Abstract

Yersinia enterocolitica (Ye) is a Gram-negative bacterium; Ye serotype O:3 expresses lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with a hexasaccharide branch known as the outer core (OC). The OC is important for the resistance of the bacterium to cationic antimicrobial peptides and also functions as a receptor for bacteriophage φR1-37 and enterocoliticin. The biosynthesis of the OC hexasaccharide is directed by the OC gene cluster that contains nine genes (wzx, wbcKLMNOPQ, and gne). In this study, we inactivated the six OC genes predicted to encode glycosyltransferases (GTase) one by one by nonpolar mutations to assign functions to their gene products. The mutants expressed no OC or truncated OC oligosaccharides of different lengths. The truncated OC oligosaccharides revealed that the minimum structural requirements for the interactions of OC with bacteriophage φR1-37, enterocoliticin, and OC-specific monoclonal antibody 2B5 were different. Furthermore, using chemical and structural analyses of the mutant LPSs, we could assign specific functions to all six GTases and also revealed the exact order in which the transferases build the hexasaccharide. Comparative modeling of the catalytic sites of glucosyltransferases WbcK and WbcL followed by site-directed mutagenesis allowed us to identify Asp-182 and Glu-181, respectively, as catalytic base residues of these two GTases. In general, conclusive evidence for specific GTase functions have been rare due to difficulties in accessibility of the appropriate donors and acceptors; however, in this work we were able to utilize the structural analysis of LPS to get direct experimental evidence for five different GTase specificities.

Keywords: Bacteria, Bacteriophage, Carbohydrate Biosynthesis, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Oligosaccharide, Receptors, Yersinia enterocolitica

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, represents one of the main virulence factors, and is thus studied extensively. LPS is composed of a lipid anchor (lipid A) and a carbohydrate moiety that can be subdivided into the core oligosaccharide and the O-specific polysaccharide (OPS).3 In the case of Enterobacteriaceae, the core oligosaccharide may be further divided into the inner and outer core (OC). The surface-exposed parts of LPS can also provide different receptor structures for bacteriophages (1).

Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 (Ye O:3) is a human pathogen causing yersiniosis that is usually a diarrheal disease. A special characteristic in Ye O:3 is that both OPS and OC are linked to the lipid A core, and this has made it possible to construct mutants expressing different combinations of OPS and OC (2). The Ye O:3 OPS and OC structures are important to the virulence of the pathogen (3, 4). In addition, we have shown that OC plays an important role in the resistance to antimicrobial peptides, key weapons of the innate immune system, and outer membrane integrity (4).

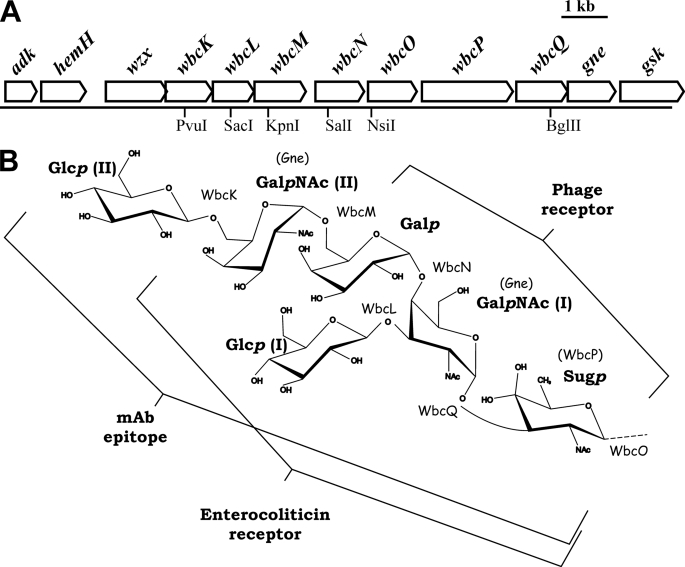

The OC hexasaccharide is composed of two d-glucopyranoses (d-Glcp), one d-galactopyranose (d-Galp), one 2-acetamido-2,6-dideoxy-d-xylo-hex-4-ulopyranose (Sugp, present in two forms, i.e. possessing either a keto or, due to the addition of water, a diol group at C4), and two 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-galactopyranose (GalpNAc) residues (5, 6). Biosynthesis of the Ye O:3 OC is believed to proceed similar to the biosynthesis of heteropolymeric OPS (7), i.e. by sequential transfer of sugar residues to the carrier-lipid undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P). As soon as the correct NDP-sugar precursors have been synthesized, the sugar residues are transferred one by one to a growing sugar chain on the Und-P. The initiation reaction to transfer Sugp-1-P onto Und-P should be catalyzed by a polyisoprenyl phosphate N-acetylhexosamine 1-phosphate-type priming GTase followed by five different GTases to generate the five glycosidic linkages of the outer core hexasaccharide.

The OC gene cluster has been cloned and sequenced (7). The Ye O:3 OC gene cluster expressed by plasmid pRV16NP fully restores OC expression of Ye O:3 strain that has the OC gene cluster deleted from the genome. pRV16NP also allows OC expression in heterologous hosts such as Escherichia coli (8). According to the sequence data, functions for the nine different gene products of the OC gene cluster were postulated (4, 7, 9–12).

However, only two gene products have been experimentally documented, i.e. the gne gene product, which is a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-4-epimerase (EC 5.1.3.7) (13), and the wbcP gene product, which is a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4,6-dehydratase involved in the biosynthesis of Sugp (5). For the rest of the genes, the wzx gene is postulated to encode a flippase translocating the Und-P-linked oligosaccharide through the inner membrane (6), whereas the remaining six genes wbcKLMNOQ are postulated to encode the five different GTases and the priming transferase needed to form the unique linkages connecting the monosaccharides of the OC hexasaccharide during the biosynthesis of OC onto Und-P (7).

GTases have been classified to sequence-based families by Campbell et al. (14), and the classification has been further developed by Coutinho et al. (15). The continuously updated information is available in the Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy).

In the glycosylation reaction, the stereochemistry at the C1 position of the donor sugar (here UDP-sugar) can remain or change. According to that, the GTases are either retaining or inverting, respectively. However, a reliable prediction of the catalytic mechanism (inverting or retaining) is not always possible based on sequence comparison alone (16).

According to the solved x-ray structures, GTase folds have been observed to consist primarily of α/β/α sandwiches. Added to this, GTases seem to mainly fall in two structural superfamilies as follows: the GT-A and GT-B. Inverting and retaining GTases are found in both superfamilies.

GT-A family GTases seem to have two characteristic regions. The first region (100–120 N-terminal residues) corresponds to the Rossmann-type nucleotide binding domain (α/β/α sandwich), and it is terminated by a general feature of the GT-A family, the DXD motif. The DXD motif has been shown to interact with the phosphate groups of the nucleotide donor through the coordination of a divalent cation, typically Mn2+. The C-terminal portion of the GT-A GTase is highly variable, mostly dedicated to the recognition of the acceptor, but a common β-α-α structural motif forming a part of the active site is seen. In inverting enzymes, the presumed catalytic base has been proposed in this region. The ratio of loops to secondary elements is high in GTases, and the flexible loops appear to be important for the substrate binding (16).

Ye O:3 LPS serves as a receptor for bacteriophages ϕR1-37 and ϕYeO3-12, the former uses OC (8) and the latter uses the OPS as a receptor (17). Enterocoliticin is a channel-forming bacteriocin produced by Y. enterocolitica 29930 (biogroup 1A; serogroup O:7,8) that also uses the Ye O:3 OC as its receptor (18); it kills enteropathogenic strains of Y. enterocolitica belonging to serogroups O:3, O:5,27, and O:9 (19). Finally, the monoclonal antibody (mAb) 2B5 also recognizes the OC hexasaccharide (5, 20). The structural OC requirements for these specificities have not been characterized previously.

In this study, we assign the individual catalytic specificities for all the six transferases needed for the biosynthesis of the Ye O:3 OC and establish the exact order by which they build the hexasaccharide. We used in silico modeling to identify catalytic residues of WbcK and WbcL and proved the predictions by site-directed substitutions of the residues. In addition, we analyzed the contribution of OPS and OC to polymyxin B resistance and demonstrated the minimum structural OC requirements for the interactions of bacteriophage ϕR1-37, enterocoliticin, and mAb 2B5. To our knowledge, there are no GTases with the equivalent specificities characterized so far.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Culture Conditions

Bacterial strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Yersinia strains were grown in tryptic soy broth at room temperature (20–25 °C) and E. coli strains in Luria Broth at 37 °C. Luria agar was used for all solid cultures. When required, appropriate antibiotics were added (20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 100 μg/ml kanamycin, and 12.5 μg/ml tetracycline).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain/plasmid | Genotype | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Y. enterocolitica | ||

| 6471/76 (=YeO3) | Wild type strain, patient isolate | 50 |

| 6471/76-c (=YeO3-c) | Virulence plasmid-cured derivative of 6471/76 | 50 |

| YeO3-R1 | Rough (OPS negative) derivative of YeO3-c | 3 |

| YeO3-c-wbcN1 | YeO3-c wbcN1 (the wbcN gene interrupted by the modified SalI site) | 21 |

| YeO3-c-wbcN1-R | Rough (OPS negative) derivative of YeO3-c-wbcN1 | This work |

| YeO3-wbcO1 | YeO3 wbcO1 (the wbcO gene interrupted by the modified NsiI site) | 21 |

| YeO3-wbcO1-R | Rough (OPS negative) derivative of YeO3-wbcO1 | This work |

| YeO3-c-wbcQ1 | YeO3-c wbcQ1 (the wbcQ gene interrupted by the modified BglII site) | 21 |

| YeO3-c-wbcQ1-R | Rough (OPS neg) derivative of YeO3-c-wbcQ1 | This work |

| YeO3-c-OC | Δ(wzx-wbcQ), derivative of YeO3-c | 2 |

| YeO3-c-OCR | Rough (OPS negative) derivative of YeO3-c-OC | 2 |

| E. coli | ||

| C600 | thi thr leuB tonA lacY supE | 51 |

| DH10B | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC), φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74, deoR, recA1 endA1 araΔ139 Δ(ara, leu)7697 galU, galK λ−rpsL nupG λ−tonA | Invitrogen |

| NovaBlue(DE3) | Novagen | |

| JM109 | F′ traD36 proA+B+lacIq Δ(lacZ)ΔM15/Δ(lac-proAB) glnV44 e14−gyrA96 recA1 relA1 endA1 thi hsdR17 | 52 |

| HB101/pRK2013 | Conjugation helper strain, kanR | 53 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRV16NP | YeO3 OC gene cluster cloned in pTM100, clmR | 8 |

| pRV16NPwbcK2 | wbcK-1 a nonpolar frameshift mutation introduced by a 4-bp deletion at codon 142 overlapping the PvuI site of wbcK | This work |

| pRV16NPwbcL1 | wbcL-1 a nonpolar frameshift mutation introduced by a 4-bp deletion at codon 142 overlapping the SacI site of wbcL | This work |

| pRV16NPwbcM1 | wbcM-1 a nonpolar frameshift mutation introduced by a 4-bp deletion at codon 106 overlapping the KpnI site of wbcM | This work |

| pRV16NPwbcQ1 | wbcQ-1 a nonpolar frameshift mutation introduced by a 4-bp insertion at codon 219 overlapping the BglII site of wbcO | This work |

| pYeO3wbcK | wbcK gene cloned as a PCR fragment into pET28a | This work |

| pYeO3wbcL | wbcL gene cloned as a PCR fragment into pET28a | This work |

| pYeO3wbcM | wbcM gene cloned as a PCR fragment into pET28a | This work |

| pYeO3wbcQ | wbcQ gene cloned as a PCR fragment into pET28a | This work |

| pTM100wbcO | wbcO gene cloned into pTM100 | This work |

| pTM100wbcN | wbcN gene cloned into pTM100 | This work |

| pYeO3wbcK-Ala | wbcK1;D182A derivative of pYeO3wbcK | This work |

| pYeO3wbcK-Ser | wbcK2;D182S derivative of pYeO3wbcK | This work |

| pYeO3wbcL-Ala | wbcL1;E181A derivative of pYeO3wbcL | This work |

| pYeO3wbcL-Gln | wbcL2;E181Q derivative of pYeO3wbcL | This work |

| pYeO3wbcL-Thr | wbcL3;E181T derivative of pYeO3wbcL | This work |

| pET28a | kanR cloning vector, including cleavable N-terminal His tag | Novagen |

| pTM100 | clmR tetR; mobilizable cloning vector | 54 |

Construction of Rough Derivatives of Chromosomal OC Mutant Strains

To obtain OPS-negative (=rough) derivatives of different Ye O:3 strains, we used phage ϕYeO3-12 selection. Strains YeO3-c-wbcN1-R, YeO3-wbcO1-R, and YeO3-c-wbcQ1-R were isolated as spontaneous ϕYeO3-12-resistant mutants of strains YeO3-c-wbcN1, YeO3-wbcO1, and YeO3-c-wbcQ1 (21), respectively, as described earlier (7). The OPS negative phenotypes were confirmed by DOC-PAGE.

Construction of OC Mutants

Strains expressing mutated OC genes were constructed by mutating the OC genes of plasmid pRV16NP individually as described below. Plasmid pRV16NP contains the OC gene cluster cloned into plasmid vector pTM100 so that it is constitutively transcribed under the tetracycline promoter of the vector. The obtained plasmids pRV16NPwbcK2, pRV16NPwbcL1, pRV16NPwbcM1, and pRV16NPwbcQ1 were mobilized from the E. coli host by triparental conjugation into the OC negative Y. enterocolitica strain YeO3-c-OC-R using E. coli HB101/pRK2013 as a helper strain as described earlier (2).

To mutate the OC genes, single restriction sites were identified within each gene (Table 2). These sites were mutated as follows: either by (i) removal of overhangs by mung bean nuclease according to the instructions by the supplier (New England Biolabs); (ii) removal of 3′-overhangs by T4 DNA polymerase, or (iii) fill in 5′-overhangs by T4 DNA polymerase according to the instructions by the supplier (Promega). Plasmid pRV16NP was digested with selected restriction enzyme, blunted with one of the options above, and then self-ligated. Each mutated gene and corresponding restriction site as well as the enzyme used for blunting and the name of the resulting plasmid are listed in Table 2. All the mutations were designed to change the reading frame of the target gene.

TABLE 2.

Strategies for construction of nonpolar mutations in OC gene cluster

| Gene, range in accession no. Z47767 | Restriction enzyme, position | Inactivation by | Plasmid construct |

|---|---|---|---|

| wbcK, 3461..4417 | PvuI, 3886 | Overhang blunting by T4 DNA polymerase | |

| wbcL, 4419..5297 | SacI, 4845 | Overhang blunting by T4 DNA polymerase | pRV16NPwbcL1 |

| wbcM, 5306..6382 | KpnI, 5625 | Overhang blunting by T4 DNA polymerase | pRV16NPwbcM1 |

| wbcN, 6575..7609 | SalI, 6900 | Overhang fill in by T4 DNA polymerase | pDMS8a |

| wbcO, 7680..8705 | NsiI, 7757 | Overhang blunting by T4 DNA polymerase | pDMS9a |

| wbcQ, 10758..11807 | BglII, 11414 | Overhang fill in by T4 DNA polymerase | pRV16NPwbcQ1 pDMS6a |

a Construction of these suicide vectors to introduce the nonpolar mutations by allelic exchange into the genome of Ye O:3 have been described previously (21).

Construction of OC Gene Expression Plasmids

Plasmids pYeO3wbcK, pYeO3wbcL, pYeO3wbcM, and pYeO3wbcQ were generated by amplifying genes wbcK, wbcL, wbcM, and wbcQ of YeO3-c by PCR with primer pairs shown in supplemental Table S1 using Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) and following PCR cycles 98 °C for 30 s (98 °C for 11 s, 53 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s) 35 times at 72 °C for 7 min. The obtained PCR fragments were purified with quantum prep PCR Kleen kit (Bio-Rad), digested with enzymes whose recognition sites were present in primers and are shown in supplemental Table S1, and ligated with pET28a that had been digested with the same restriction enzymes and treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase.

To clone wbcN, the 1.8-kb NcoI fragment of pRV16NP was cloned into NcoI site of pTM100, and to clone wbcO, the 2.1-kb MscI/XmnI fragment of pRV16NP was cloned into EcoRV site of pTM100. The constructed plasmids were named pTM100wbcN and pTM100wbcO, respectively.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis of the wbcK and wbcL was performed by PCR as described previously (13). Briefly, plasmids pYeO3wbcK and pYeO3wbcL were used as templates, and the desired mutations were introduced by the primer pairs described in supplemental Table S1. PCR was carried out using Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) and the following PCR cycles: 98 °C for 30 s (98 °C for 10 s, 48 or 43 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 3 min) 35 times and 72 °C for 7 min. The obtained PCR fragments were gel-purified, phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase, ligated, and finally subjected to DpnI digestion to break down any remaining template plasmid. The ligated PCR products were transformed to E. coli JM109, and the generated substitutions were confirmed by sequencing. The constructed plasmids were named pYeO3wbcK-Ala, pYeO3wbcK-Ser, pYeO3wbcL-Ala, pYeO3wbcL-Gln, and pYeO3wbcL-Thr.

In Trans Complementation Studies

The OC is expressed in E. coli transformed with pRV16NP carrying the OC gene cluster (8), and we used this possibility in trans-complementation experiments. The two plasmids carrying the wild type gene in pET28 and the corresponding pRV16NPwbc-mutant were co-introduced to competent E. coli NovaBlue(DE3) cells by electroporation. To express the wild type gene, the T7 RNA polymerase activity of the host strain was induced by 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and the OC-phenotype was analyzed as described below.

To experimentally test the effects of the substitution mutations of WbcK and WbcL on the enzymatic activity, the ability of the mutated proteins to complement the wbcK and wbcL mutants, respectively, was assayed. To this end, plasmids pYeO3wbcK-Ala and pYeO3wbcK-Ser were co-introduced with pRV16NPwbcK2 and plasmids pYeO3wbcL-Ala, pYeO3wbcL-Gln and pYeO3wbcL-Thr were co-introduced with pRV16NPwbcL, respectively, to NovaBlue(DE3). The gene expression was induced by isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside as described above, and the OC-phenotypes were analyzed by DOC-PAGE and immunoblotting as described below. The expression of the His-tagged proteins was analyzed by immunoblotting using the monoclonal mouse anti-polyhistidine antibody HIS-1 (H1029, Sigma).

To study the complementation of the wbcN and wbcO mutants, plasmids pTM100wbcN and pTM100wbcO were introduced to strains YeO3-c-wbcN1-R and YeO3-wbcO1-R, respectively, by triparental conjugation using as helper strain E. coli HB101/pRK2013, as described earlier (22).

DOC-PAGE Analysis

LPS phenotypes were analyzed by silver-stained DOC-PAGE of isolated LPS samples as described previously (7, 23). The reactivity of mAb 2B5 was tested by immunoblotting LPS samples from DOC-PAGE to nitrocellulose filters as described previously (2).

Lipopolysaccharide Isolation and Chemical Analysis

The LPSs were extracted with hot phenol/water (24) followed by enzymatic treatment (DNase, RNase (37 °C, 12 h), and proteinase K (56 °C, 12 h)) and ultracentrifugation (two times at 105,000 × g, 4 °C, 12 h). Sugar analyses were performed as described previously (25, 26). Methylation was carried out according to Ciucanu and Kerek (27). For reduction of Sugp, LPS was treated with anhydrous hydrazine (37 °C, 30 min). The core oligosaccharide from YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcK2 was obtained after acetate buffer hydrolysis (pH 4.4, 100 °C, 5 h). Electrospray ionization Fourier-transformed cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (ESI FT-ICR MS) experiments were performed as described previously (5).

ϕR1-37 and Enterocoliticin Sensitivity Assays

Different strains were tested for their ϕR1-37 and enterocoliticin sensitivities by pipetting 5 μl of serial dilutions of phage or enterocoliticin stocks (2 × 109 plaque-forming units/ml and 2 × 106 activity units/ml, respectively) on a freshly grown and dried bacterial lawn and observing the formation of a clear lysis zone after 24 h of incubation.

Radial Diffusion Assay

Strains expressing different truncated OCs were tested for their polymyxin B sensitivity as described earlier (28, 29). Briefly, an overlay gel that contained 1% (w/v) agarose (SeaKem LE agarose, FMC, Rockland, ME), 2 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), and 0.3 mg of tryptic soy broth (Oxoid) powder per ml was equilibrated at 50 °C and inoculated with the different bacteria to a final concentration of 5 × 105 colony-forming units per ml of molten gel. This gel was poured into standard square Petri dishes (10 × 10 × 1.5 cm), and after solidification, small wells of 15-μl capacities were carved. Aliquots of 10 μl of polymyxin B were added to the wells, and plates were incubated for 3 h at the bacterial growth temperature. After that, a 30-ml overlay gel composed of 1% agarose and 6% tryptic soy broth powder in water was poured on top of the previous one, and the plates were incubated at the bacterial growth temperature. After 18 h, the diameters of the inhibition halos were measured to the nearest 1 mm, and after subtracting the diameter of the well, they were expressed in inhibition units (10 units = 1 mm). The minimal inhibitory concentration was estimated by performing linear regression analysis (units versus log10 concentration) and determining the x axis intercepts (28, 29). All the experiments were run in quadruplicate on three independent occasions.

Sequence Comparison and Comparative Modeling

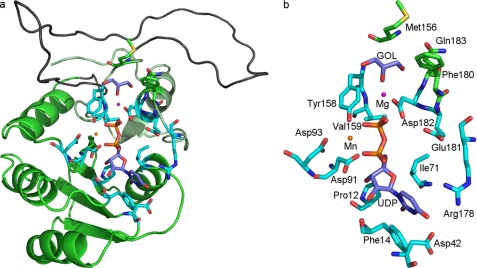

Protein sequences and structures similar to WbcK and WbcL were searched from the nonredundant protein sequence database and protein structure database (Protein Data Bank, respectively, using PSI-BLAST (blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Because the sequence identities of WbcK and WbcL with the putative GTase from Bacteroides fragilis (Protein Data Bank code 3BCV) and of the nucleotide-diphospho-sugar transferase (SpsA) from Bacillus subtilis (30) (Protein Data Bank code 1QGQ) are low, the structures were superimposed using the program VERTAA in the Bodil visualization and modeling package (31) to find out structurally conserved areas. The 3BCV sequence was aligned with WbcK and sequences most similar to both of them. Another alignment was separately done with the SpsA and similar sequences. The individual sequence alignments were then combined with the previously generated structure-based sequence alignment of 3BCV and SpsA. Finally, WbcL was aligned with similar sequences, and the WbcL alignment was combined to the previously constructed multiple sequence alignment with the sequence of Methanosphaerula palustris E1-9c family 2 GTase (PF00535), which could be aligned with both WbcK and WbcL. All the sequence comparisons were done using the program MALIGN in Bodil (32, 33). Structural model of WbcK (residues 1–199) was made with MODELLER 9.7 (34) based on the multiple-sequence alignment. The SpsA crystal structure in complex with UDP, magnesium, manganese, and glycerol (1QGQ) was used as the structural template to allow the analysis of the catalytic center of WbcK. Fig. 3 was produced with PyMOL (version 1.2rl (35)), and the labels were with Gimp2.6. The figure containing the multiple-sequence alignment (supplemental Fig. S1) was produced using ESPript 2.2 implemented in ENDscript 1.1 (36).

FIGURE 3.

Three-dimensional model of WbcK. a, overall fold; b, closer view of the active site structure. The N-terminal GT-A domain is colored green and the conserved helix of the C-terminal domain with lighter green. The most unreliable area of the fold is colored gray. Glycerol (GOL) is bound into the acceptor sugar site in the SpsA x-ray structure and was modeled to the WbcK model. The residues involved in UDP, metal ion, and glycerol binding are shown as sticks. The carbon atoms of residues involved in UDP and metal ion binding are colored cyan, and those of residues in the acceptor binding site are colored green.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To study the roles of predicted GTases encoded in the OC gene cluster of Ye O:3, the LPS phenotypes and structures of strains missing the respective gene products were determined. To this end, two sets of isogenic mutants were used, i.e. Ye O:3 strains carrying chromosomal wbc gene mutations and strain YeO3-c-OC-R (see Table 1) carrying plasmid pRV16NP or its derivatives having individual wbc genes inactivated. To confirm that the observed LPS phenotypes were due to the inactivation of the target gene, the mutants were complemented in trans by the respective wild type gene.

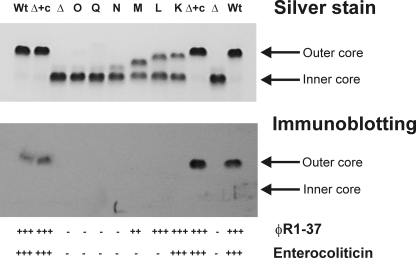

The LPS of the strains was first analyzed by DOC-PAGE and immunoblotting (Fig. 2). Next, the sugar composition of the expressed OC was analyzed using LPS isolated from respective mutants; the LPS structures were determined chemically and by mass spectrometry (Table 3, and supplemental Tables S2 and S3, and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). Finally, the mutants were tested for bacteriophage ϕR1-37 and enterocoliticin sensitivity and the mAb 2B5 reactivity (Fig. 2, bottom panel).

FIGURE 2.

Silver-stained DOC-PAGE and immunoblotting analysis of LPSs of OC mutants together with phage and enterocoliticin sensitivities of OC mutants. Upper panel, silver staining; middle panel, immunoblotting with mAb 2B5; bottom panel, phage and enterocoliticin sensitivities. Lanes are as follows: Wt, YeO3-R1; Δ+c, YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NP; Δ, YeO3-c-OC-R; O, YeO3-wbcO1-R; Q, YeO3-c-wbcQ1-R; N, YeO3-c-wbcN-R1; M, YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcM1; L, YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcL1; K, YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcK2.

TABLE 3.

Monoisotopic molecular masses of the most abundant molecular ions identified in LPS of Ye O:3 OC mutants as determined from charge deconvoluted ESI FT-ICR mass spectra obtained in the negative ion mode

| Mass | Componentsa | Strain |

|---|---|---|

| units | ||

| 4687.31 | LAhex + 2 Ara4N + IC + OC | YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NP |

| 4525.21 | LAhex + 2 Ara4N + IC + OC − Hex | YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcK2 |

| 4363.19 | LAhex + 2 Ara4N + IC + OC − 2 Hex | YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcL1 |

| 4160.06 | LAhex + 2 Ara4N + IC + OC − 2 Hex-HexNAc | YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcM1 |

| 3998.03 | LAhex + 2 Ara4N + IC + OC − 3 Hex-HexNAc | YeO3-c-wbcN1 |

| 3329.7 | LAhex + 1 Ara4N + IC | YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcQ1 |

| 3329.7 | LAhex + 1 Ara4N + IC | YeO3-c-wbcO1 |

a LAhex indicates hexa-acylated lipid A, including 2 HexN, 2 phosphates, and fatty acids 4 of 14:0(3-OH) and 1 each of 14:0 and 12:0.

As the OC structure contains two GalpNAc and two Glcp residues, for convenience we hereafter refer to the reducing-end proximal and distal GalpNAc residues present in the OC hexasaccharide as GalpNAc(I) and GalpNAc(II) and to the reducing-end proximal and distal Glc residues as Glcp(I) and Glcp(II) (see also Fig. 1), respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Ye O:3 LPS outer core. A, genetic organization of the OC gene cluster (nucleotide sequence GenBankTM accession number Z47767). The genes are drawn to scale, and locations of relevant restriction sites are indicated. B, structure of the OC hexasaccharide. The different enzymes involved in OC biosynthesis are indicated, i.e. the enzymes for the UDP-Sugp and UDP-GalpNAc biosynthesis are given in parentheses above the respective residues and the six GTases beside the catalyzed glycosidic linkages. The Glcp(I), Glcp(II), GalpNAc(I), and GalpNAc(II) residues are indicated. The minimal structures functioning as phage and enterocoliticin receptor and the mAb 2B5 epitope are also marked.

WbcK Is Glcp(II) Transferase

The strain YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcK2, which lacks the WbcK activity, expressed a minimally truncated OC as shown by DOC-PAGE analysis (Fig. 2, lane K). Plasmid pYeO3wbcK fully complemented in trans the mutation when expressed in E. coli NovaBlue(DE3)/pRV16NPwbcK2 and analyzed by DOC-PAGE.

Chemical analyses of the YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcK2 OC proved the lack of one Glcp residue. Methylation analysis of the sugar backbone obtained after acetate buffer hydrolysis revealed the presence of 3,4-substituted HexN (here GalpN(I)) and terminal (unsubstituted) HexN (here GalpN(II)). Thus, the missing residue was Glcp(II) (Table 3, supplemental Tables S2 and S3, supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). We called this OC chemotype OC5 (OC6 corresponded to WT OC having all six sugar residues). Based on the OC structure of Ye O:3 (36) together with DOC-PAGE and chemical analyses of YeO3-C-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcK2, we conclude that WbcK is a UDP-Glcp:Und-P-P-OC5-β-(1→6)-glucosyltransferase (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Catalytic specificities of the Ye O:3 OC GTases

| Transferase | Donor | Acceptor | Linkage | CaZy GT family |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WbcK | UDP-Glcp | Und-P-P-OC5 | β−(1→6)- | GT 2 |

| WbcL | UDP-Glcp | Und-P-P-OC4 | β−(1→3)- | GT 2 |

| WbcM | UDP-GalpNAc | Und-P-P-OC3 | α−(1→6)- | GT 4 |

| WbcN | UDP-Galp | Und-P-P-OC2 | α−(1→4)- | GT 4 |

| WbcQ | UDP-GalpNAc | Und-P-P-Sugp | α−(1→3)- | GT 4 |

| WbcO | UDP-Sugp | Und-P | Phosphodiester |

WbcL Is Glcp(I) Transferase

The LPS phenotype of strain YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcL1 in silver-stained DOC-PAGE showed a truncated OC (Fig. 2, lane L), slightly smaller than the OC5. The wbcL mutation was fully complemented in trans by plasmid pYeO3WbcL expressed in the E. coli NovaBlue(DE3)/pRV16NPwbcL1 background.

The ESI FT-ICR MS analysis of LPS isolated from the strain YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcL1 showed that the outer core region was composed of Sugp, 2 HexNAc (here GalpNAc), and Hex (here Galp) missing two Glcp residues (OC4 chemotype) (Table 3, supplemental Tables S2 and S3, supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). Based on LPS analyses, we conclude that wbcL encodes for the UDP-Glcp:Und-P-P-OC4-β-(1→3)-glucosyltransferase that adds Glcp (I) to the OC (Table 4).

WbcM Is GalpNAc(II) Transferase

When the LPS expression of strain YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NP-wbcM1 was analyzed, a truncated form of OC was seen in the silver-stained DOC-PAGE that migrated faster than OC4. The pYeO3wbcM fully complemented in trans the truncated OC phenotype of E. coli NovaBlue(DE3)/pRV16NPwbcM1.

The ESI FT-ICR MS analysis of YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NP-wbcM1 LPS revealed the presence of an OC containing Sugp, HexNAc (here GalpNAc), and one Hex residue (Table 3, supplemental Tables S2 and S3, supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). The identity of the hexose was determined by GC as Galp. Thus, this core represented the OC3 chemotype, and its analyses proved that WbcM is a UDP-GalpNAc:Und-P-P-OC3-α-(1→6)-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (Table 4).

WbcN Is Galp Transferase

The OC phenotype of wbcN mutant was analyzed from a strain with the inactivated chromosomal wbcN gene. To facilitate chemical and phenotypic analysis, a spontaneous rough mutant of YeO3-c-wbcN1 was isolated using bacteriophage ϕYeO3–12. DOC-PAGE analysis showed that both wbcN mutants, YeO3-c-wbcN1 and YeO3-c-wbcN1-R, expressed truncated OC smaller than OC3. Chemical analyses identified Sugp and one GalpNAc residue as the constituents of the truncated outer core in YeO3-c-wbcN1 (OC2 chemotype). To complement the mutation, wbcN was cloned into pTM100 and introduced to YeO3-c-wbcN1-R by triparental conjugation. It fully restored the WT OC chemotype (data not shown). Thus, wbcN encodes for UDP-Galp:Und-P-P-OC2-α-(1→4)-galactosyltransferase (Table 4).

WbcQ Is GalpNAc(I) Transferase and WbcO Is the Priming Transferase

As a demonstration that the mutation analysis of pRV16NP derivatives in YeO3-c-OC-R background gives identical results with the analysis of chromosomal mutations, we constructed two strains. Strain YeO3-c-wbcQ1-R carried a chromosomally inactivated wbcQ gene and YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcQ1 contained the mutated gene in the plasmid. DOC-PAGE analysis of the LPSs showed the same OC negative chemotype in both strains.

ESI FT-ICR MS demonstrated that only the inner core was present in the LPS of YeO3-c-wbcQ1, YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcQ1, and YeO3-c-wbcO1 (Table 3, supplemental Tables S2 and S3, and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). The OC phenotype of E. coli NovaBlue(DE3)/pRV16NPwbcQ1 was complemented with pYeO3wbcQ and of the OC in YeO3-wbcO1-R by plasmid pYeO3wbcO. However, bioinformatic predictions strongly suggested that WbcO was the priming and WbcQ the second transferase (here UDP-GalNAc:Und-P-P-Sugp-α-(1→3)-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase) in OC biosynthesis. Additionally, according to the sequence analysis WbcO was membrane-integrated (37), which would argue for its role as the priming transferase. Because the results from the distal transferase mutants showed that the efficiency of OC2-OC5 substitutions was greatly reduced, the amount of OC containing only Sugp (OC1) in wbcQ mutants could be below the detection level of MS. The presence of Sugp could not be observed in GC, and thus the analyzed LPS from YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcQ1 was treated with hydrazine that would result in the reduction of Sugp to QuipN (5). Analysis by GC proved the presence of QuipN in the reduced LPS of YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NPwbcQ1; the amount of QuipN was ∼10% that of LPS from YeO3-c-OC-R/pRV16NP containing the complete core region. As expected, no QuipN was detected in the wbcO LPS. This confirmed the hypothesis that WbcQ is indeed UDP-GalpNAc:Und-P-P-Sugp-α-(1→3)-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase and WbcO functions as a priming GTase, i.e. UDP-Sugp:Und-P transferase (Table 4). However, the latter still remains to be proven experimentally. The reason why OC1 is very poorly expressed could be due to low efficiency either of Wzx, the flippase that would translocate the Und-P-P-OC1 to the periplasmic side of the inner membrane, or of the OC ligase that would ligate the OC1 to the inner core-lipid A moiety.

In summary, we have defined the linkage specificities to six different transferases and provide direct experimental evidence for five of them (Table 4). To our knowledge there are no GTases with the very same specificities characterized so far.

Building Order of the OC Hexasaccharide

Our results indicate that the Galp- and the GalpNAc(II) residues are transferred prior to the Glcp(I) residue. Furthermore, according to these results, the Glcp(I) residue has to be added by WbcL before WbcK is able to add the Glcp(II) residue. Similar strict order of GTase functions has been shown for the growing lipooligosaccharide molecule of Moraxella catarrhalis; addition of specific sugar residues is critical to the enzymes that act further downstream in the biosynthesis of the full-length lipooligosaccharide molecule (38).

Comparison of OC GTases to Other GTases

BLAST search of the five OC GTases against nonredundant protein database sequences revealed significant similarities to many putative GTases; however, only rarely experimental or even indirect evidence for the linkage specificity is available. In addition, only a few three-dimensional structures of the GTases related to OC GTases have been determined; SpsA is one of the three enzymes from CAZy family 2 and altogether six enzymes from CAZy family 4.

WbcK and WbcL

According to CAZy classification, GTases WbcK and WbcL, responsible for the transfer of the Glcp(II) and Glcp(I) residues, respectively, belong to the GTase family 2 (GT-2). This family is a diverse family, classified as inverting according to the stereochemistries of the reaction substrates and products. Klebsiella pneumoniae WabM (CAZy GT-2) is 36% identical and 56% similar to WbcK, and it is one of the few GTases that have experimental evidence for its specificity. According to MS analysis of LPS of the wabM strain, WabM is responsible for the transfer of a Glc residue to the O-6 position of a Glc residue in K. pneumoniae type 2 outer core (39). Interestingly, the donor of the Glc residue and the linkage position are the same as for WbcK, but the acceptor is different (Fig. 1).

WbcL shows similarity to many CAZy GT-2 GTases as follows: WclU of E. coli, WffL of Shigella dysenteriae, and many capsule biosynthesis proteins such as CpsN(V) of Streptococcus agalactiae, Cps1K Vibrio cholerae, and CpsO of Streptococcus, but there is no information of their linkage-specific functions.

Modeling of WbcK and WbcL Three-dimensional Structures

We find WbcK and WbcL GTases very interesting as they both use UDP-Glcp to add Glcp to GalpNAc, but the linkages β-(1→6)-for WbcK and β-(1→3)-for WbcL and the neighborhoods of the GalpNAc-residues are different. To elucidate the basis of their functional differences, we decided to attempt their three-dimensional modeling. An extensive multiple sequence alignment was first performed to evaluate sequence conservation (supplemental Fig. S1) and to assist the comparative modeling of WbcK. The active site of the obtained WbcK model was then compared with the known GTase structures to reveal the residues in the UDP-Glc donor and the acceptor binding sites. The obtained three-dimensional model of WbcK includes residues 1–238 (Fig. 3a) and thus lacks the C-terminal residues 239–318. It was constructed using the three-dimensional structure of SpsA in complex with UDP, magnesium, manganese, and glycerol (1QGQ). Even though 3BCV would have been much closer to WbcK than SpsA (23% versus 10% identity, respectively) we chose SpsA because the three-dimensional structure of 3BCV is based on a native structure without any ligands. However, the N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain in the WbcK model is reliable because the structural alignment of SpsA and 3BCV and a multiple sequence alignment were used to align SpsA with WbcK. Furthermore, the sequence identity of the N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (residues 1–93) in WbcK to the known three-dimensional structures is much higher than the overall sequence identity, i.e. 20% to SpsA and 36% to 3BCV. Additionally, the secondary structure elements in SpsA match well with those predicted for WbcK, and the three-dimensional fold of the GT-A domains is known to be highly conserved (30). The reliability of the WbcK model is lowest in the highly variable area (shown in gray in Fig. 3) between the N-terminal domain and the last helices in the C-terminal domain.

Asp-182 Is Predicted to be the Catalytic Base Residue in WbcK

In glycosylation reactions catalyzed by the inverting GTases, the nucleophile of the acceptor is thought to attack the C1 of the donor in Sn1-like reaction leading to inversion of the stereochemistry. In the reaction catalyzed by WbcK, it would mean that the –OH of the C6 of the GalpNAcII (of the OC5-Und-P) would attack the C1 of UDP-Glcp. A general base of the catalyzing enzyme is thought to assist in deprotonating the nucleophilic hydroxyl of the acceptor (in WbcK reaction of the previously mentioned –OH of C6).

In our sequence alignment, the most important residues in the UDP-Glcp-binding site of the N-terminal domain are invariant (Asp-91 and Asp-93 in the signature DXS sequence; Asp-42) or replaced by similar residues (Phe-14) (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S1). The C-terminal domain is highly variable in GT-2 family (supplemental Fig. S1). The catalytic base residue, an aspartate in GT-2 family, is located in the C-terminal domain and was identified to be Asp-191 in SpsA based on the location of the glycerol molecule mimicking the acceptor sugar (30). Accordingly, the corresponding residue is an aspartate in WbcK (Asp-182) as well (Fig. 3). In addition to Asp-182, the acceptor sugar site is lined by residues Met-156, Phe-180, and Gln-183 in WbcK (Fig. 3). Asp-182 is located in the acceptor recognition-associated conserved ED motif shown to be important for the activity of Salmonella enterica GTase WbbE (30).

Glu-181 Is Predicted to Be the Catalytic Base Residue in WbcL

As WbcL seems to be inverting GTase, the reaction mechanism is predicted to be similar to WbcK-catalyzed reactions. So the nucleophile of the acceptor would be the –OH of the C3 of the GalpNAcI (of the OC4-Und-P) and the acceptor would be again the C1 of UDP-Glcp. Based on the sequence analysis of WbcL-like proteins, the catalytic base residue in WbcL seems to be a glutamate that is conserved in all the WbcL-like proteins (Glu-181 in WbcL). Interestingly, in the human β-(1→3)-glucuronyltransferase I (CAZy family 43), the catalytic base has been verified to be a glutamate residue, which is located at the same position as Asp-191 in the SpsA structure (40). This is in accordance with the fact that WbcL similarly catalyzes a β-(1→3)-linkage.

WbcK Asp-182 and WbcL Glu-181 Are Necessary for the GTase Activities

The relevance of the predicted catalytic base residues (Asp-182 in WbcK and Glu-181 in WbcL) was tested by constructing the following substitutions: D182A and D182S for WbcK, and E181A, E181Q, and E181T for WbcL. All the constructed mutants lacked the corresponding GTase activity and were not able to complement the corresponding WbcK or WbcL mutant phenotypes in contrast to respective wild type constructs (supplemental Fig. S4). This allows us to conclude that Asp-182 of WbcK and Glu-181 of WbcL are relevant and most likely act as catalytic base residues in the GTase reactions.

WbcM, WbcN, WbcQ, and WbcO Comparisons

Transferases WbcM, WbcN, and WbcQ belong to GTase family 4 (GT-4) according to the CAZy classification. They are retaining GTases, and they seem to have GT-B-type topology. WbcM has similarity to Streptococcus oralis WefM GTase (CAZy GT-4) that is probably responsible for linking Gal to ribitol of co-aggregation receptor polysaccharides (41). In this case neither donor nor acceptor are the same as in WbcM-catalyzed reaction. For WbcN and WbcQ, there were no specifically characterized enzymes among the most similar ones found in Blast search.

Amino acids 90–240 of WbcO showed similarity to the putative GTase family 4 domain. As mentioned earlier, WbcO shares features with integral membrane proteins that catalyze carbohydrate polymer initiation reactions, and it gave the highest scores to the relatively well defined WbpL proteins of different Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotypes (O5, O6, and O11) that act as priming GTases in the biosynthesis of the LPS O-antigen (42). Price and Momany (43) have discussed in depth about catalytic mechanism and substrate specificity of different subfamilies, including the WbpL/WbcO subfamily.

Interestingly, the OPS structures of Salmonella O66 and E. coli O166 were established recently (44, 45), and Liu et al. (44) proposed GTase activities for the corresponding biosynthetic GTase genes weiABCD. Two of the glycosidic linkages found in Salmonella and E. coli OPS are identical to the ones in Ye O:3 OC, so we can concur with their hypothesis that WeiA (the WbcL homolog) is Glc-β-(1→3)-GalNAc GTase and WeiC (the WbcN homolog) is Gal-α-(1→4)-GalNAc GTase. WeiB (the WbcM homolog) is probably a Gal-α-(1→6)-Gal GTase differing from WbcM only with respect to the absence of the NAc-group of the donor sugar. Finally, WeiD (the WbcQ homolog) is likely to catalyze the GalNAc-β-(1→3)-GalNAc linkage as both the linkage and the donor are the same as for WbcQ; the acceptor for WbcQ is Sugp.

Structural Requirements for the Interaction of ϕR1-37, Enterocoliticin, and mAb 2B5

The Ye O:3 OC is recognized by mAb 2B5, and it serves as a receptor for ϕR1-37 and enterocoliticin. The Y. enterocolitica strains constructed in this work expressing LPS with different truncated forms of OC allowed further investigation of the receptor role of the OC. The results summarized in Fig. 2 indicate that the minimal structural requirements for these biological interactions are distinct.

The mAb 2B5 requires the complete core region (OC6) for the binding to the Ye O:3 OC epitope; the interaction is disturbed already when Glcp(II) of OC is missing. Lack of Glcp(II) does not affect the recognition by enterocoliticin, whereas ϕR1-37 recognizes OC3 containing just Sugp, GalpNAc, and Galp. Thus, the minimum requirement for the interaction between Ye O:3 OC and enterocoliticin is represented by OC5, whereas ϕR1-37 requires the expression of OC3. However, at present we cannot rigorously rule out that the deeper part of LPS on which OC is expressed may also form part of the receptor. In Ye O:3, the OC is β-(1→3)-linked via Sugp to the l-glycero-d-manno-heptopyranose(II) of the inner core (5).

Polymyxin B Sensitivity

Because both OPS and OC of Ye O:3 are linked to the lipid A core, we have the possibility to study mutants expressing different combinations of OPS and OC (2). We found that strains expressing OC are resistant to higher polymyxin B concentrations than OC negative strains (4, 46). Furthermore, we also established that Ye OPS from serotypes O:9 and O:3 contributes to polymyxin B resistance but only in the absence of OC (9, 46). Here, we aimed to define the minimal requirements of OC to confer full polymyxin B resistance and the possible contribution of OPS. The resistance of the strains to polymyxin B was temperature-dependent, and the minimal inhibitory concentrations were higher at room temperature than at 37 °C (Table 5). This is a general feature of Yersiniae (47–49), and the molecular bases of it are still poorly understood. In strains expressing OPS, all the mutants expressing truncated OC were more susceptible to polymyxin B than the wild type. However, the mutants were as susceptible as the full OC deletion mutant. The absence of OPS did not further increase the susceptibility of a given strain. In the set of strains expressing pRV16NP and its derivatives, similar results were observed (Table 5). Strains expressing truncated OCs were more susceptible than strains expressing whole OC, and the absence of OPS did not further increase the susceptibility. Collectively, these data suggest that a complete OC is needed to confer polymyxin B resistance. However, because in all the mutants roughly only half of the LPS molecules are expressing the truncated OC and the other half completely lacks OC, it is possible that this might be enough to turn the balance to increase susceptibility.

TABLE 5.

Polymyxin B sensitivity of different Ye O:3 mutants

| MIC polymyxin B (units/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Strain | 21 °Ca | 37 °Cb |

| YeO3 | 8.68 ± 0.05 | 5.24 ± 0.01 |

| YeO3-c-OC | 5.22 ± 0.15c | 3.78 ± 0.14d |

| YeO3-R1 | 8.32 ± 0.04 | 4.92 ± 0.54 |

| YeO3-c-OCR | 5.22 ± 0.04c | 4.78 ± 0.77 |

| YeO3-wbcO-R | 5.39 ± 0.21c | 3.24 ± 0.20d |

| YeO3-wbcO | 4.64 ± 0.99c | 3.33 ± 0.39d |

| YeO3-c-wbcN-R | 5.33 ± 0.47c | 3,72 ± 0.60d |

| YeO3-c-wbcN | 5.69 ± 0.12c | 2.77 ± 0.42d |

| YeO3-c-wbcQ-R | 4.11 ± 0.36c | 3.91 ± 0.44d |

| YeO3-c-wbcQ | 3.73 ± 0.50c | 2.83 ± 0.38d |

| YeO3-c-OCR/pRV16NP | 7.97 ± 0.63 | 5.74 ± 1.28 |

| YeO3-c-OC/pRV16NP | 6.53 ± 0.62 | 4.49 ± 0.46 |

| YeO3-c-OCR/pRV16NPwbcK2 | 4.02 ± 0.52e | 2.63 ± 0.37f |

| YeO3-c-OC/pRV16NPwbcK2 | 3.83 ± 0.48g | 3.25 ± 0.52h |

| YeO3-c-OCR/pRV16NPwbcL1 | 4.32 ± 0.49e | 2.76 ± 0.44f |

| YeO3-c-OC/pRV16NPwbcL1 | 3.85 ± 0.41g | 2.81 ± 0.56h |

| YeO3-c-OCR/pRV16NPwbcM1 | 4.57 ± 0.38e | 3.48 ± 0.55f |

| YeO3-c-OC/pRV16NPwbcM1 | 3.82 ± 0.11g | 2.58 ± 0.32h |

| YeO3-c-OCR/pRV16NPwbcQ1 | 3.82 ± 0.11e | 2.98 ± 0.36f |

| YeO3-c-OC/pRV16NPwbcQ1 | 3.53 ± 0.51g | 2.51 ± 0.30h |

a Comparisons were made at 21 °C.

b Comparisons were made at 37 °C.

c Data indicate a significant difference from YeO3.

d Data indicate a significant difference from YeO3.

e Data indicate a significant difference from YeO3-c-OCR/pRV16NP.

f Data indicate a significant difference from YeO3-c-OCR/pRV16NP.

g Data indicate a significant difference from YeO3-c-OC/pRV16NP.

h Data indicate a significant difference from YeO3-c-OC/pRV16NP.

Conclusions

In this study, we have characterized linkage specificities of five different UDP-sugar GTases and the priming transferase involved in Ye O:3 OC biosynthesis. We have also demonstrated that the minimum structural requirements for the interactions of OC with bacteriophage ϕR1-37, enterocoliticin, and OC-specific monoclonal antibody 2B5 are distinct.

We analyzed the WbcK and WbcL sequences and constructed a three-dimensional model of WbcK. Based on the analysis, both of them consist of an N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain with the GT-A fold and a much more diverged C-terminal domain involved in the acceptor binding. The key residues involved in the UDP-Glcp binding proved to be highly conserved, and the comparison with the known structures together with multiple sequence alignment allowed us to postulate the catalytic base residues for both WbcK and WbcL; the predictions were experimentally confirmed using different substitutions of the residues. We thus conclude that Asp-182 of WbcK and Glu-181 of WbcL are necessary for their GTase activities and are likely to coordinate the glucose residue in UDP-glucose correctly into the catalytic site of the enzyme. Because the sequence identity of these enzymes to any structurally known GTase is low, it will be interesting to solve three-dimensional structures of both WbcK and WbcL in the future.

Ye O:3 OC has been reported to be a virulence factor, and the different truncated OC mutants constructed in this work would have been an invaluable tool to determine the minimal OC requirements for virulence. Unfortunately, all the constructed OC truncation mutants expressed heterologous populations of both LPS without OC and with truncated OC hence preventing running virulence experiments. At present, we can only speculate on the molecular explanation. One could postulate, for example, that the enzyme responsible for the linkage of the OC to the inner core requires a full-length OC for an efficient reaction. Future studies will aim to test this hypothesis.

The enormous nucleic acid and protein sequence data available allows predictions of subfamilies and functions for different enzymes by bioinformatic methods. Especially in the case of GTases that are responsible for very diverse and linkage-specific reactions, experimental evidence is needed to conclusively specify their functional specificities. The different transferase specificities characterized in this study will provide a valuable supplement to the exiguous linkage-specific data of different GTases. Together with the characterized priming transferase, they also assign a bundle of information of the coordinated synthesis of the Ye O:3 OC hexasaccharide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jukka Karhu, Juha Vahokoski, and Brigitte Kunz for excellent technical assistance; Anita Liljegren for technical help with fermentations; Hermann Moll for help with GC-MS analyses; Dr. Eckhard Strauch for providing the enterocoliticin; and Dr. Vuokko Loimaranta for helpful discussions. We thank Professor Mark Johnson for the excellent facilities provided at the Structural Bioinformatics Laboratory at the Department of Biochemistry and Pharmacy, Åbo Akademi University, and Marcin Skorupski for assistance with the sequence analysis.

This work was supported by Tor, Joe, and Pentti Borgs Memorial Fund and Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (to T. A. S.), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria Grant PI03/0881, Consejo Superior Investigaciones Científicas Proyecto Intramural 200820I174 (to J. A. B.), Academy of Finland Projects 114075, 104361, and 50441 (to M. S.), and Glycoscience Graduate School funds (to E. P.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Tables S1–S3.

- OPS

- O-specific polysaccharide

- ESI FT-ICR MS

- electrospray ionization Fourier-transformed ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry

- GTase

- glycosyltransferase

- OC

- outer core

- Sugp

- 2-acetamido-2,6-dideoxy-d-xylo-hex-4-ulopyranose

- Und-P

- undecaprenyl phosphate

- Ye

- Y. enterocolitica

- DOC

- deoxycholate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holst O., Müller-Loennies S. (2007) in Comprehensive Glycoscience: From Chemistry to Systems Biology (Kamerling J. P., Boons G.-J., Lee Y. C., Suzuki A., Taniguchi N., Voragen A. G. J. eds) Vol. 1, pp. 123–175, Elsevier, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biedzka-Sarek M., Venho R., Skurnik M. (2005) Infect. Immun. 73, 2232–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.al-Hendy A., Toivanen P., Skurnik M. (1992) Infect. Immun. 60, 870–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skurnik M., Venho R., Bengoechea J. A., Moriyón I. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 31, 1443–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinta E., Duda K. A., Hanuszkiewicz A., Kaczyński Z., Lindner B., Miller W. L., Hyytiäinen H., Vogel C., Borowski S., Kasperkiewicz K., Lam J. S., Radziejewska-Lebrecht J., Skurnik M., Holst O. (2009) Chemistry 15, 9747–9754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radziejewska-Lebrecht J., Skurnik M., Shashkov A. S., Brade L., Rózalski A., Bartodziejska B., Mayer H. (1998) Acta Biochim. Pol. 45, 1011–1019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skurnik M., Venho R., Toivanen P., al-Hendy A. (1995) Mol. Microbiol. 17, 575–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiljunen S., Hakala K., Pinta E., Huttunen S., Pluta P., Gador A., Lönnberg H., Skurnik M. (2005) Microbiology 151, 4093–4102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skurnik M. (1999) in Genetics of Bacterial Polysaccharides. (Goldberg J. ed) pp. 23–47, CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skurnik M. (2003) in Genus Yersinia: Entering the Functional Genomic Era (Skurnik M., Bengoechea J. A., Granfors K. eds) pp. 187–197, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skurnik M., Bengoechea J. A. (2003) Carbohydr. Res. 338, 2521–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skurnik M. (2004) in Yersinia: Molecular and Cellular Biology (Carniel E., Hinnebusch B. J. eds) pp. 215–241, Horizon Scientific Press, Wymondham, UK [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bengoechea J. A., Pinta E., Salminen T., Oertelt C., Holst O., Radziejewska-Lebrecht J., Piotrowska-Seget Z., Venho R., Skurnik M. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 4277–4287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell J. A., Davies G. J., Bulone V., Henrissat B. (1997) Biochem. J. 326, 929–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coutinho P. M., Deleury E., Davies G. J., Henrissat B. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 328, 307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breton C., Snajdrová L., Jeanneau C., Koca J., Imberty A. (2006) Glycobiology 16, 29R–37R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pajunen M., Kiljunen S., Skurnik M. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 5114–5120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strauch E., Kaspar H., Schaudinn C., Damasko C., Konietzny A., Dersch P., Skurnik M., Appel B. (2003) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 529, 249–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauch E., Kaspar H., Schaudinn C., Dersch P., Madela K., Gewinner C., Hertwig S., Wecke J., Appel B. (2001) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 5634–5642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pekkola-Heino K., Viljanen M. K., Ståhlberg T. H., Granfors K., Toivanen A. (1987) Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. C 95, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirisena D. M., Skurnik M. (2003) J. Appl. Microbiol. 94, 686–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L., Toivanen P., Skurnik M. (1995) Contrib. Microbiol. Immunol. 13, 310–313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L., Skurnik M. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 1756–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jann K., Jann B., Orskov F., Orskov I., Westphal O. (1965) Biochem. Z. 342, 1–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller-Loennies S., Holst O., Brade H. (1994) Eur. J. Biochem. 224, 751–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oertelt C., Lindner B., Skurnik M., Holst O. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 554–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciucanu I., Kerek F. (1984) Carbohydr. Res. 131, 209–217 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bengoechea J. A., Najdenski H., Skurnik M. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 52, 451–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehrer R. I., Rosenman M., Harwig S. S., Jackson R., Eisenhauer P. (1991) J. Immunol. Methods 137, 167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charnock S. J., Davies G. J. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 6380–6385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehtonen J. V., Still D. J., Rantanen V. V., Ekholm J., Björklund D., Iftikhar Z., Huhtala M., Repo S., Jussila A., Jaakkola J., Pentikäinen O., Nyrönen T., Salminen T., Gyllenberg M., Johnson M. S. (2004) J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 18, 401–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson M. S., Overington J. P. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 233, 716–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson M. S., May A. C., Rodionov M. A., Overington J. P. (1996) Methods Enzymol. 266, 575–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sali A., Blundell T. L. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Lano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gouet P., Courcelle E., Stuart D. I., Métoz F. (1999) Bioinformatics 15, 305–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson M. S., Eveland S. S., Price N. P. (2000) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 191, 169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards K. J., Allen S., Gibson B. W., Campagnari A. A. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 2939–2947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Regué M., Izquierdo L., Fresno S., Piqué N., Corsaro M. M., Naldi T., De Castro C., Waidelich D., Merino S., Tomás J. M. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 4198–4206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pedersen L. C., Tsuchida K., Kitagawa H., Sugahara K., Darden T. A., Negishi M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34580–34585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J., Ritchey M., Yoshida Y., Bush C. A., Cisar J. O. (2009) J. Bacteriol. 191, 1891–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bélanger M., Burrows L. L., Lam J. S. (1999) Microbiology 145, 3505–3521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Price N. P., Momany F. A. (2005) Glycobiology 15, 29R–42R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu B., Perepelov A. V., Li D., Senchenkova S. N., Han Y., Shashkov A. S., Feng L., Knirel Y. A., Wang L. (2010) Microbiology 156, 1642–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali T., Weintraub A., Widmalm G. (2007) Carbohydr. Res. 342, 274–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skurnik M., Biedzka-Sarek M., Lübeck P. S., Blom T., Bengoechea J. A., Pérez-Gutiérrez C., Ahrens P., Hoorfar J. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189, 7244–7253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rebeil R., Ernst R. K., Gowen B. B., Miller S. I., Hinnebusch B. J. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 52, 1363–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bengoechea J. A., Díaz R., Moriyón I. (1996) Infect. Immun. 64, 4891–4899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anisimov A. P., Dentovskaya S. V., Titareva G. M., Bakhteeva I. V., Shaikhutdinova R. Z., Balakhonov S. V., Lindner B., Kocharova N. A., Senchenkova S. N., Holst O., Pier G. B., Knirel Y. A. (2005) Infect. Immun. 73, 7324–7331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skurnik M. (1984) J. Appl. Bacteriol. 56, 355–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Appleyard R. K. (1954) Genetics 39, 440–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yanisch-Perron C., Vieira J., Messing J. (1985) Gene. 33, 103–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ditta G., Stanfield S., Corbin D., Helinski D. R. (1980) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77, 7347–7351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michiels T., Cornelis G. R. (1991) J. Bacteriol. 173, 1677–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.