Abstract

The list of genes that when mutated cause disruptions in cerebellar development is rapidly increasing. The study of both spontaneous and engineered mouse mutants has been essential to this progress, as it has revealed much of our current understanding of the developmental processes required to construct the mature cerebellum. Improvements in brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and the emergence of better classification schemes for human cerebellar malformations, have recently led to the identification of a number of genes which cause human cerebellar disorders. In this review we argue that synergistic approaches combining classical molecular techniques, genomics, and mouse models of human malformations will be essential to fuel additional discoveries of cerebellar developmental genes and mechanisms.

Keywords: Cerebellum, Neurological and targeted mouse mutants, Congenital human cerebellar malformations, Genomics, Genetics, Ataxia

Introduction

In the last several decades, various approaches have contributed to our understanding of the molecular basis of cerebellar development. The study of spontaneous neurological mouse mutants aided many initial discoveries that are further reviewed below [1–5]. Significant advances in mouse genetics have allowed for more targeted studies using engineered gene knockouts and transgenic mice. These mice have facilitated the examination of more subtle phenotypes such as mild behavioral abnormalities and small disruptions in cerebellar circuitry [6–8]. Advances in brain imaging techniques and improvements in the classification of human cerebellar malformations have further aided the discovery of genes regulating cerebellar development. Genetics has recently enabled the identification of genes causing human pontocerebellar hypoplasia, Joubert syndrome, and Dandy–Walker malformation (DWM). When combined with studies in mouse, a variety of molecular mechanisms, including transcriptional regulation, mitochondrial function, and ciliary signaling have been implicated in homeostasis, patterning, and cell proliferation during cerebellar development. Concurrently, the application of new genomic techniques, which amass vast amounts of biological information, is just beginning to unravel the systems biology of the developing cerebellum. Here we discuss these issues and advocate the integrated use of human and mouse systems to further advance our knowledge of the molecular and developmental processes that form the cerebellum.

The Cerebellum as a Genetic System

The mature cerebellum has exquisite, stereotypical morphology, foliation, and lamination, which are consistent between individuals and highly conserved across vertebrates. At the cellular level, unlike other regions of the CNS, the cerebellum is composed of very few neuronal types, each with distinct morphology, arranged in discrete lamina, and connected in stereotypical circuits [9]. The cerebellum has essential roles in motor coordination, but is not essential for viability. Thus, compared with other regions of the central nervous system (CNS) the cerebellum has been more amenable to genetic studies since disruptions in development, which lead to abnormal morphology or function, are readily observed in obvious neurological and behavioral phenotypes. Because of this, it has been possible to obtain a precise understanding of cerebellar development [10–14]. The mechanisms deciphered from the study of cerebellar development have broad applicability to other CNS regions such as the cerebral cortex. For example, while initial insights regarding the function of the Reelin gene were gleaned from studying the cerebella of reeler mice ([15]; discussed below), recent studies have revealed that this gene is required for the emigration of dentate gyrus progenitors from a transient subpial zone and into the subgranular zone [16]. Also, while Foxc1 controls normal cerebellar and posterior fossa development by regulating secreted growth factor signals from the mesenchyme ([17]; discussed below), it is also required for the development of meningeal structures that in turn influence skull and cortical development [18].

Developmental Insights from Mouse Cerebellar Mutants

Spontaneous Neurological Mouse Mutants

A search of Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) at The Jackson Laboratory (www.informatics.jax.org) reveals just over 170 spontaneous, ENU- or X-ray-induced mutant alleles with altered cerebellar function or development. Most spontaneous cerebellar mutants were identified due to their behavioral or morphological phenotypes and, as such, are severely affected. Phenotype-to-gene approaches, commonly referred to as forward genetics, enabled an unbiased search for genes involved in cerebellar development, since the phenotype indicated that the mutation by definition affected a gene important for the disrupted process. There are no prior assumptions regarding gene function. Here we highlight several classical mutants to demonstrate that they have been pivotal to our current knowledge of cerebellar development and continue to be a rich resource for the cerebellar research community.

The staggerer mutation spontaneously arose at The Jackson Laboratory in 1955 and was first described in 1962 [19]. The cerebellum of these mice is small and there is pronounced post-natal loss of Purkinje and granule cells. The discovery that parallel fiber activity is important for the pruning and refinement of climbing fiber–Purkinje cell synaptic arrangement [1] was derived from these mutants prior to the identification of the causative deletion of retinoid-like orphan receptor alpha (Rora) in 1996 [20]. Staggerer chimeric analysis provided key evidence for the interdependence of Purkinje and granule cells during early post-natal development [2, 21]. Subsequent genome-wide expression analysis in staggerer mutants confirmed that Rora acts as a transcriptional regulator of Purkinje cells and regulates the secretion of sonic hedgehog (SHH), a mitogen for adjacent granule cell progenitors in the external granule layer [22].

The lurcher mouse, harboring a gain-of-function mutation in the delta 2 ionotropic glutamate receptor, Grid2, normally expressed in Purkinje cells, has also been an important model [3, 23]. The cerebellum of this mutant is hypoplastic due to severe post-natal degeneration of Purkinje, granule, and olivary neurons. The absence of Purkinje cells causes a significant reduction in the proliferation of granule cell precursors primarily due to a lack of the mitogenic effects of SHH. Other factors, such as IGF-1, FGF2, and EGF are known to act as mitogens in the cerebellum, but SHH has been shown to be over two orders of magnitude more potent [24]. Any granule cells that are produced due to the proliferative effects of these other factors end up dying since there is a paucity of Purkinje cells with which to form synaptic contacts. Indeed, there is a linear relationship between the number of Purkinje and granule cells in the cerebellum, and in the absence of enough Purkinje cells there occurs a concomitant death of the “extra” granule cells [25]. Thus, this mutant showed that target neurons likely provide trophic support to pre-synaptic contacts.

Leaner and weaver mice, harboring mutations in the alpha-1A calcium channel subunit gene, Cacna1a, and the potassium inwardly rectifying channel gene, Girk2, respectively, also exhibit Purkinje and granule cell death [5, 26, 27]. The leaner mouse has been useful in demonstrating the role of intracellular calcium ion concentrations and neuronal apoptosis in cerebellar development [4]. And even though Girk2 is expressed in both granule and Purkinje cells, the weaver mutation preferentially affects the former, demonstrating that some neurons are more susceptible to this particular mutation.

Not all mutations cause cerebellar cell death. The dreher (Lmx1a) mutant mouse fails to form the fourth ventricle roof plate, an essential embryonic signaling center adjacent to the developing cerebellar anlage. Loss of this transcription factor in the roof plate causes secondary mis-specification of adjacent cerebellar neurons [28, 29]. Disruption of neuronal migration also occurs in reeler and scrambler mutants, resulting in small cerebella with no foliation and ectopic clusters of Purkinje cells beneath the granule cell layer [30, 31]. Disruption of the large Reelin gene, which codes for a secreted extracellular matrix serine protease, is responsible for the reeler phenotype [15] whereas mutations in the Dab1 gene, coding for a cytoplasmic adapter protein, cause the scrambler phenotype [32]. It appears that Reelin acts as an inhibitory signal for migration because ectopic Purkinje cells form in both reeler and scrambler [33, 34]. The rostral cerebellar malformation mutant contains a mutation in the Netrin receptor Unc5h3 gene that results in over-migration of granule and Purkinje cells into the midbrain and fewer cerebellar folia [35]. Experiments with chimeras demonstrated the co-dependence of different cell types during cerebellar development as wild-type Purkinje cells exhibit inappropriate migration under the influence of Unc5h3 mutant granule cells [36].

Notably, there are many spontaneous and ENU-induced cerebellar mutants which remain to be characterized and are certain to add new, interesting, and likely unpredictable pieces to the puzzle of cerebellar development.

Targeted Mouse Mutants

The advent of transgenesis and gene-targeting technology has greatly aided the discovery of genes regulating cerebellar development. Gene expression patterns initially identified many genes likely to be involved in cerebellar development. Essential roles for these genes were verified in knockout mice. For example, insights on the function of the isthmic organizer and its role in defining the cerebellar territory along the early neural tube were found from analysis of targeted alleles of Gbx2, Otx2, En1/2, Wnt1, Fgf8, and other genes [37–40].

Modern molecular genetics methods have also provided an understanding of genes that cause subtle phenotypes not likely to be found in forward genetic screens. These phenotypes affect higher order roles of the cerebellum, such as learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity. For example, targeted mutants with a deletion of Grid2 result in Purkinje cell dendrites that form reduced synaptic contacts with granule cell parallel fibers. Whole-cell patch-clamp demonstrated that mutant Purkinje cells lack long-term depression (LTD) [6]. Mice with a targeted mutation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) also shed light on the molecular basis of cerebellar synaptic plasticity as they showed a spatial learning deficiency and a lack of cerebellar LTD [7]. Neuronal calcium ion concentration plays a role in synaptic plasticity through a variety of mechanisms, which include regulation of neurotransmitter release, gene transcription, and altered ion channel permeability. Mice lacking the gene for Calbindin1, an intracellular calcium-binding protein that acts as a calcium ion buffer in Purkinje cells, exhibit impaired movements only when challenged, suggesting an impairment of the cerebellum to adapt to a changing environment [8]. Patch-clamp recordings further revealed an alteration of synaptic calcium transients in mutant Purkinje cells. Moreover, an antisense transgenic approach to diminish Calbindin1 mRNA levels demonstrated that this gene is required for the maintenance of hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) and spatial learning [41]. Mice lacking the Calbindin2 gene (alias: Calretinin), which is expressed in granule cells, exhibit motor defects and increased granule cell excitability in the absence of abnormal morphology [42].

Current state-of-the-art mouse molecular genetics technologies now give us the ability to precisely and selectively modulate gene function. Thus, genes with essential roles throughout the developing embryo can be disrupted specifically in the cerebellum, leaving their non-cerebellar roles unaffected. Conditional gene ablation can be accomplished by the use of Cre-LoxP or other related recombinase systems, where a cell- or tissue-specific promoter drives the expression of Cre recombinase, which then excises any DNA flanked by recombinase recognition LoxP sequences. The tamoxifen-inducible Cre-LoxP system, which utilizes a fusion of Cre with an estrogen receptor ligand-binding domain, makes it possible to study gene function during a specific time and place in development [43]. A wide variety of regulatory sequences have been identified which can drive recombinase expression to individual cell types of the cerebellum and the developing CNS (reviewed in [44, 45]). For example, Pcp2 regulatory sequences have been widely used to target Cre expression to Purkinje cells [46], whereas Atoh1 regulatory elements are often used to drive Cre expression in granule cells [47]. These regulatory sequences can also be used to overexpress genes/alleles of interest in specific cell types. For example, the Gbx2 gene, which is critical for the placement of the mid-hindbrain junction, was ectopically expressed in the midbrain and rhombomere 1 of the hindbrain by using Cre expression driven by the regulatory elements of Engrailed1 [48]. This study showed that Gbx2 gain-of-function in this region of the brain eliminates the expression of isthmic organizer gene Fgf8, and results in the absence of the midbrain and cerebellum at later stages.

Additional studies in mouse and other model organisms such as zebrafish, can be further utilized to understand the molecular mechanisms of cerebellar development [49–53]. It is now feasible to generate specific models of human cerebellar malformations which allow for the study of underlying developmental biology of clinically important disorders.

Advances in Cerebellar Development from the Study of Human Cerebellar Malformations

In addition to spontaneous and targeted mouse mutants, the study of human cerebellar malformations is beginning to provide new insights regarding the basic developmental principles of the cerebellum. Currently, human patient populations with congenital developmental disorders are largely underutilized in basic research but they have proven to be valuable for identifying novel, significant developmental genes. As in the mouse, disruption of human cerebellar development is often severely handicapping but not lethal, making it amenable to genetic analysis. Also similar to mice, the structure of the human cerebellum facilitates the easy identification of malformations as its morphology, foliation, and lamination are stereotypical across individuals and its morphogenesis is well understood. In conjunction with advances in imaging techniques, this allows patients to be diagnosed with malformations at early post-natal or even fetal stages. While patient populations provide a great resource for researchers, they are not often employed due to several difficulties, including a lack of routine brain imaging on patients with developmental abnormalities, genetic heterogeneity among cerebellar patients resulting in the requirement of large sample sizes, and difficulties recruiting patients. Despite these obstacles, human cerebellar malformations have been used to identify cerebellar developmental genes [11, 54]. Gratifyingly, mutations in human RELN cause cerebellar hypoplasia, similar to the phenotype seen in the reeler mouse [55], demonstrating the validity of cross species comparisons. Once genes have been identified in human cerebellar malformation syndromes, mouse models have proven essential for deciphering the underlying developmental disruptions [11].

Types of Human Cerebellar Malformations

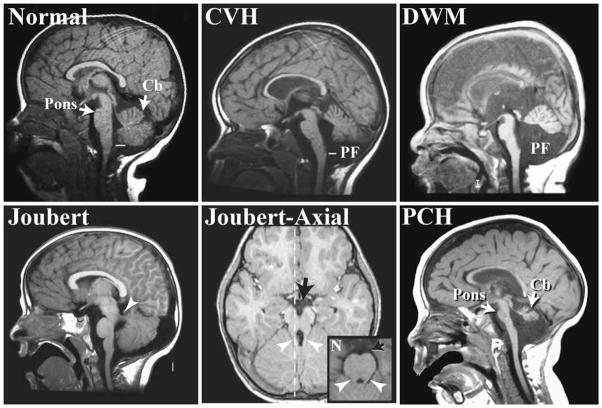

Advances in imaging, genetics, and classification are enabling previously consolidated malformations to be delineated into distinct categories [56, 57]. Here we will discuss cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (CVH), DWM, Joubert syndrome and related disorders (JSRD), and pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH) (Fig. 1). The defining features of these diagnoses are based on imaging criteria rather than clinical outcome, with most of these diagnoses associated with intellectual and motor disabilities. CVH is characterized by a small hypoplastic cerebellum with the vermis more affected than the hemispheres. DWM includes CVH; however, there is also an upward rotation of the cerebellar vermis that results in an enlarged fourth ventricle, and an increased size of the posterior fossa. DWM is the most common cerebellar malformation, with an estimated incidence of approximately 1 in 5,000 [57, 58]. CVH is also relatively common and often confused with DWM, making estimations of incidence problematic. CVH and DWM often present as sporadic cases, although there are several CVH loci with known recessive or X-linked inheritance [59–61]. Mendelian inheritance for DWM is rare, and the genetics are likely oligogenic [58, 62]. In contrast, JSRD are most often autosomal recessive disorders and are rare, with a population incidence estimated to be 1/100,000 [57]. As a group, JSRD are characterized by cerebellar vermis hypoplasia plus the presence of elongated cerebellar peduncles and a deepened interpeduncular fissure that appear as a “molar tooth” on axial brain scans. In addition, these patients exhibit axon guidance defects that include a decussation failure of the pyramidal tract and superior cerebellar peduncles. Patients with PCH exhibit a heterogeneous set of malformations characterized by hypoplasia and atrophy of the cerebellum, inferior olive, and ventral pons. This degenerative disorder often begins with embryonic atrophy of these regions.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance images (MRI) showing sagittal views of the cerebellar vermis from a subset of human cerebellar malformations. The image of a patient with cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (CVH) shows decreased vermis size that does not reach the obex, the narrowing of the fourth ventricle in the caudal medulla (white line), as occurs in normal subjects. In addition to vermis hypoplasia, subjects with Dandy–Walker malformation (DWM) also exhibit an increased posterior fossa size and an upward rotation of the vermis. The parasagittal image of a patient with Joubert syndrome shows vermis hypoplasia and an elongated superior cerebellar peduncle (white arrowhead). The plane of this off-midline image is designated with a dotted white line in the corresponding axial image. The “molar tooth” malformation of Joubert syndrome and related disorders can be seen in the axial MRI as elongated cerebellar peduncles (white arrowhead) and deepened interpeduncular fossa (black arrow) compared with a normal subject (N; inset). Subjects with pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH) exhibit both decreased vermis size and pontine hypoplasia (arrows). Cb cerebellum, PF posterior fossa

Causative Genes in Human Cerebellar Malformations

In the last decade, there has been considerable effort in defining the genetic basis of human cerebellar malformations. Causative genes include those involved in cerebellar patterning, cell fate specification, and other developmental processes (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of genes and suspected cellular processes that have been implicated in human cerebellar malformations (see text for discussion)

| Cerebellar malformations | Implicated human genes | Likely disrupted process |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (CVH) | OPHN1 [59, 60] | Spine morphogenesis |

| Dandy–Walker malformation (DWM) | ZIC1, ZIC4 [65], FOXC1 [17] | Granule cell differentiation |

| Joubert syndrome and related disorders (JSRD) | AHI1 [67, 68], ARL13B [69], CCD2A [70, 71], CEP290 [72, 73], INPP5E [74, 75], NPHP1 [76, 77], RPGRIP1L [78, 79], and TMEM67 [80] | Granule cell proliferation |

| Pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH) | CASK [86], RARS2 [88], TSEN54, TSEN34, and TSEN2 [89] | Spine development, cell proliferation, tRNA splicing, cellular maintenance. |

Pancreas specific transcription factor 1a (Ptf1a) was initially implicated as a basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor in pancreatic development since mice with a targeted deletion lacked pancreatic tissue [63]. However, its role in brain development was not investigated until truncations of this gene were found to result in cerebellar agenesis in multiple families [54]. Further investigations determined that loss of Ptf1a causes a failure to generate GABAergic cerebellar neurons in the embryonic cerebellar anlage in both human and mouse [64]. Since Purkinje cells, which are GABAergic, are also required for the proliferation of cerebellar granule neurons, humans and mice lacking Ptf1a exhibit profound cerebellar agenesis [64].

Transcription factors have also been implicated in other types of cerebellar malformations. Heterozygous loss of the ZIC1 and ZIC4 genes encoding zinc finger transcription factors can cause DWM, a phenotype which is mimicked in Zic1 and Zic4 double heterozygous mutant mice [65]. Mutations in FOXC1, a transcription factor gene located in the 6p25.3 locus, have recently been shown to contribute to human DWM [17]. Mouse models have demonstrated that Foxc1 is developmentally expressed in the mesenchyme adjacent to the cerebellum, where it is critical for normal posterior fossa development [66]. In addition to regulating skull development, Foxc1 controls mesenchymally expressed signaling molecules including Bmp2 and Bmp4 [17]. Loss of these signaling molecules causes the adjacent cerebellar rhombic lip to lose Atoh1 (Math1) expression, a gene critical for normal granule cell differentiation. These findings, based on studies in both human and mice, have surprisingly implicated mesenchymal signaling as a critical regulator of early cerebellar anlage development.

Studies of JSRD patients have also provided surprising insights into new developmental mechanisms. Of the nine loci linked to JSRD, eight have been cloned and the following causative genes identified: AHI1 [67, 68], ARL13B [69], CC2D2A [70, 71], CEP290 [72, 73], INPP5E [74, 75], NPHP1 [76, 77], RPGRIP1L [78, 79], and TMEM67 [80]. Many of these genes are implicated in normal ciliary function and their protein products localize to the cilia or basal bodies. One such cilia-related protein is Nephrocystin, the product of NPHP1, which interacts with beta-tubulin and localizes to primary cilia [81]. In cell culture, CEP290, centrosomal protein 290, is involved in ciliogenesis, localizes to centrioles in a microtubule-dependent manner, and regulates the microtubule network, as shown through RNAi. Furthermore, CEP290 interacts with the protein product of CCD2A both genetically and physically [71]. Most recently, mutations in the INPP5E gene, which codes for inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E, were found in patients with Joubert syndrome. While it was known that this enzyme hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositols, INPP5E was found to be localized to cilia and mutations resulted in premature destabilization of cilia after stimulation [74, 75]. Thus, examination of human patients led to a novel role for INPP5E in both cilia signaling and Joubert syndrome. Mutations in many components of this single biological pathway result in similar cerebellar defects. The actual purpose of cilia in the cerebellum is likely to be linked to SHH signaling. Significantly, loss-of-function mutations in murine Kif3a and Ift88—genes encoding intraflagellar transport proteins for the formation and maintenance of cilia—cause SHH-dependent proliferation defects of granule cell progenitors. This loss of SHH signaling results in cerebellar phenotypes resembling those seen in JSRD [82, 83]. JSRD now provide a model for how studies of human cerebellar malformations can lead to the discovery of causative genes and expand our knowledge of the pathways involved in cerebellar development.

Additional molecules have been implicated in human cerebellar malformations, which are certain to illuminate new cerebellar developmental mechanisms. Deletions of the Rho-GAP protein encoding gene Oliogphrenin-1 (OPHN1) have been found in multiple families with X-linked CVH [59, 60]. While Ophn1 is required for the stabilization of glutamatergic spines [84], it has not been implicated in regulating earlier developmental events such as cell division. Interestingly, mice with a targeted deletion of Ophn1 exhibit learning deficits and have dilated lateral and third ventricles, but their cerebellar size and morphology are normal [84]. This suggests that the mental retardation (MR) seen in human patients may not be due to cerebellar defects. However, until the connectivity and plasticity of the mutant mouse cerebellum are examined in detail this only remains a speculation. Recently Ophn1 has been shown to facilitate clathrin-mediated endocytosis of post-synaptic vesicles, including the AMPA receptor, by repressing the RhoA/ROCK pathway [85]. Because of this, mutant mice lack LTD in the hippocampus. Cerebellar LTD still remains to be examined.

Mutations of another molecule with a known role in synapse development have also been seen in PCH [86]. CASK is a calcium/calmodulin-dependant serine/threonine kinase localized to synapses via membrane-associated molecules, including Neurexin. CASK also regulates gene transcription during cell proliferation [87]. Although mouse Cask mutants have cerebellar hypoplasia, the developmental basis for this pathology has not yet been studied [86]. Genes from the tRNA splicing pathway have also been observed to cause PCH when mutated in humans. One family has been found with three members containing mutations in the RARS2 gene, which encodes mitochondrial arginine-transfer RNA synthase [88]. Individuals with PCH have also been found to have mutations in TSEN54, TSEN34, and TSEN2, which all encode tRNA splicing proteins [89]. The study of mouse models will be essential to determine why developing cerebellar and pontine cells are particularly sensitive to the loss of these genes even though they are ubiquitously expressed.

Human studies have demonstrated that patient clinical phenotypes associated with severe congenital cerebellar malformations described here can be highly variable. Less severe cerebellar malformations have been reported in patients with non-syndromic MR [57], Autism Spectrum Disorders, and schizophrenia [90–93]. Evidence of Purkinje cell dysfunction in cerebella from autistic patients has been demonstrated by reduced levels of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD67), which codes for a GABA-synthesizing enzyme [94]. In addition, levels of various gene transcripts involved in GABAergic transmission are altered in lateral cerebellar hemispheres of schizophrenic patients. Specifically, GAD67, GAD65, GAT-1, MGLUR2, and NOS1 were downregulated whereas GABAA-alpha6, GABAA-delta, GLUR6, and GRIK5 were upregulated [95]. Thus, it is likely that the genes underlying these more common and genetically complex neurodevelopmental disorders also influence cerebellar development. Notably, most patients with MR, autism, and other neurodevelopmental disorders rarely undergo brain imaging. Therefore, the coincidence of these disorders with cerebellar malformation is often missed. In order to fully and accurately delineate clinical phenotypes, we strongly advocate routine brain imaging of all human neurodevelopmental disorders. Further, given the extremely fine resolution with which cerebellar phenotypes can now be characterized in mice at the molecular, cellular, and systems level, mouse models for these common neurodevelopmental disorders are certain to be highly informative regarding their underlying pathology.

High-Throughput/Genomic Approaches for Identifying Novel Genes with Cerebellar Functions

While the study of single gene traits has been critical to our understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating cerebellar development, it is clear that genes do not function in isolation. Consequently, if cerebellar and indeed all biological research is to advance, the generation of new hypotheses will require the integration of large genome-wide datasets with both systems level and molecular networks. What follows is a description of some recent genomic studies that have contributed towards our understanding of nervous system development, in general, and cerebellar development, in particular.

SNP Arrays for Gene Discovery via Copy Number Analysis, Linkage Mapping and Genome-Wide Association Studies

Clinical karyotype analysis has shown that chromosomal aberrations over 4 Mb in size are associated with ~10% of MR cases [96] and with 17% of DWM cases [97]. However, high resolution array genomic hybridization, as well as high density single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarrays, now reveal that smaller structural variations are also frequently associated with neurodevelopmental disabilities. For instance, a 250-kb deletion overlapping the NRXN1 gene and a 1.4-Mb duplication including APBA2 were found in patients with schizophrenia [98]. Recently several copy number variants (CNVs) smaller than 50-kb were also discovered in patients with Autism Spectrum Disorders encompassing genes of the ubiquitin family (such as PARK2, RFWD2, PAPPA2, and FBXO40) [99]. Similar studies of patients with cerebellar defects are likely to yield causative genes. An additional advantage of SNP arrays is the ability to detect large regions of homozygosity that can be of consequence in inbred populations and imprinted loci. SNP arrays can be especially useful in performing linkage mapping on families with segregating cerebellar malformations as seen in JSRD [100], as well as carrying out population based genome-wide association studies (GWAS) such as for schizophrenia and autism [101, 102]. However, there are currently no GWAS of cerebellar malformations most likely due to extensive genetic heterogeneity and the need to utilize a large number of subjects in such studies. Efforts to recruit additional patients are likely to make GWAS possible.

Identifying causative genes in large CNV regions is particularly challenging. Recently, the phenotype dataset from a collection of 5,000 mouse gene knockouts was exploited in a systematic genome-wide analysis to forge links between genotype and disease [103]. Given that gene content within MR-associated CNVs and benign CNVs is essentially the same, gene function, rather than density, may better prioritize candidate genes. Indeed, the major finding of this study was that genes functioning in the nervous system were significantly enriched in MR-associated CNVs [103]. This clearly indicates that integration of human and mouse data will be essential for the identification of causative genes for developmental disorders. As detailed in the next sections, there are many mouse resources that can be exploited for this analysis.

Genome-Wide Gene Expression Datasets

Expression microarrays have become increasingly widespread in the last few years and, when employed sensibly [104], yield useful information in a short time. They have specifically been employed to address questions regarding cerebellar development. For instance, Ctnnd2 (catenin delta 2) was found to be a downstream target of Pax6 in the developing mouse brain, including the cerebellum, since it was downregulated in Pax6 mutants in the external granule layer, and its promoter was found to contain a binding site for Pax6 [105–107]. Interestingly, hemizygous deletions of human CTNND2 are associated with severe MR in cri-du-chat syndrome [108]. Whereas mice that lack Ctnnd2 are viable and display normal behavior, they exhibit deficits in learning and motor coordination [109]. It will be worthwhile to examine the cerebella of these mouse mutants in parallel with brain imaging studies of human patients. Another study compared microarray data from the pontine nuclei of wild-type mice with those from weaver and lurcher mutants, and demonstrated that the target environment of the cerebellum induces specific transcriptional changes in presynaptic pontine neurons [110].

There are a growing number of genome-wide datasets describing patterns of gene expression in the wild-type developing cerebellum. A microarray screen of early post-natal mouse cerebellum using only transcription factor probes revealed 227 genes expressed in neuronal and glial cells, 24 of which showed cell-type and stage-specific expression patterns [111]. These markers, therefore, serve as candidates for the examination of mutations in human cerebellar malformations. Gene expression profiling of the developing human brain from four gestational stages (18, 19, 21, and 23 weeks) has revealed that more than three-quarters of all known genes are expressed in the cerebellum [112]. There were 139 genes overexpressed in the cerebellum by two-fold or more when compared with other areas of the brain, some of which included HEY2, MSX2, LMX1A, FGFR1, FGF5, and ZNF536. Unsupervised clustering showed that, relative to other regions of the brain, the cerebellum was the most distinct structure, reflecting differences in cellular composition and developmental processes [112]. In situ hybridization patterns of a limited number of genes in the developing human brain can be found at http://hbatlas.org/. However, there are more extensive catalogs of gene expression in the mouse cerebellum. The Cerebellar Gene Regulation in Time and Space database (www.cbgrits.org) provides datasets of gene expression from wild-type and select cerebellar mutant mice during embryonic and early post-natal development. Additionally, the Cerebellar Development Transcriptome Database (CDT-DB; http://www.cdtdb.brain.riken.jp/CDT/) provides spatiotemporal gene expression profiles of the post-natal mouse cerebellum determined by methods such as RT-PCR, microarrays and in situ hybridizations. GENSAT (www.gensat.org) is a database containing verified transgenic mice that fluorescently label specific brain cells and regions. The BGEM database (www.stjudebgem.org) provides gene expression images from radioactive in situ hybridization in the mouse brain across embryonic, post-natal, and adult stages. The Allen Brain Atlas (http://www.brain-map.org/) contains in situ images of many genes in the developing mouse brain as well as ~20,000 genes in the adult, whereas Eurexpress (www.eurexpress.org) contains in situ images primarily from E14.5 mouse embryos.

Given the availability of these extensive gene expression datasets, it is now possible for investigators to assign functions to unannotated genes by correlating their expression with groups of known genes/markers. Computationally generated networks of interacting genes can provide additional clues about novel tissue-specific functions of a gene based on the number and combination of other genes present in the network [113].

Proteomics

While a cell’s transcriptome can be identified with relative ease, identification of the proteome is more difficult. Lack of protein amplification methods, the need for large quantities of biological samples, and equipment costs are hindrances to such attempts. In spite of these drawbacks, the method has been used to study the cerebellum. One study sought to identify the protein composition of the parallel fiber to Purkinje cell synapse through a proteomic approach [114]. This synapse was affinity-purified from 50 cerebella of transgenic mice and over 60 proteins were identified, including many of the known ones. Novel proteins included those involved in phospholipid metabolism and signaling such as Synaptojanin 1 and 2, Phospholipase B, ATP-binding cassette sub-family A (ABC1) member 12, and CDC42 binding protein kinase gamma (MRCK-gamma). It was also shown that MRCK-gamma is involved in maturation and shortening of dendritic spines. Proteomics, in combination with bioinformatics, has also been applied to identify ciliary proteins with the successful identification of Bardet–Biedl Syndrome (BBS)-causing genes [115–117]. Specifically, this was accomplished by comparing in silico the proteomes of non-flagellated organisms with those of ciliated/flagellated ones and obtaining a candidate list of proteins with likely ciliary or flagellar roles. Given that ciliary proteins have been implicated in cerebellar defects such as JSRD, extensive mining of these datasets as well as generation of additional ones will undoubtedly propel future cerebellar disease gene discoveries.

Newly Emerging Avenues of Cerebellar Developmental Research

Analysis of mutant mouse cerebella has historically driven our understanding of the molecules and processes that form the functional cerebellum. While the classification of human cerebellar malformations and subsequent identification of their causative genes has advanced the field, integration of genome-wide transcription and proteome data will allow the construction of cerebellar developmental molecular networks. Looking to the future, we see three emerging avenues of research, which will enhance our knowledge of cerebellar development.

Firstly, recent descriptions of zebrafish cerebellar development and the identification of markers for cerebellar neuronal populations will now facilitate more detailed examination of mutant fish phenotypes [50, 51, 118, 119]. While zebrafish cerebellar development differs in some ways from mouse and human, many developmental mechanisms are conserved. For example, morpholino-based loss-of-function experiments have demonstrated gene function of candidate JSRD genes, providing evidence for their involvement in human disease. Of particular note are the zebrafish mutants scorpion and sentinel, which correspond to human JSRD-causing mutations in the genes ARL13B and CC2D2A, respectively [69, 71].

Secondly, whole-genome sequencing and improved understanding of gene expression regulation will facilitate gene discovery in humans, mice, and zebrafish. Notably, there has been a historical bias towards the identification of mutations in protein-coding genes since detrimental changes are relatively easy to identify and interpret. There has been a paucity, however, of identified mutations in non-coding regions such as microRNA genes and other regulatory sequences. The advent of whole genome sequencing will enable us to identify yet more pathogenic mutations which will point to additional cerebellar genes.

Finally, brain imaging technology using functional MRI, diffusion tensor imaging, and other emerging modalities will be important to augment our understanding of cerebellar dysfunction even in the absence of obvious cerebellar malformations in humans and model organisms.

Conclusion

Our current understanding of the molecular and genetic basis of cerebellar development is derived primarily from the study of spontaneous and targeted mouse mutants. Only recently have human patients with cerebellar malformations begun to contribute to the discovery of genes that regulate the development of the cerebellum. Continued advances in the genomic technologies described here will facilitate the identification of other causative genes in human cerebellar malformations. In conjunction with continued use of model vertebrates, these novel approaches will yield additional genes—and hence networks—required in normal cerebellar development.

References

- 1.Crepel F, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Guastavino JM, Sampaio I. Multiple innervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells by climbing fibres in staggerer mutant mouse. Nature. 1980;283 (5746):483–4. doi: 10.1038/283483a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrup K, Mullen RJ. Staggerer chimeras: intrinsic nature of Purkinje cell defects and implications for normal cerebellar development. Brain Res. 1979;178(2–3):443–57. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takayama C, Nakagawa S, Watanabe M, Mishina M, Inoue Y. Developmental changes in expression and distribution of the glutamate receptor channel delta 2 subunit according to the Purkinje cell maturation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;92(2):147–55. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorenzon NM, Lutz CM, Frankel WN, Beam KG. Altered calcium channel currents in Purkinje cells of the neurological mutant mouse leaner. J Neurosci. 1998;18(12):4482–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04482.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil N, Cox DR, Bhat D, Faham M, Myers RM, Peterson AS. A potassium channel mutation in weaver mice implicates membrane excitability in granule cell differentiation. Nat Genet. 1995;11(2):126–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashiwabuchi N, Ikeda K, Araki K, Hirano T, Shibuki K, Takayama C, et al. Impairment of motor coordination, Purkinje cell synapse formation, and cerebellar long-term depression in GluR delta 2 mutant mice. Cell. 1995;81(2):245–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conquet F, Bashir ZI, Davies CH, Daniel H, Ferraguti F, Bordi F, et al. Motor deficit and impairment of synaptic plasticity in mice lacking mGluR1. Nature. 1994;372(6503):237–43. doi: 10.1038/372237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Airaksinen MS, Eilers J, Garaschuk O, Thoenen H, Konnerth A, Meyer M. Ataxia and altered dendritic calcium signaling in mice carrying a targeted null mutation of the calbindin D28k gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(4):1488–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sillitoe RV, Joyner AL. Morphology, molecular codes, and circuitry produce the three-dimensional complexity of the cerebellum. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:549–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chizhikov V, Millen KJ. Development and malformations of the cerebellum in mice. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;80(1–2):54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millen KJ, Gleeson JG. Cerebellar development and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18(1):12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carletti B, Rossi F. Neurogenesis in the cerebellum. Neuroscientist. 2008;14(1):91–100. doi: 10.1177/1073858407304629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alkan O, Kizilkilic O, Yildirim T. Malformations of the midbrain and hindbrain: a retrospective study and review of the literature. Cerebellum. 2009;8(3):355–65. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manto M. The cerebellum, cerebellar disorders, and cerebellar research—two centuries of discoveries. Cerebellum. 2008;7 (4):505–16. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature. 1995;374(6524):719–23. doi: 10.1038/374719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li G, Kataoka H, Coughlin SR, Pleasure SJ. Identification of a transient subpial neurogenic zone in the developing dentate gyrus and its regulation by Cxcl12 and reelin signaling. Development. 2009;136(2):327–35. doi: 10.1242/dev.025742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aldinger KA, Lehmann OJ, Hudgins L, Chizhikov VV, Bassuk AG, Ades LC, et al. FOXC1 is required for normal cerebellar development and is a major contributor to chromosome 6p25.3 Dandy–Walker malformation. Nat Genet. 2009;41 (9):1037–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarbalis K, Siegenthaler JA, Choe Y, May SR, Peterson AS, Pleasure SJ. Cortical dysplasia and skull defects in mice with a Foxc1 allele reveal the role of meningeal differentiation in regulating cortical development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104 (35):14002–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702618104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sidman RL, Lane PW, Dickie MM. Staggerer, a new mutation in the mouse affecting the cerebellum. Science. 1962;137:610–2. doi: 10.1126/science.137.3530.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton BA, Frankel WN, Kerrebrock AW, Hawkins TL, FitzHugh W, Kusumi K, et al. Disruption of the nuclear hormone receptor RORalpha in staggerer mice. Nature. 1996;379 (6567):736–9. doi: 10.1038/379736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrup K, Mullen RJ. Role of the Staggerer gene in determining Purkinje cell number in the cerebellar cortex of mouse chimeras. Brain Res. 1981;227(4):475–85. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(81)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold DA, Baek SH, Schork NJ, Rose DW, Larsen DD, Sachs BD, et al. RORalpha coordinates reciprocal signaling in cerebellar development through sonic hedgehog and calcium-dependent pathways. Neuron. 2003;40(6):1119–31. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00769-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuo J, De Jager PL, Takahashi KA, Jiang W, Linden DJ, Heintz N. Neurodegeneration in Lurcher mice caused by mutation in delta2 glutamate receptor gene. Nature. 1997;388 (6644):769–73. doi: 10.1038/42009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler-Reya RJ, Scott MP. Control of neuronal precursor proliferation in the cerebellum by Sonic Hedgehog. Neuron. 1999;22(1):103–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogel MW, Sunter K, Herrup K. Numerical matching between granule and Purkinje cells in lurcher chimeric mice: a hypothesis for the trophic rescue of granule cells from target-related cell death. J Neurosci. 1989;9(10):3454–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-10-03454.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrup K, Wilczynski SL. Cerebellar cell degeneration in the leaner mutant mouse. Neuroscience. 1982;7(9):2185–96. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fletcher CF, Lutz CM, O’Sullivan TN, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Hawkes R, Frankel WN, et al. Absence epilepsy in tottering mutant mice is associated with calcium channel defects. Cell. 1996;87(4):607–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millonig JH, Millen KJ, Hatten ME. The mouse Dreher gene Lmx1a controls formation of the roof plate in the vertebrate CNS. Nature. 2000;403(6771):764–9. doi: 10.1038/35001573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chizhikov VV, Lindgren AG, Currle DS, Rose MF, Monuki ES, Millen KJ. The roof plate regulates cerebellar cell-type specification and proliferation. Development. 2006;133(15):2793–804. doi: 10.1242/dev.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariani J, Crepel F, Mikoshiba K, Changeux JP, Sotelo C. Anatomical, physiological and biochemical studies of the cerebellum from Reeler mutant mouse. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1977;281(978):1–28. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1977.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sweet HO, Bronson RT, Johnson KR, Cook SA, Davisson MT. Scrambler, a new neurological mutation of the mouse with abnormalities of neuronal migration. Mamm Genome. 1996;7(11):798–802. doi: 10.1007/s003359900240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheldon M, Rice DS, D’Arcangelo G, Yoneshima H, Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K, et al. Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice. Nature. 1997;389(6652):730–3. doi: 10.1038/39601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goffinet AM, So KF, Yamamoto M, Edwards M, Caviness VS., Jr Architectonic and hodological organization of the cerebellum in reeler mutant mice. Brain Res. 1984;318(2):263–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldowitz D, Cushing RC, Laywell E, D’Arcangelo G, Sheldon M, Sweet HO, et al. Cerebellar disorganization characteristic of reeler in scrambler mutant mice despite presence of reelin. J Neurosci. 1997;17(22):8767–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ackerman SL, Kozak LP, Przyborski SA, Rund LA, Boyer BB, Knowles BB. The mouse rostral cerebellar malformation gene encodes an UNC-5-like protein. Nature. 1997;386(6627):838–42. doi: 10.1038/386838a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldowitz D, Hamre KM, Przyborski SA, Ackerman SL. Granule cells and cerebellar boundaries: analysis of Unc5h3 mutant chimeras. J Neurosci. 2000;20(11):4129–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04129.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joyner AL, Liu A, Millet S. Otx2, Gbx2 and Fgf8 interact to position and maintain a mid-hindbrain organizer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12(6):736–41. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wurst W, Bally-Cuif L. Neural plate patterning: upstream and downstream of the isthmic organizer. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(2):99–108. doi: 10.1038/35053516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez S. The isthmic organizer and brain regionalization. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;45(1):367–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura H, Katahira T, Matsunaga E, Sato T. Isthmus organizer for midbrain and hindbrain development. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;49(2):120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molinari S, Battini R, Ferrari S, Pozzi L, Killcross AS, Robbins TW, et al. Deficits in memory and hippocampal long-term potentiation in mice with reduced calbindin D28K expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(15):8028–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gall D, Roussel C, Susa I, D’Angelo E, Rossi P, Bearzatto B, et al. Altered neuronal excitability in cerebellar granule cells of mice lacking calretinin. J Neurosci. 2003;23(28):9320–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09320.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2002;244(2):305–18. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL. Conditional gene targeting in the mouse nervous system: insights into brain function and diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113(3):619–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X. Cre transgenic mouse lines. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;561:265–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-019-9_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang XM, Ng AH, Tanner JA, Wu WT, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, et al. Highly restricted expression of Cre recombinase in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Genesis. 2004;40(1):45–51. doi: 10.1002/gene.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schuller U, Zhao Q, Godinho SA, Heine VM, Medema RH, Pellman D, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FoxM1 regulates mitotic entry and prevents spindle defects in cerebellar granule neuron precursors. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(23):8259–70. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00707-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sunmonu NA, Chen L, Li JY. Misexpression of Gbx2 throughout the mesencephalon by a conditional gain-of-function transgene leads to deletion of the midbrain and cerebellum in mice. Genesis. 2009;47(10):667–73. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aldinger KA, Elsen GE, Prince VE, Millen KJ. Model organisms inform the search for the genes and developmental pathology underlying malformations of the human hindbrain. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2009;16(3):155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bae YK, Kani S, Shimizu T, Tanabe K, Nojima H, Kimura Y, et al. Anatomy of zebrafish cerebellum and screen for mutations affecting its development. Dev Biol. 2009;330(2):406–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaslin J, Ganz J, Geffarth M, Grandel H, Hans S, Brand M. Stem cells in the adult zebrafish cerebellum: initiation and maintenance of a novel stem cell niche. J Neurosci. 2009;29(19):6142–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0072-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rieger S, Senghaas N, Walch A, Koster RW. Cadherin-2 controls directional chain migration of cerebellar granule neurons. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(11):e1000240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elsen GE, Choi LY, Prince VE, Ho RK. The autism susceptibility gene met regulates zebrafish cerebellar development and facial motor neuron migration. Dev Biol. 2009;335(1):78–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sellick GS, Barker KT, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Fleischmann C, Cole-man RJ, Garrett C, et al. Mutations in PTF1A cause pancreatic and cerebellar agenesis. Nat Genet. 2004;36(12):1301–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hong SE, Shugart YY, Huang DT, Shahwan SA, Grant PE, Hourihane JO, et al. Autosomal recessive lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia is associated with human RELN mutations. Nat Genet. 2000;26(1):93–6. doi: 10.1038/79246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barkovich AJ, Millen KJ, Dobyns WB. A developmental and genetic classification for midbrain-hindbrain malformations. Brain. 2009 doi: 10.1093/brain/awp247. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parisi MA, Dobyns WB. Human malformations of the midbrain and hindbrain: review and proposed classification scheme. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;80(1–2):36–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Millen KJ, Grinberg I, Blank M, Dobyns WB. ZIC1, ZIC4 and Dandy–Walker malformation. In: Epstein CJ, Erickson RP, Wynshaw-Boris A, editors. Inborn errors of development. 2. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bergmann C, Zerres K, Senderek J, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Eggermann T, Hausler M, et al. Oligophrenin 1 (OPHN1) gene mutation causes syndromic X-linked mental retardation with epilepsy, rostral ventricular enlargement and cerebellar hypoplasia. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 7):1537–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Philip N, Chabrol B, Lossi AM, Cardoso C, Guerrini R, Dobyns WB, et al. Mutations in the oligophrenin-1 gene (OPHN1) cause X linked congenital cerebellar hypoplasia. J Med Genet. 2003;40 (6):441–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.6.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ross ME, Swanson K, Dobyns WB. Lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia (LCH): a heterogeneous group of cortical malformations. Neuropediatrics. 2001;32(5):256–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-19120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grinberg I, Millen KJ. The ZIC gene family in development and disease. Clin Genet. 2005;67(4):290–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krapp A, Knofler M, Ledermann B, Burki K, Berney C, Zoerkler N, et al. The bHLH protein PTF1-p48 is essential for the formation of the exocrine and the correct spatial organization of the endocrine pancreas. Genes Dev. 1998;12(23):3752–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoshino M, Nakamura S, Mori K, Kawauchi T, Terao M, Nishimura YV, et al. Ptf1a, a bHLH transcriptional gene, defines GABAergic neuronal fates in cerebellum. Neuron. 2005;47 (2):201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grinberg I, Northrup H, Ardinger H, Prasad C, Dobyns WB, Millen KJ. Heterozygous deletion of the linked genes ZIC1 and ZIC4 is involved in Dandy–Walker malformation. Nat Genet. 2004;36(10):1053–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rice R, Rice DP, Olsen BR, Thesleff I. Progression of calvarial bone development requires Foxc1 regulation of Msx2 and Alx4. Dev Biol. 2003;262(1):75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferland RJ, Eyaid W, Collura RV, Tully LD, Hill RS, Al-Nouri D, et al. Abnormal cerebellar development and axonal decussation due to mutations in AHI1 in Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(9):1008–13. doi: 10.1038/ng1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dixon-Salazar T, Silhavy JL, Marsh SE, Louie CM, Scott LC, Gururaj A, et al. Mutations in the AHI1 gene, encoding jouberin, cause Joubert syndrome with cortical polymicrogyria. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(6):979–87. doi: 10.1086/425985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cantagrel V, Silhavy JL, Bielas SL, Swistun D, Marsh SE, Bertrand JY, et al. Mutations in the cilia gene ARL13B lead to the classical form of Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(2):170–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Noor A, Windpassinger C, Patel M, Stachowiak B, Mikhailov A, Azam M, et al. CC2D2A, encoding a coiled-coil and C2 domain protein, causes autosomal-recessive mental retardation with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(4):1011–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gorden NT, Arts HH, Parisi MA, Coene KL, Letteboer SJ, van Beersum SE, et al. CC2D2A is mutated in Joubert syndrome and interacts with the ciliopathy-associated basal body protein CEP290. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(5):559–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Valente EM, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Barrano G, Krishnaswami SR, Castori M, et al. Mutations in CEP290, which encodes a centrosomal protein, cause pleiotropic forms of Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;38(6):623–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sayer JA, Otto EA, O’Toole JF, Nurnberg G, Kennedy MA, Becker C, et al. The centrosomal protein nephrocystin-6 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and activates transcription factor ATF4. Nat Genet. 2006;38(6):674–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bielas SL, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Kisseleva MV, Al-Gazali L, Sztriha L, et al. Mutations in INPP5E, encoding inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E, link phosphatidyl inositol signaling to the ciliopathies. Nat Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ng.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacoby M, Cox JJ, Gayral S, Hampshire DJ, Ayub M, Blockmans M, et al. INPP5E mutations cause primary cilium signaling defects, ciliary instability and ciliopathies in human and mouse. Nat Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ng.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Castori M, Valente EM, Donati MA, Salvi S, Fazzi E, Procopio E, et al. NPHP1 gene deletion is a rare cause of Joubert syndrome related disorders. J Med Genet. 2005;42(2):e9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.027375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parisi MA, Bennett CL, Eckert ML, Dobyns WB, Gleeson JG, Shaw DW, et al. The NPHP1 gene deletion associated with juvenile nephronophthisis is present in a subset of individuals with Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(1):82–91. doi: 10.1086/421846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arts HH, Doherty D, van Beersum SE, Parisi MA, Letteboer SJ, Gorden NT, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the basal body protein RPGRIP1L, a nephrocystin-4 interactor, cause Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39(7):882–8. doi: 10.1038/ng2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Delous M, Baala L, Salomon R, Laclef C, Vierkotten J, Tory K, et al. The ciliary gene RPGRIP1L is mutated in cerebellooculo-renal syndrome (Joubert syndrome type B) and Meckel syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39(7):875–81. doi: 10.1038/ng2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baala L, Romano S, Khaddour R, Saunier S, Smith UM, Audollent S, et al. The Meckel–Gruber syndrome gene, MKS3, is mutated in Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80 (1):186–94. doi: 10.1086/510499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Otto EA, Schermer B, Obara T, O’Toole JF, Hiller KS, Mueller AM, et al. Mutations in INVS encoding inversin cause nephronophthisis type 2, linking renal cystic disease to the function of primary cilia and left-right axis determination. Nat Genet. 2003;34(4):413–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chizhikov VV, Davenport J, Zhang Q, Shih EK, Cabello OA, Fuchs JL, et al. Cilia proteins control cerebellar morphogenesis by promoting expansion of the granule progenitor pool. J Neurosci. 2007;27(36):9780–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5586-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spassky N, Han YG, Aguilar A, Strehl L, Besse L, Laclef C, et al. Primary cilia are required for cerebellar development and Shh-dependent expansion of progenitor pool. Dev Biol. 2008;317 (1):246–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Khelfaoui M, Denis C, van Galen E, de Bock F, Schmitt A, Houbron C, et al. Loss of X-linked mental retardation gene oligophrenin1 in mice impairs spatial memory and leads to ventricular enlargement and dendritic spine immaturity. J Neurosci. 2007;27(35):9439–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2029-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Khelfaoui M, Pavlowsky A, Powell AD, Valnegri P, Cheong KW, Blandin Y, et al. Inhibition of RhoA pathway rescues the endocytosis defects in Oligophrenin1 mouse model of mental retardation. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(14):2575–83. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Najm J, Horn D, Wimplinger I, Golden JA, Chizhikov VV, Sudi J, et al. Mutations of CASK cause an X-linked brain malformation phenotype with microcephaly and hypoplasia of the brainstem and cerebellum. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1065–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ojeh N, Pekovic V, Jahoda C, Maatta A. The MAGUK-family protein CASK is targeted to nuclei of the basal epidermis and controls keratinocyte proliferation. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 16):2705–17. doi: 10.1242/jcs.025643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Edvardson S, Shaag A, Kolesnikova O, Gomori JM, Tarassov I, Einbinder T, et al. Deleterious mutation in the mitochondrial arginyl-transfer RNA synthetase gene is associated with pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(4):857–62. doi: 10.1086/521227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Budde BS, Namavar Y, Barth PG, Poll-The BT, Nurnberg G, Becker C, et al. tRNA splicing endonuclease mutations cause pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1113–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kanaan RA, Borgwardt S, McGuire PK, Craig MC, Murphy DG, Picchioni M, et al. Microstructural organization of cerebellar tracts in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Katsetos CD, Hyde TM, Herman MM. Neuropathology of the cerebellum in schizophrenia—an update: 1996 and future directions. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42(3):213–24. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Belmonte MK, Allen G, Beckel-Mitchener A, Boulanger LM, Carper RA, Webb SJ. Autism and abnormal development of brain connectivity. J Neurosci. 2004;24(42):9228–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Courchesne E, Townsend J, Saitoh O. The brain in infantile autism: posterior fossa structures are abnormal. Neurology. 1994;44(2):214–23. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yip J, Soghomonian JJ, Blatt GJ. Decreased GAD67 mRNA levels in cerebellar Purkinje cells in autism: pathophysiological implications. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113(5):559–68. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bullock WM, Cardon K, Bustillo J, Roberts RC, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Altered expression of genes involved in GABAergic transmission and neuromodulation of granule cell activity in the cerebellum of schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1594–603. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.van Karnebeek CD, Jansweijer MC, Leenders AG, Offringa M, Hennekam RC. Diagnostic investigations in individuals with mental retardation: a systematic literature review of their usefulness. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13(1):6–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Has R, Ermis H, Yuksel A, Ibrahimoglu L, Yildirim A, Sezer HD, et al. Dandy–Walker malformation: a review of 78 cases diagnosed by prenatal sonography. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2004;19(4):342–7. doi: 10.1159/000077963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kirov G, Gumus D, Chen W, Norton N, Georgieva L, Sari M, et al. Comparative genome hybridization suggests a role for NRXN1 and APBA2 in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17 (3):458–65. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Glessner JT, Wang K, Cai G, Korvatska O, Kim CE, Wood S, et al. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009;459(7246):569–73. doi: 10.1038/nature07953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lancaster MA, Gleeson JG. The primary cilium as a cellular signaling center: lessons from disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19(3):220–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O’Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460 (7256):748–52. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weiss LA, Arking DE, Daly MJ, Chakravarti A. A genome-wide linkage and association scan reveals novel loci for autism. Nature. 2009;461(7265):802–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Webber C, Hehir-Kwa JY, Nguyen DQ, de Vries BB, Veltman JA, Ponting CP. Forging links between human mental retardation-associated CNVs and mouse gene knockout models. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(6):e1000531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shi L, Jones WD, Jensen RV, Harris SC, Perkins RG, Goodsaid FM, et al. The balance of reproducibility, sensitivity, and specificity of lists of differentially expressed genes in microarray studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl 9):S10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S9-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Duparc RH, Boutemmine D, Champagne MP, Tetreault N, Bernier G. Pax6 is required for delta-catenin/neurojugin expression during retinal, cerebellar and cortical development in mice. Dev Biol. 2006;300(2):647–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Engelkamp D, Rashbass P, Seawright A, van Heyningen V. Role of Pax6 in development of the cerebellar system. Development. 1999;126(16):3585–96. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yamasaki T, Kawaji K, Ono K, Bito H, Hirano T, Osumi N, et al. Pax6 regulates granule cell polarization during parallel fiber formation in the developing cerebellum. Development. 2001;128 (16):3133–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Medina M, Marinescu RC, Overhauser J, Kosik KS. Hemizygosity of delta-catenin (CTNND2) is associated with severe mental retardation in cri-du-chat syndrome. Genomics. 2000;63 (2):157–64. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Israely I, Costa RM, Xie CW, Silva AJ, Kosik KS, Liu X. Deletion of the neuron-specific protein delta-catenin leads to severe cognitive and synaptic dysfunction. Curr Biol. 2004;14 (18):1657–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Diaz E, Ge Y, Yang YH, Loh KC, Serafini TA, Okazaki Y, et al. Molecular analysis of gene expression in the developing pontocerebellar projection system. Neuron. 2002;36(3):417–34. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schuller U, Kho AT, Zhao Q, Ma Q, Rowitch DH. Cerebellar ‘transcriptome’ reveals cell-type and stage-specific expression during postnatal development and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;33(3):247–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Johnson MB, Kawasawa YI, Mason CE, Krsnik Z, Coppola G, Bogdanovic D, et al. Functional and evolutionary insights into human brain development through global transcriptome analysis. Neuron. 2009;62(4):494–509. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Horan K, Jang C, Bailey-Serres J, Mittler R, Shelton C, Harper JF, et al. Annotating genes of known and unknown function by large-scale coexpression analysis. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(1):41–57. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.117366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Selimi F, Cristea IM, Heller E, Chait BT, Heintz N. Proteomic studies of a single CNS synapse type: the parallel fiber/Purkinje cell synapse. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(4):e83. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Li JB, Gerdes JM, Haycraft CJ, Fan Y, Teslovich TM, May-Simera H, et al. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell. 2004;117(4):541–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chiang AP, Nishimura D, Searby C, Elbedour K, Carmi R, Ferguson AL, et al. Comparative genomic analysis identifies an ADP-ribosylation factor-like gene as the cause of Bardet–Biedl syndrome (BBS3) Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(3):475–84. doi: 10.1086/423903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pazour GJ, Agrin N, Leszyk J, Witman GB. Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. J Cell Biol. 2005;170(1):103–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Delgado L, Schmachtenberg O. Immunohistochemical localization of GABA, GAD65, and the receptor subunits GABAAalpha1 and GABAB1 in the zebrafish cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2008;7(3):444–50. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.McFarland KA, Topczewska JM, Weidinger G, Dorsky RI, Appel B. Hh and Wnt signaling regulate formation of olig2+ neurons in the zebrafish cerebellum. Dev Biol. 2008;318(1):162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]