Abstract

Summary: BigWig and BigBed files are compressed binary indexed files containing data at several resolutions that allow the high-performance display of next-generation sequencing experiment results in the UCSC Genome Browser. The visualization is implemented using a multi-layered software approach that takes advantage of specific capabilities of web-based protocols and Linux and UNIX operating systems files, R trees and various indexing and compression tricks. As a result, only the data needed to support the current browser view is transmitted rather than the entire file, enabling fast remote access to large distributed data sets.

Availability and implementation: Binaries for the BigWig and BigBed creation and parsing utilities may be downloaded at http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/admin/exe/linux.x86_64/. Source code for the creation and visualization software is freely available for non-commercial use at http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/admin/jksrc.zip, implemented in C and supported on Linux. The UCSC Genome Browser is available at http://genome.ucsc.edu

Contact: ann@soe.ucsc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary byte-level details of the BigWig and BigBed file formats are available at Bioinformatics online. For an in-depth description of UCSC data file formats and custom tracks, see http://genome.ucsc.edu/FAQ/FAQformat.html and http://genome.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/help/hgTracksHelp.html

1 INTRODUCTION

Recent improvements in sequencing technologies have made it possible for labs to generate terabyte-sized genomic data sets. Visualization of these data sets is a key to scientific interpretation. Typically, loading the data into a visualization tool such as the Genome Browser provided by the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) (Kent et al., 2002; Rhead et al., 2010) has been difficult. The data can be loaded as a ‘custom annotation track’, but for very large data sets the upload form times out before the data transfer finishes. To work around this limitation, some labs with access to Solexa and later-generation sequencing machines have installed a local copy of the Genome Browser, but this requires a significant initial time investment by systems administrators and other informatics professionals, as well as continuing efforts to keep the data in the local browser installation current.

Though visualization of results is just one of the many informatics challenges of next-generation sequencing, it is one that we are well positioned to address at UCSC. We have developed two new data formats, BigWig and BigBed, that make it practical to view the results of next-generation sequencing experiments as tracks in the UCSC Genome Browser. The BigWig and BigBed files are compressed binary indexed files that contain the data at several resolutions. Rather than transmitting the entire file, only the data needed to support the current view in the Genome Browser are transmitted. Collectively, BigWig and BigBed are referred to as Big Binary Indexed (BBI) files.

2 SYSTEM AND METHODS

BigBed files are generated from Browser Extensible Data (BED) files. Like the BED format, the BigBed format is used for data tables with a varying number of fields. BED files consist of a simple text format: each line contains the fields for one record, separated by white space. The first three fields are required, and must contain the chromosome name, start position and end position. The standard BED format defines nine additional, optional fields, which (if present) must appear in the predefined order (Supplementary Table 1). Alternatively, BED files may depart from the standard format after the third field, continuing with fields specific to the application and data set. BigBed files that contain custom fields, unlike those of simple BED format, must also contain the field name and a sentence describing the custom field. To help others understand custom BED fields, an autoSql (.as) (Kent and Brumbaugh, 2002) declaration of the table format can be included in the BigBed file (Supplementary Table 2).

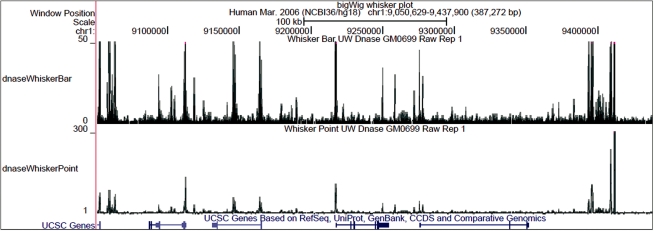

BigWig files are derived from text-formatted wiggle plot (wig) or bedGraph files. They associate a floating point number with each base in the genome, and can accommodate missing data points. In the UCSC Genome Browser, these files are used to create graphs in which the horizontal axis is the position along a chromosome and the vertical axis is the floating point data (Fig. 1). Typically, these graphs are represented by a wiggly line, hence the name ‘wiggle’. Three text formats can be used to describe wiggle data at varying levels of conciseness and flexibility. Values may be specified for every base or for regularly spaced fixed-sized windows using the ‘fixedStep’ format. The ‘variableStep’ format encodes fixed-sized windows that are variably spaced. The ‘bedGraph’ format encodes windows that are both variably sized and variably spaced.

Fig. 1.

Genome Browser image of BigWig annotation tracks. The top track is displayed as a bar graph, the bottom track as a point graph. Shading is used to distinguish the mean (dark), one standard deviation above the mean (medium) and the maximum (light). Peaks with clipped tops are colored magenta.

Data files of fixedStep format are divided into sections, each of which starts with a line of the form:

fixedStep chrom=chrN start=position step=N span=N

where ‘chrom’ is the chromosome name, ‘start’ is the start position on the chromosome, ‘step’ is the number of bases between items and ‘span’ shows the number of bases covered by each item. Step and span default to 1 if they are not defined. This section line is followed by a line containing a single floating point number for each item in the section.

The variableStep format is similar, but the section starts with a line of the format:

variableStep chrom=chrN span=N

and each item line contains two fields: the chromosome start position, and the floating point value associated with each base.

The bedGraph format is a BED variant in which the fourth column is a floating point value that is associated with all the bases between the chromStart and chromEnd positions. Unlike the zero-based BED and bedGraph, for compatibility reasons the chromosome start positions in variableStep and fixedStep are one-based.

To create a BigBed or BigWig file, one first creates a text file in BED, fixedStep, variableStep or bedGraph format and then uses the bedToBigBed, wigToBigWig or bedGraphToBigWig command-line utility to convert the file to indexed binary format. In addition to the text file and (in the case of BigBed) the optional .as file, the conversion utilities require a chrom.sizes input file that describes the chromosome (or contig) sizes in a two-column format (chromosome name, chromosome size). The fetchChromSizes program may be used to obtain the chrom.sizes file for any genome hosted at UCSC. All of the command-line utilities can be run without options to display a usage summary.

The wigToBigWig program accepts fixedStep, variableStep or bedGraph input. The bedGraphToBigWig program accepts only bedGraph files, but has the advantage of using much less memory. The wigToBigWig program can take up to 1.5 times as much memory as the wig file it is encoding, while bedGraphToBigWig and bedToBigBed use only about one-quarter as much memory as the size of the input file.

Once a BigBed or BigWig file is created, it can be viewed in the UCSC Genome Browser by using the custom track mechanism (Supplementary Material). In brief the indexed file is put on a website accessible via HTTP, HTTPS or FTP, and a line describing the file type and data location in the form:

track type=bigBed bigDataUrl=http://srvr/myData.bb

is entered in the custom track section of the browser. Additional settings in var = value format can be used to control the name, color, and other attributes of the track. When the custom track is loaded and displayed, the Genome Browser fetches only the data it needs to display at the resolution appropriate for the size of the region being viewed. While it may take a few minutes to convert the input text file to the indexed format, once this is done there is no need to upload the entire file, and the response time on the browser is nearly as fast as if the file resided on the local UCSC server.

Because the BigWig and BigBed files are binary, we have created additional tools that parse the files and describe the contents. The bigWigSummary and bigBedSummary programs can quickly compute summaries of large sections of the files corresponding to zoomed-out views in the Genome Browser. The bigWigInfo and bigBedInfo can be used to quickly check the version numbers, compression status and data ranges stored in a file. The bigBedToBed, bigWigToWig and bigWigToBedGraph programs can convert all or just a portion of files back to text format.

3 IMPLEMENTATION

The BigBed and BigWig readers and writers are written in portable C; other programs that can interface with C libraries can make use of the code directly. For those working in languages that do not interface well with C, the Supplemental Information describes the file format in sufficient detail to reimplement it in another language. Several layers of software are involved in enabling the remote access of the BigBed and BigWig files. This section describes the software architecture, algorithms and data structures at a high level, and should be useful to anyone trying to understand the code enough to usefully modify it or to implement similar file formats that work well in a distributed data environment.

3.1 Data transfer layer

Though BigBed and BigWig can be used locally, the primary design goal for this format was to enable efficient remote access. This is done using existing web-based protocols that are generally already available at most sites. Unlike typical web use, bigBed and bigWig files require random access. At the lowest layer, we take advantage of the byte-range protocols of HTTP and HTTPS, and the protocols associated with resuming interrupted FTP transfers, to achieve random access to binary files over the web. Web servers supporting HTTP/1.1 accept byte-ranges when the data is non-volatile. OpenSSL provides SSL support for HTTPS via the BIO protocol. FTP uses the resume command and simply closes the connection when sufficient data has been read.

3.2 URL data cache layer

Since remote access is still slow compared to local access, and data files typically are viewed many times without changing, we implemented a cache layer on top of the data transfer layer. Data are fetched in blocks of 8 Kb, and each block is kept in a cache. The cache is implemented using two files for each file that is cached: a bitmap file that has a bit set for each file block in cache and a data file that contains the actual blocks of data. The data file is implemented very simply using the sparse file feature of Linux and most other UNIX-like operating systems. The cache software simply seeks to the position in the file where the block belongs and writes it. The operating system allocates disk space only for the parts of the file that are actually written.

The cache layer is critical to performance. Parts of the file, including the file header and the root block of the index, are accessed no matter what part of the genome is being viewed. These parts need be transmitted only once. In addition if multiple users view the same region of the genome, later users will benefit from the cache, as will a single user looking at the same region multiple times.

Though a cache can help convert remote access to local access, a minimum of one remote access—to check whether the file has changed at the remote site—is required even on a completely cached file. Minimizing the number of cache checks is one of the motivations for keeping the index and the zoomed data in the same file as the primary data. Even though a change check involves little in the way of data transfer, it does require a round trip on the network, which can take from 10 to 1000 ms depending on the network connectivity. For similar reasons, though data are always fetched at least one full block at a time, the system will combine multiple blocks into a single fetch operation whenever possible.

3.3 Indexing

The next layer handles the indexing. It is based on a single dimensional version of the R tree that is commonly used for indexing geographical data. The index size is typically less than 1% of the size of the data itself.

A BigBed file can contain overlapping intervals. Overlapping intervals are not as easy to index as strings, points or non-overlapping intervals, but several effective techniques do exist, including binning schemes (Kent et al., 2002), nested containment lists (Alekseyenko and Lee, 2007) and R trees (Guttman, 1984). R trees have several properties that make them attractive for this application. They perform well for data at a variety of scales in contrast to binning schemes that typically have a ‘sweet spot’ at a particular scale of data close to the smallest bin size. R trees also minimize the number of seeks (and hence network roundtrips) compared to nested containment lists, another popular genomics indexing scheme.

The basic idea behind an R tree is fairly simple. Each node of the tree can point to multiple child nodes. The area spanned by a child node is stored alongside the child pointer. The reader starts with the root node, and descends into all nodes that overlap the query window. Since most child nodes do not overlap, only a few branches of the tree need to be explored for a typical query.

Though a separate R tree for each chromosome would have been simpler to implement, we elected to use a single tree in which the comparison operator includes both the chromosome and the position. This allows better performance on roughly assembled genomes with hundreds or thousands of scaffolds, and also lets the files be applied to RNA as well as DNA databases. To improve the efficiency of the single R tree, we store the chromosome ID as an integer rather than a name, and include a B+ tree to associate chromosome names and IDs in the file. In the source code, the combined B+ tree and R tree index is referred to as a cirTree.

One additional indexing trick is used. Because the stored data are sorted by chromosome and start position, not every item in the file must be indexed; in fact by default only every 512th item is indexed. The software finds the closest indexed item preceding the query, and then scans through the data, discarding some of the initial items if necessary. This may seem wasteful, since hundreds of thousands of bytes may be transferred in the same time that it takes to seek to a new position on disk, but in practice little time is lost and as a benefit the index is less than 1% of the size of the data.

3.4 Compression

The data regions of the file (but not the index) are compressed using the same deflate techniques that are used in gzip as implemented in the zlib library, a very widespread, stable and fast library built into most Linux and UNIX installations. The compression would not be very efficient if each item was compressed separately, and it would not support random access if the entire data area were compressed all at once. Instead the regions between indexed items (containing 512 items by default) are individually compressed. This maintains the same degree of random accessibility that was enabled by the sparse R tree index while still achieving nearly the same level of compression as compressing the entire file would.

The final layer of software is responsible for fetching and decoding blocks specified by the index. It is only this final layer that differs between BigWig and BigBed.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The BigBed and BigWig files succeed in overcoming browser upload timeout limits. By deferring the bulk of the data transfer to be on demand, the upload phase of BigWig and BigBed files now takes less than a second even on home and remote networks, well within the 300-s upload time limit at UCSC. The on-demand connectivity requirements are modest, adding 0.5–1.0 s of data transfer time overhead depending on where the Big file is hosted (Supplementary Table 3).

BigBed and BigWig files are similar in many ways to BAM files (Li et al., 2009), which are commonly used to store mappings of short reads to the genome. BAM files are also binary, compressed, indexed versions of an existing text format, SAM. The samtools C library associated with SAM and BAM (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/) caches the BAM index, though not the data files. Samtools also can fetch data from the internet via FTP and HTTP, but not HTTPS. BAM files are not designed for wiggle graphs, and are more complex than BED files, but they do store alignment, sequence and sequence quality information very efficiently. While this capability theoretically could be added as an extension to BigBed, we have adopted BAM for short read mapping to avoid a proliferation of formats. BAM files are supported as custom tracks at UCSC, and we have added HTTPS support to BAM using the data transfer and data cache layers developed for BigBed and BigWig.

BigBed and BigWig files have been in use at genome.ucsc.edu since June 2009, and have proven to be popular. As of February 2010, we have displayed data from nearly 1300 files using these formats. The broader bioinformatics community has started to support these files as well, with Perl bindings available at http://search.cpan.org/∼lds/Bio-BigFile/ and a Java implementation in progress (Martin Deacutis, personal communication) for use in the Integrative Genome Viewer (http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/). Though the use of BigBed and BigWig requires access to the command line creation tools needed to create the files and a website or FTP site on which to place them, this is not an undue burden in the context of the informatics demands of a modern sequencing pipeline, and is clearly preferable to the long and uncertain uploads of large custom tracks in text formats.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge James Taylor, Heng Li and Martin Deacutis for their testing and feedback on these formats, and Lincoln Stein for developing the Perl bindings.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (5P41HG002371-09, 5U41HG004568-02). The open access charge was funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Alekseyenko AV, Lee CJ. Nested containment list (NCList): a new algorithm for accelerating interval query of genome alignment and interval databases. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1386–1393. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman A. R-Trees: a dynamic index structure for spatial searching. Proceedings of 1984 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data. 1984:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Brumbaugh H. autoSql and autoXml: code generators from the Genome Project. Linux J. 2002;99:68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhead B, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: update 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D613–D619. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.