Abstract

Soft-tissue sarcomas (STSs) are rare mesenchymal tumors that arise from muscle, fat and connective tissue. Currently, over 75 subtypes of STS are recognized. The rarity and heterogeneity of patient samples complicate clinical investigations into sarcoma biology. Model organisms might provide traction to our understanding and treatment of the disease. Over the past 10 years, many successful animal models of STS have been developed, primarily genetically engineered mice and zebrafish. These models are useful for studying the relevant oncogenes, signaling pathways and other cell changes involved in generating STSs. Recently, these model systems have become preclinical platforms in which to evaluate new drugs and treatment regimens. Thus, animal models are useful surrogates for understanding STS disease susceptibility and pathogenesis as well as for testing potential therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas (STSs) are a relatively rare, heterogeneous group of tumors that account for <1% of adult human cancer and 15% of pediatric malignancies (Borden et al., 2003). Largely of mesenchymal origin, STSs originate from a variety of tissue types, including muscle, cartilage, adipose tissue, fibrous tissue and blood vessels. This class of tumors is characterized by marked heterogeneity, with more than 75 histopathological subtypes currently recognized (Borden et al., 2003; Helman and Meltzer, 2003). Over 30% of adult patients with STS develop fatal lung metastases, with a median survival of 15 months (Helman and Meltzer, 2003). Treatment for STSs has lagged behind more common epithelial cancers, and survival from the most common STS subtypes has remained unchanged for several decades. The mechanisms associated with sarcoma development remain largely unclear because of the rarity of the disease, its large number of histological subtypes and its varied clinical behavior. As such, preclinical models to dissect mechanisms underlying sarcoma development, progression and treatment are greatly needed.

Sarcomas are traditionally classified by the site of tumor formation. However, recent advances support the view that molecular features are more relevant to tumor biology and treatment regimens (Helman and Meltzer, 2003). Cytogenetic studies have identified two broad groups of STSs. The first group, which makes up approximately one-third of all STSs, is characterized by relatively simple diploid karyotypes with few chromosomal rearrangements. The etiology of these tumors can usually be traced to a chromosomal translocation resulting in an oncogenic fusion gene, such as Pax3-Fkhr (Fkhr is also known as Foxo1a) in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS). By contrast, the second group of sarcomas displays complex karyotypes reflecting global genomic instability. Most human sarcomas, including leiomyosarcoma, belong to this karyotypically complex subgroup and contain mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene pathway. This review will discuss the generation and application of successful animal models for both groups of STSs.

Lessons from the earliest models of STS

Historically, sarcoma research relied on human sarcoma cell lines and immunocompromised mice. Many human cell lines derived from different subtypes of sarcoma are available, including synovial sarcoma (SW982), rhabdomyosarcoma (RD and RH4), fibrosarcoma (HT1080), liposarcoma (SW872), Ewing’s sarcoma (RD-ES) and leiomyosarcoma (HTB88). In vitro studies with these cell lines have been a mainstay of sarcoma research and drug screening efforts (Hoffmann et al., 1999; Morioka et al., 2001; Tirado et al., 2005; Ying et al., 2006), leading to insights into both tumor progression (Toft et al., 2001) and metastasis (Zhang and Hill, 2007; Guo et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2009). These cells have also been used as subcutaneous and orthotopic xenografts in immunocompromised mice (Sausville and Burger, 2006).

Despite the advances made with xenograft models, these tumor systems have several limitations. First, the patient-derived cell lines come from individuals with diverse genetic backgrounds, and serial propagation in culture can introduce mutations. Second, interactions between tumor cells and the host microenvironment are difficult to model in xenograft systems. For instance, stromal cells might impact tumor growth and development (List et al., 2005), metastasis (Karnoub et al., 2007), and response to therapy (Meads et al., 2009). Injection of a large number of human tumor cells into the non-native microenvironment of the mouse precludes the study of early events in tumor formation. Third, the potential incompatibility between mouse stroma and human tumor cells could also affect the growth of xenografts and their response to treatment (Tzukerman et al., 2006). Finally, development of xenograft tumors in immunocompromised hosts also ignores crucial interactions between the tumor and host immune system that can lead to alterations in tumor progression and development (de Visser et al., 2006). Thus, despite many advances, the use of in vitro and xenograft systems to model human sarcomas has led to relatively few new drug treatments, in spite of the number of compounds that have shown promise in these models (Gura, 1997). Therefore, there is great interest in studying sarcoma biology in animal models of primary tumors.

One of the earliest primary-tumor mouse models that developed STSs were the Trp53 (p53)-knockout mice (Donehower et al., 1992; Jacks et al., 1994). Like humans that carry mutations in the tumor suppressor p53 and are susceptible to sarcoma development as part of the Li-Fraumeni syndrome, p53−/− mice are tumor-prone with approximately one-third of tumors identified as sarcomas, including angiosarcomas, undifferentiated sarcomas and osteosarcomas. The p53 mutant mice were crossed with mice carrying a deletion for the neurofibromin (Nf1) tumor suppressor gene, which is mutated in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 and is a negative regulator of the Ras pathway. These p53−/+; Nf1−/+ mice develop primary malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) (Cichowski et al., 1999). Since these reports, it has become clear that the function of both the tumor suppressor p53 and the Ras pathway play important roles in sarcoma biology.

The role of other tumor suppressor pathways in sarcomagenesis is less clear. Greater than 60% of osteosarcomas display a loss of heterozygosity at the retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor locus (Wadayama et al., 1994). Consistent with a role in osteosarcoma development, mouse models have shown that loss of Rb can potentiate the development of osteosarcomas in the context of mutant p53 (Berman et al., 2008; Walkley et al., 2008). However, despite the clear role of Rb in osteosarcoma development, attempts to identify a role for Rb in STSs have been met with conflicting reports (Cance et al., 1990; Karpeh et al., 1995; Dei Tos et al., 1996; Kohashi et al., 2008). Attempts to generate STSs in transgenic animals have not demonstrated a causative role for Rb in their development. Mutation in Rb alone in the mouse limb bud was not sufficient to generate STSs without cooperating mutations in p53 (Lin et al., 2009). Therefore, a recurring theme reflected in the animal models of sarcoma discussed below is mutation of p53 and of components of the Ras pathway, both of which have been shown to have definitive roles in the development of STSs.

The primary-tumor models of STS described in this review use a variety of genetic strategies to express oncogenes. For example, an oncogene can be expressed from either a transgene inserted into the genome (i.e. Ef1a inserted in myxoid liposarcoma) or knocked-in to the endogenous promoter (i.e. Pax3-Fkhr in ARMS). A gene can be mutated throughout the entire animal or can be controlled by a tissue-specific promoter. Also, a gene can be expressed throughout development or can be activated in the adult animal through a temporally regulated inducible mechanism (i.e. by CreER, as discussed below). In some cases, expression of a single gene is not sufficient to cause STS formation, suggesting a ‘second-hit’ of additional mutations might be required to initiate tumorigenesis.

New models of cytogenetically simple STS: renegade transcription factors

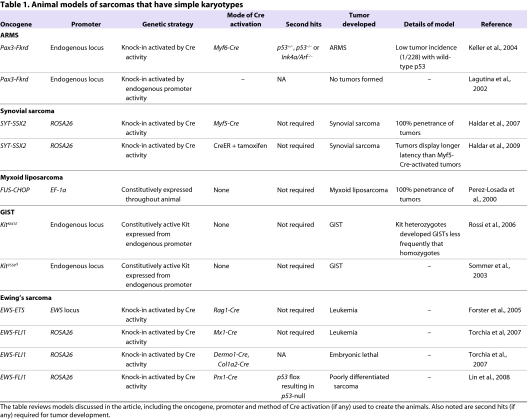

The subgroup of STSs that display tumor-specific chromosomal translocations includes ARMS, synovial sarcoma, myxoid liposarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma (Table 1). Most of these chromosomal translocations result in fusion genes that act as renegade transcription factors and are central to the pathogenesis of these tumors. In most cases, these fusion genes are composed of the DNA-binding domain of a transcription factor with a transactivation regulatory domain.

Table 1.

Animal models of sarcomas that have simple karyotypes

ARMS model

ARMS is one of the most common forms of pediatric sarcomas, occurring predominantly in adolescents. It also provides one of the best-known examples of fusion-gene-driven sarcomas. A t(2;13) chromosomal translocation fuses the paired-box transcription factor Pax3 (or, less commonly, Pax7) with the transactivation domain of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR (Barr, 2001). The Pax3-Fkhr fusion gene results in aberrant activation of Pax3 gene targets via the Pax3 DNA-binding motif. Both Pax3 and Pax7 are expressed throughout the developing embryo, including in skeletal muscle precursors and the neural crest. In adults, they mark satellite cells, the quiescent stem cells of skeletal muscle. Thus, the oncogenic function of Pax3-Fkhr is postulated to involve aberrant activation of an embryonic myogenic developmental pathway.

Early studies in avian fibroblasts demonstrate that expression of the Pax3-Fkhr fusion gene can transform cells, leading to anchorage-independent growth. However, cooperating mutations were necessary to drive tumor formation in vivo (Scheidler et al., 1996). This suggests that the Pax3-Fkhr fusion gene might be required, but not sufficient, for ARMS tumorigenesis. Indeed, other mutations have also been found in ARMS, including amplification of MDM2 (Forus et al., 1993) and MYC (Driman et al., 1994). Several studies have identified Pax3-FKHR targets to include genes involved in myogenic differentiation (Khan et al., 1999). Other studies have demonstrated that disruption of Pax3 function or its downstream myogenic differentiation program in ARMS cells induced apoptosis and inhibited tumor formation in immunocompromised mice (Bernasconi et al., 1996; Fredericks et al., 2000; Taylor et al., 2009). These data imply that the Pax3-FKHR fusion protein is necessary for tumor maintenance of ARMS.

To study the oncogenic function of the Pax3-Fkhr fusion gene in a primary-tumor model, mice were generated by knocking-in the Fkhr gene downstream of the Pax3 locus. This knock-in strategy allows the Pax3-FKHR fusion protein to be expressed from the identical promoter and tissue type as found in human ARMS (Lagutina et al., 2002). This fusion gene was expressed in the neural-crest and muscle precursor cells, faithfully reflecting the endogenous expression pattern of Pax3 during development. However, after 1.5 years, no tumors developed in these animals. These results suggest that additional gene mutations might be necessary to generate ARMS.

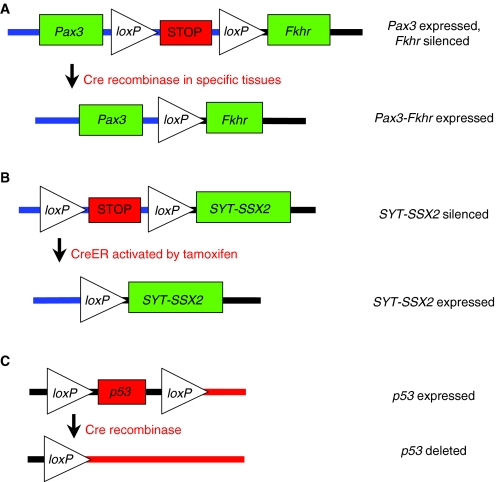

An alternative mouse model of ARMS used Cre-loxP technology to obtain tissue-specific expression of the fusion gene (Keller et al., 2004b; Keller et al., 2004a). Cre is a site-specific recombinase that recognizes loxP sequences, resulting in excision of DNA that is flanked by two loxP sites (Fig. 1A). This technique is widely used to model cancer in the mouse by deleting tumor suppressors or activating oncogenes in specific tissue types. Using a conditional knock-in approach, a silenced portion of the Fkhr gene was inserted downstream of the full-length Pax3 gene. Under normal conditions, Pax3 is faithfully transcribed. However, in the presence of Cre recombinase, the floxed silencing element is removed, resulting in Pax3-Fkhr fusion gene expression. To determine a cellular pool involved in ARMS development, the Pax3-Fkhr mice were bred to mice expressing Cre under distinct myogenic-lineage-specific promoters. No tumors were observed when crossed with Pax7-Cre mice that express Cre in the perinatal muscle satellite cells. However, expression of Pax3-Fkhr in mature, differentiating muscle cells (driven by Myf6-Cre) resulted in ARMS in a small number of mice (1/228). Tumor incidence was greatly accelerated by pairing of the Myf6-Cre; Pax3-Fkhr homozygous mice with knock-out alleles of either Trp53 (3/17 mice) or Ink4a/ARF (Cdkn2a; 4/27 mice). This model was later shown to authentically recapitulate the histological features and transcriptional profiles of the human disease (Nishijo et al., 2009). This work supports previous findings (Lagutina et al., 2002) that second hits in tumor suppressor pathways are required to develop Pax3-Fkhr ARMS in mice.

Fig. 1.

Gene activation or deletion by Cre recombinase. Cre recombinase deletes DNA that is flanked by loxP sites. (A) Fusion-gene activation by tissue-specific Cre. Removal of a silenced STOP cassette by Cre allows for expression of the Pax3-Fkhr fusion gene (Keller et al., 2004b). (B) Gene activation by CreER activity. Addition of tamoxifen activates CreER, allowing for removal of the silenced loxP-STOP-loxP cassette. This results in expression of the oncogene SYT-SSX2 (Haldar et al., 2007). (C) Gene deletion via Cre recombinase. Cre activity removes the p53 gene flanked by two loxP sites (Jonkers et al., 2001).

Synovial sarcoma

Synovial sarcomas occur mainly in adolescents and young adults. The majority of synovial sarcomas display a specific t(X;18) chromosomal translocation resulting in fusion of the SYT (SS18) gene with that encoding an SSX protein, either SSX1, SSX2 or SSX4. The SYT gene is a putative transcriptional coactivator, whereas the SSX family members are believed to be transcriptional co-repressors (Haldar et al., 2008). Consistent with the genetic data from human tumors, expression of the human SYT-SSX fusion gene in rat 3Y1 fibroblast cells resulted in the formation of synovial-sarcoma-like tumors in nude mice (Nagai et al., 2001).

Although some synovial sarcomas develop near joints, these tumors bear little resemblance to the surrounding synovial lining. For this reason, the tissue of origin remains unclear, although a cell of the muscle lineage has been proposed as a potential source. To examine this possibility, a mouse knock-in model of synovial sarcoma was generated so that the SYT-SSX2 fusion gene could be expressed from the ubiquitous Rosa26 promoter at various stages throughout muscle development (Haldar et al., 2007). In this model, expression of the SYT-SSX2 fusion gene was initiated by excision of the upstream loxP-flanked transcriptional stop cassette via Cre recombinase. Conditional expression of the fusion gene was achieved by tissue- or cell-specific expression of Cre recombinase. In addition, the SYT-SSX2 gene was followed by an IRES-eGFP element to facilitate cell-lineage tracing via the fluorescent marker. Crossing the SYT-SSX2 mouse to Myf5-Cre animals resulted in a high-fidelity synovial sarcoma model with 100% penetrance. Myf5 is expressed in myoblasts, a committed progenitor cell for skeletal muscle. Use of Cre drivers genetically upstream of Myf5 – including Hprt-Cre (early-stage embryo), Pax3-Cre and Pax7-Cre (both satellite cell specific) – resulted in embryonic lethality. Breeding the SYT-SSX2 mouse to those containing Cre drivers of genes expressed in differentiated skeletal muscle lineage – including Myf6-Cre (Mrf4), which is expressed in myocytes and fused myofibers – led to myopathy. These genetic data suggest that SYT-SSX2 can initiate synovial sarcomas from a cell derived from the muscle lineage.

The SYT-SSX knock-in model has provided insight into the development of the distinct subtypes of synovial sarcoma tumors. Human synovial sarcomas can be classified as monophasic (composed of spindle cells) or biphasic (containing a mixture of spindle and epithelial cells). Both histologies were present in the tumors from SYT-SSX2; Myf5-Cre mice (Haldar et al., 2007; Haldar et al., 2008). As tumor size increased, the tumors gained more biphasic histology, suggesting a progression from a monophasic to a biphasic subtype as tumors progress.

In a more recent publication, an alternative SYT-SSX2 mouse tumor model used tamoxifen-inducible CreER technology to activate the oncogenic fusion gene (Haldar et al., 2009). In this system, the CreER protein can provide temporal activation of SYT-SSX2 expression in the adult through exogenous application of tamoxifen (Fig. 1B). This system contrasts with the previously discussed promoter-driven Cre system (Myf5-Cre, etc.), in which Cre activity is constitutively found within all cells of a specific tissue. The distinction between these two model systems could be important for defining the events necessary for sarcoma development. In human tumors, the genetic mutation (i.e. SYT-SSX) occurs only in a small group of neoplastic cells within a given tissue. As such, in a model utilizing tissue-specific Cre drivers, a developing neoplasm would be surrounded by an artificial microenvironment comprised of cells expressing identical Cre-induced oncogenes. By contrast, the CreER system allows Cre activation to occur in a small population of cells at a precise time. Thus, this strategy might better mimic the natural pathogenesis of cancer through activation of the oncogene in a subset of cells that are surrounded by a microenvironment of relatively ‘normal’ tissue.

Using a mouse strain expressing CreER from the ubiquitous Rosa26 promoter, tamoxifen injection of SYT-SSX2; CreER mice resulted in formation of soft-tissue tumors that histologically resemble synovial sarcomas. Although tamoxifen activates CreER in multiple tissue types, mice expressing the STY-SSX2 gene only developed synovial sarcoma. Interestingly, the incidence of tumor development in SYT-SSX2; CreER mice was similar regardless of whether the mice were injected with tamoxifen, suggesting that tumors developed after spontaneous activation of CreER. Despite the distinct modes of Cre activation in the models described above, microarray analysis revealed a high genetic similarity between the SYT-SSX2; CreER tumors (Haldar et al., 2009) and the SYT-SSX2; Myf5-Cre tumors (Haldar et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the two models did display important differences. The SYT-SSX2; CreER mice display longer survival (1 year vs 3.5 months), but developed larger tumors, which caused lethality. CreER-driven tumors were concentrated in the paraspinal region and face, whereas Myf5-Cre tumors arose most frequently in the intercostal region. Both strains developed tumors in the limbs with lower frequency than in other parts of the body. Tumors in both models occurred in proximity to skeletal tissue, suggesting a role for this microenvironmental niche in the development of synovial sarcoma. The differences in tumor size, latency and anatomical location suggest that some synovial sarcomas can arise from a non-myogenic cell-of-origin.

Myxoid liposarcoma

Liposarcomas are a diverse group of STSs that histologically resemble white adipose tissue. Although most subsets of liposarcomas have not been studied in animal models, a mouse model of myxoid liposarcoma has been generated. Myxoid liposarcoma is characterized by a t(12;16)(q13;p11) chromosomal translocation resulting in fusion between the FUS and CHOP (also known as DDIT3 and GADD153) genes in more than 90% of patients (Perez-Mancera and Sanchez-Garcia, 2005). FUS encodes a constitutively expressed RNA-binding protein that might regulate splicing. The CHOP gene expresses a stress-regulated basic-leucine-zipper-domain transcription factor with anti-apoptotic properties. The FUS-CHOP fusion gene replaces the RNA-binding domain of FUS with the activation domain of CHOP. Overexpression of the FUS-CHOP oncogene in primitive mesenchymal cells – including human fibrosarcoma cells (Engstrom et al., 2006) and murine primary bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitors (Riggi et al., 2006) – produced myxoid or round cell liposarcomas in xenograft experiments. These results indicate that the FUS-CHOP oncogene can initiate myxoid liposarcoma development.

Mice with ubiquitous expression of the FUS-CHOP fusion gene from the Ef1a promoter developed large liposarcomas with 100% penetrance (Perez-Losada et al., 2000). The level of the adipocyte regulatory protein PPAR-γ was highly elevated in these tumors, suggesting an adipocytic lineage. These tumors were always found within white adipose tissue, and other organs did not show abnormal growths, despite ectopic expression of the oncogene with the Ef1a promoter. By contrast, driving expression of the oncogene with the aP2 promoter of immature adipocytes did not result in tumors, although mice did accumulate more white adipose tissue (Perez-Mancera et al., 2007). This suggests that the cell of origin in the Ef1a-driven liposarcomas is not an immature adipocyte or their descendant.

To determine the protein domain that is sufficient for tumorigenesis, the FUS and CHOP genes were examined in separate mouse models (Perez-Mancera et al., 2002). White adipose tissue from Ef1a-FUS or Ef1a-CHOP single transgenic mice was normal. Creation of double transgenic Ef1a-FUS × Ef1a-CHOP mice resulted in liposarcomas that develop at the same rate as the FUS-CHOP fusion gene mice (Perez-Mancera et al., 2002). Tumors were not identified in any other tissues, despite the ubiquitous expression from the Ef1a promoter. These models illustrate the requirement for both FUS and CHOP function in myxoid liposarcoma tumorigenesis, and demonstrate that these proteins can function in trans to initiate tumor development.

Ewing’s sarcoma

Ewing’s sarcoma is a rare, small-round-cell tumor found within bone or soft tissue, and most commonly occurs during childhood and early adulthood. The tumors are defined by a chromosomal fusion between the EWS RNA-binding protein and one of several E-twenty six (ETS) transcription factors, with the EWS-FLI1 fusion gene being the most common (Ordonez et al., 2009). Direct targets of the EWS-FLI1 oncogene have been difficult to identify, and the fusion gene is proposed to function through direct upregulation of NKX2.2, a potent transcriptional repressor (Owen et al., 2008). Introduction of the fusion gene into primary human fibroblasts resulted in senescence (Lessnick et al., 2002), whereas EWS-FLI1 addition to murine bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitors resulted in Ewing’s-sarcoma-like tumors (Riggi et al., 2005). Inhibition of EWS-FLI1 expression by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides in human Ewing’s sarcoma cells reduced xenograft tumor growth (Tanaka et al., 1997). These studies imply that EWS-FLI1 drives sarcomagenesis in a cell-type-specific manner and might also be required for tumor maintenance.

Despite the genetic and xenograft data supporting the role of EWS-ETS genes in Ewing’s sarcoma, the majority of mouse models expressing these fusion genes develop leukemias. Although the EWS-FLI1 fusion product has not been identified in human leukemias, a related chromosomal translocation involving the ETS family member ERG has been reported (Ichikawa et al., 1994). Mice expressing the EWS-ETS fusion gene from the Rosa26 promoter under the control of the lymphocyte-specific Rag1-Cre develop T-cell lymphomas within 5 months (Forster et al., 2005). Additionally, expression of the EWS-FLI1 gene in the bone marrow by Mx1-Cre induces myeloid or erythroid leukemia in mice (Torchia et al., 2007). The rapid and severe disease progression in these mice might have precluded the development of sarcomas in this model. In an attempt to circumvent this limitation, EWS-FLI1 mice were crossed to Dermo1-Cre or Col1a2-Cre mice to express the fusion gene in mesynchemal tissue during embryonic development. However, early expression of the EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein resulted in embryonic lethality (Torchia et al., 2007).

A mouse model of EWS-FLI1-driven sarcoma was developed using a conditional EWS-FLI1 gene under control of Prx1-Cre (Lin et al., 2008). Prx1-Cre is expressed in primitive mesenchymal tissues of the embryonic limb bud, and thus avoids the embryonic lethality that was seen with the Dermo1-Cre and Col1a2-Cre mice described above. The EWS-FLI1; Prx1-Cre mouse has truncated limbs, muscle atrophy and an accumulation of immature bone, but does not develop tumors, demonstrating that EWS-FLI1 expression alone is not sufficient for tumor formation. However, addition of a ‘second hit’ through deletion of p53 in triple transgenic mice (EWS-FLI1; p53flox/flox; Prx1-Cre) did result in poorly differentiated STSs (Lin et al., 2008). These mice contain a floxed p53 allele with exons 2–10 flanked by loxP sites (Fig. 1C), resulting in deletion of the p53 gene in the presence of Cre recombinase (Jonkers et al., 2001). This finding suggests that, in some cell types, genetic inactivation of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway can cooperate with EWS-FLI1 in sarcomagenesis.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common sarcoma of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. They are believed to arise from mesenchymal cells within the wall of the GI tract, which are called the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs). Although the development of GISTs does not seem to be driven by a fusion gene, these STSs do have relatively simple karyotypes and are classified with the first grouping of STSs. Almost 90% of all GISTs have activating mutations in the receptor tyrosine kinase Kit (Helman and Meltzer, 2003). Following the initial identification of Kit as an oncogene for feline sarcomas (Besmer et al., 1986), activating mutations in Kit have been identified in many human tumors, including in GISTs, leukemias and mastocytosis (Furitsu et al., 1993; Hirota et al., 1998). Additional studies have identified a direct role for Kit in the development of hematopoetic stem cells, germ cells and ICCs.

Two independent groups have generated mouse models of GIST through expression of an activated form of the Kit gene. A homozygous knock-in of activated KitK641E/K641E to the mouse Kit locus results in ICC hyperplasia and GISTs, with 100% penetrance (Rubin et al., 2005). KitK641E/+ heterozygotes did develop small GISTs, although the ICC hyperplasia was much less extensive, illustrating a dose dependency for Kit activation. No tumors were identified outside of the GI tract of these mice. An additional study produced a mouse with a Kit-activating mutation KitV558Δ/+, deleting valine 558 in exon 11 (Sommer et al., 2003). KitV558Δ/+ mice developed GISTs and had a 50% survival rate of 9 months. These mice had elevated levels of mast cells, although there was no elevation in overall hematocrit or white blood cell levels. This mouse model of GIST has been used to investigate chemotherapeutic treatment of Kit-dependent tumors, and will be discussed in later sections (Rossi et al., 2006).

Animal models of sarcomas with complex karyotypes: karyotypic confusion

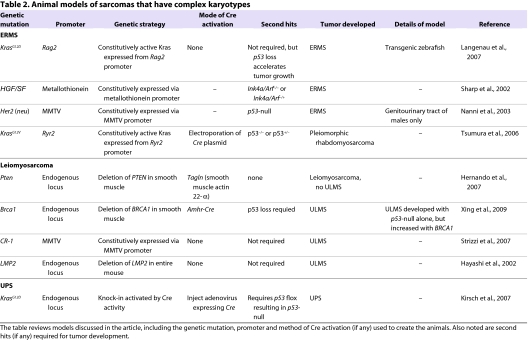

The second main group of sarcomas is not defined by simple chromosomal translocations or an activating mutation in a single oncogene, but instead display complex karyotypes indicative of global genomic instability. These tumors include embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS), undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma [UPS; also known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH)] and leiomyosarcoma (Table 2).

Table 2.

Animal models of sarcomas that have complex karyotypes

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma

ERMS is the most common subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma, and is histologically and molecularly distinct from the alveolar subtype (ARMS). Common genetic hallmarks of human ERMS include inactivation of the p53 pathway and loss at 11p15.5, which might encode a tumor suppressor gene (Besnard-Guerin et al., 1996). However, no single genetic lesion has been uniformly linked to ERMS. Thus, attempts to genetically model ERMS have been focused on altering pathways known to be mutated in rhabdomyosarcomas, including p53, Rb, MYC and RAS (Merlino and Helman, 1999). Disruption of these pathways in human skeletal muscle myoblasts led to ERMS-like cells that were capable of generating tumors in xenograft models (Linardic et al., 2005). This work is consistent with committed skeletal muscle myoblasts being a cell of origin for ERMS, but it does not rule out other potential cells of origin.

Expression of oncogenic KrasG12D in muscle satellite cells of transgenic zebrafish results in an animal model of ERMS (Langenau et al., 2007). Injection of zebrafish embryos with a constitutively active, oncogenic Kras gene (KrasG12D) under control of the Rag2 promoter produced tumors in over half of the animals. These masses were highly invasive and were composed of both multinucleated striated muscle fibers and undifferentiated muscle cells characteristic of the ERMS subtype. Microarray analyses identified upregulation of the zebrafish ERMS (zERMS) gene set within human ERMS (hERMS), but not within human ARMS, data sets. Further analysis showed that the zERMS data set is significantly associated with gene sets from other RAS-driven tumors, including human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and murine lung adenocarcinoma. The identification of a RAS oncogene signature in the zebrafish model supports a role for this pathway in ERMS formation.

This zebrafish model also provides information about the cell of origin for ERMS. In zebrafish, expression of the rag2 promoter is found within the mononucleated skeletal muscle cells (satellite cells and differentiating myoblasts), but not in multinucleated terminally differentiated muscle. Although the rag2 promoter is also found in B- and T-cell progenitors, lymphoid hyperplasia was rarely observed. This model supports a muscle progenitor cell as a potential initiator for the ERMS tumor subtype. No inactivating mutations in the p53 gene were identified in the zebrafish ERMS tumors, although elevation of p53 suppressors were found, including Mdm2 and survivin. Tumor formation was accelerated when the rag2-KrasG12D transgene was injected into p53 loss-of-function mutants. These data support a role for the p53 pathway in acceleration of ERMS tumor growth.

Interestingly, other investigators used the same genes (Kras and p53) to generate a mouse model of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, which is a subset of chemoresistant adult rhabdomyosarcoma and often arises in the large muscles of the extremities (Tsumura et al., 2006). This model utilizes a Cre-activatable oncogenic KrasG12V expressed from the myocardial ryanodine receptor type 2 (Ryr2) promoter. Oncogene activation occurs by electroporation of a Cre-expressing plasmid into the muscle of the lower leg. Tumors developed in all p53−/− mice and in 40% of p53+/− mice. The tumors stained positive for the rhabdomyosarcoma marker desmin and α-sarcomeric actin.

Two mouse models of ERMS also report a crucial role for the p53 tumor suppressor pathway. In Ink4a/Arf−/− mice, expression of HGF/SF, which activates the Met growth factor receptor, resulted in highly penetrant malignant rhabdomyosarcomas (Sharp et al., 2002). These mice exhibit hyperplastic satellite cells at 6–10 weeks of age, suggesting a role for satellite cells in ERMS tumorigenesis. Mice expressing one wild-type allele of Ink4a/Arf also developed ERMS, albeit with a longer latency. In an alternative model, activation of the Her2 (neu) gene coupled with p53 inactivation produced spontaneous ERMS-like tumors in the genitourinary tract of male BALB/c mice (Nanni et al., 2003). Her2 is expressed in multiple tumor types, including in ∼50% of human rhabdomyosarcomas. Because female mice did not develop sarcomas, this might suggest a gender-specific role for the Her2 gene in these tumors. Taken together, these animal models support the importance of p53 loss for ERMS development in a mammalian system.

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma

UPS (also known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma, or MFH) is one of the most common subtypes of STS in adult patients. The diagnosis of UPS refers to tumors displaying high-grade pleomorphic cells in a storiform growth pattern. Genetically, UPS sarcomas display a complex karyotype reflecting genomic instability. There are no known single oncogenic mutations associated with UPS, although activation of the Kras pathway might be involved (Mito et al., 2009). Because the cell of origin for this tumor remains unclear, some have suggested that UPS is not a distinct clinical entity, but instead represents a common undifferentiated state of diverse tumors that are derived from different mesenchymal cells.

A mouse model of high-grade, poorly differentiated primary STS was generated in mice with conditional mutations in both oncogenic Kras and mutant p53 (KrasG12D/+; p53flox/flox) (Kirsch et al., 2007). In this model, Cre activates expression of oncogenic Kras by deletion of an upstream floxed transcription/translation STOP cassette (termed ‘loxP-STOP-loxP’, or LSL cassette) inserted into the endogenous Kras promoter. Cre is expressed by intramuscular injection of an adenovirus (Ad-Cre) instead of a genetic tissue-specific Cre driver. High-grade sarcomas develop at the site of injection 2–3 months after intramuscular Cre delivery. Additionally, up to 50% of these mice develop lung metastases, which are a hallmark of human sarcoma pathogenesis. By spatially and temporally restricting tumor initiation, sarcomas develop in adult mice at a defined anatomical site. This is similar to advantages described for the CreER technology above (Haldar et al., 2009), but avoids the potential leakiness of genetic CreER systems. Additionally, the site of tumor formation can be tightly controlled by Ad-Cre injection, in contrast to systemic activation of CreER through intraperitoneal tamoxifen delivery. The adenovirus-based mode of Cre delivery is also well-suited to generate tumors with no known cell of origin, precluding the need for tissue-specific Cre drivers.

To determine the subtype of human sarcoma that most closely resembles the Ad-Cre-activated KrasG12D/+; p53flox/flox model, gene expression analysis generated a mouse sarcoma signature (Mito et al., 2009). This signature is highly enriched in human UPS compared with other types of STS. Samples of human UPS were also highly enriched for both the mouse sarcoma signature and a genomic signature for Ras pathway activation, compared with other common subtypes of STS. These data suggest that this mouse model is most similar to UPS, and also suggest a link between UPS and Ras pathway activation.

The Ad-Cre-generated KrasG12D/+; p53flox/flox model of UPS (Kirsch et al., 2007) discussed above is similar to the Cre-injectable KrasG12V/+; p53flox/flox model (Tsumura et al., 2006) of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma. In both models, deletion of p53 and activation of oncogenic Kras resulted in highly aggressive STSs, but apparently of different subtypes (UPS vs pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma). Although it is possible that these two models represent different spectrums of the same tumor type, the models differ in several key features. First, different activating Kras mutations are used (G12D vs G12V), in addition to different promoters driving Kras expression (endogenous promoter vs Ryr2). Second, one model activated oncogenic Kras expression by Ad-Cre infection, whereas the other model utilized electroporation of a Cre-expressing plasmid. Therefore, it is possible that Cre is expressed in different cells using the adenovirus and the electroporation strategies. Third, a p53-null background was required for tumor development in the UPS model, whereas tumors were generated in p53+/− mice of the pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma model. Taken together, the spectrum of tumor types displayed in these models with similar genetic mutations highlights the complexities involved in studying sarcomas in animal models.

Leiomyosarcoma

Leiomyosarcomas are malignant growths of the smooth muscle and can form at multiple sites throughout the body. For instance, uterine leiomyosarcomas (ULMSs) are rare tumors that arise from the smooth muscle of the uterine wall. Deletion of 10q, which contains the tumor suppressor gene PTEN, has been found in human leiomyosarcomas (Segal et al., 2003). Indeed, activation of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, which is inhibited by PTEN activity, has also been reported in leiomyosarcoma cases (Hernando et al., 2007).3 To investigate the role of the PI3K-AKT pathway in leiomyosarcomas, a mouse model was generated that genetically inactivates PTEN in the smooth muscle through transgelin [Tagln; also known as smooth muscle 22-α (Sm22a)]-Cre activity (Hernando et al., 2007). Deletion of PTEN in the smooth muscle (Tagln-Cre; Ptenflox/flox) caused smooth muscle hyperplasia and a rapid onset of leiomyosarcoma in 80% of the mice. Both abdominal and retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas were detected, although no uterine sarcomas were observed. No tumors were found in skeletal or cardiac muscle, despite the transient expression of Cre in their precursor cells by the Tagln promoter.

A mouse model of ULMS was created using a Cre driver from the promoter of the anti-Mullerian hormone type II receptor (Amhr2) gene, which is expressed in tissues that develop into the fallopian tubes, female gonad, uterus and ovary (Xing et al., 2009). Deletion of p53 by using Amhr2-Cre resulted in ULMS in over half of the mice within 13 months. Loss of the tumor suppressor gene Brca1 accelerated formation of these tumors in the triple transgenic Brca1flox/flox; p53flox/flox; Ahmr2Cre/+ mice. Indeed, loss of BRCA1 protein expression was detected in about one-third of human ULMS samples (Xing et al., 2009).

Another mouse model of ULMS has been reported that utilizes the Wnt-activated growth factor Cripto-1 (CR-1). The CR-1 protein is strongly expressed in ∼70% of human leiomyosarcomas (Strizzi et al., 2007). A transgenic mouse driving CR-1 expression from the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) long-terminal-repeat promoter developed ULMSs in ∼20% of the females. These MMTV–CR-1 mice show activation of CR-1 and of Wnt signaling through elevated levels of phospho-Src, phospho-AKT and phospho-GSK-3β and nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. Interestingly, tumor formation did not require p53 loss, although deletion of p53 might increase the penetrance and tumor development in these mice. In an additional model, spontaneous ULMSs developed in mice deleted for LMP2, an IFN-γ-regulated proteosomal subunit. The LMP2−/− mice also developed hepatocellular carcinomas and lung tumors, albeit at a lower incidence than the ULMSs.

The promise of new therapies

The animal models of STS discussed above have been instrumental in our understanding of sarcomagenesis, including identification of relevant oncogenes, the cells of origin, and new therapies and treatments. These tools are crucial for the sarcoma field because clinical samples are relatively rare and treatment regimens have not changed in 30 years for many sarcoma subtypes. Several studies that highlight preclinical applications of these models are described below. The discussion presented here is by no means comprehensive, but is intended to emphasize current trends using such models.

In vivo screening of anti-sarcoma drugs is a major preclinical use for animal models. For example, the mTOR pathway is activated in leiomyosarcomas from Tagln-Cre; Ptenflox/flox mice, suggesting that these tumors might respond to mTOR inhibitors. Treatment with a rapamycin analog, Everolimus, beginning at 1 month of age significantly delayed tumor growth and extended survival in these mice (Hernando et al., 2007). Post-treatment tumors showed significant downregulation of both phospho-AKT and Ki67 staining. Similar studies have been completed in a model of GIST driven by KitV558Δ/+. Treatment with either the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib or Everolimus decreased GIST growth (Rossi et al., 2006). The faithful response of these tumors to the Kit inhibitors used in the clinic validates this model as a screening platform for future drug therapies. An additional model was used to study the synergistic effects between radiation therapy and treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib (SU) (Yoon et al., 2009). Using the Ad-Cre-driven model of UPS (Kirsch et al., 2007), the efficacy of radiation treatment was enhanced when administered in tandem with SU. This model was well-suited for such a study because changes in tumor volume in response to treatment can be easily measured because the location of the sarcoma was determined by the site of Ad-Cre injection.

Further understanding of the heterogeneity of subtypes of STSs will hasten the development of additional animal models. The ability of these models to faithfully recapitulate the spectrum of disease seen within these subtypes will provide vital mechanistic and therapeutic insights that will have a direct impact on sarcoma patients. Specific mouse models of STS might identify novel drug targets that have not been identified by the relatively small number of clinical samples available to investigators, similar to the successful identification of potential therapeutic targets using mouse primary-tumor models of Kras-driven lung cancers (Engelman et al., 2008).

Conclusion

Animal models are indispensable tools for the study of STSs because a paucity of clinical samples makes large-scale analysis of human samples challenging. Furthermore, the diversity of sarcoma subtypes complicates analyses of human sarcomas. Until recently, studies of sarcoma biology were limited to human cell lines and xenografted tumors. Using the sophisticated tools of mouse genetics, models of many oncogene-driven STSs have been developed. In these models, tumors develop in the native microenvironment of an animal that has an intact immune system. Many advances have been made in determining the signaling pathways activated in sarcomas and in identifying potential cells of origin within these models. The further development of models using advanced genetic techniques will continue to increase our understanding of STS biology. Additionally, preclinical studies of novel drug and radiation therapies will form the foundation for new treatment regimens. Ultimately, continued genomic study of human STS samples might identify novel genetic mutations that can guide the creation of new and even more faithful animal models.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Crose and members of the Kirsch lab for helpful discussions and critical reading of this Perspective. We apologize to authors whose work we could not discuss due to space limitations. This work is supported by a joint ACS-Canary Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (R.D.D.), and NIH grants T32-GM-07171 (J.K.M.) and RO1 CA 138265 (D.G.K.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Barr FG. (2001). Gene fusions involving PAX and FOX family members in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene 20, 5736–5746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman SD, Calo E, Landman AS, Danielian PS, Miller ES, West JC, Fonhoue BD, Caron A, Bronson R, Bouxsein ML, et al. (2008). Metastatic osteosarcoma induced by inactivation of Rb and p53 in the osteoblast lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 11851–11856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi M, Remppis A, Fredericks WJ, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Schafer BW. (1996). Induction of apoptosis in rhabdomyosarcoma cells through down-regulation of PAX proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 13164–13169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besmer P, Murphy JE, George PC, Qiu FH, Bergold PJ, Lederman L, Snyder HW, Jr, Brodeur D, Zuckerman EE, Hardy WD. (1986). A new acute transforming feline retrovirus and relationship of its oncogene v-kit with the protein kinase gene family. Nature 320, 415–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard-Guerin C, Newsham I, Winqvist R, Cavenee WK. (1996). A common region of loss of heterozygosity in Wilms’ tumor and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma distal to the D11S988 locus on chromosome 11p15.5. Hum Genet. 97, 163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden EC, Baker LH, Bell RS, Bramwell V, Demetri GD, Eisenberg BL, Fletcher CD, Fletcher JA, Ladanyi M, Meltzer P, et al. (2003). Soft tissue sarcomas of adults: state of the translational science. Clin Cancer Res. 9, 1941–1956 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cance WG, Brennan MF, Dudas ME, Huang CM, Cordon-Cardo C. (1990). Altered expression of the retinoblastoma gene product in human sarcomas. N Engl J Med. 323, 1457–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichowski K, Shih TS, Schmitt E, Santiago S, Reilly K, McLaughlin ME, Bronson RT, Jacks T. (1999). Mouse models of tumor development in neurofibromatosis type 1. Science 286, 2172–2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. (2006). Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 24–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dei Tos AP, Maestro R, Doglioni C, Piccinin S, Libera DD, Boiocchi M, Fletcher CD. (1996). Tumor suppressor genes and related molecules in leiomyosarcoma. Am J Pathol. 148, 1037–1045 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr, Butel JS, Bradley A. (1992). Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature 356, 215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driman D, Thorner PS, Greenberg ML, Chilton-MacNeill S, Squire J. (1994). MYCN gene amplification in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer 73, 2231–2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, Maira M, McNamara K, Perera SA, Song Y, et al. (2008). Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 14, 1351–1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom K, Willen H, Kabjorn-Gustafsson C, Andersson C, Olsson M, Goransson M, Jarnum S, Olofsson A, Warnhammar E, Aman P. (2006). The myxoid/round cell liposarcoma fusion oncogene FUS-DDIT3 and the normal DDIT3 induce a liposarcoma phenotype in transfected human fibrosarcoma cells. Am J Pathol. 168, 1642–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster A, Pannell R, Drynan LF, Codrington R, Daser A, Metzler M, Lobato MN, Rabbitts TH. (2005). The invertor knock-in conditional chromosomal translocation mimic. Nat Methods 2, 27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forus A, Florenes VA, Maelandsmo GM, Meltzer PS, Fodstad O, Myklebost O. (1993). Mapping of amplification units in the q13–14 region of chromosome 12 in human sarcomas: some amplica do not include MDM2. Cell Growth Differ. 4, 1065–1070 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks WJ, Ayyanathan K, Herlyn M, Friedman JR, Rauscher FJ., 3rd (2000). An engineered PAX3-KRAB transcriptional repressor inhibits the malignant phenotype of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cells harboring the endogenous PAX3-FKHR oncogene. Mol Cell Biol. 20, 5019–5031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furitsu T, Tsujimura T, Tono T, Ikeda H, Kitayama H, Koshimizu U, Sugahara H, Butterfield JH, Ashman LK, Kanayama Y, et al. (1993). Identification of mutations in the coding sequence of the proto-oncogene c-kit in a human mast cell leukemia cell line causing ligand-independent activation of c-kit product. J Clin Invest. 92, 1736–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Xie J, Rubin E, Tang YX, Lin F, Zi X, Hoang BH. (2008). Frzb, a secreted Wnt antagonist, decreases growth and invasiveness of fibrosarcoma cells associated with inhibition of Met signaling. Cancer Res. 68, 3350–3360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gura T. (1997). Systems for identifying new drugs are often faulty. Science 278, 1041–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar M, Hancock JD, Coffin CM, Lessnick SL, Capecchi MR. (2007). A conditional mouse model of synovial sarcoma: insights into a myogenic origin. Cancer Cell 11, 375–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar M, Randall RL, Capecchi MR. (2008). Synovial sarcoma: from genetics to genetic-based animal modeling. Clin Orthop. 466, 2156–2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar M, Hedberg ML, Hockin MF, Capecchi MR. (2009). A CreER-based random induction strategy for modeling translocation-associated sarcomas in mice. Cancer Res. 69, 3657–3664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helman LJ, Meltzer P. (2003). Mechanisms of sarcoma development. Nat Rev Cancer 3, 685–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernando E, Charytonowicz E, Dudas ME, Menendez S, Matushansky I, Mills J, Socci ND, Behrendt N, Ma L, Maki RG, et al. (2007). The AKT-mTOR pathway plays a critical role in the development of leiomyosarcomas. Nat Med. 13, 748–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S, Kawano K, Hanada M, Kurata A, Takeda M, et al. (1998). Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 279, 577–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J, Schmidt-Peter P, Hansch W, Naundorf H, Bunge A, Becker M, Fichtner I. (1999). Anticancer drug sensitivity and expression of multidrug resistance markers in early passage human sarcomas. Clin Cancer Res. 5, 2198–2204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H, Shimizu K, Hayashi Y, Ohki M. (1994). An RNA-binding protein gene, TLS/FUS, is fused to ERG in human myeloid leukemia with t(16;21) chromosomal translocation. Cancer Res. 54, 2865–2868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, Weinberg RA. (1994). Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 4, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, van der Gulden H, Peterse H, van der Valk M, Berns A. (2001). Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 29, 418–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, Bell GW, Richardson AL, Polyak K, Tubo R, Weinberg RA. (2007). Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature 449, 557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpeh MS, Brennan MF, Cance WG, Woodruff JM, Pollack D, Casper ES, Dudas ME, Latres E, Drobnjak M, Cordon-Cardo C. (1995). Altered patterns of retinoblastoma gene product expression in adult soft-tissue sarcomas. Br J Cancer 72, 986–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Hansen MS, Coffin CM, Capecchi MR. (2004a). Pax3:Fkhr interferes with embryonic Pax3 and Pax7 function: implications for alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell of origin. Genes Dev. 18, 2608–2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Arenkiel BR, Coffin CM, El-Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, Capecchi MR. (2004b). Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas in conditional Pax3:Fkhr mice: cooperativity of Ink4a/ARF and Trp53 loss of function. Genes Dev. 18, 2614–2626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan J, Bittner ML, Saal LH, Teichmann U, Azorsa DO, Gooden GC, Pavan WJ, Trent JM, Meltzer PS. (1999). cDNA microarrays detect activation of a myogenic transcription program by the PAX3-FKHR fusion oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 13264–13269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch DG, Dinulescu DM, Miller JB, Grimm J, Santiago PM, Young NP, Nielsen GP, Quade BJ, Chaber CJ, Schultz CP, et al. (2007). A spatially and temporally restricted mouse model of soft tissue sarcoma. Nat Med. 13, 992–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohashi K, Oda Y, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, Takahira T, Takahashi Y, Tajiri T, Taguchi T, Suita S, Tsuneyoshi M. (2008). Alterations of RB1 gene in embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: special reference to utility of pRB immunoreactivity in differential diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma subtype. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 134, 1097–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagutina I, Conway SJ, Sublett J, Grosveld GC. (2002). Pax3-FKHR knock-in mice show developmental aberrations but do not develop tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 22, 7204–7216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenau DM, Keefe MD, Storer NY, Guyon JR, Kutok JL, Le X, Goessling W, Neuberg DS, Kunkel LM, Zon LI. (2007). Effects of RAS on the genesis of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Genes Dev. 21, 1382–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessnick SL, Dacwag CS, Golub TR. (2002). The Ewing’s sarcoma oncoprotein EWS/FLI induces a p53-dependent growth arrest in primary human fibroblasts. Cancer Cell 1, 393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PP, Pandey MK, Jin F, Xiong S, Deavers M, Parant JM, Lozano G. (2008). EWS-FLI1 induces developmental abnormalities and accelerates sarcoma formation in a transgenic mouse model. Cancer Res. 68, 8968–8975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PP, Pandey MK, Jin F, Raymond AK, Akiyama H, Lozano G. (2009). Targeted mutation of p53 and Rb in mesenchymal cells of the limb bud produces sarcomas in mice. Carcinogenesis 30, 1789–1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardic CM, Downie DL, Qualman S, Bentley RC, Counter CM. (2005). Genetic modeling of human rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 65, 4490–4495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List K, Szabo R, Molinolo A, Sriuranpong V, Redeye V, Murdock T, Burke B, Nielsen BS, Gutkind JS, Bugge TH. (2005). Deregulated matriptase causes ras-independent multistage carcinogenesis and promotes ras-mediated malignant transformation. Genes Dev. 19, 1934–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meads MB, Gatenby RA, Dalton WS. (2009). Environment-mediated drug resistance: a major contributor to minimal residual disease. Nat Rev Cancer 9, 665–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlino G, Helman LJ. (1999). Rhabdomyosarcoma-working out the pathways. Oncogene 18, 5340–5348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mito JK, Riedel RF, Dodd L, Lahat G, Lazar AJ, Dodd RD, Stangenberg L, Eward WC, Hornicek FJ, Yoon SS, et al. (2009). Cross species genomic analysis identifies a mouse model as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma/malignant fibrous histiocytoma. PloS ONE 4, e8075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka H, Yabe H, Morii T, Yamada R, Kato S, Yuasa S, Yano T. (2001). In vitro chemosensitivity of human soft tissue sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 21, 4147–4151 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai M, Tanaka S, Tsuda M, Endo S, Kato H, Sonobe H, Minami A, Hiraga H, Nishihara H, Sawa H, et al. (2001). Analysis of transforming activity of human synovial sarcoma-associated chimeric protein SYT-SSX1 bound to chromatin remodeling factor hBRM/hSNF2 alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 3843–3848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni P, Nicoletti G, De Giovanni C, Croci S, Astolfi A, Landuzzi L, Di Carlo E, Iezzi M, Musiani P, Lollini PL. (2003). Development of rhabdomyosarcoma in HER-2/neu transgenic p53 mutant mice. Cancer Res. 63, 2728–2732 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijo K, Chen QR, Zhang L, McCleish AT, Rodriguez A, Cho MJ, Prajapati SI, Gelfond JA, Chisholm GB, Michalek JE, et al. (2009). Credentialing a preclinical mouse model of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 69, 2902–2911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordonez JL, Osuna D, Herrero D, de Alava E, Madoz-Gurpide J. (2009). Advances in Ewing’s sarcoma research: where are we now and what lies ahead? Cancer Res. 69, 7140–7150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen LA, Kowalewski AA, Lessnick SL. (2008). EWS/FLI mediates transcriptional repression via NKX2.2 during oncogenic transformation in Ewing’s sarcoma. PloS ONE 3, e1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Losada J, Pintado B, Gutierrez-Adan A, Flores T, Banares-Gonzalez B, del Campo JC, Martin-Martin JF, Battaner E, Sanchez-Garcia I. (2000). The chimeric FUS/TLS-CHOP fusion protein specifically induces liposarcomas in transgenic mice. Oncogene 19, 2413–2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Mancera PA, Sanchez-Garcia I. (2005). Understanding mesenchymal cancer: the liposarcoma-associated FUS-DDIT3 fusion gene as a model. Semin Cancer Biol. 15, 206–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Mancera PA, Perez-Losada J, Sanchez-Martin M, Rodriguez-Garcia MA, Flores T, Battaner E, Gutierrez-Adan A, Pintado B, Sanchez-Garcia I. (2002). Expression of the FUS domain restores liposarcoma development in CHOP transgenic mice. Oncogene 21, 1679–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Mancera PA, Vicente-Duenas C, Gonzalez-Herrero I, Sanchez-Martin M, Flores-Corral T, Sanchez-Garcia I. (2007). Fat-specific FUS-DDIT3-transgenic mice establish PPARgamma inactivation is required to liposarcoma development. Carcinogenesis 28, 2069–2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggi N, Cironi L, Provero P, Suva ML, Kaloulis K, Garcia-Echeverria C, Hoffmann F, Trumpp A, Stamenkovic I. (2005). Development of Ewing’s sarcoma from primary bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 65, 11459–11468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggi N, Cironi L, Provero P, Suva ML, Stehle JC, Baumer K, Guillou L, Stamenkovic I. (2006). Expression of the FUS-CHOP fusion protein in primary mesenchymal progenitor cells gives rise to a model of myxoid liposarcoma. Cancer Res. 66, 7016–7023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi F, Ehlers I, Agosti V, Socci ND, Viale A, Sommer G, Yozgat Y, Manova K, Antonescu CR, Besmer P. (2006). Oncogenic Kit signaling and therapeutic intervention in a mouse model of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 12843–12848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin BP, Antonescu CR, Scott-Browne JP, Comstock ML, Gu Y, Tanas MR, Ware CB, Woodell J. (2005). A knock-in mouse model of gastrointestinal stromal tumor harboring kit K641E. Cancer Res. 65, 6631–6639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sausville EA, Burger AM. (2006). Contributions of human tumor xenografts to anticancer drug development. Cancer Res. 66, 3351–3354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidler S, Fredericks WJ, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Barr FG, Vogt PK. (1996). The hybrid PAX3-FKHR fusion protein of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma transforms fibroblasts in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 9805–9809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal NH, Pavlidis P, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Noble WS, DeSantis D, Woodruff JM, Lewis JJ, Brennan MF, Houghton AN, et al. (2003). Classification and subtype prediction of adult soft tissue sarcoma by functional genomics. Am J Pathol. 163, 691–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp R, Recio JA, Jhappan C, Otsuka T, Liu S, Yu Y, Liu W, Anver M, Navid F, Helman LJ, et al. (2002). Synergism between INK4a/ARF inactivation and aberrant HGF/SF signaling in rhabdomyosarcomagenesis. Nat Med. 8, 1276–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer G, Agosti V, Ehlers I, Rossi F, Corbacioglu S, Farkas J, Moore M, Manova K, Antonescu CR, Besmer P. (2003). Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in a mouse model by targeted mutation of the Kit receptor tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 6706–6711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizzi L, Bianco C, Hirota M, Watanabe K, Mancino M, Hamada S, Raafat A, Lawson S, Ebert AD, D’Antonio A, et al. (2007). Development of leiomyosarcoma of the uterus in MMTV-CR-1 transgenic mice. J Pathol. 211, 36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Iwakuma T, Harimaya K, Sato H, Iwamoto Y. (1997). EWS-Fli1 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide inhibits proliferation of human Ewing’s sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor cells. J Clin Invest. 99, 239–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JG, 6th, Cheuk AT, Tsang PS, Chung JY, Song YK, Desai K, Yu Y, Chen QR, Shah K, Youngblood V, et al. (2009). Identification of FGFR4-activating mutations in human rhabdomyosarcomas that promote metastasis in xenotransplanted models. J Clin Invest. 119, 3395–3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirado OM, Mateo-Lozano S, Notario V. (2005). Roscovitine is an effective inducer of apoptosis of Ewing’s sarcoma family tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 65, 9320–9327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toft DJ, Rosenberg SB, Bergers G, Volpert O, Linzer DI. (2001). Reactivation of proliferin gene expression is associated with increased angiogenesis in a cell culture model of fibrosarcoma tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 13055–13059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchia EC, Boyd K, Rehg JE, Qu C, Baker SJ. (2007). EWS/FLI-1 induces rapid onset of myeloid/erythroid leukemia in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 27, 7918–7934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsumura H, Yoshida T, Saito H, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Suzuki N. (2006). Cooperation of oncogenic K-ras and p53 deficiency in pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma development in adult mice. Oncogene 25, 7673–7679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzukerman M, Rosenberg T, Reiter I, Ben-Eliezer S, Denkberg G, Coleman R, Reiter Y, Skorecki K. (2006). The influence of a human embryonic stem cell-derived microenvironment on targeting of human solid tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 66, 3792–3801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadayama B, Toguchida J, Shimizu T, Ishizaki K, Sasaki MS, Kotoura Y, Yamamuro T. (1994). Mutation spectrum of the retinoblastoma gene in osteosarcomas. Cancer Res. 54, 3042–3048 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkley CR, Qudsi R, Sankaran VG, Perry JA, Gostissa M, Roth SI, Rodda SJ, Snay E, Dunning P, Fahey FH, et al. (2008). Conditional mouse osteosarcoma, dependent on p53 loss and potentiated by loss of Rb, mimics the human disease. Genes Dev. 22, 1662–1676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing D, Scangas G, Nitta M, He L, Xu X, Ioffe YJ, Aspuria PJ, Hedvat CY, Anderson ML, Oliva E, et al. (2009). A role for BRCA1 in uterine leiomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 69, 8231–8235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying H, Biroc SL, Li WW, Alicke B, Xuan JA, Pagila R, Ohashi Y, Okada T, Kamata Y, Dinter H. (2006). The Rho kinase inhibitor fasudil inhibits tumor progression in human and rat tumor models. Mol Cancer Ther. 5, 2158–2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SS, Stangenberg L, Lee YJ, Rothrock C, Dreyfuss JM, Baek KH, Waterman PR, Nielsen GP, Weissleder R, Mahmood U, et al. (2009). Efficacy of sunitinib and radiotherapy in genetically engineered mouse model of soft-tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 74, 1207–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Hill RP. (2007). Hypoxia enhances metastatic efficiency in HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells by increasing cell survival in lungs, not cell adhesion and invasion. Cancer Res. 67, 7789–7797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]