Abstract

GRIM-19 (Gene associated with Retinoid-IFN-induced Mortality-19) was originally isolated as a growth suppressor in a genome-wide knockdown screen with antisense libraries. Like classical tumor suppressors, mutations, and/or loss of GRIM-19 expression occur in primary human tumors; and it is inactivated by viral gene products. Our search for potential GRIM-19-binding proteins, using mass spectrometry, that permit its antitumor actions led to the inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4, CDKN2A. The GRIM-19/CDKN2A synergistically suppressed cell cycle progression via inhibiting E2F1-driven gene expression. The N terminus of GRIM-19 and the fourth ankyrin repeat of CDKN2A are crucial for their interaction. The biological relevance of these interactions is underscored by observations that GRIM-19 promotes the inhibitory effect of CDKN2A on CDK4; and mutations from primary tumors disrupt its ability to interact with GRIM-19 and suppress E2F1-driven gene expression.

Keywords: Cell Cycle, Cytokine Action, E2F Transcription Factor, Interferon, Tumor Suppressor, Protein Interaction, Cancer, Growth Suppression, Inhibitors

Introduction

Gene associated with Retinoid-IFN-induced Mortality-19 (GRIM-19)3 was originally identified as a critical pro-apoptotic gene product in IFN-β/RA-induced cell death pathway (1). Ever since its identification, a number of reports have established its tumor suppressor-like characters (2–5). Like many typical tumor suppressors, GRIM-19 is also inactivated by oncogenic proteins (2, 6, 7). For example, the pro-apoptotic function of GRIM-19 is inhibited by different viruses (4, 8, 9), GRIM-19 suppresses STAT3-dependent transcription and oncogenic transformation (5, 10). Mutations in GRIM19 in some thyroid carcinomas (11) and a loss of its expression were reported in renal cell (2) and cervical (12) carcinomas. To further define the mechanisms of the anti-tumor actions of GRIM-19, we performed a proteomic analysis for GRIM-19-interacting proteins and identified CDKN2A (p16, INK4a), a member of the Inhibitor of CDK4 (INK4) family.

The INK4 family includes 4 proteins viz., p15, p16, p18 and p19 (13), which interact with cyclin D-CDK4/6 complex to suppress the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma (RB) protein (14). RB binds to transcription factor E2F1 and suppresses G1/S-associated gene expression (15). Phosphorylation of RB by CDK4 releases E2F1 from the RB/E2F1 complex, which initiates transcription of proliferation-associated genes, e.g. CCNB, DHFR, JUNB, and TK1 (16, 17). Here we show that the association of GRIM-19 with CDKN2A (p16), synergistically inhibited cell cycle progression by suppressing E2F-dependent gene expression. We also identified the critical domains of both proteins implicated in this interaction. More importantly, we show that some clinically observed mutations in both proteins disrupt these interactions. This study, for the first time, not only demonstrates the growth-suppressive function of GRIM-19 but also its connections to other tumor-suppressor networks involved in cell cycle control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene Expression Analyses

Wild-type and mutant GRIM19 (39) (supplemental Table S1A) were expressed as Myc-tagged proteins using pIRES-Puro2 vector (Clontech). The cDNAs for murine Cdkn2a (p16), Cdkn2c (p18), Cdkn2d (p19) (provided by Drs. M. Roussel and C. Sherr), and human CDKN2A (Open Biosystems) were expressed as N-terminally FLAG-tagged proteins using pIRES-Puro2 vector (supplemental Table S1B). Cyclin D1 cloned in pRc/CMV-Neo expression vector was a gift from Dr. Richard Pestell, Thomas Jefferson University. CDKN2A mutants were generated using specific primers (supplemental Table S1C) and expressed using pLVX-Puro vector (Clontech). Lentiviral shRNA vectors for GRIM19 and STAT3 have been described (25). Antibodies specific for RB, phospho-Ser795 RB, Myc tag, and CDK4 (Cell Signaling), p16 mAb, and polyclonal antibodies against CDK4 (Chemicon), p16, and cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology.), FLAG tag (Sigma-Aldrich), FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (KPL, Inc), Texas red-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Labs), and control rabbit (NR) IgG (Sigma), RA (Sigma), and hIFN-β (Biogen, Inc) were used in these studies. Real-time PCR with gene-specific primers (supplemental Table S2) was performed as in our earlier publications (2). A double-thymidine block and release was used to synchronize cells at G1/S boundary (42). Cell cycle distribution was determined using FACS. For cells, lysates were prepared at 0, 1, 2, and 4 h after release and Western blot, and IP analyses were performed as per our earlier publications (26, 40). All data were subjected to statistical analyses using Student's t test.

Proteomic Analysis

HeLa cells stimulated with IFN-β (1500 units/ml) and RA (1.5 μm), for 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 48 h (12 samples/time point × 3 batches) and pooled lysates were immunoprecipitated with a GRIM-19-specific antibody (43) coupled to Sepharose-4B. The bound proteins were eluted, pooled, and subjected to tryptic digestion (44). The resultant mixture of peptides was subjected to MALDI-TOF analysis at the University of Maryland Proteomics Core Lab. Mass fingerprint profiles generated from GRIM-19-associated peptides of IFN/RA-stimulated cells were compared with unstimulated cells. In parallel, a control isotypic IgG-based IP reaction was used as a negative control. The peptide fingerprints present, in complex with GRIM-19, in IFN/RA-stimulated cells were chosen for querying the MASCOT fingerprint database to predict the matches.

Establishment of Stable Cell Lines

Stable GRIM-19-expressing cells (25) were generated after selecting with G418 (500 μg/ml). Other stable cell lines were established after infecting with lentiviruses coding for gene of interest and selecting with puromycin (2 μg/ml) for 2 days. Endogenous GRIM-19 and STAT3 were knocked down using lentiviral vectors (25) coding for specific shRNAs and selected with puromycin. The protocol for generating lentiviral particles have been described in our earlier publications (25, 39). To avoid a clonal bias, we employed pools of cell clones (n ∼75) in each case.

RESULTS

Identification of p16 as a GRIM-19-binding Protein

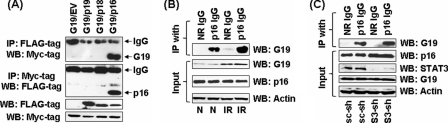

To identify its potential interacting partners, GRIM-19 was immunoprecipitated from IFN/RA-treated HeLa cell lysates with a GRIM-19 mAb. IP products from different time points were pooled, digested with trypsin, and the resultant peptide mixture was subjected to MALDI-TOF analysis. Mass fingerprint data were used for querying the MASCOT data base to predict the matches. Mass values of four peptides from this mixture matched to peptides from INK4 proteins (supplemental Fig. S1). To verify these initial observations and if other INK4 proteins were also capable of interacting with GRIM-19. The p16, p18, and p19 proteins were expressed individually in HeLa cells along with Myc-tagged GRIM-19 or an empty vector. Twenty-four hours later, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a Myc tag-specific monoclonal antibody. The IP products were subjected to a Western blot analysis with FLAG tag-specific antibody. Only p16, but not p18 and p19, bound to GRIM-19 (Fig. 1A). This interaction was further confirmed by performing a converse IP with FLAG tag-specific antibody followed by Western blot analysis with Myc tag-specific antibody. To study the interactions between endogenous proteins and the effects of IFN/RA on them, lysates from naïve and IFN/RA-treated HeLa cells were subjected to IP with p16-specific polyclonal antibody followed by a Western blot analysis with a GRIM-19-specific monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1B). IP reactions with the p16-specific IgG, but not the control IgG, contained endogenous GRIM-19. IFN/RA further enhanced these interactions. Such IFN/RA-induced interaction could be due to an increase in endogenous GRIM-19 levels, although one cannot rule out a role for post-translational modifications of one or both of the proteins. Because STAT3 is also a GRIM-19-binding protein, we next determined if the former was required for GRIM-19-p16 interactions to occur. Therefore, we first knocked down endogenous STAT3 in HeLa cells using STAT3-specific shRNAs. A non-silencing shRNA (scrambled) was used as a control. IP analysis showed that depletion of STAT3 did not appreciably affect p16-GRIM-19 interactions (Fig. 1C). Immunofluorescence studies colocalized both proteins in situ. GRIM-19 was distributed in the cytoplasm as punctuate structures, with some nuclear presence, and p16 was homogenously distributed in both nucleus and cytoplasm. Importantly, both proteins co-localized in the cell (supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 1.

GRIM-19 interacts with p16. A, HeLa cells were transfected with expression constructs for GRIM-19 (G19, Myc-tagged) and p16, p18, and p19 (FLAG-tagged) or an empty vector (EV). The cell lysates were subjected to IP with the indicated antibody. The upper panels show the IP results, and the lower panels show expression levels of the indicated proteins. Only p16 interacted with GRIM-19. B, endogenous GRIM-19 and p16 interact in HeLa cells. Lysates (500 μg/sample) prepared from cells at steady state (N) and IFN-β/RA-treated (IR) were subjected to IP followed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. Actin was used as loading control. C, GRIM-19-p16 interaction is STAT3 independent. Cell lysates from STAT3-depleted (S3-sh) and control (sc-sh) HeLa cells were subjected to IP and Western blot with the indicated antibodies. Actin was used a as loading control. No observable difference in GRIM-19-p16 interaction from either cell line is suggestive of a STAT3-independent interaction.

Identification of Critical Regions Required for an Interaction between GRIM-19 and p16

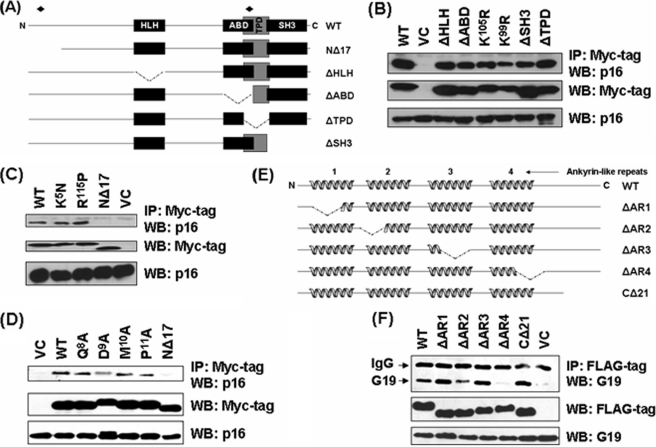

Next, we determined the domains in GRIM-19 and p16 required for their interactions. Different deletion and point mutants of GRIM-19 were generated based on a structure prediction using the BLOCKS program and published sources on p16 structure (18). Two point mutations (K5N and R115P) (Fig. 2A) were recently identified in Hürthle cell thyroid carcinomas (11). The motifs (ABD: HLH: Helix-loop-Helix; ATP-binding domain; TPD: tyrosine phosphorylation like domain and SH3: SH3-like domain) of GRIM-19 are distributed along the length of GRIM-19 protein (Fig. 2A). These deletions and several point mutations along with GRIM-19 NΔ17, which lacked the first 17 amino acids at N terminus, was also used for defining the critical motifs of GRIM-19 required these interactions. IP analyses showed that only GRIM-19 NΔ17, but not the other deletions, failed to interact with p16 (Fig. 2, B–D). To further define the critical residues within the N terminus of GRIM-19, we generated four additional point mutants (Q8A, D9A, M10A, and P11A) (see Fig. 2A) and tested their ability to interact with p16. The D9A mutant significantly lost its ability to bind p16 (Fig. 2D). This difference in the interaction was not due to differential expression of the mutants. The p16 protein contains four ankyrin repeats, which are likely to mediate protein-protein interactions (Fig. 2E). Three of them form pairs of helix-loop-helix structures with the remaining one forming only single helix. Mutants with deletions in each of the ankyrin repeats and the C-terminal 21 amino acids of p16 were created (Fig. 2E); and tested for their ability to associate with GRIM-19. These experiments revealed that the fourth ankyrin repeat of p16 is critical for its binding to GRIM-19 (Fig. 2F). All mutants exhibited very similar cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution as wild-type proteins (supplemental Fig. S3). Importantly, p16 ΔAR4 and GRIM-19 NΔ17, which showed loss of interaction, were localized in cytoplasm and nucleus homogenously like their corresponding wild-type counterparts (supplemental Fig. S4).

FIGURE 2.

Identification of critical regions in GRIM-19 and p16 necessary for their association. A, modular representation of BLOCKS-predicted GRIM-19 structure. NΔ17, deletion of amino acids 1–17; HLH, helix-loop-helix; ABD; ATP-binding domain; TPD, tyrosine phosphorylation- like domain; SH3, Src homology 3; ♦, location of point mutations. B–D, interaction of GRIM-19 with endogenous p16 in HeLa cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated expression constructs. Lysates were analyzed for expression of the respective proteins followed by IP and WB analysis with the indicated antibodies. E, modular representation of p16 structure redrawn form published sources. Deletion of ankyrin-like repeats (ΔAR1–4) and C-terminal region (ΔC21) are indicated. F, interaction of p16 deletions with endogenous GRIM-19 in HeLa cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated expression constructs. Lysates were analyzed for expression of the respective proteins followed by IP and WB analysis with the indicated antibodies.

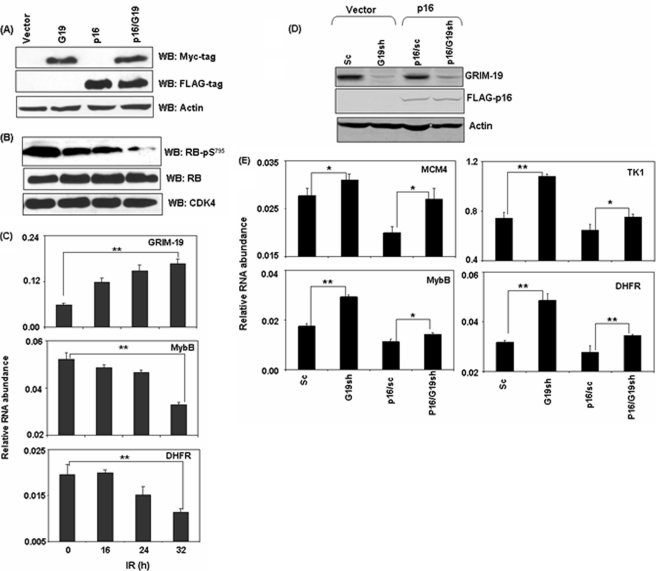

GRIM-19 and p16 Synergistically Cause G1 Arrest

Transcription factor E2F1 plays major roles during cell cycle; via a transcriptional induction of genes involved in cell cycle progression (19). To investigate the impact of p16, GRIM-19 and their combinations on E2F-dependent gene expression, we established stable MCF-7 cell lines expressing p16, GRIM-19 and p16/GRIM-19 and compared it to empty vector-transfected cells. First, we ensured an equivalent expression of exogenous p16 and GRIM-19 in these stable cells, using Western blots (Fig. 3A) and real-time PCR analysis with primers that can detect transgene-derived transcripts (supplemental Fig. S5). As shown in Table 1, p16 suppressed the expression of E2F1-regulated S-phase-specific genes: TK1, DHFR, and MYBB. Surprisingly, GRIM-19 also suppressed the expression of E2F1-responsive genes (Table 1). More importantly, co-expression of p16/GRIM-19 synergistically inhibited the expression of E2F1-responsive genes (Table 1).

FIGURE 3.

Co-expression of GRIM-19 and p16 generates a synergistic inhibitory effect on E2F1-responsive genes. A, expression levels of GRIM-19 and p16 in MCF-7 cells. Actin was used as a loading control. B, phosphorylated Ser795 RB levels in MCF-7 cells. Typical WB profile of total cellular lysates from the indicated cell lines probed with the indicated antibodies. Expression of either GRIM-19 or p16 decrease phospho-Ser795 RB levels while co-expression decreases it even further with similar CDK4 levels. C, relative mRNA abundance in naïve MCF-7 cells stimulated with IFN/RA, for the indicated time points, measured by real-time PCR. IFN/RA treatment up-regulates GRIM19 and down-regulates E2F1-responsive transcript levels. D and E, GRIM-19 is required for an effective inhibitory role of p16 on E2F1-responsive genes. D, WB profile of the indicated MCF-7 cell line pairs infected with indicated lentiviral shRNAs. GRIM-19 is knocked down only by a specific shRNA (G19sh). Actin was used as loading control. E, relative mRNA abundance in the indicated MCF-7 cells lines pairs measured by real-time PCR. Knockdown of GRIM-19 increases E2F1-responsive transcript levels either in the absence or presence of p16.

TABLE 1.

Quantitative representation of E2F1-responsive transcript levels in MCF-7 cells expressing either GRIM-19 and/or p16

Student's t-test was used to access the statistical differences. GRIM-19 and/or p16/GRIM-19-expressing cells were compared to p16-expressing cells.

| Gene analyzed | Cell line pairs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV | p16 | GRIM-19 | p16/GRIM-19 | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| MCM4 | 100 | 96.3 ± 5.0 | 58.3 ± 0.9 | 24.9 ± 0.6 |

| (p < 0.01) | (p < 0.01) | |||

| MYBB | 100 | 88.0 ± 11.4 | 74.1 ± 2.7 | 35.3 ± 4.4 |

| (p < 0.05) | (p < 0.01) | |||

| DHFR | 100 | 67.0 ± 3.9 | 65.9 ± 8.0 | 13.8 ± 6.4 |

| (p < 0.01) | ||||

| TK1 | 100 | 71.4 ± 8.0 | 50.7 ± 3.4 | 21.6 ± 2.6 |

| (p < 0.01) | (p < 0.01) | |||

Because E2F1 activity is dependent on cyclin D/CDK4-dependent inactivation of RB via serine phosphorylation (17), we next assessed the phosphorylation on RB at serine 795 in these stable cells using Western blot analysis with a specific antibody. Both GRIM-19 and p16 decreased serine 795 phosphorylation on RB. However, co-expression of these two proteins led to a stronger suppression of RB phosphorylation compared with p16 or GRIM-19 alone (Fig. 3B). The difference in serine phosphorylation was not due to different levels of total RB in these lanes (Fig. 3B). To ensure that differential Ser795 phosphorylation of RB was not due to different CDK4 levels in these cell lines, we performed a WB analysis. The levels of CDK4 were also comparable across the cell lines (Fig. 3B). To study the relevance of this interaction on cell cycle progression, we used double-thymidine block to synchronize cells at G1 stage and examined the timing of their transition to S phase, after releasing the blockade, using FACS. Majority of cells (60–65%) synchronized at G1 after double-thymidine block (supplemental Fig. S6). Four hours after release, 26% of control cells exited G1 and entered S phase, while 22 and 17% of cells exited G1 in p16 and GRIM-19-expressing cell lines, respectively. In contrast, only 8% of GRIM-19/p16-expressing cells exited G1 (supplemental Fig. S6).

Because GRIM-19 is a critical component in IFN/RA-induced growth-suppressive pathway (1, 20), we next investigated the physiological relevance of these interactions by examining the effect of IFN/RA on E2F1-responsive gene expression. As mentioned earlier, IFN/RA stimulation steadily increased the expression of GRIM-19 (p < 0.01), with a corresponding suppression of E2F1-responsive genes (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3C).

Depletion of GRIM-19 Enhances E2F1-driven Gene Expression

To further demonstrate the regulation of E2F1-responsive genes by GRIM-19 and p16, we knocked down endogenous GRIM-19 in MCF-7/p16 and MCF-7/vector cell line pairs using a GRIM19-specific shRNA delivered via lentiviral particles. A scrambled shRNA was used as a control in these experiments. GRIM-19-specific shRNA specifically decreased steady-state GRIM-19 levels while p16 was unaffected (Fig. 3D). Knockdown of GRIM-19 correlated with a significant increase in the expression of E2F1-responsive genes (Fig. 3E), even in the presence of exogenous p16.

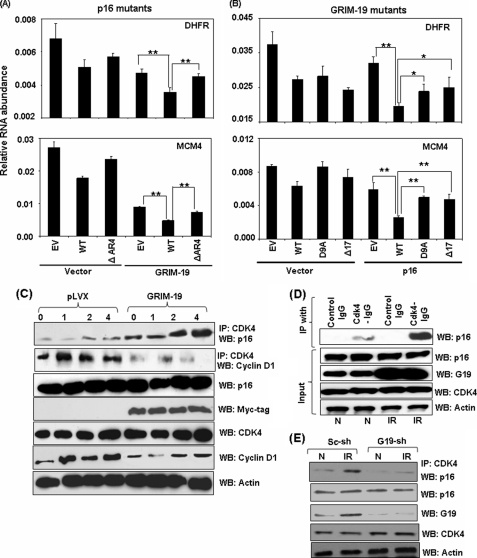

Mutant p16 and GRIM-19 Proteins Fail to Synergize and Exert Their Negative Effects on Gene Expression

As described earlier, p16 ΔAR4 mutant did not bind to GRIM-19 and GRIM-19 mutants (D9A and NΔ17) failed to bind with wild-type p16 (see Fig. 2). To determine if they retained their synergistic inhibitory effects on E2F1-dependent gene expression, we infected GRIM-19-expressing cells with lentiviral particles coding for p16 ΔAR4. Similarly, p16-expressing cells were infected with lentiviral particles coding for GRIM-19 D9A and NΔ17. Total RNA from these cell lines was used for determining the levels of E2F1-regulated genes. Although all mutants inhibited E2F1-responsive gene expression, compared with vector control (Fig. 4B), p16 ΔAR4 failed to further suppress E2F1-responsive genes synergistically (p < 0.01) in association with GRIM-19 (Fig. 4A). Similarly, both GRIM-19 mutants did not support a synergistic inhibition of E2F1-responsive gene expression in association with p16, like wild-type GRIM-19 (Fig. 4B). These data suggested that the association of GRIM-19 with p16 to be critical for the synergistic inhibitory effect of E2F1-responsive genes. The biological importance of these observations was correlated with an inability of these mutants to collaborate with the wild-type proteins in suppressing tumor growth in vivo (Table 2). For example, the ΔAR4 mutant in association with GRIM-19 was unable to suppress tumor growth like wild-type p16. Similarly, the GRIM-19 NΔ17 mutant also failed to suppress growth along with wild-type p16.

FIGURE 4.

A and B, interaction-defective p16 and GRIM-19 proteins fail to synergize that is required to inhibit E2F1-driven transcription. Relative mRNA abundance in the indicated MCF-7 cells lines pairs measured by real-time PCR. The p16 mutant (ΔAR4) and GRIM-19 mutants (D9A and Δ17) differentially suppress E2F1-responsive transcript levels compared with their wild-type counterparts. Student's t test was used to obtain significance (*, p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01). C–E, GRIM-19 augments CDK4-p16 interactions. C, WB profile of HeLa cell lines, synchronized, and released (see “Materials and Methods”), probed with the indicated antibodies. In the presence of GRIM-19, more p16 and less cyclin D1 associate with CDK4. D, IFN/RA stimulation up-regulates GRIM-19 that augments CDK4-p16 interactions. E, CDK4 and p16 interact weakly when GRIM-19 is lowered.

TABLE 2.

Effect of GRIM-19/16 combinations on tumor growth

Athymic nude mice were subcutaneously transplanted with MCF-7 cells (which lack endogenous p16) expressing the indicated gene products as in our earlier studies (45). Tumor growth was measured, and mean tumor volumes (n = 8 mice/group) at the end of the 11th week, the terminal point in this experiment, are shown. p values were determined using the Student's t-test.

| Tumor | Mean tumor volume | p value |

|---|---|---|

| mm3 ± S.D. | ||

| EV | 386 ± 45 | NDa |

| p16 | 287 ± 31 | <0.005 vs vector |

| GRIM-19 | 264 ± 28 | <0.003 vs vector |

| p16/GRIM-19 | 86 ± 19 | <0.0001 vs vector |

| GRIM-19 NΔ17 | 347 ± 67 | NSb |

| GRIM-19 NΔ17/p16 | 276 ± 26 | <0.003 vs vector |

| p16 ΔAR4 | 342 ± 38 | NS |

| p16 ΔAR4/GRIM-19 | 246 ± 23 | <0.001 vs vector |

a ND, not determined.

b NS, not significant.

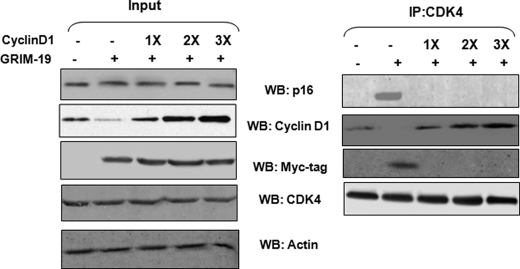

Binding of p16 to CDK4 Is Enhanced in the Presence of GRIM-19

As said earlier, p16 inhibits E2F1-responsive gene expression by preventing the association of cyclin D with CDK4 (14). As shown before (Figs. 1 and 2), neither GRIM-19 nor p16 affected the expression of other. To define the mechanism of synergistic inhibitory effect on E2F1 by GRIM-19 and p16, we examined whether GRIM-19 plays any role in promoting the association of p16 with CDK4. HeLa cells were synchronized at G1 with a double thymidine block and lysates were prepared at different time points after release. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with a CDK4-specific antibody followed by a Western blot analysis of the IP products with the indicated antibodies. In the presence of GRIM-19, more p16 associated with CDK4 compared with corresponding empty vector control (Fig. 4C). Consistent with these observations, less cyclin D1 associated with CDK4. We next examined if similar sustenance of p16-CDK4 interactions occurred upon IFN/RA treatment. HeLa cells were stimulated with IFN/RA and the lysates were immunoprecipitated with a control or CDK4-specific IgG. The products were subjected to a Western blot analysis with a p16-specific antibody. Indeed, more p16 associated with CDK4 upon IFN/RA treatment (Fig. 4D). IFN/RA did not affect CDK4 and/or p16 levels but increased GRIM-19 levels as observed in our other studies (Fig. 4D). Consistent with these observations, the association of p16 with CDK4 diminished significantly upon depleting endogenous GRIM-19 with a specific shRNA (Fig. 4E).

Overexpression of Cyclin D1 Disrupts CDK4 Interactions with p16/GRIM-19

Because GRIM-19 could suppress the levels of endogenous cyclin D1, we next tested whether overexpression of cyclin D1 could disrupt the complex formed between CDK4, p16 and GRIM-19. Therefore, we co-transfected increasing amounts of a cyclin D1 expression vector with a fixed amount of GRIM-19-vector. After ensuring the expression of p16, GRIM-19, cyclin D1, CDK4 (Fig. 5left half), the lysates were subjected to IP analysis (Fig. 5, right half). As expected cyclin D levels were lowered when GRIM-19 was expressed in the cells. Cyclin D1 levels rose progressively, consistent with the input plasmid amount (left half). Upon overexpression, we were able to see a complex that contained CDK4, p16, and GRIM-19 (right half). In the presence of overexpressed cyclinD1, there was a complete loss of this complex, with the prevalence of cyclin D1/CDK4 complexes. Thus, exogenous cyclin D1 can overcome the inhibitory complex formed by GRIM-19/p16 with CDK4.

FIGURE 5.

Overexpression cyclin D1 inhibits p16/GRIM-19 interactions with CDK4. HeLa cells were transfected with expression coding for GRIM-19-myc along with increasing amounts cyclin D1. CDK4 was immunoprecipitated from 500 μg of total protein, and the products were subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. IP reactions were conducted in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer with 50 mm NaCl. The left and right halves of the figure show Western blots of input (1/5th of the amount used for IP) and immunoprecipitated samples, respectively.

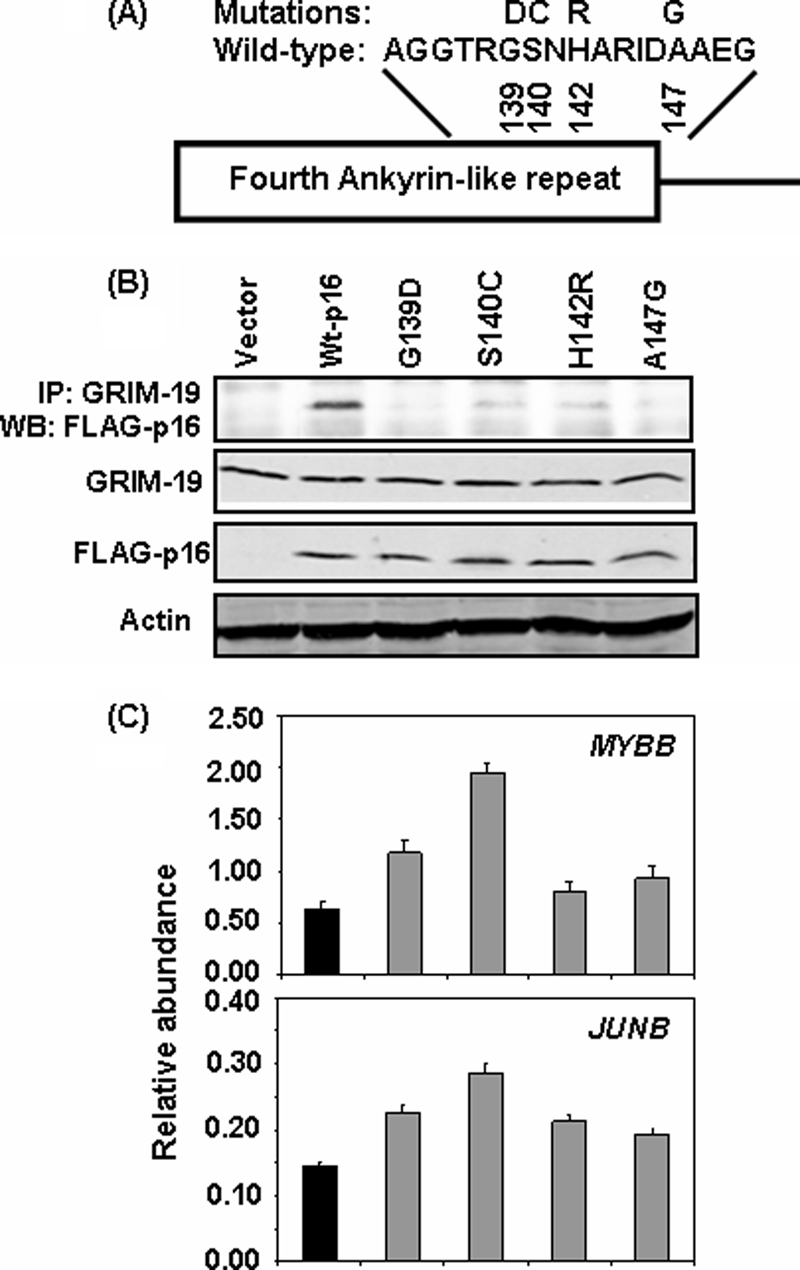

Tumor-derived Mutations in the 4th Ankyrin-like Repeat of Human p16 Affect Interactions with GRIM-19 and E2F1-driven Responses

Because loss of p16 activity has been reported in many tumors (13), we wanted to know whether such mutations affect p16 function in the context of GRIM-19. Because the 4th ankyrin repeat of p16 is essential for this interaction to occur, we specifically generated point mutations in AR4 of human p16 (Fig. 6A), based on the reported clinical data (21, 22). MCF-7 cells were infected with lentiviral particles coding for various p16 mutants and selected with puromycin for 2 days to remove uninfected cells. An equivalent expression of FLAG-tagged mutant p16 proteins, and endogenous GRIM-19 was ascertained by performing a Western blot analysis (Fig. 6B) in these cell lines. Lysates from these cells were immunoprecipitated with a GRIM-19-specific antibody and the products were subjected to Western blot analysis with FLAG tag-specific antibody. All mutants, unlike wild-type p16, failed to interact with GRIM-19 (Fig. 6B). We then measured the levels of E2F1-responsive transcripts using real-time PCR. Significantly, higher levels of these RNAs (p < 0.05) were noted in the presence of p16 mutant proteins compared with wild-type p16 (Fig. 6C). There was a differential inhibitory effect among the mutants, the basis for which is unclear at this stage.

FIGURE 6.

Tumor-associated point mutations in the 4th ankyrin-like repeat disrupt GRIM-19 interaction. A, amino acid sequence in the 4th ankyrin-like repeat of wild-type human p16. Mutants analyzed are indicated by single-letter code and their residue number is indicated below. B, expression levels and IP analysis of mutant p16 with endogenous GRIM-19 in MCF-7 cells. Mutants G139D and A147G show a near loss-of-interaction while mutants S140C and H142R show appreciable loss-of-interaction compared with wild-type p16. C, relative mRNA abundance in the indicated MCF-7 cells lines measured by real-time PCR. Mutant p16 proteins have significantly (p < 0.05) lost their ability to suppress E2F1-responsive transcript levels, compared with wild-type p16.

DISCUSSION

Tumor suppressors regulate multiple pathways to restrain malignant growth. For example, p53 can elicit different cellular responses, such as cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, DNA repair, and inhibition of angiogenesis (23, 24). Previous studies from our group identified a novel growth-suppressive gene product GRIM-19 (1). We and others, (3, 5) using yeast 2-hybrid screens, identified STAT3 as one of its intracellular target. GRIM-19 physically interacts with the transactivation domain of STAT3 and repressed the expression of STAT3-regulated genes, many of which have been implicated in growth promotion. Indeed, GRIM-19 suppressed the oncogenic transformation caused by v-Src (a known activator of STAT3) (25) and a constitutively active STAT3 (10). GRIM-19 also interacts with a mitochondrial serine protease HtrA2/Omi to promote the degradation of the caspase-inhibitor, XIAP (26). We have shown that the vIRF1 oncoprotein of KSHV inhibits these interactions to promote cell survival (4). Apart from these, GRIM-19 was shown to be a constituent of mitochondrial complex-I of the electron transport chain (27, 28). Human cytomegalovirus was shown to produce a non-coding RNA that binds to complex-I to prevent the release of GRIM-19 form the complex and activation of apoptosis (9). GRIM-19 has been shown to associate with the NOD2 component of the intracellular inflammatory mediator and promote NF-kB activation in response to certain bacterial infections (29). Moderate expression of GRIM-19, although tolerated by several tumor cells lines, significantly inhibited cell growth. Based on these observations and the widespread intracellular distribution of GRIM-19, we hypothesized that there will be several yet undefined cellular partners for it. In this report, we identified a novel interaction between GRIM-19 and p16 (another tumor suppressor), which causes synergistic inhibition of G1-S phase transition and the expression of E2F1-responsive genes (30).

Surprisingly, GRIM-19 alone inhibited G1-S progression in MCF-7 cells, and this effect of GRIM-19 seemed to occur independently of p16 because MCF-7 cells lack endogenous p16 due a homozygous deletion of the CDKN2A locus (31), thus, exposing an additional pathway that operates independently of p16. Previous reports have shown that IFNs suppress E2F activity and growth-promoting gene expression (32, 33). Some studies have shown that in Burkitt's lymphoma cells, IFN can induce expression level of RB (32), which can inhibit the transcriptional activity of E2F, although the upstream mechanisms were not clear. Similarly, one study reported a poorly defined inactivation of E2F1 by retinoic acid in some bronchial epithelial cells (34). Our observations that GRIM-19 can be induced by IFN-β alone (1), and is highly induced in association with RA suggest that such potentially negative effect(s) on E2F1 activation is controlled by GRIM-19 and/or in association with p16. Consistent with this suggestion, we observed an elevation of E2F-dependent gene expression following the knockdown of GRIM-19. Indeed, these results are consistent with our earlier studies that antisense-mediated knockdown of GRIM-19 confers a growth advantage in the presence of IFN/RA (1) and growth of tumor xenograft in vivo (2). Furthermore, direct administration of GRIM-19 expression plasmids into tumors growing in vivo also suppressed growth (35). Thus, inactivation of E2F1 activity may play a role in the growth-suppressive effects of GRIM-19. Apart from these mechanisms, another IFN-induced murine protein, p202 has also been shown to inhibit E2F1-dependent gene expression by preventing its DNA binding activity (36).

How does GRIM-19 behave as a novel E2F inhibitor? It is possible that GRIM-19 initiates an undefined pathway to suppress the expression level of E2F. Our unpublished studies showed depletion of GRIM-19 led to an elevation of RNA level of E2F1. Indeed, the E2F1 and its dimerizing partner DP1 genes are downstream targets of STAT3 (37), which is inhibited by GRIM-19. More importantly, GRIM-19 also suppressed STAT3-induced expression of cyclin D1 (10, 38). Cyclin D is a major activator of CDK4 and promoter of cell cycle progression (30). Together with our recent demonstration that GRIM-19 also suppress v-Src-induced cell motility and metastasis through cytoskeletal restructuring (39), independently of STAT3, the current report not only expands the spectrum of GRIM-19 actions but also firmly establishes its credentials as a new tumor suppressor. These data are further supported by a loss of its expression in primary tumors (2, 12, 35).

Tumor suppressor p16 is frequently either mutated or its expression is epigenetically suppressed in a number of tumors (13). Several studies have shown that mutations or deletions in the second and third ankyrin repeats of p16 abolish its anti-CDK4 activity (13). It was unclear, thus far, how genetic alterations, such as deletions, insertions or point mutations, in the fourth ankyrin repeat identified in various types of tumors inactivate p16 (13). We showed that deletion of the fourth ankyrin repeat (p16 ΔAR4) ablates the interaction of p16 with GRIM-19 and inactivated its ability to synergistically suppress E2F-responsive gene expression (Figs. 2 and 3) and tumor growth. Mechanistically, more p16 associated with CDK4 in the presence of GRIM-19, thus, blocking the phosphorylation of RB. The second and third ankyrin repeats of p16 are essential for the interaction with CDK4 while the fourth ankyrin is critical for association with GRIM-19. The physiologic importance of this region was revealed by the inability of clinically observed p16 mutants to interact with GRIM-19 (Fig. 6). One possible reason for such a loss of interaction is the poor ability of mutant p16 proteins to fold properly (40). It is possible the three proteins (CDK4, GRIM-19 and p16) form a complex that can prevent the association of CDK4 with activator cyclin D. We were not successful in showing the formation of this complex with endogenous proteins. However, upon overexpression of GRIM-19 and a high quantity of proteins for IP, we were able to observe GRIM-19 and p16 in complex with CDK4, which was displaced by an excess of cyclin D1 (Fig. 5). It is likely that such a complex becomes unstable during preparation of cellular extracts; or p16 dynamically switches between various complexes, given reports that INK4 proteins also participate in non-classical responses (41). However, we have shown that p16 was able to associate more stably with CDK4 in the presence of GRIM-19 (Fig. 4). Thus, these studies show a novel mechanism by which GRIM-19 blocks cell cycle progression; and potential collaboration between two disparate tumor suppressors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Roussel and C. Sherr for INK4 cDNAs and Richard Pestell for the cyclin D1 expression vector.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA105005 and CA78282 from the NCI (to D. V. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6 and Tables S1 and S2.

- GRIM

- gene associated with retinoid-IFN-induced mortality

- INK4

- inhibitor of CDK4

- IFN

- interferon

- RB

- retinoblastoma

- RA

- retinoic acid

- IP

- immunoprecipitate

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- WB

- Western blot

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angell J. E., Lindner D. J., Shapiro P. S., Hofmann E. R., Kalvakolanu D. V. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33416–33426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alchanati I., Nallar S. C., Sun P., Gao L., Hu J., Stein A., Yakirevich E., Konforty D., Alroy I., Zhao X., Reddy S. P., Resnick M. B., Kalvakolanu D. V. (2006) Oncogene 25, 7138–7147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lufei C., Ma J., Huang G., Zhang T., Novotny-Diermayr V., Ong C. T., Cao X. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 1325–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seo T., Lee D., Shim Y. S., Angell J. E., Chidambaram N. V., Kalvakolanu D. V., Choe J. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 8797–8807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J., Yang J., Roy S. K., Tininini S., Hu J., Bromberg J. F., Poli V., Stark G. R., Kalvakolanu D. V. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9342–9347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldas C., Hahn S. A., da Costa L. T., Redston M. S., Schutte M., Seymour A. B., Weinstein C. L., Hruban R. H., Yeo C. J., Kern S. E. (1994) Nat. Genet. 8, 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. (2000) Cell 100, 57–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerra S., López-Fernández L. A., Pascual-Montano A., Muñoz M., Harshman K., Esteban M. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 6493–6506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves M. B., Davies A. A., McSharry B. P., Wilkinson G. W., Sinclair J. H. (2007) Science 316, 1345–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalakonda S., Nallar S. C., Lindner D. J., Hu J., Reddy S. P., Kalvakolanu D. V. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 6212–6220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maximo V., Botelho T., Capela J., Soares P., Lima J., Taveira A., Amaro T., Barbosa A. P., Preto A., Harach H. R., Williams D., Sobrinho-Simões M. (2005) Br. J. Cancer 92, 1892–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y., Li M., Wei Y., Feng D., Peng C., Weng H., Ma Y., Bao L., Nallar S., Kalakonda S., Xiao W., Kalvakolanu D. V., Ling B. (2009) J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29, 695–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruas M., Peters G. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1378, F115–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherr C. J., Roberts J. M. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1149–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyson N. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2245–2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iaquinta P. J., Lees J. A. (2007) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 649–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nevins J. R. (1992) Science 258, 424–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan C., Selby T. L., Li J., Byeon I. J., Tsai M. D. (2000) Protein Sci. 9, 1120–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevaux O., Dyson N. J. (2002) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 684–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalvakolanu D. V. (2004) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 15, 169–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi N., Sugimoto Y., Tsuchiya E., Ogawa M., Nakamura Y. (1994) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 202, 1426–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyritsis A. P., Zhang B., Zhang W., Xiao M., Takeshima H., Bondy M. L., Cunningham J. E., Levin V. A., Bruner J. (1996) Oncogene 12, 63–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherr C. J. (2004) Cell 116, 235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherr C. J., McCormick F. (2002) Cancer Cell 2, 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalakonda S., Nallar S. C., Gong P., Lindner D. J., Goldblum S. E., Reddy S. P., Kalvakolanu D. V. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 171, 1352–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma X., Kalakonda S., Srinivasula S. M., Reddy S. P., Platanias L. C., Kalvakolanu D. V. (2007) Oncogene 26, 4842–4849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fearnley I. M., Carroll J., Shannon R. J., Runswick M. J., Walker J. E., Hirst J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38345–38348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang G., Lu H., Hao A., Ng D. C., Ponniah S., Guo K., Lufei C., Zeng Q., Cao X. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 8447–8456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnich N., Hisamatsu T., Aguirre J. E., Xavier R., Reinecker H. C., Podolsky D. K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19021–19026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherr C. J., Roberts J. M. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1501–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu L., Sgroi D., Sterner C. J., Beauchamp R. L., Pinney D. M., Keel S., Ueki K., Rutter J. L., Buckler A. J., Louis D. N. (1994) Cancer Res. 54, 5262–5264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar R., Atlas I. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 6599–6603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melamed D., Tiefenbrun N., Yarden A., Kimchi A. (1993) Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 5255–5265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee H. Y., Dohi D. F., Kim Y. H., Walsh G. L., Consoli U., Andreeff M., Dawson M. I., Hong W. K., Kurie J. M. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 101, 1012–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L., Gao L., Li Y., Lin G., Shao Y., Ji K., Yu H., Hu J., Kalvakolanu D. V., Kopecko D. J., Zhao X., Xu D. Q. (2008) Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 559–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choubey D., Li S. J., Datta B., Gutterman J. U., Lengyel P. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 5668–5678 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J., Chatterjee-Kishore M., Staugaitis S. M., Nguyen H., Schlessinger K., Levy D. E., Stark G. R. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 939–947 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bromberg J. F., Wrzeszczynska M. H., Devgan G., Zhao Y., Pestell R. G., Albanese C., Darnell J. E., Jr. (1999) Cell 98, 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun P., Nallar S. C., Kalakonda S., Lindner D. J., Martin S. S., Kalvakolanu D. V. (2009) Oncogene 28, 1339–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang B., Peng Z. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28734–28737 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cánepa E. T., Scassa M. E., Ceruti J. M., Marazita M. C., Carcagno A. L., Sirkin P. F., Ogara M. F. (2007) IUBMB Life 59, 419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bostock C. J., Prescott D. M., Kirkpatrick J. B. (1971) Exp. Cell Res. 68, 163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu J., Angell J. E., Zhang J., Ma X., Seo T., Raha A., Hayashi J., Choe J., Kalvakolanu D. V. (2002) J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 22, 1017–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson R. J. (2003) Proteins and Proteomics: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindner D. J., Borden E. C., Kalvakolanu D. V. (1997) Clin. Cancer Res. 3, 931–937 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.