker. LL, low levels expressed on all cells.

Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the BAL fluid cells positive for both CD8 and the specified marker, except for the cells marked LL in the % Positive columns, where the MFI of the whole population is shown. ND, not determined due to the low number of events in the positive population.

Values for anti-CD40-treated or wild-type and control groups that are statistically significantly different by Student's t test are indicated as follows: **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Role of NKG2A in the compromised immune response to MHV-68 in CD4 T-cell-deficient mice.

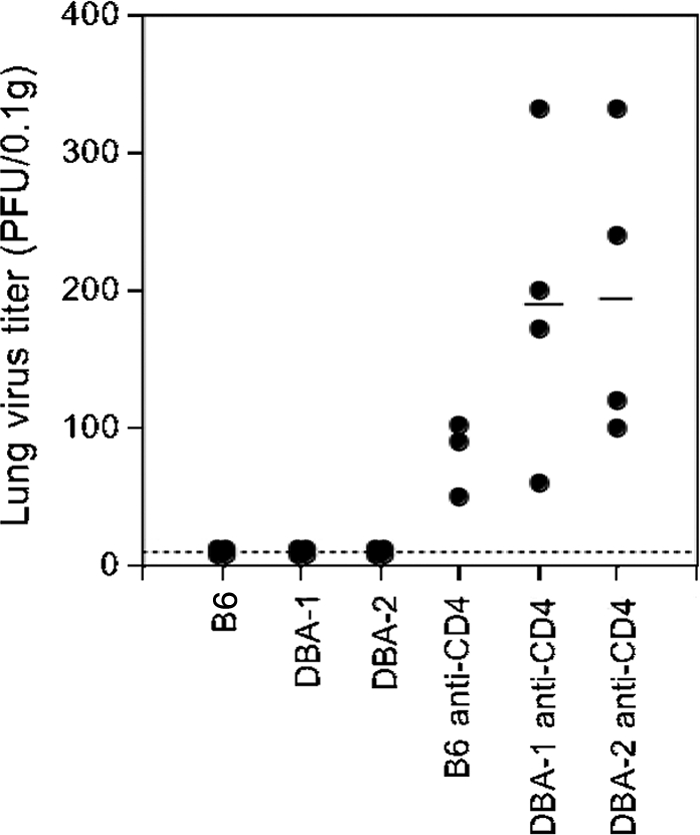

The heterodimeric molecule CD94-NKG2A was originally described as an NK cell inhibitory receptor (62, 63), but it has also been shown to mediate inhibition of CD8 T-cell function in a mouse polyomavirus model (38). To address the role of this molecule in the response to MHV-68, we compared the long-term control of MHV-68 in DBA/1 and DBA/2 mice that had been depleted of CD4 T cells starting immediately prior to infection. DBA/2 mice, unlike DBA/1 mice, are naturally deficient in CD94 and hence also lack cell surface expression of NKG2A, as CD94 is required for surface expression of NKG2A (62). If the upregulated CD94/NKG2A had an inhibitory effect on CD8 T-cell function in the absence of CD4 T cells resulting in viral reactivation, we would predict that CD4 T-cell-depleted DBA/2 mice would show effective control of the virus, while DBA/1 mice would show the expected viral reactivation in the lungs. However, there was no difference in viral reactivation in the lungs between the two groups of mice (Fig. 3). Thus, it seems unlikely that the increase in NKG2A expression could explain the decrease in CD8 T-cell function in CD4 T-cell-deficient mice. This led us to investigate the expression of other potentially inhibitory molecules on the surfaces of CD8 T cells in class II−/− mice.

FIG. 3.

Absence of CD94/NKG2A does not prevent viral reactivation in CD4 T-cell-deficient mice. Groups of C57/BL/6 (B6) mice and DBA/1 and DBA/2 mice (lacking surface expression of NKG2A) were infected with MHV-68 intranasally and depleted of CD4 T cells by treatment every 2 or 3 days with monoclonal antibody (MAb) GK1.5 (0.5 mg/ml intraperitoneally [i.p.]) for 14 days and weekly thereafter. Control groups of infected mice were not depleted of CD4 cells. Viral titers in lung homogenates were determined by plaque assay on NIH 3T3 cell monolayers. The symbols show the titers from individual animals, and the black bar shows the mean for each group of mice. The dashed line represents the limit of detection. The data are representative data from two independent experiments that gave similar results.

Increased expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 on the surfaces of CD8 T cells in mice lacking CD4 T cells.

PD-1 is another inhibitory receptor that is expressed on the surfaces of CD8 T cells and has been implicated in CD8 T-cell exhaustion in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infections (2, 67) and HIV infections (15, 40, 57, 67). An initial study of mRNA expression of various molecules in enriched CD8 T-cell populations isolated from BAL fluid samples from MHV-68-infected mice showed that PD-1 expression was upregulated in CD8 T cells from control MHC class II−/− mice compared with those from wild-type or anti-CD40-treated class II−/− mice (data not shown). We confirmed the influence of CD4 cells on PD-1 expression in CD8 T cells by flow cytometric analysis. The results in Fig. 4 A and B show that PD-1 is dramatically upregulated on CD8 T cells from BAL fluid samples from CD4 T-cell-deficient mice compared with that on CD8 T cells from wild-type mice. Thus, the majority of CD8 T cells from BAL fluid samples from CD4 T-cell-deficient mice expressed high levels of PD-1 at day 50 postinfection (when the CD8 T cells are not effective in preventing viral reactivation), whereas a much lower proportion of CD8 T cells from wild-type mice (which showed no reactivation) expressed PD-1 at this time point. A similar difference in PD-1 expression was observed in control and CD4 T-cell-depleted, B-cell-deficient mice or CD4 T-cell-depleted, J-chain-deficient mice, (kindly provided by M. Shlomchik [31]) in which B-cell development, but not antiviral antibody production, had been rescued by the transgenic expression of an immunoglobulin molecule (data not shown). This suggests that the increase in PD-1 expression reflects the CD4 T-cell-deficient environment rather than a lack of antibody production or other B-cell functions.

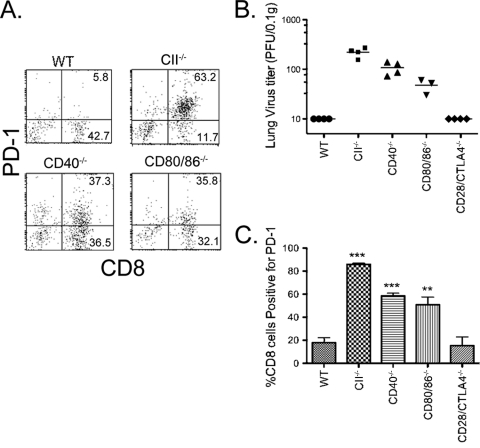

FIG. 4.

Increased expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 on the surfaces of CD8 T cells in the lungs of mice lacking CD4 T cells and its role in viral reactivation. MHC class II−/− mice (which are CD4 T cell deficient) or wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected i.n. with MHV-68. Infiltrating cells were harvested from the lung by bronchoalveolar lavage via the trachea at day 50 postinfection and dual stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 and PE-conjugated anti-PD-1. (A) Representative dot plots of PD-1 and CD8 expression in BAL fluid samples from wild-type and MHC class II−/− (CII−/−) mice. (B) Mean percentage of CD8 T cells that were positive (+ve)for PD-1 in BAL fluid samples from wild-type and MHC class II−/− mice. Mean percentages plus standard deviations (SDs) (error bars) are shown. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. The values for the two groups of mice were statistically highly significantly different (P < 0.001, Student's t test) (***). (C) Blocking PD-1-PD-L1 interactions reduces reactivation of MHV-68 in MHC class II−/− mice. Groups of 4 or 5 MHC class II−/− mice were infected intranasally with MHV-68 and treated with 0.2 mg/mouse i.p. of either anti-PD-1 (RMP114), anti-PD-L2 (TY25), or anti-PD-L1 (MIH5) antibody every 2 or 3 days from day 35 postinfection onwards. Control groups were treated with rat Ig (0.2 mg/mouse every 2 or 3 days). Groups of wild-type mice were also infected as additional controls. Lung virus titers were determined at day 50 after infection by plaque assay. The symbols represent titers for individual mice, and the horizontal bar shows the mean for each group. The dashed line indicates the detection limit. The data are combined from two independent experiments that gave similar results. There was a statistically significant difference between lung viral titers in control and anti-PD-1-treated class II−/− mice (P = 0.02, Mann-Whitney rank sum test), anti-PD-L1-treated class II−/− mice (P = 0.04) or wild-type mice (P < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between lung virus titers in control and anti-PD-L2-treated class II−/− mice.

The dramatic difference in expression of PD-1 on CD8 T cells from wild-type mice versus class II−/− mice suggested that this molecule negatively regulates the function of CD8 T cells in CD4 T-cell-deficient mice, resulting in a compromised ability to prevent viral reactivation. An alternative explanation is that upregulation of PD-1 is a result of viral reactivation, rather than a cause. To distinguish between these possibilities, we blocked PD-1-PD-L1 interactions using monoclonal antibodies to either molecule in class II−/− mice (which lack CD4 T cells). The results showed that blocking PD-1-PD-L1 interactions significantly reduced viral reactivation (Fig. 4C). In contrast, antibodies to PD-L2 had no significant effect. Flow cytometric analysis of BAL fluid cells from mice treated with anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, or anti-PD-L2 showed that the antibodies were nondepleting and that the reduction in viral titers did not significantly reduce the expression of either PD-1 or PD-L1 (Table 2). Thus, upregulation of PD-1 on CD8 T cells in class II−/− mice appears to be a cause, rather than a result, of viral reactivation.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic analysis of CD8 T cells in the BAL fluid samples from MHC class II−/− mice treated with monoclonal antibodies to PD-1 or PD-L1a

| In vivo treatment | % Positive BAL fluid cells |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8 | CD8 and PD-1 | CD8 and PD-L1 | Anti-rat IgG | |

| None (control) | 67.4 ± 3.8 | 48.6 ± 4.9 | 65.0 ± 3.9 | 1.5 ± 1.7 |

| Anti-PD-1 (RMP114) | 68.2 ± 5.0 | 49.2 ± 6.3 | 65.7 ± 4.7 | 56.6 ± 11.9 |

| Anti-PD-L2 (TY25) | 67.8 ± 3.0 | 52.9 ± 5.9 | 66.2 ± 2.0 | 2.1 ± 2.8 |

| Anti-PD-L1 (MIH5) | 72.1 ± 7.1 | 49.7 ± 5.0 | 17.6 ± 4.2 | 58.6 ± 9.9 |

| None (wild-type) | 48.1 ± 4.3 | 8.4 ± 4.7 | 39.8 ± 3.1 | 6.6 ± 4.9 |

Mice were infected with MHV-68 and treated with antibodies to PD-1, PD-L1, and PD-L2 as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Cells from BAL fluid samples were harvested at day 50 postinfection stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 and PE-conjugated anti-PD-1 (clone RMP130 [does not compete with RMP114]), anti-PD-L1 (clone MIH5), or anti-PD-L2 (clone TY25) or with PE-conjugated anti-rat IgG to detect the antibodies used for treatment on the surfaces of the cells from BAL fluid samples. Anti-rat IgG detected the injected anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies on the surfaces of the BAL fluid cells. Very few PD-L2-positive cells were detected (data not shown).

Costimulatory interactions involving CD40 and CD80/86 result in reduced PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells and improved viral control.

To investigate the roles of costimulatory molecules CD40 and CD80/CD86 (CD80/86) in the downregulation of PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells in CD4 T-cell-sufficient mice, we infected wild-type mice, class II−/− mice, CD40−/− mice, or CD80/86−/− mice with MHV-68 and compared the levels of PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells and viral reactivation at day 50 postinfection. PD-1 expression was significantly upregulated on CD8 T cells from CD40−/− and CD80/86−/− mice compared with that on CD8 T cells from wild-type mice (Fig. 5). However, it seemed somewhat lower than that on CD8 T cells from class II−/− mice, correlating with the slightly lower level of viral reactivation in these groups (Fig. 5). In contrast, CD28/CTLA4−/− mice showed no detectable viral reactivation at day 50 and comparable PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells to that in wild-type mice.

FIG. 5.

PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells and lung virus titers in wild-type, class II−/−, CD40−/−, CD80/86−/−, and CD28/CTLA4−/− mice. Groups of 3 to 5 mice, wild-type MHC class II−/−, CD40−/−, CD80/86−/−, and CD28/CTLA4−/− mice, were infected with MHV-68. Infiltrating cells were harvested from the lung by bronchoalveolar lavage via the trachea at day 50 postinfection and dual stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 and PE-conjugated anti-PD-1. (A) Representative dot plots of PD-1 and CD8 expression in BAL fluid samples. The percentage of BAL cells positive for each marker is shown. (B) Lung virus titers were determined at day 50 after infection by plaque assay. Each symbol represents the virus titer for an individual mouse, and the horizontal bar shows the mean. (C) Mean percentages of CD8 T cells that were positive for PD-1 in BAL fluid samples. The mean percentage plus standard error of the mean (SEM) is shown. There was a statistically highly significant difference between the percentage of CD8 T cells positive for PD-1 in the BAL fluid samples from CII−/−, CD40−/−, and CD80/86−/− mice compared with that of wild-type mice (P < 0.001 [***]; P < 0.01 [**]). There was no significant difference in the percentages for wild-type and CD28/CTLA4−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

The results of previous studies implied that CD4 T-cell help was required for CD8 T-cell function in the long-term control of MHV-68 (11). Mice lacking CD4 T cells showed viral reactivation in the lungs, suggesting that the CD8 T cells exhibited a nonfunctional or “exhausted” phenotype. However, various studies failed to detect qualitative or quantitative differences in CD8 T-cell function in wild-type and CD4 T-cell-deficient mice (4, 5, 11, 46, 50). Thus, a key question was whether CD4 T-cell help caused a direct change in CD8 T-cell function or whether both CD8 T-cell activity and a separate helper-dependent process were required for viral control. The results of the current study address this question and show that “help” either from CD4 T cells or in the form of agonistic antibodies to CD40 induces a change in CD8 T-cell function enabling effective control of viral reactivation and significantly increasing survival of the mice. As our previous studies showed that CD40 expression on dendritic cells but not on B or T cells was necessary for long-term control of MHV-68 by CD8 T cells (23), these results suggest that CD40L on CD4 T cells interacts with CD40 on dendritic cells, enabling them to program CD8 T cells in a manner that prevents “exhaustion.”

We conducted further experiments to probe the nature of the specific changes induced in CD8 T cells by “help.” Although the level of the inhibitory receptor NKG2A was upregulated on CD8 T cells in mice lacking CD4 T-cell help in comparison to that in either wild-type or anti-CD40-treated MHC class II−/− mice, our experiments showed that increased NKG2A expression in the absence of CD4 T cells did not cause loss of CD8 T-cell function. Upregulation of this receptor on polyomavirus-specific CD8 T cells has been shown to inhibit tumor rejection and viral clearance (38). However, NKG2A expression is upregulated on activated CD8 T cells (25, 37) and has been reported to inhibit their function in some models (38, 54) but not in others (12). TRAIL has also been implicated in the loss of CD8 T-cell function in the absence of CD4 T-cell help in some systems (25a, 28a). However, we observed no difference in TRAIL expression on “helped” and “nonhelped” CD8 T cells. Both groups showed very low expression of this molecule, suggesting that it does not play a major role in CD8 T-cell function in this persistent viral infection.

Both microarray studies and flow cytometric analysis revealed a significant increase in the expression of PD-1 on CD8 T cells from CD4 T-cell-deficient mice. To determine whether this upregulation of PD-1 had any functional significance, we showed that blocking PD-1-PD-L1 interactions using monoclonal antibodies to either molecule in class II−/− mice (which lack CD4 T cells) significantly reduced viral reactivation, whereas antibodies to PD-L2 had no significant effect. Thus, PD-1-PD-L1 interactions affect the ability of CD8 T cells to control viral reactivation, and the upregulation of PD-1 on CD8 cells is not simply a result of increased viral replication.

These data support the hypothesis that CD4 T cells induce a functional change in CD8 T cells by modulating their PD-1 expression, thus enabling the CD8 T cells to control MHV-68 reactivation and are consistent with reports of a role for PD-1 in mediating CD8 T-cell exhaustion in a number of other persistent viral infections, including LCMV, HIV, vaccinia virus, and hepatitis B and C virus infections (2, 15, 20, 22, 26, 36, 39-41, 57, 67).

However, blocking PD-1-PD-L1 interactions did not completely block viral replication in our study, although optimal doses were used and robust binding of the antibodies to the target cells was observed. A possible explanation of this observation that has been verified in other systems (6) is that multiple inhibitory receptors contribute to CD8 T-cell exhaustion. As mentioned above, the specific inhibitory molecules involved may vary in different viral infections. We are currently investigating the possible role of other inhibitory receptors identified by expression profiling of “helped” and “nonhelped” CD8 T cells in MHV-68 infection.

Our previous data (44) and those of others (28) showed that CD28 was not required for long-term control of MHV-68. However, although CD28 is the only known stimulatory receptor for CD80/86, mice lacking both CD80 and CD86 showed viral reactivation in the lungs (21, 35). CD80 and CD86 appeared to play overlapping functions, as CD80−/− or CD86−/− (singly deficient) mice showed effective long-term control of the virus (35). This lead us to suggest that stimulation of dendritic cells via CD40 upregulates CD80 andCD86, which in turn interact with a novel stimulatory receptor on CD8 T cells, which activates them, enabling them to mediate effective long-term control of MHV-68. An alternative view is that CD80 and CD86 interact with CTLA4 acting in an unusual stimulatory capacity on T cells (it usually negatively regulates T-cell function). There is precedence for this idea, as CTLA4-mediated upregulation of LFA-1 adhesion and clustering has been reported (50). However, in the current study, we show that mice lacking both CD28 and CTLA4 also show effective long-term control of MHV-68, arguing against an unexpected stimulatory role for CTLA4. A negative costimulatory interaction between PD-L1 and CD80 has also been described (9), which is surprising, as both molecules are considered ligands. However, PD-L1 seems unlikely to be the unknown “receptor” in our model, as the costimulatory interaction is positive and both CD80 and CD86 play a role (35), whereas Butte et al. (9) reported that PD-L1 interacted with CD80, but not CD86, resulting in inhibition of T-cell function.

Our data show that CD8 T cells from both CD40−/− and CD80/86−/− mice also show increased expression of PD-1, while CD28/CTLA4−/− mice show levels similar to those in wild-type mice, correlating with the ability of these mouse strains to control viral reactivation in the lungs. These data are consistent with a model in which the effects of CD4 T-cell help on CD8 T-cell function are mediated via the interaction of CD4 T-cell-expressed CD40L and CD40 on the surfaces of dendritic cells, resulting in upregulation of CD80 and CD86. Subsequent binding of CD80 or CD86 with a currently unidentified receptor results in activation of CD8 T cells, mediated in part by downregulation of PD-1 expression.

An outstanding question to be addressed in future studies is which specific function of CD8 T cells is altered by PD-1 upregulation, as at least in vitro, no difference in CTL activity was observed between CD8 T cells from wild-type and CD4 T-cell-deficient mice (4, 11, 50). In other models, blocking PD-1-PD-L1 interactions has been shown to affect CD8 T-cell survival and cytokine production in addition to CTL activity (2, 36, 39, 40, 57). This would suggest a noncytolytic effect of the CD8 cells as described for the control of HSV latency in neuronal ganglia or for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the liver, which are cytokine mediated (16, 24, 27, 33, 34). Cytokines and NFκB activation have also been shown to suppress MHV-68 reactivation from splenic and peritoneal cells in vitro (3, 8, 48). While our data do not show a role for the gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and TNF cytokines, which would be the most likely candidates, it is possible that other cytokines or mediators may be involved in a noncytolytic mechanism of viral control.

In summary, our data support the hypothesis that CD4 T cells induce a functional change in CD8 T cells by modulating their PD-1 expression, thus enabling the CD8 T cells to control viral reactivation. As immunocompromised individuals, such as AIDS patients or transplant recipients on immunosuppressive therapy who have poor CD4 T-cell function, can experience severe and sometimes life-threatening diseases caused by failure to control latent herpesviruses (14, 47), dissecting the mechanisms of long-term control of persistent viral infections and how these differ from mechanisms functioning in the acute control of viral replication will further our understanding of mechanisms of viral pathogenesis and may have practical applications in the design of vaccines and other therapeutic interventions to control persistent viral infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashley Shea and Chandra Inglis for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI050810 and AI057599 and by a grant from the Infectious Disease Science Center.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan, W., Z. Tabi, A. Cleary, and P. C. Doherty. 1990. Cellular events in the lymph node and lung of mice with influenza. Consequences of depleting CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 144:3980-3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber, D. L., E. J. Wherry, D. Masopust, B. Zhu, J. P. Allison, A. H. Sharpe, G. J. Freeman, and R. Ahmed. 2006. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439:682-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton, E. S., M. L. Lutzke, R. Rochford, and H. W. Virgin. 2005. Alpha/beta interferons regulate murine gammaherpesvirus latent gene expression and reactivation from latency. J. Virol. 79:14149-14160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belz, G. T., H. Liu, S. Andreansky, P. C. Doherty, and P. G. Stevenson. 2003. Absence of a functional defect in CD8+ T cells during primary murine gammaherpesvirus-68 infection of I-A(b−/−) mice. J. Gen. Virol. 84:337-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belz, G. T., P. G. Stevenson, M. R. Castrucci, J. D. Altman, and P. C. Doherty. 2000. Postexposure vaccination massively increases the prevalence of gamma-herpesvirus-specific CD8+ T cells but confers minimal survival advantage on CD4-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:2725-2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackburn, S. D., H. Shin, W. N. Haining, T. Zou, C. J. Workman, A. Polley, M. R. Betts, G. J. Freeman, D. A. Vignali, and E. J. Wherry. 2009. Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 10:29-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks, J. W., A. M. Hamilton-Easton, J. P. Christensen, R. D. Cardin, C. L. Hardy, and P. C. Doherty. 1999. Requirement for CD40 ligand, CD4(+) T cells, and B cells in an infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome. J. Virol. 73:9650-9654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, H. J., M. J. Song, H. Deng, T. T. Wu, G. Cheng, and R. Sun. 2003. NF-kappaB inhibits gammaherpesvirus lytic replication. J. Virol. 77:8532-8540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butte, M. J., M. E. Keir, T. B. Phamduy, A. H. Sharpe, and G. J. Freeman. 2007. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity 27:111-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardell, S., M. Merkenschlager, H. Bodmer, S. Chan, D. Cosgrove, C. Benoist, and D. Mathis. 1994. The immune system of mice lacking conventional MHC class II molecules. Adv. Immunol. 55:423-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardin, R. D., J. W. Brooks, S. R. Sarawar, and P. C. Doherty. 1996. Progressive loss of CD8+ T cell-mediated control of a gamma-herpesvirus in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 184:863-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavanaugh, V. J., D. H. Raulet, and A. E. Campbell. 2007. Upregulation of CD94/NKG2A receptors and Qa-1b ligand during murine cytomegalovirus infection of salivary glands. J. Gen. Virol. 88:1440-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen, J. P., R. D. Cardin, K. C. Branum, and P. C. Doherty. 1999. CD4(+) T cell-mediated control of a gamma-herpesvirus in B cell-deficient mice is mediated by IFN-gamma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:5135-5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowe, S. M., J. B. Carlin, K. I. Stewart, C. R. Lucas, and J. F. Hoy. 1991. Predictive value of CD4 lymphocyte numbers for the development of opportunistic infections and malignancies in HIV-infected persons. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 4:770-776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Day, C. L., D. E. Kaufmann, P. Kiepiela, J. A. Brown, E. S. Moodley, S. Reddy, E. W. Mackey, J. D. Miller, A. J. Leslie, C. DePierres, Z. Mncube, J. Duraiswamy, B. Zhu, Q. Eichbaum, M. Altfeld, E. J. Wherry, H. M. Coovadia, P. J. Goulder, P. Klenerman, R. Ahmed, G. J. Freeman, and B. D. Walker. 2006. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 443:350-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decman, V., P. R. Kinchington, S. A. Harvey, and R. L. Hendricks. 2005. Gamma interferon can block herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivation from latency, even in the presence of late gene expression. J. Virol. 79:10339-10347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Efstathiou, S., Y. M. Ho, S. Hall, C. J. Styles, S. D. Scott, and U. A. Gompels. 1990. Murine herpesvirus 68 is genetically related to the gammaherpesviruses Epstein-Barr virus and herpesvirus saimiri. J. Gen. Virol. 71:1365-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehtisham, S., N. P. Sunil-Chandra, and A. A. Nash. 1993. Pathogenesis of murine gammaherpesvirus infection in mice deficient in CD4 and CD8 T cells. J. Virol. 67:5247-5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flano, E., S. M. Husain, J. T. Sample, D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 2000. Latent murine gamma-herpesvirus infection is established in activated B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages. J. Immunol. 165:1074-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman, G. J., E. J. Wherry, R. Ahmed, and A. H. Sharpe. 2006. Reinvigorating exhausted HIV-specific T cells via PD-1-PD-1 ligand blockade. J. Exp. Med. 203:2223-2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuse, S., J. J. Obar, S. Bellfy, E. K. Leung, W. Zhang, and E. J. Usherwood. 2006. CD80 and CD86 control antiviral CD8+ T-cell function and immune surveillance of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 80:9159-9170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuse, S., C. Y. Tsai, M. J. Molloy, S. R. Allie, W. Zhang, H. Yagita, and E. J. Usherwood. 2009. Recall responses by helpless memory CD8+ T cells are restricted by the up-regulation of PD-1. J. Immunol. 182:4244-4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannoni, F., A. Shea, C. Inglis, L. N. Lee, and S. R. Sarawar. 2008. CD40 engagement on dendritic cells, but not on B or T cells, is required for long-term control of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 82:11016-11022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidotti, L. G., R. Rochford, J. Chung, M. Shapiro, R. Purcell, and F. V. Chisari. 1999. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science 284:825-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunturi, A., R. E. Berg, and J. Forman. 2004. The role of CD94/NKG2 in innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Res. 30:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Janssen, E. M., N. M. Droin, E. E. Lemmens, M. J. Pinkoski, S. J. Bensinger, B. D. Ehst, T. S. Griffith, D. R. Green, and S. P. Schoenberger. 2005. CD4+ T-cell help controls CD8+ T-cell memory via TRAIL-mediated activation-induced cell death. Nature 434:88-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasprowicz, V., J. Schulze Zur Wiesch, T. Kuntzen, B. E. Nolan, S. Longworth, A. Berical, J. Blum, C. McMahon, L. L. Reyor, N. Elias, W. W. Kwok, B. G. McGovern, G. Freeman, R. T. Chung, P. Klenerman, L. Lewis-Ximenez, B. D. Walker, T. M. Allen, A. Y. Kim, and G. M. Lauer. 2008. High level of PD-1 expression on hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells during acute HCV infection, irrespective of clinical outcome. J. Virol. 82:3154-3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khanna, K. M., R. H. Bonneau, P. R. Kinchington, and R. L. Hendricks. 2003. Herpes simplex virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells are selectively activated and retained in latently infected sensory ganglia. Immunity 18:593-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, I. J., E. Flano, D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 2002. Antibody-mediated control of persistent gamma-herpesvirus infection. J. Immunol. 168:3958-3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Kuerten, S., R. J. Asaad, S. P. Schoenberger, D. N. Angelov, P. V. Lehmann, and M. Tary-Lehmann. 2008. The TRAIL of helpless CD8+ T cells in HIV infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 24:1175-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, B. J., S. K. Reiter, M. Anderson, and S. R. Sarawar. 2002. CD28(−/−) mice show defects in cellular and humoral immunity but are able to control infection with murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 76:3049-3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, K. S., S. D. Groshong, C. D. Cool, B. K. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, and L. F. van Dyk. 2009. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection of IFNgamma unresponsive mice: a small animal model for gammaherpesvirus-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disease. Cancer Res. 69:5481-5489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine, M. H., A. M. Haberman, D. B. Sant'Angelo, L. G. Hannum, M. P. Cancro, C. A. Janeway, Jr., and M. J. Shlomchik. 2000. A B-cell receptor-specific selection step governs immature to mature B cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:2743-2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, L., E. Flano, E. J. Usherwood, S. Surman, M. A. Blackman, and D. L. Woodland. 1999. Lytic cycle T cell epitopes are expressed in two distinct phases during MHV-68 infection. J. Immunol. 163:868-874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, T., K. M. Khanna, B. N. Carriere, and R. L. Hendricks. 2001. Gamma interferon can prevent herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivation from latency in sensory neurons. J. Virol. 75:11178-11184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, T., K. M. Khanna, X. Chen, D. J. Fink, and R. L. Hendricks. 2000. CD8(+) T cells can block herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) reactivation from latency in sensory neurons. J. Exp. Med. 191:1459-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyon, A. B., and S. R. Sarawar. 2006. Differential requirement for CD28 and CD80/86 pathways of costimulation in the long-term control of murine gammaherpesvirus-68. Virology 356:50-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maier, H., M. Isogawa, G. J. Freeman, and F. V. Chisari. 2007. PD-1:PD-L1 interactions contribute to the functional suppression of virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the liver. J. Immunol. 178:2714-2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMahon, C. W., A. J. Zajac, A. M. Jamieson, L. Corral, G. E. Hammer, R. Ahmed, and D. H. Raulet. 2002. Viral and bacterial infections induce expression of multiple NK cell receptors in responding CD8(+) T cells. J. Immunol. 169:1444-1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moser, J. M., J. Gibbs, P. E. Jensen, and A. E. Lukacher. 2002. CD94-NKG2A receptors regulate antiviral CD8(+) T cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 3:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penna, A., M. Pilli, A. Zerbini, A. Orlandini, S. Mezzadri, L. Sacchelli, G. Missale, and C. Ferrari. 2007. Dysfunction and functional restoration of HCV-specific CD8 responses in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 45:588-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrovas, C., J. P. Casazza, J. M. Brenchley, D. A. Price, E. Gostick, W. C. Adams, M. L. Precopio, T. Schacker, M. Roederer, D. C. Douek, and R. A. Koup. 2006. PD-1 is a regulator of virus-specific CD8+ T cell survival in HIV infection. J. Exp. Med. 203:2281-2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radziewicz, H., C. C. Ibegbu, M. L. Fernandez, K. A. Workowski, K. Obideen, M. Wehbi, H. L. Hanson, J. P. Steinberg, D. Masopust, E. J. Wherry, J. D. Altman, B. T. Rouse, G. J. Freeman, R. Ahmed, and A. Grakoui. 2007. Liver-infiltrating lymphocytes in chronic human hepatitis C virus infection display an exhausted phenotype with high levels of PD-1 and low levels of CD127 expression. J. Virol. 81:2545-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rolink, A., F. Melchers, and J. Andersson. 1996. The SCID but not the RAG-2 gene product is required for S mu-S epsilon heavy chain class switching. Immunity 5:319-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarawar, S. R., R. D. Cardin, J. W. Brooks, M. Mehrpooya, A. M. Hamilton-Easton, X. Y. Mo, and P. C. Doherty. 1997. Gamma interferon is not essential for recovery from acute infection with murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 71:3916-3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarawar, S. R., and P. C. Doherty. 1994. Concurrent production of interleukin-2, interleukin-10, and gamma interferon in the regional lymph nodes of mice with influenza pneumonia. J. Virol. 68:3112-3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarawar, S. R., B. J. Lee, and F. Giannoni. 2004. Cytokines and costimulatory molecules in the immune response to murine gammaherpesvirus-68. Viral Immunol. 17:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarawar, S. R., B. J. Lee, S. K. Reiter, and S. P. Schoenberger. 2001. Stimulation via CD40 can substitute for CD4 T cell function in preventing reactivation of a latent herpesvirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6325-6329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneider, H., E. Valk, S. da Rocha Dias, B. Wei, and C. E. Rudd. 2005. CTLA-4 up-regulation of lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 adhesion and clustering as an alternate basis for coreceptor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:12861-12866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steed, A. L., E. S. Barton, S. A. Tibbetts, D. L. Popkin, M. L. Lutzke, R. Rochford, and H. W. Virgin IV. 2006. Gamma interferon blocks gammaherpesvirus reactivation from latency. J. Virol. 80:192-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevenson, P. G., G. T. Belz, J. D. Altman, and P. C. Doherty. 1999. Changing patterns of dominance in the CD8+ T cell response during acute and persistent murine gamma-herpesvirus infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:1059-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stevenson, P. G., G. T. Belz, J. D. Altman, and P. C. Doherty. 1998. Virus-specific CD8(+) T cell numbers are maintained during gamma-herpesvirus reactivation in CD4-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:15565-15570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson, P. G., J. S. May, X. G. Smith, S. Marques, H. Adler, U. H. Koszinowski, J. P. Simas, and S. Efstathiou. 2002. K3-mediated evasion of CD8(+) T cells aids amplification of a latent gamma-herpesvirus. Nat. Immunol. 3:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stewart, J. P., E. J. Usherwood, A. Ross, H. Dyson, and T. Nash. 1998. Lung epithelial cells are a major site of murine gammaherpesvirus persistence. J. Exp. Med. 187:1941-1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sunil-Chandra, N. P., S. Efstathiou, J. Arno, and A. A. Nash. 1992. Virological and pathological features of mice infected with murine gamma-herpesvirus 68. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2347-2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suvas, S., A. K. Azkur, and B. T. Rouse. 2006. Qa-1b and CD94-NKG2a interaction regulate cytolytic activity of herpes simplex virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells in the latently infected trigeminal ganglia. J. Immunol. 176:1703-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarakanova, V. L., F. Suarez, S. A. Tibbetts, M. A. Jacoby, K. E. Weck, J. L. Hess, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin IV. 2005. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection is associated with lymphoproliferative disease and lymphoma in BALB beta2 microglobulin-deficient mice. J. Virol. 79:14668-14679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Topham, D. J., R. C. Cardin, J. P. Christensen, J. W. Brooks, G. T. Belz, and P. C. Doherty. 2001. Perforin and Fas in murine gammaherpesvirus-specific CD8(+) T cell control and morbidity. J. Gen. Virol. 82:1971-1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trautmann, L., L. Janbazian, N. Chomont, E. A. Said, S. Gimmig, B. Bessette, M. R. Boulassel, E. Delwart, H. Sepulveda, R. S. Balderas, J. P. Routy, E. K. Haddad, and R. P. Sekaly. 2006. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nat. Med. 12:1198-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tripp, R. A., A. M. Hamilton-Easton, R. D. Cardin, P. Nguyen, F. G. Behm, D. L. Woodland, P. C. Doherty, and M. A. Blackman. 1997. Pathogenesis of an infectious mononucleosis-like disease induced by a murine gamma-herpesvirus: role for a viral superantigen? J. Exp. Med. 185:1641-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsushima, F., H. Iwai, N. Otsuki, M. Abe, S. Hirose, T. Yamazaki, H. Akiba, H. Yagita, Y. Takahashi, K. Omura, K. Okumura, and M. Azuma. 2003. Preferential contribution of B7-H1 to programmed death-1-mediated regulation of hapten-specific allergic inflammatory responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:2773-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Usherwood, E. J., and A. Nash. 1998. Lymphoproliferative disease induced by murine herpesvirus-68. Lab. Anim. Sci. 48:344-345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Usherwood, E. J., J. P. Stewart, K. Robertson, D. J. Allen, and A. A. Nash. 1996. Absence of splenic latency in murine gammaherpesvirus 68-infected B cell-deficient mice. J. Gen. Virol. 77:2819-2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vance, R. E., A. M. Jamieson, D. Cado, and D. H. Raulet. 2002. Implications of CD94 deficiency and monoallelic NKG2A expression for natural killer cell development and repertoire formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:868-873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vance, R. E., J. R. Kraft, J. D. Altman, P. E. Jensen, and D. H. Raulet. 1998. Mouse CD94/NKG2A is a natural killer cell receptor for the nonclassical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule Qa-1(b). J. Exp. Med. 188:1841-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Virgin, H. W., IV, P. Latreille, P. Wamsley, K. Hallsworth, K. E. Weck, A. J. Dal Canto, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 71:5894-5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weck, K. E., S. S. Kim, H. I. Virgin, and S. H. Speck. 1999. Macrophages are the major reservoir of latent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 in peritoneal cells. J. Virol. 73:3273-3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamazaki, T., H. Akiba, A. Koyanagi, M. Azuma, H. Yagita, and K. Okumura. 2005. Blockade of B7-H1 on macrophages suppresses CD4+ T cell proliferation by augmenting IFN-gamma-induced nitric oxide production. J. Immunol. 175:1586-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang, J. Y., Z. Zhang, X. Wang, J. L. Fu, J. Yao, Y. Jiao, L. Chen, H. Zhang, J. Wei, L. Jin, M. Shi, G. F. Gao, H. Wu, and F. S. Wang. 2007. PD-1 up-regulation is correlated with HIV-specific memory CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in typical progressors but not in long-term nonprogressors. Blood 109:4671-4678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]