Summary

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic human pathogen that can cause serious infection in those with deficient or impaired phagocytes. We have developed the optically transparent and genetically tractable zebrafish embryo as a model for systemic P. aeruginosa infection. Despite lacking adaptive immunity at this developmental stage, zebrafish embryos were highly resistant to P. aeruginosa infection, but as in humans, phagocyte depletion dramatically increased their susceptibility. The virulence of an attenuated P. aeruginosa strain lacking a functional Type III secretion system was restored upon phagocyte depletion, suggesting that this system influences virulence through its effects on phagocytes. Intravital imaging revealed bacterial interactions with multiple blood cell types. Neutrophils and macrophages rapidly phagocytosed and killed P. aeruginosa, suggesting that both cell types play a role in protection against infection. Intravascular aggregation of erythrocytes and other blood cells with resultant circulatory blockage was observed immediately upon infection, which may be relevant to the pathogenesis of thrombotic complications of human P. aeruginosa infections. The real-time visualization capabilities and genetic tractability of the zebrafish infection model should enable elucidation of molecular and cellular details of P. aeruginosa pathogenesis in conditions associated with neutropenia or impaired phagocyte function.

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is a ubiquitous Gram-negative bacterium that can infect a wide variety of plants and animals. It is an important opportunistic pathogen in humans, producing serious infections that can be localized or systemic depending on the clinical setting. Localized infections include keratitis, otitis externa, and most notably, chronic lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis, in which defective clearance of airway secretions and concomitant impairment of host phagocyte function creates a permissive environmental niche (Matsui et al., 2005; Knowles and Boucher, 2002; Lyczak et al., 2000). In contrast, acute systemic infection occurs principally in neutropenic hosts undergoing chemotherapy and in those with serious burns (Lyczak et al., 2000).

Because PA produces diverse disease, multiple animal models are useful to elucidate the factors and mechanisms of pathogenesis relevant to specific clinical settings. Murine models include corneal infection, burn-wound infection, and acute pneumonia and sepsis (Zolfaghar et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2005; Vance et al., 2005; Tang et al., 1995; Stevens et al., 1994). Genetically tractable invertebrate models such as Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm) and Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), as well as the plant model Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress), have also been developed to study PA virulence factors and pathogenesis (Lutter et al., 2008; Fauvarque et al., 2002; D'Argenio et al., 2001; Rahme et al., 2000; Darby et al., 1999; Mahajan-Miklos et al., 1999).

While several PA factors are required for virulence across these diverse models (Rahme et al., 2000), others appear to be important only in specific models and clinical contexts. One example is the PA Type III secretion system (T3SS), which translocates exotoxins into host cell cytoplasm and is associated with poor clinical outcomes in acute systemic infection and pneumonia (Lee et al., 2005; Hauser et al., 2002; Roy-Burman et al., 2001). The T3SS is a key virulence factor in Galleria mellonella (greater wax moth), fruit fly, and mouse, but not in roundworm or thale cress (Lee et al., 2005; Vance et al., 2005; Laskowski et al., 2004; Miyata et al., 2003; Fauvarque et al., 2002).

Danio rerio (zebrafish), perhaps best known as a model for investigating the cellular and genetic mechanisms of vertebrate development, is rapidly gaining favour as a model for the study of host-bacterial interactions (Clay et al., 2008; Prajsnar et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2007; Bates et al., 2006; Rawls et al., 2006; Pressley et al., 2005; van der Sar et al., 2003; Davis et al., 2002; Neely et al., 2002). Its genetic tractability and optical transparency early in development make it useful for studying aspects of infectious diseases not accessible in more traditional models. Moreover, while the adult zebrafish has a complex immune system similar to that of humans, with both innate and adaptive arms (Traver et al., 2003), at early developmental stages only innate immunity is operant, allowing for the dissection of innate and adaptive immune responses (Clay et al., 2008; Clay et al., 2007; Davis et al., 2002). Studies of zebrafish development have demonstrated that neutrophils and macrophages are present during this time (Le Guyader et al., 2008; Traver et al., 2003; Herbomel et al., 1999), and have shown the ability of these cells to phagocytose both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Prajsnar et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2007; Pressley et al., 2005; van der Sar et al., 2003; Neely et al., 2002).

In this study, we developed the zebrafish embryo as a model for the study of systemic PA infection, and examined the virulence of a PA T3SS mutant in this model. We used Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy to monitor PA infection in real time in transgenic zebrafish lines with fluorescent macrophages and neutrophils (Hall et al., 2007; Mathias et al., 2006). Finally, we defined the effects of phagocyte depletion on embryos during subsequent infection with wild-type and T3SS-deficient PA strains. Our results show that bacterial T3SS-phagocyte interactions are critical determinants of PA pathogenesis in this model, and suggest that macrophages as well as neutrophils provide protection against systemic PA infection.

Results

Zebrafish embryos are relatively resistant to intravenously injected PA

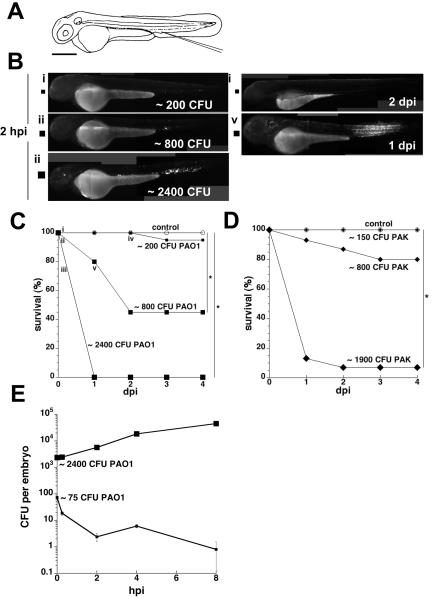

To determine the effects of introducing PA into the bloodstream, we microinjected a range of doses of two green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing laboratory strains (PAO1 and PAK) into the caudal vein of zebrafish embryos (Fig. 1A) at 50-52 hrs post fertilization (hpf), and assessed infected embryos for survival, and for bacterial burdens via serial fluorescence microscopy and quantitative plating (Volkman et al., 2004; van der Sar et al., 2003; Davis et al., 2002). The virulence of these PA strains has been demonstrated in other animal models of acute infection (Lutter et al., 2008; Tang et al., 1995). At two hrs post infection (hpi) the embryos displayed bacterial burdens that were proportional to the initial inoculum (Fig. 1Bi-iii). Embryos were resistant to 150-200 colony-forming units (CFU) of either strain; bacteria were invariably cleared within two days (Fig. 1Biv) with no embryo mortality (Fig. 1C-D; the sole 200-CFU-injected embryo that died in Fig. 1C contained no fluorescent bacteria, suggesting that its death was not a direct consequence of PA infection). Dose-dependent mortality was observed with larger inocula (∼800-2400 CFU per embryo) of either strain (Fig. 1C-D). While 2400 CFU of PAO1 was uniformly lethal by the first day post infection (dpi) (Fig. 1C), injection with an equivalent amount of heat-killed PAO1 produced no mortality (data not shown), indicating that live PA or heat-labile bacterial products, rather than heat-stable products such as endotoxin, mediated this effect. Infected embryos that survived the four-day observation period continued to develop normally thereafter and cleared the infection (data not shown). Thus, zebrafish embryo survival following infection with PA reflected a binary outcome at the individual embryo level (i.e., survival with bacterial clearance or death with rampant bacteraemia) that was superimposed on the graded dose-dependent mortality observed at the population level.

Figure 1. Effect of PA inoculum size on host survival and bacterial growth in zebrafish embryos.

Embryo survival and bacterial enumeration experiments were repeated at least three times; representative results are shown.

A. Diagram of a zebrafish embryo at 48 hpf. Injection site (at the axial vein near the urogenital opening) is as indicated. Scale bar, 300 μm.

B. Photomicrographs of embryos infected with GFP-labeled strain PAO1. Representative embryos that had been inoculated with a low dose (i, small square), intermediate dose (ii, medium square), or high dose (iii, large square) of this bacterial strain and imaged at two hpi are shown. A representative embryo that received the intermediate dose was highly infected at one dpi (v, medium square); it died by two dpi. With one exception, embryos receiving the low or intermediate dose that survived to two dpi had cleared the infection (iv, small square) and were indistinguishable from each other and the controls. Scale same as for panel A.

C. Embryo survival following infection with GFP-labeled strain PAO1. Groups of embryos (n = 20 each) were inoculated with a low dose (∼200 CFU per embryo, small squares), an intermediate dose (∼800 CFU per embryo, medium squares), or a high dose (∼2400 CFU per embryo, large squares) of bacteria at 50–52 hpf and monitored daily for survival over four days. Uninfected controls are shown as open circles. Roman numerals (i through v) correspond to photomicrographs (panel B) of representative embryos. There was an overall significant effect of inoculum size on mean survival during the first four days post-infection (p<0.0001). Pairwise comparisons showed no significant difference in mean survival for the 200 CFU group relative to the uninfected control group, but significant differences (indicated by *) in mean survival for the 800 and 2400 CFU groups relative to control (adjusted p-values of p=1.0, p<0.0001, and p<0.0001, respectively).

D. Embryo survival following infection with GFP-labeled strain PAK. Groups of embryos (n = 15 each) were inoculated with the indicated number of CFU per embryo (small, medium, and large diamonds) at 50—52 hpf and monitored daily for survival over 4 days. There was an overall significant effect of inoculum size on mean survival during the first four days post-infection (p<0.0001). Pairwise comparisons showed no significant differences in mean survival for the 150 CFU and 800 CFU groups relative to the uninfected control group (open circles), but a significant difference (indicated by *) in mean survival for the 1900 CFU group relative to control (adjusted p-values of p=1.0, p=0.185, and p<0.0001, respectively).

E. Enumeration of bacteria in PAO1-infected embryos. In experiments separate from the survival curves shown above, groups of embryos (n = 45 each) were inoculated with a low dose (∼75 CFU per embryo, small squares) or high dose (∼2400 CFU per embryo, large squares) of PAO1 at 50–52 hpf, then sorted into sub-pools for enumeration (n = 25 each) and monitoring of survival (n = 20 each). Error bars indicate standard deviation of CFU per embryo.

Embryos infected with 75 CFU of the PAO1 strain cleared 75% of the inoculum within 15 minutes and continued to clear the remaining bacteria, albeit at a slower rate, during the eight-hour observation period (Fig. 1E), confirming the microscopic analysis of fluorescent bacteria (Fig. 1Bi and data not shown). In contrast, embryos infected with 2400 CFU of PAO1 supported rapid bacterial growth (a 19-fold increase in CFU per embryo over eight hours; Fig. 1E), consistent with their increased mortality (Fig. 1C).

The PAK strain, when inoculated at 2200 CFU per embryo, also expanded rapidly (4-fold increase at eight hours) (Fig. 2A). However, in contrast to PAO1, this strain was cleared rapidly in the first two hours (78% of the inoculum of ∼ 2200 bacteria) before achieving rapid growth between four and eight hpi (doubling time, ∼60 minutes, compared to ∼40 minutes in log-phase nutrient broth culture), reflecting a 25-fold increase in CFU per embryo over this four-hour interval (Fig. 2A). The basis for the apparent differences in the initial clearance and subsequent growth of these PA strains, which were not compared within the same experiment, is not known.

Figure 2. Infection of zebrafish embryos with PAKexsA::Ω, a T3SS mutant.

Embryo survival and bacterial enumeration experiments were repeated at least three times; representative results are shown.

A. Enumeration of bacteria in PAK- and PAKexsA::Ω-infected embryos at 0.25—8 hpi. Two groups of embryos (n = 45 each) were inoculated with PAK (∼2200 CFU per embryo, solid diamonds) or PAKexsA::Ω (∼2500 CFU per embryo, open diamonds) at 50—52 hpf, then sorted into sub-pools for enumeration (n = 25 each) and monitoring of survival (n = 20 each). Note the initial rapid drop in CFU of PAK and PAKexsA::Ω. Error bars indicate standard deviation of CFU per embryo.

B. Attenuated virulence of a PAKexsA::Ω T3SS mutant. In a separate experiment, groups of 20 embryos were inoculated with a high dose of PAK (wild-type strain; ∼2200 CFU per embryo) or PAKexsA::Ω (T3SS mutant; ∼2400 CFU per embryo) at 50–52 hpf and monitored for survival over four days. There was an overall significant effect of bacterial strain on mean survival during the first four days post-infection (p<0.0001). Pairwise comparisons showed no significant difference in mean survival for the PAKexsA::Ω group relative to the uninfected control group, but a significant difference in mean survival for the wild-type PAK group relative to control (adjusted p-values of p=1.0 and p<0.0001, respectively).

These experiments show that zebrafish embryos can consistently clear PA doses of up to 200 CFU with minimal mortality, depending solely on innate immunity, whereas doses of >800 CFU result in rapid proliferation of the inoculum and are frequently fatal. While the initial kinetics of growth varied between the two strains examined, the overall growth of the strains within embryos and the resultant host mortality were remarkably consistent.

The PA T3SS is required for virulence in zebrafish embryos

We next assessed the role of the PA T3SS, a key virulence determinant in acute infection of humans as well as in mammalian infection models (Lee et al., 2005; Vance et al., 2005; Laskowski et al., 2004; Hauser et al., 2002; Roy-Burman et al., 2001), by comparing infection with PAK strains that had or lacked the T3SS. The T3SS mutant strain PAKexsA::Ω was cleared rapidly in the first four hours, identical to the parent PAK strain (Fig. 2A). However, its growth rate thereafter was quite different, increasing only 2.5 fold between four and eight hours, compared to the 25-fold increase seen with the parent strain (Fig. 2A). Consistent with these reduced bacterial burdens, 90% of embryos infected with 2400 CFU of PAKexsA::Ω were alive at four dpi, compared to survival at one dpi of only 30% of embryos infected with 2200 CFU of wild-type PAK (Fig. 2B). In a separate experiment in which embryos were initially infected with ∼2600 CFU of PAKexsA::Ω per embryo, the 95% of survivors at two dpi had nearly cleared the infection, with residual bacterial burdens of only 19 +/− 5 CFU per embryo. These experiments showed that the PA T3SS is a critical virulence determinant in the zebrafish embryo model impacting bacterial burdens and host survival.

PA infection causes blood cell aggregation and circulatory blockage

In microscopically monitoring live infected zebrafish, we observed that in contrast to Mycobacterium marinum and Salmonella arizonae (Davis et al., 2002), PA infection resulted in immediate accumulation of bacteria near the site of injection (Fig. 1Bii). Bacterial aggregates were also observed at sites adjacent to the caudal artery and vein (Fig. 3A and B). Detailed microscopy revealed that these aggregates contained both bacteria and blood cells (Fig. 3B-E). Among the cells present were erythrocytes and occasional infected phagocytes that completely occluded blood flow in the vessel (Fig. 3B and C; Movie S1). Although the duration of this phenomenon was dependent on the dose of injected PA, with aggregation typically resolved within minutes following low doses of PA but minimally if at all following higher doses, cellular aggregates also formed at anatomic sites with fewer bacteria, and appeared to result from adhesions between blood cells and the vascular endothelium (Fig. 3D and Movie S2). This cellular aggregation was observed upon injection of heat killed wild-type PA as well as live PAKexsA::Ω, but not following mock injections (data not shown).

Figure 3. Aggregation of blood cells after intravenous injection of PA.

A. Overview of embryo at 48 hpf showing locations of other panels in this figure.

B. Tail region of a zebrafish embryo 1-2 hours post injection with fluorescent PA. Highly fluorescent areas (white brackets) show bacterial aggregates in the vasculature containing many bacteria. Scale bar, 100μm.

C. PA-infected macrophage (white arrow) within the caudal artery (ca). The artery is devoid of other blood cells due to the upstream cellular aggregates (black dashed box/arrows). nc = notochord; cht = caudal haematopoietic tissue. Scale bar, 20μm. See Movie S1.

D. Aggregated blood cells in the yolk circulation valley of the same embryo. White arrowheads indicate locations of fluorescent bacteria. Long dashed arrow shows blood flow past aggregation. Dashed box indicates area shown in panel E. Scale bar, 20μm. See Movie S2.

E. Fluorescent PA (white arrowheads) present as indicated in panel D. Scale bar, 20μm.

Both neutrophils and macrophages rapidly phagocytose and kill PA

Our initial results suggested that zebrafish embryos are similar to humans in their capacity to clear systemic PA infection solely through innate immunity. In humans and other mammals, neutrophils are known to provide critical protection against PA infection, although macrophages may also be involved (McClellan et al., 2003; Cheung et al., 2000; Lyczak et al., 2000; Tang et al., 1995). The zebrafish embryo has functional neutrophils and macrophages (Clay et al., 2008; Le Guyader et al., 2008; Clay et al., 2007; Herbomel et al., 1999), and DIC microscopy suggested that some bacteria could be phagocytosed early in infection by macrophages as judged by their distinctive morphological characteristics (Fig. 3C and Movie S1) (Le Guyader et al., 2008). To identify types of phagocytes interacting with PA, we took advantage of two transgenic zebrafish lines that label neutrophils. In the Tg(lyz:EGFP)nz117 line, the lysozyme (lyz) gene promoter drives expression of enhanced GFP in neutrophils and macrophages early in development (Hall et al., 2007), but is expressed almost exclusively in neutrophils starting at 48 hpf (C. Hall, J. Davis, L. Ramakrishnan, and P. Crosier, unpublished results). Similarly, in the Tg(mpx:GFP)uwm1 line, the myeloperoxidase (mpx) gene promoter drives neutrophil-specific expression of enhanced GFP (Mathias et al., 2006).

We injected these green fluorescent transgenic strains with red fluorescent protein-expressing strains of PA. Tg(lyz:EGFP)-expressing cells were seen to phagocytose a substantial proportion of the bacteria within two hours of infection (Fig. 4A and B, and data not shown). Similarly, using embryos of the Tg(mpx:GFP)uwm1 zebrafish line, we observed co-localization of bacteria with GFP-bright phagocytes (neutrophils) and with non-fluorescent phagocytes (Fig. 4C and Movie S3); the latter were confirmed as macrophages by morphology based on motility, phagocytic capacity, and lack of cytoplasmic granules (Davis et al., 2002; Herbomel et al., 1999). At two hpi, most bacteria were intracellular and had been phagocytosed by neutrophils and macrophages (Fig. 4D and E; Movie S3). Moreover, a substantial number of bacteria had been degraded even within this short time, as indicated by the presence of red debris without clear bacterial morphology within some phagocytes (Fig. 4B, E, and F). Both intact PA and degraded remnants were seen within vacuole-shaped compartments in phagocytes, often corresponding to the DIC appearance of bacteria (Fig. 4B and D-F). We did not observe any differences in the phagocytosis of the PAKexsA::Ω T3SS mutant as compared to the PAK or PAO1 wild-type strains within transgenic zebrafish embryos at two hpi (data not shown). These data show that neutrophils and macrophages can rapidly phagocytose and destroy PA.

Figure 4. PA infection of Tg(lyz:EGFP)nz117 and Tg(mpx:GFP)uwm1 lines.

A-B, Tg(lyz:EGFP)nz117 embryo injected with mCherry-expressing PA. Left, green channel (EGFP), center, red channel (PA), and overlay (right).

A. Typical projected z-series images of a Tg(lyz:EGFP)nz117 embryo inoculated with ∼1400 CFU per embryo of strain PAK, taken at two hpi. Box represents region shown in panel B; scale bar = 50 μm.

B. Close-up of Tg(lyz:EGFP)-positive cells that have phagocytosed PA. Arrowheads indicate bacteria in phagocytes. Arrow, digested bacteria. Scale bar = 10 μm.

C-F, Tg(mpx:GFP)uwm1 embryos (green channel, left) injected with mCherry-expressing PA (red channel, center), with DIC overlay of merged channels (right).

C. Typical projected z-series images of the ventral tail of an embryo that had been inoculated with ∼200 CFU per embryo of mCherry-expressing strain PAK, taken at two hpi. Scale bar, 50μm. See Movie S3.

D. Tg(mpx:GFP)-expressing cell with intact PA, at two hpi. The embryo had been inoculated with ∼600 CFU per embryo of mCherry-expressing strain PAO1. Arrowheads indicate intact bacteria within or adhered to the cell. Scale bar, 10μm.

E. Tg(mpx:GFP)-negative cell containing intact and digested PA, at two hpi. The embryo had been inoculated with ∼1000 CFU per embryo of mCherry-expressing strain PAK. Arrowheads indicate intact bacteria. Arrow, pool of red fluorescence presumably from mCherry released by killed PA. Scale bar, 10μm.

F. Tg(mpx:GFP)-expressing cell with vacuole containing released mCherry as in panel D (white arrow), and second vacuole containing only faint red fluorescence (black arrow), presumably after near-complete digestion of PA, at two hpi. The embryo had been inoculated with ∼800 CFU per embryo of mCherry-expressing strain PAKexsA::Ω. Scale bar, 10μm.

Phagocyte depletion renders zebrafish embryos hypersusceptible to PA infection and restores the virulence of the attenuated T3SS mutant

The differentiation and growth of macrophages and neutrophils in the developing zebrafish embryo are dependent on the myeloid transcription factor gene pu.1 (Clay et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2005). To explore the functional relevance of phagocytes to interactions between PA and host cells, we depleted phagocytes from embryos by injection of a modified antisense oligonucleotide (morpholino) directed against pu.1, creating embryos we refer to as pu.1 morphants. The pu.1 morphants succumbed rapidly to infection when injected with ∼383 CFU PAK, with 65% surviving as compared to 100% of control embryos at one dpi (Fig. 5A); one infected control embryo (5%) died on the second day. In contrast, similar to previous studies (Clay et al., 2007), 95% of uninfected pu.1 morphant embryos (n = 21) survived the four-day observation period. Control morpholino-treated embryos and untreated embryos were found to respond identically to infection (data not shown), thus only untreated embryos were used as controls in subsequent experiments. These results show that phagocytes play a critical role in protection of zebrafish embryos against PA infection; however the relative role of macrophages and neutrophils could not be discerned as both cell types are depleted with this morpholino (Clay et al., 2007).

Figure 5. Infection of pu.1 morphant zebrafish embryos with PAK or PAKexsA::Ω, a T3SS mutant.

A. pu.1 morphant embryos are hypersusceptible to infection with the wild-type PAK strain. Groups of pu.1 morphant (solid diamonds) and control non-morpholino-treated (solid squares) embryos (n = 20 each) were infected with PAK (∼383 CFU per embryo) at 50-52 hpf and monitored for survival over four days. At 1 dpi only 65% of the pu.1 morphants survived, compared to 100% of the controls. The effect of group on mean survival during the first four days post-infection was significant (p=0.01).

B. The attenuated virulence of the PAKexsA::Ω T3SS mutant is restored in pu.1 morphant embryos. Groups of pu.1 morphant (open diamonds) and control (open squares) embryos (n = 20 each) were infected with PAKexsA::Ω (∼384 CFU per embryo) at 50-52 hpf and monitored for survival over four days. At 1 dpi and 2 dpi, 65% and 60% of the pu.1 morphant embryos survived, compared to 100% of the infected control group. The effect of group on mean survival during the first four days post-infection was significant (p=0.001).

C. Enumeration of bacteria in PAK- and PAKexsA::Ω-infected pu.1 morphant and control embryos at 8 and 24 hpi. Two groups of pu.1 morphant embryos (n = 10 each) were inoculated with PAK (∼383 CFU per embryo, solid diamonds) or PAKexsA::Ω (∼384 CFU per embryo, open diamonds) at 50—52 hpf. A group of control embryos (n = 10) was inoculated with PAKexsA::Ω (∼384 CFU per embryo, open squares) at 50—52 hpf. Note the initial drop in CFU of PAKexsA::Ω in control but not pu.1 morphant embryos at 8 hpi, and the subsequent drop in CFU in pu.1 morphant embryos surviving at 24 hpi. Error bars indicate standard deviation of CFU per embryo.

Given the attenuation of the T3SS mutant in wild-type embryos, we next examined whether this bacterial determinant was involved in the phagocyte-pathogen interaction. We found that whereas ∼2400 CFU of PAKexsA::Ω had failed to kill wild-type embryos (Fig. 2B), doses of this strain as small as ∼384 CFU per pu.1 morphant embryo caused mortality equivalent to that of wild-type PAK; only 65% of pu.1 embryos survived at one dpi, as compared to 100% of control embryos (Fig. 5B). The finding that phagocyte depletion restored the virulence of a T3SS mutant suggests that the T3SS acts to protect wild-type PA against phagocytes.

Consistent with this decreased survival of PA-infected pu.1 morphants, by eight hpi bacterial counts in the PAK-infected pu.1 morphants had increased to 1173% of the original inoculum, while control embryos had essentially cleared the infection, with only 2% of the orignal inoculum remaining (Fig. 5C). Bacterial counts in the PAKexsA::Ω-infected pu.1 morphants also increased over this interval, but to only 280% of the inoculum, one-fourth that of the wild-type strain. The finding that the attenuated T3SS mutant still exhibited a relative in vivo growth defect after phagocyte depletion could be due to increased killing of the mutant bacteria by the small number of residual neutrophils in the pu.1 morphants (Clay et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2005), or because phagocytes are not the sole targets of the PA T3SS.

Discussion

This work suggests that the zebrafish embryo is a relevant and tractable model for the study of systemic PA infections in the neutropenic host, allowing for live examination of bacterial interactions with different blood cell types. PA rarely causes systemic infection of humans unless they are neutropenic or have had a substantial integumentary breach as in the case of severe burns (Lyczak et al., 2000). Similarly, we have found the zebrafish embryo to be remarkably resistant to PA infection, requiring >2000 CFU of intravenously injected bacteria to produce sustained infection and consistent mortality. This stands in sharp contrast to the low infectious inoculum of <10 CFU of M. marinum or S. arizonae in this model (van der Sar et al., 2003; Davis et al., 2002). Yet PA is relatively pathogenic when compared to non-pathogenic laboratory strains of bacteria such as Escherichia coli K12 or Bacillus subtilis, which are rapidly eradicated by zebrafish embryos (Herbomel et al., 1999). Together, these data indicate that zebrafish embryos possess effective defence mechanisms against systemic PA infection that depend solely on innate immunity. This modest degree of virulence in the zebrafish embryo model is consistent with the reputation of PA as an opportunistic pathogen of humans (Lyczak et al., 2000).

Further validation of this model comes from our finding that key host (phagocyte) and bacterial (T3SS) determinants in systemic PA infection of humans (Hauser et al., 2002; Roy-Burman et al., 2001; Lyczak et al., 2000) also play essential roles in zebrafish pathogenesis. Genetic ablation of the bacterial T3SS attenuated bacterial virulence, while phagocyte depletion rendered this host more susceptible to PA infection. Importantly, this work has directly demonstrated the central role of the bacterial T3SS-phagocyte interaction in determining the outcome of PA infection in vivo, as has been previously suggested through in vitro studies (Vance et al., 2005; Dacheux et al., 2000; Coburn and Frank, 1999). The first effect of Type III secretion in this infection model was observed between four and eight hpi, when the PAK strain (but not a T3SS mutant) began to grow rapidly despite an initial phase of bacterial clearance. Our data suggest that if the initial inoculum exceeds the phagocytic capacity of the host such that sufficient numbers of bacteria survive the initial burst of clearance, induction of T3SS expression in the surviving bacteria results in resistance to phagocytes, bacterial growth, and host mortality. This scenario may occur in severe neutropenia when a relatively small inoculum of PA may exceed the capacity of the few phagocytes present and thus initiate an acute systemic infection.

Previous work in a neonatal mouse model of acute pulmonary infection suggested that of the PA strains used in this study, PAK is somewhat more virulent than PAO1 (Tang et al., 1995). In contrast, recent findings in fruit fly models of systemic and intestinal infection suggest that these strains possess similar virulence (Lutter et al., 2008). Our results indicate that both strains are virulent in zebrafish embryos, but do not permit definitive determination of their relative virulence. Both possess three known Type III secreted exotoxins (ExoS, ExoT, and ExoY) but lack a fourth exotoxin (ExoU) that confers cytotoxicity (Ichikawa et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2005; Vance et al., 2005; Finck-Barbancon et al., 1997). The biochemical functions and virulence effects of these exotoxins suggest multiple mechanisms for affecting phagocyte function. In addition to their ADP-ribosyltransferase activity, the bifunctional exotoxins ExoS and ExoT are also GTPase-activating proteins that target Rho-like GTPases essential for receptor-mediated phagocytosis; ExoT additionally targets CrkI and CrkII, host kinases involved in cell adhesion and phagocytosis (Sun and Barbieri, 2003; Goehring et al., 1999; Caron and Hall, 1998). The adenylate cyclase activity of ExoY has not been shown to have a significant virulence effect in vivo (Vance et al., 2005); nonetheless, considering that it causes rounding of CHO cells, it could conceivably inhibit phagocyte microbicidal mechanisms (Yahr et al., 1998). Yet, how these effectors act in vivo is not entirely clear, with conflicting data from different animal models and bacterial strains. In combination these exotoxins exert complex synergistic effects on the transcriptional responses of cultured pneumocytes (Ichikawa et al., 2005), but separable and largely non-synergistic effects on virulence in a mouse model of acute pneumonia (Shaver and Hauser, 2006). Activation of the T3SS and ExoS-dependent inhibition of haemocyte phagocytic function characterizes acute PA infection of fruit fly (Avet-Rochex et al., 2005; Fauvarque et al., 2002); in contrast, inhibition of phagocytosis during in vitro PA infection of a murine macrophage-like cell line is ExoT-dependent (Garrity-Ryan et al., 2000). Moreover, the PAO1 strain, the T3SS of which was not tested in the present study, is known to secrete much less ExoS protein in vitro than does the PAK strain (Frank et al., 1994), potentially explaining observations indicating that the T3SS-mediated virulence of these strains depend on different combinations of effectors (Lee et al., 2005; Vance et al., 2005).

However, PA strains lacking ExoS, ExoU, or even all known Type III effector proteins can kill murine macrophages, with lysis requiring only the presence of a functional Type III translocase (Vance et al., 2005; Dacheux et al., 2000; Coburn and Frank, 1999). Type III effectors are important for systemic spread and survival in blood in a cyclophosphamide-induced leukopenic mouse model of competitive PA infection, but host defences can nonetheless clear PA T3SS mutants from the blood of these mice even after use of a neutrophil-specific monoclonal antibody to induce absolute neutropenia (Vance et al., 2005). In contrast, we observed that depletion of phagocytes in zebrafish embryos markedly hindered the clearance of a PA T3SS mutant. The distinct behaviour of PA T3SS mutants in these models may be attributable to residual macrophages or lymphocytes in the neutropenic mouse. The dramatic dependence of PA on the T3SS to overcome normal phagocyte defences in the absence of adaptive immunity suggests that the zebrafish may be a useful and relevant model to understand the details of T3SS-phagocyte interactions.

A central advantage of the zebrafish embryo model is the ability to monitor infection at a detailed cellular level in real-time. Using detailed microscopy of infected embryos, we have made two potentially important observations regarding pathogenesis. First, we confirmed previous observations that both neutrophils and macrophages are capable of phagocytosing and killing of PA (Tang et al., 1995). Indeed, the numbers of each cell type seen to interact with bacteria in this model seemed roughly proportional to their numbers in the caudal haematopoietic tissue, close to the injection site (Murayama et al., 2006). Thus, the relative role of the two cell types in PA phagocytosis and killing may simply be a function of their relative numbers. The greater prominence of neutrophils in acute bactericidal responses in humans may largely reflect their greater abundance in the circulation and more rapid accumulation at sites of acute inflammation (Stossel and Babior, 2003).

Alternatively, macrophages may play a more general role in phagocytosis in zebrafish embryos than in adult mammals. However, this seems unlikely given that embryonic and adult macrophages are similar with respect to production of cytokines, cell surface receptors, and the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthetase (Clay et al., 2008; Clay et al., 2007; Herbomel et al., 1999). Also, zebrafish embryonic macrophages have distinct interactions with different pathogens that parallel those of mammalian macrophages. For example, embryonic macrophages challenged with M. marinum form epithelioid granulomas, but are most likely to undergo pyroptosis upon phagocytosis of S. arizonae (Clay et al., 2007; Fink and Cookson, 2005; Davis et al., 2002). These responses are clearly distinct from the pattern of phagocytosis and digestion that occurs in response to PA, and all three pathogen-specific responses are similar to the corresponding macrophage-pathogen interactions observed in adult mammals, suggesting that embryonic and adult macrophages function similarly across a wide range of vertebrate organisms.

Our finding that embryonic zebrafish neutrophils can phagocytose and kill PA suggests that they are functionally competent even at this early developmental stage. Recent studies examining interactions of embryonic neutrophils with bacteria have shown that while they are capable of chemotactic attraction to infection sites, they do not phagocytose or kill non-pathogenic E. coli as efficiently as macrophages do (Le Guyader et al., 2008), and do not associate with mycobacteria (Clay et al., 2007). However, in zebrafish embryos as in adults, these phagocytic functions are pathogen-specific, since in addition to our observations related to PA, others have recently shown that both embryonic neutrophils and macrophages efficiently phagocytose Staphylococcus aureus in an acute systemic infection model (Prajsnar et al., 2008). As with PA, resistance of zebrafish embryos to S. aureus is myeloid cell dependent, since phagocyte depletion with pu.1 morpholino render embryos much more susceptible to systemic infection with S. aureus wild-type strains and restore the virulence of attenuated mutants of this opportunistic pathogen (Prajsnar et al., 2008).

Our real-time observations of PA-infected zebrafish embryos also revealed an erythroid aggregation phenomenon that appears to be transient at lower doses. We have not observed this phenomenon in either S. arizonae or M. marinum infection, suggesting that it is specific to certain bacteria, including PA. The consistent occurrence of this phenomenon intrigued us, because thrombotic complications are associated with PA infections in humans (Gupta et al., 1993). While these cellular aggregates are comprised principally of erythrocytes and proerythroblasts, we also noted the presence of phagocytes within them. However, these aggregates formed even in pu.1-depleted embryos (data not shown), suggesting that phagocytes may be bystander cells trapped within what is fundamentally a PA-erythrocyte interaction. Several features of these cellular aggregates are noteworthy. While they are entirely infection-dependent, the number of bacteria present within any given aggregate may be minimal. Second, they occur even in the absence of the T3SS and can be induced by heat-killed bacteria, suggesting that they are not the result of the heat-labile PA phospholipase C that has been reported to induce platelet aggregation in vitro (Coutinho et al., 1988). Host and bacterial mutational analyses similar to ones that we performed to investigate T3SS-phagocyte interactions in this model could determine what role, if any, these cellular aggregates play in pathogenesis.

Various animal and plant models have been used to study host-pathogen interactions in acute PA infection. Interestingly, the T3SS is an important virulence factor of PA in hosts that possess professional phagocytes, such as vertebrates and insects, but not in those that lack such cells, such as worms and plants (Alper et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2005; Vance et al., 2005; Laskowski et al., 2004; Miyata et al., 2003; Fauvarque et al., 2002). The fruit fly has been used to examine the role of T3SS in lethal PA infection and modulation of haemocyte function (Avet-Rochex et al., 2005; Fauvarque et al., 2002; D'Argenio et al., 2001), and the greater wax moth caterpillar has similarly been used to demonstrate redundancy of ExoT and ExoU and dispensability of ExoY with respect to virulence in this host (Miyata et al., 2003). Advantages of these and other invertebrate models are the feasibility of using large numbers of animals for each test condition, the relative ease of infection, and well-established techniques for genetic manipulation and screening to identify host defence factors. However, these invertebrates have relatively rudimentary innate immune systems that rely heavily on antimicrobial peptide expression as controlled through Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent signaling cascades (Tanji and Ip, 2005). Given the fundamental nature of such innate immune mediators and the presence of homologues in fish and mammals (van der Sar et al., 2006; Barton and Medzhitov, 2002), invertebrate models can provide important insights into host-pathogen interactions in vertebrates, but the zebrafish embryo model of innate immune interactions with PA should provide more accurate simulation of human infection.

In summary, we have developed the zebrafish as a valid and tractable model of acute PA infection. This model provides useful tools for exploring the detailed interactions of PA with the vertebrate immune system. Experimental tools that are becoming available for zebrafish will further enhance the direct visualization and detailed analysis of innate immune responses to PA infection that this model enables. Because the zebrafish is genetically tractable, screens for mutants with aberrant responses to PA infection should be feasible. Also, the amenability of zebrafish to small molecule screens should allow for discovery of drugs with anti-pseudomonal activity in the context of a whole vertebrate animal (Peterson et al., 2000). On the pathogen side, this model should enable investigators to define additional factors that influence PA virulence through the use of PA clinical isolates and mutant libraries. The use of PA strains containing translational fusions of Type III effectors or transcriptional fusions of specific regulatory sequences to fluorescent protein genes (Pederson et al., 2002) should also enable investigators to define cellular targets of Type III secretion and anatomic regions of regulated PA gene expression within the host. Such experimental approaches are expected to provide a richly detailed picture of host-pathogen interactions in vertebrate PA infection.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and culture methods

PA strains used in this study were PAO1 (Ochsner laboratory strain), kindly provided by E. P. Greenberg, University of Washington, PAK, and PAKexsA::Ω, both kindly provided by D. Frank, Medical College of Wisconsin (Frank et al., 1994). To confer constitutive expression of GFP or red fluorescent protein (RFP), each strain was transformed with plasmid pMF230, containing the GFPmut2 gene and a carbenicillin resistance marker, kindly provided by M. Franklin, Montana State University, Bozeman (Nivens et al., 2001), or plasmid pMKB1::mCherry, a derivative of pMF230 constructed by replacing the GFPmut2 gene with the mCherry RFP gene, kindly provided by R. Tsien, University of California San Diego (Shu et al., 2006). To obtain log-phase bacteria for injection, single colonies of each strain were inoculated into Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with 200 mg/L carbenicillin, grown overnight at 37°C, subcultured 1:100 in the same medium, and grown at 37°C to an optical density reading at 600 nm of 0.6 – 0.7. To prepare the final inoculum, 1 mL of cultured bacteria was pelleted by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 5 minutes, resuspended in 0.4 mL of 1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then diluted in additional 1x PBS as needed to achieve the desired bacterial density. To heat-kill bacteria, 20-μl aliquots were incubated in a 50°C water bath for 30 minutes. Phenol red tracking dye (5% solution) was added to bacterial aliquots (1:20 vol / vol) prior to injection. To enumerate CFU in the inoculum before, during, and after microinjection of each set of embryos, aliquots of the inoculum were spread on LB-agar plates containing 200 mg/L carbenicillin and incubated overnight at 37°C.

Maintenance, manipulation, and infection of zebrafish embryos

Zebrafish were maintained and handled as described (Volkman et al., 2004; Davis et al., 2002). Animal protocols for this study were compliant with laboratory standards outlined by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Zebrafish embryos used in these experiments included wild-type strain AB, as well as strain AB carrying the myelomonocyte-specific transgenic marker Tg(lyz:EGFP) as a transcriptional fusion (Hall et al., 2007), and strain AB carrying the neutrophil-specific transgenic marker Tg(mpx:GFP) as a transcriptional fusion (Mathias et al., 2006). Embryos were harvested at 3 hpf and incubated overnight in fish water containing 0.01% methylene blue. At 24 hpf, embryos were dechorionated and sorted in fish water containing 0.003% phenylthiourea to prevent melanization. At 50–52 hpf, groups of 15–20 embryos were anesthetized in 0.1% 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (tricaine), placed in a depression slide, and microinjected into the axial vein near the urogenital opening. For morpholino experiments, zygotes at the 1–2 cell stage were treated with pu.1 or control morpholino using previously described concentrations and methods (Clay et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2005). Morpholino-treated embryos were then infected as described above.

Microscopy of embryos

Microscopy was performed on a Nikon E600 (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with DIC optics, a Nikon D-FL-E fluorescence unit with a 100-watt mercury lamp, and an MFC-1000 z-step controller (Applied Scientific Instrumentation). Objectives used included 4x Plan Fluor (0.13 NA), 10x Plan Fluor (0.3 NA), 20x Plan Fluor (0.5 NA), 40x Plan Fluor (0.75 NA), and 60x Water Fluor (1.0 NA). Wide-field fluorescence and DIC images were captured on a Photometrics CoolSnap HQ CCD camera (Roper Scientific, Trenton, NJ) using MetaMorph 7.1 image acquisition software (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA).

Image processing

Where indicated, z-stacks were deconvolved using AutoDeblur Gold CWF, Version X1.4.1 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD), with default settings for blind deconvolution. Dataset analysis and visualization was performed using MetaMorph 7.1 and Imaris x64 6.0 (Bitplane, Inc., Zurich, Switzerland). Figure processing and assembly was performed using MetaMorph 7.1 and Adobe Photoshop CS2.

Determination of whole embryo bacterial counts

Infected embryos were randomly assigned to one of two sub-pools: an enumeration sub-pool and a survival monitoring sub-pool. At each time point from 0 to 48 hpi, groups of five embryos were randomly removed from the enumeration sub-pool, rinsed in 1x PBS, anesthetized in tricaine, placed in 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes containing 100 μl of 1x PBS with 1% Triton X-100, and homogenized together for 1–2 minutes with a sterile micropestle (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY). This homogenate was diluted in 1x PBS based on expected CFU, spread in triplicate on LB-agar plates containing 200 mg/L carbenicillin, and incubated overnight at 37°C. The mean value of triplicate counts for each group of five embryos was expressed as the mean (+/− standard deviation) bacterial count per embryo.

Statistical methods

For selected experiments, groups of zebrafish embryos were compared with respect to mean number of days alive, restricted to the first four dpi. In instances where subsequent pair-wise comparisons between experimental and control groups were performed, the resulting p-values were adjusted for multiple comparison testing using the Bonferroni method. For all analyses, embryos that were alive on a given day but no longer alive the following day were assumed to have died at the midpoint between days (e.g. embryos alive on day 2 but no longer alive on day 3 were assigned a value of 2.5 for number of days alive).

Supplementary Material

Infected macrophage within the clogged caudal artery, corresponding to Fig. 3C. A PA-infected macrophage (center) moves within the caudal artery towards an infected cellular aggregate (left) that is clogging the vessel. Scale bar, 20μm.

Cellular aggregate within the yolk circulation valley, corresponding to Fig. 3D. An aggregation of erythroid cells and occasional macrophages remains in place while blood flow continues adjacent to it. Scale bar, 20μm.

Uptake of PA by Tg(mpx:GFP)-positive neutrophils shortly after infection, corresponding to Fig. 4C. In this three-dimensional perspective, mpx expression is shown in green. Extracellular bacteria are rendered in white, bacteria inside GFP-bright cells (neutrophils) are pink, and bacteria inside GFP-dim cells (macrophages) are red. Scale grid, 10μm.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hilary Clay for first finding the susceptibility of pu.1 morphants to PA, David Tobin, Hannah Volkman, and Heather Wiedenhoft for help and advice with fish handling and microscopy, and Jane Burns for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to S.M.M. (R01 AI067653), L.R. (R01 AI054503), and A.H. (R01 GM074827), a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Award to L.R., a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship to J.M.D., and a grant from the New Economy Research Fund (Foundation for Research Science and Technology, New Zealand) to P.S.C.

References

- Alper S, McBride SJ, Lackford B, Freedman JH, Schwartz DA. Specificity and complexity of the Caenorhabditis elegans innate immune response. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5544–5553. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02070-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avet-Rochex A, Bergeret E, Attree I, Meister M, Fauvarque MO. Suppression of Drosophila cellular immunity by directed expression of the ExoS toxin GAP domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:799–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and their ligands. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;270:81–92. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59430-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JM, Mittge E, Kuhlman J, Baden KN, Cheesman SE, Guillemin K. Distinct signals from the microbiota promote different aspects of zebrafish gut differentiation. Dev Biol. 2006;297:374–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E, Hall A. Identification of two distinct mechanisms of phagocytosis controlled by different Rho GTPases. Science. 1998;282:1717–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung DO, Halsey K, Speert DP. Role of pulmonary alveolar macrophages in defense of the lung against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4585–4592. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4585-4592.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay H, Volkman HE, Ramakrishnan L. Tumor necrosis factor signaling mediates resistance to mycobacteria by inhibiting bacterial growth and macrophage death. Immunity. 2008;29:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay H, Davis JM, Beery D, Huttenlocher A, Lyons SE, Ramakrishnan L. Dichotomous role of the macrophage in early Mycobacterium marinum infection of the zebrafish. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn J, Frank DW. Macrophages and epithelial cells respond differently to the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3151–3154. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3151-3154.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho IR, Berk RS, Mammen E. Platelet aggregation by a phospholipase C from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Thromb Res. 1988;51:495–505. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(88)90115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Argenio DA, Gallagher LA, Berg CA, Manoil C. Drosophila as a model host for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1466–1471. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1466-1471.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacheux D, Toussaint B, Richard M, Brochier G, Croize J, Attree I. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates induce rapid, type III secretion-dependent, but ExoU-independent, oncosis of macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2916–2924. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2916-2924.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby C, Cosma CL, Thomas JH, Manoil C. Lethal paralysis of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15202–15207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Clay H, Lewis JL, Ghori N, Herbomel P, Ramakrishnan L. Real-time visualization of mycobacterium-macrophage interactions leading to initiation of granuloma formation in zebrafish embryos. Immunity. 2002;17:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauvarque MO, Bergeret E, Chabert J, Dacheux D, Satre M, Attree I. Role and activation of type III secretion system genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced Drosophila killing. Microb Pathog. 2002;32:287–295. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2002.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finck-Barbancon V, Goranson J, Zhu L, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish JP, Fleiszig SM, et al. ExoU expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa correlates with acute cytotoxicity and epithelial injury. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:547–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4891851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink SL, Cookson BT. Apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necrosis: mechanistic description of dead and dying eukaryotic cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1907–1916. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.1907-1916.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DW, Nair G, Schweitzer HP. Construction and characterization of chromosomal insertional mutations of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S trans-regulatory locus. Infect Immun. 1994;62:554–563. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.554-563.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity-Ryan L, Kazmierczak B, Kowal R, Comolli J, Hauser A, Engel JN. The arginine finger domain of ExoT contributes to actin cytoskeleton disruption and inhibition of internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by epithelial cells and macrophages. Infect Immun. 2000;68:7100–7113. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.7100-7113.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehring UM, Schmidt G, Pederson KJ, Aktories K, Barbieri JT. The N-terminal domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S is a GTPase-activating protein for Rho GTPases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36369–36372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Shashi S, Mohan M, Lamba IM, Gupta R. Epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Trop Pediatr. 1993;39:32–36. doi: 10.1093/tropej/39.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C, Flores MV, Storm T, Crosier K, Crosier P. The zebrafish lysozyme C promoter drives myeloid-specific expression in transgenic fish. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser AR, Cobb E, Bodi M, Mariscal D, Valles J, Engel JN, Rello J. Type III protein secretion is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:521–528. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbomel P, Thisse B, Thisse C. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1999;126:3735–3745. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa JK, English SB, Wolfgang MC, Jackson R, Butte AJ, Lory S. Genome-wide analysis of host responses to the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system yields synergistic effects. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1635–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles MR, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:571–577. doi: 10.1172/JCI15217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski MA, Osborn E, Kazmierczak BI. A novel sensor kinase-response regulator hybrid regulates type III secretion and is required for virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:1090–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guyader D, Redd MJ, Colucci-Guyon E, Murayama E, Kissa K, Briolat V, et al. Origins and unconventional behavior of neutrophils in developing zebrafish. Blood. 2008;111:132–141. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VT, Smith RS, Tummler B, Lory S. Activities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa effectors secreted by the Type III secretion system in vitro and during infection. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1695–1705. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1695-1705.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Chen S, Cao Z, Lin Y, Mo D, Zhang H, et al. Acute phase response in zebrafish upon Aeromonas salmonicida and Staphylococcus aureus infection: striking similarities and obvious differences with mammals. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter EI, Faria MM, Rabin HR, Storey DG. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates from individual patients demonstrate a range of levels of lethality in two Drosophila melanogaster infection models. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1877–1888. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01165-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. Establishment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: lessons from a versatile opportunist. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan-Miklos S, Tan MW, Rahme LG, Ausubel FM. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence elucidated using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Caenorhabditis elegans pathogenesis model. Cell. 1999;96:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80958-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias JR, Perrin BJ, Liu TX, Kanki J, Look AT, Huttenlocher A. Resolution of inflammation by retrograde chemotaxis of neutrophils in transgenic zebrafish. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1281–1288. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui H, Verghese MW, Kesimer M, Schwab UE, Randell SH, Sheehan JK, et al. Reduced three-dimensional motility in dehydrated airway mucus prevents neutrophil capture and killing bacteria on airway epithelial surfaces. J Immunol. 2005;175:1090–1099. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan SA, Huang X, Barrett RP, van Rooijen N, Hazlett LD. Macrophages restrict Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth, regulate polymorphonuclear neutrophil influx, and balance pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:5219–5227. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata S, Casey M, Frank DW, Ausubel FM, Drenkard E. Use of the Galleria mellonella caterpillar as a model host to study the role of the type III secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2404–2413. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2404-2413.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama E, Kissa K, Zapata A, Mordelet E, Briolat V, Lin HF, et al. Tracing hematopoietic precursor migration to successive hematopoietic organs during zebrafish development. Immunity. 2006;25:963–975. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely MN, Pfeifer JD, Caparon M. Streptococcus-zebrafish model of bacterial pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3904–3914. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3904-3914.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nivens DE, Ohman DE, Williams J, Franklin MJ. Role of alginate and its O acetylation in formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa microcolonies and biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1047–1057. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.1047-1057.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson KJ, Krall R, Riese MJ, Barbieri JT. Intracellular localization modulates targeting of ExoS, a type III cytotoxin, to eukaryotic signalling proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:1381–1390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RT, Link BA, Dowling JE, Schreiber SL. Small molecule developmental screens reveal the logic and timing of vertebrate development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12965–12969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prajsnar TK, Cunliffe VT, Foster SJ, Renshaw SA. A novel vertebrate model of Staphylococcus aureus infection reveals phagocyte-dependent resistance of zebrafish to non-host specialized pathogens. Cell Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressley ME, Phelan PE, 3rd, Witten PE, Mellon MT, Kim CH. Pathogenesis and inflammatory response to Edwardsiella tarda infection in the zebrafish. Dev Comp Immunol. 2005;29:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahme LG, Ausubel FM, Cao H, Drenkard E, Goumnerov BC, Lau GW, et al. Plants and animals share functionally common bacterial virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8815–8821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls JF, Mahowald MA, Ley RE, Gordon JI. Reciprocal gut microbiota transplants from zebrafish and mice to germ-free recipients reveal host habitat selection. Cell. 2006;127:423–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J, Hagen A, Hsu K, Deng M, Liu TX, Look AT, Kanki JP. Interplay of pu.1 and gata1 determines myelo-erythroid progenitor cell fate in zebrafish. Dev Cell. 2005;8:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Burman A, Savel RH, Racine S, Swanson BL, Revadigar NS, Fujimoto J, et al. Type III protein secretion is associated with death in lower respiratory and systemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1767–1774. doi: 10.1086/320737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver CM, Hauser AR. Interactions between effector proteins of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system do not significantly affect several measures of disease severity in mammals. Microbiology. 2006;152:143–152. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu X, Shaner NC, Yarbrough CA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ. Novel chromophores and buried charges control color in mFruits. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9639–9647. doi: 10.1021/bi060773l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens EJ, Ryan CM, Friedberg JS, Barnhill RL, Yarmush ML, Tompkins RG. A quantitative model of invasive Pseudomonas infection in burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1994;15:232–235. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stossel TP, Babior BM. Structure, function, and functional disorders of the phagocyte system. In: Handin RI, Lux SE, Stossel TP, editors. Blood: Principle and Practice of Hematology. Lippincott; Philadelphia, PA: 2003. pp. 531–568. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Barbieri JT. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT ADP-ribosylates CT10 regulator of kinase (Crk) proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32794–32800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Kays M, Prince A. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili in acute pulmonary infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1278–1285. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1278-1285.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanji T, Ip YT. Regulators of the Toll and Imd pathways in the Drosophila innate immune response. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver D, Herbomel P, Patton EE, Murphey RD, Yoder JA, Litman GW, et al. The zebrafish as a model organism to study development of the immune system. Adv Immunol. 2003;81:253–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sar AM, Musters RJ, van Eeden FJ, Appelmelk BJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Bitter W. Zebrafish embryos as a model host for the real time analysis of Salmonella typhimurium infections. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:601–611. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sar AM, Stockhammer OW, van der Laan C, Spaink HP, Bitter W, Meijer AH. MyD88 innate immune function in a zebrafish embryo infection model. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2436–2441. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2436-2441.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance RE, Rietsch A, Mekalanos JJ. Role of the type III secreted exoenzymes S, T, and Y in systemic spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 in vivo. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1706–1713. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1706-1713.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman HE, Clay H, Beery D, Chang JC, Sherman DR, Ramakrishnan L. Tuberculous granuloma formation is enhanced by a mycobacterium virulence determinant. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahr TL, Vallis AJ, Hancock MK, Barbieri JT, Frank DW. ExoY, an adenylate cyclase secreted by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13899–13904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolfaghar I, Evans DJ, Ronaghi R, Fleiszig SM. Type III secretion-dependent modulation of innate immunity as one of multiple factors regulated by Pseudomonas aeruginosa RetS. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3880–3889. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01891-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Infected macrophage within the clogged caudal artery, corresponding to Fig. 3C. A PA-infected macrophage (center) moves within the caudal artery towards an infected cellular aggregate (left) that is clogging the vessel. Scale bar, 20μm.

Cellular aggregate within the yolk circulation valley, corresponding to Fig. 3D. An aggregation of erythroid cells and occasional macrophages remains in place while blood flow continues adjacent to it. Scale bar, 20μm.

Uptake of PA by Tg(mpx:GFP)-positive neutrophils shortly after infection, corresponding to Fig. 4C. In this three-dimensional perspective, mpx expression is shown in green. Extracellular bacteria are rendered in white, bacteria inside GFP-bright cells (neutrophils) are pink, and bacteria inside GFP-dim cells (macrophages) are red. Scale grid, 10μm.