Abstract

The use of cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) as drug carriers for targeted therapy is limited by the unrestricted cellular translocation of CPPs. The preferential induction of tumor cell death by penetratin (Antp)-directed peptides (PNC27 and PNC28), however, suggests that the CPP Antp may contribute to the preferential cytotoxicity of these peptides. Using PNC27 as a molecular model, we constructed three novel peptides (PT, PR9, and PD3) by replacing the leader peptide Antp with one of three distinct CPPs (TAT, R9, or DPV3), respectively. The IC50 values of PNC27 in tumor cells were 2–3 times lower than in normal cells. However, all three engineered peptides demonstrated similar cytotoxic effects in tumor and normal cells. Another three chimeric peptides containing the leader peptide Antp with different mitochondria-disrupting peptides (KLA-Antp (KGA), B27-Antp (BA27), and B28-Antp (BA28)), preferentially induced apoptosis in tumor cells. The IC50 values of these peptides (3–10 μm) were 3–6 times lower in tumor cells than in normal cells. In contrast, TAT-directed peptides (TAT-KLA (TK), TAT-B27 (TB27), and TAT-B28 (TB28)), were cytotoxic to both tumor and normal cells. These data demonstrate that the leader peptide Antp contributes to the preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides. Furthermore, Antp-directed peptides bind chondroitin sulfate (CS), and the removal of endogenous CS reduces the cytotoxic effects of Antp-directed peptides in tumor cells. The overexpression of CS in tumor cells is positively correlated to the cell entry and cytotoxicity of Antp- directed peptides. These results suggest that CS overexpression in tumor cells is an important molecular portal that mediates the preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides.

Keywords: Anticancer Drug, Cancer Therapy, Fusion Protein, Glycosaminoglycan, Peptides, Cell-penetrating Peptide, Drug Delivery System, Cancer-targeted Therapy

Introduction

Anticancer therapy aims to kill malignant cells while minimizing the adverse effects on normal cells. The targeted delivery of toxic moieties to tumor cells by attaching them to antibodies, antibody fragments, or ligands that recognize overexpressed cell surface markers is a promising approach (1, 2). However, the use of biomacromolecules, such as peptide-, protein-, and nucleic acid-based drugs, as targeted therapeutic agents is made difficult by their limited ability to permeate the plasma membrane (3). Because of their ability to cross the plasma membranes of mammalian cells, cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs)2 are potential carriers of bioactive biomacromolecules (3, 4). However, the penetration of most CPPs into tumor cells and normal cells has been observed to occur at a similar level. Therefore, the use of CPPs for targeted therapy is limited by their unrestricted cellular translocation (3).

One strategy for improving the therapeutic index of CPPs in cancer targeting therapy is to add selectivity to the CPPs by attaching them to molecules that specifically bind to cell surface markers (5–7). Another approach is to use CPPs to deliver cargos that are specifically toxic to cancer cells. The CPP-directed translocation of p53-derived peptides is a typical example of this strategy. p53 is a sequence-specific transcription factor that binds DNA and transactivates cellular proteins involved in growth and cell cycle regulation (8). In the absence of an activator, the sequence-specific DNA-binding activity of p53 is negatively regulated by its C-terminal sequence (amino acids 363–393). If the exogenous C-terminal p53 peptide (amino acids 361–382, p53p) is present; however, it can bind to p53 and restore its DNA binding function (9). After delivery into cells by the CPP penetratin (Antp), the p53p peptide induces p53-dependent apoptosis in premalignant and malignant cell lines. The p53p peptide is relatively nontoxic to both p53-null cancer cells and normal cells (10–13).

Using the same concept as p53p delivery, two fusion peptides, PNC27 and PNC28 containing the N-terminal domain of p53 (amino acids 12–26) and Antp were designed by Pincus and co-workers (14). Because the N-terminal domain of p53 can disassociate p53 from the p53-MDM2 complex, PNC27 and PNC28 were expected to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in tumor cells in a p53-dependent manner. As expected, these peptides were preferentially toxic to malignant cells and relatively nontoxic to both untransformed and normal cells. However, both peptides killed cancer cells by inducing p53-independent necrosis, rather than via p53-dependent apoptosis (14–17). This result suggested that the selectivity of these peptides is not determined by the p53-derived domain they contain. Because the leader peptide Antp in PNC28 changed the predicted mechanism of the fused p53-derived peptide (18), an interesting question is whether the leader peptide Antp contributed to the observed preferential cytotoxicity of PNC27 and PNC28 in tumor cells. If this was the case, identification of the molecular portal that mediates the preferential cytotoxicity of the Antp-directed peptide will be important.

Because of their cationic nature, it was originally thought that the importation of CPPs including Antp occurs via direct permeation through the negatively charged plasma membrane and that CPPs should, consequently, possess low cell specificity (19). More recently, the finding that either enzymatic or genetic removal of surface glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in vivo results in the reduction or abolition of CPP uptake indicates that the cell surface GAGs are important molecular portals of CPPs (20–23). Interestingly, Jain et al. (24) found that coinjection with Antp significantly improved the tumor retention of a sc(Fv)2 antibody. Mueller et al. (25) also found that Antp is internalized to a greater extent by human cervix carcinoma cells (HeLa) than by normal cells, such as human embryonic kidney (HEK293), African green monkey kidney (COS-7), and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. Because aberrant expression of GAGs is common on tumor cells (26, 27), it is possible that the initial binding of Antp to surface GAGs overexpressed on tumor cells contributes to the preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides.

In the present study, we used PNC27 as a molecular model to investigate the contribution of the leader peptide Antp to the preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides. First, we constructed three fusion peptides, PR9, PT, and PD3, by replacing the leader peptide Antp in PNC27 with the CPPs, R9, TAT (4), and DPV3 (28), respectively. We then used the leader peptide Antp and three mitochondria-disrupting peptides, KLA (29), truncated BMAP27 (B27), and BMAP28 (B28) (30, 31), to construct three novel chimeric peptides, KLA-Antp (KGA), B27-Antp (BA27), and B28-Antp (BA28), respectively. After comparing the cytotoxicity and specificity of these peptides, we investigated the role of several major tumor cell surface GAGs in the cellular translocation and cytotoxicity of the Antp-directed peptides. Our results demonstrate that all of the Antp-directed peptides we tested are preferentially cytotoxic to tumor cells. Our results also demonstrate that the initial binding of Antp to the surface chondroitin sulfate (CS) GAGs, which are overexpressed on tumor cells, contributes to the preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Peptide Design and Synthesis

To investigate whether the leader peptide Antp contributes to the preferential cytotoxicity of PNC27, we constructed three novel peptides, PR9, PT, and PD3, by replacing the leader sequence of PNC27 with three nonspecific CPPs, R9, TAT, and DPV3, respectively. KLA, B27, and B28 are able to induce considerable mitochondrial swelling at low micromolar concentrations (30–32). KLA has been widely used as a cytotoxic domain to construct hybrid molecules that target different types of tumor cells (29, 32). Molecules containing KLA have also been shown to exhibit leader sequence-dependent cytotoxicity in target cells. These facts suggest that the cell specificity of hybrid molecules containing a mitochondria-disrupting peptide depends largely on its leader sequence. Therefore, we used the leader peptide Antp and one of three mitochondria-disrupting peptides, KLA, B27, and B28, to construct three novel chimeric peptides, KGA, BA27, and BA28, respectively. Three control peptides, TAT-KLA (TK), TAT-BA27 (TB27), and TAT-B28 (TB28), were constructed by attaching KLA, B27, and B28, respectively, to the C terminus of the nonspecific CPP TAT. All peptides (Table 1, >95% purity) were synthesized by fluoren-9-ylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry (GenScript Corporation, Nanjing, China).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of peptides used in this work

| Peptide | Sequence | Length | Molecular mass |

|---|---|---|---|

| aaa | Da | ||

| PNC27 | PPLSQETFSDLWKLLKKWKMRRNQFWVKVQRG | 32 | 4031 |

| PT | PPLSQETFSDLWKLLYGRKKRRQRRR | 26 | 3315 |

| PD3 | PPLSQETFSDLWKLLRKKRRRESRKKRRRES | 31 | 3968 |

| PR9 | PPLSQETFSDLWKLLRRRRRRRRR | 24 | 3179 |

| KGA | KLAKLAKKLAKLAKGGKKWKMRRNQFWVKVQRG | 33 | 3895 |

| BA27 | GRFKRFRKKFKKLFKKLSKKWKMRRNQFWVKVQRG | 35 | 4600 |

| BA28 | GGLRSLGRKILRAWKKYGGKKWKMRRNQFWVKVQRG | 36 | 4374 |

| TK | YGRKKRRQRRRGGKLAKLAKKLAKLAK | 27 | 3179 |

| TB27 | YGRKKRRQRRRGGRFKRFRKKFKKLFKKLS | 30 | 3941 |

| TB28 | YGRKKRRQRRRGGLRSLGRKILRAWKKYG | 29 | 3601 |

| Antp | KKWKMRRNQFWVKVQRG | 17 | 2275 |

| TAT | YGRKKRRQRRR | 11 | 1559 |

| DPV3 | RKKRRRESRKKRRRES | 16 | 2212 |

| R9 | RRRRRRRRR | 9 | 1423 |

| P53(12–26) | PPLSQETFSDLWKLL | 15 | 1773 |

| KLA | KLAKLAKKLAKLAK | 14 | 1523 |

| B27 | GRFKRFRKKFKKLFKKLS | 18 | 2186 |

| B28 | GGLRSLGRKILRAWKKYG | 18 | 2059 |

| URP | DSHAKRHHGYKRKFHEKHHSHRGY | 24 | 3036 |

a aa, amino acid.

Cells and Culture Conditions

Except where noted, all cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The cell lines utilized herein include human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), endothelial cells (ECV304), human proximal tubular cells (HK-2), human skin fibroblast cells (HSF), African green monkey kidney cells (COS-7 and Vero E6), human lung fibroblast cells (MRC-5), human cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa), human prostate cancer cells (DU145), human lung non-small-cell carcinoma cells (A549), human skin malignant melanoma cells (A375), human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), human fibrosarcoma cells (HT1080), bone marrow chronic myelogenous leukemia cells (K562), B lymphocyte Burkitt's lymphoma cells (Raji), T lymphoblast acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (Molt4), and rat glioma cells (C6). Human cardiac myocyte cells (HCM) were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories. Human liver cells (L02), human decidual stromal cells (DSCs), and human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-435S) were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Science. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs) from healthy donors were isolated by low-density (Ficoll-Paque PLUS, 1.077 g/ml) gradient centrifugation. All of the cells were cultured in either Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) or RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Cellular Uptake of Peptides

The cellular uptake of peptides was examined using the methods described by Mueller et al. (25) with some modifications. Briefly, after incubating with FITC-peptide, the cells (2 × 105 per well in 6-well plate) were washed two times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 137 mm NaCl, 2.68 mm KCl, 8.09 mm Na2HPO4, 1.76 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4). The cells were either observed via fluorescence microscopy or lysed with 1.0 ml buffer (8.0 m urea, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) for 30 min at 4 °C. The fluorescence intensity and protein content of cell lysates were measured. The amount of internalized peptide was expressed as the signal intensity (SI), reflecting the ratio of the fluorescence absorbance to the total protein produced by the collected cells. To detect the intracellular concentration of a peptide, the cells were treated with trypan blue (200 μg/ml, 400 μl) for 1 min to quench the surface bound FITC-peptide (33) before lysing.

Cytotoxicity Assays

The adherent cells (1 × 104 cells per well) were plated in a 96-well plate and allowed to further attach for 12–18 h. The cells were washed once with medium lacking serum, and peptides were added to the cells in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 containing 2% bovine serum albumin. The same amount of suspension cells were collected and seeded in the 96-well plate immediately before addition of the peptide. After incubation at 37 °C for 1–2 h, 10 μl CCK-8 solution was added to the well, and the cultures were further incubated for 2–4 h. Samples were prepared in triplicate and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The cytotoxicity of the peptides is expressed as the percentage viability of the cells that were treated with a control peptide, URP. The IC50 values of the peptides were obtained from their respective cell viability curves. The Live/Dead BacLight bacterial viability kit (Molecular Probe) was used as an additional method to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the peptides. Based on the differences in membrane permeability, the Syto 9 and propidium iodide (PI) mixture stained living cells green and dead cells red.

Apoptosis Assays

Apoptosis assays were performed according to Rege et al. (29). Briefly, the presence of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer membranes of cells, which identifies early apoptosis, was detected using an FITC-Annexin V/PI kit (Invitrogen). The Annexin V+/PI- and Annexin V+/PI+ cells were considered to be apoptotic and necrotic cells, respectively. Mitochondrial depolarization was examined by JC-1 staining (Invitrogen). The pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-Fmk (Invitrogen) was used to probe the possible involvement of the caspase-mediated apoptotic pathway.

Binding of Peptides to Glycosaminoglycans

The binding affinity of the peptides for the GAGs was determined on the basis of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (34). Peptide solutions (2 μm, in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mm NaCl) containing increasing concentrations (0–3 μg/ml) of GAGs were incubated at 20 °C for 30 min to reach a binding equilibrium. Fluorescence spectra in the range of 300–400 nm were measured on a Hitachi F-7000 fluorescence spectrofluorometer at an excitation wavelength of 280 nm. The binding of affinity of the peptides to the GAGs was identified by an increase in the ratio of fluorescence intensity of a peptide incubated with GAG (F) to that of a peptide incubated without GAG (F0). The peptide-GAG complex was also isolated from unbound peptide by HPLC using a Superose 12 HR 10/30 column. The bound peptide was further dissociated from the peptide-GAG complex in the presence of 500 mm NaCl. Then, the bound peptide was isolated by RP-HPLC using a Jupiter Proteo column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex) and identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Effect of Glycosaminoglycans on Cellular Translocation and Cytotoxicity of Peptides

The peptides were preincubated with GAGs at 37 °C for 5 min and then added to cells. The cytotoxicity of a peptide was detected using a peptide control that had not been preincubated with GAGs. An antibody (CS-56, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) against CS was used to evaluate the expression of CS by flow cytometry (FACS). To remove cell surface CS, cells were digested with chondroitinase ABC (Sigma) for 1 h according to the instructions. The cellular translocation of peptides into the cells, and the cytotoxic effects of peptides on the cells were determined for both digested and undigested cells.

In Vivo Mouse Tumor Xenograft Models

All protocols for the in vivo experiments were approved by the University Animal Care and Use Committee. Six- to eight-week-old female BALB/c nu/nu mice were obtained from the University Animal Production Center. Pooled tumor cells (6 × 106 cells in 200 μl saline) were injected subcutaneously into the front limb regions of mice. At the onset of a palpable tumor (30∼50 mm3), the mice were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Mice in the treatment group (n = 5) were intraperitoneally injected with 20 mg/kg peptide on a daily basis for five consecutive days, and mice in the control group (n = 5) were injected with equivalent volumes of PBS. The tumor volume (mm3) was calculated as length × width2 × 0.5. The intratumor experiments were performed according to the description provided by Law et al. (35). When the tumor sizes were ∼300–500 mm3, 100 μg of peptide per 100 μl of PBS was injected into the tumor. An equal volume of PBS was injected into the control tumor. The animals were sacrificed 24 h post-injection. Tumor tissues were excised, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E to examine the histological architecture. Primary rabbit polyclonal antibody against human cleaved caspase-3 (Asp-175, Cell Signaling) and TUNEL staining (Invitrogen) were used to evaluate the apoptosis of tumor cells. Simultaneously, the histological architecture of important organs from mice intraperitoneally and intratumorally injected with peptides were examined by H&E staining and compared with that of mice in the control group.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of at least three experiments. Multiple comparisons were made with SPSS software.

RESULTS

The Leader Peptide Penetratin (Antp) Contributes to the Preferential Cytotoxicity of PNC27

PNC27, containing the leader peptide Antp and the N-terminal domain of p53 (12–26 amino acids), was previously found to be preferentially cytotoxic to tumor cells (14–17). We first assessed the cytotoxicity of PNC27 to both tumor and normal cells in vitro. As shown in Fig. 1A, PNC27 induces obvious toxicity in a variety of tumor cells, including HeLa, MDA-MB-435S, and MDA-MB-231 cells. The IC50 value of PNC27 in the tumor cells was within the range of 15–20 μm. In contrast, the normal cells (HUVECs, ECV304, and L02) were generally more resistant to PNC27 (with IC50 values over 50 μm). These results indicate that PNC27 is preferentially cytotoxic to tumor cells. In contrast, the chimeric peptides, PT, PD3, and PR9, that used other CPPs as their leader peptides, displayed a similar degree of toxicity in tumor and normal cells (Fig. 1, B–D). The unconjugated leader peptides Antp, TAT, R9, and DPV3, as well as the p53 (12–26 amino acids) domain were nontoxic to all tested cells, even at high concentrations of 100 μm (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the leader peptide Antp determines the specificity of PNC27 cytotoxicity.

FIGURE 1.

PNC27 preferentially kills tumor cells. Cells (1 × 104 per well) were treated with increasing concentrations of the peptide PNC27 (A), PD3 (B), PR9 (C), or PT (D) for 2 h. Cell viability was determined using CCK-8 and compared with the controls (cells treated with the peptide URP). Experiments were performed three times, and the results are expressed as mean ± S.D.

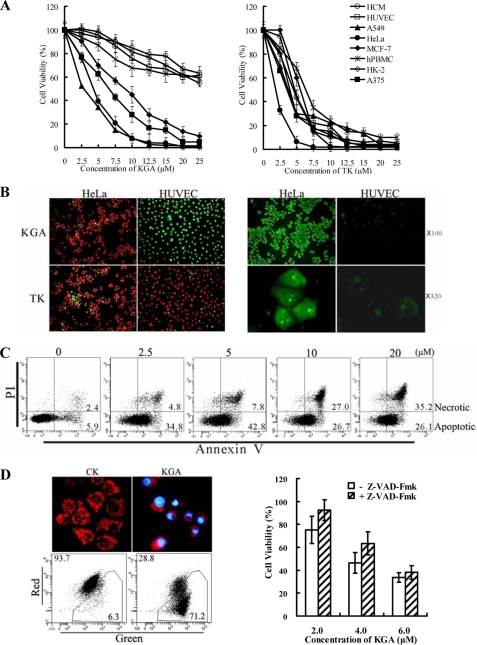

The Antp-KLA Fusion Peptide KGA Preferentially Induces Apoptosis in Tumor Cells

Supplemental Fig. S1A shows that the KLA-Antp conjugate KGA induced ∼50–90% cell death in HeLa cells at concentrations ranging from 2.5–10 μm. The loss of viability in HeLa cells was accompanied by condensed nuclei, rounding and cell detachment (supplemental Fig. S1B). In contrast, the unconjugated Antp, KLA, and the control peptide URP were nontoxic to HeLa cells even at high concentration of 25 μm. These data indicate that conjugation to Antp significantly enhanced the cytotoxicity of KLA peptide in tumor cells. Time-course assays demonstrate that KGA exerts cytotoxicity in tumor cells within 5 min (supplemental Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 2A, tumor cells, including HeLa, A549, A375, and MCF-7 cells, were sensitive to KGA. The IC50 values of KGA in these cells were within the range of 5–10 μm. Conversely, normal cells, such as HUVECs, HCM, hPBMCs, and HK-2, were more resistant to KGA with IC50 values over 25 μm (Fig. 2A, left panel). In contrast to KGA, the chimeric peptide TK (containing KLA and another leader peptide, TAT) showed similar cytotoxicity in both tumor and normal cells (Fig. 2A, right panel). The Live/Dead assay, utilizing double staining with Syto 9 and PI, demonstrated that the sensitivity of HeLa cells to KGA cytotoxicity differed from that of HUVECs (Fig. 2B, left panel). Over 90% of the 1 × 104 HeLa cells and 10% of the HUVECs were killed by KGA at a concentration of 10 μm. However, TK killed about 90% of both cell types at the same concentration. These results indicate that the Antp-directed peptide KGA is preferentially cytotoxic to tumor cells. We also observed a positive association between the cellular translocation and cytotoxicity of KGA. Fig. 2B (right panel) shows that, while KGA penetrated over 90% of the HeLa cells, it only penetrated about 10–20% of the HUVECs. Moreover, the amount of peptide internalized by individual HeLa cells and HUVECs was also significantly different (Fig. 2B, right panel). In contrast, TK was internalized to a similar extent by HeLa and HUVECs (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the preferential binding/penetration of the leader peptide Antp to tumor cells contributes to the preferential cytotoxicity of KGA.

FIGURE 2.

Antp-directed peptide KGA preferentially kills tumor cells by induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis. A, cytotoxicity of KGA (left panel) and TK (right panel) to tumor cells and normal cells. Cells (1 × 104 per well) were treated with increasing concentrations of peptide for 1 h, and cell viability was determined using CCK-8. B, positive association between cell death and cellular translocation of KGA. Live/dead assays for HeLa and HUVEC cells treated with KGA or TK (left panel) and uptake of KGA by HeLa and HUVEC cells (right panel). To illustrate the live and dead cells simultaneously, the cells were double-stained with Syto 9 and PI after treatment with 10 μm peptide for 1 h. The live and dead cells were visualized as green and red, respectively. To evaluate the cellular uptake of peptide, the cells were observed under fluorescence microscopy after incubation with 10 μm FITC-labeled KGA at 37 °C for 30 min. C, FACS analysis for KGA-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells. After treatment with KGA for 10 min at the relevant concentrations, the cells (1.5 × 105 in 300 μl medium) were double-stained with FITC-Annexin V and PI and analyzed by FACS. D, involvement of caspase pathway in KGA-induced apoptosis. KGA caused reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential in HeLa cells (left panel) and suppression of pan-caspase inhibitor on KGA-induced cell death (right panel). Mitochondria in cells treated or untreated with peptide were visualized by JC-1 staining. Nuclei were illustrated by DAPI staining. Healthy mitochondria were observed as red granules. The loss of mitochondrial membrane potential was reflected by a decrease in the ratio of red fluorescent to green fluorescent cells, as measured by FACS. To probe the involvement of caspase-dependent pathway, cells were preincubated with 100 μm pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-Fmk for 2 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the cytotoxicity of KGA (2–6 μm) to HeLa cells was detected using a CCK-8 assay.

Phosphatidylserine assays demonstrated that KGA induces apoptosis of HeLa cells. After treatment with 0, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 μm KGA, the percentage ratio of apoptotic/necrotic cells, as determined by FACS, were 5.9/2.4, 34.8/4.8, 42.8/7.8, 26.7/27, and 26.1/35.2, respectively (Fig. 2C). The KGA peptide translocated to mitochondria shortly after entering the cell (5–10 min) (supplemental Fig. S5A). About 1 h later, the granule-like mitochondria were absent in most cells treated with KGA (Fig. 2D, left panel). Significant decreases in the membrane potentials of mitochondria were revealed by changes in the red/green fluorescence ratio from 93.7/6.3 to 28.8/71.2 after treatment with 40 μm KGA (Fig. 2D, left panel). Furthermore, exposure to the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-Fmk reduced the 2–6 μm KGA-induced death of HeLa cells by 5–20% (Fig. 2D, right panel). Taken together, these data indicate that KGA induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in tumor cells.

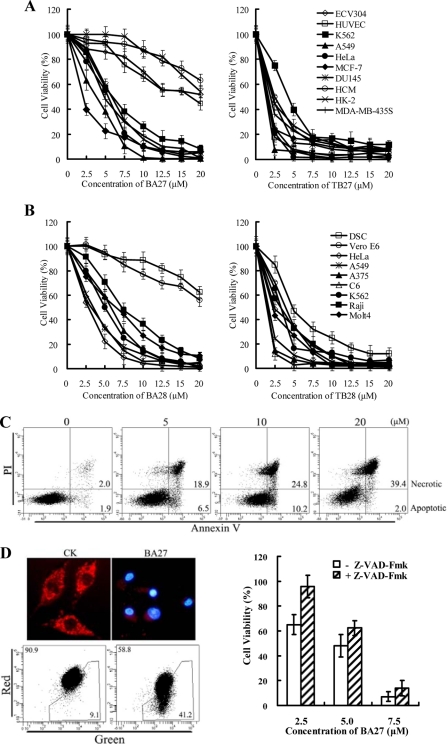

The Antp-truncated BMAP Fusion Peptides BA27 and BA28 Preferentially Induce Apoptosis in Tumor Cells

As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, unconjugated B27 only induced mild (<20% cell death) cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-435S at 12.5 μm. The B27-Antp conjugated BA27 induced ∼50–80% cell death at 5–10 μm. This indicates that the B27-Antp conjugate enhanced cytotoxicity in tumor cell. Supplemental Fig. S3 shows that conjugation of B28 to Antp also significantly increased its cytotoxicity in K562 cells. The results of time course assays demonstrate that BA27 and BA28 kill tumor cells rapidly (supplemental Fig. S4). Fig. 3a (left panel) shows that BA27 was toxic to tumor cells, including HeLa, A549, MCF7, MDA-MB-435S, DU145, and K562 cells with IC50 values ranging from 3 to 6 μm. BA27 was, however, relatively nontoxic to normal cells, such as ECV304, HUVECs, HCM, and HK2. The IC50 values of BA27 in these normal cells more than 20 μm. Fig. 3b (left panel) shows that BA28 was also more cytotoxic to tumor cells than to normal cells. The IC50 values of BA28 in the tumor cells were between 3 and 8 μm, while the IC50 values of B28 in normal cells were more than 20 μm. TB27 and TB28, however, were similarly toxic to both tumor and normal cells (Fig. 3, A and B, right panel). These data indicate that the leader peptide Antp renders both BA27 and BA28 preferentially cytotoxic to tumor.

FIGURE 3.

Antp-directed peptides BA27 and BA28 preferentially kill tumor cells by induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis. Cytotoxicity of (A) BA27 (left panel), TB27 (right panel), (B) BA28 (left panel), and TB28 (right panel) to tumor cells and normal cells is shown. Cells (1 × 104 per well) were treated with various concentrations of the peptides for 1 h, and cell viability was determined using CCK-8. The results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of at least three similar experiments. C, FACS analysis to detect BA27-induced apoptosis in MDA-MB-435S cells. D, involvement of the caspase-dependent pathway in BA27-induced apoptosis. BA27 caused a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (left panel) and suppression of pan-caspase inhibitor on BA27-induced cell death in MDA-MB-435S cells. All experimental procedures are described in the legend for Fig. 2.

Phosphatidylserine assays demonstrated that BA27 induces apoptosis of MDA-MB-435S cells. After treatment with 0, 5, 10, and 20 μm BA27 for 10 min, the percentage ratios of apoptotic/necrotic cells, as determined by FACS, were 1.9/2.0, 6.5/18.9, 10.2/24.8, and 2.0/39.4, respectively (Fig. 3C). The BA27 peptide translocated to the mitochondria shortly after entering the cell (5–10 min) (supplemental Fig. S5A). The apoptosis of BA27-treated tumor cells was accompanied by the disappearance of granule-like mitochondria. The loss of mitochondrial membrane potential was determined by the change in the red/green fluorescence ratio, which decreased from 90.9/9.1 to 58.8/41.2 (Fig. 3D, left panel). Moreover, in the presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-Fmk, the 2.5–7.5 μm BA27-induced death of MDA-MB-435S cells was reduced by 5–30% (Fig. 3D, right panel). These results demonstrate that BA27 kills tumor cells by inducing caspase-dependent apoptosis. Moreover, the pathway involved in BA28-induced cell death was similar to that initiated by BA27 (data not shown).

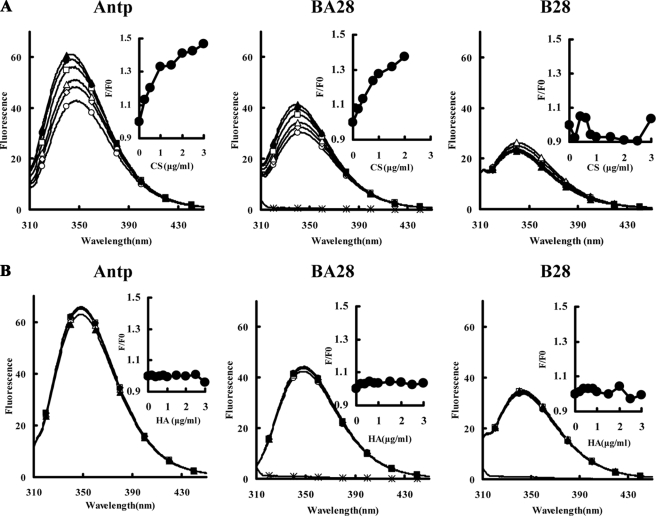

Penetratin (Antp) Contributes to the Binding of Antp-directed Mitochondria-disrupting Peptides to GAGs

The binding of peptides to GAGs was determined on the basis of the changes in intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence upon binding. A fixed concentration of a peptide was mixed with various concentrations of GAGs, and the fluorescence spectra were measured at equilibrium. As shown in Fig. 4A, the maximum emission wavelength (λmax) for Antp was 348.4 nm. An increase in the CS concentration blue-shifted the λmax to 342.8 nm and the emission intensities at 342.8 nm were increased in a CS-dependent manner (Fig. 4A, inset). These results indicate that the binding of Antp to CS causes a change in fluorescence. Similarly, the λmax of BA28 also blue-shifted from 347.6 nm to 339.6 nm and the emission intensities at 339.6 nm increased in a CS-dependent manner. No obvious λmax blue shift and intensity enhancement were observed after the unconjugated B28 was incubated with CS, however, indicating that the unconjugated B28 has weak affinity for CS (Fig. 4A). Taken together, these results suggest that Antp binds to CS and that this binding leads to the binding of Antp-directed peptides to CS. No obvious λmax blue shift and intensity enhancement were detected after peptides were incubated with sodium hyaluronate (HA) (Fig. 4B), suggesting that all the peptides tested have weak affinity for HA. The binding of KGA and BA27 to CS, but not HA, was also confirmed using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence assays (not shown). In contrast, TB28 showed high affinity for both CS and HA (supplemental Fig. S6), which might be an important cause for the nonspecific cell penetration of TAT and TAT-directed peptides.

FIGURE 4.

Binding of Antp and Antp-directed peptide BA28 to CS (A) and HA (B). The binding affinity of peptides for GAG was determined on the basis of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. Peptide (2 μm) was incubated with 0 (open circles), 0.2 (open diamonds), 0.4 (open triangles), 1 (open squares), 1.5 (closed circles), or 2 μg/ml (closed triangles) GAGs at 20 °C for 30 min. Then the fluorescence spectra in the range of 300–400 nm were measured on a Hitachi F-7000 fluorescence spectrofluorometer at an excitation wavelength of 280 nm. The binding of peptide to GAG was reflected by the enhancement of the ratio of fluorescence intensity of peptide incubated with GAG (F) to that of peptide incubated without GAG (F0). The fluorescence intensity of GAG (2 μg/ml, asterisk) was also detected. Inset, relative fluorescence intensities (F/F0) were plotted. The experiments were performed three times, and the representative data are shown.

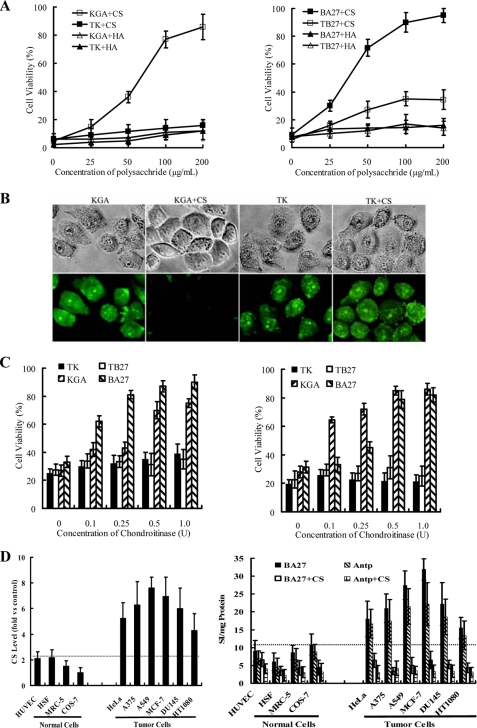

Chondroitin Sulfate Glycosaminoglycan Inhibits the Cellular Translocation and Reduces the Cytotoxicity of Antp-directed Mitochondria-disrupting Peptides

To identify the binding target of peptides on tumor cells, we first examined the effect of inhibition by exogenous GAGs, including CS and HA, on the cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides. We found that preincubation of peptides with CS (50–200 μg/ml) significantly (30–90%) reduced cell death in HeLa cells exposed to 10 μm KGA (Fig. 5A, left panel) or BA27 (Fig. 5B, right panel). Exogenous CS (100 μg/ml) was observed to block the cellular translocation of FITC-labeled KGA into HeLa cells (Fig. 5B). However, exogenous HA had no effect on the cytotoxicity of the Antp-directed peptides. We propose that CS may be the binding target that mediates the cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides. To further confirm the role of endogenous CS in mediating the cytotoxicity of the Antp-directed peptides, we examined the cytotoxicity of these peptides to tumor cells where the surface CS had been removed by chondroitinase ABC. When the chondroitinase- digested HeLa (Fig. 5C, left panel) and A549 (Fig. 5C, right panel) cells were exposed to 5 μm KGA or BA27, cellular viability increased from 30–40% to 60–90% in a dose-dependent manner with increasing concentrations of chondroitinase. These results demonstrate that CS on tumor cells serves as an important molecular portal that mediates the cytotoxicity of KGA and BA28. The surface CS levels were found to be about 2–5 times higher on tumor cells than on normal cells (Fig. 5D, left panel). Intracellular content of both unconjugated Antp and the Antp-directed peptide BA27 in tumor cells is 2–3-fold higher than that in the normal cells (Fig. 5D, right panel). The positive association between the cell entry of the peptides and the level of surface CS suggests that the overexpression of surface CS on tumor cells contributes to the preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides. Neither the preincubation of the peptides with CS (Fig. 5A) nor the removal of surface CS (Fig. 5C) (<10%) protected HeLa and A549 cells when exposed to TK or TB27. This result indicates that TAT- and Antp-directed peptides rely on different molecules for initial membrane binding and cell entry.

FIGURE 5.

Surface CS mediates the cellular uptake and preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides. A, GAG-mediated inhibition of Antp-directed peptide-induced cytotoxicity in HeLa cells. Prior to cell treatment, peptides were mixed with increasing concentrations of GAGs, CS, and HA, and were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. The cytotoxicity of the peptides was determined by CCK-8. The results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of three similar experiments. B, blockade of the cellular translocation of KGA into HeLa cells by exogenous CS. FITC-labeled peptides KGA or TK (10 μm) were incubated with HeLa cells in the presence or absence of 100 μg/ml CS for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were then observed under fluorescence microscopy (original magnification ×320). C, enzymatic removal of CS reduced the cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides to HeLa cells (left panel) and A549 cells (right panel). To remove the surface CS, chondroitinase ABC was used to digest the cells at 37 °C for 1 h. The cytotoxicity of the peptides (5–7.5 μm) to cells was then assessed by CCK-8. D, overexpression of surface CS on tumor cells (left panel) and preferential translocation of Antp and BA27 into tumor cells (right panel). The expression of CS was detected by FACS using an antibody against CS (CS-56) with an isotype antibody as a control. Cellular uptake of Antp and BA27 by tumor cells and normal cells was detected in the presence or absence of 100 μg/ml CS. The cellular uptake of Antp shown here reflects the intracellular concentration of the peptide. Before the addition of 8 m urea to the cells, the extracellular FITC-Antp was quenched by trypan blue as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Three similar experiments were performed, and the results are expressed as mean ± S.D.

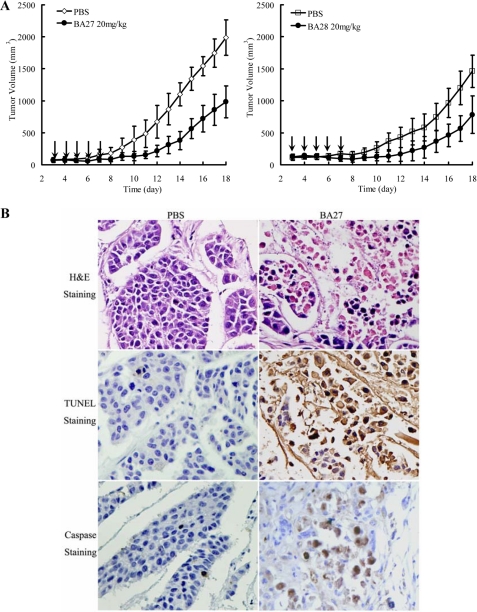

Penetratin (Antp)-directed Mitochondria-disrupting Peptides BA27 and BA28 Suppress Tumor Growth in Vivo

As shown in Fig. 6A (left panel), intraperitoneal injection of BA27 (20 mg/kg) substantially suppressed the growth of tumor xenografts. From day 12 through completion of the study, the mean tumor volume of BA27-treated mice was significantly different (p < 0.01) from the control group. BA28 (20 mg/kg) also demonstrated a tumor-suppressing effect. The mean tumor volume of BA28-treated mice was significantly different (p < 0.01) from the control group beginning on day 16 (Fig. 6A, right panel). Following the injection of the tumors with 100 μg of BA27 for 24 h, extensive necrotic areas, TUNEL, and cleaved caspase-3-positive staining were observed in the cell residues at the injection sites (Fig. 6B), indicating that BA27 induced caspase-dependent apoptosis of tumor cells in vivo. At the end of the experiment, no obvious histological damage was observed to the liver, kidney, and heart of mice injected intraperitoneally and intratumorally with peptides (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Suppression of Antp-directed peptides BA27 and BA28 on tumor growth in vivo. A, BA27 (left panel) and BA28 (right panel) inhibited the growth of HeLa tumor xenografts in vivo. Tumors were established in BALB/c nude mice by subcutaneous injection of 6 × 106 HeLa cells in 200 μl of saline. After 3 days, the mice (n = 5 per group) were intraperitoneally injected with either 20 mg/kg peptide (treatment group) or equivalent volumes of PBS (control group) on a daily basis for 5 consecutive days (indicated by arrows). Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated as length × width2 ×0.5. B, BA27 mediates apoptosis of HeLa cells in vivo. The mice bearing HeLa xenografts (300–500 mm3) were administered 100 μg of BA27 per 100 μl of PBS (treatment group) or equivalent volumes of PBS (control group) by intratumor injection. The mice were sacrificed 24 h post-injection, and the tumor tissues were excised, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E, TUNEL, and antibody against cleaved caspase-3 (original magnification ×400).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have constructed three novel chimeric peptides by attaching the leader peptide Antp to one of three mitochondria-disrupting peptides. After comparing the cytotoxicity of the novel Antp-directed peptides to that of other CPP-directed peptides, we have provided the first evidence that Antp-directed peptides (KGA, BA27, and BA28) are preferentially cytotoxic to tumor cells and that Antp contributes to this preferential cytotoxicity. We used experiments in which the three novel peptides were preincubated with exogenous GAGs or the endogenous cell surface GAGs were enzymatically removed. The results of these experiments indicate that surface CS is an important molecular portal for the internalization of Antp-directed peptides. Our results also suggest that the initial binding of Antp-directed peptides to surface CS, known to be overexpressed on tumor cells, contributes to the preferential cytotoxicity.

Because of their ability to cross the plasma membrane with high efficacy, CPPs have received a great deal of attention as potential transporters of peptide- and protein-based drugs (4). The ability of CPPs to enter a cell may be an important determinant of the fate of cargos that are unable to enter cells by themselves. Although variable uptake efficacy by different cell types has been observed (20, 25, 36), the penetration of cells by CPPs is generally believed to be nonspecific. We found that conjugation of the p53 (12–26 amino acids) domain to different CPPs, however, resulted in differences in cytotoxicity. Of these CPPs, TAT, R9, and DPV3-directed p53 peptides (PT, PR9, and PD3, respectively) killed tumor cells and normal cells in similar numbers (Fig. 1, B–D). In contrast, Antp-directed p53-peptide (PNC27) preferentially killed tumor cells with IC50 values that were 2–3 times lower than those obtained for normal cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the Antp-directed mitochondria-disrupting peptides, KGA (Fig. 2A, left panel), BA27 (Fig. 3A, left panel), and BA28 (Fig. 3B, left panel), were also preferentially cytotoxic to tumor cells and had IC50 values that were 3–6 times lower than those observed for normal cells. The TAT-directed mitochondria-disrupting peptides, TK (Fig. 2A, right panel), TB27 (Fig. 3A, right panel), and TB28 (Fig. 3B, right panel), were equally cytotoxic to both tumor and normal cells. These results demonstrate that the leader peptide Antp contributes to the cytotoxic preference of Antp-directed peptides to tumor cells.

Unraveling the mechanisms that underlie CPP cell entry may aid in understanding the contribution of Antp to the preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides. It is accepted that CPP-mediated cell penetration consists of three steps: 1) binding to some component of the plasma membrane, 2) cell entry, and 3) subsequent release into the cytoplasm (22). Historically, CPPs were thought to bind to and directly cross the plasma membrane in a receptor- and energy-independent manner (21–23). In recent years, direct translocation of CPPs has only been observed in areas of high CPP concentrations. At low micromolar concentrations, CPPs exhibit high affinity for cell surface GAGs and low affinity for the plasma membrane. Under these conditions, GAG-mediated transport appears to be the dominant uptake route for CPPs, while direct membrane penetration appears to contribute minimally (4, 23, 37). It is possible, however, for low concentrations of CPPs to show heterogeneity in their ability to bind to and penetrate cells that express different surface GAGs.

GAGs are distributed as side chains of proteoglycans on the cell surface or in the extracellular matrix. They mediate the cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions that are essential for local tumor cell invasion and metastasis (27, 38). Previous work has shown that CS is overexpressed in most malignancies, including brain tumors, osteosarcomas, lymphomas, histiocytoma, melanoma, breast, prostate, pancreatic, endometrial, oral, ovarian, testicular, laryngeal, gastric, lung, and monocytic leukemia cells (27, 39, 40). In our experiments, we found that Antp and Antp-directed peptides bind to CS (Fig. 4A) and that the presence of CS in the medium strongly (30–90%) inhibits both KGA- and BA27-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 5A). Moreover, enzymatic removal of CS significantly (30–50%) reduced the cytotoxicity of KGA and BA27 to tumor cells (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that in tumor cells, CS is an important molecular portal for internalization of Antp-directed peptides. We also found that CS to be overexpressed on the tumor cells we tested and the cellular translocation of Antp and Antp-directed peptide BA27 to be positively related to the CS levels on tumor cells (Fig. 5D). In addition, we compared the CS levels and the cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides in untransformed fibroblast HSF and Ras-transformed fibroblast HT1080 cells. Our results indicate that the cytotoxicity of Antp-directed peptides is related to CS levels on both cell types (supplemental Fig. S7). These findings suggest that it is the initial binding of peptides to the overexpressed surface CS on tumor cells that contributes to the preferential cytotoxicity of Antp-directed mitochondria-disrupting peptides. Console et al. (20), however, reported that preincubation of the peptide with CS (20 μg/ml) did not block the cellular uptake of Antp. One possible reason for this disparity is that the concentration of CS used in their experiment was too low to significantly inhibit the cellular uptake of Antp. In fact, we did not detect any obvious inhibition of the cytotoxicity of the Antp-directed mitochondria-disrupting peptides using a CS concentration of 25 μg/ml. We found the inhibition to be evident (30–90%) when the concentration of CS was increased to at least 50 μg/ml (Fig. 5A).

In previous studies, some CS binding molecules have been found to be important to targeted drug delivery. Lee et al. (41) showed that liposomes containing the cationic lipid 3,5-dipentadecycloxybenz amidine hydrochloride (TRX-20) displayed preferential tumor cell binding due to its affinity for CS GAGs. The TRX-20 liposome was more efficient than plain liposomes for the delivery of cisplatin to chondroitin sulfate-expressing cancer cells. Rezler et al. (42) described a triple helical peptide-amphiphile (α1(IV)1263–1277 PA) that specifically bound cell surface CD44/CSPG. A positive correlation between liposome and the CD44/CSPG receptor content in metastatic melanoma and normal fibroblast cell lines was found. Regardless of the CD44/CSPG receptor content, however, nontargeted liposomes delivered minimal fluorophore to these cells. These results demonstrated that the overexpression of CS on tumor cells is a bona fide target for drug delivery. Because CS is overexpressed on a wide variety of tumor cells, the CPP Antp has the potential to be a drug carrier for targeted cancer therapy because of its affinity for CS. Nevertheless, the cytotoxicity levels of KGA and BA27 in chondrocytes suggests that Antp-directed peptides may also induce nonspecific killing of CS-expressing normal cells by the same mechanism (supplemental Fig. S8). In addition, CS-mediated internalization may represent only one pathway for cell entry by Antp and Antp-directed peptides. These peptides may bind to other surface GAGs or to the negative lipid molecules on cell membranes (21, 23). Therefore, the development of a targeted drug delivery system for cancer therapy will likely require the identification of molecules that show greater specificity for CS.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by National Basic Research Program of China 2009CB522401 (to Y. L.) and Natural Science Fund of China 30873184 (to X. L.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S8.

- CPP

- cell-penetrating peptide

- GAG

- glycosaminoglycan

- CS

- chondroitin sulfate

- FACS

- fluorescent-activated cell sorting

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- H&E

- hematoxylin & eosin

- TUNEL

- terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling

- PI

- propidium iodide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kreitman R. J. (2006) AAPS J. 8, E532–E551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chari R. V. (2008) Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 98–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foerg C., Merkle H. P. (2008) J. Pharm. Sci. 97, 144–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart K. M., Horton K. L., Kelley S. O. (2008) Org. Biomol. Chem. 6, 2242–2255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder E. L., Saenz C. C., Denicourt C., Meade B. R., Cui X. S., Kaplan I. M., Dowdy S. F. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 10646–10650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan M., Lan K. H., Yao J., Lu C. H., Sun M., Neal C. L., Lu J., Yu D. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 3764–3772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myrberg H., Zhang L., Mae M., Langel U. (2008) Bioconjugate Chem. 19, 70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine A. J. (1997) Cell 88, 323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller-Tiemann B. F., Halazonetis T. D., Elting J. J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6079–6084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim A. L., Raffo A. J., Brandt-Rauf P. W., Pincus M. R., Monaco R., Abarzua P., Fine R. L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 34924–34931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y., Rosal R. V., Brandt-Rauf P. W., Fine R. L. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 298, 439–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y., Mao Y., Rosal R. V., Dinnen R. D., Williams A. C., Brandt-Rauf P. W., Fine R. L. (2005) Int. J. Cancer 115, 55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senatus P. B., Li Y., Mandigo C., Nichols G., Moise G., Mao Y., Brown M. D., Anderson R. C., Parsa A. T., Brandt-Rauf P. W., Bruce J. N., Fine R. L. (2006) Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowne W. B., Michl J., Bluth M. H., Zenilman M. E., Pincus M. R. (2007) Cancer Ther. 5B, 331–344 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanovsky M., Raffo A., Drew L., Rosal R., Do T., Friedman F. K., Rubinstein P., Visser J., Robinson R., Brandt-Rauf P. W., Michl J., Fine R. L., Pincus M. R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12438–12443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Do T. N., Rosal R. V., Drew L., Raffo A. J., Michl J., Pincus M. R., Friedman F. K., Petrylak D. P., Cassai N., Szmulewicz J., Sidhu G., Fine R. L., Brandt-Rauf P. W. (2003) Oncogene 22, 1431–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michl J., Scharf B., Schmidt A., Huynh C., Hannan R., von Gizycki H., Friedman F. K., Brandt-Rauf P., Fine R. L., Pincus M. R. (2006) Int. J. Cancer 119, 1577–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowne W. B., Sookraj K. A., Vishnevetsky M., Adler V., Sarafraz-Yazdi E., Lou S., Koenke J., Shteyler V., Ikram K., Harding M., Bluth M. H., Ng M., Brandt-Rauf P. W., Hannan R., Bradu S., Zenilman M. E., Michl J., Pincus M. R. (2008) Ann. Surg. Oncol. 15, 3588–3600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prochiantz A. (2000) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 400–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Console S., Marty C., García-Echeverría C., Schwendener R., Ballmer-Hofer H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35109–35114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poon G. M., Gariépy J. (2007) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 788–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ram N., Aroui S., Jaumain E., Bichraoui H., Mabrouk K., Ronjat M., Lortat-Jacob H., De Waard M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24274–24284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziegler A. (2008) Adv. Drug Deliver Rev. 60, 580–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain M., Chauhan S. C., Singh A. P., Venkatraman G., Colcher D., Batra S. K. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 7840–7846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller J., Kretzschmar I., Volkmer R., Boisguerin P. (2008) Bioconjugate Chem. 19, 2363–2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Götte M., Yip G. W. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 10233–10237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kodama J., Hasengaowa , Kusumoto T., Seki N., Matsuo T., Nakamura K., Hongo A., Hiramatsu Y. (2007) Eur. J. Cancer 43, 1460–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Coupade C., Fittipaldi A., Chagnas V., Michel M., Carlier S., Tasciotti E., Darmon A., Ravel D., Kearsey J., Giacca M., Cailler F. (2005) Biochem. J. 390, 407–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rege K., Patel S. J., Megeed Z., Yarmush M. L. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 6368–6375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skerlavaj B., Gennaro R., Bagella L., Merluzzi L., Risso A., Zanetti M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28375–28381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Risso A., Braidot E., Sordano M. C., Vianello A., Macrì F., Skerlavaj B., Zanetti M., Gennaro R., Bernardi P. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1926–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellerby H. M., Arap W., Ellerby L. M., Kain R., Andrusiak R., Rio G. D., Krajewski S., Lombardo C. R., Rao R., Ruoslahti E., Bredesen D. E., Pasqualini R. (1999) Nat. Med. 5, 1032–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z., Leisner T. M., Parise L. V. (2003) Blood 102, 1307–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuzaki K., Nakamura A., Murase O., Sugishita K., Fujii N., Miyajima K. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 2104–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Law B., Quinti L., Choi Y., Weissleder R., Tung C. H. (2006) Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 1944–1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marty C., Meylan C., Schott H., Ballmer-Hofer K., Schwendener R. A. (2004) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 61, 1785–1794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vivès E., Schmidt J., Pèlegrin A. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1786, 126–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada S., Sugahara K. (2008) Curr. Drug Disc. Technol. 5, 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asimakopoulou A. P., Theocharis A. D., Tzanakakis G. N., Karamanos N. K. (2008) In vivo 22, 385–390 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ricciardelli C., Sakko A. J., Ween M. P., Russell D. L., Horsfall D. J. (2009) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28, 233–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee C. M., Tanaka T., Murai T., Kondo M., Kimura J., Su W., Kitagawa T., Ito T., Matsuda H., Miyasaka M. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 4282–4288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rezler E. M., Khan D. R., Lauer-Fields J., Cudic M., Baronas-Lowell D., Fields G. B. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 4961–4972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.