Abstract

Hho1p is assumed to serve as a linker histone in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and, notably, it possesses two putative globular domains, designated HD1 (residues 41–118) and HD2 (residues 171–252), that are homologous to histone H5 from chicken erythrocytes. We have determined the three-dimensional structure of globular domain HD1 with high precision by heteronuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. The structure had a winged helix–turn–helix motif composed of an αβααββ fold and closely resembled the structure of the globular domain of histone H5. Interestingly, the second globular domain, HD2, in Hho1p was unstructured under physiological conditions. Gel mobility assay demonstrated that Hho1p preferentially binds to supercoiled DNA over linearized DNA. Furthermore, NMR analysis of the complex of a deletion mutant protein (residues 1–118) of Hho1p with a linear DNA duplex revealed that four regions within the globular domain HD1 are involved in the DNA binding. The above results suggested that Hho1p possesses properties similar to those of linker histones in higher eukaryotes in terms of the structure and binding preference towards supercoiled DNA.

INTRODUCTION

Nucleosomes are the structural units of chromatin for all eukaryotes, and consist of DNA wrapped around a histone octamer composed of core histones (H2A, H2B, H3 and H4). In addition to these core histones, linker histone H1 and its variants are known to associate with the linker region of DNA between nucleosome core particles. It is generally accepted that linker histones are involved in chromatin condensation as well as the maintenance of its higher order structure, and also serve as integral components of mechanisms that control gene expression (1–5).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, biochemical efforts to identify a linker histone have been unsuccessful, although a histone H1-like protein was found to exist many years ago. Soon after the HHO1 (histone H one) gene was identified from the entire sequence database of S.cerevisiae (6), Ushinsky et al. (7) showed that HHO1 is highly expressed and that its product, Hho1p, is localized in the nucleus. Patterton et al. (8) showed that Hho1p forms a stable ternary complex with a reconstituted core dinucleosome in vitro and that the 168 bp nucleosomal repeats are produced by micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion of H1-stripped chromatin reconstituted with Hho1p, suggesting that it possesses biochemical properties essential for a linker histone.

It should be noted that deletion of the HHO1 gene results in no obvious phenotype with respect to viability (9), growth and mating properties (8), telomeric repression and efficient sporulation (10), or chromatin structure (11). These genetic results would seem to argue against the idea that Hho1p plays a role as a linker histone. However, it was shown very recently that Hho1p inhibits DNA repair by homologous recombination, suggesting that it may act as a linker histone with a novel role (12).

One of the important criteria for linker histones is the presence of a globular domain of about 80 amino acids, which is highly conserved among all linker histones. The three-dimensional structures of the globular domains in both H5 and H1 histones have been determined by X-ray crystallography (13) and NMR (14,15). The crystal structure of the globular domain of histone H5 (GH5) was shown to be similar to the binding domain of CAP (catabolite gene activator protein). It was later shown that the GH5 domain shares a common structural motif with the DNA-binding domain of HNF-3 (hepatocyte nuclear factor-3) (16,17). This motif is composed of three helices and a three-stranded β-sheet with an αβααββ fold, and has been given the name of winged helix–turn–helix motif. The crystal structure of GH5 (13) was compared with the structure previously determined by NMR (14). However, the root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of Cα between the two structures was as high as 5 Å, indicating that the helical axes have significantly different directions in the two structures. The structure of the globular domain of histone H1 (GH1) was also determined by NMR (15). The averaged pair-wise backbone r.m.s.d. was also poor, making it difficult to compare the NMR structure of GH1 with the crystal structure of GH5 in detail. Such deviations are likely to be due in part to the inherently high flexibility of the globular domain of linker histones and/or structural differences between the domains in solution and in the crystal, as pointed out by Cerf et al. (15). It is important, therefore, to determine the structure of the globular domains GH1/GH5 of linker histones with high resolution in order to see the structural diversity among species.

It was suggested on the basis of the crystal structure (15) of the HNF-3 complex with DNA that there are two potential binding sites for linker histones, which are composed of two regions of highly conserved basic amino acids on the opposite faces of the molecules. This model explained several distinctive findings, such as, for example, the frequently reported observation that the linker histone preferentially binds to supercoiled DNA over linearized DNA (18–21).

We here examined the structure of two putative globular domains of Hho1p in solution and found that the first domain, HD1, has a winged helix–turn–helix motif, while the other domain, HD2, has a virtually flexible and disordered structure. We also carried out a gel mobility assay for DNA binding of Hho1p, which revealed that the protein indeed possesses preferential binding to supercoiled DNA over linearized DNA duplex. These results are discussed in relation to the structure and functions of Hho1p in S.cerevisiae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Hho1p and its mutant proteins

The HHO1 gene was amplified from the genomic DNA of S.cerevisiae strain FY23 [MATa ura3-52 trpΔ63 leu2Δ1] using PCR. The full-length and five truncated genes of Hho1p were cloned into the NdeI/EcoRI sites of expression vector pET21b (Novagen, Madison, WI), with which Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) was transformed to express Hho1p and deletion mutant proteins. The cells were pre-cultured in L-Broth medium overnight and then transferred to 2.0 l of M9 medium containing 1.0 g/l of 15NH4Cl, 2 g/l of [13C]glucose (for 15N- and 13C-enriched proteins) and ampicillin (100 µg/ml) at 37°C. When the cell growth reached OD600 = 0.5, protein expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. After 5 h of further incubation at 37°C, the cells were harvested and sonicated. The precipitate from the cell lysate at 60–90% relative saturation of ammonium sulfate was collected, resuspended in a buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM EDTA pH 7.2, and dialyzed against the same buffer. The dialyzed sample was applied to SP Sepharose Fast Flow column (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) and eluted with a salt gradient of 0.1–1.0 M NaCl. After dialyzing against a buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl and 2 mM EDTA (pH 6.2), the sample was applied to a DNA-cellulose column (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and eluted with a salt gradient of 0.1–1.0 M NaCl. The final purification was performed by a gel filtration chromatography using Sephadex 75 (Pharmacia) in 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl and 2 mM EDTA pH 6.2. The protein concentration was determined by UV absorbance at 275 nm using a molar absorption coefficient of 1430 l/mol/cm for tyrosine residues.

Some of the deletion mutant proteins were obtained as inclusion bodies. The cell lysate containing insoluble proteins was dissolved in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride at pH 7.2, and the denatured proteins were refolded by stepwise dilution with 10 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl and 2 mM EDTA pH 7.2. The subsequent procedures for purification of proteins were the same as those described above.

Gel mobility assay

Plasmid DNA (pET21a) was isolated using the alkaline lysis procedure and purified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The gel band of supercoiled plasmids was cut out and purified by ethanol precipitation. The linearized plasmid DNA was obtained by digesting the plasmids with restriction enzymes NdeI and EcoRI at 37°C for 4 h and purified by ethanol precipitation. The concentration of the plasmid DNA was determined by UV absorbance using the relationship 20 OD260 = 1 mg/ml of DNA.

An increasing amount of Hho1p or its deletion mutant proteins was added to a given amount of DNA in a reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-acetate and 0.1 mM EDTA pH 7.5 (to a final concentration of 13.5 µg/ml DNA in 30 µl of buffer solution). After incubation at room temperature for 1 h, the sample was subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis in the reaction buffer at 8 V/cm. The gel was stained with 200 µg/ml ethidium bromide solution.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) studies were carried out on a JA750 spectrometer (JASCO Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a temperature control unit (JASCO PTC-348). An average of four consecutive scans was recorded for the CD spectra. Temperature-induced unfolding of 25 µM samples in buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.2 was monitored by far-UV CD spectroscopy using a 2.0 mm path length quartz cell. CD spectra were recorded at temperatures from 5 to 90°C at 5°C intervals after thermal equilibration at each temperature for 10 min.

NMR measurements

Protein concentrations for NMR measurements were adjusted to ∼1 mM in 10% D2O/90% H2O containing 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.2. All NMR spectra were recorded at 25°C on a Bruker DMX500 or DMX750 spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm inverse triple resonance probehead with a three-axis gradient coil. 1H, 13C and 15N sequential resonance assignments were carried out using 2D double resonance, and 3D double and triple resonance through-bond correlation experiments (22,23): 2D 1H–15N HSQC, 2D 1H–13C CT-HSQC optimized for observation of either aliphatic or aromatic signals, 3D HNHB, 3D HNCO, 3D CBCA(CO)NH, 3D HNCACB, 3D HCABGCO and 3D HCCH-TOCSY. Stereospecific assignments of α- and β-protons and the methyl side chains of valine and leucine residues were achieved by a combination of quantitative J measurements and NOESY data. 3J couplings were measured using quantitative 2D and 3D J correlation spectroscopy (24). Interproton distance restraints were derived from multidimensional NOE spectra (22–24), which included a 3D 15N-separated NOESY-HSQC spectrum with a mixing time of 100 ms, a 3D 13C/15N-separated NOESY-HSQC spectrum with a mixing time of 100 ms, and a 4D 13C/13C-separated HMQC-NOESY-HSQC spectrum with a mixing time of 100 ms. All of the spectra were processed using NMRPipe (25) and analyzed using NMRPipp (26). 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shifts were referenced to HDO (4.77 p.p.m. at 25°C), indirectly to TSP (13C) (27) and indirectly to liquid ammonia (15N) (28), respectively.

Structure calculations

Nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE)-derived interproton distance restraints were classified into four ranges: 1.8–2.7, 1.8–3.3, 1.8–4.3 and 1.8–5.0 Å, which corresponded to strong, medium, weak and very weak NOEs, respectively. An additional 0.5 Å was added to the upper bound of distance for NOEs associated with methyl and methylene protons that were not assigned stereospecifically (29). Torsion angle restraints on φ and ψ were obtained from the statistical analysis of chemical shifts of backbone atoms (13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, 1Hα and 15N) using the program TALOS (30). The side chain χ angle restraints were derived from the 3D 15N-separated NOESY-HSQC, 4D 13C/13C-separated HMQC-NOESY-HSQC and 3D HNHB spectra. Structural calculations were performed using the hybrid distance geometry–dynamical simulated annealing method (31) in X-PLOR 3.1 (32).

RESULTS

Construction of deletion mutant proteins of Hho1p

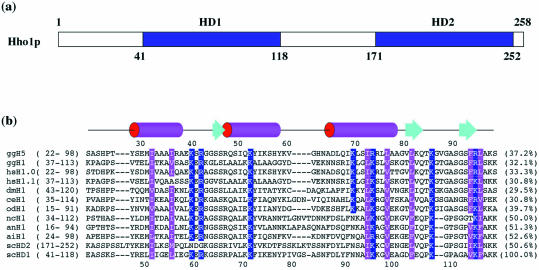

It has been suggested that Hho1p has two globular domains (2,6) based on the amino acid sequence homology between Hho1p from S.cerevisiae and the globular domain of chicken erythrocyte histone H5 (GH5). Figure 1a shows a schematic domain map of Hho1p, where two putative globular domains, HD1 and HD2, were defined on the basis of the crystal structure of GH5 (residues 22–98). Figure 1b shows the sequence alignments of the globular domains of Hho1p and other linker histones in fungi and animals, together with the secondary structure of GH5. Briefly, the first domain (HD1, residues 41–118) and second domain (HD2, residues 171–252) of Hho1p had a high sequence homology of 50.6%, and HD1 had 37.2 and 32.1% identity to GH5 (residues 22–98) and GH1 (residues 37–113), respectively. Thus, the two domains of Hho1p were considered to be more similar to GH5 than to GH1. It appears from Figure 1b that the globular domains are highly homologous among histones (ncH1, anH1, aiH1 and Hho1p) found in fungi. The sequence alignments will be discussed later in more detail.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of two putative globular domains of Hho1p: HD1 and HD2. Each domain was defined based on the sequence alignments relative to the globular domain GH5 of histone H5. (b) Structure-based sequence alignments of the globular domain regions of linker histones in protists, animals and fungi. Histones are labeled simply with abbreviations: gg, Gallus gallus (chicken); hs, Homo sapiens; dm, Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly); ce, Caenorhabditis elegans (nematoda); od, Oikopleura dioica (tonicata); nc, Neurospora crassa (fungus); an, Aspergillus nidulans (fungus); ai, Ascobolus immersus (fungus); sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The secondary structure of GH5 of histone H5 (13) is schematically shown at the top of the figure. Numbers in parentheses represent the range of amino acid residues of the domain within each histone. Key residues for the formation of a hydrophobic core and highly conserved basic residues are highlighted in magenta and blue, respectively. Percentiles shown in the last column indicate the extent of sequence identity to scHD1.

To examine the structure and DNA binding properties of Hho1p, the full-length Hho1p and five truncated mutant proteins were constructed based on the sequence alignments shown in Figure 1b. They included HD1 (residues 41–118), HD2 (residues 166–252), HD1N (residues 1–118), HD1L (residues 41–171) and D1D2 (residues 41–252). The truncated protein HD1N was composed of the HD1 domain and the N-terminal tail, protein HD1L was composed of HD1 and the linker region between HD1 and HD2, and protein D1D2 was composed of two globular domains. First, we tried to examine the three-dimensional structures of two putative domains of Hho1p in solution.

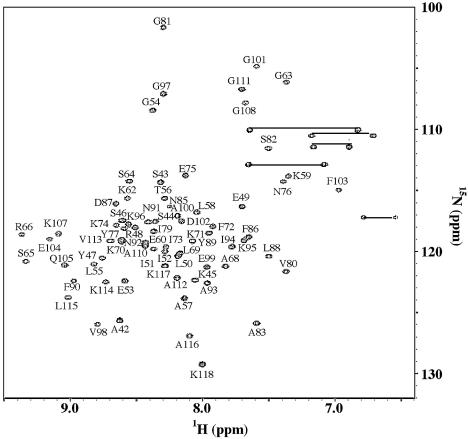

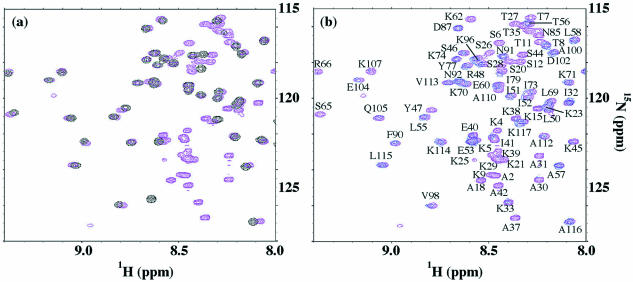

Spectral assignments of HD1

The 1H–15N HSQC spectrum of uniformly 15N-labeled HD1 protein recorded at 25°C showed well dispersed, evenly intense cross-peaks, indicating the presence of a well-defined structure (Fig. 2). The backbone resonances of 1H, 15N, 13Cα and 13Cβ were sequentially assigned based on the analysis of CBCA(CO)NH and HNCACB spectra. The assignments were confirmed and extended to backbone carbonyl 13CO and side chain 13C cross-peaks by the correlation observed in the following triple resonance experiments: 15N-separated HNCO and HCCH-TOCSY. Side chain 1H and 13C cross-peaks in an aromatic region were assigned from cross-peak patterns observed in 1H–13C CT-HSQC and CT-HSQC-relay spectra that were optimized for the aromatic region. The aromatic Hδ and Cδ signals were then correlated to the sequentially assigned backbone signals through cross-peaks in 3D 15N-separated NOESY-HSQC, 13C/15N-separated NOESY-HSQC and 4D 13C/13C-separated NOESY spectra.

Figure 2.

The two-dimensional 1H–15N HSQC spectrum of HD1 and assignments of the backbone amides. Amide peaks of Arg61 and Ser84 were not observed in the spectrum.

Stereospecific assignments of glycine α-protons were determined from 3JHNHα coupling constants, intraresidue NOEs between glycine α-protons and the HN proton, and sequential NOEs between glycine α-protons (i) and the HN proton (i + 1). The β-protons were stereospecifically assigned using J coupling constants obtained from an HNHB experiment. In some cases, the local secondary structures inferred from short-range NOEs were used to assist the stereospecific assignments. All valine γ-methyl groups were stereospecifically assigned based on 3JNCγ, 3JNHβ and 3JHNHα coupling constants, and also on NOEs between valine α-proton and β- or γ-protons. Leucine δ-methyl groups were stereospecifically assigned by 3D NOESY and 4D NOESY spectra.

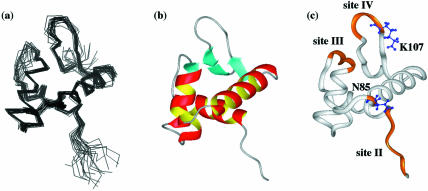

Tertiary structure of HD1

The structure calculations were performed using 1328 interproton distance restraints and 153 dihedral angle restraints as shown in Table 1. A final set of 20 lowest energy structures was selected from 100 calculations. There were no violations larger than 0.5 Å and 5° for the NOE and dihedral angles, respectively. The average coordinates of the ensembles of the final 20 structures were subjected to 500 cycles of Powell restrained energy minimization to improve the stereochemistry and non-bonded contacts. The structural statistics for the final 20 lowest energy structures accepted and the restrained minimized average structures are summarized in Table 1, together with the NMR-derived constraints used for the calculations. The superimposed backbone traces of 20 structures were well aligned, as shown in Figure 3a, where residues 41–46 at the N-terminus, residues 59–63 and 105–111 in the loops and residues 117–118 at the C-terminus are somewhat scattered, probably because they are flexible in nature. The r.m.s.d. for backbone heavy atoms in residues (47–116) was 0.50 Å and for all heavy atoms was 1.02 Å. The statistics listed in Table 1 did not change significantly when the 76 lowest energy structures out of 100 calculated structures were used for statistical calculations.

Table 1. Statistics for NMR Structures of HD1.

| Total constraints used | 1481 |

| Total distance constraints | 1328 |

| Intraresidue | 610 |

| Sequential (|i – j| = 1 ) | 259 |

| Short-range (1 < |i – j| < 5 ) | 282 |

| Long-range (|i – j| ≥ 5) | 177 |

| Total dihedral angle constraints | 153 |

| φ | 51 |

| ψ | 51 |

| χ1 | 51 |

| χ2 | 51 |

| Potential energies (kcal/mol) | |

| ENOE | 91.6 ± 8.6 |

| Ecdih | 1.87 ± 0.50 |

| Erepel | 16.2 ± 2.0 |

| R.m.s.d. from idealized geometry | |

| Bond (Å) | 0.00344 ± 0.00001 |

| Angles (°) | 0.639 ± 0.0149 |

| Impropers (°) | 0.53 ± 0.022 |

| R.m.s.d. from mean structure (47–116 amino acids) | |

| Backbone atoms | 0.50 ± 0.12 |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 1.02 ± 0.16 |

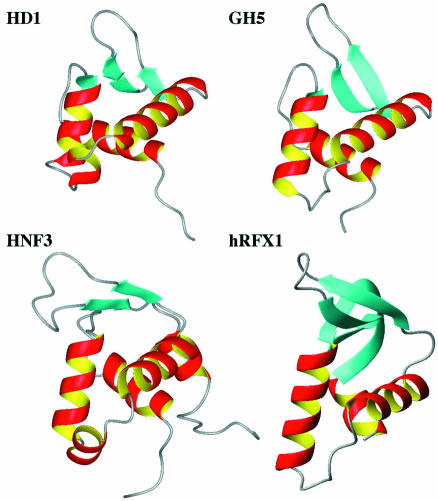

Figure 3.

(a) View of the superimposed backbone heavy atom (N, Cα and C′) coordinates of the 20 lowest energy NMR structures of HD1. For alignment of the structures, backbone atom coordinates of residues 47–116 were used. (b) Ribbon diagram of the restrained minimized average NMR structure of HD1. (c) Residues whose amide correlation cross-peaks were perturbed by interaction of HD1N with DNA are highlighted in orange in a ribbon model of HD1, and the side chains of two residues involved in DNA binding are displayed in blue.

Figure 3b shows a ribbon diagram of the averaged structure of HD1, revealing that the globular domain HD1 folds into the winged helix–turn–helix motif with an αβααββ fold. This motif consisted of three α-helices: α1 (residues 47–58), α2 (residues 66–74) and α3 (residues 85–99), with an additional short helix (residues 79–82) in the long loop between α2 and α3. The wing of the motif was composed of a short three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet: β1 (residues 64–65), β2 (residues 103–104) and β3 (residues 112–115). The hairpin loop of the antiparallel β-sheet formed a single highly twisted wing in the motif. As will be discussed later, the architecture of HD1 closely resembled the crystal structure of GH5 (13). The solution structure of HD1 was deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID code 1UHM).

Structure and stability of globular domain HD2

It was reasonable to assume that the structure of HD2 (residues 166–252) would be similar to that of HD1 (residues 41–118), since these two domains were highly homologous. Interestingly, these two domains behaved very differently. For example, HD1 was highly soluble, whereas HD2 was expressed as an inclusion body, which was refolded from 6 M guanidine hydrochloride solution under high ionic strength (0.5 M NaCl). The refolded HD2 became soluble but unstable at lower ionic strength (<0.1 M NaCl) and tended to aggregate as judged from the 1H–15N HSQC spectra of HD2 (data not shown). Furthermore, the 1H–15N HSQC spectrum of D1D2 showed that all the cross-peaks from domain HD1 were identical in position to those of sole HD1, whereas those from domain HD2 were crowded in the narrow range of 8.0– 8.6 p.p.m. in the amide proton chemical shift (data not shown). This observation strongly indicated that the winged helix motif of HD1 is well conserved in D1D2, whereas the HD2 domain is most probably unstructured.

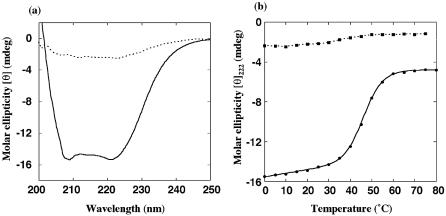

Figure 4 shows the CD spectra of truncated proteins HD1 and HD2 at 10°C and their thermal denaturation curves. As can be seen in Figure 4a, HD1 displayed a typical CD spectrum for the α/β mixed form of proteins, whereas HD2 gave a much smaller magnitude of molar ellipticity at 222 nm than HD1, suggesting that HD2 was mostly disordered even at the low temperature of 10°C. In accordance with the above result, the denaturation curves in Figure 4b demonstrated the absence of a clear helix–coil transition for HD2. Thus, it was strongly suggested from NMR and CD experiments that the putative globular domain HD2 is virtually unstructured.

Figure 4.

(a) CD spectra of truncated mutant proteins HD1 and HD2 at 10°C in 10 mM sodium phosphate and 100 mM NaCl pH 7.2. (b) Thermal denaturation of HD1 and HD2 monitored by CD spectroscopy at 222 nm. Solid and dotted lines represent HD1 and HD2, respectively.

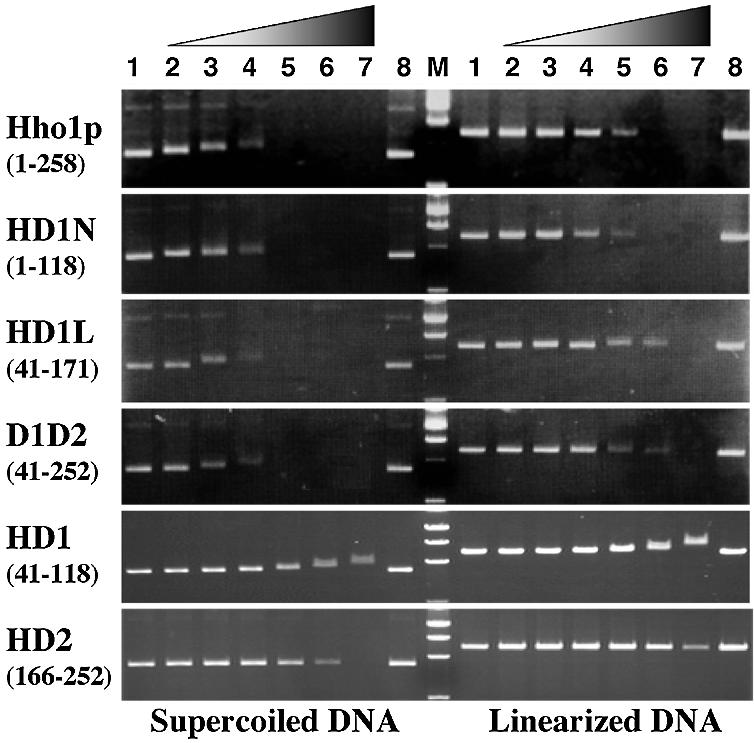

Characterization of the DNA binding ability of Hho1p

It is well known that histones H1 and H5 show preferential binding towards supercoiled DNA (18–21). To investigate the mechanism underlying this preferential binding, an agarose gel mobility assay was carried out for Hho1p and its truncated proteins using two different forms of plasmid pET21a: a supercoiled and a linearized form (Figure 5). In the case of the full-length Hho1p (top left panel), the mobility of supercoiled DNA was gradually retarded with increasing protein concentrations (lanes 2–4), and its complex band disappeared between P/D ratios of 0.5 and 1.0. In contrast to supercoiled DNA, the mobility of linearized DNA (top right panel) remained unchanged at lower P/D values (lanes 2–5) and the gel band disappeared at higher P/D values of 1.0–2.0 (lanes 5–7). Finally, at the highest P/D of 4.0, it was immobile at origin due to aggregation of DNA molecules. Thus, an approximately 2- to 4-fold higher P/D value was required for binding to linearized DNA, indicating that Hho1p shows preferential binding to supercoiled over linearized DNA.

Figure 5.

Gel mobility shift assay for the binding affinity of Hho1p and its deletion mutant proteins for two forms of plasmid DNA. Solutions of 13.5 µg/ml of DNA mixed with variable amounts of proteins were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and stained by ethidium bromide. Left and right panels are the binding assay for supercoiled and linearized DNA, respectively. Protein/DNA mass ratios in each of panels are as follows: lanes 1 and 8, 0; lane 2, 0.125; lane 3, 0.25; lane 4, 0.5; lane 5, 1.0; lane 6, 2.0; lane 7, 4.0. The letter M represents the DNA size makers.

The results of the gel mobility assays for the proteins HD1N (residues 1–118), HD1L (residues 41–171) and D1D2 (residues 41–252) were similar, with each of the three showing nearly the same binding affinity for DNA as the full-length Hho1p, as clearly shown in the second, third and fourth panels, respectively. The observation that HD1L and D1D2 have the same binding affinity for DNA suggested that HD2 is less important for DNA binding. On the other hand, the gel mobility assay for HD1 (residues 41–118) and HD2 (residues 166–252) showed that each of the globular domains alone has weak affinity and weak binding preference for supercoiled DNA, as can be seen in the last two panels. However, a detailed comparison revealed subtle but substantial differences in DNA binding mode between HD1 and HD2, i.e. HD1 showed a gradual mobility shift for supercoiled DNA (lanes 4–7 on the left in the fifth panel) and for linearized DNA (lanes 5–7 on the right in the same panel). On the other hand, HD2 did not cause such mobility shifts at any P/D values, but it caused supercoiled and linearized DNA molecules to aggregate and immobilize at the highest P/D of 4.0 (last panel), indicating that the DNA binding of HD2 would be very weak and highly non-specific.

Interaction of the globular domain in Hho1p with DNA

Histone H1 and its variants have a flexible N-terminal tail composed of about 20 residues, while Hho1p has a basic rich N-terminal tail that is approximately twice as long as that of other linker histones. Therefore, it is of interest to ask whether the N-terminal tail of Hho1p has a specific structure or a particular role in recognizing DNA. To examine these issues, we carried out several NMR experiments for the truncated protein HD1N (residues 1–118) in the absence and presence of DNA. We used a DNA fragment of 264 bp with a mixed sequence amplified by PCR, because the 1H–15N HSQC spectra of protein–DNA complexes indicated that the HD1N protein bound the 264 bp DNA but not short DNA duplexes, such as a chemically synthesized 14mer DNA.

Figure 6a shows an expanded region of the 1H–15N HSQC spectrum of HD1N (colored in magenta) and overlaid with the spectrum of truncated protein HD1 (residues 41–118) alone (colored in black). The following can be pointed out on the basis of the spectral analysis of the DNA-free HD1N and comparison with the spectrum of HD1. First, all the cross-peaks responsible for the HD1 domain in the HD1N protein had chemical shifts almost identical to those of sole HD1, indicating that the winged helix structural motif of HD1 is completely preserved for the globular domain in HD1N. Secondly, the chemical shift deviations of 13Cα and 13Cβ atoms from their random coil values for the N-terminal tail (residues 1–40) in HD1N were small, <1 p.p.m. in magnitude (data not shown), indicating that this tail is entirely flexible and unstructured in nature.

Figure 6.

(a) Overlay of expanded regions of the 1H–15N HSQC spectra of HD1N (magenta) and HD1 (black) showing that the HD1 domain preserves the higher ordered structure, while the N-terminal tail is disordered and flexible. (b) Overlaid 1H–15N HSQC spectra of HD1N in the absence (magenta) and presence (blue) of the 264 bp DNA. The protein:DNA ratio in the complex was about 1:1 in weight (corresponding to an approximately 13:1 molar ratio). All peak assignments are labeled for the DNA-free HD1N.

Figure 6b compares the spectra of HD1N in the absence (magenta) and the presence (blue) of the 264 bp DNA. Spectral perturbations due to the DNA binding of HD1N resulted in the loss of spectral intensity without chemical shift changes. Such loss of spectral intensity would be accounted for by spectral broadening due to non-specific and weak binding to linear DNA with very high molecular weight. Peaks on the middle left side in the spectra of Figure 6b, for example, Ser65, Arg66 and Lys107, disappeared when HD1N formed the complex with DNA, while the cross-peaks Glu104 and Gln105 were only slightly perturbed. Detailed examination of the individual peaks in Figure 6b revealed that the peaks that were lost or remarkably reduced in intensity could be ascribed to residues about four regions or sites along the chain of HD1N, i.e. site I (M1–A31), site II (A37–Y47), site III (K62–R66) and site IV (K107–A110), and residue Asn85. Site I is apparently in the N-terminal tail of HD1, site II is in a flexible region adjacent to the N-terminus of helix α1, site III is in the turn region including the β1-strand between helices α1 and α2, site IV is in the β-hairpin loop between strands β2 and β3, and Asn85 is located at the end of the N-terminus of helix α3. In Figure 3c, the residues perturbed by complex formation are mapped and highlighted in orange on a ribbon model of HD1. It seems likely that sites III and IV are in close enough proximity to form one binding surface, while site II and Asn85 are close enough to form another binding surface.

Several of the conserved basic residues (Lys59, Lys61, Lys95, Lys107 and Lys114) in the sequence alignments shown in Figure 1 were thought to be involved in the DNA binding of linker histones, but this was found to be true of only one, Lys107 in site IV (see K107 in Fig. 3c). The relatively small spectral perturbations observed for the other residues was probably due to the inherently weak interaction of HD1N and linear DNA.

DISCUSSION

Structural features of the globular domains of Hho1p

The linker histones present in all multicellular eukaryotes are the most divergent group of histones, with numerous cell type- and stage-specific variants. A common feature of this protein family is a tripartite structure in which a globular domain is flanked by two less structured N- and C-terminal tails. The globular domain is also characterized by high sequence homology among the family of linker histones.

The structure of the globular domain HD1 of Hho1p determined here is compared with representative proteins having the winged helix–turn–helix motif in Figure 7. These include the globular domain of histone H5, GH5 (13), the DNA recognition domain of hepatocyte nuclear factor 3, HNF-3/fork head (16,17), and the DNA-binding domain of regulatory factor X, hRFX1 (33). The architecture of HD1 showed a particularly close resemblance to the crystal structure of GH5 (13), but less so to the NMR structure of the globular domain of histone H1 (GH1) (15). Close examination of the tertiary structure of HD1 reveals several noticeable differences from that of GH5. There are prominent differences between the sequences of HD1 and GH5 in the turn between α2 and α3, which is longer by three residues in HD1, and in the β-hairpin loop between β2 and β3, which is shorter by two residues in HD1. The longer turn is well adapted into the winged helix–turn–helix motif by the formation of a short α-helix (residues 79–82) between helices α2 and α3, as observed for HNF-3/fork head in Figure 7 (17). The long hairpin loop between the β2 and β3 strands displayed a kink with a positive ψ angle (5°) at Pro109, and the β2 strand becomes shorter by two residues because of the presence of Pro106 at the fourth position of this β-strand.

Figure 7.

Structural comparison of HD1 with other representative winged helix–turn–helix motif proteins. The solution structure of HD1 determined in this study is shown, and compared with GH5, the globular domain of linker histone H5 (13); HNF-3/fork head, the DNA recognition domain of hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 (17); and hRFX1, the DNA-binding domain of regulatory factor X (18).

As shown in Figure 1b, the sequence alignments of linker histones from various species provide important information on several basic and hydrophobic residues (highlighted in blue and magenta, respectively). Here, residues are numbered according to histone H5 from chicken erythrocytes. The highly conserved hydrophobic residues Leu76, Leu81, Phe93 and Leu95 in GH5 are known to form a hydrophobic cluster that anchors the base of the β-hairpin wing to the core of the three-helix bundle (13). The structural comparison of HD1 with GH5 revealed that such a hydrophobic cluster is also formed by Ile51, Leu55, Ile94, Val98, Phe103, Val113 and Leu115 in HD1, which are respectively located at the positions corresponding to the conserved or conservatively substituted hydrophobic residues in GH5.

It is very rare for linker histones to have two globular domains as in the case of Hho1p (2,6). It would thus be of interest to determine whether two globular domains are essential for the DNA binding of Hho1p. However, it was not possible to determine the structure of HD2 because it was virtually unfolded under physiological conditions in spite of the high sequence identity (50%) and similarity (70%) to HD1 (Fig. 1b). The lack of stability for HD2 leads us to propose that HD1 plays a more important role in positioning for DNA binding, while HD2 is a part of the C-terminal tail supplemental for DNA binding.

DNA binding and biological roles of Hho1p

It was suggested from the 1H–15N HSQC spectrum of the HD1N–DNA complex that three sites, II, III and IV, and the vicinity of Asn85 are involved in the DNA binding of globular domain HD1, as depicted in Figure 3c. Lys85 at site IV, which corresponds to Lys107 in Hho1p, was protected from chemical modification by interaction of histone H5 with nucleosomes (34), replacement of Lys85 with glutamine or glutamic acid abolished correct nucleosome binding (35), and similar results were obtained by its substitution with alanine (36). These results are consistent with our observations that the β-hairpin loop (site IV) including Lys107 is involved in the complex formation with DNA. A chemical cross-linking experiment of histone H5 with DNA in nucleosomes revealed that His25 and His62 have close contacts to DNA (37). Although these two histidine residues are not conserved in Hho1p (Fig. 1b), their corresponding positions in Hho1p are in site II and the site very close to Asn85, respectively. Thus, it can be stated that the DNA-binding sites on HD1 mentioned above are essentially but not entirely consistent with existing biochemical evidence for the GH5 domain of histone H5 (34–37), as discussed also in the Results section. It is therefore suggested that there are two binding surfaces on the opposite sides of the globular domain of Hho1p, as depicted in Figure 3c.

Binding specificity of H5 and H1 histones towards supercoiled DNA has been reported by several investigators (18–21), implying that they possess binding selectivity for the crossovers of DNA duplex formed by the superhelical turns. As was demonstrated in Figure 5, Hho1p exhibited preferential binding towards supercoiled over linearized DNA, suggesting that Hho1p interacts with DNA in ways similar to histone H1. Despite the high similarity in structural and biochemical properties between the globular domains of Hho1p and histone H5, the two domains exhibited significant differences in binding strength and binding preference. The relatively weak interaction with DNA of Hho1p may be relevant to the functional roles of linker histones in S.cerevisiae. In fact, Linder and Thoma (38) and Miloshev et al. (39) demonstrated that the expression of the sea urchin histone H1 in S.cerevisiae causes dramatic changes in intracellular morphology and leads to cell death, i.e. exogenous histone H1 was very toxic for yeast. Furthermore, Freidkin and Katcoff (40) found an unexpectedly low stoichiometry of Hho1p per nucleosome (approximately 1/37) and thereby pointed out that Hho1p plays a role similar to linker histones, but at restricted locations such as rRNA gene loci in the chromatin. Recently, Downs et al. (12) suggested that Hho1p inhibits DNA repair by homologous recombination and that the deletion of Hho1p shortens the life span of yeast. These results suggest that histone Hho1p in S.cerevisiae may interact with the chromatin structure in similar ways, but functions differently from the canonical H1 of higher eukaryotes.

PDB no. 1UHM

REFERENCES

- 1.Horn P.J. and Peterson,C.L. (2002) Chromatin higher order folding: wrapping up transcription. Science, 297, 1824–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasinsky H.E., Lewis,J.D., Dacks,J.B. and Ausio,J. (2001) Origin of H1 linker histones. FASEB J., 15, 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausio J. (2000) Are linker histones (histone H1) dispensable for survival? Bioessays, 22, 873–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vignali M. and Workman J.L. (1998) Location and function of linker histones. Nature Struct. Biol., 5, 1025–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramakrishnan V. (1997) Histone H1 and chromatin higher-order structure. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Express., 7, 215–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landsman D. (1996) Histone H1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a double mystery solved? Trends Biochem. Sci., 21, 287–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ushinsky S.C., Bussey,H., Ahmed,A.A., Wang,Y., Friesen,J., Williams,B.A. and Stoms,R.K. (1997) Histone H1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast, 13, 151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterton H.G., Landel,C.C., Landsman,D., Peterson,C.L. and Simpson,R.T. (1998) The biochemical and phenotypic characterization of Hho1p, the putative linker histone H1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 7268–7276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellauer K., Sirard,E. and Turcotte,B. (2001) Decreased expression of specific genes in yeast cells lacking histone H1. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 13587–13592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escher D. and Schaffner,W. (1997) Gene activation at a distance and telomeric silencing are not affected by yeast histone H1. Mol. Gen. Genet., 256, 456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puig S., Matallana,E. and Perez-Ortin,J.E. (1999) Stochastic nucleosome positioning in a yeast chromatin region is not dependent on histone H1. Curr. Microbiol., 39, 168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downs J.A., Kosmidou,E., Morgan,A. and Jackson,S.P. (2003) Suppression of homologous recombination by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae linker histone. Mol. Cell, 11, 1685–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramakrishnan V., Finch,J.T., Graziano,V., Lee,P.L. and Sweet,R.M. (1993) Crystal structure of globular domain of linker histone H5 and its implications for nucleosome binding. Nature, 362, 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clore G.M., Gronenborn,A.M., Nilges,M., Sukumeran,D.K. and Zanbocke,J. (1987) The polypeptide fold of the globular domain of histone H5 in solution. A study using nuclear magnetic resonance, distance geometry and restrained molecular dynamics. EMBO J., 6, 1833–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerf C., Lippens,G., Ramakrishnan,V., Muyldermans,S., Segers,A., Wyns,L., Wodak,S.J. and Hallenga,K. (1994) Homo- and heteronuclear two-dimensional NMR studies of the globular domain of histone H1: full assignment, tertiary structure and comparison with the globular domain of histone H5. Biochemistry, 33, 11079–11086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark K.L., Halay,E.D., Lai,E. and Stephan,K.B. (1993) Co-crystal structure of the HNF-3/fork head DNA-recognition motif resembles histone H5. Nature, 364, 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin C., Marsden,I., Chen,X. and Liao,X. (1999) Dynamic DNA contacts observed in the NMR structure of winged helix protein–DNA complex. J. Mol. Biol., 289, 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singer D.S. and Singer,M.F. (1976) Characterization of complex superhelical and relaxed closed circular DNA with H1 and phosphorylated H1 histones. Nucleic Acids Res., 3, 2531–2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krylov D., Leuba,S., van Holde,K. and Zlatanova,J. (1993) Histones H1 and H5 interact preferentially with crossovers of double-helical DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 5053–5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivanchenko M., Zlatanova,J. and van Holde,K. (1997) Histone H1 preferentially binds to superhelical DNA molecules of higher compaction. Biophys. J., 72, 1388–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivanchenko M., Zlatanova,J., Varga-Weisz,P., Hassan,A. and van Holde,K. (1996) Linker histones affect patterns of digestion of supercoiled plasmids by single-strand-specific nucleases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 6970–6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bax A. and Grzesiek,S. (1993) Methodological advances in protein NMR. Acc. Chem. Res., 26, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clore G.M. and Gronenborn,A.M. (1991) Structure of large proteins in solution: three- and four-dimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Science, 252, 1390–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clore G.M. and Gronenborn,A.M. (1998) Determining the structures of large proteins and protein complexes by NMR. Trends Biotechnol., 16, 22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaglio F., Grzesiek,S., Vuister,G.W., Zhu,G., Pfeifer,J. and Bax,A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR, 6, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrett D.S., Powers,R., Gronenborn,A.M. and Clore,G.M. (1991) A common sense approach to peak picking in two-, three- and four-dimensional spectra using automatic computer analysis of contour diagrams. J. Magn. Reson., 95, 214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bax A. and Subramanian,V. (1986) Sensitivity-enhanced two-dimensional heteronuclear shift correlation NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson., 67, 565–569. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Live D.H., Davis,D.G., Agosta,W.C. and Cowburn,D. (1984) Observation of 1000-fold enhancement of nitrogen-15 NMR via proton-detected multiquantum coherences: studies of large peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 106, 1934–1941. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wüthrich K., Billetter,M. and Braun,W. (1983) Pseudo-structures for 20 common amino acids for use in studies of protein conformations by measurements of intramolecular proton–proton distance constraints with nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Mol. Biol., 169, 949–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornilescu G., Delaglio,F. and Bax,A. (1999) Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR, 13, 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilges M., Clore,G.M. and Gronenborn,A.M. (1988) Determination of three-dimensional structures of proteins from interproton distance data by dynamical simulated annealing from random array of atoms. FEBS Lett., 229, 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brünger A.T. (1993) X-PLOR Manual Version 3.1. Yale University, New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gajiwala K.S., Chen,H., Cornille,F., Roques,B.P., Reith,W., Mach,B. and Burley,S.K. (2000) Structure of the winged-helix protein hRFX1 reveals a new mode of DNA binding. Nature, 403, 916–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas J.O. and Willson,C.M. (1986) Selective radiolabelling and identification of a strong nucleosome binding site on the globular domain of histone H5. EMBO J., 5, 3531–3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buckle R.S., Maman,J.D. and Allan,J. (1992) Site-directed mutagenesis studies on the binding of the globular domain of linker histone H5 to the nucleosome. J. Mol. Biol., 223, 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goytisolo E.A., Gerchman,S.E., Yu,X., Rees,C., Graziano,V., Ramakrishnan,V. and Thomas,J.O. (1996) Identification of the two DNA-binding sites on the globular domain of histone H5. EMBO J., 15, 3421–3429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mirzabekov A.D., Pruss,D.V. and Ebralidse,K.K. (1989) Chromatin superstructure-dependent crosslinking with DNA of the histone H5 residues Thr1, His25 and His62. J. Mol. Biol., 211, 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linder C. and Thoma,F. (1994) Histone H1 expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae binds to chromatin and affects survival, growth, transcription and plasmid stability but does not change nucleosomal spacing. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 2822–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miloshev G., Venkov,P., van Holde,K. and Zlatanova,J. (1994) Low levels of exogenous histone H1 in yeast cause cell death. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 11567–11570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freidkin I. and Katcoff,D.J. (2001) Specific distribution of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae linker histone homolog HHO1p in the chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 4034–4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]