Abstract

Motivation: Segmental duplications > 1 kb in length with ≥ 90% sequence identity between copies comprise nearly 5% of the human genome. They are frequently found in large, contiguous regions known as duplication blocks that can contain mosaic patterns of thousands of segmental duplications. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of these complex genomic regions is a non-trivial, but important task.

Results: We introduce parsimony and likelihood techniques to analyze the evolutionary relationships between duplication blocks. Both techniques rely on a generic model of duplication in which long, contiguous substrings are copied and reinserted over large physical distances, allowing for a duplication block to be constructed by aggregating substrings of other blocks. For the likelihood method, we give an efficient dynamic programming algorithm to compute the weighted ensemble of all duplication scenarios that account for the construction of a duplication block. Using this ensemble, we derive the probabilities of various duplication scenarios. We formalize the task of reconstructing the evolutionary history of segmental duplications as an optimization problem on the space of directed acyclic graphs. We use a simulated annealing heuristic to solve the problem for a set of segmental duplications in the human genome in both parsimony and likelihood settings.

Availability: Supplementary information is available at http://www.cs.brown.edu/people/braphael/supplements/.

Contact: clkahn@cs.brown.edu; braphael@cs.brown.edu.

1 INTRODUCTION

A striking feature of mammalian genomes is the prevalence of segmental duplications or low-copy repeats. Approximately 5% of the human genome consists of segmental duplications > 1 kb in length with ≥ 90% sequence identity between copies (Bailey and Eichler, 2006). Segmental duplications account for a significant fraction of the differences between humans and other primate genomes, and are enriched for genes that are differentially expressed between the species (Blekhman et al., 2009).

Segmental duplications remain an extreme challenge for evolutionary reconstruction, as they are the ‘most structurally complex and dynamic regions of the human genome’ (Alkan et al., 2009). Human segmental duplications are frequently found within complicated mosaics of duplicated fragments (Bailey and Eichler, 2006). Jiang et al. (2007) produced a comprehensive annotation of this mosaic organization; they derived an ‘alphabet’ of approximately 11 000 duplicated segments, or duplicons, and delimited 437 duplication blocks or ‘strings’ of at least 10 (and typically dozens) different duplicons found contiguously on a chromosome. However, the relationships between these annotated duplication blocks are complex and straightforward analysis does not immediately reveal the evolutionary relationships between blocks.

Numerous authors have considered the problem of analyzing relationships between genome sequences that contain duplicated segments. This work falls into roughly two categories. The first focus is the problem of computing genome rearrangement distances, like reversal distance, in the presence of duplicated genes or synteny blocks (El-Mabrouk, 2002; Marron et al., 2004; Sankoff, 1999, for example). However, such rearrangement distances do not model the creation of new duplicates and thus are not well-suited to describe the evolutionary history of segmental duplications in the genome. The second focus is to analyze regions with duplications under ‘local’ operations like tandem duplications (Chaudhuri et al., 2006; Lajoie et al., 2007, for example). While tandem duplication is undoubtedly important in the generation of duplication blocks, there is strong evidence that an important characteristic of the history of segmental duplications is the frequent duplication and transposition of long segments over large physical distances; as many as 50–60% of segmental duplications were transposed interchromosomally (Bailey and Eichler, 2006). Several general models of rearrangement that allowed for both local operations and duplication–transposition-like operations between different strings were studied by Ergun et al. (2003), but the generality of those models meant that the distances were NP-hard to compute and only approximation algorithms were given.

Here, we present a novel formulation of the problem of computing an evolutionary history for a set of segmental duplications that are organized in duplication blocks. We represent evolutionary relationships between a set of duplication blocks as a directed acyclic graph (DAG), and we formalize the evolutionary reconstruction problem as an optimization over the space of DAGs.

We present two different methods for scoring a DAG: one based on parsimony and one based on likelihood. The parsimony score for a DAG is a straightforward extension of ‘duplication distance’, a measure introduced by some of us (Kahn and Raphael, 2008, 2009) that describes the most parsimonious sequence of duplicate operations needed to construct a given target string. The likelihood score for a DAG is the product of the likelihood scores for each of the duplication blocks, where a duplication block's likelihood is derived by computing the weighted ensemble of all possible duplication scenarios that could have generated it. We describe how to compute the partition function of the ensemble efficiently using a dynamic program that generalizes the duplication distance (i.e. parsimony score) recurrence. Deriving a probabilistic model from a dynamic program this way is analogous to the approach of McCaskill (1990) who applied dynamic programming to RNA folding to compute the partition function of all secondary structures and to assign probabilities to certain substructures..

Finally, we solve these evolutionary reconstruction problems on the set of duplication blocks identified by Jiang et al. (2007) using a local search technique based on simulated annealing. We compare these reconstructions to the analysis of Jiang et al. (2007). Our evolutionary reconstruction recapitulates some of the properties of earlier analysis but also reveals additional and more subtle relationships between segmental duplications.

2 METHODS

Here, we present two methods for determining the optimality of an evolutionary relationship between a pair of duplication blocks—one based on a parsimony criterion and one based on a likelihood criterion. In Sections 2.1 and 2.2, we describe the parsimony-based model of segmental duplication that is based on duplication distance, introduced in Kahn and Raphael (2008, 2009). Next, we present a novel probabilistic model of segmental duplication that we use to compute the likelihood score for an evolutionary relationship between a pair of duplication blocks.

2.1 A model of segmental duplication

As noted above, an important characteristic of segmental duplications that distinguishes them from other types of repeats is that they are frequently transposed across large genomic distances from their respective ancestral loci. In Kahn and Raphael (2008, 2009), we modeled the process in which a duplication block, a composite of many duplicons, is built by copying strings of duplicons from other duplication blocks. In particular, we define the basic ‘copy–paste’ operation as follows.

Definition 2.1. —

A duplicate operation, δs,t,p(X), copies a substring Xs,t of a source string X and pastes it into a target string at position p.1 Specifically, if X = x1…xm and Z = z1…zn, then Z ○ δs,t,p(X) = z1…zp−1xs…xtzp…zn.

Definition 2.2. —

The duplication distance,2 d(X, Y), from a source string X to a target string Y is the minimum number of duplicate operations needed to construct Y by copying and pasting substrings of X into an initially empty target string.

A subsequence is distinguished from a substring because the characters of a subsequence need not be contiguous. Given a string X, a subsequence S of X can be expressed as an increasing list of indices of X. For example, for X = abcdefg, the subsequence S = (1, 3, 5) is the string ace.

Definition 2.3. —

Two subsequences S = (s1, s2,…, sls) and T = (t1, t2,…, tlt) of a string X overlap if either (i) there exist indices i : 1 ≤ i < ls and j : 1 ≤ j < lt such that i = j, or (ii) there exist indices i, i′ : 1 ≤ i < i′ < ls and a j, j′ : 1 ≤ j < j′ < lt such that either i < j < i′ < j′ or j < i < j′ < i′.

Given a source/target pair X, Y, any sequence of duplicate operations of the form δs1,t1,p1(X),…, δsd,td,pd(X) that generates Y from X uniquely partitions the characters of Y into non-overlapping subsequences corresponding to characters that were copied conjointly from X.

Definition 2.4. —

Given a source string X, a generator ΨX = (Xi1,j1,…, Xik,jk) is a sequence of substrings of X.

Definition 2.5. —

A generator ΨX = (Xi1,j1,…, Xik,jk) is feasible for a target string Y, that we denote as ΨX ⊣ Y, if:

The elements of ΨX partition the characters of Y into mutually non-overlapping subsequences {S1,…, Sk}.

There exists a bijective mapping f : {Xi,j∈ ΨX} → {S1,…, Sk} from substrings of X to subsequences in Y corresponding to how the elements of ΨX partition Y.

The order of elements in ΨX corresponds to the order of the leftmost characters of the subsequences f(Xi1,j1),…, f(Xik,jk) in Y.

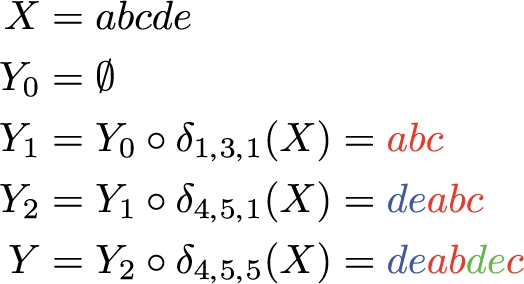

See Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

An example of a sequence of duplicate operations that constructs Y = deabdec from X = abcde. The corresponding feasible generator is: ΨX = (X4,5, X1,3, X4,5) = ((de), (abc), (de)).

A sequence of k duplicate operations that constructs Y from X uniquely defines a feasible generator ΨX with length k whose elements correspond, respectively, to substrings of X that are duplicated conjointly in a single operation.

2.2 Parsimony

In Kahn et al. (2010), we describe a polynomial-time algorithm to compute the duplication distance from X to Y. We use duplication distance to measure the similarity between a pair of duplication blocks by counting the number of operations needed to generate Y from X in a simplest or most-parsimonious scenario.

While the parsimony assumption is attractive from a theoretical perspective and can produce useful biological insight, it might be overly restrictive, particularly when there are many different optimal or nearly optimal solutions. Consider, for example, the strings X = ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’, ‘e’, ‘f’, and ‘g’, hijkl, and Y = agdbhecifdajebkfclg. The duplication distance, d(X, Y), is 13 and there is a single feasible generator with this optimum length. However, there are 989 possible feasible generators for Y, 119 of which have length 14, just slightly suboptimal.

Because the space of all possible feasible generators is very large, a probabilistic model might give very low probability to an optimal parsimony solution. Thus, in the next section, we present a probabilistic model of segmental duplication that considers the weighted ensemble of all feasible generators for a source/target string pair.

2.3 The partition function

For a given source string X and positive integer k, we consider the space of all length-k generators ΨX. We define a probability distribution on the collection of generators by defining Pr[ΨX] ∝ ω(ΨX) where ω(ΨX) is the ‘score’, or weight, assigned to a generator, and we compute the partition function ZX(k) of the weighted ensemble of all possible length−k generators ΨX. Given a source string X and a target string Y, we define the event F to be the event of choosing a length-k generator that is feasible for Y from the space of length-k generators. We define a probabilistic model for segmental duplications that, given a target string Y, assigns a probability to F: Pr[F|Y, X, k]. For a fixed target string Y, the probability, Pr[F|Y, X, k], is the weighted ensemble of all possible length-k generators that are feasible for Y, normalized by the partition function ZX(k). In particular, we can express the probability as:

| (1) |

where |ΨX| denotes the length of the generator. The likelihood of a target string Y then can be expressed as L(Y|F, X, k) = Pr(F|Y, X, k).

The score of a generator, ω(ΨX), can be defined according to various biological models. Although different functions ω may require different algorithms for computing the value Pr[F|Y, X, k], we found that functions of the form ω(ΨX) = σ(|ΨX|, l(ΨX)) where l(ΨX) = ∑Xi,j∈ΨX |Xi,j| denotes the sum of the lengths of the elements of ΨX, admit particularly efficient algorithms for computing Equation (1). We discuss the score function further in Supplementary Section 1.2.

Now, we give an algorithm to compute the partition function, ZX(k). Given a score function of the form σ(|ΨX|, l(ΨX)), each length-k generator whose elements have lengths that sum to l are scored the same, namely σ(k, l). Therefore, in order to compute ZX(k), we must calculate the total number of length-k generators whose lengths sum to l for all relevant values of l. Let 𝒞X(k)(l) equal the number of distinct length-k generators for which the sum of the lengths of the elements equals l.3

Lemma 2.6. —

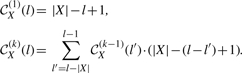

Let X = x1…x|X| be a source string and let k and l be positive integers. The function 𝒞X(k)(l) satisfies the following recurrence.

For a source string X and integers k, l, if we are given 𝒞X(k)(l), we can compute ZX(k) efficiently by summing 𝒞X(k)(l) over all relevant lengths l, weighting each feasible generator appropriately according to the function σ(k, l).

Theorem 2.7. —

Let X = x1…x|X| be a source string and k be a positive integer. The partition function ZX(k) satisfies the following.

Note that the elements of a length-k list of substrings of X can have lengths that sum to at least k and at most |X| · k.

The recurrence in Lemma 2.6 can be computed in O(|X|k) time, so ZX(k) can be computed in O(|X|2k2) time according to Theorem 2.7. We omit a proof of correctness due to space considerations.

2.4 Restricted partition function

In this section, we present the final ingredient necessary to compute the probability Pr[F|Y, X, k], namely the sum in Equation (1) that we define as QX(k)(Y). We refer to the value QX(k)(Y) as the restricted partition function of feasible generators, and it is equal to the weighted ensemble of all length-k generators ΨX that are feasible for Y. Hence QX(k)(Y) = ∑ΨX⊣Y:|ΨX|=kω(ΨX) = ∑ΨX⊣Y:|ΨX|=kσ(k, |Y|).

In order to compute this value, we generalize the recurrence presented in Kahn et al. (2010) for computing duplication distance from source string X to target string Y to count the number of length-k generators that are feasible for Y.

Lemma 2.8. —

Given a source string X = x1…x|X| and a target string Y = y1,…, y|Y|, the number NX(k)(Y) of distinct length-k generators ΨX that are feasible for Y satisfies the following recurrence.

Here, the term NX(k)(Y, i) represents the number of feasible generators ΨX with length k given that the character y1 is generated by a substring of X starting at xi.

We compute the restricted partition function QX(k)(Y) efficiently by first counting the number of relevant feasible generators, namely NX(k)(Y), and scoring each generator appropriately by σ(k, |Y|).

Theorem 2.9. —

Let X = x1…x|X|, Y = y1,…, y|Y| be a source/target string pair and let k be a positive integer. The restricted partition function QX(k)(Y) satisfies the following.

The recurrence given in Lemma 2.8 can be computed in time O(|Y|2k2μ(Y)μ(X)) where μ(Y) (resp. μ(X)) is the maximum multiplicity of any character that appears in Y (resp. X), so computing QX(k)(Y) takes the same time. We include a proof of correctness in Supplementary Section 1.1.

3 ALGORITHM

Here, we formalize the problem of computing a segmental duplication evolutionary history for a set of duplication blocks in the human genome with respect to either a parsimony or likelihood criterion.

3.1 Maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood evolutionary histories

The input to our problem is the set of duplication blocks found in the human genome, each represented as a signed string on the alphabet of duplicons. Our goal is to compute a putative duplication history that accounts for the construction of all of the duplication blocks. We assume that the ancestral genome is devoid of segmental duplications. A duplication history is a sequence of duplicate events that first builds up a set of seed duplication blocks by duplicating and aggregating duplicons from their ancestral loci and then successively constructs the remaining duplication blocks by duplicating substrings of previously constructed blocks.

We observed in Kahn and Raphael (2008) strong evidence that many of the duplication blocks identified by Jiang et al. (2007) had been constructed through the duplication and aggregation of substrings of duplicons from several other blocks. Therefore, a tree cannot aptly represent an evolutionary history; a more appropriate representation of the evolutionary relationships between duplication blocks is a DAG in which the vertices represent duplication blocks and an edge directed from a vertex X to a vertex Y indicates that substrings of X were duplicated in the construction of Y. A vertex with multiple incoming edges and, therefore, multiple parents, is constructed using substrings of all of the parent blocks. Specifically, given a DAG G = (𝒟, E), for Y ∈ 𝒟, we define PG(Y), the parent string of Y, by PG(Y) = X1 ⊙ X2 ⊙…⊙Xp where Xi ∈ {𝒟|(Xi, Y) ∈ E} and ⊙ indicates the concatenation of two strings with a dummy character inserted in between.

We make two simplifying assumptions. First, we assume that only duplicate events occur and that there are no deletions, inversions, or other types of rearrangements within a duplication block. Second, we assume that a duplication block is not copied and used to make another duplication block until after it has been fully constructed, ensuring the evolutionary relationships cannot contain cycles. We acknowledge that our two simplifying assumptions restrict the evolutionary history reconstruction problem significantly, but admit an efficient and consistent method of scoring a solution. Similar assumptions were made, for example, by Price et al. (2004) to derive the evolutionary tree for Alu repeat elements.

We can define the optimal DAG with respect to a parsimony criterion using duplication distance (Definition 2.2).

Definition 3.1. —

Given a set of duplication blocks 𝒟, the maximum parsimony evolutionary history is the DAG G = (𝒟, E) that minimizes f(G) = ∑Y∈𝒟d(PG(Y), Y).

We can also define the optimal DAG with respect to a likelihood criterion. In phylogenetic tree reconstruction, a max likelihood solution is a tree that maximizes the probability of generating the characters at the leaf nodes over all possible tree topologies, branch lengths, and assignments of ancestral states to the internal nodes. Typically, the evolutionary process is assumed to be a Markov process so that the probabilities along different branches are independent. We similarly define the maximum likelihood DAG using the probabilistic model derived in Section 2. We maximize the likelihood of the solution over all DAG topologies and—instead of branch lengths—the numbers of operations permitted to construct each node.

Definition 3.2. —

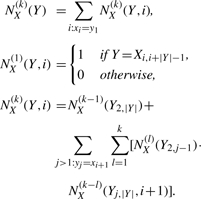

Given a set of duplication blocks 𝒟, the maximum likelihood evolutionary history is the DAG G = (𝒟, E) that maximizes the likelihood:

where ZPG(X)(k) and Q(k)PG(Y) are the partition function and restricted partition functions, respectively.

4 IMPLEMENTATION

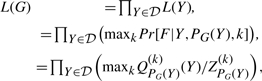

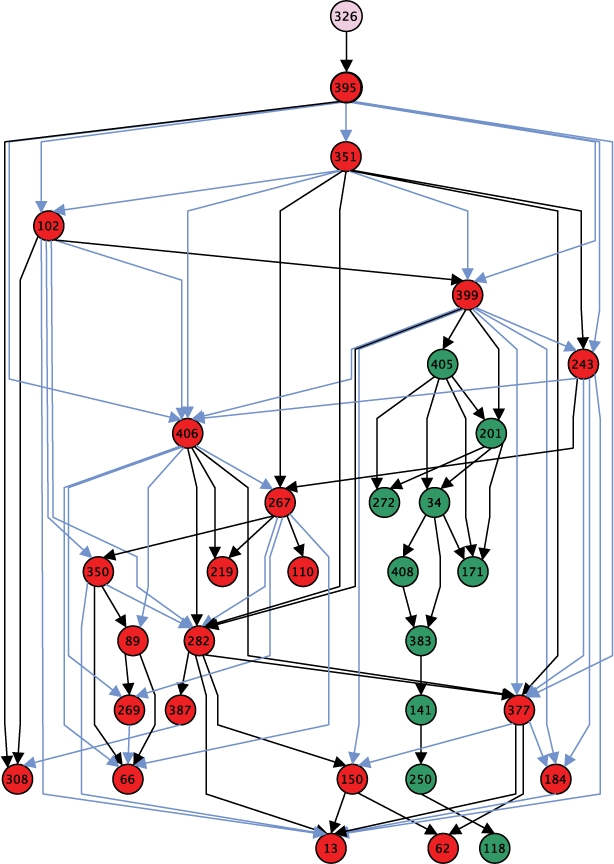

We analyzed a set of 391 duplication blocks identified by Jiang et al. (2007) that were represented as signed strings on an alphabet of ≈ 11 000 duplicons. We computed the maximum parsimony evolutionary history (Definition 3.1) for the entire set of blocks (Fig. 2). The DAG exhibited multiple connected components. For comparison, we then computed the maximum likelihood evolutionary histories (Definition 3.2) for several of the subgraphs induced by connected components of the parsimony solution. We scored generators according to  (see Supplementary Section 1.2).

(see Supplementary Section 1.2).

Fig. 2.

The maximum parsimony DAG for a set of 391 duplication blocks in the human genome. The nodes represent duplication blocks. Edges indicate evolutionary relations; an edge is directed from a node u to a node v if the most-parsimonious duplication scenario includes duplication events that copy substrings of u in the construction of v. Jiang et al. (2007) partitioned the duplication blocks into a set of 24 clades (plus one ‘s’ group of duplication blocks found in subtelomeric regions) that we indicate here with 25 colors on nodes. The 3 sets of colored edges represent inheritance networks for 3 conserved subsequences of duplicons. These inheritance networks are almost entirely confined to a single clade each. The green edges represent the inheritance of the duplicon sequence [6968, 6967, 6965, 6963, 6962, 6960] in clade ‘M1’, the red edges represent the inheritance of [7039, 7036, 7037] in clade ‘M2’, and the blue edges represent the inheritance of [9448,9449] in clade ‘chr16.’

We used a simulated annealing strategy to find a maximum parsimony DAG for the entire set of duplication blocks and to find maximum likelihood DAGs for several subgraphs4 (see Supplementary Section 1.3 for details). For each input, we ran our local search 300 times. We started the search an equal number of times at each of three different types of initial graphs: (i) the empty graph with no edges; (ii) the directed minimum spanning tree (MST); and (iii) a randomly chosen DAG (chosen independently for each trial). Finally, to focus the search on the most important block relationships, we considered only edges between blocks whose longest common subsequence (LCS) contained at least 20 duplicons.

4.1 Maximum parsimony reconstruction

The maximum parsimony DAG contains 391 nodes and 479 edges. There are nine connected components with at least four duplication blocks, and nearly 40% of the blocks appear in the largest connected component. Figure 3 shows a moderately-sized connected component. The graph also contains a total of 105 singleton nodes for which we did not infer any evolutionary relations with other duplication blocks, 97 of which did not exhibit an LCS of length 20 with any other block.

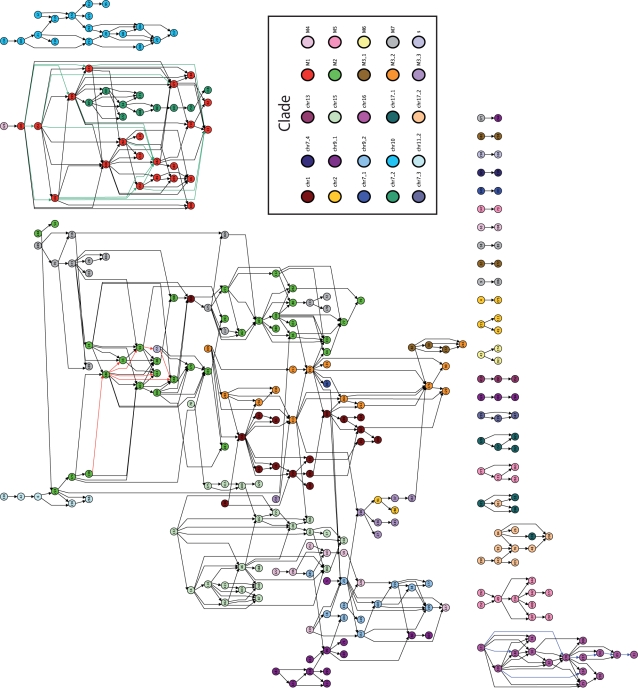

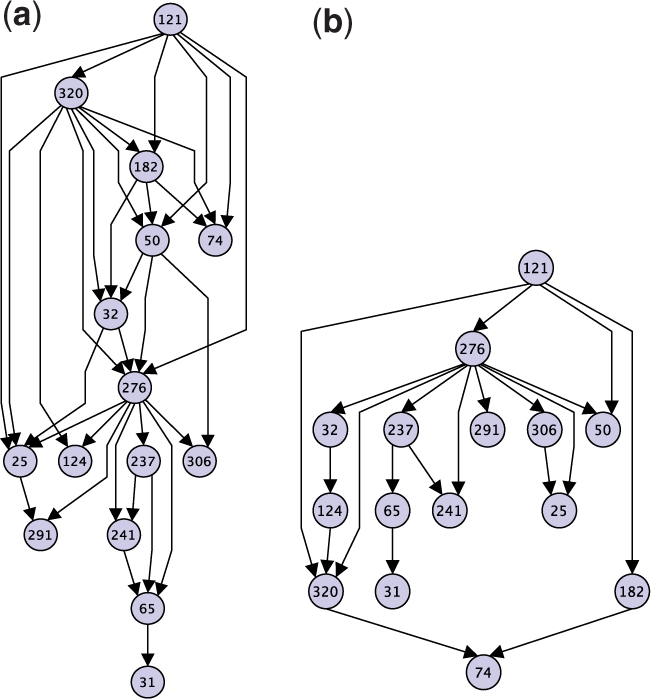

Fig. 3.

A connected component of the maximum parsimony DAG. Nodes from clade ‘M1’ are red and nodes from clade ‘chr7_2’ are green. Node labels correspond to duplication block IDs. The blue edges represents the inheritance network for non-core duplicon 6970.

The maximum parsimony DAG represents a scenario in which all 391 duplication blocks could have been constructed in a sequence of 17 431 total duplicate operations. As a baseline comparison, a minimum spanning tree, with respect to duplication distance, on the set of duplication blocks has a total parsimony score of 28 852 and by definition, contains 390 edges.

4.2 Clades and core duplicons

Jiang et al. (2007) performed an initial analysis of the duplication blocks. They defined 24 clades, or groups of duplication blocks derived from a common ancestor block, by performing hierarchical clustering on a matrix representing the shared presence or absence of duplicons for every pair of blocks. For a given clade they defined a core duplicon as one that appears in at least 67% of the constituent duplication blocks. They posited that clades represent families of evolutionarily related duplication blocks and that core duplicons ‘may have driven the evolution of the duplication blocks’ in a clade.

After construction, we colored the nodes of our DAG according to the clades described in Jiang et al. (2007). We found a strong correspondence between Jiang et al.'s clades and connected subgraphs in our DAG; five of the nine connected components with at least four blocks were comprised of duplication blocks belonging to a single clade and seven of the nine components were comprised of blocks belonging to no more than two clades. For example, see Figures 4a and 5a. In larger components, nodes from a single clade frequently induce a connected subgraph. For example, see Figure 3.

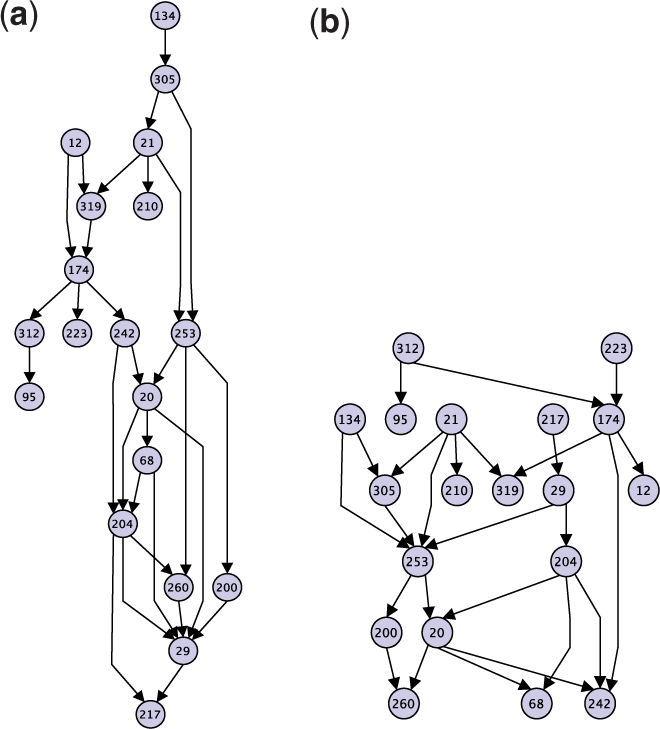

Fig. 4.

(a) Component comprised entirely of duplication blocks from clade ‘chr16’ in the maximum parsimony DAG. (b) Maximum likelihood DAG for subgraph induced on nodes in (a).

Fig. 5.

(a) Component comprised entirely of duplication blocks from clade ‘chr10’ in the maximum parsimony DAG. (b) Maximum likelihood DAG for subgraph induced on nodes in (a).

Our DAG also reveals which duplication blocks may have seeded many other blocks (i.e. those with high out-degree). For example, in Figure 3, block 399 exhibits eight children and is an inflection point for the component. Moreover, the edge from block 399 to 405 links blocks from the the ‘M1’ and ‘chr7_2’ clades. Even though the blocks 399 and 405 belong to different clades, 405 is very ‘close’ to 399 in duplication distance: block 405 contains only 71 duplicons, but it shares a subsequence of 29 duplicons with block 399. This link suggests that the entirety of clade ‘chr7_2’ was descended from clade ‘M1’ in an optimal duplication history.

Also implicit in the DAG is information about which duplicons are duplicated from one block to another in an optimal duplication history. We define the inheritance network for each duplicon as the subgraph induced on the edges on which that duplicon is passed from parent to child. Interestingly, a comparison of the inheritance networks for core and non-core duplicons revealed that many non-core duplicons exhibit larger inheritance networks within subgraphs induced by a clade than core duplicons. For example, non-core duplicon 6970 appeared on 36 of the 63 total edges in the subgraph induced by clade ‘M1’ (shown in blue in Fig. 3) and does not appear on any other edge in the graph. In contrast, the maximum size of the inheritance network of a core duplicon was only 17. We propose 6970 as a new core duplicon for this clade and suggest that others like it should also be categorized as core duplicons.

Moreover, we found inheritance networks for many conserved subsequences of duplicons that were nearly as prominent as those for individual core duplicons. For example, the subsequence [6968, 6967, 6925, 6963, 6962] of duplicons appears on 23 of the edges in the subgraph induced by ‘M1’ clade nodes (shown as green edges in Fig. 2). Similarly, the sequence [7039, 7036, 7037] exhibits a connected inheritance network of 7 edges within the subgraph induced on clade ‘M2’, and [9448, 9449] exhibits an inheritance network of seven edges within the subgraph induced on clade ‘chr16’ that includes an inheritance path of length 5 (Fig. 2). By delineating the inheritance networks of duplicon subsequences that are conserved across duplication blocks, we can learn about which duplicons were duplicated and transposed conjointly. This type of analysis was impossible using only the clade annotations of Jiang et al. (2007).

4.3 Maximum likelihood reconstruction

We computed the maximum likelihood DAGs (Definition 3.2) for the sets of duplication blocks appearing within moderately sized connected components of the maximum parsimony DAG in order to compare the two methods. We chose the components comprised of blocks from clades ‘chr16’ and ‘chr10’, respectively (Fig. 2). The maximum likelihood subgraphs for these subproblems are shown in Figures 4b and 5b.

The two DAGs for the ‘chr16’ component in Figure 4 share some characteristics. For example, node 121 is a common ancestor of every other block and block 276 exhibits high out-degree in both solutions. Both solutions are similarly ‘good’ with respect to the parsimony objective: the solution in (a) exhibits an optimal parsimony score of 397, and the one in (b) exhibits a score of 401. However, the likelihood score for the parsimony solution in (a) was nearly zero. One difference that accounts for this discrepancy is the higher average in-degree for blocks in the parsimony solution (2.2) as compared to the likelihood solution (1.3). Also, the parsimony solution exhibits a path with ten edges, whereas the longest path in the likelihood solution has six.

Some of these differences are due to the fact that the parsimony criterion does not penalize edges that do not directly improve the score. For example, block 291 has two parents (276 and 25) in the parsimony DAG but only one parent (276) in the likelihood DAG. However, the duplication distance with source 276 ⊙ 25 and target 291 is the same as the duplication distance with source 276 and target 291. Therefore, the edge from 25 to 291 does not improve the parsimony score, underscoring that there are multiple optimal parsimony solutions. In contrast, the likelihood of a target block generally increases as the sum of the lengths of its parent blocks decreases, so the max likelihood DAG will not include edges that do not directly improve the score.

5 DISCUSSION

Our maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood reconstructions show some differences, both from each other and from the analysis of Jiang et al. (2007). In particular, we identify non-core duplicons and subsequences that are arguably as promiscuous within a clade as core duplicons.

There are several directions for future work. From a theoretical perspective, one can incorporate other types of operations into the probabilistic model, such as deletions and inversions which we have described in the parsimony setting (Kahn et al., 2010), as well as single nucleotide mutations. Also, our method could be used to sample over the space of DAGs using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo strategy. From the perspective of applications, a more comprehensive analysis of genes or other elements in the newly identified core duplicons and core subsequences from our reconstruction is warranted, as is a further refinement of the clade annotation by analyzing the clade-induced subgraphs of the DAGs.

Funding: Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to B.J.R.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

1In (Kahn and Raphael, 2008, 2009), we also considered duplicate reversals in which the copied substring is inverted before being inserted into the target. We note that all of our definitions and algorithms presented here can be similarly augmented but we omit the details.

2We note that the duplication distance between a pair of strings is not formally a distance as it is asymmetric.

3The value 𝒞X(k)(l) is related to the well-known integer partition function p(n) and corresponding Young tableaux. If 𝒫(l, k) is the set of partitions of the integer l into k parts, we can express 𝒞X(k)(l) = ∑P∈𝒫(l,k)∑p∈P(|X| − p +1) · k!.

4Both the max parsimony and max likelihood versions of the problem can be shown to be NP-hard by a reduction from the problem of Learning Bayesian Networks.

REFERENCES

- Alkan C, et al. Personalized copy number and segmental duplication maps using next-generation sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/ng.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J, Eichler E. Primate segmental duplications: crucibles of evolution, diversity and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:552–564. doi: 10.1038/nrg1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blekhman R, et al. Segmental duplications contribute to gene expression differences between humans and chimpanzees. Genetics. 2009;182:627–630. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.099960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri K, et al. Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA) New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2006. On the tandem duplication-random loss model of genome rearrangement; pp. 564–570. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mabrouk N. Reconstructing an ancestral genome using minimum segments duplications and reversals. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2002;65:442–464. [Google Scholar]

- Ergun F, et al. Proceedings FST TCS '03. Vol. 2914. Berlin: Springer; 2003. Comparing sequences with segment rearrangements; pp. 222–234. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, et al. Ancestral reconstruction of segmental duplications reveals punctuated cores of human genome evolution. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1361–1368. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn CL, Raphael BJ. Analysis of segmental duplications via duplication distance. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i133–i138. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn CL, Raphael BJ. A parsimony approach to analysis of human segmental duplications. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2009;14:126–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn C, et al. Efficient algorithms for analyzing segmental duplications with deletions and inversions in genomes. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2010;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie M, et al. Duplication and inversion history of a tandemly repeated genes family. J. Comp. Bio. 2007;14:462–478. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2007.A007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marron M, et al. Genomic distances under deletions and insertions. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2004;325:347–360. [Google Scholar]

- McCaskill J. The equilibrium partition function and base pair binding probabilities for RNA secondary structure. Biopolymers. 1990;29:1105–1119. doi: 10.1002/bip.360290621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A, et al. Whole-genome analysis of Alu repeat elements reveals complex evolutionary history. Genome Res. 2004;14:2245–2252. doi: 10.1101/gr.2693004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankoff D. Genome rearrangement with gene families. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:909–917. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.11.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.