Abstract

Proteins with oxidizable thiols are essential to many functions of cell nuclei, including transcription, chromatin stability, nuclear protein import and export, and DNA replication and repair. Control of the nuclear thiol-disulfide redox states involves both the elimination of oxidants to prevent oxidation and the reduction of oxidized thiols to restore function. These processes depend on the common thiol reductants, glutathione (GSH) and thioredoxin-1 (Trx1). Recent evidence shows that these systems are controlled independent of the cytoplasmic counterparts. In addition, the GSH and Trx1 couples are not in redox equilibrium, indicating that these reductants have nonredundant functions in their support of proteins involved in transcriptional regulation, nuclear protein trafficking, and DNA repair. Specific isoforms of glutathione peroxidases, glutathione S-transferases, and peroxiredoxins are enriched in nuclei, further supporting the interpretation that functions of the thiol-dependent systems in nuclei are at least quantitatively distinct, and probably also qualitatively distinct, from similar processes in the cytoplasm. Elucidation of the distinct nuclear functions and regulation of the thiol redox pathways in nuclei can be expected to improve understanding of nuclear processes and also to provide the basis for novel approaches to treat aging and disease processes associated with oxidative stress in the nuclei. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 13, 489–509.

Introduction

The nucleus contains many of the same thiol/disulfide redox control systems as does the cytoplasm and other organelles, but accumulating evidence shows that the regulation and functions of the nuclear systems are distinct. This review summarizes current knowledge of the thiol/disulfide control systems in nuclei, their contents and redox states within nuclei, and their roles in supporting and controlling nuclear functions. The review is organized into five sections, with the first addressing the impact of changing concepts of oxidative stress on nuclear research. Important among these concepts are the recognition that nonequilibrium conditions exist in thiol/disulfide redox systems and that this necessitates inclusion of disruption of redox signaling and control as an important aspect of oxidative stress mechanisms. The second section includes current knowledge of the nuclear contents of redox control systems, principally covering glutathione, thioredoxin, and related proteins. This is followed by a section reviewing available knowledge about the steady-state redox balance of nuclear proteins. The nuclei appear to be relatively reduced and protected against oxidation, thereby emphasizing the critical nature of nuclear redox regulation. A fourth section addresses redox-dependent nuclear-import and -export mechanisms. Although studied in detail for only a small number of proteins, redox-dependent regulation of nuclear protein content may represent an important aspect of signaling for cell proliferation and differentiation as well as responses to stress. The final section covers the roles of nuclear redox systems in supporting and controlling nuclear functions. Substantial evidence is available to illustrate the importance of redox regulation of transcription, and additional research shows that studies to elucidate redox-dependent sites of DNA repair and chromatin remodeling are likely to clarify and enhance the understanding of these critical processes. The development of new methods to measure redox states of nuclear proteins under physiologic conditions provides considerable opportunity to advance further the understanding of redox control in cell nuclei.

Nuclear Redox Systems Function in Redox Signaling and Protection Against Two Types of Oxidative Stress

Nuclear redox reactions have been most frequently studied in the context of oxidative stress, but extensive research shows that central cell signaling and control systems also involve redox mechanisms. Many of these signaling pathways involve reversible oxidation of thiol-containing proteins. The redox states of these thiols are sensitive to two-electron (nonradical) oxidants and are controlled by reductant systems dependent on the thioredoxin (Trx) or glutathione (GSH). Nonradical oxidants include peroxides, aldehydes, quinones, epoxides, disulfides, peroxynitrites, and other species that can be generated enzymatically or as a consequence of nonenzymatic mechanisms. These can be quantitatively important in oxidative stress because free radical–scavenging mechanisms are efficient in maintaining free radicals at very low levels and because the nonradical oxidants are often produced at higher rates than free radicals are generated (83). Moreover, large-scale intervention trials with moderately high doses of free radical–scavenging antioxidants show little benefit in humans in terms of protection against cancer or age-related diseases. Consequently, the contemporary view of oxidative stress in disease has shifted away from a simple imbalance of prooxidants and antioxidants to disruption of redox signaling pathways dependent more on nonradical oxidants than on free radical mechanisms.

Definition of oxidative stress

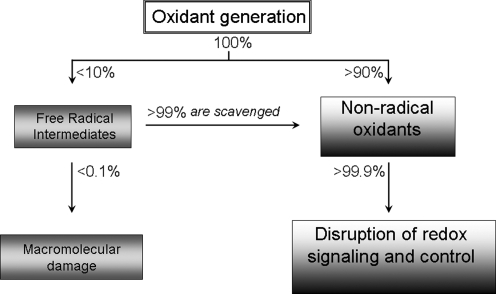

Oxidative stress has been redefined as “an imbalance in prooxidants and antioxidants with associated disruption of redox circuitry and macromolecular damage” to emphasize the critical disruption of redox signaling mechanisms that occurs during oxidative stress and the importance of nonradical oxidants in the relevant mechanisms. This new definition of oxidative stress includes two different mechanistic outcomes (Fig. 1). The first of these is macromolecular damage, such as DNA damage, that has historically been a common focus of nuclear oxidative stress, and the more contemporary study of disruption of thiol redox systems, which are gaining increasing recognition as critical determinants of normal signaling and control of nuclear functions. Whereas free radical mechanisms are readily induced by ionizing radiation and metal-catalyzed oxidation by peroxides, nonradical oxidative mechanisms involving thiols appear to predominate under more usual physiologic conditions (83).

FIG. 1.

Mechanistic outcomes of oxidative stress include both macromolecular damage and disruption of redox signaling and control. Accumulating evidence indicates that both free radical (one-electron) and nonradical (two-electron) mechanisms contribute to damage from oxidative stress. Whereas superoxide anion radical and nitric oxide are free radicals, H2O2, lipid peroxides, quinones, epoxides, peroxynitrite, disulfides, and many other chemicals are nonradical oxidants. Based on model studies with xanthine oxidase, univalent reduction of O2 to superoxide anion radical is a minor fraction of the bivalent reduction to H2O2 (41), suggesting that two-electron oxidants predominate during oxidative stress. For an arbitrary rate of oxidant generation equal to 100%, perhaps 90% would go directly to two-electron oxidants, and only 10% would be one-electron oxidants. Because free radical–scavenging mechanisms are efficient and convert free radicals into nonradical oxidants, nonradical oxidants probably constitute >99.9% of all oxidants. Unlike reactive free radicals, which are nonspecific in their destruction of macromolecules, many of the nonradical oxidants selectively oxidize thiols. Many redox signaling and control mechanisms depend on critical cysteine residues. Consequently, disruption of redox signaling and control by nonradical oxidants may have a major role in oxidative stress as a mechanism of disease.

Quantification of the partitioning of univalent (1e−) radical oxidant production and bivalent (2e−) nonradical oxidant production is not available for in vivo conditions. However, model studies by Fridovich (41) using xanthine oxidase showed that under all conditions, production of the nonradical oxidant, H2O2, predominated over the rate of superoxide generation. Because very efficient fluorescent probes are available to detect free radical generation in cells, the extensive use of these indicators may have resulted in overinterpretation of results. For instance, if nonradical oxidants are important in toxicity mechanisms and oxidative stress produces proportionately more nonradical oxidants than free radical oxidants, then free radical–dependent macromolecular damage can correlate with pathologic insult but, nonetheless, be only a relatively minor contributor to the disease process.

Redox hypothesis of oxidative stress

To facilitate the consideration of nonradical mechanisms separately from free radical mechanisms, a “redox hypothesis of oxidative stress” has been delineated (83). This hypothesis contains four postulates:

All biologic systems contain redox elements (e.g., redox-sensitive cysteine residues) that function in cell signaling, macromolecular trafficking, and physiologic regulation.

Organization and coordination of the redox activity of these elements occurs through redox circuits dependent on common control nodes (e.g., thioredoxin, GSH).

The redox-sensitive elements are spatially and kinetically insulated so that “gated” redox circuits can be activated by translocation/aggregation or catalytic mechanisms or both.

Oxidative stress is a disruption of the function of these redox circuits caused by specific reaction with the redox-sensitive thiol elements, altered pathways of electron transfer, or interruption of the gating mechanisms controlling the flux through these pathways.

These postulates are largely untested with regard to nuclear functions. However, redox-sensitive thiols are critical for the control of replication and cell proliferation, chromatin structure, DNA repair, mechanisms of transcriptional activation, transcription factor binding to DNA, and transport of proteins into and out of nuclei. Similar to signaling proteins found in other compartments of the cell, these thiol-containing proteins are susceptible to oxidation or inactivation by nonradical oxidants. Accumulating data for cellular thiol systems show that many thiols are maintained under stable but nonequilibrium conditions because of continuous oxidation/reduction turnover at a rate of about 0.5% of the total thiol pool per minute (83). Although rates of oxidant production in nuclei under physiologic conditions are not known, evidence summarized later indicates that nonequilibrium conditions of thiol/disulfide couples also exist in nuclei. Nonequilibrium thiol/disulfide redox states of regulatory proteins mean that the altered abundance and distribution of redox enzymes provide a general mechanism for control of nuclear functions. Moreover, this means that nonradical mechanisms of oxidative stress are likely to contribute to altered cell proliferation, differentiated phenotype, or other fundamental properties associated with nuclei.

Distribution of Redox Systems in Nuclei

Nuclear glutathione system

Glutathione

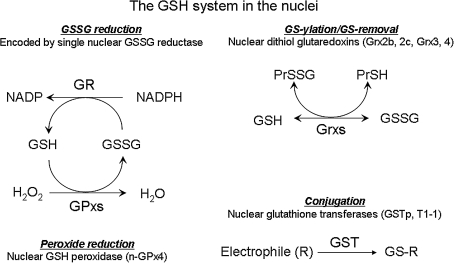

Glutathione (GSH), the most abundant low-molecular-weight thiol-containing tripeptide (γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine), plays a major role in protecting cells from oxidant-induced toxicity. Cellular GSH at millimolar levels is widely distributed within cells and determines cellular redox state, based on the ratio of [GSH]2 to its disulfide form [GSSG]. Although a number of important functions of GSH are implicated in cell physiology and pathophysiology, relatively few studies have provided spatial or compartmental resolution to address specific functions in nuclei. Previously, important roles for GSH were shown for DNA synthesis and cell proliferation (71, 182), regulation of the nuclear matrix organization (29), and maintenance of Cys residues on zinc-finger DNA-binding motifs in a reduced and functional state (96). These results show that GSH plays a pivotal role in nuclear function. In this review, Cys-containing proteins regulating the GSH system (Fig. 2), including glutathione reductase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutaredoxin and glutathione S-transferase in nuclei, are discussed.

FIG. 2.

The GSH systems in the nuclei. Although systematic studies are limited, an extensive literature describes the GSH systems associated with nuclei. These include GSH, GSSG reductase (nuclear GSSG reductase), GSH peroxidase (n-Prx), glutaredoxins (Grx2b and Grx2c for human, Grx3 and Grx4 for yeast), and GST (GSTp and GST T1 are present in the nuclei). Many of these systems are identical or functionally equivalent to the cytoplasmic forms. However, the GSH systems exist under nonequilibrium redox conditions, so that function depends on abundance and distribution of individual redox components. In addition, changes in electron flow from NADPH or reduction of endogenously produced peroxide can change the steady-state redox potential and thereby control protein functions.

Glutaredoxins

Glutaredoxins (Grxs) are thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases that catalyze GSH/GSSG redox reactions with cysteine residues of target proteins (70). Grxs are classified into two main groups, dithiol Grxs and monothiol Grxs, depending on the active-site consensus sequences containing –Cys-Pro-Tyr-Cys– and –Cys-Gly-Phe-Ser–, respectively (106). Monothiol Grxs can be further categorized into single-domain monothiol Grxs containing one Grx domain and multidomain monothiol Grxs containing a Trx-like domain and one to three monothiol Grx domains.

All dithiol Grxs catalyze monothiol reactions, as shown by the hydroxyethyl disulfide assay, a general method used to measure Grx activity (106). Dithiol Grxs reduce protein disulfides through a mechanism involving two Cys in the active-site motif, whereas monothiol Grxs function to deglutathionylate GSH-protein mixed disulfides through a monothiol mechanism involving one Cys in the active site (36). Two monothiol Grxs, cytoplasmic Grx3 and mitochondrial Grx5, occur in human cells. Grx3 is a multidomain monothiol form, and Grx5 is a single-domain monothiol form. Four dithiol Grxs are found in human cells. These include Grx1 in cytoplasm, Grx2 (Grx2a) in mitochondria, and Grx2b and Grx2c in cytoplasm and nuclei. Grx2b and Grx2c are transcript variants derived from Grx2a, localized exclusively in mitochondria. Grx2c, but not Grx2b, forms an Fe-S cluster in an in vitro reconstitution assay (107). Grx2a and Grx2b expression was limited to testis in nontransformed cells, whereas expression was found in a broad range of transformed cancer tissues, including those of blood, breast, cervix, lung, and the nervous system (107). The pattern of distribution of Grxs among organelles and altered abundance in cancer suggests a complexity in functions of Grxs that is currently not understood.

Localization of Grxs in nuclei was recently identified. Specifically, Grx2b and Grx2c were found in nuclei of human cells, and Grx3 and Grx4 were found in nuclei of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells (119). Compared with isoforms of Grxs found in other organelles, fewer functional studies of nuclear Grxs have been reported. Two research groups, Pujol-Carrion et al. (147) and Ojeda et al. (133), characterized a function for Grx3 and Grx4 in S. cerevisiae in cellular iron homeostasis. This occurs through the regulation of Aft1, a transcription factor regulating the high-affinity iron-uptake genes. The translocation of Aft1 from nuclei to cytoplasm was directly regulated by Grx3 and Grx4 as consequence of interacting with Aft1 (147). The glutaredoxin domain of Grx is essential for binding and control of Aft1 and suggests an important role for GSH in this mechanism (133).

A recent study suggests that critical nuclear functions of nuclear Grx can serve as a target for anticancer treatment. Message levels of Grx2b, and also of thioredoxin reductase-1, were examined with quantitative PCR and found to be significantly increased in leukemic cells from acute myeloid leukemia patients after treatment with selenite, a potent inhibitor of malignant cell growth (137). In principle, the increase in specific nuclear forms of Grx, which are expressed in cancer cells, could provide a target to kill rapidly proliferating cancer cells selectively.

GSH S-transferase

The mammalian glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are phase II detoxification enzymes that function in elimination of drugs and other xenobiotics. GST catalyzes detoxification of reactive electrophilic compounds, including carcinogens, therapeutic drugs, environmental toxins, and products of oxidative stress, by conjugation with GSH. Increasing evidence supports a protective role of GST in oxidative stress and also a role in the regulation of ROS-mediated cell signaling. Importantly, the GST expression level shows significant correlation with cancer development. This increase is associated with growth and resistance of cancer cells; in addition, GST can provide a biomarker for early stages of cancer development.

Four major cytosolic GST families, including Alpha, Mu, Pi, and Theta (65), and four minor families, Zeta, Sigma, Kappa, and Omega, have been identified (179). Studies on subcellular localization show that most GSTs are localized in the cytoplasm. However, some of the alpha class GSTs are associated with the plasma membrane, and other forms from different families are found in mitochondria and nuclei. The endoplasmic reticulum contains microsomal GSTs (mGSTs), which are present as trimers and are structurally and immunologically distinct from the cytosolic GST (112), which are present as dimers of subunits (171).

GST alpha was detected in nuclei of human hepatocytes (15, 181), rat Purkinje cells, and neurons (81). The mGST not only was found in microsomal fractions but also was observed in nuclei of primary spermatocytes (139). The presence of the class theta GST T1-1 in the nucleus of mouse and human liver cells was confirmed with histochemical analysis (172). Nuclear expression of GSTpi (GSTp) occurs in cancer tissues (52, 85, 138), although it also was found in mitochondria (52). Increases in the expression of GSTp have been detected in precancerous cells and various cancer tissues, animal-type melanoma (138), hepatocarcinogenesis (165), prostate cancer (116), gynecologic cancers, urinary cancer cells (173), and glioma cells (2).

Nuclear expression of human GSTp is associated with anticancer drug resistance (53, 117). Nuclear accumulation of GSTp in cancer cell lines was observed in response to treatment with the anticancer drugs cisplatin, irinotecan hydrochloride, etoposide, and 5-fluorouracil (53). Inhibition of nuclear localization of GSTp-sensitized cells to cytotoxicity suggested that nuclear GSTp protected DNA against anticancer drug–induced damage (52, 53). Additional evidence supports the protective role of nuclear GSTp against H2O2-induced DNA damage (85). A negative relation between animal-type melanoma and nuclear GSTp levels also supports a critical role of nuclear GSTp in nuclear protection (138). Mechanistic studies of the regulation of GSTp in association with carcinogenesis showed that the GSTp gene expression was regulated by transcription factor C/EBP (CAAT enhancer–binding protein)α for suppression in normal liver, whereas the Nrf2 (NF-E2 p45-related factor 2)/MafK heterodimer was required for activation during hepatocarcinogenesis (165).

GSSG reductase

Glutathione reductase (GR) is a ubiquitous enzyme required for reduction of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) to GSH by NADPH. GR is a homodimeric flavoprotein consisting of subunits with a molecular mass of 55 kDa and containing two FAD molecules. The dimeric nature of this enzyme is maintained in the presence of GSH, which is critical for its catalytic activity. GR is found in most organisms from prokaryotes to eukaryotes. Biochemical activity of the GR present in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of mammalian cells is identical (46). Both the human and the mouse GR contain mitochondrial targeting sequences in the N-terminal region (89). As identified in a group of proteins, such as DNA-ligase and DNA-glycosylase, with different compartmental expressions of proteins encoded by a single nuclear gene (102, 140), GR is a product of a single nuclear gene that is expressed in cytoplasm, mitochondria, nuclei, and nucleoli. Truncations of the N-terminal domains of pea GR (pGR) resulted in significantly different organellar targeting patterns compared with wild-type pGR, suggesting that the N-terminal domain of the dual-targeted pGR signal peptide controls organellar targeting efficiency (162).

Earlier studies showed that GSH-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms are significantly compartmentalized (176). Rogers et al. (158) studied hepatic nuclear and nucleolar GR, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and GST expressions, and their activities in response to hepatic necrosis. They found that these distributions differed in female rats from those of male rats, suggesting significant roles for these enzymes in the different compartments. They also observed greater nuclear GR activities of CHO (Chinese hamster ovary) cells during S-phase than during other stages of the cell cycle, suggesting that a nuclear GR controls the cell cycle (159).

A significant number of studies support the critical function of GR in a variety of diseases. Expression levels and activities of GR and GPx were decreased in patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and transitional meningioma (TM), when compared with normal brain tissues. However, protein oxidation levels measured by protein carbonyl content were increased in GBM and TM, perhaps because of the decreases in other antioxidant systems (185). The role of GR in zinc-induced toxicity was shown by studies in human lung cell lines and rat astrocytes (6, 193). BCNU inactivation of GR sensitized cellular zinc toxicity by increasing the cellular GSSG level. This result suggests that GSSG itself is an important effector in zinc cytotoxicity, perhaps mediated by Grx reactions, as described earlier.

A role of GR in cardiovascular disease (CVD) also has been investigated (104, 149, 196) but specific nuclear functions have not been delineated. Decreased levels of GSH and GSH-related antioxidant enzymes, GR, GST, GPx, have been observed in human atherosclerotic lesions. Conversely, overexpression of GR targeted to cytoplasm or mitochondria in bone marrow–derived cells protected cells from oxidized LDL-induced mitochondrial hyperpolarization and reduced atherosclerotic lesion formation (149). Studies to define the role of GR in CVD have been extended to the regulation of signaling pathways. Laminar shear stress activated antiapoptotic signaling, including activation of Akt followed by eNOS activation, and increased NO production was regulated in a GR-dependent manner (195). This finding suggests that the more-reduced GSH redox system caused by laminar shear stress has a protective role in apoptosis, inflammation, and further CVD, by controlling cellular signaling.

Because of the large body of evidence showing a critical role of GR in cytotoxicity and diseases, additional studies focused on nuclear-localized GR are warranted. The redox potential of the nuclear GSH/GSSG couple is kinetically controlled and at least partially autonomous from the cytoplasmic compartment. Consequently, additional studies on the regulation of nuclear GR will be important to understand the functions and control of the nuclear GSH/GSSG system.

Glutathione peroxidase

Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) catalyzes the reduction of H2O2 or organic hydroperoxides to H2O and respective alcohols by using GSH as a reductant. Eight types of GPx (GPx1-8) have been characterized. The GPx family is one of the 25 known classes of selenoproteins (98), and all members, except for GPx5 in humans and mice, GPx7, and GPx8, contain a selenocysteine necessary for catalytic activity. Several of these selenoproteins, including GPx, selenoproteins P (67), W (191), and R (38), and thioredoxin reductases, have antioxidant functions, and deficiencies in these selenoproteins are associated with cancer. Most GPxs are tetramers. Each monomer of GPx1, GPx2, GPx3, GPx4, and GPx6 contains selenocysteine (98). In contrast, GPx5, GPx7, and GPx8 contain cysteine at the catalytic site. Although differing in the active site, GPx8 and GPx4 share structural similarities. Individual disruption of GPx1 and GPx2, alone or in combination, shows mild phenotypes (20, 33), whereas GPx4 deficiency resulted in embryonic lethality (74, 203). Mice deficient in GPx3 also have been reported to be viable, suggesting that GPx4 is a uniquely critical selenoprotein (22).

GPx4 has previously been described as a phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx) because of its unique biochemical functions toward phospholipid hydroperoxides, which are formed during lipid peroxidation (188). Despite its similarities to other GPxs in terms of structure and biochemical properties, many differences exist between GPx4 and other GPx members. A major structural difference is that GPx4 is a monomer, whereas the others are tetramers (187). In addition, GPx4 has a broad range of substrate specificities in addition to H2O2, including derivatives from cholesterol and cholesteroyl esters and thymine hydroperoxide (74). Previous findings also suggest that GPx4 functions as a structural protein and as a regulator of apoptosis and gene expression (168).

Examination of GPx4 expression shows unusual patterns in tissue distribution with a specific nuclear form. GPx4 is widely expressed in normal tissues but is especially high in the testis (11). GPx4 levels were normal even under selenium restriction, whereas others (e.g., GPx1) were more sensitive to the restriction (12, 167). Three different isoforms of GPx4 exist, differing in their 5' extension; these are derived from a single gene and include cytosolic (c-GPx4), mitochondrial (m-GPx4), and nuclear (n-GPx4) forms (144, 148). The m-GPx4 is higher than c-GPx4 in molecular mass; however, the mitochondrial targeting sequence is cleaved off in the mitochondria so that these two processed GPx4 forms are not distinguishable in their primary structures. The c-GPx4 is predominant in most mammalian tissues; however, in testis, the m-GPx4 expression was dominant. Independent of c-GPx4 and m-GPx4, the n-GPx4 (also called snGPx for sperm nucleus–specific GPx) was predominantly expressed in late spermatids and spermatozoa (24). The nuclear-targeting sequence was retained in this protein even after nuclear import, resulting in the higher molecular mass of n-GPx4 (34 kDa) than other isoforms (19 kDa, c-GPx4 and m-GPx4). In studies of n-GPx4 KO mice, Conrad et al. (24) concluded that n-GPx4 is not an indispensable player in spermatozoon physiology because KO mice develop normally, are fertile, and do not show any morphologic or functional defects. However, mice lacking n-GPx4 showed instability of the sperm nuclei, implying that n-GPx4 plays an important role in stabilizing nuclear structures in spermatozoa. To date, the mechanism for nuclear import of n-GPx4 has not been established, and the specific biologic function of n-GPx4 in spermatogenesis remains to be elucidated.

Nuclear thioredoxin system

Thioredoxin

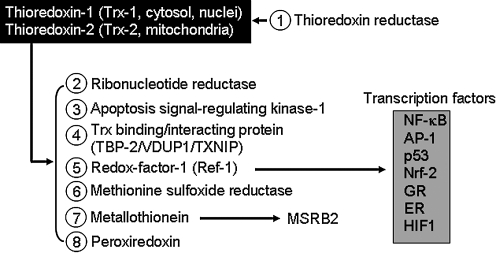

Thioredoxins (Trxs) are small thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases (12 kDa) involved in a wide range of cellular redox processes (Fig. 3) and essential for the maintenance of cellular redox signaling and control (72). Trx is oxidized during the conditions of oxidative stress caused by chemical, physical, or biologic stimuli (18, 50, 57). Oxidized Trx is reversibly reduced by NADPH and thioredoxin reductase, whereas reduced Trx is used for reduction of peroxiredoxins (Prxs) (157).

FIG. 3.

Thioredoxin-regulated cellular redox processes. (1) Thioredoxin (Trx) is reduced principally by thioredoxin reductases (TrxR). (2) Trx is an electron donor to support the activity of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR). (3) Trx binds to apoptosis signal-regulated kinase-1, inhibiting the kinase function. (4) Trx1 activity is inhibited by binding to Trx-binding protein-2 (TBP-2), also known as VDUP-1 and TXNIP. (5) Trx1 reduces redox factor-1 (Ref-1), a bifunctional protein with a redox activity and a separate DNA repair (APE-1, endonuclease) activity in nuclei; the redox activity maintains conserved Cys residues of transcription factors [NF-κB, AP-1, p53, Nrf2, glucocorticoid receptor (GR), estrogen receptor (ER), and HIF1] in the reduced form required for DNA binding. (6) Trx1 functions as a reductant for methionine sulfoxide reductases (MSRs). (7) Trx1 controls a pathway for MSRB2 reduction mediated by metallothionein. (8) Trx acts as a reductant for peroxiredoxin (Prx) activity to scavenge peroxides.

Two isoforms of mammalian Trx, Trx2 and Trx1, have been identified, and both are well studied. Trx2 is localized to mitochondria and has a protective function against mitochondrial oxidative stress. Similar to Trx1, Trx2 also functions as a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase, which is controlled by thioredoxin reductase (TrxR2) and peroxidases (peroxiredoxin-3 and −5) in mitochondria. Trx2 protects against oxidant-induced cell death (19, 62), and recent evidence shows that increased mitochondrial Trx2 alters abundance of proteins controlled by nuclear gene expression (Hansen, et al., unpublished data). Interestingly, Prx5 is found in nuclei as well as mitochondria, but the functional significance of this is unclear.

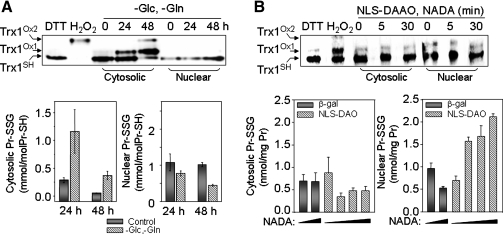

Trx1 is found in cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments. The redox state of Trx1 in the cytoplasm and nuclei regulates cell death and survival signaling by controlling interactions with Trx1-binding proteins (164). Nuclear Trx1 is functionally autonomous from cytoplasmic Trx1. A distinct nuclear existence of Trx1 has been demonstrated by immunohistochemical studies, suggesting that Trx1 is imported into the nucleus during oxidative stress (69, 169, 177, 197). Spielberger et al. (177) found that cells in sparse culture have increased ROS level, and oxidation of both Trx1 and GSH redox states. In sparse cultures, nuclear localization of Trx1 was high relative to high-density cultures, indicating that the redox environments of the cytoplasm and the nucleus are distinct and that Trx1 has an important role of nuclear redox state in cell growth. A previous study examining the oxidation of the thiol-dependent antioxidant systems in subcellular compartments under conditions of limited energy supply of human colonic cancer cells showed that oxidative stress induced by depletion of glucose and glutamine affects the redox states of proteins in the cytoplasm and mitochondria more than those in the nucleus (Fig. 4). The results showed that the nuclear compartment has better protection against oxidative stress than does cytoplasm or mitochondria (50). Another study showed that nuclear GSH is more susceptible to localized oxidation than is nuclear Trx1 (56). This study examined the effect of nuclear H2O2 generation on the nuclear thiol/disulfide redox systems by targeting d-amino acid oxidase (DAO) to the nucleus. The results showed that nuclear Trx1, measured with redox Western blot analysis, was resistant to oxidation by DAO-induced H2O2. In contrast, the nuclear GSH system, measured with nuclear protein glutathionylation, was sensitive to oxidation. Under these conditions, neither cytoplasmic Trx1 nor cellular GSH/GSSG showed oxidation. Thus, the results show that the nuclear Trx1 and GSH systems are functionally distinct from the cytoplasmic systems and also respond independently to oxidant generation (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Quantification of nuclear redox state measured with Trx1 redox Western blotting and protein glutathionylation. Cells exposed to oxidative stress by depleting glucose (Glc) and glutamine (Gln) from culture (50) or by expressing nuclear-targeted d-amino acid oxidase (NLS-DAO) with variation of substrate amounts (N-acetyl-d-alanine, NADA) (56) were analyzed for cytoplasmic and nuclear redox-state measurements. (A) Nuclear Trx1 and GSH/GSSG were resistant to oxidation by Glc and Gln depletion, compared with cytoplasm. (B) Protein glutathionylation in nuclei was substantially increased by NLS-DAO expression, whereas no detectable change was seen in cytoplasmic protein glutathionylation or Trx1 oxidation in either cytoplasm or nuclei.

Another protein containing a conserved Trx domain is termed nucleoredoxin (42). This protein is more similar to tryparedoxin, a Trx family protein originally identified in parasitic trypanosomes, than to thioredoxins. The protein was originally localized in nuclei, but subsequent studies show that it functions to regulate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and is principally cytoplasmic. The apparent contradiction appears to be due to formation of complexes with Dv1 and PP2A, which can shuttle between nuclei and cytoplasm under different signaling conditions (42).

Peroxiredoxins

Peroxiredoxins (Prxs) are antioxidant enzymes that were initially identified in yeast, based on their protection of glutamine synthetase against oxidation (91). Prxs undergo a cycle of peroxide-dependent oxidation and thiol-dependent reduction during their catalytic turnover. Oxidized Cys residues in the Prx are reduced by Trx specifically and not by GSH or Grx. The six isoforms of Prx are termed Prx1 through Prx6 in mammalian cells. These proteins are divided into three groups, including 2-Cys Prx (Prx1, Prx2, Prx3, and Prx4; each contain two conserved Cys in both N- and C-terminals), atypical 2-Cys Prx (Prx 5; contains only the N-terminal Cys and requires the other nonconserved Cys for activity), and 1-Cys Prx (Prx6; contains only the N-terminal Cys and requires only this conserved Cys for activity) (170). Prx1, 2, and 4 exist mainly in cytoplasm but also are found in nuclei, whereas Prx3 is localized exclusively in the mitochondria (86, 157). Prx5 is found in mitochondria, cytoplasm, nuclei, and peroxisomes (132, 170).

The catalytic functions of Prx involve multiple oxidized forms of the conserved Cys. Initial oxidation by peroxide involves oxidation of the thiol to a sulfenic acid form (200). This represents a two-electron equivalent oxidation and can be readily converted to a disulfide by reaction with another protein thiol, thereby releasing water. The disulfide is then reduced by Trx to regenerate thiols. The two conserved Cys residues in Prx1 through Prx4 were characterized to form intermolecular disulfides resulting in homodimers, but also exist in decameric forms on overoxidation (200). Overoxidation of the active site Cys to Cys-sulfinic (−SO2H) or Cys-sulfonic acid (−SO3H) can occur during peroxide oxidation (151) and result in inactivation of peroxidase activity. Oxidation-induced inactivation of Prx can be reversed by ATP-dependent reductases, termed sulfiredoxins (7, 16). The loss of peroxidase activity has been suggested to lead to a functional change from a peroxidase to a molecular chaperone under stress conditions (79, 120).

Structural studies show that, in addition to existing as a homodimer, Prx4 also interacts with small proteins such as Prx1 to form heterodimers. Prx4 is present in the cytoplasm and is also translocated to the extracellular space because of secretory signal sequences included in the N-terminal region (115). Prx5, localized in cytosol, mitochondria, and peroxisome, has been characterized to form two intermolecular disulfide bonds, which then rearrange to form intramolecular disulfides during peroxide-induced oxidation (34). The one N-terminal Cys of Prx6 is readily oxidized by peroxide, resulting in Cys-sulfenic acid (−SOH) (21).

The presence of multiple Prxs in various subcellular compartments suggests that the different Prx forms could have different functions in different compartments within cells. This possibility has been supported by studies with approaches including transient overexpression of Prx in cells (4, 60) and knockout Prx1 in mice (31). Egler et al. (31) showed that embryonic fibroblasts from Prx1 KO mice (Prx I−/−) have localized, increased ROS levels in the nucleus, resulting in DNA damage. This research provides evidence for a critical role of Prx1 for the regulation of ROS levels specifically in the nucleus (31). Overexpression of human Prx5 targeted to the nucleus confers resistance to hydrogen peroxide and tert-butylhydroperoxide–induced cell death and DNA damage (4). In addition, the use of nuclear- and cytoplasmic-targeted Prx1 to study effects on transcriptional activation, as described later, suggests that Prx1 governs the compartment-specific redox signaling and control mechanism during oxidative stress (60). This research specifically indicates that a dynamic regulatory mechanism can exist in nuclei in which a constitutive generation of H2O2 provides continuous oxidation of protein thiols, in opposition to reduction by the Trx1 system (Fig. 5). This mechanism provides an “off” mechanism for transcription factors that have a conserved Cys in the DNA-binding region that must be reduced for DNA binding (see later).

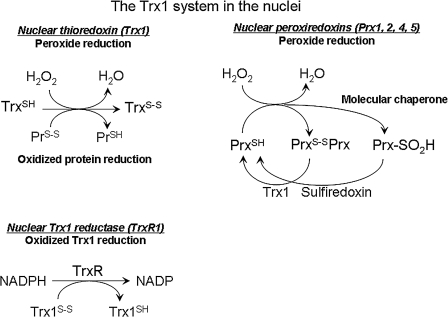

FIG. 5.

The thioredoxin-1 (Trx1) system in nuclei. The Trx system, including Trx1, thioredoxin reductase-1 (TrxR1), and Trx peroxidases (Prx1, Prx2, Prx4, and Prx5), is present in the nuclei. TrxR1 reduces oxidized Trx1 in the presence of NADPH. Trx1 functions to reduce peroxides and disulfide forms of oxidized proteins, such as Prx, which eliminates peroxides. Overoxidized Prx (Prx-SO2H) functions as a molecular chaperone and is reduced by sulfiredoxin.

Similar to the control of transcription-factor activity by Trx1, Prx-controlled regulation of transcriptional factors, including Yap1, NF-κB, Nrf-2, and c-Myc, has been demonstrated (60, 93, 136). Nuclear localization and activation of yeast transcription factor Yap1 was controlled by Tsa1, a ubiquitous Prx in yeast, by regulating intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels (136). In addition, direct interaction of Prx1 with c-Myc through MBII (Myc Box II) was shown to alter the c-Myc transcriptional activity, although the functional consequences of this interaction are complex and remain unclear (121). Expression of nuclear-targeted Prx1 in HeLa cells increases NF-κB binding to DNA and reporter expression (60). Prx2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts have stimulated Ras, ERK, and NF-κB activation, suggesting that Prx II inhibits the pathway of Ras-ERK-NF-κB through controlling cellular ROS levels (59). Together, the data indicate that cytoplasmic and nuclear Prx distribution are part of a compartmentalized redox control mechanism allowing oxidative activation in the cytoplasm and oxidative inactivation in the nuclei.

Thioredoxin reductase

Thioredoxin reductases (TrxRs) catalyze the NADPH-dependent reduction of Trx and other oxidized cellular proteins. They belong to the pyridine nucleotide-disulfide oxidoreductase protein family and are ubiquitously found in mammalian tissues. TrxRs are homodimers, with each subunit containing a C-terminal selenocysteine necessary for catalytic activity (47). Three isoforms of mammalian TrxR have been identified: TrxR1 is localized to the cytoplasm and the nuclei; TrxR2 (also known as TR3) is localized to the mitochondria; and TrxR3 is expressed mainly in testis. TrxR3 is distinct, in that it has combined Trx and GSSG reductase activities (124). Cytosolic and nuclear TrxR1 and mitochondrial TrxR2 function independently (125, 143), and elimination of either TrxR1 or TrxR2 gene results in an embryonic lethal phenotype (23, 78).

Similar to the role of Trx in redox-sensitive signaling, TrxR also appears to regulate multiple downstream redox-sensitive proteins. Trx1 is translocated from cytoplasm to the nucleus, in association with the activation of NF-κB during oxidative stress induced by UVB irradiation or TNF-α treatment (69). A study from Karimpour et al. (87) suggests that TrxR1 has a role as a signaling factor that controls transcription factor activity, such as AP1 and subsequent gene expression by mediation of Trx1 nuclear localization. A recent study examining changes in expression level of TrxR1 under different growth rates shows higher nuclear expression of TrxR1 in proliferating cells than in nonproliferating cells (174). In CWR22 cells, which resemble androgen-dependent human prostate cancer, TrxR1 is expressed predominantly in the nucleus. Although the biologic function and reasons for the existence of TrxR1 in the nucleus are not firmly established, these findings suggest that the nuclear TrxR1 could be selectively targeted to enhance specificity in cancer therapy.

Quantification of Redox State in the Nucleus

Substantial advances have been made during the past several years in understanding the regulation and functions of thiol/disulfide systems in different subcellular compartments. One of the means to compare thiol/disulfide couples is to express the oxidation–reduction states in terms of the steady-state redox potentials, Eh. These potentials are calculated by using the Nernst equation and respective concentrations of reduced and oxidized components, taking into account the inherent tendency of the couple to accept or donate electrons, as expressed in the standard potential (Eo) for the respective couple. Analyses using currently available techniques show that the relative redox states from most reducing to most oxidizing are mitochondria (−330 mV) > nuclei (−280 mV) > cytoplasm (−250 mV) > endoplasmic reticulum > extracellular space (−150 mV) (62, 82), with some differences due to whether values are expressed for Trx or GSH. Data for different cell types are often similar, but five- to six-fold variation also can occur (62).

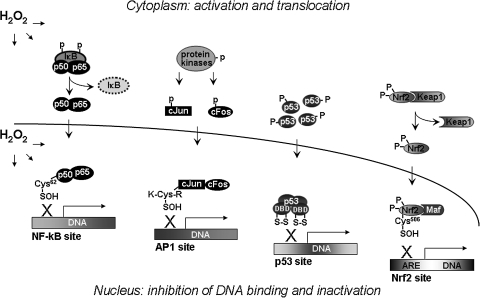

Approaches to measure steady-state redox potentials have shown that the nuclear compartment is maintained at a more-reduced value than is cytoplasm (48) and that the GSH/GSSG and Trx couples in different compartments are not in thermodynamic equilibrium (90). The nuclear redox systems dynamically interact with those in other redox compartments. This is evident in the regulation of transcription by nuclear thiol-disulfide redox-dependent mechanisms. Oxidants in the cytoplasm stimulate oxidative stress signaling, which allows transcriptional activation to enhance systems to protect from uncontrolled oxidative reactions involving lipid peroxidation, DNA crosslinking, and irreversible sulfur hyperoxidation. The fine-tuned redox control systems maintain relatively reduced intracellular redox states, despite responses to oxidative stimuli. A surprising and unexpected aspect of these responses is that major systems controlling cell fate, including signaling of cell survival, growth, and death, involve oxidants in the signaling mechanisms, including those for DNA synthesis, enzyme activation, cell-cycle regulation, and gene expression. However, this research also shows that oxidative stress–caused inactivation of transcription factors is critically important in cell processes, resulting in mutation of DNA and causing subsequent cell death (68). Thus, a general model has emerged (Fig. 6) in which cytoplasmic oxidants activate translocation of transcription factor proteins from the cytoplasm to the nuclei to activate transcription, whereas a nuclear oxidative mechanism, as described in Fig. 5, functions in opposition to turn off the system.

FIG. 6.

A model for transcription-factor regulation in the cytoplasm and nuclei by oxidants. Cytoplasmic oxidants stimulate phosphorylation and translocation of transcription-factor proteins (NF-κB, AP-1, p53, and Nrf2) from the cytoplasm to nuclei to activate transcription. A nuclear oxidative mechanism oxidizes critical Cys residues in the DNA-binding region of the transcription factors and inhibits binding to DNA. This oxidative reaction inactivates transcriptional functions to turn off the system. Thus, the nuclear Trx1 and GSH systems have two functions in the nuclei: maintenance of the oxidant tone, which turns off the transcription factors, and repeated reduction of the critical Cys residues through Ref1 to maintain DNA binding.

Generalizations must be made cautiously because the number of studies and variety of methods available are limited. However, current evidence indicates that, in addition to being relatively reduced, the nucleus is relatively resistant to oxidation by exogenously supplied oxidants. The most widely used methods are described later and involve redox Western blot analysis of Trx1 and quantification of protein S-glutathionylation. Newly available methods to image the GSH redox state by using a fusion of glutaredoxin-1 and a redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein provide a means to measure nuclear redox in live cells (55). In addition, a redox proteomics method provides the means to quantify thiol/disulfide redox changes in specific Cys in different nuclear proteins (49, 62).

Methods to measure nuclear redox states

A previous review summarizes approaches to distinguish nuclear redox states from those in the cytoplasm [see Table 2 and Fig. 2 in the review (48)]. These methods focus on thiol/disulfide redox states of Trx1 and GSH/GSSG because these are abundant molecules present in different subcellular compartments (48, 49); their oxidation provides direct evidence of compartment-specific oxidative stress. Previous studies show Trx1 translocation into the nucleus occurs in response to a variety of stimuli, including oxidants, UV irradiation, cytokines, and lipopolysaccharide (69, 198) in cell-culture and animal models (183). Translocation of Trx1 into nuclei in response to stress may support antioxidant and repair functions. Consequently, the increased Trx1 level in the nuclei may provide a more-reducing environment required for DNA binding by transcription factors. Existence of Trx1 in both the cytoplasm and nucleus enables redox states to be determined in these compartments by comparable redox measurement of Trx1 in cytosolic and nuclear fractions. In addition, cotransfection of cells with NLS-Trx1 (nuclear localization signal-linked, Myc epitope-tagged Trx1) and NES-Trx1 (nuclear export signal-linked, HA epitope-tagged Trx1) plasmid DNA provide tools to compare Trx1 redox state in cytoplasm and nuclei without fractionation (Y-M. Go and D.P. Jones, unpublished data). The latter has the benefit that measurement of redox states of compartment-targeted proteins, NLS-Trx1 for nuclei and NES-Trx1 for cytoplasm, reduces the possible artifactual oxidation in the Trx1 redox state during subcellular fractionation.

In parallel with Trx1 redox measurements, quantification of the GSH/GSSG redox state has been considered another tool to estimate nuclear redox. Technical difficulties in measuring GSH levels in the nuclear compartment have resulted in contradictory interpretations (5, 13, 27, 192). An alternative to measurement of GSH, which can diffuse out of nuclei during fractionation, is to quantify S-glutathionylated protein (Pr-SSG) in the nuclei, which is less subject to artifactual redistribution and provides an indirect estimation of nuclear GSH/GSSG. Pr-SSG can be formed from a reaction of GSSG with protein thiols (PrSH), as well as reaction of oxidized proteins with GSH by GSH S-transferases or thiol peroxidases. Glutathionylation of protein is a dynamic and reversible process thought to be involved in redox regulation of proteins in physiologic as well as pathologic conditions. Molecular mechanisms, quantitation methods, and the potential clinical significance of protein gluatathionylation were discussed in a recent review article (28). S-Glutathionylated hemoglobin has been analyzed as a marker of oxidative stress in some human diseases, including Friedreich ataxia, type I and type II diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia and uremia associated with hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, Down syndrome, and atherosclerosis (28). Increased glutathionylation of crystallins, human eye-lens proteins, was observed in aging human lenses and was correlated with nuclear color and opalescence, suggesting that Pr-SSG may play an important role in the cataractogenesis of aging (108).

Measurement of Pr-SSG concentrations in nuclei and cytoplasm can be obtained after nuclear isolation. Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions are reduced with DTT, releasing GSH for HPLC analysis (105). Stimulated nuclear production of H2O2 by targeting d-amino acid oxidase to nuclei resulted in increased protein glutathionylation in the nuclei, but not in the cytosol (56). In contrast, culture of cells in media depleting glucose and glutamine resulted in increased protein S-glutathionylation in the cytosolic fraction but not in the nuclei (50). Thus, the data show that protein S-glutathionylation is independently controlled in the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments and indicate that the GSH/GSSG redox potential is more reduced in nuclei than in cytoplasm.

Redox-dependent Nuclear-Import and -Export Mechanisms

Transport of molecules across the nuclear envelope is highly selective and regulated. Transported molecules include proteins, such as transcription factors that move from the cytoplasm to the nuclei and RNA that move toward to the cytoplasm. Generally, transport mechanisms begin with recognition of a protein by its cognate nuclear-transport signals, including nuclear-localization signal (NLS) (80) and nuclear-export signal (NES) (35) within the protein that mediate its nuclear import and export, respectively. Proteins containing NLS are recognized by a heterodimeric receptor, importin (or karyopherin) (51, 154); however, proteins that do not contain classic NLS, such as the mRNA-binding protein, hnRNPA1, do not interact with importin-α/β. The hnRNPA1 interacts with a different import receptor, a family of proteins related to importin-β [e.g., transportin, for nuclear import (10)]. For nuclear exit, proteins contain NES, which are short stretches of leucine-rich amino acid sequences. The NES regions interact with exportins such as CRM1, proteins that are also members of the importin-β family (39, 178).

Glucocorticoid receptor function is directly regulated by Trx1 through interaction with the DNA-binding domain (111). In addition, Okamoto et al. (135) used a chimeric human glucocorticoid receptor fused to green fluorescent protein and found that nuclear translocation of this receptor was impaired under oxidative conditions in living cells. The C481S mutant of the NLS was not sensitive to oxidative treatment, indicating that C481 is a target amino acid for redox regulation of import. This research demonstrates a direct redox dependence of import due to the presence of a redox-sensitive amino acid in the nuclear localization signal. A similar redox sensitivity is present in the nuclear-export signal (NES) for the fission yeast AP-1–like transcription factor (Pap1) (99, 100). Pap1 is negatively regulated by CRM1/exportin 1, the nuclear export factor. Deletion of the C-terminal cysteine-rich domain (CRD) resulted in nuclear accumulation of Pap1, and deletion and mutational analyses of the CRD showed that C532 was important for Pap1 export. Cys mutation-induced inhibition of nuclear export suggests that this NES provides a redox-sensitive mechanism for controlling nuclear export of Pap1. Consequently, oxidizable Cys residues in both NLS and NES sequences provide switchable mechanisms for redox control of nuclear import and export.

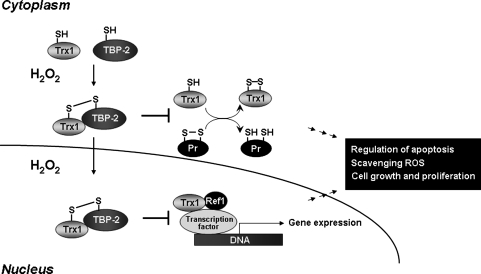

As discussed earlier in this review, Trx1 is present in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. The mechanism for the oxidative stress–induced nuclear import of Trx1 has been studied (69, 169, 197). Schroeder et al. (169) found that under physiologic levels of H2O2 and nitric oxide, nuclear translocation of Trx1 was controlled by an importin (karyopherin)-α–dependent mechanism. Nuclear Trx1 then provides antiapoptotic properties by binding to several transcription factors and increasing transcription-factor binding to genes through the antioxidant response element, ARE (169). Thioredoxin-binding protein-2 (TBP-2), also known as vitamin D3-upregulated protein-1 or Trx-interacting protein (TXNIP), binds to Trx1 and negatively regulates Trx1 function (Fig. 7). TBP-2 bound to Trx1 accumulated in the nuclei on stress through direct interaction with Rch1, a member of the importin-α family (128). Several reports confirmed that TBP-2 inhibited the reducing activity of Trx1 (84, 129), and that its expression was downregulated in various tumor cells (14, 73). Additionally, Nishinaka et al. (128) found that nuclear localized TBP-2 was imported by interacting with Rch1, so that importin-α functioned as a growth suppressor. In the same study, the authors found that Rch1 inhibited redox-dependent interaction between Trx1 and TBP-2. Therefore, Trx1 may function to regulate nuclear import of TBP-2 by Rch1 and the tumor-suppressive activity of TBP-2.

FIG. 7.

Inhibition of Trx1 functions by TBP-2. Trx1-binding protein (TBP)-2 (also called VDUP1 or TXNIP) binds to Trx1 and inhibits Trx1 functions in reduction of protein disulfides. Oxidative stress stimulates this binding and also stimulates accumulation of the complex in nuclei. The Trx1/TBP complex accumulated in the nucleus by oxidants inhibits Trx1 interaction with Ref1. This process inhibits Trx1 function for Ref1 reduction, which in turn affects Ref1 activity to maintain Cys residues of transcription factors for DNA binding and activation for gene expression required for cell growth and proliferation.

Other redox-dependent regulation of subcellular protein trafficking has been investigated. The SECIS (selenocysteine insertion sequence)-binding protein 2, named SBP2, shuttles between cytoplasm and nuclei through NLS and NES motifs. SBP2 regulates selenium incorporation into selenoproteins such as TrxR and Grx members by direct binding to SECIS elements (26). Compartmental trafficking of SBP2 from ribosome to nuclei and vice versa was regulated by NLS and NES, respectively (142). Nuclear accumulation of SBP2 was associated with concomitant decreases in selenoprotein expression levels. Oxidation of the SBP2 redox state resulted from direct Cys oxidation (142). In vitro studies showed that the oxidized form was efficiently reduced by Trx1, suggesting that SBP2 is a Trx1 substrate. In addition, glutathionylated SBP2 was formed during incubation with GSSG, and this formation was reversed by Grx1. However, because redox potentials of the in vitro experiments may not reflect in vivo conditions, it is not clear which of these mechanisms predominates in vivo. The decrease in oxidative modifications of SBP2 by Trx1 or Grx1 supports the idea that the nuclear Trx1 or GSH system plays a role in the nuclear export of SBP2. During cell recovery from oxidative stress, relocation to the ribosomes occurs as a result of reduction.

Redox regulation of the apurinic-apyrimidinic endonuclease 1/redox factor-1 (APE1/Ref-1) in DNA repair and tumorigenesis and neurodegerative diseases has been reported (43, 88, 189). APE1/Ref-1 is present predominantly in the nuclei, although its subcellular localization varies depending on cell types and stress. Nuclear localization of APE1/Ref-1 was dependent on NLS residing within this protein, and nuclear import was found to be mediated by importin (77). The modifications in critical Cys residues (Cys 93, Cys 310) in APE1/Ref-1 by nitrosative stress stimulated nuclear export of APE1/Ref-1 in a CRM1-independent manner, and this process was reversible (150). In addition, S-nitrosation of Cys 93 and Cys 310 suppressed importin-mediated nuclear import of APE1/Ref-1. This NO-stimulated, NO-dependent reaction further supports a critical role of a redox-controlled subcellular trafficking mechanism.

Depletion of glucose/glutamine (Glc/Gln) from cell-culture medium resulted in oxidation of the NADPH/NADP+ and resulted in redox regulation of Ref-1. Total Ref-1 contents in cytosol and nuclear fractions were unaffected by this treatment for 24 h, suggesting that nuclear import of Ref-1 did not occur in response to Glc/Gln depletion. However, quantification of the amount of reduced Ref-1 in each compartment showed that Ref-1 is more reduced in nuclei than in cytoplasm after Glc and Gln depletion. These results show that mechanisms are available to maintain the Ref-1 redox state in the nuclei during oxidative stress (50). Such protection can occur as a consequence of Trx1 translocation to nuclei or of variation in the content or activity of TBP-2, as indicated earlier.

Redox-dependent Regulation in Nuclei

Most nuclear proteins contain cysteine residues that are subject to oxidation during oxidative stress, and considerable evidence shows that GSH and Trx1 systems function in the protection of these Cys, either by elimination of oxidants or by reduction of oxidized residues. Such processes have been studied most extensively in terms of proliferative and growth-promoting effects in cancer and the in resistance of cancer cells to therapy (45, 113, 141, 146, 202, 204). More direct evidence for redox functions in regulation is provided by studies of transcription factors that contain a conserved Cys in the DNA-binding region. This research provides clear support for the interpretation that the thiol antioxidant systems serve to regulate signaling mechanisms in addition to providing the protective and repair functions. Furthermore, recent evidence shows that ROS generation occurs as a consequence of DNA damage, suggesting that nuclear generation of oxidants may also function in signaling. Redox-dependent transcriptional regulation, oxidative DNA damage and repair, and redox mechanisms in control of cell growth and proliferation have been extensively reviewed, so the current overview is intended to highlight some of the important redox-dependent characteristics.

Redox-sensitive transcriptional regulation

Modulation of DNA binding by redox-dependent transcription factors control expression of a wide range of genes in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. These redox-dependent transcription factors including NF-κB, p53, AP-1, Nrf2, HIF, glucocorticoid receptor, estrogen receptor, and others. Each has a critical thiol moiety in a cysteine residue, which is controlled by the redox status of the nucleus and plays an important role in the transcriptional activity. For instance, the Cys 62 residue of the p50 subunit within the p50/p65 heterodimer plays a crucial role for the NF-κB activation and inactivation. The Cys 62 residue must be reduced for the p50 subunit to facilitate DNA binding; thus, the redox state of the nuclear compartment is critical for NF-κB activation (37). Both the Trx1 system (69) and the GSH system (161) modulate NF-κB transcriptional activity through Cys 62 of p50 subunit. The transcriptional activation was elevated by Trx1 overexpression, whereas mutations in active site C32 and C35 of Trx1 had significant inhibitory effect on NF-κB activation. In contrast, mutations in nonactive site Cys residues (Cys 62, 69, 73) of Trx1 did not have an effect on NF-κB binding to DNA and transcriptional activation.

The sensitivity of transcription factors to oxidant-induced inhibition was first recognized in studies of AP-1. AP-1 is activated by low levels of oxidative stress, but increased oxidative stress caused inhibition. In studies of the mechanism, a hepatic nuclear protein, identified as redox factor-1 (Ref-1) (201) was recognized to reduce c-Fos and c-Jun members of AP-1 (1). This redox modulation occurred at a conserved Cys residue (Lys-Cys-Arg) present in both c-Fos and c-Jun. Reductions of c-Fos and c-Jun by Ref-1 stimulated AP-1 DNA binding, and this stimulatory effect by nuclear protein was significantly elevated by reduced Trx1 (1). Numerous other studies show that AP-1 activation is redox dependent, regulated by the Trx1 system, including Ref-1 and TrxR, and also by the GSH system (87, 95, 197). DNA binding of AP-1 was shown to be inhibited by oxidized Trx1 and GSSG (45), and transcriptional activation was also shown to be regulated by the redox state of GSH/GSSG (95).

The p53 transcription factor controls the expression of a wide range of genes in response to DNA damage, chemotherapeutic drugs, growth factors, and oxidants (76). The p53 resembles other redox-dependent transcription factors, NF-κB and AP-1, in its susceptibility to redox regulation (155, 180). The p53 consists of three major domains, including a transactivation domain, a DNA-binding domain, and a tetramerization domain. Ten Cys residues are located within the DNA-binding domain of p53, and all are susceptible to oxidation, resulting in alteration of DNA-binding properties. The p53 forms a disulfide bond under mild oxidizing conditions by cis-diaminedichloroplatinum (II), and disulfide bond formation correlates with inhibition of the transcriptional activity of p53 (180). Trx1 enhances p53 DNA-binding activity directly or through Ref-1 mediation (186), whereas dominant-negative Trx1 inhibited p53 DNA-binding activity (156). It has been suggested that a protective role for the nuclear Trx1 in cisplatin-induced apoptosis is perhaps mediated by p53-dependent mechanism (17).

Evidence for the regulation of the DNA-binding function of p53 by GSH/GSSG has also been shown (190). Several Cys residues in the proximal DNA-binding domain are responsible for glutathionylation and have been suggested to regulate the structural dynamics of the DNA-binding domain. Increased glutathionylation of p53 was observed at a lower GSH/GSSG ratio, and its increase was associated with inhibition of DNA-binding function (190). In addition, increased glutathionylation of nuclear p53 was observed with diamide-treated cells, leading to reduction of DNA-binding ability. However, it has not been identified which of the 10 Cys residues in p53 are most reactive in regulation, and the functional consequences of alterations in each of the Cys residues remains unclear. Further investigations of biochemical mechanisms that affect the p53 functions during cellular stress are necessary to provide insight into the roles of these modifications in tumor biology and anticancer therapy.

NF-E2–related factor-2 (Nrf-2) is another redox-sensitive transcription factor that is implicated in cellular responses to oxidative stress. Nrf-2 regulates numerous genes through the antioxidant response element (ARE) as a heterodimer with a small Maf protein (126). Several important antioxidant genes are regulated, including Trx1 (92), glutathione synthesis enzymes (118, 199), GPx, GR (101), GSTs (163), and heme oxygenase-1 (75). Nrf-2 is normally sequestered in the cytoplasm by an inhibitor molecule, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap-1). Oxidative stress stimulates Nrf-2 release and translocation to the nucleus (127). Similar to other redox-sensitive transcription factors, NF-κB, AP-1, and p53, a critical Cys residue (Cys 506), must be reduced in the nuclei for DNA binding (9). Nrf-2 function is controlled by the dissociation of the Nrf-2/Keap-1 complex. The Cys residues in Keap-1 (Cys 257, 273, 288, and 297) have a crucial role in the dissociation of this complex (30, 127). Compartment-specific Nrf-2 redox control has been shown with oxidative activation in the cytoplasm and oxidative inactivation in the nucleus (61). The data showed that oxidant-induced Nrf-2/Keap-1 dissociation in the cytoplasm was regulated by the GSH system, whereas the DNA-binding activity of Nrf-2 in the nucleus was controlled by nuclear Trx1 (61).

Redox sensitivity of ribonucleotide reductase and DNA damage/repair

Ribonucleotide reductase

Early studies of deoxyribonucleotide synthesis in Escherichia coli led to the discovery of Trx and Grx (131), and related research continues to be an important subject in DNA repair and cancer biology. Ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) catalyzes de novo synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides by reducing the corresponding ribonucleotides for DNA synthesis and repair (131). Mammalian RNR consists of a large R1 subunit containing the substrate-binding site, redox-active Cys residues and a small R2 subunit harboring a tyrosine free radical, which is important in catalysis (97). The RNR activity is cell cycle–dependent in mammalian cells (8). Proliferating cells require a large amount of deoxyribonucleotide during the S phase of the cell cycle. The R2 protein level is low in the G1 phase, but increases to the maximum level during the S phase. Conversely, the R1 protein level remains high and constant throughout the cell cycle. Thus, cell cycle–dependent RNR activity appears to be modulated by the R2 synthesis and degradation. More recently, the p53-dependent RNR small subunit (p53R2), a homologue of R2, was discovered and found to play a pivotal role in the p53-dependent cellular response to DNA damage (54, 184). The p53R2 induced in DNA-damaged cells also forms the RNR complex with the R1 subunit as a partner protein and supplies deoxyribonucleotides for DNA repair (54).

Because the reduction of ribonucleotides is a fundamental initial metabolic step for DNA synthesis, RNR has been considered an important target for cell-growth control and anticancer therapy. For instance, several RNR inhibitors have been used as chemotherapy agents (64, 97). More recent studies show the inhibitory regulation of p53R2 on the MAP kinase signaling pathway. This finding suggests a suppressive role of p53R2 in oncogenicity but also provides a new strategy for inhibiting tumor development (145).

The redox control of RNR in DNA repair is dependent on the Trx1 and GSH systems (3, 122, 160). Each enzymatic cycle results in oxidized RNR, with a disulfide in the C-terminal site of the R1 subunit. Trx1 in the Trx system and Grx1 in the GSH system reduce the oxidized RNR by donating electrons ultimately from NADPH. The study from Avval et al. (3) suggests that the redox control mechanisms of the Trx1 and GSH systems for the RNR reduction are different. Although Trx1 and Grx1 have similar catalytic efficiency in reduction of the C-terminal disulfide in RNR, these reductases appear to favor conditions depending on the levels of RNR (3). Additional in vivo research shows that mice deficient in GSH metabolism accumulate DNA damage in the organs. This finding indicates that GSH plays a critical role in DNA repair through RNR (160). Redox-dependent control of cell cycle also was found to be regulated by the Trx1 redox state. Oxidation of Trx1 under hypoxia decreased RNR activity and caused cell-cycle arrest, suggesting a key role of Trx1 in control of the cellular redox state without the involvement of ROS (122).

DNA damage and repair

DNA is susceptible to oxidative damage caused by ionizing radiation, environmental mutagenesis, and carcinogens. An increasing body of evidence indicates that significant damage to DNA contributes to the pathology of cancer, atherosclerosis, and neurodegenerative diseases (114, 194, 205). Most studies addressing thiol/disulfide systems in DNA damage and repair have focused on protection against reactive species and have not distinguished whether separate redox signaling and control events also function in regulation of the repair machinery. However, several studies show that redox-dependent mechanisms function in controlling the transcription of DNA-repair machinery (40).

A wide range of products are generated during oxidative DNA damage, such as sugar and base modifications and covalent crosslinks with single- and double-stranded breaks. In terms of oxidative damage to DNA, damage to bases and to the phosphodiester backbone are known to be the major causes. One of the most extensively investigated adducts from modifications to DNA bases is 8-oxo-2'-deoxy-guanosine (8-oxodG), an oxidative base lesion resulting in mismatches in the DNA strands (109, 114, 123, 134). Because it was hypothesized that age-related oxidative stress resulted from the loss of the physiologic repair function to the irreversible, oxidative damage in macromolecules and the accumulation of altered macromolecules, such as modified DNAs, a significant number of studies on 8-oxodG in aging also have been performed. Substantial debate about actual in vivo levels of 8-oxodG in DNA have occurred because an artificial increase in 8-oxodG can occur during subcellular fractionation and isolation. However, with extensive precautions in analysis, 8-oxodG levels are still observed to increase with aging in rat and mouse aging models (58). The 8-oxodG accumulates in both the nuclear and the mitochondrial DNA (58, 123, 134). Accumulation of 8-oxodG stimulates mutagenesis by pairing with adenine as well as cytosine (110). A recent study by Oka et al. (134) demonstrated that oxidative stress with menadione treatment stimulated 8-oxodG accumulation in both nuclei and mitochondria. They also identified distinct cell-death mechanisms associated with 8-oxodG in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. The 8-oxodG in nuclear DNA caused poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PPAR)-dependent translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor to nuclei, whereas that in mitochondrial DNA caused mitochondrial dysfunction by Ca2+ release and subsequent activation of calpain (134).

Indirect evidence for redox signaling in DNA repair comes from studies showing that reactive oxygen species are generated in response to DNA damage. The study by Salmon et al. (166) to determine the cellular effects of induced, oxidative DNA damage shows a relation between specific oxidative DNA damage levels and biologic consequences of DNA damage levels. They found that DNA damage and intracellular ROS levels are elevated under normal growth conditions (no exposure to exogenous oxidant) in cells deficient in repair enzymes, relative to that in the wild type. Also, cells with elevated levels of DNA damage and ROS exhibit altered abilities to resist exogenous oxidative stress. These findings suggest that the presence of DNA damage alone is sufficient to increase cellular ROS levels and provide insights into the contribution of increasing genetic instability to tumor progression and resistance to chemotherapeutic agents.

Oxidative stress to DNA damage leading to structural changes may be associated with subsequent repair of the lesion. The repair systems include base-excision repair (BER), nucleotide-excision repair (NER), and mismatch repair (109). The majority of adducts of DNA damage are repaired by BER. BER involves several types of DNA glycosylases, including thymine glycol DNA glycosylase, hydroxyl methyl uracil glycosylase, and 8-oxodG glycosylase (25, 63). In humans, hOgg1 and hOgg2, identified as 8-oxodG glycosylases, have a specificity for 8-oxodG in template DNA and misincorporated opposite C and G or A, respectively (66). The hMYH, a human homologue of the E. coli MUTY repair protein, excises A paired with 8-oxodG in template DNA (175). These three enzymes play a key role in BER-dependent suppression of spontaneous mutagenesis induced by oxidative DNA damage. Conversely, the NER-mediated repair of 8-oxodG results in the excision of a lesion-containing oligomer, 24 to 29 nucleotides in length, followed by subsequent reduction to 6- to 7-mers (44). GSH and Trx1 systems can protect against introduction of damage and also regulate expression of DNA-repair genes or modify activity of proteins by glutathionylation (103).

Several repair enzymes were upregulated under oxidative stress by atherosclerosis, providing evidence of DNA damage as a useful biomarker in atherosclerosis (114). These included enzymes regulating the BER system, Ref-1, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, and proteins involved in nonspecific repair, p53 and DNA-dependent protein kinase. Urinary 8-oxodG amounts measured from patients with hypertension was correlated with the GSH/GSSG ratio and GSH and GSSG concentration, suggesting that detection of DNA damage could be a useful aspect in the oxidative stress–related diseases (32).

Because oxidative modifications of DNA bases in the nuclei and mitochondria have been suggested as a mechanism of aging and age-related diseases, studies have been performed to evaluate whether a moderate level of regular exercise could be beneficial to age-induced oxidative DNA damage. Results show that swimming and treadmill running attenuate the usual oxidative DNA modifications that are associated with aging, supporting a beneficial role of a moderate level of regular exercise in oxidative DNA damage (123, 152, 153). Moreover, investigation of the effect of a calorie-restricted diet on age-associated DNA damage by examining level of 8-oxodG in aged rodents showed that dietary restriction significantly prevented age-related increase in mitochondrial 8-oxodG, whereas it had little effect on nuclear 8-oxodG in liver and kidney. These results imply that dietary restriction had much greater effect on mitochondrial DNA damage than on nuclear DNA damage (58). The mitochondrial Trx2 system is much more sensitive to oxidation than the nuclear Trx1 system (18), but it is not known whether this difference contributes to the differences in DNA damage. Additional studies are needed to examine the dietary-restricted effect on other tissues, such as heart and brain of aged rodents, other than liver and kidney.

DNA replication, cell proliferation, chromatin remodeling, and other redox-dependent nuclear functions

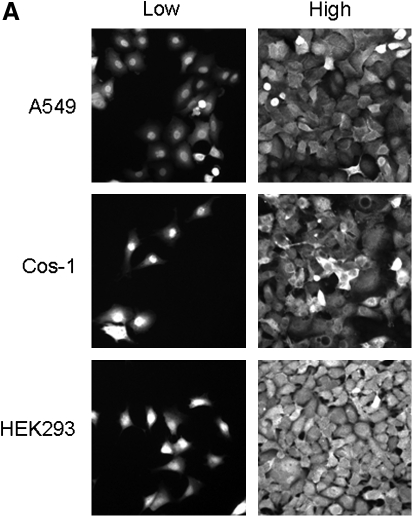

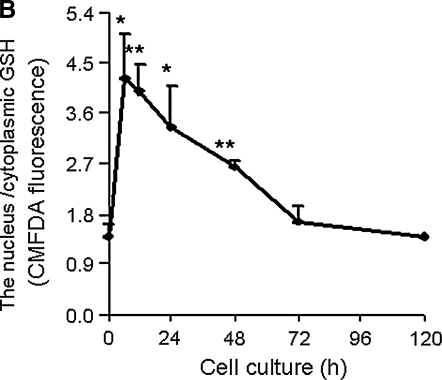

An extensive literature links the abundance and activity of GSH and Trx1-dependent redox systems to increased cell proliferation (45, 113, 130, 141, 204). A strong likelihood exists that nuclei-specific redox regulation is associated with these processes, just as such compartmentalization is recognized in transcriptional regulation. Such regulation is suggested by the redox dependence of the ribonucleotide reductase system. A number of studies show that GSH concentration is increased in rapidly proliferating cells and that decreased GSH limits cell proliferation. The data suggest that an increase in GSH occurs in nuclei of proliferating cells (Fig. 8) (113, 141, 177). This, in addition to the numerous studies showing elevated Trx1 in highly proliferative cancer cells and preferential localization of Trx1 in nuclei of highly proliferative cells (Fig 8), indicates that a highly reducing nuclear environment is critical for proliferation. At present, however, these data must be viewed as circumstantial evidence that a more reduced nuclear redox state occurs in the cell cycle. This subject is of considerable interest for cancer therapy targeting Trx1 and GSH systems (146, 202), and additional studies are needed to address this important subject.

FIG. 8.

Nuclear localization of Trx1 and glutathione is associated with cell proliferation. (A) Low cell-culture density, which is associated with oxidation of thiols and increased cell proliferation, affects the localization of Trx1 in cells. Each cell line (A549, Cos-1, HEK293) was plated in six-well plates containing glass coverslips at low and high density, incubated for 2 days, and assayed for Trx1 localization with immunofluorescence microscopy by using the Trx1 antibody. Data are reproduced from reference (177) with permission. (B) The nucleus/cytoplasm-to-GSH ratio, quantified with CMFDA fluorescence, shows higher levels in proliferating cells than in confluence, suggesting that a reduced nuclear environment is required for cell growth. Data are redrawn from reference (113).

Redox regulation of histone deacetylases, known as sirtuins, has been linked to aging and longevity. This regulation involves NADH/NAD+ redox changes and is not known to be dependent on thiols. However, the processes functioning in chromatin structure and remodeling are very complex, and changes in cellular GSH/GSSG redox potential are known to occur in association with cell differentiation (94). Thus, a possibility exists that specific nuclear redox systems also have a role in regulation of chromatin structure and function. The critical roles of these processes in development and aging therefore warrant investigation of these possibilities.

Summary and Perspectives

Recent changes in the definition of oxidative stress have placed additional focus on the disruption of redox signaling and control as important subjects of investigation. Recognition that nonradical oxidants are quantitatively important in oxidative stress further emphasizes that thiol systems are central targets of injury. Methods are now available to examine specific thiols in cell nuclei, and available data indicate that the central GSH and Trx1 systems are more reduced than those in the cytoplasm and are also more resistant to exogenous oxidants. Despite the relative resistance of nuclear proteins to oxidation, the sensitivity to oxidation of transcription factor binding to DNA suggests that redox mechanisms are involved in a dynamic regulation of function. Additional research using newly developed methods to study nuclear protein oxidation and redox control pathways will aid in understanding complex regulatory events in the cell nucleus and can provide the basis for new therapeutic approaches targeting these critical redox-sensitive processes.

Abbreviations Used

- 8-oxodG

8-oxo-2'-deoxy-guanosine

- APE1

apurinic-apyrimidinic endonuclease 1

- BER

base excision repair

- Cys

cysteine

- DAO

d-amino acid oxidase

- Eh

redox potential

- Glc

glucose

- Gln

glutamine

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- GR

GSSG reductase

- Grx

glutaredoxin

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione disulfide

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- NER

nucleotide-excision repair

- NES

nuclear-export signal

- NLS

nuclear-localization signal

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NF-E2)-related factor 2

- PrSH

protein thiol

- Pr-SSG

S-glutathionylated protein

- Prx

peroxiredoxin

- Ref-1

redox factor-1

- RNR

ribonucleotide reductase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SBP2

selenocysteine insertion sequence–binding protein 2

- TBP-2

thioredoxin-binding protein-2

- Trx

thioredoxin

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

Acknowledgment

Research on nuclear redox signaling and control in the investigators' laboratory is supported by NIH grant ES011195.

References

- 1.Abate C. Patel L. Rauscher FJ., 3rd Curran T. Redox regulation of fos and jun DNA-binding activity in vitro. Science. 1990;249:1157–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.2118682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali-Osman F. Brunner JM. Kutluk TM. Hess K. Prognostic significance of glutathione S-transferase pi expression and subcellular localization in human gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:2253–2261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avval FZ. Holmgren A. Molecular mechanisms of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin as hydrogen donors for mammalian S phase ribonucleotide reductase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8233–8240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809338200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]