Using a structure–function analysis, we find that Rvs proteins are initially recruited to sites of endocytosis through their curvature-sensing and membrane-binding ability in a manner dependent on complex sphingolipids.

Abstract

BAR domains are protein modules that bind to membranes and promote membrane curvature. One type of BAR domain, the N-BAR domain, contains an additional N-terminal amphipathic helix, which contributes to membrane-binding and bending activities. The only known N-BAR-domain proteins in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Rvs161 and Rvs167, are required for endocytosis. We have explored the mechanism of N-BAR-domain function in the endocytosis process using a combined biochemical and genetic approach. We show that the purified Rvs161–Rvs167 complex binds to liposomes in a curvature-independent manner and promotes tubule formation in vitro. Consistent with the known role of BAR domain polymerization in membrane bending, we found that Rvs167 BAR domains interact with each other at cortical actin patches in vivo. To characterize N-BAR-domain function in endocytosis, we constructed yeast strains harboring changes in conserved residues in the Rvs161 and Rvs167 N-BAR domains. In vivo analysis of the rvs endocytosis mutants suggests that Rvs proteins are initially recruited to sites of endocytosis through their membrane-binding ability. We show that inappropriate regulation of complex sphingolipid and phosphoinositide levels in the membrane can impinge on Rvs function, highlighting the relationship between membrane components and N-BAR-domain proteins in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Key cellular processes such as cell division, movement, and vesicle formation require generation of a wide range of membrane curvatures. One protein module that is able to sense and stabilize local membrane curvature is the BAR (Bin Amphiphysin Rvs) domain and members of the BAR domain superfamily play important roles in membrane remodeling processes (for review see Dawson et al., 2006). Modulation of membrane curvature by the BAR domain is critical, as mutations in this domain of amphiphysin 2 cause centronuclear myopathy in humans (Nicot et al., 2007). However, the molecular mechanisms behind defects in BAR domain function remain unclear. Previous characterization of BAR domain proteins has generally involved overproduction, raising the need for in vivo studies characterizing the consequences of BAR domain mutations in genes expressed at their endogenous level.

Much of our current understanding of BAR domains comes from crystallographic and biochemical studies. (Peter et al., 2004; Gallop et al., 2006; Masuda et al., 2006; Henne et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007; Mattila et al., 2007). The BAR domain is an elongated banana-shaped dimer and most of the characterized BAR domain proteins function as homodimers. The dimerization angle of the two monomers varies among the members of the BAR superfamily and contributes to the degree of curvature induced by the BAR domain (Frost et al., 2008). Members of the BAR domain superfamily include BAR, N-BAR (N-terminal amphipathic helix-BAR), F-BAR (FCH-BAR or EFC extended-FCH) and I-BAR (inverse-BAR) domain proteins. The N-BAR domain can induce a high degree of curvature in membranes because it contains an amphipathic helix, which allows active induction of membrane curvature (McMahon and Gallop, 2005).

The curvature-inducing activity of BAR domains was demonstrated in experiments in which purified BAR domain proteins were able to bind membranes and promote formation of tubules in vitro (Takei et al., 1999; Peter et al., 2004). These activities depend on positive charges on the concave surface of the BAR domain and on the amphipathic helix, if it is present (Peter et al., 2004; Gallop et al., 2006; Masuda et al., 2006). BAR domains are thought to promote membrane curvature via two nonexclusive mechanisms. First, the modules bend membranes by imposing their curved, charged shapes over the membrane through electrostatic attraction (Peter et al., 2004; Mattila et al., 2007; Shimada et al., 2007; Frost et al., 2008). Second, curvature is induced by the amphipathic helix, which is thought to act as a wedge that penetrates into the outer leaflet of the lipid bilayer (Farsad et al., 2001; Gallop et al., 2006; Henne et al., 2007). In both mechanisms, promoting curvature of the large surface of a membrane is thought to require many BAR domains acting in concert. This has been confirmed by a cryo-electron microscopy analysis showing that F-BAR modules bind to membrane tubules by oligomerizing into helical coats around the curved membrane (Frost et al., 2008).

In S. cerevisiae, the only known N-BAR-domain proteins are the amphiphysin homologues, Rvs161 and Rvs167, which form a heterodimer through their BAR domains (for review see Ren et al., 2006). Although two-hybrid studies have suggested an interaction between Rvs167 and Rvs167 (Colwill et al., 1999; Bon et al., 2000), several pieces of in vivo evidence suggest that Rvs161 and 167 form an obligate heterodimer: 1) no homodimers of either Rvs161 or Rvs167 can be detected by coimmunoprecipitation of either protein from log phase cells (Friesen et al., 2006); 2) each Rvs protein is destabilized in the absence of the other partner (Lombardi and Riezman, 2001); 3) each Rvs protein is insoluble when expressed in heterologous systems in the absence of the other partner (Friesen et al., 2006). The overall domain architecture of Rvs161 and Rvs167 is distinct: Rvs161 consists solely of a BAR domain, whereas Rvs167 is composed of a BAR domain followed by a region rich in glycine, proline, and alanine (GPA), and an SH3 (Src-homology 3) domain at its C-terminus (Bauer et al., 1993; see Figure 1A). The important function of Rvs167 resides in its BAR domain, as a version of Rvs167 containing only the BAR domain is able to largely complement rvs defects in polarizing the actin cytoskeleton, endocytosis, growth on salt, and sporulation (Sivadon et al., 1997; Colwill et al., 1999). In addition to these roles, Rvs161 plays a role during mating that is independent of Rvs167, but requires interaction with Fus2, a non-BAR-domain protein (Brizzio et al., 1998; Paterson et al., 2008). The function of RVS161 in mating is separate from its role in endocytosis, as mutations in RVS161 have been identified that cause specific defects in either endocytosis or mating (Brizzio et al., 1998). Besides well-defined roles in endocytosis and mating, genetic and protein–protein interaction data suggest that Rvs may also be involved in secretion and vesicle trafficking processes involving several different cellular compartments (Friesen et al., 2005; Proszynski et al., 2005). In this work we refer to the domain generated through heterodimerization of Rvs161 and Rvs167 as a BAR domain.

Figure 1.

Rvs161-Rvs167 binds and tubulates liposomes in vitro. (A) Schematic diagram showing domain structures of Rvs161 and Rvs167. Rvs161 and Rvs167 form a heterodimer via their BAR domains. (B) Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of lipid cosedimentation assays. Purified Rvs161-Rvs167 at 2 μM was incubated with Folch (brain) liposomes with two different ranges of curvature, and the mixture was subjected to ultracentrifugation to separate the liposome-bound fraction (pellet, P) and the unbound fraction (supernatant, S). (C) Electron micrographs of synthetic liposomes (containing yeast-membrane composition; see Materials and Methods) incubated with 3 μM Rvs161-Rvs167. Liposomes form tubules ∼18–20 nm in diameter (arrow). Scale bar, 200 nm.

In growing yeast cells, Rvs161 and Rvs167 localize to cortical actin patches, which are sites of endocytosis (Brizzio et al., 1998; Balguerie et al., 1999; Kaksonen et al., 2005). Live-cell-imaging analysis tracking endocytic vesicle-marker dynamics in a large number of mutants has identified four protein modules that cooperate to drive the four distinct stages of endocytosis: formation of the vesicle coat, membrane invagination, actin meshwork formation, and vesicle scission (Kaksonen et al., 2005). In the vesicle-scission step, single rvs161Δ and rvs167Δ and double rvs161Δ rvs167Δ mutants have a specific and unique defect: a significant fraction of the endocytic patches begin to be internalized and move inward from the cell surface but are then retracted toward the cortex (Kaksonen et al., 2005). This abortive internalization in rvs mutants is thought to reflect a failure of scission after actin-driven invagination, at which point membrane tension retracts the endocytic patch back to the cell surface (Kaksonen et al., 2005). The biochemical mechanism by which Rvs161-Rvs167 promotes scission is not yet clear, but may involve interaction with specific lipid species such as phosphoinositides and sphingolipids.

A mechanochemical model for endocytosis (Liu et al., 2006, 2009) has proposed that Rvs161-Rvs167 binds to phosphoinositides [e.g., phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate; PI(4,5)P2] in the invaginating membrane and protects the underlying PI(4,5)P2 from hydrolysis by synaptojanin, Inp52. This “protective regulation” is proposed to generate a lipid phase boundary and interfacial force, inducing a higher curvature between the lipid phases, which then creates a positive feedback loop for synaptojanins to hydrolyze unprotected PI(4,5)P2 species at the interface. This in turn generates an even larger interfacial force, culminating in vesicle scission. Supporting this model, live-cell imaging has shown that Rvs167-green fluorescent protein (GFP) dynamics is altered in an inp51Δ inp52Δ mutant (Sun et al., 2007).

Sphingolipids also play a role in endocytosis and particularly in Rvs biology. Rvs161 localizes to detergent-resistant membranes in cell fractionation experiments and these fractions are enriched in complex sphingolipids and ergosterol (London and Brown, 2000; Balguerie et al., 2002; Germann et al., 2005). Furthermore, mutation of several genes in the sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway can suppress some rvs161Δ and rvs167Δ defects, suggesting a functional connection between Rvs and sphingolipids (Desfarges et al., 1993; Balguerie et al., 2002; Germann et al., 2005; McCourt et al., 2009; Morgan et al., 2009).

Despite significant progress made in the BAR domain field, the in vivo significance of the in vitro membrane-binding and -bending activities of BAR domains has not been well defined. To investigate this issue, we took an integrated approach, examining both the in vivo and in vitro functions of Rvs161-Rvs167 in the genetically accessible yeast system. We show that, like its metazoan counterparts, Rvs161-Rvs167 is able to bind and tubulate membranes in vitro. We identify a protein–protein interaction between BAR domains that provides strong evidence for oligomerization of Rvs proteins in vivo. Our phenotypic analysis of strains with mutations in RVS161 and RVS167 leads to a mechanistic model describing how Rvs may promote membrane scission by collaborating with membrane components at the sites of endocytosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of Rvs161-Rvs167

The expression plasmid for RVS161 and RVS167 was based on pDEST15, a Gateway vector designed to express genes with an N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag under the T7 promoter. We introduced a PreScission (GE Healthcare, Wuakesha, WI) protease cleavage site upstream of the RVS167 ATG in pDONR201-RVS167 so that the GST tag could be removed. A BglII fragment containing the T7 promoter driving expression of untagged RVS161 was inserted upstream of the T7 promoter driving RVS167 to give pDEST15+RVS161+RVS167 (BA1785). Coexpression of RVS161 and RVS167 in the Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) derivative, Overexpress C41(DE3), was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 4 h at 30°C. Cells were lysed in HN buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 2.5 mM DTT) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) using a high-pressure homogenizer, EmulsiFlex-C3 at 10,000–15,000 psi. GST-Rvs167-Rvs161 heterodimers were purified from the lysate using glutathione Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Avestin Inc., Ottawa, Canada) and Rvs161-Rvs167 dimer was cleaved from the GST tag, while protein was bound to the beads using PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare). Cleaved Rvs161-Rvs167 heterodimers were concentrated using Centricon filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

Vesicle Binding and Tubulation Assays

Lipid cosedimentation and tubulation assays were done as described (Henne et al., 2007). For the lipid cosedimentation assay, 2 μM Rvs161-Rvs167 protein was tested on Folch Fraction I–derived (bovine brain) liposomes filtered through 0.8- and 0.05-μm pores. For lipid tubulation assays, synthetic liposomes of yeast plasma membrane composition (17% phosphotidylcholine, 14% phosphotidylethanolamine, 27.7% phosphotidylinositol, 4% phosphotidylserine, 4.2% cholesterol, 2.5% phosphatidic acid, 30.7% sphingolipid) were incubated with 3 μM Rvs161-Rvs167 proteins.

Generation of Strains and Site-directed Mutagenesis

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Strains were obtained from the yeast gene-deletion collection (Winzeler et al., 1999) or were constructed using standard yeast genetic techniques (Sherman, 1991). Tagging, deletions, and insertions of genes were constructed by integrative transformation (Longtine et al., 1998). The rvs161 site-directed mutants were constructed using a Gene Editor mutagenesis kit (Promega, Madison, WI) in pRS316-RVS161 (Friesen et al., 2006), and rvs167 mutants were constructed in pDONR201-RVS167 (PreScission cleavage site inserted upstream of RVS167 ORF). Homologous recombination was used to integrate the rvs161 mutants in MATα strains in which the rvs161 open reading frame (ORF) had been replaced by URA3 and the natMX cassette (Goldstein and McCusker, 1999) had been inserted between 486 and 397 nt upstream of the RVS161 locus. The rvs167 mutants were made in MATa strains containing URA3 inserted between nt 95 and 890 of the RVS167 ORF and the hphMX cassette (Goldstein and McCusker, 1999) inserted between 301 and 311 nt downstream of the RVS167 ORF. The rvs161Δ::URA3 and rvs167Δ::URA3 strains were transformed with linear DNA fragments containing the mutated rvs161 or rvs167 ORFs and transformants in which the URA3 gene had been replaced were identified by replica plating from YPD to 5FOA-containing medium. To construct the rvs161-ΔN and rvs167-ΔN strain, the perfetto delitto technique (Storici et al., 2001) was used to integrate a double-stranded oligonucleotide, encoding a truncation of the 5′-end of the gene, into a strain in which the URA3 marker had replaced nt 1–57 of the gene. Proper integration of the mutants was confirmed by PCR. Double mutants were generated by crossing rvs161 mutants to the corresponding rvs167 mutants, diploids were sporulated and rvs161::Nat rvs167::Hph segregants identified by marker linkage. Chromosomal mutations were confirmed by sequencing. Strains for assaying bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) were constructed as described (Sung and Huh, 2007). We used growth assay on high salt to test whether C-terminal tagging interferes with Rvs function and found reduced fitness in RVS161-VC and RVS161-VN strains compared with the untagged strain.

Growth Medium, Western Blot Analysis, Spot Dilutions, and Limited-mating Assays

Standard methods and media were used for yeast growth and transformation (Guthrie and Fink, 1991). For Western blot analysis, 3 ml of cells were grown to midlog phase in YPD, pelleted, washed, and frozen. Whole cell extract was made from TCA-fixed cells as described (Kurat et al., 2009). Antibodies were polyclonal anti-Rvs167 (Lee et al., 1998), anti-Rvs161 (Riezman, 1985), anti-Swi6 (Madden et al., 1997), monoclonal anti-GFP (Living colors) and anti-Hexokinase (Rockland, Gibertsville, PA). For spot dilution assays, overnight cultures grown in YPD were serially diluted 20-fold and spotted onto the appropriate plates. Limited mating assays were done as described (Friesen et al., 2006).

Cell Biology

Actin staining was performed as described (Friesen et al., 2006) without added fluorescent brightener. Lucifer yellow (LY) uptake assays were done as described (Munn et al., 1995). In aureobasidin A (AbA)-treatment experiments, strains were grown to early log phase (OD600 = 0.2–0.3) in YPD at 30°C and then incubated with 0.2 μg/ml AbA, followed by incubation with shaking at 30°C for a designated time. In all live-cell imaging experiments, cells were grown in YPD to log phase, mounted on glass slides, and imaged at room temperature. Actin staining, LY uptake, GFP localization, and BiFC experiments were imaged using a DMI 6000B fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Deerfield, IL) equipped with a spinning-disk head, an argon laser (458, 488, and 514 nm; Quorum Technologies, Guelph, ON, Canada) and ImagEM charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu C9100-13, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan). Sixteen-bit images were analyzed using Volocity software (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom). For Rvs167-GFP patch density quantification, cells were imaged in 21 Z stacks with 0.3-μm intervals using confocal microscopy. Multiple Z series images were then used to construct three-dimensional images, which were used to calculate the total cell surface area using the measurement tool in the Volocity software. Patch numbers were determined by eye. Live-cell imaging and internalization and quantification of Sla1-GFP and Rvs167-GFP lifetimes were done as described (Kaksonen et al., 2005) and repeated three times; each time more than 150 Sla1-GFP patches were observed. Images were acquired continuously at rate of 1 frame/s to generate kymographs and movies.

RESULTS

Rvs161-Rvs167 Binds and Tubulates Membranes in Vitro

Reflecting their role in promoting three-dimensional changes in membrane curvature, amphiphysins can bind and tubulate liposomes in vitro (Takei et al., 1999; Razzaq et al., 2001; Peter et al., 2004). This binding is independent of liposome size, indicating that amphiphysins actively induce curvature (Peter et al., 2004). To test these activities, we coexpressed full-length Rvs161 and Rvs167 using an E. coli expression system and purified the complex. As we observed previously with Rvs161-Rvs167 purified from insect cells (Friesen et al., 2006), full-length Rvs161-Rvs167 was able to bind to Folch (bovine brain) liposomes in a cosedimentation assay (Figure 1B). Binding to liposomes extruded through polycarbonate membranes with pore sizes of 0.8 and 0.05 μm was equally efficient (Figure 1B) indicating that like amphiphysins, Rvs binds to membranes in a curvature-independent manner.

BAR domains are able to tubulate liposomes, a collective activity that requires many BAR domains to polymerize into coats around a curved membrane (Takei et al., 1999; Peter et al., 2004; Frost et al., 2008). To assay tubulation, we incubated purified Rvs protein complex with liposomes and looked for three-dimensional changes in the liposomes using electron microscopy. We were unable to detect tubules using our standard Folch liposomes so we tested synthetic liposomes that had a composition similar to that of the reported yeast plasma membrane (Patton and Lester, 1991). Rvs161-Rvs167 induced membrane tubule structures with a diameter of ∼18–20 nm in ∼15% of the synthetic liposomes (arrow, Figure 1C). Because the composition of the yeast plasma membrane is substantially different from that of Folch (Peter et al., 2004), our results suggest that membrane composition is important for Rvs161-Rvs167 tubulation activity. Together, our biochemical tests show that Rvs161-Rvs167 binds to membranes and induces three-dimensional curvature.

Rvs161-Rvs167 Forms a Higher Order Structure at Sites of Endocytosis

Bending membranes requires the combined action of many proteins, suggesting cooperativity between individual Rvs161-Rvs167 BAR domains. Because Rvs161 and Rvs167 form an obligate heterodimer, protein–protein interactions between Rvs161 and Rvs161 or between Rvs167 and Rvs167 would be detected only if the heterodimers can form oligomers. To assay Rvs oligomerization, we used a protein complementation assay, called bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC; for review see Kerppola, 2008), which provides information both on the presence of a physical interaction and its subcellular localization. The BiFC assay is based on the finding that two nonfluorescent fragments of a fluorescent protein can associate to form a fluorescent complex when they are fused to two proteins that interact with each other. Furthermore, the BiFC signal reveals the site of protein–protein interaction in live cells.

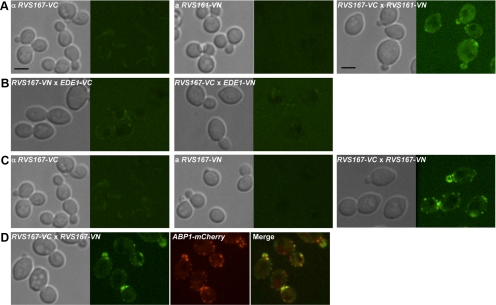

As a positive control, we first asked whether heterodimerization of Rvs161 and Rvs167 could be detected in the BiFC assay. We C-terminally tagged endogenous RVS161 with a cassette encoding the N-terminal portion of a yellow fluorescent protein, Venus (VN), and crossed it to a strain with RVS167 fused to a gene encoding the C-terminal portion of Venus (VC) and imaged the resulting diploid to look for Venus fluorescence. We observed fluorescence only in a diploid expressing both Rvs161-VN and Rvs167-VC (Figure 2A); this fluorescence localized to cortical patches that were moderately polarized, confirming that the Rvs161-Rvs167 heterodimer interaction can be detected using BiFC. An endocytic patch protein, Ede1, which does not interact with Rvs167, gave no BiFC signal with Rvs167 (Figure 2B), indicating that the interaction did not occur nonspecifically with proteins in the same subcellular compartment. Importantly, in our test for an Rvs167-Rvs167 interaction, we found a clear BiFC signal in a diploid expressing both Rvs167-VN and Rvs167-VC (Figure 2C). This Rvs167-Rvs167 BiFC signal colocalized with Abp1-mCherry (Figure 2D) indicating that the Rvs167-Rvs167 interaction occurs at sites of endocytosis. Together, these results indicate that Rvs167-Rvs167 interaction occurs specifically at sites of endocytosis and provide strong evidence for oligomerization of Rvs BAR domain proteins in vivo.

Figure 2.

Visualization of protein–protein interaction between Rvs proteins using BiFC analysis. (A) Protein-protein interaction between Rvs161 and Rvs167 was tested by mating haploid strains carrying alleles of RVS161 and RVS167 tagged at their C-termini with two nonfluorescent fragments of Venus (VN and VC). DIC and confocal microscopy images show haploids, RVS167-VC, RVS161-VN, and diploid cells formed by mating the two haploids from left to right. In the diploid (RVS167-VC × RVS161-VN), the interaction between Rvs161 and Rvs167 can be visualized at fluorescent cortical patches. Scale bar, 4 μm. (B) BiFC assay of interaction between Rvs167 and Ede1. Haploid strains, each harboring RVS167 or EDE1 tagged with VN and VC (or VC and VN), were used to test the interaction between Rvs167 and Ede1. DIC images on the left show diploids formed by mating these haploids and confocal images of the diploids are shown on the right. (C) Protein–protein interaction between Rvs167 and Rvs167. The BiFC assay was used to test Rvs167-Rvs167 interaction by mating haploid strains expressing RVS167-VC and RVS167-VN. DIC and confocal images show haploids (RVS167-VC and RVS167-VN) and diploid cells (RVS167-VC × RVS167-VN) from left to right. (D) Punctate fluorescence mediated by Rvs167-Rvs167 physical interaction colocalizes with actin-binding protein, Abp1-mCherry. DIC and confocal microscopy images of diploid cells harboring RVS167-VC, RVS167-VN and ABP1-mCherry.

Generating Structurally Motivated Mutations in the BAR Domains of RVS161 and RVS167

A number of mutations affect the in vitro activities of Drosophila and other amphiphysins (Peter et al., 2004); however, how these alterations affect amphiphysin function in vivo in the context of the endogenous gene is not known. Conversely, genetic experiments in yeast have uncovered mutations in RVS161 that specifically affect phenotypes associated with RVS161 deletion (Brizzio et al., 1998). In this case, a clear view of how these defects relate to known biochemical activities of the BAR domain has not yet emerged.

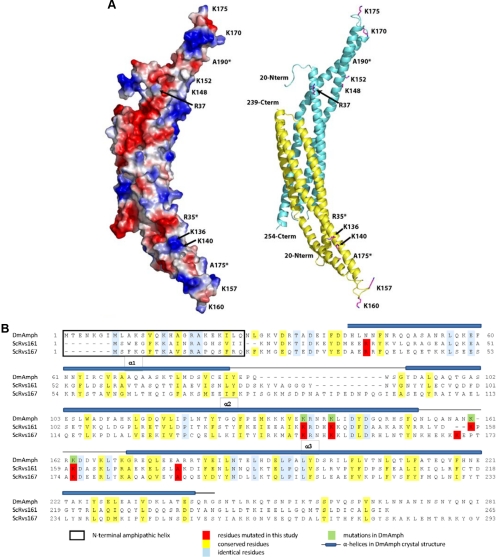

In an effort to provide an integrative view of the in vivo and in vitro functions of BAR domain proteins, we sought to explore the biological significance of the in vitro lipid binding and tubulation activities of Rvs161-Rvs167 using a structure-function approach. We generated a number of mutant alleles of RVS161 and RVS167 guided by alterations in the Drosophila amphiphysin (DmAmph) BAR domain that are known to reduce membrane binding (Peter et al., 2004): 1) truncation of the first 19 residues of Rvs161 or Rvs167, which are predicted to form the N-terminal amphipathic helix (ΔN); 2) substitutions of a highly conserved pair of lysine residues in the predicted concave surface on helix α2 with glutamic acid [K136 and K140 in Rvs161; K148 and K152 in Rvs167, referred to in this work as KE(con)]; 3) substitutions of a pair of conserved lysines in the predicted distal/extended loop between helices α2 and α3 with glutamic acid [K157 and K160 in Rvs161 and K170 and K175 in Rvs167; KE(loop)]; and 4) combined substitutions of basic to acidic amino acid residues on the concave surface and the loop [KE(con+loop)]. We also made two mutations that were previously shown to cause specific defects in RVS161 function (Brizzio et al., 1998). One mutant, rvs161-R35C (referred to in this work as RC), was wild-type for cell fusion during mating but defective in endocytosis, and the other, rvs161-A175P (referred to in this work as AP), was defective in fusion but wild-type for endocytosis (Brizzio et al., 1998; McCourt et al., 2009). We constructed these changes in both Rvs161 (R35C and A175P) and at analogous residues in Rvs167 (R37C and A190P; Figure 3; see Supplementary Table 1 for list of strains constructed).

Figure 3.

Structure-based mutations generated in Rvs161 and Rvs167 (A) Homology model of the Rvs161-Rvs167 BAR domain heterodimer. The Drosophila amphiphysin BAR domain homodimer structure (RCSB: 1uru) was used as a template to generate a homology model of Rvs161-Rvs167 BAR domain heterodimer. Both surface electrostatic (left) and cartoon (right) representations of the model are shown with Rvs161 colored in yellow and Rvs167 in cyan. The positions of residues mutated within this study are indicated (*Residues facing back of the structure.) (B) Sequence alignment of BAR domains of Rvs161 and Rvs167 alongside their homolog, Drosophila amphiphysin (DmAmph), showing residues changed in this study. The substitutions were based on previous studies done on RVS161 (Brizzio et al., 1998) and on DmAmph (Peter et al., 2004).

To gain insight into the potential structural effects of these mutations, we manually generated a homology model of the Rvs161-Rvs167 BAR domain heterodimer guided by the DmAmph BAR domain crystal structure (PDB: 1URU) and sequence alignment (Figure 3). The conserved lysine residues targeted for mutagenesis are positioned on the concave surface of the BAR domain model and the extended loop region between the α2 and α3 helices. These side chains are surface-exposed in both the DmAmph BAR crystal structure and the resulting Rvs161–167 homology model. Thus substitutions in these residues are not expected to alter the overall BAR domain structure. The side chain of the mutated R35C/R37C residue within helix α1, although not conserved in DmAmph, is likely surface-exposed and is not expected to contribute to the general structural integrity of the BAR domain. The A175P/A190P mutation within helix α3 may result in helical distortions but the effects on BAR domain structure could not be predicted or modeled with any degree of confidence. Thus, the predicted structure suggests that all of the substitutions we generated would have an insignificant effect on the overall structure of the BAR domain. Furthermore, we can assess whether the mutations affect protein stability or dimerization, as each Rvs protein is destabilized in the absence of the other in vivo (Lombardi and Riezman, 2001). Consistent with a minimal effect on overall BAR domain structure or stability, Western blot analysis showed that the Rvs161 and Rvs167 mutant proteins were present at levels comparable to wild type (Supplementary Figure 1, A and B). Furthermore, the double rvs161 rvs167 BAR domain mutant strains had levels of both proteins similar to those seen in wild type, suggesting that the physical interactions between the two monomers were intact (Supplementary Figure 1C). These results, coupled with our homology modeling, suggest that phenotypic defects seen in the various mutant strains likely reflect functional defects caused by perturbations of specific structural features of the BAR domain.

The N-Terminal Helix and Positive Charges in the Concave Surface and Loop of Rvs161 Play a Role in Cell Fusion

As noted above, Rvs161 has a function in cell fusion during mating that depends on its interaction with another protein, Fus2, and is independent of Rvs167 (Brizzio et al., 1998; Paterson et al., 2008). An rvs161Δ strain shows a bilateral mating defect, which becomes stronger when combined with fus1Δ, suggesting that these genes function in parallel pathways (Brizzio et al., 1998). To begin our phenotypic analysis of BAR domain function, we tested our panel of rvs161 BAR domain mutants for cell fusion defects using a limited mating assay. In this assay, MATα rvs161 BAR domain mutants are permitted to mate with MATa cells of a sensitized genetic background (in this case rvs161Δ fus1Δ) for a limited time, followed by selection for diploid cells. Because RVS167 is not required in this assay (Brizzio et al., 1998), we tested strains that were mutated only at the RVS161 locus and were wild type for RVS167. As reported previously (Brizzio et al., 1998), the rvs161-R35C mutant was competent for mating, whereas rvs161Δ and rvs161-A175P were defective (Supplementary Figure 2). KE substitutions in the concave face or loop moderately affected formation of diploids and this phenotype became more severe when they were combined [rvs161-KE(con+loop); Supplementary Figure 2]. The rvs161-ΔN mutant also displayed a defect in cell fusion as severe as that of the deletion mutant and failed to mate even after a longer incubation time at which all the other mutants were able to form diploids (data not shown). In DmAmph, the N-terminal amphipathic helix and positive charges in the concave face and loop are required for membrane interaction in vitro (Peter et al., 2004). Our results demonstrate that, in addition to A175, the motifs important for membrane interaction, are also involved in the activity of Rvs161 during cell fusion. This suggests that Rvs161, together with Fus2, may perform its role in mating through a membrane-modulating activity in a manner similar to the Rvs161–Rvs167 complex (Figure 1, B and C).

The BAR Domains in Rvs161 and Rvs167 Are Required for Their Role in Endocytosis

We next assessed how the BAR domain mutant alleles complemented previously known rvs161Δ and rvs167Δ phenotypic defects that are indicative of their role in endocytosis: 1) sensitivity to growth on high salt, 2) loss of actin polarity, and 3) a defect in the uptake of LY. We first used growth on salt-containing medium to compare the fitness defects of single mutants with those of double mutants to ask whether mutations from each monomer impinge on Rvs function as a heterodimer. With the exception of AP (which had no defect) and ΔN (which did not grow on salt), all changes in both RVS161 and RVS167 resulted in more severe defects than in single mutants (Supplementary Figure 3). This additive phenotype indicates that, consistent with the structure of amphiphysin, residues throughout both Rvs161 and Rvs167 contribute to BAR domain function. Given these results, we performed all phenotypic tests on strains that carried symmetrical changes in both Rvs161 and Rvs167 [referred to as KE(con)-KE(con), RC-RC, etc.].

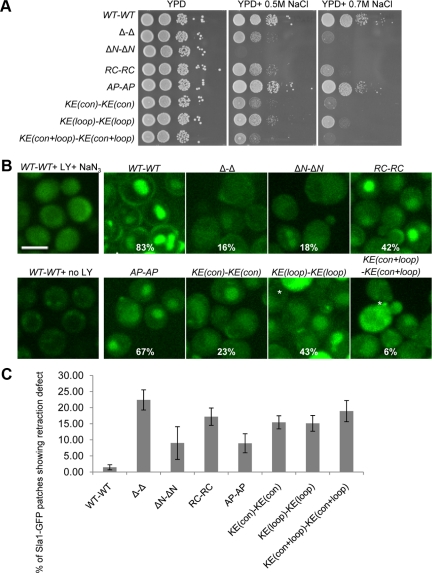

We first tested all Rvs161-Rvs167 double mutants for a slow-growth phenotype on salt-containing medium, which is known to correlate with defects in endocytosis and actin polarity (Whitacre et al., 2001). Consistent with previous results (Lee et al., 1998), the rvs161Δ rvs167Δ strain was unable to grow on medium containing 0.7 M NaCl (Figure 4A, right panel), whereas the RC-RC mutant was defective and the AP-AP mutant was competent for growth on salt-containing medium (Brizzio et al., 1998). The KE(con)-KE(con) and KE(con+loop)-KE(con+loop) mutants were also sensitive to salt, much like the double deletion strain, whereas the KE(loop)-KE(loop) mutant was partially defective. The most severe defect was seen with the ΔN-ΔN mutant, which was not able to grow under salt conditions that were sublethal for the deletion strain (Figure 4A, middle panel). These observations suggest that the N-terminal amphipathic helix and the basic residues on the concave face of the BAR domain may play a significant role in Rvs endocytosis-related function.

Figure 4.

The rvs161 rvs167 BAR domain mutants show defects in endocytosis. (A) Growth of BAR domain mutants on medium containing NaCl. Overnight cultures were serially diluted 20-fold and spotted onto YPD, YPD + 0.5 M NaCl, and YPD + 0.7 M NaCl and grown for 2 d (YPD) or 3 d (YPD+NaCl) at 30°C. (B) Single images of Lucifer yellow (LY) uptake assay. Mutants were incubated with LY dye for 2 h, the reaction was stopped, and cells were imaged using confocal microscopy; percentage of cells containing LY dye in their vacuoles (n > 200) is indicated. *Auto-fluorescence in dead cells. Scale bar, 4 μm. (C) BAR domain mutants exhibit a Sla1-GFP retraction phenotype as described for an rvs161Δ rvs167Δ double mutant (Kaksonen et al., 2005).

Mutants defective in endocytosis generally have defects in polarizing their actin cytoskeletons (Pruyne and Bretscher, 2000). We next stained filamentous actin in BAR domain mutants with rhodamine-phalloidin, and surveyed small-budded cells to determine whether they had defects in polarizing actin patches. Defects in actin polarity in RC-RC and AP-AP mutant strains corresponded well with the reported defects of rvs161 single mutants (Brizzio et al., 1998). Overall, the mutants displayed a range of defects in polarizing their actin patches that mirrored their growth defects on salt-containing medium (Supplementary Figure 4).

We also tested fluid-phase endocytosis in the rvs161 rvs167 BAR domain mutants using a LY uptake assay (Riezman, 1985). We observed efficient endocytosis in wild type and in the AP-AP mutant, as previously reported for a single rvs161-A175P mutant strain (Figure 4B; Brizzio et al., 1998). In contrast, all other BAR domain mutants had defects in LY uptake (Figure 4B). Quantification of cells with LY in the vacuole revealed that the most severe defects were seen in Δ-Δ, ΔN-ΔN, KE(con)-KE(con), and KE(con+loop)-KE(con+loop) mutant strains (Figure 4B). Overall, these results correlate well with growth on salt-containing medium (Figure 4A) and with actin polarity (Supplementary Figure 4), supporting the idea that the latter two assays reveal a function in the endocytosis process (Pruyne and Bretscher, 2000; Whitacre et al., 2001). Together, our tests reveal that the residues in BAR domain proteins that are important for binding and bending membranes are required for Rvs function in endocytosis.

Mutations in the BAR Domain Lead to Aberrant Endocytic Vesicle Dynamics

Live-cell imaging analysis with a variety of endocytosis proteins has enabled detailed study of the steps involved in endocytosis in yeast (Kaksonen et al., 2005). Sla1 is an early endocytic vesicle marker that goes through two phases of movement: 1) slow movement that is restricted to the site where the patch was formed and then 2) fast inward movement of ∼200 nm upon arrival of the actin patch protein, Abp1 (Kaksonen et al., 2003). The fast inward movement of Sla1 is thought to indicate vesicle internalization. Analysis of Sla1-GFP dynamics in different endocytic mutant backgrounds has revealed an rvs-specific phenotype: in rvs161Δ, rvs167Δ or the double rvs161Δ rvs167Δ mutant strain, about one-fourth of Sla1-GFP patches begin to move inward from the cell surface (as they do during wild-type endocytosis events) but are then retracted toward the cortex (Kaksonen et al., 2005). This abortive internalization of Sla1-GFP is interpreted as a failure of vesicle scission and distinguishes Rvs from other endocytic proteins (Kaksonen et al., 2005). Thus, in contrast to LY uptake, which assays the end point of endocytosis, Sla1-GFP retraction isolates the membrane-scission step of the endocytosis process.

To ask if BAR domain function is responsible for promoting vesicle scission, we analyzed the dynamics of Sla1-GFP retraction in our different BAR domain mutants. In wild-type cells, <1.5% of the puncta showed retraction, whereas we observed 22% retraction in rvs161Δ rvs167Δ (Figure 4C). All of the mutations in the BAR domain increased the frequency of Sla1-GFP retraction compared with wild type (Figure 4C). The ΔN-ΔN and AP-AP mutants had the mildest defect, with ∼10% of Sla1-GFP patches showing retrieval to the cortex, suggesting that these mutations moderately affect Rvs161-Rvs167 function in promoting membrane scission. The moderate Sla1-GFP retraction defect seen in the ΔN-ΔN mutant was unanticipated given its severe LY uptake defect. The other mutants, RC-RC, KE(con)-KE(con), KE(loop)-KE(loop), and KE(con+loop)-KE(con+loop), exhibited more severe defects: 15–19% of Sla1-GFP patches showed retraction back to the membrane, comparable to the defect seen in null mutants. Among the mutants with severe Sla1-GFP retraction defects, the RC-RC mutant phenotype was also unexpected as it had displayed a relatively moderate defect in LY uptake.

Together with the retraction movement, an extended Sla1-GFP lifetime was reported in rvs161Δ rvs167Δ (Kaksonen et al., 2005). The average lifetime of Sla1-GFP in the BAR domain mutants was also extended up to 1.6-fold relative to wild-type cells, with good correlation to their retraction defects (Supplementary Figure 5). In summary, the aberrant Sla1-GFP dynamics seen in RC-RC, KE(con)-KE(con), KE(loop)-KE(loop), and KE(con+loop)-KE(con+loop) mutants suggests a specific defect for these alleles in promoting membrane scission during the endocytosis process that may not be evident using more general endocytosis assays.

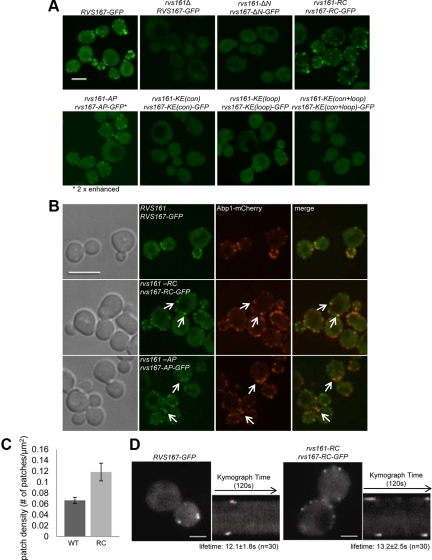

Only Rvs167-RC-GFP and Rvs167-AP-GFP Can Efficiently Localize to Sites of Endocytosis

The endocytosis defects of the BAR domain mutants may reflect defects in their localization, so we next assessed how changes in the BAR domain affected Rvs161-Rvs167 localization. Rvs167 localizes to cortical actin patches (Balguerie et al., 1999; Germann et al., 2005; Kaksonen et al., 2005), which are sites of endocytosis in yeast. We tagged Rvs167 at their C-termini with GFP in wild-type, rvs161Δ and different rvs161 rvs167 double mutant backgrounds. Analysis of protein levels and phenotypic assays confirmed that the GFP tag interfered minimally with Rvs167 function (Supplemental Figure 6, A and B). As previously reported, wild-type Rvs167-GFP localized in a punctate pattern on the cell surface and showed cell-cycle–dependent polarization to the bud (Figure 5A), where it partially colocalized with Abp1-mCherry (Figure 5B, top panel; Germann et al., 2005; Kaksonen et al., 2005). In an rvs161Δ strain, protein levels of Rvs167-GFP were reduced and Rvs167-GFP no longer localized to cortical patches, indicating that RVS161 was required for Rvs167 stability and localization (Figure 5A, second panel and Supplementary Figure 6A), as has been shown previously (Germann et al., 2005). Rvs167 localization has also been previously reported to be independent of Rvs161 (Balguerie et al., 1999). However, our finding that Rvs161 is required for proper localization of Rvs167 is consistent with the considerable evidence in this work and in the literature that Rvs function requires both Rvs161 and Rvs167 (Navarro et al., 1997; Lombardi and Riezman, 2001; Germann et al., 2005; Friesen et al., 2006).

Figure 5.

Localization of Rvs167-GFP in rvs161 rvs167 mutants. (A) Maximum intensity projections of Z-stacks of C-terminally GFP-tagged Rvs167 strains. The signal for Rvs167-AP-GFP is two-fold enhanced to show its cortical localization. Scale bar, 4 μm. (B) Single images of Rvs167-GFP, Rvs167-RC-GFP, and Rvs167-AP-GFP with actin patch marker, Abp1-mCherry. Scale bar, 4 μm. (C) Rvs167-GFP patch density [patch number/cell surface area (μm2) ± SD] in wild-type and rvs161-RC rvs167-RC cells (n ≥ 100, three independent repeats). (D) Rvs167-RC-GFP exhibits a specific defect in its internalization step. On the left, single frames from live-cell movies show localization of Rvs167-GFP and Rvs167-RC-GFP. The corresponding kymographs are shown on the right. Movies corresponding to these kymographs are in Supplementary Movie 1 and 2. Each kymograph shows the dynamics of two or four patches on opposite sides of a cell over 120 s. Scale bar, 2 μm.

The mutants with severe defects in endocytosis, ΔN-ΔN, KE(con)-KE(con), and KE(con+loop)-KE(con+loop), had no detectable Rvs167-GFP in cortical patches, despite showing wild-type levels of protein (Supplementary Figure 6A). In the endocytosis-competent mutant AP-AP, Rvs167-GFP localized to cortical patches, but with a reduced fluorescent signal, likely due to a moderate decrease in protein level (Supplementary Figure 6A). In the KE(loop)-KE(loop) mutant, which had a modest defect in endocytosis, Rvs167-GFP showed some localization to cortical patches (Figure 5A). We conclude that the N-terminal helix and the positive charges in the predicted concave regions of Rvs161 and Rvs167 are required for proper localization of Rvs167, possibly through physical interaction with the membrane. Overall, most of the mutants showed a good correlation between their ability to localize to actin patches and their endocytosis function.

In contrast, the RC-RC mutant displayed efficient localization of Rvs167-GFP to cortical patches with an obvious increase in patch density (Figure 5, A and C), despite its defects in endocytosis and in Sla1-GFP retraction. To test for possible defects associated with failure of membrane scission, we examined the localization of Rvs167-GFP in the RC-RC mutant (RC-GFP) in detail. To do this, we followed the spatial and temporal dynamics of RC-GFP and observed a defect in Rvs167 internalization in the RC-RC mutant. As expected, in wild-type cells, Rvs167-GFP patches appeared with maximal intensity at the cell surface and then went through a rapid inward movement of 100 nm, leading to a decrease in intensity, before dissociating, which is thought to correspond to vesicle scission (Figure 5D, left, and Supplementary Movie 1; Kaksonen et al., 2005). In the RC-RC mutant, Rvs167-GFP appeared and then disappeared, at the cell surface with no distinct internalization movement, maintaining maximal GFP intensity throughout (Figure 5D, right, and Supplementary Movie 2). The absence of internalization of Rvs167-GFP was seen in ∼37% of the patches in wild-type cells (n = 116) but increased dramatically to ∼91% in the RC-RC mutant (n = 135). An Rvs167-GFP internalization defect, similar to that seen in the RC-RC mutant, has been previously observed in conditions where vesicle scission is compromised (Kaksonen et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2007), suggesting that failure of Rvs167-GFP internalization may be closely associated with failure of membrane scission. We conclude that the internalization defect in the RC-RC mutant reflects a specific failure of membrane scission.

Aberrant patch movement can often lead to changes in total lifetime of the patch protein (Kaksonen et al., 2005). However, the failure of internalization did not significantly alter the total lifetime of Rvs167-RC-GFP in the RC-RC mutant compared with the wild type (12.1 ± 1.8 s in wild type, n = 30 and 13.2 ± 2.5 s in RC-RC, n = 30). A similar observation was reported for wild-type cells treated with latrunculin A, where Rvs167-GFP showed a normal lifetime with no internalization movement even when endocytosis was completely impaired (Kaksonen et al., 2005). These results show that Rvs167-GFP dissociation from actin patches is independent of unsuccessful endocytosis. Despite the unchanged lifetime of Rvs167-RC-GFP, the internalization defect can contribute to the apparent increase in the number of patches at a static time point (Figure 5C), as the RC-RC mutant displays intense, immobile patches at the membrane surface, which are more readily detected compared with the faint, mobile patches in wild-type cells.

The Rvs BAR Domain Mutants Interact Genetically with the Synaptojanin, INP52

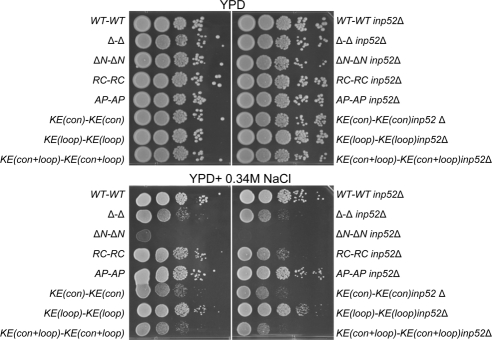

The absence of Rvs internalization has been reported previously for wild-type cells treated with the actin polymerization inhibitor, latrunculin A and in cells lacking synaptojanins (Inp51 and Inp52; Kaksonen et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2007). Synaptojanins are inositol-polyphosphate 5-phosphatases that have been suggested to function together with Rvs161 and Rvs167 to promote membrane scission during endocytosis (Liu et al., 2006, 2009; Sun et al., 2007). When the genes encoding synaptojanins, INP51, INP52, and INP53, are inactivated, phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate [PtdIns(4,5)P2] levels increase, blocking endocytosis (Stefan et al., 2002). One synaptojanin in particular, Inp52, localizes to cortical actin patches (Sun et al., 2007). To investigate the functional relationship between Rvs and synaptojanins, we examined synthetic genetic interaction between RVS and INP52. In rich medium, deletion of INP52 in rvs BAR domain mutants had no effect on fitness (Figure 6, top panel). However, in the presence of 0.34 M salt, when endocytosis becomes essential, we observed synthetic growth defects among the mutants defective in endocytosis (Δ-Δ inp52Δ, ΔN-ΔN inp52Δ, RC-RC inp52Δ, and KE(con)-KE(con) inp52Δ, KE(con+loop)-KE(con+loop) inp52Δ) but not in the other mutants (Figure 6, bottom). Among the mutants tested, RC-RC displayed the most significant genetic interaction, indicating that absence of INP52 is most deleterious to a mutant which can localize to the sites of endocytosis but fails to perform its function in membrane scission. These results provide the first genetic evidence supporting a shared function for the Rvs proteins and Inp52, possibly in the endocytosis process.

Figure 6.

Serial spot dilutions show synthetic genetic interaction between INP52 and rvs161 rvs167 BAR domain mutants under high-salt conditions. Triple mutants were serially diluted 20-fold and spotted onto YPD and YPD + 0.34 M NaCl, which were incubated for 2 d at 30°C.

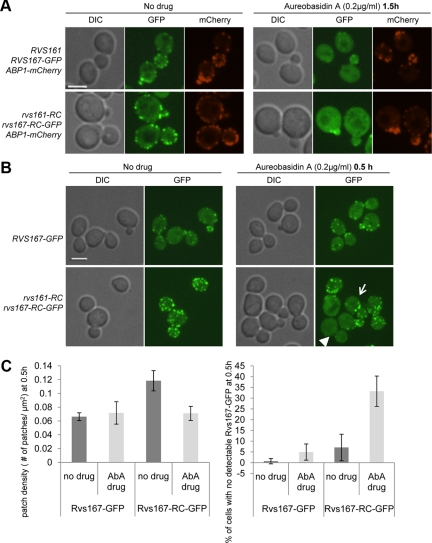

Complex Sphingolipids Are Needed for Rvs167 But Not for Abp1 Localization to Sites of Endocytosis

Like phospholipids and sterols, sphingolipids are major components of the membrane and play important roles in various cellular processes such as apoptosis, cell signaling, and endocytosis (for review see Souza and Pichler, 2007; Hannun and Obeid, 2008). Sphingolipids are required for endocytosis (Zanolari et al., 2000), and previous work has suggested their functional association with Rvs proteins (Desfarges et al., 1993; Balguerie et al., 2002; Germann et al., 2005; McCourt et al., 2009; Morgan et al., 2009). To further examine the functional relationship of Rvs proteins with sphingolipids, we asked whether changes in levels of complex sphingolipids affected either the fitness of BAR domain mutants or Rvs167-GFP localization. We used aureobasidin A (AbA) to specifically inhibit Aur1, an inositolphosphorylceramide (IPC) synthase, thus efficiently blocking synthesis of all complex sphingolipids (inositolphosphorylceramide (IPC), mannosyl-inositolphosphorylceramide (MIPC) and inositolphosphoryl-MIPC [M(IP)2C]; Nagiec et al., 1997; Dickson and Lester, 1999; Cerantola et al., 2009). AbA is known to disrupt actin cables and polarity of actin patches at 5 μg/ml (Endo et al., 1997), but how it affects actin patch proteins is unknown. At a sub-lethal concentration of AbA (0.1 μg/ml), all rvs BAR domain mutants exhibited higher sensitivity than wild type, with the most severely affected strain, ΔN-ΔN, failing to form colonies (Supplementary Figure 7A). With the exception of ΔN-ΔN, all of the BAR domain mutants, including the cell-fusion mutant AP-AP, were equally sensitive to AbA, a phenotypic profile distinct from that seen in our mating and endocytosis-related assays.

Next, we studied the effect of AbA on Rvs localization and found clear mislocalization of Rvs167-GFP (Figure 7A, top middle panel). Almost all of the wild-type Rvs167-GFP cortical patches disappeared after treatment with 0.2 μg/ml AbA (70% reduction in patch density, n ≥ 120) without any changes in Rvs167-GFP protein levels (Supplementary Figure 7B). In contrast, AbA did not alter localization of the actin-binding protein Abp1 and minimally affected its patch density (15% reduction, n ≥ 120), suggesting that the localization defect was largely specific to Rvs167 (Figure 7A, right panel).

Figure 7.

Rvs167-GFP localization is perturbed by aureobasidin A (AbA), an inhibitor of complex sphingolipid synthesis. (A) Localization of Rvs167-GFP and Abp1-mCherry in the absence (left) or in the presence of 0.2 μg/ml AbA was examined after 1.5 h of incubation by confocal microscopy in wild-type and RC-RC mutant cells. Single images were taken; scale bar, 4 μm. (B) RVS167-GFP and rvs161-RC rvs167-RC-GFP cells were treated with 0.2 μg/ml AbA for 0.5 h and imaged. Images show maximum intensity projections of multiple Z-series. Arrow indicates an example of a cell with a low number of GFP patches under AbA treatment. Arrowhead points to a cell where almost all patches have mislocalized. Scale bar, 4 μm. (C) Left, Rvs167-GFP patch density [number of patches/cell surface area (μm2)] in RVS167-GFP and rvs161-RC rvs167-RC-GFP cells after 0.5-h treatment with ± 0.2 μg/ml AbA. Right, quantification of Rvs167-GFP mislocalization in the presence of AbA show percentage of cells with no detectable Rvs167-GFP in the presence or absence of 0.2 μg/ml AbA at 0.5 h. n ≥ 100 cells, repeated three times.

The AbA effect on Rvs167 localization may be due to accumulation of the inhibited enzyme substrate, ceramide, or reduced levels of the enzyme product, complex sphingolipids. To distinguish between the two possibilities, we tested the effect of myriocin treatment, which blocks the first step of the sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway, resulting in reduced levels of all downstream byproducts, including ceramide and complex sphingolipids (Horn et al., 1992). If the Rvs167 localization defect is due to reduction in complex sphingolipids, but not due to accumulation of ceramides, myriocin treatment should also result in Rvs167 mislocalization. When an Rvs167-GFP strain was treated with myriocin, Rvs167-GFP was mislocalized in a manner similar to that seen in AbA-treated cells (data not shown), indicating that the localization phenotype is likely caused by a reduction of complex sphingolipids.

We next used AbA treatment to further explore the defect in the RC-RC mutant, which showed efficient localization to cortical patches but was defective in endocytosis. If Rvs167-RC-GFP had an altered interaction with the membrane, we might expect to see different localization changes in response to AbA. After 1.5 h of AbA treatment, Rvs167-RC-GFP displayed the same cytoplasmic mislocalization as wild-type Rvs167-GFP (Figure 7A, bottom panels). However, at an earlier time-point (0.5 h), when wild-type Rvs167-GFP localization was indistinguishable from that in untreated cells, the RC-RC mutant showed a clear localization defect in AbA with a number of cells showing either few patches (arrow) or no patches (arrowhead; Figure 7B, quantification shown in Figure 7C). We conclude that the RC-RC mutation decreases the Rvs interaction with some component of the membrane, thus increasing its sensitivity to further perturbation in membrane composition, such as complex sphingolipid depletion.

DISCUSSION

Amphiphysins play an important role in synaptic vesicle endocytosis in mammalian cells and are associated with cancer and neurological disorders such as Stiff-Man syndrome (De Camilli et al., 1993; Ge et al., 2000; Di Paolo et al., 2002). We undertook a structure-function analysis of the amphiphysin homologues Rvs161 and Rvs167 in yeast in an effort to elucidate BAR domain function. In our biochemical characterization of the yeast BAR domain heterodimer, we show that Rvs161-Rvs167, like its metazoan homodimer counterparts, binds and tubulates membranes in vitro. Because membrane deformation is energetically unfavorable, many BAR domains need to act in concert to create the tubular membrane structures seen in vitro. As a first step in characterizing this concerted activity, we show that the Rvs BAR domain interacts with another Rvs BAR domain in vivo, consistent with oligomerization of BAR domains at the sites of endocytosis. We then combined our biochemical analysis with genetic analysis of mutations targeting different parts of the BAR domain. In vivo analysis of the rvs BAR domain mutants suggests that Rvs proteins are initially recruited to sites of endocytosis through their curvature-sensing and membrane-binding ability in a manner dependent on complex sphingolipids.

Membrane Binding and Bending Properties of Rvs BAR Domains In Vitro

We found that full-length Rvs161-Rvs167, purified from a heterologous system, binds to liposomes in a curvature-independent manner and induces tubular structures in liposomes in vitro (Figure 1, B and C). Curvature-independent membrane binding is seen with other amphiphysins and N-BAR proteins (Peter et al., 2004) and suggests that Rvs161-Rvs167 is able to actively promote curvature. Although we were able to detect Rvs binding to standard Folch liposomes in a cosedimentation assay, tubulation was extremely inefficient using the Folch liposomes. However, when incubated with synthetic liposomes with a composition similar to the yeast plasma membrane, Rvs161-Rvs167 was able to induce tubular structures in the membrane, suggesting that membrane composition is important for Rvs tubulation activity. Relative to other N-BAR domain proteins, DmAmph and endophilin, which can generate tubules in vitro of ∼46 and 35–50 nm, respectively (Peter et al., 2004; Gallop et al., 2006), Rvs161-Rvs167 induced tubular structures with a diameter of ∼18–20 nm in ∼15% of liposomes (Figure 1C), which is fairly narrow. Likewise, yeast endocytic tubular invaginations in vivo have been detected by electron micrographs and range from 35 to 50 nm in diameter (Idrissi et al., 2008). The narrow tubule diameter induced by Rvs161-Rvs167 in vitro may reflect modulation of the BAR domain membrane-bending activity in the context of the entire endocytic machinery in vivo.

Membrane Composition Affects Rvs Function In Vivo

Two plasma membrane components, PI(4,5)P2 and sphingolipids, play active roles in the endocytosis process (Souza and Pichler, 2007). Sphingolipid-cholesterol rafts are preferred sites for PI(4,5)P2–mediated membrane-linked actin polymerization in mammalian cells (Rozelle et al., 2000). Our work suggests that both PI(4,5)P2 and sphingolipids are important for the role of Rvs in the endocytosis process. First, local levels of PI(4,5)P2 seem to affect Rvs function in scission of the endocytic vesicle: a previous study showed that in inp51Δ inp52Δ cells, abnormal deep membrane invaginations form and Rvs167-GFP fails to internalize, suggesting a failure of vesicle scission (Sun et al., 2007). Consistent with this, we observed a synthetic slow-growth phenotype in inp52Δ endocytosis-defective Rvs BAR-domain-mutant strains in salt-containing medium (Figure 6), suggesting a shared role in endocytosis. Second, complex sphingolipids are required for proper localization of Rvs167: inhibition of synthesis of complex sphingolipids by AbA disrupts localization of wild-type Rvs167-GFP and of Rvs167-RC-GFP to an even greater extent (Figure 7). Furthermore, increasing levels of the complex sphingolipids IPC or MIPC by deleting the genes encoding their modifying enzymes, SUR1 or IPT1, respectively (Beeler et al., 1997; Dickson et al., 1997), suppresses a loss of Rvs function as measured by restored growth under salt-containing media (Desfarges et al., 1993; Balguerie et al., 2002). Thus sphingolipids, as a major component of the plasma membrane, affect both Rvs localization and an endocytosis-related function in the absence of Rvs. In conclusion, our results suggest that the proper levels of complex sphingolipids and PI(4,5)P2 in the membrane are important for Rvs function.

Biological Consequences of Modifications in the N-BAR Domain

We made changes in both RVS161 and RVS167 at their endogenous loci and used a panel of Rvs-specific biological assays to dissect BAR domain function. Below, we discuss our findings about the in vivo functions of the Rvs BAR domains as revealed by phenotypic analysis of BAR domain mutants (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of rvs BAR domain mutant phenotypes

| rvs161 rvs167genotype | Cell fusion (mating) | Growth on salta | LY uptakeb | Sla1-GFP internalizationc | Localization to coritcal actin patches (Rvs167-GFP)d | Synthetic growth defect in inp52Δ background | AbA sensitivitye |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT WT | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Δ Δ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ΔNΔN | − | −f | − | ± | − | − | −f |

| RC RC | + | − | ± | − | + | − | − |

| AP AP | − | + | + | ± | + | + | − |

| KE(con) KE(con) | ± | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KE(loop) KE(loop) | ± | − | ± | − | ± | + | − |

| KE(con+loop) KE(con+loop) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

a Growth sensitivity on 0.7 M NaCl-containing medium was used to assess growth. +, colonies form in three or more serially diluted spots; −, colonies form in ≤2 spots.

b +, more than 60% of cells show LY-stained vacuole; ±, between 30 and 60% of cells show LY-stained vacuole; −, <30% of cells show LY-stained vacuole.

c +, <5% of Sla1-GFP patches fail to internalize and show retraction; ±, between 5 and 13% of the Sla1-GFP patches fail to internalize and show retraction; −, between 13 and 22% of the Sla1-GFP patches fail to internalize and show retraction.

d ±, Rvs167-GFP patch density is reduced; −, no punctate RVS167-GFP patches detected.

e Growth in 0.1 μg/ml AureobasidinA (AbA)-containing media. +, colonies form in three or more serially diluted spots; −, colonies form in ≤2 spots.

f ΔN ΔN phenotype is more severe than Δ Δ.

Role of Basic Residues.

In amphiphysin, changing pairs of basic residues to acidic residues reduces binding to liposomes and tubulation in vitro (Peter et al., 2004), but the in vivo consequences of these changes in the context of the endogenous genes are unknown. We found that both sets of KE substitutions (in the predicted concave surface and in the loop) in the Rvs proteins led to a reduction in mating (Supplementary Figure 2), in growth on salt-containing medium and in fluid-phase endocytosis, an increase in the Sla1-GFP retraction and a failure to properly localize to sites of endocytosis (Figures 4 and 5A). We attribute these defects to inefficient binding of the KE mutants to membranes.

Role of the N-Terminal Amphipathic Helix.

Truncation of the N-terminal amphipathic helix of Drosophila amphiphysin or mammalian amphiphysin1 reduces liposome binding, but these proteins still tubulate liposomes at high concentrations in vitro (Peter et al., 2004). In contrast, we discovered that deletion of the N-terminal amphipathic helices of Rvs161 and Rvs167 had dramatic effects in vivo: the ΔN-ΔN mutant was more defective than the rvs161Δ rvs167Δ mutant in mating, growth on salt and AbA-containing media, and was severely defective in LY uptake. In addition, we could not detect Rvs167-ΔN-GFP localization to cortical patches in the ΔN-ΔN mutant background, indicating that the N-terminal amphipathic helix is required for proper localization to the sites of endocytosis. Despite the apparent absence of cortical localization and a severe defect in LY uptake, ΔN-ΔN displayed a moderate defect in Sla1-GFP internalization. This may be due to the presence of some Rvs167-ΔN-GFP at sites of endocytosis, but at a level below the limit of microscopic detection. Also, the specificity of the two assays is quite different: Sla1-GFP retraction indicates a specific failure in the vesicle internalization step of endocytosis, whereas LY uptake is an end-point assay that measures the cumulative defects in endocytosis and vesicle trafficking. It is possible that ΔN-ΔN has defects in additional steps after vesicle scission, for example, in stabilizing membrane curvature at the early or late endosome. Our finding that ΔN-ΔN has more severe defects in LY uptake than in Sla1 internalization and that RC-RC has less severe defects in LY uptake than in Sla1 internalization suggests that these mutants show separation of function. In support of a role for Rvs in later steps of endocytosis, both RVS161 and RVS167, but few other early endocytic genes, have synthetic lethal interactions with VPS21 and VPS8, two genes encoding proteins involved in early to late endosome fusion (Singer-Kruger and Ferro-Novick, 1997; Germann et al., 2005; Friesen et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2007; Costanzo et al., 2010). In addition, RVS161 has a genetic interaction with VPS20 (Germann et al., 2005) and RVS167 with DID4 (Costanzo et al., 2010); both Vps20 and Did4 are components of the ESCRT-III complex, required for transport of proteins into multivesicular bodies for targeting to the vacuole. This synthetic lethality with vesicle trafficking genes suggests that Rvs may have an additional role in late endosomal trafficking, after the scission step.

Interestingly, the ΔN-ΔN mutant had a gain-of-function phenotype in some of our in vivo assays (as shown by growth defects more severe than Δ-Δ), suggesting that the N-terminal helix may play a regulatory role in Rvs function. This idea is supported by a quantitative comparison of membrane-binding activities of different motifs in various N-BAR domains showing that the N-terminal amphipathic helix, rather than the crescent shape of the BAR domain, is responsible for sensing membrane curvature (Bhatia et al., 2009). Consistent with a regulatory role for the N-terminal helix, several residues in the N-terminal helices of Rvs161 and Rvs167 have been identified as phosphorylation sites using high-throughput mass spectrometry (Gruhler et al., 2005; Chi et al., 2007); these modifications could affect the interaction of the helix with the membrane. We suggest that the N-terminal helix may regulate Rvs N-BAR domain function, possibly its membrane curvature-sensing activity, and that loss of this regulation in the absence of N-terminal helix could lead to inappropriate activity of Rvs. As the severe defect of the ΔN-ΔN mutant is complemented by a copy of wild-type Rvs161-Rvs167 (data not shown), we speculate that multimerization with wild-type protein is sufficient to restore proper regulation.

Role of Arginine 35 and 37.

Substitution of Arg 35 by cysteine in Rvs161 led to defects in LY uptake but not in mating (Brizzio et al., 1998). In our study, a strain carrying an Arg35 substitution in Rvs161 and an analogous change in Rvs167 (RC-RC) was partially defective in fluid-phase endocytosis but had a severe defect in Sla1-GFP internalization. We suggest that the role for Rvs in the vesicle scission step is separable from its proposed role in late endosomal trafficking. In contrast to the ΔN-ΔN mutant, the RC-RC mutant has a very specific defect in membrane scission, but is only moderately affected beyond the scission step. Unlike other mutants with defects in endocytosis, the RC-RC mutant protein localized efficiently to cortical actin patches and showed higher patch density than wild-type. Using live-cell imaging, we found that although wild-type Rvs167-GFP rapidly internalizes during endocytosis, Rvs167-RC-GFP remains at the cell surface and fails to internalize before dissociation, contributing to an increase in patch density. Because RC-GFP fails to internalize completely, unlike Sla1-GFP which still internalizes but is retracted back to the cortex in the RC-RC mutant, we hypothesize that RC-GFP fails to be tethered to the pulling force (actin polymerization). This may reflect spatial removal from the invaginating vesicle neck region or a failure to interact with a protein component mediating a physical interaction with actin. A similar failure of Rvs167-GFP internalization is also seen in wild-type cells treated with latrunculin A and in inp51Δ inp52Δ mutants, which are defective in vesicle scission (Kaksonen et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2007), supporting the idea that failure of Rvs167-GFP internalization is associated with failure of membrane scission. Consistent with our finding that Rvs167-GFP internalization is defective in both inp51Δ inp52Δ and RC-RC mutants, we saw a significant genetic interaction between rvs161-RC rvs167-RC and inp52Δ. In the mechanochemical model, Rvs binding to the membrane is required to generate lipid phase separation for synaptojanins to hydrolyze the unprotected PI(4,5)P2 species at the interface and to trigger a positive feedback loop. Because the RC-RC mutant is uniquely able to bind to the membrane and localize to sites of endocytosis, this positive feedback loop is probably moderately affected. But when synaptojanin function is disrupted in the RC-RC background, this positive feedback loop may now be completely abolished and the lipid phase boundary can no longer be generated for membrane scission. Our results support the mechanochemical model in which Rvs proteins and Inp52 both contribute in a positive feedback loop to generate a large interfacial force for vesicle scission (Liu et al., 2006, 2009).

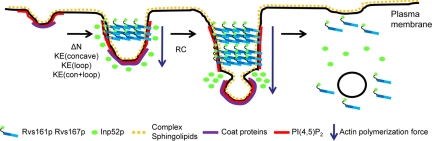

A Model for the Role of Rvs-mediated Scission in Endocytosis

Our genetic and biochemical analysis of BAR domain mutants leads us to propose a model describing Rvs activity during the endocytosis process (Figure 8). First, at selected endocytic sites, membrane curvature is initiated by binding of endocytic coat proteins and actin polymerization. Next, Rvs161-Rvs167 binds to the curved membranes. Consistent with other in vitro findings (Bhatia et al., 2009) and the more severe defects seen in ΔN-ΔN than Δ-Δ, we suggest that Rvs requires its N-terminal amphipathic helices to sense the specific curved membranes where endocytosis is proceeding. Rvs then promotes further bending of the membrane by forming helical structures around the vesicle neck in a manner similar to related F-BAR proteins (Frost et al., 2008). This binding is directly or indirectly dependent on complex sphingolipids, because Rvs167-GFP fails to localize properly in the presence of AbA, an inhibitor of complex sphingolipid synthesis. Our in vivo analysis of Rvs167-GFP localization suggests that positive charges in the concave and loop region of the BAR domain facilitate stable electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged membrane, as seen in Drosophila amphiphysin in vitro (Peter et al., 2004). Finally, Rvs161-Rvs167 and synaptojanin function together to promote vesicle scission. As proposed by Liu et al., 2009, scission is initiated when Inp52 hydrolyzes PI(4,5)P2 throughout the vesicle neck except where Rvs binding protects the underlying PI(4,5)P2. This differential PI(4,5)P2-hydrolysis leads to a well-defined lipid-phase boundary between the bud region and the rest of the tubulating vesicle neck, generating an interfacial force. This force induces higher curvature between the lipid phases, which triggers a mechanochemical feedback loop leading to sufficient interfacial force for vesicle scission to occur (Liu et al., 2006, 2009). The latter stage is defective in the RC-RC mutant, probably because it fails to generate an adequate lipid phase boundary.

Figure 8.

Model showing steps required for Rvs-mediated membrane scission during the endocytosis process with rvs161 rvs167 BAR domain mutants overlaid on the steps for which they are defective. The model is partially adapted from Liu et al., 2009. Pulling forces generated by actin polymerization impinge on the selected endocytic site and invaginate the membrane. BAR domain proteins form helical structures at the neck of the invaginating plasma membrane. The N-terminal amphipathic helix and positive charges on the surface (concave and loop region) of the Rvs BAR domain are required for this step. At the plasma membrane, complex sphingolipids are needed for Rvs167 localization to the endocytic sites. Next, Rvs161-Rvs167 and synaptojanin function to promote scission of the vesicle, by Rvs protecting the PI(4,5)P2 in the vesicle neck and Inp52 hydrolyzing PI(4,5)P2 to generate a lipid phase boundary. This reaction leads to a mechanochemical feedback loop, which creates a large interfacial force, driving membrane scission (Liu et al., 2006, 2009). The RC RC BAR domain mutant is specifically defective at this stage.

In summary, our evidence suggests that the Rvs heterodimer is recruited to sites of endocytosis through its curvature-sensing and membrane-binding ability. We have shown functional relationships between Rvs and key components of the membrane involved in endocytosis: complex sphingolipids and PI(4,5)P2. Our in vivo characterization of Rvs proteins in S. cerevisiae confirms that BAR domains function in membrane scission during the endocytosis process and provides evidence supporting their unique involvement with membrane components.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Riezman (University of Geneva) for α-Rvs161 antibody and W.K. Huh (Seoul University) for the BiFC plasmids. We also thank D. G. Drubin for helpful discussions. This work was supported by Grant 0161123 from the National Cancer Institute of Canada (now the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute) with funds from the Canadian Cancer Society. J.-Y.Y. was partially supported by a Delta Kappa World Fellowship and CFK is a long-term EMBO Fellow. WMH was partially supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC), and T.K. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM R01 42759 and GM R01 50399. D.F.C. is funded by Canadian Institute of Health Research to F.S. (MOP-36399).

Abbreviations used:

- AbA

aureobasidinA

- BAR

Bin Amphiphysin Rvs

- BiFC

bimolecular fluorescence complementation

- LY

Lucifer yellow

- PI(4,5)P2

phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0181) on July 7, 2010.

REFERENCES

- Balguerie A., Bagnat M., Bonneu M., Aigle M., Breton A. M. Rvs161p and sphingolipids are required for actin repolarization following salt stress. Eukaryot. Cell. 2002;1:1021–1031. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.6.1021-1031.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balguerie A., Sivadon P., Bonneu M., Aigle M. Rvs167p, the budding yeast homolog of amphiphysin, colocalizes with actin patches. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 15):2529–2537. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.15.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer F., Urdaci M., Aigle M., Crouzet M. Alteration of a yeast SH3 protein leads to conditional viability with defects in cytoskeletal and budding patterns. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:5070–5084. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler T. J., Fu D., Rivera J., Monaghan E., Gable K., Dunn T. M. SUR1 (CSG1/BCL21), a gene necessary for growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the presence of high Ca2+ concentrations at 37°C, is required for mannosylation of inositolphosphorylceramide. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1997;255:570–579. doi: 10.1007/s004380050530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V. K., Madsen K. L., Bolinger P. Y., Kunding A., Hedegard P., Gether U., Stamou D. Amphipathic motifs in BAR domains are essential for membrane curvature sensing. EMBO J. 2009;28:3303–3314. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon E., Recordon-Navarro P., Durrens P., Iwase M., Toh E. A., Aigle M. A network of proteins around Rvs167p and Rvs161p, two proteins related to the yeast actin cytoskeleton. Yeast. 2000;16:1229–1241. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000930)16:13<1229::AID-YEA618>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizzio V., Gammie A. E., Rose M. D. Rvs161p interacts with Fus2p to promote cell fusion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:567–584. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerantola V., Guillas I., Roubaty C., Vionnet C., Uldry D., Knudsen J., Conzelmann A. Aureobasidin A arrests growth of yeast cells through both ceramide intoxication and deprivation of essential inositolphosphorylceramides. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;71:1523–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi A., Huttenhower C., Geer L. Y., Coon J. J., Syka J. E., Bai D. L., Shabanowitz J., Burke D. J., Troyanskaya O. G., Hunt D. F. Analysis of phosphorylation sites on proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae by electron transfer dissociation (ETD) mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2193–2198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607084104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. R., et al. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature. 2007;446:806–810. doi: 10.1038/nature05649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwill K., Field D., Moore L., Friesen J., Andrews B. In vivo analysis of the domains of yeast Rvs167p suggests Rvs167p function is mediated through multiple protein interactions. Genetics. 1999;152:881–893. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M., et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J. C., Legg J. A., Machesky L. M. Bar domain proteins: a role in tubulation, scission and actin assembly in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Camilli P., Thomas A., Cofiell R., Folli F., Lichte B., Piccolo G., Meinck H. M., Austoni M., Fassetta G., Bottazzo G. The synaptic vesicle-associated protein amphiphysin is the 128-kD autoantigen of Stiff-Man syndrome with breast cancer. J. Exp. Med. 1993;178:2219–2223. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desfarges L., Durrens P., Juguelin H., Cassagne C., Bonneu M., Aigle M. Yeast mutants affected in viability upon starvation have a modified phospholipid composition. Yeast. 1993;9:267–277. doi: 10.1002/yea.320090306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G., Sankaranarayanan S., Wenk M. R., Daniell L., Perucco E., Caldarone B. J., Flavell R., Picciotto M. R., Ryan T. A., Cremona O., De Camilli P. Decreased synaptic vesicle recycling efficiency and cognitive deficits in amphiphysin 1 knockout mice. Neuron. 2002;33:789–804. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson R. C., Lester R. L. Metabolism and selected functions of sphingolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1438:305–321. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson R. C., Nagiec E. E., Wells G. B., Nagiec M. M., Lester R. L. Synthesis of mannose-(inositol-P)2-ceramide, the major sphingolipid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, requires the IPT1 (YDR072c) gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:29620–29625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29620. ¤¤¤. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M., Takesako K., Kato I., Yamaguchi H. Fungicidal action of aureobasidin A, a cyclic depsipeptide antifungal antibiotic, against Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:672–676. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsad K., Ringstad N., Takei K., Floyd S. R., Rose K., De Camilli P. Generation of high curvature membranes mediated by direct endophilin bilayer interactions. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen H., Colwill K., Robertson K., Schub O., Andrews B. Interaction of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cortical actin patch protein Rvs167p with proteins involved in ER to Golgi vesicle trafficking. Genetics. 2005;170:555–568. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.040063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen H., Humphries C., Ho Y., Schub O., Colwill K., Andrews B. Characterization of the yeast amphiphysins Rvs161p and Rvs167p reveals roles for the Rvs heterodimer in vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:1306–1321. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost A., Perera R., Roux A., Spasov K., Destaing O., Egelman E. H., De Camilli P., Unger V. M. Structural basis of membrane invagination by F-BAR domains. Cell. 2008;132:807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallop J. L., Jao C. C., Kent H. M., Butler P. J., Evans P. R., Langen R., McMahon H. T. Mechanism of endophilin N-BAR domain-mediated membrane curvature. EMBO J. 2006;25:2898–2910. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge K., Duhadaway J., Sakamuro D., Wechsler-Reya R., Reynolds C., Prendergast G. C. Losses of the tumor suppressor BIN1 in breast carcinoma are frequent and reflect deficits in programmed cell death capacity. Int. J. Cancer. 2000;85:376–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germann M., Swain E., Bergman L., Nickels J. T., Jr. Characterizing the sphingolipid signaling pathway that remediates defects associated with loss of the yeast amphiphysin-like orthologs, Rvs161p and Rvs167p. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:4270–4278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A. L., McCusker J. H. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1999;15:1541–1553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1541::AID-YEA476>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruhler A., Olsen J. V., Mohammed S., Mortensen P., Faergeman N. J., Mann M., Jensen O. N. Quantitative phosphoproteomics applied to the yeast pheromone signaling pathway. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2005;4:310–327. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400219-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie C., Fink G. R. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. Methods in Enzymology. 1991;Vol. 169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]