Abstract

Objective To explore geographical and sociodemographic factors associated with variation in equity in access to total hip and knee replacement surgery.

Design Combining small area estimates of need and provision to explore equity in access to care.

Setting English census wards.

Subjects Patients throughout England who needed total hip or knee replacement and numbers who received surgery.

Main outcome measures Predicted rates of need (derived from the Somerset and Avon Survey of Health and English Longitudinal Study of Ageing) and provision (derived from the hospital episode statistics database). Equity rate ratios comparing rates of provision relative to need by sociodemographic, hospital, and distance variables.

Results For both operations there was an “n” shaped curve by age. Compared with people aged 50-59, those aged 60-84 got more provision relative to need, while those aged ≥85 received less total hip replacement (adjusted rate ratio 0.68, 95% confidence interval 0.65 to 0.72) and less total knee replacement (0.87, 0.82 to 0.93). Compared with women, men received more provision relative to need for total hip replacement (1.08, 1.05 to 1.10) and total knee replacement (1.31, 1.28 to 1.34). Compared with the least deprived, residents in the most deprived areas got less provision relative to need for total hip replacement (0.31, 0.30 to 0.33) and total knee replacement (0.33, 0.31 to 0.34). For total knee replacement, those in urban areas got higher provision relative to need, but for total hip replacement it was highest in villages/isolated areas. For total knee replacement, patients living in non-white areas received more provision relative to need (1.04, 1.00 to 1.07) than those in predominantly white areas, but for total hip replacement there was no effect. Adjustment for hospital characteristics did not attenuate the effects.

Conclusions There is evidence of inequity in access to total hip and total knee replacement surgery by age, sex, deprivation, rurality, and ethnicity. Adjustment for hospital and distance did not attenuate these effects. Policy makers should examine factors at the level of patients or primary care to understand the determinants of inequitable provision.

Introduction

Fairness in access to health care has been one of the founding principles of the UK National Health Service (NHS) since its inception in 1948. Theoretically, inequity in access to care should not occur because the service provided by the NHS is free to patients at the point of use, yet it is apparent that many inequities in the provision and use of health services in Britain exist.1 Health needs will not be the same across different areas of the country and will vary according to the demographic characteristics of an area.1 2 3 Local planners must assess the health needs of their populations to ensure that appropriate provision is in place, so responsibility for the planning, commissioning, and delivery of NHS services has now been shifted to primary care trusts to make services more responsive to the needs of local communities. Primary care trusts are charged with assessing the health needs of all the people in their local area, ensuring services are available to, and can be accessed by, everyone who needs them. Service planning is informed by health equity audits,4 and planners should use information on the health needs of the population to make decisions about the provision of services.5

Joint replacement is an ideal condition to study for evidence of inequity. It is a common elective procedure that makes a substantial contribution to public health, hence it is an important equity indicator. In England, during 2008-9, the National Joint Registry recorded 82 419 knee operations and 77 608 hip operations.6 Joint replacements are cost effective,7 8 with good rates of prosthesis survival,9 10 and reduce pain, increase mobility, and improve quality of life.11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 The Musculoskeletal Services Framework recognises that the needs of different people vary across different areas and that evidence of social disparity has been reported for hip and knee replacement operations, with lower rates among the most disadvantaged, despite equal or greater indications of need.19 The framework suggests that a detailed assessment of the true need for surgery is required to ensure a balanced provision of services, thus avoiding inappropriate use of resources and areas of need being deprived of resources. Fair access to joint replacement surgery is singled out in the National Strategic Framework for Older People.20

To determine whether services are provided equitably, however, it is necessary to compare patterns of service provision relative to clinical need, but this is problematic as data on the latter are not routinely available. We combined estimates of the population need for,21 22 and service provision of,23 hip and knee replacement surgery across small areas of England to determine evidence of equity in access to joint replacement across various sociodemographic groups. We explored geographical variation in equity in access to surgery and describe the extent to which hospital characteristics and distance measures explain observed inequities. The methods used are general and could be used in other countries and can also be applied to other important clinical indicators.

Methods

Data sources

The data we used to generate small area estimates of need and provision have previously been described elsewhere.21 22 23 24

English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA)

We used a two stage, cross cohort approach to identify patients in need of hip/knee replacement surgery.21 22 In the first stage we used a small area population based survey, the Somerset and Avon Survey of Health,25 26 to provide a high quality measure of need for hip/knee replacement using the New Zealand score. We analysed receiver operating characteristic curves to validate a simplified New Zealand score, excluding information from clinical examination. In the second stage we used a nationally representative population based survey (English Longitudinal Study of Ageing) to identify patients in need of hip/knee replacement using the simplified New Zealand score.

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing is a nationally representative population based survey of 11 392 people aged 50 and over living in private households in England.27 The sample was drawn from households that had previously responded to the Health Survey for England in 1998, 1999, or 2001. The Health Survey for England 1999 also included a boost sample that represented ethnic minorities. Data for this analysis were obtained from the first wave of the longitudinal study (wave 1), conducted between March 2002 and March 2003. Weights were calculated for the core sample members, and we analysed only weighted data to reduce bias from non-random non-response to make the respondent sample more representative of the population. As the health module contains information on the severity of hip/knee pain and activities of daily living, we were able to assign patients a proxy New Zealand score to identify those in need of surgery.

We fitted a fixed effects Poisson regression model in the statistical software WinBUGS to estimate rates of need for joint replacement by age, sex, deprivation, rurality, and ethnic group, including important interaction terms. Estimates from the regression model were then combined with population counts from the 2001 census to generate overall predicted rates of need in the 79 690 age-sex-ward (census area statistics) groups in England, together with estimates of uncertainty.21 22

English hospital episode statistics

The hospital episode statistics database holds information on patients admitted to NHS hospitals, either as day cases or ordinary admissions. Private procedures are excluded as there is no requirement for private hospitals to provide data. We extracted data on all primary hip and knee replacement operations in 2002 for patients aged over 50.23 To remove potential case mix issues from the sample and because of differences compared with planned elective surgery we excluded revision operations, cancers of the hip and knee bones, fracture of the hip and knee bones, injuries from trauma, such as transport crashes and falls, and non-elective admissions.

Covariates for inequity model

Sociodemographic variables—Patient level variables were age (50-59, 60-69, 70-79, 80-84, ≥85) and sex. Ecological variables were linked to the ward the patient lives in. These comprised fifths of deprivation according to the 2004 index of multiple deprivation (weighted to the ward population as each ward varies in size), rurality (urban with population of at least 10 000; town and fringe; village/isolated); ethnic mix of the area (white (≥10% white and ≤0.5% black, Asian, and other), non-white (all remaining groups)).

Hospital and distance variables—We estimated the annual volume of hip and knee replacement operations performed in each hospital in 2002 (fifths). We obtained a list of hospitals that are orthopaedic training centres from the British Orthopaedic Association website. For each hospital in 2002, the Department of Health Census of Medical and Dental Workforce provided information on total numbers of consultants, consultants in trauma and orthopaedics, and consultant anaesthetists. Department of Health KH03 and KH12 returns provided the average daily number of available and occupied beds, bed occupancy rate, and numbers of operating theatres and dedicated day case theatres. Using geographical information systems (GIS) software ArcView 3.3, we used Thiessen polygons to create catchment areas for each hospital that carried out joint replacements in 2002, allowing hospital characteristics to be expressed as rates per 100 000 catchment population. To include hospital variables in the model they need to be assigned as ward level variables. If the centroid of a ward lies in a hospital’s catchment area, we allocated the hospital’s characteristics to that ward. Geographical information systems transportation software Base TransCAD was used to calculate road travel times.

Statistical methods

A multilevel Poisson regression model was fitted to the hospital episode statistics dataset containing individuals in age-sex group i, in ward j, and in district k, to generate rates of provision of joint replacement by age, sex, deprivation, rurality, and ethnic group. We included an offset term to allow for the size of the population in each ward, age, and sex group. Extra Poisson variation was specified to allow for evidence of overdispersion that remains after adjustment for clustering. From the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing dataset we had the predicted log rate of need (standard error) in each of 79 690 age-sex-ward groups in England and linked this into the hospital episode statistics dataset.

Using the simulation environment provided by the statistical software WinBUGS (1.4.3.),28 29 we then controlled for the log rate of need in each age-sex-ward group as an additional covariate in the multilevel Poisson regression model. The model compares the log of the rate ratio of provision relative to need in each group, producing equity rate ratios by sociodemographic, hospital, and distance variables (see appendix 1 on bmj.com). We used flat non-informative priors, so the inference is dominated by the data and hence is similar to likelihood based classic methods. An equity rate ratio of 1 implies equity in access to care, while an equity rate ratio <1 suggests one group receives less provision relative to their need than another group. We used a random intercepts multilevel model to control for evidence of clustering in the data by allowing the overall rate of provision relative to need to vary across wards and districts.

We began by fitting a multivariable model including the sociodemographic variables alone, testing for evidence of important interactions. We then looked at the effect of hospital and distance variables by fitting a full model including all variables and using backwards selection to exclude variables that did not improve model fit. Random slopes models were then individually fitted for each sociodemographic variable to see if their effects varied across districts. We produced overall rates of equity (provision relative to need) for each of the 354 districts in England, together with estimates of uncertainty.

Results

For total hip and knee replacement we observed an “n” shaped curve by age. Compared with people aged 50-59, those aged 60-84 received greater provision relative to need, but those aged ≥85 got less (tables 1 and 2). Men received 8% more hip replacements relative to need than women (and 31% more knee replacements). People living in the most deprived areas received around 70% less provision relative to need compared with people in the least deprived areas for both hip and knee replacement. Those in urban areas got greater provision of knee replacement relative to need. The effect was different for hip replacement, with people in village/isolated areas getting the most provision relative to need and those in town/fringe areas the least. Ethnic mix of the area had no effect on hip replacement, but for knee replacement people in non-white areas received higher provision relative to need compared with those in predominantly white areas.

Table 1.

Equity rate ratios for access to care to hip replacement. Figures are adjusted rate ratios (95% confidence intervals)

| Sociodemographic model | Full model | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Age group (years): | ||

| 50-59 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 60-69 | 2.78 (2.69 to 2.87) | 2.78 (2.69 to 2.87) |

| 70-79 | 2.43 (2.35 to 2.51) | 2.43 (2.35 to 2.51) |

| 80-84 | 1.64 (1.57 to 1.71) | 1.64 (1.57 to 1.71) |

| ≥85 | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.72) | 0.68 (0.65 to 0.72) |

| P linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sex: | ||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.10) | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.10) |

| Index of multiple deprivation 2004*: | ||

| 1 (least deprived) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.76) | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.76) |

| 3 | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.57) | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.57) |

| 4 | 0.43 (0.42 to 0.45) | 0.44 (0.42 to 0.46) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 0.30 (0.29 to 0.32) | 0.31 (0.30 to 0.33) |

| P linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Ethnic mix of area: | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-white | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.04) |

| Rurality: | ||

| Urban (≥10 000) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Town and fringe | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.98) |

| Village/isolated | 1.19 (1.15 to 1.24) | 1.16 (1.12 to 1.22) |

| P linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Hospital trust characteristics | ||

| No of hip operations/year/hospital trust*: | ||

| 1 (1-234) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (238-308) | NA | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.17) |

| 3 (310-389) | NA | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.14) |

| 4 (396-564) | NA | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.15) |

| 5 (570-1076) | NA | 1.13 (1.06 to 1.20) |

| P linear trend | — | 0.001 |

| Orthopaedic training centre status: | ||

| No | NA | 1.00 |

| Yes | NA | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.09) |

| Rate of all consultants per 100 000*: | ||

| 1 (4.18-29.95) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (30.15-34.27) | NA | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.95) |

| 3 (34.35-38.09) | NA | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.97) |

| 4 (38.98-46.07) | NA | 0.86 (0.81 to 0.92) |

| 5 (46.15-550.18) | NA | 0.80 (0.74 to 0.86) |

| P linear trend | — | <0.001 |

| Rate of trauma and orthopaedic consultants per 100 000*: | ||

| 1 (1.35-2.05) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (2.06-2.41) | NA | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.07) |

| 3 (2.41-2.75) | NA | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.14) |

| 4 (2.76-3.11) | NA | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.07) |

| 5 (3.11-13.72) | NA | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.14) |

| P linear trend | — | 0.008 |

| Rate of operating theatres per 100 000*: | ||

| 1 (0.00-3.62) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (3.63-4.46) | NA | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.10) |

| 3 (4.50-5.03) | NA | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) |

| 4 (5.07-5.97) | NA | 1.10 (1.03 to 1.17) |

| 5 (6.08-42.42) | NA | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.19) |

| P linear trend | — | 0.002 |

| Measures of distance to hospital (road travel times in minutes)*: | ||

| 1 (1.79-12.85) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (12.86-20.07) | NA | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.06) |

| 3 (20.08-30.10) | NA | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) |

| 4 (30.11-45.89) | NA | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16) |

| 5 (45.91-225.76) | NA | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.17) |

| P linear trend | — | <0.001 |

NA=variable not included in multivariable model.

*Fifths of distribution.

Table 2.

Equity rate ratios for access to care to knee replacement. Figures are adjusted rate ratios (95% confidence intervals)

| Sociodemographic model | Full model | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Age group (years): | ||

| 50-59 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 60-69 | 3.73 (3.59 to 3.87) | 3.73 (3.59 to 3.88) |

| 70-79 | 4.25 (4.09 to 4.40) | 4.25 (4.08 to 4.41) |

| 80-84 | 2.65 (2.53 to 2.77) | 2.65 (2.53 to 2.78) |

| ≥85 | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.93) | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.93) |

| P linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sex: | ||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 1.31 (1.28 to 1.34) | 1.31 (1.28 to 1.34) |

| Index of multiple deprivation 2004*: | ||

| 1 (least deprived) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 0.75 (0.72 to 0.77) | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.77) |

| 3 | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.68) | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.68) |

| 4 | 0.43 (0.41 to 0.45) | 0.43 (0.41 to 0.45) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 0.32 (0.31 to 0.34) | 0.33 (0.31 to 0.34) |

| P linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Ethnic mix of area: | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-white | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.07) |

| Rurality: | ||

| Urban ≥10 000 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Town and fringe | 0.77 (0.73 to 0.80) | 0.76 (0.73 to 0.79) |

| Village/isolated | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.97) | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.96) |

| P linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Hospital trust characteristics | ||

| No of knee operations/year/hospital trust*: | ||

| 1 (30-204) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (205-263) | NA | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.13) |

| 3 (264-345) | NA | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) |

| 4 (352-495) | NA | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.19) |

| 5 (503-803) | NA | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.15) |

| P linear trend | — | <0.001 |

| Orthopaedic training centre status: | ||

| No | NA | 1.00 |

| Yes | NA | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) |

| Rate of all consultants per 100 000*: | ||

| 1 (4.36-30.02) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (30.43-35.35) | NA | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) |

| 3 (35.77-38.79) | NA | 0.94 (0.88 to 0.99) |

| 4 (39.04-47.48) | NA | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.93) |

| 5 (47.50-447.69) | NA | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.97) |

| P linear trend | — | <0.001 |

| Rate of trauma and orthopaedic consultants per 100 000*: | ||

| 1 (1.31-2.12) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (2.14-2.49) | NA | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.01) |

| 3 (2.50-2.73) | NA | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.08) |

| 4 (2.76-3.09) | NA | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) |

| 5 (3.09-11.17) | NA | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) |

| P linear trend | — | 0.012 |

| Rate of dedicated day case theatres per 100 000*: | ||

| 1 (0.00-0.42) | NA | 1.00 |

| 2 (0.42-0.67) | NA | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) |

| 3 (0.68-1.02) | NA | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.10) |

| 4 (1.03-1.40) | NA | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) |

| 5 (1.40-3.84) | NA | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.19) |

| P linear trend | — | 0.006 |

NA=variable not included in multivariable model.

*Fifths of distribution.

Inclusion of hospital and distance variables did not attenuate the pattern of inequities observed in different sociodemographic groups. Some variables were associated with overall rates of inequity. For hip and knee replacement, higher surgical volumes, orthopaedic training centre status, greater numbers of trauma and orthopaedic consultants, and fewer overall consultants were associated with greater provision relative to need. For hip replacement, more operating theatres and longer road travel times were associated with greater provision relative to need; as were, for knee replacement, more dedicated day case theatres.

We found evidence of important interactions (see appendices 2 and 3 on bmj.com). For example, for knee replacement there was an interaction between sex and deprivation, whereby the effect of men receiving greater provision relative to need than women was strongest in the least deprived areas and weakest in the most deprived areas.

Geographical variation

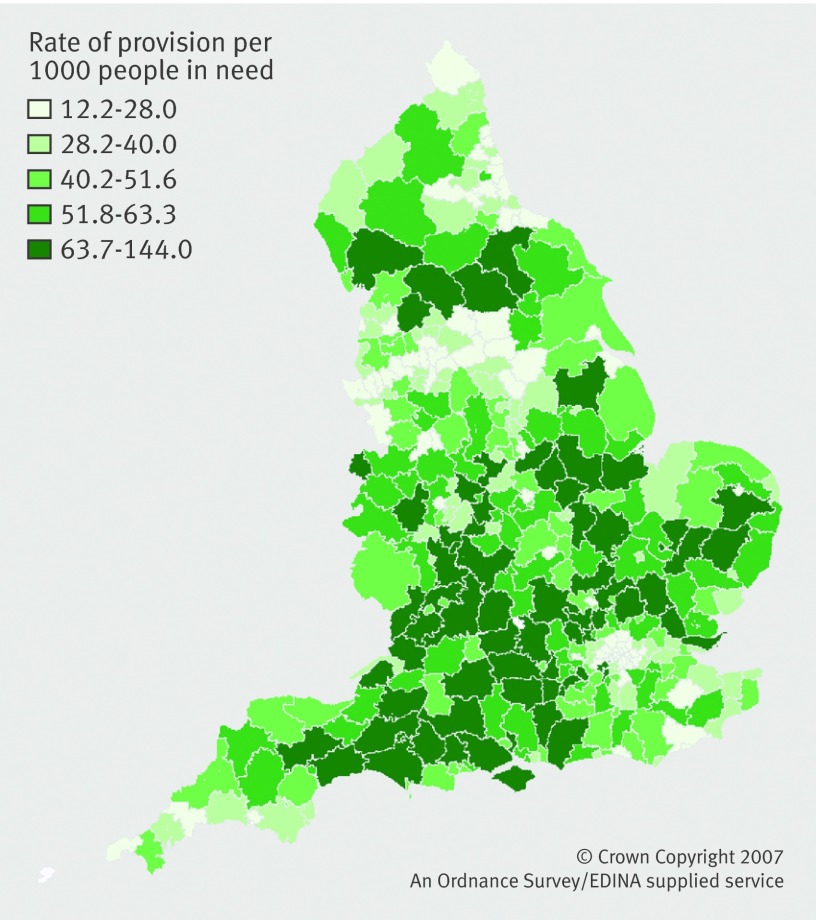

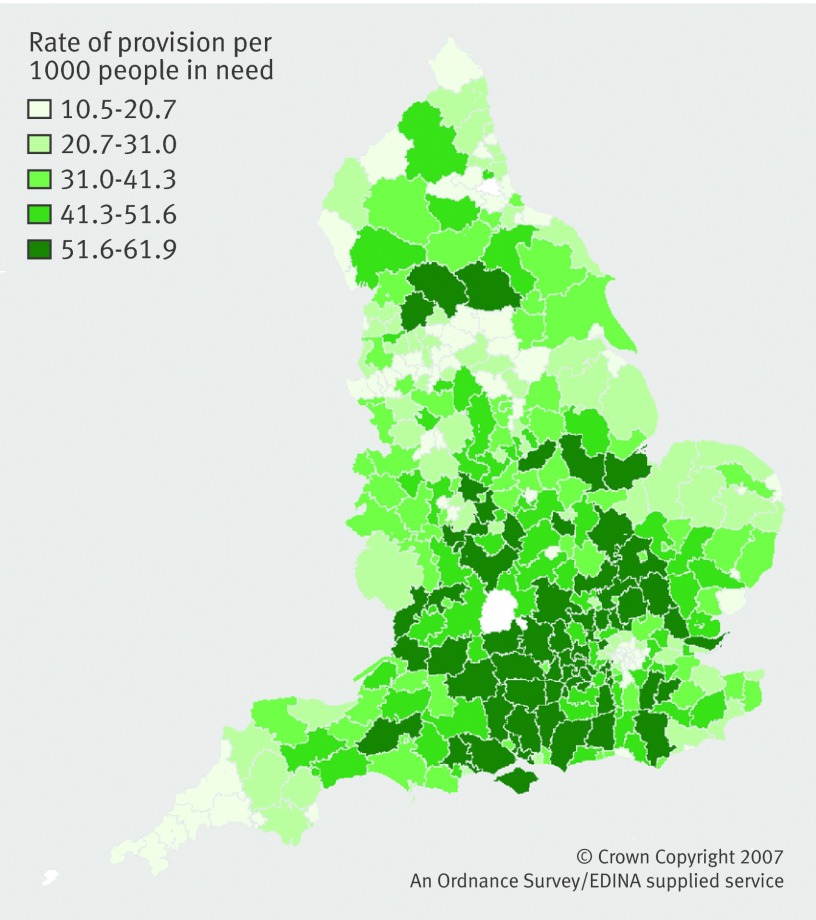

Previously we produced maps displaying rates of need and provision of hip and knee replacement across the 354 districts in England.22 23 Visually comparing the maps of rates of need and provision by district suggests potential geographical variation in equity in access to care. Some districts with high rates of need get low rates of provision, some districts with low rates of need get high provision, and in some districts rates of need reflect provision. This is confirmed when we combined our data comparing rates of provision relative to need to produce equity rate ratios. There is evidence that the overall rate of provision relative to need (equity) varies geographically across England depending on the sociodemographic characteristics of an area. We found evidence of additional geographical variation over and above that explained by the variables in the regression model. For hip replacement the overall rate of equity was 44.2/1000, which implies that for every 1000 people in need of surgery 44 will receive an operation (30.9/1000 for knee replacement).

We predicted the overall rate of equity in access to hip and knee replacement for each district in England (fig 1 and fig 2) adjusted for sociodemographic, hospital, and distance variables, together with estimates of uncertainty. A district with a high rate of equity (dark green) is providing more operations for people in need than a district with a low rate of equity (light green). On average, a district in the bottom fifth would have to perform an additional 24 hip replacement operations per 1000 people in need (13/1000 for knee replacement) to move from the bottom to middle fifth. For hip and knee replacement the level of equity is worse for people living in the north, the West Midlands, and London. People living in the south of England fare best (with the exception of London), where those in need of surgery are more likely to get an operation than in other areas of the country. Table 3shows the top 10 districts with the highest and lowest rates of equity.

Fig 1 Map of equity in access to total hip replacement across 354 districts in England

Fig 2 Map of equity in access to total knee replacement across 354 districts in England

Table 3.

Overall rate of provision per 1000 people in need (equity), adjusted for sociodemographic, hospital, and distance variables. Ten lowest and highest rates

| District | Adjusted rate per 1000 people in need (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Ten lowest | |

| Hip replacement | |

| Tower Hamlets (00BG) | 12.2 (8.1 to 18.1) |

| Stoke-on-Trent (00GL) | 12.4 (9.0 to 17.1) |

| Hackney (00AM) | 12.5 (8.3 to 18.3) |

| Leicester (00FN) | 13.2 (9.5 to 18.2) |

| Newham (00BB) | 14.6 (10.0 to 21.1) |

| Doncaster (00CE) | 14.9 (11.1 to 19.7) |

| Camden (00AG) | 16.0 (10.8 to 23.3) |

| Waltham Forest (00BH) | 16.1 (11.2 to 22.7) |

| Greenwich (00AL) | 17.1 (12.0 to 24.0) |

| Manchester (00BN) | 17.2 (13.05 to 22.4) |

| Knee replacement | |

| Stoke-on-Trent (00GL) | 10.5 (8.7 to 12.5) |

| Penwith (15UF) | 12.6 (9.9 to 15.9) |

| Hackney (00AM) | 12.9 (10.5 to 15.7) |

| Manchester (00BN) | 14.0 (12.2 to 16.1) |

| Newham (00BB) | 14.1 (11.7 to 17.0) |

| Liverpool (00BY) | 14.6 (12.8 to 16.6) |

| Islington (00AU) | 14.7 (12.1 to 17.9) |

| Tower Hamlets (00BG) | 14.8 (12.1 to 18.1) |

| Doncaster (00CE) | 14.8 (12.7 to 17.3) |

| Wakefield (00DB) | 15.0 (12.8 to 17.5) |

| Ten highest | |

| Hip replacement | |

| Wokingham (00MF) | 91.4 (65.2 to 127.2) |

| West Berkshire (00MB) | 92.9 (62.2 to 138.5) |

| Bromsgrove (47UB) | 97.2 (69.3 to 136.2) |

| St Albans (26UG) | 97.6 (70.0 to 136.2) |

| Aylesbury Vale (11UB) | 100.9 (72.7 to 139.6) |

| Huntingdonshire (12UE) | 105.0 (77.9 to 140.9) |

| Tewkesbury (23UG) | 110.6 (77.9 to 154.9) |

| Harrogate (36UD) | 117.8 (89.4 to 154.1) |

| South Somerset (40UD) | 128.0 (99.3 to 163.8) |

| West Oxfordshire (38UF) | 144.0 (83.7 to 249.1) |

| Hip replacement | |

| Aylesbury Vale (11UB) | 53.1 (44.2 to 63.2) |

| East Hertfordshire (26UD) | 53.1 (43.9 to 63.9) |

| Surrey Heath (43UJ) | 54.2 (43.7 to 67.4) |

| Wokingham (00MF) | 54.4 (45.0 to 65.6) |

| Woking (43UM) | 54.6 (44.3 to 67.0) |

| Runnymede (43UG) | 55.9 (45.3 to 68.3) |

| Basingstoke and Deane (24UB) | 56.6 (47.6 to 67.0) |

| Hart (24UG) | 57.4 (46.1 to 71.2) |

| Spelthorne (43UH) | 60.0 (49.6 to 72.1) |

| Epsom and Ewell (43UC) | 61.9 (50.2 to 76.2) |

We found evidence that the pattern of equity by sociodemographic group varies geographically across districts (see appendices 4 and 5 on bmj.com). For example, for knee replacement in Manchester there was no evidence of sex inequity (rate ratio 1.02, 95% confidence interval 0.82 to 1.27), while in Stratford-on-Avon men got greater provision relative to need compared with women (1.67, 1.31 to 2.13).

Sensitivity analyses

To identify whether or not a person is in need of joint replacement surgery in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing dataset, we used the New Zealand score out of 80, with a cut off of 48.21 We conducted a sensitivity analysis, repeating the analyses to generate small area predictions in each district of England using both higher and lower choices of threshold (43 and 53, respectively).22 Although the overall rate of need for hip and knee replacement surgery differed depending on the cut off used, the geographical pattern remained unchanged. Regardless of the choice of threshold, the same districts were identified as having high or low rates of need.

Discussion

Main findings

This study provides evidence of geographical variation in equity in access to hip and knee replacement in England by sociodemographic group. We combined two different sources of routine data into a single statistical model to explore inequity. The advantage of this approach is that it allows the analyses to be reproduced in the future with updated estimates of provision as part of a continual cycle of equity audit.

The overall rate of equity we described seems low (44.2/1000 for hip replacement, 30.9/1000 knee replacement), suggesting substantial underprovision of surgery. The rates are somewhat arbitrary, as different treatment thresholds will either increase or decrease these values, but do not invalidate relative comparisons. Our estimates, however, fit with those of other studies estimating rates of need25 26 30 31 32 33 and provision of joint replacement.34 35 36 37 We previously described an overall rate of need of 31.6/1000 for hip replacement and 41.4/1000 for knee replacement, while our estimated rates of provision were 199.1/100 000 and 188.1/100 000, respectively. In some part this underprovision is caused by a lack of data from the private sector (20% of joint operations are carried out in private institutions38). In addition, our data on surgical provision are from 2002 and the numbers of joint replacement operations performed annually has increased substantially since then.6 We were also unable to adjust our estimates of need to exclude patients who are unwilling to undergo surgery or are not suitable clinical candidates. In the Somerset and Avon Survey for Health adjustment for willingness for surgery led to a 9% reduction in the estimated need for hip replacement26 (and a 36% reduction for knee replacement25). Adjustment for such factors would help us to understand why the observed inequities exist, but data are not available from the private sector, we have no information on willingness, and although data on comorbidities are available it is unclear what would make a patient an unsuitable candidate for surgery given improvements in modern anaesthesia, surgical techniques, and prosthesis survival.

Findings in context

Consistent with our findings, previous research suggests that older people have a greater need of hip and knee replacement but are less likely to receive care.30 31 32 33 39 A Canadian study found that compared with those aged ≤62, people aged 63-81 were more likely, and those aged ≥82 years less likely, to undergo joint surgery.40 This fits the “n” shaped curves we observed. Adjustment for willingness did not attenuate this effect. Other studies in England have also found evidence of inequity favouring men,32 33 but a Canadian study found no evidence that sex was associated with time to receipt of joint replacement.40 Others have found that those in more deprived areas or of lower social class, education, or wealth have greater need of joint replacement but receive less or equal provision.32 33 39 41 This again is consistent with our findings. The Canadian study found education was a strong predictor of receipt of joint replacement, but adjustment for patients’ willingness removed this effect.40 Our findings by rurality are not consistent with those of the Wiltshire and Sheffield study, which found no evidence of such inequity,32 33 but this might simply reflect local factors. Studies identifying people with hip and knee disease in the general population found that white people were more likely than black people to see an orthopaedic surgeon,42 and African Americans were less likely than white people to get knee replacement.43 A Canadian study found that race was not associated with time to receipt of knee replacement but studied a predominantly white sample.40

The data support the growing body of research showing evidence of inequity in access to health care,44 notably in other specialties such as cardiology, where older patients and women are less likely to be referred for coronary artery bypass grafting, exercise testing, and cardiac catheterisation.45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 In the treatment of heart disease, people living in more deprived areas have less access to services.50 55 56 57 58 59 Patients in lower socioeconomic groups are less likely to be investigated once the disease develops and are less likely to be referred for cardiac surgery thereafter. South Asians are less likely to receive revascularisation, independent of clinical need and social class.60 In the US white people are more likely than black people to receive revascularisation procedures after coronary angiography.61

Limitations

Strengths and limitations of the routine data sources used for this analysis are described elsewhere.21 22 23 24 One strength of our study is the two stage cross cohort approach used to identify patients in need of surgery. The advantage of small area population based studies is that they are specifically designed to estimate the population requirement for joint replacement surgery and have a high quality measure of need that is confirmed radiographically and through clinical examination. Small area studies, however, are limited in terms of their generalisability. On the other hand, large nationally representative population surveys are more generalisable but are often not designed to examine a specific health problem and rarely have detailed clinical data or radiography results, or both. By using a two stage cross cohort approach we combined the strengths of these two study designs. A limitation of hospital episode statistics is the lack of individual data. Information on social class or obesity are unavailable, and ethnicity is incompletely recorded. To overcome this we used ecological variables of deprivation, rurality, and ethnicity, hence ecological bias might be present. Concerns have been raised over the completeness and accuracy of data collected for administrative rather than research purposes, and importantly it might contain incomplete or inaccurate diagnostic and operation coding, though joint replacement procedures seem to be well coded (97-100% accuracy).62 63 64 We modelled rates of provision and need during the same time period. While we think that the level of need is unlikely to change acutely, rates of provision are more liable to change, though this would probably affect the absolute rates rather than relative levels of provision. Future work could model in lag times to allow for any latency periods.

One major limitation is the lack of data on provision from the private sector, and anecdotally it has been suggested that this could explain low rates of provision in London, where up to 30% of patients go private, leading to an overestimate of unmet need in this area. Putting this into the context of our overall findings, however, we found evidence of a strong gradient for deprivation where people in affluent areas have the highest provision relative to need. Attempting to incorporate data on provision from the private sector would probably strengthen this further so that we are probably underestimating the area deprivation effect in this study. In addition, we estimated the effect of deprivation for each district in England (see appendices 4 and 5 on bmj.com), and the pattern we observed is consistent across all districts including those in London. Use of data on provision from the National Joint Registry would help to overcome this limitation as they include information from both private and public sectors.

The main problem lies in trying to identify where and why the inequities occur in the care pathway. The purpose of Health Equity Audit is to first identify whether inequities occur. If inequities exist, interventions are required to tackle the problem; the cycle being repeated to see whether interventions were effective. One strength of our analysis is that we were able to consider whether hospital variables explained observed inequities but found no evidence they were important, suggesting causes of inequity might lie further down the care pathway, at the level of the patient, general practitioner, or consultant. The advantage of small area one-off studies designed specifically to estimate need for joint replacement is consideration of the extent to which patients’ willingness and fitness for surgery attenuate observed inequities. We were unable to do this, though the literature highlights how patients’ willingness and physician bias might explain observed inequities.

Older people are less willing to seek or want joint replacement.25 40 43 65 66 67 68 Because the symptoms of arthritis get progressively worse over time, older people consider it a normal part of ageing,69 70 adapting their lifestyles to cope and not considering surgery as an option.71 72 73 In younger people, the impact on work and social lives is greater so they seek surgery to get back to normal.25 67 69 73 74 Older people want to be perceived as ageing well; seeking help means losing their “healthy” status.70 72 74 They are more stoical and have led harder lives, remembering a time before the NHS existed and making them reluctant to use health care.69 70 72 74 It is important for policy makers to consider that the next generation of older people might be more demanding and have greater expectations of their right to surgery. This cause of age inequity might resolve itself in years to come without the need for intervention but will bring with it greater demand for surgery. Studies controlling for patients’ willingness found that age inequities remained, suggesting that once patients see a general practitioner or orthopaedic surgeon further barriers exist.40 Older patients might find that some general practitioners confirm symptoms as an inevitable part of ageing and say that nothing can be done.69 73 74 Some do not believe that older people are suitable candidates for surgery and think that it would not be successful if offered, with poor outcomes, particularly for knee replacement.25 69 72 Conversely younger people also find themselves discriminated against by some general practitioners, who think they are too young for an operation and should wait until they are older.73

Women might be less willing to have joint surgery25 43 (some suggest equally willing65 66 67), as are people of lower socioeconomic status67 and African Americans.42 The common explanation being that these groups are less positive about the benefits and outcomes of surgery, being largely influenced by friends and family and those they know who had surgery.69 71 72 The decision to have surgery is based on advice from friends and family and experiences of others, rather than opinions of health professionals. Physicians are more likely to refer men than women for knee replacement.75

Studies in heart disease support the view that older patients, women, and those from deprived areas are less likely to opt for surgical intervention and seek access to care45 46 47 76 77 and doctors are less likely to refer elderly patients and women.45 47 In addition, they provide further insight as to the reasons why patients are less willing to access care and causes of physician bias, but it is unclear whether the reasons why people are unwilling to seek access to care for a life threatening disease such as heart disease would apply to joint replacement, which has the aim of improving quality of life by reducing levels of pain and disability.

Older people and women are less likely than younger people to prefer surgery, mainly because of the impact of treatment on their personal lives.46 Qualitative studies in relation to chest pain suggest that women are more reluctant to consult their partners, not wanting to worry them, instead relying on the advice of friends, which did not lead to seeking health care.77 Women were reluctant to report pain for fear of being told off for unhealthy behaviours (smoking, overweight) and feared wasting doctors’ time. Such themes are common in people seen for joint replacement surgery. People in deprived areas were more stoical about getting heart disease because of a strong family history of disease and knowing people at risk of or with the disease.76 They normalised their chest pain, had other important medical conditions, expressed concerns about overusing medical services, and were less able to distinguish it from other physical conditions, such as chest infections, heartburn, and stress. They were more likely to report negative experiences of health care (negative perceptions of the benefits and outcomes of surgery) and to have lower expectations of health care. Such themes are common in joint replacement surgery and could explain why those of lower social class are less willing to consider surgery. Patients are aware of the common risk factors for heart disease such as smoking and obesity, but poorer individuals were more likely to feel guilty for their chest pain and believe that their general practitioners would blame them for their health problems, hence acting as a deterrent to healthcare seeking behaviour. The idea of blame is apparent in literature on joint replacement. As joint disease is more common in people with manual occupations, this could be a further explanation why people in more deprived areas are less willing to seek care for joint replacement. People from more affluent areas were more likely to have greater medical knowledge and have informed discussions with general practitioners, with some reporting privileged access to health care through connections and friends in the medical profession.76

Conclusion

In this study we have developed a novel methodological approach combining small area estimates on the need for and surgical provision of hip and knee replacement surgery to explore evidence of inequity in access to care. The method described here is general and can be applied to other important equity indicators. Hospital provider characteristics did not explain the observed inequities by age, sex, deprivation, rurality, and ethnic group, suggesting causes of inequity might lie further down the care pathway at the level of the patient, general practitioner, or consultant. Further research is required to enable the design of interventions that could ameliorate these patterns.

What is already known on this topic

Joint replacement is a common elective procedure that makes a substantial contribution to public health, hence is an important equity indicator

Local health planners are required to conduct health equity audits and need information on small area estimates of both the need for and provision of joint replacement surgery to provide services equitably

What this study adds

Analysis of combined sources of routine data in a single statistical model showed evidence of underprovision of hip and knee replacement relative to need in England

There is evidence of inequity by age, sex, deprivation, rurality, and ethnicity, and this varied by geography; hospital and distance variables did not explain evidence of inequities observed

The Hospital Episode Statistics data were made available by the Department of Health. Hospital Episode Statistics analyses conducted within the Department of Social Medicine are supported by the South West Public Health Observatory. English Longitudinal Study of Ageing data were made available through the UK Data Archive (UKDA). The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing was developed by a team of researchers based at the National Centre for Social Research, University College London and the Institute for Fiscal Studies. The data were collected by the National Centre for Social Research. The funding is provided by the National Institute of Aging in the United States, and a consortium of UK government departments coordinated by the Office for National Statistics. The developers and funders of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing and the Archive do not bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. This work is based on data provided through EDINA UKBorders with support from the ESRC and JISC and used material that is copyright of the Crown.

We thank Mary Shaw at the Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, for support and advice throughout the project, Richard Harris for help and advice with Geographical Information Systems software, and Kelvyn Jones for statistical advice on multilevel modelling, both from the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol.

Contributors: AJ, JS, and YBS had the original idea for the study. AJ wrote the first draft and incorporated comments from all authors. AJ performed all statistical analyses with guidance and support of NJW. All authors contributed to the interpretation and writing of the paper. AJ is guarantor.

Funding: This study was part of a PhD studentship, funded by the Medical Research Council/Health Services Research Collaboration at the Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol. The work is part of a wider programme by JS on measuring and monitoring inequalities in health care. JS received funding from a National Coordinating Centre for Research Capacity Development (NCCRCD) Department of Health (DH) Public Health Initiative 2003. NJW is funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC). AJ acknowledges support from the National Institute for Health research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Unit (BRU) Musculoskeletal Research Group, University of Oxford. The opinions expressed by the authors are theirs alone and do not represent the opinions of supporting organisations.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: all authors had financial support from the Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c4092

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1 Technical details of model

Appendix 2 Hip interaction plots

Appendix 3 Knee interaction plots

Appendix 4 Geographical variation in pattern of equity in access to hip replacement in different sociodemographic groups across districts in England

Appendix 5 Geographical variation in pattern of equity in access to knee replacement in different sociodemographic groups across districts in England

References

- 1.Department of Health. On the state of the public health: annual report of the Chief Medical Officer 2005. DH, 2006.

- 2.British Medical Association. Healthcare funding review. BMA, 2002.

- 3.Department of Health. Building on the best: choice, responsiveness and equity in the NHS. DH, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Department of Health. Tackling health inequalities: status report on the Programme for Action—2006 update on headline indicators. DH 2006.

- 5.Department of Health. Health equity audit. A self-assessment tool. DH, 2004.

- 6.National Joint Registry. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 6th annual report. National Joint Registry, 2009.

- 7.Chang RW, Pellisier JM, Hazen GB. A cost-effectiveness analysis of total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the hip. JAMA 1996;275:858-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang MH, Cullen KE, Larson MG, Thompson MS, Schwartz JA, Fossel AH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total joint arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:937-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rand JA, Ilstrup DM. Survivorship analysis of total knee arthroplasty. Cumulative rates of survival of 9200 total knee arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991;73:397-409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scuderi GR, Insall JN, Windsor RE, Moran MC. Survivorship of cemented knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1989;71-B:798-803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kirwan JR, Currey HL, Freeman MA, Snow S, Young PJ. Overall long-term impact of total hip and knee joint replacement surgery on patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1994;33:357-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawker G, Wright J, Coyte P, Paul J, Dittus R, Croxford R, et al. Health-related quality of life after knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80:163-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, Dittus RS. Patient outcomes following unicompartmental or bicompartmental knee arthroplasty. A meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 1995;10:141-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, Dittus RS. Patient outcomes following tricompartmental total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. JAMA 1994;271:1349-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams MH, Frankel SJ, Nanchahl K, Coast J, Donovan JL. Total hip replacement. In: Stevens A, Raftery J, eds. Health care needs assessment: the epidemiological based needs assessment review. Vol 1. Radcliffe Medical Press, 1994.

- 16.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Effective health care bulletin: total hip replacement. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 1996.

- 17.Walker DJ, Heslop PS, Chandler C, Pinder IM. Measured ambulation and self-reported health status following total joint replacement for the osteoarthritic knee. Rheumatology 2002;41:755-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMurray A, Grant S, Griffiths S, Letford A. Health-related quality of life and health service use following total hip replacement surgery. J Adv Nurs 2002;40:663-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health. The musculoskeletal services framework. A joint responsibility ng it differently. DH, 2006.

- 20.Department of Health. National service framework for older people. DH, 2001.

- 21.Judge A, Welton NJ, Sandhu J, Ben-Shlomo Y. Modeling the need for hip and knee replacement surgery. Part 1. A two-stage cross-cohort approach. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1657-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judge A, Welton NJ, Sandhu J, Ben-Shlomo Y. Modeling the need for hip and knee replacement surgery. Part 2. Incorporating census data to provide small-area predictions for need with uncertainty bounds. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1667-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judge A, Welton NJ, Sandhu J, Ben-Shlomo Y. Geographical variation in the provision of elective primary hip and knee replacement: the role of socio-demographic, hospital and distance variables. J Public Health 2009;31:413-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Judge AD. Developing methods to investigate equity in access to healthcare using routine data sources: a case study using total joint replacement of the hip and knee [PhD thesis]. Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, 2008.

- 25.Juni P, Dieppe P, Donovan J, Peters T, Eachus J, Pearson N, et al. Population requirement for primary knee replacement surgery: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatology 2003;42:516-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frankel S, Eachus J, Pearson N, Greenwood R, Chan P, Peters TJ, et al. Population requirement for primary hip-replacement surgery: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 1999;353:1304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marmot M, Banks J, Blundell R, Erens B, Lessof C, Nazroo J, et al. English longitudinal study of ageing: wave 0 (1998, 1999 and 2001) and waves 1-3 (2002-2007) [computer file]. 10th ed. UK Data Archive, 2008.

- 28.Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N, Spiegelhalter D. WinBUGS—a Bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput 2000;10:325-37. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiegelhalter DJ, Thomas A, Best N, Lunn D. WinBUGS user manual: version 1.4. MRC Biostatistics Unit, 2001.

- 30.Fear J, Hillman M, Chamberlain MA, Tennant A. Prevalence of hip problems in the population aged 55 years and over: access to specialist care and future demand for hip arthroplasty. Br J Rheumatol 1997;36:74-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tennant A, Fear J, Pickering A, Hillman M, Cutts A, Chamberlain MA. Prevalence of knee problems in the population aged 55 years and over: identifying the need for knee arthroplasty. BMJ 1995;310:1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milner PC, Payne JN, Stanfield RC, Lewis PA, Jennison C, Saul C. Inequalities in accessing hip joint replacement for people in need. Eur J Public Health 2004;14:58-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yong PF, Milner PC, Payne JN, Lewis PA, Jennison C. Inequalities in access to knee joint replacements for people in need. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1483-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dixon T, Shaw M, Ebrahim S, Dieppe P. Trends in hip and knee joint replacement: socioeconomic inequalities and projections of need. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:825-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merx H, Dreinhofer K, Schrader P, Sturmer T, Puhl W, Gunther KP, et al. International variation in hip replacement rates. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millar WJ. Hip and knee replacement. Health Reports 2002;14:37-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunsmuir RA, Allan DB, Davidson LA. Increased incidence of primary total hip replacement in rural communities. BMJ 1996;313:1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams B, Whatmough P, McGill J, Rushton L. Private funding of elective hospital treatment in England and Wales, 1997-8: national survey. BMJ 2000;320:904-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steel N, Melzer D, Gardener E, McWilliams B. Need for and receipt of hip and knee replacement—a national population survey. Rheumatology 2006;45:1437-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawker GA, Guan J, Croxford R, Coyte PC, Glazier RH, Harvey BJ, et al. A prospective population-based study of the predictors of undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3212-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaturvedi N, Ben-Shlomo Y. From the surgery to the surgeon: does deprivation influence consultation and operation rates? Br J Gen Pract 1995;45:127-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Differences in expectations of outcome mediate African American/white patient differences in “willingness” to consider joint replacement. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2429-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byrne MM, Souchek J, Richardson M, Suarez-Almazor M. Racial/ethnic differences in preferences for total knee replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1078-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goddard M, Smith P. Equity of access to health care. Centre for Health Economics occasional paper. University of York, 1998.

- 45.Bowling A, Bond M, McKee D, McClay M, Banning AP, Dudley N, et al. Equity in access to exercise tolerance testing, coronary angiography, and coronary artery bypass grafting by age, sex and clinical indications. Heart 2001;85:680-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bowling A, Reeves B, Rowe G. Patient preferences for treatment for angina: an overview of findings from three studies. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008;13:suppl 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harries C, Forrest D, Harvey N, McClelland A, Bowling A. Which doctors are influenced by a patient’s age? A multi-method study of angina treatment in general practice, cardiology and gerontology. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:23-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaw M, Maxwell R, Rees K, Ho D, Oliver S, Ben-Shlomo Y, et al. Gender and age inequity in the provision of coronary revascularisation in England in the 1990s: is it getting better? Soc Sci Med 2004;59:2499-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elder AT, Shaw TR, Turnbull CM, Starkey IR. Elderly and younger patients selected to undergo coronary angiography. BMJ 1991;303:950-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacLeod MC, Finlayson AR, Pell JP, Findlay IN. Geographic, demographic, and socioeconomic variations in the investigation and management of coronary heart disease in Scotland. Heart 1999;81:252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petticrew M, McKee M, Jones J. Coronary artery surgery: are women discriminated against? BMJ 1993;306:1164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dong W, Ben-Shlomo Y, Colhoun H, Chaturvedi N. Gender differences in accessing cardiac surgery across England: a cross-sectional analysis of the health survey for England. Soc Sci Med 1998;47:1773-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kee F, Gaffney B, Currie S, O’Reilly D. Access to coronary catheterisation: fair shares for all? BMJ 1993;307:1305-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1991;325:221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ben-Shlomo Y, Chaturvedi N. Assessing equity in access to health care provision in the UK: does where you live affect your chances of getting a coronary artery bypass graft? J Epidemiol Community Health 1995;49:200-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Findlay I, Dargie J, Dyke T. Coronary angiography in Glasgow: relation to coronary heart disease and social class. Br Heart J 1991;66:70A. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Payne N, Saul C. Variations in use of cardiology services in a health authority: comparison of coronary artery revascularisation rates with prevalence of angina and coronary mortality. BMJ 1997;314:257-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Majeed FA, Chaturvedi N, Reading R, Ben-Shlomo Y. Equity in the NHS. Monitoring and promoting equity in primary and secondary care. BMJ 1994;308:1426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hippisley-Cox J, Pringle M. Inequalities in access to coronary angiography and revascularisation: the association of deprivation and location of primary care services. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:449-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feder G, Crook AM, Magee P, Banerjee S, Timmis AD, Hemingway H. Ethnic differences in invasive management of coronary disease: prospective cohort study of patients undergoing angiography. BMJ 2002;324:511-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ayanian JZ, Udvarhelyi IS, Gatsonis CA, Pashos CL, Epstein AM. Racial differences in the use of revascularization procedures after coronary angiography. JAMA 1993;269:2642-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Commission for Health Improvement. A report of clinical governance at King’s College Hospital Trust. Commission for Health Improvement, 2001.

- 63.Audit Commission. Data remember: improving the quality of patient-based information in the NHS. Management paper. Audit Commission, 2001.

- 64.Campbell SE, Campbell MK, Grimshaw JM, Walker AE. A systematic review of discharge coding accuracy. J Public Health 2001;23:205-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, Williams JI, Harvey B, Glazier R, et al. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: the role of clinical severity and patients’ preferences. Med Care 2001;39:206-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Glazier RH, Coyte PC, Harvey B, Williams JI, et al. The effect of education and income on need and willingness to undergo total joint arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:3331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Badley EM, Coyte PC. Perceptions of, and willingness to consider, total joint arthroplasty in a population-based cohort of individuals with disabling hip and knee arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:635-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dieppe P, Dixon D, Horwood J, Pollard B, Johnston M, MOBILE research team. MOBILE and the provision of total joint replacement. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008;13:suppl 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanders C, Donovan JL, Dieppe PA. Unmet need for joint replacement: a qualitative investigation of barriers to treatment among individuals with severe pain and disability of the hip and knee. Rheumatology 2004;43:353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jinks C, Ong BN, Richardson J. A mixed methods study to investigate needs assessment for knee pain and disability: population and individual perspectives. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007;8:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hudak PL, Clark JP, Hawker GA, Coyte PC, Mahomed NN, Kreder HJ, et al. “You’re perfect for the procedure! Why don’t you want it?” Elderly arthritis patients’ unwillingness to consider total joint arthroplasty surgery: a qualitative study. Med Decis Making 2002;22:272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ballantyne PJ, Gignac MA, Hawker GA. A patient-centered perspective on surgery avoidance for hip or knee arthritis: lessons for the future. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gignac MA, Davis AM, Hawker G, Wright JG, Mahomed N, Fortin PR, et al. “What do you expect? You’re just getting older”: a comparison of perceived osteoarthritis-related and aging-related health experiences in middle- and older-age adults. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:905-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanders C, Donovan J, Dieppe P. The significance and consequences of having painful and disabled joints in older age: co-existing accounts of normal and disrupted biographies. Sociol Health Illn 2002;24:227-53. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Kreder HJ, Glazier RH, Mahomed NN, Wright JG. The effect of patients’ sex on physicians’ recommendations for total knee arthroplasty. CMAJ 2008;178:681-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richards HM, Reid ME, Watt GC. Socioeconomic variations in responses to chest pain: qualitative study. BMJ 2002;324:1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Richards HM, Reid ME, Watt GC. Why do men and women respond differently to chest pain? A qualitative study. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2002;57:79-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1 Technical details of model

Appendix 2 Hip interaction plots

Appendix 3 Knee interaction plots

Appendix 4 Geographical variation in pattern of equity in access to hip replacement in different sociodemographic groups across districts in England

Appendix 5 Geographical variation in pattern of equity in access to knee replacement in different sociodemographic groups across districts in England