Abstract

A potentially useful trianionic ligand for the reduction of dinitrogen catalytically by molybdenum complexes is one in which one of the arms in a [(RNCH2CH2)3N]3− ligand is replaced by a 2-mesitylpyrrolyl-α-methyl arm, i.e., [(RNCH2CH2)2NCH2(2-MesitylPyrrolyl)]3− (R = C6F5, 3,5-Me2C6H3, or 3,5-t-Bu2C6H3). Compounds have been prepared that contain the ligand in which R = C6F5 ([C6F5N)2Pyr]3−); they include [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2), [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl, [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoOTf, and [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoN. Compounds that contain the ligand in which R = 3,5-t-Bu2C6H3 ([Art-BuN)2Pyr]3−) include {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(15-crown-5), {[(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}[NBu4], [(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]Mo(N2) (νNN = 2012 cm−1 in C6D6), {[(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4, and [(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]Mo(CO). X-ray studies are reported for [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2), [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl, and [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoN. The [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)0/− reversible couple is found at −1.96 V (in PhF versus Cp2Fe+/0), but the [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)+/0 couple is irreversible. Reduction of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4 under Ar at approximately −1.68 V at a scan rate of 900 mV/sec is not reversible. Ammonia in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3) can be substituted for dinitrogen in about 2 hours if 10 equivalents of BPh3 are present to trap the ammonia that is released. [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo-N=NH is a key intermediate in the proposed catalytic reduction of dinitrogen that could not be prepared. Dinitrogen exchange studies in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) suggest that steric hindrance by the ligand may be insufficient to protect decomposition of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo-N=NH through a variety of pathways. Three attempts to reduce dinitrogen catalytically with [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N) as a “catalyst” yielded an average of 1.02 ± 0.12 equivalents of NH3.

Introduction

Nitrogenase enzymes (in algae and bacteria) convert dinitrogen to ammonia, but despite intensive study, the mechanism of this conversion is not well understood.1 Discovery of the first transition metal dinitrogen complex, [Ru(NH3)5(N2)]+,2 inspired syntheses of other transition metal dinitrogen complexes in the hope that an abiological method of reducing dinitrogen under mild conditions could be devised, one that might eventually compete with or replace the Haber-Bosch process.3 Work concerning dinitrogen functionalization continues today on several fronts.4,5,6,7

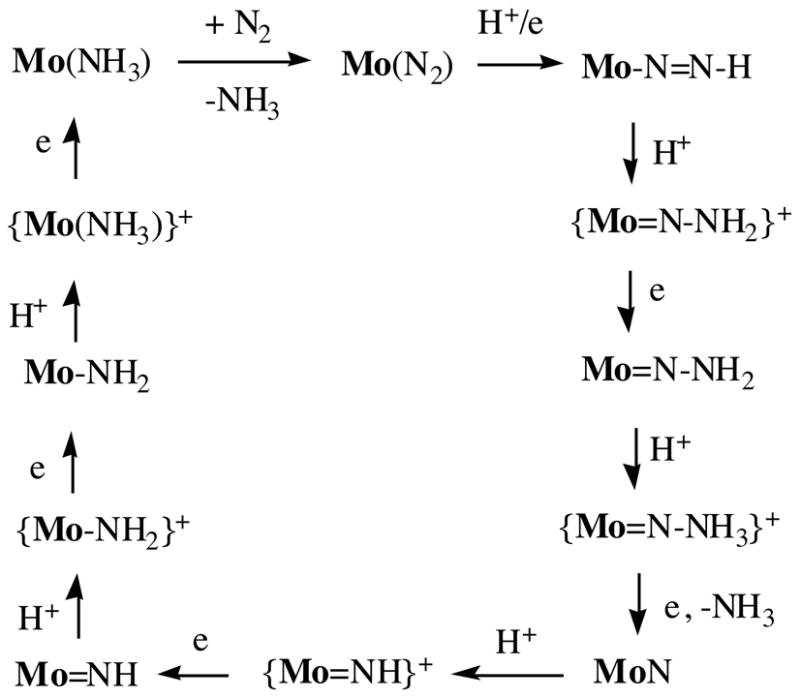

Only two systems are known in which dinitrogen can be reduced catalytically to ammonia under mild conditions. The first, reported by Shilov,3h requires molybdenum and a strong reducing agent in methanol. Dinitrogen is reduced first to hydrazine, which is then disproportionated to dinitrogen and ammonia. A typical product is a 1:10 mixture of ammonia and hydrazine. The second catalytic process is selective for formation of ammonia.8 Dinitrogen is reduced at room temperature and ambient pressure at a single Mo center protected by a sterically demanding, hexaisopropylterphenyl-substituted triamidoamine ligand, [(3,5-(2,4,6-i-Pr3C6H2)2C6H3NCH2CH2N)3N]3− ([HIPTN3N]3−). Eight of the intermediates in the proposed reduction sequence (Figure 1) were prepared and characterized and several were employed for catalytic N2 reduction. Slow addition of CrCp*2 (Cp* = η5-C5Me5−) to a heptane solution of [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2), [HIPTN3N]MoN, [HIPTN3N]MoN=NH, or {[HIPTN3N]Mo(NH3)}+ containing sparingly soluble [2,6-lutidinium][BAr′] (Ar′ = 3,5-(CF3)2C6H3) led to catalytic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia, with approximately one equivalent of dihydrogen being formed per dinitrogen reduced. The maximum yield of ammonia is approximately eight equivalents (four turnovers).

Figure 1.

Proposed intermediates in the reduction of dinitrogen at a [HIPTN3N]Mo (Mo) center (HIPT = hexaisopropylterphenyl) through stepwise addition of protons and electrons.

Synthesis and investigation of several variations of the [HIPTN3N]3− ligand system have shown that use of sterically less demanding ligands or more sterically demanding ligands (the hexa-t-butylterphenyl analog) lead to a decrease in the efficiency of dinitrogen reduction, or even loss of catalytic activity entirely.9 [HIPTN3N]Mo complexes currently are the most efficient catalysts. Analogous vanadium,10 chromium,11 and tungsten12 systems showed no catalytic activity. Calculations have been carried out on the molybdenum catalyst system,13 including DFT calculations with the full ligand,14 that support the proposed mechanism for dinitrogen reduction in the [HIPTN3N]Mo system.

One of the main reasons why dinitrogen reduction is limited to approximately four turnovers is that the [HIPTN3N]3− ligand is protonated at an amido nitrogen and ultimately removed from the metal in the presence of reducing agent and acid.8e,f Replacing the substituted amido groups in the triamidoamine ligand by pyrrolyl (or pyrrolide) groups was the rationale for the synthesis of complexes that contain a tris(pyrrolyl-α-methyl)amine ligand.15 However, replacing the three HIPT-substituted amido groups with three substituted pyrrolyl groups is too large a perturbation on the already sensitively electronically and sterically balanced [HIPTN3N]3− ligand system; a significant problem proved to be binding the tris(pyrrolyl-α-methyl)amine ligand to the metal in a tetradentate fashion. Therefore we turned to the construction of a variation in which one ArNCH2CH2 arm in the trianionic triamidoamine ligand is replaced by a pyrrolyl-α-methyl arm; a “diamidopyrrolyl” complex, as shown in Figure 2, became the target. The Ar′ group bound to the α carbon atom in the pyrrolyl (e.g., Ar′ = mesityl) should provide a significant amount of steric protection of a ligand in the apical coordination site. A pyrrolyl would seem less likely to be protonated than an amido nitrogen, and if the pyrrolyl is protonated, the proton is likely to add to an α or β carbon atom to yield a pyrrolenine bound to a cationic metal center, as has been shown recently for a cationic tungsten complex.16 A pyrrolenine donor is likely to bind more strongly to a cationic metal center than the aniline formed upon protonation of an amido ligand. Consequently, protonation of a pyrrolyl ligand may yield a relatively stable cationic species. Therefore we felt that a catalyst that contains a diamidopyrrolyl ligand could turn out to be a more stable catalyst for dinitrogen reduction, assuming that all other requirements are met. We report here efforts to prepare complexes that contain diamidopyrrolyl ligands and that function as catalysts for reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia.

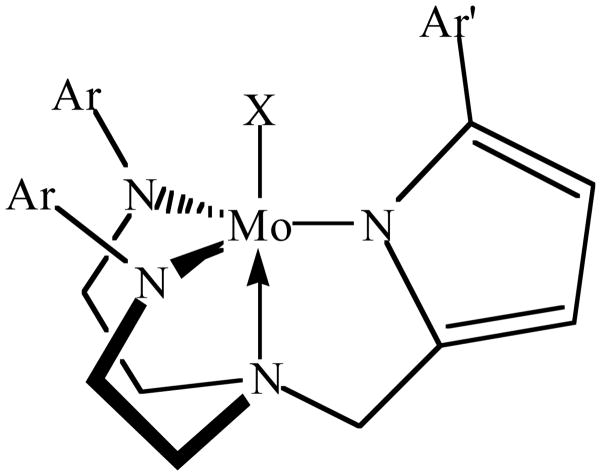

Figure 2.

A “diamidopyrrolyl” complex.

RESULTS

Synthesis of diamidopyrrolyl complexes in which Ar = C6F5 and Ar′ = Mesityl

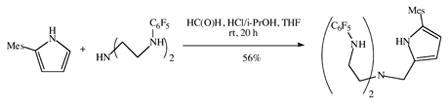

A Mannich reaction between 2-mesitylpyrrole17 and (C6F5NHCH2CH2)2NH (equation 1) led to formation of H3[(C6F5N)2Pyr], a triprotonated version of the trianionic ligand shown in Figure 2 in which Ar = C6F5 and Ar′ = Mesityl. H3[(C6F5N)2Pyr] was obtained as a white powder upon recrystallization of the crude product from a mixture of toluene and pentane.

|

(1) |

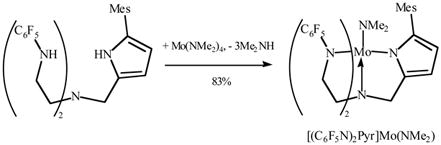

An emerald green solution forms rapidly upon mixing solutions of H3[(C6F5N)2Pyr] and Mo(NMe2)4 at room temperature, and green, crystalline, essentially diamagnetic [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) could be isolated in 83% yield (equation 2). A single crystal X-ray diffraction study (Figure 3) showed that the coordination geometry is approximately trigonal bipyramidal with the mesityl substituent on the pyrrolyl ring pointing straight up. The dimethylamido ligand is planar and the N(5)-Mo(1) distance is 1.9383(12) Å, both of which are consistent with the amido ligand being doubly bound to the metal. The plane of the amido ligand is approximately parallel to the plane of the mesityl ring. The Mo(1)-N(4) bond length (2.2630(12) Å) is similar to what is found in related triamidoamine ligand systems, and longer than Mo(1)-N(3) (1.9539(12) Å) and Mo(1)-N(2) (1.9688(12) Å. The Mo(1)-N(1) bond length (2.081 Å) is slightly longer than the Mo-Namido bonds and the average Mo(1)-Npyrrolyl bond length (2.007 Å) in a tris(pyrrolyl-α-methyl)amine molybdenum chloride complex,15 but approximately what is found for Mo-Npyrrolyl bonds in several molybdenum-η1-pyrrolyl complexes.18

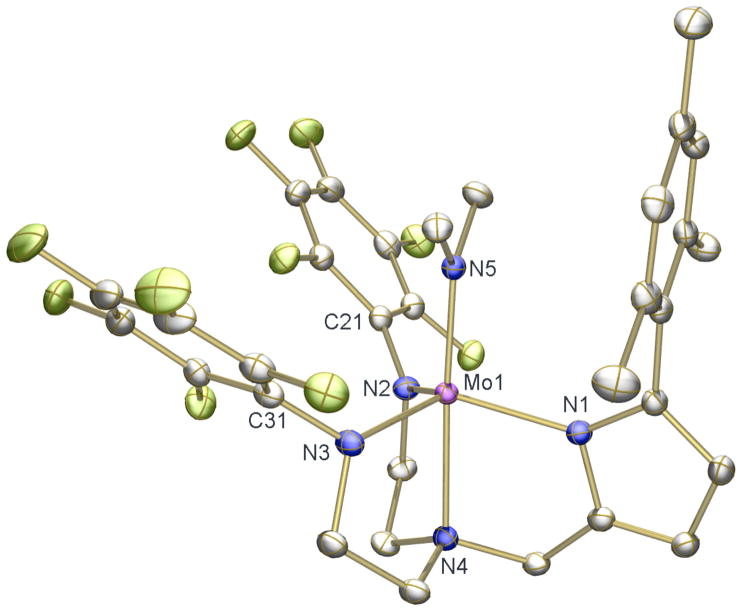

Figure 3.

Thermal ellipsoid drawing (50% probability) of the solid state structure of [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2). H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (°): N(5)-Mo(1) = 1.9383(12), Mo(1)-N(3) = 1.9738(12), Mo(1)-N(2) = 1.9885(12), Mo(1)-N(1) = 2.0807(12), Mo(1)-N(4) = 2.2630(12), C(21)-N(2)-Mo(1) = 129.36(10), C(31)-N(3)-Mo(1) = 128.3(3), N(1)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 77.26(5), N(2)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 78.61(5), N(3)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 77.51(5), N(5)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 176.92(5).

|

(2) |

The chemical shift of the dimethylamido protons in the proton NMR spectrum of [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) is temperature dependent, a phenomenon that is analogous to what is found for the triamidoamine complexes, [TMSN3N]Mo(NMe2) ([TMSN3N]3− = [(Me3SiNCH2CH2)3N]3−)19 and [C6F5N3N]Mo(NMe2),20 and which is consistent with a rapid interconversion of diamagnetic (S = 0) and paramagnetic (S = 1) forms.21 The changes in the chemical shifts of the dimethylamido protons in [TMSN3N]Mo(NMe2) (~9 ppm from 180 to 304 K) and [C6F5N3N]Mo(NMe2) (~2.8 ppm from 259–367 K) are larger than in [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) (0.12 ppm from 233–302 K; see Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). If we assume that the temperature dependent chemical shifts are a consequence of interconversion of high spin and low spin forms, then ΔH° is calculated to be 27(15) kJ mol−1; although ΔH° for [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) cannot be calculated accurately, the energy difference between the high and low spin states of [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) clearly is much greater than that in [TMSN3N]Mo(NMe2) (ΔH° = 9.9(1.3) kJ mol−1) or [C6F5N3N]Mo(NMe2) (ΔH° = 10.2(1.4) kJ mol−1).

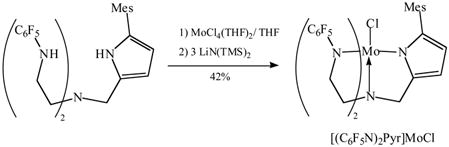

Addition of LiN(TMS)2 to a mixture of H3[(C6F5N)2Pyr] and MoCl4(THF)2 in THF results in a rapid color change from red-orange to magenta. Paramagnetic reddish-pink [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl can be isolated from the mixture in 42% yield (equation 3). The solid-state structure of [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl (Figure 4) reveals it to be a TBP species similar to [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) (Figure 3). The Mo(1)-N(1) bond length (2.0184(12) Å) is longer than that for Mo(1)-N(3) (1.9539(12) Å) or Mo(1)-N(2) (1.9688(12) Å), as found in [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2).

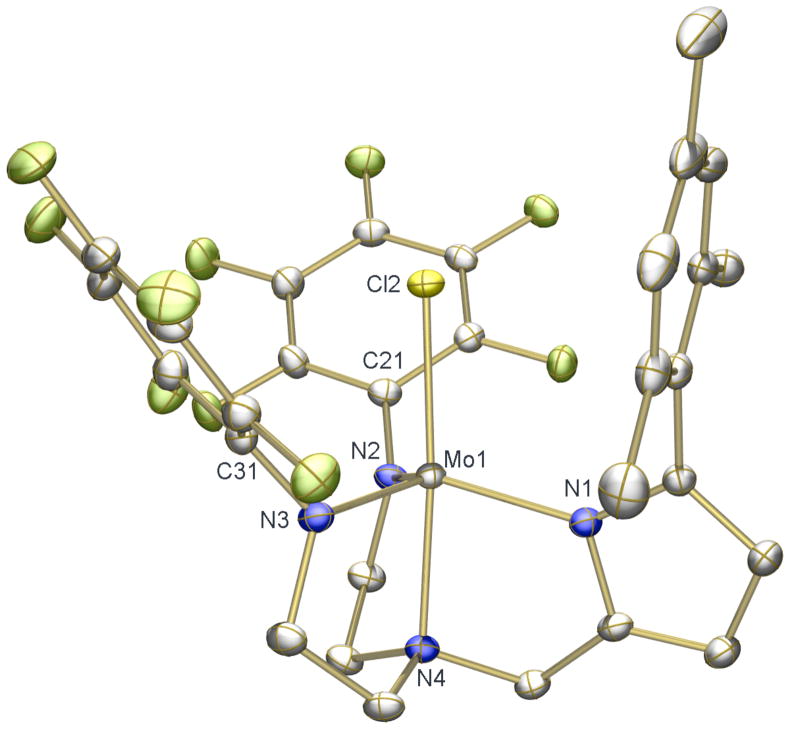

Figure 4.

Thermal ellipsoid drawing (50% probability) of the solid state structure of [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (°): Cl(2)-Mo(1) = 2.3583(4), Mo(1)-N(3) = 1.9539(12), Mo(1)-N(2) = 1.9688(12), Mo(1)-N(1) = 2.0184(12), Mo(1)-N(4) = 2.1737(12), C(21)-N(2)-Mo(1) = 125.99(10), C(31)-N(3)-Mo(1) = 123.41(10), N(1)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 79.05(5), N(2)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 79.49(5), N(3)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 79.98(5), N(4)-Mo(1)-Cl(2) = 174.98(3).

|

(3) |

A reaction between [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl and AgOTf led to formation of paramagnetic, orange [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoOTf in approximately 40% yield, while a reaction between [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl and NaN3 in acetonitrile at 70 °C over a period of 72 hours led to formation of yellow, diamagnetic [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoN. Both reactions are similar to those reported in related triamidoamine complexes.

Attempts to reduce [(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl in THF under dinitrogen with sodium, KC8, or Mg, or [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(OTf) with Mg powder (activated with 1,2-dichloroethane) so far have not led to any isolable dinitrogen-containing species such as [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(N2) or {[(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}−. It should be pointed out that the [(C6F5NCH2CH2)3N]Mo system20 also is compromised relative to analogous [(ArylNCH2CH2)3N]Mo systems in which the aryl is not fluorinated as far as syntheses of dinitrogen complexes are concerned. Therefore we turned to the synthesis of diamidopyrrolyl complexes that contain nonfluorinated aryl substituents on the amido ligands.

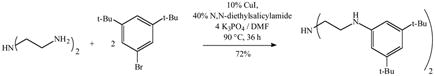

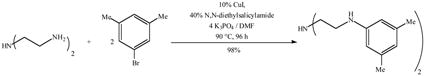

Synthesis of diamidopyrrolyl complexes in which Ar = 3,5-R2C6H3 (R = t-Bu or Me) and Ar′ = Mesityl

Diethylenetriamine could be arylated selectively as shown in equations 4 and 5.22,23 (3,5-Di-t-butylphenyl NHCH2CH2)2NH, a dark yellow oil, must be air-sensitive since minimizing exposure of the reaction to air during work-up significantly improves the yields. (3,5-dimethylphenyl NHCH2CH2)2NH does not appear to be as air-sensitive as (3,5-di-t-butylphenyl NHCH2CH2)2NH.

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

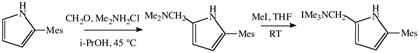

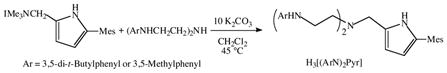

Mannich reactions analogous to those shown in equation 1 were not successful with the (ArNHCH2CH2)2NH species shown in equations 4 and 5. However, the approach shown in equations 6 and 7 was successful. The synthesis of H3[(Art-BuN)2Pyr] had to be carried out in the

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

absence of air. H3[(Art-BuN)2Pyr] could be obtained as a white powder after purification by column chromatography. H3[(ArMe N)2Pyr] does not appear to be as sensitive to air as H3[(Ar t-BuN)2Pyr] and no special precautions are necessary. H3[(ArMeN)2Pyr] was obtained as a pale yellow, viscous oil. We focussed on the synthesis and chemistry of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo complexes since we felt that the greater steric hindrance afforded by the t-butyl groups was the more desirable of the two alternatives. Unfortunately, although we could synthesize a diamidopyrrolyl ligand in which Ar = HIPT and Ar′ = 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl (Figure 2), which we believed would have the maximum chance of being sufficiently bulky to protect the metal (see Experimental Section), reactions analogous to those described for synthesizing [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]3− complexes described below led only to products that could not be isolated through crystallization.

Addition of H3[(Art-BuN)2Pyr] to Mo(NMe2)4 yielded teal blue, essentially diamagnetic [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) in 77% yield. Its diamagnetism is consistent with the S = 0 ground state that is a consequence of Mo-Namido π bonding. We propose that its structure is analogous to that shown in Figure 3 for the pentafluorophenyl analog. If we assume that the temperature dependent chemical shifts are a consequence of interconversion of high spin and low spin forms, then ΔH° is calculated to be 37(10) kJ mol−1, which is of the same magnitude as ΔH° for [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) (27(15) kJ mol−1). Therefore it appears that ΔH° is generally smaller in the triamidoamine systems ([TMSN3N]Mo(NMe2)19 and [C6F5N3N]Mo(NMe2)20) than in diamidopyrrolyl systems ([(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2) and [(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2)).

Addition of NaN(TMS)2 over a period of 30 minutes to a mixture of MoCl4(THF)2 and H3[(Art-BuN)2Pyr] in THF led to an orange-brown solution from which [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl could be isolated in moderate yield; a pure sample was isolated as a pink-tan powder after recrystallization of the crude product from a mixture of pentane and toluene. [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl is extremely sensitive to air and moisture and has paramagnetically shifted ligand resonances in its proton NMR spectrum; paramagnetically shifted resonances are features of all [ArylN3N]MoCl complexes.

The reaction between [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl and NaN3 in MeCN at room temperature results in a color change from orange-brown to dark purple followed by precipitation of a bright yellow solid. The reaction is completed upon heating the mixture to 80 °C, and bright yellow diamagnetic [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoN could be isolated in moderate yields. X-ray quality crystals of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoN were grown from fluorobenzene at −35 °C. The solid state structure (Figure 5) showed [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoN to be a TBP species analogous to the pentafluorophenyl derivatives reported above. The Mo(1)-N(1) bond length again is slightly longer than the Mo(1)-N(2) and Mo(1)-N(3) bond lengths. The Mo(1)-N(4) bond (2.4134(13) Å) is longer that in the pentafluorophenyl derivatives as a consequence of the the nitride ligand being in the apical position (Mo(1)-N(5) = 1.6746(13) Å).

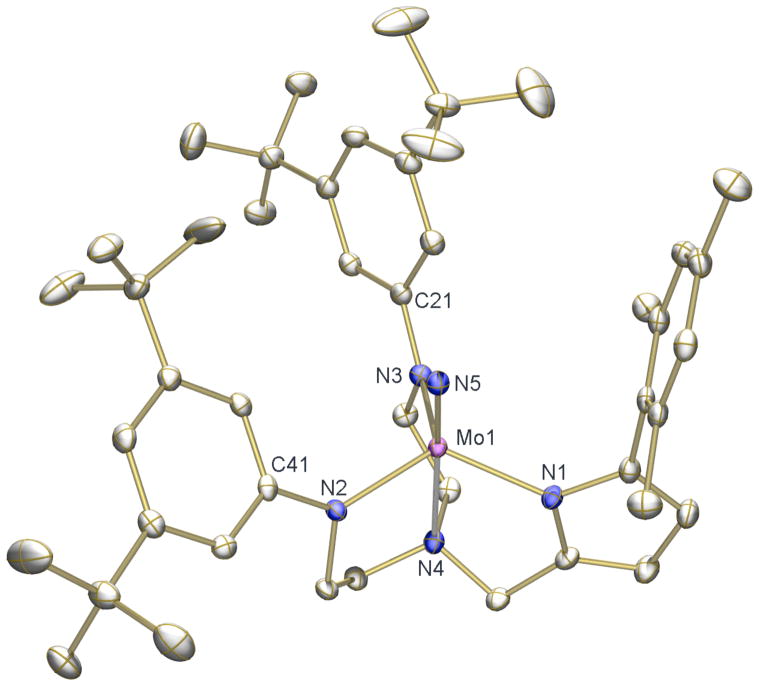

Figure 5.

Thermal ellipsoid drawing (50% probability) of the solid state structure of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2). H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (°): Mo(1)-N(5) = 1.6746(13), Mo(1)-N(4) = 2.4134(13), Mo(1)-N(1) = 2.0565(12), Mo(1)-N(2) = 1.9857(13), Mo(1)-N(3) = 1.9751(13), C(21)-N(2)-Mo(1) = 126.27(10), C(31)-N(3)-Mo(1) = 127.25(10), N(1)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 75.66(5), N(2)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 76.08(5), N(3)-Mo(1)-N(4) = 80.99(5), N(4)-Mo(1)-N(5) = 176.43(5).

Reduction of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl with 2.3 equivalents of Na under an N2 atmosphere in THF at room temperature produced a red solution from which a red solid could be isolated after removal of NaCl and unreacted Na. We propose that this extremely sensitive red solid is the diamagnetic diazenido anion, [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)Na(THF)x. IR spectra in C6D6 reveal two absorption bands in the expected region for a diazenido anion (1761 cm−1 and 1751 cm−1), but only a single absorption band is observed in THF (1766 cm−1). The presence of several diamagnetic species in the 1H NMR spectrum of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)Na(THF)x in C6D6 suggests that it is not pure. Attempts to purify the compound through recrystallization were not successful.

When impure {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x was treated with 1 equivalent of 15-crown-5 at −35 °C in diethyl ether, the orange-red solution immediately changed to green and a diamagnetic lilac-colored powder could be isolated from the mixture in ~20% yield. The lilac-colored compound exhibits a green color and a νNN absorption at 1855 cm−1 in THF, as is found for {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)}MgCl(THF)3 in THF.8b All data support formulation of the lilac-colored compound as {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(15-crown-5). When {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x 24 is exposed for several hours to a good vacuum, it turns from dark green to purple as a consequence of losing THF; the purple powder dissolves again in THF to yield green solutions. Therefore {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(15-crown-5) either loses 15-crown-5 from the sodium ion in THF or the green color in THF results from complete solvation of the salt in THF.

Reduction of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl with Na under an atmosphere of dinitrogen followed by addition of Bu4NCl directly to the reaction mixture yields {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}[NBu4] as a diamagnetic purple solid in ~60% yield. An IR spectrum of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}[NBu4] reveals a dinitrogen stretch at 1840 cm−1 in C6D6. Unfortunately, {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) }[NBu4] appears to be thermally unstable. It changes color over a period of days in a sealed tube at room temperature and no samples sent for elemental analyses yielded satisfactory results. We noted in studies of tungsten [HIPTN3N]3− complexes that {[HIPTN3N]W(N2)}[Bu4N] was thermally unstable, although other derivatives (e.g., a potassium salt) could be isolated and characterized. We proposed that the anionic dinitrogen complex is a powerful enough base to react with the tetrabutylammonium cation in the solid state.

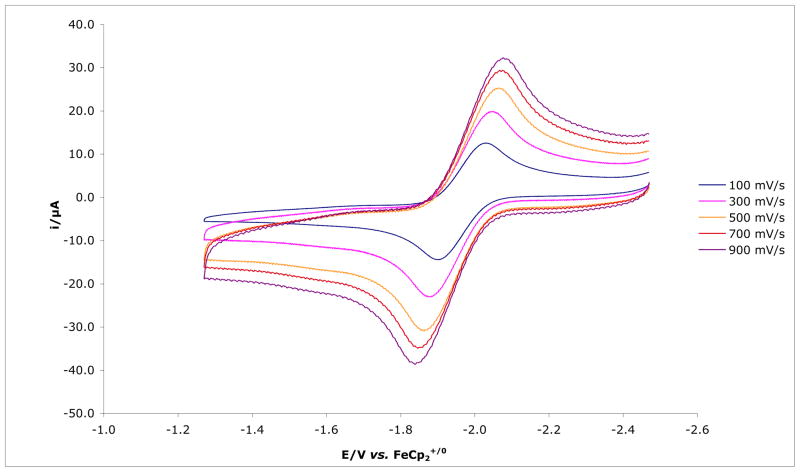

{[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}[NBu4] can be oxidized reversibly at −1.96 V in 0.1 M [NBu4]BAr′4 in PhF as shown in Figure 6. This result should be compared to observation of the reversible [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)0/− redox couple at −2.11 V under similar conditions (0.1M [NBu4]BAr′4 in PhF versus Cp2Fe+/0).8 However, oxidation of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) (anodic peak at ~ −0.65 V) is not reversible. A reversible [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)0/+ couple was observed in PhF, but not in THF as a consequence of rapid displacement of N2 by THF in the cationic species.9b The irreversibility of the [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)0/+ couple suggests that dinitrogen is lost more readily in {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}+ than in {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)}+.

Figure 6.

Electrochemical behavior of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}(n-Bu)4N in 0.1M [NBu4]BAr′4 in PhF recorded at a glassy carbon electrode at 100mV/s to 900mV/s scan rates, referenced to Cp2Fe+/0.

Oxidation of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x with AgOTf in the dark yielded paramagnetic, red [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) in 53% yield. The value of νNN in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) (2012 cm−1 in C6D6) should be compared with νNN in [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) (1990 cm−1 in C6D6), a difference of 22 cm−1.8b A higher νNN value in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) is consistent with slightly weaker backbonding into the dinitrogen ligand in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) than in [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2).

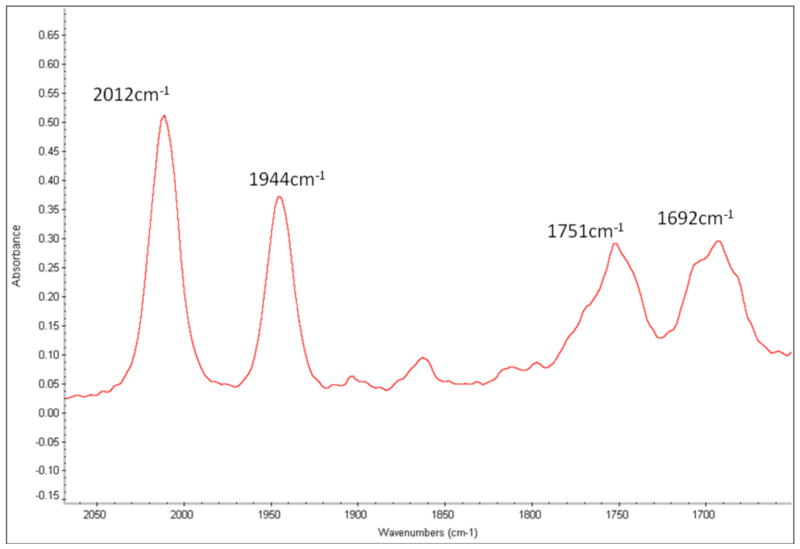

A mixture of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x and [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) in C6D6 was freeze-pump-thaw degassed and exposed to an atmosphere of 15N2. After 2.5 h an IR spectrum of the solution revealed that approximately half the [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) had been converted into [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(15N2) (1944 cm−1) and half the {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x (1751 cm−1) had been converted into {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo15N2}Na(THF)x (1692 cm−1; see Figure 7). These results suggest that the exchange of dinitrogen in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) is much faster than it is in [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2), where t1/2 for exchange is approximately 35 hours at 22 °C.8e We propose that formation of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(15N2)}Na(THF)x from {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x is a consequence of electron transfer between neutral and anionic species, rather than exchange directly in the anion. This circumstance is analogous to that observed in the parent system where 14N2/15N2 exchange in {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) }[NBu4] is extremely slow, and any exchange that is observed can be attributed to oxidation of a small amount of the anion to [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) and fast electron exchange between [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) with {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) }[NBu4].8b

Figure 7.

IR spectrum of a C6D6 solution of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) and {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x after exposure to 15N2 for 2.5 h.

A plot of ln(A15N/Atotal) for the dinitrogen exchange reaction in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(15N2) under N2 in C6D6 in a nitrogen-filled glovebox at 22 °C showed that the reaction is first order in [Mo] with kobs = 1.97 × 10−4 s−1 (t½ ~ 1 hour). When the pressure of N2 was increased to two atmospheres (15 psi overpressure), t1/2 for the exchange reaction decreased to ~ 30 minutes. Although the exchange rate depends on N2 pressure, that dependence alone does not distinguish between an associative reaction to give a six-coordinate bisdinitrogen intermediate, and rapid reversible loss of dinitrogen from [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) followed by capture of the hypothetical “naked” monopyramidal species, [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo, by dinitrogen. (See Discussion Section.)

When a PhF solution of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl in the presence of NaBPh4 is exposed to an atmosphere of NH3 (dried over Na), a rapid color change is observed from orange-red to burgundy and paramagnetic, yellow {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4 could be isolated in 32% yield. This compound is relatively insoluble in toluene. Similar experiments employing NaBAr′4 led to formation of what we propose is the analogous BAr′4− salt, but we were not able to isolate this salt from pentane, toluene, CH2Cl2, or THF.

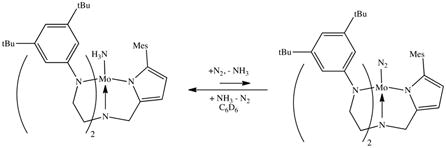

Reduction of a THF solution of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4 under an Ar atmosphere with CoCp*2 led to a color change from yellow-brown to green with concomitant formation of yellow [CoCp*2]BPh4. THF was removed in vacuo from the emerald green solution and the resulting solid was redissolved in C6D6 and exposed to 1 atm of N2. The color changed from green to red over the course of a day and IR spectroscopy of the mixture showed that [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) (νNN = 2012 cm−1) had formed.

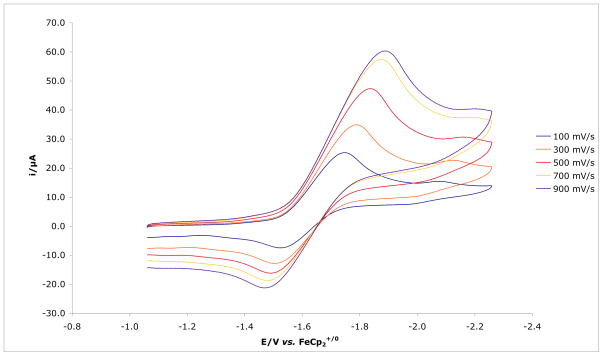

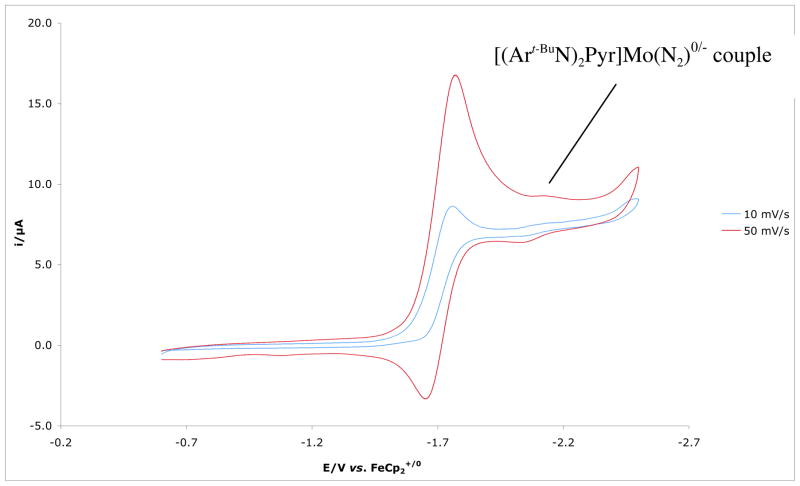

The reduction of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4 under Ar at approximately −1.68 V at a scan rate of 900 mV/sec is not reversible (Figure 8), in contrast to the reduction of {[HIPTN3N]Mo(NH3)}+, which takes place at −1.63 V and is fully reversible in both PhF and THF. We propose that ammonia is lost from [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3) upon reduction of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}+ even in fluorobenzene. However, when reduction of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4 was carried out under dinitrogen at progressively slower scan rates (10 and 50 mV/sec), the {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}0/− redox couple could be observed (Figure 9), thus confirming that dinitrogen replaces ammonia in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3). The {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)}0/− redox couple is also observed during the electrochemical reduction of {[HIPTN3N]Mo(NH3)}+.8c

Figure 8.

Electrochemical behavior of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4 in 0.1M [NBu4]BAr′4 in PhF recorded at a glassy carbon electrode, referenced to Cp2Fe+/0.

Figure 9.

Appearance of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4 at scan rates of 10 and 50 mV/sec.

Reduction of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4 in THF by CoCp*2 under an Ar atmosphere was followed by removing the THF in vacuo, dissolving the reaction product in C6D6, and exposing the solution to 1 atm of dinitrogen. Formation of ~30% of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) is observed after ~5 h. However, if 10 equivalents of BPh3 are present to trap the ammonia that is released, the exchange is virtually complete in about 2 h. Therefore we propose that the equilibrium in equation 8 lies to the left, as it does in the analogous [HIPTN3N]3− system. Qualitatively, the equilibrium in the [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]3− system appears to lie further to the left than in the [HIPTN3N]3− system, consistent with slightly weaker binding of dinitrogen to the metal in the [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]3− system and/or a slightly stronger binding of ammonia, or both.

|

(8) |

Exposure of a solution of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) to an atmosphere of CO led to a color change from red to brown. Brown [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(CO) could be isolated in 27% yield. [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(CO) is paramagnetic with a νCO absorption at 1902 cm−1; an analogous experiment under 13CO yielded [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(13CO) (ν13CO = 1856 cm−1). It is of utmost importance that the CO employed be free of impurities such as water and oxygen in order to avoid formation of unknown products with several CO absorption bands in the IR spectrum.

Reaction of a 1:1 mixture of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(CO) and [HIPTN3N]Mo(CO) in DME with one equivalent of [Collidinium]BAr′4 showed that the CO absorption for [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(CO) (1896 cm−1 in DME) disappeared and an absorption for the protonated form is observed at 1920 cm−1 (Δ = 24 cm−1). Addition of a second equivalent led to protonation of ~50% of the remaining [HIPTN3N]Mo(CO) (1885 → 1932 cm−1, Δ = 47 cm−1). We conclude that [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(CO) is protonated more readily than [HIPTN3N]Mo(CO) and that the shift in νCO to higher energy in {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(CO)(H)}+ is about half what it is in {[HIPTN3N]Mo(CO)(H)}+. Protonation of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(13CO) results in a similar shift in ν13CO (1853 → 1875 cm−1, Δ = 22 cm−1).

Protonation of [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) is known to lead to loss of intensity of the νNN stretch at 1990 cm−1 and observation of another at 2057 cm−1 for {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)(H)}+ (Δ = 67 cm−1). A similar side by side comparison of protonation of a mixture of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) and [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) with [Collidinium]BAr′4 in PhF revealed that [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) was again protonated more readily than [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2). Upon addition of two equivalents of [Collidinium]BAr′4 in PhF all [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) (νNN = 2012 cm−1) had disappeared, while most (~70%) of the [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) (νNN = 1990 cm−1) remained. In a separate experiment involving [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) in PhF, no νNN absorption for {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)(H)}+ could be observed. On the basis of the relative shifts in the CO complexes above (~0.5) we might expect to see νNN upon protonation of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) to shift by 0.5×67 cm−1 to ~2045 cm−1. Either dinitrogen is lost from {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)(H)}+ more readily than from {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)(H)}+ or {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)(H)}+ decomposes in some other manner. The site of protonation in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(CO) and [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) are assumed to be the same, but whether the site of protonation is the amido nitrogen or the pyrrolide is not known. However, we can say with certainty that {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)(H)}+ is formed more readily than {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)(H)}+, but {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)(H)}+ is less stable, not more stable, than {[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)(H)}+.

Attempts to reduce dinitrogen catalytically were carried out with [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N) as a “catalyst” in a manner similar to that utilized for [HIPTN3N]Mo derivatives, including [HIPTN3N]MoN.8e,f The amount of NH3 produced was then quantified using the indophenol method.25 In three catalytic runs an average of 1.02 ± 0.12 equivalents of NH3 were produced. It is clear that the nitride is reduced to ammonia but within experimental error we must conclude that the reaction does not turn over under the conditions employed.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The results that we have presented suggest that in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo compounds the metal is slightly less electron rich than in an analogous [HIPTN3N]Mo complex. Perhaps the best measure is a value of 2012 cm−1 for νNN in [(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]Mo(N2) in C6D6 versus 1990 cm−1 in [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) in C6D6. Only two Mo-Namido π bonds can form in [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2), since the combination of p orbitals on the amido nitrogens that has A2 symmetry in C3v point group is ligand-centered and nonbonding. Since the pyrrolyl lone pair is part of the six π electron aromatic system in the pyrrolide, the pyrrolyl ligand has little ability to π bond to the metal through the pyrrolyl nitrogen and therefore only two MoNamido π interactions can form in a [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]3− complex also. The [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]3− and [HIPTN3N]3− systems turn out to be similar electronically, at least in terms of the degree of activation of dinitrogen.

An important question is whether the reduced π backbonding ability of the metal in a [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo complex itself is enough to doom catalytic reduction of dinitrogen. One important step is the exchange of ammonia in the Mo(III) complex with dinitrogen. We have shown (Figure 9) that the {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}0/− redox couple can be observed upon reduction of {[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}+, thereby verifying that [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3) is converted readily into [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2). However, evidence suggests that the position of the equilibrium between [(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]Mo(NH3) and [(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]Mo(N2) does not lie as far toward the dinitrogen complex as it does in the [HIPTN3N]Mo system, a finding that is consistent with the slightly poorer backbonding ability of the metal in the [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo system. On the whole, it seems that poorer backbonding ability alone is not the primary problem.

More problematic in terms of catalytic reduction, we propose, is the apparent instability of [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo-N=NH. All efforts to prepare or even observe [(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]Mo-N=NH in solution have failed so far. That instability may not be surprising, since in triamidoamine systems where dinitrogen is not reduced catalytically, the Mo-N=NH species either is not observable or it is decomposed catalytically in the presence of the conjugate base (e.g., 2,6-lutidine) that builds up after delivery of a proton.9b,c In contrast, [HIPTN3N]Mo-N=NH is relatively stable, as is the Mo-N=NH species in the analogous (catalytically inactive) hexa-t-butylterphenyl system.9 In general, Mo-N=NH species in more “open” ligand systems appear to be compromised in some as yet unknown manner.9c

Some measure of the steric hindrance in [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) and similar species is the ease of exchanging dinitrogen. In [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) the exchange of dinitrogen takes place with a first-order rate constant of 6 × 10−6 s−1 and a t1/2 of approximately 35 hours.8b In the even more sterically hindered [HTBTN3N]Mo system (where HTBT is hexa-t-butylterphenyl), the exchange of [HTBTN3N]Mo(15N2) under 14N2 has a t1/2 of ~750 hours (k ~ 3 × 10−7s−1).9 The values for νNN in the two systems are the same, so the metal-N2 bond strengths are the same. In [HTBTN3N]Mo(N2) it is proposed that the steric bulk provided by the t-Bu substituents slows down loss of N2 from the apical site compared to its rate of loss in [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2). The rate constant of the exchange in both [HIPTN3N]Mo and [HTBTN3N]Mo systems changes little with the pressure of 14N2 (in the range of one to several atmospheres). Although the Mo-N2 bond strength (enthalpy) in [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) is calculated to be 37.8 kcal mol−1,14 inclusion of the entropy term brings down the value for the free energy difference down to as little as half that.13 Therefore the naked species cannot be discounted as an intermediate on the basis of either experimental data or calculations. The pressure dependence of the dinitrogen exchange [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(14N2) is proposed to arise through an associative mechanism involving a six-coordinate transition state, a transition state made possible as a consequence of a decrease in steric hindrance around the metal center.

It is unfortunate that complexes that contain a diamidopyrrolyl ligand in which Ar is HIPT and Ar′ is 2,4,6-i-Pr3C6H2 (Figure 2) proved too soluble to isolate. It still seems possible that catalytic turnover could be observed in the right steric circumstances. Whether such a diamidopyrrolyl ligand could produce a more efficient catalyst of course is unknown.

Experimental Section

General

All air and moisture sensitive compounds were handled under N2 atmosphere using standard Schlenk and glove-box techniques, with flame or oven-dried glassware. Ether, pentane and toluene were purged with nitrogen and passed through activated alumina columns. Dichloromethane was distilled from a CaH2 suspension. Pentane was freeze-pump-thaw degassed three times and tetrahydrofuran (THF), benzene, tetramethylsilane, benzene-d6, THF-d4 and toluene-d8 were distilled from dark purple Na/benzophenone ketyl solutions. Ether and dichloromethane were stored over molecular sieves in solvent bottles in a nitrogen-filled glovebox while pentane, THF, PhF, benzene, benzene-d6, THF-d4 and toluene-d8 were stored in Teflon-sealed solvent bulbs. Molecular sieves (4 Å) and Celite were activated at 230 °C in vacuo over several days. (Me3Si)2NLi (Strem) was sublimed, while (Me3Si)2NNa (Aldrich) was recrystallized from THF. [ZnCl2(dioxane)]x was prepared by dissolution in diethyl ether and adding 1 equivalent of 1,4-dioxane to give. MoCl5 (Strem) was used as obtained, unless indicated otherwise. MoCl4(THF)2,26 Mo(NMe2)4,272-mesityl-1H-pyrrole3 were synthesized as referenced. 1-Bromo-3,5-dimethylbenzene and 1-bromo-3,5-di-tert-butylbenzene were obtained from Sigma Aldrich; 1-bromo-3,5-di-tert-butylbenzene also was synthesized as reported in the literature.28,29,30 IR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet Avatar 360 FT-IR spectrometer in 0.2 mm KBr solution cells. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury or Varian Inova spectrometer operating at 300 or 500 MHz (1H), respectively. 1H and 13C NMR spectra are referenced to the residual 1H or 13C peaks of the solvent. 19F NMR spectra were referenced externally to fluorobenzene (−113.15 ppm upfield of CFCl3). HRMS was performed on a Bruker Daltonics APEXIV 4.7 Tesla Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometer at the MIT Department of Chemistry Instrumentation Facility. Combustion analyses were performed by Midwest Microlabs, Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S.

H3[(C6F5N)2Pyr]

A 40 mL scintillation vial equipped with a stirbar was charged with N1-(perfluorophenyl)-N2-(2-(perfluorophenylamino)ethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine (1.918 g, 4.4 mmol). To formaldehyde (35% wt, 0.372 mL) was added HCl (5 μL of 12N). THF (1 mL) was added to the formaldehyde mixture, which was then transferred to the 40 mL scintillation vial. To the vial was added THF (2 mL) and isopropanol (2 mL). The mixture was stirred for 20 minutes and the reaction mixture added to a vial charged with 2-mesitylpyrrole (0.807 g, 4.4 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16 hours, then washed with 10% KOH solution (40 mL), and extracted with diethyl ether. The extract was dried over Na2SO4, the volatiles were removed in vacuo, and the residue was purified by column chromatography using 9: 1 hexanes: ethyl acetate as the eluent. The desired product is the second product from the column, with an Rf value of 0.158; yield 0.1545 g (55%): 1H NMR (500 MHz CDCl3) δ 7.97 (s, 1H, pyrrole NH), 6.92 (s, 2H, Mes 3,5-H), 6.13 (t, 1H, pyrrole -CH), 5.96 (t, 1H, pyrrole -CH), 4.08 (s, 2H, amine NH), 3.72 (s, 2H, C-CH2-N), 3.35 (q, 4H, C6F5NHCH2), 2.78 (q, 4H, C6F5NHCH2CH2), 2.32 (s, 3H, Mes 4-CH3), 2.09 (s, 6H, Mes 2,6 –CH3); 13C NMR (126 MHz CDCl3): δ 139.2, 138.2, 137.8, 137.2, 134.7, 132.7, 130.3, 129.8, 128.3, 127.0, 124.0, 108.9, 108.7, 53.9, 51.8, 43.8, 21.2, 20.6 19F NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3): δ −159.8 (d, JFF = 20.0 Hz, 2,6 -F), −164.1 (t, JFF = 21.2 Hz, 3,5 -F), −171.3 (tt, JFF = 5.3, 21.9 Hz, 4 -F) HRMS (ESI m/z): Calcd for C30H27F10N4+ 633.207, found 633.2056

[(C6F5N)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2)

Under a N2 atmosphere, a 20 mL scintillation vial was charged with Mo(NMe2)4 (671.8 mg, 2.468 mmol) and [Mes(C6F5)2]H3 (1.338 g, 2.115 mmol) and toluene (15 mL). The reaction mixture rapidly turned dark blue (from deep purple) and eventually became emerald green. It was stirred for approximately 48 hours at room temperature, with the vial periodically uncapped to facilitate loss of HNMe2. The solvent was decreased to approximately 5 mL, and pentane (approximately 2 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was then left at −35 °C overnight and the product collected on a glass frit as a dark green solid; yield 1.347 g (83%): 1H NMR (toluene-d8) δ 6.77 (s, 2H, mesityl 3,5-H), 6.11 (d, 1H, pyrrole -H), 6.02 (d, 1H, pyrrole, -H), 3.76 (s, 2H, -NCH2), 3.72 (quintet, 2H, -C6F5NCH(H)), 3.23 (quintet, 2H, -C6F5NCH(H)), 2.97 (quintet, 2H, C6F5NCH2CH(H)), 2.63 (quintet, 2H, -C6F5NCH2CH(H)), 2.55 (s, 6H, -N(CH3)2), 2.17 (s, 3H, mesityl 4-CH3), 2.04 (s, 6H, mesityl 2,6-CH3); 13C NMR (toluene-d8): δ 143.6, 139.7, 137.2, 136.9, 135.2, 129.6, 128.9, 128.8, 128.6 125.8, 113.2, 105.7, 66.2, 61.2, 55.9, 55.1, 21.6, 21.5; 19F NMR (toluene-d8) δ −148.0 (d), −162.8 (t), −164.7 (t). Anal. Calcd for C32H29F10MoN5: C, 49.95; H, 3.80; N, 9.10. Found: C, 49.67; H, 3.90; N, 9.22.

[(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoCl

Under a N2 atmosphere, a 20 mL scintillation vial equipped with a stir bar was charged with MoCl4(THF)2 (1.191g, 3.092 mmol), [Mes(C6F5)2]H3 (2000 mg, 3.162 mmol), and THF (5 mL). The reaction mixture turned from an orange suspension to an orange-red solution. The mixture was stirred for 30 minutes and LiNTMS2 (1.587 g, 9.484 mmol) was added, which led to a darkening of the mixture to magenta. After stirring the mixture for another 30 minutes, the volatiles were removed in vacuo, the mixture extracted with toluene, and the extract was filtered through Celite. The product was recrystallized from toluene and pentane at −35 °C and collected on a glass frit; yield 0.989 g (42%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 41.03 (s), 12.38 (s), 8.31 (s), 6.84 (s), 6.02 (s), 5.23 (s), 4.34–2.91 (m), 2.12 (s), 1.80 (s), 1.27 (s), 0.88 (s), 0.30 (s), 0.01 (s), −1.21(s), −20.04 (s), −78.50 (s), −92.10 (s); 19F NMR (C6D6) δ −71.02 (s), −96.37 (s), −121.893 (s), −122.80 (s), −148.27 (s). HRMS (ESI m/z): Calcd for C30H23F10N4MoClNa+: 785.0405, found 785.0412.

[(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoOTf

Under a N2 atmosphere, a scintillation vial was charged with [Mes(C6F5)2]MoCl (100 mg, 0.131 mmol), AgOTf (33.6 mg, 0.131 mmol) and CH2Cl2 (5 mL). The mixture was stirred overnight at RT and then filtered through Celite. All volatiles were removed in vacuo. The orange-red product was recrystallized from a mixture of toluene, pentane and CH2Cl2; yield 47.5 mg (42%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 39.86 (s), 14.85 (s), 12.07 (s), 7.12 (s), 7.06 (s), 7.05 (s), 7.01 (s), 6.35 (s), 4.72 (br s), 2.06 (s), 1.30 −1.24 (m), −21.47 (s), −85.28 (br s), −108.85 (br s). Anal. Calcd for C31H23F13MoN4O3S: C, 42.58; H, 2.65; N, 6.41. Found: C, 42.40; H, 2.79; N, 6.25.

[(C6F5N)2Pyr]MoN

Under a N2 atmosphere, a 25 mL solvent bulb was charged with [(C6F5N)2Pyr ]MoCl (200 mg, 0.263 mmol), NaN3 (13.6 mg, 0.118 mmol), and acetonitrile (5 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at 70 °C for 72 hours. The volatiles were removed in vacuo and the residue was extracted with toluene and filtered through Celite. Diamagnetic yellow-brown needle-like crystals were deposited after standing the filtrate at −35 °C overnight and collected on a glass frit; yield 103 mg (53%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 6.86 (s, 2H, mesityl 3,5-H), 6.25 (d, 1H, pyrrole H), 6.20 (d, 1H, pyrrole H), 3.35 (s, 2H, NCH2), 3.25 (quintet, 2H, (NCH(H)CH2)3N), 3.04 (quintet, 2H, (NCH(H)CH2)3N), 2.48 (s, mesityl 2,6-CH3), 2.25 (quintet, 2H, (NCH2CH(H))3N), 2.18 (quintet, 2H, (NCH2CH(H))3N), 1.92 (s, 3H, mesityl 4-CH3); 13C NMR (C6D6) δ 142.8, 142.5, 140.9, 139.9, 139.0, 139.0 (overlapping), 137.9, 137.8, 137.2, 136.9, 135.1, 133.6, 128.4, 128.1, 111.2, 108.3, 58.3, 51.3, 51.0, 21.1, 21.0, 21.0; 19F NMR (C6D6) δ −150.18 (dd, 1F), −150.40 (t, 1F), −159.44 (t, 1F), −163.63 (d, 1F), −163.60 (d, 1F, overlapping). Anal. Calcd for C30H23F10MoN5: C, 48.73; H, 3.14; N, 9.47. Found: C, 48.51; H, 3.28; N, 9.48.

(3,5-t-Bu2C6H3NCH2CH2)2NH

Under a N2 atmosphere, a 1 L Schlenk flask was charged with 3,5-di-tert-butylbromobenzene (20.78g, 77.2 mmol), CuI (0.646 g, 3.6 mmol), N,N-diethylsalicylamide (2.82 g, 14.6 mmol), K3PO4 (30.54 g, 143.9 mmol), and a magnetic stirbar. DMF (70mL) was added and the resulting suspension was stirred for 30–45 minutes. Diethylene triamine (3.71g, 36.0mmol) was added and washed in with DMF (30mL). The reaction flask was then heated to 90°C for 36h with stirring. The initially blue-green mixture turns brown with concomitant formation of reddish Cu powder as the mixture is heated after approximately 2 hours. The mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, then aqueous NH3 (100mL) and H2O (300mL) were added with stirring. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (4×200mL) and the organic layers dried over Na2SO4. The product was purified via column chromatography first eluting with 4:1 Hexanes: Ethyl acetate and then subsequently with diethyl ether. Care was taken to limit exposure of the product to O2. The product was obtained as a yellow oil; yield 12.44g (72%): 1H NMR (C6D6) 7.022 (2H, s, Aryl 4-H), 6.589 (4H, s, Aryl 2,6-H), 3.776 (2H, ArNH), 2.986 (4H, t, ArNHCH2), 2.509 (4H, t, ArNHCH2CH2), 1.374 (36H, s, -C(CH3)3) HRMS (ESI, m/z): Cald for C32H54N3+: 480.4312, found 480.4294.

(3,5-Me2C6H3NCH2CH2)2NH

A 300mL Schlenk flask was charged with CuI (0.4507g, 2.4mmol), N,N-diethylsalicylamide (1.826g, 9.5mmol), K3PO4 (20.07g, 94.5mmol) and DMF (50mL). The mixture was stirred for 30 minutes. 1-Bromo-3,5-dimethylbenzene (10.0g, 54.4mmol) was added and the the mixture was stirred for 5 minutes before subsequent addition of diethylene triamine (2.44g, 23.6mmol) was added and washed in with DMF (30mL). The reaction flask was then heated to 90 °C for 96h with stirring. The initially blue-green mixture turns brown with concomitant formation of reddish Cu powder as the mixture is heated after approximately 2 hours. The mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, then aqueous NH3 (100mL) and water (200mL) were added with stirring. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (4× 200mL) and the organic layers dried over Na2SO4. The product was purified via column chromatography first eluting with Et2O to remove impurities and then THF. The product was obtained as a brown-yellow oil; yield 7.200g (98%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 6.442 (2H, s, xylyl 4-H), 6.268 (4H, s, xylyl 2,6-H), 3.791 (2H, br s, ArNHCH2), 2.903 (4H, t, ArNHCH2), 2.448 (4H, t, ArNHCH2CH2). HRMS (ESI, m/z): Calcd for C20H30N3+: 312.2434, found 312.2442.

H3[(Art-Bu N)2Pyr]

Under N2 atmosphere, a 500mL Schlenk flask was charged with (3,5,-Me2C6H3NHCH2CH2)2NH (12.44g, 25.9mmol), 1-(5-mesityl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)-N,N-trimethylammonium iodide (2) (9.848g, 25.6mmol), K2CO3 (35.88g, 259.6mmol) and THF (250mL). The reaction was heated to 50°C for 72 hours, with the flask periodically vented to an atmosphere of N2. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, then filtered and extracted with Et2O. The volatiles were removed in vacuo and the resulting mixture purified via column chromatography using 4:1 hexanes: ethyl acetate as the eluent; yield 10.44g (60%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 7.325 (1H, s, pyrrole N-H), 7.009 (2H, t, JHH=1.7 Hz, Aryl 4-H), 6.834 (2H, s, mesityl 3,5-H), 6.596 (4H, d, JHH=1.7 Hz, Aryl 2,6-H), 6.214 (1H, dd (apparent triplet), pyrrole CH), 6.087 (1H, dd (apparent triplet), pyrrole CH), 3.867 (2H, s, ArylNH), 3.413 (2H, s, pyrroleCH2N), 3.041 (4H, t, JHH=5.8 Hz, ArylNHCH2), 2.498 (4H, t, JHH=5.8 Hz, ArylNHCH2CH2), 2.187, 2.181 (overlapping, 12H, s, mesityl 2,4,6-CH3), 1.285 (36H, s, Aryl 3,5-C(CH3)3). 13C NMR (C6D6): δ 152.18, 148.05, 138.70, 137.67, 131.784, 130.223, 128.827, 128.68, 128.29, 112.57, 109.39, 108.94, 108.45, 53.46, 52.33, 42.62, 35.35, 32.15, 21.52, 21.32. HRMS (ESI, m/z): Calcd for C46H67N4+: 677.5517, found 677.5504

H3[(ArMeN)2Pyr]

A 500mL flask was charged with (3,5,-Me2C6H3NHCH2CH2)2NH (7.20g, 23.1mmol), 2 (8.80g, 22.9mmol), Cs2CO3 (16.78g, 2.3mmol) and THF. The flask was stoppered with a cap equipped with a needle to prevent pressure build-up. The reaction mixture was stirred for 48h at 70°C. The volatiles were removed in vacuo, and the mixture extracted with Et2O and filtered. The volatiles were removed in vacuo, and the resulting oil purified via column chromatography (3:1 hexanes: ethyl acetate as eluent) to produce a viscous yellow oil; yield 4.181g (36%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 7.540 (1H, s, pyrrole NH), 6.823 (2H, s, Aryl 4-H), 6.393 (2H, s, mesityl 3,5-H), 6.227 (4H, s, Aryl 2,6-H), 6.201 (1H, t, JHH= 2.6 Hz, pyrrole-H), 6.081 (1H, t, JHH= 2.6 Hz, pyrrole-H), 3.691 (2H, s, ArylNH), 3.342 (2H, s, pyrroleCH2N), 2.864 (4H, t, JHH= 5.4 Hz, ArylNHCH2), 2.356 (4H, t, JHH= 5.4 Hz, ArylNHCH2CH2), 2.203 (12H, s, Aryl 3,5-CH3), 2.198 (3H, s, mesityl 4-CH3), 2.158 (6H, s, mesityl 2,6-CH3); 13C NMR (C6D6) δ 149.10, 138.83, 138.41, 137.22, 131.46, 129.94 (quaternary carbons, 1 carbon overlapping with C6D6); 128.48, 119.94, 111.43, 108.75, 108.53 (tertiary carbons), 52.96, 51.75, 41.88 (secondary carbons), 21.74, 21.20, 20.94 (primary carbons). HRMS (ESI, m/z): Calcd for C34H45N4+ 509.3639; found 509.3640.

N,N-dimethyl-1-(5-(2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl)-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methanamine

A 100 mL round bottom flask was charged with Me2NH2Cl (1.592 g, 19.52 mmol), formaldehyde (1.670 mL, 37% solution in water, 20.58 mmol), and isopropanol (10 mL). The mixture was stirred for approximately 30 minutes. 2-(2,4,6-Triisopropylphenyl)-1H-pyrrole (5.260 g, 19.52 mmol) was then added and the mixture was stirred for approximately 70 hours at 40 °C. 300 mL of 10% KOH solution was added and the mixture stirred for 30 minutes. Volatiles were removed in vacuo and 200 mL water was added. The mixture was extracted three times with CH2Cl2 (200 mL) and the organic layer was dried over Na2SO4. Volatiles were removed in vacuo and the residue used without further purification: yield 4.35g (68%): 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.206 (1H, s, pyrrole -NH), 7.037 (2H, s, aryl 3,5-H), 6.069 (1H, t, JHH = 3.0 Hz, pyrrole C-H), 5.953 (1H, t, JHH = 3.0 Hz, pyrrole C-H), 3.465 (2H, s, -CH2), 2.927 (1H, septet, JHH = 6.7 Hz, 4-CHMe2), 2.789 (2H, septet, JHH = 6.7 Hz, 2,6-CHMe2), 2.223 (6H, s, -N(CH3)2) ppm; 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 149.6, 149.1, 129.4, 128.7, 128.3, 120.6, 108.7, 108.3, 56.8, 45.0, 34.6, 30.7, 24.7, 24.3. ppm HRMS (ESI, m/z): Calcd for C22H33N2− 325.2659. Found 325.2650.

1-(5-(2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl)-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)-N,N-trimethylammonium iodide

A 250 mL round bottom flask was charged with 1-(5-(2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl)-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)-N,N-dimethylmethanamine (3.950 g, 12.098 mmol) and THF (150 mL). A vial with a septum sealed cap was charged with MeI (1.717 g, 12.098 mmol) and THF (15 mL). The contents of the vial were syringed out and added slowly to the stirring solution of 1-(5-(2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl)-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)-N,N-dimethylmethanamine. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 hour at RT, during which a very thick white suspension formed. The white precipitate was collected on a glass frit, washed with THF and recrystallized from acetone; yield 3.12 g (55%): 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 10.05 (1H, s, pyrrole -NH), 7.02 (2H, s, mesityl 3,5-H), 6.42 (1H, t, JHH = 2.9 Hz, pyrrole C-H), 6.01 (1H, t, JHH = 2.9 Hz, pyrrole C-H), 5.20 (2H, s, -CH2), 3.30 (9H, s, N(CH3)3), 2.92 (1H, septet, JHH = 6.6 Hz, 4-CHMe2), 2.60 (2H, septet, JHH = 6.6 Hz, 2,6-CHMe2), 1.30 (6H, d, JHH = 7.1 Hz, 4-CH(CH3)2), 1.15 (6H, d, JHH = 7.1 Hz, 2,6-CH(CH3)2), 1.12 (6H, d, JHH = 7.1 Hz, 2,6-CH(CH3)2) ppm; 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 149.6, 149.2, 133.6, 127.5, 120.8, 116.9, 114.8, 110.4, 62.4, 52.4, 34.5, 30.9, 25.1, 24.3, 24.2 ppm HRMS (ESI, m/z): Calcd for C23H37N2− 341.2951. Found 341.2937.

H3(HIPTN)2(TRIPpyr)

A 100 mL round bottom flask was charged with N1-HIPT-N2-(2-(HIPT)ethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine (1.194 g, 1.121 mmol), 1-(5-(2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl)-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)-N,N-trimethylammonium iodide (0.525 g, 1.121 mmol), and K2CO3 (1.2 g, 8.682 mmol). The flask was purged with N2, and the reaction mixture stirred overnight at RT under N2. The product was purified by column chromatography and eluted with 2:1 hexanes: ethyl acetate; yield 0.7893 g (52%): 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.87 (1H, s, pyrrole –NH), 7.01 (2H, s, TRIP aryl 3,5-H), 7.01 (8H, HIPT aryl 3,5,3″,5″-H), 6.39 (4H, d, HIPT aryl 2′,6′-H), 6.37 (2H, t, HIPT aryl 4′-H), 6.08 (1H, t, JHH = 2.9 Hz, pyrrole C-H), 5.96 (1H, t, JHH = 2.9 Hz, pyrrole C-H), 3.92 (2H, t, JHH = 5.1 Hz, NHCH2CH2), 3.75 (2H, s, NCH2C), 3.20 (4H, q, JHH = 5.8 Hz, NHCH2CH2N), 2.92 (4H, sept, JHH = 7.0 Hz, HIPT 4,4″-CHMe2), 2.91 (1H, sept, JHH = 7.0 Hz, TRIP 4-CHMe2), 2.81 (12H, sept, JHH = 6.9 Hz, HIPT 2,6,2″,6″ -CHMe2 overlapping with NHCH2CH2N), 2.73 (2H, sept, JHH = 6.9 Hz, TRIP 2,6-CHMe2), 1.29 (28H, d, JHH = 6.7 Hz, HIPT 4,4″-CH(CH3)2, TRIP 4-CH(CH3)2), 1.12 (24H, d, JHH = 6.7 Hz, HIPT 2,6,2″,6″-CH(CH3)2), 1.08 (12H, d, JHH = 6.7 Hz, TRIP 2,6-CH(CH3)2), 1.04 (24H, d, JHH = 6.7 Hz, HIPT 2,6,2″,6″-CH(CH3)2) ppm; 13C NMR (126 MHz CDCl3) δ 149.5, 147.6, 147.3, 146.5, 141.6, 137.5, 129.0, 128.8, 126.9, 121.5, 120.7, 120.5, 112.5, 109.2, 108.4, 52.7, 51.1, 41.6, 34.6, 30.8, 30.4, 24.7, 24.4, 24.3, 24.2 ppm. HRMS (ESI, m/z) cald for C96H137N4+: 1347.0917, found 1347.0863.

[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NMe2)

In a N2 atmosphere glovebox, a 25mL solvent bulb equipped with a PTFE screw valve was charged with H3[(Art-BuN)2Pyr] (635mg, 0.938mmol) and Mo(NMe2)4 (313mg, 1.15mmol) and toluene. The reaction mixture turned from purple to ultramarine blue within a couple of hours, but was left to stir at room temperature overnight. The mixture was brought back into the glovebox and volatiles were removed in vacuo. The desired product was purified via recrystallization from pentane/toluene at −35°C giving a bright teal blue diamagnetic powder; yield 588mg (77.0%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 7.178 (2H, s, Aryl 4-H), 6.938 (2H, s, mesityl 3,5-H), 6.553 (4H, s, Aryl 2,6-H), 6.283 (1H, d, JHH= 2.8 Hz, pyrrole CH), 6.266 (1H, d, JHH = 2.8 Hz, pyrrole CH), 3.963 (2H, dt, ArNCH2CH2), 3.828 (2H, s, pyrroleCH2N), 3.813 (2H, dt, ArNCH2CH2), 3.200 (2H, dt, ArNCH2CH2), 3.006 (6H, s, MoN(CH3)2), 2.749 (2H, dt, ArNCH2CH2), 2.261 (6H, s, mesityl 2,6-CH3), 2.239 (3H, s, mesityl 4-CH3), 1.288 (36H, s, Aryl 3,5-C(CH3)3). Anal. Calcd for C48H71N5Mo: C, 70.82; H, 8.79; N, 8.60. Found: C, 70.47; H, 8.41; N, 8.46.

[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl

In a N2 atmosphere glovebox, a 20mL scintillation vial was charged with H3[(Art-BuN)2Pyr] (890mg, 1.3mmol) and THF (10mL). The solution was stirred for 5 minutes to ensure complete dissolution of the ligand. MoCl4(THF)2 (515.6mg, 1.4mmol) was added very slowly with stirring over the course of 30 minutes. The resulting dark brown solution was stirred for 40 minutes at room temperature. NaN(TMS)2 (770.2mg, 4.2mmol) was added slowly over 15 minutes to the mixture, which turned from brown to dark brownish orange. The mixture was stirred for 30 minutes and the volatiles were removed in vacuo. The residue was extracted with toluene and the extract was filtered through Celite. The toluene was removed in vacuo and the mixture triturated with pentane and cooled to −35°C overnight. The desired product was collected on a glass frit as a paramagnetic pink-tan powder; yield 0.564g (53%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 18.78 (s), 11.71 (br s), 8.20 (s), 5.94 (s), 5.20 (s), 5.10 (s, overlapping), 2.56 (s), 1.82 (36H, s, Aryl 3,5 –C(CH3)3), −24.56 (br s), −83.71 (br s), −115.23 (br s). Anal. Calcd for C46H65N4MoCl: C, 68.60; H, 8.13; N, 6.96. Found: C, 68.62; H, 8.01; N, 6.86.

[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoN

In a N2 atmosphere glovebox, a 25mL solvent bulb equipped with a PTFE screw valve was charged with [(ArMeN)2Pyr]MoCl (100mg, 0.12mmol), NaN3 (8.1mg, 0.12mmol), and MeCN (10mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10h, turning from orange brown to purple overnight, with formation of a yellow precipitate. The reactoion flask was then brought out of the glovebox and heated at 80°C for 24h. The flask was brought back into the glovebox, the volatiles removed in vacuo and the residue extracted with toluene and filtered through Celite. The volume of the filtrate was decreased to 5mL and cooled to −35°C overnight. The resulting yellow precipitate as collected on a glass frit and washed with cold pentane. The product obtained is a bright yellow diamagnetic powder; yield 45mg (46.2%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 7.454 (4H, d, JHH = 1.7 Hz, Aryl 2,6-H), 7.262 (2H, t, JHH = 1.7 Hz, Aryl 4-H), 6.913 (2H, s, mesityl 3,5-H), 6.345 (2H, s, pyrrole-H), 3.594 (2H, dt, ArylNCH2CH2), 3.561 (2H, dt, ArylNCH2CH2), 3.531 (2H, s, pyrroleCH2N), 2.437 (6H, s, mesityl 2,6-CH3), 2.338 (2H, dt, ArylNCH2CH2), 2.278 (3H, s, mesityl 4-CH3), 2.261 (2H, dt, ArylNCH2CH2), 1.318 (36H, s, Aryl 3,5-C(CH3)3). Anal. Calcd for C46H65N5Mo: C, 70.47; H, 8.36; N, 8.93. Found: C, 70.47; H, 8.44; N, 9.02.

{[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(15-crown-5)

In a N2 atmosphere glovebox, a 20mL scintillation vial was charged with {[(3,5-t-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x (150 mg, ~ 0.15 mmol) and Et2O (5mL). A separate vial was charged with 15-crown-5 ether (33 mg, 0.15 mmol) and Et2O (5mL). Both vials were chilled at −35°C for 1h, then the solution of the crown ether was slowly added with stirring to the diazenide solution. An immediate color change is observed, from orange-red to green. The diamagnetic lilac solid was recrystallized from THF at −35°C; yield 28.5mg (20%): 1H NMR (THF-d8) δ 7.303 (4H, s, Aryl 2,6-H), 6.927 (2H, s, Aryl 4-H), 6.627 (2H, s, mesityl 3,5-H), 5.983 (1H, d, JHH=3.0 Hz, pyrrole-CH), 5.852 (1H, d, JHH=3.0 Hz, pyrrole-CH), 3.926 (2H, dt, ArylNCH2CH2N), 3.861 (2H, dt, ArylNCH2CH2N), 3.603 (2H, dt, overlapping with solvent peak, ArylNCH2CH2N), 3.482 (2H, s, overlapping with 15-c-5 1H peak, pyrrolylCH2N), 3.409 (20H, s, 15-crown-5 -OCH2CH2O-), 2.497 (2H, t, JHH=5.7 Hz, ArylNCH2CH2N), 2.174 (3H, s, mesityl 4-CH3), 2.126 (6H, s, mesityl 2,6-CH3), 1.230 (36H, s, Aryl 3,5-C(CH3)3). IR (THF) νNN 1855cm−1. Anal. Calcd for C56H85N6MoNaO5: C, 64.60; H, 8.23; N, 8.07. Found: C, 64.59; H, 8.10; N, 7.98.

{[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)}(n-Bu)4N

In a N2 atmosphere glovebox, a 20 mL scintillation vial was charged with 5a (700mg, 0.87mmol), Na (45.9mg, 2.00mmol), and THF (10mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12h at RT with a glass stirbar, with a concomitant color change from orange red to dark purple to red. The mixture as filtered through Celite and NBu4Cl (TBACl) (252.9mg, 1.04mmol) was added. The mixture turned orange, then dark green after stirring for 40h at RT. Volatiles were removed in vacuo, then the residue was extracted with toluene and filtered through Celite. The filtrate was decreased in vacuo, with a color change from green to purple. The solution was chilled at −35°C overnight and the resulting diamagnetic lavender powder was collected on a glass frit; yield 550mg (61%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 7.331 (4H, s, Aryl 2,6-H), 7.057 (2H, s, mesityl 3,5-H), 6.962 (2H, s, Aryl 4-H), 6.771 (1H, d, JHH= 2.9 Hz, pyrrole-H), 6.735 (1H, d, JHH= 2.9 Hz, pyrrole-H), 4.018 (2H, dt, ArylNHCH2CH2), 3.849 (2H, dt, ArylNHCH2CH2), 3.481 (2H, s, pyrroleCH2N), 2.740 (6H, s, mesityl 2,6-CH3), 2.399 (3H, s, mesityl 4-CH3), 2.382 (2H, dt, ArylNHCH2CH2), 2.252 (2H, dt, ArylNHCH2CH2), 2.136 (8H, m, N(CH2CH2CH2CH3)4), 1.490 (36H, s, Aryl 3,5-C(CH3)3), 0.996 (8H, m, N(CH2CH2CH2CH3)4), 0.755 (20H, m, N(CH2CH2CH2CH3)4). IR (C6D6) νNN 1840 cm−1.

[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2)

In a N2 atmosphere glovebox, a 20 mL scintillation vial was charged with [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl (1.431 g, 1.78 mmol), Na (94 mg, 4.09 mmol), and THF (10 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 hours at RT with a glass stirbar, then filtered through Celite. AgOTf (457 mg, 1.78 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture stirred in the dark for 12 hours at RT. Volatiles were removed in vacuo and the residue extracted with toluene and filtered through Celite. The filtrate was reduced to 5 mL and pentane (5 mL) was added. The solution was left at −35 °C overnight and the resulting paramagnetic reddish-pink precipitate was collected on a glass frit, washed with cold pentane and dried; yield 746 mg (53%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 21.855 (2H, br s, ArylNCH2CH2N), 21.044 (2H, br s, ArylNCH2CH2N), 18.526 (2H, br s), 15.909 (2H, br s, ArylNCH2CH2N), 14.900 (2H, br s, ArylNCH2CH2N), 8.214 (2H, s), 2.500 (2H, s), 0.601 (36H, br s, Aryl 3,5-C(CH3)3), −4.423 (6H, br s, mesityl 2,6-CH3), −7.235 (3H, br s, mesityl 4-C H3), −23.100 (2H, br s), −42.300 (4H, br s). IR (C6D6) νNN 2012 cm−1 (C6D6),ν15N15N 1944 cm−1 (C6D6). Anal. Calcd for C46H65N6Mo: C, 69.24; H, 8.21; N, 10.53. Found: C, 69.03; H, 8.46; N, 10.18.

{[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(NH3)}BPh4

In a N2 atmosphere glovebox, a 100 mL solvent bulb equipped with a PTFE screw valve was charged with [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]MoCl (622.5 mg, 0.77 mmol), NaBPh4 (290.9 mg, 0.85 mmol) and PhF (15 mL). The bulb was brought out of the glovebox, and freeze-pump-thaw degassed three times. Anhydrous NH3 (100 mL, 1 atm) which was dried over Na was vacuum transferred into the degassed solvent bulb with the reaction mixture. The mixture immediately changed from orange-red to burgundy. The reaction was stirred for 12 hours at RT. The bulb was brought back into the glovebox and the volatiles removed in vacuo. The residue was extracted with toluene and filtered through Celite. The filtrate was cooled to −35 °C overnight, then filtered through a glass frit to remove a dark reddish solid. The volume of the resulting yellow-brown filtrate was decreased to 5 mL and pentane (15 mL) was added to precipitate a yellow brown solid. The mixture was chilled to −35°C for 1h and then filtered through a glass frit to collect the paramagnetic yellow solid; yield 268 mg (32%): 1H NMR (THF-d8) δ 33.011 (br s), 30.208 (br s), 9.971 (br s), 7.301 (2H, s, Aryl 4-H), 7.215 (4H, s, Aryl 2,6-H), 6.821 (4H, s) 6.691 (2H, s, pyrrole-H), 5.885 (br s), 4.848 (br s), 1.635 (s, Aryl 3,5-C(CH3)3), −24.605 (br s), −91.744 (br s). Anal. Calcd for C70H88BMoN5: C, 76.00; H, 8.02; N, 6.33. Found: C, 75.60; H, 7.90; N, 6.34.

[(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(CO)

In a N2 atmosphere glovebox, a 100 mL solvent bulb equipped with a PTFE screw valve was charged with [(Art-BuN)2Pyr]Mo(N2) (250 mg, 0.313 mmol) and benzene. Outside the glovebox, the bulb was freeze-pump-thaw degassed three times, and then CO (1 atm, 100 mL) was vac-transferred into this bulb from another bulb kept at −78 °C (to freeze out water vapor that may be present in the CO gas). The mixture was warmed to RT and stirred over 12 hours. The reaction mixture was brought back into the N2 atmosphere glovebox whereby benzene was removed in vacuo and toluene added to the residue. The toluene solution was chilled at −35 °C overnight and the resulting paramagnetic green-brown precipitate was collected on a glass frit, washed with pentane and dried; yield 159 mg (64%): 1H NMR (C6D6) δ 20.13 (2H, br s, ArylNCH2CH2N), 17.24 (2H, s, ArylNCH2CH2N), 13.83 (1H, s, pyrrole-H), 12.25 (2H, br s, ArylNCH2CH2N), 8.69 (2H, s, Aryl 4-H), 7.88 (4H, s, Aryl 2,6-H), 3.02 (1H, s, pyrrole-H), 1.82 (2H, s), 0.69 (36H, br s, Aryl 3,5-C(CH3)3), −0.40 (2H, s), −3.72 (6H, s, mesityl 2,6-CH3), −7.54 (3H, br s, mesityl 4-CH3), −19.63 (2H, br s), −34.28 (2H, br s). IR (DME) νNN 1902 cm−1, ν15N15N 1856 cm−1. Anal. Calcd for C47H65N4MoO: C, 70.74; H, 8.21; N, 7.02. Found: C, 70.99; H, 8.11; N, 6.96.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research support from the National Institutes of Health (GM 31978) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Crystal data, structure refinement tables for all X-ray structural studies, and tables of selected bond lengths angles. Supporting Information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Burgess BK. Chem Rev. 1990;90:1377. [Google Scholar]; (b) Burgess BK, Lowe DJ. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2983. doi: 10.1021/cr950055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rees DC, Howard JB. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:559. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rees DC, Chan MK, Kim J. Adv Inorg Chem. 1996;40:89. [Google Scholar]; (e) Eady RR. Chem Rev. 1996;96:3013. doi: 10.1021/cr950057h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Howard JB, Rees DC. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2965. doi: 10.1021/cr9500545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kim J, Woo D, Rees DC. Biochemistry. 1993;32:7104. doi: 10.1021/bi00079a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kim J, Rees DC. Nature. 1992;360:553. doi: 10.1038/360553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Bolin JT, Ronco AE, Morgan TV, Mortenson LE, Xuong LE. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1993;90:1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Chen J, Christiansen J, Campobasso N, Bolin JT, Tittsworth RC, Hales BJ, Rehr JJ, Cramer SP. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1993;32:1592. [Google Scholar]; (k) Einsle O, Tezcan FA, Andrade SLA, Schmid B, Yoshida M, Howard JB, Rees DC. Science. 2002;297:1696. doi: 10.1126/science.1073877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Hardy RWF, Bottomley F, Burns RC. A Treatise on Dinitrogen Fixation. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]; (m) Christiansen J, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52:269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Dos Santos PC, Igarashi RY, Lee H, Hoffman BM, Seefeldt LC, Dean DR. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:208. doi: 10.1021/ar040050z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Dance I. Chem Asian J. 2007;2:936. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (p) Kästner J, Blöchl PE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2998. doi: 10.1021/ja068618h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen AD, Senoff CV. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1965:621. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Fryzuk MD, Johnson SA. Coord Chem Rev. 2000;200–202:379. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hidai M, Mizobe Y. Chem Rev. 1995;95:1115. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hidai M. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;185–186:99. [Google Scholar]; (d) Chatt J, Dilworth JR, Richards RL. Chem Rev. 1978;78:589. [Google Scholar]; (e) Richards RL. Coord Chem Rev. 1996;154:83. [Google Scholar]; (f) Richards RL. Pure Appl Chem. 1996;68:1521. [Google Scholar]; (g) Bazhenova TA, Shilov AE. Coord Chem Rev. 1995;144:69. [Google Scholar]; (h) Shilov AE. Russ Chem Bull Int Ed. 2003;2:2555. [Google Scholar]; (i) MacKay BA, Fryzuk MD. Chem Rev. 2004;104:385. doi: 10.1021/cr020610c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Gambarotta S, Scott J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:5298. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Hidai M, Mizobe Y. Can J Chem. 2005;83:358. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Knobloch DJ, Lobkovsky E, Chirik PJ. Nat Chem. 2010;2:30. doi: 10.1038/nchem.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hanna TE, Lobkovsky E, Chirik PJ. Organometallics. 2009;28:4079. [Google Scholar]; (c) Munha RF, Veiros LF, Duarte MT, Fryzuk MD, Martins AM. Dalton Trans. 2009:7494. doi: 10.1039/b907335c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kozak CM, Mountford P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:1186. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Fryzuk MD. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:127. doi: 10.1021/ar800061g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Chirik PJ. Dalton Trans. 2007;16 doi: 10.1039/b613514e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Smith JM, Lachicotte RJ, Holland PL. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15752. doi: 10.1021/ja038152s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Eckert NA, Smith JM, Lachicotte RJ, Holland PL. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:3306. doi: 10.1021/ic035483x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Holland PL. Canad J Chem. 2005;83:296. [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith JM, Sadique AR, Cundari TR, Rodgers KR, Lukat-Rodgers G, Lachicotte RJ, Flaschenriem CJ, Vela J, Holland PL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:756. doi: 10.1021/ja052707x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Field LD, Li HL, Magill AM. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:5. doi: 10.1021/ic801856q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Whited MT, Mankad NP, Lee Y, Oblad PF, Peters JC. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:2507. doi: 10.1021/ic801855y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Lee Y, Mankad NP, Peters JC. Nat Chem. 2010;2:558. doi: 10.1038/nchem.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Crossland JL, Balesdent CG, Tyler DR. Dalton Trans. 2009:4420. doi: 10.1039/b902524c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Laplaza CE, Cummins CC. Science. 1995;268:861. doi: 10.1126/science.268.5212.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Laplaza CE, Johnson MJA, Peters JC, Odom AL, Kim E, Cummins CC, George GN, Pickering IJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8623. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Mori M. J Organomet Chem. 2004;689:4210. [Google Scholar]; (b) Komori K, Oshita H, Mizobe Y, Hidai M. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:1939. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Yandulov DV, Schrock RR. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6252. doi: 10.1021/ja020186x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yandulov DV, Schrock RR, Rheingold AL, Ceccarelli C, Davis WM. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:796. doi: 10.1021/ic020505l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yandulov DV, Schrock RR. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:1103. doi: 10.1021/ic040095w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yandulov DV, Schrock RR. Science. 2003;301:76. doi: 10.1126/science.1085326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Schrock RR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5512. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Schrock RR. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:955. doi: 10.1021/ar0501121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Ritleng V, Yandulov DV, Weare WW, Schrock RR, Hock AS, Davis WM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6150. doi: 10.1021/ja0306415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Weare WW, Dai X, Byrnes MJ, Chin JM, Schrock RR, Müller P. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602778103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Weare WW, Schrock RR, Hock AS, Müller P. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9185. doi: 10.1021/ic0613457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smythe NC, Schrock RR, Müller P, Weare WW. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9197. doi: 10.1021/ic061554r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smythe NC, Schrock RR, Müller P, Weare WW. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:7111. doi: 10.1021/ic060549k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yandulov DV, Schrock RR. Canad J Chem. 2005;83:341. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Cao Z, Zhou A, Wan HL, Zhang Q. Int J Quant Chem. 2005;103:344. [Google Scholar]; (b) Le Guennic B, Kirchner B, Reiher M. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:7448. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Studt F, Tuczek F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:5639. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mersmann K, Horn KH, Böres N, Lehnert N, Studt F, Paulat F, Peters G, Ivanovic-Burmazovic I, van Eldik R, Tuczek F. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:3031. doi: 10.1021/ic048674o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Khoroshun DV, Musaev DG, Morokuma K. Molecular Physics. 2002;100:523. [Google Scholar]; (f) Neese F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:196. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hölscher M, Leitner W. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2006:4407. [Google Scholar]; (h) Magistrato A, Robertazzi A, Carloni P. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007;3:1708. doi: 10.1021/ct700094y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Studt F, Tuczek F. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:1278. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Stephan GC, Sivasankar C, Studt F, Tuczek F. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:644. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Reiher M, Le Guennic B, Kirchner B. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:9640. doi: 10.1021/ic0517568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schenk S, Le Guennic B, Kirchner B, Reiher M. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:3634. doi: 10.1021/ic702083p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schenk S, Kirchner B, Reiher M. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:5073. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wampler KM, Schrock RR. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:8463. doi: 10.1021/ic701472y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreickmann T, Arndt S, Schrock RR, Müller P. Organometallics. 2007;26:5702. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rieth RD, Mankad NP, Calimano E, Sadighi JP. Org Lett. 2004;6:3981. doi: 10.1021/ol048367m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Marinescu SC, Singh R, Hock AS, Wampler KM, Schrock RR, Müller P. Organometallics. 2008;27:6570. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wampler KM, Schrock RR. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:10226. doi: 10.1021/ic801695j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Al Obaidi N, Brown KP, Edwards AJ, Hollins SA, Jones CJ, McCleverty JA, Neaves BD. Chem Comm. 1984:690. [Google Scholar]; (d) Al Obaidi N, Chaudhury M, Clague D, Jones CJ, Pearson JC, McCleverty JA, Salam SS. Dalton Trans. 1987:1733. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mösch-Zanetti NC, Schrock RR, Davis WM, Wanninger K, Seidel SW, O’Donoghue MB. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11037. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kol M, Schrock RR, Kempe R, Davis WM. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:4382. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Gütlich P, McGarvey BR, Klaeui W. Inorg Chem. 1980;19:3704. [Google Scholar]; (b) Klaeui W, Eberspach W, Gütlich P. Inorg Chem. 1987;26:3977. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith ME, Andersen RA. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:1119. [Google Scholar]; (d) LaMar GN, Horrocks WD Jr, Holm RH, editors. NMR of Paramagnetic Molecules. Academic; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kriley CE, Fanwick PE, Rothwell IP. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:5225. [Google Scholar]; (f) Saillant R, Wentworth RAD. Inorg Chem. 1969;8:1226. [Google Scholar]; (g) Cotton FA, Eglin JL, Hong B, James CA. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:4915. [Google Scholar]; (h) Cotton FA, Chen HC, Daniels LM, Feng X. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:89980. [Google Scholar]; (i) Fettinger JC, Keogh DW, Kraatz HB, Poli R. Organometallics. 1996;15:5489. [Google Scholar]; (j) Campbell GC, Reibenspies JH, Haw JF. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:171. [Google Scholar]; (k) Boersma AD, Phillipi MA, Goff HM. J Magn Reson. 1984;57:197. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong FY, Klapars A, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2002;4:581. doi: 10.1021/ol0171867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwong FY, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2003;5:793. doi: 10.1021/ol0273396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.{[HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)}Na(THF)x was synthesized from [HIPTN3N]MoCl (500 mg, 0.291 mmol) in a manner similar to that employed to synthesize [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2)MgCl(THF)3 (ref. 8b) using 2 equiv of sodium (mirror) in THF (5 mL). The mixture was stirred with a glass-coated stir bar for 4 days. Solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was extracted with pentane and the extract was filtered through Celite. The filtrate was stood overnight at −35 °C and the emerald green microcrystalline solid obtained was collected on a glass frit; yield 350 mg (69%).

- 25.(a) Chaney AL, Marbach EP. Clinical Chem. 1962;8:130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Weatherburn MW. Anal Chem. 1967;39:971. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoffelbach F, Saurenz D, Poli R. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2001;10:2699. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradley DC, Chisholm MH. J Chem Soc A. 1971:2741. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ditto SR, Card RJ, Davis PD, Neckers DC. J Org Chem. 1979;44:894. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frampton MJ, Akdas H, Cowley AR, Rogers JE, Slagle JE, Fleitz PA, Drobizhev M, Rebane A, Anderson HL. Org Lett. 2005;7:5365. doi: 10.1021/ol0520525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nomura N, Ishii R, Yamamoto Y, Kondo T. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:4433. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.