Abstract

BACKGROUND

Work environment attributes - job design, teamwork, work effectiveness - are thought to influence nursing home (NH) quality of care. However, few studies tested these relationships empirically.

OBJECTIVE

We investigated the relationship between these work environment attributes and quality of care measured by facility-level regulatory deficiencies.

METHODS

Data on work environment were derived from survey responses obtained (in 2006-2007) from 7,418 direct care workers in 162 NHs in NYS. Data on facility deficiencies and characteristics came from the OSCAR database.

We fit multivariate linear and logistic regressions, with random effects and probability weights, to models with the following dependent variables: presence/absence of quality of life (QL) deficiencies; number of quality of care (QC) deficiencies; and presence/absence of high severity G-L deficiencies (causing actual harm/immediate jeopardy). Key independent variables included: work effectiveness (a 5-point Likert scale score); percent staff in daily care teams and with primary assignment. The work effectiveness measure has been demonstrated to be psychometrically reliable and valid. Other variables included staffing, size, facility case-mix, and ownership.

RESULTS

In support of the proposed hypotheses, we found work effectiveness to be a statistically significant predictor of all three measures of deficiencies. Primary assignment of staff to residents was significantly associated with fewer QC and high severity deficiencies. Greater penetration of self-managed teams was associated with fewer QC deficiencies.

DISCUSSION

Work environment attributes impact quality of care in NHs. These findings provide important insights for NH administrators and regulators in their efforts to improve quality of care for residents.

INTRODUCTION

Quality of care in US nursing homes (NH) has been an on-going concern. In 2007 ~114,600 deficiencies were issued to Medicare/Medicaid certified facilities for violations of federal regulations; on average, 7.5 deficiencies per NH.(1) Almost 18% of facilities were cited for serious deficiencies that harm or place residents at risk of severe injury or death.(2) The prevalence of these deficiencies varied considerably across facilities and states, with more than 10% of states reporting 30+% of facilities with serious violations.(3)

Although facility-level deficiencies are not perfect measures of quality, higher deficiency levels have been shown to be associated with lower quality. For example, facilities receiving deficiency citations for administration were shown to have significantly lower quality of care with regard to pressure ulcers, contractures, and psychoactive drug use.(4) Facilities with higher prevalence of urinary incontinence and pressure sores were shown to have significantly more deficiencies in quality of life, quality of care, and other categories.(5) Risk-adjusted measures of NH quality based on decline in functional status, pressure ulcers, and prevalence of physical restraints were all found to significantly correlate with facility-level deficiency citations.(6)

Recently, “culture change” advocates emphasized the importance of the work environment as a key factor in improving organizational performance, including residents’ outcomes.(7;8) Several approaches to culture change in NHs have been implemented. However, evaluations of these initiatives, while reporting improvements in the quality of life and in interactions between residents and staff, did not quantitatively demonstrate improvements in quality of care.(9-11)

Aside from these intriguing but rare programs, little is known about the relationship between work environment attributes and NH quality. In this study we examined the relationships between several measures of work environment and a measure of quality - deficiency citations - controlling for facility characteristics, in a representative sample of NHs in New York State.

PRIOR RESEARCH AND PROPOSED HYPOTHESES

Quality of care and quality of the work environment have been largely treated as separate problems in NHs empirical research. Emerging theories and research focusing on complex adaptive systems have suggested that day-to-day operations, managerial practices, and work organization may influence facility performance.(8;12) Few, however, have examined the impact of work environment attributes on outcomes of NH residents. Anderson showed that greater participation of RNs in decision-making, better communication between RNs and Directors of Nursing (DONs), and higher perception of good DON leadership among the RNs were associated with better resident outcomes.(13;14) Barry showed that incidence of pressure ulcers among NH residents decreased as indicators of CNAs empowerment increased.(7) Most recently, Gittell examined the association between relational coordination (communication, shared goals, knowledge, and respect) among NH aides and resident quality of life.(15)

Overall, research on NH work environment and organization identified three broad categories that may influence quality – work effectiveness, group processes or teams, and job design.

Work effectiveness

The importance of leadership, communication, coordination, and conflict management, which are critical in the relationships between co-workers, were demonstrated in the NH literature.(16-18) These components of provider-to-provider relationships were shown to predict perceived work effectiveness in hospitals,(19) community based long-term care,(20) and in NHs.(21) The utility of using perceived work effectiveness as a predictor of care quality was demonstrated in hospitals(22) and in community-based LTC settings,(23-24) but not in NHs. We hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1: NHs with higher perceived work effectiveness have fewer deficiency citations, ceteris paribus.

Teams

Interdisciplinary health care teams have long been thought to promote better coordination of services resulting in better outcomes.(25-26) But, there has been relatively little focus on teams in NHs, although some studies did attribute better patient outcomes to teamwork and to the use of group processes.(23-25) While most NHs have in place a variety of teams such as care planning, quality improvement or special care, the extent to which workers involved in the day-to-day provision of care to residents are organized in teams has not been known. A recent study from NYS found that in an average facility 16% of the direct care staff report working in interdisciplinary daily practice teams.(26) We hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2: NHs with higher prevalence of daily care teams have fewer deficiency citations, ceteris paribus.

Job design

In NHs, job design was demonstrated to impact employee satisfaction and turnover.(8;27;28) Particularly salient in this regard is the practice of primary assignment, with staff assigned to work consistently with the same residents over time. This practice was shown to result in higher staff satisfaction and was postulated, but not demonstrated, to impact quality of care.(29-31) We hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3: NHs with higher proportion of staff with primary assignment have fewer deficiency citations, ceteris paribus.

DATA & METHODS

Sample

Primary data came from a “parent” study designed to examine the impact of work performance on risk-adjusted resident outcomes in New York State.(26) In total, 7,418 surveys from direct care staff of 162 nursing facilities were received (response rates from 3% to 91%) between July 2006 and April 2007. We used these data to obtain information on facility-level prevalence of teams, primary assignment, and perceived work effectiveness (survey available on request).

Information on deficiency citations were obtained from inspection surveys contained in the Online Survey, Certification and Reporting (OSCAR) files for 2006-2007. If a NH had more than one inspection survey between July 2006 and April 2007, the survey closest to the middle of the period was selected for analysis. Data on facility characteristics came from OSCAR and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) NH Compare. For each facility, primary and secondary data were linked. See Table 1 for listing of variables, definitions and data sources.

Table 1.

Variables, Definitions, and Data Sources

| Variable | Definitions | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables: | ||

| Quality of life deficiencies | Presence/absence (N=19 tags); dummy variable | OSCAR |

| Quality of care deficiencies | Total citations issued (N=26 tags); continuous variable | OSCAR |

| G-L deficiencies | Presence/absence of severe citations; dummy variable | OSCAR |

| Independent variables: | ||

| Work effectiveness | Mean score of 7 Likert scale items; continuous variable | NH Survey |

| Self-managed teams | Pct. staff reporting to work in self-managed teams | NH Survey |

| Formal teams | Pct. staff reporting to work in formal teams | NH Survey |

| Primary assignment | Pct. staff reporting to have primary assignment | NH Survey |

| Size | Number of residents in certified beds; continuous variable | OSCAR |

| Staffing ratios | RN hours per resident per day; continuous variable | CMS NHC |

| LPN hours per resident per day; continuous variable | CMS NHC | |

| CNA hours per resident per day; continuous variable | CMS NHC | |

| ADL index | Average pct. of residents who are bedfast or need assistance with eating, toileting, and transferring |

OSCAR |

| Facility ownership | Not-for-profit; categorical variable | OSCAR |

| Chain membership; categorical variable | OSCAR | |

| Survey inspection region | Nursing homes in NYS are divided into 7 inspection regions |

NYS DOH |

OSCAR = On-Line Certification and Reporting System

CMS NHC = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Nursing Home Compare

NH Survey = authors' primary data from NYS

NYS DOH = website of the NYS Department of Health

Dependent Variables

Federal regulations contain 190+ specific standards (tags) in 15 major categories of health-related deficiencies. We selected two categories specific to residents’ quality of care and life. The quality of life (QL) is comprised of 19 tags, while the quality of care (QC) includes 26. For each tag, if an auditor deems a facility not to have met the required standard, a deficiency citation is issued. Depending on the prevalence (scope) of the practice for which the deficiency is issued, and its impact on residents’ health and safety (severity), deficiencies are categorized based on seriousness from least (A) to most (L). Deficiencies categorized as G through L are considered most severe as they cause actual harm or immediate jeopardy to residents.

We constructed three facility-level quality measures. We defined QC deficiencies as a count of citations. QL and G-L deficiencies are relatively rare, thus we dichotomized them as present/absent. In our sample, all of the G-L deficiencies were in the QC category.

Key independent variables

Team prevalence

Two measures of team prevalence - percent of staff organized in formal and self-managed teams - were used. Both were constructed from responses provided by staff delivering daily personal care to residents. Individuals may work in teams or not. Respondents who reported working in a team were asked to characterize their team as either formally organized by management, with explicit protocols and procedures, or self-organized and managed by workers. The organization of NHs into multiple units and shifts allows for the simultaneous coexistence of staff in all three modalities – no teams, self-managed teams or formal teams. Teams were reported as being largely multidisciplinary and included a variety of personnel. There were no substantial differences in staff composition between formal and self-managed teams.(33)

Primary assignment

This measure, also derived from the staff survey, was defined as the percent of workers who report being consistently assigned to the same residents.

Perceived work effectiveness

The staff survey included a validated instrument for measuring work effectiveness. Work effectiveness was measured using a 7-item Likert-scale with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).(21) For each NH, the measure of work effectiveness was constructed as the average of all the responses provided by workers in that facility, with higher scores corresponding to better work-effectiveness. The reliability, face, content, and construct validity of this measure, in NH setting, was tested and reported elsewhere.(21) The measure had good psychometric properties (Cronbach's alpha = 0.87) and good discrimination with significantly (p<0.0001) less variability within than across facilities. The measure also met criterion-related validity because, as hypothesized, such processes as communication and coordination, conflict management, and staff cohesion were all shown to be statistically significant predictors of work-effectiveness.

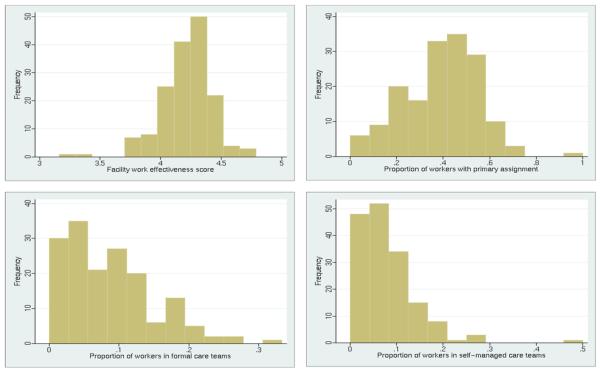

The facility-level distributions for each of the key independent variables are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the work environment variables: New York State sample facilities

Additional Site-level variables

We included several facility-level variables, which based on literature review may influence outcome measures. These variables include: facility ownership; staffing; size; resident case-mix. Furthermore, in order to avoid potential bias associated with variations in practices of local state survey offices we controlled for the random effects of the seven inspection regions in the state.

Statistical Analyses

We estimated three multivariate regression models. For QC deficiencies, we fit a multivariate linear regression with random intercepts for inspection regions and robust standard errors. For QL and G-L deficiencies we fit multivariate logistic regressions with random intercepts for inspection regions. Because the survey data include disproportionately fewer for-profit NHs, compared to the general population of NYS facilities, we included sample weights to obtain appropriately weighted estimations.

In linear and logistic models, we obtained standardized coefficients for each continuous variable by multiplying each original coefficient estimate by its standard deviation (SD). We reported the exponential of the standardized coefficients for the logistic models. The coefficients for dichotomous variables were not standardized.

We examined correlation coefficients among the work environment variables and found no significant correlations. Diagnostic tests using variance inflation factors were also performed, but detected no evidence of significant effects that may inflate standard errors. The Breusch-Pagan and White tests found no evidence of heteroscedasticity, and Ramsey RESET tests show no evidence of model specification error.

RESULTS

Because the survey was open to all eligible NYS facilities and not a randomly selected sample,(30) the possibility of a response bias should be considered. We compared facilities in the sample to eligible NYS homes on all variables obtained from secondary data sources (Table 2). We found no statistically significant differences between the two groups with regard to the outcome variables. The sample facilities were significantly different on three independent variables – size, LPN hours/resident/day, and percent of non-profit facilities. Although statistically significant, the differences between the sample facilities and all homes for the first two variables are small and not likely to be operationally meaningful. To correct for the sampling bias due to the over-representation of non-profit homes, we employed sampling probability weights in the multivariate models.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Sample Facilities and Comparison to All Eligible NYS Nursing Homes

| Sample Facilities (N=162) |

All Eligible NYS Facilities (N=600) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | P-value a | ||

| Mean (SD) [%] |

Mean (SD) [%] |

||

| Dependent variables : | |||

| Quality of care deficiencies (QC) | 1.69 (1.57) | 1.57 (1.68) | 0.352 |

| Quality of life deficiencies (QL) - % facilities with any deficiencies | 0.48 (0.75) [33.95] |

0.50 (0.75) [39.00] |

0.696 0.239 |

| Severe deficiencies (G-L) - % facilities with any deficiencies | 0.33 (0.91) [19.75] |

0.25 (0.67) [18.50] |

0.247 0.717 |

| Independent variables: | |||

| Work effectiveness | 4.22 (0.22) | ||

| Self-managed teams | 7.64% (6.47) | ||

| Formal teams | 8.45% (6.46) | ||

| Primary assignment | 39.43% (16.41) | ||

| Size | 202.83 (136.65) | 180.52 (118.86) | 0.039 |

| Staffing ratios | |||

| RN hours/resident/day | 0.61 (0.23) | 0.58 (0.26) | 0.167 |

| LPN hours/resident/day | 0.83 (0.25) | 0.79 (0.28) | 0.026 |

| CNA hours/resident/day | 2.31 (0.40) | 2.27 (0.43) | 0.196 |

| ADL index | 18.44% (6.93) | 19.23 (7.73) | 0.151 |

| Facility ownership | |||

| Not-for-profit | 66.05% | 48.17% | <0.001 |

| Chain membership | 11.11% | 13.17% | 0.486 |

P-value for means between sample facilities and all NYS facilities

An average facility had 1.69 QC, 0.48 QL, and 0.33 G-L deficiencies. QL and G-L deficiencies were relatively rare, with only 33.95% and 19.75% of facilities having any such deficiencies, respectively (Table 2). On average, NHs reported 8.45% of direct care staff working in formal teams and 7.46% in self-managed teams, with substantial variation across facilities. Almost 40% of staff reported having primary assignment, with substantial across facilities variation (SD=16.41%). The measure of perceived work-effectiveness had an average value of 4.22, suggesting that most workers viewed their facilities as performing well (higher number indicating better performance). There was, however, some variation in this measure, with a standard deviation of 0.22 - i.e. 68% of NHs scored between 4.00 and 4.44.

Results of the multivariate regression models predicting all three deficiency citation measures are shown in Table 3. We found work-effectiveness to be a statistically significant predictor of our deficiency measures in all three models, supporting hypothesis 1. NHs with higher work-effectiveness had significantly fewer QC (p=0.008), QL (p=0.064), and G-L (p=0.014) deficiencies. Controlling for all other factors, one SD (0.216) increase in work-effectiveness score is associated with a 0.379 reduction in QC citations (22.4% reduction in the average per facility number of QC deficiencies). A one SD increase in work-effectiveness also means that the odds for a NH to have any QL deficiencies was 30% (1-0.696) less and to have any G-L citations was 52% (1-0.485) less; translating to a 22% reduction in QL risk (from 33.95% to 26.48%), and a 46% reduction in G-L risk (from 19.75% to 10.66%), respectively.

Table 3.

Characteristics Predicting Quality of Life and Quality of Care Deficiencies in NYS Nursing Homes: Multivariate Models with Robust Standard Errors and Probability Weightsa

| All Models | Quality of Care (QC) Deficiencies |

Quality of Life (QL) Deficiencies |

G-L Quality of Care Deficienciesc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Linear Regression] | [Logistic Regression] | [Logistic Regression] | |||||

| Independent Variables |

Standard Deviation |

Standardized Parameter Estimatesb |

P value | Standardized Odds Ratiosb |

P value | Standardized Odds Ratiosb |

P value |

| Work effectiveness | 0.216 | −0.379 | 0.008 | 0.696 | 0.064 | 0.485 | 0.014 |

| Self-managed teams | 0.065 | −0.178 | 0.008 | 0.881 | 0.618 | 0.702 | 0.297 |

| Formal teams | 0.065 | −0.028 | 0.848 | 0.850 | 0.527 | 0.778 | 0.153 |

| Primary assignment | 0.164 | −0.163 | 0.031 | 1.210 | 0.200 | 0.607 | 0.037 |

| Size | 136.645 | 0.146 | 0.228 | 1.619 | 0.162 | 1.194 | 0.519 |

| RN staffing ratio | 0.233 | −0.253 | 0.005 | 0.582 | 0.110 | 0.792 | 0.395 |

| LPN staffing ratio | 0.252 | −0.106 | 0.239 | 1.324 | 0.412 | 0.837 | 0.507 |

| CNA staffing ratio | 0.399 | 0.017 | 0.746 | 0.995 | 0.984 | 1.353 | 0.191 |

| ADL index | 0.069 | 0.236 | 0.027 | 1.088 | 0.554 | 0.974 | 0.896 |

| Chain facility | 0.315 | −0.181 | 0.333 | 0.430 | 0.233 | 2.481 | 0.154 |

| For profit facility | 0.475 | 0.057 | 0.982 | 1.199 | 0.509 | 0.716 | 0.599 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.093 | 0.119 | 0.111 | ||||

| C statistic | 0.71 | 0.72 | |||||

Probability weights correct for sampling response bias. We fit each model both with (as depicted in this table) and without sampling weights. In the model without sampling weights primary assignment is not a statistically significant predictor of QC deficiencies; all other results are fairly consistent across all models.

Parameter coefficients were standardized as described in the text

In the analytical sample all of the health related deficiencies with G-L severity were in the quality of care category

We found partial support for the association between team penetration and deficiencies (hypothesis 2), but only with respect to QC deficiencies. Facilities with higher prevalence of self-managed (but not formal) teams have significantly fewer deficiencies (p=0.008). One SD (0.065) increase in the proportion of workers in self-managed teams lowered QC deficiencies by 0.178 (10.5% reduction), all else being equal.

For the association between primary assignment and deficiency citations (hypothesis 3), we found statistically significant support with regard to QC (p=0.031) and G-L (p=0.037) measures, but not QL. One SD (0.164) increase in primary assignment prevalence resulted in 0.163 (9.6%) reduction in QC and almost 40% lower odds of G-L deficiencies.

In addition, one SD (0.233) increase in RN staffing is associated with 0.253 fewer QC deficiencies, a 15% reduction. All else being equal, facilities with higher ADL index had significantly (p=0.027) more (0.236) QC deficiencies.

DISCUSSION

Referred to as “low tech and high touch,” NH environments are characterized by high levels of task interdependence between disciplines, considerable variability and uncertainty with regard to residents’ health outcomes, and are constrained by the availability of resources necessary to provide care.(15) In such settings, the organization of work and the relationships among workers could be particularly important contributors to the quality of care.(8) This study provides empirical evidence to support this assumption and makes several contributions to the literature furthering our understanding of the relationship between NH work environment and quality-related deficiency citations.

While previous studies have suggested that teamwork and group processes may be associated with better resident outcomes,(23;25;32) this is the first study to document an association between higher prevalence of self-managed daily practice teams in NHs and fewer quality of care deficiency citations. However, the potential benefit derived from having teams does not appear to be very great. A one SD increase in team prevalence is associated with only a 0.178 reduction in the number of QC deficiencies. Furthermore, such teams have no significant effect either on QL deficiencies or on the severe, G-L, citations. However, this might be due to lack of power, given the very small number of QL and G-L deficiencies in any one facility. It is also possible that the limited impact of self-managed teams is due to their limited prevalence. In our sample, the majority of facilities have fewer than 20% of their direct care staff organized in such teams. Prevalence of self-managed teams may be too marginal to make a substantial impact.

We were surprised to find no significant association between formally organized teams and deficiency citations. One could expect that formally organized teams, receiving support and resources from management, would be better able to function and be more effective in impacting quality. Although formally organized teams report the same multidisciplinary structure as the self-managed teams,(33) it is possible their structure is more mechanistic, i.e. organized by management with specified roles and tasks, resulting in more controlled or hierarchical decision-making and problem-solving, which may undermine the flow of information. In such teams formal sharing of information may be restricted to higher status nurses and other core professionals, and not extend to nursing assistants.(34) In contrast, more organically structured self-managed teams may be less hierarchical and more spontaneous in communicating, improvising and problem-solving, thus also being more effective in situation of high uncertainty and resource/time constraints, and better able to provide high quality care.

Our prior work offers an alternative explanation as well. It is possible that in facilities in which the management has undertaken the initiative to organize teams, its objective, and hence the focus of the team, is not quality improvement, but rather cost savings. In a recent study, Mukamel, et al.(33) found that presence of formal teams was associated with significant cost savings, while presence of self-managed teams was not. If management invests in teams to achieve cost savings, it is not surprising that we did not find a significant association between formal teams and fewer deficiency citations. It is in fact comforting that we did not find a positive association, suggesting that an emphasis on cost savings is not at the expense of quality, at least to the degree that deficiencies can capture such deterioration in quality.

Consistent assignment of nursing staff, particularly the CNAs, is viewed as a best-care practice and a cornerstone of culture change in NHs. However, empirical evidence with regard to the association between this practice and quality of care has not been clear. Our findings provide support for the association between primary assignment and QC deficiencies, including G-L severity, but not for QL deficiencies. This is consistent with other studies also showing mixed results for the association of primary assignment and quality of care.(35) In our study, one SD increase in the prevalence of primary assignment confers close to a 10% reduction in QC deficiencies. Facilities with higher prevalence of primary assignment are 40% less likely, than facilities with lower prevalence, to experience high severity G-L citations.

But the biggest attribute, and the only one showing a significant association between work environment and all three quality measures, is work-effectiveness. In an average facility, one SD increase in the work-effectiveness score is associated with 22% fewer QC deficiencies, and with 30% and 51% lower odds of having any QL and G-L deficiencies, respectively. Thus a relatively modest increase in a facility's work-effectiveness score may be associated with rather substantial improvements in care quality.

For NH managers our findings suggest that quality improvement efforts should focus on certain work environment attributes, particularly those that affect work-effectiveness. Prior literature identified several factors as being important predictors of perceived work-effectiveness in healthcare organizations(19;20); among them, leadership, communication and coordination of care, and conflict resolution.(15) . While managers may wish to foster all of these dimensions to improve relationships among co-workers, not all dimensions appear to be equally important for overall work-effectiveness. Our own prior work in NHs showed that good communication/coordination and conflict management among frontline workers contribute most to perceived work-effectiveness.(21) Using a 5-point Likert-scale, we found that a 1 point increase in communication/coordination or in conflict management leads to a 0.25-point increase in the work-effectiveness score. The importance of workplace conditions (flexibility of schedules, pay, benefits, promotion) and staffing, while also statistically significant, had substantially smaller effects on the work-effectiveness score (0.05 and 0.12, respectively). The effect of leadership, although statistically significant, appeared to be the smallest and almost negligible at 0.02. This small effect size may reflect the largely neglected importance of the role of front-line leadership in NHs.(8)

These findings about the importance of work relationships in influencing performance are echoed in other studies, even those that do not directly focus on quality of care. A recent survey conducted in conjunction with the National Study of the Better Jobs Better Care demonstration asked direct care workers in several LTC settings “what is the single most important thing your employer could do to improve your job?”(36) Better work relationships - improved communication, better supervision, and more teamwork - ranked higher than increased compensation.

Several limitations should be noted. 1) This study is based on NHs from one - albeit the largest - state in the nation, so that generalizations to facilities outside of NYS should be done with caution. 2) NH regulations might be very different in NY compared to other states. At the same time, the proportion of facilities in NY cited with deficiencies for harm or immediate jeopardy is very close to the national average, 17.2% in NYS compared to 17.8% nationally.(2) 3) Deficiency citations are known to reflect not only quality of care, but also policies and practices of the surveyors carrying out the surveys. While much of the variation is across states, it has also been observed within states, across local offices.(6) To account for it, we used regression models with clustering by survey regions, but we recognize that number of deficiencies can be interpreted as a measure of quality only with caution. 4) Survey participation was voluntary, so a possibility of a response bias must be considered. We did not detect any significant differences (Table 2) between all eligible facilities and those participating in the survey. Furthermore, there were no significant correlations between within facility response rates and any of the dependent or independent variables, except for a correlation between higher response rates in facilities with higher numbers of quality of care deficiencies (correlation of 0.25, p=0.001), suggesting that the response bias, if it exists, is minimal.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that creating work environments which lead frontline workers to higher work-effectiveness also results in fewer deficiency citations. Similarly, but to a lesser degree, management practices that encourage the formation of self-managed teams and promote consistent assignment may also lead to fewer deficiency citations. Prior work offers insights as to the processes and mechanisms that can be used to foster higher work-effectiveness.(21) This body of work suggests NH management practices and directions that can lead to better care for residents.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institute on Aging, Grant R01 AG23077. We also express our gratitude to the participating nursing homes and their staff, the New York Association of Homes and Services for the Aging (NYAHSA) and the New York State Health Facilities Association (NYSHFA).

Appendix 1. Perceived Work Effectiveness: Definition and Survey Assessment Items

Perceived Work Effectiveness: the perceived effectiveness of co-workers with respect to technical quality of residents' care, and the ability to meet residents and their families care needs.

| Assessment items | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| N=7415 responses | ||

| ■ We do a good job of meeting the needs of our residents' families |

4.24 | 0.88 |

| ■ My co-workers contribute their experience and expertise to produce good quality of care for residents |

4.12 | 0.92 |

| ■ We do a good job meeting residents' care needs |

4.29 | 0.86 |

| ■ We respond well to emergencies | 4.38 | 0.83 |

| ■ We almost always meet our residents' treatment goals |

4.06 | 0.94 |

| ■ Although we care for people with a variety of needs, our residents experience good outcomes |

4.27 | 0.79 |

| ■ Overall, my co-workers and I function very well together |

4.18 | 0.90 |

Contributor Information

Helena Temkin-Greener, Department of Community and Preventive Medicine & Center for Ethics, Humanities and Palliative Care University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Box 644, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Rochester, NY 14642.

Nan(Tracy) Zheng, Department of Community and Preventive Medicine University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Box 644, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Rochester, NY 14642 Nan_Zheng@urmc.rochester.edu (585-273-2425).

Shubing Cai, Department of Community and Preventive Medicine University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Box 644, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Rochester, NY 14642 Shubing_Cai@urmc.rochester.edu (585-275-0369).

Hongwei Zhao, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics Texas A&M School of Rural Public Health College Station, Texas 77843-1266 zhao@srph.tamhsc.edu (979-458-2917).

Dana B. Mukamel, Department of Medicine, Health Policy Research Institute, University of California, Irvine 100 Theory, Suite 110 Irvine CA 92697-5800 dmukamel@uci.edu (949 824-8873)

Reference List

- 1.Harrington C, Carillo H, Blank B. Nursing, Facilities, Staffing, Residents, and Facility Deficiencies, 2001 Through 2007. Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of California; San Francisco: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.General Accounting Office . Federal Monitoring Surveys demonstrate Continued Understatement of Serious Care Problems and CMS Oversight Weaknesses. United States Government Accountability Office; Washington, DC: 2008. Nursing Homes. (Report No.: GAO-08-517). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiner J, Freiman M, Brown D. Twenty Years After The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park, CA: 2007. Nursing Home Quality. (Report No.: 7717). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castle N, Longest B. Administrative deficiency citations and quality of care in nursing homes. Health Services Management Research. 2006;19(3):144–52. doi: 10.1258/095148406777888107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrington C, Zimmerman D, Karon SL, Robinson J, Beutel P. Nursing home staffing and its relationship to deficiencies. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000 September;55(5):S278–S287. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.5.s278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukamel D. Risk Adjusted Outcome Measures and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. Medical Care. 1997;35:367–85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199704000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barry T, Brannon D, Mor V. Nurse aide empowerment strategies and staff stability: effects on nursing home resident outcomes. Gerontologist. 2005;45:309–17. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton S. Beyond unloving care:Linking human resource management and patient care quality in nursing homes. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2000;11:591–616. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone R, Reinhard S, Bowers B, et al. Evaluation of the Wellspring Model for Improving Nursing Home Quality. The Commonwealth Fund; New York City: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman M, Looney S, O'Brien J, Ziegler C, Pastorino C, Turner C. The Eden Alternative: Findings after one year of implementation. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 2002;57A:M422–M427. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.7.m422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kane R, Arling G, Mueller C, Held R, Cooke V. A quality-based payment strategy for nursing home care in Minnesota. Gerontologist. 2007;47:108–15. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wunderlich G, Kohler P, Gooloo S. Improving the quality of long-term care. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson R, McDaniel R. RN participation in Organizational decision Making and Improvement in Resident Outcomes. Health Care Management Review. 1999;24(1):7–16. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson R, Issel L, McDaniel R., Jr Nursing homes as complex adaptive systems: relationship between management practice and resident outcomes. Nursing Research. 2003;52(1):12–21. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gittell J, Weinberg D, Pfefferle S, Bishop C. Impact of relational coordination on job satisfaction and quality outcomes: a study of nursing homes. Human Resource Management Journal. 2008;18(2):154–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes-Thompson S, Gajewski B, Scott-Cawiezell J, Dunton N. An Exploration of Nursing Home Organizational Processes. West J Nurs Res. 2006;28(8):935–54. doi: 10.1177/0193945906287053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott-Cawiezell J, Schenkman M, Moore L, Vojir C, Connolly R, et al. Exploring Nursing Home Staff's Perceptions of Communication and Leadership to Facilitate Quality Improvement. J Nurs Care Quality. 2004;19(3):242–52. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott J, Vojir C, Jones K, Moore L. Assessing Nursing Homes' Capacity to Create and Sustain Improvement. J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20(1):36–42. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shortell SM, Rousseau DM, Gillies RR, Devers K, Simons TL. Organizational Assessment in Intensive Care Units (ICUs): Construct Development, Reliability, and Validity of the ICU Nurse-Physician Questionnaire. Medical Care. 1991;29(8):709–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temkin-Greener H, Mukamel D, Gross D, Kunitz S. Measuring Interdisciplinary Team Performance in a Long-Term Care Setting. Medical Care. 2004;42(5):472–81. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124306.28397.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Temkin-Greener H, Cai S, Katz P, Zhao H, Mukamel D. Measuring Work Performance in Nursing Homes. Medical Care. 2009;47(4):482–491. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e318190cfd3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shortell SM, Zimmerman JE, Rousseau DM, Gillies RR, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Knaus WA, Duffy J. The performance of intensive care units: does good management make a difference? Med Care. 1994 May;32(5):508–25. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rantz M, Hicks L, Grando V, Petroski G, Madsen R, et al. Nursing Home Quality, Cost, Staffing, and Staff Mix. Gerontologist. 2004;44(1):24–38. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeatts D, Cready C, Ray B, DeWitt A, Queen C. Self-Managed Work Teams in Nursing Homes: Implementing and Empowering Nurse Aide Teams. Gerontologist. 2004;44(2):256–61. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berlowitz D, Young G, Hickey E, et al. Quality improvement implementation in the nursing home. Health Services Research. 2003;38:65–83. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Temkin-Greener H, Cai S, Katz P, Mukamel D. Daily Practice Teams in Nursing Homes: Evidence From New York State. Gerontologist. 2009;49(1):68–80. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotton J, Tuttle J. Employee turnover: A meta-analysis and review with implications for research. Academy of Management Review. 1986;11:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banaszak-Holl J, Hines M. Factors associated with nursing home staff turnover. Gerontologist. 1996;36:512–7. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.4.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smyer M, Brannon D, Cohn M. Improving Nursing Home Care Through Training and Job Redesign. Gerontologist. 1992;32(3):327–33. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner A, Ronch J. Culture change in long-term care. Haworth Press, Inc.; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgio L, Fisher S, Fairchild J, Scilley K, Hardin J. Quality of Care in the Nursing Home: Effects of Staff Assignment and Work Shift. Gerontologist. 2004;44(3):368–77. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeatts D, Cready C. Consequences of Empowered CNA Teams in Nursing Home Settings: A Longitudinal Assessment. Gerontologist. 2007;47(3):323–39. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukamel DB, Cai S, Temkin-Greener H. Cost implications of organizing nursing home workforce in teams. HSR:Health Services Research. 2009;44(4):1309–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cott C. “We decide, you carry it out”: A social network analysis of multidisciplinary long-term care teams. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(9):1411–21. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahman A, Straker J, Manning L. Staff Assignment Practices in Nursing Homes: Review of the Literature. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2009;10:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kemper P, Heier B, Barry T, Brannon D, Angelelli J, Vasey J, Anderson-Knott M. What Do Direct Care Workers Say Would Improve Their Jobs? Differences Across Settings. Gerontologist. 2008;48(Special Issue 1):17–25. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.supplement_1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]