Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) has a dual role in carcinogenesis, acting as a growth inhibitor in early tumor stages and a promoter of cell proliferation in advanced diseases. Although this cellular phenomenon is well established, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain elusive. Here, we report that sequential induction of NFAT and c-Myc transcription factors is sufficient and required for the TGF-β switch from a cell cycle inhibitor to a growth promoter pathway in cancer cells. Mechanistically, TGF-β induces in a calcineurin-dependent manner the expression and activation of NFAT factors, which then translocate into the nucleus to promote c-Myc expression. In response to TGF-β, activated NFAT factors bind to and displace Smad3 repressor complexes from the previously identified TGF-β inhibitory element (TIE) to transactivate the c-Myc promoter. c-Myc in turn stimulates cell cycle progression and growth through up-regulation of D-type cyclins. Most importantly, NFAT knockdown not only prevents c-Myc activation and cell proliferation, but also partially restores TGF-β-induced cell cycle arrest and growth suppression. Taken together, this study provides the first evidence for a Smad-independent master regulatory pathway in TGF-β-promoted cell growth that is defined by sequential transcriptional activation of NFAT and c-Myc factors.

Keywords: Myc, NFAT Transcription Factor, Signal Transduction, SMAD Transcription Factor, Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF-β), Cell Proliferation

Introduction

The biological functions of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)4 are highly complex and ambivalent during development as well as in neoplastic transformation. In normal development and at early stages of tumorigenesis, TGF-β blocks proliferation through induction of a cell cycle arrest at late G1 (1). Two distinct mechanisms play a pivotal role in TGF-β-mediated growth arrest: the initial repression of the basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper (bHLH-LZ) transcription factor c-Myc and the subsequent induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p15Ink4b and p21Cip1 (2, 3). c-Myc is a ubiquitous promoter of cell proliferation that binds to the initiator element of the p15Ink4b promoter and together with the zinc-finger protein Miz1 suppresses p15Ink4b expression and function in proliferating cells (4). Down-regulation of c-Myc constitutes the first essential step in TGF-β-induced growth arrest resulting in two major effects: to deprive the cell of growth-promoting functions and to facilitate the induction of the Cdk inhibitors p15Ink4b and p21Cip1 (5, 6). These growth-suppressing activities of TGF-β depend on the integrity of the Smad signaling pathway and hence alterations of the cascade often result in inadequate growth inhibition in response to the growth factor (7–9). In the basal state, Smad transcription factors are predominantly localized in the cytoplasm (9). Upon ligand-induced receptor activation, Smad2 and 3 are recruited to, and phosphorylated by the type-I receptor, allowing them to form complexes with the common mediator Smad4, and translocate into the nucleus, where they can regulate, together with other partner proteins, the transcription of cell cycle inhibitors (10). Cells escape from TGF-β-mediated growth suppression due to alterations of the Smad signaling pathway. For instance, mutational inactivation of the Smad4 tumor suppressor gene is a common event in human cancers and is closely associated with reduced growth suppression by TGF-β (11, 12). Similarly, loss of growth inhibition by TGF-β can also be the result of functional deregulation of the Smad pathway, e.g. following crosstalk interactions with the proliferative Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK cascade (13, 14). Importantly, neither mutational nor functional alterations of the Smad pathway cause a complete loss of TGF-β responsiveness. In fact, TGF-β under these circumstances can promote cell cycle progression (15). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this functional switch of TGF-β remain unknown.

Here, we show that NFAT transcription factors are mediators of this TGF-β switch in cancer cells. TGF-β exerts its proliferative function in cancer cells through transcriptional induction of the c-Myc oncogene, resulting in enhanced levels of D-type cyclins and their kinase partners. Intriguingly, c-Myc activation requires prior calcineurin dependent induction and activation of NFAT transcription factors. Upon TGF-β-induced expression, NFAT factors accumulate in the nucleus and displace a Smad3 repressor complex from the TIE of the proximal promoter to stimulate c-Myc transcription. Knockdown of NFAT proteins blocks TGF-β induction of c-Myc expression and partially restores TGF-β induced growth suppression in cancer cells. Together, these results identified a novel Smad-independent regulatory mechanism mediating the TGF-β switch to a proliferative pathway involving a defined interplay between NFAT and c-Myc transcription factors. Thus, these findings contribute to better understand the complex network of molecular events underlying the TGF-β function in cancer cells and thus could serve as foundation for the development of novel approaches for cancer therapy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Transfection Protocol

Panc-1 (ATCC, CRL-1469), PaTu8988t (DSMZ, ACC 162), SW-480 (ATCC, CCL-228), HT-29 (ATCC, HTB-38), and HaCaT (CLS 300493) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Expression and reporter promoter plasmids were transfected at 70% cell confluence using TransFast (Promega, Madison, WI). Short interfering RNA (siRNA) was transfected using TransmessengerTM reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and cells were treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β (PromoCell GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) and harvested at indicated time points.

Plasmid Constructs

The full-length human NFATc1 and NFATc2 expression constructs were provided by Dr. A. Rao (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). The c-Myc expression construct was generated by insertion of a PCR-amplified wt c-Myc into the pBIG2i vector using KpnI and SpeI restriction sites. The wt c-Myc reporter construct (−2446 to +334) and its deletion constructs were kindly gifted by Joan Massagué (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). The mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) SMAD3 WT and null were a gift from John R. Hawse (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). To generate the indicated single point mutations of the wt TIE element, we used the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions and a recently described wt TIE construct (−109 to ATG of the c-Myc promoter) (2). Mutagenesis primers were as followed: KLF 5′-CTCAGAGGCTTTTCGGGAAAAAGAACGGAGGGAG-3′, CORE 5′-CTCAGAGGCAATTCGGGAAAAAGAACGGAGGGAG-3′, SMAD 5′-CTCAGATTAAAGGCGGGAAAAAGAACGGAGGGAG-3′, E2F 5′-CTCAGAGGCTTCTTTGGAAAAAGAACGGAGGGAG-3′, SMAD/KLF/E2F 5′-CTCAGATTAAACTTTGGAAAAAGAACGGAGGGAG-3′, NFAT 5′-CTCAGAGGCTTGGCGGGCCCAAGAACGGAGGGAG-3′ and its congruent complementary strands. All constructs were inserted into a pGL3 vector (Promega) using KpnI and SpeI restriction sites.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA)

siRNA was transfected using the TransmessengerTM reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The specific siRNAs were purchased from Ambion Applied Biosystems (Austin, TX) with the following sequences: NFATc1 no. 2 5′-GGACUCCAAGGUCAUUUUCTT-3′, NFATc2 no. 3 5′-CCAUUAAACAGGAGCAGAATT-3′. Smad3 no. 1 5′-GCAUCCGCUGUUCCAGUGGUTT-3′. As a negative control, the silencer negative-control from Ambion was used.

Reporter Gene Assays

For luciferase reporter gene assays, 106 cells were seeded into 12-well tissue culture dishes and transfected after 24 h with the indicated constructs. Treatment with TGF-β (10 ng/μl) (PromoCell GmbH) was maintained 24 h after transfection for the indicated time periods. Luciferase assays were performed with a Lumat LB 9501 luminometer (Berthold Technologies) and the Dual-Luciferase®-Reporter Assay system (Promega). Firefly luciferase values were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity and were either expressed as relative luciferase activity (RLA) or as mean fold induction with respect to empty vector control. Mean values are displayed with standard deviations.

Protein Analysis

For Western blotting, 20–30 μg of homogenized lysates were analyzed on a 10–15% SDS-PAGE as described before (17). Polyvinylidene difluoride Immobilon-P membranes from Millipore (Billerica, MA) were incubated with antibodies against pSmad3, cyclin D1, CdK4, CdK6 (all from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA), c-Myc, NFATc2 (from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Smad 2/3 (from BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), Smad3 (from Abcam, Cambridge, UK), NFATc1 (from Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and β-actin (from Sigma-Aldrich).

Secondary, peroxidase-conjugated antibodies against mouse-AB or rabbit-AB were obtained from Cell Signaling. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce).

Subcellular Fragmentation

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were performed as described earlier (17). Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and collected by centrifugation at 1500 × g at 4 °C. Lysates were resuspended in buffer A (10 mm Hepes pH 7.9, 10 mm KCl; 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, proteinase inhibitors) for 15 min and subsequently centrifuged for 20 min at 3500 × g. Supernatants were transferred into new cups and centrifuged at 10000 × g for 30 min. Pellets were resuspended in buffer C (20 mm Hepes pH 7.9, 0.4 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, proteinase inhibitors) and incubated on ice. A centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min was performed to separate nuclear proteins from cellular debris. The resulting nuclear protein extracts were analyzed on a 10–15% SDS-PAGE.

Proliferation Assay

Panc-1, PaTu8988t, SW-480, HT-29, MEF-Smad3-wt, MEF-Smad3−/−, or HaCaT cells were seeded in 12-well plates and cultured in medium containing 10% fetal calf serum until attachment. After attachment, cells were starved for 24 h in serum-free medium and either transfected with siRNA or treated with 10 ng/μl TGF-β for indicated time periods. [3H]Thymidine (0.5mCi/well) was added during the last 6 h of incubation. Incorporated [3H]thymidine was quantified as described previously (17). For statistical analysis, Student's t test was used, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Flow Cytometry

Cell cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry. Cells were treated with 10 ng/μl TGF-β for 18, 24, and 48 h, then trypsinized, washed with PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with 20 μg/ml RNase, DNase-free water with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide for 3 h at room temperature under light protection. The DNA content of 106 cells was analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACS Calibur flow cytometer (San Jose, CA). The fractions of cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases were calculated using Cell Quest software from Becton Dickinson (Topsham, ME).

Calcineurin Activity Assay

Cellular calcineurin phosphatase activity was measured with the Biomol GreenTM Cellular Calcineurin Assay Kit Plus according to the manufacturer's instructions (Enzo Life Sciences GmbH, Lörrach, Germany). Cells were left untreated or treated with 10 ng/μl TGF-β for 6, 18, 24, and 48 h before harvesting. Mean values are displayed ± standard deviations.

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using random primers and the Superscript first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The qRT-PCR was performed using a 7500 Fast-Real-Time-PCR-System from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, MA). Specific primer pairs were designed with the PrimerExpresss 3.0 (Applied Biosystems, Wellesley, MA) as followed human NFATc1: forward 5′-GTCCCACCACCGAGCCCACTACG-3′; reverse 5′-ACCATCTTCTTCCCGCCCACGAC-3′; NFATc2: forward 5′-GTTCCTACCCCACAGTCATTCAG-3′; reverse 5′-CCCGCAGGTAATACTTCCTTTTG-3′; XS-13 forward 5′-GTCGGAGGAGTCGGACGAG-3′; reverse 5′-GCCTTTATTTCCTTGTTTTGCAAA-3′; c-Myc: forward 5′-GCTCCTGGCAAAAGGTCAGA-3′; reverse 5′-CAGTGGGCTGTGAGGAGGTT-3′.

DNA Pulldown Assays

Cells were treated with 10 ng/μl TGF-β for indicated time periods. In total, 250 μg of nuclear protein per sample were incubated for 3 h with 1 μg of biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the NFAT binding sequence of the wild-type TIE element (TIE-wt, −92 to −63 relative to the c-Myc P2 transcription start site; 5′-TTCTCAGAGGCTTGGCGGGAAAAAGAACGG-3′ and its complementary strand) or the mutant TIE sequence with disruption of the NFAT site (TIE-NFAT-mut; 5′-TTCTCAGAGGCTTGGCGGGCCCAAGAACGG-3′ and its complementary strand). DNA-protein complexes were collected by precipitation with streptavidin-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h, washed twice with lysis buffer including proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors, and subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Analysis (ChIP)

The ChIP was performed in Panc-1 and 8988t cells treated with 10 ng/μl TGF-β for the indicated time periods. Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10min at 37 °C, harvested in SDS lysis buffer (Upstate Biotechnology), and DNA was shredded to fragments of 500 bp by sonication. Antibodies against NFATc1 or Smad3 were added to each aliquot of pre-cleared chromatin and incubated overnight. Protein G-agarose beads were added and incubated for 1.5 h at 4 °C. After reversing the cross-links, DNA was isolated and used for PCR reactions. Specific primer pairs were designed with the PrimerExpresss 3.0 (Applied Biosystems) as followed: 5′-GAGGGATCGCGCTGAGTAT′-3 and 5′-TCTAACTCGCTGTAGTAATTCCAGC-3′ for quantitative PCR amplifying the TIE element.

RESULTS

TGF-β-induced G1/S Phase Progression in Cancer Cells Requires an Intact c-Myc Activity

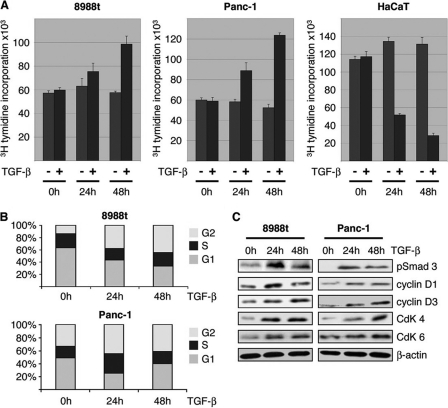

We initially tested the effect of TGF-β on cancer cell proliferation using a panel of cells with (PaTu8988t, SW-480, and HT-29) and without (Panc-1 and HaCaT) inactivating mutations of Smad4 (14, 17–18). For this purpose, cells were serum-starved overnight and then stimulated with TGF-β up to 48 h. Cell proliferation was assessed by incorporation of [3H]thymidine as described previously (16). TGF-β stimulation caused a significant increase in cell proliferation in Panc-1, PaTu8988t, SW-480, and HT-29 cell lines (Fig. 1A and data not shown). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the growth promoting effect of TGF-β in these cells was resulting from increased cell cycle progression, as evidenced by the shift of cells from G1 to S and G2 phases (Fig. 1B). Moreover, cell cycle stimulation in growth promoted cells was reflected by increased expression of D-type cyclins (cyclin D1 and D3) and their corresponding kinase partners CDK4 and CDK6 (Fig. 1C). As a control cell line, we used HaCaT keratinocytes that are sufficiently growth inhibited by TGF-β (Fig. 1A) (19).

FIGURE 1.

TGF-β-promoted cell cycle propagation and proliferation. A, influence of TGF-β on cell proliferation was assessed by incorporation of [3H]thymidine into Panc-1 and PaTu8988t cells after incubation in medium with 10 ng/μl TGF-β or without TGF-β for 24 and 48 h. Data are representative of triplicate experiments and are displayed as bars ± S.D. B, flow cytometry analysis was performed after propidium iodide (PI) staining in response to 10 ng/μl TGF-β treatment for 24 and 48 h. Cell cycle stages are illustrated in different colors: G2, S, and G1. Bars indicate mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, Western blot analysis to examine the effect of TGF-β on the expression of cell cycle regulatory genes in growth promoted cell lines. Panc-1 and PaTU8988t cells were left untreated or treated with TGF-β as indicated. Total cell lysates were then analyzed for expression of phosphorylated Smad3, D-type cyclins and their kinase partners (CdKs). Protein loading was controlled using anti-β-actin antibodies.

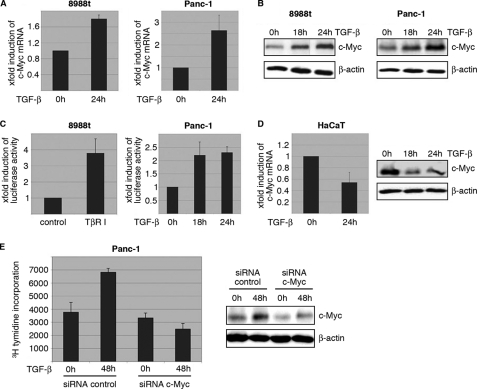

Further characterization of this cellular phenomenon revealed that TGF-β growth stimulation is strictly dependent on c-Myc induction in cancer cells. TGF-β up-regulates c-Myc expression on both mRNA and protein levels in growth promoted cancer cells (Fig. 2, A and B), and this induction was caused by differential promoter modulation (Fig. 2C). Indeed, TGF-β signaling activation through either treatment with TGF-β ligand or transfection of a constitutively active version of the TGF-β type-I receptor, TβR-I, induced a 2–4-fold increase in c-Myc promoter activity, as revealed by reporter gene assays using a luciferase reporter construct that encompasses a 2.8 kb region of the human c-Myc promoter (Fig. 2C). In contrast, TGF-β reduced c-Myc expression and promoter activation in growth inhibited HaCaT cells (Fig. 2D and data not shown). The critical role of c-Myc induction in TGF-β promoted cancer cell proliferation was supported by knockdown experiments showing impaired growth stimulation by TGF-β upon c-Myc silencing (Fig. 2E). Together these results indicate that induction of the c-Myc proto-oncogene is necessary for TGF-β to promote growth in cancer cells.

FIGURE 2.

Activation of TGF-β signaling induces c-Myc promoter transactivation and expression in growth promoted cells. A, TGF-β induction of c-Myc mRNA expression was analyzed by RT-PCR in Panc-1 cells. Serum-starved cells were left untreated or treated with TGF-β for 24 h before RNA extraction. mRNA expression levels were calculated relative to basal mRNA expression, which were arbitrarily set to 1 for each experiment, and expressed as fold-induction. B, induction of c-Myc was confirmed on protein levels in Panc-1 after stimulation with TGF-β for 18 and 24 h. Total cell lysates were analyzed for c-Myc protein content using an anti-c-Myc antibody. Protein loading was controlled using anti-β-actin antibodies. C, reporter gene assays illustrating the effect of TGF-β on human c-Myc promoter activity. Cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter gene construct containing the full-length wild-type c-Myc promoter sequence along with Renilla luciferase plasmids and treated with TGF-β for 18 and 24 h, respectively. Firefly luciferase reporter gene activities were measured, normalized to TK-Renilla luciferase and expressed as mean fold induction compared with untreated control that was arbitrarily set to 1. Mean values were calculated from four independent experiments and are expressed as fold induction. D, RT-PCR and Western blot analysis to demonstrate c-Myc mRNA and protein expression in HaCaT cells upon TGF-β. Serum-starved cells were left untreated or treated with TGF-β before RNA extraction or protein isolation was performed. mRNA expression levels were calculated relative to basal mRNA expression levels and expressed as fold induction. Reduction of c-Myc was confirmed on protein levels in Panc-1 after stimulation with TGF-β for 18 and 24 h. E, relevance of c-Myc induction for TGF-β induced cell proliferation was assessed by [3H]thymidine incorporation assay upon c-Myc silencing. Panc-1 cells were transfected with either control siRNA or siRNA against c-Myc. Cells were then starved and incubated in medium with or without 10 ng/μl TGF-β for 48 h. Successful c-Myc knockdown was demonstrated by immunoblotting and cell proliferation was assessed by incorporation of [3H]thymidine in control cells and in c-Myc knockdown cells as well. Bars indicate mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Note that c-Myc depletion rendered cells refractory to TGF-β growth stimulation.

NFAT Transcription Factors Mediate c-Myc Induction by TGF-β in Cancer Cells

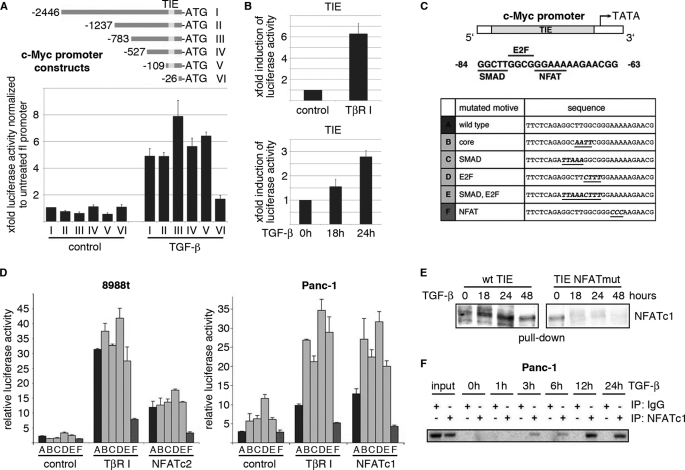

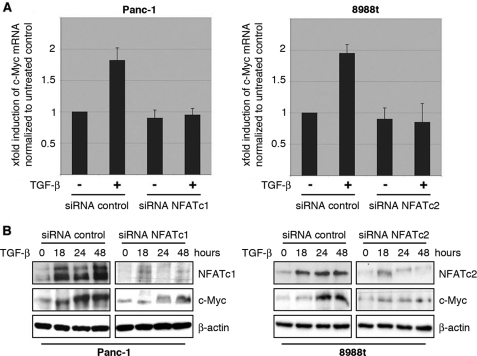

Transcription factors are essential mediators of signaling-induced gene expression. To identify the factors mediating TGF-β induction of c-Myc, we used a combination of mutagenesis analysis and reporter gene assays. Interestingly, sequential deletion of the human c-Myc promoter revealed sustained TGF-β responsiveness up to the previously identified TGF-β inhibitory element, TIE (Fig. 3A). Mutation of the TIE regulatory sequence (c-Myc del VI), however, strongly impaired TGF-β-inducibility of the c-Myc promoter in proliferating cells (Fig. 3A), though a weak induction of the remaining promoter was still detectable. Interestingly, this TIE element, located between −84 and −63 relative to the P2 transcription initiation site of the human c-Myc promoter, also denotes a prerequisite for TGF-β dependent repression of c-Myc (20, 21). In growth-inhibited epithelial cells, TGF-β represses the c-Myc/TIE element through a TTGG-core sequence, which combines an E2F-binding site with a Smad (GCTT) interacting motif (2). Site-directed mutagenesis showed that the integrity of both binding regions is required for successful inhibition of the c-Myc promoter by TGF-β. We now demonstrate that the TIE regulatory element is also used by TGF-β in proliferating cells, in this case however to stimulate the c-Myc promoter. Similar to the results obtained for the 2.8 kb wild-type c-Myc promoter TGF-β signaling significantly and time-dependently enhanced transcription from the c-Myc/TIE-promoter element in growth promoted cell lines (Fig. 3B). To elicit the functional relevance of the TTGG core sequence as well as the individual E2F- and Smad binding sites in c-Myc promoter transactivation by TGF-β, we performed experiments using wild-type and mutant versions of the c-Myc/TIE promoter (Fig. 3C). TGF-β inducibility of the c-Myc/TIE was accelerated upon mutational disruption of either the core sequence or the overlapping Smad/E2F interacting sequences, indicating that the repressor elements are still operative in proliferating cells (Fig. 3D, bars B–E). However, site-directed mutagenesis of a neighboring (GGAAA-) NFAT binding motif (located between −75 and −71 relative to the P2 transcription initiation site) led to a profound loss of TGF-β responsiveness of the c-Myc/TIE (Fig. 3D, bar F), and conversely, increased expression of NFAT transcription factors enhanced c-Myc/TIE promoter activity (Fig. 3D). These findings suggested a role of NFAT factors in TGF-β induced c-Myc promoter activation and expression in proliferating cells. In line with this, DNA pulldown and ChIP assays revealed inducible NFAT binding to the c-Myc/TIE promoter upon TGF-β stimulation (Fig. 3, E and F). Moreover, knockdown experiments demonstrated loss of c-Myc mRNA and protein induction following genetic silencing of NFAT proteins in these cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Together, these results support the fact that c-Myc is a direct transcriptional target of NFAT factors in cancer cells and suggest a role for NFAT transcription pathway in TGF-β proliferative functions.

FIGURE 3.

TGF-β induces NFAT factor binding to the c-Myc/TIE in cancer cells. A, cells were cotransfected with either the full-length c-Myc promoter construct (c-Myc del I, −2446 to +334) or the indicated deletions constructs (c-Myc del II-VI) or a control vector and treated with TGF-β. Firefly luciferase reporter gene activities were measured, normalized to TK-Renilla luciferase and expressed as fold induction compared with full-length c-Myc (del I). B, cells were transfected with the c-Myc/TIE reporter gene construct (−84 to −63) and TGF-β signaling was initiated through either treatment with TGF-β or co-transfection of TβR-I. Reporter gene activities were expressed as mean fold induction compared with untreated control, which was arbitrarily set to 1. Mean values were calculated from three independent experiments and are shown as mean ± S.D. C, schematic representation of the human c-Myc TIE element including previously identified binding sites for SMADs and E2F4. The GGAAA NFAT consensus sequence is also indicated. The table below displays the individual or combined mutations targeting these transcription factor binding sites as used for luciferase reporter gene assays (TIE mutants A-F). D, 8988t and Panc-1 cells were transfected with the indicated wild-type c-Myc/TIE construct (bar A) or mutant c-Myc/TIE reporter constructs (bars B–F), along with TβR-I or wild-type NFATc1/NFATc2 expression plasmids. Reporter gene activities were expressed as RLA (relative luciferase activities). Mean values were calculated from three independent experiments which were performed in triplicates. Bars indicate mean values ± S.D. E, DNA pulldown assays using double-stranded oligonucleotides of wild-type and mutant TIE with disruption of the NFAT binding site. Panc-1 cells were serum starved and then treated with TGF-β for 18, 24, or 48 h. Nuclear extracts were prepared and incubated with either wild type-TIE or TIE-NFATmut oligonucleotides. DNA-protein complexes were precipitated with streptavidin-agarose beads and NFAT binding was analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-NFATc1 antibody. F, ChIP were performed with specific NFATc1 antibodies and in vivo binding to the c-Myc promoter was determined by semi-quantitative PCR using primers specific for the c-Myc promoter region harboring the TIE element.

FIGURE 4.

NFAT expression is required for c-Myc induction by TGF-β. A, cancer cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA against NFAT proteins. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were serum-starved and then treated with either medium alone or medium containing 10 ng/μl TGF-β. cDNA was prepared and subjected to qRT-PCR to analyze the effect of NFAT knockdown on c-Myc mRNA expression in Panc-1 (left) and PaTu8988t (right) cells. Values were calculated relative to basal mRNA expression levels in control siRNA-transfected cells, which were arbitrarily set to 1 for each experiment. Displayed are mean values from three independent experiments ± standard deviations. B, protein extracts from TGF-β-treated cancer cells transfected with either nonspecific control siRNA or NFAT-siRNA were subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies specific for NFATc1, NFATc2 or c-Myc. Protein loading was controlled using anti-β-actin antibodies.

TGF-β Modulates NFAT Activity in a Smad-independent Manner via the Oncogenic Calcineurin Pathway

The NFAT family of proteins comprises five transcription factors particularly recognized for their central roles in gene regulation during T-lymphocyte activation (22, 23). Recent studies have demonstrated that NFAT proteins posses oncogenic functions and control critical molecular mechanisms in active proliferating cells during carcinogenesis (16, 24–25). NFATc1 and NFATc2 are both expressed in our cell models, though none of the studied cell lines revealed co-expression of both transcriptional regulators. NFATc1 expression was detected in Panc-1 cells, whereas NFATc2 was found in HT-29, SW-480, and PaTu8988t cells (data not shown). More importantly, TGF-β treatment strongly induced NFAT expression through promoter transactivation. Depending on the cell type and the duration of stimulation, TGF-β induced a 3–5-fold induction of the human NFATc1 and NFATc2 promoters, causing a dramatic and sustained increase in expression. (Figs. 4B and 5, A and B); thus, this result suggests a potential mechanism mediating TGF-β up-regulation of NFAT factors in cancer cells. Interestingly, TGF-β induction of the NFAT proteins does not require the presence of Smad signaling molecules. All studied cells independent of the presence or absence of Smad4 expression respond to TGFβ with increased promoter transactivation and expression of NFAT proteins (Fig. 5, A and B and data not shown). In addition, TGF-β inducibility persisted upon siRNA-mediated knockdown of Smad3 (Fig. 5C), Smad2 or a combination of both proteins (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). Furthermore, Smad3-null MEFs consistently responded to TGF-β treatment with a significant induction of NFATc2 (supplemental Fig. S1C), again supporting that this effect was independent of Smad3. Finally, neither transfection of Smad3 nor Smad4 enhanced the level of NFAT promoter activity in growth promoted cancer cells (Fig. 6A), whereas the TARE-Luc reporter plasmid containing a series of Smad binding elements was nicely induced by Smad factors (supplemental Fig. S1D).

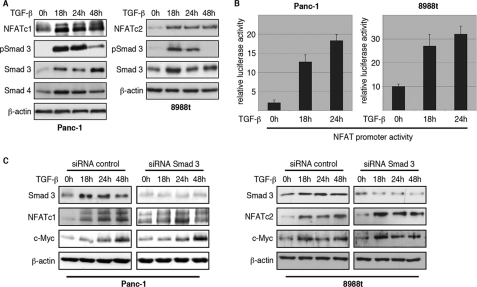

FIGURE 5.

Smad3-independent induction of NFAT proteins by TGF-β. A, Western blot analysis to show time-dependent TGF-β induction of NFAT factors in Panc-1 and PaTu8988t cells. Cells were serum-starved and then treated with TGF-β for the indicated time periods. Increased phosphorylation of Smad3 indicates successful treatment. Protein loading was controlled using anti-β-actin antibodies. B, reporter gene assays were performed in Panc-1 and PaTu8988t cells following transfection of the human NFATc1 and NFATc2 promoters and treatment with 10 ng/μl TGF-β for 18 and 24 h, respectively. Firefly luciferase reporter gene activities of the NFAT promoters were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity and expressed as RLA. Bars indicate mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicates. Note that both NFAT promoters are induced by TGF-β. C, Panc-1 (left panel) and PaTu8988t (right panel) cells were transfected with siRNA against Smad3 or control siRNA, serum-starved, and treated with medium alone or medium containing TGF-β for 18, 24, or 48 h. Proteins were extracted and immunoblot analyses were performed to determine successful depletion of Smad3 and its impact on the expression levels of NFATc1, NFATc2, and c-Myc in cancer cells. Note that neither NFAT nor c-Myc expression was affected following depletion of Smad3.

FIGURE 6.

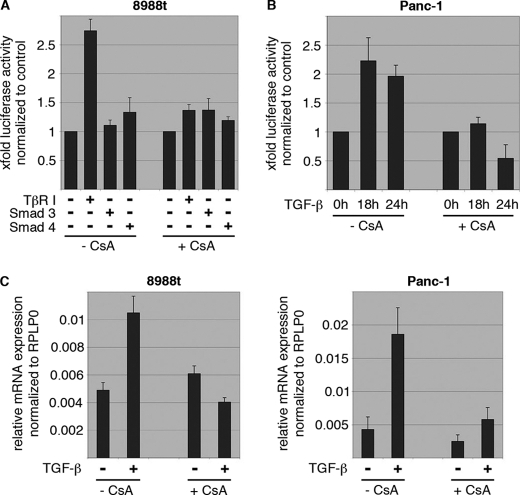

NFAT induction by TGF-β requires calcineurin phosphatase activity. A, reporter gene assays to define NFATc2 promoter regulation by Smads and CsA treatment. Cells were transfected with the human NFATc2 promoter along with either TβR-I or the Smads and incubated in the presence or absence of CsA to block endogenous calcineurin activity. Note that TGF-β induced NFATc2 promoter activation was antagonized by pharmacological inhibition of calcineurin. The NFATc2 promoter was not responsive to Smads. B, reporter gene assays to define NFATc1 promoter regulation by TGF-β and CsA. Cells were transfected with the human NFATc1 promoter and treated with either TGF-β, CsA, or a combination of both agents. Reporter gene activities were expressed as mean fold induction compared with untreated control that was arbitrarily set to 1. C, qRT-PCR to analyze the effect of CsA treatment on NFAT mRNA expression in response to TGF-β in PaTu8988t (left) and Panc-1 (right) cells. Displayed are mean values from three independent experiments ± S.D.

In contrast, application of cyclosporine A (CsA), an inhibitor of the phosphatase calcineurin, diminished NFAT induction by TGF-β on both promoter activity (Fig. 6, A and B) levels and mRNA expression (Fig. 6C), indicating that TGF-β utilizes the Ca2+/calcineurin-signaling pathway to induce a positive NFAT feedback loop in proliferating cells. This conclusion is further supported by the calcineurin activity assays, demonstrating a 2-fold induction of calcineurin by TGF-β in growth-promoted cancer cells (supplemental Fig. S1E). Thus, NFAT promoter activation by TGF-β occurs in a Smad-independent manner but requires an active calcineurin phosphatase pathway.

NFAT Antagonizes a Smad3 Repressor Complex to Activate the c-Myc Promoter

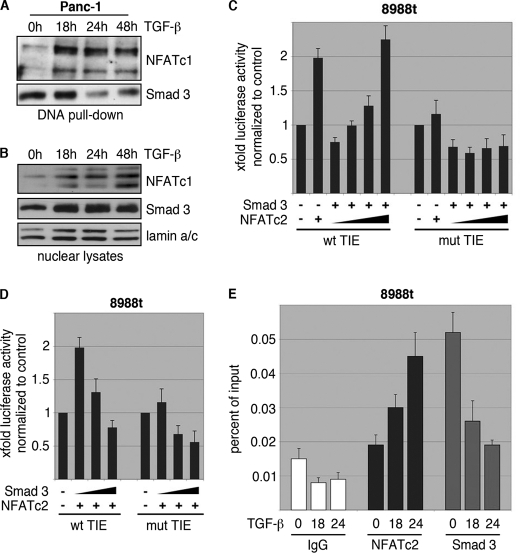

Recent studies in growth-inhibited cells convincingly demonstrated that Smad3 binding to the TIE element is a prerequisite for c-Myc repression and the resulting growth inhibition (2). We now show that Smad3 is expressed and still operative on the c-Myc/TIE element in cancer cells with low NFAT levels, but is fully inactivated upon induction of NFAT in response to TGF-β. In fact, in vitro and in vivo binding of Smad3 to the c-Myc/TIE element was found in all cancer cells when cultured in the absence of TGF-β (Fig. 7, A, E, and supplemental Fig. S1F). Accordingly, reporter gene assays demonstrated that Smad3 is active on the c-Myc/TIE element in cancer cells and represses the promoter activity of this transcription factor (Fig. 7, C and D). However, accumulation of NFAT through activation of the TGF-β pathway interfered with Smad3 promoter binding and displaced this transcription factor from the c-Myc/TIE promoter in vitro and in vivo, as revealed by DNA pulldown assays and ChIP experiments (Fig. 7, A, B, E, and supplemental Fig. S1F). The functional competition between NFAT and Smad3 for c-Myc/TIE promoter binding and regulation was confirmed by reporter gene assays demonstrating antagonistic effects of NFAT and Smad3 on the c-Myc/TIE promoter (Fig. 7, C and D). As such, increasing amounts of NFAT override Smad3-mediated repression to induce transcription from c-Myc/TIE element in cancer cells (Fig. 7B). Together, these experiments defined a novel TGF-β transcriptional mechanism involved in the regulation of c-Myc expression and promoter activity, which requires induction of NFAT factors and the subsequent antagonistic interplay between NFAT factors and Smad3 in cancer cells.

FIGURE 7.

NFAT displaces Smad3 from the c-Myc/TIE upon TGF-β. A, DNA pulldown experiment demonstrating inverse binding of NFAT factors and Smad3 on the c-Myc/TIE upon TGF-β. Nuclear extracts from Panc-1 cells were prepared and incubated with the wild-type c-Myc/TIE oligonucleotide sequence. DNA-protein complexes were precipitated with streptavidin-agarose beads, and NFAT/Smad3 binding was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-NFATc1 and anti-Smad3 antibodies, respectively. Note the inverse binding of NFAT factors and Smad3 on the c-Myc/TIE sequence upon treatment with TGF-β. B, nuclear extracts which were used for DNA pulldown experiments. C and D, reporter gene assay shows that c-Myc/TIE promoter induction depends on the integrity of the NFAT binding site and the amount of NFAT and Smad3. PaTu8988t cells were transfected with c-Myc/TIE wild type or c-Myc/TIE mutant that lacks the NFAT binding site along with increasing amounts of either NFATc2 (C) or Smad3 (D). c-Myc promoter activities were expressed as mean fold induction. Mean value were calculated from three independent experiments and are shown as mean ± S.D. E, chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed in PaTu8988 cells following TGF-β treatment over 18 and 24h using specific NFATc2 and Smad3 antibodies. In vivo binding of both transcription factors to the c-Myc promoter was determined by quantitative PCR using primers specific for the c-myc promoter region harboring the c-Myc/TIE. ChIP assay demonstrates inverse binding of Smad3 and NFAT to the c-Myc/TIE upon TGF-β.

NFAT Mediates the TGF-β Switch from a Growth Suppressor to a Promoter of Cell Proliferation

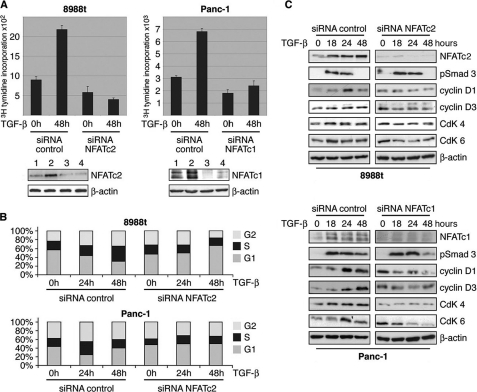

Finally, we investigated the functional relevance of NFAT in TGF-β promoted cell cycle progression and growth. Similar to the profound effects of c-Myc knockdown (as demonstrated in Fig. 2E) depletion of NFAT factors fully prevented growth stimulation by TGF-β in cancer cell lines (Fig. 8A). In fact, NFAT knockdown was associated with decreased basal cell proliferation and a complete loss of TGF-β induction. Moreover, NFAT silencing partially restored the growth inhibitory response of cancer cells to TGF-β (Fig. 8A), as evidenced by down-regulation of the cell cycle regulatory genes and an increased halt of cancer cells in G1 upon treatment (Fig. 8, B and C). Taken together, these findings established NFAT proteins as central TGF-β players in cancer cells and strongly support a key role of these transcription factors in the molecular switch controlling the fate of TGF-β growth response.

FIGURE 8.

NFAT proteins mediate the TGF-β switch from growth suppressor to a promoter of cell proliferation. A, relevance of NFAT expression for TGF-β-induced cell proliferation was assessed by [3H]thymidine incorporation assay upon NFAT silencing. PaTu8988t and Panc-1 cells were transfected with either control siRNA or siRNA against NFAT. Cells were then starved and incubated in medium with or without 10 ng/μl TGF-β for 48 h. Bars indicate mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Note that NFAT depletion rendered cells refractory to growth stimulation and partially restored TGF-β growth suppressor activities in PaTu8988T cells. Successful NFAT knockdown was demonstrated by immunoblotting using specific antibodies against NFATc1 and NFATc2 (bottom panel: control siRNA (lane 1), control siRNA + TGF-β (lane 2), siRNA NFAT (lane 3), and siRNA NFAT + TGF-β (lane 4)). B, flow cytometry analysis to study the relevance of NFAT factors in TGF-β induced cell cycle progression of cancer cells. NFAT knockdown cells were treated with TGF-β for 24 or 48 h, respectively, and analyzed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Cell cycle stages are illustrated in different colors: G2, S, and G1. Loss of NFAT expression restored cell cycle inhibition by TGF-β, as evidenced by increased cells in the G1 phase. Bars indicate mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, Western blot analysis demonstrating TGF-β regulated cell cycle genes depending on the presence or absence of NFAT expression. Cells were transfected with siRNA against NFATc2 or unspecific control siRNA, serum-starved, and subsequently treated with 10 ng/μl TGF-β for 18, 24, or 48 h. Total cell lysates were then analyzed for expression of NFAT, D-type cyclins and the partnering kinases (CdKs). Protein loading was controlled using anti-β-actin antibodies.

DISCUSSION

TGF-β mediated signaling has a significant role in the regulation of cancer, initially as a tumor suppressor and then as a positive mediator of tumor progression (26, 27). Clearly, TGF-β growth suppressor activities are primarily depending on its potential to repress cell proliferation through Smad-dependent transcriptional silencing of c-Myc and subsequent induction of p15Ink4b and p21Cip1 (4, 7, 15). During carcinogenesis, however, virtually all epithelial-derived tumors become resistant to the growth-inhibitory effects of TGF-β due to either mutational or functional inactivation of the TGF-β/Smad pathway (28–30). However, impaired Smad signaling causes an incomplete loss of TGF-β responsiveness that particularly targets its growth inhibitory potential while other tumor-related functions remain unaffected (13, 30–32). Depending on the cell type, TGF-β can then signal through diverse Smad-independent pathways including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) cascade and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway to promote cancer progression characterized by the acquisition of a mesenchymal phenotype and increased tumor cell migration and invasion (33, 34). In addition, TGF-β can switch to a growth promoter and stimulates the proliferation of numerous epithelial-derived cancer cell lines, including colon and pancreatic cancer cells (35–37). Although this cellular event is clearly established, the molecular mechanisms underlying the TGF-β switch to a growth-promoter in cancer cells are still unknown. With the goal to dissect the mechanisms behind TGF-β ability to regulate these two opposing effects on cell growth, we conducted the presented study and uncovered a novel transcriptional pathway that mediates the TGF-β-growth switch from a suppressor to a promoter of cell proliferation. Using a battery of biochemical and molecular approaches we show that TGF-β exerts its proliferative function in cancer cells through transcriptional induction of the c-Myc oncogene, which causes enhanced levels of D-type cyclins and their kinase partners and consequently drives cells through the G1 cell cycle phase. Intriguingly, c-Myc activation by TGF-β occurs independent of the Smad pathway but requires prior induction and activation of the calcineurin responsive NFAT transcription factors. The NFAT family of transcription factors comprises four members of Ca2+/calcineurin regulated proteins particularly recognized for their central roles in gene regulation during T-lymphocyte activation (22, 39). In resting cells, NFAT is located in the cytoplasm as a hyperphosphorylated, inactive form. Under these conditions, NFAT phosphorylation is insured by the combined action of several maintenance kinases, including CK1 and DYRK2 that target specific serine residues in the NFAT conserved regulatory domain. Signaling through calcium/calcineurin results in NFAT proteins dephosphorylation, causing a conformational switch that unmasks their nuclear localization sequence (NLS) and allows their translocation to the nucleus, where they bind to specific DNA response elements to regulate transcription (24, 40). Recent studies have convincingly demonstrated that NFAT signaling and transcriptional regulation is not restricted to the immune system. Instead, NFAT proteins control critical molecular mechanisms during development and carcinogenesis (24, 41). For instance, ectopically expressed NFATc1 and NFATc2 have been implicated in tumor cell growth and migration in various epithelial tumors, including those arising from the pancreas, breast, and colon (17, 42). Here, we describe a novel function of NFATc1 and NFATc2 factors in carcinogenesis and demonstrate that the induction and activation of both proteins is essential for TGF-β to switch from a growth suppressor to an inducer of cancer cell proliferation. TGF-β induces in a calcineurin dependent manner the transcription of both proteins, which in turn function as downstream effector proteins to induce c-Myc transcription and cell cycle progression in cancer cells. Interestingly, c-Myc promoter induction by NFAT factors requires the antagonism of Smad3 repression. Chen et al. have demonstrated that Smad3 repression of the c-Myc promoter is a requirement for TGF-β induced cell growth arrest (2, 20). We now demonstrate that NFAT transcription factors accumulate in the nucleus and displace Smad3 repressor complexes from the previously described TGF-β inhibitory element (TIE) of the proximal c-Myc promoter to induce transcription. Strikingly, genetic NFAT silencing not only prevents c-Myc induction and proliferation, but also restores TGF-β growth suppressor functions in cancer cells as evidenced by down-regulation of D-type cyclins and a halt of cancer cells in G1. Thus, this study identified NFAT transcription factors as key regulators in the TGF-β switch from a growth suppressor to a proliferative pathway. Based on our findings we propose a model in which TGF-β induces NFAT protein expression and nuclear accumulation in cancer cells to displace promoter-bound Smad3 and induce transcription of mitogenic c-Myc. These findings emphasize a peculiar role of NFAT factors in Smad-independent gene expression and contribute to better understand the complex network of molecular events underlying the TGF-β function in cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, SFB-TR17, and KFO 210) and the Max Eder programme of the German Cancer Research Foundation (Deutsche Krebshilfe, 70-3022-El I) (to V. E.). This work was also supported by the Division of Oncology Research, Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Miles and Shirley Fiterman Center for Digestive Disease, CA136526, Carole and Bob Daly AACR-PANCAN Career Development Award for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Mayo Clinic Pancreatic SPORE P50 CA102701, Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (NIDDK P30DK084567), and Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Translational Research Program (to M. E. F.-Z.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- TGF

- transforming growth factor

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

- CsA

- cyclosporine A

- TIE

- TGF-β inhibitory element

- wt

- wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1.Massagué J. (2008) Cell 134, 215–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen C. R., Kang Y., Siegel P. M., Massagué J. (2002) Cell 110, 19–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannon G. J., Beach D. (1994) Nature 371, 257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staller P., Peukert K., Kiermaier A., Seoane J., Lukas J., Karsunky H., Möröy T., Bartek J., Massagué J., Hänel F., Eilers M. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 392–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seoane J., Pouponnot C., Staller P., Schader M., Eilers M., Massagué J. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 400–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orian A., Eisenman R. N. (2001) Sci STKE 26, 88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massagué J., Blain S. W., Lo R. S. (2000) Cell 103, 295–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon K. J., Blobe G. C. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1782, 197–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heldin C. H., Landström M., Moustakas A. (2009) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 166–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Y., Massagué J. (2003) Cell 113, 685–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy L., Hill C. S. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 8108–8125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seoane J. (2006) Carcinogenesis 27, 2148–2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kretzschmar M., Doody J., Timokhina I., Massagué J. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 804–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calonge M. J., Massagué J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33637–33643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts A. B., Wakefield L. M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8621–8623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore P. S., Sipos B., Orlandini S., Sorio C., Real F. X., Lemoine N. R., Gress T., Bassi C., Klöppel G., Kalthoff H., Ungefroren H., Löhr M., Scarpa A. (2001) Virchows Arch. 439, 798–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchholz M., Schatz A., Wagner M., Michl P., Linhart T., Adler G., Gress T. M., Ellenrieder V. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 3714–3724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pardali K., Kurisaki A., Morén A., ten Dijke P., Kardassis D., Moustakas A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29244–29256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frederick J. P., Liberati N. T., Waddell D. S., Shi Y., Wang X. F. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2546–2559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen C. R., Kang Y., Massagué J. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 992–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Im S. H., Rao A. (2004) Mol. Cells 18, 1–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macian F. (2005) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 472–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoeli-Lerner M., Chin Y. R., Hansen C. K., Toker A. (2009) Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 425–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medyouf H., Ghysdael J. (2008) Cell Cycle 7, 297–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robbs B. K., Cruz A. L., Werneck M. B., Mognol G. P., Viola J. P. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 7168–7181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ten Dijke P., Goumans M. J., Itoh F., Itoh S. (2002) J. Cell. Physiol. 191, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bierie B., Moses H. L. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 506–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hahn S. A., Schutte M., Hoque A. T., Moskaluk C. A., da Costa L. T., Rozenblum E., Weinstein C. L., Fischer A., Yeo C. J., Hruban R. H., Kern S. E. (1996) Science 271, 350–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodford-Richens K. L., Rowan A. J., Gorman P., Halford S., Bicknell D. C., Wasan H. S., Roylance R. R., Bodmer W. F., Tomlinson I. P. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9719–9723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott R. L., Blobe G. C. (2005) J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 2078–2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Caestecker M. P., Piek E., Roberts A. B. (2000) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 1388–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engel M. E., McDonnell M. A., Law B. K., Moses H. L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37413–37420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Javelaud D., Mauviel A. (2005) Oncogene 24, 5742–5750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derynck R., Zhang Y. E. (2003) Nature 425, 577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellenrieder V. (2008) Anticancer Res. 28, 1531–1539 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonson T., Albrechtsson E., Axelson J., Heidenblad M., Gorunova L., Johansson B., Höglund M. (2001) Int. J. Oncol. 19, 71–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan Z., Kim G. Y., Deng X., Friedman E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9870–9879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deleted in proof

- 39.Serfling E., Berberich-Siebelt F., Avots A. (2007) Sci STKE 398, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rao A., Luo C., Hogan P. G. (1997) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 707–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchholz M., Ellenrieder V. (2007) Cell Cycle 6, 16–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jauliac S., López-Rodriguez C., Shaw L. M., Brown L. F., Rao A., Toker A. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 540–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.