SUMMARY

Many Rickettsia species are intracellular bacterial pathogens that use actin-based motility for spread during infection. However, while other bacteria assemble actin tails consisting of branched networks, Rickettsia assemble long parallel actin bundles, suggesting the use of a distinct mechanism for exploiting actin. To identify the underlying mechanisms and host factors involved in Rickettsia parkeri actin-based motility, we performed an RNAi screen targeting 115 actin cytoskeletal genes in Drosophila cells. The screen delineated a set of four core proteins—profilin, fimbrin/T-plastin, capping protein, and cofilin—as crucial for determining actin tail length, organizing filament architecture, and enabling motility. In mammalian cells, these proteins were localized throughout R. parkeri tails, consistent with a role in motility. Profilin and fimbrin/T-plastin were critical for the motility of R. parkeri but not Listeria monocytogenes. Our results highlight key distinctions between the evolutionary strategies and molecular mechanisms employed by bacterial pathogens to assemble and organize actin.

INTRODUCTION

Rickettsia are Gram-negative, obligate-intracellular bacteria that are transmitted to mammals by blood-feeding arthropod vectors, and many species cause diseases such as spotted fever and typhus (Walker and Ismail, 2008). During infection in mammals, Rickettsia induce phagocytosis by endothelial cells and then rapidly escape from the phagosome into the cytosol where they replicate. Once in the cytosol, most Spotted Fever Group (SFG) Rickettsia species, as well as the Typhus Group (TG) species R. typhi, assemble actin tails at their surface and undergo actin-based motility (Heinzen et al., 1993; Teysseire et al., 1992). Rickettsia are then propelled throughout the cell and into protrusions, mediating cell-to-cell spread and enhancing virulence (Kleba et al.). The ability to hijack the actin cytoskeleton to drive movement is shared between Rickettsia and other bacterial pathogens including Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella flexneri, Mycobacterium marinum and Burkholderia pseudomallei (Gouin et al., 2005).

Interestingly, the filament architecture in SFG Rickettsia actin tails differs substantially from that of other pathogens. Actin filaments in Rickettsia tails are long and organized into parallel bundles, similar to actin in cellular protrusions such as filopodia and microvilli (Gouin et al., 1999; Van Kirk et al., 2000). In contrast, L. monocytogenes tails are composed of a sheath of longer bundled filaments surrounding a core of shorter filaments organized in Y-branched arrays (Brieher et al., 2004; Cameron et al., 2001; Sechi et al., 1997), similar to actin in lamellipodia (Svitkina and Borisy, 1999). These differences in actin organization presumably reflect differences in how actin filaments are assembled and organized at the bacterial surface.

Well-studied pathogens such as L. monocytogenes and S. flexneri assemble and organize actin by recruiting and activating the host Arp2/3 complex, an actin-nucleating factor that polymerizes Y-branched filament networks and is localized to bacterial actin tails (Gouin et al., 2005). Both pathogens activate the Arp2/3 complex by expressing surface proteins that either mimic or recruit host nucleation-promoting factors (NPFs) (Boujemaa-Paterski et al., 2001; Egile et al., 1999; Skoble et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 1998). L. monocytogenes and S. flexneri motility can be reconstituted in vitro in a mix of purified proteins including actin, Arp2/3 complex, capping protein and actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) (Loisel et al., 1999). Thus, a small set of core proteins that control actin dynamics and organization is sufficient to drive motility.

In contrast, for Rickettsia, the molecular mechanism of actin assembly and organization is not well understood. The R. rickettsii sca2 gene was recently reported to be required for motility and virulence, but the mechanism was not investigated (Kleba et al., 2010). In addition, most SFG Rickettsia genomes encode an NPF for the Arp2/3 complex called RickA that can direct Arp2/3 complex-dependent motility of plastic beads in cell extracts, but RickA expression is not directly correlated with Rickettsia spp. pathogenicity (Gouin et al., 2004; Jeng et al., 2004; Ogata et al., 2001). There is also conflicting evidence as to whether the Arp2/3 complex is (Gouin et al., 2004) or is not (Gouin et al., 1999; Van Kirk et al., 2000) associated with motile Rickettsia, and whether the complex is (Gouin et al., 2004) or is not (Balraj et al., 2008; Harlander et al., 2003; Heinzen, 2003) functionally important for bacterial motility. Numerous other actin-binding proteins have been localized to Rickettsia tails including profilin, VASP, α-actinin and filamin (Gouin et al., 1999; Van Kirk et al., 2000). However, their function in Rickettsia motility has not yet been investigated and the actin cytoskeletal proteins required for Rickettsia motility have yet to be defined.

Based on the unique filament architecture in Rickettsia actin tails, we hypothesized that a distinct set of host cytoskeletal proteins is critical for Rickettsia motility compared to other pathogens. To identify the host factors that are required for Rickettsia motility, we employed RNA interference (RNAi) to examine the function of over 100 actin cytoskeletal proteins in Drosophila melanogaster cells. We identified numerous proteins that play roles in Rickettsia infection and actin-based motility. In particular, profilin, fimbrin/T-plastin, capping protein and ADF/cofilin were essential for actin tail morphology and motility. In mammalian cells, profilin and fimbrin/T-plastin were specifically important for motility of R. parkeri but not for L. monocytogenes. Thus, our results identify a distinct set of core host proteins that play a role in Rickettsia actin-based motility.

RESULTS

RNAi screening identifies proteins important for R. parkeri infection and actin tail formation

Because of the amenability of Drosophila S2R+ cells to RNAi-mediated gene silencing and the natural ability of Rickettsia to infect arthropod cells, we used these cells for RNAi screening to identify host proteins that play a role in Rickettsia actin-based motility. We found that R. parkeri, a member of the SFG that causes mild human disease (Paddock et al., 2008), readily invaded and replicated in S2R+ cells. Moreover, R. parkeri motility occurred at similar rates in S2R+ (13.0 ± 0.3 μm/min, n=23) and mammalian COS7 (13.8 ± 0.43 μm/min, n=26) cells, resulting in the formation of actin tails with similar morphology in both cell types (Figure S1A). This suggests that the mechanism of motility is conserved between species.

We conducted an RNAi screen by targeting 115 actin cytoskeletal genes and 2 non-cytoskeletal control genes (Table S1). The list of targets was expanded from a previous screen that assessed the role of cytoskeletal proteins in lamellae formation (Rogers et al., 2003). Cells were treated with dsRNA for 4 d, infected with R. parkeri for 2 d, and then bacteria and actin were visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Figure S1B). Protein depletion was confirmed for a subset of targets by immunoblotting (Figure S1C). Two phenotypes were then quantified: the percentage of bacteria associated with actin tails as a measure of actin-based motility and the number of bacteria per cell as a measure of overall infection efficiency.

Thirty-four targets were identified as having potential functions in actin-based motility and/or infection efficiency (Table 1). RNAi of 20 genes resulted in a significant difference in the percentage of bacteria associated with actin tails, and RNAi of 18 resulted in a significant difference in the number of bacteria per cell, with 5 exhibiting differences for both phenotypes (Table 1, Figure S1D). RNAi of capping protein did not result in a significant difference in either category but resulted in notably short tails so it was included in further analyses. These 34 proteins fell into 6 major classes (Figure S1D) including: (1) Arp2/3 complex subunits, NPFs and NPF-binding proteins; (2) actin-monomer availability proteins; (3) actin-bundling proteins; (4) endocytic adapters and membrane-cytoskeleton linkers; (5) myosin motors; and (6) cytoskeletal signaling proteins.

Table 1. Proteins implicated in Rickettsia actin tail formation and infection by RNAi screening.

| Proteins implicated in tail formation |

Bacteria with tails (%)a |

p-valueb |

|---|---|---|

| untreated control | 25 ± 13 | n/a |

| a-actinin | 9.2 ± 6.7 | 0.047 |

| ARPC3 | 7.3 ± 8.2 | 0.029 |

| ARPC4 | 8.1 ± 5.9 | 0.035 |

| ARPC5 | 3.9 ± 1.5 | 0.0095 |

| CAP | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 0.015 |

| capping proteinc | 16 ± 6.9 | 0.19 |

| cofilin | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 0.010 |

| Dahd | 6.7 ± 4.9 | 0.0095 |

| Drk d | 11 ± 5.1 | 0.042 |

| DROK | 7.6 ± 7.6 | 0.014 |

| fimbrin | 8.3 ± 5.0 | 0.017 |

| Hip1R | 8.6 ± 4.4 | 0.039 |

| Mtl d | 5.8 ± 3.2 | 0.0066 |

| Myosin IA | 11 ± 7.3 | 0.045 |

| Myosin II | 7.3 ± 8.1 | 0.012 |

| Myosin VI d | 8.8 ± 7.0 | 0.021 |

| profilin | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Rac1 | 8.9 ± 7.9 | 0.022 |

| Rac2 | 6.5 ± 4.6 | 0.021 |

| SCAR d | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 0.0018 |

| Slingshot | 7.3 ± 11 | 0.030 |

| Proteins implicated in infection |

Bacteria/cella | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|

| untreated control | 6.9 ± 4.0 | n/a |

| Anillin | 18 ± 7.5 | <0.0001 |

| Arp2 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 0.026 |

| Arp3 | 13 ± 9.9 | 0.021 |

| Band 4.1 FERM-like | 12 ± 5.4 | 0.030 |

| Dah d | 3.1 ± 0.95 | 0.044 |

| Drk d | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 0.033 |

| MIM-like | 20 ± 7.8 | <0.0001 |

| Mtl d | 2.9 ± 2.1 | 0.038 |

| Myosin V | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 0.039 |

| Myosin VI d | 2.9 ± 0.69 | 0.035 |

| Pp2A | 18 ± 22 | 0.011 |

| Rab5 | 14 ± 10 | 0.0071 |

| RacGAP50C | 26 ± 31 | 0.0011 |

| SCAR d | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 0.0086 |

| Twinfillin | 14 ± 12 | 0.012 |

| Villin-like | 17 ± 15 | 0.0026 |

| Vinculin | 13 ± 13 | 0.035 |

| WASP | 2.7 ± 1.6 | 0.046 |

The data presented are the mean ± standard deviation.

Determined by pairwise comparison with the untreated control using the Student’s t-test.

p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. n/a means not applicable.

No statistically significant difference in the percentage of bacteria with tails was observed, but tails were uniformly shorter.

Targets for which both the percentage of bacteria with tails and the number of bacteria per cell were statistically different from the control as defined in b.

Of the 18 genes implicated in infection, RNAi targeting of 8 resulted in a decrease in bacteria per cell, including those encoding the Arp2/3 complex subunit Arp2, the NPFs SCAR and WASP, the SH2/SH3 adapter protein Drk, the GTPase Mtl, the motors myosin V and myosin VI, and the actin-associated protein Dah. These proteins might enhance R. parkeri infection by promoting internalization, motility or spread. RNAi of 10 others resulted in an increase in bacteria per cell, which was caused by an increase in cell size in some cases (allowing more bacteria to accumulate in a single cell), or could also reflect more efficient bacterial internalization, replication, motility and/or spread.

The screen also identified 20 genes implicated in actin-based motility. These included genes encoding Arp2/3 complex subunits (ARPC3, ARPC4, and ARPC5), the G-actin-binding proteins profilin and cyclase-associated protein (CAP), the severing/depolymerizing protein cofilin, the cofilin phosphatase slingshot, the actin bundling proteins fimbrin and α-actinin, the GTPases Rac1 and Rac2, the kinase ROCK, the motors myosin IA and II, and the endocytic protein Hip1R. Five of the 20 genes — encoding SCAR, Dah, Drk, Mtl and myosin VI — were also implicated in infection, suggesting that defects in tail formation and infection can result from inhibition of common pathways. Thus, the RNAi screen identified numerous candidate proteins that might perform important functions in actin-based motility.

RNAi of numerous targets causes defects in actin tail length and morphology

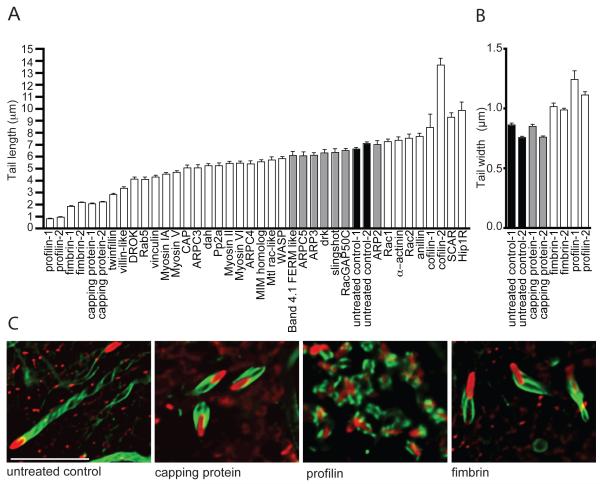

To identify those target genes that function specifically in actin-based motility, we sought a phenotypic parameter more directly linked to this process. Previous work with L. monocytogenes showed that the length of actin tails associated with moving bacteria directly correlates with the rate of movement (Theriot et al., 1992). We therefore targeted the 34 genes identified in the original screen using RNAi and measured the effect on actin tail length. RNAi of 20 genes resulted in significantly shorter actin tails than those in untreated control cells, with the most dramatic reductions (>66%) observed after targeting profilin, fimbrin and capping protein (Figure 1A). Moreover, RNAi of 7 genes resulted in significantly longer tails, with the largest increases (30-50%) observed after targeting SCAR, Hip1R and cofilin (Figure 1A). RNAi of Arp2/3 complex subunits did not have a dramatic impact on tail length, suggesting that the complex might not play a direct role in Rickettsia motility. Importantly, 4 of the 6 RNAi targets that produced the most pronounced phenotypes — profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin— are known to play key roles in controlling actin dynamics and organization, suggesting these might constitute a core set of proteins that are crucial for Rickettsia motility.

Figure 1. RNAi identified numerous targets that affect actin tail length and morphology.

(A, B) Graphs of actin tail lengths (A) and widths (B) following RNAi of the indicated targets. Data are mean ± SEM. Black bar indicates the untreated control, grey bars indicate no difference from the control based on a pairwise Student’s t-test (p>0.05), and white bars indicate a statistically significant difference from the control (p<0.05). In cases where 2 distinct dsRNAs were used, targets are designated with −1 and −2. (C) Z-sections from deconvolved images of untreated cells, or cells treated with dsRNAs targeting profilin, fimbrin and capping protein. R. parkeri (red) was visualized by immunofluorescence, and actin tails (green) were visualized with Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin. Scale bar, 10 μm.

RNAi of the above-mentioned targets often affected aspects of tail morphology other than length (Figure 1C). For example, RNAi of the actin bundling protein fimbrin resulted in short tails that were significantly wider than in control cells, and had loose and splayed filament strands (Figure 1B, 1C). This suggests that fimbrin plays an important role in organizing actin filaments in Rickettsia tails. In addition, RNAi of the actin monomer-binding protein profilin resulted in very short tails, short actin spikes on the bacterial surface, or a failure to recruit actin (Figure 1C). When present, actin tails were also significantly wider than those in the untreated control cells (Figure 1B). This dramatic phenotype suggests that profilin plays an essential role in actin assembly and organization by Rickettsia. Importantly, targeting profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin with a second set of dsRNAs produced nearly identical results, suggesting that the observed phenotypes were not due to off-target effects (Figure 1A, 1B).

Profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin play direct roles in actin-based motility

The defects in actin tail length and morphology observed upon RNAi targeting of profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin suggested that these factors play a direct role in motility. To test this, we measured the rates of actin tail growth in live R. parkeri-infected S2R+ cells expressing Lifeact-GFP, an F-actin-binding probe (Riedl et al., 2008). RNAi targeting of fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin caused a moderate and statistically significant reduction in motility rates compared to controls (Figure 2A). Moreover, RNAi of profilin caused a dramatic reduction in motility rates (Figure 2A). Thus, all 4 proteins are important for actin-based motility, and profilin plays a particularly critical role in this process.

Figure 2. RNAi of profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin resulted in reduced motility rates.

(A) Graph of R. parkeri motility rates (mean ± SD) in untreated cells, and cells treated with dsRNAs targeting profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin. Rates for all dsRNA-treated cells are different from the untreated control (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s Multiple Comparison tests; p<0.05), and rates for profilin RNAi are different from all other RNAi targets (p<0.01). (B) Scatter plot showing the mean tail length and the corresponding mean motility rate for individual bacteria in untreated control cells (black) or cells treated with dsRNAs targeting profilin (red), fimbrin (blue), capping protein (yellow) and cofilin (green). The grey line is the best linear fit for the combined data set. See also Movies S1, S2 and S3.

To further examine the role of these proteins in actin-based motility, we explored the relationship between the motility rate and tail length. It was previously reported that L. monocytogenes motility rates (3-21 μm/min) and tail lengths (1-16 μm) varied widely, and a linear correlation (R2 >0.96) between the two parameters could be observed (Theriot et al., 1992). We therefore measured both the motility rate and mean tail length for each moving bacterium over a 1-3 min interval in control and RNAi-treated cells. In untreated controls, there was a compact distribution of motility rates (10.5 to 15.5 μm/min) and tail lengths (9-22 μm), and no linear correlation between the 2 parameters was observed (R2 =0.02) (Figure 2B). However, when values for control and RNAi targeted cells were taken together, there was a stronger linear correlation (R2 =0.30). Interestingly, the values for fimbrin and cofilin appeared to be outliers because omitting these from the analysis resulted in an even stronger linear correlation (R2 =0.80), suggesting that silencing these proteins caused a deviation in the relationship between tail length and motility rate. In particular, fimbrin RNAi caused a 23% decrease in motility rate but a 62% decrease in tail length (Figure 2B). This suggests that fimbrin maintains the structure of the tail but does not dramatically influence the rate of actin assembly. Moreover, cofilin RNAi caused a 33% reduction in motility rate but had no significant impact on mean tail length, although the distribution of lengths was broadened and longer tails were observed (Figure 2B). This suggests that actin disassembly by cofilin might replenish the monomer pool to fuel actin assembly and bacterial movement.

Next, we examined the morphology of actin tails in live S2R+ cells expressing Lifeact-GFP to label actin (Movies S1-S3). Compared with controls (Movie S1), actin tails in capping protein (Movie S1) and cofilin RNAi cells (Movie S2) were morphologically normal, but were shorter after RNAi of capping protein. In contrast, tails in fimbrin RNAi cells were short and disorganized, with loose filament strands splaying out from the bacterial surface (Movie S2). In profilin RNAi cells bacteria were either associated with actin clouds and failed to move, or formed very short actin tails (Movie S3). These results confirm that profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin comprise a core set of proteins that are important for R. parkeri actin tail assembly and motility, and that each likely plays a distinct role in this process.

Profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin are localized to R. parkeri actin tails in mammalian cells

We hypothesized that the core proteins critical for Rickettsia motility in insect cells were also likely to perform an important role in mammalian cells. To begin to test this, we observed whether each protein was localized to Rickettsia actin tails. Mammalian COS7 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing GFP-tagged profilin II (profilin-GFP), T-plastin (plastin-GFP; the mammalian equivalent of fimbrin), capping protein β subunit (GFP-capping protein) and cofilin (GFP-cofilin). For controls, we used plasmids expressing GFP or GFP-Arp3 (Arp3 was reported to localize to L. monocytogenes, but not to R. conorii or R. rickettsii actin tails) (Gouin et al., 1999; Harlander et al., 2003). Cells were subsequently infected with R. parkeri or L. monocytogenes, and the localization of proteins was visualized by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy.

Profilin, T-plastin, capping protein and cofilin all localized to tails formed by both pathogens (Figure 3; Movies S4-S7). Plastin-GFP exhibited the most prominent localization to R. parkeri and L. monocytogenes tails (Movie S4). Profilin-GFP (Movie S5), GFP-capping protein (Movie S6) and GFP-cofilin (Movie S7) were visible in R. parkeri tails, but the intensity of fluorescence was less than in L. monocytogenes tails, perhaps due to a lower overall density of actin filaments in R. parkeri tails. GFP-Arp3 localized only to L. monocytogenes tails, and GFP did not localize to any tails (Movie S8). The localization of profilin, T-plastin (fimbrin), capping protein and cofilin to actin tails is consistent with the hypothesis that they play a direct role in actin polymerization and organization during actin based motility.

Figure 3. Localization of GFP-tagged cytoskeletal proteins to R. parkeri and L. monocytogenes tails.

Images taken from movies of COS7 cells expressing the indicated GFP-tagged proteins or GFP alone. Cells were either infected with R. parkeri or L. monocytogenes. Arrowheads indicate motile bacteria. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Movies S4, S5, S6, S7 and S8.

Fimbrin/T-plastin is important for R. parkeri actin tail formation and actin-based motility in mammalian cells

The importance of fimbrin for Rickettsia actin tail organization and motility in Drosophila cells, coupled with the localization of fimbrin/T-plastin to actin tails, suggested that this protein might play an important role in R. parkeri motility in mammalian cells. To evaluate the function of fimbrin/T-plastin, COS7 cells were transfected with 2 siRNAs targeting T-plastin, or with control non-specific or GAPDH siRNAs, and silencing was confirmed by immunoblotting (Figure S2). Cells were then infected with R. parkeri or L. monocytogenes, and the percentage of bacteria associated with actin tails was quantified. Strikingly, fimbrin/T-plastin knockdown caused a 50% reduction in the percentage of R. parkeri associated with tails (Figures 4A, 4G) but had no effect on L. monocytogenes (Figure 4D). Thus, fimbrin/T-plastin plays an important role in the initiation and/or maintenance of R. parkeri, but not L. monocytogenes, actin-based motility.

Figure 4. RNAi of T-plastin in mammalian cells reduces the frequency and rate of motility.

COS7 cells were treated with siRNA targeting T-plastin (PLS3-1, -2), or control GAPDH (GAPD) or non-specific (NS) siRNAs, and infected with either R. parkeri (A-C, G) or L. monocytogenes (D-F). (A, D) Graphs of the percentage of bacteria (mean ± SD) associated with actin tails after transfection with the indicated siRNA. Triple asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference after pairwise comparison to the nonspecific siRNA control (p<0.001, Student’s t-test). (B, E) Scatter plots of tail length after transfection with the indicated siRNA (red bar indicates mean). (C, F) Scatter plots of the mean tail length and the corresponding mean motility rate for individual bacteria in cells transfected with control non-specific (black) or T-plastin siRNA (blue). (G) R. parkeri (red) visualized by immunofluorescence and actin (green) visualized with Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin in cells transfected with non-specific (NS) or T-plastin (PLS3-1) siRNAs. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Movies S9 and S10.

We next tested whether silencing of fimbrin/T-plastin affected the length of bacterial actin tails or the rate of motility. COS7 cells were co-transfected with fimbrin/T-plastin or non-specific siRNAs, together with a plasmid expressing Lifeact-GFP, and then infected with R. parkeri or L. monocytogenes. Actin tail length and motility rate were measured over a 1-3 min interval by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. Both Rickettsia and Listeria actin tail lengths were indistinguishable in cells silenced for fimbrin/T-plastin expression versus their respective control cells (Figures 4B, 4E, 4G). However, the mean rate of R. parkeri motility was significantly reduced from 14 μm/min in control cells to 10 μm/min in cells silenced for fimbrin-T-plastin (Figure 4C; Movies S9, S10; p<0.0001 by Student’s t-test). There was no significant difference in the rate of L. monocytogenes motility in fimbrin/T-plastin RNAi versus control cells (Figure 4F). These results confirm that fimbrin/T-plastin plays an important and specific role in R. parkeri, but not L. monocytogenes, actin-based motility in mammalian cells.

Profilin is crucial for rapid Rickettsia actin-based motility in mammalian cells

The observations that profilin is required for rapid R. parkeri motility in Drosophila cells and is localized to actin tails suggests that it might also play an important role in Rickettsia motility in mammalian cells. To examine the functional importance of profilin, COS7 cells were transfected with 2 siRNAs targeting profilin 1 (the ubiquitously-expressed isoform) (Jockusch et al., 2007), or with non-specific or GAPDH siRNAs as controls, and silencing was confirmed by immunoblotting (Figure S2). Cells were then infected with R. parkeri or L. monocytogenes and the percentage of bacteria associated with actin, tail lengths and motility rates were measured as described above for fimbrin/T-plastin.

RNAi silencing of profilin 1 in COS7 cells had no impact on the percentage of R. parkeri associated with actin tails compared with controls (Figure 5A) but had a dramatic impact on R. parkeri tail morphology and motility. Compared to controls, Rickettsia tails were 66% shorter in profilin 1 RNAi cells (Figure 5B, 5C, 5G; Movies S9, S11) and there was a 60% reduction in motility rate (Figure 5C; mean 5.4 μm/min in profilin 1 RNAi; 13.8 μm/min in control cells; p<0.0001 by Student’s t-test). Interestingly, Rickettsia in profilin 1 knockdown cells were often observed in microcolonies and were associated with actin in a rosette-like pattern (Figure 5G), suggesting that bacterial replication occurred without significant movement. Despite the reported importance of profilin for L. monocytogenes motility (Grenklo et al., 2003; Loisel et al., 1999; Theriot et al., 1994), no significant difference was observed in the percentage of bacteria associated with actin, the length of tails or the rate of motility in profilin 1 RNAi cells versus controls (Figures 5D, 5E, 5F). Together these observations indicate that profilin is specifically required for rapid and efficient Rickettsia actin-based motility, and that Rickettsia motility is exquisitely sensitive to the levels of profilin compared to Listeria.

Figure 5. RNAi of profilin 1 in mammalian cells reduces the length of R. parkeri actin tails and the motility rate.

COS7 cells were treated with siRNA targeting profilin 1 (PFN1-1, -2), or control GAPDH (GAPD) or non-specific (NS) siRNAs, and infected with either R. parkeri (A-C, G) or L. monocytogenes (D-F). (A, D) Graphs of the percentage of bacteria associated with actin tails (mean ± SD) after transfection with the indicated siRNA. (B, E) Scatter plots of the length of actin tails after transfection with the indicated siRNA (red bar indicates mean). Triple asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference after pairwise comparison to the nonspecific siRNA control (p<0.001); Student’s t-test). (C, F) Scatter plots showing the mean tail length and the corresponding mean motility rate for individual bacteria in cells transfected with control non-specific siRNA (black) or with profilin 1 siRNA (red). (G) R. parkeri (red) visualized by immunofluorescence and actin (green) visualized with Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin in cells transfected with non-specific (NS) or profilin 1 (PFN1-1) siRNAs. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Movies S9 and S11.

DISCUSSION

The unique actin filament architecture in Rickettsia actin tails suggests that they use a distinct set of host cytoskeletal proteins to assemble and organize actin filaments. Using RNAi screening we identified numerous cytoskeletal proteins that play a role in Rickettsia motility, including a set of 4 core proteins — profilin, fimbrin/T-plastin, capping protein and cofilin — that are important for this process. Two of these proteins, profilin and fimbrin/T-plastin, are specifically required for the actin-based motility of R. parkeri, but not L. monocytogenes. These results provide a comprehensive analysis of the molecular requirements for Rickettsia motility and highlight key distinctions in the mechanism of actin assembly and organization between different bacterial pathogens.

Comparison of the core proteins required for R. parkeri, L. monocytogenes and S. flexneri motility revealed interesting similarities and differences. Reconstitution of L. monocytogenes and S. flexneri motility requires 3 factors: the Arp2/3 complex, capping protein and cofilin (Loisel et al., 1999). Our results suggest that the Arp2/3 complex is not required for Rickettsia motility (discussed below). On the other hand, capping protein and cofilin play an important role during Rickettsia motility in various cell types.

The importance of capping protein for maintaining rapid Rickettsia motility and long comet tails is consistent with its role in enhancing L. monocytogenes and bead motility in vitro (Akin and Mullins, 2008; Loisel et al., 1999). Two models have been proposed to explain the importance of capping protein in actin-based motility. In the actin funneling model (Carlier and Pantaloni, 1997), capping protein caps most filament barbed ends in cells, increasing the concentration of free actin monomers that funnel onto uncapped barbed ends to promote rapid elongation. In the monomer gating model (Akin and Mullins, 2008), capping protein acts as a switch between elongation and nucleation by terminating elongation and biasing new monomers to participate in filament nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. Although the monomer gating model is applicable to L. monocytogenes motility, which requires the Arp2/3 complex as a nucleator (Gouin et al., 2005), our evidence fails to support a major role for Arp2/3 complex in Rickettsia motility (discussed below). Thus, during Rickettsia motility capping protein might act as a monomer gate with a different nucleator, or might cap the bulk filament population and enable monomer funneling onto uncapped ends adjacent to the bacterium.

Our observation that cofilin is important for shortening Rickettsia actin tails and maintaining rapid motility are similar to previous reports that depletion of cofilin from cell extracts increases L. monocytogenes tail length (Rosenblatt et al., 1997) and that addition of cofilin accelerates L. monocytogenes motility (Carlier et al., 1997). Cofilin functions to accelerate actin dynamics (Van Troys et al., 2008) by both severing ADP-bound filaments at low cofilin:actin ratios and nucleating new filaments at high cofilin:actin ratios (Andrianantoandro and Pollard, 2006). Given the low levels of GFP-cofilin observed in Rickettsia tails and the increased tail lengths observed after cofilin depletion, it is likely that the key role of cofilin during Rickettsia motility is to sever/disassemble actin filaments in actin tails and elsewhere, and to regenerate the actin monomer pool to fuel assembly and bacterial movement.

Our results also indicate that Rickettsia motility involves 2 additional core proteins, fimbrin/T-plastin and profilin, which are not required to reconstitute L. monocytogenes and S. flexneri motility. Fimbrin/T-plastin bundles actin filaments that are oriented with uniform polarity (Delanote et al., 2005) like those in Rickettsia tails (Gouin et al., 2004; Van Kirk et al., 2000). Interestingly, other actin bundling proteins including α-actinin, fascin and filamin reportedly localize to Rickettsia tails (Gouin et al., 2004; Van Kirk et al., 2000), but we did not observe any effect on Rickettsia tail formation and motility after RNAi targeting these proteins. Although silencing fimbrin/T-plastin decreased the frequency and rate of Rickettsia motility and caused disorganized comet tails, it had no effect on L. monocytogenes tail formation or motility. Together these results indicate that fimbrin/T-plastin plays a primary role in bundling actin and establishing the unique architecture of the parallel actin filaments in Rickettsia tails, and in initiating and maintaining motility by forming tight bundles that provide mechanical rigidity for force generation. Additionally, fimbrin/T-plastin might inhibit the filament severing or disassembling activity of cofilin (Giganti et al., 2005), further stabilizing filaments in Rickettsia actin tails.

Interestingly, our results indicate that the actin monomer binding protein profilin plays a profoundly important role in Rickettsia motility, and is crucial for actin tail formation and rapid movement. In contrast, we did not detect a role for profilin in L. monocytogenes actin tail formation or motility. Although this is consistent with a previous report that depleting profilin from cell extract had no impact on L. monocytogenes motility (Marchand et al., 1995), other reports suggest that profilin increases the rate of L. monocytogenes motility in vitro and in cells (Geese et al., 2002; Kang et al., 1997; Loisel et al., 1999; Theriot et al., 1994). Regardless, our results suggest that Rickettsia motility has a much more stringent dependence on profilin, highlighting a key difference in the mechanisms of actin assembly between these pathogens. Profilin possesses several biochemical activities that are relevant to bacterial actin assembly, including the ability to lower the critical concentration for barbed end actin assembly, enhance dynamics at barbed ends, and accelerate the exchange of ADP for ATP on actin (Yarmola and Bubb, 2006). We propose that, unlike for L. monocytogenes, actin nucleation and/or elongation at the Rickettsia surface requires one or more of these activities of profilin.

Surprisingly, our RNAi screen did not identify a cellular actin nucleator that is required for R. parkeri motility. Although SFG Rickettsia express an activator of the Arp2/3 complex called RickA, RNAi targeting of Arp2/3 complex subunits in Drosophila cells had no dramatic effect on actin tail length. This is consistent with a report that overexpressing the Arp2/3-binding WCA domain of the NPF SCAR had little effect on R. rickettsii motility but inhibited S. flexneri motility (Harlander et al., 2003), although another group reported that SCAR WCA expression inhibited R. conorii motility (Gouin et al., 2004). These results, together with reports that the Arp2/3 complex is absent from Rickettsia tails (Gouin et al., 1999; Van Kirk et al., 2000; this study), suggest that the Arp2/3 complex is not required for Rickettsia motility, in contrast with L. monocytogenes (Loisel et al., 1999). This is also consistent with reports that RickA expression does not always correlate with Rickettsia motility or virulence (Balraj et al., 2008). On the other hand, silencing of Arp2/3 complex subunits as well as the NPFs SCAR and WASP decreased the efficiency of R. parkeri infection, suggesting that the Arp2/3 complex might function in host cell entry or cell-to-cell spread, consistent with previous results (Martinez and Cossart, 2004).

RNAi targeting of other cellular actin nucleation and elongation factors that form unbranched filaments (Campellone and Welch, 2010), including all 6 Drosophila formin family proteins, the WH2-domain nucleator Spire, and Ena/VASP proteins, also had no effect on Rickettsia actin tails. These results suggest that no single host protein nucleates actin filaments during Rickettsia motility, and point to the possible existence of a bacterial actin nucleator. It was recently reported that the R. rickettsii Sca2 protein is required for actin assembly and motility, suggesting that it is an actin nucleation factor (Kleba et al., 2010).

We propose a model for the mechanism of actin assembly and organization during Rickettsia actin-based motility (Figure 6). In this model, R. parkeri tail assembly and motility requires a bacterial actin nucleator that is likely Sca2 (Kleba et al., 2010), as well as 4 core host proteins that include profilin, fimbrin/T-plastin, capping protein and cofilin. Profilin is critical for delivering ATP-bound actin monomers to barbed ends at the bacterial surface, enhancing filament elongation and force generation. Capping protein blocks monomer addition on older barbed ends, funneling monomers onto, or gating nucleation of, newer filaments at the bacterial surface. Fimbrin/T-plastin bundles filaments into long helical arrays generating a structural scaffold that supports force generation and also competes with cofilin to enhance filament stability. Ultimately, cofilin severs older ADP-bound filaments, replenishing the monomer pool and enhancing the rate of actin assembly and motility. In addition, our screen identified a number of other proteins, including those that participate in actin dynamics and organization, endocytosis, membrane linkage and signaling, that might play an accessory role in actin-based motility and infection or might participate indirectly via an effect on bacterial entry or spread. Based on the success of our targeted screen, genome wide RNAi screening will likely identify additional host proteins involved in Rickettsia infection, replication, motility and spread.

Figure 6. Model of the molecular mechanism of actin-based Rickettsia motility.

Actin filament assembly at the bacterial surface is induced by a nucleator that is likely of bacterial origin (red drop). Actin monomers (green circles) associated with profilin (blue circles) assemble onto filament barbed ends at the bacterial surface, generating motile force. Fimbrin/T-plastin (yellow cross) bundles the growing filaments into long helical strands, while displacing cofilin (orange triangles). Cofilin binds to older ADP-actin filaments and facilitates severing and disassembly at the pointed ends, replenishing the monomer pool. Capping protein (purple arches) blocks addition of ATP-actin monomers to the barbed ends of older filaments, enhancing the flux of profilin-bound actin monomers onto newer barbed ends.

Our work demonstrates that the molecular requirements for actin assembly and organization into the distinct filament bundles observed in Rickettsia tails include proteins that play a widespread role in the actin-based motility of bacterial pathogens, as well as proteins that play a uniquely important role for Rickettsia. Because the organization of actin in Rickettsia tails is similar to that in cell surface protrusions such as filopodia and microvilli, Rickettsia motility might serve as a model for understanding the mechanisms of actin function in these cellular structures. Future work will reveal additional details of the molecular mechanism of Rickettsia motility and spread, and might uncover new paradigms for the cellular regulation of actin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: mouse anti-Dm-profilin (developed by L. Cooley at Yale School of Medicine, maintained by the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) at University of Iowa); rabbit anti-Dm-anillin (C. Field, Harvard Medical School) (Field and Alberts, 1995); rabbit anti-Dm-cofilin serum (M. L. Goldberg, Cornell University); rat anti-Dm-Arp3 (L. Cooley) (Hudson and Cooley, 2002); guinea pig anti-Dm-SCAR (J. Zallen, Sloan-Kettering Institute) (Zallen et al., 2002); mouse anti-Dm-alpha-tubulin (GE Healthcare); rabbit anti-Hs-profilin-1 (Cell Signaling Technology); mouse anti-GAPDH (Ambion); rabbit anti-Hs-T-plastin C-15 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti-tubulin (developed by M. Klymkowsky at the University of Colorado, Boulder, maintained by the DSHB); mouse anti-Rickettsia M14-13 and rabbit anti-Rickettsia antibody R4668 (T. Hackstadt, NIH/NIAID) (Anacker et al., 1987; Policastro et al., 1997); rabbit anti-Listeria O antibody (BD Difco); horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies for immunoblotting (GE Healthcare); Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence (Invitrogen). Abbreviations: Drosophila melanogaster, Dm; Homo sapiens, Hs.

Plasmids and baculovirus strains

Plasmids were obtained from the following sources: pEGFP-N1-profilin II (A. Sechi, Universitätsklinikum Aachen) (Geese et al., 2000); pCDNA3.1-smRS-GFP-Plastin (T. Timmers, INRA/CNRS) (Timmers et al., 2002); pEGFP-C1-capping protein ß2 subunit (Addgene) (Schafer et al., 1998); pEGFP-C2-cofilin (H.G. Mannherz, Ruhr University) (Mannherz et al., 2005); pEGFP-N1-ACTR3 (Welch et al., 1997).

To generate a plasmid that expresses Lifeact-GFP in mammalian cells, complementary DNA oligomers encoding Lifeact (Riedl et al., 2008) were annealed and subcloned into pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) to generate an in-frame Lifeact-GFP fusion gene. To generate a Lifeact-GFP expressing baculovirus for insect cell transduction, the Lifeact-GFP locus was first subcloned into a plasmid containing the baculovirus ie-1 promoter, and then subcloned into a plasmid containing flanking regions of homology with the baculovirus genome, including the essential viral p78/83 gene. Co-transfection of this plasmid with a bacmid containing a p78/83 deletion resulted in the restoration of the p78/83 gene and the production of a baculovirus expressing ie-1 Lifeact-GFP.

Bacterial and cell growth and infection

Bacteria and cells were obtained from the following sources: R. parkeri Portsmouth strain (C. Paddock, CDC) (Paddock et al., 2004); L. monocytogenes 10403S (D. Portnoy, University of California, Berkeley) (Bishop and Hinrichs, 1987); Drosophila S2R+ cells (R. Tjian, U. C. Berkeley); COS7 and Vero cells (U. C. Berkeley, tissue culture facility).

S2R+ cells were grown at 28°C in M3 Shields and Sang media (Sigma), supplemented with 0.5 g/L KHCO3, 1 g/L yeast extract, 2.5 g/L meat peptone extract and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). COS7 and Vero cells were grown in DMEM, supplemented with 2-10% FBS at 37°C with 5% CO2. R. parkeri was propagated in Vero cells at 33°C with 5% CO2, and purified by Renografin density gradient centrifugation (Hackstadt et al., 1992). L. monocytogenes was grown in liquid Brain Heart Infusion media at 37°C.

R. parkeri was infected at an MOI of 0.2-1.0. Cells to be fixed were infected for 48 h, while cells to be viewed live were infected for 24 h. For infection with L. monocytogenes, bacteria were preincubated in DMEM for 1 h at 33°C with 5% CO2, then added at an MOI of 5-10 for 3.5 h at 33°C with 5% CO2, and finally treated with 10 μg/ml gentamicin for 0.5 h prior to fixation to kill extracellular bacteria.

RNA synthesis and RNAi screening in S2R+ cells

Primers for PCR of target genes were derived from those published by Rogers et al. (2003) or from the Drosophila RNAi Screening Center (DRSC, http://flyrnai.org). Primers for the second set of dsRNAs for profilin, fimbrin, capping protein and cofilin were recommended by the DRSC based on algorithms used to minimize potential off-target effects. Each primer contained a T7 RNA polymerase-binding site. Following PCR from Drosophila genomic DNA, the sequences were confirmed. In vitro transcription was performed in 80 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM DTT, 2 mM Spermidine-HCl and 20 mM MgCl2, with 7.5 mM each NTPs and 109 U RNAsin, 0.4 U yeast inorganic pyrophosphatase and 91 U T7 RNA polymerase. The reactions were incubated for 6 h at 37°C. RNA products were LiCl2 purified, confirmed to be of the correct size by agarose gel electrophoresis, and their concentration was determined by spectrophotometry.

For RNAi screening, monolayers of S2R+ cells were treated with dsRNA at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml for 4 d, and then infected with R. parkeri for 2 d. RNAi was performed for each target in triplicate. Cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy, as described below. The number of bacteria per infected cell and the number of tails per bacterium were counted in 50-100 cells in over at least 10 different fields of view. The values for each target were compared pairwise with the untreated control by the Student’s t-test using Prism (Graphpad Software). Differences were considered to be significant if p<0.05.

Transfection of mammalian cells

For expression of GFP-tagged proteins, 0.4-0.6 μg of plasmid DNA was transiently transfected into COS7 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For gene silencing, siRNAs (Ambion) at a final concentration of 50 nM were transfected into COS7 cells using Lipofectamine-RNAi-MAX (Invitrogen) in serum-free DMEM. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were infected with R. parkeri, or at 92 h cells were infected with L. monocytogenes. Cells were fixed at 96 h, and were processed for immunoblotting or immunofluorescence, as described below.

Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence and phenotypic analysis

For immunoblotting, protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, probed with primary and secondary antibodies, and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare). For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min, permeabilized in PBS with 1% Triton X-100, and then incubated with primary antibodies followed by Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies in PBS with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.5% Triton X-100. Actin was stained with 0.04 U/μl of Alexa-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen). Cells were mounted with Prolong Gold anti-fade (Invitrogen).

Images were captured using an Olympus IX71 microscope with a 100X (1.35 NA) PlanApo objective lens and a Photometrics CoolSNAP HQ camera. Images were captured as 16 bit TIFF files using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices), converted to 8-bit files using Adobe Photoshop, and the brightness/contrast levels were adjusted. Actin tail lengths were measured from the bacterial pole to the end of the tail for over 200 examples in at least 30 images using ImageJ software. Tail lengths were compared pairwise to the control by the Student’s t-test using Prism. Differences were considered to be significant if p<0.05. Deconvolution images were taken using an Applied Precision DeltaVision 4 Spectris microscope with a 100X (1.4 NA) PlanApo objective equipped with a Photometrics CH350 CCD camera. Images were captured using SoftWoRx v3.3.6 software (Applied Precision), and were deconvolved with Huygens Professional v3.1.0p0 software (Scientific Volume Imaging).

Live-cell imaging

Cells were plated on glass-bottomed 35 mm dishes (MatTek). Actin was visualized by infecting S2R+ cells with Lifeact-GFP-expressing-Baculovirus at an MOI of 10, treating with the dsRNA of the target of interest, and then infecting with R. parkeri for 48 h. COS7 cells were co-transfected with the Lifeact-GFP plasmid and the relevant siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000, and then infected with R. parkeri for 48 h, or incubated for 44 h and infected with L. monocytogenes for 4 h. To visualize other GFP-tagged proteins, COS7 cells were transfected with the relevant plasmid and then infected with R. parkeri for 24 h, or incubated for 20 h and infected with L. monocytogenes for 4 h. Image acquisition was performed as described above, and movies were assembled using ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop. The rate of movement was measured by manually tracking 15-30 individual moving bacteria for 1-3 min at 10 s intervals using the Manual Tracking plugin in ImageJ. The length of the tail associated with each moving bacterium was measured in each frame using ImageJ, and the mean tail length over the time interval was determined. Correlation coefficients were calculated by linear regression analysis using Prism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Welch lab for technical assistance and comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to R. Tjian, L. Cooley, C. Field, M. L. Goldberg, J. Zallen, M. Klymkowsky, T. Hackstadt, D. Portnoy, A. Sechi, T. Timmers, J. Cooper, H. G. Mannherz, T. Ohkawa, and C. Paddock for providing strains or reagents. A. W. S. was supported by NIH/NIGMS Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award 5F32GM084359 and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 09POSY2160022. M. D. W. was supported by NIH/NIAID grant AI 074760.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akin O, Mullins RD. Capping protein increases the rate of actin-based motility by promoting filament nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. Cell. 2008;133:841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker RL, Mann RE, Gonzales C. Reactivity of monoclonal antibodies to Rickettsia rickettsii with spotted fever and typhus group rickettsiae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1987;25:167–171. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.1.167-171.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrianantoandro E, Pollard TD. Mechanism of actin filament turnover by severing and nucleation at different concentrations of ADF/cofilin. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balraj P, El Karkouri K, Vestris G, Espinosa L, Raoult D, Renesto P. RickA expression is not sufficient to promote actin-based motility of Rickettsia raoultii. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DK, Hinrichs DJ. Adoptive transfer of immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. The influence of in vitro stimulation on lymphocyte subset requirements. J. Immunol. 1987;139:2005–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boujemaa-Paterski R, Gouin E, Hansen G, Samarin S, Le Clainche C, Didry D, Dehoux P, Cossart P, Kocks C, Carlier MF, et al. Listeria protein ActA mimics WASp family proteins: it activates filament barbed end branching by Arp2/3 complex. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11390–11404. doi: 10.1021/bi010486b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brieher WM, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ. Fascin-mediated propulsion of Listeria monocytogenes independent of frequent nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. J. Cell Biol. 2004;165:233–242. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron LA, Svitkina TM, Vignjevic D, Theriot JA, Borisy GG. Dendritic organization of actin comet tails. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campellone KG, Welch MD. A nucleator arms race: cellular control of actin assembly. Nature Reviews. 2010;11 doi: 10.1038/nrm2867. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier MF, Laurent V, Santolini J, Melki R, Didry D, Xia GX, Hong Y, Chua NH, Pantaloni D. Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:1307–1322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier MF, Pantaloni D. Control of actin dynamics in cell motility. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;269:459–467. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delanote V, Vandekerckhove J, Gettemans J. Plastins: versatile modulators of actin organization in (patho)physiological cellular processes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005;26:769–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egile C, Loisel TP, Laurent V, Li R, Pantaloni D, Sansonetti PJ, Carlier MF. Activation of the CDC42 effector N-WASP by the Shigella flexneri IcsA protein promotes actin nucleation by Arp2/3 complex and bacterial actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:1319–1332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.6.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CM, Alberts BM. Anillin, a contractile ring protein that cycles from the nucleus to the cell cortex. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:165–178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geese M, Loureiro JJ, Bear JE, Wehland J, Gertler FB, Sechi AS. Contribution of Ena/VASP proteins to intracellular motility of listeria requires phosphorylation and proline-rich core but not F-actin binding or multimerization. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2383–2396. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geese M, Schluter K, Rothkegel M, Jockusch BM, Wehland J, Sechi AS. Accumulation of profilin II at the surface of Listeria is concomitant with the onset of motility and correlates with bacterial speed. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:1415–1426. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.8.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giganti A, Plastino J, Janji B, Van Troys M, Lentz D, Ampe C, Sykes C, Friederich E. Actin-filament cross-linking protein T-plastin increases Arp2/3-mediated actin-based movement. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1255–1265. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin E, Egile C, Dehoux P, Villiers V, Adams J, Gertler F, Li R, Cossart P. The RickA protein of Rickettsia conorii activates the Arp2/3 complex. Nature. 2004;427:457–461. doi: 10.1038/nature02318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin E, Gantelet H, Egile C, Lasa I, Ohayon H, Villiers V, Gounon P, Sansonetti PJ, Cossart P. A comparative study of the actin-based motilities of the pathogenic bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella flexneri and Rickettsia conorii. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:1697–1708. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.11.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin E, Welch MD, Cossart P. Actin-based motility of intracellular pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005;8:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenklo S, Geese M, Lindberg U, Wehland J, Karlsson R, Sechi AS. A crucial role for profilin-actin in the intracellular motility of Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:523–529. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackstadt T, Messer R, Cieplak W, Peacock MG. Evidence for proteolytic cleavage of the 120-kilodalton outer membrane protein of rickettsiae: identification of an avirulent mutant deficient in processing. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:159–165. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.159-165.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlander RS, Way M, Ren Q, Howe D, Grieshaber SS, Heinzen RA. Effects of ectopically expressed neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein domains on Rickettsia rickettsii actin-based motility. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:1551–1556. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1551-1556.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzen RA. Rickettsial actin-based motility: behavior and involvement of cytoskeletal regulators. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;990:535–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzen RA, Hayes SF, Peacock MG, Hackstadt T. Directional actin polymerization associated with spotted fever group Rickettsia infection of Vero cells. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:1926–1935. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1926-1935.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AM, Cooley L. A subset of dynamic actin rearrangements in Drosophila requires the Arp2/3 complex. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:677–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng RL, Goley ED, D’Alessio JA, Chaga OY, Svitkina TM, Borisy GG, Heinzen RA, Welch MD. A Rickettsia WASP-like protein activates the Arp2/3 complex and mediates actin-based motility. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:761–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockusch BM, Murk K, Rothkegel M. The profile of profilins. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;159:131–149. doi: 10.1007/112_2007_704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang F, Laine RO, Bubb MR, Southwick FS, Purich DL. Profilin interacts with the Gly-Pro-Pro-Pro-Pro-Pro sequences of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP): implications for actin-based Listeria motility. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8384–8392. doi: 10.1021/bi970065n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleba B, Clark TR, Lutter EI, Ellison DW, Hackstadt T. Disruption of the Rickettsia rickettsii Sca2 autotransporter inhibits actin based motility. Infect. Immun. 2010 doi: 10.1128/IAI.00100-10. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loisel TP, Boujemaa R, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins. Nature. 1999;401:613–616. doi: 10.1038/44183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannherz HG, Gonsior SM, Gremm D, Wu X, Pope BJ, Weeds AG. Activated cofilin colocalises with Arp2/3 complex in apoptotic blebs during programmed cell death. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2005;84:503–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand JB, Moreau P, Paoletti A, Cossart P, Carlier MF, Pantaloni D. Actin-based movement of Listeria monocytogenes: actin assembly results from the local maintenance of uncapped filament barbed ends at the bacterium surface. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130:331–343. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JJ, Cossart P. Early signaling events involved in the entry of Rickettsia conorii into mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:5097–5106. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H, Audic S, Renesto-Audiffren P, Fournier PE, Barbe V, Samson D, Roux V, Cossart P, Weissenbach J, Claverie JM, et al. Mechanisms of evolution in Rickettsia conorii and R. prowazekii. Science. 2001;293:2093–2098. doi: 10.1126/science.1061471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Finley RW, Wright CS, Robinson HN, Schrodt BJ, Lane CC, Ekenna O, Blass MA, Tamminga CL, Ohl CA, et al. Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis and its clinical distinction from Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;47:1188–1196. doi: 10.1086/592254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, Goddard J, McLellan SL, Tamminga CL, Ohl CA. Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:805–811. doi: 10.1086/381894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policastro PF, Munderloh UG, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T. Rickettsia rickettsii growth and temperature-inducible protein expression in embryonic tick cell lines. J. Med. Microbiol. 1997;46:839–845. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-10-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl J, Crevenna AH, Kessenbrock K, Yu JH, Neukirchen D, Bista M, Bradke F, Jenne D, Holak TA, Werb Z, et al. Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:605–607. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Wiedemann U, Stuurman N, Vale RD. Molecular requirements for actin-based lamella formation in Drosophila S2 cells. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:1079–1088. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J, Agnew BJ, Abe H, Bamburg JR, Mitchison TJ. Xenopus actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin (XAC) is responsible for the turnover of actin filaments in Listeria monocytogenes tails. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:1323–1332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DA, Welch MD, Machesky LM, Bridgman PC, Meyer SM, Cooper JA. Visualization and molecular analysis of actin assembly in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1919–1930. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechi AS, Wehland J, Small JV. The isolated comet tail pseudopodium of Listeria monocytogenes: a tail of two actin filament populations, long and axial and short and random. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:155–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoble J, Auerbuch V, Goley ED, Welch MD, Portnoy DA. Pivotal role of VASP in Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation, actin branch-formation, and Listeria monocytogenes motility. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:89–100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Miki H, Takenawa T, Sasakawa C. Neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein is implicated in the actin-based motility of Shigella flexneri. EMBO J. 1998;17:2767–2776. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkina TM, Borisy GG. Arp2/3 complex and actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin in dendritic organization and treadmilling of actin filament array in lamellipodia. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:1009–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teysseire N, Chiche-Portiche C, Raoult D. Intracellular movements of Rickettsia conorii and R. typhi based on actin polymerization. Res. Microbiol. 1992;143:821–829. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theriot JA, Mitchison TJ, Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. The rate of actin-based motility of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes equals the rate of actin polymerization. Nature. 1992;357:257–260. doi: 10.1038/357257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theriot JA, Rosenblatt J, Portnoy DA, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Mitchison TJ. Involvement of profilin in the actin-based motility of L. monocytogenes in cells and in cell-free extracts. Cell. 1994;76:505–517. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers AC, Niebel A, Balague C, Dagkesamanskaya A. Differential localisation of GFP fusions to cytoskeleton-binding proteins in animal, plant, and yeast cells. Protoplasma. 2002;220:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00709-002-0026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kirk LS, Hayes SF, Heinzen RA. Ultrastructure of Rickettsia rickettsii actin tails and localization of cytoskeletal proteins. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:4706–4713. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4706-4713.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Troys M, Huyck L, Leyman S, Dhaese S, Vandekerkhove J, Ampe C. Ins and outs of ADF/cofilin activity and regulation. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2008;87:649–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DH, Ismail N. Emerging and re-emerging rickettsioses: endothelial cell infection and early disease events. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch MD, DePace AH, Verma S, Iwamatsu A, Mitchison TJ. The human Arp2/3 complex is composed of evolutionarily conserved subunits and is localized to cellular regions of dynamic actin filament assembly. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:375–384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarmola EG, Bubb MR. Profilin: emerging concepts and lingering misconceptions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen JA, Cohen Y, Hudson AM, Cooley L, Wieschaus E, Schejter ED. SCAR is a primary regulator of Arp2/3-dependent morphological events in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:689–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.