Abstract

Motivation: In Systems Biology, an increasing collection of models of various biological processes is currently developed and made available in publicly accessible repositories, such as biomodels.net for instance, through common exchange formats such as SBML. To date, however, there is no general method to relate different models to each other by abstraction or reduction relationships, and this task is left to the modeler for re-using and coupling models. In mathematical biology, model reduction techniques have been studied for a long time, mainly in the case where a model exhibits different time scales, or different spatial phases, which can be analyzed separately. These techniques are however far too restrictive to be applied on a large scale in systems biology, and do not take into account abstractions other than time or phase decompositions. Our purpose here is to propose a general computational method for relating models together, by considering primarily the structure of the interactions and abstracting from their dynamics in a first step.

Results: We present a graph-theoretic formalism with node merge and delete operations, in which model reductions can be studied as graph matching problems. From this setting, we derive an algorithm for deciding whether there exists a reduction from one model to another, and evaluate it on the computation of the reduction relations between all SBML models of the biomodels.net repository. In particular, in the case of the numerous models of MAPK signalling, and of the circadian clock, biologically meaningful mappings between models of each class are automatically inferred from the structure of the interactions. We conclude on the generality of our graphical method, on its limits with respect to the representation of the structure of the interactions in SBML, and on some perspectives for dealing with the dynamics.

Availability: The algorithms described in this article are implemented in the open-source software modeling platform BIOCHAM available at http://contraintes.inria.fr/biocham The models used in the experiments are available from http://www.biomodels.net/

Contact: francois.fages@inria.fr

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Systems biology models

Biologists use diagrams to represent interactions between molecular species. On the computer, diagrammatic notations like the Systems Biology Graphical Notation (SBGN; le Novere et al., 2009) or the one introduced in Kohn's map (Kohn, 1999) of the cell cycle are also employed in interactive maps like MIM (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/mim/) (Kohn et al., 2006) for instance. This kind of graphical notation encompasses two types of information: interactions (binding, complexation, protein modification, etc.) and regulations (of an interaction or of a transcription). Based on these structures, mathematical models are developed by equipping such molecular interaction networks with kinetic expressions leading to quantitative models of mainly two kinds: ordinary differential equations and continuous-time Markov chains for a stochastic interpretation of the kinetics.

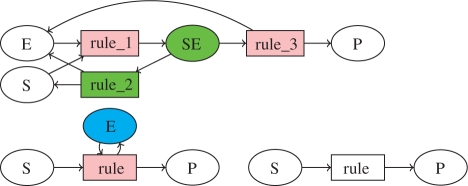

The Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML; Hucka et al., 2003) uses a syntax of reaction rules with kinetic expressions to define such reaction models in a precise way. For instance, the Michaelis–Menten enzymatic reaction, in which an enzyme E transforms a substrate S to a product P, can be described either with a system of three reaction rules (equipped with mass action law kinetics) showing the formation of the intermediary complex SE as follows: S + E <=> SE => P + E, or with a single reaction rule (equipped with a Michaelis–Menten kinetics) in which the catalyst enzyme is supposed to be constant: S + E => P + E, and can also be omitted as in: S => P. These three models are represented by the bipartite graphs depicted in Figure 1, and correspond to different levels of detail for the same reaction. This is one trivial example, among others, of reduction that can be performed in large models and that we would like to identify automatically.

Fig. 1.

Reaction graphs of the Michaelis–Menten enzymatic reaction, either complete with intermediary complex SE, or reduced with or without enzyme E. The first reduction can be achieved with the graphical operations explained in Section 2.2, for example by merging the reaction nodes rule_1 and rule_3 in pink into a reaction node rule and by deleting the green nodes SE and rule_2. The second reduction simply deletes the blue node E.

Nowadays, an increasing collection of models of various biological processes is indeed developed and made available to anyone in the SBML format. For instance, the publicly-accessible repository biomodels.net (le Novère et al., 2006) is currently composed of 241 curated models. These different models may represent either different biological systems, or the same biological process at different levels of details or under different biological assumptions. Some represent transient directional biological processes (like signal transduction cascades), while some others represent recurrent oscillating behaviors (like circadian clock core genes or cell cycle control). Some models are pretty big (about 400 nodes, which is quite a lot for a hand-written biological model), while some others are very small (less than 10 nodes). Some models are only structural and contain only qualitative information (e.g. known protein interactions, or phenomenological events) while some others add precise quantitative data (with experiment-based kinetic rates). In some cases, the structure of the reactions is reverse-engineered from an ordinary differential equation (ODE) model and may not reflect all information, such as for instance the effect of inhibitors which cannot be distinguished from the catalysts in the syntax of a reaction rule.

1.2 Model comparison as a graph matching problem

If modelling is the process that enables our understanding and predicting of the behaviour of a system, then model reduction makes our task easier. By removing what we consider as details, model reduction allows the understanding of the core of systems, and simulation of bigger-sized systems. In mathematical biology, model reduction techniques have been studied for a long time, mainly in the case where a model exhibits different time scales, or different spatial phases, which can be analyzed separately. For instance, in the previous example of the Michaelis–Menten enzymatic reaction, the hypotheses that the substrate is in excess and the complex formation is much faster than the other reactions justify the elimination of the intermediary reactions. The mathematical conditions for quasi-steady state approximations (Segel, 1984) or total quasi-steady state approximations (Ciliberto et al., 2007) are however far too restrictive to be applied to Systems Biology models on a large scale, and do not take into account other abstractions than time or phase decompositions.

Our applicative purpose here is to propose a general computational method for relating models together, by considering primarily the structure of the interactions and abstracting from their dynamics and even the stoichiometry in a first step. Given two reaction graphs, the model reduction problem is to determine whether one is a reduction of the other. This model comparison focusses on the notion of model refinement that often occurs in the life-cycle of published biological models. Indeed, every biological model is ‘false’ at some point and can be refined to encompass more details. The modellers usually describe these refinements through two basic operations: adding new species or reactions that were unknown or considered secondary, or splitting existing species or reactions into several ones, in order to give more details (about the levels of phosphorylation of a given molecule, or about the specific mechanistic process that underlies some reaction for instance).

Graph-matching techniques have already been used for biological networks, but it is worth noticing that they have mostly been applied to either protein-interaction graphs, see for instance (Chin et al., 2008), or regulation graphs, see for instance (Naldi et al., 2009) for a dynamics-preserving graph reduction. On reaction graphs, graph-based techniques have been considered in Calzone et al. (2008), Radulescu et al. (2006) and Zinovyev et al. (2008) for modularization issues in large models. In this article, we study a restricted notion of subgraph epimorphism, corresponding to the application of node delete and merge operations in a reaction graph, in order to relate a source graph to a target graph through a model reduction relation.

In the next section, we present the graph-theoretic framework of model reduction by graph matching, and its formal relationship to delete and merge operations on reaction graphs. In Section 3, we describe our algorithm for solving this particular kind of graph matching problems and its implementation with a constraint program written in GNU-Prolog. Then, in Section 4, we present the graphs extracted from the biomodels repository for the evaluation, and in Section 5, we report on the performance of our algorithm and on the biological significance of the matchings found automatically in this repository. We conclude on the generality of our graphical method for model comparison, on its limits with respect to the representation of the structure of the interactions in SBML, and on some perspectives for dealing with the dynamics.

2 GRAPH MATCHING METHOD

2.1 Reaction graphs

Formally, a reaction graph G is a bipartite directed graph, that is a triple G = (S, R, A), where S is the set of species nodes, R is the set of reaction nodes, and A ⊆ S × R ∪ R × S the set of arcs that describes how species interact through reactions.

There is an arc (s, r) (resp. (r, s)) if s is a reactant (resp. product) of r. Both arcs are present if s is a catalyst of r or more generally if it affects the reaction rate of r. It is worth noting that reaction graphs do not precisely model stoichiometry (hypergraphs would be needed for that) nor kinetics, but describe the structure of the interactions.

2.2 Merge and delete operations

One way to relate two models is to define graph-editing operations which make it possible to transform one reaction graph into another. A simple thing to do when trying to reduce models is to consider that two species are variants and treat them as equivalents, and to merge every interaction any of the two species had into a new species. The reaction graph formalism has a symmetry between species and reactions, so the merging process can be generalized to reactions as well, and this will prove useful.

Another natural operation is node deletion. It may be useful for instance to remove intermediate species, or species whose concentration is constant, or reactions that have become trivial after a molecular merging, or reverse reactions that occur in a much slower rate than their forward counterpart. Model refinement proceeds with the dual operations of node addition and splitting and is thus also covered by this approach.

Let us assume that (G = (S, R, A)) is a reaction graph.

Definition 2.1 —

(Pre/Post arcs). Let (v ∈ S ∪ R), the set of pre-arcs (resp. post-arcs) of v is the set •v = {a∈A∣∃w ∈ S ∪ R, a = (w, v)}) (resp. v• = {a∈A∣∃w∈ S ∪ R, a = (v, w)}).

This notion extends to subsets of nodes pointwise: for V ⊆ S or V ⊆ R we note

and

.

The delete operation removes a node from a reaction graph with all its pre- and post-arcs:

Definition 2.2 —

(Delete). Let v ∈ S (resp. R), the result of the deletion of v in G is the reaction graph dv(G) = (S′, R, A′) (resp. (S, R′, A′)) where

We can now define the merge operation that intuitively removes two vertices (either two species or two reactions) from a reaction graph and replaces them with a new one inheriting all the dangling arcs. See Figure 1 for the example of the Michaelis–Menten reduction.

Definition 2.3 —

(Merge). For all v, w ∈ S (resp. R), we define mv,w(G) as the reaction graph (S′, R, A′) (resp. (S, R′, A′)) where

It is worth noting that these operations delete and merge for molecules and reactions can be implemented in a graphical editor for reaction rules as a mean to define model reductions, and automatically derive reduced models from simple graph editing functions. This is the case in the BIOCHAM modeling platform (Calzone et al., 2006; Fages and Soliman, 2008) which now integrates novel features for editing, as well as detecting, model reductions.

2.3 Subgraph epimorphisms

Definition 2.4. —

Let G = (S, R, A) and G′ = (S′, R′, A′) be two reaction graphs. A morphism from G to G′ is a function μ from the nodes of G, S ∪ R, to the nodes of G′, S′ ∪ R′, with μ(S) ⊆ S′ and μ(R) ⊆ R′, such that ∀(x, y) ∈ A, (μ(x), μ(y)) ∈ A′.

An epimorphism from G to G′ is a morphism that is surjective on (both the nodes and the arcs of) G′. An isomorphism from G to G′ is a morphism that is bijective on (both the nodes and the arcs of) G′.

Notice that if there are epimorphisms from G to G′ and from G′ to G, then there is an isomorphism from G to G′.

As shown below, graph epimorphisms relate graphs that can be obtained by merge operations. To account for node deletions, we consider:

Definition 2.5. —

Let G = (S, R, A) and G′ = (S′, R′, A′) be two reaction graphs. A subgraph morphism μ from G to G′ is a morphism from a subgraph induced by a subset of nodes of G, to G′: S0 ∪ R0 → S′ ∪ R′, μ(S0) ⊆ S′, μ(R0) ⊆ R′, with S0 ⊆ S and R0 ⊆ R, such that ∀(x, y) ∈ A ∩ (S0 × R0 ∪ R0 × S0), (μ(x), μ(y)) ∈ A′.

A subgraph epimorphism from G to G′ is a subgraph morphism that is surjective.

In order to show the link with the merge and delete operations, we need the following properties:

Lemma 2.6 —

(Commutativity). Let G = (S, R, A) be a reaction graph and (u, v) ∈ S2 ∪ R2. G1 = mu,v(G) and G2 = mv,u(G) are isomorphic, i.e. there exists a bijective morphism from G1 to G2 (or from G2 to G1).

Proof. —

From Definition 2.3, it is clear that the only difference between G1 and G2 lies in the name of the new vertex uv or vu. The function mapping all the other vertices to themselves and uv to vu is thus a morphism from G1 to G2, and it is bijective.

Lemma 2.7 —

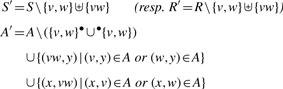

(Associativity). Let G = (S, R, A) be a reaction graph and (u, v, w) ∈ S3 ∪ R3. Then G1 = muv,w ○ mu,v(G) and G2 = mu,vw ○ mv,w(G) are isomorphic.

Proof. —

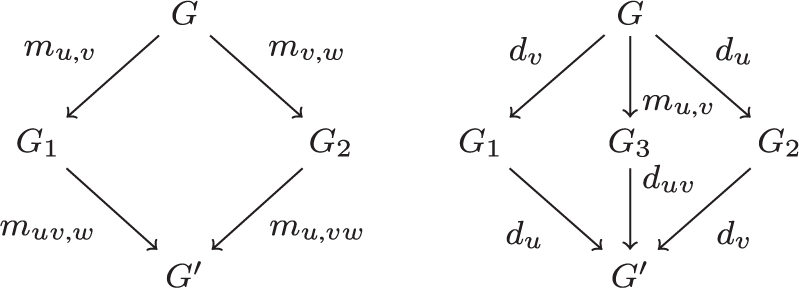

Once again it is obvious from Definition 2.3 that both graphs have the same vertices, up to renaming of (uv)w to u(vw) and that these two vertices have isomorphic pre- and post-arcs corresponding to the union of all pre- and post-arcs of u, v and w. Figure 2 illustrates this.

Fig. 2.

Associativity of the merge operation.

We will denote by mV the merge operation for all vertices of the set V. Notice that if V and V′ are two disjoint subsets of vertices mV ○ mV′ = mV′ ○ mV. Furthermore, since dv ○ dw = dw ○ dv it also makes sense to write dV = ○v∈Vdv.

Theorem 2.8. —

Let G = (S, R, A) and G′ = (S′, R′, A′) be two reaction graphs. There exists an epimorphism μ from G to G′ if and only if there exists a finite sequence of merge operations, i.e. a finite sequence of pairs of vertices (vi, wi)i≤n, such that the graph mvn,wn ○…○ mv0,w0(G) is isomorphic to G′.

Proof. —

Let us prove by induction on n that if mvn,wn ○…○ mv0,w0(G) is isomorphic to G′ then there exists an epimorphism from G to G′.

The base case is obvious since the identity is an epimorphism.

Now, suppose that mvn,wn ○…○ mv0,w0(G) is isomorphic to G′, by induction hypothesis, there exists an epimorphism ν from G to G′′ = mvn−1,wn−1 ○…○ mv0,w0(G). Now consider ζ : x ↦ x if x ≠ vn and x ≠ wn and ζ(vn) = ζ(wn) = vw, ζ is an epimorphism from G′′ to mvn,wn(G′′), and thus μ = ζ ○ ν is an epimorphism from G to mvn,wn ○…○ mv0,w0(G) which is isomorphic to G′.

Conversely, suppose that μ is an epimorphism from G to G′. The set of preimages of μ partitions S and R in equivalence classes, let us write them Vi = μ−1(vi′) for vi′ ∈ S′ ∪ R′. Now consider G′′ = mV1 ○…○ mVk(G): it is isomorphic to G′. Indeed, for every i, the nodes x of Vi are merged into a single node v′′i of G′′, and no Vi is empty (μ is surjective). So the function κ : v′i → v′′i is well-defined. κ is surjective on the nodes, since every node in G′′ comes from the merging of a Vi, thus it is bijective on the nodes. Let (x′, y′) ∈ A′ Since μ is also arc-surjective, (x′, y′) has a preimage (x, y) ∈ A, which in turn has an image (v′′i, v′′j) in G′′. So κ is a morphism. A morphism which is node-bijective is an isomorphism, hence the conclusion.

Note that this proof can actually be rephrased as a proof that sequences of merges can be associated to equivalence classes on G and then as a corrolary of the first isomorphism theorem (or of the fundamental theorem on homomorphisms).

Theorem 2.9. —

Let G = (S, R, A) and G′ = (S′, R′, A′) be two reaction graphs. There exists a subgraph epimorphism μ from G to G′ if and only if there exists a finite sequence of delete and merge operations that, when applied to G, yield a graph isomorphic to G′.

Proof. —

Let us prove again the backward implication by induction on n.

The base case is still obvious since the identity is a subgraph epimorphism.

For the induction case, if the last operation is a merge, we obtain an epimorphism, which, composed with a subgraph epimorphism (induction hypothesis), leads to a subgraph epimorphism.

The only remaining case is when we have a subgraph epimorphism from G to G′′ and G′ isomorphic to dv(G′′). Consider S0 = S∖{v} and R0 = R∖{v}, the identity restricted to S0 and R0 defines a subgraph epimorphism from G′′ to dv(G′′), by composition we obtain a subgraph epimorphism from G to G′.

Conversely, suppose that μ is a subgraph epimorphism from G to G′. We define S0 = μ−1(S′), R0 = μ−1(R′), and writing S′ ∪ R′ = {v1,…, vn}, Vi = μ−1(vi). Now we consider G′′ = mV1 ○…○ mVk ○ dS∖S0 ○ dR∖R0: G′′ is isomorphic to G′ up to the renaming of the μ(Vi) by vi. Indeed, all the μ(Vi) are different since all the Vi are disjoint, for all (x, y)∈A∩(S0 × R0 ∪ R0 × S0) we get both an arc (μ(x), μ(y)) in A′ and an arc (vx, vy) in G′′. By definition, these are exactly the arcs of G′′, and by surjectivity of μ, it also covers every arc of G′. Hence the conclusion.

Notice that if G is mapped to G′ by a sequence of merge and delete operations, any sequence of merges and deletes yielding the same equivalence classes as the proof above leads to a G′′ isomorphic to G′

We have seen examples of permutations between merge operations and between delete operations, another example of transformation is that of permuting a delete with a merge, one actually removes the merge: duv ○ mu,v = d{u,v}

Here are commuting diagrams summing this up:

3 ALGORITHM AND IMPLEMENTATION

The subgraph isomorphism problem is a well-known NP-complete problem, which means that there does not exist an efficient algorithm for solving all problem instances in polynomial time, if we admit the conjecture P ≠ NP. Nevertheless, the practical instances of such problems may well be solved by efficient algorithms and it is the purpose of this section to describe an algorithm for our particular class of bipartite graph-matching problems. It is easy to see that our subgraph epimorphism problem is at least as hard as the graph isomorphism problem which is not known to be in P. However we do not know whether it is NP-complete.

The mathematical definition of subgraph epimorphisms given in the previous section can be encoded quite directly in an executable constraint program. Constraint programming is a declarative programming style which relies on two components: one modeling of the problem using elementary constraints over finite domain variables and one search procedure. Constraint programming has been applied with success to graph-matching problems in le Clément et al. (2009). For this work, we developed a GNU-prolog (Diaz, 2003) program dedicated to our particular subgraph epimorphism problems, using finite domain constraints and a simple search strategy for enumerating all solutions by backtracking.

Graph morphisms can be modeled quite naturally by introducing one variable per node of the source graph, with, as domain, one (integer) value per node of the target graph. A variable assignment thus represents a mapping from the source nodes to the target nodes. The morphism condition itself is written with fd_relation tabular constraints, which forces a tuple of variables to take its value in a list of tuples of integers.

The surjectivity property could be represented by the cardinality constraint fd_at_least_one of GNU-Prolog but a more efficient modeling was found by creating variables for target arcs with the set of source arcs as domain, and using the global constraint fd_all_different.

Then, the enumeration on the target arc variables enforces surjectivity. This enumeration is done before the enumeration of node variables that enforces the computation of a morphism.

4 DATA

The aim of our concept of subgraph epimorphism in bipartite graphs is to automatically relate and compare Systems Biology models in repositories like biomodels.net. We consider the latest version (26 January 2010) of biomodels.net which contains 241 curated models of various origins but all encoded in SBML. From the SBML format, it is possible to extract the reaction graph as follows:

create a vertex for each species;

create a vertex for each reaction;

add an arc from a species to a reaction if it is listed in its reactants or modifiers;

add an arc from a reaction to a species if it is listed in its products or modifiers.

A thematic clustering was done, using information available from the notes of the SBML model. We focus here on the most populated classes:

mitogen-activated protein kinase;

circadian clock;

calcium oscillations;

cell cycle.

For each class, all morphisms between pairs of models are tried.

5 RESULTS

In our algorithm, the set of all morphisms, or a proof of non-existence, are obtained by backtracking. In the experiments reported below, the computation time was limited with a timeout of 20 min but most of the problems were solved in <5 s on standard PC quadcore at 2.8 GHz.

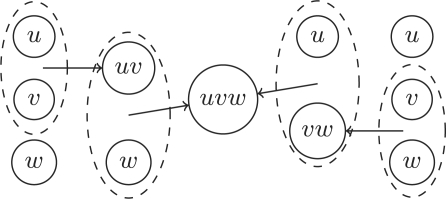

5.1 Mapk models

The matchings found between the models of the MAPK cascade are depicted in Figure 3. This class contains the family of models of Markevich et al. (2005) numbered 26–31. The reductions found automatically among these models are interesting for checking whether the formalism is faithful to biological reasoning, since the authors describe refinements between them. The models are of different sizes but always consider only one level of the traditional three levels of the MAPK cascade.

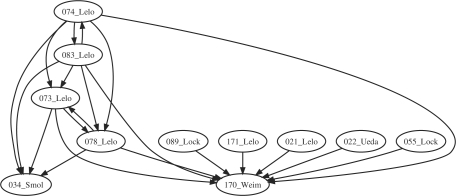

Fig. 3.

Matchings found between all models of the MAPK cascade (Schoeberl's model 14 and Levchenko's model with scaffold 19 are not represented here, they do not map each other but can be mapped to small models).

In this family, models 27, 29 and 31 are the simpler ones: they have few molecules because the catalyses are represented with only one reaction. The epimorphism exhibited from model 31 to 27 corresponds to the splitting of two variants of MAPKK in 31. Model 29 distinguishes between the sites of phosphorylation of Mp, yielding a model with two molecules MpY and MpT. The subgraph epimorphism found from 29 to 27 corresponds to the deletion of one variant of Mp. Conversely, this distinction prevents the existence of an epimorphism from 31 or 27 to 29.

Models 26, 28 and 30 have more detailed catalyze mechanisms and differ as previously by the phosphorylation sites of Mp.

However, some epimorphisms from big models to small ones may have no biological meaning. This comes from the absence of constraint on the nodes that can be merged, and the relatively high number of arcs in Markevich's small models where most molecules are catalysts. Still, model 26 (with non-differentiated Mp) does not reduce to model 29 since that model indeed distinguishes MpY and MpT variants.

Now, concerning three-step MAPK cascade models, the models 9 and 11 of (Huang and Ferrell, 1996) and (Levchenko et al., 2000) respectively are detected as isomorphic. Indeed, they only differ by molecule names and parameter values. They do not reduce to 28 and 30, which are models that do not differentiate sites of phosphorylation. They do not reduce to 26 either, which uses a more detailed mechanism for dephosphorilations.

Model 10 is another three-step MAPK with no catalysts for dephosphorilations. It has the particularity to be cyclic, that is, the last level's most phosphorylated molecule catalyzes the phosphorylations of the first level. This is shown here as a reduction of the previous models obtained by merging the output of the third level with the catalyst of the first level.

Finally, models 49 and 146 are bigger than the others and can easily be matched by them, and there were some comparisons for which no result was found before the timeout.

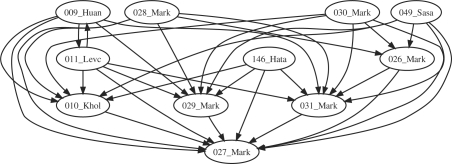

5.2 Circadian clock models

The matchings found in the class of circadian clock models are depicted in Figure 4. Models 16, 24, 25 and 36 being very small oscillators were matched by most of other models, and for that reason were left out from the picture.

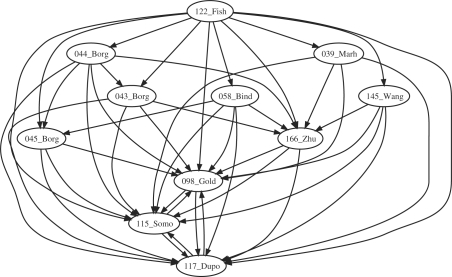

Fig. 4.

Matchings between the models of the circadian clock.

Let us first have a look at the isomorphisms found.

Models 73 and 78 are isomorphic. This is in accordance with the fact that these quite detailed models come from Leloup and Goldbeter (2003) and differ indeed by parameter values.

Models 74 and 83 are isomorphic too. They also correspond to two versions of a second model from the same article, but this time with the addition of the Rev-Erbα loop, greyed out in Figure 1 of Leloup and Goldbeter (2003). The authors explain ‘Taking into account explicitly the role of REV-ERBα in the indirect negative feedback exerted by BMAL1 on the expression of the Bmal1 gene requires an extension of the model, which is now governed by 19 instead of 16 kinetic equations’. The mapping to the previous models is automatically detected in accordance with these explanations, by merging the three new species (Rev-Erbα mRNA, protein in the cytoplasm and protein in the nucleus named Mr, Rc and Rn in model 74) to Bmal1 in the nucleus (named Bn in model 73).

Model 34 (Smolen et al., 2004) is a quite small model of the Drosophila's circadian clock. The fact that its structure is included in that of the mammalian clock of the above models is in accordance with the fact those models were built on top of knowledge from the Drosophila (Goldbeter, 1995) with a similar clock mechanism.

Models 171 (Leloup and Goldbeter, 1998) presents a model for the Drosophila, including Per/Tim (with two levels of phosphorylation) and the complex. Model 21 (Leloup and Goldbeter, 1999) actually studies the same model, unfortunately a different encoding in SBML (variable parameters instead of species for instance) makes it impossible to find a matching.

Many models map to model 170 (Becker-Weimann et al., 2004) which focusses on the positive feedback loop of the circadian cycle oscillator. It is quite small but has two compartments, which explains why only 34 cannot be reduced to it. Model 22 (Ueda et al., 2001) is a quite detailed model that focusses on the interlocked feedback loops, which can be mapped to 170 but not 34. Models 55 (Locke et al., 2005) and 89 (Locke et al., 2006) are both from Locke and others and about the circadian clock of Arabidopsis but include, in one case light induction, and in the other a new feedback loop. This explains why they do not give any matching either, except to the small oscillator model 170.

5.3 Calcium oscillation models

Figure 5 shows that many models of calcium oscillation are connected.

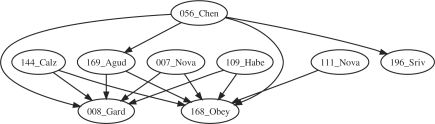

Fig. 5.

Subgraph epimorphisms for models of calcium oscillations from biomodels.net.

Models 98, 115 and 117 are in fact isomorphic due to their very small size (only two species) and differ only by their kinetics. There is a morphism from model 166 to them in accordance to the addition of a third species in this model where Ca2+ oscillations are seen as a mediator of genetic expression.

Models 43, 44 and 45 all relate to three different models from the same article (Borghans et al., 1997). Model 43 is the ‘basic one pool’ model and there is a match from 44, the ‘1-pool model with IP3 degradation’ since the latter is indeed a refinement of the former. The morphisms from 43 and 44 to 166 correctly exhibit the inclusion of the basic three-element oscillator in those models. A false positive morphism is found however from 44 to 45, the ‘2-pool model’. This morphism is purely formal and has no biological meaning. It could be eliminated by using annotations as further constraints, for instance by taking into account the references to UniProt/KEGG or ChEBI databases that are already present in some SBML models.

Model 122 (Fisher et al., 2006) is actually a big model of NFAT and NFκB with a side calcium oscillator. However, it includes many reversible reactions and thus structurally maps to all of the other models of this class.

Model 58 is a coupled oscillator version which interestingly maps to the ‘2-pool’ oscillator of Borghans et al. (1997) by merging some components of the two oscillators into one.

Finally, models 39, related to mitochondria, and 145, related to ATP-induced oscillations, only map the small oscillators already described.

5.4 Cell-cycle models

The reaction graphs of the cell cycle models are plagued by a common problem: these models originate from ODE models and the reaction graphs extracted from their encoding in SBML format does not correctly represent the structure of these models. It is thus hard to make sense of mappings between such graphs. For instance, the graphs of models 7, 8 and 56 are disconnected. Models 111, 144 and 196 have ghost molecules, that is, molecules which appear in the kinetics but not in the stoichiometry.

Nevertheless, models 144, 56 and 109 are relatively big with more than 50 reactions, and map easily on smaller models. Actually, there are 16 comparisons missing from this graph, and 13 are comparisons from these bigger graphs to the smaller ones.

Models 8, 168 and 196 are small (less than 15 reactions), which make them easy to match to, excepted for 196, which has a big diameter (Fig. 6). There is no matching from 111 to 8 however. This is explained by the erroneous structure of 8 which is disconnected.

Fig. 6.

SEPI for some models of the cell cycle.

5.5 Negative control

For the sake of completeness of the evaluation of our method, the reduction relations between all pairs of models of the biomodels.net repository have been computed (with a time out of 20 min per problem).

Some matchings between unrelated model classes were found. These false positive matchings typically arise with small models that formally appear as reductions of large models without any biological meaning, for the same reasons as in the cases discussed above within a same class. These false positives arise in less than 9% of the total inter-class pairs, and in 1.2% of the tests after the removal of the small models.

6 CONCLUSION

Constraint-based graph-matching algorithms have shown their effectiveness and efficiency to analyze and automatically relate biochemical reaction models on a large scale, namely among the 241 curated models of the systems biology repository biomodels.net. Of course, such an automatic correspondence between models inferred solely from the structure of the reaction graph may be biologically erroneous in some cases. In particular, small reaction graphs can be recognized as motifs of biologically unrelated large reaction graphs.

Nevertheless, the search for subgraph epimorphisms between all models of the biomodels.net repository revealed connected components roughly corresponding to the different models of similar biological systems for the MAPK signaling cascade, the circadian clock and the calcium oscillation models, automatically exhibiting morphisms, corresponding to model reductions, as well as isomorphisms, corresponding to variants of the same model with different parameter values.

On the other hand, the cell-cycle models of this repository often originate from ODE models that have been transcribed in SBML rules without correctly reflecting the structure of the interactions. As a result, many model reductions could not be detected as graph morphisms. More work is thus needed to curate the expression of these models in SBML, and also to restrict mappings by considering the information on molecular species present in the annotations, for instance.

Although necessarily imperfect, this approach opens a new way to query Systems Biology model repositories and study model reductions as subgraph epimorphism problems, before taking into account constraints on the stoichiometry and the dynamics of the reactions.

As a perspective for future work, the formal ground presented here in terms of graph operations and graph morphisms is currently used to investigate mathematical conditions under which the kinetics are compatible with graph reduction operations, such as for instance:

reaction deletions for slow reverse reactions,

reaction mergings for reaction chains with a limiting reaction,

molecular species deletions for species in excess,

molecular mergings for quasi-steady state approximations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge fruitful discussions with many participants of these projects and with Christine Solnon for an enlighting talk on graph matching at our seminar.

Funding: AE Regate; ANR Calamar (ANR-08-SYSC-003); ANR EraSysBio C5SYs; OSEO BioIntelligence projects.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Becker-Weimann S, et al. Modeling feedback loops of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3023–3034. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghans JM, et al. Complex intracellular calcium oscillations. A theoretical exploration of possible mechanisms. Biophy. Chem. 1997;66:25–41. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(97)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzone L, et al. BIOCHAM: an environment for modeling biological systems and formalizing experimental knowledge. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1805–1807. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzone L, et al. A comprehensive imodular map of molecular interactions in RB/E2F pathway. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4 doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin G, et al. Biographe: high-performance bionetwork analysis using the biological graph environment. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl. 6) doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S6-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberto A, et al. Modeling networks of coupled enzymatic reactions using the total quasi-steady state approximation. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2007;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz D. GNU Prolog User'S Manual. Available at http://www.gprolog.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Fages F, Soliman S. Formal cell biology in BIOCHAM. In: Bernardo M, et al., editors. 8th Int. School on Formal Methods for the Design of Computer, Communication and Software Systems: Computational Systems Biology SFM'08. Bertinoro, Italy: Springer; 2008. pp. 54–80. Vol. 5016 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WG, et al. Nfat and nfkappab activation in t lymphocytes: a model of differential activation of gene expression. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2006;34:1712–1728. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9179-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbeter A. A model for circadian oscillations in the drosophila period protein (per) Proc. Biol. Sci. Roy. Soc. 1995;261:319–324. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C-Y, Ferrell JE., Jr Ultrasensitivity in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:10078–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucka M, et al. The systems biology markup language (SBML): A medium for representation and exchange of biochemical network models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:524–531. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn KW. Molecular interaction map of the mammalian cell cycle control and DNA repair systems. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:2703–2734. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn KW, et al. Molecular interaction maps of bioregulatory networks: a general rubric for systems biology. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:1–13. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Clément V, et al. 15th International Conference on Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming (CP 2009) Lisbon, Portugal: Springer; 2009. Constraint-based graph matching; pp. 274–288. Vol. 5732 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science. [Google Scholar]

- Levchenko A, et al. Scaffold proteins may iphasically affect the levels of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and reduce its threshold properties. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5818–5823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Novère N, et al. BioModels Database: a free, centralized database of curated, published, quantitative kinetic models of biochemical and cellular systems. Nucleic Acid Res. 2006;1:D689–D691. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Novere N, et al. The systems biology graphical notation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:735–741. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leloup J-C, Goldbeter A. A model for circadian rhythms in drosophila incorporating the formation of a complex between the per and tim proteins. J. Biol. Rhythms. 1998;13:70–87. doi: 10.1177/074873098128999934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leloup J-C, Goldbeter A. Chaos and birhythmicity in a model for circadian oscillations of the per and tim proteins in drosophila. J. Theor. Biol. 1999;198:445–449. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1999.0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leloup J-C, Goldbeter A. Toward a detailed computational model for the mammalian circadian clock. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2003;100:7051–7056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1132112100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke JC, et al. Experimental validation of a predicted feedback loop in the multi-oscillator clock of arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke JC, et al. Extension of a genetic network model by iterative experimentation and mathematical analysis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2005;1 doi: 10.1038/msb4100018. msb4100018–E1–msb4100018–E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markevich NI, et al. Signaling switches and bistability arising from multisite phosphorylation in protein kinase cascades. J. Cell Biol. 2005;164:353–359. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldi A, et al. CMSB'09: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Computational Methods in Systems Biology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. A reduction method for logical regulatory graphs preserving essential dynamical properties; pp. 266–280. Vol. 5688 of Lecture Notes in BioInformatics. [Google Scholar]

- Radulescu O, et al. Hierarchies and modules in complex biological systems. In: Schuster P, editor. Proceedings of the Second European Conference on Complex Systems 2006 (ECCS 2006). 2006. Availabel at http://ecss.csregistry.org/ECCS%2706%20Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Segel LA. Modeling Dynamic Phenomena in Molecular and Cellular Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Smolen P, et al. Simulation of drosophila circadian oscillations, mutations, and light responses by a model with vri, pdp-1, and clk. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2786–2802. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda HR, et al. Robust oscillations within the interlocked feedback model of drosophila circadian rhythm. J. Theor. Biol. 2001;210:401–406. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinovyev A, et al. BiNoM: a cytoscape plugin for manipulating and analyzing biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:876–877. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]