In natural habitats, bacteria are often faced with fluctuating stressful conditions. To enhance fitness in such environments, identical cells in isogenic populations have the capacity to stochastically differentiate into various phenotypes with special attributes (1–9). Stochastic fate determination guarantees variability because it provides each cell with the freedom to choose its own fate. This hedge survival strategy allows the population to continuously deploy specialized cells in anticipation of possible drastic changes in conditions. Canonical examples include transitions into competence (2–9) and transitions into slow-growing persister cells (7, 10). Interestingly, although each cell has the freedom to determine its own fate, the ratio between the phenotypes is adjusted to fit the encountered and anticipated conditions. These observations imply that stochastic cell differentiations are carried out with controlled odds to fit the needs of the population as a whole. Cellular capacity to manage the odds entails means to program and regulate the noise level and means to program the effect of the noise on the gene circuit performance (4–9, 11). Several studies show that circuit architecture can encode distinct noise behaviors critical for circuit task performance (3–5, 12, 13).

Motivated by the earlier studies of Cağatay et al. (13) on architecture-dependent noise behaviors involved in competence differentiation, Kittisopikul and Süel (14), in PNAS, investigated the general relations between circuit architecture, noise behaviors, and task performance within the context of feed-forward loops (FFLs) (15–18). They performed systematic comparison between the architecture-dependent noise behaviors of the eight alternative FFL architectures. What makes their investigations unique and the results of special interest is that they associated the computational analysis with the 858 documented FFLs in Escherichia coli that are sorted into 39 categories of biological functions. The analysis revealed that the FFL noise behavior correlates with biological function. Being of fundamental biological importance, these relationships may have driven evolutionary selection of gene network motifs. If so, this study marks the beginning of a new paradigm in which gene network architecture, stochasticity, and schemata of task performance coevolve.

Architecture-Dependent Noise

Genetic circuits with different architectures have been shown to generate similar dynamics and function (13–15). This poses the fundamental question as to why a gene circuit of particular architecture is selected to execute a specific function when the same function could, in principle, be done by alternative architectures (13). To understand how apparently similar circuit architectures can show very different noise levels, consider the following two simple architectures with different orders of consecutive activation and repression of genes. (i) Gene A is a repressor of B; B is an activator of C. (ii) Gene A is an activator of B; B is a repressor of C. Although the two cases have similar function (anticorrelation between A and C), their noise characteristics are different. The core of the matter is the difference in the stochastic behaviors of the transcription factors’ (TFs) binding and unbinding events. Whereas binding reactions depend on the concentration of transcription factors, the unbinding reactions are concentration independent (6, 11, 13, 14). Therefore, the two circuits give rise to different noise behaviors in the “on” and “off” states of A.

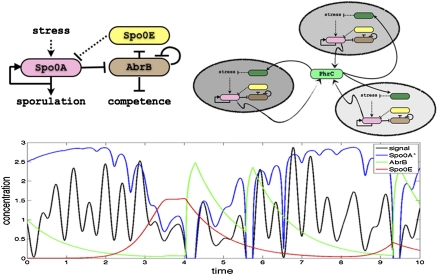

A very interesting example of how a genetic network can harness noise to attend to its needs is the control of competence and sporulation in Bacillus subtilis (2–9, 11, 13). In some parts of the network, noise is undesirable, such as in the commitment to sporulation. Fluctuations leading to a decision to sporulate at inconvenient times could have devastating consequences to the colony; therefore, the system has evolved to integrate stress signals over time, filtering out transient activations and guaranteeing a robust response (11). In other parts of the network, however, noise can be amplified by gene circuits with special architecture, such as the AbrB circuit discussed further below (11).

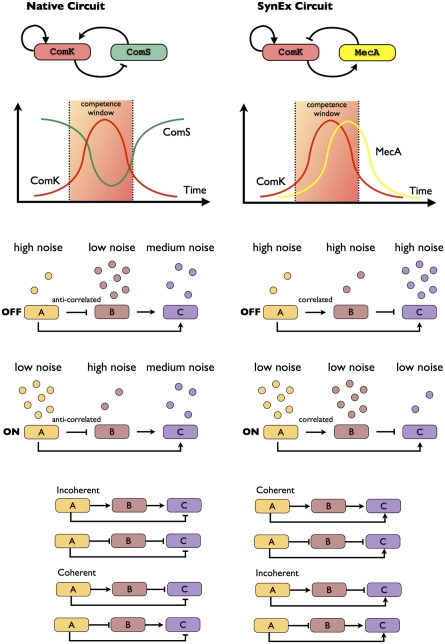

The transition into competence requires noise in the expression of its master regulator, ComK. A positive feedback loop on ComK is activated when fluctuations lead its concentration to cross a certain threshold. By interfering with the active degradation of ComK by MecA, a peptide, ComS, linked to the quorum sensing response sets the threshold for self-activation of ComK (Fig. 1). The noise in ComK expression can induce the system to jump over an effective potential barrier for the self-activation of ComK (6) in such a way that, by regulating the height of the barrier by ComS, the cell is able to control the probability of entering a competence cycle. The exit from competence is regulated by a negative feedback loop in which ComK indirectly represses the expression of its activator, ComS (Fig. 1). Hence, noise levels also regulate the mean time that cells spend in competence and the cell–cell variability in the competence duration.

Fig. 1.

(Top) Native circuit and an alternative artificial circuit SynEx implementing a negative feedback loop on ComK. (Middle) Cartoon explaining how the correlation between two FFL regulators A and B influence the noise level of C. When A and B are anticorrelated, one regulator is noisy and the other is not, distributing the noise over the “on” and “off” state. When A and B are correlated, the noise depends on the concentration of regulators, being high in the “off” state and low in the “on” state. (Bottom) The eight possible architectures of FFLs.

Architecture, Noise, and Task Performance

Recently, Cağatay et al. (13) showed that the architecture of the competence circuit determined the circuit susceptibility to noise and its task performance. The authors devised an elegant setup in which the native negative feedback circuit involving repression of ComS is replaced with an engineered synthetic one shown in Fig. 1. They found that, although the competence dynamics of the native and “synthetic” cells were similar, the native population exhibited higher cell–cell variability in competence durations, which allows efficient response over a broader range of environmental conditions. These findings support the idea that environmental constraints can select for specific architectures of gene regulatory circuits, based on noise requirements for the circuit task performance.

Intriguingly, the regulatory circuit of the meiotic master regulator Ime1 is similar to the synthetic circuit engineered by Cağatay et al. (13). It is conceivable that such architecture has been selected to regulate meiosis, to limit cell–cell variability in meiosis differentiation (19). Like sporulation, the meiosis commitment is not reversible, and thus the decision to enter meiosis at the wrong time can be harmful.

Circuit Architecture, Noise, and Task Performance in Feed-Forward Loops (FFLs)

FFL motifs are abundant in nature, and examples of all possible architectures have been identified and shown to regulate a multitude of cellular processes in a diverse range of organisms ranging from bacteria to human cells (16, 17).

The prototypical FFL has three nodes (genes): input node A, intermediate node B, and output node C. Analysis of all eight possible FFL architectures showed that, despite their topological diversity, FFLs exhibit only two classes of noise behavior dependent on the correlation between nodes A and B. Rare events are regulated by FFLs with high noise in the OFF state, such as the transition into persister cells. Cellular processes which are in high demand are regulated by FFLs with high noise in the ON state, such as anaerobic respiration. In Fig. 1, we show and explain the two types of noise behavior for correlated and anticorrelated incoherent FFL circuits.

To determine whether this opposite-noise behavior among FFLs is of biological relevance, the authors performed a comprehensive functional analysis of all FFLs identified in E. coli. As mentioned previously, the authors provide an explanation of the evolution of network motifs according to which gene network architecture, stochasticity, and schemata of task performance coevolve.

It is intriguing to note that the ComK circuit can be represented as an FFL in which ComK takes the role of nodes A and C, whereas node B is ComS in the native circuit and MecA in the synthetic one. Thus, the native and the synthetic circuits correspond to the anticorrelated and correlated FFLs, respectively, in agreement with the noise behaviors of the four circuits.

Looking Ahead

Specialized gene circuits have evolved to coordinate the decision-making between different individual cells, such as the quorum sensing and the Rap systems which control sporulation and competence transitions (11). One fascinating example is the AbrB decision-making circuit shown in Fig. 2, which has a surprising dual role as noise amplifier and cell–cell coordinator (11). The existence of many sophisticated circuits that incorporate cell–cell communication in the fate decisions of individual cells might suggest metaevolution of decision-making and communication circuits architecture, noise, and function.

Fig. 2.

(Upper Left) Spo0A, AbrB, and Spo0E repress each other in sequence, forming an incoherent loop. Dotted lines represent transfers of phosphate. This circuit receives stress signals as input and regulates both competence and sporulation. (Upper Right) The AbrB circuit is coupled with similar circuits in neighboring cells through the secretion of a peptide PhrC, which synchronizes the decision process throughout the colony (11). (Lower) AbrB circuit can exhibit rich dynamics for implementing variability in determining cell fate (11).

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was provided in part by the Tauber Family Foundation, the Maguy–Glass Chair in Physics of Complex Systems at Tel Aviv University, National Science Foundation-sponsored Center for Theoretical Biological Physics Grants PHY-0216576 and 0225630, and the University of California at San Diego.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 13300.

References

- 1.Kaern M, Elston TC, Blake WJ, Collins JJ. Stochasticity in gene expression: From theories to phenotypes. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:451–464. doi: 10.1038/nrg1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maamar H, Dubnau D. Bistability in the Bacillus subtilis K-state (competence) system requires a positive feedback loop. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:615–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Süel GM, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Liberman LM, Elowitz MB. An excitable gene regulatory circuit induces transient cellular differentiation. Nature. 2006;440:545–550. doi: 10.1038/nature04588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maamar H, Raj A, Dubnau D. Noise in gene expression determines cell fate in Bacillus subtilis. Science. 2007;317:526–529. doi: 10.1126/science.1140818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Süel GM, Kulkarni RP, Dworkin J, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Elowitz MB. Tunability and noise dependence in differentiation dynamics. Science. 2007;315:1716–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1137455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultz D, Ben Jacob E, Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Molecular level stochastic model for competence cycles in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17582–17587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707965104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Losick R, Desplan C. Stochasticity and cell fate. Science. 2008;320:65–68. doi: 10.1126/science.1147888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acar M, Mettetal JT, van Oudenaarden A. Stochastic switching as a survival strategy in fluctuating environments. Nat Genet. 2008;40:471–475. doi: 10.1038/ng.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raj A, van Oudenaarden A. Nature, nurture, or chance: Stochastic gene expression and its consequences. Cell. 2008;135:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balaban NQ, et al. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science. 2004;305:1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultz D, Wolynes PG, Ben Jacob E, Onuchic JN. Deciding fate in adverse times: Sporulation and competence in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21027–21034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912185106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kollmann M, Løvdok L, Bartholomé K, Timmer J, Sourjik V. Design principles of a bacterial signalling network. Nature. 2005;438:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature04228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cağatay T, Turcotte M, Elowitz MB, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Süel GM. Architecture-dependent noise discriminates functionally analogous differentiation circuits. Cell. 2009;139:512–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kittisopikul M, Süel GM. Biological role of noise encoded in a genetic network motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13300–13305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003975107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alon U. Network motifs: Theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangan S, Alon U. Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11980–11985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133841100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HD, Shay T, O’Shea EK, Regev A. Transcriptional regulatory circuits: Predicting numbers from alphabets. Science. 2009;325:429–432. doi: 10.1126/science.1171347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh B, Karmakar R, Bose I. Noise characteristics of feed forward loops. Phys Biol. 2005;2:36–45. doi: 10.1088/1478-3967/2/1/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nachman I, Regev A, Ramanathan S. Dissecting timing variability in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2007;131:544–556. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]