Abstract

Background

The maternal zygotic transition marks the time at which transcription from the zygotic genome is initiated and a subset of maternal RNAs are progressively degraded in the developing embryo. A number of early zygotic genes have been identified in Drosophila melanogaster and comparisons to sequenced mosquito genomes suggest that some of these early zygotic genes such as bottleneck are fast-evolving or subject to turnover in dipteran insects. One objective of this study is to identify early zygotic genes from the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti to study their evolution. We are also interested in obtaining early zygotic promoters that will direct transgene expression in the early embryo as part of a Medea gene drive system.

Results

Two novel early zygotic kinesin light chain genes we call AaKLC2.1 and AaKLC2.2 were identified by transcriptome sequencing of Aedes aegypti embryos at various time points. These two genes have 98% nucleotide and amino acid identity in their coding regions and show transcription confined to the early zygotic stage according to gene-specific RT-PCR analysis. These AaKLC2 genes have a paralogous gene (AaKLC1) in Ae. aegypti. Phylogenetic inference shows that an ortholog to the AaKLC2 genes is only found in the sequenced genome of Culex quinquefasciatus. In contrast, AaKLC1 gene orthologs are found in all three sequenced mosquito species including Anopheles gambiae. There is only one KLC gene in D. melanogaster and other sequenced holometabolous insects that appears to be similar to AaKLC1. Unlike AaKLC2, AaKLC1 is expressed in all life stages and tissues tested, which is consistent with the expression pattern of the An. gambiae and D. melanogaster KLC genes. Phylogenetic inference also suggests that AaKLC2 genes and their likely C. quinquefasciatus ortholog are fast-evolving genes relative to the highly conserved AaKLC1-like paralogs. Embryonic injection of a luciferase reporter under the control of a 1 kb fragment upstream of the AaKLC2.1 start codon shows promoter activity at least as early as 3 hours in the developing Ae. aegypti embryo. The AaKLC2.1 promoter activity reached ~1600 fold over the negative control at 5 hr after egg deposition.

Conclusions

Transcriptome profiling by use of high throughput sequencing technologies has proven to be a valuable method for the identification and discovery of early and transient zygotic genes. The evolutionary investigation of the KLC gene family reveals that duplication is a source for the evolution of new genes that play a role in the dynamic process of early embryonic development. AaKLC2.1 may provide a promoter for early zygotic-specific transgene expression, which is a key component of the Medea gene drive system.

Background

The early embryo is transcriptionally inactive and all RNAs present that are needed for embryonic development have been maternally deposited during oogenesis. The onset of zygotic transcription marks the beginning of the maternal-zygotic transition (MZT) whereby maternal RNAs are progressively degraded and zygotic transcription takes over, providing the necessary gene products for development [1-4]. Recent large-scale studies have tried to determine what genes or groups of genes are expressed during Drosophila development [1,2]. At least some of the early zygotic genes such as bottleneck [5] are fast-evolving or subject to turnover in dipteran insects because a homolog of the Drosophila bottleneck is not found in any of the sequenced mosquito genomes. To study the evolution of early zygotic genes through comparative analysis, we set out to identify early zygotic genes in the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti by transcriptome profiling, taking advantage of large-scale Illumina sequencing. We have determined the MZT starting in Ae. aegypti within 2-3 hr after egg deposition, based on Illumina transcriptome profiling and RT-PCR. This time is just before or at the beginning of pole cell formation at 3 hr [6]. Early zygotic transcription at this time is developmentally consistent with reports from Drosophila that indicate transcription starting as early as cycle 8 [7], also just before the onset of pole cell formation. We focused on the purely zygotic genes that do not have a maternal contribution. Thus, we were searching for transcripts that were not present in the embryos 0-2 hr after egg deposition but started to appear 2-4 hr after egg deposition.

One of the early and pure zygotic genes identified was a kinesin light chain (KLC) gene that is the focus of this study. The three classes of cytoskeleton molecular motors include kinesin, dynein, and myosin, with kinesin and dynein using microtubules as a track for transport and myosin depending on actin filaments [8]. Kinesins are a diverse family of proteins as demonstrated by phylogenies based on the heavy chain [9,10] and are involved in a variety of cellular transport roles [11]. The conventional kinesin (kinesin-I) is a heterotetramer having two kinesin heavy chains characterized by ATPase-dependent motor activity and two kinesin light chains (KLCs). KLCs are accessory proteins that have a C-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain comprising approximately 34 residues that binds cargo for transport [11]. Here we report the discovery of two novel embryonic-specific KLC genes we call AaKLC2 in Aedes aegypti (Ae. aegypti) and their likely ortholog in C. quinquefasciatus. We analyze these genes in comparison to other KLC genes in diverse organisms and suggest gene duplication as a source for the purely zygotic AaKLC2 genes, which are fast-evolving.

Another goal of this research was related to efforts to develop a gene drive system for mosquitoes, which may be used to spread pathogen-resistant genes into mosquito populations to control mosquito-borne infectious disease. A natural gene drive system comprised of maternal effect dominant embryonic arrest (Medea) factors was first discovered in the flour beetle T. castaneum [12]. In this system, Medea is comprised of a maternally expressed toxin that is passed on to all embryos of a Medea-bearing female, and a tightly linked zygotically expressed antidote that is only made in Medea-bearing embryos. As a result, only Medea-bearing offspring of a Medea-bearing female will survive, which leads to the fixation of the Medea allele in the population. Chen et al. 2007 successfully engineered and demonstrated a Medea system in D. melanogaster that employs the use of maternal-specific and zygotic-specific promoters to drive expression of toxin and antidote genes, respectively [13]. Developing a Medea system in mosquitoes requires the identification of early zygotic genes in the mosquito species of interest due to the difficulty of finding orthologs to D. melanogaster zygotic genes as mentioned above. We identified the zygotic-specific AaKLC2.1 and demonstrated strong promoter activity of its upstream sequence in Ae. aegypti early embryos.

Results

Identification of two early zygotic kinesin light chain genes AaKLC2.1 and AaKLC2.2

We looked at expression from Ae. aegypti Liverpool strain embryos at 4 time ranges of 0-2, 2-4, 4-8, and 8-12 hr. Over 16,000 Ae. aegypti annotated transcripts (vectorbase.org) were used in BLAST [14] vs. sequences obtained from Illumina. Of particular interest for the discovery of pure early zygotic genes were the transcripts having no hits in the 0-2 hr (presence indicates a maternal transcript), and hits present at 2-4 hr. Several transcripts were identified with these criteria, including two KLC genes AaKLC2.1 (AAEL011410-RA) and its paralog AaKLC2.2 (AAEL014967-RA). The nomenclature here does not correspond to mammalian KLC nomenclature because the focus is on insect KLC genes. AaKLC2.1 and AaKLC2.2 are 98% identical to each other in their coding regions and it was possible to design gene-specific primers to independently confirm their expression profiles by RT-PCR as described later. Shown in Table 1 is the Illumina result of three KLC genes in this study, one of which is not purely zygotic, but ubiquitously expressed (AAEL012472, see below).

Table 1.

Kinesin Light Chain Gene Transcription Profile By Illumina Sequencing

| Transcript ID/Query | CDS Length | 0-2 hr | 2-4 hr | 4-8 hr | 8-12 hr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAEL011410-RA | 1419 | 0 (0) | 250 (366) | 405 (728) | 0 (0) |

| AAEL014967-RA | 1419 | 0 (0) | 240 (352) | 436 (784) | 1 (4) |

| AAEL012472-RA | 1536 | 62 (193) | 1103 (1493) | 311 (516) | 140 (516) |

Notes: 0-2, 2-4, 4-8, and 8-12 hr indicate time ranges from which RNA was isolated from developing Ae. aegypti embryos. Raw values of the three transcripts in the four samples (number of hits from BLAST using an E-value cutoff of 1e-7) are given at left. Normalized values (in parentheses) are calculated as the raw values divided by the transcript (CDS) length, then divided by the total number of reads matching all annotated mRNA transcripts from each sample, and multiplied by 1e10. The total number of reads matching all annotated mRNA transcripts from each sample time point was: 0-2 hr (2087707); 2-4 hr (4810435); 4-8 hr (3920821); 8-12 hr (1767898). See Additional File 1 for a summary of the Illumina data. A FASTA file of all Illumina sequence hits that match the three kinesin light chain transcripts in all four samples is provided as Additional File 2.

Structural and genomic analysis of AaKLC2 and other KLC genes

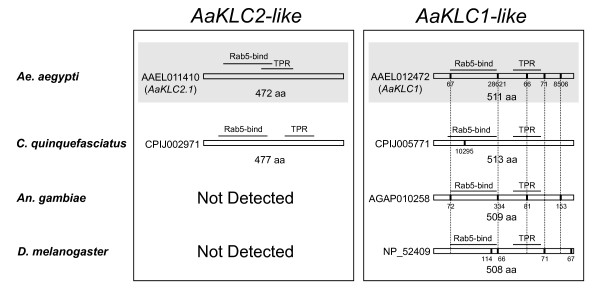

Structural analysis supports the categorization of two KLC gene groups, the AaKLC1-like and the AaKLC2-like genes (Figure 1). AaKLC2.1 is an intronless gene with a predicted open reading frame (ORF) of 1419 nucleotides (nt). AaKLC2.2 is also intronless and has 98% nt and aa identity to AaKLC2.1 in its coding region. The lack of introns in the AaKLC2-like genes is notable since it has been reported that 70% of Drosophila early zygotic genes do not have introns presumably for increased efficiency of transcription with fast-cycling nuclei [1]. A likely ortholog of the AaKLC2 genes was identified in C. quinquefasciatus, which is an intronless gene having a similar ORF length (gene ID: CPIJ002971). However, no similar genes were found in the genome sequences of An. gambiae [15], An. stephensi (8× coverage genome assembly, Tu unpublished), D. melanogaster, or other insects. Thus from genome analysis, it appears that AaKLC2-like genes are restricted to mosquitoes of the subfamily Culicinae. The expression of the C. quinquefasciatus gene will need to be verified by RT-PCR or other methods to determine if it is indeed an early and transient zygotic gene. This is why we have not called it CqKLC2.

Figure 1.

Coding sequence structure and domains of kinesin light chain genes of mosquitoes and D. melanogaster. On the left are the AaKLC2-like genes and on the right are the AaKLC1-like genes. Vertical bars show location of introns and intron size is given below bars. Note conservation of gene structure (vertical lines show conservation of intron position). Intron sizes are shown as number of bases and are given below vertical bars. Rab5-bind, Rabaptin 5-binding domain. TPR, tetratricopeptide repeat domain. Shaded parts indicate those genes that have been analyzed by RT-PCR and Illumina transcriptome profiling (only AaKLC2.1 is shown). Predicted introns are taken from Vectorbase.org and Ensembl.org.

Unlike the AaKLC2-like genes, AaKLC1-like genes have longer ORFs and at least one intron (Figure 1, right column). Interestingly, these AaKLC1-like genes have conservation of intron position in some cases. For example, 4 introns have conserved positions between Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae, and one intron position is conserved in Ae. aegypti, An. gambiae, and D. melanogaster. In addition, one intron position and length is conserved between Ae. aegypti and D. melanogaster.

All of the KLC genes have tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) and Rab5-binding domains as determined by the Conserved Domain Database (CDD) v2.17 at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (Figure 1). Rab5 is a small GTPase that regulates early endosome fusion [16,17]. The Rab-5 binding and TPR domains detected in the 472 aa sequence of AaKLC2.1 have E-values of 1e-26 and 3e-3, respectively. It is interesting to note that there is a partial gene duplication (gene ID: AAEL005502, see Figure 2) of AaKLC1 that contains only the Rab5 binding domain and has 100% nt identity to AaKLC1 throughout 729 of the 741 bases of the AAEL005502 ORF (differences are only found in the last 12 bases). The 246 aa conceptual translation of AAEL005502 only has 2 aa different than AaKLC1.

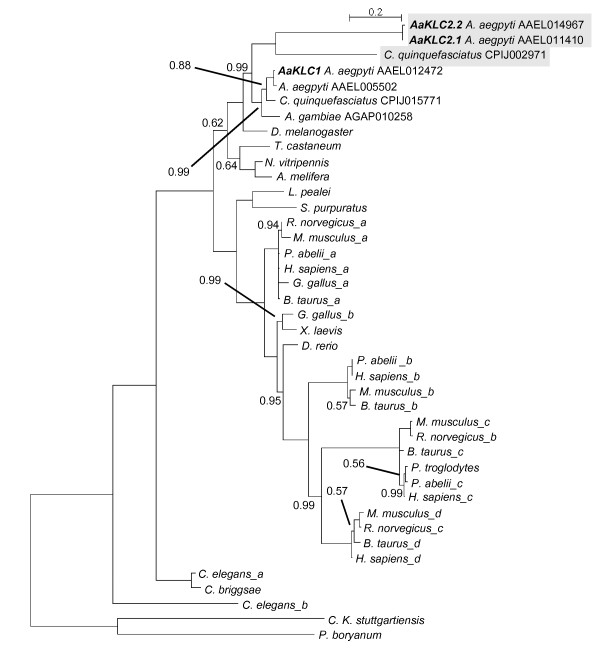

Figure 2.

Kinesin light chain phylogeny. Phylogenetic inference performed using MrBayes v3.1.2 with aa sequences conceptually translated from kinesin light chain genes of mosquitoes, other holometabolous insects, and divergent taxa. Clade credibility values are shown at each node only when they are not equal to 1.0. Accession numbers are given for mosquito sequences. Letters after species names indicate multiple KLC sequences for a species and are not associated with KLC nomenclature. See Additional File 3 for sequences and accession numbers, and Additional File 4 for alignment in FASTA format. Tree is rooted using kinesin light chain sequences from two bacterial species. Shaded sequences designate zygotic (AaKLC2.1 and AaKLC2.2) and potential zygotic (C. quinquefasciatus CPIJ00CP2971) genes. Bold letters highlight Ae. aegypti KLC genes. Scale shows number of aa changes per site. An. stephensi KLC1 is not included because we did not have the genome sequence at the time of phylogeny construction. AAEL005502 is not labeled AaKLC1.2 because this gene is a partial duplication of AaKLC1 and has only the Rab5-binding domain (see text).

Phylogenetic inference of KLC genes demonstrates a diverse evolutionary history

Published kinesin phylogenies have focused on the kinesin heavy chain. Here we present a KLC phylogeny including representatives from mosquito, fly, wasp, honeybee, worm, fish, frog, sea urchin, squid, monkey, cow, chicken, mouse, rat, human, and bacteria (Figure 2). Like kinesin heavy chain phylogeny, KLC phylogeny is also rather diverse having many paralogous groups, with most of the diversity existing in mammals. For example, humans have 4 paralogous KLC genes. In contrast, the holometabolous insects surveyed have 1 KLC gene in common that includes AaKLC1 in Ae. aegypti. The AaKLC2 genes that are zygotic-specific (see below) and their likely ortholog in C. quinquefasciatus appear to be restricted to species of Culicinae because similar sequences could not be detected in the genome sequences of the mosquito An. gambiae or other insects. Interestingly, the AaKLC2 genes and the C. quinquefasciatus AaKLC2-like gene are fast-evolving genes relative to the highly conserved AaKLC1-like genes. Shown are the only KLC genes detected in insects resulting from BLAST searches using divergent KLC genes from the phylogeny as queries.

The phylogeny indicates that the AaKLC2-like genes arose prior to the divergence of Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae lineages, suggesting an event that predates the divergence of Culicinae and Anophelinae. This is perplexing because AaKLC2-like genes are not detected in Anopheline mosquitoes An. gambiae and An. stephensi, which suggests that AaKLC2-like genes arose within Culicinae after Culicinae/Anophelinae divergence and prior to the divergence of Aedes and Culex genera. Also curious is that Ae. aegypti AAEL11410 and C. quinquefasciatus CPIJ002971 KLC aa sequences do not obtain each other as reciprocal best hits by blastp. However, the structural and phylogenetic inference supports their grouping (the clade credibility value is 0.99 for the node at the divergence of KLC1-like and KLC2-like clades). Genomic survey of more species will be needed to elucidate this matter.

Expression analysis indicates that AaKLC2 genes are transiently expressed in the early zygotic stage while AaKLC1 is ubiquitously expressed

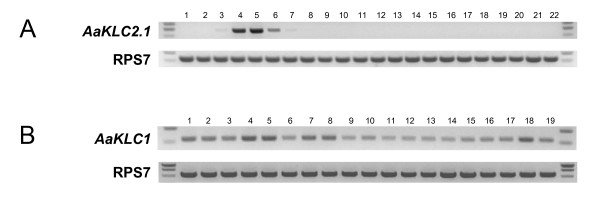

The first indication of AaKLC2.1 and AaKLC2.2 as early and transiently expressed zygotic genes came from embryonic transcriptome profiling (see above, Table 1). Transcripts were absent in the 0-2 hr sample and had no hits in the 8-12 hr sample (AaKLC2.2 had one hit), but hits were present in both 2-4 and 4-8 hr samples. This profile was validated by RT-PCR using 1 hr time intervals from 0-11 hr embryos (Figure 3, only AaKLC2.1 is shown). Furthermore, RT-PCR with RNA from other tissues and life stages shows that their expression is restricted to the early embryo. Transcription begins as early as 2-3 hr and only a faint band can be detected at 6-7 hr, with the large majority of intensity found during the 3-5 hr time range. AaKLC2.2 has an almost identical expression profile to AaKLC2.1 according to RT-PCR (not shown). RT-PCR products were cloned, sequenced, and verified to be specific for each transcript. These data support that AaKLC2 genes are early zygotic transiently expressed genes whose expression is restricted to the early embryonic life stage. In contrast, AaKLC1 is expressed in all developmental stages and tissues surveyed by RT-PCR. It also has significant presence in the 0-2 and 8-12 hr Illumina sample (Table 1).

Figure 3.

RT-PCR expression profile of the early zygotic kinesin light chain gene AaKLC2.1 and the ubiquitously transcribed paralog AaKLC1. Thirty cycles of PCR were performed on cDNA synthesized using total RNA isolated from different life stages and ovaries. Negative control reactions using primers for RPS7 and AaKLC2.1 with no reverse transcriptase were performed to check for genomic DNA contamination (not shown). RPS7-specific primers were used for a loading control (bottom). A) AaKLC2.1. Lanes 1-11, embryos collected at 0-1, 1-2, ... and 10-11 hr after egg deposition. Lane 12, 12-24 hr embryo; lane 13, 24-40 hr embryo; lane 14, 1-4th instar larvae; lane 15, 0-48 hr pupae; lane 16, ovary from newly emerged females (0-1 day old); lane 17, ovary from 3-4 day old females; lane 18, ovary from females 48 hr post blood meal; lane 19, carcass minus ovaries, 48 hr post blood meal; lane 20, ovary from females 72 hr post blood meal; lane 21, 0-5 day old males, lane 22, 0-5 day old females. Note the faint bands in lane 3 and 7 (2-3 hr and 6-7 hr embryo). B) AaKLC1. Lanes 1-15 (same as above); lane 16, 0-5 day old males; lane 17, 0-5 day old females; lane 18, ovary from females 48 hr post blood meal; lane 19, carcass minus ovaries, 48 hr post blood meal.

Expression data from ESTs and microarray experiments for KLC genes is consistent with the hypothesis that AaKLC2-like genes (Figure 1, left) are zygotic-specific genes and AaKLC1-like genes (Figure 1, right) are ubiquitously expressed genes (Table 2). Using BLAST by NCBI, EST hits for various life stages are detected for the AaKLC1-like genes in Table 2, and for the other holometabolous insects in Figure 2 (not shown). However, no EST hits for AaKLC2-like genes are detected. This is most likely simply explained by the lack of EST data from embryos. Microarray experiments covering developmental time periods for An. gambiae reveal expression for the AaKLC1-like but not for AaKLC2-like genes. These data further support the existence of two distinct types of KLC genes.

Table 2.

Evidence for Expression of Kinesin Light Chain Genes

| Species | Gene ID | Developmental Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Ae. aegypti | AAEL011410 (AaKLC2.1) | early embryo1 |

| Ae. aegypti | AAEL014967 (AaKLC2.2) | early embryo1 |

| Ae. aegypti | AAEL012472 (AaKLC1) | all life stages1 |

| An. gambiae | AGAP010258 (AaKLC1-like) | various developmental stages2 |

| D. melanogaster | FBgn0010235 (AaKLC1-like) | various developmental stages3 |

1 These data are from RT-PCR and transcriptome profiling described in this study

2 Expression in various developmental stages/tissues including adult is also reported by various microarray experiments [26-30] from http://www.vectorbase.org/index.php, and from the Anopheles gambiae gene expression profile database from UC Irvine, http://www.angaged.bio.uci.edu/)

3 From EST hits by BLAST on NCBI http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

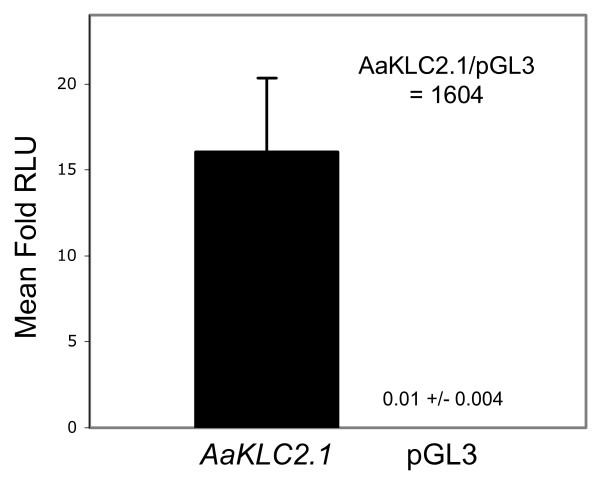

Early zygotic promoter activity of AaKLC2.1 upstream sequence in Ae. aegypti embryos

The 1 kb upstream sequence relative to the predicted start codon of AaKLC2.1 was synthesized (Epoch Biolabs, INC) to test for promoter activity. This sequence was cloned into the pGL3-basic luciferase reporter vector, injected into Ae. aegypti embryos, and assayed for luciferase activity. AaKLC2.1 upstream sequence clearly demonstrates promoter activity, as the mean fold activity of AaKLC2.1_pGL3-basic is 1604X greater than the empty vector alone (Figure 4). The 1 kb upstream sequence for AaKLC2.2 was also tested and it demonstrated similar activity (not shown). Several independent experiments have demonstrated the activity of these sequences and we are now working towards defining the minimal promoter sequence. The transcription profile of AaKLC2.1 is solely zygotic (Figure 3A) and the reporter assay clearly indicates early zygotic activity of the AaKLC2.1 promoter. However, the transient assay described here does not directly test whether the promoter is solely zygotic. Transgenic lines of Ae. aegypti are needed to directly answer such a question.

Figure 4.

Early zygotic promoter activity of AaKLC2.1 upstream sequence in Ae. aegypti embryos. Embryos were injected in triplicate with either one of the following firefly luciferase reporter plasmids: pGL3-basic only (negative control, shown as pGL3) or pGL3-basic containing 1042 bp of AaKLC2.1 5'UTR and upstream sequence. A Renilla luciferase reporter pRL-null containing D. melanogaster actin 5C promoter was used as an injection control. Embryos were homogenized and assayed at 5 hr after deposition. Mean fold relative light units (RLUs) +/- standard error is shown. The mean fold RLU is calculated as the ratio of the firefly luciferase activity to the Renilla luciferase activity. The mean fold activity of AaKLC2.1 was 1604 times greater than pGL3-basic.

Discussion

A novel set of purely zygotic genes: duplications, fast evolution, and possible function

AaKLC2-like genes are only found in Culicinae mosquitoes Ae. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus. However the AaKLC1-like genes are found in all surveyed holometabolous insects and are quite conserved in their structure and expression profiles. Thus it is likely that AaKLC2 genes are the paralogs that took on a new expression profile and possibly a new function in Culicinae. It is also interesting that in addition to the duplication that gave rise to the AaKLC2 gene lineage, there has been another duplication resulting in AaKLC2.1 and AaKLC2.2.

The AaKLC2-like genes appear to be fast-evolving genes according to their branch length (Figure 2). For example, AaKLC2.1 and the C. quinquefasciatus AaKLC2-like gene (CPIJ002971) have 44% aa identity, while AaKLC1 and the C. quinquefasciatus AaKLC1-like gene (CPIJ015771) have 94% aa identity. A curious question is whether AaKLC2-like genes have been under positive selection. However, we were unable to perform nonsynonymous/synonymous (dN/dS) analysis due to the divergence of the AaKLC2 and the C. quinquefasciatus CPIJ002971.

The presence of at least one highly conserved KLC gene (e.g. AaKLC1-like) in all of insects is not surprising given its indispensable role in intracellular transport, but it is interesting why a novel zygotic-specific KLC arose in Culicinae. The genome sizes of Ae. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus are approximately three and two times larger than An. gambiae [18] possibly providing more evolutionary freedom for gene expansion early in Culicinae. A large proportion of Drosophila early and transient zygotic genes were found to be involved in neurogenesis and dorso-ventral patterning [2]. Also noteworthy is that a KLC gene has been implicated in translocation of dorsal determinants in Xenopus [19]. Although we do not have experimental evidence of AaKLC2 function in the embryo, it seems plausible that these genes may play a similar role in early embryonic development, given their early and transient zygotic-specific expression profile. Specialization of KLC genes is a recurrent event in evolution. In rat and mouse it was found that KLC3 is restricted to spermatid tails while KLC1 and KLC2 are only found in testis before meiosis [20]. A rat KLC isoform was found to associate with mitochondria in cultured cells [21]. In mouse it was also found that two KLCs were present in the central and peripheral nervous system, but one is enriched in sciatic nerve exons and the other is enriched in the olfactory bulb glomeruli [22]. These examples of KLC specialization are from mammals and are consistent with the KLC diversity in mammals demonstrated in Figure 2. Therefore, the fact that we can only find one conserved KLC gene in holometabolous insects (AaKLC1) underscores the generation of AaKLC2 genes as an interesting evolutionary event, demonstrating the potential for KLC specialization in this taxonomic group.

Potential applications of an early zygotic promoter in the context of the Medea gene drive system

We demonstrated that the promoter region of the two AaKLC2 genes can direct early zygotic transcription in the Ae. aegypti embryo. Thus this promoter may be useful to direct the expression of the antidote gene as part of the Medea gene drive system [12,13]. The AaKLC2 genes are expressed specifically, transiently, and early in the embryonic stage, which makes them good candidates to drive the antidote expression. The antidote needs to be delivered at the appropriate time for embryonic rescue, providing the replacement of mRNA that was targeted by the maternal toxin. In addition, lack of antidote expression in the ovary will eliminate antagonist effects to the toxin. Lastly, purely zygotic expression will eliminate concerns of ectopic expression that could reduce fitness and thus reduce gene drive efficiency.

Conclusions

We have discovered a novel set of KLC genes in Ae. aegypti that we call AaKLC2.1 and AaKLC2.2, and have demonstrated that they are purely zygotic. These are the first reported in any mosquito species and they have a newly evolved expression pattern relative to the AaKLC1 genes. We have also identified a likely AaKlC2 gene ortholog in C. quinquefasciatus. Its similar structure and lack of representation in ESTs suggests that it is also a zygotic gene. AaKLC2-like genes appear to be restricted to Culicinae, as they are not detected in An. gambiae or An. stephensi, or other genome sequences. Genomic survey of more species and additional expression analyses will be needed to test these hypotheses. Data from ESTs and hybridization experiments in addition to our transcriptome and expression analysis by RT-PCR support the existence of two distinct KLC gene groups, the zygotic AaKLC2-like genes, and the highly conserved AaKLC1-like genes that are found in all mosquitoes and insects surveyed. We also demonstrated strong promoter activity of the AaKLC2 gene upstream sequence in Ae. aegypti early embryos. Large-scale transcriptome profiling has proven to be a valuable method for the identification of early and transient zygotic-specific genes. These technologies have allowed us to rapidly achieve results for a specific objective. Moreover, as we are currently acquiring and analyzing more transcriptome data, we will be able to investigate the complex and dynamic expression of genes in the early embryo and conduct comparative evolutionary studies with other mosquito species and Drosophila.

Methods

Illumina Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated using TRIZOL RNA isolation reagent (Molecular Research Center) from Ae. aegypti Liverpool strain embryos at time points 0-2, 2-4, 4-8, and 8-12 hr. RNA was sent to Illumina (illumina.com) for poly-A RNA transcriptome sequencing. Approximately 4.4-6.1 million mappable reads of 33 nt in length were obtained per sample (Additional File 1). Annotated transcripts were used as queries for blastn searches against the Illumina transcriptome sequence reads in different samples, to count the number of sequence reads per annotated transcript per sample. E-value of 1e-7 was used as cutoff for the BLAST analysis. Normalization method is described in the footnotes of Table 1. See Additional File 1 for a tabulated summary of the Illumina RNA sequence data and Additional File 2 for a FASTA file of the Illumina reads that matched the three KLC transcripts AAEL011410, AAEL014967, and AAEL012472.

Mosquito rearing and embryo collection

Ae. aegypti Liverpool strain mosquitoes were reared in incubators at 28°C and 60% relative humidity on a 16 hr light/8 hr dark photoperiod. Larvae and pupae were fed Sera Micron Fry Food with brewer's yeast, and Purina Game Fish Chow. Mosquitoes were blood-fed on female Hsd:ICR (CD-1®) mice (Harlan Laboratories http://www.harlan.com). Embryos were collected anywhere from 72 to 96 hr post blood meal.

Phylogenetic Inference

Phylogenetic Inference was performed using MrBayes v3.1.2 [23]. A total of forty-one conceptually translated amino acid (aa) sequences were obtained from NCBI. Sequences were aligned using ClustalX v2.0 [24] (pairwise alignment parameters: gap opening = 10.0, gap extend = 0.1; multiple alignment parameters: gap opening = 10.0, gap extend = 0.2). The final alignment of approximately 400 aa used for phylogenetic inference was cropped to include obvious regions of conservation and contained the predicted TPR and Rab5-binding domains (see Additional File 3 for aa sequences and Additional File 4 for alignment in FASTA format). MrBayes was used to test 10 fixed-rate aa models, choosing the Jones model exclusively (posterior probability = 1.0) after running 700,000 generations. The tree is rooted using KLC sequences from two prokaryotic species.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated for different life stages and ovaries from Ae. aegypti Liverpool strain mosquitoes using the TRIZOL RNA isolation reagent (Molecular Research Center). RNA was treated with Turbo DNA-free (Ambion) to remove any residual genomic DNA. 1 ug total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit and Oligo dT20 (Invitrogen). The final 21 microliter (ul) reaction volume was diluted by adding 21 ul of nuclease-free H20. One ul of this was used for 30 cycles of PCR with Taq Polymerase, dNTPs, and 10× buffer (Takara). Genomic and transcript sequences from the Ae. aegypti genome [25] were retrieved from http://aaegypti.vectorbase.org/index.php and http://www.ensembl.org/index.html. A 467 base region of AaKLC2.1 (transcript ID: AAEL011410-RA) cDNA was amplified using forward primer 5'-CTACCAGAAGCCATCAAACAT-3' Tm = 60.5°C, and reverse primer 5'- GATTCACTGTCACCATTCTGTGT-3' Tm = 62.8°C. A 464 base region of AaKLC2.2 (transcript ID: AAEL011410-RA) cDNA was amplified using forward primer 5'- CCCGAAGCCATTAAACAC-3' Tm = 60.5°C and reverse primer 5'- TGATTCACTGTCACCATTCTGTAC-3' Tm = 62.7°C. Both of these PCR products were cloned and sequenced to verify the primer's specificity for each transcript. A 550 base region of AaKLC1 (transcript ID: AAEL012472-RA) cDNA spanning 3 introns was amplified using forward primer 5'- ACTATGTTGAACATCCTGGCTTTAG-3' Tm = 63.1°C, and reverse primer 5'- TCGATTTGTTCTCTTCTCTTTCTTC-3' Tm = 62.8°C. The expected genomic product size is 28.8 kb. As a control for cDNA synthesis and for gel loading, a 562 base region of the ribosomal protein S7 (RPS7) cDNA was amplified using forward primer 5'-ATGGTTTTCGGATCAAAGG-3' Tm = 61.3°C, and reverse primer 5'-GGAATTCGAACGTAACGTCAC-3' Tm = 63.2°C. The expected genomic size is 5.5 kb. Negative control reactions without the use of reverse transcriptase were performed to test for genomic DNA contamination.

Embryonic injection and luciferase assay

Ae. aegypti Liverpool strain embryos were injected with pGL3-basic firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega) containing 1042 bp of the 5' UTR and upstream genomic sequence of the AaKLC2.1 early transient zygotic gene (gene ID: AAEL011410). For each injection group, an average of 45 embryos were injected at approximately 1 hr after deposition with 0.30 ug/ul of plasmid either with or without (negative control) insert. A Renilla luciferase reporter pRL-null (Promega) with the D. melanogaster actin promoter was used as an injection control at 0.15 ug/ul. 1× Injection Buffer used was 5 mM KCl 0.1 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.2, sterile filtered. Embryos were homogenized in Cell Culture Lysis Buffer at 3 hr and 5 hr after deposition and assayed for luciferase activity using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and a Glomax 20/20 luminometer (Promega). Samples were read for 10 seconds. Injection needles were pulled from World Precision Instruments Kwik-Fil Borosilicate Glass Capillaries (item # 1B100F-4) on a Sutter Instrument P-2000 Micropipette Puller at the following settings: Heat = 270, Fil = 3, Vel = 37, Del = 250, Pul = 134. Injections were performed using an Eppendorf FemtoJet allowing injection solution to free-flow through the needle with the compensation pressure (Pc) set at ~3750 hPa. Injection Pressure setting (Pi) not used. The needle is held in a World Precision Instruments Micromanipulator (model M3301L) http://www.wpiinc.com. Microscope used was a Leica CM E.

Authors' contributions

JB performed sequence analysis, phylogenetic inference, RT-PCR, luciferase assays, and wrote the manuscript. ZT conceived and oversaw the project, planned the embryonic transcriptome sequencing, analyzed the transcriptome data, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author's Information

JB is a Research Scientist at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

ZT is a Professor at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Supplementary Material

Summary of Illumina RNA sequence data.

FASTA file of Illumina reads that matched the three KLC transcripts.

FASTA file of amino acid sequences used in this study.

FASTA file of amino acid sequence alignment used for phylogenetic inference.

Contributor Information

James K Biedler, Email: jbiedler@vt.edu.

Zhijian Tu, Email: jaketu@vt.edu.

Acknowledgements

We thank Randy Saunders for help with embryo injections for the luciferase assay and Dr. Chunhong Mao for bioinformatics help. This work was supported by FNIH grant GC7 #316, and the Virginia Experimental Station.

References

- De Renzis S, Elemento O, Tavazoie S, Wieschaus EF. Unmasking activation of the zygotic genome using chromosomal deletions in the Drosophila embryo. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(5):e117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SD, Boue S, Krause R, Jensen LJ, Mason CE, Ghanim M, White KP, Furlong EE, Bork P. Identification of tightly regulated groups of genes during Drosophila melanogaster embryogenesis. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:72. doi: 10.1038/msb4100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier AF. The maternal-zygotic transition: death and birth of RNAs. Science. 2007;316(5823):406–407. doi: 10.1126/science.1140693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieschaus E. Embryonic transcription and the control of developmental pathways. Genetics. 1996;142(1):5–10. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Bosch JR, Benavides JA, Cline TW. The TAGteam DNA motif controls the timing of Drosophila pre-blastoderm transcription. Development. 2006;133(10):1967–1977. doi: 10.1242/dev.02373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raminani LN, Cupp EW. Early Embryology of Aedes aegypti (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae) International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology. 1975;4(6):517–528. doi: 10.1016/0020-7322(75)90028-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard DK, Schubiger G. Activation of transcription in Drosophila embryos is a gradual process mediated by the nucleocytoplasmic ratio. Genes Dev. 1996;10(9):1131–1142. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woehlke G, Schliwa M. Walking on two heads: the many talents of kinesin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1(1):50–58. doi: 10.1038/35036069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickstead B, Gull K. A "holistic" kinesin phylogeny reveals new kinesin families and predicts protein functions. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(4):1734–1743. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. Analysis of the kinesin superfamily: insights into structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(9):467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A, Goldstein LS. Principles of cargo attachment to cytoplasmic motor proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(01)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeman RW, Friesen KS, Denell RE. Maternal-effect selfish genes in flour beetles. Science. 1992;256(5053):89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1566060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Huang H, Ward CM, Su JT, Schaeffer LV, Guo M, Hay BA. A synthetic maternal-effect selfish genetic element drives population replacement in Drosophila. Science. 2007;316(5824):597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1138595. 10.1126/science. 1138595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt RA, Subramanian GM, Halpern A, Sutton GG, Charlab R, Nusskern DR, Wincker P, Clark AG, Ribeiro JM, Wides R. et al. The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298(5591):129–149. doi: 10.1126/science.1076181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci C, Parton RG, Mather IH, Stunnenberg H, Simons K, Hoflack B, Zerial M. The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell. 1992;70(5):715–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90306-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorvel JP, Chavrier P, Zerial M, Gruenberg J. rab5 controls early endosome fusion in vitro. Cell. 1991;64(5):915–925. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90316-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson DW, DeBruyn B, Lovin DD, Brown SE, Knudson DL, Morlais I. Comparative genome analysis of the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti with Drosophila melanogaster and the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae. J Hered. 2004;95(2):103–113. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver C, Farr GH, Pan W, Rowning BA, Wang J, Mao J, Wu D, Li L, Larabell CA, Kimelman D. GBP binds kinesin light chain and translocates during cortical rotation in Xenopus eggs. Development. 2003;130(22):5425–5436. doi: 10.1242/dev.00737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junco A, Bhullar B, Tarnasky HA, van der Hoorn FA. Kinesin light-chain KLC3 expression in testis is restricted to spermatids. Biol Reprod. 2001;64(5):1320–1330. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.5.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodjakov A, Lizunova EM, Minin AA, Koonce MP, Gyoeva FK. A specific light chain of kinesin associates with mitochondria in cultured cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9(2):333–343. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Friedman DS, Goldstein LS. Two kinesin light chain genes in mice. Identification and characterization of the encoded proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(25):15395–15403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(12):1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nene V, Wortman JR, Lawson D, Haas B, Kodira C, Tu ZJ, Loftus B, Xi Z, Megy K, Grabherr M. et al. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science. 2007;316(5832):1718–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinotti O, Nguyen QK, Calvo E, James AA, Ribeiro JM. Microarray analysis of genes showing variable expression following a blood meal in Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2005;14(4):365–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neira Oviedo M, Ribeiro JM, Heyland A, VanEkeris L, Moroz T, Linser PJ. The salivary transcriptome of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae: A microarray-based analysis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39(5-6):382–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou D, Schlegelmilch T, Christophides GK, Kafatos FC. Functional genomic analysis of midgut epithelial responses in Anopheles during Plasmodium invasion. Curr Biol. 2005;15(13):1185–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsos AC, Blass C, Meister S, Schmidt S, MacCallum RM, Soares MB, Collins FH, Benes V, Zdobnov E, Kafatos FC. et al. Life cycle transcriptome of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae and comparison with the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(27):11304–11309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703988104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassone BJ, Mouline K, Hahn MW, White BJ, Pombi M, Simard F, Costantini C, Besansky NJ. Differential gene expression in incipient species of Anopheles gambiae. Mol Ecol. 2008;17(10):2491–2504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of Illumina RNA sequence data.

FASTA file of Illumina reads that matched the three KLC transcripts.

FASTA file of amino acid sequences used in this study.

FASTA file of amino acid sequence alignment used for phylogenetic inference.