Abstract

During the last 20 years, our understanding of the mechanisms underlying Alzheimer's disease (AD) has considerably improved, in part owing to both in vitro and in vivo model systems. Studies in mice expressing both human amyloid precursor protein and human tau have provided clear evidence that amyloid-β and tau interact in the pathogenesis of AD. Moreover, amyloid-β toxicity has been shown to be tau-dependent since reducing tau levels prevents behavioral deficits and sudden death in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. As tau pathology preferentially develops in specific sites and spreads in a predictable manner across the brain, understanding the mechanism underlying tau dysfunction should be a focus in AD mouse modeling. A defined effort must be made to develop therapies that directly address the impact of tau dysfunction in the pathogenesis of AD. Finally, early diagnosis of AD is essential and this must be made possible by identification of early biomarkers, behavioral changes or use of novel imaging techniques.

Keywords: amyloid cascade hypothesis, amyloidosis, brain imaging techniques, clinical diagnosis, cognitive dysfunction, neuronal loss, tauopathy

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a common form of dementia characterized by loss of memory and other intellectual abilities serious enough to interfere with daily life. Alzheimer's disease accounts for 50–70% of dementia cases [101]. Other types of dementia include vascular dementia, mixed dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). The diagnosis of AD is confirmed after postmortem examination and is dependent on the identification of senile plaques composed of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of hyperphosphorylated tau [1]. Several genes have been implicated in AD, most notably, those encoding amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin (PSEN)1 and 2 (reviewed in [2]). In addition, the ApoE has been associated with sporadic AD [3,4] and mutant tau has been shown to cause the related tauopathy FTD with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) demonstrating that tau dysfunction can cause neurodegeneration and lead to cognitive and/or behavioral deficits [5–7].

Which came first, the amyloid or the tau?

Our understanding of the mechanisms underlying AD has progressed considerably during the last 20 years, especially with regard to the role of Aβ in the pathogenesis of this disease. Originally proposed in 1991, one of the central hypotheses in the AD field is the amyloid cascade hypothesis, which posits that abnormal accumulation of Aβ plays a causal role in triggering the full spectrum of AD neuropathology, which includes neuronal death, and formation of amyloid plaques and NFTs [8,9]. Recent works have refined this hypothesis, with some now suggesting that soluble Aβ oligomers rather than Aβ deposits primarily contribute to synaptic dysfunction, neuronal death, NFT formation and memory impairment in AD [10,11]. The precise toxic species of Aβ (i.e., monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar Aβ) have not been defined, yet this clarification may have an important impact on the development of AD therapeutics [12,13]. Current AD therapy driven by the amyloid cascade hypothesis primarily focuses on reducing toxic Aβ levels by blocking Aβ generation and by removing Aβ through immunotherapy. However, the human Phase IIa clinical study was halted after 6% of the subjects developed meningoencephalitis [14]. The follow-up study of the original Phase I Aβ42 immunization trial revealed no evidence of a delay in disease progression [15]; however, significant plaque removal was clearly confirmed in human subjects. This suggests that Aβ immunization may only show substantial therapeutic benefit if it is initiated at earlier stages of the disease, perhaps before mild cognitive impairment [16].

On the other hand, NFTs reflect intraneuronal changes and the extent of NFTs correlates with the progression of dementia; therefore, the mechanism underlying NFT formation represents a factor that appears to contribute to the cognitive dysfunction observed in individuals affected by AD. Indeed, NFTs are a key neuropathological feature of AD and other neurodegenerative diseases, collectively termed tauopathies (reviewed in [17]). During normal aging, NFTs first appear in the entorhinal cortex [18]. However, as dementia progresses, NFTs appear in neocortical and limbic areas, including the hippocampus. Individuals with NFTs in limbic regions show learning and memory difficulties. Moreover, the presence of NFTs in neocortex correlates with more severe levels of dementia [19]. Interestingly, Braak and Braak found that, in the entorhinal cortex, NFT formation is independent of Aβ deposition, while in limbic and neocortical areas, NFT formation only occurs after Aβ deposition [20]. Their analysis suggests that the chronology of pathological changes appears to start with NFTs developing in entorhinal cortex in the absence of Aβ and continues with Aβ deposition, which then triggers the appearance of NFTs into limbic and neocortical areas. This hypothesis would imply that brain aging is characterized by NFT development in the entorhinal cortex, and that Aβ can accelerate NFT formation, resulting in AD; however, this suggestion is based on the end stage pathologies and not necessarily the molecular events and interactions leading to the pathologies.

Our lack of a clear understanding of these molecular and biochemical events leading to amyloidosis and tauopathy, as well as the interaction between the two has prompted the field to create mouse models to mimic key events in the development of AD. The field has yet to develop a perfect mouse model of AD given the fundamental differences between mice and humans; however, many of the currently existing mouse models closely replicate salient aspects of the disease. Here, we review some of the most widely studied mouse models of AD-related pathologies.

Modeling amyloidosis

Derived from the protein encoded by the APP gene, Aβ is a hydrophobic peptide that pathologically deposits in the brains of individuals affected by AD. Sequential cleavage of APP by β- and γ-secretases releases Aβ into the luminal/extracellular space [21]. Owing to the loose site specificity of γ-secretase-mediated proteolysis, various C-terminal truncated Aβ species, including two major species, Aβ40 and Aβ42, are also generated. Aβ40 is the most predominant species of secreted Aβ; however, Aβ42 is hypothesized to be the trigger species for AD-related amyloid patho-physiology owing to a faster aggregation potential compared with Aβ40 [22,23]. The significant neurotoxicity of oligomeric and/or fibrillar Aβ aggregates indicates that accumulation of Aβ is a central pathogenic event in AD [24]. Indeed, histochemical and biochemical studies have revealed that Aβ42 primarily deposits within the brains of both AD patients and several animal models. In 1991, the first APP missense mutation in familial AD (FAD) was identified in a British kindred [25]. In mutation carriers, a valine was replaced by an isoleucine at codon 717 (V717I). To date, 20 missense mutations in the APP gene have been identified (reviewed in [26]). Moreover, more than 160 mutations in the PSEN genes have been identified in early-onset FAD (reviewed in [2]). PSEN are central components of the atypical aspartle protease complexes responsible for the γ-secretase cleavage of APP [27,28]. Identification of these genetic deficits that can underlie the development of AD has allowed the development of cell and mouse models for AD as mutations in the APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 genes have been found to specifically increase the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio and accelerate the parenchymal accumulation of Aβ [29–34]. The mechanism through which FAD mutations modify overall γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of APP, leading to increased Aβ42:Aβ40 ratios, remains unclear. The increased Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio may possibly result from direct alterations in the cleavage reactions catalyzed by mutant PSEN such that Aβ42 generation is facilitated, Aβ40 generation is attenuated, or both Aβ40 and Aβ42 generation change in a different manner. Recently, several groups observed that decreasing Aβ40 levels without an increase in Aβ42 was associated with a subset of AD-causing PSEN mutations [32,33,35,36]. Several in vitro studies suggest that Aβ40 directly interferes with Aβ42 aggregation by delaying the Aβ42-mediated nucleation step at an early stage in the fibrillogenesis process [37–40].

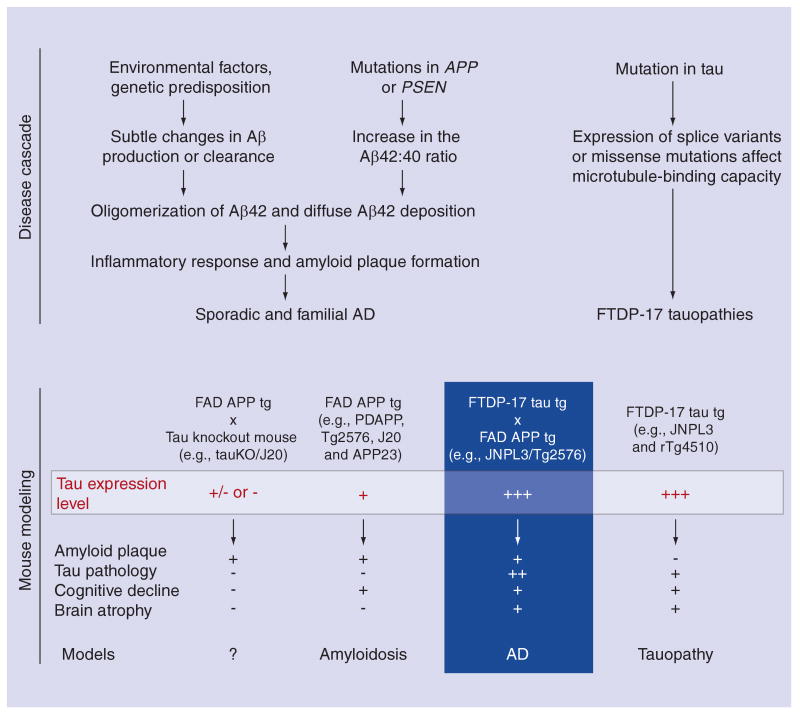

Transgenic mice overexpressing mutant human APP, which reproduce Aβ plaque formation, have been extensively used to study AD-related pathogenic mechanisms in vivo [41–44]. The most successful APP transgenic mouse models have employed expression of full-length human APP with FAD mutations. The first transgenic mouse exhibiting AD-like plaques was the PDAPP mouse, expressing human APP containing the V717F Indiana mutation under the control of the PDGF promoter [42]. This mouse exhibited extracellular Aβ plaques of varying morphology, many plaques having dense compact cores, with others being much more diffuse in appearance. The plaques appeared from approximately 6 to 9 months of age. The second successful mouse line was the Tg2576 mouse that overexpressed the 695 isoform of human APP with the Swedish double mutation (APPSwe; K670N/M671L) under the control of the hamster prion protein promoter [43]. In this mouse model, both diffuse and dense core amyloid plaques were found in the cortex and hippocampus at 9–11 months of age. As an additional model, the APP23 mouse expressing APP751Swe cDNA coupled to the murine thy-1 gene developed congophilic deposition of Aβ in parenchyma from 6 months of age [44] and in the cerebral vasculature beyond 1 year of age [45]. Subsequently, many more APP transgenic models have been developed, such as the TgCRND8, which overexpressed the 695 isoform of human APP with both the Swedish and Indiana mutations under the control of the hamster prion protein promoter [46], or J20 mice, which expresses a human APP minigene with the Swedish and Indiana mutations under control of the PDGF promoter (Figure 1) [41].

Figure 1. Disease cascades leading to amyloidosis and tauopathy in humans and mouse models.

Mutations in APP and PSEN genes can lead to AD; however, the discovery of mutations within the MAPT gene encoding tau protein demonstrated that tau dysfunction alone could cause neurodegeneration, at least in FTDP-17. It is still unclear how amyloid influences the tau cascade to yield both amyloid and tau pathology within the same disease (AD). Given this, a number of Tg mice have been generated to provide models in which we can examine the origin of the main pathological features of these diseases and ultimately test therapeutics aimed at abrogating toxic species of amyloid or tau. A number of different models are listed under the cascade that they attempt to model. Tau levels are noted in each of these models where endogenous is represented as (+), overexpression is represented as (+++), and degree of tau deficiency is either (-) or (+/-). Salient features of AD or FTDP-17 that are recapitulated within each model are noted. Aβ: Amyloid β; AD: Alzheimer's disease; APP: Amyloid precursor protein; PSEN: Presenilin; FAD: Familial AD; FTDP: Frontotemporal Dementia with Parkinson's; tg: Transgenic.

In a novel attempt to understand the specific role of either Aβ peptide in AD pathogenesis, that eliminated complicating factors such as the APP processing derivatives and the sub-cellular localization of processing, a protein chimera was used to drive expression of either human Aβ40 or Aβ42 in transgenic mice in the absence of human APP [47]. Using this paradigm, BRI-Aβ40 transgenic mice did not develop amyloid pathology at any age, while BRI-Aβ42 transgenic mice have high levels of Aβ42 with considerable amyloid plaque pathology. When the authors crossed Tg2576 with the BRI-Aβ40 mice, the resultant bigenic BRI-Aβ40/Tg2576 mice had dramatic reductions in both immuno-histochemical Aβ loads and thioflavin S-positive plaques compared with age-matched Tg2576 littermates. These observations indicate that Aβ40 has protective effects against the aggregation of Aβ42. Increased levels of either Aβ40 or Aβ42 in BRI-Aβ/Tg2576 mice failed to enhance axonal defects observed in Tg2576 mice alone, suggesting that APP-induced axonopathy was not due to Aβ [48].

Modeling tauopathy

Tau is a phosphoprotein that belongs to the family of the microtubule-associated proteins. The primary function of tau protein (reviewed in [49]), which is normally localized in the axons of neurons, is to stabilize microtubules (MTs). With its ability to modulate MT dynamics, tau contributes to key structural and regulatory cellular functions, such as maintaining neuronal processes and regulating axonal transport, respectively. The normal dynamic equilibrium of MT-bound tau is primarily determined by the phosphorylation state of tau. MT-bound tau is promoted by dephosphorylation of tau and detachment of tau from MT is promoted by phosphorylation of tau. There are six major isoforms in the adult human brain, all of which are derived from a single gene located on human chromosome 17. The six tau isoforms differ from each other in the number of tubulin-binding repeats (either three or four, referred to as 3R and 4R tau isoforms, respectively) and in the presence or absence of either one or two 29-amino acid-long inserts at the N-terminal portion of the protein. This protein is abnormally accumulated as filamentous inclusions in a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, Pick's disease and FTDP-17 (reviewed in [17]). These tau inclusions, which appear as paired helical filaments (PHF), twisted ribbons or straight filaments, are detergent-insoluble and predominantly composed of hyperphosphorylated tau [50–54]. In AD, NFTs and neuronal cell loss typically coincide within the same brain regions [55]. The progressively expanding anatomical distribution of NFTs reflects progressive brain dysfunction in disease, suggesting that NFT formation and neuronal cell loss may share a common mechanism [56]. Initial attempts to model tauopathy relied on the over-expression of wild-type human tau protein [57]. While many of these wild-type tau transgenic models mimicked the pretangle pathology that is observed in early stage AD and other tauopathies, mature tauopathy and profound neuronal loss was not observed in these models.

The most impressive mouse model of wild-type tauopathy (termed Htau) relied on a human Pl artificial chromosome containing the entire human tau gene; however, tauopathy was not observed in this model until the human tau transgene was introduced onto a murine tau-deficient background [58]. The tauopathy in the Htau model is somewhat slow to develop; mice older than 15 months of age developed tau-opathy, DNA fragmentation and a quantitative loss of neurons [58,59]. The failure of the Htau mice to develop significant tauopathy in the context of murine tau expression suggested that murine tau may reduce the propensity of human tau to become hyperphosphorylated at the levels expressed in the transgenic line. While it is conceivable that higher levels of wild-type human tau expression, even in the context of murine tau, may eventually result in rapidly progressing tauopathy, this model does not yet exist.

The finding that patients with FTDP-17 harbor tau mutations [5–7] strongly suggested that tau dysfunction itself can cause neurodegeneration. As with models of amyloidosis, the identification of tau mutations in association with the tauopathy FTDP-17 has proven essential in the development of models of mature tauopathy. Indeed, overexpression of mutant tau in various animal models has been demonstrated to induce neurodegeneration [60–67]. More recently, the rTg4510 mouse model was developed to generate a model with significant forebrain tauopathy, a feature that was absent in most previous models of tauopathy [68]. The rTg4510 model uniquely employed the CaMKIIa promoter-driven tetracycline effector transgene to focus human mutant P301L tau overexpression in the forebrain and provide conditional control of the transgenic tau expression. The rTg4510 mice developed robust neurofibrillary pathology in the cortico-limbic area, which is physiologically relevant to AD and other tauopathies. The amount of P301L tau protein in mouse forebrains at 2.5 months of age was approximately 13-times the level of endogenous tau in littermates. The rTg4510 mice develop pretangle pathology at 2.5 months and mature neurofibrillary tangles at 4 months in the cortex and at 5.5 months in the hippocampus. The progressive accumulation of biochemically abnormal, sarkosyl insoluble tau corresponds to the severity of tau pathology, with the emergence of a robust 64-kDa species that correlates with the presence of mature neurofibrillary tangles. In addition to the development of neuropathologically and biochemically abnormal tau, approximately a 50% loss of CA1 neurons was observed in the 5.5-month rTg4510 mice by using unbiased stereological analysis [68,69]. The rTg4510 mice also showed profound deficits in cognition related to disease progression (Figure 1), thereby providing a robust behavioral measurement related to tau dysfunction, a quality that had not been shown in wild-type tau transgenic mouse models. In rTg4510 mice, suppression of P301L tau to its basal level of human tau (2.5-fold endogenous owing to a leaky transgene) reversed behavioral impairments, although NFTs continued to increase [68]. This suggested that NFTs were unlikely to be the initial neurotoxic species.

Most recently, Clavaguera et al. reported that injection of brain extract from mutant P301S tau transgenic mice into the brain of transgenic ALZ17 mice expressing wild-type tau induced assembly of wild-type tau into filaments and spreading of pathology from the site of injection to neighboring brain regions [70]. This work has brought attention to an intriguing view that a small amount of aggregated tau seeding was able to promote wild-type tau aggregation in a prion-like fashion. Interestingly, even though the injected ALZ17 mice developed tau pathology, it did not lead to neuronal loss, suggesting transitioning of wild-type tau did not facilitate neuronal toxicity. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to test any other models, such as Htau mice by the injection of post-mortem brain extracts from tauopathy patients.

Modeling Alzheimer's disease

Although amyloidosis, tauopathy, neuronal loss and cognitive dysfunction had each been recapitulated in either amyloid or tau transgenic models, only a few studies have successfully yielded a system in which the relationship between amyloid and tau could be examined within the same model. In 2001, two critical studies were published supporting the role of amyloid in AD pathogenesis. Intercrossing the Tg2576 model of amyloidosis with the JNPL3 mouse model of tauopathy demonstrated that high levels of APP or Aβ could enhance tauopathy (Figure 1) [71]. In a parallel publication, intracerebral injection of Aβ42 into the P301L tau transgenic strain pR5 [72] resulted in similar findings that could be directly attributed to Aβ42. Most recently, tangle formation was aggravated by infusing brain extracts of aged APP23 mice intracerebrally in JNPL3 mice or by crossing APP23 and JNPL3 mice [73]. Additional mouse models have now been created combining aspects of both amyloidosis and tauopathy including the dual expression of APPSwe and P301L tau on a PSEN1M146V/- background in the 3xTg-AD mice [71,72,74], and the regulatable transgenic mouse model rTg3696AB expressing both APP with the Swedish and London (V717I) mutations and P301L tau driven by the CaMKII promoter system [75]. While these models have largely been utilized to investigate that impact of Aβ on tauopathy, a groundbreaking study was reported in 2007, which demonstrated that reduction of endogenous tau ameliorated Aβ-induced deficits in an APP transgenic mice (Figure 1) [76]. This was achieved by crossing the J20 line onto hetero- and homozygous tau-knockout background. Tau reduction also protected both transgenic and nontransgenic mice against the GABAA receptor antagonist pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-mediated excitotoxicity. The results suggest that Aβ toxicity is tau dependent (Figure 1). Although crosstalk between Aβ and tau was confirmed in these mouse models, it is still unclear which forms of Aβ are related to the NFT formation and how Aβ and/or APP processing derivatives contribute to the hyperphosphorylation of tau leading to tau aggregation.

Conclusion

Previous mouse models of AD have been developed to reproduce crucial features of the disease such as amyloid plaques, NFTs, cognitive degeneration, atrophy and neuronal loss. While the APP single transgenic mouse models develop neither NFT nor exhibit massive neuronal loss, studies in mice expressing both mutant APP and tau clearly replicate the main pathological hallmarks of AD. Some researchers in the field debate the significance of these models since these models employ several strategies that do not represent ‘true’ AD in aggregate. To appreciate the validity of such an argument, one must realize that we are seeking to recreate a human disease that normally requires decades to develop by manipulating an animal that lives for a mere 2 years. Given this, it is not surprising that such strategies are needed to yield these essential research animals. For example, amyloidosis is generally modeled in these transgenic mice by the expression of APP containing FAD mutations, which account for less than 1% of the total number of AD cases. Rapidly progressing, mature tauopathy has only been modeled in transgenic mice expressing tau with a mutation associated with FTDP-17. In addition, most of the tau models have relied on high levels of expression and a single isoform of human tau to drive tauopathy, each of which has been suggested by some experts in the field as being physiologically irrelevant. Most mouse models of tauopathy have not accurately reproduced the age-dependent, anatomical distribution of the lesions starting in the trans-entorhinal cortex in human brain according to Braak NFT staging. Each of these issues is something that should be appreciated when using tau and amyloid model systems; however, simply dismissing the utility of these animal models may be a mistake. Interestingly, cell lines (i.e., M17 and N2a cells), which are routinely utilized for the study of AD and other neurodegenerative disease have similar, if not more extreme, deviation from normal physiology, yet those models have been embraced by the field as essential research tools.

Future perspective

There are a number of techniques that may improve our ability to assess current mouse model systems in a more clinically appropriate manner. These techniques should be more readily applied so that the field can move past the end stage neuropathological hallmarks such as amyloid plaques and NFT in order to address the earliest features of the disease. In addition, AAV can now be employed to refine our understanding of the interplay between tau and Aβ as well as their interaction with other proteins.

Validation for Alzheimer's disease models

While neuropathologically characterized by amyloid and tau pathologies, AD is clinically characterized by early memory deficits, followed by the gradual erosion of other cognitive functions. In order to evaluate clinical aspects in mouse models of AD, researchers have employed behavioral studies such as the Morris water maze (MWM) test [77]. Although there are some disadvantages and limitations [78], the MWM allows assessment of spatial learning and memory in transgenic mice in relation to progression of disease or therapeutic trials. Partnering of such behavioral tests with more technologically sophisticated measures of pathology and brain functioning may enhance our ability to validate and utilize disease models. Imaging techniques, such as PET, MRI and multiphoton imaging, have been recently applied for the visualization of Aβ deposition in transgenic mouse brains. The PET tracer 11C-labeled Pittsburgh Compound-B (PIB) was used in APP23 mice to show an age-dependent increase in radioligand binding in parallel with progressive Aβ accumulation [79]. There are several limitations of PET, including a high variability in normal controls, low spatial resolution and long scanning periods. In contrast to visualizing pathological structures, manganese-enhanced MRI (Mn-enhanced MRI) was newly developed to assess neural activity of the mouse brain responding to novel environments [80]. As manganese enters into neurons through calcium channels and accumulates in neurons, positive magnetic resonance signals can be detected to show active regions of the brain during behavior to be sampled with MRI [81,82]. Kimura et al. observed that the activity of the parahippocampal area in aged (20–24 months old) transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type human 4R tau isoform (termed Wtau-transgenic) was strongly correlated with the decline in memory as assessed by the MWM test. As the entorhinal and hippocampal circuit is essential for the formation of place memory, it is quite reasonable to show reduced neural activity in perirhinal, lateral and medial entorhinal cortices of aged Wtau transgenic mice. In the future, these imaging techniques will be able to provide high spatial resolution that is compatible with the size of mouse brain structure. Overall, combining behavioral and imaging techniques may lead to better clinical and pathological staging of AD mouse models, both in the context of disease development and in therapeutic trials.

Somatic brain transgenesis

Recent advances in molecular biology have made it possible to investigate neurological disorders at the molecular and genetic level. The use of viral vectors as agents for gene delivery provides a direct approach to manipulate gene expression in the mammalian CNS. Most of the vector systems used in the early days of gene therapy research, for example, herpesvirus and adenoviral vectors, suffered from immunogenicity and direct neuronal toxicity. Recently, the development of AAV vectors has conquered these problems [83]. Direct injection of AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) vector into the brain [84] appears to be nontoxic and results in the persistent transduction of neural tissue, preferentially in neurons [85]. The performance of different types of AAV vector appears to be tissue-dependent and probably related to the abundance of serotype-specific AAV receptor. Passini et al. reported that widespread gene delivery can be achieved by injecting an AAV serotype 1 (AAV1) vector directly into the cerebral lateral ventricles at birth on postnatal day 0, and allowing the cerebrospinal fluid to deliver the virus throughout the CNS [86]. Based on this newly established technology (termed as somatic brain transgenesis [SBT]), Levites et al. generated AAV1 vectors encoding anti-Aβ single-chain variable fragments (scFvs), which were then injected into the ventricles of postnatal day 0 TgCRND8 mice [87]. This strategy allowed complete prevention of pathology in all areas of the TgCRND8 mouse brain for at least 1 year, suggesting stable expression of the delivered transgene for the lifetime of the animal [87]. Previously, Lawlor et al. examined AAV-mediated gene transfer of BRI-Aβ40, BRI-Aβ42 and APPSwe into the hippocampi of adult rats to define the contribution of Aβ peptide itself [88]. AAV-BRI Aβ40 and Aβ42 transduction can be used in established mouse models of tauopathy such as the Htau mice or rTg4510 mice to determine the impact of Aβ peptide on the development of NFT, neuronal loss and cognitive impairment. In the future, SBT technology should allow us to design cost- and time-effective experimental strategies to refine our understanding of the interaction between tau and Aβ as well as with other proteins.

Transduction knockout technique with AAV-Cre

Inactivating genes in vivo is an important technique for establishing their function in the adult CNS. However, conventional null mutations of genes that have important functions during development often show an embryonic lethal phenotype, such as PSEN, making experiments on adult animals impossible. The Cre–loxP system is well suited for this problem because it can be used to produce conditional gene deletions in particular cell types at specific times [89,90]. Cre recombinase catalyzes recombination between short loxP sequences, thus deleting any sequence flanked by loxP sites [91]. Recently, as described previously, AAV vectors provide a useful tool to mediate delivery and stable transduction of genes to the brain. Injection of AAV–Cre, which is now commercially available, into the specific brain region of the mice with loxP-flanked genes of interest will cause region-specific recombination. Using this technique, for example, Scammell et al. reported that focal deletion of the adenosine A1 receptor in the hippocampus of AAV-Cre injected inducible A1R-knockout mice induced local expression of Cre and a marked decrease in A1R mRNA [92]. They observed that deletion of A1 receptor CA3 neurons abolished the postsynaptic response to adenosine, but deletion of A1 receptors from CA1 neurons had no effect, demonstrating a presynaptic site of action. Park et al. also reported that deletion of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in adult retinal ganglion cells of AAV-Cre injected PTENf/f mice promotes robust axon regeneration after optic nerve injury [93]. This experimental approach will provide novel mouse modeling in the AD research field, as well as wide applicability in neuroscience.

Executive summary.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis

A refined hypothesis now posits that soluble amyloid β (Aβ) oligomers rather than Aβ deposits primarily contribute to synaptic dysfunction, neuronal death, neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) formation and memory impairment in Alzheimer's disease (AD).

The extent of NFTs correlates with the progression of dementia.

Mouse modeling for amyloidosis

Several transgenic mouse lines overexpressing human amyloid precursor protein (APP) with familial AD (FAD) mutations were successfully developed to exhibit extracellular Aβ plaques of varying morphology.

The transgenic mouse expressing BRI-Aβ42 fusion developed considerable amyloid plaque pathology suggesting that overproduction of Aβ42; however, mice expressing BRI-Aβ40 did not.

Mouse modeling for tauopathy

Htau mice expressing wild-type human tau successfully replicated tauopathy.

The rTg4510 mouse model was developed in order to generate a model with significant forebrain tauopathy including mature NFT formation, neuronal loss and cognitive dysfunction.

Suppression of P301L tau expression in rTg4510 mice reversed behavioral impairments although NFTs continued to increase suggesting that NFTs might not be the initial neurotoxic species.

Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic ALZ17 mice expressing wild-type tau was observed after injection of brain extract from mutant P301S tau transgenic mice.

Mouse modeling for Alzheimer's disease

Studies in mice expressing both mutant APP and mutant tau replicate the main pathological hallmarks of AD.

Impact of Aβ and/or APP on enhanced tauopathy was confirmed by several mouse models.

Reduction of endogenous tau ameliorated Aβ-induced deficits in APP transgenic mice.

Future perspective

Early diagnosis of AD is essential in humans and therefore in the mouse models mimicking the disease. Early behavioral analyses and brain imaging techniques should improve the assessment of preclinical stages in existing and future mouse models.

The use of adenovirus (AAV) technology provides a direct approach to manipulating gene expression in the mouse brain.

The recently established technology of somatic brain transgenesis will refine our understanding of the interaction between tau and Aβ, as well as with other proteins.

The transduction knockout technique with AAV-Cre also provides a novel mouse modeling strategy in AD with brain regional specific gene recombination.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure: Jada Lewis is the inventor of the JNPL3 rTg4510 mouse models of tauopathy and has received royalties from the licensing of these technologies of greater than the federal threshold for significant financial interest. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Alzheimer A, Stelzmann RA, Schnitzlein HN, Murtagh FR. An English translation of Alzheimer's 1907 paper, ‘Uber eine eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde’. Clinical Anatomy. 1995;8(6):429–431. doi: 10.1002/ca.980080612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertram L, Tanzi RE. The genetic epidemiology of neurodegenerative disease. J Clin Investig. 2005;115(6):1449–1457. doi: 10.1172/JCI24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261(5123):921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43(8):1467–1472. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, et al. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393(6686):702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, et al. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43(6):815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(13):7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1991;6(4):487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298(5594):789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selkoe DJ. Soluble oligomers of the amyloid β-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192(1):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckert A, Hauptmann S, Scherping I, et al. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of β-amyloid (Aβ 42) both impair mitochondrial function in P301L tau transgenic mice. J Mol Med. 2008;86(11):1255–1267. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minkeviciene R, Rheims S, Dobszay MB, et al. Amyloid β-induced neuronal hyperexcitability triggers progressive epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2009;29(11):3453–3462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5215-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Aβ42 immunization. Neurology. 2003;61(1):46–54. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073623.84147.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, et al. Long-term effects of Aβ42 immunisation in Alzheimer's disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled Phase I trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9634):216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holtzman DM. Alzheimer's disease: moving towards a vaccine. Nature. 2008;454(7203):418–420. doi: 10.1038/454418a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathologica. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braak H, Braak E. Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;165:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb05866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(4):351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steiner H, Haass C. Intramembrane proteolysis by presenilins. Nat Rev. 2000;1(3):217–224. doi: 10.1038/35043065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younkin SG. The role of Apβ 42 in Alzheimer's disease. J Physiol. 1998;92(3–4):289–292. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(98)80035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fryer JD, Holtzman DM. The bad seed in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2005;47(2):167–168. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goate A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Mullan M, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1991;349(6311):704–706. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goedert M, Spillantini MG. A century of Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2006;314(5800):777–781. doi: 10.1126/science.1132814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, et al. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1998;391(6665):387–390. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe MS, Xia W, Ostaszewski BL, Diehl TS, Kimberly WT, Selkoe DJ. Two transmembrane aspartates in presenilin-1 required for presenilin endoproteolysis and gamma-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;398(6727):513–517. doi: 10.1038/19077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borchelt DR, Thinakaran G, Eckman CB, et al. Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Aβ1–42/1–40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron. 1996;17(5):1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duff K, Eckman C, Zehr C, et al. Increased amyloid-β42(43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1. Nature. 1996;383(6602):710–713. doi: 10.1038/383710a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borchelt DR, Ratovitski T, van Lare J, et al. Accelerated amyloid deposition in the brains of transgenic mice coexpressing mutant presenilin 1 and amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron. 1997;19(4):939–945. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bentahir M, Nyabi O, Verhamme J, et al. Presenilin clinical mutations can affect gamma-secretase activity by different mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2006;96(3):732–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar-Singh S, Theuns J, Van Broeck B, et al. Mean age-of-onset of familial alzheimer disease caused by presenilin mutations correlates with both increased Aβ42 and decreased Aβ40. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(7):686–695. doi: 10.1002/humu.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Jonghe C, Esselens C, Kumar-Singh S, et al. Pathogenic APP mutations near the gamma-secretase cleavage site differentially affect Aβ secretion and APP C-terminal fragment stability. Hum Mol Gen. 2001;10(16):1665–1671. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimojo M, Sahara N, Murayama M, Ichinose H, Takashima A. Decreased Aβ secretion by cells expressing familial Alzheimer's disease-linked mutant presenilin 1. Neurosci Res. 2007;57(3):446–453. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimojo M, Sahara N, Mizoroki T, et al. Enzymatic characteristics of I213T mutant presenilin-1/γ-secretase in cell models and knock-in mouse brains: familial Alzheimer disease-linked mutation impairs γ-site cleavage of amyloid precursor protein C-terminal fragment β. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(24):16488–16496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasegawa K, Yamaguchi I, Omata S, Gejyo F, Naiki H. Interaction between Aβ(1–42) and A β(1–40) in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Biochemistry. 1999;38(47):15514–15521. doi: 10.1021/bi991161m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snyder SW, Ladror US, Wade WS, et al. Amyloid-β aggregation: selective inhibition of aggregation in mixtures of amyloid with different chain lengths. Biophysical J. 1994;67(3):1216–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80591-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou K, Kim D, Kakio A, et al. Amyloid β-protein (Aβ)1–40 protects neurons from damage induced by Aβ1–42 in culture and in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2003;87(3):609–619. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan Y, Wang C. Aβ40 protects non-toxic Aβ42 monomer from aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2007;369(4):909–916. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu GQ, et al. High-level neuronal expression of aβ 1–42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2000;20(11):4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Games D, Adams D, Alessandrini R, et al. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1995;373(6514):523–527. doi: 10.1038/373523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪ Describes one of the most utilized mouse models of amyloidosis.

- 43.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274(5284):99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪ Describes one of the most utilized mouse models of amyloidosis.

- 44.Sturchler-Pierrat C, Abramowski D, Duke M, et al. Two amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models with Alzheimer disease-like pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(24):13287–13292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calhoun ME, Burgermeister P, Phinney AL, et al. Neuronal overexpression of mutant amyloid precursor protein results in prominent deposition of cerebrovascular amyloid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(24):14088–14093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, et al. Aβ peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):979–982. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim J, Onstead L, Randle S, et al. Aβ40 inhibits amyloid deposition in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27(3):627–633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4849-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stokin GB, Almenar-Queralt A, Gunawardena S, et al. Amyloid precursor protein-induced axonopathies are independent of amyloid-β peptides. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(22):3474–3486. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ballatore C, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. Nat Rev. 2007;8(9):663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrn2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kosik KS, Orecchio LD, Binder L, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Lee G. Epitopes that span the tau molecule are shared with paired helical filaments. Neuron. 1988;1(9):817–825. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wischik CM, Novak M, Thogersen HC, et al. Isolation of a fragment of tau derived from the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(12):4506–4510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kondo J, Honda T, Mori H, et al. The carboxyl third of tau is tightly bound to paired helical filaments. Neuron. 1988;1(9):827–834. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee VM, Balin BJ, Otvos L, Jr, Trojanowski JQ. A68: a major subunit of paired helical filaments and derivatized forms of normal Tau. Science. 1991;251(4994):675–678. doi: 10.1126/science.1899488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goedert M, Wischik CM, Crowther RA, Walker JE, Klug A. Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: identification as the microtubule-associated protein tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(11):4051–4055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gomez-Isla T, Hollister R, West H, et al. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41(1):17–24. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ihara Y. PHF and PHF-like fibrils – cause or consequence? Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22(1):123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gotz J, Probst A, Spillantini MG, et al. Somatodendritic localization and hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in transgenic mice expressing the longest human brain tau isoform. EMBO J. 1995;14(7):1304–1313. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andorfer C, Kress Y, Espinoza M, et al. Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau in mice expressing normal human tau isoforms. J Neurochem. 2003;86(3):582–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪ Describes a transgenic mouse model of mature tauopathy resulting from wild-type tau.

- 59.Andorfer C, Acker CM, Kress Y, Hof PR, Duff K, Davies P. Cell-cycle reentry and cell death in transgenic mice expressing nonmutant human tau isoforms. J Neurosci. 2005;25(22):5446–5454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4637-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J, et al. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat Genet. 2000;25(4):402–405. doi: 10.1038/78078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gotz J, Chen F, Barmettler R, Nitsch RM. Tau filament formation in transgenic mice expressing P301L tau. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(1):529–534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanemura K, Akagi T, Murayama M, et al. Formation of filamentous tau aggregations in transgenic mice expressing V337M human tau. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8(6):1036–1045. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tatebayashi Y, Miyasaka T, Chui DH, et al. Tau filament formation and associative memory deficit in aged mice expressing mutant (R406W) human tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(21):13896–13901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202205599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Allen B, Ingram E, Takao M, et al. Abundant tau filaments and nonapoptotic neurodegeneration in transgenic mice expressing human P301S tau protein. J Neurosci. 2002;22(21):9340–9351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09340.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schindowski K, Bretteville A, Leroy K, et al. Alzheimer's disease-like tau neuropathology leads to memory deficits and loss of functional synapses in a novel mutated tau transgenic mouse without any motor deficits. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(2):599–616. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, et al. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron. 2007;53(3):337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eckermann K, Mocanu MM, Khlistunova I, et al. The β-propensity of Tau determines aggregation and synaptic loss in inducible mouse models of tauopathy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(43):31755–31765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705282200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, et al. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science. 2005;309(5733):476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪▪ Provides data in a regulatable mouse model of tauopathy that neurofibrillary tangles are not the initial toxic species in tauopathy.

- 69.Spires TL, Orne JD, SantaCruz K, et al. Region-specific dissociation of neuronal loss and neurofibrillary pathology in a mouse model of tauopathy. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(5):1598–1607. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, et al. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(7):909–913. doi: 10.1038/ncb1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪▪ Provides in vivo evidence suggesting that tauopathy may be able to spread through a prion-like mechanism.

- 71.Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin WL, et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293(5534):1487–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gotz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Aβ 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293(5534):1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bolmont T, Clavaguera F, Meyer-Luehmann M, et al. Induction of tau pathology by intracerebral infusion of amyloid-β-containing brain extract and by amyloid-β deposition in APP × Tau transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(6):2012–2020. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Aβ and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39(3):409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paulson JB, Ramsden M, Forster C, Sherman MA, McGowan E, Ashe KH. Amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangle pathology in a regulatable mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(3):762–772. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪▪ Reports the first mouse model in which tau and amyloid are both regulatable.

- 76.Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid β-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316(5825):750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪▪ Provides in vivo evidence that tau may influence amyloid.

- 77.Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.D'Hooge R, De Deyn PP. Applications of the Morris water maze in the study of learning and memory. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36(1):60–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maeda J, Ji B, Irie T, et al. Longitudinal, quantitative assessment of amyloid, neuroinflammation, and anti-amyloid treatment in a living mouse model of Alzheimer's disease enabled by positron emission tomography. J Neurosci. 2007;27(41):10957–10968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0673-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kimura T, Yamashita S, Fukuda T, et al. Hyperphosphorylated tau in parahippocampal cortex impairs place learning in aged mice expressing wild-type human tau. EMBO J. 2007;26(24):5143–5152. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wadghiri YZ, Blind JA, Duan X, et al. Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) of mouse brain development. NMR Biomedicine. 2004;17(8):613–619. doi: 10.1002/nbm.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yu X, Wadghiri YZ, Sanes DH, Turnbull DH. In vivo auditory brain mapping in mice with Mn-enhanced MRI. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(7):961–968. doi: 10.1038/nn1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ruitenberg MJ, Eggers R, Boer GJ, Verhaagen J. Adeno-associated viral vectors as agents for gene delivery: application in disorders and trauma of the central nervous system. Methods. 2002;28(2):182–194. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McCown TJ, Xiao X, Li J, Breese GR, Samulski RJ. Differential and persistent expression patterns of CNS gene transfer by an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector. Brain Res. 1996;713(1–2):99–107. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ, McCown TJ. Selective and rapid uptake of adeno-associated virus type 2 in brain. Human Gene Therapy. 1998;9(8):1181–1186. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.8-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Passini MA, Watson DJ, Vite CH, Landsburg DJ, Feigenbaum AL, Wolfe JH. Intraventricular brain injection of adeno-associated virus type 1 (AAV1) in neonatal mice results in complementary patterns of neuronal transduction to AAV2 and total long-term correction of storage lesions in the brains of β-glucuronidase-deficient mice. J Virol. 2003;77(12):7034–7040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.7034-7040.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Levites Y, Jansen K, Smithson LA, et al. Intracranial adeno-associated virus-mediated delivery of anti-pan amyloid β, amyloid β40, and amyloid β42 single-chain variable fragments attenuates plaque pathology in amyloid precursor protein mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26(46):11923–11928. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2795-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lawlor PA, Bland RJ, Das P, et al. Novel rat Alzheimer's disease models based on AAV-mediated gene transfer to selectively increase hippocampal Aβ levels. Mol Neurodegen. 2007;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gu H, Marth JD, Orban PC, Mossmann H, Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase β gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265(5168):103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tsien JZ, Chen DF, Gerber D, et al. Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell. 1996;87(7):1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sauer B, Henderson N. Site-specific DNA recombination in mammalian cells by the Cre recombinase of bacteriophage P1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(14):5166–5170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Scammell TE, Arrigoni E, Thompson MA, Ronan PJ, Saper CB, Greene RW. Focal deletion of the adenosine A1 receptor in adult mice using an adeno-associated viral vector. J Neurosci. 2003;23(13):5762–5770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05762.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Park KK, Liu K, Hu Y, et al. Promoting axon regeneration in the adult CNS by modulation of the PTEN/mTOR pathway. Science. 2008;322(5903):963–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1161566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Website

- 101.Alzheimer's association. www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_what_is_alzheimers.asp.