Abstract

A 1:1 mixture of [P(t-Bu)2o-biphenyl]AuCl and AgSbF6 catalyzes the intermolecular amination of allylic alcohols with 1-methyl-imidazolidin-2-one and related nucleophiles that, in the case of γ-unsubstituted or γ-methyl-substituted allylic alcohols, occurs with high γ-regioselectivity and syn-stereoselectivity.

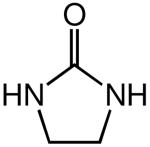

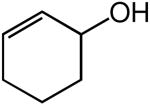

There has been an ongoing interest in the direct catalytic amination of underivatized allylic alcohols as a route to allylic amines and related derivatives.1 Initial headway in this area was realized through the in situ activation of the hydroxyl functionality with Lewis acid co-catalysts.2 In 2002 Ozawa reported the amination of allylic alcohols with anilines catalyzed by a cationic Pd(II) π-allyl complex in the absence of Lewis acidic co-catalysts.3 Since this time, a number of metals including Pd(0),4 Pt(II),5 Mo(VI),6 Bi(III),7 Au(I), and Au(III)8 have been shown to catalyze the intermolecular amination of underivatized allylic alcohols without the assistance of a Lewis acidic co-catalyst.9 Although a number of these transformations display high regio- and/or stereoselectivity, regiospecific amination of allylic alcohols remains problematic, presumably due to the intermediacy of π-allyl complexes or allylic carbocations. Here we describe a gold(I)-catalyzed protocol for the intermolecular amination of allyl alcohols with 1-methyl-imidazolidin-2-one (1) and related nucleophiles that, in the case of γ-unsubstituted or γ-methyl-substituted allylic alcohols, occurs with high γ-regioselectivity and syn-stereoselectivity.10

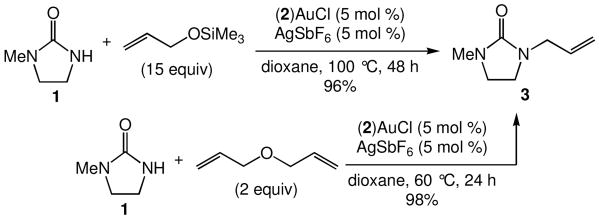

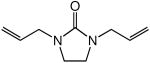

We recently reported the intermolecular hydroamination of unactivated 1-alkenes with cyclic ureas catalyzed by gold(I) o-biphenyl phosphine complexes.11 As part of our ongoing efforts to expand the scope of intermolecular alkene hydroamination, we investigated the gold(I)-catalyzed reaction of cyclic ureas with allylic ethers. However, reaction of 1 with either allyloxytrimethylsilane or diallyl ether catalyzed by a 1:1 mixture of (2)AuCl [2 = P(t-Bu)2o-biphenyl] and AgSbF6 gave none of the anticipated hydroamination products but instead led to allylic amination with isolation of 1-allyl-3-methyl-imidazolidin-2-one (3) in >95% yield (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

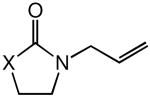

The efficient amination of both allyloxytrimethylsilane and diallyl ether suggested that unprotected allylic alcohols might also undergo gold(I)-catalyzed allylic amination. Indeed, reaction of 1 with allyl alcohol (1 equiv) catalyzed by (2)AuCl/AgSbF6 at 60 °C for 2 h led to isolation of 3 in 99% yield (Table 1, entry 1).12 In addition to 1, oxazolidin-2-one, imidazolidin-2-one, and primary and secondary sulfonamides underwent efficient gold(I)-catalyzed allylation with allylic alcohol (Table 1, entries 2, and 4 - 7). Pyrrolidin-2-one and benzyl carbamate also underwent gold(I)-catalyzed allylation with allylic alcohol, albeit with diminished efficiency (Table 1, entries 3 and 8).

Table 1.

Amination of allyl alcohol (2 equiv) as a function of nucleophile catalyzed by a mixture of (2)AuCl (5 mol %) and AgSbF6 (5 mol %) in dioxane.

| entry | nucleophile | product | temp (°C) | time (h) | yield (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| 1 | X = NMe (1) | 60 | 2 | 99b | |

| 2 | X = O | 100 | 48 | 98 | |

| 3 | X = CH2 | 80 | 48 | 42 | |

| 4 |

|

|

60 | 24 | 100 |

| 5 | TsNMeH |

|

100 | 24 | 99 |

| RNH2 |

|

||||

| 6 | R = Ts | 100 | 48 | 78 | |

| 7 | R = 4-MeOC6H4SO2 | 100 | 24 | 80c | |

| 8 | R = Cbz | 100 | 72 | 23 |

Isolated material of >95% purity.

One equivalent of allyl alcohol employed.

N,N-Diallyl-4-methoxybenzenesulfonamide was also isolated in 20% yield.

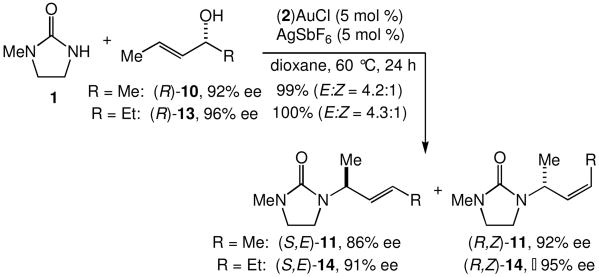

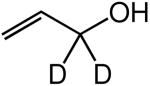

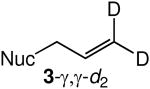

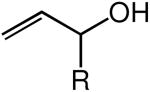

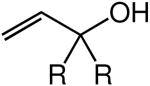

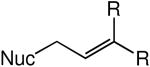

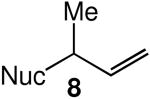

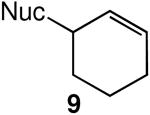

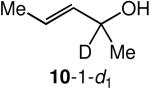

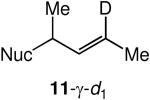

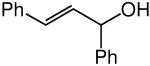

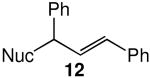

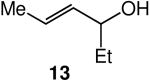

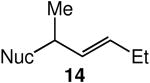

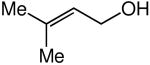

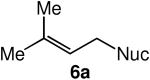

We evaluated the scope and stereospecificity of the gold(I)-catalyzed allylation of 1 as a function of allylic alcohol (Table 2). In the cases of γ-unsubstituted or γ-methyl substituted allylic alcohols, amination occurred selectively at the γ-carbon atom of the allylic alcohol. For example, gold(I)-catalyzed reaction of 1 with 1,1-dideuterio-2-propenol led to exclusive formation of 1-(3,3-dideuterio-2-propenyl)-3-methyl-imidazolidin-2-one (3-γ,γ-d2) (Table 2, entry 1). Likewise, gold(I)-catalyzed amination of 3-buten-2-ol with 1 led to exclusive formation of the N-2-butenyl urea 4 while amination of 2-buten-1-ol with 1 formed exclusively the N-(1-methyl-2-propenyl) urea 8 (Table 2, entries 2 and 6). Gold(I)-catalyzed reaction of 1 with 2-deuterio-3-penten-2-ol (10-1-d1) formed allylic urea 11-γ-d1 as the exclusive product (Table 2, entry 8) while gold(I)-catalyzed reaction of 1 with 4-hexen-3-ol (13) led to exclusive formation of urea 14 (Table 2, entry 10). Conversely, gold(I)-catalyzed amination of cinnamyl alcohol with 1 led to exclusive formation of α-substitution product 5 whereas gold(I)-catalyzed reaction amination of 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol with 1 led to formation of a 12:1 mixture of α-substitution product 6a and γ-substitution product 6b in quantitative yield (Table 2, entries 11 and 12).

Table 2.

Allylation of 1-methyl-imidazolidin-2-one (1) as a function of allylic alcohol catalyzed by a mixture of (2)AuCl (5 mol %) and AgSbF6 (5 mol %) in dioxane (Nuc = N-methyl-imidazolidin-2-one).

| entry | alcohol | major product | conda | yield (%)b | γ/α ratioc | E/Z ratioc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

A | 99 | >25:1 | — |

|

|

|||||

| 2 | R = Me | 4 | B | 91 | >25:1 | 2.4:1 |

| 3 | R = Ph | 5 | B | 94 | >25:1 | 6.7:1 |

|

|

|||||

| 4 | R = Me | 6a | A | 100 | >25:1 | — |

| 5 | R = –(CH2)5– | 7 | A | 100 | >25:1 | — |

| 6 |

|

|

C | 85 | >25:1 | — |

| 7 |

|

|

D | 97 | — | — |

| 8 |

|

|

A | 100 | >25:1 | 3.7:1 |

| 9 |

|

|

A | 100 | — | >25:1 |

| 10 |

|

|

A | 100 | >25:1 | 4.3:1 |

| 11 |

|

|

D | 85 | <1:25 | >25:1 |

| 12 |

|

|

B | 100 | 1:12 | — |

Conditions: A = 2 equiv alcohol, 60 °C, 24 h; B = 1 equiv alcohol, 60 °C, 24 h; C = 2 equiv alcohol, 25 °C, 36 h; D = 2 equiv alcohol, 100 °C, 48 h.

Isolated material of >95% purity.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of the purified reaction mixture.

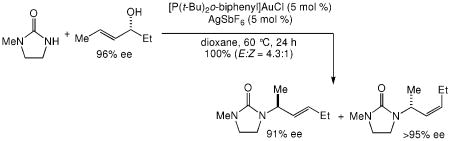

The presence of a γ-selective pathway in the gold(I)-catalyzed amination of γ-methyl substituted allylic alcohols pointed to the potential for 1,3-chirality transfer in these transformations. Indeed, two experiments employing enantiomerically enriched allylic alcohols established the preferential addition of urea to the alkene π-face syn to the departing hydroxyl group. In one experiment, gold(I)-catalyzed reaction of (R)-10 (92% ee) with 1 at 60 °C gave a 4.2:1 mixture of (S,E)-11 with 86% ee and (R,Z)-11 with 92% ee in 99% combined yield (Scheme 2). In a second experiment, gold(I)-catalyzed reaction of 1 with (R)-13 (96% ee) at 60 °C for 24 h led to isolation of a 4.3:1 mixture of (S,E)-14 with 91% ee and (R,Z)-14 with ≥95% ee in quantitative yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

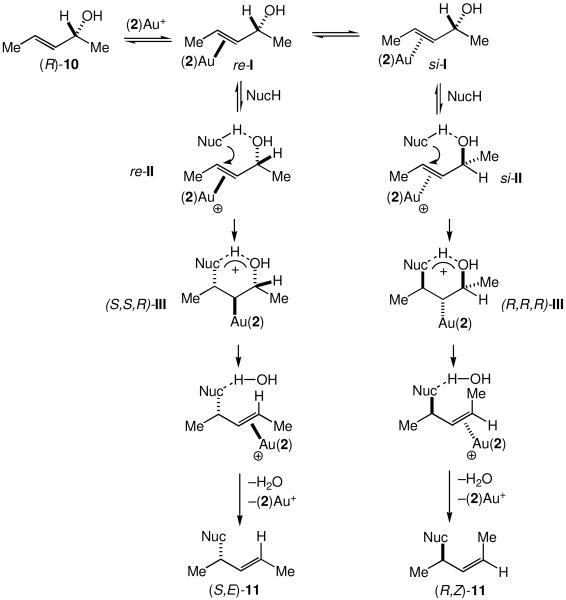

The stereochemical outcome of the gold(I)-catalyzed amination of (R)-10 and (R)-13 with 1 are characteristic of a concerted SN2′ substitution.13 However, a mechanism for the gold(I)-catalyzed γ-amination of allylic alcohols involving σ-activation of the hydroxyl group appears at odds with the low oxophilicity of gold(I), particularly considering the modest nucleophilicity of 1. Rather, a mechanism involving π-activation of the allylic C=C bond also accounts for the stereochemistry of gold(I)-catalyzed allylic amination and appears more in line with the pronounced π-acidity of cationic gold(I) complexes.14 Notably, Maseras has proposed a π-activation pathway for the gold(I)-catalyzed isomerization of allylic ethers with alcohols on the basis of DFT calculations.15 Guided by these results, we propose a mechanism for gold(I)-catalyzed allylic amination of (R)-10 initiated by formation of the gold(I) π-alkene complexes si-I and re-I (Scheme 3). Outer-sphere addition of 1 to si-I and re-I, facilitated by an N–H….O hydrogen bond (si-II and re-II),15 would form the cyclic, hydrogen-bonded gold alkyl intermediates (S,S,R)-III and (R,R,R)-III, respectively (Scheme 3). anti-Elimination of a hydrogen-bonded water molecule followed by displacement of gold would then release allylic ureas (S,E)-11 and (R,Z)-11 (Scheme 3). Preferential formation of (S,E)-11 relative to (R,Z)-11 presumably results from the unfavorable cis relationship of the gold moiety and the C1 methyl group in the transition state for formation of (R,R,R)-III that is absent in the transition state for formation of (S,S,R)-III.

Scheme 3.

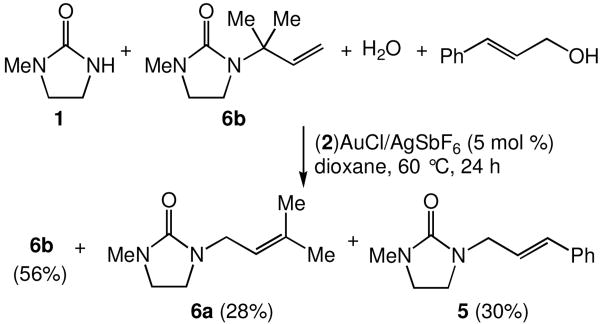

The π-activation mechanism for allylic amination outlined in Scheme 3 does not, however, account for the formation of α-substitution products, as was observed for the amination of cinnamyl alcohol and 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol (Table 2, entries 11 and 12). These α-substitution products may result from the presence of a Lewis acid-catalyzed reaction pathway involving carbocationic intermediates. Alternatively, we have obtained evidence for the formation of α-substitution product 6a in the gold(I)-catalyzed amination of 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol with 1 through indirect pathways, in particular, the isomerization of γ-addition product 6b under reaction conditions and the allylic transposition of 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol followed by γ-addition of 1. In support of the former pathway, an equimolar mixture of 1, 6b, cinnamyl alcohol, and water that contained a catalytic amount of (2)AuCl and AgOTf was heated at 60 °C in dioxane for 24 h.16 1H NMR analysis of the purified reaction mixture revealed a ∼2:1:1 mixture of unreacted 6b, cinnamyl urea 5 and isomerized urea 6a (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

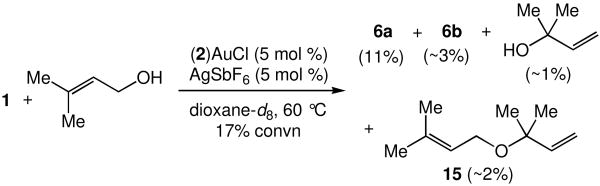

A pathway for formation of 6a in the gold(I)-catalyzed amination of 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol initiated by allylic transposition of 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol was validated through a second set of experiments. When an equimolar mixture of 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol and 1 that contained a catalytic amount of (2)AuCl and AgOTf was heated at 60 °C in dioxane-d8, 1H NMR analysis at low conversion (∼17%) revealed the presence of 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol and γ-alkoxylation product 15 that together accounted for ∼3% of the reaction mixture (Scheme 5). These compounds persisted throughout the conversion of 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol to 6a and 6b and were consumed at high conversion (∼95%). Importantly, gold(I)-catalyzed reaction of 1 with either 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol or 15 formed 6a as the exclusive product at rates that were ≥6 times greater than the rate of reaction of 1 with 3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol under comparable conditions.17

Scheme 5.

In summary, we have developed a gold(I)-catalyzed method for the amination of allyl alcohols with 1-methyl-imidazolidin-2-one (1) and related nucleophiles that proceedes in high yields under mild conditions. In the case of γ-unsubstituted or γ-methyl-substituted allylic alcohols, amination occurs with high γ-regioselectivity and syn-stereoselectivity. In the case of 3-methyl-2-butene-1-ol or cinnamyl alcohol, gold(I)-catalyzed amination led to predominant formation of α-amination products via secondary π-activation reaction pathways or through a Lewis acid catalysis involving carbocationic intermediates. We are currently working toward expanding the scope of gold(I)-catalyzed allylic amination with respect to nucleophile and toward the development of more general and more selective catalyst systems for the γ-amination of underivatized allylic alcohols.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment is made to the NIH (GM-080422) for support of this research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, analytical and spectroscopic data, and copies of HPLC traces and NMR spectra for new compounds (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Johannsen M, Jørgensen KA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1689. doi: 10.1021/cr970343o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Lu X, Lu L, Sun J. J Mol Catal. 1987;41:245. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lu X, Jiang X, Tao X. J Organomet Chem. 1988;344:109. [Google Scholar]; (c) Masuyama Y, Takahara JP, Kurusu Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:4473. [Google Scholar]; (d) Masuyama Y, Kagawa M, Kurusu Y. Chem Lett. 1995:1121. [Google Scholar]; (e) Itoh K, Hamaguchi N, Miura M, Nomura M. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1992;1:2833. [Google Scholar]; (f) Satoh T, Ikeda M, Miura M, Nomura M. J Org Chem. 1997;62:4877. doi: 10.1021/jo962387n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Yang SC, Hung CW. J Org Chem. 1999;64:5000. doi: 10.1021/jo990558t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yang SC, Tsai YC, Shue YJ. Organometallics. 2001;20:5326. [Google Scholar]; (i) Shue YJ, Yang SC, Lai HC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:1481. [Google Scholar]; (j) Stary I, Star IG, Kocovsky P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:179. [Google Scholar]; (k) Tsay S, Lin LC, Furth PA, Shum CC, King DB, Yu SF, Chen B, Hwu JR. Synthesis. 1993:329. [Google Scholar]; (l) Kimura M, Tomizawa T, Horino Y, Tanaka S, Tamaru Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:3627. [Google Scholar]; (m) Kimura M, Horino Y, Mukai R, Tanaka S, Tamaru Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10401. doi: 10.1021/ja011656a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Kimura M, Futamata M, Shibata K, Tamaru Y. Chem Commun. 2003:234. doi: 10.1039/b210920d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozawa F, Okamoto H, Kawagishi S, Yamamoto S, Minami T, Yoshifuji M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10968. doi: 10.1021/ja0274406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Muzart J. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:3077. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kinoshita H, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Org Lett. 2004;6:4085. doi: 10.1021/ol048207a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ozawa F, Ishiyama T, Yamamoto S, Kawagishi S, Murakami H, Yoshifuji M. Organometallics. 2004;23:1698. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kayaki Y, Koda T, Ikariya T. J Org Chem. 2004;69:2595. doi: 10.1021/jo030370g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Piechaczyk O, Doux M, Ricard L, le Floch P. Organometallics. 2005;24:1204. [Google Scholar]; (f) Thoumazet C, Grützmacher H, Deschamps B, Ricard L, le Floch P. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2006:3911. [Google Scholar]; (g) Piechaczyk O, Thoumazet C, Jean Y, le Floch P. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14306. doi: 10.1021/ja0621997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Mora G, Deschamps B, van Zutphen S, Le Goff XF, Ricard L, le Floch P. Organometallics. 2007;26:1846. [Google Scholar]; (i) Usui I, Schmidt S, Keller M, Breit B. Org Lett. 2008;10:1207. doi: 10.1021/ol800073v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Ohshima T, Miyamoto Y, Ipposhi J, Nakahara Y, Utsunomiya M, Mashima K. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14317. doi: 10.1021/ja9046075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Utsunomiya M, Miyamoto Y, Ipposhi J, Ohshima T, Mashima K. Org Lett. 2007;9:3371. doi: 10.1021/ol071365s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mora G, Piechaczyk O, Houdard R, Mezailles N, Le Goff XF, le Floch P. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:10047. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang H, Fang L, Zhang M, Zhu C. Eur J Org Chem. 2009:666. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin HB, Yamagiwa N, Matsunaga S, Shibasaki M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:409. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo S, Song F, Liu Y. Synlett. 2007:964. [Google Scholar]

- 9.See also: Defieber C, Ariger MA, Moriel P, Carreira EM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:3139. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700159.

- 10.For relevant examples of the gold-catalyzed addition of nucleophiles to allylic alcohols and related substrates see: Bandini M, Eichholzer A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9533. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904388.Aponick A, Li CY, Biannic B. Org Lett. 2008;10:669. doi: 10.1021/ol703002p.Aponick A, Li CY, Palmes JA. Org Lett. 2009;11:121. doi: 10.1021/ol802491m.Aponick A, Li CY, Malinge J, Marques EF. Org Lett. 2009;11:4624. doi: 10.1021/ol901901m.Lu Y, Fu X, Chen H, Du X, Jia X, Liu Y. Adv Synth Catal. 2009;351:129.Shu XZ, Liu XY, Xiao HQ, Ji KQ, Guo LN, Liang YM. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:243.Terrasson V, Marque S, Georgy M, Campagne JM, Prim D. Adv Synth Catal. 2006;348:2063.Georgy M, Boucard V, Debleds O, Dal Zotto C, Campagne JM. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1758.Kothandaraman P, Foo SJ, Chan PWH. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5947. doi: 10.1021/jo900917q.

- 11.Zhang Z, Lee SD, Widenhoefer RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5372. doi: 10.1021/ja9001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mixtures of (2)AuCl and AgOTf also catalyzed the conversion of 1 and allyl alcohol to 3 at 60 °C. Conversely, control experiments ruled out the contribution of acid- or silver-catalyzed pathways to the amination of allylic alcohol. Heating a mixture of 1 and allyl alcohol with a catalytic amount of 1) (2)AuCl, 2) AgSbF6, 3) a 1:1 mixture of AgSbF6 and 2, 4) HOTf or 5) a 1:1 mixture of HOTf and 2 in 1,4-dioxane (0.5 mL) at 100 °C for 24 h led to no detectable consumption of 1 or formation of 3.

- 13.(a) Magid RM. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:1901. [Google Scholar]; (b) Paquette LA, Stirling CJM. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:7383. [Google Scholar]

- 14.For examples of cationic, two-coordinate gold(I) π-complexes see: Brown TJ, Dickens MG, Widenhoefer RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6350. doi: 10.1021/ja9015827.Brown TJ, Dickens MG, Widenhoefer RA. Chem Commun. 2009:6451. doi: 10.1039/b914632f.Hooper TN, Green M, Mcgrady JE, Patel JR, Russell CA. Chem Commun. 2009:3877. doi: 10.1039/b908109g.Zuccaccia D, Belpassi L, Tarantelli F, Macchioni A. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3170. doi: 10.1021/ja809998y.de Frémont P, Marion N, Nolan SP. J Organomet Chem. 2009;694:551.

- 15.Paton RS, Maseras F. Org Lett. 2009;11:2237. doi: 10.1021/ol9004646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.These conditions mimic the reaction mixture at ∼50% conversion.

- 17.See Supporting Information for details regarding these experiments.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.