Abstract

Rationale: Ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) significantly contributes to mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, the most severe form of acute lung injury. Understanding the molecular basis for response to cyclic stretch (CS) and its derangement during high-volume ventilation is of high priority.

Objectives: To identify specific molecular regulators involved in the development of VILI.

Methods: We undertook a comparative examination of cis-regulatory sequences involved in the coordinated expression of CS-responsive genes using microarray analysis. Analysis of stretched versus nonstretched cells identified significant enrichment for genes containing putative binding sites for the transcription factor activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3). To determine the role of ATF3 in vivo, we compared the response of ATF3 gene–deficient mice to wild-type mice in an in vivo model of VILI.

Measurements and Main Results: ATF3 protein expression and nuclear translocation is increased in the lung after mechanical ventilation in wild-type mice. ATF3-deficient mice have greater sensitivity to mechanical ventilation alone or in conjunction with inhaled endotoxin, as demonstrated by increased cell infiltration and proinflammatory cytokines in the lung and bronchoalveolar lavage, and increased pulmonary edema and indices of tissue injury. The expression of stretch-responsive genes containing putative ATF3 cis-regulatory regions was significantly altered in ATF3-deficient mice.

Conclusions: ATF3 deficiency confers increased sensitivity to mechanical ventilation alone or in combination with inhaled endotoxin. We propose ATF3 acts to counterbalance CS and high volume–induced inflammation, dampening its ability to cause injury and consequently protecting animals from injurious CS.

Keywords: mechanotransduction, transcriptional profiling, acute respiratory distress syndrome, bioinformatics, transgenic mice

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY.

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Cyclic-stretch–induced inflammation is an important component of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). Although cyclic stretch is known to differentially regulate gene and protein expression in vivo and in vitro, no unifying hypothesis to explain the coordinated response to mechanical ventilation-induced lung injury has emerged.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Cell stretch results in differential expression of genes that share a cis-regulatory binding site for activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3). Absence of ATF3 confers increased sensitivity to VILI, identifying ATF3 as an important early transcriptional regulator of cyclic-stretch–induced responses and providing strong evidence for the causal relationship between biophysical force-dependent gene expression profile regulation and the development of VILI.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a catastrophic form of acute lung injury (ALI) (1). The necessity for mechanical ventilation (MV) renders patients at risk for ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). Exposure to repetitive cyclic stretch (CS) and/or overinflation exacerbates injury. Reducing tidal volume (VT) is the only therapeutic strategy shown to mitigate morbidity and mortality (2). CS has been shown to differentially regulate gene expression in part through the activation of mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (3). Although these studies have shown both molecular and cellular alterations, no unifying hypothesis to explain MV-induced lung injury has emerged.

Previously, we explored the hypothesis that ALI is not a stereotyped response of the lung to injury, but rather a composite of specific responses to different coexisting injurious stimuli (4). Exploring the global response to injury using microarray technology reveals the presence of injury-specific differential expression in comparable lung injury models. Moreover, genes that share transcription profiles in response to VILI, such as tissue factor and pentraxin 3 (3, 5), are biologically related to lung injury suggesting the information contained within expression profiles can help to identify and inform regarding genes mechanistically related to VILI.

In the current study, we hypothesized that coordinated expression of CS-responsive genes relies on the presence of common CS-sensitive regulatory elements. To identify CS-responsive genes that play a role in VILI, we undertook a comparative examination of the gene expression profile of human bronchial epithelial airway (Beas-2B) cells in response to various injurious stimuli involved in the pathogenesis of ALI/VILI: CS, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS). To identify common features among CS differentially expressed genes, we screened cis-regulatory regions of CS differentially expressed genes for known transcription factor binding sites to identify transcription factors that may play a role in defining the CS gene expression profile. Analysis of stretched versus nonstretched cells identified significant enrichment for genes containing putative binding sites for the transcription factor activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), a member of the mammalian activation transcription factor/cAMP responsive element (CRE) family.

ATF3 is an early-induced gene (6) involved in diverse stress responses, including mechanical injury (7). ATF3 is also a negative transcriptional regulator that inhibits the expression of genes that mediate toll-like receptor (TLR) responses, known to play a role in stretch-induced injury (8). Here we demonstrate that ATF3 coordinates the expression of various genes involved in the CS response. Using a gene-deficient model we demonstrate that ATF3 is a transcriptional regulator that acts to counterbalance CS and high tidal volume–induced inflammation, limiting its potential to cause additional lung injury and consequently protecting animals from VILI. This is the first validation of the role of a transcription factor in VILI. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (9).

METHODS

Detailed methodology is available in the online supplement.

Reagents and Antibodies

Fluorescein-labeled (FITC) antibodies anti-mouse CD11b and its isotype control (Rat IgG2b, k) were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). FITC-labeled antibodies anti-F4/80 and its isotype control (Rat IgG2b) were obtained from Cedarlane (Hornby, ON, Canada). Anti-ATF3 polyclonal antibody and FITC-conjugated goat anti–rabbit-IgG were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and IgM ELISA kit was from Bethyl Laboratory (Montgomery, TX). Escherichia coli LPS (026:B6 and 055:B5) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Luis, MO). Recombinant human TNF-α was from Biosource (Camarillo CA) and mouse 10-Plex cytokine bead-based immunoassay was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA).

Cell Experiments

Human Beas-B2 cells grown on silicon elastic plates coated with Type I collagen (Flexercell International, McKeesport, PA) were exposed to six regimens for 4 hours: (1) control (static, [control]), (2) mechanical stretch (25 PKa, 30 cycles per min, [stretch]), (3) LPS (1 μg/ml [LPS]), (4) TNF-α (20 ng/ml; [TNF]), (5) mechanical stretch plus LPS [LPS+S], and (6) mechanical stretch plus TNF-α [TNF+S] (4).

Microarray

Total RNA (duplicate experiments) was hybridized to Affymetrix Human U133plus2.0 chips (4) (Gene Expression Omnibus). Probe-based analysis, background reduction, and quantile data normalization were performed in MeV 4.0 of TM4 (10) using robust multiarray average (4). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (11, 12) was used to detect coordinated expression of 22,232 expression sequence tags. Search for regulatory motifs was performed by screening cis-regulatory regions of differentially expressed genes for known transcription factor binding sites (C3 MSigDB database) (13).

VILI Experiments

All animals received care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (Canadian Council on Animal Care). Experimental protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of St. Michael's Hospital and University of Toronto.

Rats.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 24; 300–350 g; Charles River, Montreal, Quebec) were randomized to either no ventilation (NV), noninjurious ventilation (LVt 6 ml/kg, positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP] = 5 cm H2O), or injurious (high tidal volume [HVt], 12 ml/kg, PEEP = 0 cmH2O) ventilation with FiO2 0.4 for 4 hours (14). At the completion of the experiment, animals were sacrificed and samples collected for analysis.

Mice.

Male (n = 16/group, 20–25 g, 8–10 wk) ATF3 knock-out (ATF3 KO) (1), and wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) mice were randomized to intratracheal LPS (10 mg/kg) or equal volume saline, then randomized to NV or MV using previously reported settings (15, 16) consistent with either an injurious (HVt ≈15 ml/kg, PEEP = 2 cm H2O, pressure control [PC] = 17 cm H2O above PEEP), or protective (low tidal volume [LVt] ≈7.5 ml/kg, PEEP = 2 cm H2O, PC = 10 cm H2O above PEEP) strategy. All animals were ventilated with an FiO2 of 0.6 for 3 hours. Respiratory rate was set at 120 breaths/min and 80 breaths/min in the LVt and HVt, respectively.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid cell count and differential were performed manually and by FACS.

Quantitative Relative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted for quantitative relative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) (primer sequences in Table E1 in the online supplement). Expression of selected gene(s) was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and β-actin (3).

Inflammatory Mediators

IL-1β (IL-1β); IL-6; IL-10; IL-12 (70p); keratinocyte-derived chemokine; monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; regulated upon activation, normally T-expressed (RANTES); TNF-α; IFN-γ; and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating-factor levels were measured in lung tissue homogenates using a bead-based immunoassay following manufacturer's instructions (3–5).

Lung Injury

Pulmonary capillary permeability was assessed as gross increase in Evans blue dye staining; and IgM and total protein infiltration into BAL (17). Degree of lung injury was determined by histological lung injury score (3) (right lung 10 slides/animal, four animals/group) after hematoxylin and eosin stain.

ATF3 Protein

ATF3 protein expression was determined by Western blot of total and nuclear protein extraction (n = 4 animals/group), and immunohistochemistry (3–5).

Statistical Analysis

All samples were analyzed by investigators blinded to group assignment. Data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (two variables: strain and treatment in GraphPad Prism 5.0; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) with a Bonferroni post test. All values are expressed as mean (± SEM), P < 0.05 (adjusted P) was considered significant.

RESULTS

CS-induced Differential Expression of Genes Enriched for Putative ATF3 Binding Sites

To identify common features among CS differentially expressed genes in Beas-2B cells we used GSEA to screen the 4-kb segment centered on the transcription start site and 3′ region (3′-UTR microRNA binding motif) for known transcription factor binding sites contained in the Molecular Signatures DataBase (MolSigDB, C3 database) (13). A total of 24 gene sets were found to be significantly enriched among all stretch (Stretch, LPS+S, TNF+S) groups versus the no-stretch (Control, LPS, and TNF) samples. Two of the top five data sets identified were enriched for genes that share binding sites for ATF family of proteins (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

TOP PUTATIVE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR BINDING SITE ENRICHMENT FOR ALTERNATIVELY EXPRESSED GENES REGULATED IN STRETCHED VERSUS NONSTRETCHED CELLS

| Gene Set Name | Size | NES | NOM P Value | FDR q Value | FWER P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCGCCTT, MIR-525, MIR-524 | 12 | 1.852 | 0 | 0.057 | 0.043 |

| TGAYRTCA_VSATF3_Q6 | 319 | 1.762 | 0 | 0.125 | 0.175 |

| TGACGTCAVSATF3_Q6 | 155 | 1.735 | 0 | 0.124 | 0.247 |

| GCAAGGA, MIR-502 | 52 | 1.717 | 0.0016393 | 0.128 | 0.325 |

| GATAAGR_VSGATA_C | 158 | 1.685 | 0 | 0.171 | 0.488 |

Definition of abbreviations: FDR = false discovery rate; FWER = family-wise error rate; NES = normalized enrichment score; NOM = nominal P value for the enrichment value of an individual data set.

Includes genes with promoter regions [−2kb, 2kb] around transcription start site and/or 3′ region (3′-UTR microRNA binding motif) containing conserved motifs for ATF3 binding sites.

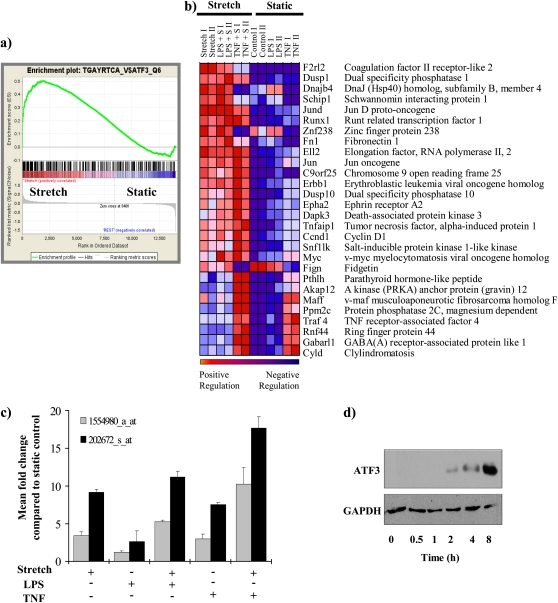

Briefly, genes from our microarray were ranked according to expression differences (signal/noise ratio) between stretch versus static. The extent of the association between the expression profile in each phenotype and the gene set is measured by a nonparametric running sum statistic (enrichment score [(ES]), and the maximum ES (MES) is recorded for each gene set. Permutation testing was used to assess statistical significance of the MES, yielding the normalized enrichment score (NES). False discovery rate (FDR [18]) adjusted for gene set sizes and multiple hypothesis testing. Based on default parameters, an FDR of less than 25% is considered statistically significant. Figure 1a shows individual plot for the progression of the running ES and the maximum peak therein for the top gene set containing genes enriched for putative ATF3 cis-regulatory regions. Figure 1b shows the corresponding heat map for the expression values for the genes containing putative ATF3 cis-regulatory sequence TGACGTCA in their 5′ and 3′ untranslated region that significantly contributed to the ES.

Figure 1.

Enrichment for genes containing putative activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) cis-regulatory binding sequences. (a) Individual plots for the progression of the running enrichment score (ES) and the maximum peak therein for the top gene set containing genes enriched for ATF3 cis-regulatory regions. The middle part shows the genes in each gene set as “hits” (black vertical lines) against the ranked list of genes. The bottom portion of the plot shows the value of the ranking metric as you move down the list of ranked genes. The ranking metric measures a gene's correlation with the phenotype. A positive value indicates correlation with the phenotype profile (stretch) and a negative value indicates no correlation or inverse correlation with the profile (no-stretch). (b) Corresponding heat map for the expression values for genes containing putative ATF3 cis-regulatory sequence TGACGTCA in their 5′ untranslated region (n = 12 chips) that are significantly differentially expressed between stretch and static. By convention, expression values are represented as a color spectrum going from red (up-regulated) to blue (down-regulated) depending on the correlation with each specific phenotype (stretched versus nonstretched). (c) Mean fold change in expression of ATF3 message in each group compared with static control. Two separate probes for ATF3 are spotted in the array and fold change for each probe is plotted separately. (d) Representative Western blot for ATF3 protein expression in bronchial epithelial airway (Beas-2B) cells exposed to CS for the time periods indicated (n = 3). GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

CS-induced Up-Regulation of ATF3

To determine that the ATF3 gene itself was differentially expressed in Beas-2B cells exposed to CS, we analyzed our Affymetrix data using significant analysis of microarray (19). Multiclass analysis (analogous to a multivariate analysis of variance) identified 765 expression sequence tags that were differentially expressed in stretched cells (correction for multiple comparisons was applied, FDR = 1.18%). Figure E1 shows the top 20 genes identified as differentially expressed between stretch and no-stretch using significant analysis of microarray (Figure 2a). Two probe sets for ATF3 were identified as significantly up-regulated (1554980_a_at, and 202672_s_at, q < 0.05) in the chips used. In all samples, CS increased the levels of ATF3 mRNAs when compared with static control (Figure 1c). ATF3 gene expression was augmented by the combination of CS plus either LPS or TNF-α treatment. In separate experiments, the expression of ATF3 protein in Beas-2B cells was induced by CS in a time-dependent manner (Figure 1d). Overall, these data demonstrate that CS results in significant up-regulation of ATF3 at both the RNA and protein level.

Figure 2.

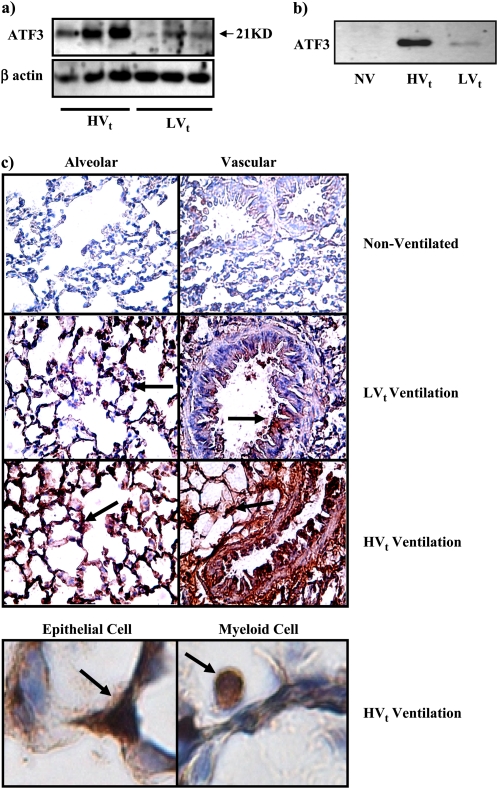

High or low tidal volume ventilation (HVt or LVt) for 4 hours increased activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) expression in rats. Western blot analysis showing ATF3 protein expression was increased both in (a) whole lung tissue cell lysate and (b) nuclear protein extracts from lung tissue of animals breathing spontaneously (nonventilated, NV) or ventilated with either HVt or LVt ventilation strategy. (c) ATF3 protein expression shown by immunohistochemistry (×60) in alveolar and vascular structures. Brown staining (arrows) indicates elevated ATF3 expression. Bottom panel shows detail of both epithelial and myeloid cells demonstrating ubiquitously increased ATF3 protein expression in lung tissues.

ATF3 Protein Level Is Increased in a Rat Model of VILI

To determine whether ATF3 protein level is significantly altered by mechanical forces in vivo, we examined ATF3 in a VILI model using Sprague-Dawley rats. HVt resulted in significant decrease in arterial oxygenation over the 4-hour period (Table E2a). Figure 2a shows increased ATF3 protein level in animals ventilated with HVt. As a transcription factor, ATF3 expression in the nuclear extracts from lung tissues was also higher in animals ventilated with HVt ventilation (Figure 2b). Immunohistochemistry for ATF3 protein shows that ATF3 expression is ubiquitously increased in both infiltrating myeloid and parenchymal cells from animals ventilated with HVt ventilation. Moreover, increased ATF3 expression is also clearly noticeable in animals treated with LVt (Figure 2c). These results show that ATF3 expression is significantly altered in vivo in a rat model of VILI, suggesting a role for ATF3 in VILI.

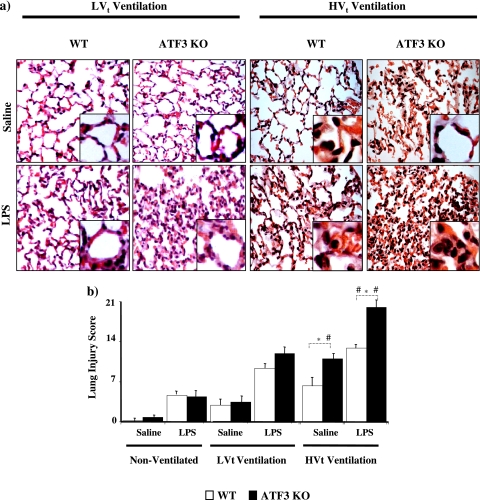

ATF3 Deficiency Confers Sensitivity to VILI-induced Increase in Lung Membrane Permeability

To test our bioinformatics hypothesis that ATF3 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of ALI and VILI, we compared the response of ATF3 KO and WT mice using a two-hit model of lung injury. Mice were randomized to either LPS (10 mg/kg) or equal volume saline inhalation (50 μl). Each group was then further randomized to no ventilation, LVt ventilation, or HVt ventilation. Eight mice per group were used to assess physiological response to lung injury (Table E2b). Although blood pressure dropped significantly in all ventilated animals, ATF3 deficiency did not result in a significant change in systemic blood pressure compared with WT animals (Table E2b). Both injurious ventilation and LPS significantly reduced PaO2/FiO2 ratios in all animals, although no differences were observed between ATF3-deficient and WT animals (Table E2b). ATF3 KO lungs were more susceptible to LPS and ventilation-induced lung injury than lungs from WT mice resulting in enhanced hyaline membrane formation, severe lung interstitial edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration and total lung injury score (Figure 3a and 3b).

Figure 3.

Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) deficiency results in increased lung injury. (a) ATK3 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice subjected to intratracheal instillation of LPS or equal volume saline. Animals were randomized to either nonventilation or ventilation with low tidal volume (LVt) or injurious high volume ventilation (HVt) for 3 hours. Representative photomicrographs with hematoxylin and eosin staining (×60). ATF3 KO mice had enhanced hyaline membrane formation, severe lung interstitial edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration compared with WT mice. Both LPS and HVt increased lung injury (n = 4 per group). (b) Lung injury scores were determined based on leukocyte infiltration, exudative edema, hemorrhage, and alveolar wall thickness. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4 per group). *P < 0.05 versus corresponding WT.

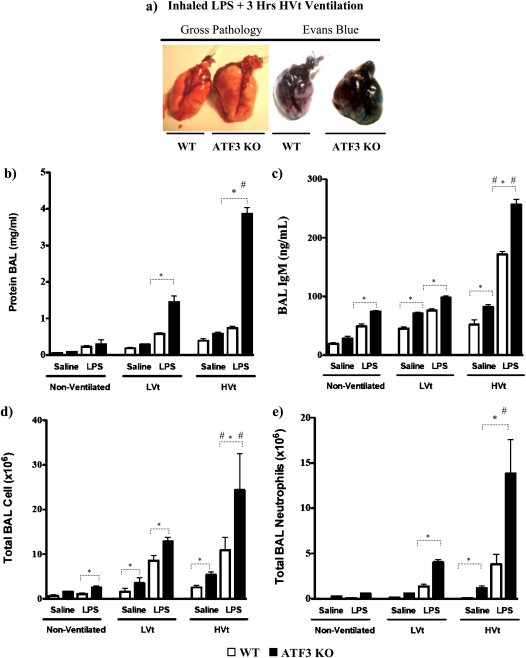

Alveolar permeability was also increased by the ATF3 phenotype as assessed by gross extravasation of Evans blue dye (Figure 4a). Alveolar protein was increased in the ATF3 KO mice in both LPS-treated ventilated animals (Figure 4b; LPS LVt-ventilated ATF3 KO vs. WT, P < 0.05; and LPS HVt-ventilated ATF3 KO vs. WT, P < 0.001). More importantly, injurious ventilation led to a marked increase in total alveolar protein in ATF3 KO mice exposed to LPS and HVt versus LVt (P < 0.01). IgM extravasation (Figure 4c) was significantly higher in all ATF3 KO mice versus corresponding WT mice; injurious ventilation in LPS-treated mice resulted in increased extravasation of IgM compared with LVt-ventilated mice (P < 0.05). Taken together these data suggest that ATF3 deficiency confers increased sensitivity to VILI-induced loss of alveolar–capillary membrane permeability.

Figure 4.

Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) deficiency results in increased lung permeability and cellular infiltration. (a) Representative images of gross pathology and Evans blue stain 3 hours after exposure to inhaled LPS and high tidal volume (HVt) ventilation in wild-type (WT) and ATF3 knockout mice (ATF3 KO). Note increased pulmonary edema in ATF3 KO mice compared with WT. (b) The effect of saline (single hit) and LPS (double hit) and mechanical ventilation with either low tidal volume (LVt), HVt, or nonventilated (NV) on protein influx in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. (c) Extravasation of IgM in BAL. (d) Total cell count. (e) Total neutrophil count. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6). *P < 0.05 between WT and ATF3 mice of similar ventilation strategy (NV, LVt, or HVt) and pretreatment (saline or LPS). #P < 0.05 versus LVt-ventilated mice of similar phenotype (WT or ATF3 KO) and pretreatment (saline or LPS).

ATF3 Deficiency Results in Increased VILI-induced Lung Inflammation

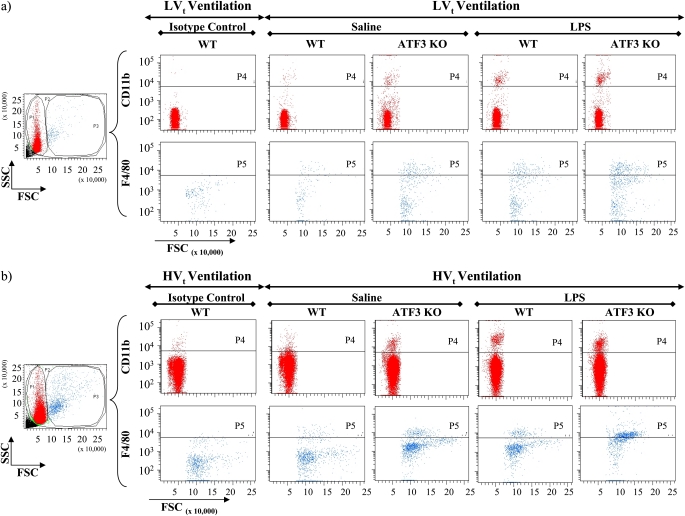

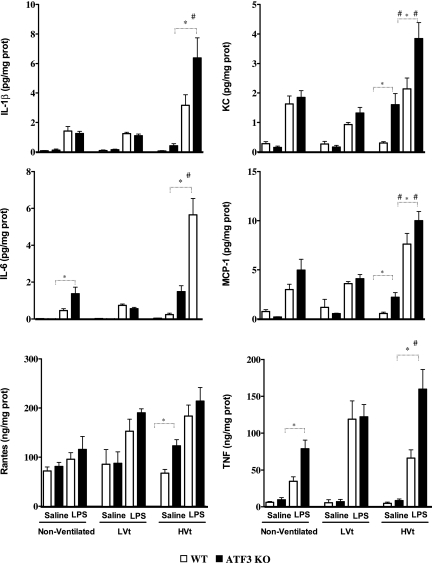

ATF3 may act as a negative regulator of the inflammatory response by inhibiting transcription of various proinflammatory genes in macrophages (20–22). We hypothesized that ATF3 deficiency may result in increased inflammation, explaining the increased sensitivity to injury seen above. Consistent with this hypothesis, ATF3 KO mice have increased total cell infiltration in BAL compared with WT (Figures 4d and 5c). Injurious mechanical ventilation and LPS significantly increased the total cell count (Figures 4d and 6c) and neutrophil infiltration in BAL (Figures 4e and 6c). FACS analysis of BAL fluid collected from ATF3 KO animals treated with LPS and/or MV using CD11b and F4/80 antibodies supports the evidence that absence of ATF3 results in increased cell infiltration (Figures 5a, 5b, 6a, and 6b). We did not detect any baseline differences in BAL fluid cell count in nonventilated animals (Figure 4d). Increased cell infiltration was accompanied by significant increase in lung tissue levels of proinflammatory cytokines: IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, RANTES, and keratinocyte-derived chemokine. Levels of inflammatory mediators were markedly increased in ATF3 KO mice in both single-hit models (LPS or ventilation alone) and the two-hit model of combined LPS and ventilation (Figure 7). Although low tidal volume already increased the inflammatory mediators, the susceptibility to injury was most severe during VILI (HVt). No significant increase in IL-10, IFN-γ, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor levels was detected in either of the two genotypes after 3 hours of mechanical ventilation (data not shown). Taken together, our data strongly suggest that, in comparison to WT, ATF3 KO mice have an increased sensitivity to mechanical ventilation and VILI, which results in an enhanced inflammatory response in the lung.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) collected from activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) knockout (KO) animals treated with LPS along with (a) low tidal volume (LVt) and (b) high tidal volume (HVt) ventilation showing increased infiltration of CD11b+ and F4/80+ cells in BAL. Aliquot of BAL was stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD11b and anti-F4/80 antibodies for FACS analysis as described in detailed Methods. As controls, other aliquots of BAL samples were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11b and anti-F4/80 isotype antibodies. Analyzed cells were divided into two populations based on cell size as exemplified in forward and sideward scatter dot blots (FSC and SSC). Using isotype controls, appropriate gates (P4 and P5) were defined to differentiate between CD11b+ and CD11b− cells in the subpopulation of smaller, and between F4/80+ and F4/80− cells in the subpopulation of larger BAL cells. CD11b+ cells likely reflect monocytes, neutrophils, and NK cells but not lymphocytes or nonmyeloid cells, whereas F4/80+ cells are considered to reflect macrophages. (a) Representative staining of BAL collected from mice treated with LVt ventilation strategy stained with anti-CD11b and anti-F4/80 antibodies and with their corresponding isotype control antibodies. Compared with (b) HVt, modest increases of CD11b+ and F4/80+ cell numbers were detected after 3 hours of LVt ventilation and LPS treatment. (b) Representative staining of BAL collected from mice treated with HVt ventilation strategy stained with anti-CD11b and anti-F4/80 antibodies and with their corresponding isotype control antibodies. Higher number of CD11b+ and F4/80+ cells was detected after 3 hours of HVt ventilation as compared with LVt-ventilated mice and after LPS treatment as compared with HVt ventilation in saline-treated mice. This effect was more pronounced in ATF3 KO mice as compared with respective wild-type (WT) control mice. *P < 0.05 as indicated. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6 per group).

Figure 6.

Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) deficiency results in increased cellular infiltrates and lung injury. Pulmonary sequestration of (a) CD11b+ and (b) F4/80+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry and is expressed as total positive cells (106) per lung. In ATF3 knockout (KO) mice, the combination of mechanical ventilation and LPS inhalation led to increased influx of CD11b+ and F4/80+ cells into the alveolar space compared with wild-type (WT) mice. Injurious ventilation significantly increased cellular influx compared with the lung-protective low tidal volume strategy. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 6). *P < 0.05 between WT and ATF3 KO mice of similar ventilation strategy (nonventilated [NV], low tidal volume [LVt] or high tidal volume [HVt]) and pretreatment (saline or LPS). #P < 0.05 versus LVt-ventilated mice of similar phenotype (WT or ATF3 KO) and pretreatment (saline or LPS). (c) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining photomicrographs of cytospin of BAL (×40) from WT and ATF3 KO mice ventilated with either LVt or HVt after exposure to either saline or LPS.

Figure 7.

Levels of inflammatory mediators in lung tissue homogenates of ATK3 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) KO and WT mice subjected to saline or LPS followed by low tidal volume (LVt) ventilation, high tidal volume (HVt) ventilation, or nonventilation (NV) as detailed in Figure 4. All of the mediator profiles altered by ventilator-induced lung injury that differed between ATF3 KO and WT mice are shown. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 8). *P < 0.05 between WT and ATF3 mice of similar ventilation strategy (NV, LVt or HVt) and pretreatment (saline or LPS). #P < 0.05 versus LVt-ventilated mice of similar phenotype (WT or ATF3) and pretreatment (saline or LPS).

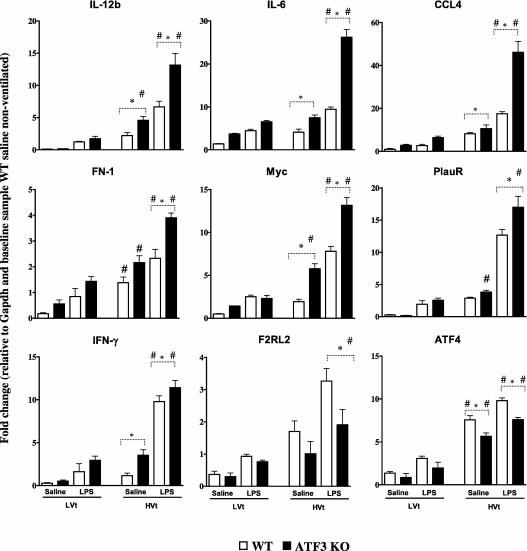

Changes in Expression of Genes Containing Putative ATF3 cis-Regulatory Sequences

To determine the effect of ATF3 deficiency on RNA levels of genes containing putative ATF3 cis-regulatory sequences after exposure to VILI, we performed qRT-PCR (Figure 8) on (1) genes identified in our cell-stretch microarray analysis, and (2) genes known from the literature to contain ATF binding sites (Table E1). Absence of ATF3, known to inhibit the expression of IL-6 (2, 3), results in increased IL-6 message in HVt- versus LVt-ventilated null mice after exposure to inhaled saline or LPS. The expression of other inflammation-related genes was also up-regulated in ATF3 KO, such as IL-12b, chemokine C-C motif ligand 4 (CCL4/MIP-1b), fibronectin, urokinase receptor, Myc oncogene (Myc), and IFN-γ. Although plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 is documented to have an ATF3 regulatory sequence and is markedly up-regulated in animals ventilated with a high tidal volume strategy, we did not see a significant difference between WT and ATF3 KO animals at 3 hours (data not shown). Two genes were down-regulated in the ATF3 KO mice, activation transcription factor 4 (ATF4), and coagulation factor II receptor-like 2 (F2rl2). Taken together, our results support the notion that ATF3 plays a critical role in regulating the inflammatory response to CS-induced lung injury.

Figure 8.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction of selected genes containing activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) cis-regulatory binding sequences. Lung tissues of ATK3 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice subjected to high tidal volume (HVt) ventilation or low tidal volume (LVt) ventilation as detailed in Figure 4. The gene expression was normalized against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The changes in gene expression are expressed as fold change relative to the baseline sample from nonventilation (NV) WT mice exposed to saline. ATF3 deficiency led to increased mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-12b, chemokine C-C motif ligand 4 (CCL-4), INF-γ, urokinase receptor (PlauR), coagulation factor II receptor-like 2 (F2rl2), fibronectin (FN1), Myc oncogene (Myc), and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 6). *P < 0.05 between WT and ATF3 mice of similar ventilation strategy (NV, LVt or HVt) and pretreatment (saline or LPS). #P < 0.05 versus LVt-ventilated mice of similar phenotype (WT or ATF3) and pretreatment (saline or LPS).

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we present a novel approach for using expression microarrays as translational tools to understand the biology of global responses to CS and to identify regulatory elements that act to counterbalance CS/HVt–induced injury that occurs in the context of inflammation, thus affecting the potential for additional lung injury. We postulated that the coordinated response to CS is composed of many small cumulative changes in gene expression that are regulated by common CS-sensitive cis-regulatory elements. To detect coordinated expression within treated samples of an a priori–defined group of genes, we analyzed the microarray data from stretched cells using GSEA. This approach is unique in that it capitalizes on even small changes in expressions of genes that share a functional or, in this case, a putative regulatory relationship. Our analysis identified ATF3, a transcription factor that has not been previously implicated in VILI, as a critical regulator of CS-induced differential expression in pulmonary cells. We then confirmed the biological validity of our finding by demonstrating that ATF3 confers protection against VILI, and its absence results in increased lung injury as evidenced by increased pulmonary permeability, increased cellular infiltration, inflammatory mediator expression, and histological evidence of worsening injury after injurious MV.

Although ATF3 has been implicated in many processes, including ischemia (22), infection (20), neuronal regenerative/injury response (23), DNA damage (24), apoptosis (25), tumorigenesis (26), antioxidant response (27), and hypoxemia (28), identification of its protective role in VILI is novel. The exact mechanisms of ATF3-conferred protection in VILI are unknown. Based on our data, and what is known about the role of ATF3 in the literature, we postulate that ATF3 may attenuate injury by acting as a negative transcriptional regulator of inflammation. In support of our hypothesis, in ATF3-deficient animals VILI resulted in increased BAL and tissue levels of proinflammatory mediators. This was accompanied by increased neutrophil/monocytes and macrophage infiltration, as indicated by elevated BAL levels of CD11b- and F4/80-positive cells. Proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-12b both have 5′ ATF3 binding sites. Gilchrist and colleagues (29) demonstrated that ATF3 binds to cis-regulatory sequences on these genes and inhibits the expression of IL-6 and IL-12b. This may be of significant clinical relevance for patients with VILI, because IL-6 has been implicated in injurious responses to CS and mechanical ventilation in patients with ARDS (2). Moreover, absence of ATF3 resulted in increased IL-6 and IL-12 expression in response to LPS. In keeping with this hypothesis, in ATF3 KO mice IL-6 and IL-12b mRNA levels were increased after VILI.

The aggravating effect of ATF3 deletion is not only evident in the double-hit VILI model, but in part also in the LPS spontaneous breathing animals. Thus, ATF3 may constitute an antiinflammatory regulator not only in VILI, but also in inflammatory lung disease in general. Recent evidence has implicated ATF3 as adaptive-response gene that participates in cellular processes to adapt to extra- and/or intracellular changes, where it transduces signals from various receptors to activate or repress gene expression. Advances made in understanding the immunobiology of toll-like receptors have recently generated new momentum for the study of ATF3 in immunity (20). An antiinflammatory role for ATF3 is further supported by evidence that it ameliorates allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a mouse model of human asthma (29).

Many of the genes identified, including ATF3, have been previously shown to be changed by HVt ventilation in animal models of VILI (3, 4, 6, 13) (e.g., growth arrest and DNA-damage–inducible α [Gadd 45a], plasminogen activator, urokinase, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1, Myc, fos-like antigen 2, and coagulation factor III [tissue factor, F3]). We also found up-regulation of transcripts encoding for CCL4/MIP-1b and IFN-γ. This is consistent with our hypothesis about the role of ATF3 in VILI and documented findings from the literature. ATF3 represses the expression of CCL4/MIP-1b from both unstimulated and LPS-stimulated macrophages (30). CCL4/MIP-1b promotes recruitment of leukocytes to the site of infection. Similar to other cytokines, CCL4/MIP-1b expression is controlled largely at the transcriptional level and an ATF/CRE sequence located in the promoter has been identified as a critical cis-acting element. ATF3 constitutively binds to the ATF/CRE site in the CCL4/MIP-1b promoter where it represses basal and pathogen-induced transcription. ATF3 also interacts with the IFN-γ promoter, down-regulating IFN-γ, but conferring increased sensitivity to murine cytomegalovirus infection. Message for IFN-γ is markedly up-regulated in ATF3 KO mice, although at 3 hours we did not detect a significant increase in the protein level in either genotype. Analysis of gene expression also showed up-regulation of other known proinflammatory genes, such as fibronectin, and urokinase receptor, known to contain ATF3 promoter binding motifs. These data strongly suggest that ATF3 may indeed protect animals from the detrimental effects of VILI by either directly or indirectly acting to counterbalance the effects of inflammatory injury in the context of VILI.

ATF3, like most other transcription factors, may not only be involved in down-regulating the expression of inflammation-related genes but also may up-regulate expression of “beneficial” genes that protect or repair from VILI. In this context, we postulate that ATF3 may up-regulate the expression of genes involved in preserving the integrity of the alveolar capillary membrane, resorption of the coagulum, and wound repair. In keeping with these findings Nonas and colleagues (31) reported on VILI chromosome-specific genes, such as coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor-like 2 (F2RL2). F2RL2 is a member of the protease-activated receptor family that functions as a receptor for thrombin and is decreased in ATF3 KO suggesting contribution of ATF3 to the resorption of the coagulum (32). ATF3 is also known to induce the expression of ATF4 (33), another member of the mammalian ATF family previously implicated in ALI/VILI (34), although further functional genomics studies have yet to elucidate the role of ATF4 in lung injury.

We further postulated that if ATF3 plays an important role in VILI, it should be up-regulated in other species and across other models of VILI. Indeed, we found that ATF3 protein is significantly up-regulated in a rat model of VILI. In this model, injurious MV led to increased ATF3 protein expression in whole tissue extracts as well as nuclear extracts. Based on our immunohistochemistry findings, increased ATF3 expression appears to occur in both parenchymal as well as circulating (infiltrating) myeloid cells. This is in keeping with the ubiquitous role of ATF3 in protecting cells from injury. Further studies are required to determine if cell-specific ATF3 expression may significantly contribute to the injury phenotype in VILI. Our interpretation of these findings is that increased ATF3 expression reflects a compensatory response to injurious challenge (MV and/or LPS in our case), whereas increase in nuclear translocation in conjunction with transcriptional changes of genes containing putative transcriptional regulatory elements suggest increase of its function as a transcription factor. In keeping with this hypothesis, Litvak and colleagues (35) recently demonstrated that ATF3 forms a regulatory circuit with nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and the transcriptional amplifier CCAAT/enhancer binding protein δ (C/EBPδ) that enables the innate immune system to detect the duration of infection and respond appropriately. In this context, ATF3 acts as a transcription inhibitor, whereas NF-κB is the initiator and C/EBPδ is the amplifier.

Although we have interpreted our data within the context of the beneficial effects of ATF3 in VILI, this gene also plays a pleiotropic role in determining cell fate in response to mitogenic or stress stimuli. Some studies suggest ATF3 is proapoptotic by accelerating caspase protease activation (36) and controlling the upstream signaling of apoptosis-related genes by repressing CRE-dependent expression of cell survival factors (37). In contrast, others have suggested an antiapoptotic role for ATF3. For example, overexpression of the gene protects cells from DNA damage–induced apoptosis (38). In models of neuronal stress, ATF3 has been shown to protect from cell death after both JNK activation and nerve growth factor deprivation (39). ATF3 has also been implemented in hypoxemia-related injury (28), although no difference in hypoxemia was seen between phenotypes in our animal experiments. Further studies will be required to understand the contribution of ATF3 to myeloid and epithelial cell death in VILI.

Our overall goal was to identify novel molecules that may provide insight into new therapeutic approaches to treat ALI and VILI (21) because there may be no “safe” MV strategy (40), in most cases MV is unavoidable, and limiting MV by reducing tidal volume may be unattainable (41). In our model, ATF3 deficiency resulted in increased susceptibility to lung injury and inflammation. Although we saw a steady trend in oxygenation decline over time, this was not significantly different between the ATF3-deficient and the WT animals. For the most part, lower oxygenation does not correspond with increased lung inflammation, injury, and poorer outcome as demonstrated by the ARDS network (2). However, it is possible that this difference would have been underscored by longer ventilation times. Importantly, our results suggest that despite the use of a presumably noninjurious ventilation strategy, VILI-induced inflammation still plays a role in promoting significant recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lung. Together with the accumulating clinical data, this suggests that there may be an important role for more “stimulus-directed” antiinflammatory approaches to be included with protective ventilation strategies as adjuvant treatment for VILI.

In conclusion, this is the first report suggesting a role for ATF3 as an antiinflammatory transcription factor that functions to attenuate VILI-induced inflammation. We have demonstrated that expression of ATF3 is stretch dependent and its activity in an animal model plays a pivotal role in attenuating neutrophil recruitment and promoting VILI. We have established that expression and activity of ATF3′ is not species specific and its absence can lead to increased sensitivity to VILI. Moreover, we have shown that ATF3 plays a role in dampening the inflammatory response, even in animals ventilated with a low lung-protective strategy. These results open up the possibility of targeting ATF3-related pathway(s), in addition to controlling the tidal volume to treat patients receiving MV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Kieran Quinn and Dr. Phillip Marsden for their assistance in statistical analysis and setting up the quantitative real-time PCR experiments.

Supported by the Parker B. Francis Foundation (C.C.D.S.), The Physicians Services Incorporate grant (0350), the Ontario Thoracic Society and Lung Association (C.C.D.S.), and grant NIH R01 CA118306 (T.H.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0925OC on June 25, 2010

Author Disclosure: A.A. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. B.H. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. H.M. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. C.P. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. E.L. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. M.L. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. X.B. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. Y.S. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. T.H. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. J.B. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. A.S.S. received $10,001–$50,000 from Asthmatx as a Chair, DSMB for Alair trials; $10,001–$50,000 from Broncus as a Chair, DSMB for their trials; $50,001–$100,000 from LEO as a Chair, DSMB for sepsis trial; and $10,001–$50,000 from Lilly as a Chair, DSMB for PROWESS-Shock trial; $5,001–$10,000 from Hamilton Medical, more than $100,001 from Maquet, and more than $100,001 from Novalung for serving on an advisory board; $1,001–$5,000 from Pfizer for serving on an asthma advisory board; holds a patent from NicoPuff for inhaler to deliver nicotine as a substitute for smoking and a patent from Methco for an improved way to do methacholine challenge tests using powder formulation; $1,001–$5,000 from Viasys in royalties; and holds $50,001–$100,000 in stock or options from Apeiron. W.M.K. received up to $1,000 from Solvay Pharmaceuticals in consultancy fees; $1,001–$5,000 from Hoffmann-LaRoche and up to $1,000 from Revotar Pharmaceuticals in advisory board fees; up to $1,000 from Nycomed in lecture fees; and more than $100,001 from Pfizer, Inc., $50,001–$100,000 from Hoffmann-LaRoche, and $50,001-$100,000 from Solvay Pharmaceuticals in industry-sponsored grants. J.J.H. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. M.L. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. C.C.D.S. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1334–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ARDSnetwork. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1301–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.dos Santos CC, Okutani D, Hu P, Han B, Crimi E, He X, Keshavjee S, Greenwood C, Slutsky AS, Zhang H, et al. Differential gene profiling in acute lung injury identifies injury-specific gene expression. Crit Care Med 2008;36:855–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.dos Santos CC, Han B, Andrade CF, Bai X, Uhlig S, Hubmayr R, Tsang M, Lodyga M, Keshavjee S, Slutsky AS, et al. DNA microarray analysis of gene expression in alveolar epithelial cells in response to TNFalpha, LPS, and cyclic stretch. Physiol Genomics 2004;19:331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han B, Mura M, Andrade CF, Okutani D, Lodyga M, dos Santos CC, Keshavjee S, Matthay M, Liu M. TNFalpha-induced long pentraxin PTX3 expression in human lung epithelial cells via JNK. J Immunol 2005;175:8303–8311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hai T, Hartman MG. The molecular biology and nomenclature of the activating transcription factor/cAMP responsive element binding family of transcription factors: activating transcription factor proteins and homeostasis. Gene 2001;273:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murata R, Ohtori S, Ochiai N, Takahashi N, Saisu T, Moriya H, Takahashi K, Wada Y. Extracorporeal shockwaves induce the expression of ATF3 and GAP-43 in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Auton Neurosci 2006;128:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhlig S. Ventilation-induced lung injury and mechanotransduction: stretching it too far? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;282:L892–L896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan E, Han B, Peng C, Kuiper JW, Zhang H, Haitsma JJ, dos Santos CC. Bioinformatics approach to identifying candidate genes in VILI [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:A949. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, Braisted J, Klapa M, Currier T, Thiagarajan M, et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 2003;34:374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palacios R, Goni J, Martinez-Forero I, Iranzo J, Sepulcre J, Melero I, Villoslada P. A network analysis of the human T-cell activation gene network identifies JAGGED1 as a therapeutic target for autoimmune diseases. PLoS ONE 2007;2:e1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie X, Lu J, Kulbokas EJ, Golub TR, Mootha V, Lindblad-Toh K, Lander ES, Kellis M. Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in human promoters and 3′ UTRs by comparison of several mammals. Nature 2005;434:338–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crimi E, Zhang H, Han RN, Del Sorbo L, Ranieri VM, Slutsky AS. Ischemia and reperfusion increases susceptibility to ventilator-induced lung injury in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolthuis EK, Vlaar AP, Choi G, Roelofs JJ, Haitsma JJ, van der Poll T, Juffermans NP, Zweers MM, Schultz MJ. Recombinant human soluble tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor fusion protein partly attenuates ventilator-induced lung injury. Shock 2009;31:262–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolthuis EK, Vlaar AP, Choi G, Roelofs JJ, Juffermans NP, Schultz MJ. Mechanical ventilation using non-injurious ventilation settings causes lung injury in the absence of pre-existing lung injury in healthy mice. Crit Care 2009;13:R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altemeier WA, Matute-Bello G, Gharib SA, Glenny RW, Martin TR, Liles WC. Modulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced gene transcription and promotion of lung injury by mechanical ventilation. J Immunol 2005;175:3369–3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res 2001;125:279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:5116–5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilchrist M, Thorsson V, Li B, Rust AG, Korb M, Roach JC, Kennedy K, Hai T, Bolouri H, Aderem A. Systems biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature 2006;441:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam E, dos Santos CC. Advances in molecular acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome and ventilator-induced lung injury: the role of genomics, proteomics, bioinformatics and translational biology. Curr Opin Crit Care 2008;14:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida T, Sugiura H, Mitobe M, Tsuchiya K, Shirota S, Nishimura S, Shiohira S, Ito H, Nobori K, Gullans SR, et al. ATF3 protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seijffers R, Mills CD, Woolf CJ. ATF3 increases the intrinsic growth state of DRG neurons to enhance peripheral nerve regeneration. J Neurosci 2007;27:7911–7920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abe T, Oue N, Yasui W, Ryoji M. Rapid and preferential induction of ATF3 transcription in response to low doses of UVA light. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003;310:1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamdi M, Popeijus HE, Carlotti F, Janssen JM, van der Burgt C, Cornelissen-Steijger P, van de Water B, Hoeben RC, Matsuo K, van Dam H. ATF3 and Fra1 have opposite functions in JNK- and ERK-dependent DNA damage responses. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu D, Wolfgang CD, Hai T. Activating transcription factor 3, a stress-inducible gene, suppresses Ras-stimulated tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem 2006;281:10473–10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown SL, Sekhar KR, Rachakonda G, Sasi S, Freeman ML. Activating transcription factor 3 is a novel repressor of the nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-regulated stress pathway. Cancer Res 2008;68:364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen SC, Liu YC, Shyu KG, Wang DL. Acute hypoxia to endothelial cells induces activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) expression that is mediated via nitric oxide. Atherosclerosis 2008;201:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilchrist M, Henderson WR Jr, Clark AE, Simmons RM, Ye X, Smith KD, Aderem A. Activating transcription factor 3 is a negative regulator of allergic pulmonary inflammation. J Exp Med 2008;205:2349–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khuu CH, Barrozo RM, Hai T, Weinstein SL. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) represses the expression of CCL4 in murine macrophages. Mol Immunol 2007;44:1598–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nonas SA, Moreno-Vinasco L, Ma SF, Jacobson JR, Desai AA, Dudek SM, Flores C, Hassoun PM, Sam L, Ye SQ, et al. Use of consomic rats for genomic insights into ventilator-associated lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;293:L292–L302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.dos Santos CC, Slutsky AS. Mechanotransduction, ventilator-induced lung injury and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2000;26:638–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niknejad N, Morley M, Dimitroulakos J. Activation of the integrated stress response regulates lovastatin-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2007;282:29748–29756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gharib SA, Liles WC, Matute-Bello G, Glenny RW, Martin TR, Altemeier WA. Computational identification of key biological modules and transcription factors in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Litvak V, Ramsey SA, Rust AG, Zak DE, Kennedy KA, Lampano AE, Nykter M, Shmulevich I, Aderem A. Function of C/EBPdelta in a regulatory circuit that discriminates between transient and persistent TLR4-induced signals. Nat Immunol 2009;10:437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mashima T, Udagawa S, Tsuruo T. Involvement of transcriptional repressor ATF3 in acceleration of caspase protease activation during DNA damaging agent-induced apoptosis. J Cell Physiol 2001;188:352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamura K, Hua B, Adachi S, Guney I, Kawauchi J, Morioka M, Tamamori-Adachi M, Tanaka Y, Nakabeppu Y, Sunamori M, et al. Stress response gene ATF3 is a target of c-myc in serum-induced cell proliferation. EMBO J 2005;24:2590–2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nobori K, Ito H, Tamamori-Adachi M, Adachi S, Ono Y, Kawauchi J, Kitajima S, Marumo F, Isobe M. ATF3 inhibits doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in cardiac myocytes: a novel cardioprotective role of ATF3. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2002;34:1387–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakagomi S, Suzuki Y, Namikawa K, Kiryu-Seo S, Kiyama H. Expression of the activating transcription factor 3 prevents c-Jun N-terminal kinase-induced neuronal death by promoting heat shock protein 27 expression and Akt activation. J Neurosci 2003;23:5187–5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA, Esmon C, Bhattacharya J, Coller B, Doerschuk CM, Floros J, Gimbrone MA Jr, Hoffman E, Hubmayr RD, et al. Future research directions in acute lung injury: summary of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1027–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villar J, Kacmarek RM, Hedenstierna G. From ventilator-induced lung injury to physician-induced lung injury: why the reluctance to use small tidal volumes? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2004;48:267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.