Abstract

pH is a highly variable environmental factor for the root, and plant cells can modify apoplastic pH for nutrient acquisition and in response to extracellular signals. Nevertheless, surprisingly few effects of external pH on plant gene expression have been reported. We have used microarrays to investigate whether external pH affects global gene expression. In Arabidopsis thaliana roots, 881 genes displayed at least 2-fold changes in transcript abundance 8 h after shifting medium pH from 6.0 to 4.5, identifying pH as a major affector of global gene expression. Several genes responded within 20 min, and gene responses were also observed in leaves of seedling cultures. The pH 4.5 treatment was not associated with abiotic stress, as evaluated from growth and transcriptional response. However, the observed patterns of global gene expression indicated redundancies and interactions between the responses to pH, auxin and pathogen elicitors. In addition, major shifts in gene expression were associated with cell wall modifications and Ca2+ signaling. Correspondingly, a marked overrepresentation of Ca2+/calmodulin-associated motifs was observed in the promoters of pH-responsive genes. This strongly suggests that plant pH recognition involves intracellular Ca2+. Overall, the results emphasize the previously underappreciated role of pH in plant responses to the environment.

Keyword index: Apoplast, Arabidopsis thaliana, Auxin, Calcium, Cell wall, Elicitor, Gene expression, Pathogen response, Transcriptome

INTRODUCTION

pH is a major, variable growth factor in natural and agricultural soils. Rhizosphere pH is connected to many physiological and environmental parameters, like growth, respiration, biotic interactions, the solubility of nutrients and toxic ions, and the leaching of soil anions (Felle et al., 2009, Grignon & Sentenac, 1991, Hinsinger et al., 2003, Sakano, 2001). Plant roots encounter spatial and temporal variations of pH in the soil, and changes in soil water status can substantially modify soil pH (Misra & Tyler, 1999). Furthermore, rhizosphere pH shows diurnal effects, likely due to plant activities. Measurements of pH in the proximity of roots showed a rapid (1 h) increase by 0.5 units upon illumination (Blossfeld & Gansert, 2007). Plants can also modify the rhizophere pH through relative changes in uptake of NH4+ and NO3− to improve cation accessibility. Uptake of NH4+ and NO3− alters the soil pH due to proton extrusion and cotransport, respectively (Crawford & Forde, 2002). Changes in the pH of the medium surrounding Arabidopsis roots have been shown to strongly affect the apoplastic pH, but not cytosolic pH (Gao et al., 2004). In maize roots, measured changes in apoplast and root surface pH were smaller than pH changes in the medium (Felle, 1998), indicating that pH-buffering by plasma membrane transport activities and incomplete diffusion create zones of different external pH in the compartments surrounding the root cells.

According to the “acid growth hypothesis”, plants regulate cell expansion by modifying the pH around the cell wall and thereby its extensibility, which increases at low pH (Cosgrove, 1999). This hypothesis is well accepted in shoots, but results on roots have been less conclusive. Acidification of the medium from pH 6.5 to 5.6 nearly doubled the elasticity of the seminal root in maize, but its elongation was slightly decreased (Bloom, Frensch & Taylor, 2006). However, information is still lacking to confirm and explain these growth theories in connection to soil acidification. Also, root water conductance in birch is decreased when pH is altered from neutral to either acidic or alkaline, but the underlying mechanisms are unknown (Kamaluddin & Zwiazek, 2004). Surprisingly, the role of pH in the regulation of gene expression has been little studied within plant biology.

Bacterial and fungal studies have shown that imposed variations in external pH cause substantial changes in gene expression and cellular biochemistry (Arst & Penalva, 2003, Li et al., 2002). Responses to alterations in external pH in these organisms are mediated by dedicated pH-sensitive cellular signaling pathways (Arst & Penalva, 2003). In fungi and bacteria, external pH change induces the upregulation of a multitude of different processes, including the production of enzymes and toxins. Acidic pH is in several cases one of the signals that regulate the production of virulence factors that contribute to pathogenesis (Li et al., 2002). Transcriptome analysis of Agrobacterium tumefaciens showed two responses to acidic pH- a general adaptation to an acidic environment as well as a specialized acid-mediated signaling response involved in the virulence mechanism (Yuan et al., 2008). Two-component regulatory systems, which control diverse responses in many different organisms, are involved in the regulation of both of these responses in A. tumefaciens. The eukaryotic organism in which gene regulation by external pH has been most studied is the ascomycete fungus Aspergillus nidulans. The A. nidulans regulatory system requires six gene products to transmit the pH signal by an activating, partial proteolysis of the zinc finger PacC transcription factor (Arst & Penalva, 2003). Two gene products (PalI and PalH) are located in the plasma membrane and are thought to be pH sensors. A homolog to PacC, Rim101, has been identified to be involved in pH-signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Platara et al., 2006). However, Rim101 is responsible only for a limited set of pH-induced transcriptional responses, and two additional signaling pathways are involved in the broader pH response. These pathways involve either the protein kinase Snf1 and a repressor complex or calcineurin, which is activated by an intracellular Ca2+ burst caused by exposure to external alkaline pH (Platara et al., 2006).

Among plants, intracellular pH is known to signal light intensity changes, and alterations in internal rootcap pH is likely involved in root gravity perception (Felle, 2001). In contrast, little is known about the effects of external pH on plant gene expression. In a seminal study, both nitrate and pH were shown to be signals regulating the CHL1 gene, which encodes a nitrate transporter (Tsay et al., 1993) that is also involved in nitrate sensing (Ho et al., 2009). The level of CHL1 mRNA in Arabidopsis thaliana roots increased within 2 hours when the pH of the medium was decreased from pH 6.5 to pH 5.5 (Tsay et al., 1993). Likewise, acidic pH increases the expression of iron uptake genes in tomato and the expression of genes encoding a type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenase and an alternative oxidase in A. thaliana (Escobar, Geisler & Rasmusson, 2006, Zhao & Ling, 2007).

In this study we aimed to investigate the root transcriptome response to pH change, to see whether alterations in external pH within a physiological range induce global changes in gene expression, and the magnitude and rate of such effects. We also aimed to investigate the global effects of external pH on cell biology and metabolism, as seen from gene expression associations to known environmental and signal-related cues. In particular, we investigated the potential capacity of pH to mediate and modulate signals in auxin and pathogen responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant growth and experimental treatments

For hydroponic growth of A. thaliana, ecotype Columbia-0, seeds were placed in cut-off 0.5 ml PCR tubes filled with 0.7% agarose and kept at 4°C for two days. The seed holders were then floated on a half-strength nutrient medium as previously described (Somerville & Ogren, 1982) (2.5 mM KNO3, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, pH 5.6, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM Ca(NO3)2, 25 µM Fe-EDTA), supplemented with the reported micronutrient mix at 1X concentration. The plants were moved to a 22°C growth chamber with a 16 h light (80 µmol m−2 sec−1), 8 h darkness cycle. The medium was changed every 10 days.

For A. thaliana ecotype screening experiments, seeds of the ecotypes Columbia-0, New Zealand, and Bensheim were transferred to the nutrient medium described above, but the pH was adjusted to 6.0, 5.25, or 4.5 using HCl. Medium pH was monitored and re-adjusted every second day. Plants were harvested after 19 days, and total plant biomass and root length were determined. For pH switch experiments, the plants were grown to growth stage 5.10 (Boyes et al., 2001) and then transferred to nutrient medium containing 5 mM MES, with pH adjusted to either 6.0 or 4.5. Two days before the pH treatment, the plants were transferred to media containing 5 mM MES, pH 6.0 to avoid effects of the MES-buffer itself on the experiments.

The pH treatments of the hydroponically grown plants were started 4 h after the onset of illumination, and roots from 6–7 plants were excised, pooled and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen after 1 and 8 h of treatment. Three biological replicates (pools of 7 plants, identically treated) were collected for each time-point and pH. For the 8 h incubation, the pH of the growth media was re-set with 0.1M HCl three times during the treatment time. The pH was measured during the treatment and for the pH 4.5 incubation was found to vary between pH 4.5 and pH 4.6, whereas the pH 6.0 incubation did not change.

For sterile growth of A. thaliana in liquid seedling cultures, approximately 125 surface-sterilized seeds were grown in 100 ml of sterile nutrient medium (as above, supplemented with 2% sucrose) in 250 ml flasks. Other growth conditions were as above. After 8 days the medium was replaced with new medium supplemented with 5 mM MES, but pH was maintained at 6.0. On the day of treatment (day 10), the nutrient medium was replaced with new media (containing 5 mM MES) with pH 4.5 and pH 6.0. Samples were removed from the flasks after 20 min, 40 min, 1 h and the seedlings were divided into root and shoot tissues and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. For auxin and flagellin treatments, the medium was supplemented with 1 µM indole-3-acetic acid or 1 µM flagellin (Flg21), roots were excised and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen after 1 h treatment. Due to the relatively small volume of nutrient media compared to plant biomass, pH shifted between pH 4.5 and pH 5.0 in the pH 4.5 incubation media.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and real-time RT PCR

Total RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and real time RT-PCR was carried out using the RNeasy Plant mini kit (Qiagen), RevertAid H minus first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas) and GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega), respectively, but otherwise as previously described (Geisler et al., 2004, Svensson et al., 2002, Svensson & Rasmusson, 2001). For a list of primer sequences see Supplementary Table S1. For intron-containing genes, one primer in each pair was designed to span an exon-exon border, to avoid amplification of genomic DNA. In experiments involving intron-less genes, the total RNA was treated with DNase I (New England Biolabs). All PCR-based experiments were performed with three biological replicates, each containing 2–3 technical replicates. The results were normalized to the expression of actin in the experiments where this decreased the average standard errors for biological replicates.

Array analysis

Three biological replicates for each time-point and pH (in total 12 RNA samples) were used for hybridization to ATH1 microarrays, which was carried out by the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC). The array data was normalized by the robust multiarray average (RMA), (Irizarry et al., 2003), and P-values, adjusted for multiple testing (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995), were calculated with the program affylmGUI in the Bioconductor R package (Smyth, 2004). The ratios between hybridization signals obtained from pH 4.5 and pH 6.0 were calculated, and this value corresponds to the response of each gene to acidic pH. A gene was denoted as pH-responsive if a significant difference (adjusted P-value <0.05), and an at least 2-fold change were observed at pH 4.5, as compared to the control value (pH 6.0). The array data set is deposited at NASC under the experiment reference number 470.

Bioinformatic analyses

BioMaps (www.virtualplant.org) version 1.0 was used to assign pH-responsive genes into GO terms (TAIR/TIGR), with the whole genome as background population. Hypergeometric distribution was used to calculate the P-values of over-representation, and a P-value below 0.01 was set as cut-off value. MapMan, version 8.0, was used to visualize pH-responsive genes after 1 and 8 h treatment, with values presented as log2-ratios. For the hierarchial clustering analysis TIGR Multiexperiment Viewer (MeV), version 4.2.01, was used. A set of publicly available arrays was used for comparisons to pH-responses. Hierarchical clustering (Eisen et al., 1998) combined with support trees (Graur & Li, 2000) was used in the clustering analysis, with 1000 iterations and complete linkage. Bootstrap values below 50 were collapsed. The Hormonometer software (Volodarsky et al., 2009) (http://genome.weizmann.ac.il/hormonometer/) was used for evaluating transcriptome response similarities between hormones and external pH.

Analysis of enriched oligomeric sequences in upstream segments was carried out using the online resource ELEMENT (http://element.cgrb.oregonstate.edu). The program calculated the over-representation of 3–8-mer words as well as adjusted P-values (hypergeometric distribution) for each over-representation (Nemhauser, Mockler & Chory, 2004). The conservation test was made by analyses of orthologs (two-way best Blast hit) to the same set of genes in papaya and poplar using the ELEMENT facility. Analysis of the PLACE database of promoter cis-elements was carried out using the BAR-cistom server (http://www.bar.utoronto.ca).

RESULTS

Growth of A. thaliana at acidic pH

To determine whether A. thaliana Columbia-0 is able to grow in acidic media, and to compare the acid-sensitivity of Columbia-0 with other ecotypes, Columbia-0, New Zealand and Bensheim (the latter two selected for pH tolerance and sensitivity, respectively, in a preliminary screen) were grown in hydroponic cultures at three different pH values (pH 4.5, 5.25 and 6.0). The ecotypes Columbia-0 and New Zealand showed relatively similar total biomass over the tested pH range, whereas Bensheim showed a significantly (P<0.05) lower biomass when grown at pH 4.5 than at pH 6.0 (Supplementary Fig. S1). All three ecotypes showed a significantly shorter root length at pH 4.5 than at pH 5.25. In Bensheim, a significant decrease in root-length was detected at both pH 5.25 and 4.5, as compared to pH 6.0. Columbia-0 showed a significant decrease in the root-length at pH 4.5 compared with pH 6.0, but the reduction in Columbia-0 (31%) was smaller than the corresponding value for Bensheim (60%). Overall, the effect of the acidic growth medium on biomass and root length in the New Zealand and Columbia ecotypes were small or negligible. Therefore, Columbia-0 can be considered relatively acid-tolerant and pH 4.5 was considered suitable for investigating pH effects on the root transcriptome without inducing changes linked to direct cellular damage.

External pH is a major modulator of the root transcriptome

To investigate the transcriptomic effects of changes in the medium pH, hydroponically grown A. thaliana plants (Columbia-0) at growth stage 5.10 (Boyes et al., 2001) were transferred from a basal growth medium (pH 6.0) to an identical medium (pH 6.0) or an acidified medium (pH 4.5) for 1 or 8 hours. RNA was isolated and subsequently used for real-time RT-PCR and microarray analyses. The expression of two known pH-responsive genes in A. thaliana was first examined by real-time RT-PCR, and the results were later compared with the array data. Based upon real-time RT-PCR, transcript abundance of the nitrate transporter gene CHL1 (Tsay et al., 1993) showed a 1.7-fold, statistically significant increase after 8 h of exposure to acidified medium. Corresponding microarray data showed a small (1.4-fold), but statistically significant increase in CHL1 expression after both 1 and 8 h, though this gene was not considered “pH responsive” based upon the microarray analysis criteria (outlined below). The NAD(P)H dehydrogenase gene NDB4 (Escobar et al., 2006) showed a significant 3-fold change after 8 hours in the real-time PCR results. Array analysis revealed no difference, however the hybridisation signals were too weak for relevant comparisons (i.e. they had very low signal values and negative Affymetrix detection calls), consistent with previously reported very low transcript levels for this gene (Escobar et al., 2006).

For analysis of array data, a gene was denoted as pH-responsive when a significant (adjusted P-value < 0.05), at least 2-fold change was observed. After 1 hour of exposure to the acidified medium, 288 genes were found to be pH-responsive (early response genes). Of these, 211 genes were upregulated and 77 were down-regulated (Table I). Among the early pH-response genes, 35 transcription factors were found, the most abundant being members of the AP2 (APETALA2) / EREBPs (ethylene-responsive element binding proteins) family, with 8 genes (Table II). Also, the pathogen defense-related WRKY family is prominent with six induced genes and one repressed gene. After 8 hours of exposure to the acidified medium, 881 genes were responsive by the same criteria, 579 and 302 of which were up- and down-regulated, respectively. Of the 881 genes responsive after 8 h, 748 were assigned as late response genes, by the criterion of not displaying a significant pH response after 1 hour (Table I). The complete list of pH-regulated genes is given in Supplementary Table S2. These results clearly demonstrate that a change in the medium acidity, to a pH that has minor effects on plant growth, has a previously unknown massive effect on gene expression.

Table I.

pH responsive genes

| Response | Early responsive genesa |

Late responsive genesb |

|---|---|---|

| Induced | 211 | 480 |

| Repressed | 77 | 268 |

| Total changed genes | 288 | 748 |

Defined as having a significant, >2-fold change after 1 h plant treatment at pH 4.5. Among these, 99 induced and 44 repressed genes showed persistent changes after 8 h.

Defined as having a significant, >2-fold change after 8 h, but not 1 h.

Table II.

Transcription factors among early pH-responsive genes

| Early pH-responsive genes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| TF family or domaina |

Induced | Repressed | Number of genes |

| AP2-EREBP | AT2G44840, AT5G47220, AT1G21910, AT1G44830, AT1G77640, AT4G17490, AT5G51190 |

AT1G36060 | 8*,b |

| WRKY | AT4G31800 (WRKY18), AT2G38470 (WRKY33), AT5G22570 (WRKY38), AT1G80840 (WRKY40), AT2G46400 (WRKY46), AT3G56400 (WRKY70) |

AT5G15130 (WRKY72) | 7* |

| C2H2 | AT1G27730, AT1G27730, AT2G37430, AT5G22890 |

AT2G28710 | 4* |

| MYB | AT1G57560, AT3G50060, AT5G37260 |

3 | |

| NAC | AT1G01720, AT1G77450, AT5G63790 |

3* | |

| GATA | AT3G54810 | AT2G45050 | 2 |

| MYB-like | AT3G25790 | AT1G71030 | 2 |

| APR | AT3G15540 | 1 | |

| BI3VP1 | AT3G25730 | 1 | |

| bZIP | AT1G13600 | 1 | |

| C3H | AT3G55980 | 1 | |

| HB | AT5G53980 | 1 | |

| HSF | AT5G62020 | 1 | |

| In total | 35 | ||

Categories are according to reported designations(Czechowski et al., 2004).

Significantly different distribution (P<0.05) is denoted by an asterisk.

The transcriptional pH response overlaps with the responses to auxin, salicylic acid and biotic agents

The BioMaps service (www.virtualplant.org) was used to analyze the pH responsive genes depending on their function in the plant. BioMaps categorizes genes based upon Gene Ontology (GO) terms and identifies GO-terms that are over-represented in the dataset. The threshold for a significantly over-represented category was set to a p-value of less than 0.01. The vast majority of the pH responsive genes are associated to the category “responses to stimulus” (P = 2.2 × 10−11) (Supplementary Table S3). In this group, GO categories related to biotic stimulus and defense are clearly overrepresented among the pH-responsive genes, whereas responses to abiotic stimuli are not associated with pH changes. Our set of pH-regulated genes was also compared to data from previously described transcriptional profiling experiments that were focused on plant responses to various types of abiotic and biotic stress as well as hormones associated with such stresses. Hierarchical clustering of the array data was performed using the TIGR MultiExperiment Viewer. In this analysis, transcriptional responses to abiotic treatments (cold, salt, drought, etc.) clearly cluster separately from the pH data (Fig. 1). This distinction between the transcriptional response to acidic pH and transcriptional responses to abiotic stressors is consistent with the absence of a significant growth retardation in A. thaliana (Columbia-0) plants grown continuously at pH 4.5 (Fig. 1). The pH-regulated gene set instead clearly clusters with transcriptional responses to a variety of pathogens, pathogen elicitors, and defense-associated hormones. This includes salicylic acid, which is one of the central signaling compounds in pathogen defense signaling. For example, At1g74710 (ICS1/SID2), the key gene involved in salicylic acid biosynthesis (Metraux, 2002) is up-regulated 5-fold 8 h after the pH shift. The same pattern can also be seen in Supplementary Table S3, where the response to salicylic acid is over-represented in both early and late pH responses. Also, auxin is significantly over-represented among the GO-terms, 5-fold higher than expected for the early pH-responsive genes (Supplementary Table S3), as well as grouping with pH changes in the cluster analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of transcript profile data from plants exposed to acidic pH, hormones, biotic stressors and abiotic stressors. Bootstrap values below 50 have been collapsed. Numbers within brackets refer to NASC arrays experiment reference numbers. For further information about the array experiments see Supplementary Table S4. Ox. stress, oxidative stress; Osm. stress, osmotic stress; IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; ACC, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid; MJ, methyl jasmonate; SA, salicylic acid; E. orontii, Erysiphe orontii; P. infestans Phytophthora infestans; P. syringae; Pseudomonas syringae

Since two hormones, salicylic acid and auxin, were found associated with the pH response in both hierarchical clustering as well as by BioMaps analysis, other hormones were also investigated. The pH-responsive genes were analyzed by the Hormonometer (Volodarsky et al., 2009), where the pH data was compared by correlation analysis with a curated set of ATH1 arrays for different hormone treatments (Fig. 2). A strong correlation between the rapid pH response and the transcriptional response to short-term auxin treatment (30 and 60 min) is evident. The transcriptional response to salicylic acid (3 h) also shows a positive correlation to late pH responses. Among other hormonal responses, only weak correlations to the pH response can be observed (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the transcriptional pH response and hormone responses. The pH response was analyzed using Hormonometer software, which compares the behavior of indexed genes to the response to different hormones. A positive correlation between the external pH shift and a hormone treatment is denoted in red, while blue corresponds to a negative correlation. Absolute values above 0.12 are the results of non-random correlations. ACC, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid

Active apoplastic acidification and alkalinization are known cellular responses to auxin and pathogens, respectively (Felle, 2001). Therefore, the similarity between the transcriptomic response to medium pH changes and the responses to auxin and biotic stimuli prompted us to further investigate the interrelationship between acidic pH and the other stimuli. Seedlings cultured in liquid medium at pH 6.0 were treated with a shift in pH to 4.5 or replenishment of medium at pH 6.0. At the same time, 1 h auxin treatments were carried out at both pHs. An identical setup was made for the elicitor flagellin. Genes showing an induced response overlap between pH and auxin or flagellin treatment were investigated by real-time RT-PCR analysis of root RNA (Fig. 3). All seven genes were significantly induced by the pH 4.5 treatment (consistent with the microarray results) and by IAA, and four genes were significantly induced by flagellin. The data revealed that for all genes, a variable portion of the auxin response was controlled by pH alone, up to a complete exchangeability of auxin for pH seen for the transcription factors WRKY40 (At1g80840) and ERF6 (At4g17490), and a pectinesterase family protein (At2g47550). Combining the treatments did not lead to a substantial further increase in expression. As a result, the auxin-mediated induction of gene expression was for all tested genes reduced or absent at pH 4.5, and the pH response was reciprocally muted by the presence of auxin. For the flagellin-induced genes a similar pattern was observed. Flagellin and pH 4.5 induced similar changes in gene expression, and the combination of the treatments generally did not result in a synergistic enhancement of gene expression. These results suggest that changes in external pH may act as an underlying signal which modifies the auxin- and pathogen-responses for many genes.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional changes in roots of A. thaliana seedlings in response to acidic pH, auxin and flagellin. The seedlings were treated at pH 4.5 or 6.0 for 1 h. Where denoted, 1 µM indole-3-acetic acid (A) or 1 µM flagellin 21 (B) was added to the medium at the time of the pH shift. Gene expression is shown as average mRNA levels ± SEM for three biological replicates. The control value for each gene at pH 6.0 was set to 100%, and significant differences (T-test, P< 0.05) compared to the pH 6.0 control signal are denoted with an asterisk.

Changes in external pH cause large effects on genes involved in cell wall modification

When genes were instead systematized according to their association with different compartments, the cell wall-related genes were found to constitute the group for which the external pH has the greatest impact at the transcript level. Cell wall proteins like expansins modify the plasticity and extensibility of the cell wall and are involved in both responses to biotic stress and auxin-induced cell growth (i.e. acid growth) (Cosgrove, 1999, Cosgrove, 2000, Felle, 2001).

A strong effect of acidic pH on cell wall-associated genes can be seen in the BioMaps analysis (Supplementary Table S3), especially on cell wall loosening-related genes. For example, eight expansins (out of the 34-member expansin family) were affected by an acidification of the medium pH. For detailed analyses of cell wall-related genes, the pH responsive genes were visualized using MapMan (Thimm et al., 2004). Figure 4 shows pH-responsive cell wall-related genes split into sub-categories according to their function. Medium acidification mainly affects genes encoding arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs), with 3 and 11 genes being pH-responsive after 1 and 8 h, respectively, as well as pectin esterases and genes assigned to cell wall modification (expansins, xyloglucan endotransglycosylases, pectin esterases and AGPs). Generally, after 1 hour, the majority of the pH-responsive cell wall genes are induced, while after 8 hours the majority of the pH-responsive genes are repressed. This pattern is particularly apparent among the AGPs, with 3 early pH-responsive genes (all induced) and 11 late pH-responsive genes (10 repressed). However, no overlap of responsive genes between 1 and 8 h can be detected. In a similar way, six xyloglucan:xyloglucosyl transferase genes are induced after 1 h, while after 8 h only three genes are induced and seven repressed. Among the expansins, genes annotated as α- or β-expansins (EXPA, EXPB respectively) are repressed after 1 h, while the whole group of expansin-like A (EXLA) genes (At3g45970, At4g38400, At3g45960) are induced (see Supplementary Table S2). The EXPA and EXPB response is mainly conserved between 1 h and 8 h, whereas only one EXLA gene is pH-responsive after 8 h (At3g45970). Overall, these changes in the expression of cell wall modifying enzymes appear to acclimate the wall structure to a changed growth environment, but are also linked to substantial overlap between pH- responsive genes and the transcriptional responses to pathogens and auxin, which involve major effects on these enzymes. For example, 1 h acidic pH treatment and 1 h Flg22 treatment induce the same set of three AGP genes (At5g64310, At3g61640, At2g22470), and 3 out of 6 xyloglucan:xyloglucosyl transferases that are induced by 1 h treatment at pH 4.5 are repressed by 0.5 h IAA treatment.

Figure 4.

MapMan analysis of cell wall-related pH-responsive genes. The pH-responsive genes after 1 h (A) and 8 h (B) were split into functional sub-categories with the MapMan visualization tool, where every box represents a gene in the sub-category. Induced genes are marked in red and repressed genes in blue; values are given as log2-ratios.

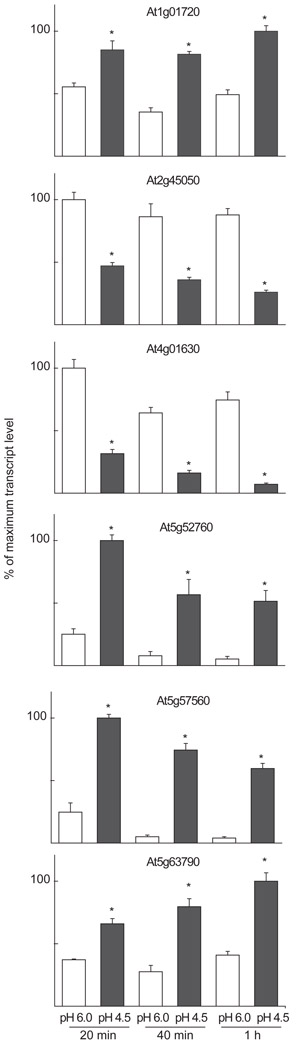

External pH changes invoke rapid transcriptional responses in roots

To study how rapidly plants can respond transcriptionally to pH changes, seedlings cultured in liquid medium were exposed to pH 4.5 or pH 6.0 for 20, 40 or 60 minutes. Roots and shoots were separated and used for transcriptional analyses of a subset of the early pH-responsive genes that had been previously identified by array analysis (Fig. 5). The selected genes were the transcription factors ANAC002/ATAF1 (At1g01720), ANAC102 (At5g63790) and GATA2 (At2g45050), the cell wall-modification genes EXPANSIN A17 (At4g01630) and TOUCH4 (At5g57560), and a gene containing a heavy-metal-associated domain motif (At5g52760). For the root samples, all six genes tested showed a significant change in transcript level, between 1.5-fold and 4-fold, after 20 minutes. After 1 hour all 6 genes showed a significant change in transcript abundance with a quantitative magnitude of at least 2-fold, as also seen in the array data for hydroponically grown roots (Supplementary Table S2). The two genes showing the strongest induced response in the seedling roots after 1 h are At5g57560 and At5g52760, with a 15- and 10-fold change, respectively (Fig. 5). This supports the hydroponic root array data (Supplementary Table S2), where At5g57560 and At5g52760 show the strongest induced pH-response. At2g45050 and At4g01630 show a reduction in transcript abundance in response to acidic pH, with a 3.5- and 10-fold down-regulation after 1 h, both in roots from seedlings, when investigated by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 5), as well as in the array data from hydroponic roots (Supplementary Table S2). The fast transcriptional response, within 20 minutes, demonstrates that plants have a rapid response system for directly sensing and responding to external pH changes. Moreover, in conjunction with data presented in Fig. 3, the results demonstrate for the 13 genes tested a consistency of the root pH-response between different plant growth systems, i.e. hydroponic growth versus seedling cultures supplemented with sucrose.

Figure 5.

The kinetics of gene expression changes in roots of A. thaliana seedlings after changes in medium pH.

The seedlings were exposed to pH 4.5 or pH 6.0 for 20, 40 or 60 minutes, and then split into roots and shoots. Transcript abundance was determined by real-time RT-PCR. The figure shows the average relative mRNA levels ± SEM for three biological replicates. For each time-point, a significant difference (T-test, P<0.05) between the pH 4.5 and pH 6.0 samples is denoted with an asterisk.

Responses to external pH are also detected in shoots

The pH-response of three of the genes tested in roots was also tested in the shoots of the liquid-cultured seedlings. In liquid culture, the shoot apoplastic fluid is in direct contact with the medium and thus the shoot tissue may be directly influenced by a medium pH change. After 1 hour of exposure to acidic pH, genes encoding the cell wall modifying enzyme TOUCH4 (At5g57560) and the transcription factor ANAC102 (At5g63790) showed significant increases (>2-fold) in transcript abundance in shoots (Fig. 6). The third gene tested, ANAC002/ATAF1 (At1g01720), did not show a significant transcriptional pH-response in shoots. The partially overlapping responses to external pH changes suggest that there is a common pH-signaling system present in both root and shoot cells, but that there are also differences regarding signaling components present.

Figure 6.

Gene expression changes in A. thaliana seedlings shoots exposed to acidification. Liquid culture-grown seedlings were exposed to pH 4.5 or pH 6.0 for 1 h and then split into roots and shoots. Transcript abundance was analyzed by real-time RT PCR. The figure shows the average relative mRNA levels ± SEM for three biological replicates. Significant differences (T-test, P<0.05) between the pH 4.5 and pH 6.0 samples are denoted with an asterisk.

Promoters of genes rapidly upregulated by acidic pH are highly enriched in elements mediating Ca2+ signaling

To identify potential cis regulatory elements that mediate changes in gene expression in response to pH, upstream sequences of early pH-responsive genes were analyzed by a non-hypothesis based methodology determining over-represented oligomers independent of previous motif assignments, using the ELEMENT program (Table III). Analysis of the early pH-induced genes showed a very strong and significant overrepresentation of sequences containing variants of the CGCG-box motif (VCGCGB). A conservation test of the promoter regions was made by analyzing the orthologs of the same gene set in papaya and poplar. Consistent with the results for Arabidopsis, 8 of the 10 oligomers that are significantly overrepresented in the upstream sequences of the orthologs in all three species contain the VCGCGB motif or CGCG core. The CGCG-box motifs are enriched in the proximal promoter regions with a maximum roughly 200 bp upstream of the translational start sites (Fig. 7A), consistent with a function in transcriptional regulation. A verification of the data was observed by searching the PLACE database of promoter motifs, where the CGCG box was found significantly overrepresented in the rapidly pH-upregulated genes. The CGCG box is recognized by the highly conserved CG-1 domain. This domain is associated with CAMTA proteins, a family of Ca2+/calmodulin binding transcription factors that has six members in A. thaliana (Doherty et al., 2009). The CGCG box motif overlaps with an abscisic acid responsive element (ABRE)-related motif (MACGYGB) that is a consensus cis-element for Ca2+-responsive genes (Kaplan et al., 2006), and which is likewise overrepresented in upstream sequences of the early pH-induced genes (Table III). The ABRE-related motif was also found to be significantly enriched in a PLACE search. Contrary to the CGCG box, which was enriched in the proximal parts of the upstream sequences (Fig. 7A), the ABRE-related motif was relatively evenly distributed over the upstream 1000 bp sequences (results not shown). To further test the observed association of the early pH responsive genes with Ca2+ and calmodulin-signaling, MapMan analysis was carried out (Thimm et al., 2004). In this analysis, 27 of the early pH-regulated genes were functionally assigned to the signaling category, and more than half of these genes were specifically associated with Ca2+ signaling (Fig. 7B).

Table III.

Overrepresentation of oligomer sequences in upstream sequences of the 211 early pH-upregulated genes

| Oligomer | Associated motif | Arabidopsis | Conservation test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene count |

Motif count |

Corrected p-value | Papaya | Poplar | ||

| AACCGCGT | CGCG box a | 17 | 17 | 8.3E-19 | + | + |

| ACGCGG | CGCG box, (ABRE-related)b | 41 | 52 | 1.1E-16 | + | + |

| ACGCG | (CGCG box), (ABRE-related) | 91 | 185 | 2.1E-17 | + | + |

| ACGCGT | CGCG box, (ABRE-related) | 38 | 92 | 2.1E-14 | + | − |

| AACGCGT | CGCG box, ABRE-related | 28 | 41 | 4.2E-14 | + | − |

| ACCGCGT | CGCG box | 21 | 23 | 8.7E-14 | + | + |

| ACGCGTTA | CGCG box, (ABRE-related) | 12 | 14 | 9.7E-14 | − | − |

| AACGCG | (CGCG box), (ABRE-related) | 52 | 69 | 4.0E-13 | + | − |

| CGCGTTA | (CGCG box) | 17 | 20 | 2.4E-08 | − | − |

| CGCGTA | (CGCG box) | 34 | 43 | 2.9E-07 | + | + |

| AAACCGCG | (CGCG box) | 12 | 12 | 7.5E-07 | − | + |

| ACGCGTA | CGCG box, (ABRE-related) | 17 | 23 | 7.9E-07 | + | − |

| AAACGCGT | CGCG box, ABRE-related | 16 | 18 | 1.3E-05 | + | + |

| CCGCGTAC | CGCG box | 3 | 3 | 1.7E-02 | + | + |

| GGTCAA | W-boxc | 102 | 135 | 2.7E-02 | + | + |

| ACGTG | ABRE-liked | 137 | 315 | 3.2E-02 | + | + |

| ACCGCGTA | CGCG box | 4 | 5 | 3.3E-02 | + | + |

The 1000 bp segments upstream of the translational start were analysed by the ELEMENT web resource for overrepresentation of oligomer sequences of 3–8 bp, using the set of 211 genes upregulated after 1h at pH 4.5. A subset is shown including all oligomers enriched, with an adjusted p-value of < 10−6, in Arabidopsis, or that had an adjusted p-value of < 0.05 for the Arabidopsis set as well as for the set of corresponding orthologs in both papaya and poplar. For oligomers partly matching a motif, yet containing the motif core, the motif name is written within parenthesis.

VCGCGB, (Yang & Poovaiah, 2002)

MACGYGB, (Kaplan et al., 2006)

(T)(T)TGAC(C/T), (Eulgem et al., 2000)

ACGTG, (Simpson et al., 2003)

Figure 7.

Ca2+-involvement in plant pH responses

A. Distribution of CGCG-box motifs in the upstream regions of genes rapidly upregulated by decreased pH.

The 1000 bp regions upstream of the translational start sites of the 100 genes most strongly upregulated by 1 h treatment at pH 4.5 are denoted as horizontal lines. The top line represents the gene with the largest fold-change after 1 h at pH 4.5, followed downwards by genes in order of induction (See Supplementary Table S2). Positions of CGCG-box (VCGCGB) motifs are denoted as black closed boxes. B. Early pH responsive genes sorted by involvement in signaling and redox, as denoted by MapMan. Every box represents a gene, where induced genes are red and repressed genes are denoted in blue. Values are given as log2-ratios.

In the ELEMENT analysis for potential upstream regulatory motifs (Table III) a conserved overrepresentation was also observed for an oligomer (ACGTG) with an ABRE-like motif, which has been shown to mediate darkness induction of ERD1 (Simpson et al., 2003). This motif overlaps with the core ABRE-related motif. Finally, the ELEMENT analyses disclosed a W-box motif for binding of WRKY transcription factors, which are involved in mediating pathogen responses (Eulgem et al., 2000). Seven transcription factors from the WRKY family are found among the early pH-responsive genes (Table II), confirming the likely involvement of WRKY factors in responses to external pH changes.

DISCUSSION

Plants possess a pH response system that can rapidly alter global patterns of gene expression

It has been long known that different plant species, including important crops, have different soil pH optima for growth (Small, 1946). Among three different ecotypes of A. thaliana grown in hydroponic media at pH 4.5–6, two ecotypes showed tolerance to the acidic pH, as measured by total plant biomass. The medium pH did have a small morphological effect on root length, but not whole plant growth of the model ecotype Columbia-0. We therefore used these conditions to determine molecular responses to changes in external pH, while avoiding detrimental stress effects. pH is highly variable in soil due to variations in elemental, organic and ionic composition, as well as water status. As a consequence, roots will upon growth and over time experience different pH environments that will affect the root surface and apoplastic pH (Gao et al., 2004). In addition, active modulation of apoplastic pH is performed by plant roots for facilitating nutrient uptake but also more generally by plant cells for inducing growth and in response to external signals (Felle, 2001). In this study, we report a rapid molecular response to decreases in the pH of the medium surrounding the root: 288 genes are differentially expressed after one hour of exposure to pH 4.5, and 6 genes tested show a corresponding change within 20 minutes. Results obtained by real-time RT-PCR for liquid culture seedlings were fully consistent with microarray analyses of hydroponically grown plants for the 1 h timepoint (Fig. 3 fig. 5). These data strongly indicate that plants have a signaling system that can rapidly sense and react to changes in the external pH, using preexisting signaling proteins to regulate gene expression. Furthermore, the massive number of pH-responsive genes (881 genes changing at least 2-fold) and the detected common responses to pH changes in the roots and the shoots from liquid cultured seedlings suggests that there are common pH-sensing components in cells of different organs, and that pH changes may be associated with general changes in cell physiology, and not exclusively root sensing of soil conditions.

The response to external pH changes is associated with Ca2+ signaling

Among bacteria and fungi several different pH-signaling pathways have been identified. These include the highly specific PacC system in A. nidulans, which only reacts on pH changes, as well as more general signaling pathways, like the two-component systems in A. tumefaciens, which integrate pH signals with other cues (Arst & Penalva, 2003, Yuan et al., 2008). When analyzing the promoter regions of the early induced pH-responsive genes in A. thaliana, a highly significant and conserved overrepresentation of the CGCG-box cis-element was found, and additionally an ABRE-related motif was significantly enriched. The CGCG-box is a target of calmodulin-binding CAMTA transcription factors (Galon et al., 2008, Yang & Poovaiah, 2002). The ABRE-related motif was identified as a consensus motif for genes responsive to Ca2+-transients induced by a calmodulin antagonist (Kaplan et al., 2006). In conjunction with our observed pH-response of Ca2+-regulated genes (Fig. 7B) this data strongly suggests that Ca2+ and calmodulin are components of an as-yet uncharacterized pH signaling system in plants.

A role for Ca2+ in pH response signaling is not without precedence in other organisms. For the fungus Candida albicans, a proper adaptation to the external pH is critical for pathogenesis. C. albicans pH-sensing pathways involve Rim101, a homolog of PacC in A. nidulans, as well as calcineurin, a protein phosphatase that is activated by Ca2+ (Kullas, Martin & Davis, 2007). The involvement of calcineurin in pH signaling has also been shown in S. cerevisiae (Platara et al., 2006). This further emphasizes the likely involvement of Ca2+ in plant pH signaling, though does not exclude a role for other types of signaling pathways, like the proteolysis-based PacC system of A. nidulans. However, we have been unsuccessful in detecting plant homologues to components of the other pH signaling pathways found in fungi and bacteria by bioinformatic analysis.

In plants, pH-sensing and Ca2+ signal induction may be mediated by proton effects on inward rectifying K+-channels. Weakly voltage dependent AKT2/3-type channels are proton-inhibited (Marten et al., 1999), whereas the KAT1-type of guard cells are stimulated by acidic pH to open at less negative membrane potentials (Blatt, 1992, Hedrich et al., 1995). The KAT1-homologue AKT1 is expressed in roots in A. thaliana and is essential for growth at low K+ concentrations in the presence of NH4+ (Ward, Mäser & Schroeder, 2009). Further, a barley root AKT1-type channel has been shown to be stimulated by apoplastic acidification (Amtmann, Jelitto & Sanders, 1999). Plasma membrane depolarization induced by K+ channel activity may in turn modulate a voltage-gated Ca2+-channel (Allen et al., 2001, Miedema et al., 2001, Miedema et al., 2008) and thus elevate the cytosolic Ca2+ levels. However, Ca2+ channels are not fully investigated in plants (Ward et al., 2009) and other hypothetical options (e.g. direct sensors) are possible.

Ca2+ plays a major role in mediating control of plant growth and development, and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses, and has been previously associated with apoplastic pH changes in several investigations. For example, mechanical stimulation of plants has been shown to trigger a Ca2+ burst in the cytoplasm of plants (Monshausen et al., 2009). In addition to the Ca2+ burst, A. thaliana seedlings responded to mechanical stimulation with rapid and substantial changes in cytoplasmic and apoplastic pH. Pretreatment with the Ca2+ channel blocker La3+ led to an inhibition of the pH changes at the cell surface, which would indicate that Ca2+ influx is both necessary and sufficient for triggering these pH changes (Monshausen et al., 2009). Further, oscillations in extracellular pH have been associated with NADPH oxidase activity during root hair tip growth, and were suggested to be driven by a Ca2+-gradient (Monshausen et al., 2007). These observations further support the likely involvement of Ca2+ in pH-signaling.

Association of pH changes to ion toxicity tolerance

Heavy metals and other toxic ions, like iron and manganese, significantly limit crop productivity in acidic soils (Kochian, Hoekenga & Pineros, 2004). Twelve genes related to metal detoxification can be found among the pH responsive genes, consistent with the idea that responses to acidic pH and heavy metals are associated (Supplementary Table S2). However, comparisons with heavy metal toxicity arrays are difficult since most available arrays are based on long-term treatments. A recent report concluded that a 6 h exposure to aluminum in roots of A. thaliana led to transcriptional changes related to oxidative stress, membrane transporters, cell wall, energy and polysaccharide metabolism (Kumari, Taylor & Deyholos, 2008). However, since the pH was changed at the same time as aluminum was added, direct comparisons to the pH response reported here cannot be made. The zinc finger protein STOP1 in A. thaliana has been shown to be involved in tolerance towards proton and aluminum toxicity, but was not pH-responsive in our microarray (Sawaki et al., 2009). By competitive array analysis (Sawaki et al., 2009), 101 genes were identified as repressed in the stop-1 mutant after 24 h aluminum treatment. When comparing these genes with our array study, 47 out of 101 genes overlap with the pH- responsive genes from the 8 h treatment. However, only few genes are in common with early pH-responsive genes, indicating that STOP1 is mainly involved in late responses to acidic pH. For constant exposure, growth inhibition by aluminum and low pH have been shown to have separate quantitative trait loci in A. thaliana (Ikka et al., 2007). Tolerance to aluminum in A. thaliana is associated with malate extrusion, including the identification of a malate exporter as a quantitative trait (Hoekenga et al., 2006, Kobayashi et al., 2007). In contrast, the pH response observed here does not associate with metabolism (e.g. the citric acid cycle and organic acid transporters). In summary, the available results suggest that even though low pH and aluminum are associated in the soil environment of the plant, both the tolerance mechanisms and the response systems of the plant to these cues are substantially separated.

Genes involved in cell wall modifications are substantially affected by external pH

The wall is the cellular compartment most directly affected by external pH. Among cell wall constituents, expansins are known as cell wall loosening proteins that are involved in acid-induced growth, and the activity of expansins is induced by lowering the cell wall pH from 7 to 4.5 (Cosgrove, 2000). Expansin superfamily genes were highly over-represented among the early pH-responsive genes in the BioMaps analysis. All responsive expansins, four alpha- and one beta-expansin (At1g20190, At5g56320, At2g20750, At4g01630, At5g02260), were downregulated in roots after 1 h at pH 4.5, and four of them remained suppressed after 8 h (Supplementary Table S2). This indicates a synchronous decrease in expression of a group of proteins in response to acidification, potentially to limit the duration of the growth phase induced by acidification, e.g. in response to auxin. Surprisingly, all three genes of the expansin-like A subfamily are strongly but transiently upregulated after 1 h at pH 4.5. This group is conserved in rice and pine, indicating a conserved function in plants, but activity has not been investigated for any of the members (Sampedro & Cosgrove, 2005).

A decrease in apoplastic pH is also likely to invoke a need for stabilization of the wall matrix structure. For example, hydroponic growth of the A. thaliana ecotype Landsberg erecta depended on the Ca2+ concentration at pH 4.5, indicating an importance of preserving cell-wall structure, especially pectin cross-linking, for growth at lower pH (Koyama, Toda & Hara, 2001). Consistent with this finding, several pectin esterase genes were found responsive to treatment at pH 4.5 in Arabidopsis. The pectin esterase genes, like most other pH-responsive cell wall modification genes, are rapidly induced (1 h), while after 8 hours the picture is the reversed with the majority of the cell wall modification genes being repressed. This can most clearly be seen among the AGPs, whose primary function likely is to act in cell wall reinforcement (Humphrey, Bonetta & Goring, 2007). Overall, this indicates an importance of wall-strength maintenance, but also suggests a separation between the short-term and long-term modifications needed for plant roots to acclimate to a decrease in apoplastic pH.

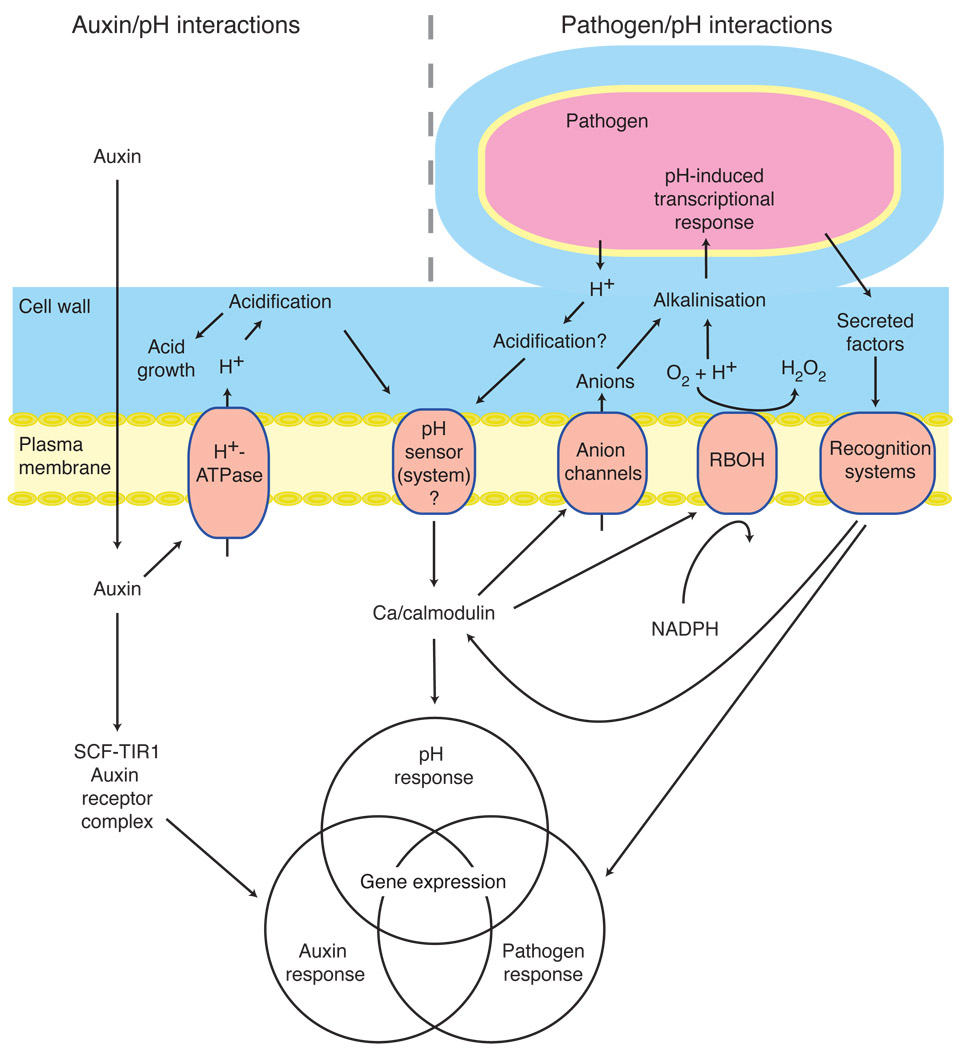

pH recognition appears to be involved in auxin and biotic stress responses

Since the pH of the apoplastic space will co-vary with changes in other cellular cues, pH signaling is likely to interact with signaling for other external factors. We previously showed that for the A. thaliana AOX2 gene, acidification of the surrounding medium acts synergistically with ammonium in transcriptional upregulation (Escobar et al., 2006). Comparisons of the acidification-induced gene regulation observed here to root ammonium responses also indicate a strong involvement of pH in ammonium-specific signaling (Patterson et al., submitted). In this investigation, the global transcriptional response to short-term acidification displayed pronounced overlaps with the responses to auxin and biotic stress. However, unlike the synergistic interaction between pH and ammonium in the regulation of AOX2 (Escobar et al., 2006), pH induction was redundant with the induction by auxin and the elicitor flagellin for several investigated genes. Auxin is well known to induce acidification of the cell wall. Similarly, long known plant responses to pathogen attack include a shift in the surface pH, driven by an intracellular Ca2+ transient, and expression of cell wall modifying enzymes. An interesting example is the interaction of barley with the root-colonizing basidiomycete Piriformospora indica and the pathogen Blumeria graminis, where rapid and slow surface acidifications and alkalinizations depend on plant cell type and the interacting fungal species (Felle et al., 2009). In the light of the potential importance of pH sensing in recognition of microorganisms, it is not surprising that we found responses to medium pH-changes to have a large overlap with biotic defense responses. Biotic stress responses depend on Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent signaling pathways and for the pH response we consistently find evidence for gene activation via a Ca2+ pathway.

Auxin generally promotes virulence in biotrophic interactions. Virulent interactions between plants and Pseudomonas syringae DC3000 or Xanthomonas oryzae induce auxin synthesis genes and repress auxin repressors and transporters (Bari & Jones, 2009). X. oryzae-induced auxin production activates the expression of expansins that result in the loosening of the cell wall and thus could potentiate pathogen growth. This is supported by the observation that expression of expansin genes was suppressed in X. oryzae-resistant rice plants that overexpress auxin-conjugating enzymes (Ding et al., 2008). Auxin response genes can be divided into three groups, encoding the AUX/IAA, GH3 and SAUR proteins. AUX/IAA proteins are repressors of auxin signaling, GH3-proteins are IAA-amido synthetases that conjugate IAA, and SAUR is a group of classical auxin response genes (Woodward & Bartel, 2005). We found 4 members of the SAUR group to be repressed by the pH-shift. These genes have also been shown to be repressed by perception of Flg22 and are therefore candidates to mediate a general auxin response suppression.

It is enticing that the transcriptional effects of external acidification substantially overlap with gene expression responses to two phenomena (auxin and biotic elicitor treatment) that are linked to apoplastic pH-shifts. Therefore it is tempting to speculate that a subset of the transcriptional responses to auxin and flagellin treatments are actually driven by pH changes, as indicated by the redundancy in the responses (Fig. 3). We suggest a model (Fig. 8), where primary cell wall acidification is not only an effect of auxin but also a signal recognized by a hypothetical pH-responsive sensor or sensor system (e.g. the combination of a pH-stimulated K+ channel and a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel). This sensor rapidly activates a Ca2+-dependent signaling pathway that mediates a part of the overall transcriptional response to auxin (Fig. 8). In an analogous way, we hypothesize that a local primary acidification (possibly an effect of the mere apposition of plant and fungal H+-ATPases across a restricted compartment) takes place at the site of a host-pathogen interaction. This acidic pH then regulates the production of virulence factors that contribute to pathogenesis (Li et al., 2002). In combination with other signals, pH sensing by the plant will integrate further information about the pathogen, affecting regulation of gene expression in the host plant. In parallel, responses to elicitors by direct protein-based signaling could induce the alkalinization of the apoplast by the plant cell, possibly mediated by anion channels and/or the RBOH plasma membrane NADPH oxidase (Felle, 2001, Torres & Dangl, 2005). Such an alkalinization can in turn be sensed by the pathogen. Several fungal and bacterial pathogens sense host-derived pH changes for determining the gene regulation pattern, for example Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and A. tumefaciens (Li et al., 2002, Rollins & Dickman, 2001).

Figure 8.

A model of the involvement of apoplastic pH in auxin and pathogen signaling. Auxin taken up into the cell will influence gene expression directly via the SCF-TIR1 receptor complex, but will also induce apoplastic acidification, which modifies the expression of a subset of auxin-affected genes. A pathogen will secrete factors that are bound by plant receptor proteins, triggering transcriptional responses and a Ca2+-mediated apoplastic alkalinization, likely by activation of anion channels and/or the RBOH NADPH oxidase. Analogous to the auxin-pH interaction, the close interaction between a plant cell and a pathogen is expected to locally acidify the cell wall, leading to a pH mediated modification of elicitor-induced pathogen responses. The plant-derived apoplastic pH changes are sensed by the pathogen, modifying its expression of virulence genes.

Overall, this study establishes external pH as an important, rapid modulator of plant gene expression that interacts with hormonal and environmental factors in integrating cellular monitoring of the extracellular compartments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I.L. and A.G.R. acknowledge support from the Swedish Research Council (623-2007-1224 and 621-2006-4597, respectively). The work was also supported by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (Gff-279-AWB) to I.L. M.A.E was supported by Award Number SC3GM084721 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. We are grateful to Per Vestergren for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Summary

The external pH that plant cells and organs experience is connected to several physiologically important factors, including nutrition, ion toxicity, cell growth, and auxin response. However, the direct effect of external pH changes on gene expression was only known for very few genes. This article demonstrates that external pH is a rapidly recognized, major affector of global gene expression in Arabidopsis roots. The expressional changes tightly link the external pH to especially auxin and pathogen responses, and provide correlational evidence for a calcium-involvement in plant pH signaling.

REFERENCES

- Allen GJ, Chu SP, Harrington CL, Schumacher K, Hoffmann T, Tang YY, Grill E, Schroeder JI. A defined range of guard cell calcium oscillation parameters encodes stomatal movements. Nature. 2001;411:1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/35082575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amtmann A, Jelitto TC, Sanders D. K+-selective inward-rectifying channels and apoplastic pH in barley roots. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:331–338. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arst HN, Penalva MA. pH regulation in Aspergillus and parallels with higher eukaryotic regulatory systems. Trends in Genetics. 2003;19:224–231. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(03)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari R, Jones JD. Role of plant hormones in plant defence responses. Plant Molecular Biology. 2009;69:473–488. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR. K+ channels of stomatal guard cells - characteristics of the inward rectifier and its control by pH. Journal of General Physiology. 1992;99:615–644. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom AJ, Frensch J, Taylor AR. Influence of inorganic nitrogen and pH on the elongation of maize seminal roots. Annals of Botany. 2006;97:867–873. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcj605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld S, Gansert D. A novel non-invasive optical method for quantitative visualization of pH dynamics in the rhizosphere of plants. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007;30:176–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes DC, Zayed AM, Ascenzi R, McCaskill AJ, Hoffman NE, Davis KR, Gorlach J. Growth stage-based phenotypic analysis of Arabidopsis: A model for high throughput functional genomics in plants. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1499–1510. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Enzymes and other agents that enhance cell wall extensibility. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1999;50:391–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Loosening of plant cell walls by expansins. Nature. 2000;407:321–326. doi: 10.1038/35030000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford NM, Forde BG. Molecular and developmental biology of inorganic nitrogen nutrition. In: Somerville CR, Meyerowitz EM, editors. The Arabidopsis book. Rockville, MD: Am. Soc. Plant Biol.; 2002. http://www.aspb.org/publications/arabidopsis/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T, Bari RP, Stitt M, Scheible WR, Udvardi MK. Real-time RT-PCR profiling of over 1400 Arabidopsis transcription factors: Unprecedented sensitivity reveals novel root- and shoot-specific genes. Plant Journal. 2004;38:366–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Cao Y, Huang L, Zhao J, Xu C, Li X, Wang S. Activation of the indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH 3–8 suppresses expansin expression and promotes salicylate- and jasmonate-independent basal immunity in rice. Plant Cell. 2008;20:228–240. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty CJ, Van Buskirk HA, Myers SJ, Thomashow MF. Roles for Arabidopsis CAMTA transcription factors in cold-regulated gene expression and freezing tolerance. Plant Cell. 2009;21:972–984. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar MA, Geisler DA, Rasmusson AG. Reorganization of the alternative pathways of the Arabidopsis respiratory chain by nitrogen supply: Opposing effects of ammonium and nitrate. Plant Journal. 2006;45:775–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends in Plant Sciences. 2000;5:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH. The apoplastic pH of the Zea mays root cortex as measured with pH-sensitive microelectrodes: Aspects of regulation. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1998;49:987–995. [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH. pH: Signal and messenger in plant cells. Plant Biology. 2001;3:577–591. [Google Scholar]

- Felle HH, Waller F, Molitor A, Kogel KH. The mycorrhiza fungus Piriformospora indica induces fast root-surface pH signaling and primes systemic alkalinization of the leaf apoplast upon powdery mildew infection. Molecular Plant Microbe Interactions. 2009;22:1179–1185. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-9-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon Y, Nave R, Boyce JM, Nachmias D, Knight MR, Fromm H. Calmodulin-binding transcription activator (CAMTA) 3 mediates biotic defense responses in Arabidopsis. FEBS Letters. 2008;582:943–948. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D, Knight MR, Trewavas AJ, Sattelmacher B, Plieth C. Self-reporting Arabidopsis expressing pH and [Ca2+] indicators unveil ion dynamics in the cytoplasm and in the apoplast under abiotic stress. Plant Physiology. 2004;134:898–908. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler DA, Johansson FI, Svensson AS, Rasmusson AG. Antimycin A treatment decreases respiratory internal rotenone-insensitive NADH oxidation capacity in potato leaves. BMC Plant Biology. 2004;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graur D, Li W-H. Fundamentals of molecular evolution. 2 ed. Sinauer Assoc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grignon C, Sentenac H. pH and ionic conditions in the apoplast. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1991;42:103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R, Moran O, Conti F, Busch H, Becker D, Gambale F, Dreyer I, Kuch A, Neuwinger K, Palme K. Inward rectifier potassium channels in plants differ from their animal counterparts in response to voltage and channel modulators. Eur Biophys J. 1995;24:107–115. doi: 10.1007/BF00211406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsinger P, Plassard C, Tang CX, Jaillard B. Origins of root-mediated pH changes in the rhizosphere and their responses to environmental constraints: A review. Plant and Soil. 2003;248:43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ho CH, Lin SH, Hu HC, Tsay YF. CHL1 functions as a nitrate sensor in plants. Cell. 2009;138:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekenga OA, Maron LG, Pineros MA, Cancado GM, Shaff J, Kobayashi Y, Ryan PR, Dong B, Delhaize E, Sasaki T, Matsumoto H, Yamamoto Y, Koyama H, Kochian LV. AtALMT1, which encodes a malate transporter, is identified as one of several genes critical for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:9738–9743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602868103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey TV, Bonetta DT, Goring DR. Sentinels at the wall: Cell wall receptors and sensors. New Phytology. 2007;176:7–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikka T, Kobayashi Y, Iuchi S, Sakurai N, Shibata D, Kobayashi M, Koyama H. Natural variation of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals that aluminum resistance and proton resistance are controlled by different genetic factors. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2007;115:709–719. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaluddin M, Zwiazek JJ. Effects of root medium pH on water transport in paper birch (Betula papyrifera) seedlings in relation to root temperature and abscisic acid treatments. Tree Physiology. 2004;24:1173–1180. doi: 10.1093/treephys/24.10.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan B, Davydov O, Knight H, Galon Y, Knight MR, Fluhr R, Fromm H. Rapid transcriptome changes induced by cytosolic Ca2+ transients reveal ABRE-related sequences as Ca2+-responsive cis elements in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2733–2748. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Hoekenga OA, Itoh H, Nakashima M, Saito S, Shaff JE, Maron LG, Pineros MA, Kochian LV, Koyama H. Characterization of AtALMT1 expression in aluminum-inducible malate release and its role for rhizotoxic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2007;145:843–852. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.102335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochian LV, Hoekenga OA, Pineros MA. How do crop plants tolerate acid soils? Mechanisms of aluminum tolerance and phosphorous efficiency. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2004;55:459–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama H, Toda T, Hara T. Brief exposure to low-pH stress causes irreversible damage to the growing root in Arabidopsis thaliana: Pectin-Ca interaction may play an important role in proton rhizotoxicity. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullas AL, Martin SJ, Davis D. Adaptation to environmental pH: Integrating the Rim101 and calcineurin signal transduction pathways. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;66:858–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M, Taylor GJ, Deyholos MK. Transcriptomic responses to aluminum stress in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2008;279:339–357. doi: 10.1007/s00438-007-0316-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Jia Y, Hou Q, Charles TC, Nester EW, Pan SQ. A global pH sensor: Agrobacterium sensor protein ChvG regulates acid-inducible genes on its two chromosomes and Ti plasmid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:12369–12374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192439499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marten I, Hoth S, Deeken R, Ache P, Ketchum KA, Hoshi T, Hedrich R. AKT3, a phloem-localized k+ channel, is blocked by protons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7581–7586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metraux JP. Recent breakthroughs in the study of salicylic acid biosynthesis. Trends in Plant Sciences. 2002;7:332–334. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedema H, Bothwell JH, Brownlee C, Davies JM. Calcium uptake by plant cells--channels and pumps acting in concert. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:514–519. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)02124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedema H, Demidchik V, Very AA, Bothwell JHF, Brownlee C, Davies JM. Two voltage-dependent calcium channels co-exist in the apical plasma membrane of Arabidopsis thaliana root hairs. New Phytologist. 2008;179:378–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra A, Tyler G. Influence of soil moisture on soil solution chemistry and concentrations of minerals in the calcicoles Phleum phleoides and Veronica spicata grown on a limestone soil. Annals of Botany. 1999;84:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Monshausen GB, Bibikova TN, Messerli MA, Shi C, Gilroy S. Oscillations in extracellular pH and reactive oxygen species modulate tip growth of Arabidopsis root hairs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:20996–21001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708586104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monshausen GB, Bibikova TN, Weisenseel MH, Gilroy S. Ca2+ regulates reactive oxygen species production and pH during mechanosensing in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2341–2356. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemhauser JL, Mockler TC, Chory J. Interdependency of brassinosteroid and auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biology. 2004;2:E258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platara M, Ruiz A, Serrano R, Palomino A, Moreno F, Arino J. The transcriptional response of the yeast Na(+)-ATPase ENA1 gene to alkaline stress involves three main signaling pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:36632–36642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins JA, Dickman MB. pH signaling in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: Identification of a pacC/RIM1 homolog. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2001;67:75–81. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.75-81.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakano K. Metabolic regulation of pH in plant cells: Role of cytoplasmic pH in defense reaction and secondary metabolism. International Reviews in Cytology. 2001;206:1–44. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)06018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro J, Cosgrove DJ. The expansin superfamily. Genome Biology. 2005;6:242. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-12-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaki Y, Iuchi S, Kobayashi Y, Kobayashi Y, Ikka T, Sakurai N, Fujita M, Shinozaki K, Shibata D, Kobayashi M, Koyama H. STOP1 regulates multiple genes that protect Arabidopsis from proton and aluminum toxicities. Plant Physiology. 2009;150:281–294. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.134700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson SD, Nakashima K, Narusaka Y, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Two different novel cis-acting elements of erd1, a clpa homologous Arabidopsis gene function in induction by dehydration stress and dark-induced senescence. Plant Journal. 2003;33:259–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small J. pH and plants. New York: D. van Nostrand Company, Inc; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville CR, Ogren WL. Mutants of the cruciferous plant Arabidopsis thaliana lacking glycine decarboxylase activity. Biochemical Journal. 1982;202:373–380. doi: 10.1042/bj2020373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson AS, Johansson FI, Møller IM, Rasmusson AG. Cold stress decreases the capacity for respiratory NADH oxidation in potato leaves. FEBS Letters. 2002;517:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson AS, Rasmusson AG. Light-dependent gene expression for proteins in the respiratory chain of potato leaves. Plant Journal. 2001;28:73–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimm O, Blasing O, Gibon Y, Nagel A, Meyer S, Kruger P, Selbig J, Muller LA, Rhee SY, Stitt M. MAPMAN: A user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant Journal. 2004;37:914–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2004.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MA, Dangl JL. Functions of the respiratory burst oxidase in biotic interactions, abiotic stress and development. Current Opinions in Plant Biology. 2005;8:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay YF, Schroeder JI, Feldmann KA, Crawford NM. The herbicide sensitivity gene CHL1 of Arabidopsis encodes a nitrate-inducible nitrate transporter. Cell. 1993;72:705–713. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90399-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JM, Mäser P, Schroeder JI. Plant ion channels: Gene families, physiology, and functional genomics analyses. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:59–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volodarsky D, Leviatan N, Otcheretianski A, Fluhr R. HORMONOMETER: A tool for discerning transcript signatures of hormone action in the Arabidopsis transcriptome. Plant Physiology. 2009;150:1796–1805. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AW, Bartel B. Auxin: Regulation, action, and interaction. Annals of Botany. 2005;95:707–735. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Poovaiah BW. A calmodulin-binding/CGCG box DNA-binding protein family involved in multiple signaling pathways in plants. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:45049–45058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan ZC, Liu P, Saenkham P, Kerr K, Nester EW. Transcriptome profiling and functional analysis of Agrobacterium tumefaciens reveals a general conserved response to acidic conditions (pH 5.5) and a complex acid-mediated signaling involved in Agrobacterium-plant interactions. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190:494–507. doi: 10.1128/JB.01387-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T, Ling HQ. Effects of pH and nitrogen forms on expression profiles of genes involved in iron homeostasis in tomato. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007;30:518–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.